Introduction

In 1934, five years after the onset of the Great Depression, Raúl Prebisch submitted a proposal for setting up a central bank in Argentina.Footnote 1 One of its main aims was to furnish the proposed central bank with a blueprint for a more proactive monetary policy. The proposal covered banking supervision and rediscount operations, and provided a strategic plan for addressing the ongoing liquidity problems faced by Argentina's commercial banks. In doing so, Prebisch laid out some of his preliminary thinking on the role of counter-cyclical economic policies in peripheral economies such as Argentina's. Thus, the establishment of the Banco Central de la República Argentina (Central Bank of the Argentine Republic, BCRA) in 1935 illustrated the passage to a new era in the development of monetary policy in Latin America.

Argentina had decided against establishing a central bank in the 1920s. Nevertheless, the country shared many of the economic problems faced by other countries in the region that had determined to found central banks during that decade. Prebisch's proposal broke with the received orthodoxy that had hitherto guided the formation of other central banks in Latin America, which had been set up in tandem with a range of fiscal and monetary reforms. In Colombia (1923), Chile (1925), Ecuador (1926), Bolivia (1927) and Peru (1931), such reforms took place on the advice of Edwin Walter Kemmerer, a professor of economics and international finance at the University of Princeton, in his capacity as a foreign advisor. It was hoped that his reforms would contribute to the formation of a stable monetary system based on the gold standard, which would boost economic recovery by expanding domestic credit, encouraging foreign investment and enhancing access to international capital markets.

The first years of the implementation of Kemmerer's reforms were successful. Local currencies were stabilised and government loans were issued in New York and London. These external funds served to bolster the reserves of the new central banks and provided finance for infrastructure projects. Nevertheless, domestic credit remained low, and the new monetary system soon began to show its flaws. While the squeeze on credit was a direct consequence of the deflationary policies introduced to meet the requirements of pegging the currency to the gold standard, the crisis that started in 1929 aggravated the credit shortage in key sectors such as agriculture and industry. Moreover, although most of the central banks recognised the need to act as a lender of last resort, being tied to the gold standard constrained their capacity to offer financial support to commercial banks.

This article analyses the transition from the first to the second generation of Latin American central banks (those established in the 1930s) and presents a comparative analysis of the changes that occurred across the region during this period. Previously, the literature has been focused either on the reforms introduced by money doctors,Footnote 2 or on the case of individual nations.Footnote 3 However, a regional comparison of the history of central banking in the interwar period can yield interesting insights. Overall, I observe that the role of central banks in the economy became one in which credit provision was a central concern, along with the capacity to introduce counter-cyclical monetary policies. While the Great Depression triggered this shift, the economic fragilities that would motivate it – along with new ideas on the role of monetary policy in the economy – had been present earlier in the 1920s in almost every country analysed.

The extensive literature on the gold standard has shown that poor economic performance together with a change of thinking and the weakening of the ‘good housekeeping seal of approval’ were the main factors that prompted governments to leave this monetary regime.Footnote 4 I show that it was the urgent need to facilitate credit – both to the government and to the private sector – that was the major factor in many instances in Latin America. It is also significant that many governments began to express misgivings about their capacity to secure foreign financial support. As I show below, the countries where Kemmerer's policies were implemented appear to have been the most committed to the monetary and fiscal orthodoxy of the 1920s, despite the severity of the economic crisis.

Finally, I analyse the consolidation of proactive monetary policies as governments responded to problems that had been present even before the crisis. I provide a comparison between the central banks founded under the advice of Kemmerer and those proposed by Otto Niemeyer, the British foreign advisor to Argentina and Brazil in the 1930s. I observe similarities but also relevant contrasts between Kemmerer's and Niemeyer's proposed central banks, even though both supported orthodox monetary policies. These were different from Prebisch's proposal, whose approach was finally adopted in Argentina. I also show that Prebisch's project was in line with the monetary policies and central banks’ reforms being independently introduced in other countries such as Chile and Mexico. While this new design of central banking was also the one preferred in Venezuela by the end of the decade, El Salvador's previous experience shows that the paradigm shift was not complete.

Money Doctors and Economic Policies in Latin America

There is a large body of literature on the influence of money doctors on the economic policies in Latin America. Emily Rosenberg and Norman Rosenberg argue that financial advising emerged as an alternative to US colonialism, and served to facilitate the expansion of US investment and trade in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 5 By resorting to private contracting in the sphere of foreign lending, the United States could exert an important influence on Latin American economic policies. The US government initially sent financial advisors to two US protectorates, the Philippines and Puerto Rico, followed by other countries in the Caribbean and Central America as a result of the 1904 Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, which was intended to mitigate European influence in the zone. In countries such as Panama and the Dominican Republic, the establishment of a stable currency system closely linked to the US dollar was prioritised by the US government.

A main controversy concerns the role of foreign advisors as promoters of the foundation of central banks in the region. Rosenberg claims that the systems implemented, based on a gold-exchange standard, did not necessarily foresee the establishment of central banks.Footnote 6 In Central America, Victor Bulmer-Thomas explains that Nicaragua established its national bank in 1912. The government also appointed a US collector-general and introduced a new monetary system based on a gold-exchange standard.Footnote 7 In contrast, this author describes how Arthur Young, the US financial advisor appointed by the Honduras government in 1921, also recommended the adoption of a gold-exchange standard but without including a central monetary authority in his proposal. The government preserved a double regime (gold and silver standards) although maintaining a fixed exchange rate with the dollar.

In the Andean countries, Paul W. Drake provides a comprehensive narrative on Kemmerer's role as the money doctor who recommended the establishment of central banks in the 1920s.Footnote 8 This author suggests that a main reason for the establishment of central banks in Latin America was local politicians’ desire to imitate the monetary organisation of the United States, whose Federal Reserve System had only been established in 1913. Another relevant reason was the belief that following Kemmerer's recommended economic policies would boost the volume of foreign investment in their countries. Barry Eichengreen confirms that the presence of money doctors and the monetary stabilisation that followed also led to an expansion of foreign lending in the region.Footnote 9

The literature also disagrees on the role of foreign advisors in the aftermath of the Great Depression. As we shall see, money doctors continued to be present in various Latin American countries. British money doctors became the main protagonists, as trading connections with Britain remained strong and governments continued to look for external advice. Argentina, for example, was still strongly dependent upon Britain both as an export market and as a creditor.Footnote 10 Richard Sidney Sayers argues that the Board of Trade and the Foreign Office wished to maintain British trade and influence in South America. However, money doctors’ recommendations seem to have lost the relevance they had acquired in the previous decade. Two of the most quoted cases are Brazil and Argentina.Footnote 11 In 1931, Brazil's government appealed to Niemeyer, from the Bank of England, after a severe fall in the Banco do Brasil (Bank of Brazil)'s gold reserves and with the aim of receiving additional external funding. Niemeyer was expected to provide policy recommendations, predominantly with regard to monetary stability and the establishment of a central bank.Footnote 12 Winston Fritsch suggests that Niemeyer's recommendations failed to be implemented because the government perceived that no foreign loans could be obtained.Footnote 13

In Argentina, the government decided to establish a central bank in 1935, as advised by Niemeyer's mission one year earlier. However, the final result has created some controversies in the literature. Sayers suggests that the structure of Argentina's central bank was close to the recommendations made by Niemeyer,Footnote 14 while, according to Florencia Sember, Niemeyer's proposal was profoundly divergent from the one finally adopted, following rather Prebisch's concept of a central bank.Footnote 15 These differences concerned the autonomy of the bank, the composition of its directive board, its supervisory responsibilities, its main purposes and the convertibility of its currency. In particular, Sember claims that a main priority of Niemeyer's project of a central bank was the regulation of the volume of credit and the consequent demand for money in order to maintain the external value of the peso as assigned to it by law. However, the final project prioritised the central bank's capacity to mitigate the consequences of fluctuations in exports and foreign capital investment on money, credit and commercial activities, while maintaining the value of money. These targets were expected to be met through the restriction of credit and the accumulation of gold and currency reserves during the ascending phase of the cycle, so that these could be used during the downward phase.

The Advent of Latin America's Central Banks

In the aftermath of the Great War, the state of banking development in Latin America varied according to the economic requirements of each country and their institutional and political stability.Footnote 16 In Argentina, Uruguay, Chile and Costa Rica, foreign and domestic banks had assumed a prominent role in the credit market, attracting high levels of deposits and channelling capital to domestic ventures and the financing of international trade.Footnote 17 In Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador and Mexico, government intervention (i.e. inflationary financing) and political instability had impeded the development of the banking sector. In Mexico, the Mexican Revolution had forestalled the development of banks, contributing to low economic growth in its aftermath.Footnote 18 In Brazil, the level of domestic credit had fluctuated before plummeting in the first decades of the twentieth century. In 1929, it plunged to 6 per cent of total GDP, estimated to be one of the lowest figures on record in the modern world.Footnote 19

Along with political instability, macroeconomic volatility affected the region's economic performance. By the end of the nineteenth century, most Latin American countries had adopted the gold standard, only to abandon it at the onset of the First World War. Then, during the 1920s, Latin American governments started to succumb to the pressure to return to the gold standard in order to achieve monetary stabilisation. This followed discussions at the International Financial Conferences of Brussels and Genoa of 1920 and 1922 respectively, where it had been agreed that a new monetary system – the gold-exchange standard – would be adopted.Footnote 20 Because the pound sterling and the US dollar were expected to be convertible to gold at a stable rate of exchange, they could serve as the reserve currencies that could substitute for pure gold reserves. In this system, the exchange rates and, therefore, the value of national currencies, had to be stabilised by central banks. These institutions were established around the world with the aim of reorganising financial and foreign exchange systems and encouraging adherence to the gold standard.Footnote 21

The establishment of central banks in Latin America generated heated debates. In countries in which state banks had close relationships with their national governments and enjoyed a monopoly for issuing banknotes, there was strong resistance to the establishment of central banks.Footnote 22 Such were the cases of Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. In Argentina, the Banco de la Nación Argentina (Bank of the Argentine Nation, BNA) allied itself with the political party that had been opposed to the creation of a central bank in 1917.Footnote 23 In Brazil, Banco do Brasil was a state bank with privileges that boosted its profitability, such as its capacity for multi-branching; given that the Brazilian Federal State was its main owner, this was of benefit to the government.Footnote 24 In Mexico, the Banco Nacional de México (National Bank of Mexico) had traditionally acted as the government bank and sought to become the new central bank. It was adversely affected by the government's decision to establish a new institution in 1925, with the new central bank being seen as enjoying too much proximity to the government.Footnote 25 Mexican banking legislation did not require mandatory association with the central bank, and, as a result, initially only two banks chose to become associate banks, reaching five banks by 1929.Footnote 26

In Chile, the debate concerned the diagnosis of Chile's monetary problems and whether the establishment of a central bank was desirable at all. Those who wanted to establish a central bank with strict rules determined by the gold standard were opposed by those who feared the rigidity of this type of monetary system.Footnote 27 Chile's president, Arturo Alessandri, invited Kemmerer to visit in 1922. However, Alessandri was ousted by a military coup two years later. The new de facto government intended to carry out the ongoing financial reforms without continuing parliamentary debate. It is interesting to note that this decision met with little public disapproval. Monetary instability and inflation had already sparked public protest, and Kemmerer's mission was apparently welcomed by many, including the working class. Indeed, labour unions considered that a central bank could halt inflation and improve earnings.Footnote 28

Similar attitudes prevailed elsewhere. In Bolivia, the media referred to Kemmerer as ‘the magician of world finances’ and several articles outlined the benefits that would stem from the proposed financial reforms.Footnote 29 In Colombia, in spite of criticism from the nationalist parties, the most important parties in Parliament welcomed Kemmerer's project. The generally positive reaction derived from the widespread belief that new financial institutions and legislation would serve to bolster the purchasing power of the local currency.Footnote 30 In Ecuador, where prices had been volatile in the years prior to Kemmerer's arrival, several favourable articles were published in the press during the course of 1927.Footnote 31

By contrast, there were those who rejected Kemmerer's proposals. Exporting elites and large landholders were opposed to the introduction of a gold standard, given that currency depreciation could be so advantageous to them; Bolivian mine owners are an example.Footnote 32 In countries such as Bolivia and Colombia, where commercial banknotes had been issued by several private banks, the prospect of centralising this highly profitable activity was met with general opposition. In Ecuador, the proposed reforms caused severe disagreement among groups of regional bankers who held differing views and interests in the country's monetary policy. Nevertheless, after several years of high inflation, the first steps towards the centralisation of reserves and restriction of the capacity to issue currency were undertaken prior to the arrival of Kemmerer through the founding of an institution called Caja Central de Emisión y Amortización (Central Office for Note Issue and Withdrawal).Footnote 33

Domestic coalitions, mainly formed by importers, merchants and consumers hoping to benefit from an increase in credit and a decline in interest rates, initially supported Kemmerer's reforms but began to oppose them as implementation progressed. Drake reports that in all the Andean countries visited by Kemmerer, the major problem was the scarcity and high cost of credit.Footnote 34 The agriculturalists and industrialists believed that central banks could play a similar role to today's development banks by granting long-term loans, something to which Kemmerer was consistently opposed, as he believed that these should be provided by mortgage and commercial banks.Footnote 35 In what follows, I describe the features of the new central banks and the criticism they provoked during the first years of their existence.

Central Banking and Monetary Policy: A General Overview

Constitution of the New Central Banks

There were eight central banks established in Latin America between 1922 and 1931. I show their structure and management in Table 1. In five cases, Kemmerer was the main designer of these new institutions (hence the term ‘Kemmerer countries’), which were created along with new fiscal, banking and monetary legislation in each country. Table 1 includes the ambivalent cases of Mexico and Guatemala, as well as the first central bank of Peru. Kemmerer's mission in Mexico had resulted in a plan to found a central bank in 1917, although the Banco de México (Bank of Mexico) was not established until 1925 and, while it remained close to his original proposal, certain differences could be observed: the proposal had envisaged a mixed private–public ownership, whereas the final version was exclusively publicly owned;Footnote 36 the central bank managed the exchange rate while, very briefly, operating in a gold-exchange regime in tandem with the Ministry of Finance, with whom it shared the responsibility for monetary policy, a feature unforeseen in the original proposal. Despite these differences, contemporaries depicted the creation and evolution of the Banco de México during its first years of existence as following ‘Kemmerer lines’.Footnote 37

Table 1. Central Banks Established during the 1920s: Kemmerer and ‘Kemmererised’ Central Banks

Notes: a Peru's 1922 figures are in Peruvian pounds; in 1931 these are soles. A Peruvian pound consisted of ten soles. b This table does not report the number of substitute members. c However, these positions could only be held by members appointed by the state. d Domestic banks are divided in different categories according to their level of capital (the benchmark volume of capital being 250,000 Peruvian pounds).

Sources: Chile: Texto definitivo de la ley general de bancos. Texto definitivo del decreto-ley núm. 486, de 21 de agosto de 1925, que creó el Banco Central de Chile (Santiago: La Nación, 1947). Peru: Banco Central de Reserva del Perú, Estatutos, aprobados por resoluciones supremas de 5 de junio de 1922 y 24 de febrero de 1926 (Lima: Torres Aguirre, 1926). Colombia: ‘Diario Oficial año LIX. Núm. 19101 y 19102. 16. Ley 25 de 1923’ (Bogatá: Imprenta Nacional, 1923). Bolivia: Banco Central de Bolivia, Estatutos del Banco Central de Bolivia (La Paz: Renacimiento, 1930). Mexico: Banco de México, Ley, escritura y estatutos (Mexico City: Editorial Cultura, 1925). Guatemala: Molina Calderón, El Banco Central de Guatemala.

The only country from Central America represented in Table 1 is Guatemala. Kemmerer visited that country in 1919, even though the final legislation was only implemented seven years later under Enrique Martínez Sobral, who had participated in Kemmerer's missions to Chile and Mexico.Footnote 38 Honduras was another country where a US money doctor, Arthur Young, was present. However, this foreign advisor did not emphasise the need to found a new central bank because the ‘low volume of business’ in the country would have barely justified it.Footnote 39 Young instead recommended the fusion of two of the most important banks, which could operate like a central bank and be the entity responsible for the management of foreign reserves and the government's accounts.

In Peru, the Banco de Reserva del Perú (Reserve Bank of Peru) was founded in 1922 due to the influence of William Wilson Cumberland, a former student of Kemmerer's, who acted as a senior customs collector in the country. During his time in Peru, he maintained regular correspondence with Kemmerer and became a member of the new Banco de Reserva del Perú's board of directors, but resigned in 1924 as no foreign loans could be arranged.Footnote 40 When Kemmerer visited Peru in January 1931, he criticised the central bank's inadequate level of capital, its lack of independence from political influence, and the predominance of one interest group (bankers) on the board of directors.Footnote 41

Central banks owned and administered international reserves, and enjoyed a monopoly for issuing paper currency. The new central banks, whose ownership was a mix of both public and private entities, were intended to be independent and free from political interference, a feature that explains the long duration of the banks’ defined structure and responsibilities. In each country, the government, associated banks and other private stockholders had to contribute to its capital, though levels could vary, as shown in Table 1. The shares were divided into separate groups, each of which were assigned different voting rights. Certain kinds of shares could only be acquired either by banks, the government or the general public. In this regard, Mexico's central bank was the least independent, as the government was expected to hold at least 51 per cent of the total number of shares at any point in time.

In the countries visited by Kemmerer, the amount of capital needed was estimated on the basis of the size of the total population, its reserves and its money supply.Footnote 42 In all cases, there was a minimum reserve requirement for the central bank. This was generally 50 per cent of total deposits and bills issued by the central bank, although Colombia imposed a 60 per cent level. An additional restriction concerned the total amount of loans that could be granted to the government. This could not exceed 30 per cent of the bank's capital, although this amount was adjusted at the onset of the Great Depression. Kemmerer had strongly criticised the high amounts of credit allocated to governments by the banks in charge of issuing currency prior to his arrival. This was the case in the Banco de la Nación Boliviana (Bank of the Bolivian Nation), which was considered to be an agency of the National Treasury.Footnote 43 The newly created banks also had the capacity to pursue operations for the general public as a profit-generating activity. However, these were rarely implemented, as such operations could have introduced undesirable competition to commercial banks, whose representatives sat on the central banks’ boards of directors.Footnote 44

Unlike their counterparts in Mexico, Guatemala and the first central bank in Peru, representatives from the industrial sector, the agrarian sector, the government, commercial banks and labour sat on the boards of directors of Kemmerer's central banks. Having labour represented for the first time was a major achievement. In Chile, Kemmerer claimed that a labour representative could ‘interpret the Bank's activities and policies to labour, who can likewise interpret to the Bank labour's attitude on questions of currency and banking policy’. He concluded: ‘The chief interests of Chile's economic life are represented on the Board of Directors, but no one interest has a majority.’Footnote 45 Meanwhile, both domestic and foreign banks in Colombia were given the capacity to appoint representatives from agriculture and industry, a feature that would be forcefully criticised before it was abandoned in 1930.Footnote 46

As well as being expected to host government accounts and assume the role of clearing houses, Kemmerer's central banks could conduct short-term rediscount operations for limited amounts.Footnote 47 Theoretically, central banks could act as lenders of last resort, granting emergency loans, stabilising the international exchange rate of the currency and managing the gold and convertible currency reserves. This was underpinned by banking legislations that set out the regulatory framework together with the conditions under which the central bank could offer support. In Ecuador, the banking legislation explicitly included a clause for the provision of support to commercial banks in an emergency.

Table 2 shows the main features of the new Latin American central banks compared to the monetary framework of other countries in the region. The first column in Table 2 shows the date when monetary law (referring to the adherence to the gold standard) was introduced. In ‘Kemmerer countries’, monetary laws were accompanied by new banking laws intended to regulate the banking sector and promote credit according to the commercial and industrial needs of the country.Footnote 48 Central banks had to meet two requirements: currency stabilisation through the adoption of a gold-exchange standard, and banking development, with currency stabilisation being the primary target. The Kemmerer missions also founded institutions such as the Banking Superintendent's Office, hosted by the Ministry of Finance, to supervise the central bank and commercial banks, with the intention of guarding the general public against bank failures.Footnote 49

Table 2. Central Banks vs Other Cases: Latin America in the 1920s

Note: a Adherence to gold refers to the monetary law defining the convertibility of the currency.

Sources: Chile: Carrasco, Banco Central de Chile. Colombia: Ibañez Najar and Meisel Roca, ‘La segunda misión Kemmerer’. Mexico: Bett, Central Banking in Mexico. Ecuador: Almeida, Kemmerer en el Ecuador. Guatemala: Molina Calderón, El Banco Central de Guatemala. Argentina: Mónica Gómez, ‘El fin de la Caja de Conversión y el nacimiento del Banco Central: Argentina en la Gran Depresión, 1929−1935’, in Díaz Fuentes et al., Orígenes de la globalización bancaria, pp. 381–410. Uruguay: Benjamín Nahum, Cecilia Moreira Goyetche and Lucía Rodríguez Arrillaga, Política financiera, moneda y deuda pública: Uruguay en el período de entreguerras, 1920−1939 (Montevideo: Universidad de la República Uruguay, 2014).

The banking and monetary systems introduced in Kemmerer countries meant that monetary policy would have to follow the regime's automatic mechanisms. New monetary laws stipulated the adoption of a gold-exchange standard with the establishment of gold parities. Kemmerer preferred the adoption of a gold-exchange standard: it had the same automatic mechanisms as the gold standard,Footnote 50 but it discouraged the hoarding of metallic reserves. The gold-exchange standard was thus seen to be particularly well-suited to economies that ‘did not have enough material resources to guarantee gold circulation and reserves or could not guarantee gold bullion convertibility’.Footnote 51

Credit Provision

One of the main motivations for the introduction of banking reforms in the 1920s was the unsatisfied demand for long-term credit to the private sector. However, given the generalised adoption of the gold standard, deflationary policies were followed during the first years of the new central banks. As a result, these new institutions were unable to meet the general need for capital sought by different productive sectors.

In principle, the rise in credit was supposed to operate through the increased availability of capital that could be lent at reduced interest rates. This could be undertaken through increased competition among commercial banks. In Bolivia, Kemmerer attempted to lower the high degree of concentration in the banking sector. The banking laws that he recommended aimed at facilitating the establishment of new banks.Footnote 52 Furthermore, all Kemmerer's central banks, including Peru's in 1931, established branches with the ability to deal directly with the public.

The disappointment that followed the establishment of central banks developed rapidly in most cases. Several criticisms were raised in favour of a more proactive policy that could facilitate credit to the economy, something that central banks had refused to do prior to the 1930s. Drake reports that in Colombia, agriculturalists, who had initially been in favour of a bank that specialised in providing credit perceived as necessary to support their sector, felt excluded from the credit policy of the newly established central bank, while Chilean agriculturalists also complained about credit shortages.Footnote 53 In Ecuador, Rebeca Almeida reports that a fall in price of the main exports triggered a deficit in the current account after 1927, prompting the central bank to reduce the monetary reserves, although it maintained a level of reserve that largely exceeded the minimum required. Hence, even if discount rates decreased between 1927 and 1929, the central bank forcefully curbed its credit policy. The central bank reacted to criticism that cited the mismatch created by Kemmerer's banking laws and the real necessities of the economy by referring to the fact that short-term credit had to be provided by commercial banks rather than by the central bank.Footnote 54

In certain cases, governments mounted a response to the demand for credit increases through the establishment and promotion of both public and specialised commercial banks. After the central bank was founded in Guatemala, a new bank called the Banco de Crédito Hipotecario Nacional (National Mortgage Credit Bank) was established in 1929, whose main priority was to grant credit to the agricultural sector.Footnote 55 Furthermore, and contrary to ‘Kemmerer banks’, the central bank included an agricultural mortgage department which was granted 25 per cent of the bank's paid-in capital.Footnote 56 In Mexico, a similar bank called the Banco Nacional de Crédito Agrícola (National Agricultural Credit Bank) was established in 1926, one year after the foundation of the central bank.Footnote 57 The same motivation prompted the government to create the Caja de Crédito Hipotecario (Mortgage Credit Bank) and the Caja de Crédito Agrario (Agricultural Credit Bank) in Chile.Footnote 58 As we shall see, complaints about the shortage of credit became even more acute when the effects of the Great Depression deepened throughout the region.

There were also increased demands for credit from the industrial sector. In Peru, the financial sector had concentrated on credit for consumption and imports since the late nineteenth century, and this remained a primary focus until the 1920s.Footnote 59 Juan Franco Lobo Collantes argues that the first initiatives to provide financial support to Peru's industrial sector date from March 1929, following discussions in Parliament.Footnote 60 According to this author, Kemmerer's banking laws affected long-term credit, as commercial banks had prioritised short-term transactions. The lack of credit for this sector, along with that of agriculture, worsened further during the crisis years with the liquidation of the Banco del Perú y Londres (Bank of Peru and London) severely affecting the agro-exporting sector. In response to the pressing needs of the agrarian sector, the first state-sponsored ‘development bank’, Banco Agrícola (Agricultural Bank), was created in August 1931 with funds from the central bank's reserve.Footnote 61 The Banco Industrial (Industrial Bank) was created one year later.

Countries with No Central Banks

In Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, countries without a proper central bank, the leading commercial banks were charged with the provision of rediscount operations to commercial banks, the management of public finances and servicing debt. In all cases, one common target was to maintain a fixed exchange standard, which largely imposed the same kind of restrictions on monetary policy. However, functions such as monetary issuing, banking regulation and even monetary policy were shared with other entities such as the Ministry of Finance (Uruguay) or exchange stabilisation offices (Argentina and Brazil). In Argentina, this conversion office was established in 1899 and acted like a currency board, issuing paper money in exchange for specie at a specified fixed nominal value. A similar entity was created in Brazil in 1906, though it operated within the Banco do Brasil.Footnote 62 In Uruguay, the Banco de la República Oriental del Uruguay (Bank of the Eastern Republic of Uruguay, BROU) held the monopoly on issuing currency, although the quantity of money in circulation and the supervision of commercial banks were controlled by the government.Footnote 63

These countries shared the same problems related to the scarcity of credit to the private sector. In Uruguay during the 1920s, there was persistent criticism of the government and the BROU for not providing sufficient credit to the rural and industrial sectors.Footnote 64 The policy of restricting credit demonstrated that the government's first priority was to bring the country within the gold-exchange standard. In Argentina, Andrés Martín Regalsky and Mariano Iglesias argue that the Banco de la Nación had pursued a counter-cyclical credit policy, in contrast to commercial banks.Footnote 65 Even though the level of deposits had been expanding in the late 1920s, the Banco de la Nación, along with other banks, initially decided to increase its levels of reserves as the balance of payments was favourable. The increase of deposits and reserves ran parallel between 1928 and 1929.Footnote 66 In Brazil, the expansion of credit was also linked to the balance of payments – largely dependent upon the price of coffee – and the capacity of the Coffee Institute to stabilise it. As the balance of payments remained positive, the Banco do Brasil had expanded its lending operations, but the sudden deterioration of the country's external position in 1928 triggered a shift in this policy. This sharp reversal severely affected the private sector, causing a liquidity crunch that required the Banco do Brasil to intervene.Footnote 67

The Impact of the Great Depression

The economic impact of the Great Depression was uneven in Latin America. Table 3 shows real GDP figures for a sample of countries between 1929 and 1933. The decline in economic activity seems to have been more acute in Chile and Peru, while Ecuador experienced a mild slowdown in its level of economic growth.Footnote 68 During that period, economic performance was strongly dependent upon the behaviour of the external sector. Table 3 shows that all countries experienced a slump in the total value of exports, though here again there were important differences among the countries analysed.

Table 3. Current Account and Reserve Losses in Latin America

Sources: GDP and international trade figures are from Montevideo−Oxford Latin American Economic History Database (MOxLAD). Data on reserves are from League of Nations, Statistical Yearbook, various issues.

It is of interest that the decline in exports was not reflected in a deterioration of trade deficits. This is related to commercial policies that aimed to restrict imports as well as contractionary monetary policies. As Table 3 shows, the fall in gold reserves was a prominent feature, suggesting that capital outflows were a major problem during these critical years. As central banks and monetary authorities followed the rules imposed by the gold standard, the monetary base declined accordingly.

The need to defend the convertibility and value of Latin American currencies demanded that the monetary authorities and central banks react with the tools at their disposal. Carlos F. Díaz-Alejandro claims that in Central America and the Caribbean, countries maintained their peg to the US dollar throughout the 1930s, with practically no exchange controls.Footnote 69 However, in the case of Haiti, Guy Pierre argues that this had a strong negative impact on credit and on economic performance.Footnote 70 He reports that US authorities impeded the national bank, whose head office had been established in the United States, to engage in counter-cyclical policies. In countries with central banks, all raised their discount rates to preserve their reserves and currency convertibility (see Figure 1), but this reaction was neither necessarily favourable to economic recovery nor to the needs of the banking sector.

Figure 1. Discount Rates in Latin America

Source: Federal Reserve Bulletin, various issues. Chile's figures are those corresponding to ‘Rediscount Rates to Associated Banks’ as published in the central bank's annual reports.

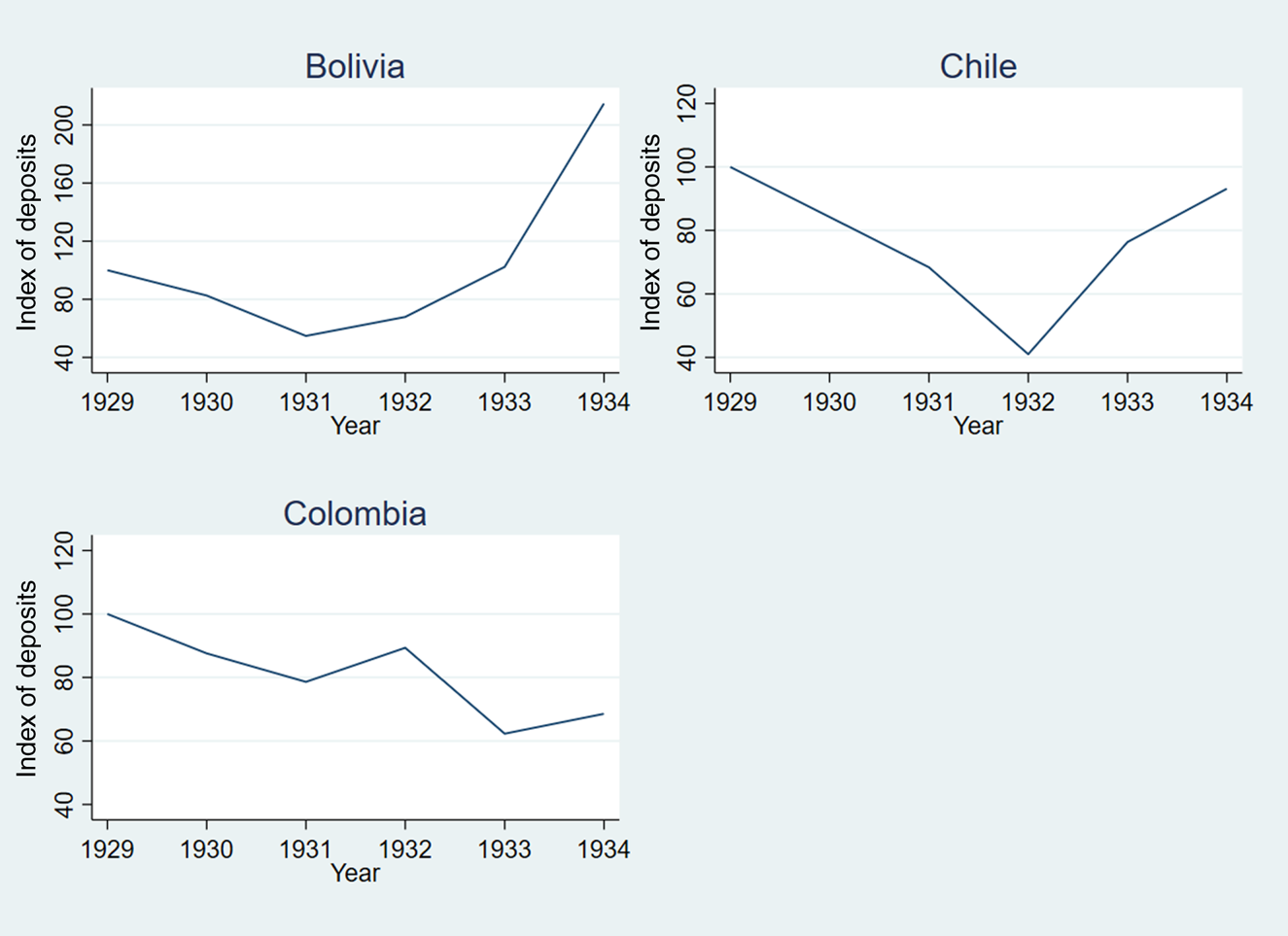

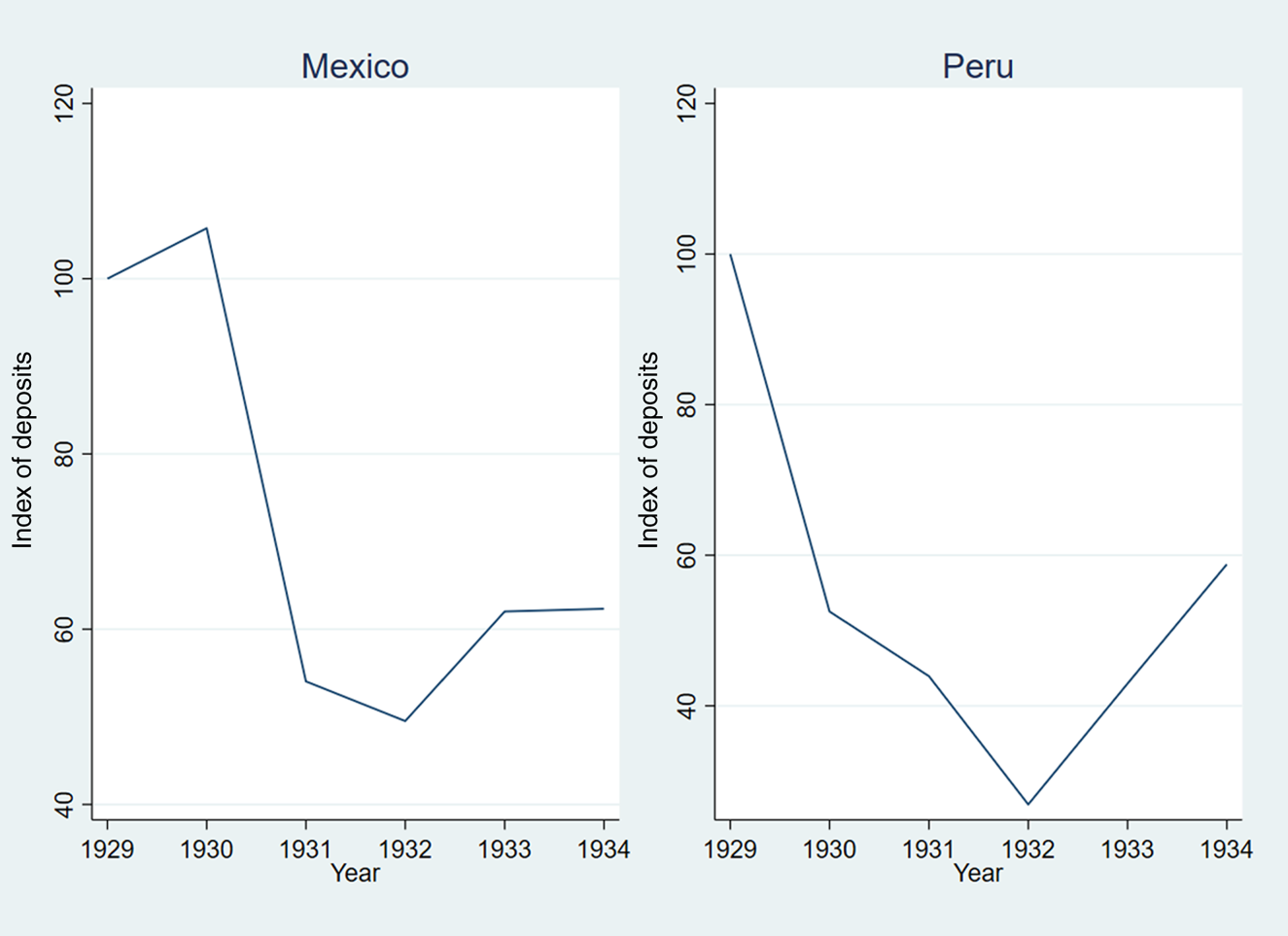

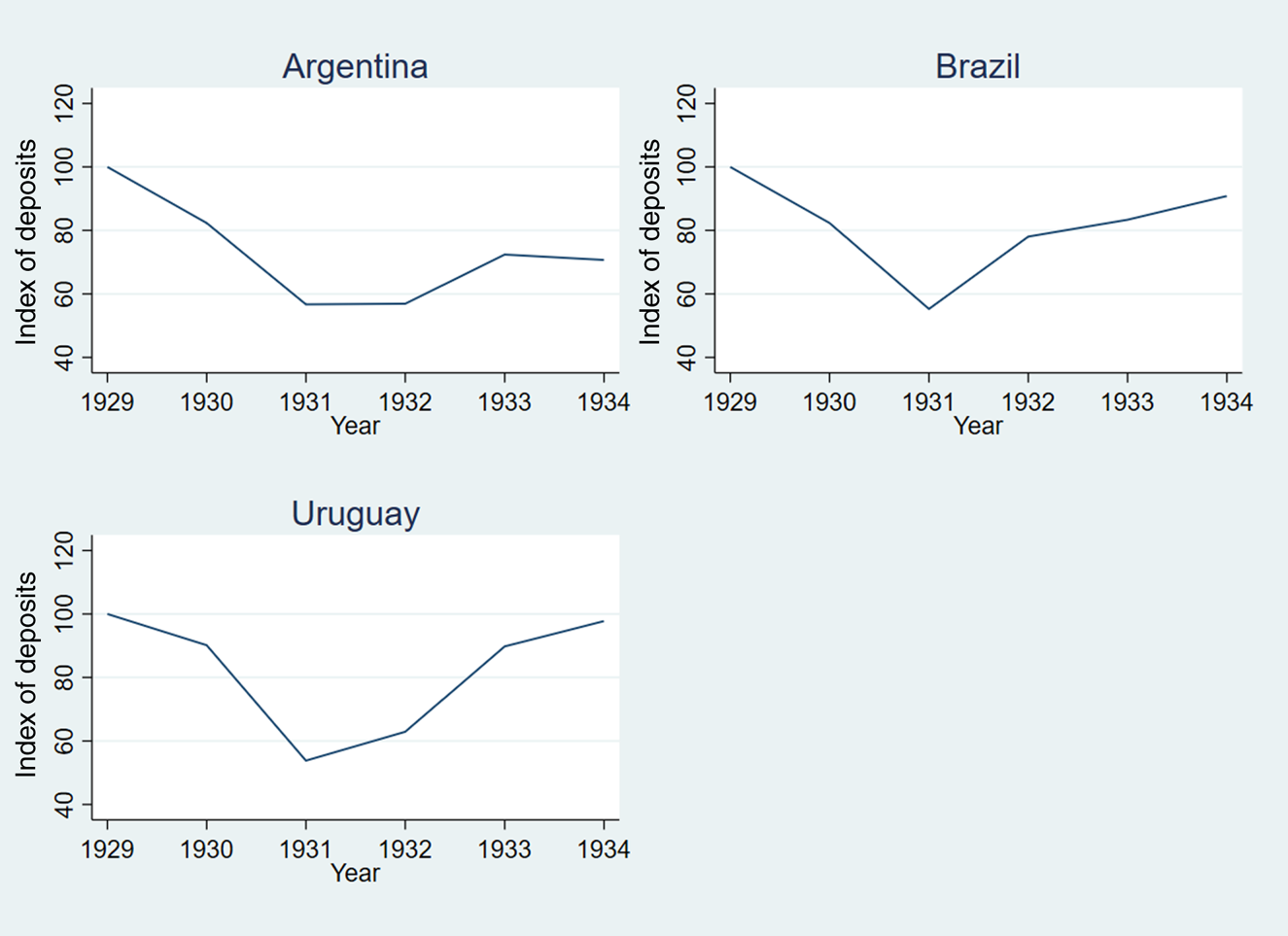

The literature has not entirely assessed the impact that this contractionary policy had on banks. Díaz-Alejandro has emphasised that no widespread banking failures were reported in Latin America during the 1930s.Footnote 71 Ben S. Bernanke and Harold James include Argentina (in April 1931) and Mexico (in July 1931) as the only interwar banking crises that took place in Latin America, but such a perspective is probably misleading.Footnote 72 The banking sector in Latin America was persistently under financial distress, and banking failures and sporadic banking runs were reported in various countries after 1930. Figure 2 shows the generalised fall in deposits in all of the countries analysed.

Figure 2. Fall in Deposits: Commercial Banks

2.1. ‘Kemmerer’ countries

Notes: Deposits are reported in local currency. They were converted to dollars using the exchange rates published in the source below. Indexes are estimated utilising 1929 = 100.

Source: League of Nations Statistical Yearbook for 1937.

Figure 2. 2.2. Countries with Central Banks

Figure 2. 2.3. Countries without Central Banks

In Mexico, the central bank's charter provided several mechanisms through which the bank was allowed to support associated banks.Footnote 73 However, even if the central bank was legally prevented from supporting non-associated banks (which were the vast majority), Virgil Marion Bett argues that it helped several banks to weather the storm.Footnote 74 The minutes of the board of directors show that during 1931 the central bank conceded several loans and rediscount operations to associated and non-associated banks.Footnote 75 They also show, nevertheless, that the central bank, given its own fragile position, was extremely careful about the credit granted to the banks in distress.Footnote 76 In the case of the Banco de Sonora (Sonora Bank), an important bank in the north of the country and whose problems were directly linked with the banking crises in the United States, the central bank feared the possibility of a systemic banking failure in the region, prompting it to support the bank.Footnote 77

In Peru, a first banking crisis hit after the military coup in August 1930, when the Banco del Perú y Londres faced a massive run on its deposits in October 1930.Footnote 78 The bank was in a delicate situation as it had a close relationship with the deposed government, and public suspicion on the misuse of funds triggered the panic.Footnote 79 While this bank was the most important in the country, the whole banking system was particularly fragile as it operated without proper regulation. The Banco de Reserva del Perú's annual report for that year does not provide further details about the support provided to Banco del Perú y Londres. The same report for the previous year shows that the bank absorbed around one-fifth to one-quarter of total loans and discount operations within the banking sector.Footnote 80

In Chile, the minutes of the central bank's directorate show that gold outflows had prompted it to increase its discount rates during the first months of 1931 and had also raised concerns regarding the effects of deposit withdrawals from commercial banks.Footnote 81 The central bank had not only raised interest rates, but also rationed the total amount of rediscounts despite the negative effect this had on banks. The directorate perceived that the risks to the country's banking and monetary situation were the deterioration of the balance of payments and the fiscal position of the government; it also regretted that the bank had no tool other than the rediscount rate to forestall the decline in gold reserves.Footnote 82

Policy Shifts and External Constraints

The initial reaction of governments and central banks was to avoid the fiscal deficits that accompanied the economic slump and to follow the rules of the gold standard. While the crisis was at first considered to be transitory, alternative solutions were sought when exports continued falling, disequilibria in public finances became acute and access to foreign capital markets proved complicated.Footnote 83 One of the solutions involved a renewed round of visits from money doctors, which saw Kemmerer in Colombia in 1930 and in Peru during the first months of 1931.

The Conference of South American Central Banks in Lima in December 1931 served to raise the mood. It was initially convened by Bolivia's central bank in the aftermath of the British sterling pound's departure from the gold standard. The participants of the conference included representatives from Colombia, Chile, Peru and the United States. Five main issues were discussed: the diminution of gold reserves, the consequent reduction of the circulating medium, the forced restriction of credit, debt defaults leading to capital outflows, and effective remedies to mitigate the effects of the crisis.

The memorandum sent by Bolivia's central bank to the conference participants stressed the problem of the restriction of credit. The document raised concerns regarding the rules of the gold-standard regime, particularly when there was an unfavourable position in the balance of payments, as this could trigger excessive pressures on the monetary supply, thereby causing violent deflation and generating economic and social turmoil.Footnote 84 Among the solutions proposed in the memorandum, one related to assistance from the Federal Reserve Board to provide credit ‘that it would grant us and on conditions adjustable to the existing circumstances’.Footnote 85 Other solutions directly involved the monetary regime, such as those having the ‘object of giving greater elasticity to paper money’.Footnote 86 During the conference, the main topic discussed was the preservation of the gold standard and its implications for central banks’ operations during the crisis. These included the central banks’ capacity to face balance of payments imbalances and the need by governments to avert fiscal deficits. The discussions also referred to the criticisms raised in the central banks’ respective countries that restrictive monetary policies aggravated the Depression.Footnote 87 The final communiqué from the conference showed the willingness of Kemmerer central banks to cooperate and remain on the gold standard.Footnote 88 However, as a British observer reported to the Foreign Office, what the [South] American ‘Bankers really wanted were further loans from New York or […] to persuade the Federal Reserve Bank to extend credit over longer periods’.Footnote 89

The onset of the Great Depression coincided with turbulent political times in Chile, Colombia and Peru. As reported by the UK's Overseas and Foreign Department, the severe orthodox policy pursued by South American central banks and the fiscal needs of the governments eventually altered central banks’ charters.Footnote 90 The effects of the economic crisis had prompted governments to introduce agricultural and public works programmes. Furthermore, three of the five Kemmerer countries were engaged in wars. Therefore, central banks saw their statutes being modified during 1931 to meet the demands for credit from both the government and the private sector. In 1933, a memorandum at the Bank of England summarised the main reforms in some of these countries. The document showed how Chile's central bank was permitted to purchase a broader set of financial assets to allow it to purchase bonds from the government. The bank also raised its legal limit of advances to the government from the previous 20 per cent to 80 per cent of its capital and reserves. The minimum gold reserve was reduced from 50 per cent to 35 per cent. The memorandum, published in January 1933, reproduced the monthly report on credit and business conditions of the central bank, in which it lamented that the central bank had been converted ‘into a bank of issue under Government control’. The memorandum also reported that similar measures had been introduced in Colombia and Ecuador.Footnote 91

The initial and orthodox reactions of Latin American governments did not mean that they were unaware of the problems that persisted in their economies. In Colombia, the demands from different sectors of the economy favoured an expansionary monetary policy.Footnote 92 In the case of Mexico, Alberto Pani, who had acted as secretary of finance since 1923, promoted pension and banking reforms designed to increase domestic savings and credit.Footnote 93 In fact, as stressed by Rosemary Thorp, the need for state intervention, particularly regarding banking development, had been present long before the Great Depression, although the event permitted, rather than created, the new economic paradigm that would emerge during the 1930s.Footnote 94 In Peru, Alfonso W. Quiroz reports that Kemmerer's mission produced a set of documents recommending a new banking regulation, central bank reorganisation, a return to the gold standard, and tax reform.Footnote 95 Even then, Quiroz argues that most of these measures were either not implemented or were modified in a direction contrary to Kemmerer's recommendations, thereby expanding central bank loans to governments and allowing the agrarian export sector to strongly influence the country's financial policy.

Figure 3 shows the dates on which a sample of Latin American countries left the gold standard, and the ratio of gold reserves to the issue of banknotes when this decision was implemented. Figure 3 confirms that the low level of reserves was not necessarily the main variable explaining the decision to abandon the monetary regime. As Kemmerer himself argued: ‘A number of these countries which went off the gold standard had large amounts of gold.’Footnote 96 Interestingly, the countries without a central bank were those that left first, even though the level of reserves was still relatively high. On the contrary, countries under ‘money doctoring’ were those that left last. Pablo Gerchunoff and José Luis Machinea argue that in Argentina, the political weakness of President Yrigoyen prompted him to react and prevent recessive pressures on the economy, despite the risks that such a decision might have entailed.Footnote 97 Argentina and Brazil were among the first countries to offer discount facilities to their banking sectors in unorthodox ways. The reaction in Brazil to the Great Depression included the provision, in 1930, of rediscounting facilities through the Carteira de Redesconto (Rediscount Portfolio). This policy was complemented in 1932 by making available the reserves of the Caixa de Mobilização Bancária (Banking Mobilisation Office). In both countries, conversion offices facilitated discount operations and each established an Instituto Movilizador de Inversiones Bancarias (Investment Banking Mobilisation Institute).Footnote 98

Figure 3. Gold Reserves to Note Issue Ratio and Abandonment of the Gold Standard

Note: Index of gold reserves to note issues, base year is 1928 = 100.

Sources: League of Nations Statistical Yearbook for 1934 and 1937. Dates for countries leaving gold standard: Federal Reserve Monthly Bulletin, various issues.

Central Banks in the 1930s

While the first countries to seek external support had been the ‘Kemmerer countries’, they were not alone. Within the government of Mexico, the promoters of the gold standard had been in contact with the foreign monetary advisor although no formal invitation was sent.Footnote 99 In Uruguay, H. A. Lawrence (from the bank Glyn, Mills and Company) provided policy recommendations to face the economic crisis, while basically exhorting the government to adhere to the gold standard.Footnote 100 An unsigned report at the Bank of England, dated 25 October 1935, justified Uruguay's decision not to establish a central bank due to the president's unwillingness to relinquish control of the currency.Footnote 101 British missions were sent to Brazil, Argentina and El Salvador, and provided the structure and design of central banks. While the government in Brazil did not implement the recommendations of the mission led by Niemeyer, it is interesting to compare the design of these banks with those conceived by Kemmerer and also with the one being established in Venezuela, whose government designed a new central bank after considering previous experiences in the Americas.

In an attempt to maintain British trading connections and financial influence, the Bank of England had constantly monitored central banks in Kemmerer countries.Footnote 102 In an unsigned report at the Bank of England, dated 25 May 1933, the author signalled that these institutions were not suitable for the conditions in Latin American countries. In particular, the document argued that the financial reserves of these countries were completely dependent upon the export trade of a few primary products. Exchange volatility was thus part of the economy and not necessarily a source of major concern. The report also referred to the insistence upon balanced national budgets, which were rarely achieved, and the consequent problems of public debt. Finally, the report addressed the problem of political interference in central banks with governments turning to central banks for financing due to the crisis. The report noted that the original laws had foreseen that governments would hold bank shares and nominative powers for a certain number of members of the boards.Footnote 103

Niemeyer did not agree with the main claims of the document. He warned that the advice given by Kemmerer did not ‘provide sufficiently for practical dangers or local administrative conditions’ while admitting that ‘his results cannot be fairly estimated on the present crisis’.Footnote 104 Niemeyer also criticised the fact that South American governments held shares in Kemmerer central banks, something with which he strongly disagreed. It would appear that Niemeyer's position was not so different from Kemmerer's. Some years before, Kemmerer had claimed that the principal objective of a central bank – which he defined as a quasi-public institution – was to protect the standard of value and to conserve the financial interests of the entire public.Footnote 105 While he did not normally advocate that governments should invest in the stock of a central bank, he insisted that sometimes an initial investment was necessary for the creation of one that was strong.Footnote 106 Regarding directors, the government, ‘representing the broad public interest, should have a substantial representation, regardless of whether it owns stock in the [central] Bank or not’.Footnote 107

This difference can be observed in Table 4. Other differences include the nomination of members of the board of directors (more comprehensive in Kemmerer's banks) and the relative amount of capital. Niemeyer favoured low levels of capital (contrary to Kemmerer) as he believed that ‘large capital necessitates large profits in order to meet dividend charges’, thereby distorting the activities of the bank.Footnote 108 He did however echo Kemmerer in his emphasis on monetary stability as a central bank's main target. Kemmerer was even quoted in Niemeyer's report to Brazil regarding the need for central banks to avert ‘undue political and governmental influence’.Footnote 109

Table 4. Central Banks Established during the 1930s: Niemeyer and Other Banks

Note: a President and vice-president not included.

Sources: Argentina: Niemeyer, ‘Informe’. Brazil and El Salvador: BoEA, files OV9/294 and OV20/8, respectively. Venezuela: Egaña, Documentos relacionados.

Niemeyer's visits to Argentina and Brazil generated heated debates among politicians and in the press. In the case of Brazil, Thiago Gambi argues that Finance Minister José Maria Whitaker did not in principle oppose the idea of establishing a central bank, while President Getúlio Vargas had been indifferent, given the lack of financial support from Britain. In the same circles there were also doubts about Brazil's capacity to establish a fixed exchange rate as well as the government's ability to balance its fiscal position.Footnote 110 In the case of Argentina, debates on the different proposals to establish a central bank had begun in 1931, with one of the Congress’ criticisms of Niemeyer's proposal being that it did not consider the delicate position of the (commercial) banks.Footnote 111

Table 4 also shows the cases of El Salvador and Venezuela. In El Salvador, Frederick Francis Joseph Powell, who had assisted Niemeyer in his previous missions to Argentina and Brazil, had initially considered a currency board, although Niemeyer seems to have been opposed to one due to local politics.Footnote 112 The mission recommended converting one of the issue banks, the Banco Agrícola Comercial (Commercial Agricultural Bank), to make it operate as a central bank under the same parameters as those proposed in Argentina and Brazil. A major innovation was the capacity of the central bank to provide credit to the coffee sector, as it was recognised that the country was very dependent upon its performance, and the bank's credit policy would therefore have an immediate impact on the monetary supply.Footnote 113

In other countries, central banks had been modified and new credit programmes had been implemented. Chile is an illustrative example. Guillermo Subercaseaux, governor at the Banco Central de Chile (Central Bank of Chile) from 1933, had already expressed certain misgivings about orthodox central banks and also the gold standard. He claimed that the stability of a currency's purchasing power was relevant and could be pursued without adhering to the gold standard.Footnote 114 He also explained that the recommendations provided by Kemmerer during the Lima conference of 1931 regarding the use of open market operations to regulate the monetary base were not suitable for Latin American countries given the lack of development of banking acceptances, as was the case in the United States. In his opinion, undertaking open market operations of other financial assets with much more volatility was not advisable.

Chile's government had initiated attempts to boost the flow of credit to the industrial and agricultural sectors. Initially, the government had requested that the central bank provide low-interest credit to development institutions, even though this rendered the management of monetary policy difficult. This was illustrated by a credit request by a major nitrate company, the Compañía de Salitre de Chile (Chilean Nitrate Company, COSACH). This request triggered an intense debate within the directorate of the bank as to the advisability of continuing this credit policy, as it generated unnecessary increases in the monetary issue.Footnote 115 The new banking law allowed the central bank to guarantee the credits granted by commercial banks to this sector, thereby reducing the interest rates attached to the loans and preventing the bank from using its own resources,Footnote 116 which were those that were in excess of their reserve requirements at the central bank.

The case of Venezuela seems to have followed the same trend. As discussions were launched in 1937 to establish a central bank, a mission was sent to visit the United States, Canada, Argentina, Chile, Peru and Colombia. The head of Venezuela's mission, Minister of Development Manuel Egaña, considered that the Federal Reserve System did not offer a relevant example for Venezuela, contrary to that of Canada, whose economic structure was more similar to its own. Egaña was also critical of the design of central banks in Peru and Colombia. The mission to Chile met with Hermann Max, head of research at the central bank, who had been recommended as an advisor to Venezuela's government by Subercaseaux. Max was also a strong critic of the gold standard, and he insisted that the problem was not the structure of a central bank per se, but rather the international monetary system. When Venezuela created its own central bank in 1939, the main objective was defined as ‘regulating the monetary supply to adjust it to the legitimate needs of the national market’ and ‘monitor the value of the currency, in terms of purchasing power and in relation to foreign currencies’.Footnote 117

Conclusion

The argument raised by Eichengreen and Peter Temin regarding the ‘change of mentality’ towards the gold standard delineated a global phenomenon that led to reforms and the emergence of new actors and ideas.Footnote 118 As these authors note, a major policy reform in the United States was the 1935 Banking Act that sought to promote the ‘stability of employment and business’ and new actors were appointed to conduct the monetary policy of the country. In 1936, as discussions were taking place regarding candidates to become new members of the board of governors of the Federal Reserve, Kemmerer was suddenly dismissed. The prime reason for this was his allegiance ‘to the old-fashioned gold-standard’ while ‘money doctor’ to various nations. ‘In this Depression he has only warned against inflation, never against deflation.’Footnote 119

As this article demonstrates, money doctors did not revise their prescriptions given the new circumstances generated by the Great Depression. Even if Kemmerer's central banks succeeded in bringing a halt to extended periods of high inflation, they were unable to adapt to the changing needs of Latin American economies. Kemmerer's commitment to monetary stability and the gold-exchange standard failed to adjust to the extraordinary events triggered by the world's economic crisis. As I have shown, the remedies proposed by Niemeyer were not radically different. The plans elaborated for Brazil and Argentina in the 1930s aimed for a return to the gold-exchange standard, without assigning the function of banking supervision to the central bank, which was envisaged as having a mostly passive role. In both cases, Niemeyer's proposals advised the establishment of central banks that resembled, to a large extent, their counterparts in Kemmerer countries.

In a sense, an implicit message of this article is that economic crises may also serve to implement innovative polices once it is evident that dominant paradigms have expired. Latin American economists, increasingly concerned with concrete problems, were well positioned to react to the particular conditions of the 1930s. For example, Prebisch, forced by the pressure of local and international circumstances to reject Niemeyer's advice, conceived a project that was intended to meet the urgent needs of the country, resulting in a bank that was allowed to conduct open market operations, supervised private banks and was primarily engaged in implementing counter-cyclical operations.

It is interesting to note that similar economic policies were being introduced in other countries. In Mexico, Manuel Gómez Morín, who participated in the conception of Mexico's central bank in 1925, championed the introduction of a new set of laws in 1932, some of which were intended to strengthen the relationship between the central bank and commercial banks by facilitating rediscount operations while others aimed at fostering private credit.Footnote 120 He would serve as foreign advisor to Ecuador in 1938.Footnote 121 Max, a Chilean economist at the central bank who was critical of the gold standard, also advised Costa Rica (1936) and remained an advisor to Venezuela for several years.Footnote 122 While the paths of Latin America's central banks and monetary systems maintained a strong degree of diversity in subsequent decades, we might consider these attempts at adapting foreign economic policies to local needs as foreshadowing subsequent institutional efforts that materialised with the founding of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) in 1948. This international body would later lead a collective effort to promote ideas and policies anchored in the region's economic and social context.

Acknowledgements

I thank Adriana Calcagno for her contribution to a first and preliminary draft of this article, and also Franco Lobo and Laura de la Villa Alemán for excellent research assistance. I am grateful for the comments received from Carlos Marichal, Eric Monnet, Gianandrea Nodari, from participants of the Seminar of International History at El Colegio de México in October 2018, from participants at the conference on ‘The Birth of Central Banks: Building a New Monetary Order’, held at the Bank of Greece, Athens, on November 2018, and three anonymous referees. I am also grateful to Aurora Gómez Galvarriato Freer for fruitful conversations on the history of Mexico's central bank, and Florencia Sember, Luis Salcedo Gutierrez and Guy Pierre for sharing primary sources and references. I am especially thankful for the kind cooperation of librarians at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library at Princeton University, Romina Oses at the Central Bank of Chile and archivists at the Bank of England Archives. The usual disclaimer applies. Financial support from Humanities in the European Research Area – HERA Joint Research Programme 3 ‘Uses of the Past’ is gratefully acknowledged.