INTRODUCTION

One of the most notable outcomes of globalization has been the rise of a number of emerging market multinationals (EMNCs), which are asserting themselves with new vigor onto the world stage (Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev, & Peng, Reference Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev and Peng2013; Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2015; UNCTAD, 2016). Due to the considerable heterogeneity of emerging economies (Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2015; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016), in this paper, we mainly focus on EMNCs from ‘mid-range emerging economies,’ which ‘involve hybrid cases between developed and emerging economies’ (Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev and Peng2013: 1296). These mid-range economies include mainly BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa); they are between newly developed economies (e.g., South Korea and Singapore) and traditionally developing economies (e.g., Nigeria and Tajikistan). Therefore, in the course of international expansion, EMNCs from mid-range economies are often facing dual-contextualized conditions (Child & Marinova, Reference Child and Marinova2014; Gaur, Kumar, & Singh, Reference Gaur, Kumar and Singh2014). On the one hand, these EMNCs are in a strong position in a dynamic home market that tends to be technologically lagging behind and with a lower level of institutional development. On the other hand, they are weakly positioned in an advanced foreign market that is technological leading and with more developed, but quite different institutional environment (Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2015). How these EMNCs could be better prepared to adapt to and operate in institutionally ‘difficult’ environments both at home and overseas and balancing the short- and long-term objectives of international expansion is hardly dealt with (Xu & Meyer, Reference Xu and Meyer2013; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016).

Given that ambidexterity refers to an organization’s ability to simultaneously or sequentially engage in two seemingly contradictory activities rather than forcing a selection between two alternatives (Gupta, Smith, & Shalley, Reference Gupta, Smith and Shalley2006; Raisch & Birkinshaw, Reference Raisch and Birkinshaw2008; O’Reilly & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2013), we argue that an ambidexterity perspective may be of immense importance to EMNCs from mid-range economies in the quest to survive and compete effectively against global rivals when facing an unprecedented competitive environment in and out of their home country. In our paper, we define ambidextrous internationalization strategies for EMNCs from mid-range economies as exploitation and exploration of their resources and capabilities in a balanced manner and emphasizing international expansion as a springboard to jointly strengthen their domestic position and explore new opportunities overseas. Equipped with this unique strategic orientation, EMNCs from mid-range economies leverage their existing advantages for short-term survival or profitability while acquiring strategic assets (e.g., patents, brands, and managerial know-how) to offset their competitive weaknesses for long-term growth (Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016).

Furthermore, operating in a constantly changing competitive and institutional environment (Peng, Reference Peng2012; Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev and Peng2013), EMNCs from mid-range economies must creatively and constantly learn, integrate, build, reconfigure internal and external ordinary resources and adjust them to international contingencies (Dixon, Meyer, & Day, Reference Dixon, Meyer and Day2014). In this line of research, an important missing element is: How dynamic capabilities influence EMNCs from mid-range economies in their strategic choices through which they can simultaneously exploit and explore opportunities in global environments. A more dynamic perspective addressing not only ‘why expand internationally’ but also ‘how to expand successfully’ appears imperative to advance the research on the EMNC internationalization (Deng, Reference Deng2013; Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2015). Therefore, for strategy research in this area to flourish and make an enduring contribution we need to consider the extent to which main arguments of dynamic capability theory is suitable to study EMNCs, which are embedded in unique and normally highly volatile environment (Xu & Meyer, Reference Xu and Meyer2013; Dixon, Meyer, & Day, Reference Dixon, Meyer and Day2014; Wu, Chen, & Jiao, Reference Wu, Chen and Jiao2016).

Drawing on the mainstream of dynamic capability theory (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997; Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000; Peteraf, Stefano, & Verona, Reference Peteraf, Stefano and Verona2013; Arndt & Bach, Reference Arndt and Bach2015; Wilden, Devinney, & Dowling, Reference Wilden, Devinney and Dowling2016) in this paper, we examine how EMNCs from mid-range economies use the high-level routines that help EMNEs learn, integrate, build, reconfigure internal and external ordinary resources to address the changing dual context and enhance their competitive edge by formulating ambidextrous internationalization strategies. Specifically, building on the framework of Danneels (Reference Danneels2011), we propose that it is vital for these EMNCs to creatively and constantly recognize, leverage, learn, and realign internal and external ordinary resources and adjust them to international contingencies. These dynamic capabilities constitute the key driving forces for EMNCs to adopt different types of ambidextrous internationalization strategies where they could be effectively engaged in exploitation and exploration sequentially or simultaneously (Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016).

We present our arguments in four steps. First, we provide a brief overview of EMNCs and pinpoint three types of ambidextrous strategies which could be suitable for their international expansion. Then, we focus on the dynamic capability theory in the internationalization context and formulate four dimensions of dynamic capabilities that are particularly useful for understanding EMNC internationalization strategies. Third, we present three ambidextrous internationalization strategies that EMNCs could adopt on the basis of their different sets of dynamic capabilities. We conclude with the discussion of theoretical implications derived from our arguments and suggest directions for future research.

STRATEGIC AMBIDEXTERITY FOR INTERNATIONALIZING EMNCs

EMNCs constitute a tremendous variety of firms (Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2015; UNCTAD, 2016). As a consequence, generalization across this group of MNCs should be done with the utmost caution (Guillén & García-Canal, Reference Guillén and García-Canal2009). Nevertheless, an increasing body of research on the internationalization of EMNCs (Deng, Reference Deng2012; Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev and Peng2013; Child & Marinova, Reference Child and Marinova2014; Awate, Larsen, & Mudambi, Reference Awate, Larsen and Mudambi2015) shows that numerous features do set EMNCs from mid-range economies apart from their counterparts, which might have significantly influenced their international motives and strategies. One of the most startling characteristics may be that EMNCs from mid-range economies tend to be technologically lagging behind and they are faced with less developed institutional frameworks at home country, while are weakly positioned in an advanced foreign market that is technological leading and with more developed, but quite different institutional environment (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Gaur, Kumar, & Singh, Reference Gaur, Kumar and Singh2014). These dual-contextualized environments are not isolated from each other; instead, they are multilaterally influential, directionally consistent, and mutually reinforcing. On top of that, rapid foreign direct investment (FDI) expansion could be a valuable strategy for EMNCs to facilitate fundamental strategic and organizational transformation in response to major domestic institutional changes (Deng, Reference Deng2009; Gubbi, Aulakh, Ray, Sarkar, & Chittoor, Reference Gubbi, Aulakh, Ray, Sarkar and Chittoor2010; Peng, Reference Peng2012). Therefore, EMNCs from mid-range economies are increasingly challenging the traditional views of internationalization of firms, which does not consider serious risks of not internationalizing and the risk of being a perennial late mover in the face of ever-increasing global competition (Gaur, Kumar, & Singh, Reference Gaur, Kumar and Singh2014; Lebedev, Peng, Xie, & Stevens, Reference Lebedev, Peng, Xie and Stevens2015).

Exploitation and exploration strategies provide firms with different incentives to address their international expansion (Turner, Swart, & Maylor, Reference Turner, Swart and Maylor2013; Zhan & Chen, Reference Zhan and Chen2013). The former strategy builds on ongoing changes of existing capabilities, while the latter one focuses on developing new knowledge and capabilities through access to the location-specific advantages in the host countries (March, Reference March1991; Sapienza, Autio, George, & Zahra, Reference Sapienza, Autio, George and Zahra2006). In our study, we define exploitation strategy as the ability to integrate and reconfigure the resource endowments and to effectively deploy them within their specific international settings. EMNCs from mid-range economies developed a set of capabilities based on country-specific advantages in their home market (e.g., the economy of scale and institutional supports), which allows for the incorporation of new, foreign-based assets (Luo & Wang, Reference Luo and Wang2012). On the other hand, we define international exploration strategy as the ability to develop new capabilities or to upgrade existing capabilities particularly through accelerated internationalization such as cross-border M&As in developed economies (Bonaglia, Goldstein, & Mathews, Reference Bonaglia, Goldstein and Mathews2007; Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014). For many EMNCs from mid-range economies, exploration serves as an effective mechanism to access new resources, with capability development and competitive advantage following, rather than leading their internationalization (Deng, Reference Deng2009; Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017). The exploitative and explorative approaches are complementary rather than trade-off strategies because a subsidiary may rely on a parent firm’s competitive advantages and contribute exploitative benefits but, over time, the subsidiary may develop its knowledge base that the parent firm can later exploit (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Reference Gibson and Birkinshaw2004; Lavie, Stettner, & Tushman, Reference Lavie, Stettner and Tushman2010).

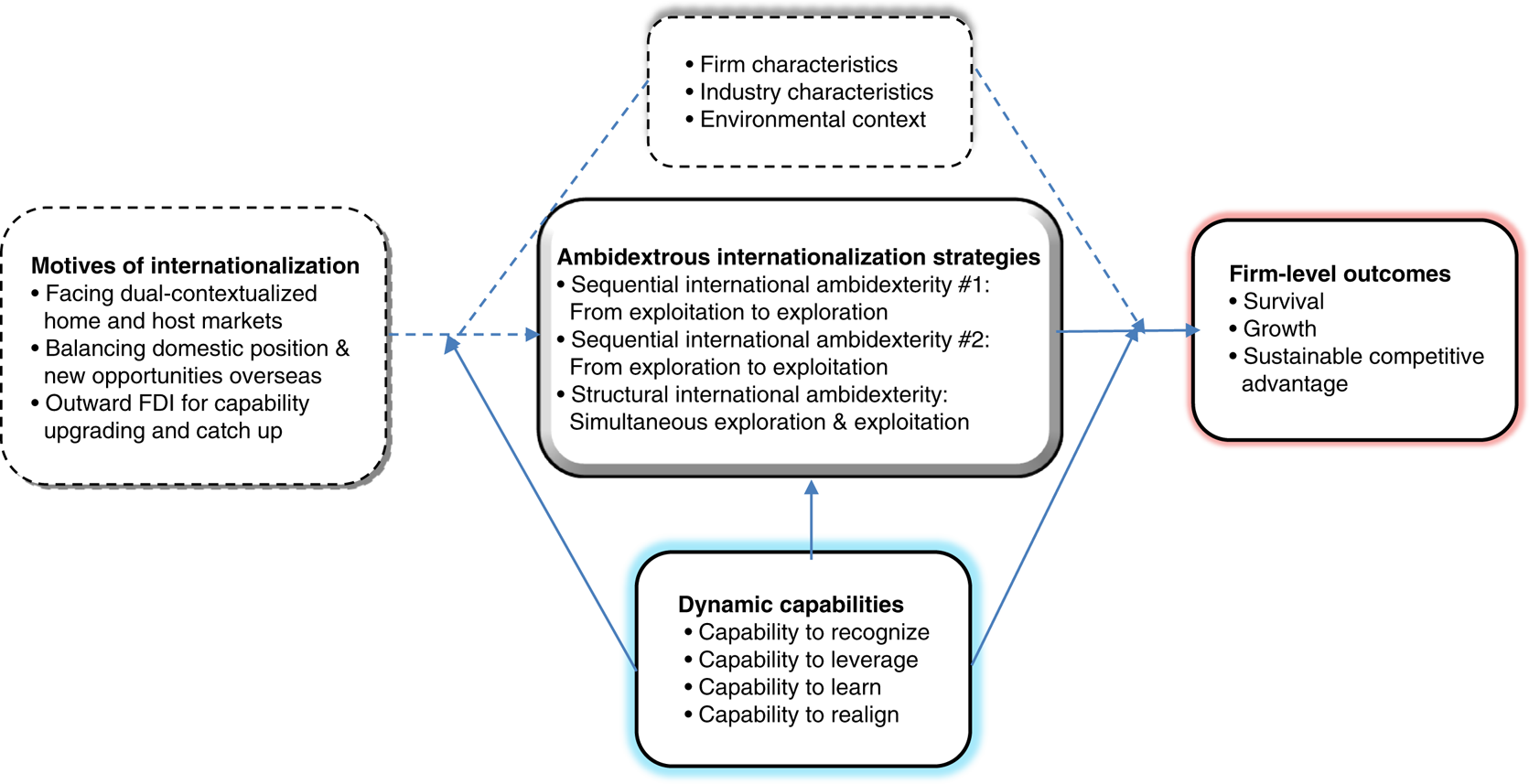

Due to the nature of their linkages, researchers increasingly examine the possibility of an ambidextrous strategy to undertake both exploitative and explorative activities (Boumgarden, Nickerson, & Zenger, Reference Boumgarden, Nickerson and Zenger2012; Hill & Birkinshaw, Reference Hill and Birkinshaw2014). Ambidexterity in its most general definition refers to an organization’s ability to simultaneously or sequentially engage in two seemingly contradictory activities (Gupta, Smith, & Shalley, Reference Gupta, Smith and Shalley2006; O’Reilly & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2013). It is distinguished from trade-offs in emphasizing the simultaneous fulfillment of two disparate and sometimes competing objectives rather than forcing a selection between two alternatives (Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000; Raisch & Birkinshaw, Reference Raisch and Birkinshaw2008). Accordingly, some scholars (e.g., Hill & Birkinshaw, Reference Hill and Birkinshaw2014) contend that the interaction of exploitation and exploration is expected to become a full-blown dynamic capability over time and achieving ambidexterity lies at the heart of a firm’s dynamic capabilities (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997; Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000). In the context of international expansion, dynamic capability denotes a firm’s distinctive capacities and moves organizational resources beyond their roles as static sources of a competitive advantage and makes them important elements in a sustainable, evolving advantage (Luo, Reference Luo2000; Griffith & Harvey, Reference Griffith and Harvey2001). In our study, we emphasize that EMNCs from mid-range economies are strongly motivated and are also capable of building and leveraging such ambidexterity to compensate their late-mover disadvantages by simultaneously taking into account the dual markets they face at home and abroad, pursuing the simultaneous fulfillment of two disparate, and sometimes seemingly conflicting, objectives. Building on our discussion of the literature, we propose that there are three ambidextrous strategies that EMNCs could follow in international expansion, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Ambidextrous internationalization strategies for emerging market multinationals (EMNCs)

The first sequential international ambidexterity could start with exploitation and move toward exploration. Some EMNCs from mid-range economies are more likely to adopt international exploitative strategies first when they enter and compete in less developed countries so as to exploit the competence developed in their home markets, then they come back to home country and even go to developed economies to compete in low-end business domains or niche markets. On the other hand, the second sequential international ambidexterity is just opposite, that is, from exploration to exploitation. Some EMNCs from mid-range economies are likely to first embrace international exploratory strategies for learning and access to strategic assets so as to build and upgrade their competencies mainly through outward FDI and acquisition of existing firms in developed markets; then they leverage these competencies in their huge home country market and/or in less developed markets. Third, structural international ambidexterity is characteristics of simultaneous exploration and exploitation. Some EMNCs from mid-range economies may adopt ambidextrous internationalization strategies to simultaneously exploit and explore the expertise that they developed domestically and acquired abroad for sustainable competitive advantage.

DYNAMIC CAPABILITIES AND AMBIDEXTROUS INTERNATIONALIZATION STRATEGIES FOR EMNCs

Theoretical framework

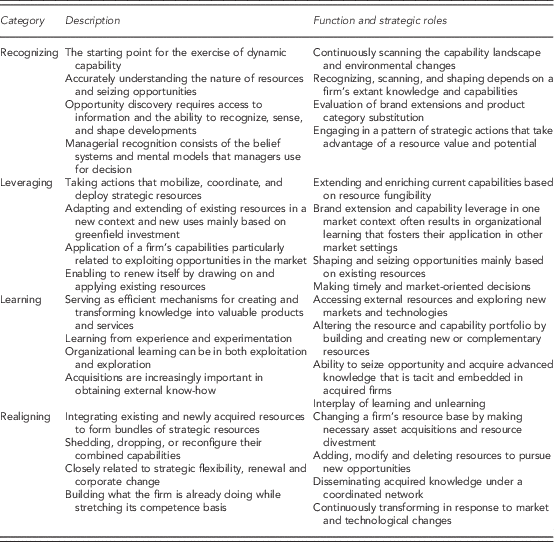

As managing international operations has become a challenging task, numerous studies have been done to explore what factors contribute to the long term and even enduring success of EMNCs in the global marketplace (Ramamurti & Singh, Reference Ramamurti and Singh2009; Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev and Peng2013; Wu, Chen, & Liu, Reference Wu, Chen and Liu2017). We argue that EMNCs from mid-range economies internationalize through a set of ambidextrous internationalization strategies, as we outlined above, and these strategic choices are fundamentally shaped by EMNCs’ different sets of dynamic capabilities. Our theoretical model is shown in Figure 2, which constitutes the rationale behind our arguments regarding the influence of resources and capabilities on ambidextrous internationalization strategies of these EMNCs and subsequently firm-level performance outcomes. Our theoretical model starts with the motives of EMNCs that drive them to undertake overseas investments and acquisitions. Moreover, as EMNCs from mid-range economies choose to internationalize for satisfying their deliberate strategic goals rapidly, they are more likely to do so when they possess unique firm characteristics, are embedded in particular environmental contexts and operate in specific industries. As these two broad ranges of factors and relationships are well discussed in the extant literature (Peng, Wang, & Jiang, Reference Peng, Wang and Jiang2008; Deng, Reference Deng2013; Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014), they are not the focus of this paper, and therefore they are represented by dotted-line arrows and matrices in Figure 2. In the following, we will first define dynamic capabilities for EMNCs from mid-range economies and then propose how dynamic capabilities possessed by these EMNCs have a direct impact on their international ambidextrous strategy formulation and can also serve as moderating effects on their international strategic choices as well as their firm-level performance.

Figure 2 A dynamic capabilities model of internationalization strategies for emerging market multinationals (EMNCs)

Dynamic capabilities for EMNCs

Dynamic capabilities are important in different contexts (Helfat & Winter, Reference Helfat and Winter2011; Arndt & Jucevicius, Reference Arndt and Jucevicius2013), but may be of more value in the rapidly changing environment (Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000; Prange & Verdier, Reference Prange and Verdier2011). As a consequence, dynamic capabilities theory is particularly relevant to EMNCs from mid-range economies as they typically face fast-moving environments and dynamic capabilities provide a mechanism for them to continuously adapt, adjust, or reconfigure their resource base in response to the rapidly changing market and institutional environments. In this paper, we intend to explore the extent to which that dynamic capability theory profoundly affects the internationalization of EMNCs from mid-range economies, thereby making it a powerful perspective for thinking about how EMNCs could effectively cope with global competitive change. Although the literature increasingly shows that dynamic capabilities encourage and facilitate internationalization and global learning (Khalid & Larimo, Reference Khalid and Larimo2012) and are also crucial for foreign market entry and survival (Sapienza et al., Reference Sapienza, Autio, George and Zahra2006), the central concept of dynamic capabilities has not yet been applied to EMNCs and their internationalization, specifically outward FDI (Deng, Reference Deng2013; Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014; Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2015).

As EMNCs from mid-range economies do not often possess certain world-leading capability while facing the unprecedented competitive environment in and out of their home countries (Xu & Meyer, Reference Xu and Meyer2013; Child & Marinova, Reference Child and Marinova2014), we propose that it is crucial for EMNCs to creatively and constantly (1) recognize, (2) leverage, (3) learn, and (4) realign internal and external ordinary resources and adjust them to international contingencies. We highlight below these variables as they represent an important set of elements which could capture emergent dialogues with regard to the deployment of EMNCs’ resources and capabilities and the formulation of their ambidextrous internationalization strategies (Table 1).

Table 1 Categorization of dynamic capabilities

In short, there are four ingredients of dynamic capabilities which are particularly relevant to EMNCs and their international strategic choices, namely, capability to recognize, capability to leverage, capability to learn, and capability to realign. The four factors are correlated, but conceptually distinct, and each has a specific emphasis (Danneels, Reference Danneels2011; Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015). Resource recognition provides EMNCs from mid-range economies with the starting point of deciding which internationalization strategies they are most likely to pursue. Leveraging capability emphasizes a firm’s ability to exploit its existing resources in a timely fashion through adapting market- and institution-related resources and capabilities with environmental changes. Learning capability highlights the importance of obtaining external knowledge, combining it with the internal knowledge base and absorbing it for new use. Realignment capability effectively links a firm’s existing business at home to overseas business opportunities and represents the ability to reconfigure their internal and external competencies with its product market both at home and abroad. Each capability is a necessary but not sufficient condition for sustaining competitive advantage in today’s dynamic marketplace; together they constitute the driving force of ambidextrous internationalization strategies of EMNCs from mid-range economies. Therefore, dynamic capabilities require a strong managerial recognition of resources and the ability to effectively leverage them, to continuously build bundles of new knowledge, and realign them for strategic reconfiguration so as to enhance EMNCs’ sustainable competitive edge both domestically and internationally (Danneels, Reference Danneels2011; Peng, Reference Peng2012; Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016; Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017).

‘Dynamic capabilities are the antecedent organizational and strategic routines by which managers alter their resource base … to generate new value-creating strategies’ (Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000: 1107). Teece, Pisano, and Shuen (Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997) and Teece (Reference Teece2007, Reference Teece2014) similarly argue that dynamic capabilities create value by supporting a firm’s core strategies, allowing the firm to retain a competitive advantage over time. As Michael Porter noted, ‘the value of a particular resource is only manifested if you have a particular strategy which realizes that value’ (Argyres & McGahan, Reference Argyres and McGahan2002: 50). As dynamic capabilities are a key antecedent of a firm’s strategic choice, we contend that it holds the most promise if we assume an indirect link between dynamic capabilities and performance (see Figure 2). In addition, if we reconsider international expansion of EMNCs from mid-range economies in the dynamic capability theory logic, we would be able to identify different types of internationalization strategies, which could be defined as an outcome of their dynamic capabilities over time, as shown in Figure 2. Further, although we acknowledge the perspective on the value of institutions as argued by Peng, Wang, and Jiang, (Reference Peng, Wang and Jiang2008), we advocate that the dynamic capabilities lens constitutes a fruitful approach of accounting for variations in the internationalization strategies of EMNCs and subsequently performance outcomes (Dixon, Meyer, & Day, Reference Dixon, Meyer and Day2010; Ying, Deng, & Liu, Reference Ying, Deng and Liu2016; Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017).

Dynamic capability and sequential international ambidexterity (from exploitation to exploration)

Due to lack of world-leading firm-specific capabilities, some EMNCs from mid-range economies are most likely to emphasize exploitation in less developed economies first, then adopt an explorative strategy to upgrade their capabilities. This is because these EMNCs face a lower knowledge gap in developing markets and their resources may be more readily applied to the institutional settings similar to their home country (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc2008; Luo & Rui, Reference Luo and Rui2009). For instance, CP Group, Thailand’s largest business group, is able to successfully exploit its resource base and realize economies of scale and scope in other emerging markets such as in Indonesia and China. It is also likely that in these emerging markets, EMNCs such as the CP Group may have a competitive advantage relative to developed competitors because it is hard for advanced rivals to change their business model and to compromise their global identity (Guillén & García-Canal, Reference Guillén and García-Canal2009; Kumar, Reference Kumar2009).

In order to effectively implement exploitation strategies, the managerial resource recognition and resource fungibility are critical (Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015; Ying, Deng, & Liu, Reference Ying, Deng and Liu2016). Dynamic capabilities emphasize the key role of strategic leadership in appropriately adapting, integrating, and reconfiguring organizational resources to match changing market and institutional environments (Augier & Teece, Reference Augier and Teece2009; Kor & Mesko, Reference Kor and Mesko2013). Accordingly, to understand how managers exercise dynamic capabilities, it is essential to consider how managers recognize their firms’ resources. Resource recognition refers to the identification of resources and the understanding of their fungibility (Arend & Bromiley, Reference Arend and Bromiley2009; Danneels, Reference Danneels2011), which determines how and to what extent dynamic capability can be exercised. It also helps to explain which international paths firms take and which internationalization strategies are pursued (Gardner, Gino, & Staats, Reference Gardner, Gino and Staats2012). On the one hand, facing global competitive changes, EMNCs from mid-range economies need to fully recognize their resources and renew themselves and inability to do so may have severe consequences (Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017). On the other hand, these EMNCs need to be aware of an institution and understand its potential value in order to act upon it (Deng & Yang, Reference Deng and Yang2015). As resource recognition constitutes the starting point to the exercise of dynamic capability, any EMNC which intends to exercise dynamic capability for rapid internationalization needs to start with an honest self-assessment of its market and institution-related resource base (Khalid & Larimo, Reference Khalid and Larimo2012; Kor and Mesko, Reference Kor and Mesko2013).

Moreover, the ability to leverage these resources is also important as it bestows discretion in executing strategies and flexibility in developing new routines and capabilities (Gardner, Gino, & Staats, Reference Gardner, Gino and Staats2012). Leveraging existing resources involves them to new uses (March, Reference March1991; Raisch & Birkinshaw, Reference Raisch and Birkinshaw2008). Leveraging capabilities initially developed in the home market, or in previous international forays, is crucially important for EMNCs from mid-range economies (Kedia, Gaffney, & Clampit, Reference Kedia, Gaffney and Clampit2012). Different from advanced MNCs’ firm-specific advantages, EMNCs’ capability to leverage country-specific advantages such as low-cost labor, scale economies, and institutional supports, is their primary advantage for internationalization through overseas investment without having any pronounced technological advantage (e.g., Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Ying, Deng, & Liu, Reference Ying, Deng and Liu2016). Moreover, EMNCs increasingly establish linkages with firms in advanced economies to access external knowledge, then leverage these resources at their home market or other markets (Luo & Rui, Reference Luo and Rui2009; Deng & Yang, Reference Deng and Yang2015). This capability leverage practice is also well shown in the concept of strategic roles of foreign subsidiaries (Birkinshaw, Hood, & Jonsson, Reference Birkinshaw, Hood and Jonsson1998; Tallman & Fladomoe-Lindquist, Reference Tallman and Fladomoe-Lindquist2002).

On top of that, over the course of international expansion, EMNCs from mid-range economies typically undergo a process of learning and knowledge accumulation and consolidate existing capabilities, such as by unifying products and brands, and building regional clusters (Luo, Reference Luo2000; Griffith & Harvey, Reference Griffith and Harvey2001). The exploitation strategy is the case when firms prefer to penetrate existing markets and/or expand into a small number of foreign markets to avoid uncertainty and decrease operational risks. Moreover, performance from international exploitation is expected to vary to the extent that resources and capabilities are transferable to a given host country situation (Ying, Deng, & Liu, Reference Ying, Deng and Liu2016). EMNCs from mid-range economies that choose a cost-based strategy by using size- and efficiency-based advantages will be better because they are blessed with an abundant supply of low-cost factors which offer them an opportunity to become global suppliers of labor-intensive products. Also, ‘country of origin effect’ of these EMNCs is not supportive of the high-quality image required for differentiated products (Cuervo-Cazurra, Maloney, & Manrakhan, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Maloney and Manrakhan2007; Deng, Reference Deng2013). Therefore, one option could be that these EMNCs may first target emerging markets (e.g., BRICS countries) where existing resources allow successful entry. Once such operations are established, emerging economies could provide opportunities for growth and global learning in developed economies, albeit primarily in the lower (price-sensitive) segments (Rabbiosi, Stefano, & Bertoni, Reference Rabbiosi, Stefano and Bertoni2012; Deng & Yang, Reference Deng and Yang2015). Firms can later use these opportunities to leverage and build firm resources and capabilities to enter advanced markets (Xia, Ma, Lu, & Liu, Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Liu2013; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016).

In sum, if core competencies are geographically fungible, EMNCs from mid-range economies may achieve a competitive edge in new locations through a resource-exploiting strategy. However, there are several important requirements for this strategy to be successfully implemented. For instance, it is necessary that the strategic models that they develop could allow them to appropriate some of the capabilities in a consistent and sustainable way (Bangara, Freemanb, & Schroder, Reference Bangara, Freemanb and Schroder2012; Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017). Here, their network, in-depth local knowledge, and social capital are critical (Bonaglia, Goldstein, & Mathews, Reference Bonaglia, Goldstein and Mathews2007; Guillén & García-Canal, Reference Guillén and García-Canal2009; Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014). Specifically, we linked exploitation strategy with the leveraging function of dynamic capabilities, leading to the development of operational capabilities and short-term survival. The international exploitative strategy encourages the accumulation of knowledge and experience and reduces the uncertainties of more probing and testing, thereby improving survival and success in foreign markets (Chittoor et al., Reference Chittoor, Sarkar, Ray and Aulakh2009). The foregoing arguments suggest the following:

Proposition 1: Some EMNCs from mid-range economies would first adopt international exploitative strategies when they possess existing resources; such exploitative strategies could help those EMNCs leverage their existing competencies in less developed countries for survival outcome, and then they will come back to the home market and/or adopt international explorative strategies in niche markets in advanced countries for growth outcome.

Dynamic capability and sequential international ambidexterity (from exploration to exploitation)

To the extent that related businesses pursue learning opportunities in developed economies, EMNCs from mid-range economies are more likely to use an explorative strategy and gain an advantage over time, thereby reducing their liability of foreignness (Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995; Deng, Reference Deng2013) or lack of network (Vahlne & Johansson, Reference Vahlne and Johanson2013). Entering other emerging economies may allow for better exploitation, whereas exploration could be curtailed as these economies may not have globally competitive knowledge. To develop advanced knowledge bases in which learning can become world-class, EMNCs from mid-range economies may be forced to enter developed markets to build new competencies (Zahra, Abdelgawad, & Tsang, Reference Zahra, Abdelgawad and Tsang2011; Bangara, Freemanb, & Schroder, Reference Bangara, Freemanb and Schroder2012; Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017). For example, the value creation in overseas acquisitions by EMNCs is typically argued by the ‘springboard’ perspective which describes how EMNCs systematically and recursively leverage international expansion to acquire critically important assets so as to compensate their competitive disadvantages versus their global rivals (Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Chen & Miller, Reference Chen and Miller2012).

When seeking to enter developed economies and internationalize their operations, EMNCs from mid-range economies may, however, face numerous problems and challenges (Cuervo-Cazurra, Maloney, & Manrakhan, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Maloney and Manrakhan2007; Ying, Deng, & Liu, Reference Ying, Deng and Liu2016). For instance, if EMNCs internationalize aggressively, they could end up with a lower likelihood of survival. This suggests an inherent liability of foreignness and lack of experience relative to local firms (Peng, Reference Peng2012; Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014). In addition, although social capital could have positive influences in developing new knowledge (Elango & Pattnaik, Reference Elango and Pattnaik2007), it is also important to note that such relational assets derived from networks and business groups are likely to find their operations impeded in advanced countries due to legal and institutional infrastructure, stringent governance requirements, and other laws restricting collusion between firms (Pant & Ramachandran, Reference Pant and Ramachandran2012; Gaur, Kumar, & Singh, Reference Gaur, Kumar and Singh2014). Furthermore, while growth and survival are closely interlinked, they are clearly distinct. As growth typically involves huge investment, firms often use exploration not to develop short-term outcomes but to enhance long-term performance (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2008, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2013). For those EMNCs which lack competencies, they are more likely to obtain technology and expertise by acquiring innovative firms in advanced economies because acquisitions provide substantially more access to resources and capabilities than greenfield investment (Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014; Deng & Yang, Reference Deng and Yang2015). For example, China’s Pearl River Piano, the world’s largest piano maker, was able to obtain the knowledge it needed by hiring ‘more than ten world-class consultants to assist in improving every aspect of piano making, from design to production to final finish’ (Zeng & Williamson, Reference Zeng and Williamson2007: 52).

The capability to learn could help EMNCs from mid-range economies develop new competencies and upgrade capability particularly in developed countries. In essence, dynamic capabilities are grounded in managerial know-how and organizational learning (Dixon, Meyer, & Day, Reference Dixon, Meyer and Day2010). Accordingly, the more a firm shows its capability to learn, the more it exhibits dynamic capabilities (Danneels, Reference Danneels2011; Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017). First, as EMNCs have been historically weak regarding research and development, the main mode of their learning is experiential learning, with the aim of adapting externally obtained technologies for effective use within EMNC operations (Dyer & Hatch, Reference Dyer and Hatch2006; Xu & Meyer, Reference Xu and Meyer2013). In general, alliances and acquisitions are two primary mechanisms for EMNCs’ organizational learning (Birkinshaw, Hood, & Jonsson, Reference Birkinshaw, Hood and Jonsson1998). EMNCs from mid-range economies could rely on strategic alliances to gain access to external brand and distribution channels; however, they must have resources to get resources (Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000). As a result, acquisitions are becoming an increasingly important tool for EMNCs in attaining the external knowledge and know-how so as to supplement their internal research and development efforts in a timely manner (Deng, Reference Deng2009; Kumar, Reference Kumar2009). Second, institutional differences exist not only in and among different emerging markets, but also between emerging markets and developed markets (Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev and Peng2013; Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2015). Therefore, the capability to learn the ‘rules of game’ in a different market is also crucial for EMNCs.

In sum, developed MNCs expand abroad based on intangible firm-specific assets, whereas EMNCs from mid-range economies start mainly without initial technology resources (Mathews, Reference Mathews2006; Guillén & García-Canal, Reference Guillén and García-Canal2009). Those EMNCs need to engage in exploration strategy because the challenges of the environment may require new business models for the specific context (Child & Rodrigues, Reference Child and Rodrigues2005; Xu & Meyer, Reference Xu and Meyer2013). Exploration enables the learning and capability upgrading, acting as the mechanism which goes beyond manipulating and developing capabilities already in existence (Turner, Swart, & Maylor, Reference Turner, Swart and Maylor2013). While well-established MNCs may also use this strategy, we argue that it would be particularly prominent for EMNCs from mid-range economies as they are characterized by lower levels of resource availability at home (Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Liu2013; Ying, Deng, & Liu, Reference Ying, Deng and Liu2016). This analysis highlights the importance of organizational learning in overcoming EMNCs’ initial resource deficiencies (Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014). By building and upgrading capabilities and corresponding sets of routines to support them, EMNCs could adopt growth-oriented strategies and explore new opportunities in the global marketplace (Zahra, Abdelgawad, & Tsang, Reference Zahra, Abdelgawad and Tsang2011; Deng & Yang, Reference Deng and Yang2015). Therefore, we posit the following:

Proposition 2: Some EMNCs from mid-range economies would first adopt international exploration strategies when they possess learning capabilities; such exploration strategies could help those EMNCs develop new competencies and upgrade capability particularly in developed countries for survive outcome and then help them adopt international exploitation strategies to leverage their enhanced capabilities in their home market and/or in less developed markets for growth outcome.

Dynamic capability and structural international ambidexterity (simultaneous exploration and exploitation)

The ability to achieve ambidexterity has been said to lie at the heart of a firm’s dynamic capabilities (Raisch & Birkinshaw, Reference Raisch and Birkinshaw2008). As a result, ambidexterity can be an integral concept to denote a firm’s dual orientation of integrating external and internal knowledge (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2008, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2013). Our dynamic capabilities model (Figure 2) suggests that an ambidextrous strategy is not necessarily concerned with simultaneously pursuing exploitation and exploration to their maximum per se, but rather involves a dynamic balance that stems from purposefully steering and prioritizing different sets of dynamic capabilities by leveraging, integrating, and reconfiguring resources to match changing environments (O’Reilly & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2013; Turner, Swart, & Maylor, Reference Turner, Swart and Maylor2013). In an international expansion, ambidexterity is essentially a process strategy (Luo, Reference Luo2000; Griffith & Harvey, Reference Griffith and Harvey2001); it combines possession and acquisition of capabilities, mixes short-term and long-term orientations, and integrates environmental adaptation and manipulation (Luo & Rui, Reference Luo and Rui2009; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016). On top of that, we could explore ambidexterity in different stages of internationalization (Arend & Bromiley, Reference Arend and Bromiley2009; Dixon, Meyer, & Day, Reference Dixon, Meyer and Day2010). For example, EMNCs from mid-range economies may focus more on growth and competition but less on short-term profits in the early stage of international expansion, whereas at later stages they may place a higher ‘weight’ on the exploitation of competence and short-term profits (Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017). Hence, we need to determine how context-specific conditions (e.g., time, stage, market, industry, country, and region) affect the optimal degrees of ambidextrous dimensions for specific firms. While EMNCs from mid-range economies may focus on either exploitation or exploration temporarily, they need to continuously modify and build unique capabilities to incorporate both modes of strategic development in a request for sustainable competitive advantage (Pant & Ramachandran, Reference Pant and Ramachandran2012; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016).

In global strategic management, some studies have explored the interplay of exploitative and explorative activities but almost exclusively on advanced MNCs (Harreld, O’Reilly, & Tushman, Reference Harreld, O’Reilly and Tushman2007; Peteraf, Stefano, & Verona, Reference Peteraf, Stefano and Verona2013; Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014). One notable exception is Luo and Rui (Reference Luo and Rui2009) who contend that EMNCs from mid-range economies have stronger motives and abilities to build and leverage such ambidexterity to offset their late-mover disadvantages. For many EMNCs from mid-range economies, international expansion aims to secure new capabilities and upgrade their global value chains particularly through acquisitions of foreign firms so that they are able to reframe global industry structure and alter competitive dynamics (Chen & Miller, Reference Chen and Miller2012; Mueller, Rosenbusch, & Bausch, Reference Mueller, Rosenbusch and Bausch2013; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016). A typical example is Tata Tea’s acquisition of UK-based Tetley Group, one of the largest overseas acquisitions made by an Indian firm. Leveraging the complementary strengths of Tata Tea in production and facilities and Tetley’s globally appealing brand and expertise in blending and keeping track of new consumer trends, Tata Tea over time has been able to transfer itself to a globally visible beverage company rather than just a tea firm in India (Gubbi et al., Reference Gubbi, Aulakh, Ray, Sarkar and Chittoor2010; Gaur, Kumar, & Singh, Reference Gaur, Kumar and Singh2014).

To succeed overseas, EMNCs from mid-range economies must reallocate existing resources and newly acquired competencies in such a way that could best reconfigure their combined capabilities. Specifically, when EMNCs’ technological capabilities have been upgraded and when they try to compete in the high-end market worldwide, the capability to realign market-based and institution-embedded resources are crucial for their sustainable competitive advantage (Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017). This is because while coordinating internal and external knowledge, the realignment of competencies facilitates the integration of knowledge exploration, retention, and exploitation, which may provide major benefits for enhancing EMNCs’ sustainable competitive advantage (Dixon, Meyer, & Day, Reference Dixon, Meyer and Day2010; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016).

In short, when EMNCs from mid-range economies successfully pursues ambidextrous strategies, they are in a great position to achieve sustainable competitive advantage. In essence, it is risky for these EMNCs to focus exclusively on either exploitation or exploration because dynamic environments could make existing products and services swiftly obsolete, thus instantaneously requiring that new ones be developed (Gardner, Gino, & Staats, Reference Gardner, Gino and Staats2012; Xu & Meyer, Reference Xu and Meyer2013; Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017). EMNCs from mid-range economies tend to emerge to prominence in their own markets and benefit from the great dynamism there. Accordingly, one of their international goals is to hold and cement their competitive position and even leadership role in their booming domestic market (Luo & Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2007; Deng & Yang, Reference Deng and Yang2015). While venturing overseas allows them to capitalize on their existing strengths and helps develop new capabilities, it is more important for EMNCs to leverage their upgraded competencies from advanced countries to compete more successfully at home (Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Liu2013; Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017). Despite substantial challenges, an ambidextrous strategy is likely to be the most promising of the three strategies for generating more sustainable rents because it combines both survival and growth orientations (Hill & Birkinshaw, Reference Hill and Birkinshaw2014; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016). Therefore, the following proposition is postulated:

Proposition 3: Some EMNCs from mid-range economies would simultaneously adopt both international explorative and exploitative strategies when they possess strong realignment capabilities; such ambidextrous strategies could help those EMNCs effectively deploy and reconfigure their internal and external competencies in both domestic and overseas markets for sustainable competitive advantage.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

International expansion of EMNCs from mid-range economies is a rapidly evolving phenomenon of central importance not only for academics but also for business practitioners and policymakers (Hoskinsson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev and Peng2013; UNCTAD, 2016). The extant discussion of this phenomenon tends to focus on understanding the unique characteristics of internationalization of EMNCs from mid-range economies or using the emerging market context to test the received MNC theories (Deng, Reference Deng2013; Xu & Meyer, Reference Xu and Meyer2013; Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014). There is a paucity of inquiry of long-term success of EMNCs from mid-range economies as latecomers in the global arena (Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2015; Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017). In addition, much more effort is needed to examine the dynamic process of EMNCs’ international growth as well as its linkage with the knowledge bases both at home and in host countries (Luo & Wang, Reference Luo and Wang2012; Deng & Yang, Reference Deng and Yang2015). Heeding the call for research into the ability to develop knowledge resources through skills acquisition and learning that aid internationalization (Zahra, Abdelgawad, & Tsang, Reference Zahra, Abdelgawad and Tsang2011; Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014; Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2015), our research goal is to identify the underlying antecedents of internationalization strategies of EMNCs from mid-range economies by drawing on insights from dynamic capabilities theory. In so doing, we provide insights into the strategic alternatives that these EMNCs could adopt in their international expansion and the conditions under which these strategies are likely to be more appropriate and effective. Our theoretical premise is that successful EMNCs tend to view complex global environments as opportunity settings within which what strategic goals to pursue and how to pursue them should best match their capabilities.

Contributions to the internationalization of EMNCs

In developing our arguments, our study makes three contributions. First, we connect the literature on internationalization of EMNCs (Deng, Reference Deng2012; Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014; Lebedev et al., Reference Lebedev, Peng, Xie and Stevens2015) with recent advances in dynamic capability theory (Peteraf, Stefano, & Verona, Reference Peteraf, Stefano and Verona2013; Galvin, Rice, & Liao, Reference Galvin, Rice and Liao2014; Teece, Reference Teece2014; Wilden, Devinney, & Dowling, Reference Wilden, Devinney and Dowling2016). While dynamic capabilities research now occupies center stage in the field of strategic management, we have limited knowledge when it comes to how dynamic capabilities shape EMNCs’ internationalization strategies (Deng, Reference Deng2013; Dixon, Meyer, & Day, Reference Dixon, Meyer and Day2014; Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017). By applying dynamic capability theory to the internationalization of EMNCs from mid-range economies, our analyses reinforce the view that dynamic capabilities matter even more today, as a much wider range of these EMNCs are embarking on accelerated internationalization without solid firm-specific advantages when facing complex institutional and market environments (Guillén and García-Canal, Reference Guillén and García-Canal2009; Xia et al., Reference Xia, Ma, Lu and Liu2013; Child & Marinova, Reference Child and Marinova2014). By drawing on dynamic capabilities research in this area, we could better conceptualize the competitive dynamics of EMNCs from mid-range economies (Chen & Miller, Reference Chen and Miller2012; Xu & Meyer, Reference Xu and Meyer2013). Facing global competition, the construct of dynamic capabilities is of particular relevance to the analysis of the internationalization of EMNCs for several reasons. First, dynamic capabilities focus on the variation in a firm’s abilities to adapt quickly to rapidly changing environments (Teece, Reference Teece2014; Wilden, Devinney, & Dowling, Reference Wilden, Devinney and Dowling2016). With competitive change accelerating, EMNCs from mid-range economies need dynamic capabilities to cope with the dynamism because when skillfully leveraged, dynamic capabilities offer bases of competitive advantage. Second, although extant literature provides important insights into how environmental factors lead firms to expand overseas, it tends to ignore the firm-specific processes and capabilities that relate to the effectiveness of internationalization strategies (Gaffney, Kedia, & Clampit, Reference Gaffney, Kedia and Clampit2013; Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev and Peng2013). In this way, dynamic capability theory can draw attention to the crucial role of competencies in enabling firms to execute ambidextrous internationalization strategies successfully. And third, by explicitly applying dynamic capability theory to the internationalization of these EMNCs, specifically outward FDI, we argue that this perspective could shed some light on the ability of EMNCs to capitalize quickly on global opportunities.

On top of that, our central contribution is to extend dynamic capability theory by examining how different sets of dynamic capabilities interact with different types of ambidextrous strategies to affect a firm’s competitive advantage in the context of the internationalization of EMNCs from mid-range economies. By decoupling dynamic capabilities into four conceptually distinct sets, we identify three ambidextrous internationalization strategies through which these EMNCs could compete and catch up with Western MNCs. Given that there has been surprisingly little work that considers strategic options of ambidexterity available to EMNCs based on dynamic capability theory (Hoskisson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev and Peng2013; Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015), we believe that research on these EMNCs could significantly broaden and deepen dynamic capability theory while raising new puzzles and questions in managing the internationalization of EMNCs from mid-range economies. Specifically, we contend that low levels of resources that characterize EMNCs from mid-range economies could provide them with significant opportunities. This important insight allows us to conceptualize three ambidextrous internationalization strategies that these EMNCs can exploit existing resources and/or explore global opportunities. Our arguments help to highlight that resource deficiency can also be an important source of opportunity in the dynamic global marketplace (Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015; Liu & Deng, 2017). Specifically, our dynamic capabilities model suggests that EMNCs from mid-range economies can design foreign strategies around their different sets of dynamic capabilities base for value creation. Sequential international ambidexterity (from exploitation to exploration) is based on dynamic capabilities that are linked to path-dependent learning and knowledge accumulation through international experience, whereas sequential international ambidexterity (from exploration to exploitation) reflects a firm’s ability to achieve new and innovative forms of competitive advantages by using learning capabilities to develop new products and markets as a driver for growth. On top of that, structural international ambidexterity (simultaneous exploration and exploitation) is likely to be the most promising among the three strategies for achieving sustainable competitive advantage because such strategic orientation enables EMNCs to be capable of both exploiting existing competencies and exploring new opportunities simultaneously at home and abroad. However, it is well recognized that the balance between exploitative and explorative imperatives at both home and host markets is one of the most challenging issues confronting MNCs in general and EMNCs from mid-range economies in particular (Hoskinsson et al., Reference Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev and Peng2013; O’Reilly & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2013; Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015; Li & Deng, Reference Li and Deng2017).

Finally, while researchers have studied learning capabilities that underpin long-term success in conventional MNCs, there has been little parallel work that examines the internationalization of EMNCs which forms the focus of this paper. We introduced dynamic capability theory as a framework for considering how EMNCs from mid-range economies manage their capabilities and build new competencies globally by leveraging dual-contextualized competitive environments (Xu & Meyer, Reference Xu and Meyer2013; Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015). In so doing, we argue that it is necessary to consider different sets of dynamic capabilities and understand the actual or potential exercise of these learning capabilities so as to develop effective ambidextrous strategies for EMNCs from mid-range economies. Accordingly, international learning ensues and spurs catch up, and the competitive catch-up process particularly through outward FDI (including aggressive international acquisitions) can be well regarded as a core competency and dynamic capability of EMNCs from mid-range economies (Liu & Deng, Reference Liu and Deng2014; Awate, Larsen, & Mudambi, Reference Awate, Larsen and Mudambi2015). As a consequence, a number of questions merit our attention: How do EMNCs from mid-range economies use their home base role and country effect as a reservoir to absorb and assimilate global resources and also as a catapult of global reach for their advantageous products and capabilities? How do they create a virtuous cycle such that they use global resources to upgrade home base and then use upgraded home base to further leverage global opportunities? How do dynamic capabilities help these EMNCs build, organize, and manage the link between home and foreign operations?

Directions for future research

Our work is exploratory and intends to offer a conceptual framework that should lead to empirical research. The above discussion highlights some important areas for future research inquiries. First, there is a need for more empirical investigation into the role that dynamic context plays in shaping ambidextrous internationalization strategies for EMNCs from mid-range economies. Moreover, there are likely to be additional internationalization strategies beyond what we have identified. What are these strategies, and to what extent do they differ from the three strategies discussed in our paper, and how might each of these strategies interact and mutually reinforce over time? Moreover, what happens to these strategies when dynamic capabilities of EMNCs from mid-range economies increase or decrease over time and vary in different international contexts. Second, given that most EMNCs from mid-range economies tend to view their home country operations as the lynchpin of their global operations, they must effectively establish home country-host country links (technological, organizational, and operational) that create bilateral networks of support. Therefore, it is worthwhile to deepen our knowledge of how these EMNCs use their home base as a reservoir to absorb and assimilate global resources in shaping home-host links and global orchestration, and how macro-level links (e.g., economic ties between home and host countries at the national level) affect micro-level links (e.g., home-host links at the firm level). Third, it seems unlikely that a single theoretical perspective is able to accurately account for all international strategic decisions for EMNCs from mid-range economies. An integrated approach that brings together a variety of theories (e.g., stakeholder theory, resource dependence theory, and signaling theory) might be more fruitful. Finally, examining dynamic capabilities, such as the ability to learn continuously and how the balance and combined dimensions of ambidexterity evolve and coevolve over time, should become more prominent in the study of EMNCs from mid-range economies. Therefore, we see a compelling need for longitudinal studies in more accurately investigating such complex processes (Deng, Reference Deng2012; Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016). Longitudinal studies may also show, for instance, that strategy formulation-implementation linkage changes in short time frames for some products and medium- or long-term time frames for others in different stages of internationalization (Dixon, Meyer, & Day, Reference Dixon, Meyer and Day2010; Meyer & Peng, Reference Meyer and Peng2015). Despite the dynamic nature of dynamic capability theory, only a minority of the studies used longitudinal, time series data and constructs (Kotabe & Kothari, Reference Kotabe and Kothari2016). We hope that our work will provide a more profound and broader picture of that relationship and the questions we ask will inspire future research in this important domain of research.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Felix Arndt and the anonymous reviewers’ constructive comments during the review process. The earlier version of the manuscript was selected as the finalist in the IACMR (International Association for Chinese Management Research) Best Conference Paper Award competition, Beijing, June 18–22, 2014. The authors also thank the participants for their valuable suggestions. This research was partially supported by the National Science Foundation of China (71502160, 71502065), the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71732008), and the Monte Ahuja Endowment Fund for the Chair of Global Business at Cleveland State University, Ohio, USA.