INTRODUCTION

Even though there are an estimated 370 million indigenous peoples around the world, <5% of the world’s population (United Nations, 2009), this statistical minority represents a third of the world’s 900 million poorest people (World Bank, 2016). Entrepreneurship has been identified as a major resource for indigenous self-empowerment, economic development and poverty reduction (Anderson, Reference Anderson2001; Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, Honig, & Dana, Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, Honig and Dana2004; Hindle & Lansdowne, Reference Hindle, Anderson, Giberson and Kayseas2005; Hindle & Moroz, Reference Hindle and Lansdowne2009), and this paper aims to systematically review literature on indigenous entrepreneurship. The purpose of the paper is to determine trends and commonalities in indigenous entrepreneurship models that could contribute to theoretical discussions and assist policy-makers and practitioners to improve their effectiveness in supporting indigenous economic and entrepreneurial development initiatives within sociocultural and geographically localized contexts.

Located in 90 countries, there are ~5,000 indigenous groups and close to 4,000 indigenous languages spoken around the world (United Nations, 2009). Additionally, according to Survival International, around 100 indigenous tribes have still not been discovered. The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD, 2012) states that the lands where indigenous peoples live represent 80% of the planet’s biodiversity and they have a fundamental role in managing the world’s natural resources (IFAD, 2012).

In varying proportions, indigenous peoples are present on the five continents. According to the IFAD (2012), 70% of the total international indigenous population lives in Asia. In China, according to the United Nations, the indigenous minority represents <9% of the total population, but accounts for about 40% of the country’s poorest population (United Nations, 2009). However, in some Latin American countries, such as Bolivia and Guatemala, indigenous peoples represent more than half of the total population (United Nations, 2009). In Africa, according to the International Work Group on Indigenous Affairs, there are an estimated 50 million indigenous peoples (African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 2006). In Australia, the 2011 Census Post Enumeration Survey estimated the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population at 662,300 people or about 3% of the total population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013). In Canada, indigenous peoples represent 4.3% of the total Canadian population and almost half of the Aboriginal population lives on reserves, but are increasingly migrating to urban areas all across Canada (Statistics Canada, 2013). In the United States, according to the 2010 Census, there are 2.9 million indigenous peoples, identified as American Indians and Alaska Natives (United States Census Bureau, 2012). According to the statistics presented here, indigenous peoples are considered an ethnic minority of the total population. The diversity among indigenous groups across the world is impressive from a cultural, socioeconomic and structural point of view (United Nations, 2009), but nonetheless indigenous peoples share some common problems, including discrimination, the expropriation of land, marginalization and violence, abuse and identity acceptance (United Nations, 2013). For this reason, the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous peoples has not adopted a general definition for indigenous peoples, instead, they consider the issue in terms of identification (United Nations, 2009).

The Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues was established in 2002 (resolution 57/197 of the General Assembly) within the United Nations’ New York-based Division for Social Policy and Development, to inform the United Nations organizations, governments and the public about the issues facing indigenous peoples worldwide and to promote exchanges between member states and representatives of indigenous peoples. In the 2015 resolution concerning the rights of indigenous peoples, the General Assembly of the United Nations requested that the President include representatives of indigenous organizations in official bodies with the Member States to allow indigenous representatives and institutions to participate in meetings of the United Nations. To protect indigenous peoples, the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples of the United Nations, adopted in 2007, stipulates the rights of these populations (UN General Assembly, 2007). Also, The International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, every August 9, was established in 1995 to raise awareness of the difficulties specific to indigenous peoples regarding human rights, education and health. In line with United Nations resolutions, various governments have been proactive regarding indigenous economic development, including governmental development strategies focused on entrepreneurship as a major resource for economic development and poverty reduction for indigenous peoples.

In Australia for example, the Australian Government’s Indigenous Economic Development Strategy aims to support the development of aboriginal entrepreneurship (Australian Government, 2007). In 2013, the Canadian Government implemented the Aboriginal Business and Entrepreneurship Development Program that aims to support indigenous entrepreneurs at different stages of the entrepreneurial process and provide funding for indigenous businesses through Aboriginal Financial Institutions.

Despite governmental efforts to develop indigenous entrepreneurship to improve indigenous well-being and indigenous economic empowerment, an underlying lack of indigenous specificity and contextualization has contributed to the failure of these initiatives (Shoebridge, Buultjens, & Lila Singh, Reference Shoebridge, Buultjens and Lila Singh2012). The need to understand the causes of these failures requires more contextualized research on indigenous entrepreneurship from an indigenous perspective in order to conduct in-depth and qualitative analysis of the contextual factors affecting indigenous entrepreneurship policies, strategies and practices around the world (Hindle, Reference Hindle2010).

A systematic review aimed at gathering, evaluating and synthesizing all of the studies on indigenous entrepreneurship is, therefore, important for its theoretical contribution, identification of indigenous entrepreneurship models and practices across different contexts, and for recommendations to policy-makers and practitioners on indigenous peoples’ aspirations for entrepreneurial and economic development.

This systematic review was conducted by electronically and manually searching articles through academic literature with querying eight selected databases (ABI/Inform Complete, Business Source Complete, Web of Science, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, Academic Search, Sociological Abstract, Entrepreneurial Studies Source, Bibliography of Native North America) and using specific words related to indigenous peoples such as Indigenous, Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islanders, First Nations, Native Nations, Native American, Metis, Inuits, American Indian and Native People. From 1,199 articles initially identified, 25 articles were selected for this systematic review. The results and analysis formed three broad models of indigenous entrepreneurship based on geographic localization and degree of urbanization: (1) urban indigenous entrepreneurship (UIE); (2) remote indigenous entrepreneurship; and (3) rural indigenous entrepreneurship.

Following the introduction, the paper is organized into five sections. First, the theoretical and practical needs for this systematic review are outlined. Second, the research protocol and methodological aspects are introduced. Third, the main findings of the systematic review are presented and analyzed. Fourth, the characteristics of the three indigenous entrepreneurship models are presented and discussed. Fifth, the implications of the study are presented in the conclusions and avenues for future research on indigenous entrepreneurship are suggested.

Indigenous entrepreneurship and the systematic review context

In the academic literature, indigenous entrepreneurship has been defined as, ‘the creation, management and development of new ventures by Indigenous peoples for the benefit of Indigenous peoples’ (Hindle & Lansdowne, Reference Hindle, Anderson, Giberson and Kayseas2005: 132). Therefore, according to the definition proposed by the authors, the concept of indigenous ownership and benefit are central to indigenous entrepreneurship. In recent decades, research on indigenous entrepreneurship has begun to appear in the literature (Hindle & Lansdowne, Reference Hindle, Anderson, Giberson and Kayseas2005; Peredo & Chrisman, Reference Peredo and Chrisman2006; Dana & Anderson, Reference Dana and Anderson2007; Frederick, Reference Frederick2008; Dana, Reference Dana2015). This topic has affirmed itself as an independent field of research from the mainstream entrepreneurial literature and is distinct from ethnic entrepreneurship, which mostly concerns the entrepreneurial activities of immigrants or other major ethnic groups (Dana, Reference Dana2007b), even if differences and similitudes need to be explored further between indigenous entrepreneurship and ethnic entrepreneurship (Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, Honig and Dana2004; Kushnirovich, Heilbrunn, & Davidovich, Reference Kushnirovich, Heilbrunn and Davidovich2017).

The initial literature on indigenous entrepreneurship identified indigenous values as the driving force behind entrepreneurial activities, providing evidence that indigenous entrepreneurs see entrepreneurship differently from the classic individualistic perspective that has emerged in the mainstream literature on entrepreneurship (Anderson, Reference Anderson1999, Reference Anderson2001; Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2005). This literature also emphasized indigenous entrepreneurship as a tool for indigenous economic development, overcoming the exogenous economic development conception of indigenous communities through external assistance (Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, Honig and Dana2004). Therefore, this endogenous view of indigenous economic development recognized the efforts of indigenous entrepreneurs in building their own socioeconomic community development and indigenous empowerment in the global economy (Anderson & Giberson, 2004; Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, Honig and Dana2004).

Since the 2000s, however, the theoretical debate in the indigenous entrepreneurship literature has focused more closely on understanding the different indigenous contexts and their indigenous entrepreneurial outcomes (Hindle, Reference Hindle2010). In this regard, it is appropriate to recall that, globally, indigenous entrepreneurs belong to very diverse indigenous realities with respect to their geographical position, history and political status (United Nations, 2009). Moreover, these specific indigenous realities have emerged from their own national realities regarding their attitudes toward resisting cultural assimilation and striving for self-indigenous affirmation (Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, Honig and Dana2004). Despite the fact that context has been recognized as an important factor affecting entrepreneurial activities in mainstream entrepreneurship (Welter, Reference Welter2011), very few studies have emerged on the specificities of different entrepreneurial configurations in indigenous contexts.

Recent literature on the topic of indigenous entrepreneurship models, however, suggests that a contingency approach should be adopted to analyze and illuminate the different community entrepreneurial models (Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, Honig and Dana2004; Hindle, Reference Hindle2010). Although there is consensus in the indigenous entrepreneurship literature on the question of ‘why’ and ‘what’ indigenous entrepreneurship is, the question of ‘how’ it occurs requires more research before endogenous models of indigenous entrepreneurship can be established. In support of this theoretical position, some researchers (Shoebridge, Buultjens, & Lila Singh, Reference Shoebridge, Buultjens and Lila Singh2012) have demonstrated the minimal success of some governmental policies and initiatives on indigenous entrepreneurship. In this regard, the social cognitive theories of entrepreneurship show that entrepreneurial behavior is not universal and it can change according to the cognitive perspectives of the entrepreneurs (e.g., Mitchell, Busenitz, Lant, McDougall, Morse, & Smith, Reference Mitchell, Busenitz, Lant, McDougall, Morse and Smith2002). Hindle (Reference Hindle2010) highlighted this issue in the indigenous entrepreneurship literature by proposing a diagnostic model to analyze indigenous contextual factors, cultural and structural, that need to be considered for outlining different indigenous entrepreneurship outcomes.

This theoretical debate represents the starting point for this systematic review. The relationship between indigenous entrepreneurs, the indigenous community and the context within which they are all situated is highlighted as a nongeneralizable and complex relationship, requiring further exploration.

If certain conceptual evidence concerning indigenous entrepreneurship is considered such as the differences between indigenous and nonindigenous entrepreneurs (Dana, Reference Dana2007a), the motivations of indigenous entrepreneurs (Foley, Reference Foley2003; Dana, Reference Dana1995; Dana, Reference Dana2007a; Hindle & Moroz, Reference Hindle and Lansdowne2009) or the strategies they put in place to successfully develop indigenous entrepreneurship (Ferrazzi, Reference Ferrazzi1989; McDaniels, Healey, & Kyle Paisley, Reference McDaniels, Healey and Kyle Paisley1994; Hindle, Anderson, Giberson, & Kayseas, Reference Hindle and Moroz2005), a theoretically integrated study on indigenous entrepreneurship literature that exists could help to overcome the lack of awareness and understanding of indigenous entrepreneurship models in scholarly literature (Anderson, Reference Anderson2001; Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, Honig and Dana2004; Hindle & Lansdowne, Reference Hindle, Anderson, Giberson and Kayseas2005; Hindle, & Moroz, Reference Hindle and Lansdowne2009).

While initiatives and governmental programs are locally based, in the indigenous entrepreneurship literature, the theoretical debate focuses more closely on modeling indigenous entrepreneurship and identifying contextual factors (Hindle, Reference Hindle2010). Despite the fact that indigenous entrepreneurship has been affirmed as a full field of research in the last decade (Hindle & Moroz, Reference Hindle and Lansdowne2009), the universality of indigenous entrepreneurial models is still a relatively un-explored phenomenon.

Thus, there is a theoretical and practical need to conduct a systematic review on international indigenous entrepreneurship. As highlighted by Denyer and Tranfield (Reference Denyer and Tranfield2009), the legitimacy of developing a systematic literature review is based both on the theoretical debate around the chosen topic and on the practical utility of the systematic review’s results.

Regarding the theoretical justification for this systematic review, an analysis of the indigenous entrepreneurship literature reveals the need to identify various indigenous entrepreneurial models and their characteristics. Indeed, the legitimacy of indigenous entrepreneurship as a branch requires a better understanding of different indigenous entrepreneurship contexts. This systematic review is further justified by the current theoretical debate on the topic put forward by Hindle (Reference Hindle2010) who established the need for a contextualized analysis of indigenous entrepreneurship, and also by the growing maturity of the indigenous entrepreneurship literature in the last 20 years. Regarding the practical justification for a systematic review, despite governmental and international initiatives for the benefit of indigenous peoples and their entrepreneurial and economic development, these initiatives lack contextualized strategies that reflect the different indigenous realities that exist around the globe (United Nations, 2009).

Therefore, this systematic review aims to answer the research question: what are the indigenous entrepreneurship models and practices according to the different indigenous contexts globally? By identifying and comparing scholarly literature on indigenous entrepreneurship across various national and geographic contexts, an integrative framework could be developed that allows policy-makers and practitioners to adapt initiatives for the economic and entrepreneurial development of indigenous peoples. The theoretical objective of this systematic review is to illuminate the different indigenous entrepreneurship characteristics and models, and integrate these in a way that is applicable in a variety of contexts. The practical objective of this systematic review is to provide practitioners with a comprehensive review of the literature and to orient decision-makers toward contextualized indigenous entrepreneurship strategies and models.

METHODOLOGY

A systematic review is a rigorous and scientific literature review process aimed at gathering, evaluating and synthesizing all of the studies on a predetermined topic. It also identifies the gaps in the literature to help further scientific knowledge (Kitchenham, Reference Kitchenham2004; Staples & Niazi, Reference Staples and Niazi2007; Denyer & Tranfield, Reference Denyer and Tranfield2009). A systematic review differs from a classic literature review because it is based on recognized scientific methods (Tranfield, Denyer, & Smart, Reference Tranfield, Denyer and Smart2003) and on a well-defined research strategy (Kitchenham, Reference Kitchenham2004). Systematic reviews are, therefore, based on a scientific process since it guarantees the objectivity of the approach, its transparency and its ability to be reproduced by other researchers (Tranfield, Denyer, & Smart, Reference Tranfield, Denyer and Smart2003).

Kitchenham (Reference Kitchenham2004) identified three major phases for conducting a systematic review: (1) planning the review; (2) conducting the review; and (3) reporting the review. The first phase of a systematic review – planning the review – refers to identifying both the theoretical and practical needs to conduct a systematic review. It also includes developing a research protocol. This has been completed in the previous section. The second stage – conducting the review, refers to the process of identifying studies, the selection process, the study quality assessment, the data extraction, monitoring, synthesis and analysis. The third phase – reporting the review, refers to the results and the discussion of the systematic review.

The following section outlines how the search strategy for this systematic review on indigenous entrepreneurship in different contexts globally was developed. This refers to the step-by-step methodological aspects of conducting the systematic review: the selection of electronic databases, the keyword search string, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the time horizon, the study quality assessment procedure, and the manual search methods utilized, including the identification of the most cited papers and the most relevant authors.

Electronic databases

To complete this systematic review, eight specialized databases were identified on the advice of a librarian specialist in documentary resources in business and entrepreneurship. As outlined by Dana and Anderson (Reference Dana and Anderson2007), it was important to consider the multidisciplinary nature of indigenous entrepreneurship (i.e., from the perspectives of anthropology, business, management and sociology) when selecting the electronic databases. The eight identified databases are given in Table 1.

Table 1 Electronic databases used in the study

Keyword search string

The electronic databases were searched using a predefined keyword search string. The first part of the keyword search string concerned the study population: indigenous peoples. It is appropriate to note that in the scientific literature, the term ‘indigenous’ is a generic term designating various indigenous peoples around the world and that its operational definition can vary according to the different indigenous groups (United Nations, 2009). Therefore, for the sake of completeness, all terminologies related to indigenous peoples that were identified using a Thesaurus (available on the article database systems) were included in the keyword search string. The second part of the keyword search string concerned the intervention, that is, the object under study, which in this case was entrepreneurship. To avoid a study procedure that was too selective, other keywords generated from the research question, such as concepts, characteristics or models, were not included in the search strategy. The keyword search string used for the electronic search was:

Indigenous OR Aboriginal OR Torres Strait Islanders OR First Nations OR Native Nations OR Native American OR Metis OR Inuit OR American Indian OR Native People

AND

Entrepreneur*

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Concerning the inclusion criteria chosen for this systematic review, only peer reviewed and academic articles, published in English and presenting cultural, social and organizational variables were included. Other variables, such as individual, economic or financial variables, were not taken into consideration for this study because they are not congruent with this study’s research question, which requires the analysis of the sociocultural contexts of indigenous entrepreneurship. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are given in Table 2.

Table 2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Time horizon

The time horizon for this systematic review spanned from January 1, 1995 to December 31, 2016. The first year included in this systematic review, 1995, is the year that the International Day of the World Indigenous People was established, following the decision of the United Nations General Assembly in 1994. It is acknowledged that research on indigenous entrepreneurship may have been published prior to 1995, but it is widely accepted in the academy that research on indigenous entrepreneurship seems to emerge in the 2000s (Hindle, Reference Hindle2010).

Quality assessment procedure

As Kitchenham (Reference Kitchenham2004) pointed out, although quality is difficult to define, criteria must be applied to guarantee the systematic review’s quality. To determine if indigenous entrepreneurship is a recognized topic in the international academy, a journal ranking verification system, following the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) ranking, served as the quality criteria. The identified journals that were not part of the ABDC ranking were excluded, although it is acknowledged that publications outside of the ABDC ranking system could be considered in future research with a more critical interpretation of what constitutes ‘quality’ literature.

Preliminary results

Searching the eight databases using the previously defined keyword chain gave an initial result of 1,796 articles. The distribution of the number of articles obtained from the eight databases searched is shown in Table 3. A rigorous selection process was conducted (Kitchenham, Reference Kitchenham2004) and the End Note software was used at the various stages to keep an accurate record of the article details.

Table 3 Articles according to databases

Elimination process

The selection process started by eliminating duplicates. This reduced the number of articles to 1,199 from the 1,796 articles that were initially identified from the eight electronic databases. After eliminating the duplicates, two major stages were implemented. First, the titles, abstracts and the keywords were read to verify the articles’ congruence with the keyword chain and research question driving the systematic literature review. This operation resulted in the selection of 168 articles from 1,199 articles.

In the second stage, the articles were read in full to identify those that analyzed the phenomenon chosen for this study, specifically the sociocultural context of indigenous entrepreneurship. This process resulted in the selection of 24 articles from the 168 articles identified during the first selection process.

Finally, the quality control procedure was applied to these 24 articles eliminating those journals that were not included in the Australian ABDC ranking. This lead to a final result of 20 articles selected from the electronic database search.

Manual process

Using the results of this electronic database search, a complementary manual search was conducted. First, the references from the final papers selected using the electronic search were used to identify those papers on indigenous entrepreneurship responding to the inclusion criteria of this systematic review that were not found using the electronic search. With this verification process, two more articles were added after applying the quality control.

To the final list, journals that were cited more than once were identified: Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, and Journal of Enterprising Communities: people and places of global economy. A manual search of indigenous entrepreneurship articles responding to the inclusion criteria established for this systematic review was conducted in the two journals ABDC ranked (Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship and Journal of Enterprising Communities: people and places of global economy) covering the entire period of this systematic review, from January 1, 1995 to December 31, 2016. However, no relevant articles were added during this stage.

Then, a manual search was completed by identifying the most important authors, which are those who appeared as authors at least twice in the final list of selected articles. These authors were contacted by email to obtain their complete list of publications on this topic. This process added two more articles. Finally, an internet search was conducted using the words in the keyword search string, and one more article was added during this step. This lead to a final result of 25 articles that were included in this systematic review. The final list of selected articles is presented in Table 4 and the entire selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Selection process

Table 4 Final articles selectedFootnote a

a E=electronic search; R=references control; A=most important authors; I=internet.

Analytical process

The analysis on the selected articles was performed using an Excel file that contained the information necessary to develop the descriptive, in-depth and critical analysis of the indigenous entrepreneurship literature gathered. The descriptive analysis included the publication year, methodology, journal and the geographical area of the research. A more in-depth analysis included identification of the indigenous entrepreneurship models, the theoretical perspectives used in the studies, the research questions and the methods used by researchers. The critical analysis of the studies included an analysis of the localization or sociocultural contexts of the studies, a summary of the key results, the limitations of the studies and the avenues for future research. All levels of analysis will now be presented.

Trend in the research focus

The period of the articles selected for this systematic review begins in 1999. It is evident that the literature from the 2000s onward tends to explain indigenous entrepreneurship as a lever for economic development rather than understanding the different practices and models of indigenous entrepreneurship (Anderson, Reference Anderson2001). The evolution of the studies over time is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Literature trend analysis

Trend in methodology

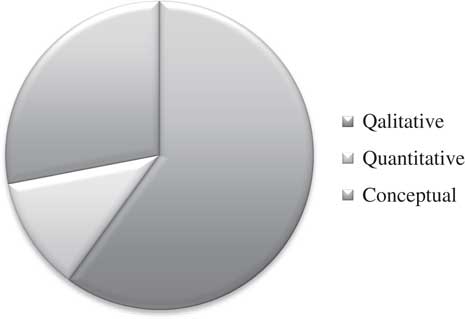

Regarding the methodology, most of the studies (15) were conducted using a qualitative method, as interviews, non-participants’ observations and case studies, while a minority were conducted using a quantitative method (3). The rest of the studies analyzed were conceptual (7). The methodological distribution of the studies is given in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Methodological trend

Trend in the sociocultural context of studies

Most of the studies selected focus on North America (8), and Oceania (11). The rest of the studies (7) focus on other areas of the world, which are Africa (3), India (1), China (1), Finland (1) and Pakistan (1). With regards to Oceania, studies have a focus on New Zealand (6), Australia (4) and Samoa (1). One of these studies (April, Reference April2008) is on New Zealand and Africa. With regards to North America, they concern mainly Canada (7) and United States (1).

In the studies on indigenous entrepreneurship in Oceania, much of the literature is focused on providing governments with the tools to promote and develop indigenous entrepreneurship as a particular form of entrepreneurship that can contribute to national economic development (e.g., Zapalska, Dabb, & Perry, Reference Zapalska, Dabb and Perry2003). Therefore, this literature mostly includes policy recommendations oriented toward and focused on action plans and initiatives to be implemented. However, this body of literature shows the variety of sociocultural contexts of indigenous communities in Oceania, according to the cultures of indigenous peoples of New Zealand (e.g., Foley, Reference Foley2008; Tapsell & Woods, Reference Tapsell and Woods2008) and of Australia (e.g., Curry, Reference Curry2005; Lee-Ross & Mitchell, Reference Lee-Ross and Mitchell2007).

On the contrary, indigenous entrepreneurial literature in North America is more descriptive and ethnographic, focusing on the way indigenous peoples live in their communities. Moreover, literature in North America underlines the differences in the structural factors impacting indigenous entrepreneurial activities in these community’s contexts, with regards, for example, to Inuit peoples located in the Canadian North (e.g., Mason, Dana, & Anderson, Reference Mason, Dana and Anderson2009; Dana & Anderson, Reference Dana and Anderson2011), which is very different from the social and cultural contexts of Native Americans in the United States (Pascal & Stewart, Reference Pascal and Stewart2008).

Literature on indigenous entrepreneurship in the other locations around the world, such as Africa (Co, Reference Co2003; Ndemo, Reference Ndemo2005; April, Reference April2008), India (Brouwer, Reference Brouwer1999), China (Chan, Iankova, Zhang, McDonald, & Qi, Reference Chan, Iankova, Zhang, McDonald and Qi2016), Finland (Dana, Reference Dana2008) and Pakistan (Khan, Reference Khan2014), demonstrated the variety of social and societal contexts not only with regards to indigenous entrepreneurship, but also with regards to indigenous peoples’ conditions of life. In the case of Africa, for example, socioeconomic and religious variables (Co, Reference Co2003) tend to be included in the analysis of indigenous entrepreneurship to explain the disadvantages indigenous peoples face.

DISCUSSION

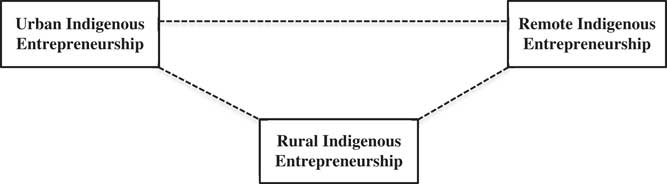

By analyzing the final articles selected for this systematic review, three indigenous entrepreneurship models were interpreted: (1) the UIE model; (2) the remote indigenous entrepreneurship model; and (3) the rural indigenous entrepreneurship model. This continuum of indigenous entrepreneurship models resulted from analyzing the different entrepreneurial research perspectives that were adopted to analyze indigenous entrepreneurship in different sociocultural localizations that varied from urban, rural to remote. These entrepreneurial research perspectives are represented by the analysis of entrepreneurship as enterprises and small businesses creation, informal activities of entrepreneurs and subsistence activities of indigenous peoples.

Therefore, these classification models offer a systematic way to organize the insights from a systematic review of indigenous entrepreneurship literature that is contextualized by considering the relationship between an indigenous community’s localization and the forms of entrepreneurship the community undertakes, situated within the definition of entrepreneurship through which indigenous entrepreneurship has been analyzed.

Indigenous realities can vary considerably within the same country (United Nations, 2009). Forming contextualized indigenous entrepreneurship models (i.e., urban, rural, remote) enabled consideration of indigenous peoples and communities as independent of the country in which they are located, acknowledging their aspirations to preserve their indigenous identity, cultures and history within a particular geographical location (Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, Honig and Dana2004).

The critical analysis of articles selected indicated that the sociocultural context of indigenous communities and degree of urbanization are central to the classification of indigenous entrepreneurship models outlined in this paper. This is because sociocultural context and degree of urbanization in particular may affect how much external and national cultural influences affect the indigenous culture and way of life and this is reflected in the processes and outcomes informing the indigenous entrepreneurship models.

According to the analysis, UIE and remote indigenous entrepreneurship represent indigenous entrepreneurial outcomes at opposite ends of the spectrum. However, the rural indigenous entrepreneurship model represents an intermediary one. The three models are discussed and compared in the following sections, and the framework for the indigenous entrepreneurship models is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Indigenous entrepreneurship models framework

UIE model

The UIE model represents the indigenous entrepreneurship that emerges in urban contexts. The UIE model is similar to the mainstream entrepreneurship model, which is based on a capitalist conception of entrepreneurial activities and focuses on formal business creation. The analysis of UIE indicated a capitalist and mainstream interpretation of entrepreneurship that was applied to indigenous entrepreneurship processes and outcomes in the urban context. UIE is characterized by the availability of infrastructure, technological tools, information networks and business opportunities in urban settlement areas, influencing, therefore, indigenous entrepreneurial activities that are based in urban contexts.

For example, Johnstone (Reference Johnstone2008) described a successful model of economic development in a study of one Mi’kmaq community, the Membertou First Nation in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. This community is an urban-based reserve located in the city of Sidney, Nova Scotia, that has taken advantage of its geographical position to improve its economic development. The community leaders accomplished this by attracting nonindigenous entrepreneurs not from the reserve and inviting them to conduct businesses in the community. The study by Johnstone measured success in this context in terms of profitability and economic development. Therefore, the researcher analyzed indigenous entrepreneurship with respect to the development of organizations, specifically focusing on sole proprietorship enterprises. The definition of indigenous entrepreneurship used in the study is close to the mainstream definition of entrepreneurship. Thus, the study participants selected are individual entrepreneurs according to the capitalistic paradigm of entrepreneurship, based on wealth accumulation. This model parallels the Western model of entrepreneurship that is mainly based on the identification of opportunities (Shane & Venkataraman, Reference Shane and Venkataraman2000) and takes shape with the creation of formal businesses.

In their analysis of entrepreneurship in Iqaluit, the capital of Nunavut, Canada, Dana, Dana, and Anderson (Reference Dana, Dana and Anderson2005) argued that indigenous peoples are lost between two worlds, the traditional Inuit world and the modern non-Inuit world. In this way, proximity to the “modern” world, represented by nonindigenous peoples, affects the authenticity of indigenous entrepreneurship. In their study on indigenous entrepreneurship in Iqaluit, the researchers conducted interviews with opportunity-seeking individuals, people who choose to become entrepreneurs, which the authors defined according to the Western model of entrepreneurship, and individuals engaged in reactionary self-employment, motivated by a given situation such as the need to fulfill personal needs. The ‘Western’ conception of entrepreneurship also influences the UIE model through the presence of nonindigenous inhabitants, who may also be living in the indigenous urban contexts. In his study on the development of cooperatives in Nunavik, Dana (Reference Dana2010) defines Kuujjuak, known as Fort Cimo until 1980, as a modern Inuit urban settlement that was created to establish Western companies.

In their study on the entrepreneurship of the indigenous peoples of New Zealand, the Māori, Haar and Delaney (Reference Haar and Delaney2009) analyzed Māori entrepreneurship, adopting the rational and Western perspective of entrepreneurship as business creation and attempted to understand how indigenous values are integrated into and affect the overall evolution of a business, in terms of business success, performance and opportunity recognition. The introduction of the concept of ‘whanaungatanga,’ a Maori cultural value related to the collective form of communication and sharing, could be a useful resource for indigenous entrepreneurs in terms of establishing collective networks in urban contexts. Additionally, the authors found that Māori entrepreneurs have developed networks within the urban context to overcome the barriers to indigenous entrepreneurship and promote the diversification of businesses in non-traditional areas.

As underlined by Foley and O’Connor in their study of Aboriginal Australians, Native Hawaiians and the Māori of Aotearoa, New Zealand, indigenous entrepreneurship in urban areas offers the unique possibility of networking with nonindigenous peoples (Foley, Reference Foley2008; Foley & O’Connor, Reference Foley and O’Connor2013), an element that suggests UIE models are similar to modern and westernized explanations of entrepreneurship.

The UIE model is also similar to ethnic entrepreneurship (Anderson & Giberson, Reference Anderson and Giberson2003; Dana, Reference Dana2007b), because, as indigenous entrepreneurship studies on urban localizations show, it is characterized by a tendency to integrate the indigenous cultural paradigm with the dominant cultural paradigm (Peredo et al., Reference Peredo, Anderson, Galbraith, Honig and Dana2004).

Remote indigenous entrepreneurship model

Contrary to the UIE model, the remote indigenous entrepreneurship model takes place in remote contexts where indigenous entrepreneurship is oriented more toward sustainable economic development operated by indigenous entrepreneurs. The very low level of urbanization of some remote indigenous communities characterizes the difficulties facing any remote environment with respect to the modern and Western conception of entrepreneurship. Therefore, these remote localizations affect indigenous entrepreneurship and how it is practiced as well as impacting the way indigenous cultures are preserved in remote indigenous communities. Moreover, regarding remote indigenous entrepreneurship, the researchers adopted a more indigenous approach which aimed to describe the experience and practices of indigenous entrepreneurs through narratives, interviews and ethnography.

Khan (Reference Khan2014) conducted the first study on the Kalash community of northern Pakistan, an indigenous tribe living in villages located in three isolated mountains: Bumburet, Rumbur and Birir. The Kalash community is an indigenous tribe that has preserved its own culture largely as a result of its remote location. In the study, Khan highlighted the ancestral culture and traditional practices of Kalash peoples characterized by an agro-pastoral division of labor and a pastoral subsistence economy. With case study analysis and in-depth interviews taking the narrative forms of entrepreneur’s experiences and practices, the researcher attempted to explore the entrepreneurship world of this remote community. The researcher also emphasized the importance of reconciling cultural heritage with modernism and concluded with the challenges facing the development of entrepreneurship in remote areas.

Mason, Dana, and Anderson (Reference Mason, Dana and Anderson2008) analyzed entrepreneurship in Coral Harbour, a remote community in Nunavut, Canada. In this study, the authors investigated whether, for communities in these remote contexts where employment prospects are low and infrastructure and services are limited, entrepreneurship provides a means of self-sufficiency. The research design consisted of observing participants, conducting in-depth interviews and involving community members in the overall research process. Using these methods, the authors observed that entrepreneurship in this remote community was generally represented by self-employment that relied on natural and knowledge resources traditionally available in the community. For example, the researchers described the preparation of certain products, sculptures, rings and clothing, as representative of the community’s commercial activities. In the analysis, the authors outlined how these products are the results of a specific cultural heritage and that the indigenous business and knowledge is transmitted from family to family.

In a remote community in Nunavut, Arviat, Dana and Anderson (Reference Dana and Anderson2011) found that the community mainly consisted of indigenous Inuit inhabitants. In this context, entrepreneurial activity consisted of subsistence activities based on fishing, hunting and trapping. Mason, Dana, and Anderson (Reference Mason, Dana and Anderson2009) in their study in Rankin Inlet, a remote community in Nunavut, recognized the existence of some formal businesses in the community. However, they emphasized that informal entrepreneurship in the form of commercial transactions that are not legally structured and subsistence self-employment activity where there is no commercial transaction are prominent in the community.

Fuller, Buultjens, and Cummings (Reference Fuller, Buultjens and Cummings2005) analyzed the viability of an indigenous business development operated by an indigenous clan in Ngukurr, a remote Indigenous community in Northern Australia. The authors concluded that the cultural values, the traditions of indigenous peoples, and their attachment to their land need to be considered as a priority in the business development practices of indigenous entrepreneurs.

The remote indigenous entrepreneurship model is characterized by the dominant paradigm of the indigenous cultures, where, due to the remoteness of these communities, there is minimal opportunity for mainstream culture to influence indigenous cultures or expressions of indigenous entrepreneurship. While the sociocultural isolation of certain indigenous communities from mainstream communities makes it easier to preserve indigenous culture and ways of life, it also hinders entrepreneurial activities due to a lack of clients and the means for entrepreneurial development. When indigenous peoples reside in remote areas, the lack of mentors, market opportunities and the appropriate infrastructure for entrepreneurial development is evident. Thus, entrepreneurship mainly takes the form of self-subsistence (Mason, Dana, & Anderson, Reference Mason, Dana and Anderson2009). Therefore, the remoteness of some indigenous communities deprives many, if not most, entrepreneurs of the necessary tools for their entrepreneurial activities in the modern conception of the term.

Rural indigenous entrepreneurship model

The rural indigenous entrepreneurship model represents an intermediate step between the UIE model and the remote indigenous entrepreneurship model. This rural model is specific to indigenous communities localized in rural contexts, where the way of life combines tradition and modernity (Lee-Ross & Mitchell, Reference Lee-Ross and Mitchell2007; Dana, Reference Dana2008).

In his study on indigenous entrepreneurship in rural villages in Papua New Guinea, Curry (Reference Curry2005) analyzed how the social embeddedness of indigenous businesses in rural contexts affects the insolvency of indigenous enterprises. In doing this, the author outlined the importance of the indigenous logic of exchange (gift exchange) and the importance of indigenous social dimensions in shaping indigenous small businesses. Using two case studies, the author concluded that in rural communities, the logic of profit accumulation is still subordinate to the indigenous logic of exchange and the community’s social rules. These two dominant factors, therefore, affect indigenous business relationships and practices. Functioning between subsistence and capitalism, indigenous businesses in rural areas have objectives that are broader than economic interests.

Cahn (Reference Cahn2008) conducted a similar case study on microenterprises in certain rural indigenous communities in the country of Samoa, the Pacific Islands. In this study, Cahn explored the relationship between indigenous entrepreneurship and the Samoan culture and way of life, called fa’a Samoa, to understand the sustainability of microenterprises. The researcher argued that harmonization between the indigenous way of life and small businesses is important to ensuring the sustainability of the enterprises. In indigenous communities where indigenous exchanges prevail between community members, the enterprises achieve both economic and noneconomic outcomes. Moreover, in the rural context, entrepreneurial activities can be collectively organized because the entire community becomes the entrepreneur and the goals of the entrepreneurial activities are the community’s goals. In this case, rural entrepreneurial activities are mostly community oriented.

In his study on how globalization affects local indigenous enterprise development in the south Indian state of Karnataka, Brouwer (Reference Brouwer1999) emphasized this community aspect and demonstrated the importance of indigenous values for indigenous entrepreneurs. The author affirmed that the perspectives in India’s internal regions differ considerably from those in the coastal regions. This is reflected in entrepreneurial activities that are based on the logic of social exchange.

In a study on entrepreneurship in the Masaai indigenous tribe in Kenya, Africa, Ndemo (Reference Ndemo2005) analyzed how the changes imposed by modernity, for example, the modernization of land, affect the Masaai peoples’ entrepreneurship behavior. The Masaai community has traditionally been organized into a pastoralist communal system with a semi-nomadic lifestyle. The researcher investigated how the Masaai people perceived the transition from pastoralism to modern entrepreneurship because the Maasai people’s traditional economic system is different from the national market economy. In total, 113 enterprises located in different Masaai districts were sampled for the survey. The researchers analyzed the enterprises using the modern conception of entrepreneurship development, including opportunity recognition, small business management and orientation to success. The research results showed that even when the Masaai peoples are motivated and encouraged to be entrepreneurs, their indigenous culture remains the most important factor.

Indigenous peoples living in rural areas face social and economic changes. Chan et al. (Reference Chan, Iankova, Zhang, McDonald and Qi2016), highlight this aspect in the study on tourism gentrification in indigenous rural areas that they conducted in China. The indigenous Hani and Yi communities in the Honghe Hani Rice Terraces in the Yunnan Province of southern China have maintained the rice-terrace ecosystem for years, as a local cultural practice for subsistence. The development of tourism and the related gentrification in this rural area has brought changes and challenges to the traditional way of life for these indigenous peoples.

April (Reference April2008) analyzed the entrepreneurial activities of two indigenous groups located in two different countries: the Khoi-Khoi of Namibia, a subtribe of the San people and the Ngai Tahu peoples, a subtribe of the Māori of New Zealand. These two indigenous groups live in different sociocultural contexts. However, both must navigate the tension between individualism and collectivism regarding entrepreneurial activities, based on the resources of their lands for subsistence. The study recognized the importance of culture to these two indigenous groups, and the researchers investigated how their cultural values can motivate entrepreneurial activities.

Pascal and Stewart (Reference Pascal and Stewart2008) recognized the importance of a community’s geographical position. In their study on Native American entrepreneurship, they analyzed the relationship between indigenous firm performance and proximity to economic clusters. As many Native American reservations are located in rural areas, the study’s conclusion suggested that economic clusters in urban areas affect indigenous firm performance.

A comparative analysis of indigenous entrepreneurship models

The three indigenous entrepreneurship models that were collectively identified, urban, remote and rural, represent the different features and practices of indigenous entrepreneurship in these diverse geographical contexts. As previously mentioned, the localization of indigenous communities determines the degree of external cultural impact on indigenous values, entrepreneurial behavior and outcomes. This is also reflected in the theoretical perspectives and different methodologies researchers use to study indigenous entrepreneurship according to these contexts or localizations that traverse national borders. Therefore, the relationship between indigenous entrepreneurship, the contextual location of the community and the theoretical perspectives informing these studies contributed to the identification of indigenous entrepreneurship models’ elements and outcomes.

Overall, Tapsell, and Woods (Reference Overall, Tapsell and Woods2010) highlighted that context has often been overlooked when it comes to indigenous entrepreneurship, especially in relation to identifying the opportunities that underpin entrepreneurial activities. In fact, not only is opportunity affected by cultural perception, but it is also determined by sociocultural context and location. For this reason, entrepreneurial experiences, opportunities and outcomes in urban, remote and rural contexts differ. Therefore, in the analysis of indigenous entrepreneurship models, localization is not the only important variable. It represents a starting point for capturing the reality of indigenous entrepreneurship.

According to the analysis of the literature systematically reviewed, the urban and remote indigenous entrepreneurship models represent opposite ends of the spectrum. The localization of indigenous communities is an important consideration (Reihana, Sisley, & Modlik, Reference Reihana, Sisley and Modlik2007), as an urban location can influence the opportunity to create a business and ensure its development, according to the modern conception of business and entrepreneurship. This is mostly specific to the UIE model, where proximity to the modern world influences the entrepreneurial outlook and motivation for profit of indigenous individuals and communities. The theoretical perspectives on entrepreneurship that researchers have adopted when studying indigenous entrepreneurship in urban contexts consider the proximity to modernity and formal business creation models.

In contrast, the remote indigenous entrepreneurship model describes entrepreneurship in indigenous communities that are connected to the traditional indigenous way of life and still isolated from modernity. In these remote contexts, the indigenous peoples continue practicing subsistence activities.

As an intermediate step between these two models, the rural indigenous entrepreneurship model describes communities that are based mainly on pastoralism and practice a way of life that is connected to the land and the resources it provides. Even though the indigenous peoples living in these rural locations tend to practice a modern form of entrepreneurship, they face social and economic challenges and operate at the interface between the modern and the traditional way of life. At the same time, it also represents the interface between urban and remote indigenous entrepreneurship research perspectives. For example, researchers that focus on rural indigenous entrepreneurship focused both on the enterprises, from a modern perspective, and on the culture of indigenous peoples, from an indigenous perspective. The characteristics of each model are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5 Indigenous entrepreneurship models specificities

The characteristics of each of the indigenous entrepreneurship models proposed represent important criteria for analyzing contextualized indigenous entrepreneurship that should be developed into an authentic indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Recently, entrepreneurship studies (e.g., Manimala & Wasdani, Reference Manimala and Wasdani2015) have shown the importance of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approaches based on a systemic approach to entrepreneurship that recognize the importance of the environment in entrepreneurial development. This field sees, therefore, entrepreneurial activity as an individual’s ‘response’ to their entrepreneurial environment rather than an individual ‘action’ analyzed from a microperspective that focuses exclusively on the attitude and behavior of the individual entrepreneurs. Even though the concept of entrepreneurial ecosystems conceived on the notion of territoriality has only been applied to regions, nations and countries (e.g., Kim, Kim, & Yang, Reference Kim, Kim and Yang2012; Acs, Autio, & Szerb, Reference Acs, Autio and Szerb2014) the concept has not yet been explored in reference to sociocultural contexts or locations of indigenous communities. This could represent a conceptual opportunity to explore the applicability of the three indigenous entrepreneurship models presented in this study to the development of an indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystem approach.

Also, the results of this systematic literature review call into question the definition of indigenous entrepreneurship, adopted by the scientific community and mainstream academy, specifically that it is ‘the creation, management and development of new ventures by Indigenous peoples for the benefit of Indigenous peoples’ (Hindle & Lansdowne, Reference Hindle, Anderson, Giberson and Kayseas2005: 132). From a critical perspective of indigenous entrepreneurship, this definition is influenced by the Western paradigm of entrepreneurship that sees the creation of businesses as the successful expression of indigenous entrepreneurship. However, the results of this systematic review of literature and the analysis of these three proposed models of indigenous entrepreneurship demonstrates that this conception does not correspond to the full reality of indigenous entrepreneurship, specifically with respect to the remote and rural contexts studied. Indigenous entrepreneurship research is characterized by the complexity of indigenous peoples and the theoretical and methodological approaches used to analyze indigenous entrepreneurship processes, experiences, outcomes and opportunities.

CONCLUSION

The objective of this systematic review was to analyze and integrate the existing international literature on indigenous entrepreneurship in order to identify models of indigenous entrepreneurship that were contextualized. Three indigenous entrepreneurship models, namely urban, rural and remote, were proposed and illustrated through the relationship between the localization of the indigenous communities and indigenous peoples in relation to mainstream communities and the theoretical/methodological perspectives adopted in indigenous entrepreneurship research. The localization of indigenous peoples in urban, remote or rural contexts combined with the use of diverse theories and methodologies determined how the development and characteristics of indigenous businesses and entrepreneurial activities were interpreted and explained.

The results of this systematic review provide an integrative conceptual framework for the development of indigenous entrepreneurship research. So far, indigenous entrepreneurship has mainly been approached and analyzed as a phenomenon that is different than mainstream entrepreneurship, but also as a uniform phenomenon with its own ‘one-size-fits-all’ framework. The results of this systematic review contradict this assumption of indigenous entrepreneurship and demonstrate that indigenous entrepreneurship should not be analyzed as a homogeneous phenomenon. The complexity and the diversities of indigenous contexts, indigenous entrepreneurs and indigenous businesses should be further developed and considered in the research of typologies of indigenous entrepreneurship.

Beyond the intersocietal level of analysis, which relates to the fact that indigenous peoples represent a minority of the total population and share common challenges, the intrasocietal indigenous economic, structural and economic diversities among indigenous peoples must also be considered when developing indigenous entrepreneurship conceptual frameworks. The contextualized/localized classification of indigenous entrepreneurship models proposed in this article is one step in this direction. Moreover, the three indigenous entrepreneurship models proposed in this review show the constructed nature of entrepreneurship models, which varies on a continuum from indigenous entrepreneurship which reflects the formal enterprise from the point of view of the Western conception of entrepreneurship, to indigenous entrepreneurship which represents the traditional entrepreneurial activities related to indigenous cultures and ways of life. According to the three different localizations, indigenous entrepreneurship is analyzed from a Western assumption of entrepreneurship in relation to the modern market economy system instead of an indigenous assumption of entrepreneurship related to the traditional indigenous economic system.

Therefore, this systematic review’s main contribution to theory and practice is in bridging the fragmentation that currently exists in the indigenous entrepreneurship field. This is done through the proposal of a different classification of indigenous entrepreneurship models based on the contextualization and localization of the studies as urban, remote and rural. This classification needs to be explored further by developing conceptual dimensions and examining the applicability of these models in various indigenous communities and entrepreneurial endeavors. Moreover, depending on the different localizations of indigenous communities, such studies could focus on indigenous businesses and small enterprises or on indigenous entrepreneurial activities. A more sophisticated articulation of these activities needs to be further explored for the advancement of the field. Also, the importance of the localization of indigenous peoples and communities on the development of different indigenous entrepreneurial forms suggests that indigenous entrepreneurship should be further explored through the concept of indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems, including the notion of territoriality and resources available in urban, rural and remote contexts.

Concerning the practical contributions, the classification proposed may help policy-makers develop programs tailored more effectively to the contexts within which indigenous peoples live and function as indigenous entrepreneurs. Following the results of this systematic review, this is particularly relevant as access to finance is not the only effective measure for meeting the needs of all indigenous entrepreneurs. This is because, depending on the urban, rural and remote entrepreneurship models, indigenous entrepreneurial development needs can vary. For example, the governmental strategies adopted for indigenous peoples in urban contexts may not be effective for communities in rural or remote contexts because these communities conceive of and practice indigenous entrepreneurship differently.

The policies implemented therefore, must understand and acknowledge the authentic forms of indigenous entrepreneurship in various locations and indigenous contexts and examine the potential of certain assimilative policies. Therefore, contingent approaches for indigenous entrepreneurship development could be proposed on the bases of the localization and structure of the indigenous communities around the globe. Consideration must also be given to diversifying the programs and initiatives offered to the variety of indigenous entrepreneurs according to the three indigenous entrepreneurship models proposed in this study.

Regarding future research avenues, a broader systematic review of literature could be considered that includes academic literature on indigenous entrepreneurship that falls outside of mainstream ‘quality’ sources (i.e., ABDC ranking). This may provide a wider range of literature to explore and understand the conceptualization and practice of indigenous entrepreneurship in order to test the face validity and applicability of contextual classifications of indigenous entrepreneurship models proposed in this study. A qualitative meta-analysis could also be an important step to broadening the analysis according to the three models identified. Above all, what this study has confirmed is that it is important to contextually analyze indigenous entrepreneurship as an outcome of the relationship between indigenous peoples, indigenous cultures and the environments in which they live.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Professor Norrin Halilem, systematic review expert at Laval University for the comments provided on the systematic review process, and Normand Pelletier, specialist in documentary resources in business and entrepreneurship at the Laval University Library for the databases and keywords search string identification. The author sincerely thanks the reviewers for their comments, which contributed to the final version of the paper.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.69