Clinical consults from colleagues within and across specialties and institutions are integral to the practice of medicine. In a formal consult, the consulting clinician typically examines the patient, reviews medical records, recommends a diagnosis or treatment, documents the consult, and gets paid for the service — all traditional features of the doctor–patient relationship.Reference Kuo, Gifford and Stein 1 A related category of consults involves on-call, admitting, or supervisory physicians, who may not directly examine the patient or review their records but who offer consults as part of their formal professional obligations. When patients are harmed as a result of negligence in providing these consults, the proper legal response is clear: consultants owe patients a duty of reasonable care and can be held liable for malpractice when they fall short.Reference Cotton 2

When clinical consults are informal, however, the issues are more complex. In an informal consult, sometimes called a “curbside,”Reference Hale, Freed and Alston 3 a treating clinician seeks input about a specific patient from other medical providers in the hallway, by phone or email, through professional social networks, or by other means.Reference Farnan and Arora 4 The informal consultant then offers their clinical opinion about the patient as a matter of professional courtesy, usually based entirely on information provided by the treating clinician. 5 These consults are distinct from general information gathering via medical journals, books, or online sources, as well as from other informal efforts to rapidly crowdsource guidance about how best to treat a class of patients in the face of uncertainty, as has been common during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although they provide treatment advice about a specific patient, informal consultants have traditionally not been viewed as legally accountable due to the absence of a recognized doctor-patient relationship, a prerequisite for medical malpractice liability in the majority of U.S. jurisdictions. 6 Despite being widely accepted, this approach may fail to encourage due care in informal consults, to the potential detriment of patients, and it precludes patients from seeking legal recompense from responsible consultants. However, the alternative approach — permitting liability for negligent informal consults — also raises important concerns, including potentially discouraging clinicians from engaging in informal consults altogether, even when they might be beneficial. These tensions and uncertainties were recently highlighted in Warren v. Dinter, 7 a 2019 malpractice suit in which the Minnesota Supreme Court rejected the majority rule that a formal doctor-patient relationship is necessary for malpractice liability, instead emphasizing the foreseeability of harm.

Efforts to rigorously study these issues are needed, but the current lack of evidence demonstrating that informal consults meaningfully improve patient care leads us to reject the majority approach, at least for now. In our view, informal consultants should not be granted special protection against liability unless and until evidence is produced indicating that an alternative legal standard would better support patient interests.

Determining which legal approach to informal consults is in patients’ best interest is not solely a matter of legal reasoning. Evidence matters, too — including about such matters as the benefits and drawbacks of informal consults, the conditions under which they are most likely to be helpful or harmful, and the likely impact of different approaches to liability on clinician behavior and patient well-being. Efforts to rigorously study these issues are needed, but the current lack of evidence demonstrating that informal consults meaningfully improve patient care leads us to reject the majority approach, at least for now. In our view, informal consultants should not be granted special protection against liability unless and until evidence is produced indicating that an alternative legal standard would better support patient interests.

Current Legal Approaches

In Warren v. Dinter, a nurse practitioner at a primary care clinic contacted an on-call hospitalist to determine whether a patient should be admitted to his institution for treatment. 8 The nurse practitioner alleged that the hospitalist, who had not examined the patient or reviewed the medical record, told her that the patient did not need to be admitted. 9 The patient died of sepsis from an untreated infection three days later. 10

Because the hospitalist had a professional obligation to take the nurse practitioner’s call and because he served as a gatekeeper to admitting the patient, the Dinter court held that the hospitalist had not provided an informal “curbside” consult, as he claimed. 11 Instead, it determined that he had made a formal medical decision pursuant to hospital protocol about whether the patient would have access to hospital care. 12 Although this was not adequate for the court to find that the hospitalist had established a formal doctor-patient relationship, the court held that the hospitalist nonetheless owed the patient a duty of care because it was foreseeable that the nurse practitioner would rely on his advice. 13 As described below, this standard also has important implications for consults in which a clinician provides informal advice about a patient’s treatment despite having no professional obligation to do so, but in which it is foreseeable that the treating clinician would act on that advice, potentially leading to patient harm.

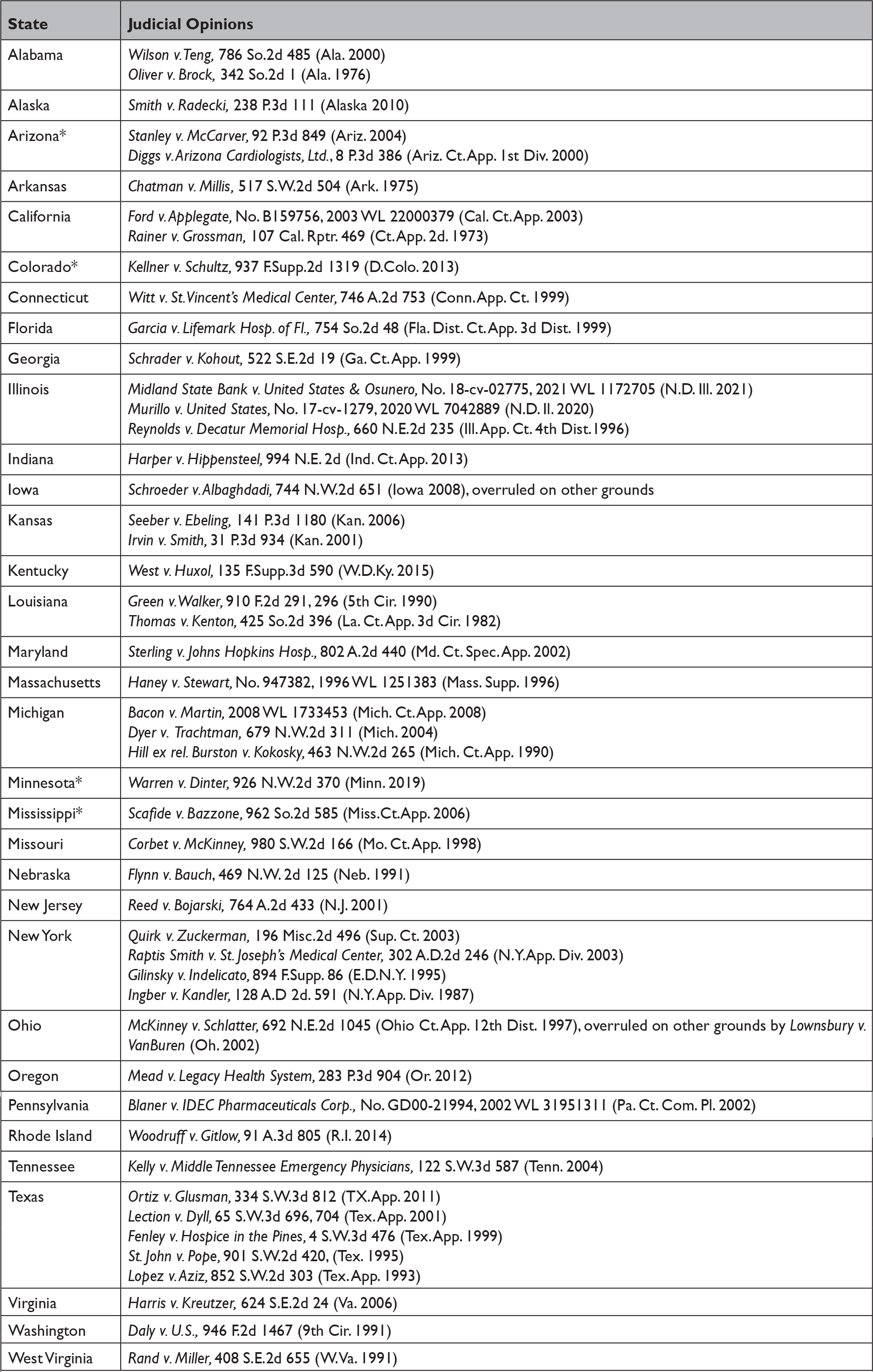

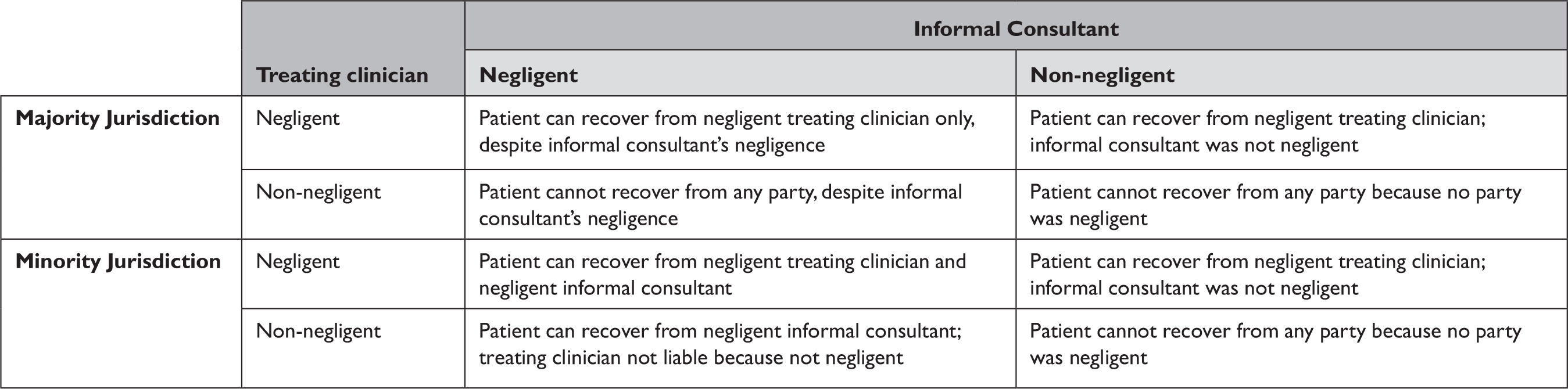

In addition to other legal requirements, a medical malpractice claim will fail if the patient is unable to demonstrate that the clinician owed them a duty of care. Our 50-state survey of court opinions regarding consultant liability reveals that U.S. jurisdictions fall into two broad categories in terms of how this duty may be established (Table 1). Courts in most jurisdictions treat the existence of a doctor–patient relationship as necessary and sufficient to create a duty. The corollary of this rule is that absent facts indicating the existence of a doctor–patient relationship — such as the clinician communicating directly with a patient, reviewing records, or being contracted and paid to provide care — most courts treat clinicians as owing no duty, precluding malpractice liability regardless of the quality of the proffered advice or resulting harm to the patient.

Table 1 Majority and minority approaches to malpractice liability for informal consults in U.S. jurisdictions*

* Case citations for each state are provided as a supplemental appendix.

In the absence of a bright-line test for evaluating the presence of a doctor–patient relationship, 14 some jurisdictions have adopted an expansive approach that extends this relationship beyond the treating physician. For example, several courts have found that on-call and supervisory physicians who did not directly interact with a patient nevertheless had an implied or “special” doctor-patient relationship, resulting in a duty to the patient and potential liability if patients can prove the other elements of their malpractice claim. Some of these courts have explicitly distinguished on-call and supervisory physicians from “true” informal consults, suggesting that they would not be willing to imply a doctor-patient relationship for consults provided only informally as a professional courtesy. Other courts have not addressed the matter directly, leaving open the possibility of an implied relationship (and associated duty) for informal consults. Still others are willing to find a duty only when patients can demonstrate an express doctor-patient relationship. Despite these variations, the key point is that the majority of U.S. jurisdictions require a doctor-patient relationship, whether express or implied, in order to find the duty necessary to support a malpractice claim — and these courts have not found informal consults sufficient to establish that relationship.

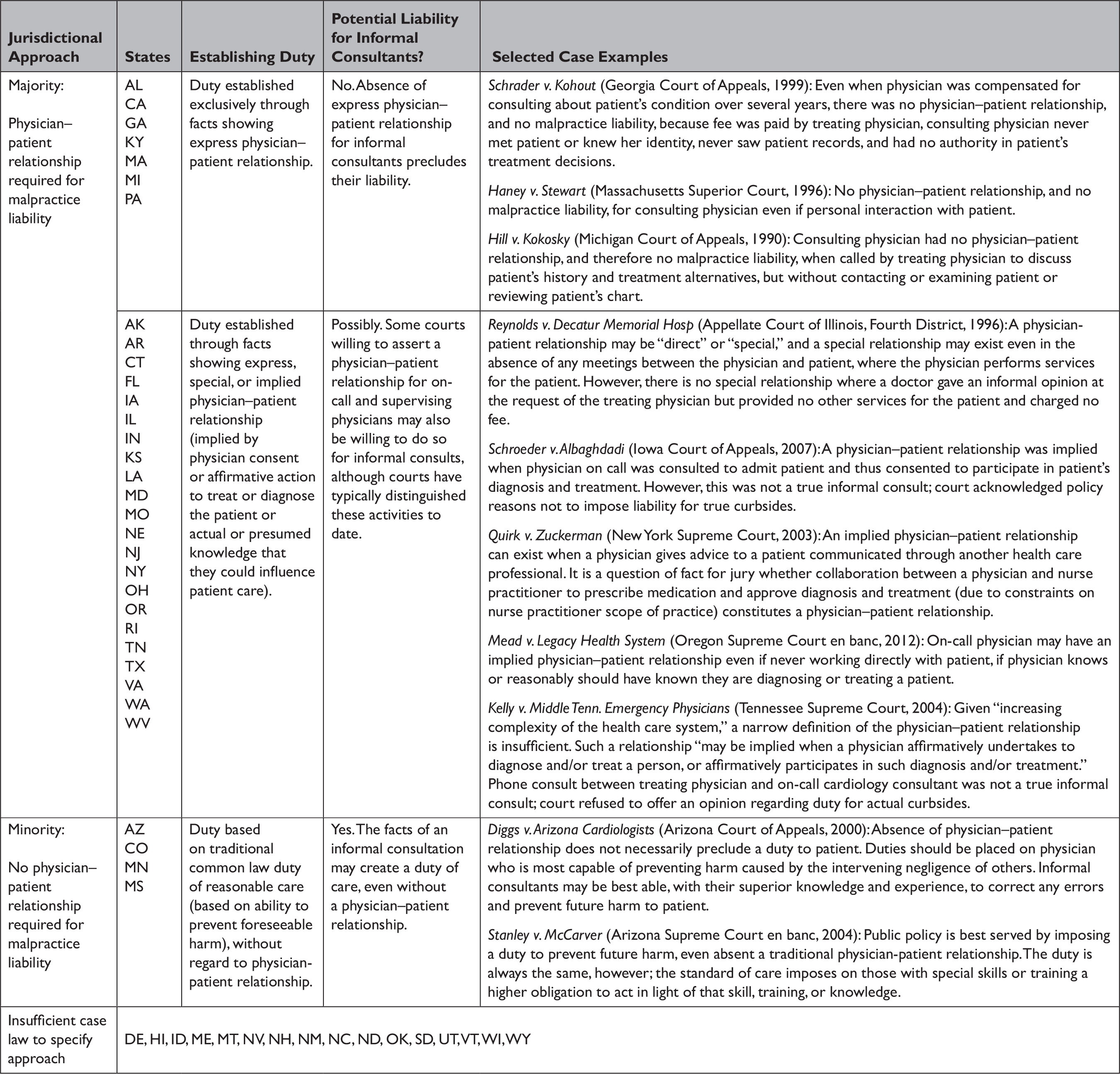

In contrast, a minority of jurisdictions, like Minnesota in Dinter, have allowed patients in malpractice cases to claim that clinicians owed them a duty of reasonable care because the clinician’s actions resulted in foreseeable patient harm. This emphasis on foreseeability, rather than the presence of a doctor–patient relationship, eliminates an important barrier to holding informal consultants liable for unreasonable behavior (Table 2). Importantly, foreseeability does not require certainty of a particular action or outcome — for instance, that the treating physician would definitely follow a consultant’s advice and that it would lead to harm. It requires only that the ultimate outcome was among the set of possibilities the defendant, i.e., the consultant, should have reasonably anticipated.

Table 2. Potential liability outcomes for cases involving informal consults in majority and minority jurisdictions

Shortcomings in Current Legal Approaches

One problem with the majority approach, especially in jurisdictions that apply a stringent definition of the doctor-patient relationship, is that it bars patients from recovering damages from an informal consultant, no matter how egregious the consultant’s advice. These patients can still potentially recover from their treating clinician, and perhaps from other responsible parties, like a health system. However, that may not be possible if the treating clinician was non-negligent in relying on the informal consultant’s harmful advice. For example, imagine that a general pediatrician relied on an informal consult with a neurologist after providing the neurologist with all relevant information, but the consulting neurologist failed to flag a concern that would have been obvious to any competent neurologist (but not to a general pediatrician). The pediatrician may not be liable for malpractice — but the neurologist would also be off the hook because of the lack of a doctor-patient relationship. Absent a rule that it is per se negligent for a treating clinician to rely on an informal consult, it may be possible for a patient in this scenario to be left entirely without remedy despite at least one party behaving unreasonably. Even if the treating clinician shares responsibility for the patient’s harm, perhaps because a reasonable clinician in their position would have sought a formal consult or realized that the informal consultant’s advice was problematic, it is not clear that the entire legal responsibility should fall on the treating physician if the informal consultant’s advice was also insufficiently careful.

Leaving treating clinicians on the hook while fully protecting informal consultants could be viewed as a judicial effort to encourage treating clinicians to prefer formal consults as the safest way to avoid liability if they need additional advice about a patient’s care. However, that approach would fail to differentiate between useful, appropriate informal consults and problematic ones. More importantly, it does not seem to reflect the current reality: despite the majority rule, informal consults are frequent, as discussed in the next section. In that light, failing to hold informal consultants to a standard of reasonable care is troubling because informal consults are in fact taking place, just without legal incentive for informal consultants to provide advice only when they have adequate availability, expertise, and knowledge of a particular case. In fact, offering special legal protections for informal consults while holding formal consults to traditional malpractice standards may encourage consultants to purposefully avoid activities that could lead to the appearance of a doctor-patient relationship, such as asking for additional information or actually examining the patient or their records, even if that is truly what the case calls for. This raises a serious ethical concern that the majority rule will encourage informal consults based on incomplete or inaccurate information.

The minority rule at least acknowledges that informal consultants owe a duty of care to patients who could be foreseeably harmed by their advice, giving patients a chance at successful recovery against them. However, patients will still need to satisfy the other elements of a standard malpractice claim. Most importantly, they will have to establish that the consultant’s unreasonable behavior was a cause of their harm, despite the fact that it was the treating clinician who sought and relied upon the consult. In many cases, judges and juries are likely to treat the consultant’s carelessness as secondary, instead focusing on the question of whether the treating clinician acted reasonably in seeking and acting upon the consult. When the answer is no, the treating clinician would be on the hook under both the majority and minority rules. But when the answer is yes, the treating clinician was reasonable, but the informal consultant was not and that led to the patient’s harm, only the minority rule would allow recovery. This is important because it suggests that wider adoption of the minority rule would not necessarily lead to an overwhelming uptick in liability for informal consultants. They would still have some protection through the requirement to demonstrate causation, but they would not receive the same absolute protection offered by the majority rule.

The Minnesota Hospital Association, the Minnesota Medical Association, and the American Medical Association raised a concern about this reduced level of protection for informal consultants in an amicus curiae brief filed in Dinter. 15 Perhaps, they argued, allowing liability absent a doctor-patient relationship will discourage informal consults (rather than simply encouraging them to be reasonable), thereby “stifl[ing] and discourag[ing] the robust practice of medicine … to the detriment of patient care.” 16 Others also suggested that the court’s decision would lead to the demise of informal consults in favor of more costly formal consultations.Reference Miller 17

However, these concerns rest on a number of unexamined assumptions about the benefits of informal consults. These consults are efficient, accessible, and free, but those features are only true benefits that ought to be encouraged if informal consults are of sufficiently high quality that they can reasonably substitute for formal consults in some contexts. Some reduction in quality may be acceptable in circumstances in which formal consults are difficult, impossible, or unnecessary, but it is not clear that informal consults are limited to those circumstances in practice. In fact, the overall quality of informal consults and the conditions necessary for adequate quality remain uncertain. Thus, while offering special legal protection for informal consults might make sense if we were confident of their value, the grounds for such confidence are uncertain. Moreover, there is no evidence to suggest that adopting the minority standard more widely would have the chilling effect on informal consults predicted by Dinter’s critics.

Open Questions and the Limits of Available Evidence

The decision about the best legal framework for addressing informal consults should be informed by evidence: which approach is most likely to successfully protect patients against problematic informal consults and appropriately compensate them if harm occurs, without unduly impeding the potential benefits of such consults or treating informal consultants unfairly? Unfortunately, there is insufficient evidence to properly address these policy questions.

Informal consults appear to be common. A survey reported in 1998 found that primary care physicians requested an average of 3.2 informal consults per week and subspecialists requested 3.6. 18 Since then, site-of-service and primary care reforms have likely made informal consults more attractive in lieu of formal referrals to specialists. 19 A study based on data collected in 2004 and 2005 found that at one 500-bed hospital in a rural state, there were approximately 1000 informal infectious disease consults in a year, equating to 17% of the infectious disease unit’s clinical work value (measured in the work portion of relative value units).Reference Grace, Alston and Ramundo M 20 Data from a survey published in 2019 indicate that academic radiologists frequently render opinions on imaging performed at outside facilities; many of these are verbal and undocumented in a patient’s record, characteristics that can help distinguish these interactions from formal consults.Reference Mahalingam, Bhalla and Mezrich 21

Overall, contemporary statistics about the frequency of informal consults across specialties are lacking. In addition, the absence of a clear shared definition in the literature of exactly what constitutes an informal consult makes it difficult to collect and evaluate data about them. However, there is reason to hypothesize that informal consults have, if anything, become more common over time due to the proliferation of email, texting, and social media, 22 since these modes of communication expand networks and reduce barriers to connection. Consults conducted via these platforms leave an electronic “paper trail” that could be useful to various parties in establishing relevant facts during litigation, should it come to that, although whether a consult was written or verbal does not necessarily determine whether it will be treated as formal or informal.

Beyond these gaps in the empirical literature, it is also difficult to draw meaningful conclusions about the frequency, scope, or quality of informal consults from reported malpractice suits. Most cases in this genre involve some ambiguity, with the consult falling somewhere between clearly formal or clearly informal. Legal cases involving “true curbsides,” in which the consultant did not directly observe the patient, review their records, or have some professional obligation to take the consult, are infrequent. However, this might reflect the low likelihood of successful litigation in these cases in the absence of a doctor-patient relationship, rather than evidence that patients are not being harmed by informal consults. In addition, drawing conclusions about informal consults based on reported cases may be especially misleading, as patients involved in malpractice litigation may be unaware that an informal consult even took place given that they typically are not documented in patient records. As noted above, however, electronic communications may be discoverable.

Some reports suggest that informal consults can play a useful role in patient care, bolstering access to medical expertise and efficient medical communication. For example, researchers have found increased volumes of informal consults in rural areas, 23 reinforcing the notion that these consults can help connect geographically isolated clinicians and their patients with timely access to specialty expertise. This may also be important in the context of rare disease care or of practice areas facing clinician shortages.Reference Perley 24 In addition, informal consults may increase multidisciplinary collegiality, collaboration, and support for advanced practice providers.Reference Papermaster and Champion 25

Another potential benefit of informal consults is cost savings, although savings on one side of the ledger reflect uncompensated clinician time on the other. Informal consults are free — by definition, consultants do not bill for these services. Accordingly, using informal consults in place of formal consults can help reduce health care spending for patients and payers. The infectious disease consult study discussed above found that a year of informal consults represented at least $93,979 in unbilled services, based on 2005 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services conversion factors. 26 Yet whether this is truly a benefit is unclear, as that depends on whether these amounts are characterized as savings (to payers) or losses (to the clinical practice). Moreover, the value of any savings can only meaningfully be assessed in relation to the quality of informal consults compared with the alternatives.

Relatedly, one important unknown is whether and how the lack of payment affects clinicians’ willingness to spend adequate time and care on an informal consult in order to provide appropriate advice, especially in states where informal consultants do not risk malpractice liability. Without either a financial or legal incentive to perform well, these consults will be guided exclusively by professional ethics — and it is not clear whether that will suffice to produce high quality informal consults given competing demands for clinician attention. On the other hand, the absence of payment for informal consults bolsters the concern that, in the minority of states where liability is currently possible, clinicians may be more hesitant to provide informal consults. Liability risk without compensation is not likely to be a very attractive proposition. Yet the likelihood of liability (if low) and clarity of legal expectations (if high) could presumably influence any such hesitancy, rather than depending exclusively on the mere possibility of liability itself. To our knowledge, there have been no studies comparing clinician willingness to provide informal consults in majority and minority jurisdictions.

Perhaps the most critical gaps in existing evidence have to do with whether and when informal consults should be preferred to formal consults. If informal consults are valued as a matter of necessity because they are possible in circumstances where formal consults are not, then we must consider what makes formal consults impossible and whether that may be changing. In particular, several barriers to telemedicine, including technology gaps, reimbursement constraints, and licensure requirements across jurisdictions, have receded in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.Reference Shachar, Engel and Elwyn 27 As formal telemedicine consults become more widely available, perhaps they should be preferred to informal consults in situations when distance and availability would previously have posed an insurmountable barrier. And if cost is a driving factor in preferring informal consults, then again we need to know about comparative quality to judge whether savings are justified.

With regard to the quality of informal consults, it is unclear to what extent the brevity, second-hand nature of information sharing, and potential gaps in key details compromise accuracy. Research has found that one-half to three-quarters of informal consults are complex in nature, 28 and the most recent prospective study of informal consults found that the information exchanged between treating hospitalists and consulting physicians was inaccurate or incomplete about half the time.Reference Burden, Sarcone and Keniston 29 Unsurprisingly, then, the advice that informal consultants provided in this study was often at odds with that provided in a subsequent formal consultation. 30 However, studies have not identified which aspects of informal consults, such as the experience level of the treating or consulting clinician, the requesting service, or the type of medical issue, among other factors, facilitate or hinder their quality.Reference Bergus, Randall and Sinift 31 They have also not identified the threshold at which an informal consult is best replaced by a formal oneReference Myers 32 or resolved the question of whether an informal consult is preferable to no consult at all when a formal consult is not practicable. These data are needed to understand the optimal roles of formal and informal consults in patient-centered care.Reference Morris, Morris, Kotton and Wolff 33 They are also critical to deciding whether we should prefer tort standards likely to promote or inhibit informal consults, or more ideally, which tort standards will promote appropriate, high-quality informal consults while discouraging those that should instead be formal consults.

Identifying the Best Legal Approach

While we need more evidence about the benefits and drawbacks of informal consults and the impact of different legal approaches on the quality of patient care, existing evidence does not support the view that the benefits of informal consults are so great as to deserve the special protection from liability currently granted in majority jurisdictions. Moreover, without a recognized legal duty of care to the patient, we worry about two scenarios: (1) clinicians unreasonably agreeing to provide an informal consult without sufficient expertise or when it is clear that a formal consult is necessary; or (2) clinicians reasonably agreeing to provide an informal consult but providing unreasonable advice without taking sufficient time or obtaining sufficient knowledge of the patient’s case. Even if treating clinicians are held liable for harm in these cases, the best thing is for the patient to be protected from harm in the first instance through reasonable consultant behavior. Therefore, we maintain that the burden should be on those who prefer the majority approach to demonstrate that it is in fact the better option.

In the meantime, the Dinter standard should be adopted as most protective of patients. When consultants’ actions could foreseeably cause harm to patients, whether engaged in a formal or informal consult, they should be held to a duty of reasonable care. This approach does not guarantee that patient-plaintiffs will prevail, but it will remove an important barrier to recovery, improving the opportunity for patients injured by careless informal consults to be compensated. In addition, the Dinter standard may encourage clinicians to exercise more prudence when offering informal consults. It is also possible that this approach would encourage some clinicians to forgo informal consults altogether — but it is not yet clear that this would be a bad thing.

Going forward, state legislatures could enact statutes that affirmatively assign a duty of care to consulting clinicians on the basis of foreseeable harm. As seen in the amicus briefs filed in Dinter, such legislative action would likely be opposed by powerful lobbying interests, and it would also face the usual complexities and delay that often afflict the legislative process. Yet this approach would also create the opportunity for clinicians, patient advocates, and other interested parties to contribute relevant perspectives that could inform policymakers as they determine the ideal nature and scope of consultants’ duty of care. Rather than the legislative route, state courts in majority jurisdictions could alternatively choose to reject or distinguish prior precedent in favor of the Dinter standard when confronted with relevant litigation. However, this approach would unfairly deprive clinicians of the legal predictability needed to guide their behavior.

In either case, the tort system is at best a blunt instrument with which to address the complex challenges of informal consults. Litigation addresses cases in which patients have already experienced harm and focuses on the errors of individual actors rather than the broader structures that may have contributed to those errors. Those subject to the threat of litigation may react defensively, potentially overcorrecting their behavior in ways that have the opposite of the intended result, for example refusing to provide informal consults altogether even when they may be helpful. In addition, a recent systematic review of studies examining the relationship between malpractice liability risk and health outcomes or indicators of health care quality concluded that “[a]lthough gaps in the evidence remain, … greater tort liability, at least in its current form, was not associated with improved quality of care.”Reference Mello, Frakes and Blumenkranz 34 This finding suggests that neither the majority nor minority approach to informal consults is likely on its own to meaningfully alter patient quality outcomes. Nonetheless, courts (and ideally legislatures) will have to make decisions about these cases and cannot sidestep the question of whether informal consultants should be held legally responsible for the advice they give.

From a normative perspective, the possibility of imposing liability on informal consultants is attractive because it is fair to both patients and clinicians. Patients would no longer be blocked outright from pursuing claims against all those responsible for their harms. Treating clinicians who relied on negligent consults would no longer necessarily bear the full brunt of liability, which could instead be apportioned between responsible parties. And in the event that a treating clinician reasonably (i.e., non-negligently) relied on an informal consultant who behaved negligently, the patient would no longer be left entirely without remedy. Importantly, this approach is also fair to consulting clinicians, who simply would be expected to act reasonably when proffering advice. In our view, a legal standard that allows consultants to behave unreasonably without facing legal consequences — currently the majority position — is itself highly unreasonable.

The reasonableness standard is well established in tort law and is designed to take context into account. 35 For example, what is considered reasonable in a formal consult will differ from what is reasonable in an informal consult, and what is reasonable in an informal consult during normal circumstances will differ from what is reasonable during a public health emergency. The reasonableness standard is capable of accommodating these factors without providing carte blanche for consults that are more likely to harm than to help.

In addition to being flexible, the reasonableness standard is modest. It does not require that every informal consult be transformed into a formal consult, that consultants’ medical judgment be impeccable, or that they become instant experts in whatever questions they are asked. Instead, they must simply seek relevant information suitable to the informal consult, limit opinions to topics about which they have sufficient professional expertise, provide the most accurate advice possible under the circumstances, give appropriate caveats, and decline informal consults if they lack or are unable to obtain necessary resources or information. In short, consultants need only act as others with comparable medical training would act under similar circumstances.

As with all reasonableness standards in law, the specifics of what constitutes a reasonable informal consult will depend upon the circumstances. Important questions include how much information clinicians should be expected to obtain before offering advice in the absence of direct patient interaction, how confident they should be in the accuracy of information they receive from the treating clinician, under what circumstances they should decline consult requests, and when formal consults via telemedicine or in-person visits are preferable. Empirical study regarding factors that influence the quality of informal consults, along with input from clinicians, can inform these norms. As in other legal contexts, precedent developed over time will also help to define the boundaries of reasonable consulting behavior. We appreciate that the uncertainty associated with adopting this legal standard may lead, at least initially, to consulting behaviors that are more conservative than necessary, including refusing to provide informal consults even when offering them may be appropriate. Yet it is not clear that patients in states currently following the minority approach are any worse off than those in other jurisdictions. Should the evidence ultimately demonstrate that reliance on a reasonableness standard is diminishing the quality of care, the legal standard can be adjusted.

We acknowledge that after empirical study, the Dinter standard may not turn out to be ideal. But given the data suggesting that formal consults and informal consults often lead to different advice, the typical expectation in tort law that we owe others a duty of reasonable care when we can foresee that our actions might cause them harm, the low bar of simply expecting informal consultants to behave reasonably, and the fact that the minority rule would allow some patients to recover who are currently barred from doing so, we view widespread adoption of the minority rule as the most desirable stopgap while more evidence is collected. This evidence should fall into several categories: (1) whether, when, why, and how informal consults lead to patient harm and benefit, including queries regarding the expertise of informal consultants, the amount of time spent per consult, the level of information shared, the complexity of the consults, and communication challenges; (2) the circumstances in which informal consults may be adequate and when formal consults should be preferred; (3) awareness of alternative legal standards amongst clinicians; (4) the impact, if any, of those standards on clinician willingness to provide consults, consulting behaviors, the quality of consults, patient clinical outcomes, and patient outcomes in malpractice litigation; and (5) the cost consequences of legal standards that promote formal versus informal consults. With funding and encouragement from both state governments and non-governmental organizations, this research could help inform the selection between alternative malpractice standards to help support the highest quality consults for the benefit of patients.

Conclusion

The Minnesota Supreme Court’s decision in Warren v. Dinter drew attention to the uncertainties surrounding informal consultations sought by treating clinicians, as well as certain empirical claims — made without the benefit of empirical support — about the likely impact of the Dinter court’s approach on future consulting behavior. How should courts handle cases involving informal consults? Will patients be made better off, all things considered, by the majority approach that bars liability for informal consults because of the absence of a doctor-patient relationship? Or does the minority rule better ensure patient well-being by imposing a duty of reasonable care on those whose actions may lead to foreseeable harm? These issues are ripe for rigorous study. We need to better understand the motivations, hesitations, and behaviors of consultants in majority and minority jurisdictions, as well as the benefits and risks of informal versus formal consults, so that we can then pass judgment on whether informal consults should be encouraged. Until that evidence is available, however, legal standards should allow patients to recover against an informal consultant whose unreasonable behavior caused them harm.

Acknowledgments

We thank librarians Andrew Lang and Timothy Von Dulm at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School for assistance with state law research.

Note

Holly Fernandez Lynch reports research support from the Greenwall Foundation. Steven Joffe reports grants from Pfizer, through the University of Pennsylvania and ending in May 2020, outside the present work. The other authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Supplemental Appendix

U.S. Case Law Relevant to Curbside Consults