1. Introduction

The use of future subjunctive (FS) has suffered a steady decline in written Spanish from the fourteenth century (Bosque, Reference Bosque2011), and this has been extensively studied across different regions in Spain and the Americas (Bello, Reference Bello1981; Bosque, Reference Bosque2011; Carrano-Schultheis, Reference Carrano-Schultheis2009; Granda, Reference De Granda1968; Hanssen & Alfonso, Reference Hanssen and Alfonso1966; Lenz, Reference Lenz1925; Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2002, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2007, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008; Veiga, Reference Veiga and Company-Company2006; Wright, Reference Wright1931). FS is now obsolete in Spanish given that present subjunctive can also express the hypothetical future (HF) in relative clauses, and both present indicative and imperfect subjunctive can do so in conditional protases (Alarcos, Reference Alarcos and Alarcos1949; Bello, Reference Bello1981; Lapesa, Reference Lapesa1985; Lloyd, Reference Lloyd1989). In everyday life, FS is still found chiefly in legal documents and contained in some traditional sayings such as a donde fueres, haz lo que vieres “when in Rome, do as the Romans do.” It has been claimed that the use of FS in embedded clauses might have been a dialectal variable in Spain, coming from Aragón rather than the Castilian lands (Keniston, Reference Keniston1937). In line with this, it has also been argued that FS was preserved in the oral Spanish of some populations from rural areas in Tenerife and La Palma (Canary Islands, Spain) (Bosque, Reference Bosque2011), the northern part of Colombia (Granda, Reference De Granda1968), northwest Venezuela, and other areas in Cuba, Santo Domingo, Puerto Rico, Ecuador, and Mexico (Sastre-Ruano, Reference Sastre-Ruano1997).

The Hispanic Caribbean regions in the Americas were considered impressionistically as more conservative in the use of FS against other regions in a southerly direction (see Granda, Reference De Granda1968). On the one hand, it was conjectured that the FS decline might have occurred uniformly for the written Spanish of the Americas, as it was claimed for places such as Puerto Rico, Mexico, Santo Domingo, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Chile, especially in the eighteenth century (Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008). On the other hand, the decline might have occurred gradually, not uniformly, and at a different pace in different regions from the Americas, given the possibility of having more conservative areas such as those in the Hispanic Caribbean countries, where FS was ostensibly more widely preserved (Granda, Reference De Granda1968). In spite of this, the spatial distribution of tabulations/proportions has not been explored thus far, and previous studies have not tested statistically either whether two different regions in the Americas exhibit the same distribution of tense-mood combinations used to convey the HF in written Spanish.

The present study is therefore intended: (1) to answer whether FS decline and substitution took place similarly across the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries in relative clauses and conditional protases; and (2) to understand the effects from two different dialects on the use of FS and other alternating forms. Proportions are visualized through geographic distributions, following Grieve, Montgomery, Nini, Murakami, and Guo (Reference Grieve, Chris Montgomery, Murakami and Guo2019), whereby this research is also a seminal work that combines current methods of dialectology with linguistic and sociohistorical facts to better understand FS decline in the Americas, particularly in the northwest and southwest of current Colombia, South America. The northern areas in Colombia are linked to the Caribbean Spanish and is apparently a conservative region in the use of FS (Granda, Reference De Granda1968), whereas the south covers unexplored geographic areas located closer to the Andean territories, all of which have not been sampled in diachronic studies of FS until now.

In order to solve the first objective, this study tries to provide an answer to the question whether the proportions of tense-mood combinations in the context of HF (i.e., FS, present subjunctive, imperfect subjunctive, present indicative) were equally likely to occur across the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries in relative clauses and conditional protases. Given that the second objective aims to find dialectal distinctions, the question to be answered is whether the proportions of FS and other alternating forms in northwest Colombia were equal to the proportions found in the south. To this end, proportions were tested statistically using the goodness-of-fit Chi-square analyses, while global and local spatial autocorrelation analyses were conducted to find nonrandom clusters and visualize geographic distributions of tense-mood combinations (see Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Chris Montgomery, Murakami and Guo2019).

Statistical analyses were conducted independently for both relative clauses and conditional protases, and tense-mood combinations conveying a HF meaning were excerpted from 45 legal documents written between the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, from the corpus Documentos para la Historia Lingüística de Colombia ‘Documents for the Linguistic History of Colombia’ (DHLC) (Ruiz-Vásquez, Reference Ruiz-Vásquez2019). This corpus comprises a series of legal documents from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries (Ruiz-Vásquez, Reference Ruiz-Vásquez2019) and offers an excellent opportunity to explore FS with geolocated data in Colombia. The documents were randomly sampled, and formulaic uses were excluded from the analyses.

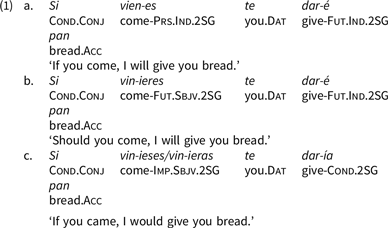

FS morphology was determined by the affix -re, being one of the forms to express the HF in Spanish. FS was used when referring to actions with prospective, unreal, and uncertain meaning, hence its function to convey the HF (Bello, Reference Bello1981; Carrano-Schultheis, Reference Carrano-Schultheis2009; Hansen, 1966; Lenz, Reference Lenz1925). FS contrasts with the real hypotheses expressed through the present indicative in conditional protases, as in the examples (1a) and (1b), and also contrasts with the imperfect subjunctive—due to their similar morphology and the uncertainty involved in any subjunctive mood correlated with a future meaning—as (1c) illustrates.

FS was not only restricted to occur in conditional statements because it was also found in relative clauses, functioning as adverb or noun (Veiga, Reference Veiga and Company-Company2006). Within this syntactic realm it alternated with the present subjunctive, which is also used to convey uncertainty and can be used prospectively, as illustrated in the contrast of (2a) and (2b).

The FS cantare ‘(that) I should sing’ was overtaken by the present subjunctive cante ‘(that) I sing’ in relative clauses (Bosque, Reference Bosque2011; Lloyd, Reference Lloyd1989; Penny, Reference Penny2002; Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008; Veiga, Reference Veiga and Company-Company2006), whereas the present indicative canto ‘I sing’ was preferred over FS in the protasis of conditional sentences (Bello, Reference Bello1981; Eberenz, Reference Eberenz and Bosque1990). Nevertheless, some authors (e.g., Alarcos, Reference Alarcos and Alarcos1949; Cano-Aguilar, Reference Cano-Aguilar1992; Gili-Gaya, Reference Gili-Gaya1973; Lapesa, Reference Lapesa1985; Rojo and Montero, Reference Rojo and Montero1983) have also considered that the imperfect subjunctive cantase/cantara ‘(if) I sang’ was the tense by which FS was originally replaced in this context, given its proximity in meaning to the uncertainty expressed with FS (Cano-Aguilar, Reference Cano-Aguilar1992, Reference Cano-Aguilar1993).

Even though FS has been used much longer in written Spanish, mainly in legal documents within formulaic expressions like most subjunctive tenses in Spanish (Silva-Corvalán, Reference Silva-Corvalán1994), it fell into disuse in written documents from the fourteenth century in Peninsular Spanish, showing a drastic decline in the mid-sixteenth century (Bosque, Reference Bosque2011; Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2002, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008). Despite this, FS in the Americas does not seem to have mirrored the proportions and decline in Peninsular Spanish for the sixteenth century. Granda (Reference De Granda1968) posited a conservative Hispanic area covering Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Atlantic coasts in South America, from Panama in the west to Venezuela in the east, where FS was apparently more frequently used. He also argued that its use tended to be less frequent or almost rare in Ecuador, Bolivia, Perú, or Chile. It is worth noting that his claims were not statistically grounded given the paucity of appropriate technology for geographic analyses, but his causal foundation was well documented.

Interestingly, tabulations of FS have also been reported in written Spanish from the Andean territory of Bolivia in the sixteenth century, between 1572 and 1598 (Mendoza, Reference Mendoza and Hernández Alonso1992), whereas in areas such as the Río de La Plata (Argentina) and Chile, FS was notoriously used in the seventeenth century (Fontanella de Weinberg, Reference Fontanella de Weinberg1987; Matus, Dargham & Samaniego, Reference Matus, Dargham, Luis Samaniego and Hernández Alonso1992). It all leads to believe that FS use and decline in written Spanish might not have taken place uniformly in written Spanish, as its use has apparently emerged and dropped in different periods and regions. Ramírez-Luengo (Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008:150) has considered that the disappearance of FS has been rather uniform across the Americas, claiming that a large number of occurrences were found in mutually distant places such as Puerto Rico, Mexico, Santo Domingo, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Chile in the eighteenth century. However, in more conservative regions such as Uruguay or Argentina, it was preserved until the mid-nineteenth century. He sampled documents written in Central America, from 1703 to 1758, specifically in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua, and has found that FS should have undergone the same substitution process throughout the Americas in the eighteenth century.

Yielded results here demonstrate that the proportions of FS and present subjunctive were not equally likely across the four centuries in relative clauses, which proves statistically that FS decline and substitution occurred in the nineteenth century for relative clauses, from legal documents of current Colombia. However, proportions from conditional protases did not mirror relative clauses. Furthermore, the study failed to reject the conjecture that the proportions of FS and other alternating forms in northwest Colombia were equal in the south, because the spatial distributions were equally likely in both regions. These results are in line with the idea that FS should have disappeared uniformly from the written Spanish in the Hispanic countries of the Americas but suggest, in contrast, that the substitution did not occur at a similar pace for each type of clause. These distinctions may come from stylistic purposes imprinted by writers who chose one combination over the other, as will be discussed later.

In what follows, Section 1.1 describes how the expression of hypothetical future has developed from its referents in Latin up to the nineteenth century in Peninsular Spanish and the Americas. Section 1.2 sets the background for the research questions and the characteristics of the present study. Section 2 presents the methodology, corpus, extraction protocol, the description of the variables involved in the study, and provides a brief description on spatial autocorrelation analyses. Section 3 contains results for both relative clauses and conditional protases. Section 4 discusses why the use of FS should not be regarded as a dialectal feature and highlights the differences for FS decline and substitution in relative clauses and conditional protases. Finally, Section 5 concludes with some remarks on the diachronic and dialectal study of FS in the Americas.

1.1 The emergence and decline of Spanish future subjunctive

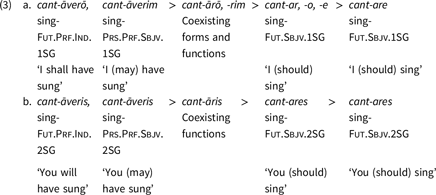

Although FS did not exist in Latin, the morphosemantic confusion for the expression of the hypothetical future (HF) might have originated here (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd1989; Penny, Reference Penny2002). The future perfect indicative cantāverō ‘I shall have sung’ and the present perfect subjunctive cantāverim ‘I (may) have sung’ would have merged triggering the origin of the FS in Spain. FS, along with present subjunctive, present indicative, or imperfect subjunctive, was one of the grammatical forms used to express the HF. Its development is illustrated in (3a). The semantic merge was expected in Latin as both tenses, the future perfect indicative (cantāveris) and the present perfect subjunctive (cantāveris), shared the same stem and suffix, as presented in (3b). The conjugation of the FS for the first person singular developed differently given that it might have emerged from the coexistence of cantārō, -rim when Latin was spoken in Spain, while the coexistence of cantar, -o, -e would be expected for Old Spanish as shown in (3a). These coexisting forms were fully merged into cantare in Modern Spanish, as can be observed in the reconstruction presented in (3a). The merge of both the future perfect indicative and the present perfect subjunctive has therefore involved the adoption of new functions from which FS, as the expression of the HF, has apparently emerged (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd1989; Penny, Reference Penny2002).

While Latin was spoken in Spain, the merging of i, e > e, as in cantāris > cantares for (3b) was, on the one hand, the key to determine the form of FS in Old Spanish but, on the other hand, has also obscured the morphological distinction of FS with the imperfect subjunctive because both of these tense-mood combinations used the affix -re (Bosque, Reference Bosque2011; Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff1991). One important caveat is that subjunctive tenses are virtual, could then be used prospectively to refer to future, and imperfect subjunctive can therefore convey a future meaning (Sastre-Ruano, Reference Sastre-Ruano1997). The substitution of the imperfect subjunctive cantares ‘(if) you sang’ by cantāvissēs ‘(if) you had sung’ is illustrated in (4).

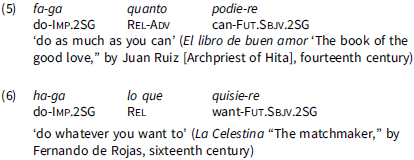

In view of the above, there could have been instances for cantares to be used with the future perfect indicative meaning “you will have sung,” or with the present perfect subjunctive meaning “you (may) have sung,” inducing the semantic confusion as different functions were linked to one verbal morpheme. All of these circumstances gave cause for the emergence of the FS form to express the HF. In Old and Modern Spanish, FS occurred mainly in relative clauses with adverbial or nominal functions as in (5) and (6), as well as in conditional protases, such as (7).

Some studies (e.g., Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2002; Wright, Reference Wright1931) argue that the decline of FS in written documents from Peninsular Spanish came during the Golden Age (i.e., the seventeenth century). Others, on the contrary, have shortened this period setting the limits around the end of the fifteenth century and the mid-sixteenth century, when FS should have ostensibly disappeared from the speech of lower classes, being primarily used by courtesans and gentlemen with a high stylistic value during the Golden age (e.g., in Bosque, Reference Bosque2011; Luquet, Reference Luquet1988). However, this assumption was recently challenged as it is also believed that the evidence is scarce to claim that FS was truly used in oral Spanish. Instead, it is argued that FS was not necessarily used in oral Spanish because other tenses were equally used to express the same meanings of FS; its use was then essentially stylistic for written Spanish (Solomon, Reference Solomon2007).

The ratios of FS occurrences in literature and legal documents were growing through the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, while the decline is said to be more drastic from the eighteenth century (Penny, Reference Penny2002; Wright, Reference Wright1931). Therefore, the substitution of the FS by the present subjunctive in relative clauses, or by the present indicative and the imperfect subjunctive in conditional protases, in the Americas should more clearly be observed in written Spanish from the eighteenth century, as the tabulation ratios are expected to decrease after this century, as Ramírez-Luengo (Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008) argued. Granda (Reference De Granda1968) alludes to the occurrence of FS in written documents from La Palma, in the Canary Islands, Spain, and attempted to connect a straight path for ultramarine use of FS from the Atlantic of Spain to the Atlantic in the Americas, coming from west Andalucia (Spain). Despite that, there is evidence that the use of future indicative in prospective and contingent subordinated clauses was preferred over FS in Andalucia (Herrero, Reference Herrero, Ariza-Viguera and Cano-Aguilar1992; Lapesa, Reference Lapesa1985).

The Canary Islands have had a historical connection with the Caribbean lands in the Americas, due to the route for the conquest of America and the phonetic similarities shared by these areas (Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2007; Zuluaga, Reference Zuluaga2016). Thus, the assumption that Caribbean lands were more conservative in the use of FS could be hypothetically related to the connection with La Palma, but not with Andalucia. According to Bosque (Reference Bosque2011), the Atlantic areas in the new continent as well as the rural areas in the Canary Islands have preserved FS longer than other regions in Spain. Veiga (Reference Veiga and Company-Company2006), on the other side, argued that the FS form was not preserved and was not alive in the Canary Islands and suggested that the likely preservation of this tense needed more research chiefly throughout the Americas. Caribbean areas such as Santa Marta and Cartagena de Indias (both in Colombia) have historically had an intense contact with Spain (Granda, Reference De Granda1968). The Province of Cartagena de Indias was indeed considered as the main town from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries in current Colombia. This was one of the most important ports for the receipt/issue of goods from/to Spain, and the slave trade led by the Portuguese (Navarrete, Reference Navarrete, Schwegler, Kirschen and Maglia2017).

Ramírez-Luengo (Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008) has claimed that the use of FS for the written Spanish in the Hispanic Caribbean lands should not be regarded as more conservative than other geographic areas in the Americas, because its prevalence has been attested in documents throughout the XVI and XVII centuries in distant regions from Mexico, Ecuador and Chile (Cartagena, Reference Cartagena2002; Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2007; Sánchez-Méndez, Reference Sánchez-Méndez1997). Consequently, the decline has also been predicted for the second half of the eighteenth century in Chile and Buenos Aires (Argentina) (Cartagena, Reference Cartagena2002; Fontanella de Weinberg, Reference Fontanella de Weinberg1987), and throughout the nineteenth century in Uruguay and Santa Fé (Argentina) (Donni de Mirande, Reference Donni de Mirande2004; Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2002). The decline of FS was then postponed to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries arguing that the substitution might have occurred uniformly, as it disappeared at the same pace across the Hispanic Americas (Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008:150). Notwithstanding this, more evidence is needed in order to consider the Atlantic areas as more conservative regions in the use of the FS than other areas in the Americas. The answer to this conjecture may certainly shed some light to better understand the influence of peninsular varieties of Spanish on the use of FS in the Americas.

1.2 The current study

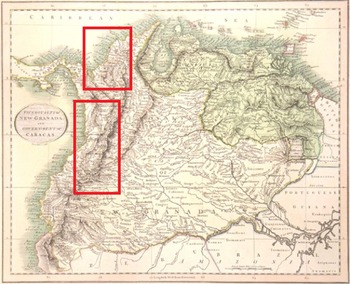

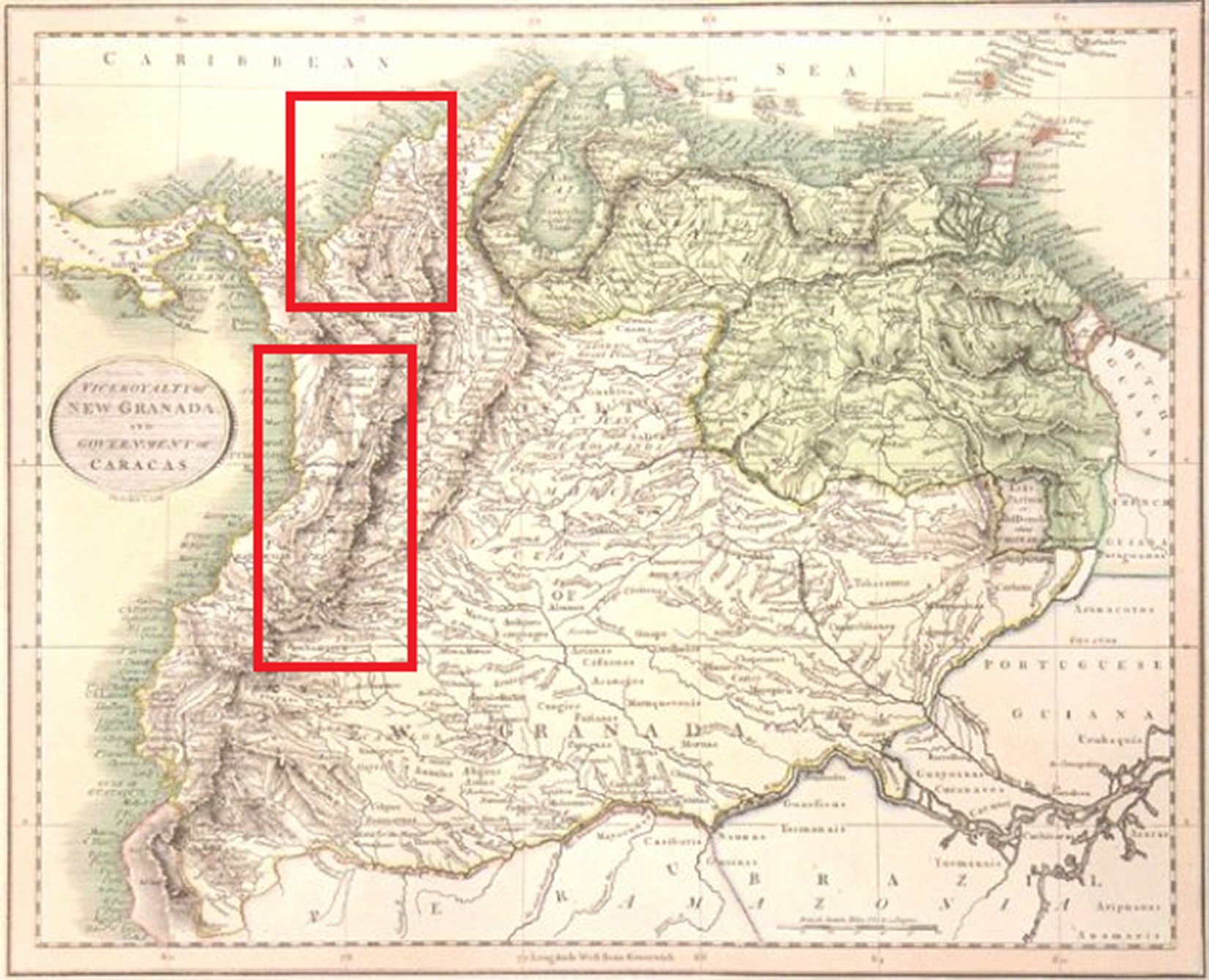

The idea of considering the Hispanic Caribbean areas as more conservative in the use of FS than other places in the Hispanic Americas requires a follow-up study, as this hypothesis has never been confirmed. This paper brings a more controlled study on the expression of hypothetical future (HF) and is intended to provide a follow-up to the Granda’s (Reference De Granda1968) work by comparing northwest and southwest Colombia, known as the Viceroyalty of New Granada throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This Viceroyalty was part of the conquered areas taken over by Spain in the Americas and was administered initially by the government of Cartagena and Santa Marta in the north, and the government of Popayán in the south (both areas are illustrated in Map 1). Since historical linguistic research in Colombia is scarce and most studies have looked at synchronic rather than diachronic phenomena (Ruiz-Vásquez, Reference Ruiz-Vásquez2013), this study is also a contribution to the paucity in diachronic analyses for the Spanish spoken in Colombia. The aim of this paper is to deepen our current understanding of FS decline and substitution in Spanish across time in two different regions, northwest and southwest Colombia (see Map 1).

Map 1. The northwest and southwest areas of the Viceroyalty of New Granada covered by the chosen documents of the corpus DHLC. (Image adapted from www.claseshistoria.com)

This study follows the principles of the variationist framework that observes one linguistic variable comprised in a set of alternate ways of expressing the same thing (Labov, Reference Labov1972). It applies the methods used in Poplack (Reference Poplack, Bybee and Hopper2001) and Poplack et al. (Reference Poplack, Rena Torres Cacoullos, Rosane de Andrade Berlink, Lacasse, Steuk, Ayres-Bennett and Carruthers2018) for the study of subjunctive in Romance languages. FS cantare ‘(that) I should sing’ is therefore the linguistic variable alternating with present subjunctive cante ‘(that) I sing’ in relative clauses, and with present indicative canto ‘(if) I sing,’ and imperfect subjunctive cantase/cantara ‘(if) I sang’ in conditional protases. These tense-mood combinations are used in Spanish to convey the HF meaning. The alternations were observed across the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, while global and local spatial autocorrelation analyses were conducted following Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Guo, Kasakoff and Grieve2016) and Grieve et al. (Reference Grieve, Chris Montgomery, Murakami and Guo2019).

This paper assumes that present subjunctive has alternated and coexisted with FS in relative clauses, whereas present indicative and imperfect subjunctive have alternated and coexisted with FS in conditional protases (Bosque, Reference Bosque2011; Lloyd, Reference Lloyd1989; Penny, Reference Penny2002; Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008; Veiga, Reference Veiga and Company-Company2006). Once the testing contexts were determined, the two fundamental questions to be answered are: (1) Were the proportions of future subjunctive (FS) occurrences and the proportions of other alternating forms equally likely in the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries?; and (2) Were the proportions of FS and the alternating forms in northwest Colombia equal to the proportions in southwest Colombia in each century? Research questions were tested in both relative clauses and conditional protases, and following the latest findings from Ramírez-Luengo (Reference Ramírez-Luengo2002, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2007, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008), the present study hypothesized that: (H1) The decline and substitution of FS should be apparent from the eighteenth century, whereby FS proportions are expected to be significantly lower from this century in both relative clauses and conditional protases; and that (H2) FS decline and substitution should have been uniform in northwest and southwest Colombia, exhibiting equal proportions in the two areas.

2. Methodology

The corpus and extraction protocol are described below, as well as the criteria used to perform the quantitative and spatial autocorrelation analyses. For the purpose of this analysis and its interpretation, this section describes the expression of HF as the dependent variable, while the independent factors comprise the century (the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries) and the geographic area (northwest and southwest Colombia). Two independent analyses were conducted following this model, one for relative clauses and one for conditional protases.

2.1. The corpus and extraction protocol

Data were obtained from the corpus Documentos para la Historia Lingüística de Colombia ‘Documents for the Linguistic History of Colombia’ (DHLC), which is a series of legal documents written from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries in the current territory of Colombia in South America (Ruiz-Vásquez, Reference Ruiz-Vásquez2019). The corpus comprised hitherto 194 documents, all of which were divided into 25 documents from the sixteenth century, 46 documents from the seventeenth century, 92 documents from the eighteenth century, and 31 documents from the nineteenth century. A remediation for the disproportion of documents available in the sixteenth century was done by randomly sampling 45 documents for all the centuries, which allowed for approximately 15,000 words per century. The documents in each century consist of about 7,500 words written in places from northwest Colombia, and about 7,500 words written in southwest Colombia, as Table 1 illustrates. Then, a total of 60,852 words were covered for all the explored centuries.

Table 1. Number of words per geographic area by century. The number of sampled documents added up to complete a similar amount of words appears in parenthesis

These documents are written records of legal procedures executed against indigenous people and African slaves. They also include complains about some abuses from landlords and authorities, as well as letters stating regulations coming from the government and members of the Spanish encomienda (i.e., a labor and administration system established by the Spanish crown on local communities). The documents reside in the Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica (2019) ‘National Center for Historical Memory’ in Colombia.

Documents were transcribed paleographically, accounting for graphemes, stains, wrinkles, cuts, and insertions. In addition to this, each document has a critical presentation that is an adaptation of the paleographic version showing more transparently the content of the legal document. It is worth noting that the critical presentation also preserves the variation of graphemes, as in the case of the conjunction si ‘if’ in conditional protasis, which was also found as ci or zi in critically transcribed documents. Both the paleographic transcription and the critical presentation have been completed and saved in plain text by a specialized paleographer. The study used the critical presentation because the orthographic variability was not altered, and it made morphosyntactic queries and data cleaning easier. The text files with critical presentation were then systematically cleaned as the informative marks, such as those indexing page number, signs, signatures, stains, interlinear text, and margins were removed with a specific code written in the R environment (R Core Team, 2020). Tokens were obtained and counted using AntConc 3.5 (Anthony, Reference Anthony2019), a freeware corpus analysis toolkit for text analysis.

The first part of the search began by finding all the instances of FS in the documents using the affix -re, as this string signals FS conjugation. The search discriminated documents coming from the southwest and the northwest, and excluded formulaic occurrences of FS similar to, among others, sepan cuantos esta carta de poder vieren ‘know all persons who should see this letter of power.’ The search had the purpose of retrieving all FS occurrences in relative clauses and conditional protases and tracking matrix verbs for relative clauses as in Poplack et al. (Reference Poplack, Rena Torres Cacoullos, Rosane de Andrade Berlink, Lacasse, Steuk, Ayres-Bennett and Carruthers2018) and Torres-Cacoullos et al. (Reference Torres-Cacoullos, LaCasse, Johns and De La Rosa Yacomelo2017). Matrix verbs are verbs governing relative clauses, and were the main parameter to accomplish more objective searches for those forms alternating and coexisting with FS in relative clauses, namely, present subjunctive, present indicative, and less transparently imperfect subjunctive. Matrix verbs may co-occur with different tense-mood combinations in the relative clause, which constitutes the variation frame for a variationist study (Poplack et al., Reference Poplack, Rena Torres Cacoullos, Rosane de Andrade Berlink, Lacasse, Steuk, Ayres-Bennett and Carruthers2018). Priority was given to those matrix verbs with two or more alternating forms in the relative clause (see Appendix A), and, following this criterion, fifteen matrix verbs were chosen: mandar ‘to command,’ ser ‘to be,’ dar ‘to give,’ hacer ‘to do,’ decir ‘to tell,’ estar ‘to be,’ hallar ‘to find,’ querer ‘to want,’ sacar ‘to take out,’ tener ‘to have,’ edificar ‘to build,’ guardar ‘to keep/save,’ pagar ‘to pay,’ traer ‘to bring,’ and volver ‘to come back.’

The verbs in conditional protases, on the other hand, exhibited a less regular co-occurrence with the same tense and mood in the apodosis. Therefore, FS competitors were found using solely the conjunction si ‘if,’ setting the variation frame within the boundaries of the protasis. It is worth noting that the use of si to find instances of HF has additionally required queries, including orthographic variants such as ci, si, zi, sino, and si no. Thus, the analysis on conditional protases has not considered matrix verbs from relative clauses, being a totally independent analysis. These rigid parameters have resulted in considering only 96 occurrences of FS and 97 of other alternating forms (i.e., present indicative, present subjunctive, and imperfect subjunctive) in relative clauses, while 28 occurrences of FS and 29 occurrences of other tense-mood combinations (i.e., present indicative and imperfect subjunctive) were tabulated in conditional protases, which guarantees the least ambiguous information system for this study. Eventually, 250 tokens were collected from 45 documents in 60,852 words. These proportions were contrasted with those found by Wright (Reference Wright1931), who reported 3,551 FS occurrences from the eleventh to the twelfth century in 580,000 lines of prose and poetry. In average, FS occurred in 0.6% of all the lines studied by Wright (Reference Wright1931), whereas this paper presents an average of 0.4% of HF instances in 60,852 words. This was expected due to the fact that the variation frame, restricted to the co-occurrence of alternating forms with the same matrix verb in relative clauses, has reduced the tokens to include primarily equally comparable tense-mood combinations.

2.2 Dependent variable: The hypothetical future

The dependent variable is the expression of hypothetical future (HF), and there are four alternatives to express this, namely, future subjunctive (FS), present subjunctive, present indicative, and imperfect subjunctive. However, some of them have more clear-cut interpretations than others. The examples from (8) to (11) were found in the DHLC corpus and serve to illustrate each alternative within the variation frame of relative clauses. The present subjunctive acudamos in (9) can thus be exchanged for the FS acudiéremos, while the present indicative deben in (10) can be exchanged for the FS debieren. This was also the case of the imperfect subjunctive ubiesen in (11) with the FS hubieren, despite the fact that in this case the meaning of past could perfectly be implied. Finally, (8) with the FS fuere illustrates a slot of HF filled in with FS, governed by the matrix verb mandar.

The alternatives to express the HF in conditional sentences comprise three possibilities: future subjunctive (FS), present indicative, and imperfect subjunctive. The examples from (12) to (14) were also obtained from the corpus DHLC and are intended to illustrate each one of the alternatives. The case of the present indicative se remedia in (13) can be exchanged by the FS se remediare, and the imperfect subjunctive pasase in (14) can be replaced by the FS pasare with no change in the original meaning.

2.3 2.3 Independent variables

2.3.1 Century

Given that this study moves across the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, this timeline could not be conceived separately from the historical events that have occurred within the current territory of Colombia and have given the social context for the sampled documents. Thus, while the fifteenth century has marked the arrival of Spaniards in the Americas in 1492, the sixteenth century represents not only the acquisition of the land and richness but also the consolidation of the Spanish colony in the Americas. The Spanish kingdom raised the Viceroyalty of New Spain in 1535. Mexico was the capital, and it took over the current territories in the South of United States, Mexico, and Central America. The Viceroyalty of Peru would then be established eight years later in 1543, having control over the Andean regions of South America, Panama, and the Río de la Plata (Argentina) (Vives, Reference Vives2004).

The current area of Colombia was under the administration of the Viceroyalty of Peru during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, having Cartagena de Indias (northwest Colombia) in a southerly direction from Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic) as the bridge to connect Central America with South America. The cities of Santa Marta and Cartagena were founded in 1525 and 1533 respectively, in the northwest of current Colombia (Uribe Ángel, Reference Uribe Ángel, Gil and Torras2002). In the beginning of the sixteenth century, the incipient city of Cartagena consisted of 800 neighbors, some of whom were war males, coming from Santo Domingo, and travelers who had just arrived from Spain. The population of the city, however, had also integrated a variety of travelers since 1573, from businessmen and employees to Portuguese immigrants (Rodríguez-González, Reference Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Enrique Rodríguez-Baquero, Luz Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Humberto Borja-Gómez, Ceballos-Gómez, Uribe-Celis, Murillo-Posada and Arias-Trujillo2011).

Cartago and Popayán, cities in the southwest of current Colombia, were also under the surveillance of the Viceroyalty of Peru. Popayán was besieged and subdued by Sebastián de Belalcázar in 1537, and represented the connection with the city of Quito (Ecuador) through a place called Villaviciosa de Pasto (San Juan de Pasto, Colombia). Cartago, on the other hand, was founded later by Jorge Robledo in 1540 (Uribe Ángel, Reference Uribe Ángel, Gil and Torras2002). Both Popayán and Cartago had strategic fields to the pursuit of gold and minerals. Popayán, in particular, was more important between 1680 and 1800 for being the central town to supervise gold extraction in the region of Quibdó (Chocó, West Colombia). During this period, Popayán and Cartago were among the main destinations for slaves brought by Portuguese, French, and English companies as workforce for gold extraction. At the same time, Popayán was the recipient of different goods such as textiles and ceramics imported from Quito passing through the city of San Juan de Pasto. Cartago connected Cartagena and Santa Fe with Popayán, and the southwest with Quito, in current Ecuador (Rodríguez-González, Reference Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Enrique Rodríguez-Baquero, Luz Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Humberto Borja-Gómez, Ceballos-Gómez, Uribe-Celis, Murillo-Posada and Arias-Trujillo2011).

By the first half of the eighteenth century, certainly from 1717, the Viceroyalty of New Granada was raised in order to control and unify the territories of New Granada (Colombia), Quito (Ecuador), and Caracas (Venezuela). Provinces in northwest Colombia, such as Santa Marta and its neighbor Cartagena, were fully devoted to commerce and slavery, as well as those in southwest Colombia, such as Popayán (Cauca) and Cartago (Valle del Cauca), albeit these latter were devoted to the extraction of gold and minerals. Cartagena de Indias was of such importance in this century that even when Santafé de Bogotá was chosen as the capital of the Viceroyalty of New Granada, Cartagena gave the fight to be the capital itself and hosted the viceroy (Borja-Gómez, Reference Borja-Gómez, Enrique Rodríguez-Baquero, Luz Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Humberto Borja-Gómez, Ceballos-Gómez, Uribe-Celis, Murillo-Posada and Arias-Trujillo2011). This is a piece of evidence to illustrate the strategic position of Cartagena as a commercial center to trade with goods from both the peninsula and the Americas, being the most important city during the Viceroyalty of New Granada in the eighteenth century (Calvo-Stevenson & Meisel, Reference Calvo-Stevenson and Meisel2005).

As the extraction of gold decayed in the second half of the eighteenth century, the central territories mostly used for gold extraction in southwest Colombia went into a recession (Borja-Gómez, Reference Borja-Gómez, Enrique Rodríguez-Baquero, Luz Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Humberto Borja-Gómez, Ceballos-Gómez, Uribe-Celis, Murillo-Posada and Arias-Trujillo2011). However, all of them, Cartagena, Santa Marta, Cartago, and Popayán had participated actively in cultural events and meetings, from which the independence movements would eventually emerge at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Once Caracas (Venezuela) conformed its own government in the beginning of the nineteenth century, Cartagena was the first city to declare its independence from the Spanish crown within the current territory of Colombia, and soon enough Santafé de Bogotá would declare its own independence as well.

Interestingly, when independence from Spain was finally declared and maintained in the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Real Audiences of Santa Marta (northwest) and San Juan de Pasto (southwest) rejected the newly autonomous government, and both of them expressed their loyalty to the Spanish crown—although they would later conform the territories that had embraced and recognized the independence (Uribe Ángel, Reference Uribe Ángel, Gil and Torras2002). All of these facts have framed the character of each city and constitute the historical context in which the legal documents observed here were written and issued. Social differences between southwest and northwest are apparent, and we can also see them from the economic activities developed in each region: extraction of gold and other minerals in the south, while the north had the main ports to commerce.

2.3.2 Geographic region

Even though the southwest part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada (currently Colombia) has been historically differentiated from the northwest part, the legal documents coming from the cities framed within these two geographic areas share the same legal establishment. The geographical features associated with each region describe the Andean mountains for those places located in the southwest of the Viceroyalty of New Granada, while the proximity to the Caribbean Sea is linked to those lands located in the Northwest, as illustrated in Map 1.

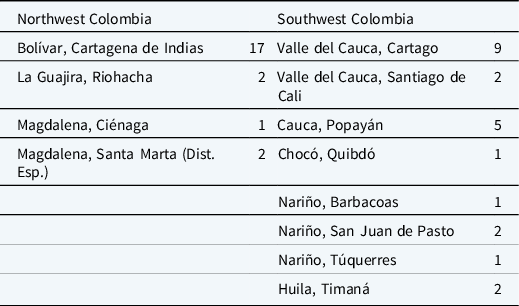

In order to predict and contrast the likelihood of two representative hotspots for the use of FS in northwest and southwest Colombia, this study concentrates the analyses around two different Spanish dialects: (1) the Caribbean dialect whose main representative city was Cartagena de Indias, in the department of Bolívar, located in northwest Colombia; and (2) the west neogranadino dialect whose main representative cities, serving the purpose of this study, are Cartago and Santiago de Cali, in the department of Valle del Cauca, and Popayán, found within the neighboring department of Cauca, as underlined locations in Table 2 illustrate (see Ruiz-Vásquez, Reference Ruiz-Vásquez2020).

Table 2. Locations (Department, City) with the number of sampled documents in front. Given the high concentration of legal documents in Cartagena de Indias (Northwest Colombia), the underlined locations in Southwest Colombia comprise one hotspot to be compared with Cartagena de Indias

Other nonunderlined locations were strategically chosen for being close to the core places and help to better account for spatial clustering if there were any. Cartagena and Cartago have been historically differentiated for their people and the economic activities, as detailed in Section 2.3.1. Even if Cartago was not deemed to hold the same importance as Cartagena, it represented, at a fundamental level, the character and lifestyle in southwest Colombia, along with its neighbors Santiago de Cali, Popayán, Quibdó, Barbacoas, San Juan de Pasto, Túquerres, and Timaná (see Table 2).

2.4 Spatial autocorrelation analyses

The spatial autocorrelation analyses compared locations from northwest and southwest Colombia and have required to build a nearest neighbor spatial weights matrix (NNSWM) from normalized frequencies, using the R function nb2listw (Kelejian & Prucha, Reference Kelejian and Prucha2010; Tiefelsdorf, Griffith & Boots, Reference Tiefelsdorf, Griffith and Boots1999). This approach was developed to meet the first law of geography: “Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things” (Tobler, Reference Tobler1970). Hence, pairs of locations that are close together were weighted higher than those that are distant. Geographic proximity was determined by setting the nearest neighbors to seven, and assigning higher weights to them as noted on Grieve (Reference Grieve, Martijn Wieling, Van Noord and Bouma2017).

The analyses involve first a global spatial autocorrelation analysis that follows Grieve et al. (Reference Grieve, Chris Montgomery, Murakami and Guo2019) and is intended to determine the spatial autocorrelation present for each tense-mood combination (future subjunctive, present subjunctive, present indicative, and imperfect subjunctive) within the two geographic regions. This first step was performed independently for each century in relative clauses and conditional protases, while Moran’s I statistic has informed whether there is any nonrandom autocorrelation present among all locations. Therefore, the technique calculates Moran’s I under randomization assumption (Bivand & Wong, Reference Bivand and Wong2018), which is used to confirm whether the spatial distribution of relative frequencies in tense-mood combinations have resulted from random spatial processes or not. Moran’s I statistic ranges from -1 to +1, thereby nonrandom clusters are to manifest through positive values, dispersion with negative values, and randomness around zero (Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Chris Montgomery, Murakami and Guo2019).

Second, a local spatial autocorrelation analysis was also performed and was used to predict and visualize potential dialectal clusters as hot spots for the locations listed in Table 2. The analysis follows Grieve (Reference Grieve, Martijn Wieling, Van Noord and Bouma2017) as it implements the Getis-Ord Gi* statistical technique (Getis & Ord, Reference Getis and Keith Ord1992; Ord & Getis, Reference Keith and Getis1995). It compares local (one location and its surrounding locations) and global (all locations taking together indiscriminately) averages with the use of Getis-Ord Gi* z-scores revealing high or low value clusters, hot and cold spots respectively. The NNSWM was the basis for this analysis, while visualization of maps was achieved in R with localG calculation (Bivand, Reference Bivand and Wong2018; Getis & Ord, Reference Getis, Keith Ord, Longley and Batty1996; Ord & Getis, Reference Keith and Getis1995).

3. Results

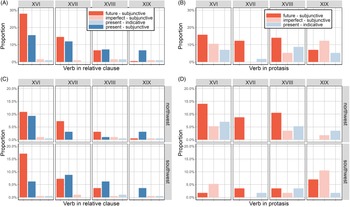

In order to know whether the proportions of FS and other alternating forms were equally likely across the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, the goodness-of-fit Chi-square analyses were conducted. The first analysis tested whether the proportions found for relative clauses (presented in Figure 1A) were equally likely in each century. Yielded results predict that at least one proportion is different in each century, but this is expected given the rare cases of imperfect subjunctive and present indicative in relative clauses used with a HF meaning (see Appendix B). However, when proportions of only FS and present indicative were compared, the analysis predicted that they were significantly different for both the sixteenth century (X 2 (1, N = 84) = 6.8571, p = 0.008829) and the nineteenth century (X 2 (1, N = 14) = 10.286, p = 0.001341), as higher tabulations of FS were found in the sixteenth century, while these were drastically lower in the nineteenth century.

Figure 1. Tested proportions for the verbs of relative clauses and conditional protases with the meaning of hypothetical future.

The second analysis, on the other hand, tested whether the proportions found in conditional protases (presented in Figure 1B) were equally likely to occur for each century. In this case, the analysis has predicted that the proportions of each tense-mood combination were equally likely for all the centuries observed, except the seventeenth century (X 2 (2, N = 8) = 10.75, p = 0.004631). This result is including the zero occurrences of imperfect subjunctive (see Figure 1B), but when this datum was excluded, that is, when proportions of only FS and present indicative were tested, the analysis yielded significant results. This proves that proportions in conditional protases were different in the seventeenth century (X 2 (1, N = 8) = 4.5, p = 0.03389). It must be noted that two raw frequencies are being compared here, seven occurrences for FS and one for present indicative.

In addition to this, another set of analyses was conducted aiming to know whether the proportions of FS and the other alternating forms in northwest Colombia were equal to the proportions in the southwest for each century. I anticipate that these analyses have failed to reject the hypothesis that the proportions of FS and the other alternating forms (illustrated in Figure 1C) were equal in the two areas. This holds true even after comparing the proportions of only FS and present subjunctive (see Appendix B). Therefore, the analysis did not yield statistical evidence to claim that at least one proportion of FS or present subjunctive in relative clauses is different in any of the two areas.

The proportions in conditional protases (shown in Figure 1D) have mirrored the results from relative clauses. However, the analysis does not provide a statistical result for the difference of proportions in the seventeenth century when the zero occurrence of imperfect subjunctive was included (X 2 (2, N = 8) = NA, p = NA), and when this datum was excluded, the analysis did not yield significant results either. The proportions of FS and present indicative in conditional protases were not different in northwest and southwest Colombia in the seventeenth century (X 2 (1, N = 8) = 1.904762, p = 0.1675463). In the same way as relative clauses, the data once again do not provide evidence to consider that the alternating forms used to convey HF in conditional protases were different in any of the two areas (see Appendix B).

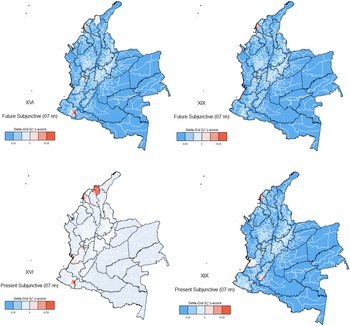

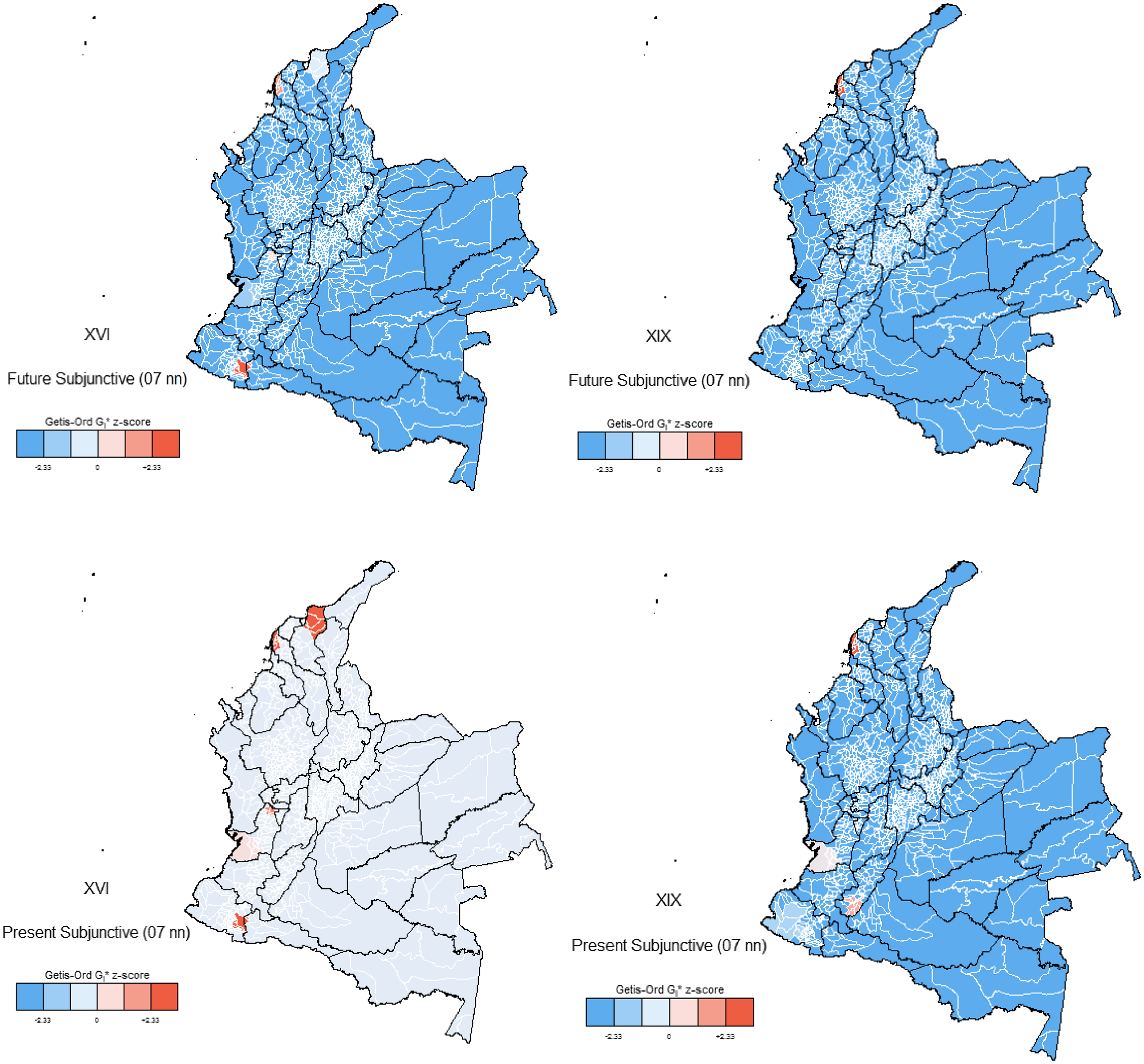

Map 2 shows the alternation of FS and present subjunctive for relative clauses in documents from the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries. The proportions were different in these centuries: The documents exhibited significantly more FS tabulations in the sixteenth century (X 2 (1, N = 84) = 6.8571, p = 0.008829), while higher tabulations of present subjunctive were observed instead in the nineteenth century (X 2 (1, N = 14) = 10.286, p = 0.001341). As mentioned previously, the data do not reflect that the use of FS, in contrast to the present subjunctive in relative clauses, was a dialectal variable in the sixteenth century either (X 2 (1, N = 84) = 3.455726, p = 0.06303303), and this was true also in the nineteenth century.

Map 2. Alternation of future and present subjunctive for relative clauses in the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries.

In order to better understand the geographic distributions of these results, a spatial clustering of these proportions was visualized in Map 2 using spatial autocorrelation analyses (see Grieve et al., Reference Grieve, Chris Montgomery, Murakami and Guo2019). In this regard, yielded Moran’s I statistic demonstrates that the spatial clustering is chiefly limited and is not expected to generalize in both relative clauses and conditional protasis (see Appendix C). Map 2 illustrates the use of FS and present subjunctive for relative clauses in legal documents written in the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. As observed before, the proportions of FS and present subjunctive were different in the sixteenth century primarily because there were more occurrences of FS, mainly in the south. Map 2 reflects that the spatial clusters of FS are similar in both the north and south primarily for the cities of Cartagena de Indias and San Juan de Pasto respectively (Moran’s I = 0.14).

However, the geographic distribution of present subjunctive exhibited a wider cluster in the north (see XVI, Map 2) given the proportions found in the city of Ciénaga, Magdalena, a neighbor of Cartagena de Indias (Moran’s I = 0.15). On the contrary, the spatial clusters of FS in relative clauses were almost nonexistent in legal documents from the nineteenth century, except for Cartagena de Indias, in the north (Moran’s I = 0.014, see Map 2). Clusters of present subjunctive have therefore prevailed over FS in northwest and southwest Colombia, despite the fact that they are small frequencies (Moran’s I = 0.13, see Appendix C).

The spatial distributions presented in Map 2 suggest that present subjunctive was more used than FS (Moran’s I = 0.014) in both the north and south during the nineteenth century (Moran’s I = 0.13, see Appendix C). Present subjunctive therefore exhibited hotspots in northwest and southwest Colombia, in this century, whereas FS showed only one hotspot in the north. However, FS and present subjunctive proportions from the north were equally likely to occur in the south (X 2 (1, N = 14) = 1.08, p = 0.2993869).

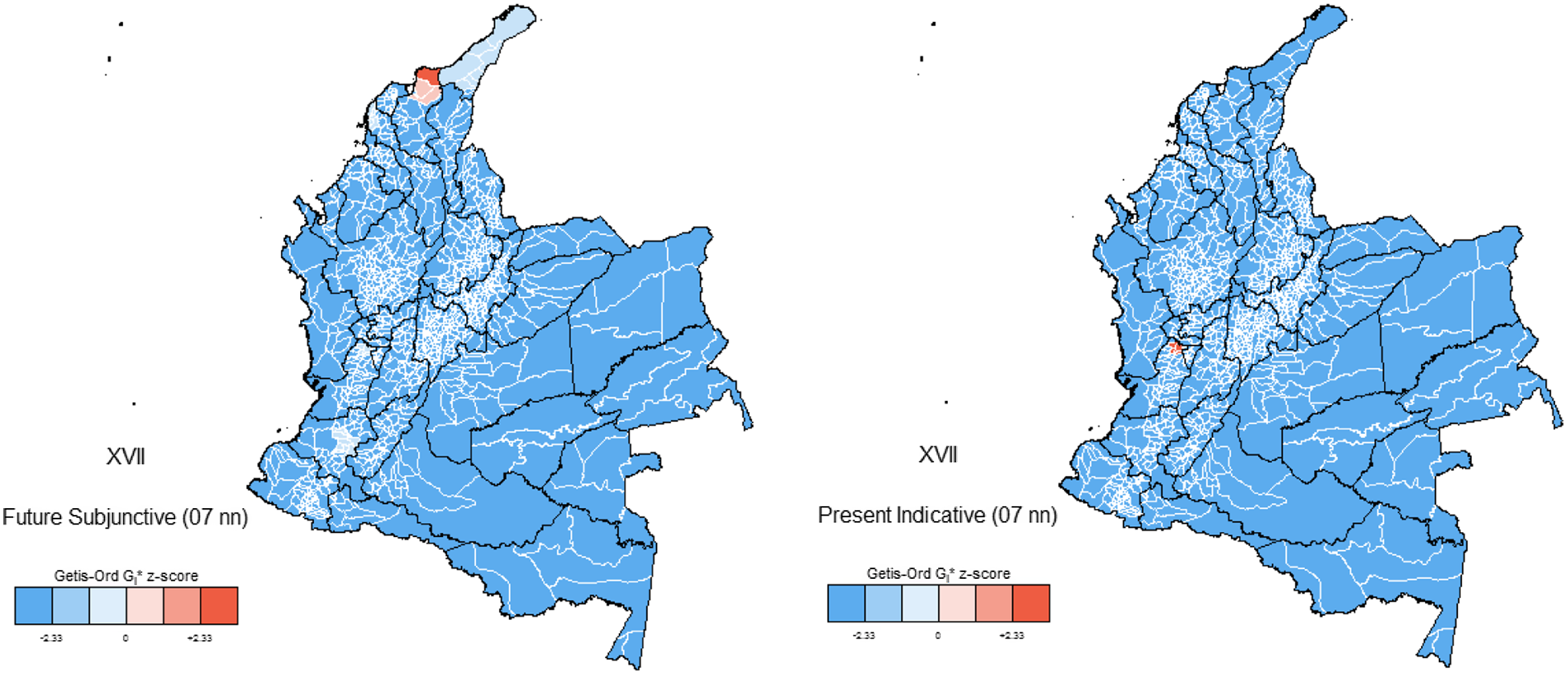

Map 3 shows the alternation of future subjunctive and present indicative for conditional protases in the seventeenth century (see Appendix E for all centuries). Interestingly, the alternations found in the sampled documents suggest that at least one proportion among FS, imperfect subjunctive, or present indicative was different. Given that there were no occurrences of imperfect subjunctive, this zero proportion could be the different proportion (X 2 (2, N = 8) = 10.75, p = 0.004631). However, when testing the likelihood of proportions from only FS and present indicative, the analysis also yielded significant results suggesting that, in the seventeenth century, the proportions of FS were different, as tabulations of FS were significantly higher (X 2 (1, N = 8) = 4.5, p = 0.03389).

Map 3. Alternation of future subjunctive and present indicative for conditional protases in the seventeenth century.

The spatial analysis predicts also a slightly higher clustering correlation for FS in the seventeenth century (see Map 3), which was due to the tabulations found in Santa Marta (Dist. Esp., north). In either case, the correlation was very low (Moran’s I = 0.17), albeit this cluster was higher than the other clusters observed (see Appendix C). As stated before, the analysis failed to reject the idea that FS is not a dialectal variable also in the context of conditional protases. Not even in the seventeenth century, when only FS and present indicative were compared (X 2 (1, N = 8) = 1.904762, p = 0.1675463).

Yielded results have demonstrated that the alternation of FS and present subjunctive in relative clauses was equally likely in northwest and southwest Colombia, which was also the case for the alternation of FS with present indicative and imperfect subjunctive in conditional protases. Therefore, there is no statistical evidence to consider that FS was a dialectal variable in legal documents from west Colombia. Furthermore, the tabulations found in the sample suggest that writers used more FS in the sixteenth century, but more present indicative in the nineteenth for their relative clauses with hypothetical future (HF) meaning. It implies then that the alternation of FS and present subjunctive was equally likely in both the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries. Notwithstanding this, the alternation of FS with present indicative and imperfect subjunctive was equally likely in the sixteenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, in conditional protases. Noteworthy is the lack of use of imperfect subjunctive and paradoxically the scarce use of present indicative in the seventeenth century (see Appendix C). The proportion of FS was thus significantly higher in the seventeenth century, which makes a difference between these two types of clauses, conditional protases, and relative clauses.

4. Discussion

In Spain, it was considered that the use of FS in embedded clauses might have been a dialectal variable coming from Aragón rather than the Castilian lands (Keniston, Reference Keniston1937), but there the evidence is scarce to consider that the use of FS was certainly a dialectal feature (Solomon, Reference Solomon2007). The present study tested whether two different regions, northwest and southwest Colombia, exhibited dialectal differences for the expression of the HF, where FS is included. Results are in line with the idea that FS is not a dialectal feature. Granda (Reference De Granda1968) suggested that dialectal differences for the use of FS in the Hispanic Caribbean countries were due to the transatlantic connection with La Palma, in the Canary Islands (Spain). Moreover, differences between Caribbean dialects and the east/west neogranadino dialects, or the Andean dialects, have been well attested (see Montes, Reference Montes1982; Mora et al., Reference Mora, Mariano Lozano, Espejo and Duarte2004; Ruiz-Vásquez, Reference Ruiz-Vásquez2020), but the legal documents observed here do not exhibit these regional departures at least for the use of FS in relative and conditional clauses.

These documents were issued by different notaries in the northwest and southwest of the Viceroyalty of New Granada (currently Colombia). As Section 2.3.1 described, northwest Colombia had an intense contact with Central America in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (Uribe Ángel, Reference Uribe Ángel, Gil and Torras2002), and Central America was part of the territories ruled by the first Spanish Viceroyalty dated from 1535, the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Vives, Reference Vives2004). Historians agree on the fact that Cartagena de Indias was a strategic focus for the intense contact between Spain and the Americas, as well as for slavery trade, and for being scenario of great disputes (Calvo-Stevenson & Meisel, Reference Calvo-Stevenson and Meisel2005; Navarrete, Reference Navarrete, Schwegler, Kirschen and Maglia2017; Rodríguez-González, Reference Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Enrique Rodríguez-Baquero, Luz Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Humberto Borja-Gómez, Ceballos-Gómez, Uribe-Celis, Murillo-Posada and Arias-Trujillo2011; Uribe Ángel, Reference Uribe Ángel, Gil and Torras2002). In addition to this, the northwest was settled by businessmen, employees, and Portuguese immigrants since 1573 (Rodríguez-González, Reference Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Enrique Rodríguez-Baquero, Luz Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Humberto Borja-Gómez, Ceballos-Gómez, Uribe-Celis, Murillo-Posada and Arias-Trujillo2011) probably giving rise to more regulations. Hence a much more intense flow of legal documentation might be expected from the north primarily in the sixteenth century, opening the door to find more instances in which FS could have been used.

Still and all, the Spanish crown controlled southwest regions within not much more than four or seven years after the foundation of Cartagena, when Popayán and Cartago were founded in the south. The southwest gained increasing importance until the end of the seventeenth century in 1680, when cities such as Cartago and Popayán and the area in the department of Chocó became core territories to the pursuit of minerals (Rodríguez-González, Reference Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Enrique Rodríguez-Baquero, Luz Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Humberto Borja-Gómez, Ceballos-Gómez, Uribe-Celis, Murillo-Posada and Arias-Trujillo2011). Even though dialectal and socioeconomic differences were apparent, and despite that there probably was a more intense flow of legal documents in the north, the use of FS in legal documents does not reflect major departures on the writing of notaries from these two different areas. As mentioned before, northwest and southwest regions have been historically connected as slaves were also acquired in the north and brought to the south to work in mines, and textiles as well as ceramics were imported from Quito and used to pass through Pasto and Cartago, in the southwest, and were brought later to the north (Rodríguez-González, Reference Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Enrique Rodríguez-Baquero, Luz Rodríguez-Gonzalez, Humberto Borja-Gómez, Ceballos-Gómez, Uribe-Celis, Murillo-Posada and Arias-Trujillo2011). Thereafter, differences in the legal writing from northwest and southwest Colombia could not be derived from the use of FS, which implies that the legal Spanish writing in the southwest was not lagging or evolving behind the north during the Viceroyalty of New Granada.

Results therefore support the thesis of Ramirez-Luengo (2008) who claims that the decline of FS has been rather uniform across the Americas and has undergone the same substitution process. However, instead of associating the FS substitution with dialectal distinctions, this paper provides preliminary evidence to claim that differences manifested from the types of clause where FS was used. Results suggest that FS was more likely used in the conditional protases of written documents in the seventeenth century, differing substantially from the sixteenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. In addition to this, in relative clauses, FS was as equally likely to occur as present subjunctive in the documents from the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries, given that FS proportions were higher in the sixteenth century, and lower in the nineteenth century. This leads us to conjecture whether FS could have lived longer in some clauses than others.

However, there should be a reason for the high tabulations of FS in conditional protases during the seventeenth century in the sampled documents. It occurred in both northwest and southwest Colombia, namely, in Cartagena de Indias, Santa Marta, and Riohacha, in the north of Colombia, and in Cartago and Popayán, in the south. The years associated with these documents ranged from 1618 to 1653, the first half of the seventeenth century. The occurrence of present indicative came also from a document in the first half of the century. As described before in Section 2.3, Cartago and Popayán gained importance in the second half of the century, which could have made the flow of legal documentation be more intense, and notaries could have used more FS. Despite this, the increment for the use of FS was not observed in the sampled documents after the first half of the seventeenth century, because this tense-mood combination was as equally likely to occur as present indicative or imperfect subjunctive in conditionals in the subsequent centuries. This study therefore did not find any connection between the use of FS in conditional protases during the first half of the seventeenth century and any particular event that might have triggered an increase for its use. The occurrences do not seem to have any other trait in common other than the hypothetical future meaning for a condition in the context of prosecution, as observed from (15) to (17):

The use of FS has been claimed to be primarily used with a high stylistic value during the Golden age for the oral Spanish of courtesans and gentlemen (e.g., in Bosque, Reference Bosque2011; Luquet, Reference Luquet1988). In addition to this, it was also considered stylistic for Spanish literature, as writers used it arbitrarily and probably to give a more emphatic effect (Solomon, Reference Solomon2007). In Spanish legal language, FS is still used in spite of the fact that other alternating forms are widely accepted. As a result, the possibility that notaries, all of whom have written the legal documents presented here, had to choose FS over present subjunctive, in relative clauses, or over present indicative or imperfect subjunctive, in conditionals, seem to indicate that they wanted to imprint one particular style in their writing, by adding a more emphatic effect.

Although the Gramática de la Lengua Castellana ‘The Castilian language grammar’ by Antonio de Nebrija (Reference de Nebrija1492) did not prescribe the use of Spanish writing during the centuries observed here, the writers were lax to follow writing rules even after the publication of this Gramática (Spaulding, Reference Spaulding1943). This is therefore consistent with the occurrence of imperfect subjunctive and present indicative within relative clauses from the sampled documents of this study (see sentences [10] and [11]), and supports the idea that FS was used to imprint a special writing style which might have been more preserved in conditional protases. As mentioned earlier in Section 1.1, FS was substituted by present subjunctive in relative clauses (Bosque, Reference Bosque2011; Lloyd, Reference Lloyd1989; Penny, Reference Penny2002; Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008; Veiga, Reference Veiga and Company-Company2006), but this has always been competing with other forms that convey the same meaning, the HF, and tend to be more colloquial, for instance, present subjunctive in relative clauses (Paden, Reference Paden1998; Solomon, Reference Solomon2007). Notaries without grammatical rules to comply with had thus the possibility to use FS, present subjunctive, present indicative, or much more opaquely, the imperfect subjunctive in relative clauses (see examples 8–11), but the colloquial form, present subjunctive, displaced the stylistic used of FS in the nineteenth century in the present data. However, it seems that notaries anchored the stylistic use of FS for more time in conditional clauses.

This study argues that FS and present subjunctive ceased to be equally likely to occur in relative clauses until the nineteenth century, when higher tabulations of present subjunctive were found. In these data, the decline therefore was steady as FS was more used in the nineteenth century, as equally used as present subjunctive in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and much less likely to occur in the nineteenth century. Ramírez-Luengo (Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008:150) claimed that FS decline became evident from the eighteenth century, and that there have been other places such as Uruguay or Argentina where it was preserved until the mid-nineteenth century, but results here do not provide evidence to argue that FS decline was more notorious in the eighteenth century for relative clauses. Legal documents have shown instead that FS tabulations dropped significantly in the nineteenth century in contrast to present subjunctive.

It is worth noting that the present study failed to reject that the proportions of FS were as equally likely to occur as the proportions of imperfect subjunctive or present indicative, in conditional protases, in the eighteenth century (see Appendix B). Ramírez-Luengo (Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008:153) claimed that in this century FS was chiefly restricted to occur in relative clauses given the low tabulations in conditional protases. He suggested then that his finding served to prove how the use of FS was weakening in this century. Results here have also demonstrated that FS had more tabulations in relative clauses than conditional protases, but using the variationist framework (Labov, Reference Labov1972), when other alternating forms that were competing with FS were observed, allowed for a different interpretation of this finding. In spite of the fact that there were less occurrences of FS in conditional protases across these data, FS, imperfect subjunctive and present indicative equally occurred in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in conditional protases. In contrast, FS occurred significantly less for relative clauses in the nineteenth century. Taking together these findings, results suggest that FS was more used in conditional protases than relative clauses. Then, FS decline was not evident in the nineteenth century in conditional protases, but it was in relative clauses.

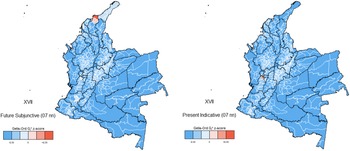

Thus, it was not a surprise to run into spatial clusters of FS from southwest Colombia during the nineteenth century in conditional protasis, as with the case of Huila, Timaná (see Appendix E, XIX, future subjunctive) or FS clusters in the north for relative clauses being weighted higher in the seventeenth century than the sixteenth century (see Appendix D). All of these occurrences, in tandem with the failure to predict significant differences between northwest and southwest Colombia in the expression of the HF, might support the uniform hypothesis for the decline, but it does not seem to be uniform, at least in legal documents from Colombia, because the substitution might have occurred earlier in relative clauses.

5. Conclusions

The FS decline and substitution on legal documents seem to have been uniform in northwest and southwest Colombia from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Furthermore, FS has clustered indistinctly, being used in northwest and southwest Colombia. Granda (Reference De Granda1968:11) observed that the most conservative regions in the use of FS were colonized earlier than nonconservative areas drawing attention to the impact of colonization in northwest Colombia, in the Caribbean. However, southern regions in current Colombia were colonized sooner after the colonization of the main cities in the north, Santa Marta and Cartagena de Indias. Thereby, the use of FS in legal documents does not seem to have been affected by divergent socioeconomic activities, taking place in both the north and the south. In this respect, the socioeconomic growth might not account for the variance in FS tabulations within the expression of the hypothetical future. Notwithstanding this, more replication studies are needed with a much larger corpus of data, because the statistics on the spatial autocorrelation analyses (Moran’s I) exhibited very low correlation among localities. Even so, these analyses are of great importance because they involve parameters used in geographical studies that dialectologists are now implementing, as they help understand spatial distributions of linguistic forms beyond the mere raw tabulations.

In addition to this, considering that the substitution of FS in the current territory of Colombia has occurred in the eighteenth century, as has been claimed for Puerto Rico, Mexico, Santo Domingo, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Chile (Ramírez-Luengo, Reference Ramírez-Luengo2008), is certainly inaccurate. Proportions of FS and present subjunctive were not significantly different in relative clauses in the eighteenth century, and the proportions of FS, present indicative, and imperfect subjunctive in conditional protases either. Therefore, the two critical centuries in this study were: (1) The seventeenth century, due to the significant tabulations of FS in conditional protases; and (2) the nineteenth century, because present indicative substituted FS in relative clauses in the sampled documents. Hence, the uniform hypothesis used to explain FS decline and substitution requires control for the type of clause, as it seems to be that the substitution occurred at different times in conditionals and relative clauses.

With respect to the context of occurrence, the present study highlights the use of matrix verbs to explore FS in embedded clauses, because it has been of great help to avoid false positives. However, the variation context for the HF and the conjunction si ‘if’ in conditional protases is not fully specified and requires further study, as the alternating tense-mood combinations might co-occur more frequently with other verbs in the apodosis in different corpora.

Not having an extensive list of alternations is furthermore a limitation. In this study, the variation frame for relative clauses was restricted to the co-occurrence of alternating forms with the same matrix verb, thereby accuracy and quality of data were improved, but not quantity. Because of this, the spatial autocorrelation analyses are certainly not expected to be generalized as can be inferred from Moran’s I values (see Appendix C). Despite that, this study has demonstrated that there is no evidence to consider the FS as a dialectal feature and that the timespan for FS decline and substitution differs between relative clauses and conditional protases. FS proportions were less likely to occur for the former and were as equally likely to occur as other alternating forms for the latter in the nineteenth century, but there is no apparent motivation for this difference, except that it was used in legal documents primarily for its emphatic and stylistic effects.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the help of Prof. Néstor Fabián Ruiz for having shared his corpora to diachronic and dialectal studies, and special thanks to Prof. Patricia Gubitosi for her guidance, support, suggestions, and clarifications throughout this study.

Appendices

A. List of Governors in the infinitive form searched on the DHLC Corpus

Desear ‘to wish’

Acudir ‘to resort to’

Admitir ‘to admit’

Apelar ‘to appeal’

Asentir ‘to consent’

Cesar ‘to cease’

Cobrar ‘to charge’

Constar ‘be certain’

Cumplir ‘to obey’

Dar ‘to give’

Decir ‘to tell’

Declarar ‘to declare’

Dejar ‘to stop’

Denegar ‘to deny’

Dignar ‘to deign’

Edificar ‘to build’

Ejecutar ‘to execute’

Embargar ‘confiscate’

Enfermar ‘to get sick’

Enviar ‘to send’

Estar ‘to be’

Examinar ‘to inspect’

Faltar ‘to break’

Fenecer ‘to end’

Guardar ‘to save’

Haber ‘to exist’

Hacer ‘to do’

Hallar ‘to find’

Ir ‘to go’

Jurar ‘to swear’

Llevar ‘to carry’

Mandar ‘to command’

Nombrar ‘to designate’

Obligar ‘to oblige’

Pagar ‘to pay’

Pasar ‘to trespass’

Poder ‘can’

Poner ‘to put’

Presentar ‘to show’

Pretender ‘to pretend’

Proceder ‘to proceed’

Procurar ‘to ensure’

Prometer ‘to promise’

Quebrantar ‘to break’

Quedar ‘to remain’

Querer ‘to want’

Recibir ‘to receive’

Reducir ‘to reduce’

Relevar ‘to substitute’

Repartir ‘to distribute’

Saber ‘to know’

Sacar ‘to take out’

Secuestrar ‘to kidnap’

Ser ‘to be’

Servir ‘to serve’

Sobrevenir ‘to occur’

Suceder ‘to happen’

Tener ‘to have’

Tomar ‘to take’

Traer ‘to bring’

Volver ‘to return

B. Descriptive statistics of Chi-square analyses

C. Descriptive statistics of spatial autocorrelation analysis for future subjunctive and other alternating forms

D. Complete alternation of tense/mood combinations in relative clauses

E. Complete alternation of tense/mood combinations in conditional protases