Introduction

Infection by the new pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has highlighted a possible major role of chemosensory dysfunction, with a particular reference to smell disorders, often in association with taste disorders.Reference Hopkins and Kumar1,Reference Yan, Faraji, Prajapati, Boone and DeConde2

Focusing on smell impairment, it is known that post-viral anosmia could be a fairly common sequela of upper airway disease.Reference Seiden3 However, the clinical presentation of smell disorders during coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) does not seem to be ‘univocal’, ranging from patient reports of normal smell, to reports of partial loss of smell (hyposmia) or total loss of smell (anosmia), or even altered perception of smell (dysosmia).

Many research teams have evaluated olfactory dysfunction in patients affected by Covid-19, highlighting a possible role of the viral invasion of the olfactory bulb by SARS-CoV-2 as the main aetiopathogenic mechanism of olfactory dysfunction.Reference Butowt and Bilinska4 Bulfamante et al. recently described the autoptic presence of numerous particles, likely referable to virions of SARS-CoV-2, at the level of the olfactory nerve.Reference Bulfamante, Chiumello, Canevini, Priori, Mazzanti and Centanni5

However, it remains difficult to establish the exact prevalence of smell disorders, the expected timing of onset, the smell outcome, the associated risk factors, the relationship with taste disorders and, above all, the aetiopathogenetic mechanisms of damage.

A small number of systematic reviewsReference Tong, Wong, Zhu, Fastenberg and Tham6–Reference Soler, Patel, Turner and Holbrook12 have been published already, during the early stages of the pandemic in Europe and USA. However, in light of continuous scientific updating, we believe that our study can provide a more holistic approach to current knowledge of the disease. Furthermore, we believe that accurate identification of an olfactory disorder and its characteristics could facilitate our understanding of pathogenetic mechanisms, with particular reference to possible involvement of the central nervous system, thus ultimately enhancing our wider understanding of the role of smell dysfunction in Covid-19.

Materials and methods

This research was conducted using PubMed, Embase and Web of Science databases (Table 1), focusing on papers published up to 31th May 2020. The search was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) reporting guidelines,Reference Liberati, Altman, Tetzlaff, Mulrow, Gotzsche and Ioannidis13 as shown in Figure 1. Specifically, we performed a systematic electronic search of original articles published between March and May 2020, in English language, considering studies focused on olfactory evaluation in Covid-19 patients. Although there are many studies that consider smell dysfunction in patients affected by Covid-19, we chose to specifically consider only those which carried out an in-depth assessment focused on chemosensory disorders, particularly smell impairment, in Covid-19 patients.

Table 1. Summary of search strategies

Fig. 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) flowchart.

Inclusion criteria were: a laboratory confirmed diagnosis of Covid-19 infection; and the presence of a smell evaluation assessed through anamnestic and/or database data collection, a simple survey, a validated questionnaire focused on olfactory ability, and/or chemosensitive tests with odorants. We excluded from our investigation all systematic and narrative reviews, case reports, and all studies without specific data on patients affected by Covid-19. For a more precise analysis, we also excluded studies in which the patient's setting and/or smell evaluation method was not clearly explained.

The references of review articles were checked for cross-referencing purposes. The research process was conducted by two different authors (EF and AMS). Disagreements regarding the final selection of studies were discussed by the two authors and a final consensus was reached.

For each included article, we recorded: the number of Covid-19 patients, the number of patients with olfactory dysfunction, the country (and city if available) in which the study was performed, the type of study, patients’ data, the adopted method for smell evaluation (anamnestic data collection, simple survey, elaborated questionnaire focused on olfactory ability and/or chemosensitive tests with odorant), the time of evaluation, the time of disease onset, the concomitant evaluation of taste disorders, the patient setting (in-patient and/or out-patient) and evaluation results.

The selected studies were assessed for quality and methodological bias using the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Study Quality Assessment Tools.14 The level of evidence was assessed according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine level of evidence guide.15

Patients, intervention, comparison and outcomes criteria

The patients, intervention, comparison and outcomes (‘PICO’) criteria for the review were considered as follows: (1) patients – patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection certified on laboratory tests who underwent a clinical evaluation of smell impairment using anamnestic data, a smell questionnaire and/or olfactory tests; (2) intervention – clinical evaluation of olfactory disorders; (3) comparison – different methods of evaluating olfactory function (subjective and objective); and (4) outcome – prevalence and characteristics of olfactory dysfunction in Covid-19 patients.

Results

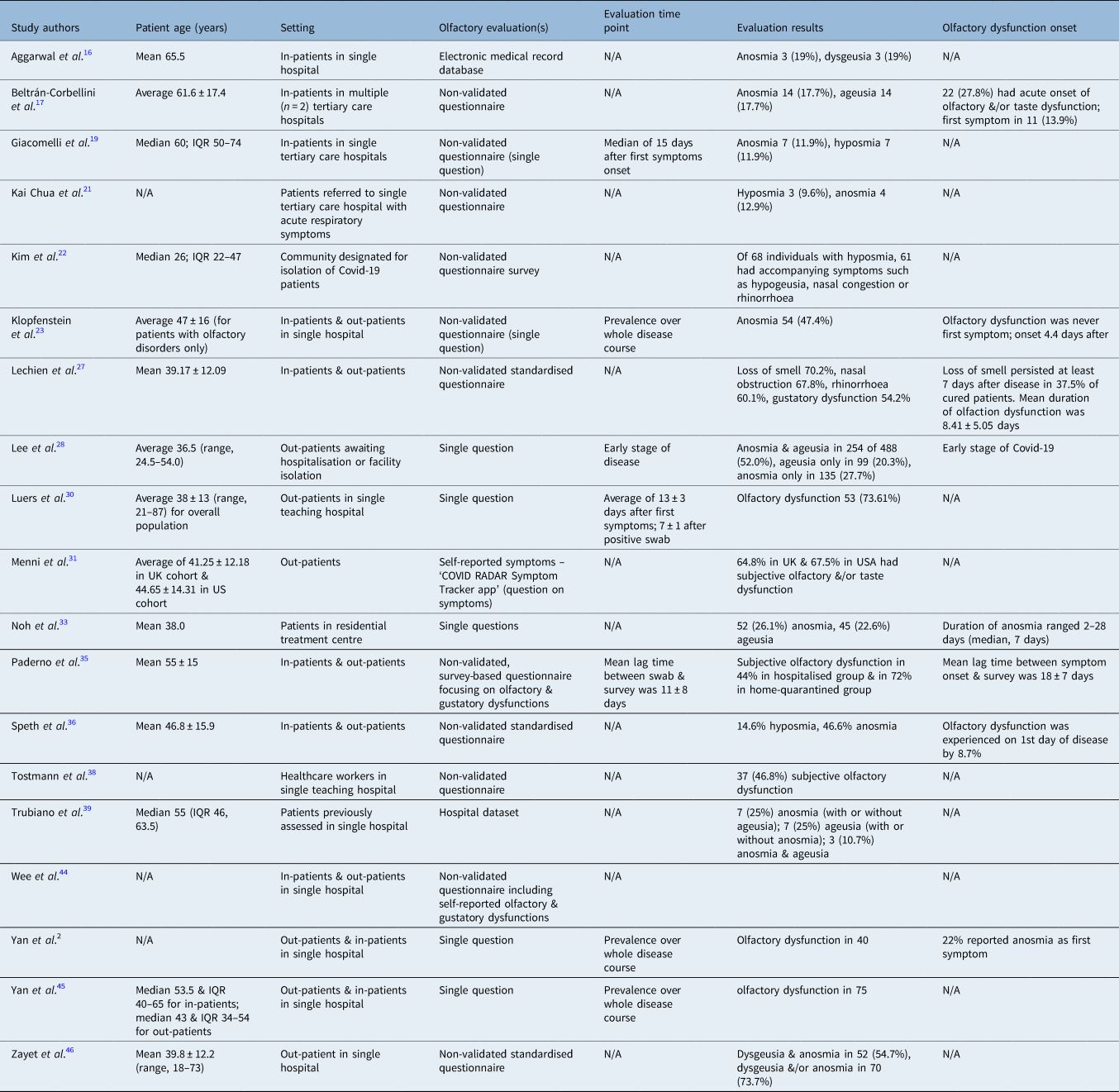

Of the 483 research papers initially identified, 32 original studies were finally selected, comprising a total of 17 306 subjects with a laboratory confirmed diagnosis of Covid-19. Individual study sample sizes ranged from 6 to 6452 patients. The studies’ characteristics are described in Table 2.Reference Yan, Faraji, Prajapati, Boone and DeConde2,Reference Aggarwal, Garcia-Telles, Aggarwal, Lavie, Lippi and Henry16–Reference Zayet, Klopfenstein, Mercier, Kadiane-Oussou, Lan Cheong Wah and Royer46 Over half of the selected studies were carried out in European countries.

Table 2. Summary of included studies

Covid-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; NHI-SQAT = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Study Quality Assessment Tools

Olfactory ability was assessed by: using validated questionnaires focused on smell dysfunction, in three studies; obtaining objective information on smell impairment through standardised chemosensitive tests with odorants, in five studies; and considering both methods, in five studies (Table 3).Reference Carignan, Valiquette, Grenier, Musonera, Nkengurutse and Marcil-Héguy18,Reference Hornuss, Lange, Schröter, Rieg, Kern and Wagner20,Reference Lechien, Chiesa-Estomba, De Siati, Horoi, Le Bon and Rodriguez24–Reference Lechien, Cabaraux, Chiesa-Estomba, Khalife, Hans and Calvo-Henriquez26,Reference Li, Long, Zhu, Wang, Wang and Lin29,Reference Moein, Hashemian, Mansourafshar, Khorram-Tousi, Tabarsi and Doty32,Reference Ottaviano, Carecchio, Scarpa and Marchese-Ragona34,Reference Spinato, Fabbris, Polesel, Cazzador, Borsetto and Hopkins37,Reference Tsivgoulis, Fragkou, Delides, Karofylakis, Dimopoulou and Sfikakis40–Reference Vaira, Salzano, Petrocelli, Deiana, Salzano and De Riu43,Reference Zou, Linden, Cuevas, Metasch, Welge-Lüssen and Hähner47–Reference Veyseller, Ozucer, Karaaltin, Yildirim, Degirmenci and Aksoy59 The remaining studies assessed olfactory ability through anamnestic data collection, simple surveys and/or structured, non-validated questionnaires (Table 4).Reference Yan, Faraji, Prajapati, Boone and DeConde2,Reference Aggarwal, Garcia-Telles, Aggarwal, Lavie, Lippi and Henry16,Reference Beltrán-Corbellini, Chico-García, Martínez-Poles, Rodríguez-Jorge and Alonso-Cánovas17,Reference Giacomelli, Pezzati, Conti, Bernacchia, Siano and Oreni19,Reference Chua AJ, Chan EC, Loh and Charn21–Reference Klopfenstein, Kadiane-Oussou, Toko, Royer, Lepiller and Gendrin23,Reference Lechien, Chiesa-Estomba, Place, Laethem, Cabaraux and Mat27,Reference Lee, Min, Lee and Kim28,Reference Luers, Rokohl, Loreck, Wawer Matos, Augustin and Dewald30,Reference Menni, Valdes, Freidin, Sudre, Nguyen and Drew31,Reference Noh, Yoon, Seong, Choi, Sohn and Cheong33,Reference Paderno, Schreiber, Grammatica, Raffetti, Tomasoni and Gualtieri35,Reference Speth, Singer-Cornelius, Obere, Gengler, Brockmeier and Sedaghat36,Reference Tostmann, Bradley, Bousema, Yiek, Holwerda and Bleeker-Rovers38,Reference Trubiano, Vogrin, Kwong and Homes39,Reference Wee, Chan, Teo, Cherng, Thien and Wong44–Reference Zayet, Klopfenstein, Mercier, Kadiane-Oussou, Lan Cheong Wah and Royer46

Table 3. Summary of smell-related outcomes assessed via validated questionnaires and/or objective tests

IQR = interquartile range; Covid-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; N/A = not applicable; ICU = intensive care unit; sQOD-NS = short version of the Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorders – Negative Statements (a seven-item patient-reported outcome questionnaire including social, eating, annoyance and anxiety questions; NAHNES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; SD = standard deviation; UPSIT = University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test; PROM = patient-reported outcome measures; SNOT-22 = Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22; VAS = visual analogue scale; ARTIQ = Acute Respiratory Tract Infection Questionnaire; Q-SIT = Quick Smell Identification Test; CCCRC = Connecticut Chemosensory Clinical Research Center

Table 4. Summary of smell-related outcomes assessed via anamnestic data collection, simple surveys and/or non-validated questionnaires

N/A = not applicable; IQR = interquartile range; Covid-19 = coronavirus disease 2019

Discussion

Our review confirmed that olfactory disorders represent an important clinical feature in individuals affected by Covid-19, with a prevalence ranging from 11 per cent to 100 per cent of included patients, although there was heterogeneity in terms of assessment tools and population selection criteria.

The reported data show that smell dysfunction was, overall, more prevalent in patients investigated with validated questionnaires and/or tests with odorants (Table 3), compared to individuals evaluated using anamnestic data, simple surveys and/or non-validated questionnaires. This is in agreement with the findings of Moein et al.Reference Moein, Hashemian, Mansourafshar, Khorram-Tousi, Tabarsi and Doty32 and further studies,Reference Soter, Kim, Jackman, Tourbier, Kaul and Doty60 which indicate that self-reported evaluations of olfactory loss are not in line with the more reliable outcomes of standardised tests. There are exceptions to this general trend, however, as highlighted by the papers of Lechien et al.Reference Lechien, Cabaraux, Chiesa-Estomba, Khalife, Hans and Calvo-Henriquez26 and Li et al.,Reference Li, Long, Zhu, Wang, Wang and Lin29 but in these latter manuscripts there are some possible biases that may affect the data.

The variations in reported outcomes may be a result of the different methods of evaluation; however, the variations might also be because of other important factors. Primarily, non-validated tests are only focused on smell disorders of new onset and do not investigate the presence of olfactory dysfunction prior to Covid-19. In contrast, a validated questionnaire and/or objective olfactory test allows greater accuracy regarding the real prevalence of olfactory disorders, the exact timing of onset and their characteristics.

Furthermore, our analysis does not suggest any significant differences in terms of the age or gender of the enrolled subjects, although younger patients often seem to show a greater prevalence of smell disorders than older ones. These data seem difficult to understand until we consider that the elderly population has a higher prevalence of smell disorders overall. In the context of Covid-19, younger patients are more likely to have a new onset of olfactory dysfunction (more evident with a non-validated questionnaire analysis), and frequently have less severe respiratory symptoms, resulting in more susceptibility to olfactory problems. Therefore, we believe that age should be considered as a possible bias, at least regarding the elderly population, given that the estimated prevalence of smell impairment in the general population aged above 80 years ranges between 43.1 per cent and 84.9 per cent.Reference Doty61

Regarding the hospital setting, our review highlighted a lower prevalence of smell disorders in hospitalised patients compared with home-quarantined patients. Two studies focused specifically on this comparison,Reference Yan, Faraji, Prajapati, Boone and DeConde2,Reference Paderno, Schreiber, Grammatica, Raffetti, Tomasoni and Gualtieri35 emphasising a greater prevalence of the disorder in individuals with low-to-mild disease compared to those who needed hospital treatment. Once again, this difference could be related to greater attention devoted to olfactory impairment in patients in an overall better health condition.

Another relevant source of heterogeneity is linked to the different timings of smell evaluation with respect to the onset of symptoms. According to our data, smell dysfunction seems to occur mostly in early stages of the disease, and tends to decrease or resolve within the two weeks following virologic healing in the majority of the patients; therefore, all evaluations that take place during an advanced or unspecified disease stage could underestimate olfactory dysfunction.

Finally, we should consider that the large prevalence of smell disorders apparently became evident only when the SARS-CoV-2 infection hit Europe. In the first studies performed in China and Singapore, patients were frequently unaware of olfactory dysfunction.Reference Guan, Ni and Hu62–Reference Pung, Chiew, Young, Chin, Chen and Clapham64 It is striking that more than half of the reviewed studies were carried out in European countries. This could be related to a higher prevalence of Covid-19 associated smell disorders in Caucasian people, although other factors should be taken into account. A possible bias could be presented by the fact that some scientific reports are written in original Chinese language and are difficult to access. In addition, we should bear in mind that – with the exception of China – the scholarly production on Covid-19 and olfactory dysfunction follows the outbreak spread, which is already peaking in Europe and Western Asia, has flourished in North America and is in an earlier stage in South America.

While these data confirm what has already been included in earlier reviews, our paper is able to present a somewhat later analysis of the issue of smell impairment in Covid-19. It discusses more complete and well-defined data than other previously published papers, and includes a significantly greater number of patients.

Nevertheless, many problems need to be addressed to allow a holistic evaluation of smell impairments in Covid-19 patients. In order to allow further and stronger meta-analytic papers, smell assessment tools should converge into validated questionnaires and odorant tests. In addition, important reported biases (e.g. age, hospital setting and patients’ overall condition) should be appropriately addressed in the context of well-designed future prospective studies.

Conclusion

In the wake of the relevance of olfactory dysfunction in individuals with Covid-19, we believe that olfactory assessment is essential in every patient with a new diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the early stage. Furthermore, we think that smell disorders of new onset should be considered a possible symptom for suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our study suggests the need for a clinical standardised evaluation carried out using structured questionnaires and, if possible, tests with olfactory substances. Finally, ENT assessment in Covid-19 patients should be routinely proposed to ensure the correct evaluation of chemosensitive disorders and the possible need for therapeutic strategies.

Competing interests

None declared