Introduction

During the past decades, widely adopted corporate entrepreneurial activities have enabled firms to transform and upgrade themselves in various economies (Calabro, Santulli, Torchia, & Gallucci, Reference Calabro, Santulli, Torchia and Gallucci2021; Prugl & Spitzley, Reference Prugl and Spitzley2021). However, variability and change, which present a degree of uncertainty, occur in the process of firms' entrepreneurship (Fang, Memili, Chrisman, & Tang, Reference Fang, Memili, Chrisman and Tang2021; Heavey, Simsek, Roche, & Kelly, Reference Heavey, Simsek, Roche and Kelly2009), resulting in firms' hesitation to pursue entrepreneurship. Accordingly, transforming these hurdles into incremental steps that drive corporate entrepreneurship becomes vital. We contend that long-term orientation is vital for corporate entrepreneurship. A long-term orientation represents an approach oriented around future rewards (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, Reference Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov2010). Practically, a long-term orientation can alleviate uncertainties during the entrepreneurial process because entrepreneursFootnote 1 are required to spend substantial amounts of time orchestrating various kinds of resources to reduce these ‘unknowns’ in the process of corporate entrepreneurship (Lévesque & Stephan, Reference Lévesque and Stephan2020; Nadkarni, Chen, & Chen, Reference Nadkarni, Chen and Chen2016), and a long period of time is needed to determine the outcome of any entrepreneurial project. In addition, an entrepreneur is considered to be a critical factor in corporate entrepreneurship because he or she plays the role of a ‘cheerleader’ and persistently overcomes the obstacles and risks relevant to the outcome of a venture (Morris, Avila, & Allen, Reference Morris, Avila and Allen1993). In particular, they mostly play the role of change agents in small and medium-sized private enterprises (He, Reference He2008; Zhao & Lu, Reference Zhao and Lu2016). Thus, the value that entrepreneurs place on time likely impacts the effectiveness of a firm's long-term orientation on corporate entrepreneurship.

Previous research has yielded rich insights into the effects of cultural differences on entrepreneurial activities (Lortie, Barreto, & Cox, Reference Lortie, Barreto and Cox2019; Tang, Yang, Ye, & Khan, Reference Tang, Yang, Ye and Khan2021); however, the temporal horizon has not been sufficiently explored in corporate entrepreneurship (Lévesque & Stephan, Reference Lévesque and Stephan2020), excepting Tehseen, Deng, Wu, and Gao (Reference Tehseen, Deng, Wu and Gao2021), who analyzed the impact of a firm's long-term orientation on entrepreneurial innovativeness, if not precisely on corporate entrepreneurship. In addition, our understanding of what conditions under which a long-term orientation benefits corporate entrepreneurship is still limited. The existing research has mainly been concerned with explaining corporate entrepreneurship by integrating the characteristics of firms and their organizational environments (Chen & Nadkarni, Reference Chen and Nadkarni2017), however, micro-foundation factors influencing corporate entrepreneurship remain understudied (Cabral, Francis, & Kumar, Reference Cabral, Francis and Kumar2021; Soleimanof, Singh, & Holt, Reference Soleimanof, Singh and Holt2019), despite emerging research attempting to offer insights regarding the micro-foundation of corporate entrepreneurship (Seiger & Kotlar, Reference Seiger and Kotlar2019; Soleimanof, Singh, & Holt, Reference Soleimanof, Singh and Holt2019). To fill these gaps, we aim to extend research on temporal orientation and corporate entrepreneurship. By adopting stewardship theory, we plan to uncover the boundary conditions at the individual level, specifically the impact of entrepreneurs' prior experience on the long-term orientation-corporate entrepreneurship nexus. Firms with a long-term orientation generally prefer cultivating capable steward employees over the long term while searching for opportunities for future corporate entrepreneurship (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). Meanwhile, an entrepreneur's prior experience acts as pre-employment consideration, highlighting the extent to which entrepreneurs act as stewards (Corbett, Covin, O'Connor, & Tucci, Reference Corbett, Covin, O'Connor and Tucci2013). Thus, an entrepreneur's prior experience may act as a catalyst that conditions the relationship between a long-term orientation and corporate entrepreneurship. We strive to explore the combination of these two to deepen our understanding of corporate entrepreneurship.

We use stewardship theory in this study because it can conceptually explain the relationship between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship via two mechanisms: (cultivating) people and (probing) opportunities (Miller, Le Breton-Miller, & Scholnick, Reference Miller, Le Breton-Miller and Scholnick2008; Shane, Reference Shane2003). Stewardship theory states that steward firms are likely to establish a sustainable relationship with their employees (Miller, Le Breton-Miller, & Scholnick, Reference Miller, Le Breton-Miller and Scholnick2008) and prefer to persistently explore opportunities to assiduously manage organizational resources and investments (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). In addition, stewardship theory allows us to determine the moderating roles of entrepreneurs' prior experience (i.e., government working experience, military experience, and overseas experience) (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997), which shows firms' steward tendencies. We test our hypotheses using data from a large-scale survey of private small and medium-sized firms in China, which produced 7,306 usable data points. Our results strongly support our hypotheses about the different contingency effects.

This paper contributes to the literature in three ways. First, we extend the research on the temporal perspective in corporate entrepreneurship by directly examining the effects of long-term orientation on corporate entrepreneurship. Second, this study adds to the research on the boundary conditions at the individual level by regarding entrepreneurs' prior experience as a moderator for the relationship between long-term orientation and corporate entrepreneurship. Third, we contribute to the stewardship theory by incorporating pre-employment considerations (Chrisman, Reference Chrisman2019), manifested in an entrepreneur's prior experience. We examine the various congruence of steward tendencies between entrepreneurs and their firms to strengthen the realism and relevance of stewardship theory in the research area of corporate entrepreneurship.

Theory and hypotheses

Stewardship theory

Stewardship theory is rooted in psychology and sociology. The model of humanity, which is characterized as the ‘self-actualizing man’ by Argryis (Reference Argryis1973), was essentially the origin of stewardship theory. Stewardship theory, in contrast to agency theory, began to emerge as an alternative framework for analyzing and understanding the motivations of managers in firms in early 1990 (Menyah, Reference Menyah, Idowu, Capaldi, Zu and Gupta2013). According to stewardship theory, the model of humanity is based on a steward whose behaviors are pro-organizational and collectivistic (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997), and who acts in the best interest of the firm. Stewardship theory challenges the opportunism assumption and the effectiveness of control governance behaviors that agency theory assumes (Soleimanof, Singh, & Holt, Reference Soleimanof, Singh and Holt2019).

Davis, Schoorman, and Donaldson (Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997) delineated the assumptions of stewardship theory by comparing them with the assumptions of agency theory. The management philosophy of stewardship in a firm highlights involvement, and managers prefer to trust instead of employ control mechanisms. In addition, stewardship theory management operates with a long-term time frame, and its overall culture is manifested in collectivism with a low power distance. To extend this research, Miller, Le Breton-Miller, and Scholnick (Reference Miller, Le Breton-Miller and Scholnick2008) elucidated three additional assumptions of stewardship in the context of family firms, namely, longevity, community, and connection. That is, firms with stewardship prefer to re-establish a sustainable relationship with their employees and/or customers. In addition, stewardship manifests the assiduous management of organizational resources and investments (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997), leading firms to persistently explore developmental opportunities.

An emerging stream of recent research argues that stewardship theory lacks realism and relevance because its existing assumptions cannot realistically assess the multiple, heterogeneous, and complex phenomena of firms (Chrisman, Reference Chrisman2019). Scholars have called for a more realistic and relevant set of assumptions for analyzing firms' stewardship-oriented activities (Madison, Holt, Kellermanns, & Ranft, Reference Madison, Holt, Kellermanns and Ranft2016; Zheng, Shen, Zhong, & Lu, Reference Zheng, Shen, Zhong and Lu2020). For instance, CEOs are not purely altruistic in pursuit of pro-organizational behaviors (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997; Ghoshal, Reference Ghoshal2005); rather, they possess various steward tendencies. Chrisman (Reference Chrisman2019) suggested that pre-employment considerations could be incorporated into the assumptions of stewardship theory to address the problems of bounded rationality and information asymmetry. Therefore, understanding how to improve the realism of stewardship theory through a consideration of relevant boundary conditions is critical, yet it has been omitted.

Corporate entrepreneurship

Corporate entrepreneurship has been defined as ‘extending the firm's domain of competence and corresponding opportunity set through internally generated new resource combinations’ (Burgelman, Reference Burgelman1984: 154). In the beginning, corporate entrepreneurship was regarded as intrapreneurship that employed internally generated innovations from internal employees. This definition became popular in the strategic management academic community throughout the 1980s and early 1990s (Ginsberg & Hay, Reference Ginsberg and Hay1994; Hornsby, Naffziger, Kuratko, & Montagno, Reference Hornsby, Naffziger, Kuratko and Montagno1993; Kanter, Ingol, Morgan, & Seggerman, Reference Kanter, Ingol, Morgan and Seggerman1987; Morris, Avila, & Allen, Reference Morris, Avila and Allen1993; Morris, Davis, & Ewing, Reference Morris, Davis and Ewing1988). Afterward, the scholarly community gradually recognized that subcontracting and franchising to small companies can be an alternative method of pursuing corporate entrepreneurship, making large and aged organizations young and viable (Lengnick-Hall, Reference Lengnick-Hall1991). Joint ventures and acquisitions toward the process of corporate entrepreneurship involve external links (Lengnick-Hall, Reference Lengnick-Hall1991). These actions categorized corporate entrepreneurship into intrapreneurship and exopreneurship. This paper adopts this point of view and regards corporate entrepreneurship as containing both intrapreneurship and exopreneurship.

Since the first publication on corporate entrepreneurship in the late 1960s (Westfall, Reference Westfall1969), numerous studies have demonstrated that corporate entrepreneurship is pervasive and instrumental in creating sustainable competitive advantages (Kuratko & Audretsch, Reference Kuratko and Audretsch2013). This kind of initiative leads firms to transform and evolve to meet emerging challenges in a changing competitive landscape (Dai & Liu, Reference Dai and Liu2015). The existing research has been more concerned with determining how factors such as a task environment, a firm strategy and structure, or its external and internal resources affect corporate entrepreneurship (Chen & Nadkarni, Reference Chen and Nadkarni2017; Zahra, Randerson, & Fayolle, Reference Zahra, Randerson and Fayolle2013). However, less attention has been given to the micro-foundation of corporate entrepreneurship (Zahra & Wright, Reference Zahra and Wright2011). The existing research has seldom shed light on the highly innovative individuals, who are the most active element for instigating corporate entrepreneurship (Chen & Nadkarni, Reference Chen and Nadkarni2017). Over the last decade, the focus of the corporate entrepreneurship research has shifted to the roles that individuals within incumbent firms (such as top management team (TMT) members) play in promoting corporate entrepreneurship (e.g., Yuan, Bao, & Olson (Reference Yuan, Bao and Olson2017); Chen and Nadkarni (Reference Chen and Nadkarni2017)), but the intimate link between leading individuals and entrepreneurial firms remains underexplored.

Moreover, companies often resort to reducing costs, for example, reducing the number of employees, moving physical sites to low-cost areas, and reducing input on R&D as ways to react to their obstacles; in comparison, engaging in corporate entrepreneurship can have long-term effects on companies (Amit, Reference Amit1986; Baack & David, Reference Baack and David2008). However, the temporally related antecedents of entrepreneurship have been neglected (Lévesque & Stephan, Reference Lévesque and Stephan2020). Although a strand of emerging research has gradually emphasized the impact of long-term orientation on entrepreneurship (Eddleston, Kellermanns, & Zellweger, Reference Eddleston, Kellermanns and Zellweger2012; Lumpkin & Brigham, Reference Lumpkin and Brigham2011; Sharma, Salvato, & Reay, Reference Sharma, Salvato and Reay2013), just when and how long-term orientation affects firms' corporate entrepreneurship merits further attention, especially in small and medium-sized enterprises.

Long-term orientation and corporate entrepreneurship

A long-term orientation is regarded as a dimension of cultural value (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2005) that attaches more importance to the future than to the present (Lumpkin & Brigham, Reference Lumpkin and Brigham2011). Long-term orientation is defined as a mindset that features patience and long-term investment (e.g., Miller and Le Breton-Miller (Reference Miller and Le Breton-Miller2011); Zahra, Hayton, and Salvato (Reference Zahra, Hayton and Salvato2004); Eddleston, Kellermanns, and Zellweger (Reference Eddleston, Kellermanns and Zellweger2012)). Stewardship theory entails ‘an attitude born of a firm's desire to keep the business healthy for the long run and to treat employees and customers with that in mind’ (Miller, Le Breton-Miller, & Scholnick, Reference Miller, Le Breton-Miller and Scholnick2008). Exploring the stewardship theory, Miller, Le Breton-Miller, and Scholnick (Reference Miller, Le Breton-Miller and Scholnick2008) stressed the importance of longevity and talented workforces. Furthermore, Zellweger (Reference Zellweger2007) suggested that long-term orientation allows firms to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities. Thus, long-term orientation reflects the values espoused by the stewardship theory. Accordingly, long-term orientation can be regarded as one of the key components of stewardship theory (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997; Eddleston, Kellermanns, & Zellweger, Reference Eddleston, Kellermanns and Zellweger2012). We propose that a firm's long-term orientation is likely to have an impact on its corporate entrepreneurship for two reasons, namely, the cultivation of people and the probing of opportunities, which has also been addressed by Shane (Reference Shane2003) and Casson (Reference Casson2005).

On the one hand, long-term-oriented enterprises are more likely to focus on long-term gains than on their short-term profits (McCann, Leon-Guerrero, & Haley, Reference McCann, Leon-Guerrero and Haley2001). This focus leads firms to pay more attention to the construction of strategic resources (i.e., R&D capability, patents, human capital, etc.) that have important implications for future development (Zahra, Hayton, & Salvato, Reference Zahra, Hayton and Salvato2004). Among these key strategic resources, human resources are often regarded as the most active element of an enterprise (Brigham, Lumpkin, Payne, & Zachary, Reference Brigham, Lumpkin, Payne and Zachary2014). Therefore, enterprises that maintain a long-term orientation tend to invest heavily in human capital (Arregle, Hitt, Sirmon, & Very, Reference Arregle, Hitt, Sirmon and Very2010) and pay particular attention to constructing an internal environment that is favorable to potential talent (Eddleston, Kellermanns, & Zellweger, Reference Eddleston, Kellermanns and Zellweger2012), which eventually leads to the formation of a ‘pool’ of potential entrepreneurs who can leverage future opportunities. For example, the Chinese hotpot restaurant, Haidilao, treats its employers as future investments by paying above-average wages, subsidizing housing allowances, and developing a long-term family-oriented culture (Lin, Shi, Prescott, & Yang, Reference Lin, Shi, Prescott and Yang2018). As Engelen, Weinekotter, Saeed, and Enke (Reference Engelen, Weinekotter, Saeed and Enke2018) suggest, such future investments in employees can foster the type of talent who can engage in innovative and entrepreneurial activities. In particular, capable steward employees will be inclined to seek employment at firms with steward cultures that offer fair opportunities for self-actualization. As a result, such kinds of firms' employees are more self-actualized, pro-organizational and collectivistic. These factors can facilitate information exchange and cooperation, thereby facilitating the development of entrepreneurial activities.

On the other hand, as argued by Lumpkin, Brigham, and Moss (Reference Lumpkin, Brigham and Moss2010), long-term-oriented enterprises tend to prioritize decisions and actions that take time to mature and have a long-term impact and value. Accordingly, a long-term-oriented enterprise has a higher tolerance for uncertainty and is more willing to engage in innovation and risk-taking. Kuratko, Ireland, Covin, and Hornsby (Reference Kuratko, Ireland, Covin and Hornsby2005) proposed that corporate entrepreneurship allows firms to fully exploit their current competitive advantages and to explore future opportunities that may be highly uncertain. Hence, a long-term-oriented firm is more likely to pursue entrepreneurship by exploiting ‘tomorrow's opportunities,’ which can be rather volatile. In contrast, firms with a more dominant short-term orientation tend to reject entrepreneurial opportunities that mature over the long term or are highly uncertain. Long-term oriented firms accept, capture and exploit these opportunities. Thus, long-term oriented firms have a broader ‘opportunity set’ and pursue more entrepreneurial opportunities (Zellweger, Reference Zellweger2007). Since the essence of entrepreneurship is to identify and exploit opportunities, long-term-oriented firms are more likely to engage in corporate entrepreneurial activities than their short-term-oriented peer competitors.

Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: A long-term orientation is positively related to corporate entrepreneurship.

Moderating role of entrepreneurs' prior experience

According to stewardship theory, stewards aim to fulfill organizational goals and objectives instead of satisfying their individual self-interests (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). The congruence of goals, namely being a steward vs. be a stewardship organization, between entrepreneurs and organizations can thus encourage firms to engage in innovative and proactive actions in a high-trust environment (Corbetta & Salvato, Reference Corbetta and Salvato2004) because the trust derived from a stewardship culture helps to manage uncertainty by encouraging experimentation and an active reflection on experimental results (Chung & Gibbons, Reference Chung and Gibbons1997). However, practically, firms commonly have multiple, heterogeneous, and complex cultures; thus, no pure stewardship culture can exist in a firm (Chrisman, Reference Chrisman2019). Given that entrepreneurship behavior is typically implemented in the context of uncertainty, the classic agency problem is difficult to avoid (Chung & Gibbons, Reference Chung and Gibbons1997). Therefore, the role of agency-related factors must be considered in stewardship governance, which can also improve the practicality and relevance of the application of stewardship theory.

Prior experience is a critical factor influencing entrepreneurs' current behavior. Most research has regarded entrepreneurs' prior experience as an individual factor (e.g., Paik (Reference Paik2014), Kollmann, Stöckmann, and Kensbock (Reference Kollmann, Stöckmann and Kensbock2019), Shi and Weber (Reference Shi and Weber2021)). To date, extant research has identified several mechanisms by which entrepreneurs' prior experience may influence corporate entrepreneurship. These ideas help us postulate the moderating effects of the different kinds of entrepreneurs' prior experience on the association between firms' long-term orientation and corporate entrepreneurship. Specifically, entrepreneurial learning is regarded as the primary driving mechanism. By learning from experience, entrepreneurs are more capable of recognizing opportunities and managing teams efficiently (Paik, Reference Paik2014). In particular, past overseas experience and international knowledge access impact entrepreneurs via experiential learning and vicarious learning (Liu, Wright, & Filatotchev, Reference Liu, Wright and Filatotchev2015). In other words, prior entrepreneurial experience serves as a valuable ‘source of learning’, which can lead to an advantage in learning and coping for experienced entrepreneurs (2019). In addition, social capital is another important mechanism. Paik (Reference Paik2014) proposed that prior firm- founding experience helps entrepreneurs increase their social capital by establishing social connections. Wahba and Zenou (Reference Wahba and Zenou2012) argued that overseas experience probably results in a loss of social capital back in the home country. Furthermore, Kollmann, Stöckmann, and Kensbock (Reference Kollmann, Stöckmann and Kensbock2019) regarded role identity as an alternative mechanism to explain how prior entrepreneurial experience influences entrepreneurs. Consistently, Zhan, Uy, and Hong (Reference Zhan, Uy and Hong2020) adopted role identity logic to elaborate on the impact of prior entrepreneurial experience on entrepreneurship by drawing on a person-by-situation perspective. In addition, other scholars propose that prior experience probably influences entrepreneurship through accumulating financial assets (Wahba & Zenou, Reference Wahba and Zenou2012) or strengthening entrepreneurs' early aspiration (Shi & Weber, Reference Shi and Weber2021).

Inspired by these mechanism, we identified three kinds of entrepreneurs' prior experience (i.e., government experience, military experience, and overseas experience) to assess their implications for the relationship between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship. On the one hand, we assume that entrepreneurs' prior experience could influence the way that they treat their employees (e.g., training, promotion, and collaboration) and govern their firms. For example, prior government or military work experience can cause entrepreneurs to act more like stewards, thereby decreasing the risks of executive opportunism by maintaining stewardship governance for an extended period (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). On the other hand, we postulate that entrepreneurs' prior experiences may play a crucial role in identifying and gathering external intelligent resources and opportunities (Kotha & George, Reference Kotha and George2012). Current societies typically highlight social connections, and entrepreneurs often rely heavily on their own personal ties to access resources (Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000), discover talent and explore entrepreneurial opportunities. In this regard, entrepreneurs' career experiences, to some extent, represent the social network that they had constructed in the past, thus greatly influencing the extent to which they can secure external human resources and entrepreneurial opportunities (Hernández-Carrión & Camarero-Izquierdo, Reference Hernández-Carrión and Camarero-Izquierdo2017).

Moderating role of government work experience

A firm's long-term orientation can help to connect enterprising people and opportunities, thereby fostering the occurrence of entrepreneurial activities (Shane, Reference Shane2003; Shane & Venkataraman, Reference Shane and Venkataraman2000). Role identities are a key component of entrepreneurial cognition, which influences firms to engage in the expected behaviors of a specific role (Zhan, Uy, & Hong, Reference Zhan, Uy and Hong2020). Entrepreneurs who have government experience are taught to become servants for the country, especially in China. Accordingly, they are not inclined to engage in opportunistic behaviors because of their past training in a government or political party. Entrepreneurs with such work experience prefer stewardship governance, and they mostly adopt trust-to-control mechanisms, which are better for cultivating employees in the long run. As a result, entrepreneurs with prior government work experience are more likely to fit with the steward culture represented by a long-term orientation and to invest more in employees, thus improving corporate entrepreneurship.

In addition, entrepreneurs' work experience in government facilitates the formation of political ties that allow access to critical resources (Wang, Feng, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Wang, Feng, Liu and Zhang2011), thus helping to prob entrepreneurial opportunities. Similarly, Fan, Wong, and Zhang (Reference Fan, Wong and Zhang2014) claimed that if an entrepreneur's previous service in a government office could be advantageous for establishing political connections to facilitate the probing of more potential entrepreneurial opportunities. Particularly, in some developing countries, such as China, which is in the advanced stage of economic transformations and marketization reforms, the marketization of resources is still relatively low, and the government controls important economic resources. Hence, firms, SMEs in particular, usually have difficulties obtaining critical resources (i.e., talent or entrepreneurial opportunities) effectively and efficiently (Bai, Lu, & Tao, Reference Bai, Lu and Tao2010), which constrains corporate entrepreneurship. Assuming such circumstances, political connections, which could be obtained through previous government experience, become an important channel through which entrepreneurs can explore more entrepreneurial opportunities to support corporate entrepreneurship (Ferguson & Voth, Reference Ferguson and Voth2008). For instance, the political connections of entrepreneurs might be leveraged to facilitate their access to more bank loans (Charumilind, Kali, & Wiwattanakantang, Reference Charumilind, Kali and Wiwattanakantang2006; Firth, Lin, Liu, & Wong, Reference Firth, Lin, Liu and Wong2009; Khwaja & Mian, Reference Khwaja and Mian2005; Leuz & Oberholzer-Gee, Reference Leuz and Oberholzer-Gee2006), thus allowing them to broaden their search scopes to identify more opportunities.

Taken together, we argue that entrepreneurs' government work experience effectively enhances the positive relationship between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Entrepreneurs' prior government work experience can strengthen the positive relationship between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship.

Moderating role of military experience

By the same token, we focus on entrepreneurs' military experience, which makes entrepreneurs better stewards and thus helps attract more loyalty employees and more easily establish political connections more easily (Luo, Xiang, & Zhu, Reference Luo, Xiang and Zhu2017), thereby enhancing the link between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship. On the one hand, entrepreneurs with prior military experience often establish clear role identities for themselves. For example, they often tend to admire heroes and try to become like heroes, which distinctly influences their entrepreneurial behaviors. It is feasible that entrepreneurs with military experience tend to choose stewardship governance. Chinese executives who have been trained as military personnel greatly value loyalty and collectivism; thus, they tend to hire steward employees, and they work well with people who share similar cultural perspectives. As a result, their employee investments likely largely decrease enterprising employees' opportunistic behaviors, which ultimately benefits from higher levels of corporate entrepreneurship.

On the other hand, some scholars suggest that when an entrepreneur has a military service background, he or she is regarded as having some kind of political connection (Luo, Xiang, & Zhu, Reference Luo, Xiang and Zhu2017). Often, a government (e.g., the Chinese government) attaches great importance to the reemployment of retired military personnel through favorable policies and various types of concrete support. As such, entrepreneurs with military backgrounds may be prone to establishing closer connections with a government, which facilitates their capabilities to acquire favorable resources and explore entrepreneurial opportunities, thus leading to higher levels of corporate entrepreneurship. In addition, most societies highly value military personnel and place a large amount of trust in them (e.g., China), so entrepreneurs with military backgrounds are more likely to obtain the trust and support of organizations.

Accordingly, we argue that the military experience of entrepreneurs can effectively enhance the positive relationship between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship, thus we hypothesize the following:

H3: Entrepreneurs' military experience can strengthen the positive relationship between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship.

Moderating role of overseas experience

Because of rapid economic development, studying and working abroad are becoming commonplace in many developing countries. People in developing countries who have obtained degrees overseas or who have completed an internship in developed countries, typically return to their home countries. Such kind of experience likely influences their entrepreneurial activities. In contrast to the other two kinds of experience, we suggest that entrepreneurs' overseas experience (e.g., studying, working, or visiting abroad) weakens the positive relationship between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship in China.

Entrepreneurs with overseas experience have been embedded in the country where they studied or worked and then subsequently transitioned to become embedded in their home country (Liu, Wright, & Filatotchev, Reference Liu, Wright and Filatotchev2015). This causes these entrepreneurs to manifest a ‘role identify disadvantage’ in relation to other peer entrepreneurs. Due to their multilayered experiences in different countries, these entrepreneurs may find it challenging to identify a clear role identity for themselves, such as that of a steward or agent. This difficulty can then lead to obstacles in effectively cultivating their employees and managing their entrepreneurial businesses.

In addition, cultural differences induced by the overseas experience can also play a significant role in entrepreneurship. Hofstede (Reference Hofstede1980) has proposed that developed countries, such as the United States, Australia, and Great Britain, are more likely to favor an individualistic style, while developing countries – such as China, Thailand and Mexico – are more likely to favor a collectivistic style. Accordingly, entrepreneurs from developing countries become influenced by an individualistic culture to some extent when they study or work abroad in a developed country. An individualistic culture can motivate people to be self-interested and achieve personal goals, which may hinder them from contributing to collective actions in the event that their efforts are not recognized (Morris, Avila, & Allen, Reference Morris, Avila and Allen1993). Entrepreneurs who experience a culture that privileges individual freedom are less likely to act as stewards. That is, entrepreneurs with overseas experience who adopt individualism do not exercise as much stewardship as entrepreneurs without such experience. Accordingly, those entrepreneurs may not attract many steward employees because of the incongruent cultural values.

Additionally, another challenge faced by entrepreneurs with overseas experience is the potential loss of social capital in their home country. Entrepreneurs who work or study abroad for an extended period tend to spend more time and energy on the establishment of their overseas network, which may obstruct their ability to obtain domestic resources, such as social relations and political connections (Allen, Qian, & Qian, Reference Allen, Qian and Qian2005). Such social ties and connections are conducive to the acquisition of entrepreneurial resources that are currently indispensable in Chinese society. Therefore, entrepreneurs who work or study abroad cannot secure opportunities via political connections as effectively as entrepreneurs who have consistently remained in China. Besides, returnees may have adapted to foreign ways of doing business that are mainly based on explicit rules and policies. Hence, these returnees may struggle to build connections with important stakeholders, who prefer a more reserved style and thus fail to efficiently secure critical opportunities.

Accordingly, we expect that entrepreneurs with overseas experience may attenuate the association between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship in China. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Entrepreneurs' overseas experience can attenuate the positive relationship between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship.

We illustrate the above hypotheses in the following conceptual framework in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework.

Methods

Data

Our Data come from a secondary data survey, namely the Chinese Private Enterprise Survey, which was designed and conducted by the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, the United Front Work Department of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCCP), and the China Society of Private Economy Research at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The survey was conducted in 2014, and data was collected from 11,217 firms in 31 different provinces in ChinaFootnote 2. The respondents of the survey are entrepreneurs of these private enterprises because most private enterprises in this study are founder-controlled private enterprises, in which entrepreneurs actively instigate corporate entrepreneurshipFootnote 3. In addition, the data on long-term orientation and corporate entrepreneurship are at the firm level, while the data on entrepreneurs' prior experience is at the individual level. To ensure the representativeness of the sample firms, researchers generated a nationwide random sample using the multistage stratified sampling technique across all provinces and industries (Jia & Mayer, Reference Jia and Mayer2017).

This dataset is appropriate for this study. It provides relevant information on representative Chinese manufacturing firms. Additionally, the aim of the survey was not only to investigate the relationships among long-term orientations, entrepreneurs' prior experience, and corporate entrepreneurship but also to collect other relevant useful information and opinions from Chinese entrepreneurs to obtain the general situation of entrepreneurs in China. Hence, interviewer-induced biases are unlikely to be present. Accordingly, this dataset is appropriate for examining how entrepreneurs' prior experience shapes the relationship between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship. To estimate our models successfully, we removed those cases with missing values and outliers. Ultimately, we retained 7,306 observations in this study (Table 1).

Table 1. Profile of the samples (N = 7,306)

Measures

Dependent variables

Corporate entrepreneurship (Ce). Following Burgelman (Reference Burgelman1983), Titus, House, and Covin (Reference Titus, House and Covin2017), and Lyngsie and Foss (Reference Lyngsie and Foss2017), we measured corporate entrepreneurship (Ce) by calculating the amount that a focal firm invested in (1) upgrading operational technology, (2) expanding the production scale of an original product, and (3) engaging in mergers and acquisitions (M&As), divided by that firm's total revenues from the prior year. According to Zahra (Reference Zahra1996), although corporate entrepreneurship consists of three dimensions, namely innovation, corporate venturing, and strategic renewal, researchers could focus their attention on innovation and corporate venturing activities in operationalizing corporate entrepreneurship. This is because strategic renewal usually concides with the occurrence of innovation and corporate venturing. Following Burgelman,983)'s seminal work, internal corporate venturing can be demonstrated through investments in expanding the scale of production for existing products (Dai, Liao, Lin, & Dong, Reference Dai, Liao, Lin and Dong2022). For external corporate venturing, we followed Titus, House, and Covin (Reference Titus, House and Covin2017) and focused on equity-based forms of new business investment, specifically investments in mergers with other firms and acquisitions of existing external firms (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Liao, Lin and Dong2022). Additionally, upgrading operational technology is a key dimension of process innovation. As a result, we used the amount of investment in upgrading operational technology to represent innovation and used other two investments to gauge internal and external corporate venturing. By doing so, we were able to describe the efforts that a focal firm devoted to enhance their innovation, corporate venturing and strategic renewal, which in turn represent the essence of corporate entrepreneurship construct (Zahra, Reference Zahra1996).

Independent variables

Long-term orientation (Lto). According to Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Shi, Prescott and Yang2018), a focal firm's R&D expenditure and employee training can indicate the extent to which a firm is more concerned with long- than short-term performance/success and the extent to which a firm pays more attention to developing long-term relationships with stakeholders (i.e., employees). Hence, we measured a firm's long-term orientation by aggregating its expenditures in these two aspects and scaling the amount of the expenditures by the total revenues.

Moderating variables

Government work experience (gov). This variable denotes whether a focal entrepreneur had worked for government agencies or the CCCP prior to their employment at a firm. We thus used a dummy variable that indicates the entrepreneur's government work experience (1 = yes, and 0 = no).

Military experience (Me). To measure whether a focal entrepreneur had served in the military, we used a dummy variable, where 1 indicated that an entrepreneur had military experience and 0 indicated that they did not.

Overseas experience (Oe). We also used a dummy variable to represent a focal entrepreneur's overseas experience. If an entrepreneur had overseas experience (i.e., training, studying, or working), the variable was coded as 1; otherwise, it was coded as 0.

Controls

To rule out alternative explanations, we also included individual-, firm-, and industrial-level variables as controls. At the individual level, an entrepreneur's social class represents their social capital, which may influence their strategic decisions (Cao, Simsek, & Jansen, Reference Cao, Simsek and Jansen2015; De Clercq, Dimov, & Thongpapanl, Reference De Clercq, Dimov and Thongpapanl2013). We thus controlled for entrepreneurs' social classes by including a control variable (Soclss), which was measured by using a 10-point scale (1 = lowest, 10 = highest). An entrepreneur's educational level may also affect his or her decision making (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton2000). We thus controlled for an entrepreneur's educational level (Edu) by using a dummy variable, which indicates whether an entrepreneur has a university degree (1 = yes, and 0 = no).

At the firm level, firm age and firm size relate to a firm's strategic behaviors (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton2012); thus, we controlled for the number of years elapsed since a firm's founding. Additionally, we added the natural logarithm of the number of employees (LnEmploy) and the natural logarithm of assets (Lnassets) as controls. We included financial leverage (Lev) as a control as measured by the amount of a firm's bank loans, scaled by its sales revenues (Du, Reference Du2015). We also controlled for firm performance (ROE), as measured by the return on equity; OFDI (Frinvst), as measured by the ratio of outward foreign direct investment to revenues; and formal governance structure (Formalstc). Besides, family firms are better at implementing long-term orientation actions than the majority of their nonfamily counterparts because they have longer CEO tenures, facilitating both long-term independence and generational succession (Chirico, Welsh, Ireland, & Sieger, Reference Chirico, Welsh, Ireland and Sieger2021); thus, we controlled the family ownership ratio (Famown), which was measured by the ratio of equity owned by a family. To account for the heterogeneities originating from the institutional environment in which sample firms are embedded and from their industries, and we controlled for the regional level of marketization (Market) and for industries (ΣIndustry) in all the regression models.

Common method variance check

Common method variance (CMV) can be an issue when using survey data. First, rather than using perceptual measures, we asked respondents to report objective data, for example, the amount that a focal firm had invested in new business projects and whether or not a focal entrepreneur had worked for a government agency or the CCCP prior to their start date. Thus, we are less likely to suffer perceptual biases because perceptual measures are more inclined to arouse CMV (Spector, Reference Spector2006). Second, technologically, we conducted Harman's one-factor test using all the variables in the factor analysis. The most prominent factor accounts for 16 percent of the total variance. Thus, the first factor explained less than half of the total variance (16/52 = .308) explained by all the factors. Third, our significant interaction effect provides additional evidence to deflate CMV because studies that examine quadratic or interaction effects do not suffer from common method bias if their proposed quadratic or interaction effects are supported (Siemsen, Roth, & Oliveira, Reference Siemsen, Roth and Oliveira2010). Therefore, common method bias should not affect our results.

Results

Descriptive statistics and the results of the hypotheses tests

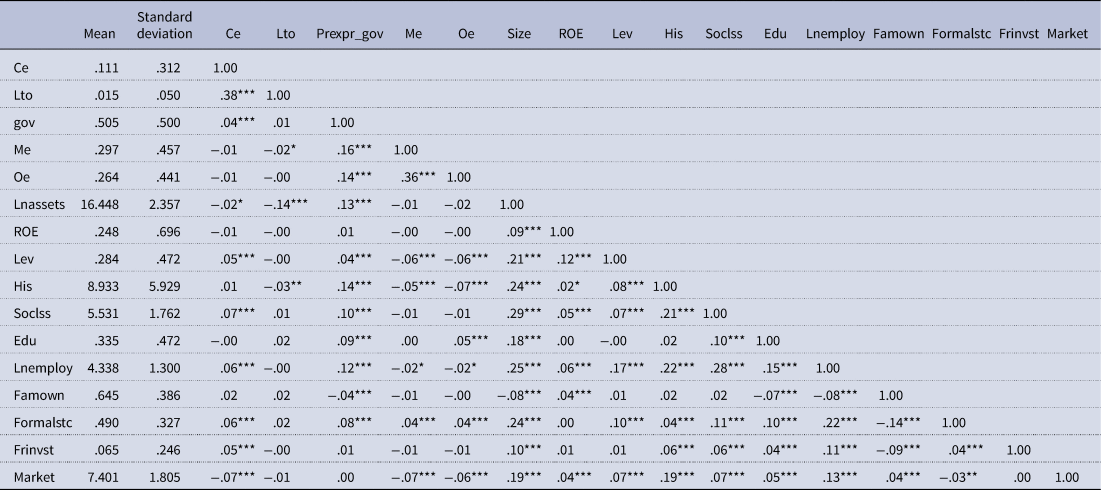

We used Stata 13.0 to estimate our regression models. Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics and presents the correlations of the key variables in the regression analyses, which were based on the raw data before standardization. To obtain combinations of a long-term orientation and prior experience, we standardized their scales before creating the product terms to alleviate the potential for multicollinearity. In addition, we assessed the variance inflation factor (VIF) score of each regression model and found that none of them exceeded 1.93; thus, the VIF scores were well below the ‘rule of thumb’ of 10 (Ryan, Reference Ryan1997). In particular, we detected a significant interaction effect (see Table 3); thus, multicollinearity was not a major concern because the detection of interaction effects overcomes the problem of increased correlations among predictor variables (Shieh, Reference Shieh2010). As shown in Table 2, a long-term orientation (Lto) was significantly related to corporate entrepreneurship (Ce). Additionally, financial leverage (Lev), entrepreneur social class (Soclss), firm size (Lnassets and Lnemploy), formal governance structure (Formalstc), firm OFDI (Frinvst), and regional marketization level (Market) were significantly related to corporate entrepreneurship (Ce).

Table 2. Summary and correlation analysis

Note: * p < .10, ** p < .05, *** p < .01.

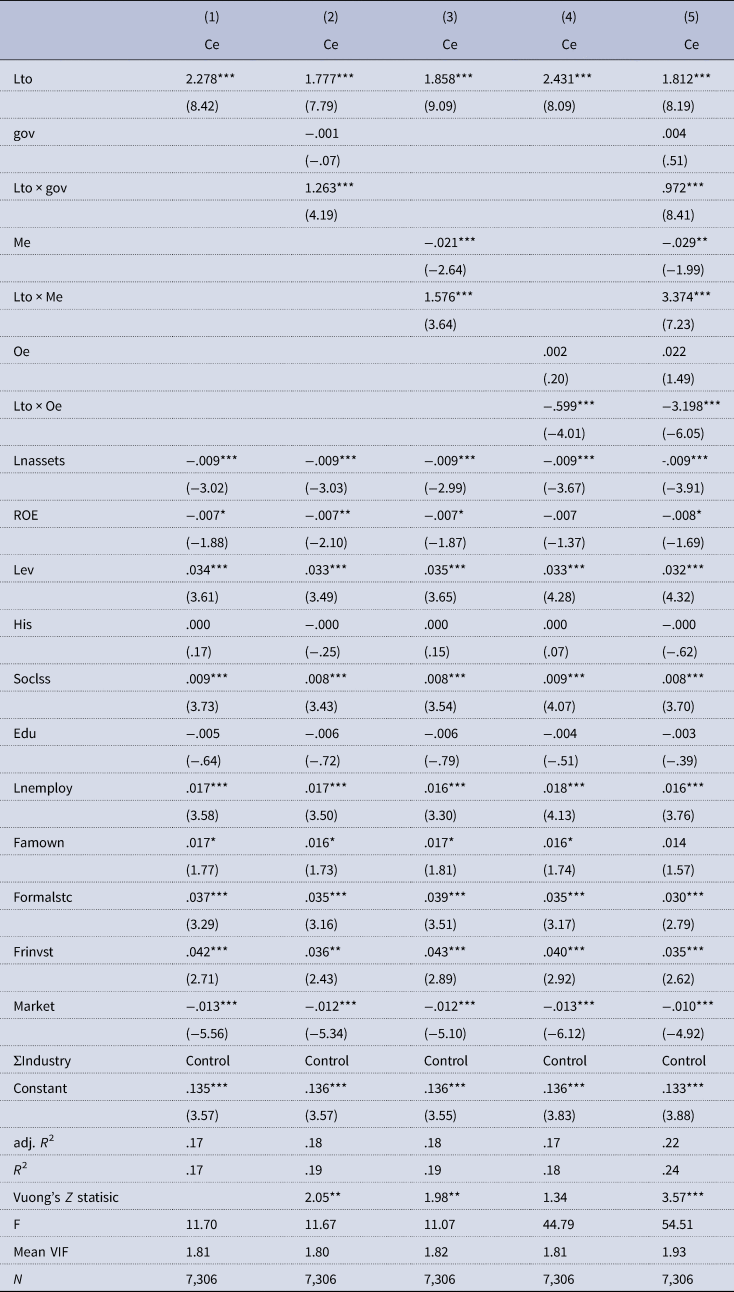

Table 3. Long-term orientation, prior experience and corporate entrepreneurship (Ce, OLS)

Note: t statistics in parentheses.

* p < .10, ** p < .05, *** p < .01.

Table 3 presents the results of the regression analyses. Model 1 in Table 3 includes the independent variable and the controls. Hypothesis 1 predicts that a long-term orientation is positively related to corporate entrepreneurial activities. As shown in Model 1 of Table 3, a ong-term orientation (Lto) had a positive and significant relationship with corporate entrepreneurship (Ce) (b = 2.278, p < .01). Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

Models 2 and 3 in Table 3 examine the moderating roles of government work experience and military experience, respectively. As shown in Models 2 and 3 in Table 3, the interactions between a firm's long-term orientation and government work experience (Lto × gov) (b = 1.263, p < .01) and the interactions between a firm's long-term orientation and military experience (Lto × Me) (b = 1.576, p < .01) were both positively and significantly related to corporate entrepreneurship (Ce). As shown in Figure 2, a long-term orientation contributed more to corporate entrepreneurship with higher levels of the entrepreneur's government work experience. Likewise, as shown in Figure 3, firms with entrepreneurs who had military experience were more likely to implement corporate entrepreneurship by establishing a long-term orientation. Vuong's Z statistic also shows that R 2 changes from the baseline model to the moderating models (i.e., Models 2 and 3) are all significant. Accordingly, both Hypotheses 2 and 3 are supported. Model 4 in Table 3 examines the moderating effect of overseas experience. The interaction between a firm's long-term orientation and overseas experience (Lto × Oe) (b = −.599, p < .01) was negatively and significantly related to corporate entrepreneurship (Ce). And the Vuong's Z statistic shows that R 2 changes from the baseline model to the Model 4 are significant. Thus, Hypothesis 4 is supported. We drew the interaction plot in Figure 4 to visually delineate their relationships.

Figure 2. Interaction between long-term orientation and government experience.

Figure 3. Interaction between long-term orientation and military experience.

Figure 4. Interaction between long-term orientation and overseas experience.

Notably, we found that an entrepreneur's military experience played a greater role than that of government's work experience in strengthening the positive association between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship (b1 = 3.374 > b2 = .972). In addition, although an entrepreneur's military experience negatively influenced corporate entrepreneurship (b = −.029, p < .05), its interaction with a long-term orientation could contribute (b = 3.374, p < .01). In addition, among the control variables, five firm-level variables – namely, firm size (Lnassets and Lnemploy), firm financial leverage (Lev), firm performance (ROE), firm OFDI (Frinvst), and formal structure (Formalstc) – as well as the individual-level variable of entrepreneurs' social class (Soclss) and the external factor of the regional level of marketization (Market) were all significantly related to corporate entrepreneurship (Ce). These results indicate that firms with a large number of employees are more likely to launch corporate entrepreneurial activities, while firms with abundant financial assets might hesitate to initiate corporate entrepreneurship. In addition, the results showed that the regional marketization level (Market) could hinder corporate entrepreneurship. These findings have implications for future corporate entrepreneurship research.

Robustness checks

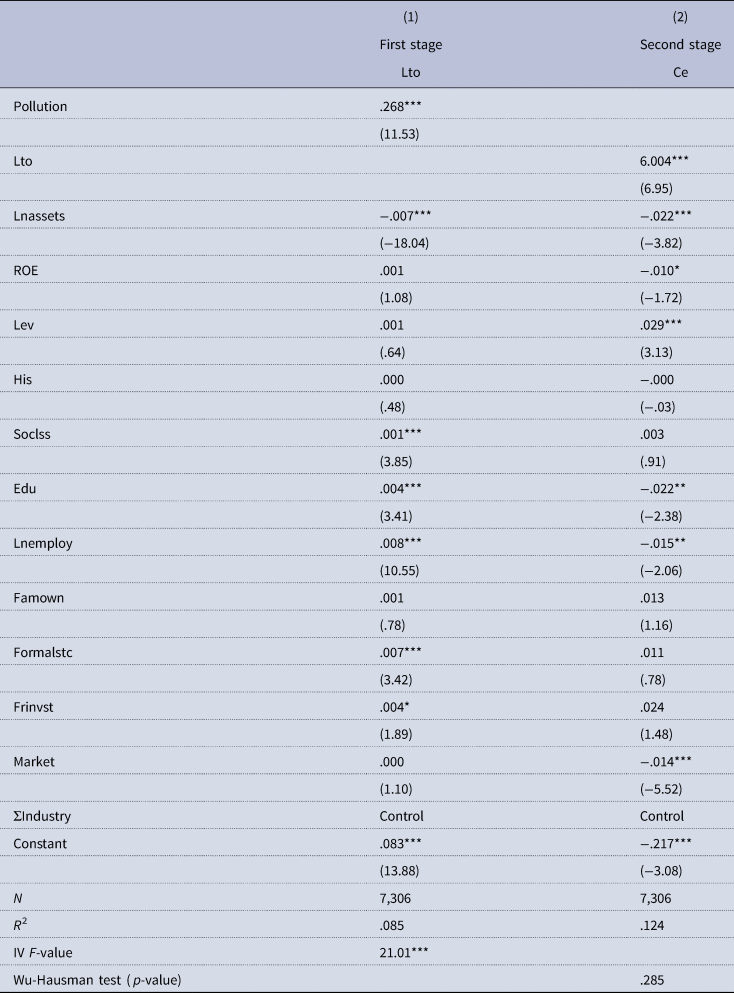

We adopted several approaches to assess the robustness of our findings. First, we adopted the instrumental variable and the two-stage least squares estimation (2SLS) to address endogeneity concerns. The ideal instrumental variable should influence on long-term orientation but be exogenous to corporate entrepreneurship. Using this principle, we included pollution input as an instrumental variable, measured as the ratio of pollution input to total revenue. The data came from the above-mentioned Chinese Private Enterprise Survey. Previous research suggests that long-term-oriented firms are more inclined to increase pollution input (Saether, Eide, & Bjørgum, Reference Saether, Eide and Bjørgum2021), and we thus argue that firms that input more on pollution tend to show a stronger long-term orientation. Therefore, pollution input may positively affect a firm's long-term orientation. However, pollution input is less likely to impact corporate entrepreneurship. Column 1 in Table 4 shows the first-state regression results, with long-term orientation applied as the dependent variable. The main variable of interest is the coefficient on the instrumental variable – pollution input, which is positive and significant (b = .268, p < .01), meaning that pollution input and the long-term orientation are highly correlated (IV F-value = 21.01, p < .01). Column 2 reports the result from the second-stage regressions, using corporate entrepreneurship as the dependent variable. The main variable of interest becomes replaced at this point by the long-term orientation taken from the first-stage regression. The coefficient estimates of this model are highly consistent with the baseline results (the Wu-Hausman test is nonsignificant, with a p-value >.1). Besides, these results provide evidence that long-term orientation facilitates corporate entrepreneurship even after controlling for the issue of endogeneity. Thus, the 2SLS results indicate that the results reported in Table 3 are robust.

Table 4. 2SLS Regression results

Note: t statistics in parentheses.

* p < .10, ** p < .05, *** p < .01.

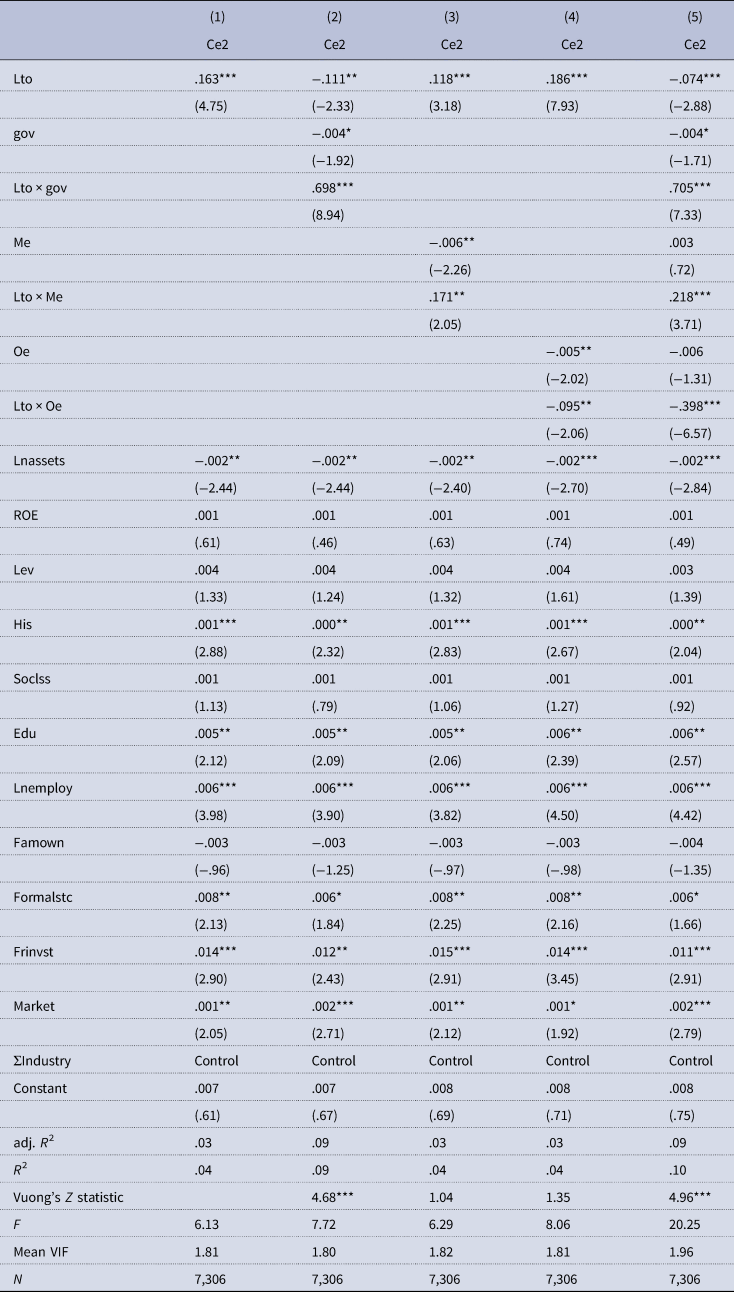

Second, we used one alternative measure of corporate entrepreneurship to check the robustness of the results (Dai, Liu, Liao, & Lin, Reference Dai, Liu, Liao and Lin2018). Specifically, we aggregated a focal firm's investments in new businesses, M&As, and incumbent entrepreneurial firms in 2014 to represent corporate entrepreneurial activities. The total revenues were then used to scale the total investments in 2014 to control for the influence of firm size. These two steps yielded an alternative new measure, which was labeled Ce2. As shown in Table 5, the OLS regression results remained the same as those in Table 3.

Table 5. Robustness check by an alternative dependent variable (Ce2, OLS)

Note: t statistics in parentheses.

* p < .10, ** p < .05, *** p < .01.

Third, we used another alternative measure of corporate entrepreneurship to recheck its robustness. We adopted a firm's reinvestment in 2014 as a measure of its corporate entrepreneurship, which was labeled Ce3. Table 6 shows that except for the nonsignificant interaction between long-term orientation and overseas experience, despite still negative, the other OLS regression results remained unchanged compared to the results of Table 3. Therefore, our findings are acceptably robust.

Table 6. Robustness check by an alternative dependent variable (Ce3, OLS)

Note: t statistics in parentheses.

* p < .10, ** p < .05, *** p < .01.

Discussion

This paper posits a theoretical argument and provides empirical evidence to support the notion that a temporal horizon plays a crucial role in entrepreneurship. In particular, we disclose how a long-term orientation is related to corporate entrepreneurship in SMEs from the perspective of stewardship theory. The present work also examines the moderating role of an entrepreneur's prior experience, which is an important individual factor and enriches the micro-foundation of entrepreneurship research. Specifically, we analyze how three types of entrepreneurs' prior experience – government, military or overseas experience – condition the long-term orientation–corporate entrepreneurship link.

Theoretical contributions

This study makes several contributions to the literature. First, this study contributes to a stream of theoretical research on the temporal horizon of entrepreneurship (Lortie, Barreto, & Cox, Reference Lortie, Barreto and Cox2019; Nadkarni, Chen, & Chen, Reference Nadkarni, Chen and Chen2016; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yang, Ye and Khan2021). Our research echoes the call from Lévesque and Stephan (Reference Lévesque and Stephan2020) to address the time perspective in entrepreneurship and Lumpkin, Brigham, and Moss (Reference Lumpkin, Brigham and Moss2010) to identify issues of the link between temporal orientation and entrepreneurship. We suggest that a long-term orientation increases the likelihood of corporate entrepreneurial activities by cultivating enterprising people and/or identifying more entrepreneurial opportunities. The results align with previous research, demonstrating that time is an essential component of corporate entrepreneurship (Lévesque & Stephan, Reference Lévesque and Stephan2020; Nadkarni, Chen, & Chen, Reference Nadkarni, Chen and Chen2016).

Second, we contribute to the literature on the boundary conditions at the individual level that influence the firms' long-term orientation-corporate entrepreneurship nexus. The literature has generally focused on the boundary conditions on the firm level, for instance, those of the external environment, firm strategy, and resource implications (Baert, Meuleman, Debruyne, & Wright, Reference Baert, Meuleman, Debruyne and Wright2016; Engelen, Kube, Schmidt, & Flatten, Reference Engelen, Kube, Schmidt and Flatten2014; Heavey et al., Reference Heavey, Simsek, Roche and Kelly2009; Kor, Mahoney, & Michael, Reference Kor, Mahoney and Michael2007; Kreiser, Anderson, Kuratko, & Marino, Reference Kreiser, Anderson, Kuratko and Marino2020; Simsek, Veiga, & Lubatkin, Reference Simsek, Veiga and Lubatkin2007). However, few studies have shed light on the micro-foundation factors' moderating effect, although a strand of research on this topic is emerging (e.g., Cabral, Francis, and Kumar (Reference Cabral, Francis and Kumar2021)). In addition, prior research has primarily focused on the prior entrepreneurial experience and has paid less attention to the prior culture-related experience, such as work or study experience. Our study complements this line of research by revealing that entrepreneurs' prior working or studying experience acts as a critical micro-foundation factor in conditioning firms' long-term orientation-corporate entrepreneurship link. In other words, we incorporate a firm's temporal orientation and its entrepreneur's prior working or educational experience into an integrated framework to explore its interactive effects on corporate entrepreneurship. Our results show that an entrepreneur's work experience in a government and/or the military contributes to the positive impact of a firm's vast temporal horizon on its corporate entrepreneurship; however, an entrepreneur's overseas experience attenuates it. Therefore, our study is among the first to integrate micro-foundational cultural factors (i.e., prior experiences) into firms' temporal orientations (i.e., long-term orientations) to examine their combined effects on firms' corporate entrepreneurship decisions.

Finally, we contribute to stewardship theory by considering pre-employment factors (i.e., entrepreneurs' prior experience). Formerly, scholars assumed that all managers were either stewards or agents. However, this point of view has produced mixed outcomes (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, Reference Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson1997). A possible reason for this could be the incongruence between the orientations of firms and those of entrepreneurs. Moreover, firms have difficulty establishing a pure stewardship orientation because entrepreneurs' attitudes and abilities prior to their involvement in firms can strengthen or weaken their orientations (i.e., the degree of stewardship orientation) once they are employed by firms (Chrisman, Reference Chrisman2019). In particular, agency problems are difficult to prevent when a firm implements corporate entrepreneurship (Chung & Gibbons, Reference Chung and Gibbons1997). To address this challenge, this study not only adopts stewardship theory to describe the association between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship but also explores the moderating role of an entrepreneur's prior experience to highlight the extent of a firm's possible agency problem when it conducts stewardship governance. Our empirical findings demonstrate that a firm's long-term orientation can play a greater role in its corporate entrepreneurship when its stewardship governance and an entrepreneur's tendency are congruent. Any other arrangement produces a negligible effect on corporate entrepreneurship. Thus, this study answers calls for a more practical and relevant stewardship theory by incorporating pre-employment considerations into the assumptions of the stewardship theory (Chrisman, Reference Chrisman2019).

Practical Implications

This study has important implications for managerial practice. First, we strongly suggest that firms should establish a strong long-term orientation if they want to implement corporate entrepreneurship and avoid the issue of ‘myopia.’ Firms can overcome this disadvantage by fostering a stewardship culture. For example, employees should be developed by involving them in the firm's decisions, by increasing talent retention to improve talent management and development, and by identifying potential employees who share a similar stewardship tendency.

Second, the congruence between a firm's and its entrepreneur's stewardship orientation is pivotal. Our findings demonstrate that a firm with an entrepreneur who has military experience can drive corporate entrepreneurship in the most effective way by establishing a long-term orientation. That is, entrepreneurs who have previous and extensive experience as stewards are more entrepreneurial when a firm simultaneously implements long-term oriented activities. Therefore, we suggest that firms consider a potential entrepreneur's/CEO's/TMT member's prior experience before involving them because the congruent orientation between a firm and an entrepreneur/CEO/TMT member will significantly influence a firm's corporate entrepreneurship.

Third, we suggest that a firm's decision-makers should be aware of the rational boundary conditions because pure stewardship does not exist in a firm context, and the agency issue is difficult to prevent while a firm is implementing entrepreneurship. Our results on the moderating effects of an entrepreneur's prior overseas experience help to confirm this phenomenon, namely, that an entrepreneur's prior overseas experience weakens the association between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship. Accordingly, we suggest that a firm's decision-makers maintain an ambidextrous mindset to balance a stewardship with an agency orientation.

Conclusions

Conclusions

This Study investigates an important yet overlooked relationship in entrepreneurship: the impact of a firm's long-term orientation on corporate entrepreneurship. From the perspective of stewardship theory, we argue that a temporal horizon influences entrepreneurship. We found that the higher a firm's level of long-term orientation, the higher its level of corporate entrepreneurship. This positive relationship is strengthened by entrepreneurs with prior government or military experience but weakened by entrepreneurs with overseas experience. This study contributes to the literature on time perspective and micro-foundational factors in the context of corporate entrepreneurship, and calls for future studies to further enrich this research area.

Limitations and future research avenues

Our study has a few limitations that also suggest several future research avenues. First, we study a sample from China, which is influenced by the dominant Confucian culture, which is a steward culture (Liu, Dai, Liao, & Wei, Reference Liu, Dai, Liao and Wei2021). The generalizability of our findings to other countries may by constrained. Besides, the overseas experience of Chinese entrepreneurs could be with either individualistic or another collectivist culture. According to the results of our pre-interview, we find that overseas experiences in countries with individualistic cultures dominated in our samples; therefore, we did not posit an alternative hypothesis based on this sample. Otherwise, we might obtain different results. Thus, future research could enrich the variety of the samples to strengthen the generalizability of the findings. Second, most firms would have both their short-term and long-term goals and objectives, so a firm's temporal orientation may not be an either/or issue. Therefore, it would be interesting to investigate the orchestration of short-term orientation and long-term orientation in a firm in the future. Third, the data we used are from a secondary data survey conducted in 2014, which may not fully capture the impact of recent events, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, on corporate entrepreneurship. Future research could benefit from incorporating more recent data to explore the relationship between long-term orientation and corporate entrepreneurship. Additionally, our testing for CMV could be further enhanced through the use of methods such as the marker variable approach, the common latent factor approach, and the multigroup method, instead of solely relying on the traditional Harman's one-factor test. Finally, we mainly adopt the stewardship theory to interpret the moderating role of entrepreneurs' prior work or educational experience. However, we do not further explore the linkage between stewardship and agency, which could help to identify the further boundary conditions of the association between a firm's long-term orientation and its corporate entrepreneurship. It would be useful for future studies to determine whether a stewardship or an agency orientation is more appropriate in corporate entrepreneurship and to explore the additional relevant boundary conditions.

Acknowledgements

This paper is supported by Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project (20NDJC090YB). This research was also supported by the Major Humanities and Social Sciences Project in Colleges and Universities of Zhejiang Province of China (2021QN040). Besides, Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LY23G020002, and the Humanity and Social Sciences General Project of the Ministry of Education of China under Grant No. 22YJA630011 also provide support. The authors express their gratitude for the above financial supports, and the author also thanks anonymous reviewers and editors who gave constructive suggestions.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare none.

Dan Zhou (PhD, Zhejiang University) is an associate professor of strategy, innovation and entrepreneurship at Zhejiang University of Finance & Economics. Her research interests lie in service innovation and strategy. She has published her research in International Journal of Production Economics, Technological Forecasting & Social Change, Journal of Management & Organization, Innovation, and The Service Industry Journal, etc.

Weiqi Dai (PhD, Zhejiang University) is a professor of strategy and entrepreneurship, currently also the Associate Dean of School of Business Administration at Zhejiang University of Finance & Economics. He has published his research in journals such as Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Business Research, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, and Management World (in Chinese), among others.

Mingqing Liao (PhD, Shanghai University of Economics and Finance) is an associate professor at Guangdong University of Finance & Economics. His research interests focus on corporate finance and analysts forecasting. His works have appeared or are forthcoming in journals such as the Journal of Corporate Finance, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, and Applied Economics Letters, among others.