Introduction

This Journal of Management & Organization Special Issue on the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 (SDGs) has been developed following the Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management (ANZAM) 2019 Annual Conference held in Cairns, Australia and hosted by the School of Business and Law, Central Queensland University. The theme of this conference was ‘Wicked Solutions to Wicked Problems: The Challenges Facing Management Research and Practice’ and a wide range of diverse papers, dealing with various wicked (and not so wicked) problems were submitted. A selection of presented papers with a strong orientation to the UN SDGs, alongside other papers received through a second Call for Papers, have been put through a separate detailed blind review process before finalising the seven papers contained herein.

In this editorial, we begin by outlining our initial motivation to explore the UN SDGs in the context of the management discipline, in which we also highlight that management research, not just management education, has a large role to play in understanding and addressing the big, complex challenges in the world; at this point, however, we also outline the recently emerging criticisms of universities, and management research specifically, as being removed from those complex, real-world problems. Following a brief discussion of the related concepts of SDGs, Grand Challenges and Wicked Problems, we demonstrate the popularity of the SDGs and provide an overview of the various recent developments towards achieving our advocated alignment between management scholarship and SDGs. We then provide a synopsis of the papers in this Special Issue, before concluding the editorial with an overview of the current progress against the SDGs, how COVID-19 has impacted this progress, and what the future may hold for the links between management research and the SDGs.

Management research and SDGs

Our initial interest in the UN SDGs stemmed from a desire to find a reality focus for management research in our business schools. That is, mechanisms to assist management researchers to apply their skills to real-world problems, rather than theory building or extension with little or no connection to practice or key societal issues. For some years, a number of authors have commented on the growing disconnect between academic management research and the practical realities of the world. The growing emphasis on research ‘quality’ (as measured primarily by journal citation impact) has been a dominant factor in most higher education business schools, with various journal ‘quality’ rankings becoming key drivers of the research agendas of management academics. This view still persists despite the fact that such measures have been severely criticised as: (i) diverting academic management research away from the key issues of the world (Jarwal, Brion, & King, Reference Jarwal, Brion and King2009), (ii) generating ideological separations between academic teaching and research roles (Balkin & Mello, Reference Balkin and Mello2012) and (iii) creating problems for effective performance management in business schools (Chapman, Reference Chapman2012).

In the context of teaching and learning, business schools have been educating students on ethics, corporate social responsibility and related sustainability concepts, thus shaping students' knowledge, skills and attitudes towards the need to address societal problems in their professional careers (e.g. Setó-Pamies and Papaoikonomou, Reference Setó-Pamies and Papaoikonomou2016). However, the same focus on sustainability and solving society's big problems is not present in academics' research roles. This contributes to the above-mentioned chasm between business schools' teaching and research activities as the focus on ‘making a difference’ and ‘real-world relevance’ advocated in the classroom is not mirrored in management research: business schools, journals and management academics have had few incentives to address critical problems of business or society generally, because the performance measurement systems and funding models have obscured any real link between investment and returns (Glick, Tsui, & Davis, Reference Glick, Tsui and Davis2018). Furthermore, by disconnecting from the real world of business and community and researching primarily for the sake of ‘highly-ranked’ journal publication, management scholarship has become largely socially irresponsible (Tsui, Reference Tsui2015). According to Tsui (Reference Tsui2015: 38), a former President of the US Academy of Management: ‘[i]t is failing to meet the goal of science: to discover truth and improve the human condition’.

In the last 10 years or so, several authors have questioned the reigning paradigm for management research in highly critical terms:

Today, it's more ‘publish as we perish’. We have been producing more and more shit of less and less overall quality for a generation. Has it advanced ‘knowledge’? Face it, you've read thousands of articles in your career and you've been influenced by, at best, a few dozen. (Alvesson & Gabriel, Reference Alvesson and Gabriel2013: 246)

However, there have been growing calls to address these systemic problems. The key international business school accreditation bodies (AACSB, EFMD and AMBA) have increasingly included research impact, engagement and innovation into their accreditation standards. EFMD (European Foundation for Management Development), which was founded with a greater emphasis on corporate connections and sustainability, created the Business School Impact System in 2014 to help schools more fully assess their impact on business and society. They have also incorporated an expectation that schools demonstrate a commitment to be globally responsible citizens in their 2013 accreditation standards.

In 2014, a group meeting of concerned northern hemisphere researchers formed the Community for Responsible Research in Business and Management (cRRBM) dedicated to addressing these growing concerns regarding business research generally. In 2017, this organisation (now generally referred to as RRBM) put forward a position paper which included their Vision 2030: ‘A Vision of Responsible Research in Business and Management: Striving for Useful and Credible Knowledge’ (RRBM, 2017). This position paper articulated their vision for ‘a future in which business schools and scholars worldwide have successfully transformed their research toward responsible science, producing useful and credible knowledge that addresses problems important to business and society’. Today, the RRBM has expanded to 28 co-founders and 85 co-signers of the position paper, plus almost 1,200 endorsers, over 65 institutional partners and seven pioneer schools.

In 2018, CEEMAN, an international management development association established in 1993 with close to 200 members from 45 countries in Europe, North America, Latin America, Africa and Asia, published the CEEMAN Manifesto, ‘Changing the Course of Management Development: Combining Excellence with Relevance’. It constitutes a call to action for management education institutions to determine if both excellence and relevance are sufficiently featured in their mission and strategy (CEEMAN, 2018).

In other developments, the UK Research Excellence Framework that drives government funding for UK universities in 2014 added a 20% weighting on the societal impact of universities research programmes. The National Science Foundation (NSF) in the USA added a ‘broader impacts’ criterion to funding proposals from 1997 and organisations such the Centre for Open Science have introduced multiple initiatives related to openness, transparency and reliability for research reporting (Glick, Tsui, & Davis, Reference Glick, Tsui and Davis2018).

In the last few years, ‘real’ research impact has been regularly appearing in research discussions concerning Australian and New Zealand universities as well. The Australian government has introduced a new Engagement and Impact Assessment (EI) to run alongside the existing Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA) assessment from 2018 onwards, and New Zealand has been using its Performance-Based Research Fund (PBRF) for some time, which focuses more on individual research outcomes and includes impact and engagement considerations. As this editorial is being written (September 2020), the Australian Research Council (ARC) have submissions open for a comprehensive review of both the ERA and EI schemes. International networks of leading researchers such as those discussed above, business school accreditation bodies and societal pressures for greater value from universities are pushing publishers, academies and business schools to focus on issues of real importance to industry and society.

Therefore, the importance of real-world relevance in teaching is obvious, and there is clearly also a growing movement to encourage and reward real societal outcomes for management research, as opposed to research driven primarily by citation impact factors and publication counts frequently incentivised by internal university systems. Despite these developments, we have seen only limited discourse on mechanisms and frameworks to guide and assist academics in undertaking such research.

However, the world is full of complex problems and large-scale, even global, issues and changes that defy simplistic solutions but could certainly benefit from academic research to better understand and address them. The terms ‘Grand Challenges’ (Brammer, Branicki, Linnenluecke, & Smith, Reference Brammer, Branicki, Linnenluecke and Smith2019; George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi, & Tihanyi, Reference George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi and Tihanyi2016) and ‘Wicked Problems’ (Elia & Margherita, Reference Elia and Margherita2018) are often linked to these complex issues, and the UN SDGs are an attempt to encapsulate many of these problems into a framework of goals and targets to assist actions addressing these problems. Grand Challenges are large-scale problems often best articulated by a combination of the SDGs. Wicked Problems are similar in scope, often defined by the original 10 criteria identified by Rittel and Webber (Reference Rittel and Webber1973) and discussed at length by Crowley and Head (Reference Crowley and Head2017). In addition, Peters (Reference Peters2017) has extended the definition using four additional criteria to create what he has termed ‘super-wicked problems’. Also, wicked problems are often divergent, where different answers appear to increasingly contradict each other the more they are elaborated (Schumacher, Reference Schumacher1977). It is clear that there is considerable overlap between these three terms, with the possible achievement of the SDGs by 2030 requiring solutions to a great many grand challenges and wicked problems.

The inception of the SDGs goes back to the year 2000, when 189 country leaders signed the so-called Millennium Declaration at the United Nations headquarters. By signing this declaration, they confirmed their commitment to achieving eight specific goals (the Millennium Development Goals, or MDGs for short) by 2015. Clearly measurable targets were attached to each of these eight goals, which ranged from eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, over promoting gender equality and empowerment of women, to ensure environmental sustainability and establishing global partnerships for development.

Movement towards achieving the MDGs generated momentum and inroads were made to achieve some of these goals, but others required more work. Thus, the UN conducted extensive global consultation in order to generate a people-centred development agenda that would build upon said momentum, to address areas that required further development, and to expand the goals both in terms of their scope and time duration, beyond 2015. This consultation process eventually resulted in the identification of 17 SDGs, each containing a number of specific targets (altogether 169 targets), which cover three dimensions of sustainable development: economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection. The 17 SDGs are commonly depicted as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The UN SDGs for 2030. Source: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/.

Although the SDGs contain these broad goals and large number of targets, they are not developed to be relevant only for governmental or organisational leaders – instead, the UN frames the SDGs as an open call, aimed at everyone, globally, to join the movement towards achieving the 17 goals, by specifically highlighting the need for action on the following three levels:

global action to secure greater leadership, more resources and smarter solutions for the Sustainable Development Goals; local action embedding the needed transitions in the policies, budgets, institutions and regulatory frameworks of governments, cities and local authorities; and people action, including by youth, civil society, the media, the private sector, unions, academia and other stakeholders, to generate an unstoppable movement pushing for the required transformations (United Nations, 2020).

It is clear from this call to action that academia, as well as the public and private sector, has a role to play in supporting the achievement of the SDGs. This includes the management discipline; George et al. (Reference George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi and Tihanyi2016) had previously demonstrated this importance of the management discipline by showing how management practitioners and management researchers are affected by Grand Challenges and how they can, in turn, play a significant role in impacting change towards addressing, or even solving, some of these Grand Challenges. Despite George et al.'s (Reference George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi and Tihanyi2016) clear demonstration of the relevance of management discipline for the Grand Challenges, we decided to focus on the SDGs as the best approach to provide guidance for academic management research because of the more specific nature of the SDGs and the associated targets for each goal.

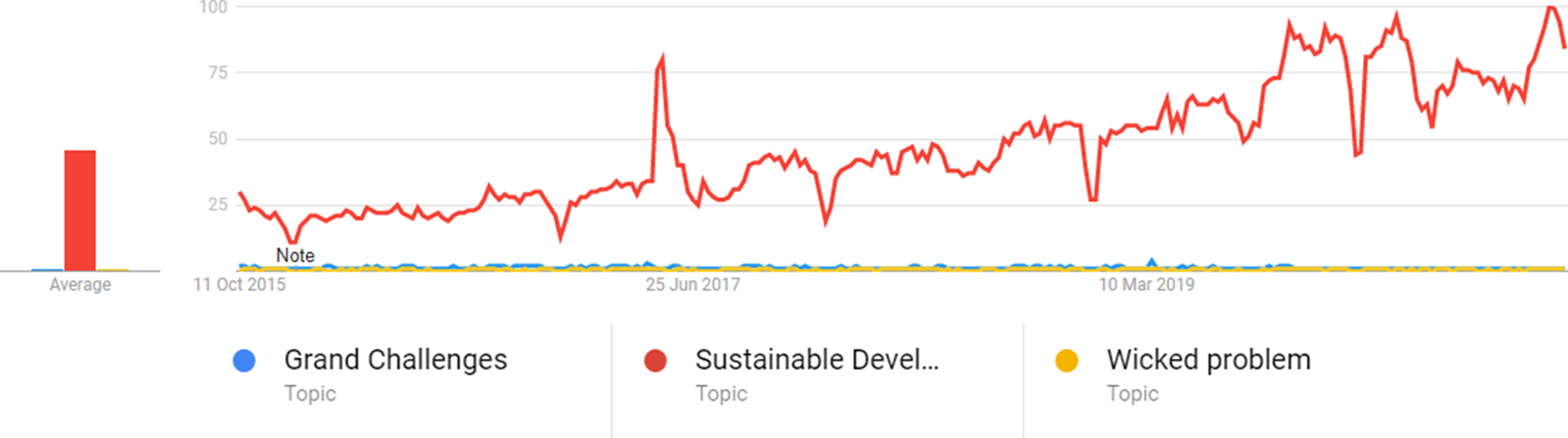

Our decision to focus on the SDGs, as opposed to the other related concepts, is further supported by the SDGs' global popularity, as the SDGs have captured the interest of the general population considerably more than the terms ‘Wicked Problems’ or ‘Grand Challenges’. Figure 2, derived from a Google Trends analysis, illustrates this accelerating general global interest in the SDGs over the last few years: worldwide web searches for the term ‘Sustainable Development Goals’ have grown markedly since 2015 – the chart displays search interest relative to the term's peak popularity, which is shown by the number 100 in the chart. In contrast to this increasing search for SDGs, the terms ‘Grand Challenges’ and ‘Wicked Problems’ both scored only 1 or <1 in comparison. Thus, it seems clear that while ‘Grand Challenges’ and ‘Wicked Problems’ are topics that have generated considerable research interest, the SDGs have become the key term for the global community, at least as judged by Google searches. It is also interesting to note that September 2020 has recorded a peak in interest for SDGs (the final point of the graph is for searches in early October 2020). The week September 18–25, 2020 was promoted as the ‘Global Week to #ACT4SDGS’ generating a global upsurge in interest relating to the SDGs.

Figure 2. Google Trend analyses for SDGs, grand challenges and wicked problems. Source: https://trends.google.com/trends/explore.

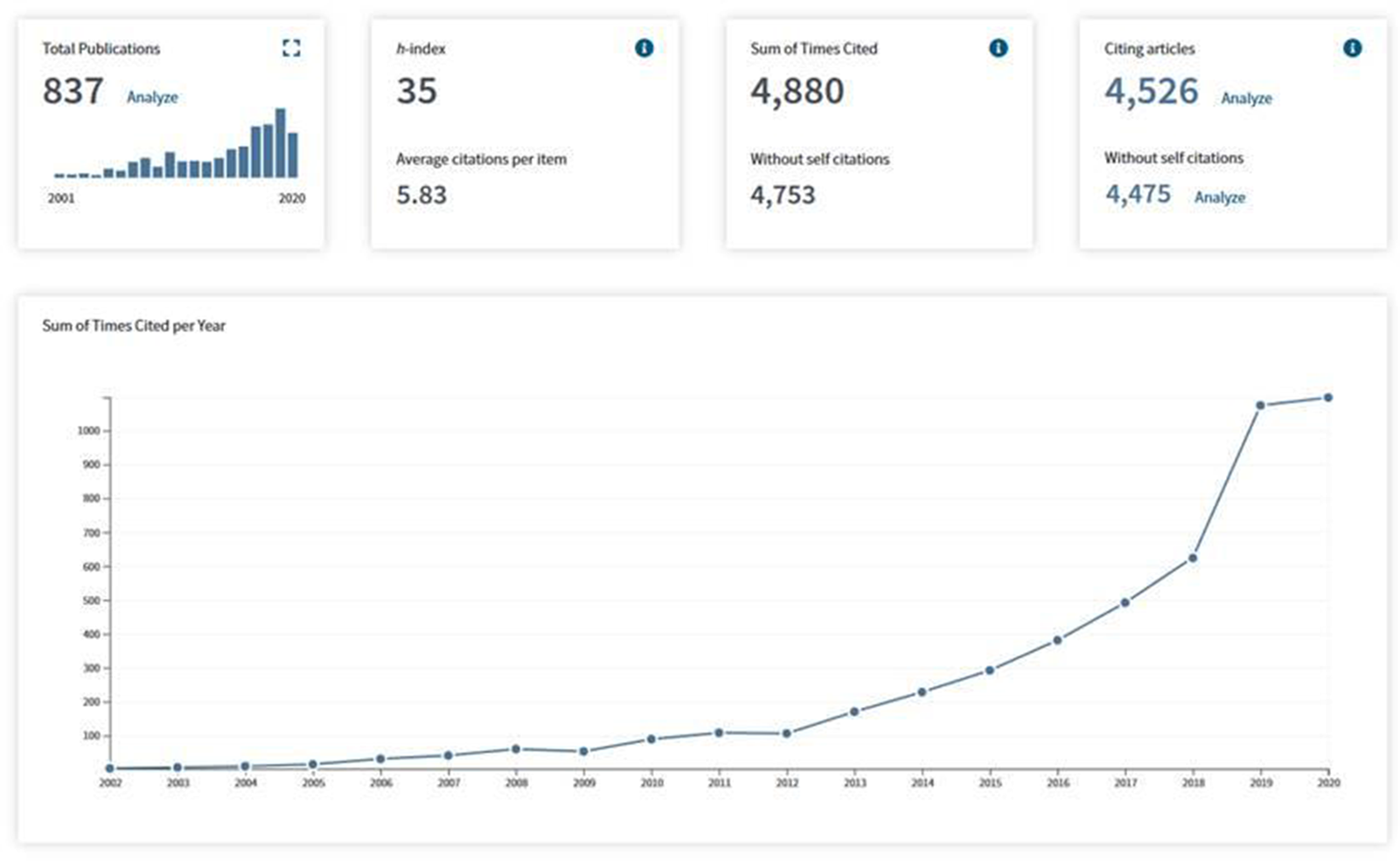

Although Figure 2 focuses on web searches in general, Figure 3 presents a citation analysis, based on Web of Science data, of articles that are published in management journals and specifically refer to SDGs. This clearly shows that we are not alone in recognising the importance of the SDGs for the management discipline: again, we can see rapidly accelerating interest from authors of scholarly management articles on the SDGs, with 2020 numbers, of course, not yet complete.

Figure 3. Citation Report for topic: SDGs. Citation Report graphic is derived from Clarivate Web of Science, Copyright Clarivate 2020. All rights reserved.

University and academic initiatives concerning the SDGs

When we started our considerations of mechanisms to improve real research impact for management research in 2016–17, the 17 SDGs had barely touched the university sector. However, these goals encapsulated our ideas for improving real research impact by providing a broad range of goals and targets to assist researchers in focusing their research activities towards effective community and global improvement. Our work began by undertaking seminars and workshops to build awareness of the SDGs and to assist management academics in understanding how they might incorporate and apply the goals to their research activities.

Much of the early work in building awareness and commitment to the SDGs has been undertaken by the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN). The SDSN was set up in 2012 under the auspices of the UN Secretary-General and its missions are to promote integrated approaches to implement the SDGs and the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, through education, research, policy analysis and global cooperation (SDSN-About us, 2020). In 2017, the Australia-Pacific arm of the SDSN produced a guide to assist universities in getting started with the SDGs (SDSN Australia/Pacific, 2017), and in September 2020 the full SDSN published an extensive guide to assist educational institutes incorporate the SDGs into the education components of their operations (SDSN, 2020).

Very recently, we have seen a few systematic reviews appearing relating to management academics and the SDGs. Pizzi, Caputo, Corvino, and Venturelli (Reference Pizzi, Caputo, Corvino and Venturelli2020) analysed 266 articles between 2012 and 2019 finding four key themes of research appearing: technological innovation; firms' contribution in developing countries; non-financial reporting; and education for SDGs. Other authors have focused on the role of management education in supporting the achievement of the SDGs: Weybrecht (Reference Weybrecht2017) spoke of the importance of management education working hand-in-hand with the business sector, whereas Ndubuka and Rey-Marmonier (Reference Ndubuka and Rey-Marmonier2019) discussed capability approaches for management education to assist in achieving the SDGs in UK business schools. However, as Pizzi et al. (Reference Pizzi, Caputo, Corvino and Venturelli2020) concluded, despite the rapidly increasing number of papers appearing, the contribution of business and management academics to the achievement of the SDGs remains very fragmented.

There have also been a number of Special Issues in business and management journals focusing on the application of the SDGs in business education and research, as well as a few full articles published that provide possible solutions to assist academics to become more fully engaged with the SDGs. As Setó-Pamies and Papaoikonomou (Reference Setó-Pamies and Papaoikonomou2020: 1769) conclude in their recent Editorial for a Special Issue in Sustainability: ‘In management education, SDGs should be understood as an opportunity to accelerate the long-required changes in management curricula in order to give sustainable development the protagonism it deserves’. Again, the focus on SDGs in learning and teaching, as opposed to research, is prominent in these recent publications.

A common theme in these Special Issues, the individual journal articles, and the case studies published in the SDSN guides, is the difficulties generated by the discipline-siloed structures of most universities. As most of the complex problems inherent in the SDGs require input and work from several different disciplines, the current university structures often require academics to undertake work that may not be recognised or rewarded by their administrative managers. Thus, interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary research agendas are required. One way this may be addressed is to develop specific research centres that focus on these complex problems and can be used to create the opportunities for researchers from different disciplines to work together. As several of the case studies in the second SDSN Guide (SDSN, 2020) indicate, it takes strong action from the highest management levels in a university to ensure research focus on the SDGs can be developed and promoted, because of the road blocks presented by existing university organisational structures and performance measurement systems.

Overview of papers

The first of the seven articles in this Special Issue is entitled ‘Addressing Sustainable Development Goals for Confronting Climate Change: Insights and Summary Solutions in the Stress Stupidity System’. In this article, Jerry Paul Sheppard and Jesse Young focus on the SDGs for climate and environmental liveability, specifically the issue of climate change. The authors pose the question: ‘Are we being stupid?’ – we (as in individuals, organisations and governments) are not only well aware of this worsening crisis, but also know what we should do to avert it, and yet we tend to take no action, or even act in a manner that exacerbates the crisis further. By relying on various examples of stupid behaviour from public and private sectors in the context of climate change, the authors build on the ‘threat-rigidity effect’ theory to develop the ‘stress-stupidity system’. This framework shows that environmental changes like climate change cause stress, which in turn triggers ‘functional stupidity’, characterised by a lack of reflection, justification and substantive reasoning. In familiar situations, routine reactions can be sufficient to address the stress, but in ambiguous situations, such as those present in the complexity of climate change, ‘identifiable stupidity’ can emerge. This consists of confident ignorance, failure to pay attention and lack of impulse control, and can lead to ‘stupidity in response’ as we are inclined to act in rigid ways even in ambiguous situations. If we are not motivated to address our stupid actions, we further intensify the stress as we respond inaptly. On the contrary, if we are motivated to address our stupidity, we can develop apt responses to the stresses, which will gradually reduce them, and as such enable us to ‘fix stupidity’. The article concludes with a useful outline of some specific suggestions of how we can fix stupidity in order to address the SDGs for climate and environmental liveability.

Some of the suggestions of how to ‘fix stupidity’ in the first paper refer to government actions to combat climate change. However, although the government may initiate legislations and guidelines, actions also need to be implemented elsewhere, such as at organisational levels. In the second article, ‘The business – government nexus: Impact of government actions and carbon legislation on business responses to climate change in Australia’, Sheela Sree Kumar, Bobby Banerjee, Fernanda Duarte and Ann Dadich explore the organisational level further. This article studies the responses of high carbon-emitting Australian businesses to the government action and carbon legislation, specifically the carbon tax that was introduced in 2012 and repealed in 2014 – thus, it focuses on carbon emissions, which also relates to climate change and SDG 13 (climate action). The authors report on the findings from semi-structured interviews with climate change related decision makers of 17 businesses from high-emitting industries (including chemical, mining and electricity) and two industry association personnel. The data were collected during 2012 and 2013 as the carbon tax was being implemented, to study organisations' reactions in real time. The findings showed three strategies that organisations could follow in response to the carbon tax, as well as the underlying government forces that drive organisations to these strategies. Uncertainty in global regulatory developments, inconsistent Australian climate policy and competitive threats were the main government forces that drove businesses to adopt resistive strategies, which include thwarting policy and influencing public opinion in an attempt to prevent change. Businesses that adopted reactive strategies (including preparing for the tax, protecting business interests and generating profits) were equally exposed to these negative forces, but also faced some positive forces, such as their relationships with agents, positive impacts from government actions (e.g. subsidies) and opportunity to advance research and development. Moreover, all businesses were using cooperative strategies to respond to the legislation. The negative and positive forces identified in this study will help governments to understand how their legislation and action affects the responses of businesses.

Although the high-emitting companies considered in the second article have a large role to play in achieving the climate-related SDGs, there is another group of companies, which plays a significant role in the economy but is often overlooked as a key player in the race to achieve sustainability: the small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The article ‘The challenge of engaging with and reporting against the SDGs for SMEs such as Sydney Theatre Company’ by Valerie Dalton focuses on the difficulties that SMEs face when trying to use various frameworks and tools that exist to support businesses in their endeavour to address the SDGs and report on their progress towards achieving them. The author outlines some of these tools, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines, the UN Global Compact business principles, guidelines produced by consulting firms like KPMG and the SDG Compass, to name a few, and criticises the large number and complexity of these different tools, as well as their apparent focus on large, multinational corporations with extensive resources at their disposal. The article employs an in-depth retrospective case study approach to explore the sustainability journey of a single case study, the ‘Greening the Wharf’ project of the Sydney Theatre Company (STC). The data for this case study were derived from multiple interviews with key STC staff, as well as documentary and other evidence. The author used the SDG Compass (UN, 2015) as a tool to retrospectively re-analyse the data in an attempt to see how an SME could use it to report on the SDGs. The findings suggest that the tool is overly complex, lacks clarity and requires extensive levels of detail, which would require a prohibitively large amount of time, background knowledge and effort to record and report on – all of these are resources that SMEs typically do not have in abundance. Dalton concludes by calling for a simpler tool, which SMEs could apply to their own sustainability journey, so that this important group of businesses can also better contribute to the achievement of the SDGs.

Although SMEs have problems trying to apply the complex guidelines produced by the UN and other agencies, social enterprises are frequently initiated to address a particular issue relevant to the SDGs. In ‘‘Wicked’ solutions for ‘wicked’ problems: Responsible innovations in social enterprises for sustainable development’, Nadeera Ranabahu stresses the importance of social enterprises, set up to address wicked social problems and deliver social impact, in the endeavour to achieve the SDGs. These enterprises are often required to be innovative in order to achieve their mission, but innovation can be costly. This fourth article relies on the conceptual framework of responsible innovation (Stilgoe, Owen, & Macnaughten, Reference Stilgoe, Owen and Macnaughten2013) to study how social enterprises use responsible innovation practices to achieve the SDGs. Applying a qualitative case study methodology, the author used a wide range of multi-media secondary data to develop rich descriptions of the innovation journeys of three award winning social enterprises, which all make use of innovative technology to address one or more wicked social problems. The findings suggest that social enterprises start with the intention of addressing one or only a small number of SDGs, but as they grow, they make deliberate responsible innovation decisions as they expand their geographical coverage as well as product/service portfolio, which allows them to increase their social goals and address additional SDGs. The article contains rich explanations of the case companies' application of the responsible innovation dimensions: anticipation of positive and negative consequences of the innovation; self-aware reflexivity on actions, values and responsibilities; inclusion and deliberation through stakeholder involvement; responsiveness to environmental changes; and management of knowledge in- and outside the organisation. In conclusion, the article presents a model of responsible innovation in social enterprises by depicting the four interrelated dimensions as an expanding spiral that demonstrates not only the dynamic nature of these dimensions, but also their collective contribution to social enterprises' ability to increase their social impact.

In our fifth paper of the Special Issue, Olav Muurlink and Stephanie Macht have considered another important organisational type in the achievement of the SDGs, particularly in developing nations: the Non-Government Organisation (NGO). The article entitled ‘Managing (out) corruption in NGOs: A case study from the Bangladesh delta’ considers the complex and pervasive wicked problem of corruption. This article presents a rich description of a single, longitudinal ethnographic case study of how one Bangladeshi NGO, which had suffered from deep-rooted corruption since inception around three decades ago, has managed to address and ultimately eradicate corruption in its own organisation. The authors demonstrate that NGOs are not safe from corrupt behaviour although much literature suggests that they are the solution to corruption, especially in countries where corruption is the norm, rather than the exception. The conceptual framework of the article focuses on the Corruption Triangle theory (Byars, Reference Byars2009), which suggests that for corruption to occur, the following three elements have to be present: opportunity, motivation and rational decision to commit the corrupt act. By recounting the process that the first author (who is the ethnographer in this article, as well as the head of country of the case study NGO) followed to fight this entrenched corruption, this article highlights that this wicked problem can be addressed through indirect interference with one of the Corruption Triangle elements: opportunity. Through improved information channels for stakeholders, the NGO was able to interrupt the opportunity to carry out corrupt acts, thus demonstrating that even complex problems like corruption can be addressed through simple, sustainable interventions.

In addition to governments, high-emitting companies, SMEs, social enterprises and NGOs, our sixth article considers the important role of academia in achieving the SDGs. In ‘The wicked problem of measuring real-world research impact: Using sustainable development goals (SDGs) and targets in academia’, authored by Geoffrey Chapman, Ashley Cully, Jennifer Kosiol, Stephanie Macht, Ross Chapman, Anneke Fitzgerald and Frank Gertsen, the authors argue that researchers have a civic duty to ensure that their work has valuable impact for the ‘real world’. This sixth article deals with the difficulties and problems of measuring research quality and research impact in academia. Traditionally research ‘quality’ is measured with the help of more than two dozen diverse bibliometric indices and metrics, such as the h-index or the journal impact factor. The authors criticise these indices, particularly when used as performance measures, as they encourage research for the sake of publishing, with impact purely in the academic world. Of course, research should add value to society, economy, individuals and other research end-users beyond academia and contribute significantly to addressing the big, wicked problems in the world. The article moves on to propose the use of the UN SDGs, and their associated targets, as an alternative, real-world relevant measure of research impact. The authors then report on the findings from world café format discussions among 51 management researchers who were faced with the question of how to measure research impact, who the research end-user is, how alignment with SDGs could be operationalised in academia, and what role network organisations such as ANZAM could play in achieving such alignment. The common consensus among the world café participants was that: (i) the use of SDGs for measuring research impact had potential but requires more awareness of SDGs; (ii) academia needs to collaborate with industry to a much greater extent; (iii) the SDG targets and the measures of impact need to be more clearly defined and communicated and (iv) individual and institutional research agendas and performance measures need to be more closely aligned to the SDGs and their targets.

Although the sixth article looks at how research quality and impact measures need to be modified to better address the SDGs with a particular emphasis on management research, the final paper considers the role of management researchers in interdisciplinary research addressing climate change, one of the key global issues addressed by the SDGs. In ‘The wicked problem of climate change and interdisciplinary research: Tracking management scholarship's contribution’, Franz Wohlgezogen, Angela McCabe, Tom Osegowitsch and Joeri Mol view climate change as a wicked problem that needs to be tackled through the collaboration of multiple disciplines, including management. Through extensive bibliometric analysis of published journal articles over the last four decades, the authors identified that management researchers are increasingly concerned with climate change, and often make reference to climate change knowledge from other disciplines, including science. However, the authors find that the reverse situation is not the case. That is, management researchers' impact on other disciplines is very limited, as only very few publications in Nature and Science, the top tier interdisciplinary journals dealing with climate change, cite management research. It is argued that this should change because the management discipline has great potential to provide valuable contributions to interdisciplinary research on climate change: it can further our understanding of climate change, support the development of responses to climate change and add methodological contributions. This article outlines some specific ways in which management research can join this debate, for instance, by contributing research on change management, strategic responses to climate change, consumer and organisational behaviour and sustainable business practices, just to name a few. The authors tentatively suggest that researchers in other disciplines may not consider management research particularly relevant for climate change debates and recommend that management scholars need to find a way of better demonstrating the value and relevance of their research to other disciplines. Specifically, management scholars, who work in the climate change space, should promote their work better, and actively seek out collaborations outside their own discipline so as to break down existing disciplinary silos, biases and prejudices, to be able to make the most of the myriad of benefits that can be gained from interdisciplinary research.

Where to go from here

There is a real opportunity for the management discipline to quickly mobilise new initiatives to support societal responses to COVID-19 and recovery. It may require re-assessing the usefulness of single metrics (such as GDP), and perhaps a start to painting a fuller picture through harnessing stories from businesses all over the world creating many data points and giving a clearer picture of lived experiences to ensure meaningful (research) impact. Collecting data at lower levels (sub-national data) is more appropriate for certain SDG targets (van Zanten & van Tulder, Reference van Zanten and van Tulder2020). Although many benefits of economic activities at the company-level can be quantified in terms of GDP (i.e. the value added delivered by an economic activity), its externalities, such as the adverse effects on climate, ecosystems and human health, are not priced. Therefore, van Zanten and van Tulder (Reference van Zanten and van Tulder2020: 12) pose a challenge to business scholars: ‘what can replace GDP and provide quantifications of impacts of economic activities at the level of companies?’

Other potential areas for exploring renewed innovation may include: employee well-being initiatives; business risk and crisis management; supply chain and operations management and logistics; sustainable financing; business planning process innovation, business resilience, branding and so forth. These research opportunities have the potential to turn current challenges into meaningful change and real research impact.

According to participants at the April 2020 SDSN/ACTS (Australian Campuses Towards Sustainability) forum some things particularly management scholars can do are: (1) translating relevant management research quickly and communicate this to government and others for management decision-making; (2) helping facilitate a larger discussion on what a sustainable development-led recovery looks like and insights from what is already happening, and providing them into the public policy sphere; (3) helping develop and re-skill the workforce to support recovery from the crisis and, (4) working collaboratively to support each other and strengthen the collective message (SDSN Australia/Pacific, 2020). This can only be done from inter- and multi-disciplinary points of view, using partnerships and communication channels to bring research, evidence and practices to policy making. This was also acknowledged by who state that there is a real need for management academics to work together towards holistic solutions to SDG problems, as well as the need for a stronger engagement with industry to bridge the research-practice gap that persists.

But how can we equip people to respond to and harness the challenges and opportunities? This crisis has shown how vital it is that all learners acquire the knowledge, skills and mindsets to solve complex societal and management decision making problems. This is the essence of management education. Many universities undertake this in a niche way, but the crisis has shown how important it is to mainstream this. Responsible Management Education (RME) as a field is still eclectic in their view on purpose and goals of management education as a driver for change (Storey, Killian, & O'Regan, Reference Storey, Killian and O'Regan2017). However, working towards the UN SDGs 2030 may bring the field somewhat more together, where divergence is viewed as a strength. In this disorderly space, the emergence of the SDGs may help management educators realise the opportunities available.

Therefore, the way forward is for universities to ensure business and management courses incorporate the SDGs at all levels of the curriculum, reduce the focus on outdated measures of research quality in their performance measurement systems and provide real leadership in both their own operations and in the interactions with the wider community by building their strategic plans around the SDGs. Accreditation bodies may well start to focus on social responsibility as an underlying value and can assist with shifting paradigms within business education. For example, the assurance of learning process of AACSB (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business) can be used to comprehensively map responsibility and sustainability through programmes that include this as a programme-goal or graduate attribute (Storey, Killian, & O'Regan, Reference Storey, Killian and O'Regan2017). The management discipline will continue to have a critical role in supporting businesses and society through our research, teaching, operations and leadership. Management scholars need to seize the opportunities for innovative management research and education initiatives focusing on the SDG targets, resetting for growth in the new post-COVID ‘normal’.