1 Introduction

In French wh-questions, the wh-phrase can be located in different positions, as illustrated in (1a–b) below. In (1a), the wh-phrase is fronted (in combination with pronominal inversion).Footnote [2] In (1b), it is left in-situ, i.e. at the same position as the corresponding element in a declarative, as seen in (1c). The prosodic properties of questions with this wh-in-situ strategy form the topic of the current paper.

Wh-in-situ questions as in (1b) can be used as regular requests for new information.Footnote [3] They are not part of the prescriptive grammar, but are frequently attested, often but not exclusively in an informal register (Quillard Reference Quillard2000, Myers Reference Myers2007). Questions of this form also occur as echo questions, ‘echoing’ the previous utterance. This is exemplified in (2), where part of speaker A’s utterance was not clearly audible, prompting speaker B to ask for a repetition.

There has been much discussion in the literature about the prosody of French wh-in-situ questions, but no consensus has been reached (see Section 2.2). Moreover, it is unclear whether echo and information seeking questions display different prosodic properties. In this paper, we report on a production experiment designed to thoroughly compare the prosodic properties of the two kinds of wh-in-situ question, controlling for focus marking.

The study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. It provides detailed prosodic descriptions of French wh-in-situ echo and information seeking questions. It then establishes that prosody clearly distinguishes the two, which is interpreted as an indication that echo questions should be regarded as a separate question type. It further shows that the prosody of French echo questions is congruous with a tentative generalisation we provide based on the existing literature, concerning the prosodic properties of wh-in-situ echo questions cross-linguistically. In addition, the study demonstrates that focus is prosodically marked in French wh-in-situ questions. It adds to the existing knowledge regarding the prosodic correlates of focus marking in French. What is more, it shows that focus may be marked in wh-interrogatives.

The paper is organised as follows. In Section 2 we provide the necessary background information. Section 3 presents the research question and the experimental design of our production experiment, for which we developed the elicitation paradigm Scripted Simulated Dialogue. Using this paradigm, we manipulated the context preceding a wh-in-situ question in order to elicit a particular type of question (echo or information seeking) and a particular focus structure in information seeking questions. Section 4 presents the results of the experiment and Section 5 provides discussion of the findings. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Background

We commence by providing some background information regarding echo questions as opposed to information seeking questions (Section 2.1), the prosodic properties of French wh-in-situ (echo) questions (Section 2.2), the prosody of echo questions in other languages (Section 2.3), the role of focus in wh-questions (Section 2.4) and prosodic focus marking in French (Section 2.5).

2.1 Echo questions versus information seeking questions

Although wh-echo and information seeking questions can be string-identical, it is clear from the cross-linguistic literature that they display different properties in several components of the grammar.

From a syntactic point of view, the most obvious property of echo questions is that their wh-phrase can be left in-situ in many languages that obligatorily front the wh-phrase in information seeking questions, e.g. John bought what? (Reis Reference Reis and Rosengren1992, Artstein Reference Artstein2002). Another syntactic difference is the possibility to replace only part of a constituent by a wh-phrase, e.g. John bought a what? (Reis Reference Reis and Rosengren1992, Reference Reis2012; Artstein Reference Artstein2002; Sobin Reference Sobin2010).Footnote [4]

Pragmatically, the use of an echo rather than an information seeking question signals that the speaker of the echo question does not yet accept a previous discourse move (Ginzburg & Sag Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000, Engdahl Reference Engdahl, Bonami and Hofherr2006, Poschmann Reference Poschmann2015, Biezma Reference Biezma2018). If the speaker of the echo question did not understand or perceive part of the previous utterance, s/he is not yet in a position to accept it; if the speaker is surprised by part of the previous utterance or does not believe it, s/he refuses to accept (part of) it for that reason.

Semantically, an information seeking wh-question is generally taken to be the set of propositions that constitute possible (true) answers to it, as depicted in (3) (Hamblin Reference Hamblin1973, Karttunen Reference Karttunen1977). An echo question raises a question regarding the meaning of a previous utterance, e.g. ‘What did you assert just now that John bought?’. Hence, the meaning of an echo question can be analysed as the set of propositions expressing the potential content of the preceding utterance, as in (4) (Ginzburg & Sag Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000, Engdahl Reference Engdahl, Bonami and Hofherr2006, Poschmann Reference Poschmann2015, Biezma Reference Biezma2018). (In accordance with standard notation, the denotation of an utterance is placed between ![]() and a set of propositions is indicated by { }.)

and a set of propositions is indicated by { }.)

As echo questions clearly differ from information seeking questions regarding their syntax and their semantico-pragmatic properties, the question rises whether they display different prosodic properties as well.

2.2 The prosody of French wh-in-situ echo and information seeking questions

It is unknown whether speakers distinguish echo and information seeking questions by prosodic means in French. Previous research investigating the prosody of information seeking wh-in-situ questions has yielded conflicting results. French wh-in-situ echo questions have not yet been studied in much detail.

Most of the debate surrounding the prosody of French wh-in-situ information seeking questions has centred on the question whether the utterances obligatorily end in a large rise (i.e. a rise with a large pitch excursion), as proposed by Cheng & Rooryck (Reference Cheng and Rooryck2000). In contrast, some authors claim that they standardly end in a fall (Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Di Cristo1998; Starke Reference Starke2001: 23; Mathieu Reference Mathieu2002, Reference Mathieu, Eguren, Fernandez-Soriano and Mendikoetxea2016). A third position maintains that a sentence-final rise is possible, but optional rather than mandatory (Wunderli Reference Wunderli1978, Reference Wunderli, Winkelmann and Braisch1982, Reference Wunderli1983; Wunderli & Braselmann Reference Wunderli and Braselmann1980, Adli Reference Adli, Meisenburg and Selig2004, Reference Adli2006; Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo2016). Testing Cheng & Rooryck’s (Reference Cheng and Rooryck2000) claim experimentally, Déprez, Syrett & Kawahara (Reference Déprez, Syrett and Kawahara2013) concluded that the majority of speakers uttered information seeking wh-in-situ questions with a small final rise, although this result was not replicated by Tual (Reference Tual2017). Reinhardt (Reference Reinhardt2019) shows in two corpus studies that while French wh-in-situ questions have a tendency to display a sentence-final rise, this is not a strict constraint. Her studies settle the debate to some extent, but do not yet explain the observed variation.

Another line of research has focussed on the prosody associated with the wh-phrase. According to Baunaz & Patin (Reference Baunaz and Patin2009) and Baunaz (Reference Baunaz2016), the wh-phrase does not bear any accent when a wh-in-situ question is uttered out of the blue (see also Wunderli & Braselmann Reference Wunderli and Braselmann1980, Wunderli Reference Wunderli, Winkelmann and Braisch1982). In contrast, Gryllia, Cheng & Doetjes Gryllia et al. (Reference Gryllia, Cheng and Doetjes2016) systematically found an emphatic pitch accent in questions uttered out of the blue as well as a rise at the end of the wh-phrase (see also Wunderli Reference Wunderli1983, Zubizarreta Reference Zubizarreta1998, Mathieu Reference Mathieu2002, Engdahl Reference Engdahl, Bonami and Hofherr2006, Hamlaoui Reference Hamlaoui2011).

So far, no studies have been designed to investigate the prosody of French wh-in-situ echo questions. There have been some brief descriptions, some of which describe echo questions as displaying a higher pitch overall (Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Di Cristo1998, Boeckx Reference Boeckx1999) or a sentence-final rise (Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Di Cristo1998, Reference Di Cristo2016; Boeckx Reference Boeckx1999; Mathieu Reference Mathieu2002, Reference Mathieu, Eguren, Fernandez-Soriano and Mendikoetxea2016; Adli Reference Adli2006; Engdahl Reference Engdahl, Bonami and Hofherr2006; Déprez et al. Reference Déprez, Syrett and Kawahara2013). Also, echo questions are described as exhibiting a prominent accent on the wh-word (Chang Reference Chang1997: 17; Mathieu Reference Mathieu2002; Engdahl Reference Engdahl, Bonami and Hofherr2006). Engdahl (Reference Engdahl, Bonami and Hofherr2006) mentions that the wh-word may also be lengthened. Déprez et al. (Reference Déprez, Syrett and Kawahara2013) investigated the prosody of echo questions in relation to information seeking questions experimentally, focussing exclusively on the final part of the utterance. This study offers some first evidence suggesting that the final rise in echo questions may be present more consistently and may display a somewhat larger pitch excursion. However, the methodology of the study does not allow for a statistical comparison of the question types, nor for a mapping of the F0 (i.e. pitch) movements to individual syllables.

In summary, it is not clear (i) what the prosodic properties are of wh-in-situ information seeking questions and (ii) whether these properties differ from the ones of wh-in situ echo questions, and if so, how: a final rise and an accent on the wh-phrase have been claimed for both question types.

2.3 Cross-linguistic comparison

For some languages other than French, there have been more detailed comparisons between wh-in-situ echo questions expressing auditory failure and information seeking questions. Although the reported prosodic properties of echo questions differ cross-linguistically, echo questions seem to be uttered with a distinct prosody in several languages. The following, tentative, generalisation seems to hold within the small sample of languages for which relevant descriptions could be found:

Brazilian Portuguese (Kato Reference Kato, Camacho-Taboada, Fernández, Martín-González and Reyes-Tejedor2013), Farsi (Esposito & Barjam Reference Esposito and Barjam2007, Sadat-Tehrani Reference Sadat-Tehrani2011) and Manado Malay (Stoel Reference Stoel, van Heuven and van Zanten2007) are examples of pattern (A); pattern (B) is exemplified by North-Central Peninsular Spanish (González & Reglero Reference González, Reglero, Repetti and Ordóñez2018), Greek (Roussou, Vlachos & Papazachariou Reference Roussou, Vlachos, Papazachariou, Lavidas, Alexiou and Sougari2014) and Shingazidja, a Bantu language spoken on Comoros (Patin Reference Patin2011). German also follows pattern (B), but the difference between the question types is very small (Repp & Rosin Reference Repp and Rosin2015), possibly because information seeking wh-in-situ is very restricted in this language. Mandarin Chinese seems to be the only language for which the two question types have been compared, but no distinct prosody for echo questions was consistently found (Hu Reference Hu2002).

2.4 Focus in wh-questions

Focus has not been taken into account in the studies surveyed in the previous section. We will now motivate why we include focus in our study.

For declaratives, it is well-known that there is an interaction between the focus of a sentence and its prosodic properties (see for instance Büring Reference Büring2016 for a recent overview). Although discussed to a lesser extent, the interaction between context and prosody has also been observed in wh-questions (Jacobs Reference Jacobs1984, Erteschik-Shir Reference Erteschik-Shir1986, Jacobs Reference Jacobs1991, Lambrecht & Michaelis Reference Lambrecht and Michaelis1998, Engdahl Reference Engdahl, Bonami and Hofherr2006, Eckardt Reference Eckardt2007, Truckenbrodt Reference Truckenbrodt, Elordieta and Prieto2012, Büring Reference Büring2016). Whereas some languages mark the wh-phrase prosodically as the focus of the question, this is not the case in all languages (Ladd Reference Ladd2009: 226–227). In many languages, including English, German and also French, the neutral location for the main accent is not on the wh-word and context may affect the prosody of a wh-question. In a wh-question such as (5), adapted from Erteschik-Shir (Reference Erteschik-Shir1986: 118), who cites Gunter (Reference Gunter1966: 172), the accentuation represented in a. rather than the one in b. or c. is the most neutral one, while b. or c. impose specific restrictions on the context. For instance, (5b) might be uttered if the preceding context specifies that John ate the beans, but not at what point in time this happened. Similarly, (5c) could be uttered if the preceding context indicates the time at which John prepared the beans, but not when he ate them.

The responses of researchers to this type of data fall into two categories. Some authors stress the grammatical character of the wh-phrase as the focus of the sentence and attempt to explain the prosodic properties of wh-questions without reference to focus (Culicover & Rochemont Reference Culicover and Rochemont1983, Lambrecht & Michaelis Reference Lambrecht and Michaelis1998). Others, viewing focus from the perspective of pragmatics, propose that the relation between context and prosody illustrated in (5) can be explained in terms of focus marking, similar to in declaratives (Jacobs Reference Jacobs1984; Erteschik-Shir Reference Erteschik-Shir1986; Jacobs Reference Jacobs1991; Rosengren Reference Rosengren1991; Kadmon Reference Kadmon2001: 388–397; Reich Reference Reich2002; Beyssade Reference Beyssade2006; Engdahl Reference Engdahl, Bonami and Hofherr2006; Eckardt Reference Eckardt2007; Truckenbrodt Reference Truckenbrodt, Elordieta and Prieto2012; Büring Reference Büring2016; Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo2016). Here we adopt the second approach, following the implementation of Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1984, Reference Jacobs1991), which has been applied to French by Beyssade et al. (Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Rialland2004a, Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Riallandb).

In this approach, focus is defined as the part of the content that is ‘inhaltlich besonders betroffen’, i.e. specifically affected, by the illocutionary operator of the sentence (Jacobs Reference Jacobs1984: 30). The partition of an utterance into focus and ground takes place within the scope of an illocutionary operator. In declaratives, the focus contributes the part of the content that is specifically affected by the assertive operator, i.e. the part that is asserted in particular and that is informative. In interrogatives, the focus is specifically affected by the question operator and provides information that is not given in the discourse situation in which the question is uttered. As Jacobs points out, it is important to distinguish the existential implicature that arises from all the wh-questions in (5), namely that there is a time at which John ate the beans, from the notion of ground. In (5a), the discourse situation does not need to provide information about the contents of the question as in this case the whole question is marked as focus. In (5b) and (5c), however, the context that directly precedes the question needs to specify the information that is marked as ground by the prosody of the wh-question. As a result, (5b) can only be uttered felicitously if the information that John ate the beans is given in the context directly preceding it, as the accent on when introduces a narrow focus on the wh-word. Similarly, the contextual restrictions on the use of (5c) follow from the narrow focus on the verb eat.

For wh-echo questions, it is commonly assumed that there is a narrow focus on the wh-phrase (Jacobs Reference Jacobs1991, Bartels Reference Bartels1997, Reis Reference Reis2012): the whole non-wh part of the utterance content must belong to the ground, since it is ‘echoed’ from the previous utterance. Assuming the approach to focus outlined above, the focus structure of information seeking wh-questions may be very different, depending on the preceding context. Therefore, a comparison between the two question types should involve information seeking questions with a focus structure resembling the one in echo questions, i.e. information seeking questions with narrow focus on the wh-phrase, as well as information seeking questions in a context that is maximally different from the echo context in the sense that it gives hardly any information about the content of the question.

2.5 Prosodic focus marking in French

In languages like English, focus is marked by the presence of the nuclear pitch accent (Pierrehumbert Reference Pierrehumbert1980, Selkirk Reference Selkirk, Aronoff and Oehrle1984, Pierrehumbert & Hirschberg Reference Pierrehumbert, Hirschberg, Cohen, Morgan and Pollack1990); for French, this is less clear. The right edge of a focus is preferably aligned with (i.e. situated at) the right edge of a prosodic constituent (Clech-Darbon, Rebuschi & Rialland Reference Clech-Darbon, Rebuschi, Rialland, Rebuschi and Tuller1999; Féry Reference Féry, Féry and Sternefeld2001, Reference Féry2013; Beyssade et al. Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Rialland2004a, Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Riallandb; Hamlaoui Reference Hamlaoui2008; Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Frota and Prieto2015). A focus is marked by a tone at its right edge (Martin Reference Martin1981, Rossi Reference Rossi1981); in this paper, we assume that this is the boundary tone associated with the right edge of the prosodic constituent (Intonation Phrase) with which the focus is aligned (Beyssade et al. Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Rialland2004b).Footnote [5]

The boundary tone at the right edge of a focus tends to be low in declaratives and high in interrogatives, reflecting the illocutionary force of the utterance (Martin Reference Martin1981, Clech-Darbon et al. Reference Clech-Darbon, Rebuschi, Rialland, Rebuschi and Tuller1999, Beyssade et al. Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Rialland2004b, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes & Sleeman Reference Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes and Sleeman2004, Doetjes, Rebuschi & Rialland Reference Doetjes, Rebuschi and Rialland2004; Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Frota and Prieto2015). In all-focus utterances and sentences in which a narrow focus occurs sentence-finally, the tone is located at the end of the utterance. In other narrow focus utterances, the tone usually occurs twice, both at the end of the focus and at the end of the utterance: this phenomenon is referred to as tone copying (Martin Reference Martin1981). Specifically, Martin claims that the F0 minimum (in declaratives) or maximum (in interrogatives) of the final syllable of the focus is copied to the final syllable of the utterance.

Whereas it is generally accepted that a tone or accent marks the right edge of a focus, it is less clear whether the pre-focus domain is marked as well. Some authors have observed a compression of the pitch (Touati Reference Touati1987, Jun & Fougeron Reference Jun, Fougeron and Botinis2000, Dohen & Lœvenbruck Reference Dohen and Lœvenbruck2004) and a reduced amplitude (Jun & Fougeron Reference Jun, Fougeron and Botinis2000). In contrast, Beyssade et al. (Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Rialland2004b) state that there is no pitch compression in the pre-focus domain.

Previous work on focus marking in French interrogatives rarely addresses wh-in-situ questions. According to Di Cristo (Reference Di Cristo2016), French wh-in-situ questions can have a narrow focus on the wh-phrase or a broad focus reading, but this difference is not reflected in the prosody. Di Cristo claims that the right edge of the wh-phrase is marked by an accent in all cases. However, in the examples he discusses, the wh-phrase is situated at the end of the sentence. This means that the right edge of the focus co-occurs with the right edge of the sentence and tone copying cannot apply.

3 Research question and experimental design

The preceding subsections show that the prosodic characteristics of French wh-in-situ questions are not well understood. Moreover, it is unclear whether echo and information seeking questions, which may be string-identical, are prosodically distinct, and if so, how. In this section, we present the research question and the experimental design of a production experiment that was designed to investigate this issue. Focus marking was taken into account in order to avoid a confound between the effects of focus marking and the effects resulting from the echo/non-echo distinction.

We also take steps to prevent another confound, which relates to the type of echo question under investigation. Two main types are commonly distinguished (Pope Reference Pope1976, Bartels Reference Bartels1997). The type exemplified in example (2), repeated here for convenience, expresses a failure to perceive or understand part of a previous utterance.

Another common use of echo questions is to express an emotion in the spectrum of surprise, disbelief or outrage regarding part of a previous utterance, as would be the case if speaker B’s utterance in (2) had followed an utterance like Jean a invité le president ‘Jean invited the president’. Yet, the emotion of surprise itself can also affect the prosodic properties of speech utterances (Hirschberg & Ward Reference Hirschberg and Ward1992). Therefore, we focus in our investigation on the type of echo question that expresses auditory failure. We will use the term ‘echo question’ to refer to this particular type of wh-in-situ echo questions, unless specified otherwise. Hence, we formulated the following research question, which falls apart into three sub-questions:

In order to answer this research question we set up three conditions:

We elaborate on the properties of these conditions in Section 3.2. The conditions were created by manipulating the context preceding the target sentences. We start by laying out the elicitation paradigm designed to accomplish this context manipulation (Section 3.1). Subsequently, the constructed materials are discussed, which include items and contexts (Section 3.2). We then lay out the recording procedure (Section 3.3), the participants (Section 3.4) and the acoustic (Section 3.5) and statistical analyses (Section 3.6).

3.1 Elicitation paradigm: Scripted Simulated Dialogue

To elicit the three conditions, we designed a paradigm that we will refer to as Scripted Simulated Dialogue. This elicitation paradigm simulates a series of short dialogues, in which the participant’s interlocutor is a recorded voice. The participant’s half of the dialogue is scripted: s/he reads his/her speech turns from a computer screen. Every dialogue has one target sentence or filler embedded in it, always at the same position in the dialogue. As this position is almost at the end of the dialogue, the preceding discourse can be used to manipulate a particular reading of the sentence. The participant does not know which is the target sentence.

Every dialogue is preceded by a description of the conversational setting, which contains information about who the interlocutors are and where the conversation takes place. The context manipulation thus has two elements: the description of the conversational setting and the preceding speech turns.

Following a dialogue, the participant receives a question about the information supplied by the recorded ‘interlocutor’. The purpose of this is to direct the participants’ attention to the content of the dialogue, rather than the form of the utterances.

3.2 Materials

Twelve target stimuli were created. As each of these was presented in three conditions, this yielded a total of thirty-six target utterances. The stimuli had twelve syllables; an example is shown in (8).

All stimuli contained the pronoun tu ‘you’ as a subject (to avoid differences in the information status of the subject), followed by a verb composed of the auxiliary as ‘has’ and a three-syllable past participle. Next came the wh-phrase, which was the direct object of the utterance. It contained the wh-word quel ‘which’ and a disyllabic noun. We chose to use complex wh-phrases (rather than, for instance, quoi ‘what’) to keep the prosody associated with the wh-word distinct from the prosodic correlates of a possible phrase boundary at the end of the wh-phrase. A PP, composed of a one-syllable preposition and a three-syllable DP, followed the wh-phrase. Its purpose was to separate the prosody associated with the wh-phrase from the prosody associated with the end of the utterance.Footnote [6] Sonorants were used as much as possible to facilitate F0 measurements.

The target sentences were intermingled with thirty-six fillers. Twelve of these were declaratives that resembled the discourse–pragmatic function of echo questions, such as Désolé, je n’ai pas bien entendu ‘Sorry, I didn’t hear that well’. The remaining 24 fillers were sentences that fitted naturally in the context and that were not wh-in-situ questions.

Each stimulus or filler was embedded in a dialogue. The dialogues had six speech turns in total (three for the participant and three for the recorded ‘interlocutor’). The stimulus or filler was part of the participant’s last speech turn, with the ‘interlocutor’s’ last speech turn following it. The dialogues, which were written and checked by three native speakers of French, were constructed to be natural and informal. The voice that represented the ‘interlocutor’ was a female native speaker of French, while the description of the conversational setting that preceded a dialogue was read by a male speaker (to make the distinction clear). Both were recorded in the phonetics lab at Leiden University.

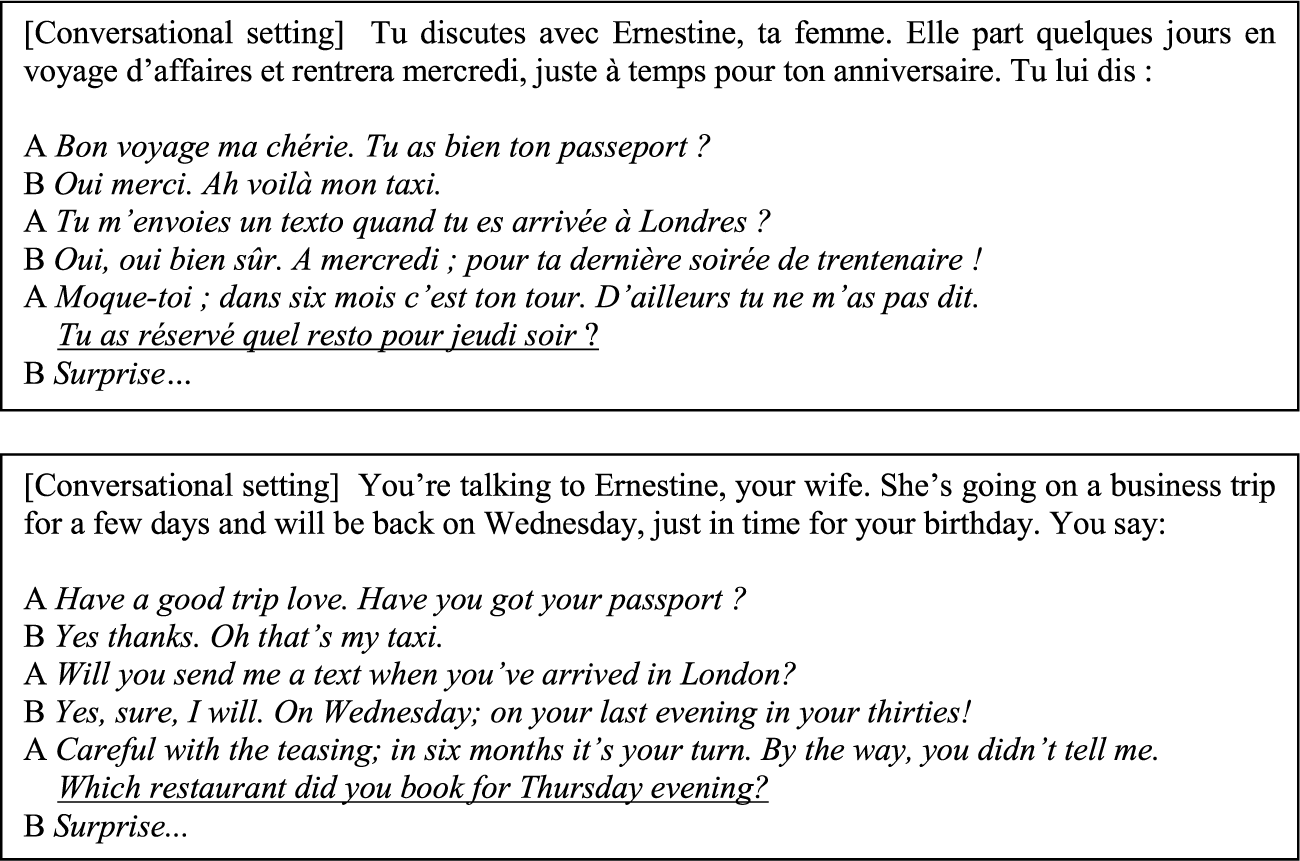

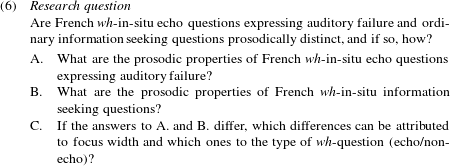

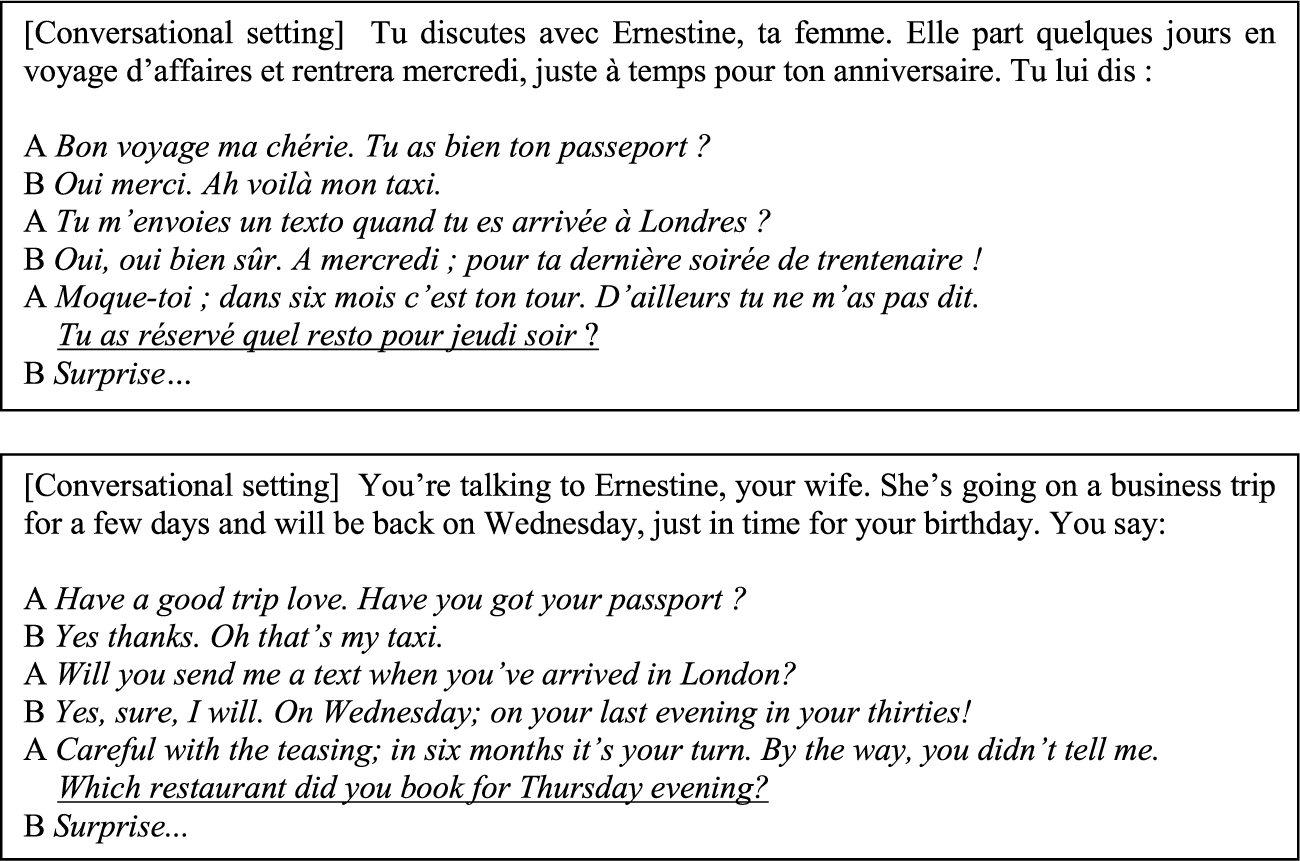

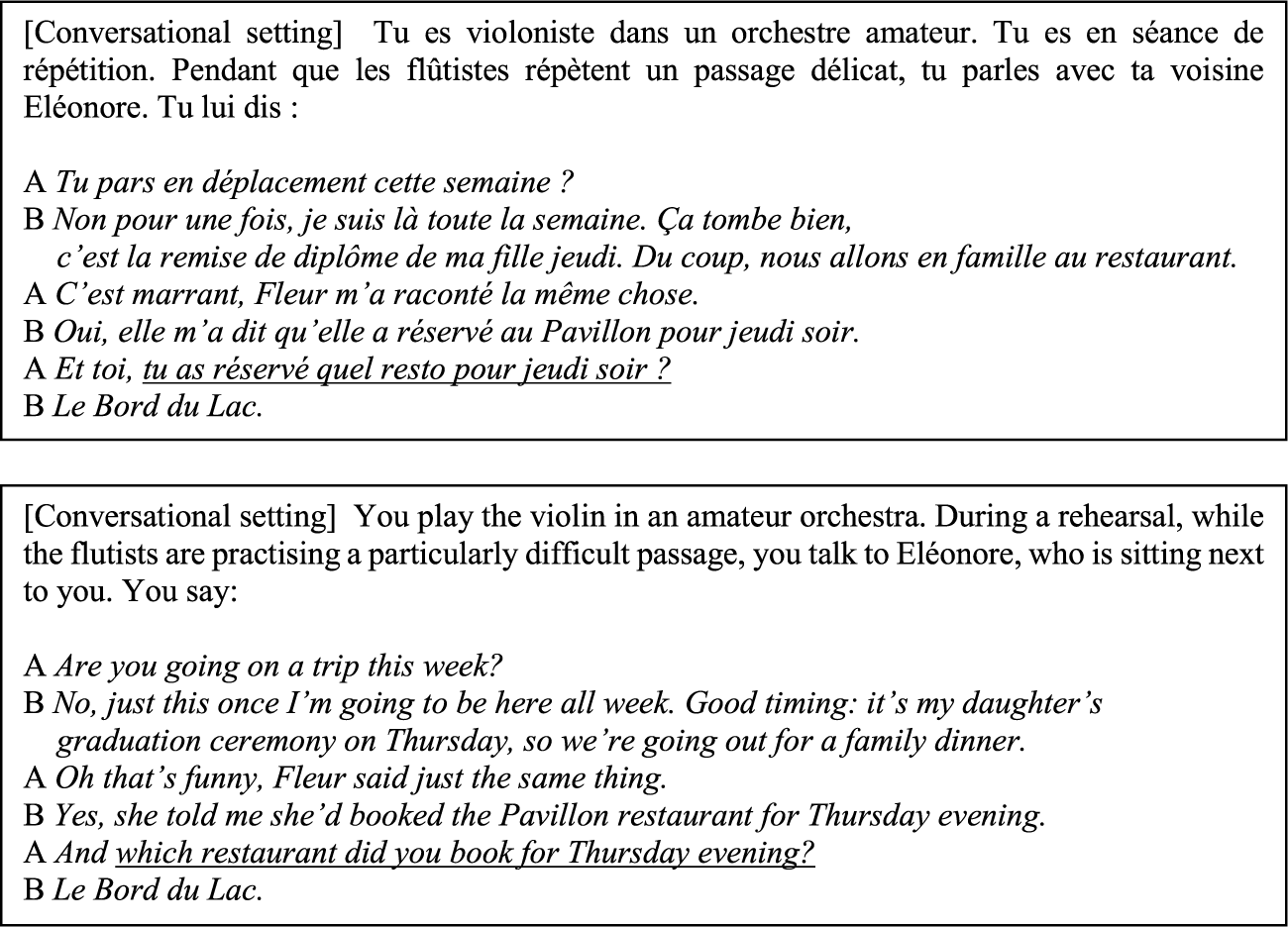

Except for the dialogues containing fillers, each dialogue had certain properties that were intended to trigger either an echo question expressing auditory failure (Condition A), an information seeking question with broad focus (Condition B) or an information seeking question with narrow focus on the wh-phrase (Condition C). Figures 1, 2 and 3 present examples of dialogues used in the three conditions; in each case, the description of the conversational setting precedes the dialogue. Speaker A represents the participant and Speaker B the ‘interlocutor’. The target sentence is underlined, although this was not the case in the actual experiment.

Figure 1 Scripted Simulated Dialogue used in Condition A (echo question).

In the example in Figure 1, pink noise would cover the word Monette (represented as struck through text), causing a need to ask for repetition. An episode of pink noise was also present in all other contexts (pertaining to the other conditions and the fillers), but in a position where it would not hinder the conversation, for instance on the final syllable of a long word.

Figure 2 Scripted Simulated Dialogue used in Condition B (broad focus).

Condition B was designed to elicit ordinary information seeking wh-in-situ questions with broad focus. Although the target sentence was preceded by context, it provided little information about the content of the question. Whereas the interlocutors would have to share certain assumptions to make it natural to ask an (in-situ) wh-question, no part of the content of the question would be mentioned in the preceding context. To signal this departure from the topic of the preceding conversation, a topic change marker was used (Fraser Reference Fraser1999), like d’ailleurs tu ne m’as pas dit ‘by the way, you didn’t tell me’ in Figure 2.

Figure 3 Scripted Simulated Dialogue used in Condition C (narrow focus).

In Condition C, the context was designed to force a reading as an information seeking question with narrow focus on the wh-phrase. The context would mention all elements of the content of the question except the wh-word, i.e. ‘booking a restaurant for Thursday evening’ in Figure 3. Hence, everything but the wh-word would belong to the ground of the focus domain. In order to implement this restriction on the context, while keeping the flow of the discourse natural, we used wh-in-situ questions with a contrastive topic, as in Engdahl (Reference Engdahl, Bonami and Hofherr2006: 100). Subject pronouns in French are clitics and cannot be contrastively stressed (Kayne Reference Kayne1975). To express contrastive topichood, French uses another, ‘strong’ pronoun, which may be coreferential with a clitic (Lambrecht Reference Lambrecht1994: 115–116). We used et toi ‘and you’, which was taken up by the resumptive clitic tu ‘you’ in the clause proper. Hence, the sentence following the contrastive topic et toi ‘and you’ was string-identical to the target stimuli used in Conditions A and B.

3.3 Recording procedure

Recordings took place in a soundproof booth at Pôle Audiovisuel et Multimédia (PAM) at the University of Nantes. Participants were seated in front of a computer screen at an approximate distance of 50cm. They wore AKG K 44 perception headphones. The speech was recorded onto digital audio tape (DAT) at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz, using a TASCAM DR-100 recorder and a TRAM TR50 clip-on microphone.

Participants were informed that they would be taking part in a series of short dialogues with a recorded ‘interlocutor’ that they would hear through their headphones and that their side of the dialogue would appear on the screen in front of them. They were encouraged to project themselves into the situation represented by the dialogue, speaking naturally, ‘as if they were just talking to someone’, and to repeat their utterance in case of a lapse. These instructions were presented visually on the computer screen and reiterated orally at the beginning of the experiment. After that, the experimenter did not intervene.

Participants pressed a key once they were ready to start the experiment. This would prompt the recording of the first conversational setting to be played through the headphones (in a male voice), while the screen was blank. Every conversational setting ended with Tu dis: ‘You say:’. Then the participant’s first speech turn would appear on the screen. The participant would utter his/her speech turn, after which s/he would press a key for the ‘interlocutor’s’ speech turn to start playing through the headphones (in a female voice) while the screen was blank again. Then the participant’s next speech turn would appear on the screen. This process would be repeated until the participant had uttered the question that formed the target sentence in his/her third speech turn (or a filler) and received an answer in the ‘interlocutor’s’ third and last speech turn. The alternation of speaking, then pressing a key and listening to the ‘interlocutor’ very soon became an automatic process. After the last speech turn of every dialogue (items or filler), a multiple choice sentence completion task would appear on the screen, asking about information supplied by the ‘interlocutor’. The participant would answer the question by pressing 1, 2 or 3. Feedback on the answer would appear on the screen: it was usually correct, since the task was designed to be easy if the participant paid attention to the ‘interlocutor’s’ speech turns. The participant would then press a key to move on to the next trial. The whole paradigm was programmed in E-Prime (Psychology Software Tools Inc. 2012).

The dialogues were randomized and presented to participants in three blocks, with breaks in between. Three practice trials were used for familiarisation purposes. The experiment lasted approximately an hour.

3.4 Participants

Twenty graduate and postgraduate students at the University of Nantes, monolingual native speakers of French, were reimbursed to participate in the experiment (13 female and 7 male, age range 18–29 years old). None of them reported any speech or hearing disorders.

3.5 Acoustic analysis

We obtained a total of 720 utterances. After inspection of the data for speech errors, hesitations or unnatural pausing, we excluded 98 utterances from further analysis. The remaining 622 utterances were segmented into phones, syllables and words using EasyAlign (Goldman Reference Goldman, Cosi, De Mori, Di Fabbrizio and Pieraccini2011). The segmental boundaries were then checked and adjusted manually where necessary.

We inspected the utterances again to uncover any patterns in the data, such as the occurrence of different prosodic tunes within the data elicited in one condition. We marked the number of occurrences of each prosodic tune.

Based on this inspection, we selected the utterances for the statistical analyses. We followed the reasoning that if a. a prosodic tune occurred in the majority of cases elicited in a particular condition and b. none of the other tunes came close to its frequency, then this prosodic tune might be considered to be the characteristic prosodic tune of utterances elicited in that condition. We included the items uttered with these characteristic prosodic tunes in the statistical analyses, with the exception of cases that exhibited the characteristic prosodic tune, but with a variation (see also Section 4.1 below). This was done to achieve a sample that was as homogeneous as possible.

We selected the following seven F0 measurement points, which are visualised in Figure 4:

Figure 4 Waveform and F0 tune of the question Tu as réservé quel resto pour jeudi soir? ‘You booked which restaurant for Thursday evening?’ elicited in Condition A (echo question), together with a textgrid illustrating the seven measurement points.

We also obtained the following F0 measurements:

We extracted the F0 values with the help of a Praat script (Boersma & Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2017), which took the values from the voiced part of the respective syllables. As rises in French have been shown to continue onto a sonorant syllable coda, and even (in rare cases) on a voiced obstruent coda (Welby & Lœvenbruck Reference Welby and Lœvenbruck2005), we included voiced consonants in our analysis. The F0 values in Hertz were subsequently converted into semitones (st) to reduce variation. (We used the formulas st = 12 log2 (Hz/100) for female speakers and st = 12 log2 (Hz/50) for male speakers respectively, following Li & Chen Reference Li and Chen2012.) In addition, we extracted the duration and the mean intensity in decibel (dB) of every syllable, using two more Praat scripts.

3.6 Statistical analysis

We ran a series of linear mixed-effects models using the lmer function of the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (R Core Team 2017). P-values were obtained using the package lmerTest (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff & Christensen Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017). Specifically, we ran a model with the relevant measurement as the dependent variable, question type as a fixed factor, and items and participants as random factors for every measurement. To obtain all relevant comparisons we ran the analyses for each reference category (Echo, Broad focus, Narrow focus). The reader is referred to the statistical appendix for more details.

4 Results

We now present the results of the experiment. First we provide descriptions of the three tunes that turned out to be characteristic of the utterances elicited in the respective conditions (Section 4.1). The remainder of the section is devoted to the comparisons between these three tunes with respect to F0 (Section 4.2) and duration and intensity (Section 4.3), after which we provide a summary of the results (Section 4.4). In short, the main results reveal that the utterances elicited in Condition A (echo questions) differ from those in Condition B (information seeking questions with broad focus) regarding F0 and duration, though not greatly regarding intensity. Comparisons with Condition C (information seeking questions with narrow focus on the wh-phrase) show that some of the differences are correlated with focus structure, indicating that these are correlates of focus marking. Other differences are not correlated with focus structure, suggesting that these mark the discourse–semantic function of echo questions.

4.1 Descriptions of the three characteristic prosodic tunes

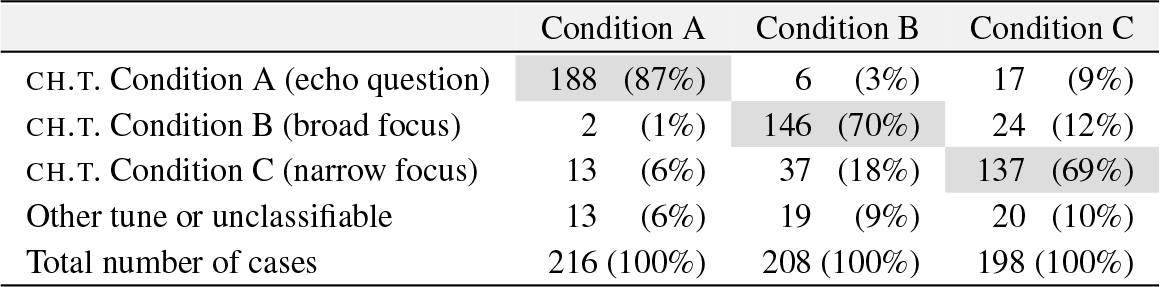

Three prosodic tunes were frequently attested in the data; each of these tunes occurred in all three conditions. However, in every condition there was one tune that a. was attested much more frequently than any other tune and b. occurred only infrequently in the other conditions. Hence, this tune seemed to be the characteristic tune (ch.t.) of the respective condition. As mentioned, we used the utterances pronounced with the characteristic tune of the respective condition as input for our analyses. The distribution of the different prosodic tunes is illustrated in Table 1. For the sake of presentation, we will refer to the characteristic tunes of the three conditions as the Echo Tune, the Broad focus Tune and the Narrow focus Tune.

Table 1 The prosodic tunes and their frequencies attested in Conditions A, B and C. Shading marks the characteristic tune of each condition.

CH.T. = characteristic tune

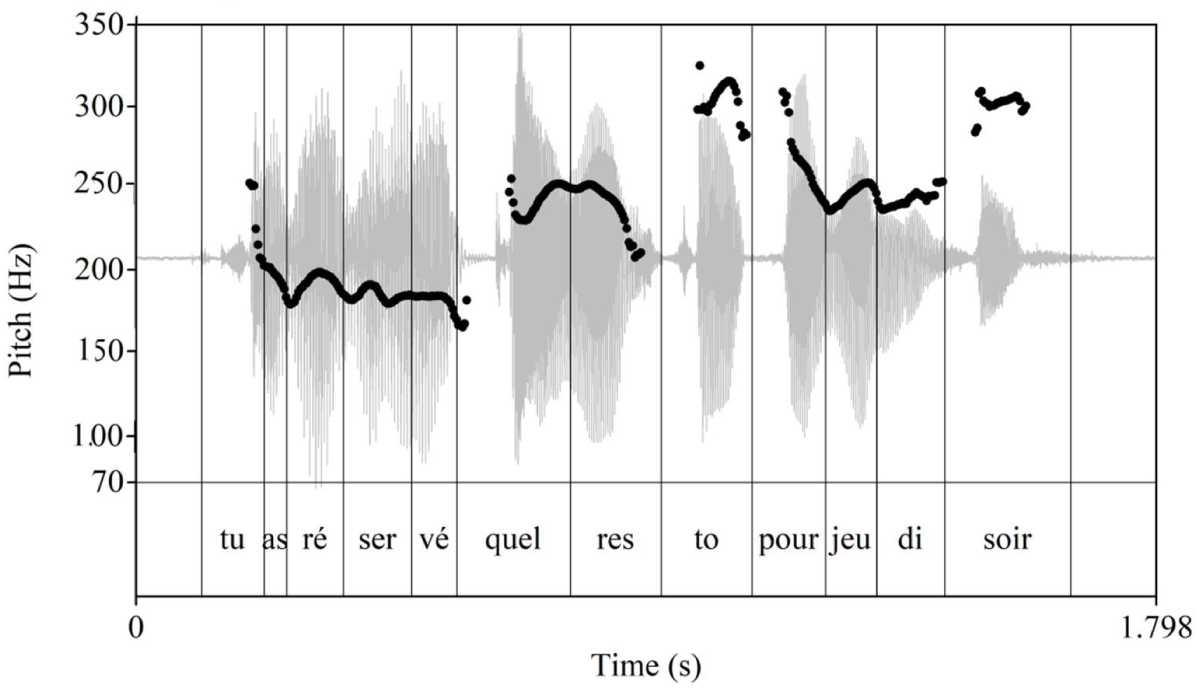

Figure 5 Waveform and F0 tune of the question Tu as réservé quel resto pour jeudi soir? ‘You booked which restaurant for Thursday evening?’, uttered with the Echo Tune by a female speaker.

We will now describe these three tunes. Figure 5 displays an example of an Echo Tune. In this tune, the F0 is quite low in the area of the utterance preceding the wh-phrase. There is a high point associated with the wh-word quel ‘which’. The F0 rises to an even higher point associated with the final syllable of the wh-phrase; this peak can be high in the speaker’s register. The F0 falls again on the PP, but not to the level of the beginning of the utterance: the F0 usually remains high. At the end of the utterance, the F0 rises to an extreme F0 level again, which is often similar to the F0 on the final syllable of the wh-phrase.

Figure 6 shows an example of a Broad focus Tune. There is a high point associated with the wh-word quel ‘which’, as in the Echo Tune. Subsequently, there is a high point associated with the end of the wh-phrase, which varies in height. (The peak can be late, aligned with the preposition.) There is often an F0 fall between these two high points associated with the wh-phrase, but the F0 can also stay level, forming a plateau over the whole wh-phrase. The F0 then falls on the PP, after which the sentence usually ends with a rise, which is often (very) small.

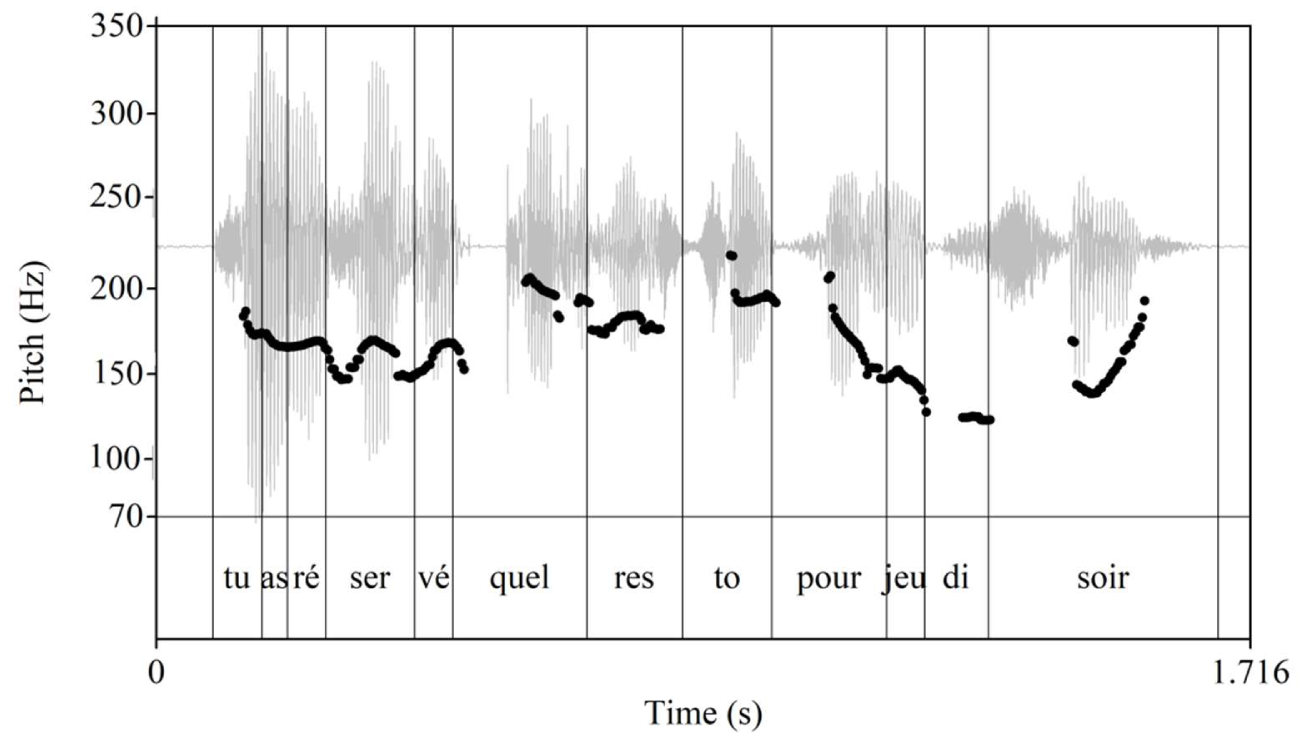

Figure 6 Waveform and F0 tune of the question Tu as réservé quel resto pour jeudi soir? lit.: ‘You booked which restaurant for Thursday evening?’, uttered with the Broad focus Tune by a male speaker.

Figure 7 (on next page) displays an example of a Narrow focus Tune. The speaker is the same as the one that uttered the example of the Echo Tune in Figure 5 above. Recall that utterances elicited in Condition C (narrow focus) were preceded by the contrastive topic et toi ‘and you’ (see Section 3.2 above for discussion). In the vast majority of cases, there is a high point associated with this contrastive topic (consistent with previous descriptions, Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes and Sleeman2004). Sometimes the contrastive topic is followed by a pause, with a subsequent pitch reset at the beginning of the utterance proper. When there is no pause, the F0 falls gradually from the high point of the contrastive topic: the fall covers tu ‘you’ and often (part of) as ‘have’. As in the Echo Tune, the rest of the area preceding the wh-phrase has low pitch. In contrast to both other tunes, there is either no high point associated with the wh-word, or a high point that is much lower. There is, however, a high point associated with the last syllable of the wh-phrase. On the PP following the wh-phrase, the F0 falls, often to the level of the area preceding the wh-phrase. At the end of the utterance there is an F0 rise, which often reaches a level similar to the high point at the end of the wh-phrase, like in the Echo Tune.

Figure 7 Waveform and F0 tune of the question Tu as réservé quel resto pour jeudi soir? lit.: ‘You booked which restaurant for Thursday evening?’, uttered with the Narrow focus Tune by a female speaker.

These descriptions show that there are clear differences between the three tunes. Nevertheless, two features are present in all of them. Firstly, there is a high point associated with the end of the wh-phrase, followed by a fall on the PP, which we interpret as a prosodic boundary. Secondly, all three tunes end with at least a small sentence-final rise (which seems larger in the Echo Tune and the Narrow focus Tune than in the Broad focus Tune).

Note that in all three characteristic tunes, one or both of these features were absent in some cases.Footnote [8] We excluded the utterances with a variation from the statistical analyses to achieve a sample that was as homogeneous as possible. Hence, we conducted the analyses on 164 utterances exhibiting the Echo Tune in Condition A, 130 utterances exhibiting the Broad focus Tune in Condition B and 136 utterances exhibiting the Narrow focus Tune in Condition C.

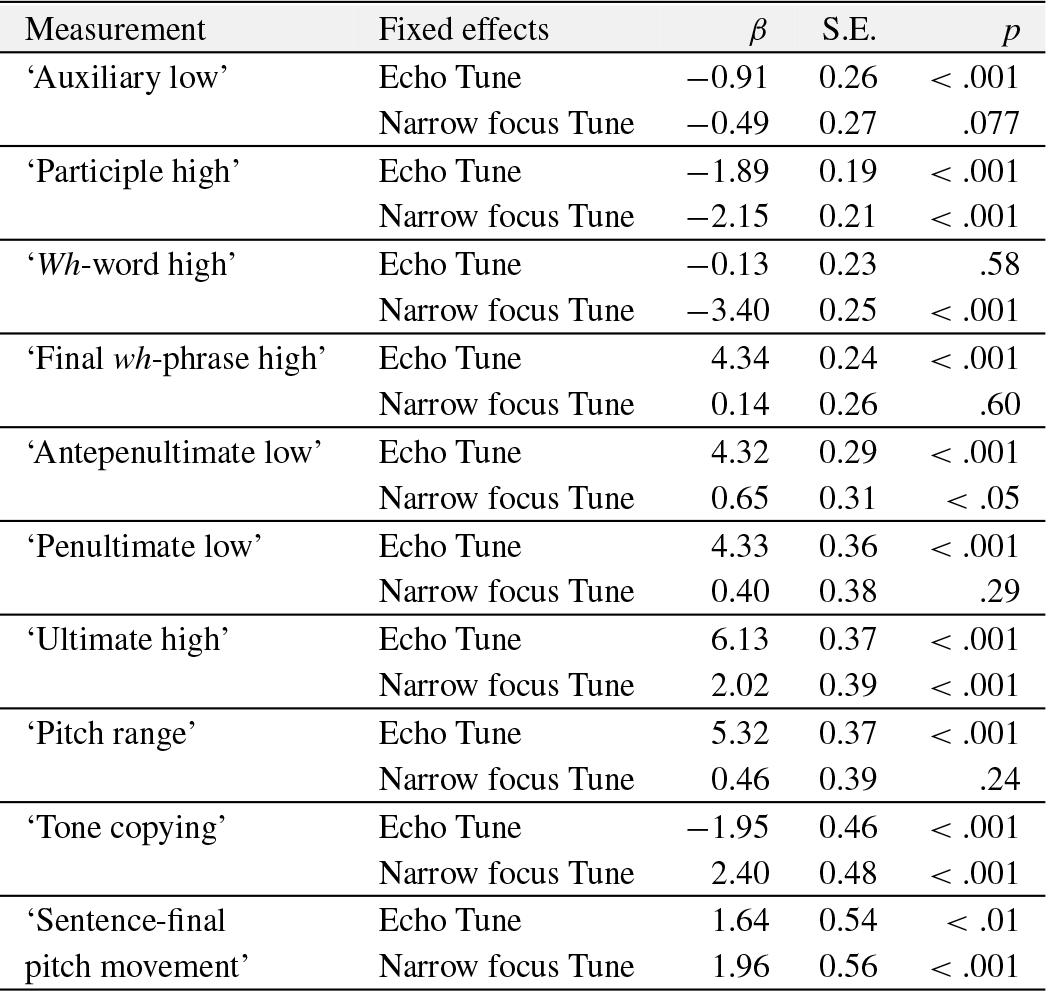

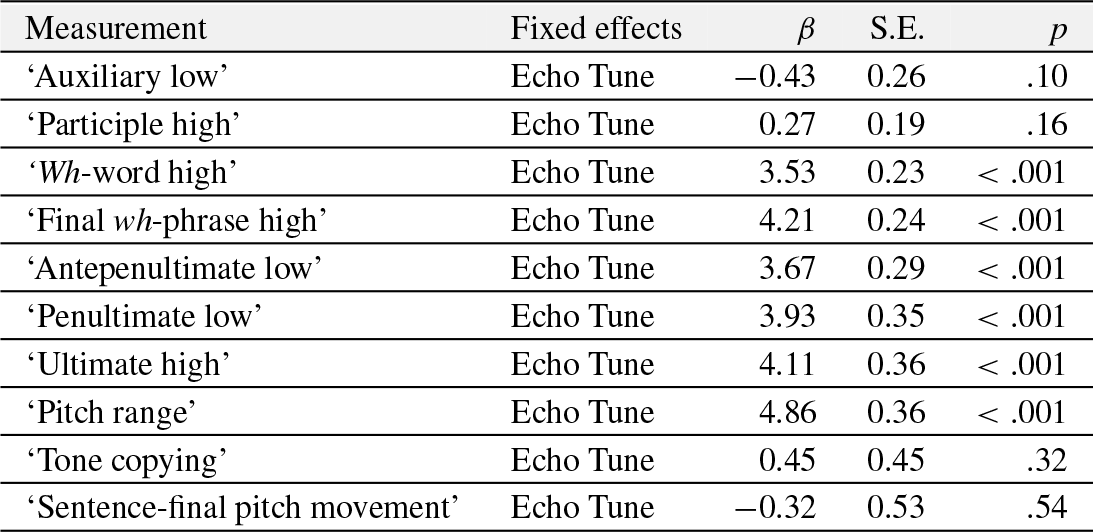

4.2 Comparisons of the three characteristic tunes regarding F0

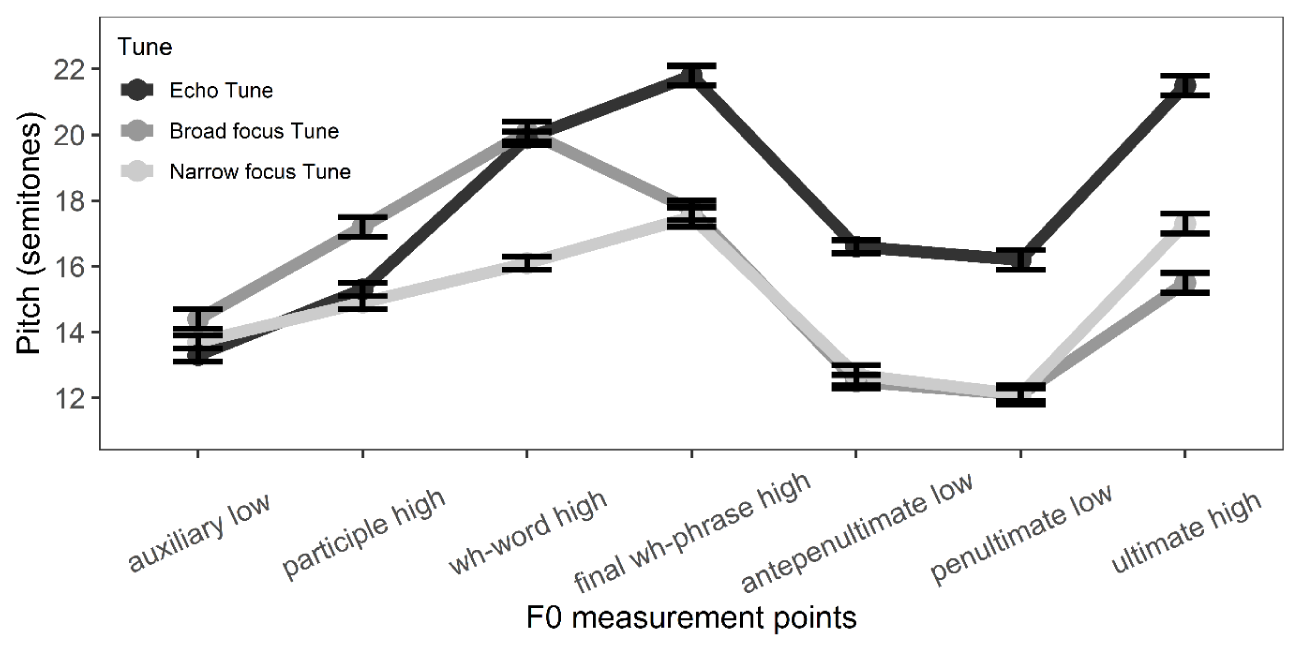

We now turn to comparisons between the three tunes regarding their F0, starting with a visualisation of the average F0 at the seven measurement points in Figure 8. All reported differences in semitones (st) are significant; see Tables A1 and A2 in the statistical appendix for details. As shown in Figure 8, the Echo Tune and the Narrow focus Tune have lower pitch than the Broad focus Tune in the part of the utterance preceding the wh-phrase. At the participle (‘participle high’), this difference is significant for both the Echo Tune (1.9 st) and the Narrow focus Tune (

![]() $-$

2.3 st). At the auxiliary (‘auxiliary low’) however, the Echo Tune is significantly lower (

$-$

2.3 st). At the auxiliary (‘auxiliary low’) however, the Echo Tune is significantly lower (

![]() $-$

1.1 st), but the Narrow focus Tune only marginally so (

$-$

1.1 st), but the Narrow focus Tune only marginally so (

![]() $-$

0.7 st). The F0 of the Echo Tune and the Narrow focus Tune does not differ in this part of the utterance.

$-$

0.7 st). The F0 of the Echo Tune and the Narrow focus Tune does not differ in this part of the utterance.

Figure 8 Average F0 at seven measurement points in the characteristic tunes of utterances elicited in Condition A (echo question), Condition B (broad focus) and Condition C (narrow focus), of the form Tu as réservé quel resto pour jeudi soir? lit.: ‘You have reserved which restaurant for Thursday evening?’.

At the wh-word quel ‘which’ (‘wh-word high’), the F0 maximum in the Echo Tune and the Broad focus Tune are equal in height. However, consistent with the observation of no or a much lower peak here (Section 4.1), the F0 maximum in the Narrow focus Tune is significantly lower than in both other tunes (

![]() $-$

4.0 st Broad focus Tune,

$-$

4.0 st Broad focus Tune,

![]() $-$

3.8 st Echo Tune).

$-$

3.8 st Echo Tune).

From the final syllable of the wh-phrase onwards, the tonal movements in all tunes seem to be the same, but the F0 in the Echo Tune is elevated. The high point on the final syllable of the wh-phrase (‘final wh-phrase high’) is much higher in the Echo Tune than in both other tunes (Broad focus Tune 4.1 st, Narrow focus Tune 4.3 st). The F0 remains much higher on the F0 minimum of the antepenultimate syllable (‘antepenultimate low’), the F0 minimum of the penultimate syllable (‘penultimate low’) and the F0 maximum of the final syllable of the utterance (‘ultimate high’). These F0 differences between the Echo Tune and the other two tunes are large: they range between 3.9 st and 6 st and are highly significant. The Narrow focus Tune and the Broad focus Tune behave similarly in this part of the utterance, with the exception of the final syllable of the utterance. There, the Narrow focus Tune has significantly higher pitch than the Broad focus Tune (1.8 st).

We now turn to the difference in F0 between certain points in the utterance. We first report on the pitch range, which was measured as the difference between the F0 maximum on the final syllable of the wh-phrase (‘final wh-phrase high’) and the F0 minimum at the auxiliary (‘auxiliary low’). This pitch range is larger in the Echo Tune (8.5 st) than in the Broad focus Tune (3.2 st) and the Narrow focus Tune (3.6 st). The large pitch range in the Echo Tune is mostly due to the very high F0 from the final syllable of the wh-phrase onwards. This is exacerbated by the low F0 in the area preceding the wh-phrase. The pitch range does not differ significantly between the Narrow focus Tune and the Broad focus Tune.

Another difference is that between the F0 maximum on the final syllable of the wh-phrase (‘final wh-phrase high’) (the focus in echo and narrow focus questions) and the F0 maximum on the final syllable of the utterance (‘ultimate high’). Recall that we measured this difference because narrow focus marking might result in similar values on the final syllable of the focus and the final syllable of the utterance (tone copying, see Section 2.5 above). As can be seen in Figure 8 above, the F0 maximum of these syllables is very similar in the Echo Tune and the Narrow focus Tune. The average difference between them is 0.6 st in the Echo Tune and only 0.1 st in the Narrow focus Tune. The difference is not especially small in the Broad focus Tune: on average 2.5 st. The difference between the Echo Tune and the Broad focus Tune, as well as the difference between the Narrow focus Tune and the Broad focus Tune, is significant, while the Narrow focus Tune and the Echo Tune do not differ significantly. The cause of the difference between the Narrow focus Tune and the Broad focus Tune is the higher F0 maximum on the final syllable of the utterance in the Narrow focus Tune (‘ultimate high’), since the F0 maximum on the final syllable of the wh-phrase (‘final wh-phrase high’) does not differ between these two tunes.

Finally, we measured the difference between the F0 maximum on the final syllable of the utterance (‘ultimate high’) and the F0 minimum of the penultimate syllable (‘penultimate low’), as an indication of the sentence-final pitch movement. This value is on average 3.4 st in the Broad focus Tune, 5.0 st in the Echo Tune and 5.3 st in the Narrow focus Tune. These values indicate the presence of a rise rather than a fall in all tunes. Still, the rise is significantly larger in both the Echo Tune and the Narrow focus Tune than in the Broad focus Tune, while it does not differ between the Echo Tune and the Narrow focus Tune. The larger rise in the Narrow focus Tune is again due to the higher F0 maximum on the final syllable of the utterance in the Narrow focus Tune, since the average F0 minimum of the penultimate syllable is the same in the Narrow focus Tune and the Broad focus Tune.

4.3 Comparisons of the three characteristic tunes regarding duration and intensity

In general, duration and intensity measurements were less informative than F0 regarding the differences between the three tunes. However, there are two observations to be made concerning duration (see also Tables A3 and A4 in the statistical appendix).

Firstly, the wh-word quel ‘which’ (

![]() $\overline{x}$

length = 203 ms in the Echo Tune) is significantly longer in the Echo Tune than in both other tunes (26 ms longer than in the Broad focus Tune and 28 ms longer than in the Narrow focus Tune). The wh-phrase as a whole also has longer duration in the Echo Tune (36 ms longer than the Broad focus Tune and 38 ms longer than the Narrow focus Tune). There is also some lengthening of the syllable preceding the wh-word (the final syllable of the participle) compared to the Broad focus Tune (9 ms longer).

$\overline{x}$

length = 203 ms in the Echo Tune) is significantly longer in the Echo Tune than in both other tunes (26 ms longer than in the Broad focus Tune and 28 ms longer than in the Narrow focus Tune). The wh-phrase as a whole also has longer duration in the Echo Tune (36 ms longer than the Broad focus Tune and 38 ms longer than the Narrow focus Tune). There is also some lengthening of the syllable preceding the wh-word (the final syllable of the participle) compared to the Broad focus Tune (9 ms longer).

Secondly, the final and penultimate syllables of the utterance are shortened in the Echo Tune. (On the penultimate syllable, this difference was

![]() $-$

12 ms compared to the Broad focus Tune and

$-$

12 ms compared to the Broad focus Tune and

![]() $-$

15 ms compared to the Narrow focus Tune; on the final syllable, the difference was

$-$

15 ms compared to the Narrow focus Tune; on the final syllable, the difference was

![]() $-$

26 ms compared to the Broad focus Tune.) The final syllable of the utterance is also shortened in the Narrow focus Tune (

$-$

26 ms compared to the Broad focus Tune.) The final syllable of the utterance is also shortened in the Narrow focus Tune (

![]() $-$

19 ms compared to the Broad focus Tune). The Narrow focus Tune and the Echo Tune pattern together on this syllable and do not differ significantly from each other.

$-$

19 ms compared to the Broad focus Tune). The Narrow focus Tune and the Echo Tune pattern together on this syllable and do not differ significantly from each other.

The role of intensity in distinguishing the three tunes is not very clear. We examined whether the Echo Tune had higher intensity than the other two tunes on the wh-word quel ‘which’ or the final syllable of the utterance, since this has been reported for German (Repp & Rosin Reference Repp and Rosin2015). However, this was not the case. The intensity on the wh-word in the Echo Tune was lower than in the Broad focus Tune (

![]() $-$

1.2 dB) and the Narrow focus Tune (

$-$

1.2 dB) and the Narrow focus Tune (

![]() $-$

1.1 dB) (see also Table A5 in the statistical appendix).

$-$

1.1 dB) (see also Table A5 in the statistical appendix).

In general, the sentences uttered with both the Echo Tune and the Narrow focus Tune displayed on average less intensity than the ones uttered with the Broad focus Tune (see Table A6 in the statistical appendix). Many different syllables in the Echo Tune and the Narrow focus Tune exhibited this lower intensity. They were situated in the pre-focal area, the post-focal area and the focus (the wh-phrase) itself, i.e. scattered across the sentence.

4.4 Summary of the results

In all three tunes, there is a high point associated with the end of the wh-phrase, followed by a fall on the PP. Also, there is at least a very small sentence-final rise. In the Echo Tune and the Narrow focus Tune compared to the Broad focus Tune, the pitch is lower in the area preceding the wh-phrase. There is also a strong similarity in pitch between the F0 maximum on the final syllable of the wh-phrase (the focus) and the F0 maximum of the final syllable of the utterance. The sentence-final rise is larger in these tunes. Also, the final syllable of the utterance has a shorter duration. Only in the Echo Tune, the F0 values are elevated from the final syllable of the wh-phrase onwards. As the pitch in the area preceding the wh-phrase is low, the pitch range is extremely large. In addition, the wh-word has a longer duration. The Echo Tune is not uttered with higher intensity. Finally, unique to the Narrow focus Tune is the absence of a high point on the wh-word quel ‘which’, or the presence of a point with a lower F0 value.

5 Discussion

We built our analyses on the sentences uttered with the characteristic tune of every condition: the 87% of the cases elicited in Condition A uttered with the Echo Tune, the 70% of the cases elicited in Condition B uttered with the Broad focus Tune and the 69% of the cases elicited in Condition C uttered with the Narrow focus Tune. Assuming that these tunes are representative of questions uttered in their respective discourse contexts, we now analyse their prosodic properties. In our discussion, we first single out the prosodic correlates of focus width (Section 5.1). We then discuss some general prosodic properties of information seeking wh-in-situ questions (Section 5.2). Finally, we point out the distinguishing prosodic features of echo questions (Section 5.3).

5.1 Prosodic correlates of focus marking: Focus in wh-in-situ questions

The common prosodic properties of echo questions and information seeking questions with a narrow focus on the wh-phrase confirm the presence of focus marking in French wh-questions and offer evidence in favour of the approach adopted here, following Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1984, Reference Jacobs1991), Beyssade (Reference Beyssade2006), and Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie & Marandin (Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie and Marandin2007). Our results also add to the existing knowledge of focus marking in French, providing insight into its prosodic correlates.

Firstly, the pitch in the area preceding the wh-phrase (the participle) is lower in echo questions and narrow focus information questions as compared to information seeking questions with broad focus. The participle is expected to be part of the focus in the broad focus questions, but precedes the focus in echo and narrow focus questions. Hence, this is evidence of pre-focal pitch compression, in line with findings by Touati (Reference Touati1987), Jun & Fougeron (Reference Jun, Fougeron and Botinis2000) and Dohen & Lœvenbruck (Reference Dohen and Lœvenbruck2004), but contra Beyssade et al. (Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Rialland2004b). In echo questions, pitch compression was also present on the auxiliary.

Next, the final syllable of the wh-phrase (the focus) and the final syllable of the utterance display the same F0 maximum: the average difference between these two values in an utterance was 0.1 st in information seeking narrow focus questions and 0.6 st in echo questions, but 2.5 st in broad focus questions. This is expected under current assumptions in the literature according to which a so-called illocutionary boundary tone at the end of a focus tends to be copied to the final syllable of the utterance. This boundary tone is in principle a low tone in declaratives and a high tone in interrogatives (see Section 2.5 and the references mentioned there). Our data show that the phenomenon also occurs in wh-in-situ questions. Moreover, they make clear that what is copied is not a high tone in an abstract sense, but an absolute F0 value: in (echo) questions with narrow focus on the wh-phrase, the F0 maximum on the final syllable of the utterance is an exact copy of the F0 maximum of the final syllable of the focus, defying declination, providing experimental support to the initial claim by Martin (Reference Martin1981).

In addition, the final syllable of the utterance has a shorter duration in both echo and narrow focus questions than in questions with broad focus. In echo questions, the penultimate syllable is also shortened. This shortening may well be a correlate of the copied tone, which has not, to our knowledge, previously been described in the literature.

5.2 Prosodic properties of French wh-in-situ information seeking questions

In interpreting the results regarding wh-in-situ information seeking questions, it should be taken into consideration that the items used in this experiment contained complex wh-phrases of the type quel N ‘which N’. This may have affected the results and further research will have to show whether the same prosodic descriptions apply to wh-in-situ questions with simplex wh-phrases, e.g. quoi ‘what’ or qui ‘who’. With this in mind, we turn to the prosodic properties of French wh-in-situ information seeking questions.

Regarding the prosody associated with the wh-phrase, both broad focus questions and echo questions exhibited an accent on the wh-word quel ‘which’, followed by a high point (a prosodic boundary) at the end of the wh-phrase. This is very similar to the results described in Gryllia et al. (Reference Gryllia, Cheng and Doetjes2016) (see also Wunderli Reference Wunderli1983). It differs from the results described in Baunaz & Patin (Reference Baunaz and Patin2009) and Baunaz (Reference Baunaz2016), who did not find an accent on the wh-word in questions similarly uttered following a topic change marker (see also Wunderli & Braselmann Reference Wunderli and Braselmann1980, Wunderli Reference Wunderli, Winkelmann and Braisch1982). A possible reason for this difference might be the relatively short wh-phrases and/or short target stimuli used in these studies, as compared to the ones used in Wunderli (Reference Wunderli1983), Gryllia et al. (Reference Gryllia, Cheng and Doetjes2016) and the current study.

In the narrow focus questions, the accent on the wh-word was either absent or significantly lower than in both broad focus and echo questions. The fact that the accent is diminished in the only condition where a contrastive topic precedes the utterance raises the question whether the lack of accentuation and the presence of the contrastive topic are related. A contrastive topic in French is associated with a high point, which Beyssade et al. (Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Rialland2004a, Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Riallandb) analyse as a pragmatic accent that they call a ‘C accent’. A C accent marks the use of a complex discourse strategy, such as a topic shift. The accent on in-situ wh-expressions has also been analysed as such a C accent. In sentences with several C accents, only one (usually the highest one in the syntactic tree) is obligatory (Beyssade et al. Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Rialland2004a, Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Riallandb). This is illustrated in (9), which contains an obligatory C accent on the contrastive topic le dimanche ‘on Sunday’ and an optional one on des cigarettes ‘cigarettes’.

This seems to fit the data of our experiment. If we assume, following Beyssade et al. (Reference Beyssade, Delais-Roussarie, Doetjes, Marandin and Rialland2004b), that the wh-word did not obligatorily receive an accent because of the preceding accent on the contrastive topic, this would explain why the high tone associated with the wh-word is diminished in questions elicited in this condition.Footnote [9]

We now turn to the final part of the utterance, which is relevant in light of the disagreement on whether or not French wh-in-situ questions display a large sentence-final rise. Previous authors have argued for the obligatory presence (Cheng & Rooryck Reference Cheng and Rooryck2000, Déprez et al. Reference Déprez, Syrett and Kawahara2013, Delais-Roussarie et al. Reference Delais-Roussarie, Post, Avanzi, Buthke, Di Cristo, Feldhausen, Jun, Martin, Meisenburg, Rialland, Frota and Prieto2015), optional presence (Wunderli & Braselmann Reference Wunderli and Braselmann1980; Wunderli Reference Wunderli, Winkelmann and Braisch1982, Reference Wunderli1983; Adli Reference Adli, Meisenburg and Selig2004, Reference Adli2006; Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo2016) and absence (Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Di Cristo1998; Starke Reference Starke2001; Mathieu Reference Mathieu2002, Reference Mathieu, Eguren, Fernandez-Soriano and Mendikoetxea2016; Tual Reference Tual2017) of such a rise (see Section 2.2). Recently, Reinhardt (Reference Reinhardt2019) has shown that French wh-in-situ questions have a tendency to display such a rise, but also that this is not a strict constraint. In accordance with Reinhardt’s findings, we only observed a prominent final rise in a part of the data.

A new observation made in this study is that the presence of a large sentence-final rise is correlated with focus width. Information seeking questions with broad focus displayed only a very small rise, while both echo and narrow focus questions displayed a rise with a larger pitch excursion, induced by the higher F0 values on the final syllable of the utterance in those tunes. In turn, these seem to be due to the tone copying phenomenon (see Section 5.1 above): in narrow focus questions, the high F0 maximum at the end of the focus gets copied to the final syllable, thus raising the pitch on the final syllable of the utterance. Therefore, our data show that the presence of a prominent sentence-final rise in French wh-in-situ questions may well be the result of narrow focus marking. This explains some of the disagreement in the literature: French wh-in-situ questions may or may not display a large sentence-final rise, depending on their focus structure.

5.3 Prosodic properties of French wh-in-situ echo questions expressing auditory failure

Following the attribution of some of the prosodic properties of echo questions to focus marking (Section 5.1), we are now in a position to shed light on the distinguishing features of French echo questions expressing auditory failure.

The F0 of echo questions is much higher than in information seeking questions (of either type), but only from the final syllable of the wh-phrase onwards. This is only partly consistent with Di Cristo’s (Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Di Cristo1998) and Boeckx’ (Reference Boeckx1999) statements, who describe echo questions as displaying a high pitch overall. The pitch difference from the final syllable of the wh-phrase onwards is very large: on average approximately 4 semitones. Apart from this elevation of the pitch, the utterance seems to perform the same tonal movements as in narrow focus information seeking questions. Since the area preceding the wh-phrase has low pitch (as in narrow focus questions), the pitch range within echo questions is enormous: on average 8.2 semitones.

Interestingly, the wh-word quel ‘which’ does not have higher pitch than in information seeking questions with broad focus. This is thus not a distinguishing feature of echo questions, despite previous claims (Chang Reference Chang1997: 17; Mathieu Reference Mathieu2002). However, both the wh-word (and the wh-phrase as a whole) and the preceding syllable are lengthened, as predicted by Engdahl (Reference Engdahl, Bonami and Hofherr2006). This longer duration is what distinguishes the wh-word in echo questions from that in broad focus information seeking questions.

A feature that is consistently mentioned in the previous literature as a property of echo questions in French is a sentence-final rise (e.g. Di Cristo Reference Di Cristo, Hirst and Di Cristo1998, Mathieu Reference Mathieu2002, Déprez et al. Reference Déprez, Syrett and Kawahara2013). Our findings confirm the presence of a rise, but show that the rise is not a distinguishing feature of echo questions. Moreover, although the pitch movement ends higher in echo questions, the rise does not seem to be larger when compared to information seeking questions with a similar focus width (i.e. narrow focus): the rise simply starts and ends higher. As suggested by González & Reglero (Reference González, Reglero, Repetti and Ordóñez2018) for Spanish, the impression of a more prominent rise in echo questions might have been caused by their larger pitch range. Also, as some previous studies have considered questions in which the wh-phrase was the final element of the utterance, the sentence-final pitch movement may in some cases have been confounded with the pitch movements associated with the wh-phrase.

French echo questions were not differentiated from information seeking questions by higher intensity, differently from in German (Repp & Rosin Reference Repp and Rosin2015). On the wh-word, echo questions had less intensity than both types of information seeking questions.

These results show that speakers of French mark echo questions with a prosody that is different from information seeking questions. A distinct prosody for echo questions has been established for various other (unrelated) languages as well (Section 2.3). However, the current study on French seems to be the first one that explicitly excluded focus width as a potential confound, thus strengthening the result. The existence of prosodic differences between echo questions and information seeking questions is in line with the presence of syntactic, semantic and pragmatic differences (Section 2.1) and indicate that echo questions should be regarded as a separate question type, with different properties from information seeking questions in all aspects of grammar.

Regarding the nature of the prosodic properties that set echo questions apart, we have raised the question whether a particular prosody marks echo questions cross-linguistically. In the languages studied so far, all prosodic descriptions of echo questions differ, but we tentatively proposed a generalisation based on the small available sample of languages (Section 2.3). We suggested that in languages with a falling sentence-final intonation in wh-in-situ information seeking questions (e.g. Farsi, Brazilian Portuguese), echo questions seem to display a rising sentence-final intonation, while in languages with a sentence-final rise (e.g. North-Central Peninsular Spanish, Greek, Shingazidja), echo questions seem to be marked by an expanded pitch range. This generalisation also holds for French, which falls neatly in the second category, with a sentence-final rise in both question types and an expanded pitch range in echo questions expressing auditory failure.

Although Sobin (Reference Sobin1990, Reference Sobin2010), in two influential papers, labelled the rising intonation of echo questions in general ‘surprise intonation’, our results show that surprise is not needed for echo questions to be marked with a particular prosody. It is a question for further research to what extent our findings will generalise to French echo questions expressing surprise. In some other languages in which both types of echo questions have been studied, their prosody was only subtly different, e.g. in American English and German (Bartels Reference Bartels1997, Repp & Rosin Reference Repp and Rosin2015). In other languages, the prosodic features of echo questions expressing surprise were mostly similar to those expressing auditory failure, but more pronounced, e.g. a more expanded pitch range, as in North-Central Peninsular Spanish (González & Reglero Reference González, Reglero, Repetti and Ordóñez2018) or uttered at a higher pitch register, as in in Shingazidja (Patin Reference Patin2011). In investigating this for French, it should be kept in mind that a larger pitch range can be a marker of surprise (Hirschberg & Ward Reference Hirschberg and Ward1992) or emotion in general (Bänziger & Scherer Reference Bänziger and Scherer2005), as well as one of the main features of French echo questions expressing auditory failure.

Summarising the discussion, the results of the study indicate that French wh-in-situ echo questions differ from broad focus information seeking questions in many ways. We analysed some prosodic features of echo questions, namely those that were also present in information seeking questions with narrow focus, as due to focus marking. An example of this is the tone copying phenomenon, resulting in a larger sentence-final rise in both question types with narrow focus. Other prosodic features were uniquely attested in echo questions. These were an elevated pitch from the final syllable of the wh-phrase onwards, resulting in sentences with an extremely large pitch range, and a lengthening of the wh-word quel ‘which’. Hence, French wh-in-situ echo questions expressing auditory failure are prosodically distinct from their information seeking counterparts, even when controlling for focus structure. In addition, the results demonstrate that focus is marked in French wh-in-situ questions.

6 Conclusions

The current study makes a direct comparison of French wh-in-situ echo and information seeking questions, controlling for the influence of focus on their prosodic properties. As the study targeted echo questions expressing auditory failure, the results are not confounded with the prosody associated with surprise. Broad focus information seeking questions display a high point associated with the wh-word, a high point followed by a fall (a prosodic boundary) at the end of the wh-phrase and a (small) rise at the end of the utterance. Echo questions expressing auditory failure share these characteristics, but their pitch is elevated from the final syllable of the wh-phrase onwards, resulting in a much larger pitch range. Also, the wh-word has a longer duration. French echo questions expressing auditory failure are not marked by higher intensity, nor by a sentence-final rise with a larger pitch excursion. These prosodic properties of French echo questions fall neatly in the tentative generalisation we proposed: in languages such as French, in which information seeking questions display a sentence-final rise, they are marked by an expanded pitch range. We conclude that echo questions display a prosody that is distinct from the prosody of information seeking questions, in addition to differences regarding their pragmatics, semantics and syntax. The fact that echo questions show different characteristics in all aspects of grammar sets them apart as a separate question type.

Furthermore, this study offers evidence for the presence of focus marking in French wh-in-situ questions. In particular, the pre-focal area is compressed, confirming Touati (Reference Touati1987) and Dohen & Lœvenbruck (Reference Dohen and Lœvenbruck2004), and the F0 maximum at the end of the focus is copied to the final syllable of the utterance (Martin Reference Martin1981). The current study shows that what is copied is not an abstract tone but an absolute F0 value, as already suggested by Martin (Reference Martin1981), but not experimentally tested so far. Moreover, the final syllable of the utterance is shortened. This confirms and adds to claims made in the literature on focus marking in French, while showing that we should not disregard information structural focus marking in (wh-)interrogatives.

STATISTICAL APPENDIX

Comparisons involving F0, duration and intensity

We only report the relevant comparisons. S.E. = standard error.

Table A1 Results of linear mixed effects models for F0 measurements with the Broad focus Tune as reference category.

Table A2 Results of linear mixed effects models for F0 measurement points with the Narrow focus Tune as reference category.

Table A3 Results of linear mixed effects models for duration with the Echo Tune as reference category.

Table A4 Results of linear mixed effects models for duration with the Narrow focus Tune as reference category.

Table A5 Results of linear mixed effects models for intensity with the Echo Tune as reference category.

Table A6 Results of linear mixed effects models for intensity with the Broad focus Tune as reference category.