Introduction

Indigenous entrepreneurship – entrepreneurship by Indigenous peoples – has received scholarly attention as entrepreneurship conducted in a cultural context that is distinct from mainstream society (Clydesdale, Reference Clydesdale2007; Ensign, Reference Ensign2021; Henry, Dana, & Murphy, Reference Henry, Dana and Murphy2017a; Klyver & Foley, Reference Klyver and Foley2012) and immigrant entrepreneurship (Jones, Ram, & Edwards, Reference Jones, Ram and Edwards2006; Tavassoli & Trippl, Reference Tavassoli and Trippl2019). Indigenous entrepreneurship is seen as a way to economically empower Indigenous communities, as well as a way to sustain Indigenous culture and the natural environment (Dana & Light, Reference Dana and Light2011; Henry, Dana, & Murphy, Reference Henry, Dana and Murphy2017a). While several studies compare Indigenous entrepreneurship across different Indigenous groups (Fletcher, Pforr, & Brueckner, Reference Fletcher, Pforr and Brueckner2016; Jacobsen, Reference Jacobsen2017), this research tends to adopt a static view of Indigenous entrepreneurial activity. Other studies of what works in fostering Indigenous entrepreneurship, find that Indigenous initiative, ownership, and control of enterprise assistance, forming Indigenous networks of expertise and support (Henry, Mika, & Wolfgramm, Reference Henry, Mika and Wolfgramm2020), and financial and nonfinancial assistance for startups and business growth procure favourable outcomes for Indigenous enterprises (Fortin-Lefebvre & Baba, Reference Fortin-Lefebvre and Baba2020; Jarvis, Maclean, & Woodward, Reference Jarvis, Maclean and Woodward2021; Mika, Reference Mika2016; Papanek, Reference Papanek2006; Zapalska & Brozik, Reference Zapalska and Brozik2017).

Scholarly interest in entrepreneurial ecosystems has emerged because of their capacity to help countries and regions achieve sustainable economic development through support for business environments conducive to entrepreneurship, including Indigenous entrepreneurship (Acs, Stam, Audretsch, & O'Connor, Reference Acs, Stam, Audretsch and O'Connor2017; Alvedalen & Boschma, Reference Alvedalen and Boschma2017; Audretsch, Mason, Miles, & O'Connor, Reference Audretsch, Mason, Miles and O'Connor2018; Brown & Mason, Reference Brown and Mason2017; Ensign & Farlow, Reference Ensign and Farlow2016; Mack & Mayer, Reference Mack and Mayer2016; Malecki, Reference Malecki2018; Roundy, Bradshaw, & Brockman, Reference Roundy, Bradshaw and Brockman2018; Spigel & Harrison, Reference Spigel and Harrison2018). Indigenous entrepreneurship research in relation to entrepreneurial ecosystems is, however, relatively nascent (Mika, Warren, Palmer, & Jacob, Reference Mika, Warren, Palmer and Jacob2018). Even though entrepreneurial ecosystems encompassing Indigenous enterprises develop within the societies they belong to and within the regions in which they operate, few study the evolution and dynamics of such systems. The present study responds to this research gap by addressing the following research question – how does an Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem develop along with the social, economic, and political development of mainstream society? The research question is addressed by comparing Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems in regions from two countries at different stages of development: the Araucanía region in Chile, in South America, and the Bay of Plenty region in Aotearoa New Zealand, in the South Pacific. The theoretical contribution here is to better understand the dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems in developing and developed countries and their potential to advance aspirations for Indigenous self-determination through entrepreneurship (Mika et al., Reference Mika, Warren, Palmer and Jacob2018).

We first review literature relating to Indigenous entrepreneurship and Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems, which is followed by an outline of the methods used for data collection and analysis. Results are examined for each Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem, followed by a comparison. Finally, a discussion of the implications for Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems is followed by managerial implications, limitations and further research, and the conclusion.

Indigenous entrepreneurship

Indigenous enterprises are established to achieve both financial benefits for their owners and nonfinancial benefits such as employing Indigenous individuals, maintaining Indigenous culture, and protecting local environments (Giovannini, Reference Giovannini2014; Maguirre, Portales, & Bellido, Reference Maguirre, Portales and Bellido2017; Spencer, Brueckner, Wise, & Marika, Reference Spencer, Brueckner, Wise and Marika2016). Indigenous culture and the local environment are often found to be part of the product, particularly in relation to Indigenous artisanship and Indigenous tourism (Bremner, Reference Bremner2013; Hillmer-Pegram, Reference Hillmer-Pegram2016; Ratten & Dana, Reference Ratten and Dana2015; Zapalska & Brozik, Reference Zapalska and Brozik2017). When the local environment is part of a product, Indigenous entrepreneurs and local people benefiting from their activities have an extra incentive for protecting it. Similarly, when Indigenous culture is part of a product, Indigenous entrepreneurs have an additional incentive to maintain and adapt Indigenous culture (Bernardo & Samuel, Reference Bernardo and Samuel2015; Lemelin, Koster, & Youroukos, Reference Lemelin, Koster and Youroukos2015; Pereiro, Reference Pereiro2016). When financial incentives put the environment under stress, Indigenous entrepreneurs are more likely to protect the environment because land is culturally important (Rout, Reid, & Mika, Reference Rout, Reid and Mika2020).

Indigenous tribes have ancestral roots in particular locations, with natural features (e.g., mountains, rivers, and lakes) playing an important part in Indigenous traditions, culture, and identity (Mika, Reference Mika, Joseph and Benton2021c; Swanson & DeVereaux, Reference Swanson and DeVereaux2017). For some Indigenous enterprises, remote geographic locations can be infused into their products, particularly in Indigenous tourism (Fuller, Buultjens, & Cummings, Reference Fuller, Buultjens and Cummings2005; Jacobsen, Reference Jacobsen2017; Lemelin, Koster, & Youroukos, Reference Lemelin, Koster and Youroukos2015). At the same time, remote locations may constrain access to infrastructure, human capital, and markets (Clydesdale, Reference Clydesdale2007; Cornell, Jorgensen, Record, & Timeche, Reference Cornell, Jorgensen, Record, Timeche and Jorgensen2007; Felzensztein, Gimmon, & Aqueveque, Reference Felzensztein, Gimmon and Aqueveque2013). Operating in remote regions may also make it difficult for Indigenous entrepreneurs to integrate into global supply chains (Jacobsen, Reference Jacobsen2017). Moreover, nascent Indigenous entrepreneurs also experience challenges commonly faced by all entrepreneurs (Chan, Iankova, Zhang, McDonald, & Qi, Reference Chan, Iankova, Zhang, McDonald and Qi2016; Whitford & Ruhanen, Reference Whitford and Ruhanen2014), such as inexperience and illegitimacy attributable to the absence of trading history (Hyytinen, Pajarinen, & Rouvinen, Reference Hyytinen, Pajarinen and Rouvinen2015), and because important stakeholders tend to have biased views due to colonial history and ongoing inequality (Ruhanen & Whitford, Reference Ruhanen and Whitford2018; Shirodkar, Reference Shirodkar2021).

Apart from often being part of the product sold by Indigenous enterprises, Indigenous culture may be an enabler affording Indigenous entrepreneurs and their organisations access to modes of organising rooted in Indigenous culture and values that are unavailable to non-Indigenous entrepreneurs. Such modes of organising may allow them to mobilise Indigenous human and knowledge resources that are difficult to assemble using mainstream approaches (Awatere, Mika, Hudson, Pauling, Lambert, & Reid, Reference Awatere, Mika, Hudson, Pauling, Lambert and Reid2017; Pereiro, Reference Pereiro2016). Indigenous enterprises may rely on Indigenous values (Kawharu, Tapsell, & Woods, Reference Kawharu, Tapsell and Woods2017) or follow Indigenous practices in their operation (Barr & Reid, Reference Barr and Reid2014), thus requiring expertise in Indigenous culture for their management. For instance, Indigenous practices in Māori enterprises typically include long planning horizons (25–100 years), pursuit of multiple objectives (social, cultural, economic, environmental, and spiritual), prioritising intergenerational wellbeing, building community consensus and participation, and the application of cultural values such as kaitiakitanga (stewardship) and manaakitanga (generosity) (Mika, Colbourne, & Almeida, Reference Mika, Colbourne, Almeida, Laasch, Suddaby, Freeman and Jamali2020; Mika & O'Sullivan, Reference Mika and O'Sullivan2014; Spiller, Erakovic, Hēnare, & Pio, Reference Spiller, Erakovic, Hēnare and Pio2011). Tūaropaki is an example of a sustainable Māori enterprise that integrates Māori values into the operation of its diverse land-based economic activities (Mika, Colbourne, & Almeida, Reference Mika, Colbourne, Almeida, Laasch, Suddaby, Freeman and Jamali2020) while Māori tourism enterprises on the Whanganui river are using Indigenous knowledge to negotiate the limits of tourism growth on the environment (Mika & Scheyvens, Reference Mika and Scheyvens2021).

Indigenous practices in Mapuche enterprises include prioritising human wellbeing over profit, a collective approach to enterprise with family and community at the centre, acknowledgement of rituals and the role of spiritual healers, and sharing with customers a craft person's spirit imbued in their products, which inhibits upscaling beyond household production (Galanova, Reference Galanova2014). Other Indigenous practices include establishing relationships by sharing traditional food and beverage, contending at times with expressions of envy, accepting that attracting tourists deprives neighbouring enterprises of the same, and interchangeably self-identifying as Mapuche and as farmers (Di Giminiani, Reference Di Giminiani2018). Mapuche entrepreneurs agitate for public investment in roading, the primary and uneven means by which visitors reach rural enterprises, and they recognise that entrepreneurship is likely to only partially succeed in averting the precarity of low-paying farm jobs and subsistence farming (Di Giminiani, Reference Di Giminiani2018).

Indigenous human resources may possess unique knowledge of the local environment and local flora and fauna relevant to product development (Ratten & Dana, Reference Ratten and Dana2015). Nurturing local Indigenous social networks can provide access to unique resources, including cultural and historic sites or living cultural experiences (Carr, Ruhanen, & Whitford, Reference Carr, Ruhanen and Whitford2016; Erdmann, Reference Erdmann2016; Mendoza-Ramos & Prideaux, Reference Mendoza-Ramos and Prideaux2017). Indeed, because Indigenous culture is maintained and propagated via Indigenous social networks, it may be difficult or impossible to delineate clearly Indigenous social networks from Indigenous culture. However, benefiting from access to Indigenous culture and Indigenous social networks, Indigenous enterprises may promote both Indigenous culture (Swanson & DeVereaux, Reference Swanson and DeVereaux2017) and the rebuilding of Indigenous communities and nations (Henry, Dana, & Murphy, Reference Henry, Dana and Murphy2017a; McInnis-Bowers, Parris, & Galperin, Reference McInnis-Bowers, Parris and Galperin2017). At the same time, one can anticipate that some of the social capital in Indigenous social networks may be negative (Arregle, Batjargal, Hitt, Webb, Miller, & Tsui, Reference Arregle, Batjargal, Hitt, Webb, Miller and Tsui2015; Mika & O'Sullivan, Reference Mika and O'Sullivan2014), because cultural norms may require them to maintain connections that impede their ability to act or make operations more expensive (Corey et al., Reference Corey, Webb, Manolis, Fordham, Austin, Fukuda and Saalfeld2017). Furthermore, in areas where Indigenous culture has weakened as a consequence of colonisation, Indigenous social networks may be fractured with the loss of cultural knowledge (Collins, Morrison, Basu, & Krivokapic-Skoko, Reference Collins, Morrison, Basu and Krivokapic-Skoko2017), exacerbated by the migration of Indigenous youth to urban areas for education and work opportunities (Mika, Smith, Gillies, & Wiremu, Reference Mika, Smith, Gillies and Wiremu2019b).

Indigenous entrepreneurship may have positive effects on regions where it is practiced, economically empowering an Indigenous population (Eichler, Reference Eichler2018; Mendoza-Ramos & Prideaux, Reference Mendoza-Ramos and Prideaux2017), empowering women (Ratten & Dana, Reference Ratten and Dana2017; Zapalska & Brozik, Reference Zapalska and Brozik2017), protecting and promoting Indigenous culture (Henry, Reference Henry2017), and protecting the environment (Eichler, Reference Eichler2018; Mika, Reference Mika2021a; Phillips, Woods, & Lythberg, Reference Phillips, Woods and Lythberg2016; Whitford & Ruhanen, Reference Whitford and Ruhanen2016). Positive effects at the local level can extend to the level of the country, for example, creating an image of a country as a desirable tourism destination (Carr, Ruhanen, & Whitford, Reference Carr, Ruhanen and Whitford2016). In many areas, however, Indigenous entrepreneurship is unlikely to be successful without government support (Zapalska & Brozik, Reference Zapalska and Brozik2017). Government programmes promoting Indigenous entrepreneurship should, therefore, be maintained, while still evaluating such programmes (Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Brueckner, Wise and Marika2016). There is evidence that such programmes are more effective when they fit Indigenous culture (Collins, Reference Collins2017; Mika, Reference Mika and Katene2018; Yonk, Hoffer, & Stein, Reference Yonk, Hoffer and Stein2017).

Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems

Entrepreneurial ecosystems have their roots in business ecosystems of aligned firms co-creating dynamic capabilities (Mason & Brown, Reference Mason and Brown2014b), in business network theory as the interaction of diverse entrepreneurs (Daniel, Medlin, O'Connor, Statsenko, Vnuk, & Hancock, Reference Daniel, Medlin, O'Connor, Statsenko, Vnuk and Hancock2016), and in clusters of related firms and support infrastructure (Porter, Reference Porter1998). While the components of entrepreneurial ecosystems are reasonably well-defined (Ensign & Farlow, Reference Ensign and Farlow2016; Isenberg, Reference Isenberg2010), replicating them is not (Mason & Brown, Reference Mason and Brown2014a; Mazzarol, Reference Mazzarol2016). A complicating factor is that there is no agreement on the exact meaning of the concept, apart from the idea that an entrepreneurial ecosystem is bounded and has entrepreneurship happening within its scope, prompting Spigel and Harrison (Reference Spigel and Harrison2018) to refer to the concept as a chaotic conception.

Some definitions incorporate success as a prerequisite for entrepreneurial ecosystems (Alvedalen & Boschma, Reference Alvedalen and Boschma2017). For instance, Stam and Spigel (Reference Stam and Spigel2016) define an entrepreneurial ecosystem as ‘a set of interdependent actors and factors coordinated in such a way that they enable productive entrepreneurship within a particular territory’ (p. 1), thus emphasising ‘productive entrepreneurship’. Mason and Brown (Reference Mason and Brown2014b) mention ‘high growth firms’ (p. 5) and ‘serial entrepreneur’ in their definition. Spigel and Harrison (Reference Spigel and Harrison2018) suggest ‘high-growth entrepreneurship’ (p. 151) is necessary while Isenberg (Reference Isenberg2010) defines entrepreneurial ecosystems broadly as constructed ‘environments that nurture and sustain entrepreneurship’ (p. 42). Other definitions of an entrepreneurial ecosystem do not incorporate the notion of success such as Qian, Acs, and Stough (Reference Qian, Acs and Stough2013) whose definition focuses on institutional factors that influence entrepreneurial opportunities. Entrepreneurial ecosystems support hybrid Indigenous enterprises, which are firms that simultaneously value economic and cultural benefits for their owners and for their Indigenous communities (Henry, Dana, & Murphy, Reference Henry, Dana and Murphy2017a; Henry, Newth, & Spiller, Reference Henry, Newth and Spiller2017b; Logue, Pitsis, Pearce, & Chelliah, Reference Logue, Pitsis, Pearce and Chelliah2018; Maguirre, Portales, & Bellido, Reference Maguirre, Portales and Bellido2017; Mika, Fahey, & Bensemann, Reference Mika, Fahey and Bensemann2019a; Scheyvens, Banks, Meo-Sewabu, & Decena, Reference Scheyvens, Banks, Meo-Sewabu and Decena2017). We, therefore, formulate a definition of an Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem that does not incorporate economic success.

The concept of an Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem was introduced by Dell, Mika, and Warren (Reference Dell, Mika and Warren2017), who, however, did not explicitly define the concept. In the spirit of Dell, Mika, and Warren (Reference Dell, Mika and Warren2017), we build on the definition of an entrepreneurial ecosystem by Roundy, Bradshaw, and Brockman (Reference Roundy, Bradshaw and Brockman2018) to define an Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem as a self-organised, adaptive, and geographically bounded community that contributes to regional development and local economic activity of Indigenous agents whose interactions result in Indigenous enterprises forming and dissolving over time. By Indigenous agents we refer to agents whose behaviour is influenced by Indigenous culture, which implicitly suggests a cultural boundary for the Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem. Indigenous entrepreneurs are agents of Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems. Other agents are suggested by the structure of the Indigenous community, as individuals and groups in the community who may influence the Indigenous enterprises and the resources available to them (e.g., access to Indigenous cultural sites) (Barr, Reid, Catska, Varona, & Rout, Reference Barr, Reid, Catska, Varona and Rout2018; Scheyvens et al., Reference Scheyvens, Banks, Meo-Sewabu and Decena2017; Zapalska & Brozik, Reference Zapalska and Brozik2017).

Government support programmes are often identified as enablers of Indigenous enterprises (Curry, Donker, & Michel, Reference Curry, Donker and Michel2016; Erdmann, Reference Erdmann2016; Mika, Reference Mika and Katene2018; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Brueckner, Wise and Marika2016; Zapalska & Brozik, Reference Zapalska and Brozik2017). However, we place most government support agencies interacting with Indigenous enterprises outside the Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem (forming part of the system's institutional environment), because they operate primarily according to mainstream cultural logic and values (ultimately accountable to mainstream society) (Rout, Reid, Te Aika, Davis, & Tau, Reference Rout, Reid, Te Aika, Davis and Tau2017; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Brueckner, Wise and Marika2016), rather than according to Indigenous cultural values (Warren, Mika, & Palmer, Reference Warren, Mika and Palmer2017). Di Giminiani (Reference Di Giminiani2018, p. 275) elucidates this tension by characterising state assistance for Mapuche entrepreneurs as the ‘governance of hope’. By this he means the state's ability to capitalise on hope as an agentive resource entrepreneurs employ in their quest for self-realisation of economic autonomy. According to Di Giminiani (Reference Di Giminiani2018) this neoliberal ‘project’ is, however, perpetually incomplete because the ‘bonds of dependency’ (p. 268) on welfare assistance and low-paying farming jobs are replaced by new dependencies on competitive bidding for funded projects, reinforcing colonial hierarchies, mistrust in the state, and marginalisation of Mapuche entrepreneurs.

Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems exist within institutional environments determined by mainstream society, with many of these institutions being generic (e.g., legal and banking systems) (Grimes, Reference Grimes2009). Institutions are also created to promote Indigenous peoples' wellbeing, evident in government-instituted Indigenous business support agencies (Jacobsen, Reference Jacobsen2017; Ruwhiu, Amoamo, Ruckstuhl, Kapa, and Eketone, Reference Ruwhiu, Amoamo, Ruckstuhl, Kapa and Eketone2021; Zapalska & Brozik, Reference Zapalska and Brozik2017). Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems may evolve as sub-ecosystems whose elements are better attuned to serving underserved groups of entrepreneurs with existential purposes driven more by community logic than market-growth logic (Malecki, Reference Malecki2018). At the same time, Indigenous culture (as culture in general) is resilient in the face of external pressure (Bruijn & Whiteman, Reference Bruijn and Whiteman2010; Chavance, Reference Chavance2009). Indeed, the authenticity of Indigenous culture, on which the business models of Indigenous enterprises often rely, depends on the preservation of Indigenous identity (Warren, Mika, & Palmer, Reference Warren, Mika and Palmer2017; Zapalska & Brozik, Reference Zapalska and Brozik2017). Thus, because Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems face an internal pressure towards cultural continuity, one can expect that the systems evolve along with their institutional environments, reflecting the development of the mainstream political, economic, and social systems of their countries.

Method

This study compares Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems in two regions representing different stages of ecosystem development: a relatively early one (in Araucanía, Chile) and a relatively advanced one (in the Bay of Plenty, Aotearoa New Zealand). These regions were compared because of their shared identity as Indigenous peoples, differentiated experiences of colonisation, aspirations for self-determination, a history of country-level cooperation on trade, and differences in their social, economic, and political development.

Using the United Nations’ (2020) classification system, Chile is regarded as a developing country while Aotearoa New Zealand is regarded as a developed country. In 2017, Aotearoa New Zealand ranked 16th globally with a human development index (HDI) value of .917, and Chile ranked 44th with a value of .843 (United Nations Development Programme, 2020). Since 1990, Aotearoa New Zealand has moved from an HDI value of .818 to .917 in 2017, denoting a rise of .99 basis points, or 12.10%. Chile has moved from an HDI value of .701 in 1990 to .843 in 2017, a gain of .142 basis points or 20.26%. Chile's current value of .843 was achieved by New Zealand in 1995.

Araucanía, Chile is a region of 31,842 km2 with a population of 957,224 in 2017 (Brinkhoff, Reference Brinkhoff2017). The Bay of Plenty, Aotearoa New Zealand, is a smaller region, with an area of 12,231 km2 and a population of 308,499 in 2018 (Stats, Reference Stats2018). Both regions are located away from major urban centres and are popular tourism destinations (Figueroa, Herrero, Báez, & Gómez, Reference Figueroa, Herrero, Báez and Gómez2018; Pike & Ives, Reference Pike and Ives2018), with their natural environments and substantial Indigenous populations serving as bases for attracting visitors. According to census data, 27% of the Araucanía region's population are Mapuche and 26% of the Bay of Plenty region's population are Māori. As part of their colonial histories, in both regions Indigenous people were violently subjected to and resisted colonisation (O'Malley & Kidman, Reference O'Malley and Kidman2018; Vergara & Mellado, Reference Vergara and Mellado2018).

Indigenous small business owners were interviewed in person. Convenience sampling was used; however, an attempt was made to ensure that the businesses were representative of their regions, based on the researcher's judgement. One co-author is Māori and another co-author is Mapuche. Their personal connections facilitated access to the participants, and their experience helped to validate the results. Data consisted of Indigenous entrepreneurs' interview transcripts, observation, and government documents. The interview schedule focused on the entrepreneurs' connections to the region, their entrepreneurial strategies, and the roles of government and other stakeholders. On-site interviews enabled participants to be authentic in discussing culturally laden issues (Henry, Dana, & Murphy, Reference Henry, Dana and Murphy2017a). Interviews were appropriate for exploratory research (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2012).

In Araucanía, interviews with 10 Mapuche entrepreneurs were conducted in December 2017. Most of the enterprises were informal, offering Indigenous tourism services or Indigenous art with one exception – an agricultural business. All interviewees except for one was female, with ages ranging from 40s to 50s. All of the interviews were in Castellano, with transcripts translated into English. In the Bay of Plenty, interviews with 10 Māori entrepreneurs were conducted in June 2018. The sample consisted of small, registered companies, most of which employed fewer than 10 fulltime employees, from a broad range of sectors, including fashion and souvenir retail, adventure sports, tourism consultancy, and accommodation. Genders were evenly split between male and female, with ages ranging from 30s to 60s. Interviews were in English, with Māori occasionally spoken.

Documents describing the institutional environment were sourced online using keywords including ‘Māori entrepreneurs’ and their equivalents for Mapuche (in Spanish). Documents explicitly addressing Indigenous-related issues were selected based on their relevance to the respective entrepreneurial ecosystems, resulting in 10 documents relevant to the Bay of Plenty (Bay of Connections, 2011a, 2011b, 2014; Māori Economic Development Advisory Board, 2016; Māori Economic Development Panel, 2012a, 2012b; Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment, 2019; Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2018; Rotorua District Council, 2012a; Rotorua Economic Development Limited, 2018) and nine documents relevant to Araucanía (Corporación Nacional de Desarrollo Indígena, 2018; Ministerio de Agricultura, 2018; Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, 2015, 2017, 2018a, 2018b, 2019; Ministerio de Economía, 2016; Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, 2017). Documents in Spanish were translated into English for qualitative analysis.

Thematic analysis was used (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2012), involving first-order (informant-centric) and second-order analysis (theory-centric) stages (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2012). Two of the co-authors coded the data independently, followed by discussion. Themes in the coding structure consisted of entrepreneurial identities, regional and global connections, enterprise formation, government assistance, and the roles of culture, family, and tribes.

Findings

Mapuche entrepreneurship in the Araucanía region of Chile

The Mapuche entrepreneurs we interviewed own and operate mainly micro-small family enterprises. They include a female entrepreneur with a professional background deeply concerned about environmental (water shortages) and political issues affecting her community (C1); another who went to school in the city, and upon finishing high school created a business for herself as an artisan using spinning skills she learned from her mother (C2); another entrepreneur (C3) in a community of mainly farming families who was concerned about government funding outside advisors rather than investing in Indigenous enterprises; an entrepreneur (C4) who has a passion for preserving her culture, instilling this in her children, and producing handicrafts in association with other Indigenous artisans; an entrepreneur who runs a family business that provides traditional food so tourists can experience Mapuche culture as ‘people of the land’ (C5); an entrepreneur whose family has always made textiles and handicrafts, but whose studies in administration have helped her form and mange a cooperative of artisans (C6); an entrepreneur who started a woodwork business he runs from a shop with his son (C7); an entrepreneur who returned to her rural roots and became a wine maker so when visitors drink her wine they ‘take my ancestral knowledge with them’ (C8); an entrepreneur who offers food, and now accommodation, to visitors in a ruca – a traditional Mapuche dwelling, she and her husband built after years of his working as a grower (C9); and an entrepreneur who established a business selling flowers, whose son converted a three-generation old family-owned mill into a museum (C10).

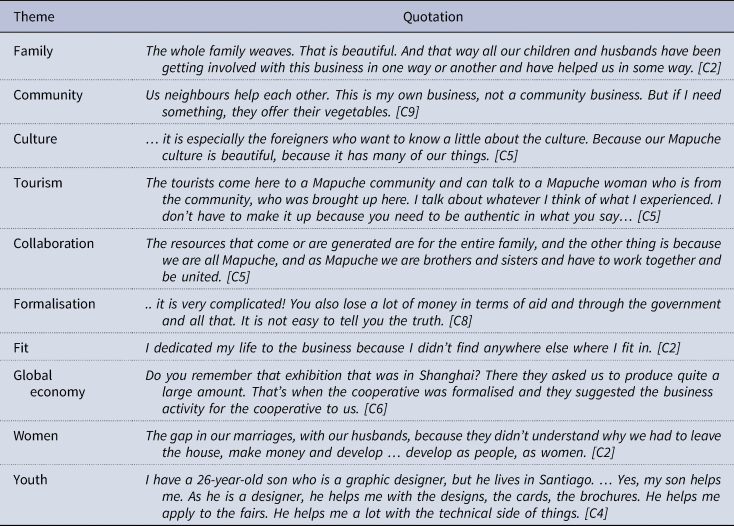

Selected quotations of Mapuche entrepreneurs' views are presented in Table 1. Mapuche enterprises are closely entwined with their families (all of the entrepreneurs interviewed were running family businesses) and with the local community, which provide support. Culture is frequently part of the product. For tourists, culture is a major attraction, and the Mapuche Indigenous tourism experience is a cultural experience. Furthermore, artefacts created by Mapuche artisans are sold as cultural products. Tourism plays an important role, with ruca a material manifestation of Mapuche culture valued by tourists.

Table 1. Mapuche entrepreneurs' selected quotations

Mapuche businesses are often cooperatives, and successful businesses rely on projects initiated or supported by government organisations, such as Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias, Corporación de Fomento de la Producción de Chile, and Instituto de Desarrollo Agropecuario. These institutions help to create business-related knowledge and to obtain investment for basic utilities. In particular, entrepreneurs need such support for establishing an enterprise, which often makes it necessary to employ external advisors. While formalised enterprises do exist, formalisation, which can expedite access to government funding and opportunities, is not considered worth the cost.

Even formalised enterprises may exist on the boundary between the official economy and the informal Mapuche economy, as facilities created to become formalised may not be in use. On the one hand, Mapuche entrepreneurs are closely connected to the region and to Mapuche culture where consumption of agricultural products they produce is an important part of their lives. On the other hand, they are part of the global economy, and remote events such as the appointment of a new US ambassador in Santiago or the Shanghai world expo create opportunities for some of them.

Culturally as well, Mapuche entrepreneurs belong simultaneously to two worlds, with the government, purposefully or not, pressuring them to align closer to mainstream culture. To benefit from government projects, Mapuche entrepreneurs need to master bureaucracy and attach to social, professional, and government networks that may be unfamiliar to them. Formalised enterprises are also required to build facilities that are in effect material manifestations of mainstream culture. When Mapuche culture is, in itself, part of the product, entrepreneurs need to find a suitable place at the boundary of the two cultures (belonging to mainstream culture for compliance and legitimacy with authorities and funders; and belonging to traditional Mapuche culture for cultural authenticity).

There are indications that Mapuche enterprises that distinguish themselves via Mapuche culture are more successful than more generic enterprises, for example, agricultural producers who supply undifferentiated produce. When culture is part of a product, entrepreneurial activity serves to maintain the culture. At the same time, there is evidence that entrepreneurial activity influences Mapuche culture, with new types of authentic artefact being created or artefacts that are no longer part of living Mapuche culture being re-introduced for commercial purposes such as inlaying traditional Mapuche jewellery designs in wooden furnishings (participant C7) and accommodation in traditional thatched huts (participant C8). Women play an important role in Mapuche entrepreneurship. The social network relied on for support may be female-to-female. Furthermore, women may be entrepreneurial leaders, and occasionally and reluctantly, men may be followers.

Even though the government is attempting to revitalise the region by, for example, supporting Mapuche entrepreneurs and providing basic infrastructure, there is an ongoing exodus from the region, with younger Mapuche leaving to find jobs elsewhere. Such an exodus occasionally creates opportunities for entrepreneurs who remain, as younger Mapuche outside the region retain family ties and become a source of ideas and expertise. An example of this is a Mapuche entrepreneur whose graphic designer son lives in Santiago, but still helps with designing collateral and organising events (participant C4).

Māori entrepreneurship in the Bay of Plenty region

The Māori entrepreneurs we interviewed are diverse. They include a fashion designer who was raised to see that being Māori and commercially successful is normal (A1); a food manufacturer with a long family history in hospitality who wanted to expand on his parents' business of selling Māori food at markets (A2); an entrepreneur who started out as an adventure tourism guide becoming a business owner, who has plans to move into a different business entirely (A3); an entrepreneur who originally starting a rafting business in another tribal district but moved to the region with the encouragement of a local Māori business leader (A4); an experienced carver who turned his art into a business that provides young Māori with pathways to work and a commercial outlet for their artistic talent (A5); a Māori consultant and entrepreneur with significant tourism industry experience who advises mainstream and Māori enterprises (A6); an accommodation provider from a tribe outside the region with a penchant for health and wellbeing entrepreneurship (A7); a Māori tourism executive who together with her business partner seized an opportunity to connect tourists with Māori tourism offerings through e-commerce (A8); and two entrepreneurs (A9 and A10) who established a whānau (family) owned adventure tourism business that branched out into luxury tourism.

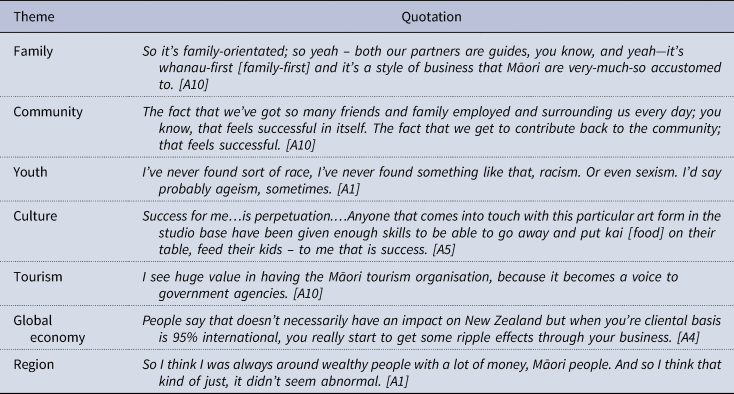

Māori entrepreneurs' views on the key themes are indicated by selected quotations in Table 2. Māori enterprises are entwined with family to different extents, ranging from an explicit focus on hiring family members to family history influencing the entrepreneur. Similarly, the extent of reliance on the local Indigenous community varies, from access to members of the Indigenous community forming an essential part of the product to little differentiation. Nonetheless, offering opportunities to young Māori is often emphasised.

Table 2. Māori entrepreneurs' selected quotations

The distinction between Māori and non-Māori is not always the most important divide. For instance, a young female Māori entrepreneur considered age a more important distinction than race or gender. In other cases, the distinction between Kiwi (a broad term usually understood as encompassing all New Zealanders) and non-Kiwi was important with the emphasis on hiring Kiwi workers and embracing non-Kiwi as part of the family in the firm.

For most of the entrepreneurs, Māori culture was part of their product. This included explaining Māori history to customers as part of a river rafting experience or Māori culture forming the product's core. In some cases, Māori entrepreneurs appeared to be custodians of not only Māori culture, but also of colonial British culture. For instance, a local church was part of an offering along with a marae (the sacred grounds in front of a village meeting house and surrounding buildings) and Māori food fused with English food. In one case where Māori culture was not immediately apparent as part of the product (running a hostel themed on US popular culture), the influence of Māori culture could be discerned in the way the business was managed (in the words of the participant (A7), ‘as a village’).

All of the participants considered being Māori an asset, but for different reasons, including sustaining aspects of Māori culture (e.g., jade carving). None of the entrepreneurs indicated negative discrimination (for instance, difficulty in accessing business networks) because of their Māori identity. Not all of the participants, however, valued approaches to management inspired by Māori culture, with some of them not emphasising this aspect and with one participant (a food manufacturer) essentially defining his strategy and his approach to management via rejecting Māori ways of doing things. In his experience, there was a pattern of relying on voluntary whānau (family) support and a fear of public consternation at pricing products with adequate margin as if profit were an inappropriate trait for a Māori firm (participant A2). In this case, the participant associated Māori management with unsustainable, small-scale enterprise; yet there were cases of highly successful and fast-growing firms of international standing that deeply embraced Māori ways of managing and relied strongly on family and on ties with the local Indigenous community (as in the case of a diversified tourism service provider).

Institutions established to assist Māori (with government support or as part of treaty settlement processes) did play a role in providing assistance to Māori entrepreneurs, but the role appeared to be supplementary, with the entrepreneurs primarily relying on their own resources. Some of the entrepreneurs adopted a rather critical attitude to such institutions, suggesting a split within the broader Māori community, with insiders perceived as attaining underserved benefits and not all Māori having fair access.

The scope of the entrepreneurs' activities and aspirations was not limited to the region, or to Aotearoa New Zealand. Most customers of the tourism operators came from overseas, and a Māori food producer wanted to expand to Australia. Overseas experience was often associated with acquiring skills and knowledge by, for example, working in California or travelling to the United States to inspect innovative equipment. The state of the global economy had immediate effects on most firms. The region was seen as a source of opportunity, and no business-related reasons for leaving were mentioned. Some of the entrepreneurs were not originally residents of the Bay of Plenty, migrating there because of the opportunities it offered.

Institutional environments

In Chile, the central concept in the institutional discourse around Mapuche entrepreneurs was ‘funds’. Relevant financial help was available from several ministries, including the Ministry of Social Development (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social), Ministry of Economics (Ministerio de Economía), Ministry of Agriculture (Ministerio de Agricultura), and Ministry of the Environment (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente). Furthermore, visits of officials to Indigenous areas were highlighted on government websites. Mapuche entrepreneurs were primarily mentioned in central government documents, all of which were in Spanish, with little use of Mapudungun words.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the central concept in the institutional discourse around Māori entrepreneurs was ‘strategy’. Strategies for promoting Māori enterprises were formulated at multiple levels, from international (e.g., in negotiating trade agreements) (Mika, Reference Mika2021b) to sub-regional (e.g., for Rotorua, a district of the Bay of Plenty region) (Rotorua District Council, 2012b). Strategies at all levels were consistent in language and content. Furthermore, unlike in Chile, official documents frequently used Indigenous concepts (given without translation), even though all documents were in English. Occasionally, aspects of strategy were formulated in terms of Māori cultural concepts, thus, comprehensible only for someone familiar with the Māori language, an official language of Aotearoa New Zealand (Higgins, Rewi, & Olsen-Reeder, Reference Higgins, Rewi and Olsen-Reeder2014).

Comparing the two Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems

Compared to Mapuche entrepreneurs, Māori entrepreneurs employed a variety of business models. Mapuche entrepreneurs tended to follow more limited patterns; for example, craft-based enterprises, enterprises catering to tourists, and agricultural production. Māori enterprises differed in several ways. One Māori enterprise, which catered for super-rich ‘luxury’ tourists, relied primarily on the infrastructure it owned, whereas another enterprise organised unique experiences by combining resources it did not own (travel packages). Another Māori enterprise offered accommodation to tourists, but also to long-term local residents. A Māori food producer relied on the franchising model of a well-known international company operating in Aotearoa New Zealand, and a jade carving business relied primarily on selling artefacts it produced on-site.

Mapuche entrepreneurs anticipated relatively modest economic gains. Māori entrepreneurs demonstrated a greater variety of business goals and definitions of success, ranging from creating and selling a brand (thus, potentially achieving considerable economic gain) to perpetuating a craft, with economic considerations secondary. Unlike Mapuche entrepreneurs, some of the Māori entrepreneurs were active in more than one industry, and their focus shifted, following their personal interests and goals.

Mapuche entrepreneurs' contribution to their communities was seen by participants primarily in economic terms. In contrast, some of the Māori entrepreneurs explicitly focused on sustaining culture or passing culture to young Māori or on providing a work environment that is fulfilling for workers.

Family and culture were important for both Mapuche and Māori entrepreneurs. The difference was, however, in their reasoning. For Mapuche entrepreneurs, relying on family and culture appeared to be essential. Māori entrepreneurs appeared to have a choice, as economic success with little reliance on family and culture appeared possible. For instance, a successful tourism services entrepreneur mentioned that she is learning the Māori language, which appeared to be a consequence, rather than a prerequisite, of success.

Overall, Māori entrepreneurs exhibited greater variety in terms of both what they valued and the means they were able to deploy to achieve it. Māori entrepreneurs appeared indifferent to government support, largely attributing their success to their own efforts. Mapuche entrepreneurs were, however, more concerned about the prospect of government support.

Discussion

An evolutionary perspective

Indigenous people have inhabited the Araucanía and the Bay of Plenty regions for a long time (Bremner, Reference Bremner2013; De la Maza, Reference De la Maza2016), yet, their Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems are embedded in the prevailing political and economic contexts of the two countries – Chile and Aotearoa New Zealand. Of the two, Aotearoa New Zealand exhibits a more developed economy and a more stable political system (World Bank, 2019). Even though both Indigenous cultures differ in detail (Bremner, Reference Bremner2013; De la Maza, Reference De la Maza2016), family links and collaborative relationships were similarly valued (Mika, Cordier, Roskruge, Tunui, O'Hare, & Vunibola, Reference Mika, Cordier, Roskruge, Tunui, O'Hare and Vunibola2021). We suspect the differences between Mapuche and Māori entrepreneurial ecosystems are primarily attributable to differences in institutional contexts. Thus, as Chile and the Araucanía region develop, we anticipate that their Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem will evolve to resemble the Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem of the Bay of Plenty. This is the basis for an evolutionary perspective. We interpret the Mapuche entrepreneurial ecosystem as corresponding to an early stage of development, and we interpret the Māori entrepreneurial ecosystem as corresponding to an advanced stage of development.

An early stage Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem is characterised by Indigenous entrepreneurs who are highly embedded in their region and in their Indigenous culture. Relatively few business models are available (e.g., commercialisation of cultural heritage, landmarks, and crafts in local and regional markets) and they rely on the Indigenous culture or the region being part of the product (Croce, Reference Croce2017). Indigenous entrepreneurs operate at close to subsistence (Bruton, Ahlstrom, & Si, Reference Bruton, Ahlstrom and Si2015), with family closely involved. The main goal is sustenance for the entrepreneur and their immediate family. Maintaining Indigenous culture is not a goal by itself, but because culture is an essential part of the product, the entrepreneurs' activities help preserve Indigenous culture. Government support can be essential, although many entrepreneurs operate informally, which may preclude access to such support. Even though government support is available, it remains episodic, and Indigenous entrepreneurship is poorly represented in mainstream economic and policy discourse (Di Giminiani, Reference Di Giminiani2018).

In comparison, an advanced Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem differs primarily in the choices available to entrepreneurs. Creating viable enterprises that are deeply embedded in the Indigenous culture (e.g., crafts-based) or in the region (e.g., Indigenous tourism) are still possible, but Indigenous entrepreneurs can operate beyond their regional and international boarders, and can draw upon approaches to management unrelated to Indigenous culture. A broader range of business models – digital, franchise, and hybrid models (Colbourne, Reference Colbourne, Corbett and Katz2018; Croce, Reference Croce2017; Taiuru, Reference Taiuru2016) for instance – available to Indigenous entrepreneurs is in part attributable to better access to education, and, even more so, by working outside their region or internationally. There is also much variation in how family is involved in the enterprises, both as a resource and as a beneficiary. As to the maintenance of Indigenous culture, it is possible to set up successful enterprises that operate with the maintenance of culture, rather than economic gain, as the main goal (Haar & Delaney, Reference Haar and Delaney2009). At the same time, Indigenous entrepreneurs can create successful enterprises that do not involve culture as part of the product, with their activities contributing little to maintaining obvious forms of Indigenous culture, associated with the concept of Māori in business, where the entrepreneur identifies as Māori but the business does not (Mika, Fahey, & Bensemann, Reference Mika, Fahey and Bensemann2019a). A broad range of definitions of success are viable, which may include maintaining Indigenous culture, attaining benefits for the entrepreneurs' extended family, pursuing a preferred lifestyle or realising financial gains from, for example, selling their enterprise. The support of Indigenous entrepreneurship forms an essential part of mainstream policy and economic discourse, creating a supportive environment whose enabling effects are not necessarily visible to Indigenous entrepreneurs.

Theoretical contribution

The theoretical contribution is that the evolution of Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems is influenced by an internal imperative of cultural continuity (survival of Indigenous people), the resilience of Indigenous culture to external influences (primarily colonisation), and the state of mainstream social, economic, and political development indicated by human and other development measures within the countries and regions in which Indigenous enterprises exist. The transition from an early stage to an advanced stage of Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem development is likely to be driven primarily by the development of economic and political contexts. We found little evidence of Mapuche entrepreneurs having sufficient power or resources to influence the extent to which the external world is open to them or the availability of capital and knowledge needed to pursue a broader range of business models. There was, however, evidence of the Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem in the Araucanía region acquiring features similar to the Māori entrepreneurial ecosystem in the Bay of Plenty, through the emergence of international connections or another enterprise based on an idea from outside the region. At the same time, some of the Māori enterprises were similar to Mapuche enterprises (e.g., Indigenous culture as a tourism product, in combination with high family participation). Thus, the available evidence is consistent with gradual evolution from an early stage to an advanced stage Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem, the importance of which relates to the ecosystem's capacity to advance aspirations for Indigenous self-determination and sustainable development (Mika, Warren, Foley, & Palmer, Reference Mika, Warren, Foley and Palmer2017).

Policy implications

Policy makers in developing countries, with less developed Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems, should ensure that the benefits of economic and political development are available to Indigenous entrepreneurs as early as practicable. Such benefits are not limited to direct financial help. Rather, opportunities to gain experience by working outside the region or even overseas and to build networks may be more important.

Policy makers may see preserving Indigenous culture as a benefit in its own right, related to preserving the country's identity and to long-term social and economic opportunities at regional levels (Price, Shutt, & Sellick, Reference Price, Shutt and Sellick2018; Rundel, Salemink, & Strijker, Reference Rundel, Salemink and Strijker2020). As Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems evolve, preservation of Indigenous culture through entrepreneurship cannot be assumed as a broader range of business models and opportunities become available. To ensure the maintenance of Indigenous culture, direct and targeted government interventions may be necessary. Thus, policy makers should provide incentives for both preserving and competently managing cultural capital and protecting Indigenous rights in their cultural and intellectual property (Ahu, Whetu, & Whetu, Reference Ahu, Whetu and Whetu2017; Whare & Skinner, Reference Whare and Skinner2021).

Limitations and further research

The present study relied on evidence derived from comparison and could be extended by considering historical evidence or longitudinal studies of Indigenous entrepreneurship. Furthermore, action research trialling interventions, like support for a broader range of business models to improve the viability of Indigenous enterprises in Latin America, is highly desirable. In future research, effort could be given to engaging former entrepreneurs or entrepreneurs whose enterprises are of varying scales and financial stability to ascertain the predicative factors and consequences of various interventions and institutional elements which comprise Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Conclusion

This paper contributes to Indigenous entrepreneurship knowledge by revealing the dynamics and characteristics of Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems. We argue that the evolution from an early to an advanced stage of Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem development is driven by the social, economic, and political contexts in which the ecosystems are embedded. In early stage Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems, entrepreneurs are strongly embedded in their regions, Indigenous culture is relied on as a resource, and relatively few business models are employed. In contrast, in advanced Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems, entrepreneurs are embedded to varying degrees, and have choices of business model and opportunities that are independent of the region or their Indigenous culture. While belonging to an advanced Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem offers advantages to Indigenous entrepreneurs, it does not necessarily result in a stronger Indigenous culture.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Rosa Caniumil and the team from Universidad Autónoma de Chile in Temuco for their collaboration in the data collection and access to Mapuche small-scale entrepreneurs in southern Chile. We also thank Mrs. Vonese Walker from Poutama Trust who arranged interviews with Māori entrepreneurs in Rotorua, Bay of Plenty. We thank Massey University for a research grant, which assisted with New Zealand data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.