Introduction

In Germany, for about 4.1 million workers (roughly 10 per cent of the total workforce) so-called mini-jobs represent their main job. Another 3.0 million workers hold a mini-job as a secondary job, alongside a main job. In the European context, mini-jobs are a rather unique form of non-standard employment as monthly earnings are restricted up to a certain level (450 Euros) exempting employees – but not employers – from taxes and social insurance contributions. A similar regulation to that in Germany exists only in Austria.Footnote 1

Mini-jobs have given cause to very different – even contradictory – interpretations in comparative cross-country research. In the sub-field of comparative political economy, mini-jobs are seen as a strategy to extend labour market dualisation (eg. Palier & Thelen, Reference Palier and Thelen2010). For other scholars, mini-jobs are a particular precarious form of employment causing an increase in the risk of poverty for millions of people (Arrizabalo, Pinto, & Vincent, Reference Arrizabalo, Pinto and Vincent2019). In turn, in the comparative social policy literature, mini-jobs are linked to anti-poverty policies. Scholars such as Kenworthy (Reference Kenworthy2015), Galassi (Reference Galassi2017) and Laun (Reference Laun2019) frame mini-jobs as a kind of “in-work benefit” aiming to “make work pay.”

Mini-jobs, however, have existed in the form of marginal part-time employment long before the “age of dualisation” (Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Hausermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012). They are rooted in a conservative welfare state with a traditional division of labour within couple household. Mini-jobs are until today closely related to tax and insurance arrangements protecting married women against the loss of the breadwinner through derived and supplementary rights to social security (Lewis, Reference Lewis1992). The different strands of comparative research have, however, widely ignored this fact and “overlooked” the critical role of mini-jobs for gender equality.

By putting mini-jobs in its historical and institutional context and by reviewing a variety of data sources, statistics and empirical studies, this paper aims to provide a comprehensive and contextualised analysis of this particular employment scheme contesting its framing in different sub-fields of comparative research on work and welfare. While doing so it addresses a general challenge in cross-country comparisons, namely that without a thorough understanding of the broader context of the respective national employment and social system, the conceptualization of seemingly similar patterns of employment and social policies might lead to misinterpretations and erroneous conclusions in terms of policy learning and institutional change.

The paper is organised as follows: The next section analyses the rationale behind policies regulating mini-jobs and describes the drivers of its evolution over time. Section “The demographic and income profile of mini-jobbers” analyses the demographic and income profile of mini jobbers. Section “Mini-jobs in different strands of comparative research” discusses critically the analytical narratives of mini-jobs developed in different strands of comparative research and draws attention to a major gap, namely the disregard of the gender specific risk associated with mini-jobs. By summarising the main findings of this review essay Section “Discussion and Outlook” addresses the political future of mini-jobs.

The political rationale for mini-jobs and the drivers of its evolution over time

Mini-jobs are rooted in a conservative welfare state with a traditional division of labour within couple household. They are closely related to the German social security system. Already at the end of the 19th century, exemptions from compulsory insurance of occasional employment relationships have been introduced for administrative reasons to avoid small pension claims.Footnote 2 Against the background of acute labour shortages in several industries in the mid-1960s, tax and contribution-free marginal employment was made more attractive in order to encourage housewives to take up at least a small part-time job. An earnings threshold was determined and annually adjusted as a function of the income threshold for the assessment of social security contributions (Rudolph, Reference Rudolph1999).

In the conservative German welfare state (Lewis, Reference Lewis1992) married women have a special status under social security law as they have access to derived rights from the public health and pension insurance. Marginal part-time employment (calling it mini-jobs since 2003) provides tax and social insurance privileges for employees. These privileges are at the core of the scheme and married women – still accounting for about 60 per cent of all mini-jobbers – are the group who use mini-jobs most to earn an additional income. This dominant feature of the long-standing scheme has been widely maintained also after its last major reform in the context of the so-called “Hartz reforms” in 2003.

The special status of married women under social law in combination with processes of social change such as increasing female employment gradually increased the importance of this particular form of atypical employment. Nonetheless, since the mid-1990s, the special status under social law was increasingly criticised politically (Dingeldey, Reference Dingeldey and Schafer2000). A substantial reform in 1999 aimed to limit the avoidance of social security contributions and to reduce the high popularity of marginal employment by increasing employment subject to social insurance. To this end, the privileged status for marginally employed second jobholders (geringfügige Beschäftigung als Nebentätigkeit) was abolished (Arntz, Feil, & Spermann, Reference Arntz, Feil and Spermann2003). Second jobs were now fully subject to taxation and social security contributions.

However, the political goal turned by 180° in the early 2000s. Triggered by the idea to use the marginal part-time employment scheme to tackle high structural unemployment among low-skilled workers in line with the “transitional labour market (TLM) approach,”Footnote 3 the Hartz-Commission – initiated by the Red-Green government – promoted the idea of marginal employment as a low-threshold possibility to enter into the labour market by providing a stepping stone into standard employment (Bundesregierung, 2003). Hence, an expansion of marginal employment was seen as an effective instrument for reducing unemployment. In addition to the income threshold for mini-jobs, a phase-out region was introduced creating so-called midi-jobs, for gross monthly earnings between 400 and 800 EUR as a way to avoid the “325 Euros trap.”

Motivated by the expansion of mini-jobs following the 2003 reform and aiming to curb the alleged substitution of regular jobs by publicly subsidised mini-jobs, the employers’ social security contribution rate increased in 2006 from 25 per cent of gross monthly earnings of 400 EUR to 30 per cent. To adjust to the general wage growth, the legislator raised the earnings threshold in 2013 to 450 EUR. Since then, the threshold has not changed anymore and mini-jobbers have become obliged to contribute to the public pension system if they do not use the opting out rule. However, 80 per cent are using this rule (Minijob-Zentrale, 2015). Although employers still have to pay contributions to the pension system, workers cannot derive their own pension rights. This is inconsistent with the insurance principle but politically justified to avoid a distortive effect in competition.

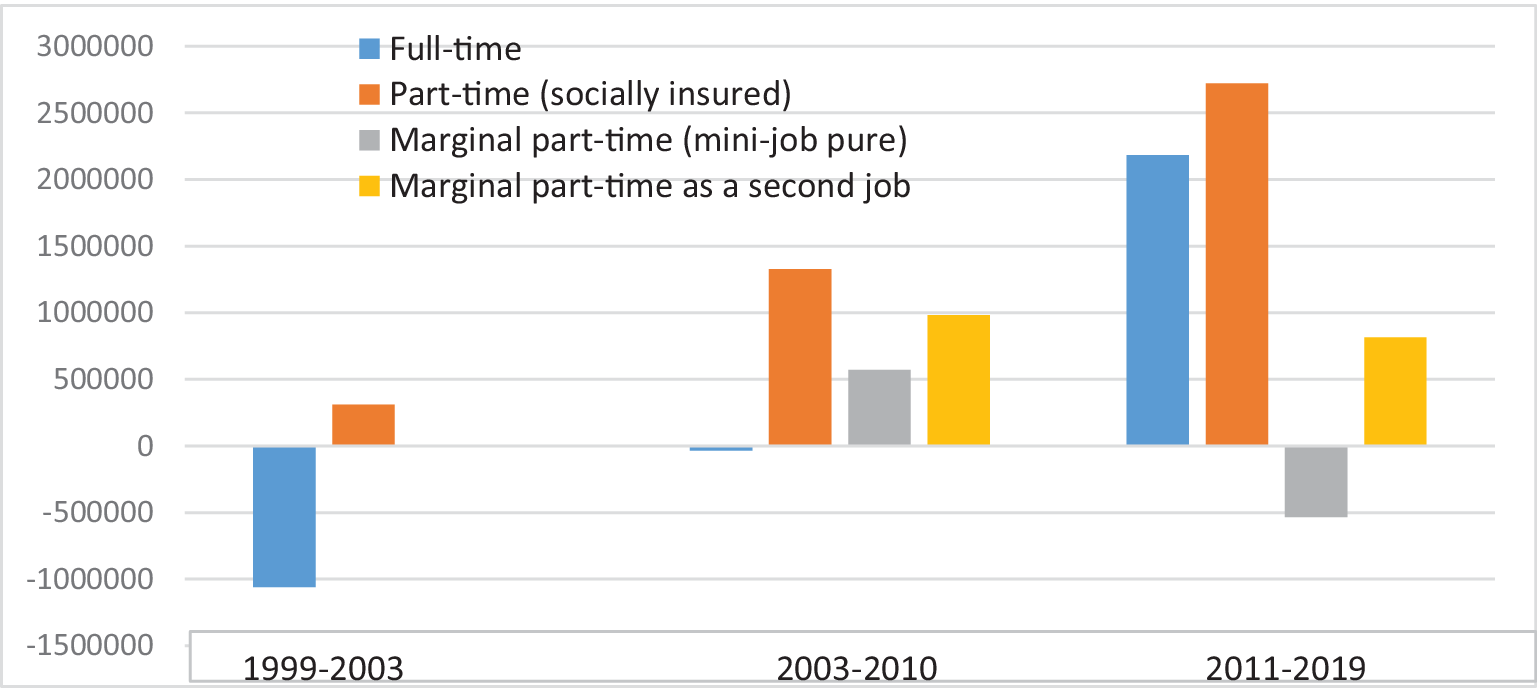

Until 1999, the statistics provided only incomplete information on the evolution of marginal part-time employment. Different data sources recorded, however, concordantly an increase in marginal part-time employed by 1.0 to 1.9 million throughout the 1990s (Rudolph, Reference Rudolph2003).The changes in the legal regulation by the mini-job reform in 2003 might be one but not the only reason behind the increase of about 1 million mini-jobs pure between 2002 and 2004 (Figure 1). Another reason is the legalisation of mini-jobs from the shadow economy. To combat undeclared work, activities in private households were made subject to lowered social security contributions compared to activities in the commercial sector (Berthold & Coban, Reference Berthold and Coban2013). Moreover, administrative procedures for mini-jobs were simplified and made more transparent.Footnote 4

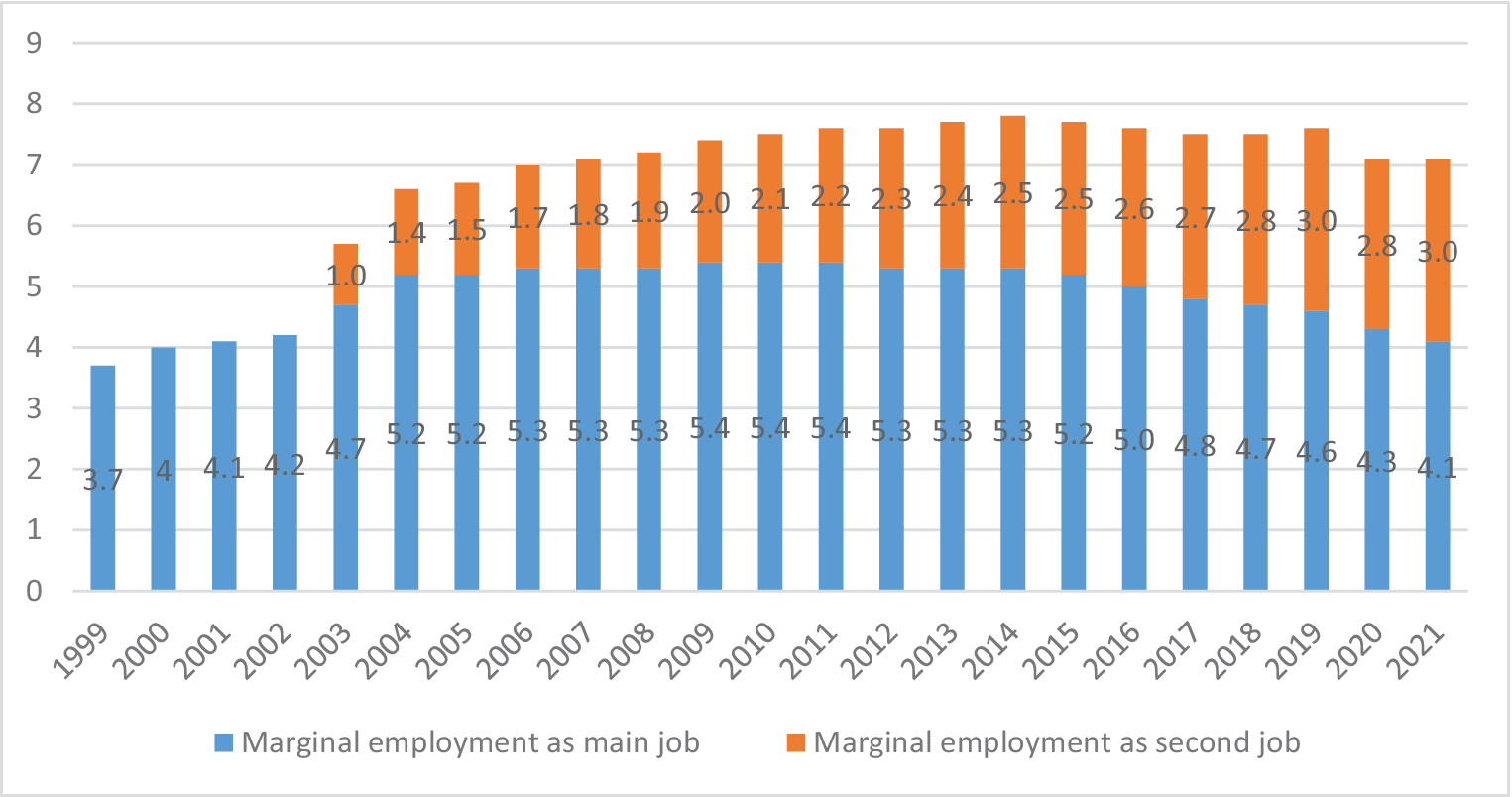

Figure 1. Development of mini-jobs as main and as second job from 1999 to 2021. Source: BA-Statistics, reference data is 30 June of each year.

Thereafter, the number of mini-jobs pure remained widely stable until 2015. Since the introduction of the statutory minimum wage in 2015, the number of mini-jobs pure has been constantly decreasing as the scope for mini-jobs has been limited. With the given monthly wage threshold of 450 EUR working hours cannot be varied at will. Every rise in the hourly minimum wage leads to a reduction of working hours for people with such jobs. Companies have adapted to the new circumstances by partly converting mini-jobs into regular (socially insured) part-time jobs (Vom Berge & Weber, Reference Vom Berge and Weber2017). The declining trend was sustained until the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and has been reinforced since then. In June 2021, the BA statistics recorded about 306,000 less mini-jobbers pure compared to the start of the pandemic (BA Statistics, 2021).

The main driver of the rise in the total number of mini-jobs since 2005 are mini-jobs hold as a secondary job on top of a socially fully insured part-time or full-time job. The number of such side jobs (Nebenjobs) increased from 1 million in 2003 to 3 million in 2019, decreased then for the first time in 2020 to 2.8 million as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic but has risen again to 3.0 million by June 2021 (Figure 1).

The reasons for the increase in mini-jobs hold as secondary job are clearly institutional ones. Since the mini-job reform in 2003, second jobholders enjoy again the privilege of being exempted from taxes and social security contributions. The take-up of a second job is subsidised independently of the wage level earned in the main job. The aggregate working hours’ accounts of the Institute for Employment (IAB-Arbeitszeitrechnung) show that almost 90 per cent of second jobholders are combining a standard full-time or part-time job with a mini-job. In contrast, the combination of two mini-jobs is rather seldom as earning more than 450 EUR by adding up several mini-jobs are no longer exempted from taxes and social security contributions. Due to this unique “tax privilege” for second jobholders in Europe, the number of small side jobs tripled. Klinger & Weber (Reference Klinger and Weber2020) demonstrate empirically that it is the far-reaching tax privilege of these jobs setting wrong incentives for multiple job holding.

Beyond re-establishing rules regarding the eligibility of mini-jobs for second jobholders, the 2003 reform (Hartz II) – calling it now mini-jobs – lifted the restriction to work only up to 15 hours weekly in line with the official definition of registered unemployment.Footnote 5 Furthermore, the reform increased the earnings threshold from 325 to 400 Euros while maintaining the characteristic features (employees’ exemption from tax and social security contributions) of the scheme. Hence, deregulation was less far-reaching than predominantly assumed in the comparative political economy literature (see Section “Mini-jobs in different strands of comparative research” for a more thorough discussion).

Figure 2 shows that the reform in 2003 is not the cause of the strong employment growth in Germany since the mid-2000s, either. Hence, the “Germany’s labour market miracle” was not driven by “precarious” mini-jobs as suggested by comparative scholars such as Arrizabalo, Pinto, & Vincent (Reference Arrizabalo, Pinto and Vincent2019) but by an unprecedented expansion of regular (socially insured) part-time employment. Between December 2004 and September 2019, socially insured full-and part-time employment increased much more (+27 per cent) than mini-jobs (+1.5 per cent).

Figure 2. Employment trends in Germany 1999–2019, in millions. Source: BA statistics, own calculations.

The demographic and income profile of mini-jobbers

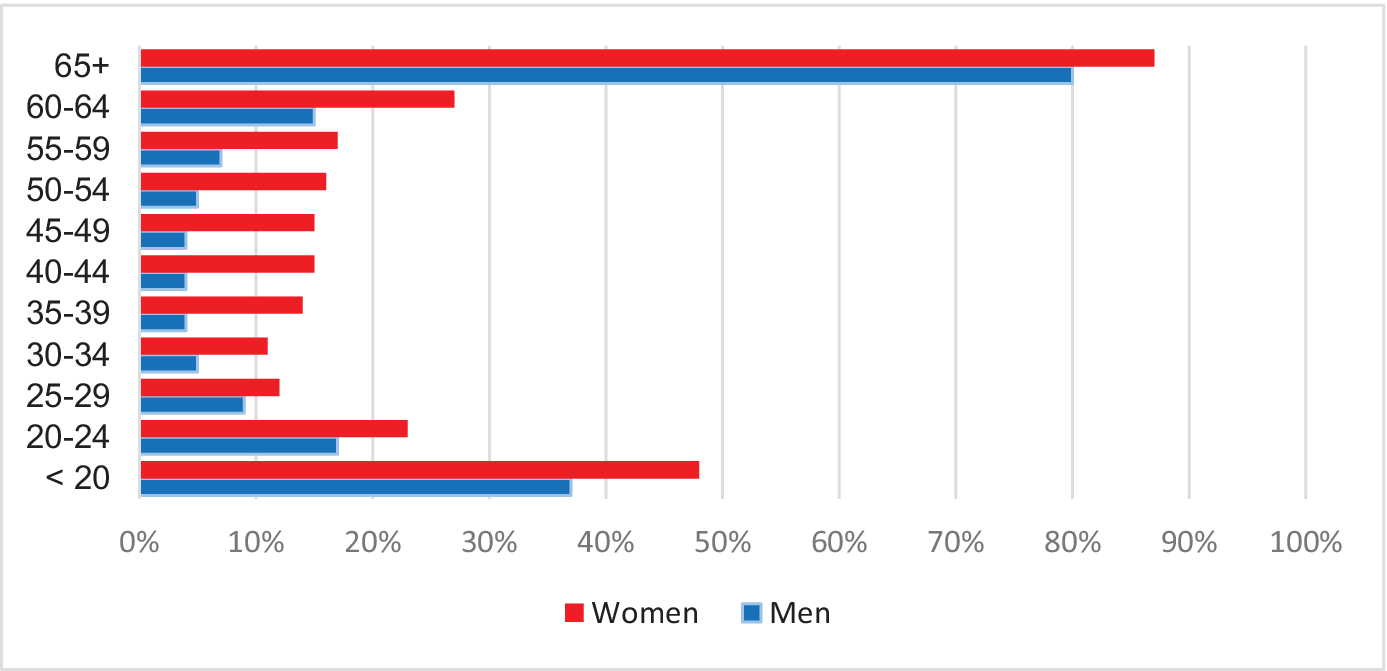

About 60 per cent of all mini-jobbers are women and about two-thirds of them live in a household with a full-time working partner (Wanger, Reference Wanger2015). The coverage of spouses in the health insurance of the main earner and widow’s pension, as well as the splitting model in the joint income taxation scheme of married couples (Ehegattensplitting – introduced in 1958), provides high incentives for women to work only a few hours and low incentives to extend working hours up to full-time. For married couples with a main earner who can take advantage of tax benefits such as spouse splitting mini-jobs are tax-efficient. This is underpinned by the distribution of mini-jobbers across age groups and income levels (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Marginally employed by age group and gender, in per cent of all employed, 2014. Source: IAB-Arbeitszeitrechnung (Aggregate hours’ accounts; own calculations based on Wanger, Reference Wanger2015).

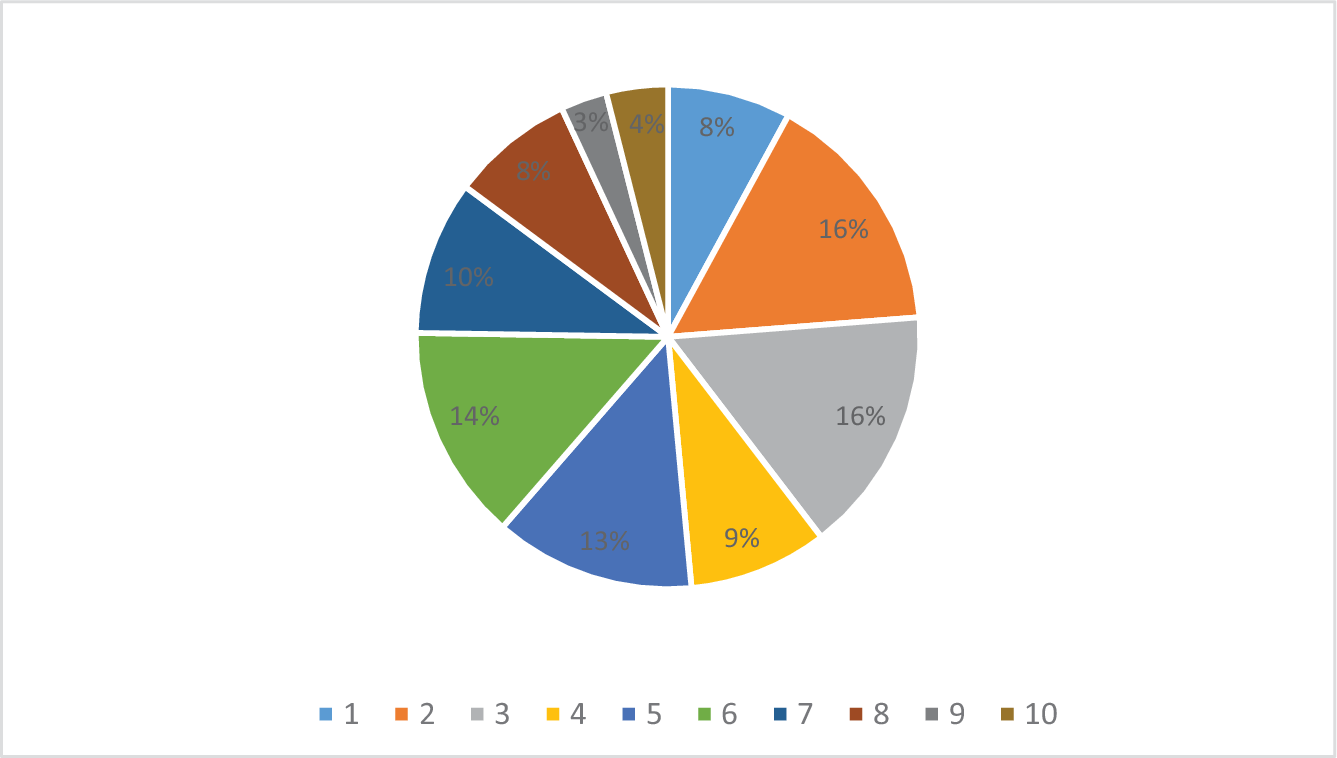

Figure 4. Distribution of mini-jobbers over equivalised net household deciles. Source: IAB Panel Labour Market and Social Security (PASS), Wave 9 (Bruckmeier et al., Reference Bruckmeier, Lietzmann, Mühlhan and Stegmaier2018).

Figure 3 shows that women take up marginal part-time work in all age groups. In contrast, men decide especially at the beginning (students, pupils) and at the end (pensioners) of working life to engage in marginal part-time work as their main job (Figure 3). To better reconcile family and working many mothers are re-entering the labour market after career breaks by taking up a mini-job. Hence, women with children under the age of 14 are more likely to have a mini-job than those without children.

Surveys show that the motives to take up a mini-job are multidimensional (Körner, Meinken, & Puch, Reference Körner, Meinken and Puch2013). The lack of better work alternatives, however, seems to be of secondary importance (Beckmann, Reference Beckmann2020). Nonetheless, mini-jobs have also become part of the working biography of vulnerable groups. Among them are low educated women without children whose career paths are characterised by breaks in life and working biographies. Another sub-group is sick people for which marginal part-time employment might constitute a possibility to stay in touch with the labour market. More recently, mini-jobs seem to help newly arrived refugees to get a foothold in the German labour market.Footnote 6

The many motives behind mini-jobs are also reflected in the distribution of mini-jobbers among income deciles. Figure 4 shows that mini-jobbers are present in all deciles of the income distribution. However, the often alleged high poverty risk of mini-jobbers is not reflected in household data. Figure 4 rather suggests that there is cross-subsidising of employment and wealthier households: 15 per cent of the mini-jobbers are found in the upper-income bracket, 46 per cent in the middle-income bracket and 40 per cent at the lower end.

Mini-jobs in different strands of comparative research

Mini-jobs as main driver of dualisation and precarity

In the comparative political economy literature, mini-jobs are associated with the dualisation of the labour market. The concept of dualisation is related to the long-standing analysis of insiders and outsiders. Politics that de-regulate labour markets and social protection increase the divide between labour market insiders and outsiders leading to dualisation on the labour market. For Palier & Thelen (Reference Palier and Thelen2010), Thelen (Reference Thelen2014) and Hassel (Reference Hassel2014) mini-jobs and particularly the mini-job reform in 2003, have contributed to the deepening of dualisation trends in the German labour market. According to Thelen (Reference Thelen2014), pp. 134–141), mini-jobs are one of the most important sources of dualisation in Germany. She argues that the increase of marginal part-time employment has to be seen in the context of firms’ attempts to increase or maintain job security for core workers. Following this argument, employers began in the 1980s to use mini-jobs as a cheaper alternative to regular part-time employment in the low-skill service sectors. Governments, employers and unions jointly preferred the deregulation of the peripheral labour market to the deregulation and liberalisation of employment protection for the core workforce.

While mini-jobs might indeed fit into the analytical narrative of dualisation it might be questioned if there is an explicit dualisation strategy behind it as assumed by political economy scholars. Thelen (Reference Thelen2014, p. 134–141) makes a strong claim by analysing mini-jobs as the main source of flexibilising the periphery. She argues that behind these policies are coalitions between employers and trade unions in manufacturing, which agree on “a less regulated periphery” in the service sector. The argument that marginal part-time employment is used as a solution for the non-wage cost problem in the peripheral service sector – also brought forward by Eichhorst and Marx (Reference Eichhorst, Marx and Emmenegger2010, p. 15) –seems, however, “overstretched” especially as employers pay a higher percentage of social security contributions for mini-jobbers than for standard workers.

From the employers’ perspective, the attractiveness of mini-jobs is indeed less obvious than it may seem at first glance. In most surveys, employers mention flexibility as main motive for the deployment of mini-jobs on the company side. While larger firms use more frequently fixed-term employment contracts or temporary agency work to increase flexibility, mini-jobs seem to fulfil an important flexibility function particularly in small enterprises (Hohendanner & Stegmaier, Reference Hohendanner and Stegmaier2012). The smaller the company, the more likely it is that mini-jobbers are employed (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Gundert, Kawalec, Sowa, Tesching and Theuer2015). Lower non-wage costs do not play a major role, at least at first sight. Employers have to pay a flat-rate contribution of about 30 per cent on top of the monthly wages for mini-jobbers, which is about 50 per cent higher compared to workers in regular, socially insured employment. This flat-rate contribution, however, does not give mini-jobbers any entitlement to social insurance benefits. It is intended primarily to ensure that companies do not substitute regular employed workers by mini-jobbers because of their lower non-wage labour costs (Weinkopf, Reference Weinkopf2014).

Nonetheless, at second sight lower wage costs might play a role to hire mini-jobbers. Mini-jobbers might make concessions on gross wages due to their better net position. This is most probably a consequence of the fact that mini-jobs are subsidised via the exemption of employees from social security contributions and taxes. Hence, employers could shift higher social security contributions for mini-jobbers to their workers by paying lower hourly wages.

Overall, the dualisation argument strongly put forward in the comparative economy literature and focusing one-sidedly on the demand side has to be balanced by supply-sided motives. Often ignored (or not known) in the comparative literature is the fact that the vast majority (84 per cent) of mini-jobbers is still mainly composed of four groups: homemakers (42 per cent), pupils and students (22 per cent) and retirees (20 per cent). Another 10 per cent are unemployed toping up their (means-tested) unemployment benefits with a mini-job (or vice versa). These groups see their mini-job primarily as a small additional income earned in a non-bureaucratic and tax-free way and not as their main income source (RWI, 2016; Körner, Meinken, & Puch, Reference Körner, Meinken and Puch2013). The fact that earnings are paid “gross per net” makes the scheme very attractive not only for married women but also for students, retirees, or unemployed who already have another type of social security coverage.

For comparative scholars, focusing on the outcomes of dualisation policies, mini-jobs are a prime example of “precarious work.” Brady & Biegert (Reference Brady, Biegert, Kalleberg and Vallas2018) – applying the analytical framework of “precarious work” developed by Kalleberg (Reference Kalleberg2009) – associate mini-jobs with limited economic rewards and a lack of legal and social protection implying that employees bear the risks of benefits and statutory protections with negative effects on workers’ well-being. While marginal part-time jobs meet the criteria of peripheral jobs in many respects, ie. lower wages or few working hours they might be less precarious than often described. Mini-jobbers do not lack any social protection. The vast majority of mini-jobbers are de facto covered in case of illness. As already mentioned, mini-jobbers in couple-households are covered by derived rights. They have the right to health co-insurance and they are also protected in case of old age through derived survivors’ pensions. Pupils and students usually are covered by family insurance or have a student health insurance and retirees are covered by the obligatory health insurance of pensioners. Mini-jobbers can gain their own pension entitlements if they do not use the opting-out rule. However, 80 per cent are using this rule (Minijob-Zentrale, 2015). Mini-jobbers are, however, not eligible, neither for unemployment benefits nor for the insurance-based short-time work allowance since neither employers nor employees contribute to unemployment insurance. In cases of unemployment, marginally employed persons are only entitled to the means-tested Arbeitslosengeld II (ALG II) benefits.

Questionable is also the alleged lack of protection under labour law. Mini-jobbers enjoy de jure the same rights under labour law as standard workers. The German labour law ensures equal treatment between standard and non-standard forms of employment. This means that mini-jobbers have a right to holiday pay, sick leave, a right to continued pay in the event of illness, a right to participate in works council elections, the right to receive the minimum wage and, above all, a right to comply with the rules on protection against dismissal. However, several surveys show that non-compliance with labour and collective law standards is frequent (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Gundert, Kawalec, Sowa, Tesching and Theuer2015; RWI 2016). One in three marginal part-time workers is not granted benefits such as paid leave, continued pay in the event of illness and further vocational training in the company (Bachmann et al., Reference Bachmann, Dürig, Frings, Höckel and Martinez Flores2017). Non-compliance with labour standards is also attributed to the fact that mini-jobs are concentrated in service industries where workers are less protected by collective bargaining agreements (Beckmann, Reference Beckmann2020).

Surveys also indicate that mini-jobbers are often unaware of their rights. Poor information of many mini-jobbers about their rights leads to a poor de facto coverage by labour law. Gundert and Stegmaier (Reference Gundert and Stegmaier2019) attribute the lower interest in the enforcement of their rights to the fact that the work orientation of mini-jobbers is presumably weak as they consider their mini-job as additional and not as main income. Furthermore, there are reasons to believe that mini-jobbers overestimate the advantage of being employed as mini-jobber (Beckmann, Reference Beckmann2020).

Comparative political economy scholars are right in that mini-jobbers face a high low-wage risk. Mini-jobs are more widespread among jobs requiring a low level of skills and in service sectors with low wage levels such as retail trade, hotels and restaurants or household services. Until 2015 and in the absence of a statutory hourly minimum wage, half of the mini-jobbers earned less than 8.50 EUR per hour. After the introduction of the statutory minimum wage, the average hourly wage grew by 13 per cent. However, in 2018 the hourly wage of almost 82 per cent of the mini-jobbers was still below the low-wage threshold of two-thirds of the median income. Mini-jobbers, thus, account for about one-third of the German low-wage sector (Kalina & Weinkopf, Reference Kalina and Weinkopf2020).

To sum up: Unlike the strong claim in comparative political economy research that mini-jobs are one of the main drivers of precarity on the German labour market, mini-jobs might be less precarious than usually assumed.

Mini-jobs as anti-poverty policy

A very different view on mini-jobs can be found in the sub-field of comparative social policy research. There, mini-jobs are interpreted as a form of anti-in-work-poverty policy. Scholars such as Kenworthy (Reference Kenworthy2015), Galassi (Reference Galassi2017) and Laun (Reference Laun2019) see mini-jobs as a kind of “in-work benefit” by exempting benefit recipients from tax and social security contributions aiming to “make work pay.”

Making-work-pay policies have been put forward in many countries to combat in-work poverty and to improve work incentives. In-work benefits are at the core of these policies (OECD 2009). In-work benefits are usually granted as tax reduction or as reduced social insurance contributions. Unlike such schemes in other countries (eg. the EITC in the US), mini-jobs are not designed as “in-work-benefit” although the mini-job reform in 2003 promoted the idea of marginal employment as a low-threshold to the labour market for low-skilled workers. Mini-jobs are not per se targeted at low-income earners as described above. Mini-jobs play a rather ambiguous role in the context of Germany’s comprehensive means-tested basic income system. The German welfare system for able-bodied persons – better known as “Hartz IV” – provides means-tested social protection for roughly 8 per cent of the working-age population and their families. Employed individuals with income from work below the defined household threshold might receive ALG II benefits as a top-up in combination with other income sources of the household. Hence, the basic income system itself provides a kind of “in-work benefit” without conditionality on hours of work as in other countries but based on the need of the entire household.

Against this background, the incentive to supplement the low income from a tax-exempted mini-job with welfare benefits (or vice versa) is strong. In turn, incentives to replace a mini-job by regular employment with extended working hours are low since 80 (90) per cent of earnings between 100 and 1,000 (1,001 and 1,200) Euros are withdrawn. Among the roughly 1 million employed benefit recipients (so-called “Aufstocker”) topping up low income from work with ALG II, about one third are mini-jobbers and only 12 per cent are working full time (BA-Statistics, 2020a). While the most common monthly income of ALG II claimants with a mini-job is 100 Euros – which corresponds to the free allowance in the Hartz IV scheme – mini-jobbers not receiving ALG II benefits earn on average around 400 Euro per month (Bruckmeier, Mühlhan, & Wiemers, Reference Bruckmeier, Mühlhan and Wiemers2018).

Overall, the design of the basic income system counteracts rather than incentivises the politically desired stepping-stone effect of mini-jobs. This is obvious, for example, in the case of single mothers – an important group among ALG II recipients. At the first sight, mini-jobs seem a way for single mothers to (re)-enter the labour market if they have been inactive for a longer period. Based on Panel on Labour Market and Social Security (PASS) data, Lietzmann (Reference Lietzmann2017) shows that the majority of single mothers are indeed taking up a mini-job when re-entering the labour market. However, only 4 per cent of them succeed in overcoming benefit dependency in the longer run. One reason for this might be the lack of childcare availability. PASS data, however, also suggest that this might be not the only reason as nearly one in four single women without children on welfare are also taking up only a mini-job within the first 3.5 years after benefit receipt.

Evaluation studies have generally shown that springboard effects of mini-jobbers are relatively rare even if the characteristics of employees and their working time preferences are taken into account (Brülle, Reference Brülle2013). Nonetheless, a bridging effect seems to exist for some groups such as long-term unemployed (Caliendo, Künn, & Uhlendorff, Reference Caliendo, Künn and Uhlendorff2016) or single and childless UB II claimants but only when taking up a mini-job several months after claiming benefits and looking for full-time employment (Lietzmann et al. Reference Lietzmann, Schmeltzer and Wiemers2017). However, about half of the mini-jobbers on welfare benefits are not looking for another or better-paid job. Many of them mention health reasons or seem to be discouraged by past failures in the search for a better job (Bruckmeier et al., Reference Bruckmeier, Eggs, Sperber, Trappmann and Walwei2015). While the springboard effect – or the lack of it – is a major issue in the political discussion in the German political landscape, the comparative social policy literature has failed to address this issue or just “overlooked” it, which in turn contributed to the misinterpretation of the scheme in the comparative social policy literature.

The unaddressed gender specific risks of mini-jobs

Largely ignored in the comparative research literature on work and welfare are the far-reaching consequences of mini-jobs for gender inequality. An exception is the contribution of Pfau-Effinger & Reimer (Reference Pfau-Effinger, Reimer, Nicolaisen, Kavli and Jensen2019) who claim that policies, which have strengthened mini-jobs have contributed towards reinforcing traditional structures of gender inequality (p. 261).Mini-jobs are indeed promoting the traditional gender roles in families, as they offer strong incentives for women to only work few hours. Gender-specific risks are particularly pronounced when holding a mini-job for longer, which is not only bad for women’s career development but contributes also to high pension gaps in later life. This is particularly relevant in the event of separation or divorce. Divorced women are facing a higher risk of poverty or social exclusion in older ages as mini-jobbers do not acquire sufficient entitlements of their own in the social security system. Working in a mini-job on a 450 € basis for about 10 years, a workers get less than 45 € pension per month in old age. These risks are shifted into the future and may become virulent even if the current level of protection is sufficient. Moreover, mini-jobs might also be detrimental for the longer-term career prospects of qualified women as they rather lock women in low-quality jobs instead of encouraging their mobility. A closer look at the activity level shows that – although the majority of female mini-jobbers aged 25–64 years old have a vocational or academic qualification – they work in rather low-skilled jobs and are often no longer considered as qualified workers.Footnote 7 Surveys also show that 55 per cent of female mini-jobbers have their mini-job on average more than 6 years, 34 per cent at least 10 years. Only 14 per cent who used to have a mini-job as their main occupation have later a full-time job (Wippermann, Reference Wippermann2012). Not surprisingly, the first official report on gender equality in Germany (Sachverständigenkommission, 2011) therefore blamed the impact of mini-jobs on female life-courses as “disastrous” in case mini-jobs are held for longer. Hence, mini-jobs provide only for a small percentage of women a bridge between previous inactivity and subsequent socially insured full-time or part-time employment (Klenner & Schmidt, Reference Klenner and Schmidt2012).

Affected women, however, often do not perceive mini-jobs as particularly risky – at least initially. Women choose to work in mini-jobs because the limited working hours do better align with their current life situation. Only in retrospect, they see this professional strategy as ineffective (Wippermann, Reference Wippermann2012). Bachmann et al. (Reference Bachmann, Dürig, Frings, Höckel and Martinez Flores2017) point to another subjective paradox. Although marginally employed women are, in principle, not reluctant to increase their working hours (Wanger, Reference Wanger2011) the share of those who desire employment subject to social security contributions is lower than the share of women who want to work more hours in a mini-job. Beckmann (Reference Beckmann2020) interprets this finding as a widespread desire to maintain the status quo, despite knowing the risks associated with this form of employment.

Awareness-raising campaigns organised by the public employment service (“Make more out of your mini-job”) or initiatives of ministries (“Fair work–Fair competition”) to convince mini-jobbers and employers to convert mini-jobs in regular part- or full-time employment seem to support this observation. The experience from these initiatives shows that it is not enough to inform women about the risks and disadvantages of mini-jobs. A prerequisite to motivate female mini-jobbers to expand working hours is the removal of the described financial disincentives such as spousal splitting in the tax system or the additional income regulations in the basic income system (MAIS, 2013).Footnote 8

In contrast to Beckmann (Reference Beckmann2020) who argues that the institutional nature of mini-jobs is less important than actual work preferences of married or partnered women (living in a registered partnership), I argue that preferences are shaped by institutional arrangements. Mini-jobs determine women’s responses to prevailing institutional environments reinforcing the “modified breadwinner model” (Lewis, Reference Lewis1992). This model is still the dominant employment pattern of German couple-households where the main income from (male) full-time work is supplemented with (marginal) part-time employment of the female secondary earner (Trappe, Pollmann-Schult, & Schmitt, Reference Trappe, Pollmann-Schult and Schmitt2015). The fact that mini-jobs are more widespread among women with children in West Germany than in East Germany (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Gundert, Kawalec, Sowa, Tesching and Theuer2015) reflects traditional gender norms inherent in the scheme. While West German social norms were traditionally opposed to maternal employment and childcare use, particularly for small children, this was not the case in East Germany. The dual-earner model of the former German Democratic Republic expected women to work full-time providing extensive childcare services – characteristic of state socialist economies. Despite the remarkable convergence towards the West German model of the modified breadwinner model since the mid-1990s, the different history of the gender-specific division of paid and family work is still present in the different use of mini-jobs in West- and East-Germany.

Discussion and outlook

Mini-jobs are a specific but stable segment of the German labour market for several decades now. The protection of mini-jobbers under social and labour law is characterised by paradoxes that affect the relationship between objective gaps in social and labour law protection, the knowledge of the risks of this form of employment and the resulting employment decisions of (female) workers (Beckmann, Reference Beckmann2020).

This review analysis has shown that the political rationale for mini-jobs is diverse and not limited to the deregulation of the peripheral labour market and its subsequent dualisation as suggested in the comparative political economy literature. By focusing one-sidedly on deregulation and dualisation strategies or likewise on mini-jobs as a strategy linked to anti-poverty policies, comparative research has widely ignored the continuity of the specific institutional feature of mini-jobs within the German employment and social security system. By taking over only pieces or stylized facts and focusing on partial aspects without understanding its preconditions in a broader historical context, the framing of seemingly similar patterns and developments of employment and social policies might lead to misinterpretations in terms of policy learning and institutional change.

Widely ignored in the comparative literature are supply sided motives. The popularity of mini-jobs is still closely related to tax and social insurance arrangements in a conservative welfare state where women are protected against the loss of their breadwinner through derived and supplementary rights to social security. The “marriage bonus” inherent in the German splitting model of the joint income taxation and the derived entitlement to social protection of inactive spouses reflects the continuity of traditional patterns of employment and working time. Hence, from a gender perspective, the mini-job scheme act as risky and misplaced incentives for (married) women to accept a model that implies dependence on the income of a partner or on transfer payments in the longer run. From a macro-economic perspective, the broad use of mini-jobs, particularly by married women is reflected in a pronounced gender “working time gap.” Compared to other European countries the hours worked per married woman (25–54) in Germany has remained flat in the past. Bick et al. (Reference Bick, Brüggemann, Fuchs-Schündeln and Paule-Paludkiewicz2018) see the main reason for this development in disincentive effects of the German tax system put on second earners.

Mini-jobs remain controversial in the German political landscape. The reasons to restrict or to strengthen the incentives for this peculiar employment scheme changed over time. However, there is still no political majority for its removal mainly because of its popularity among both, mini-jobbers and employers. Some political parties such as the Liberals and the Conservatives emphasise the contribution of mini-jobs to more flexibility for small- and medium-sized enterprises while others such as the Greens, the Left and the Social Democrats have called for a removal of the scheme by converting mini-jobs into employment fully covered by social insurance. Experts have also highlighted that in times of increasing labour shortages mini-jobs are a threat to securing a sustainable supply of skilled workers (Walwei, Reference Walwei2019). Mini-jobs have not stood the test in the COVID-19 crisis, either. One reason for its strong decrease since early 2020 is the fact that mini-jobbers are not eligible for the insurance-based short-time work allowance – the most important policy instrument to safeguard jobs in times of crisis in Germany.

Beyond economic reasons, there are mainly gender equality reasons, which require more far-reaching changes. Research has shown that gender norms can be changed by policy measures. This is most notable in the context of recent reforms on family policy such as the income–related German parental leave and benefit reform (Elterngeldreform) in 2007, which followed the Swedish model.Footnote 9 Evaluating this reform, Bergemann & Riphahn (Reference Bergemann and Riphahn2020) find strong labour supply effects driven by young mothers’ preferences for economic independence. Reforms in the early 1990s with extended parental leave entitlements had the opposite effect (Gangl & Ziefle, Reference Gangl and Ziefle2015). Politics, therefore, has to set clear orientations to make further progress towards more gender equality in the labour market. For this purpose, substantial reforms of the social security and tax system towards more individualization are necessary. The removal of mini-jobs could and should be the first step in this direction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Regina Konle-Seidl is a Senior Researcher at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB), Department “Migration and International Labour Studies”, in Nuremberg, Germany. She has longstanding experience in comparative research of labour market institutions, activating labour market and social policies. She has published on these topics in a variety of journals and co-edited the book “Bringing the Jobless Back into Work, Experiences with Activation Schemes in Europe and the US. She has collaborated in EU funded projects like the RECWOWE project “Regulating the risk of unemployment”– national adaptations to post-industrial labour markets in Europe”.