Introduction

Structurally, the paranasal sinuses can be normal, small (hypoplastic) or large (megasinus or pneumocele), but their size may decrease or increase over time. An example of this increase is pneumosinus dilatans, and an example of its decrease is chronic maxillary atelectasis.Reference de Dorlodot, Collet, Rombaux, Horoi, Hassid and Eloy1 Chronic maxillary atelectasis is an unusual and underdiagnosed entity of permanent and increasing reduction in maxillary sinus dimensions that results in an antral wall collapse. Chronic maxillary atelectasis was first reported in 1964 by Montgomery, but the term ‘chronic maxillary atelectasis’ was first described in 1997 by Kass et al.Reference Montgomery2,Reference Kass, Salman, Weber, Rubin and Montgomery3 Kass et al. also classified chronic maxillary atelectasis into three progressive grades in accordance with the level of sinus wall collapse.Reference Ho, Wong, Gunaratne and Singh4

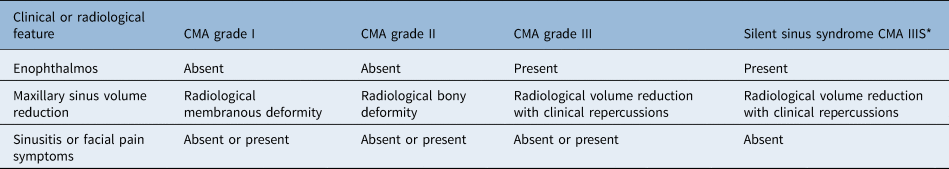

Previously, other terms have been used for this entity in the literature, such as imploding antrum, silent sinus syndrome and acquired maxillary sinus hypoplasia. In 1994, Soparkar et al. used the term ‘silent sinus syndrome’ to describe their cases with spontaneous enophthalmos and unilateral collapse of the maxillary sinus in the absence of sinonasal symptoms.Reference Soparkar, Patrinely, Cuaycong, Dailey, Kersten and Rubin5 Although silent sinus syndrome and chronic maxillary atelectasis are still mentioned separately in studies, de Dorlodot et al. showed that the only distinction between grade III chronic maxillary atelectasis and silent sinus syndrome is the presence or absence of sinusitis symptoms. Diagnostic criteria for chronic maxillary atelectasis and silent sinus syndrome are described in Table 1.Reference de Dorlodot, Collet, Rombaux, Horoi, Hassid and Eloy1 In addition, maxillary sinus hypoplasia is congenital and is included in the differential diagnosis of chronic maxillary atelectasis, so it should be distinguished from maxillary atelectasis.Reference Gunaratne, Hasan, Floros and Singh6

Table 1. Staging of chronic maxillary atelectasisReference de Dorlodot, Collet, Rombaux, Horoi, Hassid and Eloy1

* Our unified classification. CMA = chronic maxillary atelectasis

Chronic maxillary atelectasis has generally been described as a rare and unilateral entity; bilateral chronic maxillary atelectasis cases, as reported in the literature, are extremely uncommon.Reference Ho, Wong, Gunaratne and Singh4 We believe that there are a lack of data regarding chronic maxillary atelectasis prevalence in the literature. This radiological study investigated the prevalence of chronic maxillary atelectasis encountered in our tertiary hospital. In addition, we aimed to determine whether the bilaterality of this entity is as rare as previously mentioned.

Materials and methods

This research was conducted in our university hospital between January 2016 and January 2020. The ethics committee of the university approved the research protocol (date: 26 April 2021; approval number: 187). This research was conducted in accordance with the international ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration.

Patient selection

Our study included 5835 patients who underwent paranasal sinus computed tomography (CT) for the examination of rhinological or orbital complaints.

Paranasal CT examinations were performed on a 128-slice CT scanner (Somatom Definition; Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany), with approximately 120–180 images per CT study. All paranasal sinus scans covered from the roof of the frontal sinuses to the maxillary alveolus just below the hard palate, on the axial plane. The imaging parameters were: tube voltage = 80 kVp, tube current = 120 mA, slice thickness and reconstruction interval = 1 mm, pitch factor = 1, matrix size = 512 × 512, field of view = 14 cm × 17 cm, window width = 2000 HU, and window level = 400 HU. Reconstructed images of coronal and sagittal planes were generated using the separate workstation system.

One radiologist and one ENT specialist evaluated all of the paranasal sinus CT scans. Cases that met the criteria for radiological chronic maxillary atelectasis, such as inward bowing of at least one of the sinus walls and an opacification of the sinus antrum, were included in the study group. Cases with previous facial or orbital trauma (including sinus surgery), congenital facial deformity (such as maxillary hypoplasia) and other causes of enophthalmos were excluded. Data were collected from patients’ charts.

Statistical analyses

Data were transferred to SPSS version 23 software (IBM, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and statistically analysed. Before proceeding to the statistical analysis, controls were made to ensure the absence of data entry errors and confirm that the parameters were within the expected ranges. Regarding descriptive statistics, mean and standard deviation values were calculated for continuous variables, and prevalence (n) and percentage values were determined for categorical variables. Relationships between categorical variables were examined by chi-square test analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was accepted as significant in all analyses.

Results

Demographic features and clinical characteristics

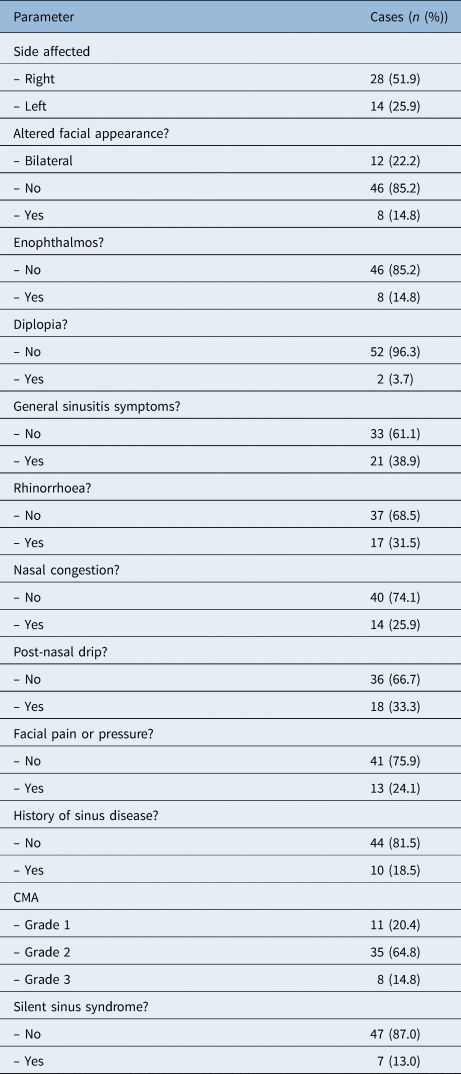

The CT scans of 5835 patients were evaluated; 54 of them were diagnosed with chronic maxillary atelectasis. The mean age of these 54 patients was 42.98 ± 18.89 years (range, 18–85 years); 17 patients were female and 37 patients were male. Chronic maxillary atelectasis was unilateral in 42 patients (28 right, 14 left) and bilateral in 12 patients. Eight patients were found to have enophthalmos with apparent facial asymmetry. Two patients had diplopia.

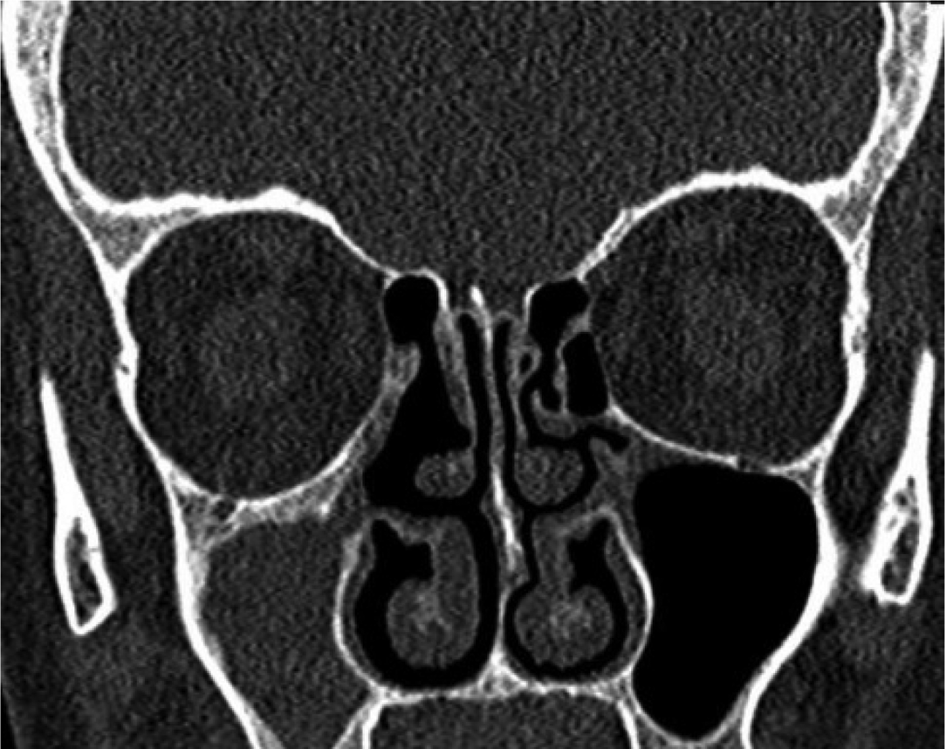

General symptoms of sinusitis were present in 21 patients and absent in 33 patients. Eleven patients had grade I (Figure 1), 35 patients had grade II (Figure 2) and 8 patients had grade III (Figure 3) chronic maxillary atelectasis. Seven patients met the silent sinus syndrome criteria; one patient with chronic maxillary atelectasis grade III was symptomatic and therefore not considered to have silent sinus syndrome. Table 2 reports the clinical features.

Fig. 1. Coronal computed tomography scan of the paranasal sinus demonstrating lateralisation of the right uncinate processes (grade I chronic maxillary atelectasis).

Fig. 2. Coronal computed tomography scan of the paranasal sinus demonstrating inward bowing of the sinus walls and opacification of the sinus (left) (grade II chronic maxillary atelectasis).

Fig. 3. Coronal computed tomography scan of the paranasal sinus demonstrating downward displacement of the orbital floor and right maxillary sinus opacity (right) (grade III chronic maxillary atelectasis).

Table 2. Clinical features

CMA = chronic maxillary atelectasis

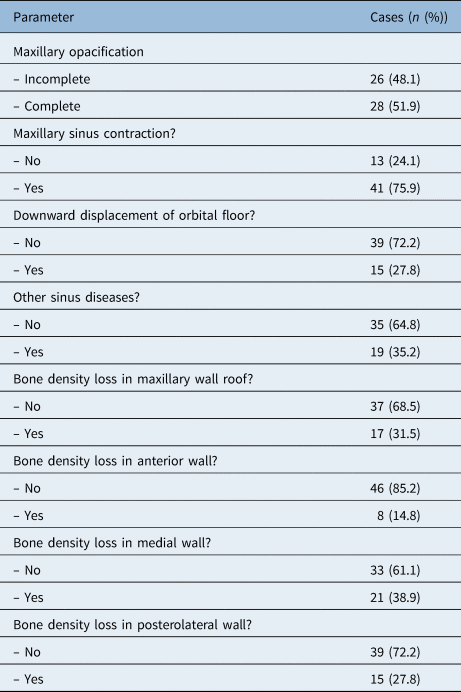

Radiological features

Maxillary sinus opacification was complete in 28 patients and partial in 26 patients. Downward displacement of the orbital floor was observed in 15 patients. Other signs of sinus diseases were observed in 19 patients. Table 3 reports the radiological features.

Table 3. Radiological features

Radiographic comparison of unilateral and bilateral cases

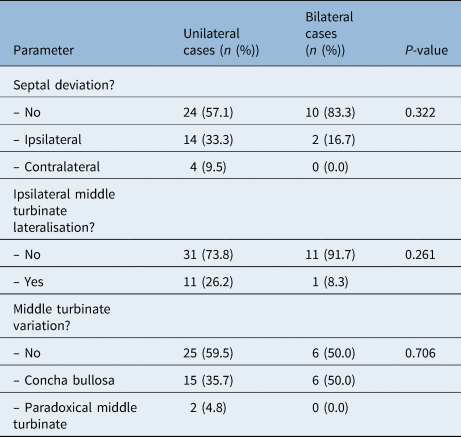

Fourteen ipsilateral nasal septal deviations were observed in unilateral cases and two in bilateral cases. There was no statistically significant difference between unilateral and bilateral cases for ipsilateral nasal septal deviation (p = 0.322).

Eleven ipsilateral middle turbinate lateralisations were observed in unilateral cases and one in bilateral cases. There was no statistically significant difference between unilateral and bilateral cases for ipsilateral middle turbinate lateralisation (p = 0.261).

In addition, there was no statistically significant difference between unilateral and bilateral cases in terms of middle turbinate variations (concha bullosa, paradoxical middle turbinate) (p = 0.706). Table 4 reports the radiographic comparison of unilateral and bilateral cases.

Table 4. Radiographic comparison of unilateral and bilateral cases

Discussion

Chronic maxillary atelectasis is known as a rare and underdiagnosed disease. The detection of chronic maxillary atelectasis in 54 of 5835 CT scans performed in our tertiary care hospital supports the fact that this disease is very rare. Chronic maxillary atelectasis has often been described as a unilateral condition.Reference Ho, Wong and Singh7 Although the majority of chronic maxillary atelectasis cases are unilateral, there are also bilateral chronic maxillary atelectasis cases reported in the literature. Kaas et al. reported 2 bilateral chronic maxillary atelectasis cases in their series of 22 patients.Reference Kass, Salman, Weber, Rubin and Montgomery3 In 2019, Ho et al. published a case series on bilateral chronic maxillary atelectasis with three patients, and conducted a literature review of bilateral chronic maxillary atelectasis cases in their research.Reference Ho, Wong, Gunaratne and Singh4 Our study comprised 12 bilateral cases; this corresponds to 22.2 per cent of all our cases. We think that the number of bilateral cases may be higher than previously expected, and the rate of bilaterality may increase as the number of diagnosed cases increases.

As previously shown in the literature, chronic maxillary atelectasis and silent sinus syndrome are two terms for the same clinical entity; hence, we think that these two terms should be combined to avoid diagnostic confusion.Reference de Dorlodot, Collet, Rombaux, Horoi, Hassid and Eloy1,Reference Brandt and Wright8 Therefore, silent sinus syndrome is not discussed separately from chronic maxillary atelectasis in our article. We propose a unified classification describing silent sinus syndrome as chronic maxillary atelectasis IIIS.

There are two main theories for the development of chronic maxillary atelectasis: obstruction of outflow and mechanical theory.Reference Cobb, Murthy, Cousin, El-Rasheed, Toma and Uddin9 Chronic hypoventilation of the maxillary sinus can have mechanical causes such as anatomical variation (septal deviation, concha bullosa of the middle turbinate, paradoxical middle turbinate), or inflammatory causes such as chronic rhinosinusitis.Reference Blackwell, Goldberg and Calcaterra10 It has been postulated that a deficiency in the posterior attachment of the uncinate process to the inferior turbinate, and a lateralised or hypermobile medial infundibular wall, could cause chronic hypoventilation of the sinus cavity via a valve effect.Reference Rose and Lund11,Reference Hobbs, Saunders and Potts12 Nevertheless, these anatomical variations explain only a few cases of chronic maxillary atelectasis. In our study, ipsilateral nasal septal deviations were observed in 33.3 per cent of the unilateral cases and 16.7 per cent of bilateral cases. In addition, ipsilateral middle turbinate lateralisation and middle turbinate variations were not observed in the majority of the patients. Other signs of sinus diseases were also absent in most cases. Further research on the aetiology of this entity is needed.

Regardless of its aetiology, blockage to mucus drainage causes chronic hypoventilation of the cavity. This results from the resorption of the mucosal gas and the development of negative pressure within the sinus cavity. Over time, these conditions lead to demineralisation and remodelling of the bone, with subsequent thinning and inward bowing of the maxillary walls.Reference Illner, Davidson, Harnsberger and Hoffman13–Reference Kass, Salman and Montgomery15 This negative pressure theory has been confirmed in animal studies.Reference Scharf, Lawson, Shapiro and Gannon16 In addition, Kass et al. measured negative pressures during the sinus surgery of chronic maxillary atelectasis patients.Reference Kass, Salman and Montgomery15

The number of patients with chronic sinusitis and ostial obstruction is higher than the number of patients with chronic maxillary atelectasis. Therefore, it is clear that further explanations are needed. The mechanical theory hypothesises that masticatory muscle contraction generates negative pressure in the infratemporal and pterygopalatine fossa, and the transmitted negative pressure can cause antral wall collapse.Reference Baujat, Derbez, Rossarie, Hardy, Wagner and Krastinova17

Currently, the accepted method for managing chronic maxillary atelectasis is uncinectomy and middle meatal antrostomy with an endoscopic approach. The primary argument for the treatment is the need for and optimal timing of orbital floor reconstruction.Reference Cardesín, Escamilla, Romera and Molina18 Some researchers prefer a one-stage surgery with endoscopic maxillary antrostomy and orbital floor reconstruction.Reference Rose and Lund11,Reference Bossolesi, Autelitano, Brusati and Castelnuovo19 However, most surgeons agree that the one-stage approach with orbital floor reconstruction is not needed in the majority of cases.Reference Thomas, Graham, Carter and Nerad20,Reference Facon, Eloy, Brasseur, Collet and Bertrand21 Most patients achieve spontaneous recovery of the enophthalmos and hypoglobus only by re-ventilation of the maxillary sinus.Reference Ando and Cruz22 In order to avoid unnecessary surgical interventions, surgeons frequently recommend a six-month delay between the two steps. We accept and use this two-step surgical approach in our clinic.

The main weaknesses of the present study include its retrospective design and the lack of endoscopic records for the patients. Another limitation is that CT was performed on patients who presented with sinus complaints; therefore, the prevalence might only be applied to that group, rather than a healthy population. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first radiological study of the prevalence of chronic maxillary atelectasis. In addition, our study reports on the largest numbers of unilateral and bilateral chronic maxillary atelectasis cases so far.

• Chronic maxillary atelectasis is an infrequent entity and data on its prevalence are lacking

• This study analysed 5835 patients with paranasal sinus computed tomography data to determine its prevalence

• The prevalence of chronic maxillary atelectasis in our study was 0.92 per cent; 22.2 per cent of cases were bilateral

• The prevalence of bilateral chronic maxillary atelectasis may be higher than previously reported, and bilaterality may increase with the number of diagnoses

• Chronic maxillary atelectasis and silent sinus syndrome describe the same clinical entity; these two terms should be combined to avoid diagnostic confusion

• A unified classification system is proposed, describing silent sinus syndrome as chronic maxillary atelectasis IIIS

To date, chronic maxillary atelectasis has been rarely reported in the literature and data on its prevalence are lacking. The prevalence of bilateral chronic maxillary atelectasis may be higher than previously reported, and the rate of bilaterality may increase as the number of diagnosed cases increases. Chronic maxillary atelectasis and silent sinus syndrome are two terms for the same clinical entity, and we therefore think that these two terms can be combined to avoid diagnostic confusion. We propose a unified classification describing silent sinus syndrome as chronic maxillary atelectasis IIIS. Further studies are needed to evaluate the aetiology, pathogenesis and prevalence of this entity.

Competing interests

None declared