Introduction

The competitive labor market and diverse employee demands have prompted organizations to use special strategies to recruit, retain, and motivate valued employees (Cappelli, Reference Cappelli2000). Idiosyncratic deals (i-deals) are voluntary and individualized agreements of a nonstandard nature negotiated between employees and their employers regarding employment conditions (Greenberg, Roberge, Ho, & Rousseau, Reference Greenberg, Roberge, Ho, Rousseau and Martocchio2004; Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2005; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). As a supplement to traditional standardized human resource management practice (Hornung, Rousseau, & Glaser, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2008), i-deals have garnered considerable scholarly attention (Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2001, Reference Rousseau2005).

I-deals are effective tools for boosting the recipient's job motivation and productivity (Bal, De Jong, Jansen, & Bakker, Reference Bal, De Jong, Jansen and Bakker2012). Specifically, previous studies have shown that i-deals are associated with positive work-related attitudes, including affective organizational commitment (Liu, Lee, Hui, Kwan, & Wu, Reference Liu, Lee, Hui, Kwan and Wu2013; Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2010), job satisfaction (Hornung, Glaser, & Rousseau, Reference Hornung, Glaser and Rousseau2010a; Rosen, Slater, Chang, & Johnson, Reference Rosen, Slater, Chang and Johnson2013), and work engagement (Hornung, Glaser, Rousseau, Angerer, & Weigl, Reference Hornung, Glaser, Rousseau, Angerer and Weigl2011; Hornung, Rousseau, Glaser, Angerer, & Weigl, Reference Hornung, Rousseau, Glaser, Angerer and Weigl2010b). Empirical studies have also demonstrated the positive relationships between i-deals and such work-related behaviors as voice (Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2015), helping behavior (Guerrero & Challiol-Jeanblanc, Reference Guerrero and Challiol-Jeanblanc2016), and job performance (Las Heras, Rofcanin, Matthijs Bal, & Stollberger, Reference Las Heras, Rofcanin, Matthijs Bal and Stollberger2017).

Although numerous previous studies have shown that i-deals can benefit the i-deals' recipients (for a review, see Liao, Wayne, & Rousseau, Reference Liao, Wayne and Rousseau2016), what is still less clear is how the recipients' coworkers respond to the i-deals. Because i-deals operate in an organizational context, they may have broader implications beyond the recipients, and coworker's role has long been recognized by i-deal researchers (Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Roberge, Ho, Rousseau and Martocchio2004). As an interested third party, coworkers are an important part of the triangle (i.e., employers, focal employees, and coworkers), which determines the ultimate effectiveness of i-deals (Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Roberge, Ho, Rousseau and Martocchio2004; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). However, thus far, empirical research on third-party implications of i-deals remains in its infancy, with only a few studies shedding light on this issue.

Lai and colleagues found that coworkers were willing to accept others' i-deals if the i-dealers were their close personal friends (Lai, Rousseau, & Chang, Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009). Studies found that coworkers who witnessed others' i-deals and yet received lower levels of i-deals than others were likely to feel envy or emotional exhaustion (Kong, Ho, & Garg, Reference Kong, Ho and Garg2020; Ng, Reference Ng2017). More recently, the results of a study showed that i-deals concerning a financial bonus would be considered more distributively unfair by coworkers than other i-deals concerning work-hour flexibility and workload reduction, and thus triggered coworkers' complaining (Marescaux, De Winne, & Sels, Reference Marescaux, De Winne and Sels2019). Taken together, these studies indicate that coworkers do engage in the comparison of i-deals with the recipients, and such comparison can cause coworkers' psychological and behavioral reactions.

Nevertheless, two important gaps remain to be filled. First, although some investigations we mentioned above have alluded to the existence of social comparison in the context of i-deals among coworkers, empirical study exploring coworkers' reactions toward focal employees' i-deals from this perspective is still scarce (Guerrero & Challiol-Jeanblanc, Reference Guerrero and Challiol-Jeanblanc2016). Second, coworkers' acceptance is one neutral and representative reaction that should be strived for (Marescaux, De Winne, & Sels, Reference Marescaux, De Winne and Sels2019), because i-deals' ultimate effectiveness can partly depend on coworkers' acceptance (Lai, Rousseau, & Chang, Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009). However, we know little about whether and how the contents of i-deals affect coworkers' acceptance behavior, even though relevant study has indicated that the contents of various types of i-deals can lead to different impacts on coworkers' perceptions and behaviors (Marescaux, De Winne, & Sels, Reference Marescaux, De Winne and Sels2019). Thus, to further advance our understanding of which type of focal employees' i-deals is more acceptable for coworkers, a deeper investigation is warranted.

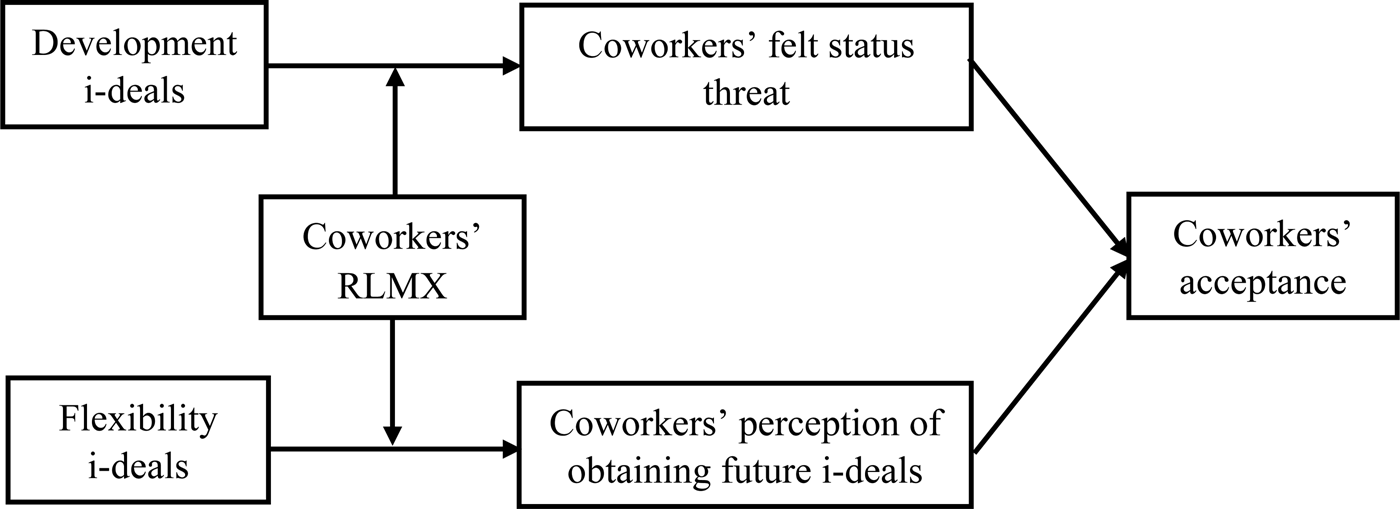

Our study tries to fill these gaps by using social comparison theory to explore how focal employees' different types of i-deals influence coworkers' perceptions and subsequent acceptance behavior. One common assumption in social comparison theory is upward comparison, or comparison with others who are better off, such as coworkers' comparison with i-deals recipients (Buunk & Mussweiler, Reference Buunk and Mussweiler2001; Collins, Reference Collins1996). Researchers have indicated that the effects of upward comparisons depend on whether employees contrast or assimilate themselves with the comparison targets (Mussweiler, Ruter, & Epstude, Reference Mussweiler, Ruter and Epstude2004). When individuals contrast themselves, upward comparison may threaten their self-identity and self- image (Collins, Reference Collins1996; Van der Zee, Buunk, Sanderman, Botke, & van den Bergh, Reference Van der Zee, Buunk, Sanderman, Botke and van den Bergh2000). Supporting this argument, existing studies have shown that upward comparison may trigger coworkers' adverse reactions, even social undermining behaviors, by inducing status threat (Marr & Thau, Reference Marr and Thau2014; Reh, Tröster, & Van Quaquebeke, Reference Reh, Tröster and Van Quaquebeke2018). When individuals assimilate themselves, upward comparison may entail individuals' assumption that they can attain a similarly attractive situation (Lockwood, Jordan, & Kunda, Reference Lockwood, Jordan and Kunda2002; Lockwood & Kunda, Reference Lockwood and Kunda1997). Consistent with this theorizing, upward comparison may also show coworkers the possibility of obtaining comparable future i-deals like focal employees received. Based on these rationales, we develop and test a model in which coworkers' felt status threat and coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals serve as mediators linking focal employees' development i-deals (i.e., individualized opportunities to develop working skills or career advancement) and flexibility i-deals (i.e., personal discretion over working hours or locations) to coworkers' acceptance.

Furthermore, given that the triangle consisting of focal employees, their coworkers, and their leaders determines the final effectiveness of i-deals in the organizations, and the i-deals are formally authorized by the leaders (Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Roberge, Ho, Rousseau and Martocchio2004; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006), we propose that the differentiation between coworkers' leader–member exchange (coworkers' LMX) and focal employees' leader–member exchange (focal employees' LMX) may constrain coworkers' perceptions and behaviors. Thus, we included coworkers' LMX relative to the LMXs of i-deals recipients (coworkers' RLMX) in our theoretical model as a moderator that may alter the extent of coworkers' reactions to the focal employees' i-deals.

Our study contributes to the literature in three specific ways. First, we contribute to i-deals literature by enriching our understanding of the influences of focal employees' i-deals on their coworkers. The majority of previous i-deals research studies were conducted to clarify the impacts of i-deals on focal employees' work attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Guerrero & Challiol-Jeanblanc, Reference Guerrero and Challiol-Jeanblanc2016; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Lee, Hui, Kwan and Wu2013; Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2010, Reference Ng and Feldman2015; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Slater, Chang and Johnson2013; Vidyarthi, Singh, Erdogan, Chaudhry, Posthuma, & Anand, Reference Vidyarthi, Singh, Erdogan, Chaudhry, Posthuma and Anand2016). However, the empirical investigation on the effects of focal employees' i-deals on their coworkers is still in its infancy (Marescaux, De Winne, & Sels, Reference Marescaux, De Winne and Sels2019). Given that i-deals are made in a larger social context, instead of a vacuum context (Kong, Ho, & Garg, Reference Kong, Ho and Garg2020), there is a pressing need to explore how and why coworkers respond to others' i-deals. Thus, we advance i-deals literature by investigating the interpersonal implications of i-deals for the coworkers' perceptions and behaviors.

Second, this study extends i-deals literature by exploring whether and why different types of i-deals differently affect coworkers' acceptance of others' i-deals. Existing studies have indicated that different i-deals have different impacts on the recipients (Hornung, Rousseau, & Glaser, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2008; Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2009; Hornung, Rousseau, Weigl, Müller, & Glaser, Reference Hornung, Rousseau, Weigl, Müller and Glaser2014). And recently, a study by Marescaux, De Winne, and Sels (Reference Marescaux, De Winne and Sels2019) showed that the contents of i-deals can also have different influences on the recipients' coworkers. Given that the acceptance is an important manifestation of coworkers' behavioral reactions toward others' i-deals and low levels of coworkers' acceptance may significantly reduce or even negate the i-deals' effectiveness (Lai, Rousseau, & Chang, Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009), it is necessary to further investigate the influences of the contents of i-deals on coworkers' acceptance behavior. Thus, we extend i-deals literature by integrating previous research to refine the understanding of which kind of focal employees' i-deals is more likely to be accepted by coworkers.

Third, our contribution pertains to our adding to the limited mediating mechanisms linking focal employees' i-deals to coworkers' reactions from the social comparison perspective. Thus far, i-deals literature is dominated by mediating mechanisms pertaining to social exchange theory (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Lee, Hui, Kwan and Wu2013; Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2015), for explaining why focal employees reciprocate (Anand, Vidyarthi, Liden, & Rousseau, Reference Anand, Vidyarthi, Liden and Rousseau2010; Huo, Luo, & Tam, Reference Huo, Luo and Tam2014). A handful of studies investigating coworkers' reactions to others' i-deals have been conducted from equity theory (Marescaux, De Winne, & Sels, Reference Marescaux, De Winne and Sels2019; Ng, Reference Ng2017) or conservation of resources theory (Kong, Ho, & Garg, Reference Kong, Ho and Garg2020). However, due to the within-group heterogeneity nature, i-deals can be subjected to social comparison process, which has strong implications for other group members. Therefore, extending beyond prior studies, we adopt a comparison perspective to examine whether upward comparison on i-deals can lead to coworkers' perceptions of status threat and obtaining comparable treatment, thus shape their acceptance behavior.

Theory and hypotheses

Idiosyncratic deals, social comparison, and coworkers' reactions

I-deals are special work arrangements and employment conditions that are negotiated between employees and their employers to satisfy both parties' needs and interests (Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2001, Reference Rousseau2005; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). The within-group heterogeneity nature of i-deals differentiates the recipients from other employees, who do similar work or who are in a similar position (Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2001). With regard to timing, scope, and content, i-deals take many forms in practice (Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). For example, i-deals can be made during the recruitment process (i.e., ex ante), or during the course of ongoing employment relationships (i.e., ex post). I-deals also vary in scope, ranging from a minor change to highly customized, from one element to an entire package. With respect to the content, several kinds of i-deals have been identified (Hornung, Rousseau, & Glaser, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2009; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Slater, Chang and Johnson2013; Rousseau & Kim, Reference Rousseau and Kim2006). Consistent with previous research (Hornung, Rousseau, & Glaser, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2008; Rousseau, Hornung, & Kim, Reference Rousseau, Hornung and Kim2009), we concentrate on development i-deals and flexibility i-deals due to their common occurrence in the organizations (Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2005).

Comparing the self with others, either consciously or unconsciously, is a pervasive social phenomenon (Buunk & Gibbons, Reference Buunk and Gibbons2007; Festinger, Reference Festinger1954; Suls, Martin, & Wheeler, Reference Suls, Martin and Wheeler2002; Wheeler & Miyake, Reference Wheeler and Miyake1992). Festinger (Reference Festinger1954) proposed that there exists an inherent drive in human organism to compare one's opinions and abilities to others in order to reduce uncertainty and make self-evaluation when objective standards are not available. Wood (Reference Wood1996) explicitly defined social comparison as ‘the process of thinking about information about one or more other people in relation to the self’ (pp. 520–521), which can influence individuals' attitudes and behaviors (Goodman & Haisley, Reference Goodman and Haisley2007; Greenberg, Ashton-James, & Ashkanasy, Reference Greenberg, Ashton-James and Ashkanasy2007; Wood, Reference Wood1989). Wood (Reference Wood1996) also identified multiple processes of social comparison, including acquiring, thinking about, and reacting to social information. From this respect, social comparison can satisfy individuals' internal drive to self-evaluate, and orient their social behaviors to protect or improve the selves (Buunk & Gibbons, Reference Buunk and Gibbons2007; Festinger, Reference Festinger1954).

Given the non-standard, individualized, and within-group heterogeneity natures of i-deals, coworkers are likely to engage in an upward comparison process by comparing with the i-dealers who received more special work terms than themselves (Kong, Ho, & Garg, Reference Kong, Ho and Garg2020). Research studies on social comparison theory have indicated that the effects of comparison may be subjected to whether individuals contrast or assimilate themselves with the comparison referents (Lam, Van der Vegt, Walter, & Huang, Reference Lam, Van der Vegt, Walter and Huang2011; Mussweiler, Ruter, & Epstude, Reference Mussweiler, Ruter and Epstude2004). Building on social comparison theory and i-deals research, we propose that comparison with focal employees' development i-deals may be more likely to trigger coworkers' contrast and status threat, while comparing with focal employees' flexibility i-deals may be more likely to evoke coworkers' assimilation and expectations of getting i-deals. Additionally, we propose coworkers' LMX relative to the i-dealers as an important boundary condition in the comparison process. Thus, based on upward comparison theory, we below argue how and why various i-deals contents and coworkers' RLMX influence coworkers' perceptions of status threat and obtaining future i-deals in different ways, thus subsequently shape their acceptance behavior. Figure 1 shows our conceptual model.

Fig. 1. Conceptual model.

Idiosyncratic deals and coworkers' acceptance

Coworkers' acceptance refers to coworkers' assent or approval to focal employees' i-deals (Lai, Rousseau, & Chang, Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009). It can ultimately affect the overall effectiveness of i-deals (Lai, Rousseau, & Chang, Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009; Marescaux, De Winne, & Sels, Reference Marescaux, De Winne and Sels2019). The overall effectiveness of i-deals for the organization not only lies in the recipients' reactions, but also in other coworkers' acceptance. As we mentioned, although i-deals can facilitate the recipients' organizational commitment or job performance (Liao, Wayne, & Rousseau, Reference Liao, Wayne and Rousseau2016), they may also trigger coworkers' negative behaviors, such as deviant behaviors (Kong, Ho, & Garg, Reference Kong, Ho and Garg2020), complaining (Marescaux, De Winne, & Sels, Reference Marescaux, De Winne and Sels2019), or even turnover (Ng, Reference Ng2017). In this study, drawing on social comparison theory, we propose that focal employees' development i-deals and flexibility i-deals may have different impacts on coworkers' acceptance.

According to social comparison theory, comparisons among employees are ubiquitous in the organizations (Festinger, Reference Festinger1954; Greenberg, Ashton-James, & Ashkanasy, Reference Greenberg, Ashton-James and Ashkanasy2007). Scholars have noted that individuals generally prefer to compare with others who are thought to be slightly better off (i.e., upward comparison), supporting Festinger's (Reference Festinger1954) notion of ‘upward drive’ (Buunk & Gibbons, Reference Buunk and Gibbons2007; Collins, Reference Collins1996). In the context of i-deals, coworkers' comparison of their own versus focal employees' i-deals may manifest as upward comparison, such that coworkers perceive themselves as receiving less than the focal employees (Guerrero & Challiol-Jeanblanc, Reference Guerrero and Challiol-Jeanblanc2016; Liao, Wayne, & Rousseau, Reference Liao, Wayne and Rousseau2016; Vidyarthi et al., Reference Vidyarthi, Singh, Erdogan, Chaudhry, Posthuma and Anand2016). Previous studies found that upward comparison may spark peers' perception of resource threat and subsequent social undermining (Campbell, Liao, Chuang, Zhou, & Dong, Reference Campbell, Liao, Chuang, Zhou and Dong2017; Reh, Tröster, & Van Quaquebeke, Reference Reh, Tröster and Van Quaquebeke2018).

We argue that coworkers are less willing to accept focal employees' development i-deals than flexibility i-deals. First, the resources involved in these two types of i-deals shape coworkers' different reactions. Specifically, development i-deals include the customized opportunities to develop working skills, enhance professional competencies, and meet personal career aspirations, which are essential for higher performance, greater occupational success, and larger space for promotion (Hornung, Rousseau, & Glaser, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2008, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2009; Hornung et al., Reference Hornung, Rousseau, Weigl, Müller and Glaser2014; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006; Rousseau & Kim, Reference Rousseau and Kim2006). In contrast, flexibility i-deals provide employees with discretion to personalize working schedules and working locations to better fit personal needs (Hornung, Rousseau, & Glaser, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2008, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2009; Hornung et al., Reference Hornung, Rousseau, Weigl, Müller and Glaser2014; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). Prior research studies have shown that flexibility i-deals cannot motive employees to work late or work engagement, and even may lower supervisor’ evaluation of the i-dealers' performance (Hornung, Rousseau, & Glaser, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2008, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2009; Hornung et al., Reference Hornung, Glaser, Rousseau, Angerer and Weigl2011; Liao, Wayne, & Rousseau, Reference Liao, Wayne and Rousseau2016; Rousseau, Hornung, & Kim, Reference Rousseau, Hornung and Kim2009). The competition for important resources may cause individuals' tendency to compare, thus leading to a variety of strong defensive responses (Festinger, Reference Festinger1954). Given that the resources included in development i-deals are more valuable than that in flexibility i-deals (Liao, Wayne, & Rousseau, Reference Liao, Wayne and Rousseau2016), others' development i-deals are more likely to induce coworkers' perceptions of relative deprivation (Buunk, Zurriaga, Gonzalez-Roma, & Subirats, Reference Buunk, Zurriaga, Gonzalez-Roma and Subirats2003) and low acceptance.

Second, individuals tend to compare the resource allocation when the resource is limited (Parks, Conlon, Ang, & Bontempo, Reference Parks, Conlon, Ang and Bontempo1999). Thus, given that development i-deals are generally viewed as a limited resource, while flexibility i-deals are not (Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006), coworkers are more sensitive to others' development i-deals than flexibility i-deals, and are more reluctant to accept the former. Providing support for this argument, relevant i-deals study also showed that when employees perceive others have more development i-deals, they would suffer a negative emotional experience and then present negative behavior (Kong, Ho, & Garg, Reference Kong, Ho and Garg2020). Based on the above analysis, we thus hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1 Coworkers are more likely to accept focal employees' flexibility i-deals than development i-deals.

The mediating role of coworkers' felt status threat

Social comparison theory indicated that upward comparisons have both their ‘ups and downs’ (Collins, Reference Collins1996; Mussweiler, Reference Mussweiler2003; Wood, Reference Wood1989). In other words, the effects of social comparison may depend on whether the individuals contrast or assimilate themselves with a comparison target (Mussweiler, Ruter, & Epstude, Reference Mussweiler, Ruter and Epstude2004). The direction of social comparison may be subject to a number of variables, and the one critical factor is whether the standard of the target is attainable or unattainable (Buunk, Collins, Taylor, VanYperen, & Dakof, Reference Buunk, Collins, Taylor, VanYperen and Dakof1990; Lockwood & Kunda, Reference Lockwood and Kunda1997). Mussweiler, Ruter, and Epstude (Reference Mussweiler, Ruter and Epstude2004) indicated that whether individuals ‘see themselves as farther away or closer to the standard’ could determine whether they chose assimilation or contrast. Assimilation effects arise if the standard is close, and contrast effects arise if the standard is hard or unable to reach (Lockwood & Kunda, Reference Lockwood and Kunda1997). In the context of i-deals, development i-deals are often offered as a reward to the employees who have better performance or make special contributions for the organizations (Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006), while flexibility i-deals are often provided for the employees who need to cope with personal difficulties or family crises (Hornung, Rousseau, & Glaser, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2009; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). From this respect, upward comparisons with others' development i-deals are more likely to cause contrast effect among coworkers than comparison with flexibility i-deals, as the standard of requesting development i-deals is harder to reach than flexibility i-deals. Based on this rationale, we argue that compared to flexibility i-deals, focal employees' development i-deals are more likely to trigger coworkers feeling of status threat.

First, social comparison theory indicates that the internal drive to compare with others allows individual to assess their relative position within groups (Buunk & Mussweiler, Reference Buunk and Mussweiler2001). Status threat is a subjective cognition of one's own status (Kellogg, Reference Kellogg2012; Zhang, Zhong, & Ozer, Reference Zhang, Zhong and Ozer2020). And individuals are sensitive to the signals about the status of their colleagues (Anderson, Hildreth, & Howland, Reference Anderson, Hildreth and Howland2015; Reh, Tröster, & Van Quaquebeke, Reference Reh, Tröster and Van Quaquebeke2018). As we mentioned above, flexibility i-deals are typically designed for addressing work–family or life issues (Las Heras et al., Reference Las Heras, Rofcanin, Matthijs Bal and Stollberger2017; Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2005; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006), and are intended to ‘retaining the services of a worker at a standard level of performance’ (Hornung, Rousseau, & Glaser, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2008: 657). To some extent, flexibility i-deals are need-based, which do not signal one's relative standing and status in the organization, and thus they are less likely to be the basis of contrast (Kong, Ho, & Garg, Reference Kong, Ho and Garg2020). However, development i-deals convey many strong signals about the i-dealers' higher status, such as supervisor's high value and trust, the recognition of the i-dealers' contribution, and the special status in supervisor's eyes (Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2005; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006; Vidyarthi et al., Reference Vidyarthi, Singh, Erdogan, Chaudhry, Posthuma and Anand2016). Therefore, development i-deals are particularly likely to be the basis of contrast, thus inducing coworkers' feeling of status threat (Brickman & Bulman, Reference Brickman, Bulman, Suls and Miller1977; Collins, Reference Collins1996; Wills, Reference Wills1981).

Second, because of the natural tendency to evaluate one's socially valued attributes, individuals may upwardly compare with others in the case of ability (Festinger, Reference Festinger1954). Development i-deals convey the signals about the leader's identification of the recipients' competence, and have been found to serve a competence-signaling function (Ho & Kong, Reference Ho and Kong2015). Hence, compared to flexibility i-deals, development i-deals are more likely to increase the odds of coworkers' perceiving status threat, especially because development i-deals concern higher working competence and greater working success (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Lee, Hui, Kwan and Wu2013; Ng, Reference Ng2017; Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2005), potentially putting coworkers in a disadvantaged position. Third, development i-deals are a relatively scarce and limited resource, which makes the upward comparison with such i-deals more salient than comparison with flexibility i-deals (Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). When the development i-deals are approved to the i-dealers, the availability of such i-deals for coworkers is reduced, which may further provoke coworkers' perceptions of status threat (Anderson, Hildreth, & Howland, Reference Anderson, Hildreth and Howland2015; Lind & Tyler, Reference Lind and Tyler1988; Tyler & Blader, Reference Tyler and Blader2000). We thus hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2a Coworkers view focal employees' development i-deals as more threatening to their status than flexibility i-deals.

According to social comparison theory, the self-evaluation about one's relative standing resulted from social comparison acts as a motivational force guiding their behaviors (Suls, Martin, & Wheeler, Reference Suls, Martin and Wheeler2002; Wood, Reference Wood1989). Hence, we argue that coworkers' perceptions of status threat caused by the upward comparison between their own versus others' development i-deals, may further lead to coworkers' unwillingness to accept these i-deals. Coworkers' acceptance of focal employees' i-deals means that coworkers assent to the privileges and the customized work arrangements that focal employees received from the supervisors (Lai, Rousseau, & Chang, Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009). Coworkers' acceptance can affect the final effectiveness of focal employees' i-deals, and low acceptance may reduce coworkers' respect for the i-deal's principals (i.e., the supervisors) or even erode the cooperation between the subordinates and the supervisors (Lai, Rousseau, & Chang, Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009).

First, the desire for status is a fundamental human motive, and individuals tend to pursue high status and seek to avoid losing their status (Anderson, Hildreth, & Howland, Reference Anderson, Hildreth and Howland2015). As the status is important to one's self-identification, individuals are sensitive to the information signaling the risk of losing status (Koski, Xie, & Olson, Reference Koski, Xie and Olson2015). And individuals may exhibit strong defensive responses once they face the risk of losing status (Anderson, Hildreth, & Howland, Reference Anderson, Hildreth and Howland2015). Prior research studies have indicated that status threat may lead to negative consequences, such as envy and unfriendly behaviors (Kemper, Reference Kemper1991; Marr & Thau, Reference Marr and Thau2014; Reh, Tröster, & Van Quaquebeke, Reference Reh, Tröster and Van Quaquebeke2018). Therefore, we speculate that as a result of comparison with others' development i-deals, coworkers' feeling of status threat may cause their unacceptance of focal employees' i-deals.

Second, social comparison theory indicates that when individuals contrast themselves, upward comparison may threaten one's self-image and then lead to one's negative reactions toward the comparison target (Buunk & Gibbons, Reference Buunk and Gibbons2007; Collins, Reference Collins1996; Mussweiler & Strack, Reference Mussweiler and Strack2000). A considerable body of empirical research has indicated that employees may respond negatively when confronted with someone who are better off. For example, comparison with the targets who do better in daily work may lead to individuals' negative psychological states, and subsequent interpersonal harming behavior (Lam et al., Reference Lam, Van der Vegt, Walter and Huang2011), incivility (Koopman, Lin, Lennard, Matta, & Johnson, Reference Koopman, Lin, Lennard, Matta and Johnson2020), or ostracism on the comparison targets (Ng, Reference Ng2017). From this respect, unacceptance of others' development i-deals may be a social strategy that coworkers use to cope with the threats to their status and the discomfort resulted from such i-deals. We thus hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2b Coworkers' felt status threat mediates the negative relationship between development i-deals and coworkers' acceptance.

The mediating role of coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals

Social comparison theory also indicates that when individuals assimilate themselves with the comparison targets, upward comparison may increase their assumptions that they can attain the similarly attractive situation (Collins, Reference Collins1996; Lockwood, Reference Lockwood2002; Lockwood, Jordan, & Kunda, Reference Lockwood, Jordan and Kunda2002; Lockwood & Kunda, Reference Lockwood and Kunda1997; Van der Zee et al., Reference Van der Zee, Buunk, Sanderman, Botke and van den Bergh2000). As noted above, assimilation effect seems more likely if the standard and the target are attainable or close to reach (Buunk et al., Reference Buunk, Collins, Taylor, VanYperen and Dakof1990; Lockwood & Kunda, Reference Lockwood and Kunda1997; Mussweiler, Ruter, & Epstude, Reference Mussweiler, Ruter and Epstude2004). Thus, in the context of i-deals, upward comparisons with others' flexibility i-deals are more likely to cause assimilation effects among coworkers than development i-deals, because flexibility i-deals seems easier to obtain than development i-deals. Based on this rationale, we propose that compared to development i-deals, focal employees' flexibility i-deals are more likely to cause coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals.

Coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals refers to coworkers' belief that they will have opportunities for individualized work arrangements in the future that are comparable with that of the focal employees received (Lai, Rousseau, & Chang, Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). Opportunities for obtaining similar customized treatment do not mean that coworkers believe they deserve or need them at present (Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). Rather, coworkers believe that in the future, they can successfully negotiate i-deals with their supervisors that are similar with the focal employees' i-deals (Huo, Luo, & Tam, Reference Huo, Luo and Tam2014; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). As we previously mentioned, flexibility i-deals are granted to employees who need to cope with work–family or life issues, while development i-deals are generally awarded to high performers (Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2005; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). Flexibility i-deals seems more feasible and available for coworkers as negotiating development i-deals require higher performance, professional skills, or outstanding contributions to the organizations. From this respect, compared to development i-deals, comparison with focal employees' flexibility i-deals may be more likely to be the basis of upward assimilation, thus boosting coworkers' confidence in attaining the similar i-deals as the i-dealers gained. We thus hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3a Focal employees' flexibility i-deals increase coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals more than development i-deals.

Coworkers are in turn expected to behave in a way that is consistent with their perceptions activated by upward comparison with others' flexibility i-deals. This is because coworkers' self-perception derived from social comparisons may further shape their behavior (Wood, Reference Wood1989, Reference Wood1996). By comparing their own treatment with that of focal employees, coworkers adjust their behaviors according to the consequence of comparison to maximize the sense of consistency with their self-perception (Spence, Ferris, Brown, & Heller, Reference Spence, Ferris, Brown and Heller2011). Specifically, we argue that coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals may be positively related to their acceptance of focal employees' i-deals.

First, obtaining future i-deals means the equal opportunities for coworkers to negotiate and request i-deals, which may lower coworkers' perception of unfairness to some extent (Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Roberge, Ho, Rousseau and Martocchio2004). In other words, when coworkers believe they have comparable opportunities to obtain customized arrangements, they may perceive others' i-deals as fair and acceptable (Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). Second, coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals implies that coworkers may get comparable i-deals from supervisors (Huo, Luo, & Tam, Reference Huo, Luo and Tam2014; Lai, Rousseau, & Chang, Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). With such expectation, coworkers may support focal employees' i-deals (Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006). And the belief that they can benefit from these i-deals may improve coworkers' acceptance (Bal & Rousseau, Reference Bal and Rousseau2015; Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Roberge, Ho, Rousseau and Martocchio2004). Besides, previous empirical studies have provided some evidence for supporting this hypothesis. For example, Lai, Rousseau, and Chang (Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009) indicated that coworkers' beliefs regarding the likelihood of comparable future opportunity have a positive effect on their acceptance of others' i-deals. The study of Huo, Luo, and Tam (Reference Huo, Luo and Tam2014) also shown that coworkers' beliefs about obtaining future i-deals can increase coworkers' citizenship behaviors for the recipients. Therefore, compared to development i-deals, upward comparison with focal employees' flexibility i-deals seems more likely to cause assimilation effects among coworkers, which may increase coworkers' beliefs in obtaining similar i-deals in the future and promote coworkers' acceptance of others' i-deals. We thus hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3b Coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals mediates the positive relationship between flexibility i-deals and coworkers' acceptance.

The moderating role of coworkers' relative leader–member exchange

LMX is a dyadic approach to understanding the relationship between an immediate supervisor and a subordinate (Bauer & Green, Reference Bauer and Green1996; Graen & Scandura, Reference Graen, Scandura, Staw and Cummings1987). These dyadic relationships are built through a series of exchanges and interpersonal interactions (Bauer & Green, Reference Bauer and Green1996; Graen & Cashman, Reference Graen, Cashman, Hunt and Larson1975). As the limited time and resources that the parties invest in the relationship-building process are different, the members' exchange relationships with leader in a group are distinct from each other (Green, Anderson, & Shivers, Reference Green, Anderson and Shivers1996; Liden & Graen, Reference Liden and Graen1980; Wayne, Shore, & Liden, Reference Wayne, Shore and Liden1997). In other words, leaders do not treat all subordinates in the same way, but build different types of exchange relationship with each group member (Graen & Cashman, Reference Graen, Cashman, Hunt and Larson1975; Graen, Novak, & Sommerkamp, Reference Graen, Novak and Sommerkamp1982). According to social comparison theory, individuals may observe, learn, and compare their own LMX relationships with their teammates' LMX relationships (Hu & Liden, Reference Hu and Liden2013). Previous studies have shown that a focal individual's LMX relative to the LMXs of other coworkers (relative LMX, or RLMX) can influence individual's attitudes and behaviors (Henderson, Wayne, Shore, Bommer, & Tetrick, Reference Henderson, Wayne, Shore, Bommer and Tetrick2008; Hu & Liden, Reference Hu and Liden2013; Tse, Ashkanasy, & Dasborough, Reference Tse, Ashkanasy and Dasborough2012; Vidyarthi, Liden, Anand, Erdogan, & Ghosh, Reference Vidyarthi, Liden, Anand, Erdogan and Ghosh2010).

Given the triangle of relationships outlined by focal employees, leaders, and coworkers in the i-deals context, we propose that coworkers' LMX relative to the focal employees' LMX may play an important role in the relationships between focal employees' i-deals and coworkers' reactions. Specifically, we argue that coworkers' RLMX may weaken the relationship between focal employees' development i-deals and coworkers' felt status threat. First, employees with high RLMX have greater possibility to get access to the resources and reward from their managers relative to those with low RLMX (Vidyarthi et al., Reference Vidyarthi, Liden, Anand, Erdogan and Ghosh2010). Therefore, when focal employees receive customized work arrangements, high RLMX can reduce the influence of i-deals on coworkers' status threat. Second, with high RLMX, individual members tend to feel psychologically close to their leaders (Hu & Liden, Reference Hu and Liden2013). That is, coworkers with high RLMX may feel confident in their ability to successfully negotiate special treatment from their supervisors. This perception may effectively diminish coworkers' status threat resulted from the comparison with focal employees' i-deals. Third, research has indicated that if a member's RLMX is high, he or she may have a positive self-concept, and high RLMX can increase individuals' evaluation of their own self-efficacy and self- identification (Tse, Ashkanasy, & Dasborough, Reference Tse, Ashkanasy and Dasborough2012). Furthermore, coworkers with high RLMX may keep close and frequent communications with their leaders (Dienesch & Liden, Reference Dienesch and Liden1986). This high-quality communication can effectively eliminate coworkers' negative feelings resulted from that they do not obtained the expected i-deals. Additionally, their leaders may make strong promise to the coworkers that they will get the same chance as the focal employees' in the near future if they are qualified, which is likely to lower coworkers' status threat. Hence, for the coworkers with high RLMX, the effect of focal employees' development i-deals on status threat is weaker than those with low RLMX. We thus hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4a Coworkers' RLMX may weaken the positive effect of development i-deals on coworkers' felt threat status.

In addition, we expect that coworkers' RLMX can strengthen the relationship between focal employees' flexibility i-deals and coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals. First, subordinates with high RLMX tend to actively negotiate their job roles or duties with their leaders (Graen & Scandura, Reference Graen, Scandura, Staw and Cummings1987). Coworkers with high RLMX may have more special privileges, opportunities, and intrinsic motivations to negotiate discretion over their work arrangements with the leaders (Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006; Wang, Law, Hackett, Wang, & Chen, Reference Wang, Law, Hackett, Wang and Chen2005). Consequently, the positive influence of flexibility i-deals on the perception of obtaining future i-deals may be stronger for coworkers with high RLMX than those with low RLMX.

Second, given that members with high RLMX tend to evaluate themselves more highly than those with low RLMX (Tse, Ashkanasy, & Dasborough, Reference Tse, Ashkanasy and Dasborough2012), this function of high RLMX that can improve individual's self-concept may further strengthen the relationship between the focal employees' flexibility i-deals and coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals. We thus hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4b Coworkers' RLMX may strengthen the positive effect of flexibility i-deals on coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals.

Moderated mediation

Furthermore, we argue that coworkers' RLMX can moderate the indirect effects of different type of i-deals on coworkers' acceptance of others' i-deals via coworkers' perceptions. As we have stated above, members with high RLMX may be more likely to access resources and have more opportunities to negotiate i-deals with supervisors, and these characteristics of high RLMX may alter coworkers' reactions toward focal employees' i-deals. Specifically, different levels of coworkers' RLMX is related to how they evaluate themselves, and the levels of self-perception can weaken or strengthen the influences of focal employees' i-deals on coworkers' acceptance behavior. Following on the preceding discussion regarding hypotheses 2, 3, 4, we contend that, for coworkers with high RLMX, the indirect effect of development i-deals on coworkers' acceptance via coworkers' felt status will be weaker, and the indirect effect of flexibility i-deals on coworkers' acceptance via coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals will be stronger. In contrast, for coworkers with low RLMX, the indirect effect of development i-deals on coworkers' acceptance via coworkers' felt status will be stronger, and the indirect effect of flexibility i-deals on coworkers' acceptance via coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals will be weaker. We thus hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 5a The indirect effect of development i-deals on coworkers' acceptance, via coworker’ felt threat status, is moderated by coworkers' RLMX, such that this effect is weaker when coworkers' RLMX is high, but stronger when coworkers' RLMX is low.

Hypothesis 5b The indirect effect of flexibility i-deals on coworkers' acceptance, via coworker’ perception of obtaining future i-deals, is moderated by coworkers' RLMX, such that this effect is stronger when coworkers' LMX is high, but weaker when coworkers' LMX is low.

Method

Sample and procedure

The participants in this study were from a large Internet company in China. Before we started our research in this company, we interviewed 13 supervisors and 20 employees. The interviews demonstrated that this company was appropriate to conduct our surveys because its employees had discretion over their working hours and career development. We conducted a large-scale survey after obtaining permission from the CEO of the company. Two members with similar work background and responsibilities in each working group were chosen by the human resource (HR) department to create a focal employee–coworker pair, as they can observe the other's customized work arrangements easily. And we used a four-digit code to match each of them.

Participants were invited into a conference room, and sit separately. We distributed pens, printed surveys, and gift incentives, and introduced the purpose and procedures of the survey. All participants were assured that their responses would remain confidential, and only be used for research purposes. After completing the questionnaires, the participants put them in sealed envelopes and handed the envelopes to the researchers. Participants received an extra bonus in exchange for completing all surveys.

To reduce potential common method bias, we collected three waves of data. The time lag between each survey was 1 month. At time 1, focal employees reported their LMX. Meanwhile, coworkers reported their observation of focal employees' i-deals, completed the measures of their LMX and other control variables. At time 2, we asked coworkers to report the variables of felt status threat and perception of obtaining future i-deals. At time 3, coworkers reported their willingness to accept others' i-deals.

In wave 1, we distributed 473 focal employee questionnaires, and received 288 completed questionnaires. At the same time, we distributed 473 coworker questionnaires, and received 412 completed forms. In wave 2, we distributed questionnaires to these 412 coworkers who had submitted valid questionnaires in wave 1, and 325 returned completed questionnaires. In wave 3, coworker questionnaires were distributed to these 325 participants, and received 255 valid questionnaires. At the completion of the three waves’ data-collection procedure, we got 253 focal employee–coworker pairs of valid data by matching the four-digit code (53.49% of the initial sample).

Overall, 49% of the participants were male, and the average age of participants was 31.71. Their average organizational tenure was 7.13 years. In terms of education, 13.83% held less than a bachelor's degree. With regard to the position, 28.06% were in management positions.

Measures

Since all the measures were originally constructed in English, we used the back-translation method to translate all the items. We recruited two PhD candidates to translate the items into Chinese and then translated them back into English (Brislin, Reference Brislin, Triandis and Berry1980). All items were measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree or not at all) to 7 (completely agree or to a very great extent).

Idiosyncratic deals

We used the scales developed by Rousseau and Kim (Reference Rousseau and Kim2006) to measure development i-deals and flexibility i-deals. Development i-deals were assessed using a four-item scale (α = .96). A sample item is, ‘to what extent have your colleague A asked for and successfully negotiated for training opportunities?’ Flexibility i-deals were assessed using a two-item scale (α = .94). A sample item is, ‘to what extent have your colleague A asked for and successfully negotiated for flexibility on starting and ending the workday?’

Coworkers' felt status threat

We adapted a four-item scale from Zhang, Zhong, and Ozer (Reference Zhang, Zhong and Ozer2020) to assess the degree of coworkers' feelings of status threat within the group. A sample item is, ‘I have felt some colleagues colluded to challenge my status in the team’ (α = .95).

Coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals

Coworkers reported their perception of the possibility of obtaining future i-deals using a two-item scale from Lai, Rousseau, and Chang (Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009). A sample item is, ‘I can have the same special individual arrangements as my coworkers if I ask’ (α = .94).

Coworkers' acceptance

Coworkers' acceptance of others' i-deals was assessed using the item from Lai, Rousseau, and Chang (Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009): ‘If your colleagues ask for special individual arrangements in the near future, to what extent would you be willing to accept them having arrangements different from your own?’

RLMX

RLMX was obtained from coworkers' LMX, which was measure by using Scandura and Graen's (Reference Scandura and Graen1984) seven-item scale (α = .95). A sample item is, ‘How well do you feel that your immediate supervisor understands your problems and needs?’ Differing from prior studies, we adapted the operationalization of RLMX on the basis of the studies of Henderson et al. (Reference Henderson, Wayne, Shore, Bommer and Tetrick2008) and Tse, Ashkanasy, and Dasborough (Reference Tse, Ashkanasy and Dasborough2012), which calculate RLMX by subtracting the mean LMX within the team from the LMX of focal employee. With a slightly different method, we subtracted the score of a focal employee's LMX from a coworker's LMX score. This is because our study confined RLMX within a focal employee–coworker pair and we focused on the LMX difference at the individual–individual level.

Control variables

Previous research has suggested that coworkers' reactions to others' i-deals can be influenced by the personal relationship between the coworker and the i-dealer (Lai, Rousseau, & Chang, Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009). Thus, we included coworkers' team member exchange (coworkers' TMX) as a control variable, using a six-item scale from Sherony and Green (Reference Sherony and Green2002) to measure the exchange relationships among coworkers who report to the same supervisor (α = .92). A sample item is, ‘How well do you feel that your colleagues understand your problems and needs?’ Besides, given that focal employees' LMX has been found to be associated with leaders' authorization of i-deals, thus we also set focal employees' LMX as a control variable. We measured focal employees' LMX (α = .95) using the scale developed by Scandura and Graen (Reference Scandura and Graen1984). In addition, according to present studies (Lai, Rousseau, & Chang, Reference Lai, Rousseau and Chang2009; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Lee, Hui, Kwan and Wu2013), we controlled for employee demographics, including age, gender, education, organizational tenure, and position.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

We analyzed the data using Mplus 7. Before testing our hypotheses, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate the discriminant validity of the key variables in our model (focal employees' development i-deals, flexibility i-deals, coworkers' LMX, focal employees' LMX, coworkers' felt status threat, and coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals). As shown in Table 1, the proposed six-factor model showed a good overall measurement fit with χ2/df = 1.169, comparative fit index (CFI) = .993, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = .991, and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .026. We also tested five alternative models to assess discriminant validity. The fit indices in Table 1 show that the proposed six-factor model fits the data better than any of the alternative models. The means, standard deviations, and correlations of all key variables are given in Table 2.

Table 1. Confirmatory factor analysis

DI, development i-deals; FI, flexibility i-deals; TS, coworkers' felt status threat; OF, coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals; CLMX, coworkers' LMX; FLMX, focal employees' LMX.

Note: Six-factor model = DI, FI, TS, OF, FLMX, and CLMX; five-factor model = DI + FI, TS, OF, CLMX, and FLMX; four-factor model = DI + FI + CLMX, TS, OF, and FLMX; three-factor model = DI + FI + CLMX + FLMX, TS, and OF; two-factor model = DI + FI + CLMX + FLMX, and TS + OF; one-factor model = DI + FI + CLMX + FLMX + TS + OF.

Table 2. Mean, standard deviation, and correlations of variables

TMX, team member exchange; LMX, leader member exchange.

Note: N = 253.

Gender: 1 = male, 2 = female; Education: 1 = above bachelor's degree, 2 = bachelor's degree, and 3 = below bachelor's degree; Position: 1 = non-management and 2 = management.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Hypothesis testing

We used structural equation model to test all the hypotheses except for moderating effects. Figure 2 shows the standardized path estimates for this model. Coworkers' gender, age, educational level, tenure, position, TMX, and focal employees' LMX were included in the model as control variables. Hypothesis 1 proposed that coworkers are more likely to accept focal employees' flexibility i-deals than development i-deals. The results show that development i-deals have a negative effect on coworkers' acceptance (b = −.155, p < .001), meanwhile flexibility i-deals have a positive effect on coworkers' acceptance (b = .197, p < .01). Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported.

Fig. 2. Hypothesized structural model. Solid lines represent paths that were significant and dashed lines represent paths that were nonsignificant. Numbers are standardized estimates. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Hypothesis 2a proposed that coworkers view focal employees' development i-deals as more threatening to their status than flexibility i-deals. The results indicate that focal employees' development i-deals have a positive effect on coworkers' felt status threat (b = .282, p < .01), while flexibility have no significant effect on coworkers' felt status threat (b = .106, n.s.). Therefore, hypothesis 2a was supported. Hypothesis 3a proposed that focal employees' flexibility i-deals increase coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals more than development i-deals. The results indicate that flexibility i-deals have a positive effect on coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals (b = .446, p < .001), while development i-deals have no significant effect on coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals (b = −.051, n.s.). Hence, hypothesis 3a was supported.

We conducted further bootstrapping analyses to test the mediating effects. Hypothesis 2b predicted the mediating role of coworkers' felt status threat in the relationship between focal employees' development i-deals and coworkers' acceptance, and hypothesis 3b predicted the mediating role of coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals in the relationship between flexibility i-deals and coworkers' acceptance. Table 3 lists the estimates of stage I effects (independent variable [IV] → mediator [Me]), stage II effects (Me → dependent variable [DV]), and indirect effects (IV → Me → DV). As hypothesized, coworkers' felt status threat exerted significant mediation effects on the relationship between development i-deals and coworkers' acceptance (indirect effect = −.035, 95% CI = [−.073, −.016]), and coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals exerted significant mediation effects on the relationship between flexibility i-deals and coworkers' acceptance (indirect effect = .106, 95% CI = [.041, .199]). Thus, hypotheses 2b and 3b were supported.

Table 3. Bootstrapping results for mediation tests

Note: N = 253. The square brackets show 95% confidence intervals.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

In addition, we tested how coworkers' RLMX moderates the effects of development i-deals on coworkers' felt status threat and flexibility i-deals on coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals by conducting bootstrapping analyses. Hypothesis 4a predicted that coworkers' RLMX may weaken the positive effect of development i-deals on coworkers' felt status threat. The results in Table 4 show that the interaction effect of coworkers' RLMX and development i-deals on coworkers' felt status threat was significant with a coefficient of −.112 (SE = .042, p < .01). The coefficient of the effect of development i-deals on coworkers' felt status threat was .496 (SE = .126, p < .001) when RLMX was low, and .271 (SE = .104, p < .01) when RLMX was high (see Figure 3). Thus, hypothesis 4a was supported.

Table 4. Moderating effects of coworkers' RLMX

Note: N = 253.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Fig. 3. The interactive effect of development i-deals and coworkers' RLMX on coworkers' felt status threat.

Hypothesis 4b predicted that coworkers' RLMX may strengthen the positive effect of flexibility i-deals on coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals. The results in Table 4 show that the interaction effect of coworkers' RLMX and flexibility i-deals on coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals was significant (p < .01), with a coefficient of .086 (SE = .033). The effect of flexibility i-deals on coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals was .297 (SE = .114, p < .01) when RLMX was low, and .470 (SE = .112, p < .001) when RLMX was high (see Figure 4). Thus, hypothesis 4b was supported.

Fig. 4. The interactive effect of flexibility i-deals and coworkers' RLMX on coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals.

Furthermore, we examined the moderating role of coworkers' RLMX on the mediating effects of coworker’ felt threat status and coworker’ perception of obtaining future i-deals by conducting further bootstrapping analyses. Hypothesis 5a predicted that coworkers' RLMX may weaken the indirect effect of development i-deals on coworkers' acceptance via coworker’ felt threat status, and hypothesis 5b predicted that coworkers' RLMX may strengthen the indirect effect of flexibility i-deals on coworkers' acceptance via coworker’ perception of obtaining future i-deals. As shown in Table 5, the mediating effect of coworker’ felt status threat was moderated by coworkers' RLMX (difference = .021, 95% CI = [.003, .043]), in support hypothesis 5a. Similarly, the mediating effect of coworker’ perception of obtaining future i-deals was also moderated by coworkers' RLMX (difference = .038, 95% CI = [.007, .089]), supporting hypothesis 5b.

Table 5. Indirect effect comparison between high- and low-RLMX employees

Note: N = 253. The square brackets show 95% confidence intervals.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Discussion

Based on social comparison theory, we advanced and examined a model that explained how focal employees' i-deals influence coworkers' acceptance of these i-deals. We found that coworkers are more likely to accept focal employees' flexibility i-deals than development i-deals. More specifically, coworkers viewed focal employees' development i-deals as more threatening to their status than flexibility i-deals. Coworkers' felt status threat mediates the negative relationship between development i-deals and coworkers' acceptance. In addition, focal employees' flexibility i-deals can increase coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals more than development i-deals. This perception mediates the positive relationship between flexibility i-deals and coworkers' acceptance. Furthermore, we also examined the moderating role of coworkers' RLMX. The results show that coworkers' RLMX weakens the indirect effect of focal employees' development i-deals on coworkers' acceptance, through coworkers' feeling of status threat, and strengthens the indirect effect of focal employees' flexibility i-deals on coworkers' acceptance, through coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals.

Theoretical implications

Our research makes three theoretical contributions to the literature. First, this study enriches i-deals literature by examining the effects of i-deals from coworkers' perspective. Previous studies on i-deals mostly focus on how i-deals exercise an influence on the attitudinal and behavioral outcomes from the recipients' perspective. However, according to Rousseau and her colleagues (Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2005; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006), an i-deal's final effectiveness is decided by a triangle of relationships including focal employees, their supervisors, and their coworkers. And Greenberg et al. (Reference Greenberg, Roberge, Ho, Rousseau and Martocchio2004) indicated that focal employees' i-deals can elicit coworkers' responses because of the within-group heterogeneity of i-deals. Therefore, in order to fully understand the influences of i-deals, we need to consider coworkers' psychological and behavioral reactions to focal employees' i-deals. In fact, some scholars (Las Heras et al., Reference Las Heras, Rofcanin, Matthijs Bal and Stollberger2017; Ng & Lucianetti, Reference Ng and Lucianetti2016; Vidyarthi et al., Reference Vidyarthi, Singh, Erdogan, Chaudhry, Posthuma and Anand2016) have called for relevant i-deals studies to take account of coworkers and explore the efficacy of focal employees' i-deals from coworkers' perspective.

The second theoretical implication relates to our focus on how and why different types of i-deals influence coworkers' acceptance differently, refining our understanding of coworkers' i-deals acceptance. Existing research has indicated that the effects of different i-deals on focal employees are distinct (Hornung, Rousseau, & Glaser, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2008, Reference Hornung, Rousseau and Glaser2009; Hornung et al., Reference Hornung, Rousseau, Weigl, Müller and Glaser2014; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Slater, Chang and Johnson2013). For example, flexible working hours can reduce the conflict between work and private life, while training opportunities can promote working skills. Recently, the results of a study by Marescaux, De Winne, and Sels (Reference Marescaux, De Winne and Sels2019) also showed that focal employees' different types of i-deals have different effects on coworkers' perceptions and behaviors. With those in mind, we integrated past research and examined whether and how focal employees' development i-deals and flexibility i-deals impact coworkers' self-perceptions and acceptance behaviors differently. Thus, this study contributes to the literature by refining which type of focal employees' i-deals is more acceptable for coworkers.

Finally, this study extends i-deals literature by testing a theoretical model based on social comparison theory. In previous research, i-deals have been studied using the reciprocity mechanism based on social exchange theory (Anand et al., Reference Anand, Vidyarthi, Liden and Rousseau2010; Rousseau, Ho, & Greenberg, Reference Rousseau, Ho and Greenberg2006), the motivator of pursuit of equity (Marescaux, De Winne, & Sels, Reference Marescaux, De Winne and Sels2019; Ng, Reference Ng2017), or the role of resources (Kong, Ho, & Garg, Reference Kong, Ho and Garg2020). Many scholars have called for more research to drill down into the mechanisms through which i-deals have an impact on outcomes from different the theoretical perspectives (Bal & Rousseau, Reference Bal and Rousseau2015; Liao, Wayne, & Rousseau, Reference Liao, Wayne and Rousseau2016). According to social comparison theory, coworkers will naturally compare their own working conditions with focal employees' i-deals. Thus, we respond to the call of Guerrero and Challiol-Jeanblanc (Reference Guerrero and Challiol-Jeanblanc2016) by developing a theoretical framework that explains how social comparison shapes coworkers' reactions to others' i-deals.

Practical implications

This study has provided insights for both managers and employees. First, this study explores an issue concerning i-deals that managers usually overlook: even though i-deals might benefit focal employees, what are their coworkers' hidden psychological consequences of observing their i-deals. We gathered evidence that focal employees' flexibility i-deals are more acceptable for coworkers than development i-deals. Our finding can help managers understand the influence of i-deals in depth by suggesting that focal employees do not exist in a vacuum, and the coworkers will inevitably compare their own treatment with that of focal employees. Thus, managers need to perform a balanced analysis of costs and benefits, then make a very deliberate decision when granting i-deals.

Second, this study indicates that focal employees' development i-deals might cause coworkers' feeling of status threat and backlash, thus lead to coworkers' unwillingness to accept others' i-deals. It is crucial for supervisors to manage i-deals properly to make full use of its effectiveness and avoid its potential side effects. Therefore, managers can build high-quality relationships with subordinates by providing organizational support and developing mutual trust. Besides, it will be useful to set up an official channel for communication, which is expected to create a context of justice and fairness. Through this channel, managers negotiate i-deals with employees and disclose information about those i-deals. In addition, our finding also suggests that focal employees' flexibility i-deals may cause coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals, which is positively related to coworkers' acceptance. Thus, it will be helpful that managers make credible assurances of providing comparable opportunities for i-deals when coworkers need in order to minimize their backlash.

Third, this study revealed coworkers' potential psychological reactions when they observed focal employees' i-deals. Focal employees should realize that their customized work arrangement might have an adverse effect on their coworkers. And given that they play a crucial role in communicating with coworkers, focal employees could make efforts to dispel coworkers' perception of unfairness or feeling of status threat resulted from the i-deals. For example, the recipients can actively build and maintain a good relationship with their coworkers to improve coworkers' willingness to accept their i-deals. Besides, providing some support, showing helping behavior or organizational citizenship behavior, and sharing useful information may be effective on increase coworkers' approval.

Limitations and future research

Our study may have several potential limitations. First, based on social comparison theory, we proposed that upward comparison with focal employees' development i-deals may cause coworkers' felt status threat and lower their willingness to accept others' i-deals. However, upward comparison sometimes may also serve a self-enhancement function (Buunk & Gibbons, Reference Buunk and Gibbons2007; Collins, Reference Collins1996). That is, upward comparison with focal employees' i-deals may provide motivation for coworkers to improve themselves to pursue such development i-deals. However, whether the self-enhancement motivation can facilitate coworkers' acceptance of others' i-deals is an interesting issue needed to explore. Research has indicated that when coworkers believe they can benefit from others' i-deals, they may be willing to approve such i-deals (Bal & Rousseau, Reference Bal and Rousseau2015; Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Roberge, Ho, Rousseau and Martocchio2004). Therefore, future research is encouraged to adopt the self-improvement function of social comparison theory to explore the influence of focal employees' i-deals on coworkers' self-enhancement motive and perception of benefit, and further on coworkers' acceptance behavior.

Second, we argued that coworkers' LMX relative to the focal employees' LMX may play a moderating role in the relationships between focal employees' i-deals and coworkers' reactions. Indeed, the results of our study also support our arguments. However, we neglected that even though high RLMX are characterized by more opportunities to negotiate i-deals and higher resources, whether coworkers with high RLMX may feel being betrayed by their leaders and feel their leaders as unfair when they observe focal employees' i-deals. And how this psychological letdown affects the coworkers' perceptions and behaviors toward their leaders need further study and exploration.

Third, based on social comparison theory, our study introduced coworkers' felt status threat and perception of obtaining future i-deals as the theoretically driven mediators of the relationships between focal employees' i-deals and coworkers' acceptance. There may exist other mediators that could affect coworkers' behaviors or reactions toward focal employees and focal employees' i-deals based on different theoretical perspective. For example, from the view point of equity theory, focal employees' i-deals may lead to coworkers' perception of unfairness, and thus affect coworkers' behaviors. In addition, based on the perspective of social learning, coworkers' admiration or envy elicited by others' i-deals may facilitate their learning from i-deals recipients. Future research should conduct more studies to explore coworkers' reactions to others' i-deals on the basis of different theory.

Conclusion

In this research, based on social comparison theory, we examined the influence of focal employees' development i-deals and flexibility i-deals on coworkers' acceptance. We found that coworkers' felt status threat can mediate the negative relationship between development i-deals and coworkers' acceptance. And coworkers' perception of obtaining future i-deals can mediate the positive relationship between flexibility i-deals and coworkers' acceptance. Furthermore, coworkers' RLMX plays a moderating role. Overall, our study suggests that coworkers are more likely to accept focal employees' flexibility i-deals than development i-deals.

Acknowledgements

Our research is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2020YJS070), Beijing Jiaotong University Science and Technology Funding (2018JBWZB003) and China Ministry of Education Young Scholar Research Funding (20YJC630162).