1. Introduction

2020 has seen the toppling of statues, the defacing of monuments, mass protests about street names and calls for the renaming of army barracks. The semiotic furor harnessed by the #BlackLivesMatter movement has brought to the fore the potent symbolism of commemoration as it is inscribed in the public cityscape. More generally, the current debates about memorial hegemony in the citytext present us with a vivid illustration of the performative power of changing denotation: the public elimination of the discredited ideology functions as a powerful mechanism to obliterate the geographical traces of “the memory [and the legacy] of … [a] former [world view and/or] regime” (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu2012:387). Civic linguistic acts of renaming therefore simultaneously demonstrate and contribute to the end of one bygone era and the beginning of a new one.

When ideologies change due to “ruptures in political history” (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu1997:481), the material carriers of memory in the semiotic landscape need to be (re)constructed for the commemorative needs of the new present. The renaming of urban features (bridges, streets, neighborhoods, even whole cities) is often the civic consequence of such shifts in Weltanschauung. As Lefebvre (Reference Lefebvre1991:54) has aptly pointed out “a social transformation, to be truly revolutionary in character, must manifest a creative capacity in its effects on daily life, on language and on space.” In this light, commemorative toponymic (re)naming should be seen as the outcome of a complex interplay of forces, including the creation of memory, the indexing of officially sanctioned identity and ideology as well as the appropriation of human space.

Similar to other Eastern European countries that have seen changes in state ideology, commemorative (re)naming in Germany has been indexing fluctuations in political Weltanschauung: the encroachment of Nazi henchmen (Göring, Göbbels, Himmler, etc.) in the years following Hitler’s takeover in 1933, Soviet influence after WWII resulting in street names such as Stalinallee (‘Stalin avenue’) or Leninstraße (‘Lenin street’), etc. The fall of the Communist regime in 1989 and the subsequent political transformation leading to reunification (known as the Wende),Footnote 1 “brought with it the eradication of socialist ideology from the semiotic landscape” (Buchstaller et al., Reference Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese, Schneider, Ziegler and Marten2021). While contemporary scholarship has yet to fully grasp the complex and often highly localized post-Wende naming strategies, commemorative renaming is ongoing. Consider for example the recent memorialization (in Leipzig in 2015) of Capastraße after the famous photojournalist Robert Capa, who photographed an American soldier killed shortly before the end of WWII in this street (the famous “last man to die” picture).

To date, however, there is no research that attempts to sketch the historical dimension of street renaming in Eastern Germany across the political turmoil that characterized the last century. The lion’s share of Azaryahu’s work explores renaming during individual political eras (such as Nazi Germany or the GDR; see Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu1986, Reference Azaryahu1997, Reference Azaryahu2011a, Reference Azaryahu2012 inter alia) and it predates more recent attempts to redress some of the injustices of the past as it is currently enshrined in public memorialization. Also, none of the critical toponomy research on Eastern Europe engages with cutting-edge geovisualization methods that allow exploring the spatiality of such name changes.

Our project aims to fill these gaps by quantitatively investigating toponymic turnover in Leipzig,Footnote 2 a large city in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), now the eastern part of Germany, across the entire past century (1916–2018). By investigating commemorative street (re)naming processes as reflexive and simultaneously constitutive of consecutive waves of political ideological orientation, the present paper aims to develop a comprehensive model of longitudinal changes in commemorative toponymy. Our analysis relies on a mixed methods approach that draws on geographical visualization, linguistics landscape, and variationist epistemologies. Triangulating changes in the commemorative streetscape with historical archival material gives us the opportunity to examine the complex processes underlying ideologically driven changes in commemorative street (re)naming.

Unlike traditional LL studies, we propose to systematically include the analysis of spatial metrics typically employed in geographical analysis. By providing a longitudinal quantitative perspective on the diachronic processes at play in Leipzig’s geosemiotic textuality, our research transcends static street name repositories. The overall objective of this article is thus to open new horizons on the ways in which “landscape and identity, social order and power” (Rubdy, Reference Rubdy, Rudby and Ben Said2015:2) have been linked across the past hundred years by illustrating these complex processes in one Eastern European city.

2. Changing state ideologies in Eastern Germany

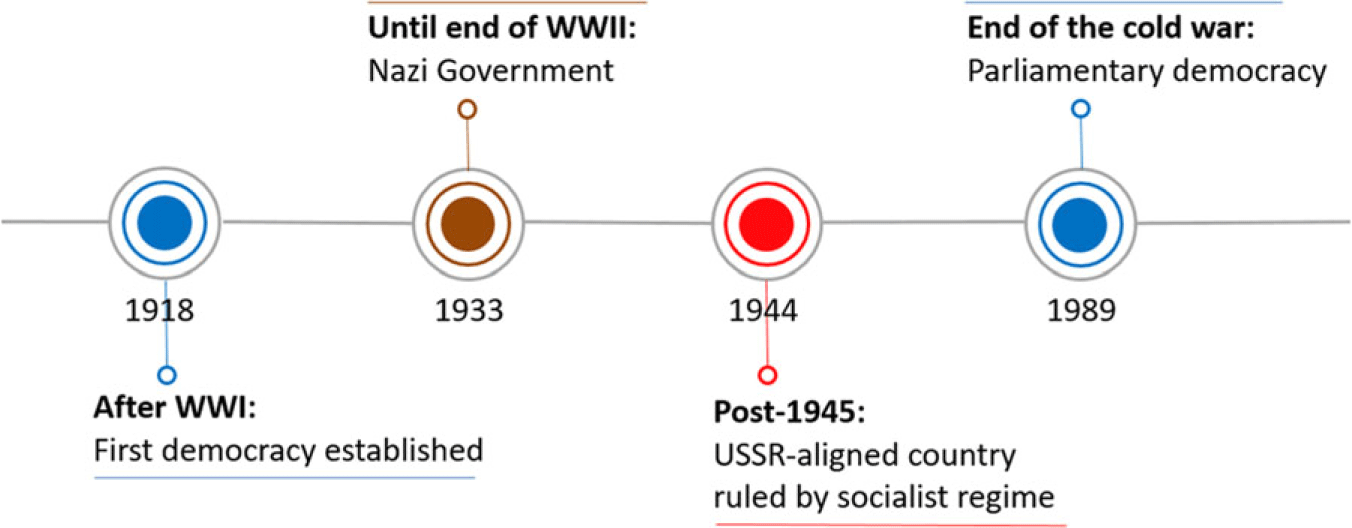

Central and Eastern Europe offer an unparalleled case study for exploring transformations in representational politics as a result of changes in state ideology. Having established their first democracies after WWI, these states were occupied and/or governed by Nazi Germany until the end of WWII. Post-1945, the USSR-aligned countries were ruled by communist/socialist regimes until the end of the Cold War brought parliamentary democracy. Figure 1 summarizes the historical timeline during the period of investigation.

Figure 1. Political timeline of the present investigation.

This rapid turnover of different forms of government means that the timeframe under investigation encompasses five consecutive eras that are characterized by antithetical state-sanctioned political ideologies and commemorative priorities (Assmann, Reference Assmann, Erll and Nünning2010; Vuolteenaho & Puzey, Reference Vuolteenaho, Puzey, Rose-Redwood, Alderman and Azaryah2018). As illustrated in Table 1, these eras are delimited by historical events that signal the end of the former and the beginning of a new political Weltanschauung. We will implement these five natural break-points (Gerring, Reference Gerring2012) to subdivide the 102-year time span on which our research is based.

Table 1. Historical political-ideological eras as implemented in the present article

aWe operationalize Germany’s capitulation as the end of WWII in Europe, being well aware that the formal Japanese surrender ceremony that ended the war in Asia was not until September 2, 1945.

Unsurprisingly, the rapid succession of changes in official state ideology have resulted in changes in the way collective memory is inscribed in the semiotic landscape (Assmann, Reference Assmann, Erll and Nünning2010). A famous case is the name change of whole cities: Chemnitz was renamed Karl-Marx-Stadt in 1953 and back to Chemnitz after 1989.Footnote 3 As this example vividly illustrates, commemorative renaming strategies in Eastern Europe function as a powerful mechanism to obliterate referents of “the discredited past from the public sphere demonstrat[ing] the end of [one regime] … and the beginning of a new era” (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu2012:387). The mere fact that different versions of history exist—and are replaced in city textuality across time—illustrates the subversive potential of such public namings to create a natural order of things (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough2003). More than a “barometer” of political changes, textual renewal is recruited as a powerful tool for constructing a hegemonic, publicly enforced, sociopolitical identity (Kaltenberg-Kwiatkowska, Reference Kaltenberg-Kwiatkowska2011:165). Not surprisingly, researchers in memory culture have argued that commemorative renaming should be treated as an exercise in active forgetting (Assman, Reference Assmann, Erll and Nünning2010) or repressive erasure (Connerton, Reference Connerton2008). In the next section, we briefly introduce the theoretical background of our investigation before describing our data and methodology in more detail.

3. The linguistic geography of commemorative naming

The intersection of language and space has been explored throughout the disciplinary histories of both linguistics and geography. Within linguistics, the field of linguistic landscape (“LL”) studies has a pedigree going back to the 1970s. Initially concerned with the distribution of languages across, often contested, urban space, the field has since broadened, “integrat[ing] and embrac[ing] various theoretical and epistemological viewpoints … develop[ing] new methodologies, and now cover[ing] a range of linguistic artifacts” (Van Mensel, Vandenbroucke, & Blackwood, Reference Van Mensel, Vandenbroucke, Blackwood, García, Flores and Spotti2016:424). This expansion has resulted in a shift of focus “away from the question of the visibility of different languages to the ideological discourse of power, national identity and sovereignty connected with place naming” (Listewnik, Reference Listewnik2021). Only recently has the field taken a turn toward more sophisticated quantitative approaches, taking onboard some of the theoretical and methodological premises of variationist sociolinguistics. Soukup (Reference Soukup2020; see also Amos & Soukup, Reference Will, Soukup, Malinowski and Tufi2020) has called this emerging subfield variationist LL studies (VaLLS) and a number of researchers have demonstrated the value of exploring changes in the LL from an accountable, quantitative point of view (Buchstaller & Alvanides, Reference Buchstaller and Alvanides2013, Reference Buchstaller and Alvanides2018; Hélot et al., Reference Hélot, Barni, Janssens, Bagna, Christine Hélot, Janssens and Bagna2012:18, inter alia). At the same time, research within the framework of LL has started to take a more critical turn, drawing on approaches from discourse analysis, semiotics, and the more affect-centered strands of geography (Wee, Reference Wee2016; Wee & Goh, Reference Wee and Goh2016). In particular, the literature on critical toponymy, which focuses on the ideological affordances of semiotic choices in the city text, has provided important impulses to linguistic research on public textualities, expanding its remit to “the connection between power relations, public memory, identity formation and commemorative … naming. [Much of this research has focused on the] underlying question … which visions of history are entitled to be inscribed on street signs” (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu2012:388).

At the same time, critical toponymy, a research framework rooted in qualitative epistemologies, stands to benefit from the infusion of quantitative methods typical of variationist sociolinguistics (see Buchstaller & Alvanides, Reference Buchstaller and Alvanides2018; Soukup, Reference Soukup2020). To date, however, integrated interdisciplinary studies remain few and far between (Buchstaller et al., Reference Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese, Schneider, Ziegler and Marten2021; Fabiszak et al., Reference Fabiszak, Isabelle Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese and Schneider2021; Rose-Redwood et al., Reference Rose-Redwood, Vuolteenaho, Young and Light2019). The present article aims to contribute to the VaLLS enterprise by infusing sophisticated quantitative methodologies into linguistic landscape and critical toponymy research and by connecting them more explicitly with state-of-the-art geovisualization methods from human geography (see also Barni & Bagna, Reference Barni and Bagna2015).

What is more, both fields suffer from a dearth of research that would put changes in commemorative priorities into a longer historical context. LL scholarship acknowledges the historical forces that have brought about the “social order” (Blommaert, Reference Blommaert2013:51) of the status quo, including the establishment of postcolonial societies (e.g., Berg & Kearns, Reference Berg and Kearns2002; Gorter et al., Reference Gorter, Marten and Van Mensel2012; Buchstaller & Alvanides, Reference Buchstaller and Alvanides2018), the transition of postsocialist states in Eastern Europe to social democracies (i.e., Czepczyński, Reference Czepczyński2008; Gnatiuk, Reference Gnatiuk2018), and calls for regime change in North Africa (Dabbour, Reference Dabbour2017; Messekher, Reference Messekher, Rubdy and Ben Said2015; Shiri, Reference Shiri, Rubdy and Ben Said2015). However, to date, LL landscape research tends to be conducted within a rather constricted timeframe. While recent work has started to broaden the diachronic scope (Buchstaller et al., Reference Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese, Schneider, Ziegler and Marten2021; Pavlenko, Reference Pavlenko, Shohamy, Barni and Ben-Rafael2010; Spalding, Reference Spalding2013), Pavlenko and Mullen’s (Reference Pavlenko and Mullen2015:117) criticism holds that “LL researchers overlook diachronicity at their peril” (see also Mensel, Vandenbroucke & Blackwood, Reference Van Mensel, Vandenbroucke, Blackwood, García, Flores and Spotti2016).

The field of critical toponymy engages much more explicitly with the historical events that have triggered changes in representational politics, especially in the context of spatial justice and privilege, including as a consequence of political changes (Helander, Reference Helander, Berg and Vuolteenaho2009; Stiperski et al., Reference Stiperski, Emil Heršak, Zygmunt Górka, Jelena Lončar, Miličević, Vujaković and Hruška2011), or shifts in market economy and /or gentrification (Osman, Reference Osman2011; Sakizlioglu & Uitermark, Reference Sakizlioglu and Uitermark2014, inter alia). But what is still largely missing in this research tradition is a longitudinal timeframe to investigate the “wave[s] of renamings that swept” (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu1986:590) through time and space and, hence, a truly diachronic analysis of public textuality. Such an approach, especially when based on quantitative, accountable data, facilitates comparative analysis (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu2011b) not only on the temporal axis but also across different geographies. In this paper, we explore the longitudinal repercussions of changes in state-sanctioned commemoration over the past 100 years in the city of Leipzig.

Processes of changing officially sanctioned commemorative textuality in public space obviously transcend street naming; currently, debates are circling around the names of bridges (Listewnik, Reference Listewnik2021), airports (Olen, Reference Olen2020), schools (Aldermann, Reference Aldermann2002), train stations (Rubdy, Reference Rubdy2021), and army barracks (Ismay, Reference Ismay2020). Traditionally, Linguistic Landscape research has taken a holistic approach to public denotation, focusing on “all public or commercial signs in a given region or territory” (Landry & Bourhis, Reference Landry and Bourhis1997:23). Critical toponomy and increasingly research situated at the intersection with memory or LL studies tends to assume a more focused approach, honing in on the political implications of specific “signs-in-place” (Van Mensel et al., Reference Van Mensel, Vandenbroucke, Blackwood, García, Flores and Spotti2016:427) such as graffiti (Pennycook, Reference Pennycook, Shohamy and Gorter2009, Reference Pennycook, Jaworski and Thurlow2010), disaster signage (Tann & Ben Said, Reference Tann, Ben Said, Rudby and Ben Said2015) or shop windows (Collins & Slembruck, Reference Collins and Slembrouk2007) among many others. The lion’s share of toponymic research, however, centers on street (square, bridge, or building) (re)naming. This focus is due to a number of factors: their pervasive nature in most (but not all, see Banda & Jimaima, Reference Banda and Jimaima2015) geographies, the relative administrative ease of changing such names (compared to, for example, airports or military installations) resulting in a reasonably robust turnover in this part of public infrastructure, combined with the availability of and access to official documentation. Apart from these practical aspects, critical toponymy (see Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu2011a; Rose-Redwood, Aldermann, & Azaryahu, Reference Rose-Redwood, Alderman and Azaryahu2018a, Reference Rose-Redwood, Alderman, Azaryahu, Rose-Redwood, Alderman and Azaryahu2018b; Berg & Vuolteenaho, Reference Berg and Vuolteenaho2009; inter alia) has cogently demonstrated the symbolic value and political implications of street-naming practices. Azaryahu (Reference Azaryahu1997:480) in particular has argued that name choices in the streetscape overtly display and thereby embody political ideology: naming “canonise[s] events, people, places as traces of the national past that are consciously commemorated [and as such] … supportive of the hegemonic socio-political order.” Street names are thus particularly revelatory for tracing changes in representational politics, since their commemorative potential is more subversive than the denotational semantics of heroes on horseback, statues on pedestals, and military infrastructure. Zieliński (Reference Zieliński and Kaltenberg-Kwiatkowska1994:195) has argued, and we agree, that street names are to be considered a focal part of “the ideological robe of the city” and can thus be used as a measurement of political change.

There is a rich literature documenting and analyzing commemorative street renaming following shifts in political power and the concomitant ideological reorientation in the 1990s in cities of post-Communist societies, such as East Berlin, Bucharest, Budapest, Moscow, Kyiv, Pristina, and Warsaw (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu2012:389; Demaj, Reference Demaj2013; Foote, Toth, & Arvey Reference Foote, Toth and Arvey1999; Light, Reference Light2004; Majewski, Reference Majewski2012; Palonen, Reference Palonen2008; Pavlenko, Reference Pavlenko, Shohamy, Barni and Ben-Rafael2010; Sloboda, Reference Sloboda, Shohamy and Gorter2009; Szerszeń, Reference Szerszeń2014; inter alia). Taken together, these studies have revealed a dramatic denotational turnover in Eastern European streetscapes, indexing and in turn enshrining the transition to democratic market economies (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu1997; Buchstaller et al., Reference Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese, Schneider, Ziegler and Marten2021; Vuolteenaho & Puzey, Reference Vuolteenaho, Puzey, Rose-Redwood, Alderman and Azaryah2018; inter alia for Eastern Germany). Our paper builds on this LL and critical ethnographic work, integrating findings from different methodological perspectives to develop a coherent framework for understanding the spatial patterns of commemorative street renaming in Leipzig over the past century.

4. Data and methods

We draw on variationist sociolinguistics as well as methods developed in quantitative geolinguistics (Buchstaller & Alvanides, Reference Buchstaller and Alvanides2013) and geospatial visualization techniques (Oueslati, Alvanides & Garrod, Reference Oueslati, Alvanides and Garrod2015) to map the toponymic traces of “ruptures in political history” (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu1997:481) across time and space. Triangulating these spatiotemporal patterns with historical archival material contextualizes quantitative results in terms of their relevance for memorializing and provides insights into the processes via which the spatial expression of commemorative semantics is negotiated across an eventful century (Fabiszak & Brzezińska, Reference Fabiszak and Brzezińska2016).

The starting point for our analysis is the early 2019 version of OpenStreetMap (OSM)Footnote 4 for Leipzig,Footnote 5 yielding 2,150 unique street names.Footnote 6 We converted this information into a large Excel spreadsheet (2,150 rows by 102 columns representing the years from 1916–2018 = 219,300 cells). The Leipzig office for statistics and elections provided us with a database containing information about the rationale for renaming and the semantics of the street names, the exact dates (where available) when the renaming was proposed in the city council and when the decision was passed (Stadt Leipzig, Amt für Statistik und Wahlen, 2018). We adopt the latter in our analysis since it is consistently available for the vast majority of streets (in the very few cases where the date of resolution could not be found, we reverted to the date of implementation).

The total number of street name changes in the city of Leipzig over the period 1916–2018 was 2,230. To explore how changes in the official streetscape are recruited to index hegemonic state ideology, we collated information in the database with documents retrieved from the city archives and libraries as well as information available online. On the basis of these data, we coded every street name change as to whether the incoming and the outgoing name were ideological in nature (see Fabiszak et al., Reference Fabiszak, Isabelle Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese and Schneider2021 for the details of the procedure). This ontological classification forms the basis of a fine-grained chronological analysis that locates the moments in time when larger shifts in the ideological robe of the city took place. Moreover, it allows us to determine whether the city text becomes more or less ideological during the five sociopolitical eras captured by our frame of investigation.

Once the spreadsheet was created, data coding progressed starting from 1916. Going forward in time, information about street name(s) (changes) was entered manually row by row, noting for every street when a renaming took place as well as the ontological status of the street names involved. Table 2, which contains an abridged snippet from our dataset during the years 1944–1945 (the end of the Nazi period and the immediate aftermath of WWII) illustrates our coding procedure. Note that the column “street semantics” contains two values, one for the ontological status of the former street name and one for the new street name. P stands for a street name that is political-ideological in nature whereas N stands for a non-ideological street name. As is exemplified in the first two rows, Pegauer Straße and Wurzner Straße (non-ideological street names referring to towns in the vicinity of Leipzig, namely Pegau and Wurzen respectively)Footnote 7 were replaced by streets bearing the names of a communist partisan and a member of the underground resistance, Erich-Ferl and Wolfgang Heinze. These changes increase the number of streets encoding socialist ideology by two referents and—in line with Azaryahu (Reference Azaryahu1997, Reference Azaryahu2011a), Vuolteenaho and Puzey (Reference Vuolteenaho, Puzey, Rose-Redwood, Alderman and Azaryah2018), inter alia—we interpret them as commemorative acts supporting the officially sanctioned Weltanschauung of the new, incoming regime.

The third row in Table 2 illustrates a street named after Paul von Hindenburg, a celebrated general who led the German imperial army during the First World War and who went on to become the second president (1925–1933) of the Weimar Republic. Hindenburg’s key role in the Machtergreifung (taker-over) of the Nazis in 1933 made him a hero of the Third Reich but a problematic figure for commemoration ever since. He was replaced on August 1, 1945 by Friedrich-Ebert, the first democratically elected president of Germany (1919–1925) and distinguished former chairman of the socialist party.Footnote 8 Renamings such as these thus vividly illustrate the turnover of civic “sites of memory” (Winter, Reference Winter1998:102), where one street name indexing a vanquished state ideology is publicly substituted by an iconic figurehead of the new political regime. We coded this renaming as PP.

Table 2. Illustration of coding for street name changes

The next row reveals that Friedrich-Ebert-Straße also replaces Weststraße (West Street), another case where a non-ideological street name is transformed into an ideological one (NP). Together, these two last examples illustrate a relatively frequent occurrence in our dataset, whereby several streets were merged into one longer street. Cases such as these constitute a challenge to our geographical visualization tools.

While the above renamings occurred on August 1, 1945, three months after the end of the German capitulation, they were not the first ones to occur. The last two rows in Table 2 reveal that the most iconic Nazi iconography was purged from the streetscape almost instantaneously after the fall of the Third Reich: by May 15, only seven days after Germany’s unconditional surrender, Adolf-Hitler-Straße was reverted to its previous name, Hauptstraße (‘main street,’ which it had held up until 1933). Only four days later, the street memorializing one of the key martyrs of Nazi Germany, Leo Schlageter,Footnote 9 was changed to refer to Gundorf, a local municipality to the west of Leipzig, to which it is leading. On August 1, this street switched referent again to commemorate Georg Schwarz, a communist MP and member of the antifascist resistance who was murdered during the Third Reich. Our data contain three such cases where renaming occurred in close succession in the year 1945, and this unusually quick turnover can be explained by the geopolitical advances of the allied forces at the very end of WWII: in April 1945, Leipzig was liberated by American forces who immediately razed the most egregious Nazi iconography from the streetscape. When, in July 1945 and in accordance with the agreement of the Yalta conference, the region of Saxony was officially allocated to the Soviet zone of occupation, some streets were renamed again, often to publicly encode Leninist-Marxist political-economic ideology.

Double renaming not only draws our attention to the extent to which the allied forces were aware of, and consequently exploited, the potential of street names as propaganda carriers for a regime’s political-ideological needs. They also remind us that our analysis needs to be able to capture more than one change per year (in this case first PN and then NP) to provide an accountable basis for the quantification of commemorative (re)naming practices. The next sections illustrate the results of our interdisciplinary research project that analyzes commemorative street name changes in Leipzig over the past 102 years.

5. The timeline of street renaming in Leipzig

Figure 2 plots the entirety of street name changes over the 102-year period covered in this analysis, revealing the consecutive “wave[s] of renamings that swept” through time and space in the Leipzig streetscape (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu1986:590). There are five areas of activity that correspond to the natural breaks in German history we pinpointed above: a small peak (1919–1920) after WWI and in the early years of the Weimar Republic, as well as a large cluster of odonymic activity in 1928 and during the early years of the Nazi regime. The most evident spikes are evident at the cusp of two later ideological ruptures: the years 1945–1950 signaling the end of the Nazi regime after Germany’s defeat in WWII and the years following German reunification in 1989. These findings provide quantitative support for Azaryahu’s (Reference Azaryahu2012:385) assertion that “the commemorative renaming of streets in the context of regime change is a common strategy employed to signify the break with the past … [and as such a] measure of historical revision.”

Figure 2. Total change in street names over the 102 years in Leipzig. *Peaks are at least partly due to urban expansion.

Note here that two peaks occur during particularly active phases of urban sprawl, and we have marked these with an asterisk in Figure 2. While the city of Leipzig continued to grow over the 102-year period, city expansions in the years 1925 and 1999 incorporated exceptionally large numbers of surrounding municipalities (Gemeinden) into the city boundary, with about 15,000 and 45,000 people, respectively, becoming part of the Leipzig local authority during these years.Footnote 10 Hence, rather than purely an outcome of ideologically motivated renaming processes, we would assume that the heavy semantic turnover in the following years was at least partly an artifact of the administrative corollaries related to city expansion. What this effectively means is that we need to pinpoint the temporal zones when odonymic activity was not dominated by population growth necessitating toponomic decisions, that is, finding official referents for new streets and solving doublets.

Figure 3 goes some ways toward this goal, splitting up the semiotic processes that have swept over the Leipzig streetscape in the past century. The yellow line traces the chronological patterns of the new 1,098 streets that were introduced into the streetscape during the last century. The green line illustrates the temporality of the 1,132 renamings. What becomes immediately obvious is that the spike in semantic modification during the Nazi period (years 1933–1939) was largely due to the naming of new streets (streets that did not exist before). Similarly, numerous upward bumps during the GRD regime (most noticeably so during the years 1977–1980, 1986–1988) were caused by an increase in the total number of streets, not by street renaming. The time frame 1993–1997, a few years after the Wende, is also dominated by the naming of new streets.

Figure 3. Change in street names over the 102 years in Leipzig split up by new namings versus renamings.

Crucially, Figure 3 identifies those temporal zones when the total number of streets remained constant. It is during these chronosemiotic moments, when odonymic activity is not dominated by administrative geotextual needs, that upticks in bona fide renaming activity are most evident. Not surprisingly, such zones of heightened toponymic transformation are situated at the cusp of turnovers in state ideologies: a modest spike in 1919 following WWI and massive spikes following the end of WWII (during the years 1945–1951) and after the Wende (in 1991). As we pointed out above, the two upswings in the years 1928–1931 and 2000 are concomitant with large city expansions, and we will revisit them in more detail below.

What we do not know yet is the extent to which the observed changes in urban semiotics are strategic, recruiting street names as “carriers of … collective memory” (Moszberger, Rieger, & Daul, Reference Moszberger, Théodore and Léon2002:5) to infuse ideological semantics into urban toponymy. The following analytic step therefore explores the extent to which consecutive regimes differ in their propensity to publicly enshrine their political Weltanschauung. To do so, we operationalized the classification of streets as +/- ideological (see also Buchstaller et al., Reference Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese, Schneider, Ziegler and Marten2021; Fabiszak et al., Reference Fabiszak, Isabelle Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese and Schneider2021; Rubdy, Reference Rubdy2021) to establish a taxonomy that differentiates the main processes via which street names were changed and/or introduced into the semiotic landscape. As Figure 4 illustrates, these processes can be differentiated broadly into two outcomes, which we exemplify with street names from our Leipzig data.

Figure 4. Taxonomy of semantic processes in the streetscape.

The first group of processes are those that result in the infusion of a new political ideology into the linguistic landscape, and we will refer to them as “ideological processes” in the remainder of this paper. Processes of this type include the introduction of new streets with ideological denotation into the city text, such as the naming in 1982 of a new street Straße der Solidarität (‘street of solidarity’ [with other Eastern Bloc countries]). Infusion of a new ideology can also be caused by two types of renaming scenarios. The first is when streets change their status from bearing non-ideological names to ideological names, as the example of renaming from An der alten Elster to Hindenburgstraße in 1930 illustrates. The second constitutes the replacement of ideology, which is the case when a name indexing a particular worldview is replaced by a name indexing a different, often competing referent (and its associated political-ideological connotation), as is exemplified by the substitution of Hindenburgstraße by Friedrich-Ebert-Straße in 1945.

On the other side are processes that do not infuse a new ideology into the streetscape and that we refer to here as “non-ideological.”Footnote 11 These processes include the naming of a new street with a non-ideological name or indeed the renaming of a non-ideological street by another non-ideological street. The example given in Figure 4, the commutation of Drosselweg into Goldammerweg (both local types of birds) in 1997 is a typical illustration of such a process being triggered by urban sprawl. In this particular case, the Seehausen local authority became incorporated into the city of Leipzig during the large city expansion in 1999, resulting in two Drosselstraßen, one of which had to be renamed. The spike in 2000 in Figure 3 is constituted of many such examples. Finally, in some cases, streets were renamed so as to strip away their problematic ideological load and turn them into neutral signifiers, as was the case with Adolf-Hitler-Straße becoming Hauptstraße in 1945.

Condensing the wealth of processes (and their intrinsic motivations) underlying street renaming allows us to explore to what extent subsequent political regimes mobilize the streetscape for their ideological needs. Before we move on to quantify the occurrence of these types of processes over time, we need to contend with the fact that longer ideological-political eras have a disproportionate amount of time to effectuate changes in the streetscape (with the extremes of the 12-year Nazi regime as opposed to the 44-year Soviet occupation and USSR-controlled government). We therefore normalized the outcome of these two processes (+/- infusion of ideology) by the number of years over which the respective ideological political era stretched. The formula we employed is given in Figure 5. The line graph in Figure 6 illustrates the results of this normalization, revealing the number of outcomes averaged by year for every historical period over four consecutive political-ideological eras.Footnote 12

Figure 5. Normalization technique for plotting ideological vs. non-ideological (re)naming across time.Footnote 13

Figure 6. Average number of (re)namings by outcome (normalized by length of regime in years)

Figure 6 reveals that the average occurrence of these two types of semiotic processes fundamentally differs between the sociopolitical eras we consider in this project. More specifically, processes that do not result in the infusion of an ideology or political worldview occur preponderantly during historical eras described as democratic as per contemporary historical classification, namely the Weimar Republic with 20.2 non-ideological changes per year and the reunified, post-1989 Germany with 12.6 non-ideological processes per year (or computed as percentages with only 35% and 32% ideological (re)namings respectively out of all changes in these respective eras). From the perspective of a person walking or driving the streets, this means that the ideological impact of the “robe of the city” (Zieliński, Reference Zieliński and Kaltenberg-Kwiatkowska1994) reduced during these democratic periods. Non-nondemocratic or authoritative forms of government (the interim Nazi and Socialist regimes), on the other hand, tend to manipulate street renaming processes to imbue the semiotic landscape with their political ideology. If calculated per number of years, the relatively short Nazi period reveals itself to be particularly active with 18.8 (re)namings with ideological outcome per year (or 64% and 66% ideological changes out of all changes respectively).

Figure 6 thus reminds us that it is not enough to plot the chronological spikes of street (re)namings. We also need to explore changes in the degree of ideological indexicality encoded in the cityscape, which clearly differ between the consecutive regimes. But while the findings illustrated in Figure 6 provide complementary information to Figures 2 and 3, we have yet to analyze the more fine-grained diachronic distribution of these types of odonymic processes within and across the eras characterized by changing state-ideological orientation. Figure 7, which plots ideological versus non-ideological changes in street names on a year-by-year basis, provides the missing evidence that allows us to fully interpret the longitudinal trajectory we have observed. More specifically, Figure 7 helps us interpret the spikes at the cusp of sociopolitical regimes in Figures 2-3.

Figure 7. Change in street names over the 102 years in Leipzig split up by outcome

High values in the red line pinpoint those temporal zones with the largest influx of commemorative ideology in the Leipzig streetscape. What is immediately obvious is that the most substantial incursion of ideological semantics is situated at the most profound contrasts in political Weltanschauung, namely the end of WWII, when right-wing Nazi official semantics were expulsed and replaced with communist denomination. Another phase of vigorous toponymic activity resulting in ideological infusion is situated in 1934–1936, when the democratic Weimar Republic gave rise to the Nazi regime. The Wende, notably, did not result in an outright toponymic turnover resulting in ideological changes. What we see is a drawn-out process lasting several years and partly obfuscated by city extensions.

Overall, then, processes of resemanticization in the streetscape are primarily situated at the cusp of radical transformations in political Weltanschauung, when subsequent regimes encode their own ideological worldview into public odonymy. At later stages in any respective era, odonymic fervor tends to die down. For the Nazi regime, semiotic activity ceases entirely during WWII.Footnote 14 For the other eras, we hypothesize that once semantic saturation has achieved a satisfactory level, inertia sets in and pressures to transform the streetscape are outweighed by the costsFootnote 15 of changing street names. As a next step, we map the geographical distribution of changes in the Leipzig streetscape during the consecutive waves of political-ideological reorientation that characterize recent eastern German history.

6. Spatiotemporal analysis of street renaming in Leipzig

Our analysis relies on geographical visualisation of the temporal changes discussed earlier and presented here in four maps, each illustrating changes in street (re)naming in the respective historical era. These maps are complemented by the two types of statistics we have operationalized above: the percentage of street (re)naming processes that do and do not infuse new ideological semantics during the respective era as well as the average number of streets that are affected by these processes per year. Taken together, these analytics allow us to trace the spatiality of ongoing resemanticization in the Leipzig streetscape. We will now focus on these consecutive waves of public memorialization in more detail.

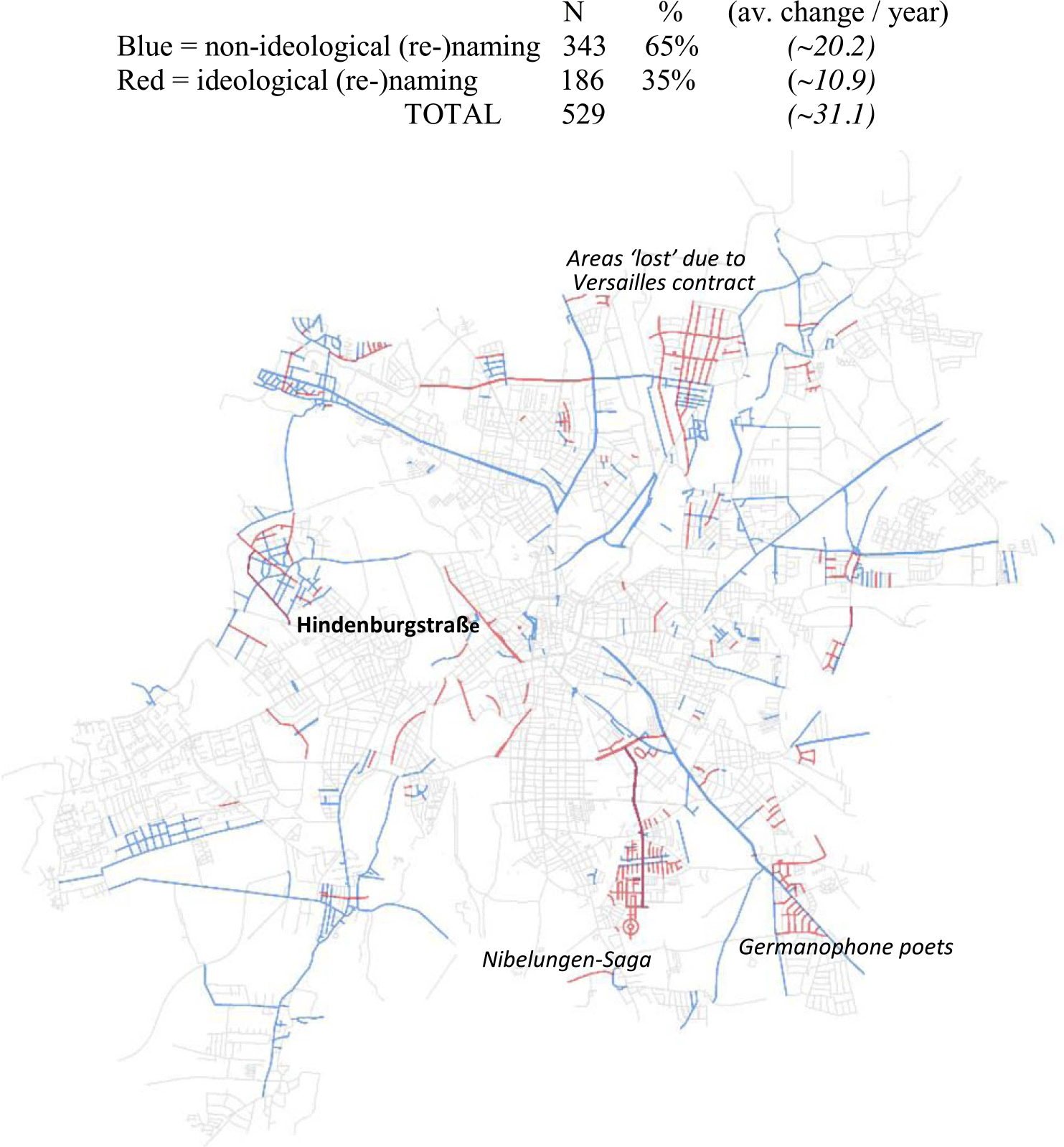

With over thirty streets (re)named per year (N=529 in total), the short era covering the immediate aftermath of WWI and the Weimar Republic (14 years) is characterized by the highest density of toponymic change when averaged by year. Map 1 reveals that a majority (63%) of street (re)namings during the Weimar Republic were non-ideological (and, hence, blue) in nature. The spike in non-ideological renamings in 1919, immediately after the First World War, and as Germany was establishing its first democracy, is a reflection of the fact that the street names indexing the dynastic state ideology of the Prussian Kaiserreich were purged from the semiotic landscape (see Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu1986:182). More specifically, this year saw the ousting of four kings: Friedrich, Albert, Leopold, and Wilhelm, all replaced with names referring to German cities. Also, as we discussed above, the bulk of odonymic activity during this era was born out of the need to build new streets for the rapidly increasing number of inhabitants (in 1917, N=542.845, in 1933, N=713.470; https://bit.ly/2URNuW4). Not surprisingly, a full 61% (N=322) out of all changes in the streetscape during this era were new namings (of which approximately 46% [N=148] were ideological in nature). In comparison with the low ratio of ideological renaming (13%), we note that even during an era with little zeal to change existing public symbols, the introduction of new streets into the cityscape was exploited as an opportunity to do identity work. This finding makes sense given the high administrative, bureaucratic, and financial costs of changing street names (see Buchstaller et al., Reference Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese, Schneider, Ziegler and Marten2021).

Map 1. 1916 to 1932: WWI & Early Democracy

One particular aspect that characterizes the odonymic memory politics of the Weimar Republic, especially in comparison with the subsequent two regimes, is the conspicuous reluctance to encode system-specific ideology on the key traffic axes leading to the city center. One of our hypotheses at the start of the project was that those arteries transporting visitors to the administrative and commercial hubs situated around the ring road in the middle of these maps would be recruited for representational purposes and thus targeted by ideologically motivated odonymic activity. However, for the Weimar Republic, this seems not to have been the case: the only large street leading to the center that had been infused with regime-specific ideology was the aforementioned Hindenburgstraße, memorialized in 1930.

When commemorative street-naming processes did occur during the Weimar Republic, they were mainly situated in smaller residential streets at the outskirts of the city. The cluster of red streets leading to a crescent in the lower middle area of the map is the site where traditional German mythology was publicly consecrated. It is here that we find Siegfried-Platz and Krimhildstraße, among others, all of which are characters from the German national epos, the Nibelungensage (see also Nibelungenring). Named as a group in 1930–31, the encoding of this middle high poem was an act of commemorating nationalist German identity in the cityscape. Crucially, none of these streets have been renamed since. This might be because the symbolism of memorializing the German national epos has not been called into question at any later historical stage, probably because inscribing German identity via heroic but apolitical figures has not been considered problematic by consecutive state ideologies.

The other southern cluster of ideological incoming streets in Map 1 is the commemoration of a group of Germanophone poets (Theodor Storm, Gottfried Keller, etc.) whose works had been recently published by Leipzig publishing houses. It is important to remember in this respect that, until WWII, “Leipzig was the center of publishing, book production, and [printing] … Among the most prominent business were publishers like … Brockhaus, Reclam, [and Baedecker] …. The Duden, Meyers Konversationslexikon, and 90% of sheetmusic and scores worldwide were printed here” (Verheyen, Reference Verheyen2019; emphasis ours). Encoding the artistic geniuses whose oeuvres are being put in print in this very city was thus an act of assigning “semantic features to the dimension of” prestige (Hymes, Reference Hymes1964:117; Silverman, Reference Silverman1966), a public display of Leipzig’s intellectual pre-eminence, which we count as self-presentational and thus ideological. As with the German mythology discussed above, these streets remain in place. Indeed, the remit of poets and musicians has since been expanded.

The situation was very different in the North of Leipzig, which features a cluster of streets commemorating territories that had been ceded (mainly to Poland) as part of the Treaty of Versailles (1919). This cluster of naming, which occurred in 1932, encoded into public space this “lost but not forgotten land” (“Verlorenes – doch nicht vergessenes Land”).Footnote 16 As we will see below, this was an early semiotic instantiation of the widely felt resentment about the abjuration of territory which the Nazis harnessed as part of their geopolitical propaganda just a few years later.

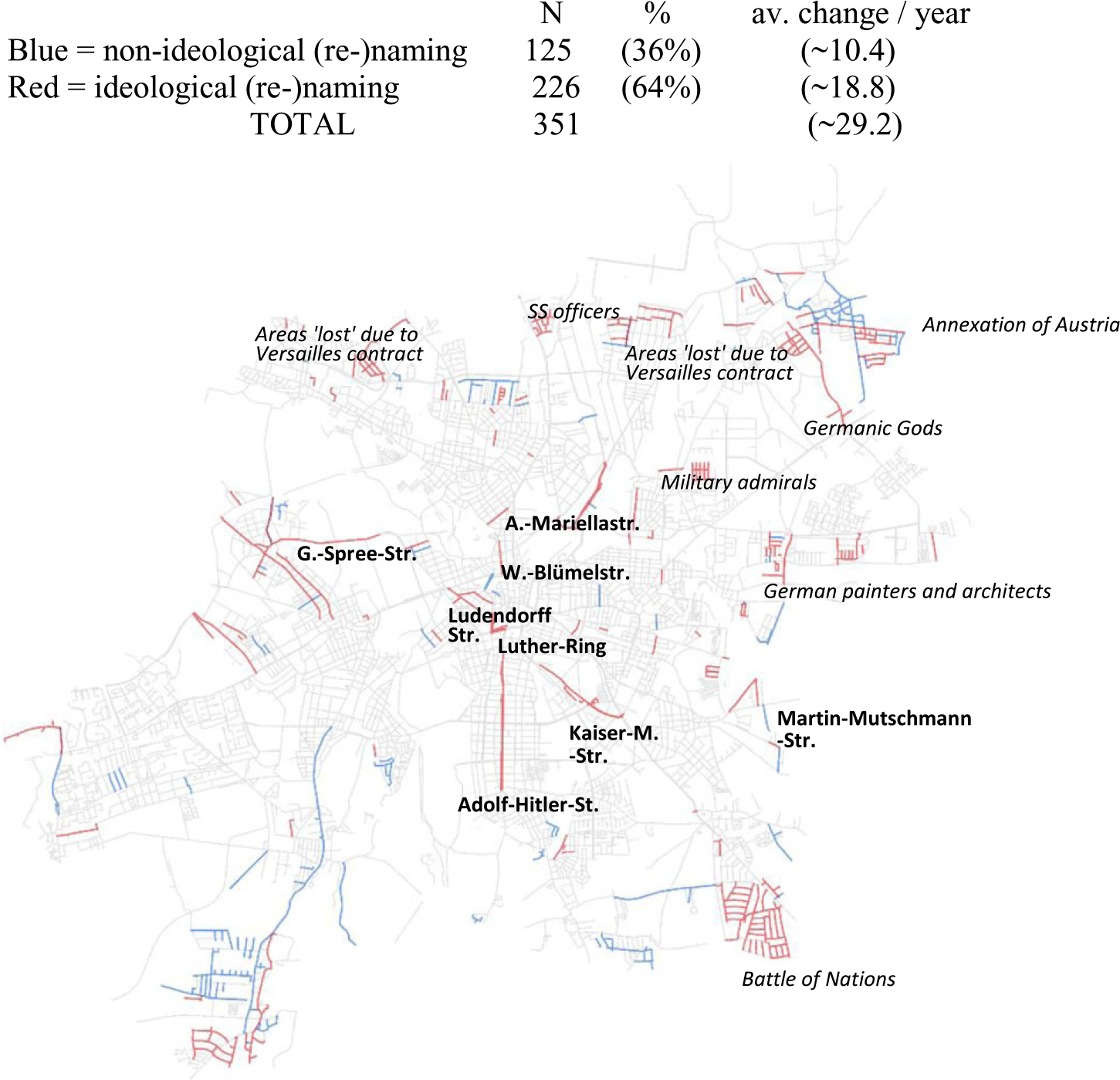

The equally short Nazi regime (Map 2) also exhibited a high tally of odonymic activity (29 per year, N=351), of which a large proportion (73%) was again new and thus due to city growth. Contrary to the Weimar Republic, the vast majority of (re)naming processes during this era (64%) aimed at the infusion of nationalist ideology into the streetscape. Most iconically, the key traffic artery from the south toward the city center now bore the name Adolf-Hitler-straße (beginning in 1933).Footnote 17 Several other large streets approaching the ring were renamed to encode personages that memorialize Third Reich Weltanschauung, which included commemorating heroes of the armed forces and Nazi “martyrs”: SA henchmen Walter Blümel and Alfred Marietta (both in 1933), admiral Count Spree (in 1934), and General Ludendorff, one of the main enablers of Hitler (in 1937), as well as the leader of the Saxony regional branch of the Nazi Party, Martin Mutschmann (in 1933). Kaiser (‘emperor’) Maximilian I (1459–1519), commemorated in 1936, was important to the Nazis for a number reasons, including his consolidation of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Another aspect that likely appealed to Nazi ideology was his public acts of antisemitism (Bell, Reference Bell2001; Green, Reference Green2013).

Map 2. 1933 to 1944: Nazi Germany & WWII

Part of the ring street itself was renamed in 1933 to commemorate Martin Luther, likely much less a tribute to Luther’s role in reforming religious doctrine than a symbol of German national pre-eminence. Summarily, the strategy of encoding German luminaries into the roads approaching the city center reveals the powerful semantic force of impressing nationalist German ideology on the urban experience of the flâneur.Footnote 18

Some aggregates of odonymic activity during the Nazi era are worth commenting on here: the conspicuous cluster of residential streets at the bottom right of the map commemorates the historical battle of the nations against Napoleon that had been fought in this area in 1818 and for which a large monument was erected nearby in 1913. What is interesting is that of all the military commanders commemorated in this area, only the Russian generals remain to this day, whereas Austrian and Prussian soldiers were purged during the Soviet-controlled GDF regime. As we will see below, they were summarily replaced by German (Joachim Gottschalk, Heinrich Zille, Heinrich Mann) and European (Zola, Cervantes, Cézanne, etc.) poets, lyricists, and playwrights.

In the North of the city, and interspersed by a collection of streets commemorating SS officers, we find two clusters adding more “lost” territories into the streetscape, including areas that are now situated in Alsace, in the Czech Republic, and in Poland. There is also an area memorializing Germanic Gods (Wodan, Balder, Forsethi, etc., named as a group in 1937) and a cluster of locally renowned German painters and architects. After the annexation of Austria to the Third Reich on March 12, 1939, a collection of streets commemorates Austrian cities, starting with Hitler’s birthplace of Braunau (named November 5, 1939).

In sum, apart from referencing key personages that epitomize Nazi ideology and index German supremacy, the commemorative priorities of the Third Reich seem to have been primarily militaristic/geopolitical in nature. Again, most of the incoming ideology can be found in the namings of new streets whereas the percentage of ideologically motivated renaming is much lower (with only 19%, N=66 ideological renamings, in stark contrast to the following GDR regime). What this effectively means is that the Nazi approach to the Leipzig semiotic streetscape was not primarily to purge previous and introduce new, ideologically more aligned referents (contrary to Azaryahu’s Reference Azaryahu1986:81 findings for Berlin). This reticence to resemioticize the streetscape might come as a surprise for a regime whose propaganda strategy for the public sphere is well documented (Rutherford, Reference Rutherford1978; Spotts, Reference Spotts2003; Steinweis, Reference Steinweis1993). Notably, however, the archival materials we consulted contain numerous laws, bylaws, bills, and decisions that attest to the Third Reich’s effort to enshrine a timeless Aryan heritage via a seemingly intransigent, stable urban semiotics. Similarly, Buchstaller et al. (Reference Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese, Schneider, Ziegler and Marten2021) argue that, apart from the aforementioned aversion to the bureaucratic costs of changing street names, the Nazis were reluctant to change “good old German names that had grown over the years and commemorated German sons.” Hence, rather than raze the extant semantics and turn the public streetscape into one large propaganda billboard, the Ministry of the Interior issued a memo that “a change in street name is only appropriate in exceptional circumstances, when warranted and indeed necessitated such as when the denomination of a street is running contrary to the nationalist state ideals, if the name is considered offensive by large parts of the citizens, or when it results in confusion.” Footnote 19

As we see in Map 3, the opposite strategy to commemorative semanticization seems to have been deployed during the GDR regime. The end of the war, and with it Soviet occupation followed by a USSR-controlled government, brought a dramatic ideological transformation in commemorative street (re-)naming practices. Overall, 789 streets, the largest total number, were (re-)named between 1945 and 1988. When averaged over the number of years, this only amounts to 18 street (re)namings per year. But as we know from Figure 7, the years in the immediate aftermath of WWII (1945–1950) saw a gigantic odonymic turnover. Undesirable commemoration was eliminated, being replaced by antifascist, antimilitaristic, and, of course, socialist-communist street names (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu1986:81). Hence, the cluster of admirals and the areas “lost” due to the Treaty of Versailles in the center north of the city were summatively replaced in 1947–1950 by a group of Russian artists and scientists (Gogol, Tolstoi, etc.), who were joined by a collection of communists, resistance fighters persecuted by the Nazis, as well as artists deemed as “degenerate” during the Third Reich. Similarly, the site commemorating German and Austrian generals who fought in the battle of the Nations in the southeast was purged to make space for international and German artists in 1950. The massive and swift resemanticization at the beginning of this era is thus tantamount to an official disavowal of the previous regime whereby the losers vanquish from the cityscape and with them their publicly encoded ideology (on the concept of “victors of history” see Jarausch, Reference Jarausch1991:85). As Azaryahu (Reference Azaryahu2012:385) rightly points out, “the commemorative renaming of streets in the context of regime change is a common strategy [of historical revision], …. employed to signify the break with the past.”

Map 3. 1945 to 1988: GDR Socialist regime

What is immediately noticeable is that the impact of GDR odonymic policy is broadly distributed across the cityscape. Overall, the USSR-supported regime accomplished a remarkable resemantcization of the streetscape with just over half of all Leipzig streets being affected by changes in total during this era. Of these changes, 66% were (re)namings resulting in an ideological outcome that was in line with official communist-socialist Weltanschauung.Footnote 20 But apart from the thorough ideological saturation of public toponymy, we also note the strategic geographical placement of street names bearing regime-specific semantics: the representative square in front of the main train station was named Platz der Republic ‘square of the republic’ in 1953 in honor of the foundation of the GDR. It was flanked by Rosa-Luxemburg-Straße on the one side and Breitscheidstraße Footnote 21 on the other. As discussed above, Adolf-Hitler was expelled from the main southern artery only a few months after April 1945 to memorialize Karl Liebknecht. All other large parallel streets were bestowed upon communist revolutionaries or heroes of the socialist insurgency, including Rosa Luxemburg in the North, Ernst Thälmann in the East, and Marx and Lenin in the Southeast. These icons of socialist-communist ideology were accompanied by a legion of dignitaries of left-leaning Weltanschauung, victims of Nazi brutality, resistance members, and communist class fighters (Arthur-Hoffman, Richard Lehmann, Georg-Schumann, Georg Schwarz, Gerhard Ellrodt, etc.).Footnote 22 The Northeast even features a whole area commemorating resistance fighters and members of the Putsch against Hitler. This summative recruitment of the streetscape for system-specific memorialization fully supports Azaryahu’s (Reference Azaryahu1986:581–7) assertion that “it is not surprising that [streets have been called] propaganda carriers [since] … major political changes are reflected in the renaming of streets.” The exhaustive ideological entrenchment during GRD times made it increasingly impossible to travel on the main streets without being faced with official infrastructure consecrating regime-specific ideology. Notably, a full 60% of all semiotic encoding during the GDR era is due to renaming, which suggests that the infusion of ideology in the streetscape trumped the associated costs and efforts. One could argue that the existence of highly problematic Nazi symbolism made renaming necessary. However, 18% of all renamings were of the type NP, meaning that previously non-ideological streets were usurped for the Marxist-Leninist cause (compared to 14% during the Nazi era).

The GDR also continued the strategy of encoding the canon of eminent German, Russian, and international artists (Gorki, Goya, Rodin, Shakespeare, etc.), who were translated, published, or discussed in the learned institutions of the city, a commemorative practice that had begun during the Weimar Republic. Enshrining the city’s artistic heritage into public memory reinforces existing odonymy indexing “semantic features to the dimension of” prestige (Hymes, Reference Hymes1964:117; Silverman, Reference Silverman1966). It also connects with a further display of Leipzig’s intellectual pre-eminence that was amplified during the GDR era: the commemoration of prominent scientists (Max-Planck, Willhelm Röntgen, Marie Curie, Michael Faraday, etc.). While many Nobel Prize winners and universal geniuses had indeed studied, taught, or done research at Leipzig University, encoding their scientific reputation in public textuality is a strategy to market by then over 500 years of scientific tradition,Footnote 23 advertising Leipzig as a city of sciences with an international reputation for outstanding achievements. We thus interpret the encoding of artistic and scientific excellence as part of a larger city branding strategy, promoting Leipzig as a destination for national and international tourists, scientists, or even business opportunities (see Guyot & Seethal, Reference Guyot and Seethal2007:60; Hagen, Reference Hagen2011:25–26; Rose-Redwood et al., Reference Rose-Redwood, Vuolteenaho, Young and Light2019). While it might seem counterintuitive to assign commercial interests to a socialist street naming policy, critical research has argued that tapping into marketable imaginaries is one of the major yet underexplored “strategies for branding, selling, legitimising, and characterising” urban toponymy (Madden, Reference Madden2018:1611). The commodification of street names in particular forms part of the under-the-radar toponymic strategies highlighting the “commercialization of public place-naming systems” (Rose-Redwood, Reference Rose-Redwood2011:34, see also Rose-Redwood, Vuolteenaho, Young & Light, Reference Rose-Redwood, Vuolteenaho, Young and Light2019.)

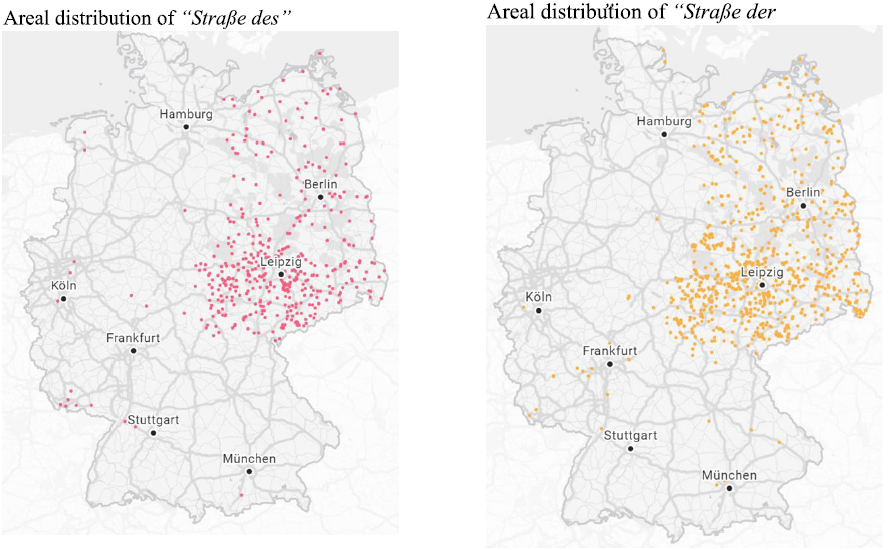

Finally, the asterisks in Map 3 highlight the occurrence of a toponymic strategy that is typical for the socialist-communist regimes of former Eastern Europe: the encoding of values (freedom, unity, solidarity, etc.) underpinning Marxist-Leninist philosophy. In the German language, this naming pattern follows a particular constructional frame shown in Figure 8. Apart from values, the referent slot (see Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2009) can be filled with events (either marked via an iconic date or the occasion itself, which might in fact have provided the initial template for this construction),Footnote 24 or with the names of groups/organizations carrying positive connotations in Marxist-Leninist Weltanschauung.

Figure 8. Constructional frame of German communist-socialist naming strategies.

Note: The article in the genitive case is marked for gender and number (der = ART.GEN.F.SG/ART.GEN.PL, des = ART.GEN.M.SG./ART.GEN.N.SG). The ideological provenance of this construction is further supported by the fact that it was commonly called the “Russian genitive” (see Knabe, Reference Knabe2019).

While many streets have since been renamed, the areal distribution of streets following this constructional template remains visible in German geography until this day. A search of the Die Zeit Online database (Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Paul Blickle, Flavio Gortana, Andreas Loos, Karsten Polke-Majeweski, Steinbrück, Venohr and Zeidler2018) reveals spatial patterns that clearly delineate the former geographical expansion of the GDR (see Maps 4 and 5; consider also Knabe, Reference Knabe2006).

Maps 4 and 5. Areal distribution of streets fitting the constructional frame of communist-socialist naming strategies in Germany (n= 872).

Notably, the productivity of this constructional template shows a bimodal temporal pattern: 12 streets were named before, or in, 1951. Following a 25-year stretch of inactivity we find another seven streets that were commemorated in the late 1970s to mid-1980s. We can only speculate what caused this lag in denomination, but it is interesting to note that the lull in the use of this formulaic naming strategy concurs with the beginning of a period generally referred to as Khushchev’s Thaw, when, after Stalin’ death in 1953, repression, censorship, and propaganda in the Soviet Union and its allied states were relaxed. Our data show no other discernible effects of the de-Stalinization apart from the disappearance of Stalinallee (1949–1956, as it did from many cities in the Soviet-influenced zone; see Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu1986; Fabiszak et al., Reference Fabiszak, Isabelle Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese and Schneider2021; Knabe, Reference Knabe2019).

During the subsequent political transformation (known as the Wende), street names and public symbols “that reflected the GDR’s understanding of socialist tradition were [publicly] called into question” and locally specific debates ensued as to which ones ought to be changed (Germanhistorydocs, n.d.). Map 6 reveals the summative result of this decommemoration effort. Most of the street (re)namings are blue, with the highest percentage (68%) of non-ideological outcomes of all eras investigated. Considering the line graph in Figure 7, we note two spikes, and we will consider both briefly. The reversal in state ideology was at its most vibrant in 1991. In this year, 52 streets were renamed, 36 of which (70%) changed toward non-ideological outcomes, resulting in a thorough purging of socialist-communist traditions from the streetscape. The replacements themselves are interesting political statements. Almost all streets following the fixed socialist construction disappeared, often being supplanted by referents from the far West (and Northwest) of the country. A similar strategy, which expands the imaginary geography of the recently unified German nation toward the opposite direction of the bygone ideological orientation, has been described by Vuolteenaho and Puzey (Reference Vuolteenaho, Puzey, Rose-Redwood, Alderman and Azaryah2018).

Map 6. 1989 to 2018: Parliamentary democracy

Some socialist-communist figureheads (Marx, Thälmann, Lenin, etc.) were extricated from the streetscape together with a wealth of resistance fighters, union leaders, and party members. Often, these streets reverted to their old non-ideological names—if one was available—a strategy described by Azaryahu (Reference Maoz, Rose-Redwood, Alderman and Azaryahu2018:57) as follows: “When regime change is construed in terms of restoration, commemoration may assume the form of recommemoration, namely, the reinstitution of names removed by the former regime, for renaming streets is about substituting one name for another” (see also Knabe, Reference Knabe2019). In Buchstaller et al. (Reference Buchstaller, Alvanides, Griese, Schneider, Ziegler and Marten2021), we have argued that the act of reinstating the former geosemiotics aligns with a more general strategy also found in architecture: the attempt to reconnect with the reality before the Nazi regime (which was more prominent in West Germany, but see, for example, Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Bau & Stadtentwicklung, 2009). The act of street name change is thus ideological in nature, but it results in a decrease of commemorative national ideology in the Leipzig semiotic landscape. But while the Wende brought with it the eradication of some socialist ideology from the semiotic landscape, the geosemiotic turnover in Leipzig is far from complete. Thus, contrary to other cities who have made a consolidated effort to eradicate socialist street names (see Azaryahu’s findings for Berlin 1997:492; consider also Schwerk, Reference Schwerk2013), in Leipzig there are few “attempts … to efface the last residues of the GDR past from the street signs,” and many streets continue to bear the names of socialists, including Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg (see also Knabe, Reference Knabe2006).Footnote 25

Finally, while the city-branding strategy to encode its scientific and artistic heritage continues throughout capitalist democracy, it is here that we first find traces of a different type of Weltanschauung enshrined into the streetscape: the explicit encoding of minority groups (especially those that were denied civil rights during previous regimes) and the public eulogy of personages standing for humanitarian values. Of the 16 ideological street (re)namings in 1991, five commemorate Jews who were persecuted by the Nazis and/or had to flee Germany, and one memorializes the former mayor of Leipzig who resisted the Nazi’s persecution of minorities and political opponents. We also find a woman artist replacing two consecutive streets previously held by men.Footnote 26 This trend to encode civil rights into the public streetscape intensified in the following years. By 2000, a year with ample ideological encoding, there were seven streets giving visibility to women scientists, artists, and women’s rights activists, and ten streets were anti-anti-Semitic in denotation, commemorating either Jewish personages or people standing up to anti-Semitic acts. Other streets encode minority rights, such as the one dedicated to Luz Long, the Olympian long jumper who defied the Nazis by befriending fellow athlete Jesse Owens, or to Max Spohr, a publisher who made essential contributions to the gay emancipation movement in the late 1880s. We also find five more Hitler-Putschists and, for the first time, commemorations that are explicitly critical of the GDR regime. These semiotic choices that we call, extrapolating from Angermeyer’s (Reference Angermeyer2017) research, “punitive,” include non-left-leaning intellectuals, journalists who stood up for the free press, and Wolfgang Zill, a young man who died during an attempted border crossing.

7. Conclusion

While the debate about who and what is commemorated in the official semiotics of the linguistic landscape is not new, the recent #BlackLivesMatter protests have brought to the fore the clash of ideologies that lie behind commemorative naming. Due to their symbolic value, public naming practices overtly display and embody political ideology by being “supportive of the hegemonic socio-political order.… [Naming] canonise[s] events, people, places as traces of the national past that are consciously commemorated in the city scape” (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu1997:480).

To date, research on street name changes has been conducted in vastly different fields with little cross-pollination. Moreover, the analysis of politically and ideologically motivated renaming practices has failed to consider semiotic turnover within the full “time-space matrix of long and short historical periods” that characterize Eastern Europe (Azaryahu, Reference Azaryahu1997:480). The present paper explores the ongoing “battle for the representation” (Trumper-Hecht, Reference Trumper-Hecht, Shohamy and Gorter2009:238) of competing state ideologies as they find expression in street name choices during a century of political upheaval.

Longitudinal analysis of the complex (re)naming patterns allows us to trace the geosemiotic correlates of repeated waves of regime change in a large Eastern European city. By triangulating methods from variationist sociolinguistics, historical archival research, LL analysis, and geovisualization, our analysis explores the geospatial zones in which street names as semantic carriers of memory are constructed and reconstructed for the representational needs of the respective regime. Apart from the encoding, and replacement, of regime-specific Weltanschauung, our analysis has revealed the use of place naming as a city-branding strategy as well as, more recently, the public eulogizing of civil rights activists and minority groups.

Overall, as our quantitative historical analysis of the Leipzig streetscape illustrates, state-sanctioned changes in the city text provide a “window” to the character of a society (Huebner, Reference Huebner and Gorter2006), bringing to the fore its commemorative priorities and spatial semantics.

Acknowledgments

This analysis is part of a three-year project which aims to put single case analyses such as this one into a larger Eastern European context by comparing street name changes in Poland and Eastern Germany. We acknowledge the joint DFG-NCN Beethoven funding stream (#2902/3-1) for allowing us to conduct this project, as well as the intellectual contribution of our colleagues Malgorzata Fabiszak (PI), Anna Brzezińska, Patryk Dobkiewicz and Carolin Schneider. We would like to thank the Leipzig Amt für Wahlen und Statistik (office for voting and statistics), especially Herr Vöckler, for providing us with a database of street name changes. We would also like to thank the Albertina Library in Leipzig for access to their archival materials.