Introduction

In the light of the established welfare state literature, the Golden Age of welfare state expansion took place between 1950 and 1970, largely due to strong and encompassing trade unions and leftist parties (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Korpi, Reference Korpi1983). That is, the industrial class structure was the basis of political mobilization for left-wing parties; and if they were large enough to wield political power, it led to welfare expansion through the democratic process. This pattern goes hand-in-hand with a key finding in the party politics literature that wealth redistribution is a long-standing source of political disagreement (Lipset & Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967) and had been supported by the evidence of consistent class-based voting patterns through the late 1970s (Franklin, Mackie, & Valen, Reference Franklin, Mackie and Valen2009).

Although the traditional distinction between left and right based on class conflict became increasingly less relevant from the 1980s for various reasons, eg. changing electoral constituents the “left-wing” parties represent (Gingrich & Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015) or the rise of cultural cleavages based on post-material values cross-cutting class cleavage (Bornschier, Reference Bornschier2010; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1997), it is hard to deny that it was a critical political factor during the welfare expansion era for Anglo-European countries. However, as rightly pointed out by Gabel and Huber (Reference Gabel and Huber2000), the distinction between left and right should be relational, which has nothing to do with a priori issues or principles. What each means can vary from place to place over time and the context-specificity of this distinction has been made empirically clear by several studies (Inglehart & Klingemann, Reference Inglehart, Klingemann, Budge, Crewe and Farlie1976; Zechmeister & Corral, Reference Zechmeister and Corral2012). For instance, if we step beyond the conventional geographic boundary of welfare state analysis, it is not uncommon to observe regions whose major axis of party competition revolves around non-social welfare issues, eg. “ethnicity” and “regionalism” in many African countries, “religion” and “identity” for Middle Eastern countries, and “religion,” “ethnicity,” and “caste” in Southeast Asia (Deegan-Krause, Reference Deegan-Krause, Dalton and Klin gemann2007). Japan, Korea and Taiwan are no exception to this, since the most important political dividing lines emerged from foreign policy/national identity issues during the period of democratic transition and consolidation.Footnote 1

Given this political context, it is not surprising to see how the application of conventional welfare state approach to these countries has failed. For instance, from the perspective of classical welfare regime categories taking the power resources approach (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990), three countries share key characteristics of all three welfare regimes, such as achieving high levels of egalitarian welfare outcome (socio-democratic) with low social expenditure (liberal) based on stratified social-insurance system (conservative).Footnote 2 So far, students of the welfare state or party politics have paid only scant attention to why conventional variables/frameworks have minimal explanatory power for this region. Instead, East Asian particularity was simply attributed to these countries not having sunk roots in party politics or the welfare state (Croissant, Bruns, & John, Reference Croissant, Bruns, John and Croissant2002; Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1997), or treated as anomalies, which often resulted in removing them from the cross-sectional analyses. However, by 2017, Japan, South Korea (henceforth, Korea) and Taiwan were consolidated democracies, having passed Huntington’s (Reference Huntington1991) two turn-over tests and with the GDP per capita levels as high as the developed Western democracies, ranking 23rd, 27th and 33rd, respectively (International Monetary Fund, 2017).

Therefore, instead of labelling them as “premature” or “idiosyncratic,” the paper here will shed light on the politics behind socioeconomic dimension in a systematic manner by broadening the scope of analysis. That is, by examining the patterns of legislative proposals between 1987 and 2012,Footnote 3 it will show that minimal left–right differences in conventional social welfare policies do not mean that partisan difference lack socioeconomic implications. Beyond the conventional boundary of social policies (eg. pensions, healthcare and childcare), the three East Asian countries are characterized by their heavy reliance on particularistic benefits (eg. agricultural subsidies, construction projects or protectionist measures). Given the legacy of right-wing party dominance via particularistic benefits during the developmental state period (roughly between 1950 and 1990), such means of delivering welfare continued to be prioritized by right-wing parties even after the beginning of multi-party competition in the early 1990s. On the other hand, many conventional social welfare, such as long-term elderly care or childcare benefits, are relatively new and have been actively utilized as low-hanging fruits for vote-seeking politicians from both the left and the right.

This paper’s key contributions are twofold. First, it adds the partisanship dimension to the “social policy by other means” approach. Students of social policies have increasingly noticed various ways to protect people’s income from risk around the globe and emphasized their significance, which ranges from agricultural state support and squatter housing access in Turkey (Dorlach, Reference Dorlach2019), to friendly societies and mutual-aid organizations in the development in the UK (Harris, Reference Harris2004), to consumption subsidies and micro-credit schemes in East Asia (Gough, Reference Gough2001). However, what has been under-recognized from this line of scholarship is the role of party politics in general and partisan effect in particular. In this sense, a systematic investigation of elite-level partisan effect (or lack thereof) with an original bill sponsorship data set will fill a much-needed empirical gap. By incorporating particularistic benefits into the analysis, findings here add to the inductive attempts to define left and right between different countries over time. It does so by demonstrating a scope condition of the conventional partisanship argument on social welfare expansion and, instead of being nihilistic, show how partisan politics can be systematically understood if we direct our attention to “social policy by other means.” This broadened approach will be increasingly relevant to other developing or newly developed countries entering into multi-party competition.

Second, the paper considers both successful and failed legislative attempts by both left- and right-leaning parties. By doing so, it captures the partisan preference on conventional social welfare and particularistic benefits more accurately. So far, because the welfare state scholarship has focused on expenditure or a few landmark pieces of legislation, many of the less salient or not successful legislative attempts made by marginalized actors, such as opposition party members tended to be neglected. Examining only successful bills is particularly misguided in understanding the preference of political actors, since how particular legislative attempts become successful is more likely to be a result of actors’ capacity or surrounding situations – such as experience and expertise on issues, size of the political coalition or government type (divided or unified).

Political cleavage and East Asian context

Left versus right on big versus small government

From the reading of party politics literature, a long-lasting and key political dividing line is often labelled as “political cleavage” (Lipset & Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967) and is formed based on either structures or issues (or combination of both). For example, “structural cleavages” can be measured relatively easily with socio-demographic data like religion, income, ethnicity, race, language or location, whereas “issue/value cleavages” represent division between material and post-material values, hawkish and dovish foreign policy orientations (Lijphart, Bowma, & Hazan, Reference Lijphart, Bowman and Hazan1999) or democratic and authoritarian values (Berglund, Reference Berglund2013). In this sense, the key political cleavage during the welfare expansion stage can largely be found in labour versus capital in the structure, and big government (egalitarianism) versus small government (libertarianism) in the issues/values. Therefore, it can be said that both structure and issue cleavages overlapped and reinforced each other. Libertarianism emphasizes the idea of small government, and favours low tax, low deficit, privatization or minimal welfare provision, whereas egaritarian values emphasize the reverse. In this sense, the left–right dimension is often noted as a super-issue that represents the major ideological and politicized conflicts that are present in the political system (Gabel & Huber, Reference Gabel and Huber2000) which subsume a set of detailed issues. In relation to this, a large number of empirical results have demonstrated that the pro-state versus pro-market domain in economy has been highly correlated with the degree of left–right scale in the Anglo-European setting (Freire & Belchior, Reference Freire and Belchior2013; Thomassen, Schmitt, & Thomassen, Reference Thomassen, Schmitt and Thomassen1999). The prevalence of this economic dimension even granted it to be deductive tool. For instance, in measuring policy positions of parties in political space, scales proposed by Budge and Laver (Reference Budge and Laver2016) or Jahn and Oberst (Reference Jahn and Oberst2012) identify left and right with Marxist writings.

Going beyond the Anglo-European context, what counts as left and right in a particular country at a particular time should be inductively verified, rather than being simply extrapolated from the description of mainstream literature (much of which derives from experiences of Western and Northern European countries). In this sense, it is highly problematic to apply the same deductive tool to countries where big government versus small government tension has not been the centre of the mainstream politics. Japan, Korea and Taiwan are telling cases in this regard. For instance, the legacy of the right-wing party-led developmental state, by definition, indicates high levels of state intervention in economy. Japan’s government debt to the GDP ratio has risen steadily under right-leaning Liberal Democratic Party (henceforth LDP) governments, and reached 236 per cent in 2016 (OECD, 2016). Similarly, the right-leaning Chinese National Party (henceforth KMT) in Taiwan created many state owned enterprises in the past, whereas the left-leaning Democratic Progressive Party (henceforth DPP) favoured privatization of parts of the banking, telecommunications and utilities sectors. The inapplicability of conventional left–right distinction is also felt in the ground by legislators or journalists. For instance, when the National Health Scheme came into effect a full five years earlier than the KMT had originally planned, DPP legislator Chen chi-mai noted that the KMT, a so-called right-wing party, behaved much like the British Labour Party (Fell, Reference Fell2005). Similarly, The Economists (2017) attributes the LDP’s continued election victories in Japan to the party’s pragmatism, observing that, “Though often described as conservative, it is some ways an old-fashioned social democratic outfit.”

The best way to make sense of three countries’ counterintuitive patterns is to recognize the lack of the necessary pre-conditions of class-based political cleavage from both demand and supply side. As for the demand side, due to the legacies of post-war growth with equity,Footnote 4 the gap between the haves and the have-nots was narrow . This guaranteed a comparatively close social distance between social classes, which resulted in high levels of support for solidaristic values (Peng & Wong, Reference Peng, Wong, Castles, Leibfried, Lewis, Obinger and Pierson2010). Despite rapid economic growth, Japan, Korea and Taiwan had the low Gini coefficients on par with the Nordic countries. Reflecting this, at one point, Japan congratulated itself for having “a society of 100 million middle class people.” Implicit in this equitable growth is that the economic costs of redistribution are not as large as in other developing countries, many of which have experienced serious inequality problems during their growth stage.

Even from the perspective of political supply, related conditions were not favourable. Given the antagonist relationship/rivalry with neighbouring communist China and North Korea, an anti-communist/socialist norm has been strongly imposed (particularly in Korea and Taiwan). As a result, two central pillars of class-based politics have been lacking or significantly weakened: all three countries marginalised trade unions from national-level policy making through various means, such as allowing trade unions to be organized only at the firm level or forbidding their political activities (Deyo, Reference Deyo1987; Pempel and Tsunekawa, Reference Pempel, Tsunekawa, Lehmbruch and Schmitter1979); and Korea and Taiwan’s authoritarian military regimes legally forbid the creation of communist/socialist parties (or similar parties with redistributive appeals) (McAllister, Reference McAllister2007). Similarly, in Japan, many socialists and communists were imprisoned during the pre-war period, and after the war, they were divided by foreign policy issues (McElwain, Reference McElwain, Hicken and Kuhonta2014).

Despite the clear contextual difference, the deductive approach similar to western cases has been used either through direct applications of power resources theory using indicators, such as strikes, union density or percentage of votes for left party in the general election (Ahn & Lee Reference Ahn and Lee2012; Yang, Reference Yang2013) or more indirect applications using established welfare regime types (which is largely based on power resources theories) to categorize specific East Asian countries (Powell & Kim, Reference Powell and Kim2014). With an original bill-sponsorship data that is better designed to capture “preference” of left- and right-wing legislators, the validity of conventional approach will be explicitly tested here. The following hypothesis can be derived in light of the fact that the three countries are devoid of clear class-based political cleavages:

Hypothesis 1: There will be no difference between left- and right-leaning government periods in the prioritizing of a conventional social welfare.

Left versus right on particularistic benefits

Having insignificant partisan difference based on the mainstream definition of social welfare issues does not mean that partisan difference has no socioeconomic implications. Here, I will demonstrate that a clear left–right difference can exist beyond the conventional boundary of social policies.

It is well known to students of East Asian politics that other means (beyond conventional social welfare policy tools) of protecting people’s income while lessening social risks were widely adopted in Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Among others, it took the form of welfare benefits being (1) indirectly regulated/financed by the government by having other actors provide conventional welfare benefits, eg. mandatory private health care or (2) directly provided by government but in the form of other measures, such as industrial or agricultural policies that are functionally equivalent to conventional social welfare policies, eg. tax benefits and agricultural subsidies. As for the particular types, the previous works show that the three countries – particularly Korea and Japan – directed their policy attention to a wide range of particularistic benefits, such as enterprise-related fringe benefits (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2000), occupational pensions (Conrad, Reference Conrad2012), agriculture subsidies (Boestel, Francks, & Kim, Reference Boestel, Francks and Kim2013; Kim, Reference Kim2010), postal savings (Estevez-Abe, Reference Estevez-Abe2008), lump-sum retirement grants (Hwang, Reference Hwang2016) or construction projects (Saito, Reference Saito2010). The fact that most of the terms indicating these unconventionalFootnote 5 and particularistic measures are based on East Asian examples, which is a clear indication of the extensive usage, eg. “the welfare mix” (Rose & Shiratori, Reference Rose and Shiratori1986), “political side-payment” (Pempel, Reference Pempel1998), “welfare state in a broader sense” (Campbell, Reference Campbell2002), “functional equivalents” (Estevez-Abe, Reference Estevez-Abe2008), “social protection by other means” (Mishra, Reference Mishra and Kennett2004) or “surrogate social policy” (Chang, Reference Chang2004).

To list a few, Japan spent over one trillion U.S. dollars on construction projects and assistance for small- and medium-sized firms between 1992 and 2000 (Pempel, Reference Pempel2000). Moreover, construction projects are known to have long played a substantial role in Japan’s political economy, employing 10 per cent of the workforce and amounting to 15 per cent of Japan’s GDP (Woodall, Reference Woodall1996, p. 83). As for the agriculture protection, Japan and Korea are known for their extensive usage. Various measures taken by the government either took the form of protection, such as restricting imports on agricultural products that domestic farmers produce or setting quotas or directly raising farmers’ income through price supports or subsidies to purchase large-scale equipment (Boestel, Francks, & Kim, Reference Boestel, Francks and Kim2013).Footnote 6 Reflecting this, at one point, the agriculture sector in some rural regions in Japan like Gunma was protected by 990% tariff on imports (Kitschelt & Wilkinson, Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007).

Insofar as these unconventional benefits are concerned, there is a strong reason to expect partisan difference. The developmental state literature (Deyo, Reference Deyo1987; Pempel, Reference Pempel1998; Woo-Cumings, Reference Woo-Cumings1999) tells us that, between 1950 and 1980, Japan, Korea and Taiwan had a stable political–bureaucratic connection guaranteed by one-party dominance, whose linkage with voters tend to be based on exchanges of particularistic goods, services or regulations. Taiwan’s “black and gold” politics (Chin, Reference Chin2003), Japan’s “pork-barrel” politics (Fukui & Fukai, Reference Fukui and Fukai1996) and Korea’s “imperial presidency” (Park, Reference Park2008) are good manifestations of these phenomena. Considering the fact that the current major right-wing parties in the three countries are basically the same parties of the one-party dominance era, it is not unreasonable to expect that they are more likely to support and provide these particularistic benefits even after 1990 with the entrenched provision networks they built over decades.

For instance, in Korea, political parties tend to form clientelistic networks linking resource-rich presidential candidates with local-level individual candidates and their machines. This pattern can be traced back to president Park Chung Hee, who received large-scale donations from the business and used the Blue House to initiate large-scale investments in the Youngnam area in the hope of receiving votes. In Japan, it is well known that the post-war electoral system incentivized same-district LDP candidates to engage in cut-throat competitions for the same types of voters (Rosenbluth & Thies, Reference Rosenbluth and Thies2010). In distinguishing themselves from other co-partisans, politicians not only relied on their faction within the LDP, but also built personal political machine – koenkai – to curry favours to their constituents in the form of direct pork-barrel spending from the national budget. In addition, policy tribes with expertise on specific field, such as construction or agriculture – zoku-giin – played a role of mediator between bureaucrats and politicians, thereby consolidating the system. Similarly, in Taiwan, “black gold” politics indicates the involvement of gangsters, corruption and illegal financial transactions. Akin to the LDP in Japan, the long-ruling KMT is known for its intra-party factions and emphasis on agricultural subsidies and construction projects. As noted by Fell (Reference Fell2005), the KMT-local faction patron–client relationship was maintained by local executives’ considerable power over particularistic welfare benefits. This process often involved gangsters in politics and clientelisitc activities ranged from insider trading on the stock exchanges, big public construction projects, business licenses and military purchases Fell (Reference Fell2005).

As can be clear from aforementioned examples, goods, services or regulatory favours utilized by politicians during the developmental state period were highly particularistic in nature in all three countries. This can be attributed to the fact that Korea and Taiwan had been clear authoritarian countries during this period, and while Japan was nominally democracy, the low level of party competition and one-party dominance over the four decades made the country to operate similar to “soft authoritarianism” (Johnson, Reference Johnson and Deyo1987). In relation to this, a key piece of insight can be drawn from De Mesquita et al. (Reference De Mesquita, Smith, Morrow and Siverson2003) who argue that there will be mixture of public and private goods for any regime type, but more private goods are likely to be provided when the level of democratic competition is low. This is because, by definition, lower level of democracy indicates, it only requires a small circle of key supporters to maintain the regime and, therefore, there is no need to provide public goods. Usually the small circle of supporters includes organized groups with identifiable features, eg. ruling party members, soldiers, landowners, civil servants, teachers, industrial workers or business groups (Knutsen & Rasmussen, Reference Knutsen and Rasmussen2018). Because retracting the support from these groups can increase the chance of regime collapse or leadership change, a wide range of private goods tend to be provided to them. These can take either a direct material form, eg. fertilizers, subsidized housing, food, construction materials, food (Magaloni & Kricheli, Reference Magaloni and Kricheli2010) or an indirect form, eg. regulatory favour, policy influence, access to economic rents, political posts (Ezrow & Frantz, Reference Ezrow and Frantz2011), with material implications. By and large, these private goods are discretionary distributions which do not take the form of conventional social welfare.

Despite their prevalence of particularistic benefits prior to 1990, the decreasing trend of particularistic benefits has been noticed in the relevant literature (Mishra, Reference Mishra and Kennett2004; Noble, Reference Noble2010). This is not surprising if one considers changes, such as: (1) high levels of party competition led each party to make greater programmatic efforts to attract a wider range of people and (2) increasing market forces and worldwide competition pressured the three countries to open their economies and make protective economic measures less feasible options.

However, policy-orientation is highly path-dependent. As pointed out by Pierson (Reference Pierson2001), policies create politics and four inter-connected aspects of politics – importance of collective action, high density of institutions, possibility of using political authority to perpetuate power asymmetry, and intrinsic complexity – make it more conducive to positive feedback. And at the group level, the path-dependent nature becomes even more apparent as ideas are shared by other actors and make particular norms appropriate as collective and self-reinforcing processes. Japan, Korea and Taiwan are no exception to this. Clientelistic norms and related networks right-wing parties developed to capture voters through particularistic benefits during the one-party dominance period would not easily disappear even after the beginning of multi-party competition. For instance, during the one-party dominance period, Japan’s LDP developed a web of institutions to further their electoral advantage, such as the koenkai (vote-mobilization machine), within party-level factions, zoku-gin (policy tribes) and PARC (Policy Affairs Research Council). Noted by Krauss and Pekkanen (Reference Krauss and Pekkanen2010), these institutions are complementary in nature and have coevolved over time. Moreover, a dense web of institutions in the political domain have become intertwined with the economic domain at the levels of individuals, firms and organizations (Witt, Reference Witt2006), reinforcing the positive effect of path dependency through denser and more complex institutions. Even after the beginning of multi-party competition and the change of electoral rule in the early 1990s, their utility has not vanished (although it has weakened) and they continue to serve the electoral purpose of right-leaning party members. Indeed, they continue to respond to the expectations of LDP supporters, many of whom are based in rural areas or related to specific industries as vested interests. Although the specific clienteles and the mode of party-vote exchanges vary between presidential Korea and Taiwan and parliamentary Japan (Park, Reference Park2008; Wang, Reference Wang and Ayşe1994), high degrees of path dependency of clientelistic practices by right-leaning parties through particularistic benefits are likewise expected (Fell, Reference Fell2012; Hellmann, Reference Hellmann2014). Against this backdrop, we can expect a clear partisan difference over particularistic benefits between left- and right-leaning parties even after entering the multi-party competition period in the early 1990s.

Hypothesis 2: Particularistic benefits will be prioritized more during right-leaning than left-leaning government periods.

Data and definition

The paper here taps into the whole universe of sponsored bills between 1987 and 2012 to examine the impact of partisan difference on the legislative agenda setting of socioeconomic issues. First and foremost, bill sponsorship data are used because legislation has brought about the most substantial changes for electors on conventional social welfare over the past two decades – for instance, increased parental leave, extending unemployment insurance coverage or universal means-tested income support. Moreover, sponsorship data provide a rich source of information on legislators’ preferences and priorities. Specifically, sponsoring a bill is an opportunity to express support for a certain issue through which a legislator can send signals to median voters (Kessler & Krehbiel, Reference Kessler and Krehbiel1996). Although the amount of effort a legislator puts into sponsoring a bill can vary, legislators take this task seriously since bill sponsorship history is public record and, in turn, a source of praise or criticism (eg. by Tokyo Press Club in Japan, NGO Monitor Group in Korea or Citizen Congress Watch in Taiwan). Finally, unlike other elite-level data sets, such as manifestos or expert surveys, bill sponsorship data sets exist continuously during the period of observation for all three countries and requirements and processes of legislation submission and deliberation are highly comparable (for details, see Appendix 1).

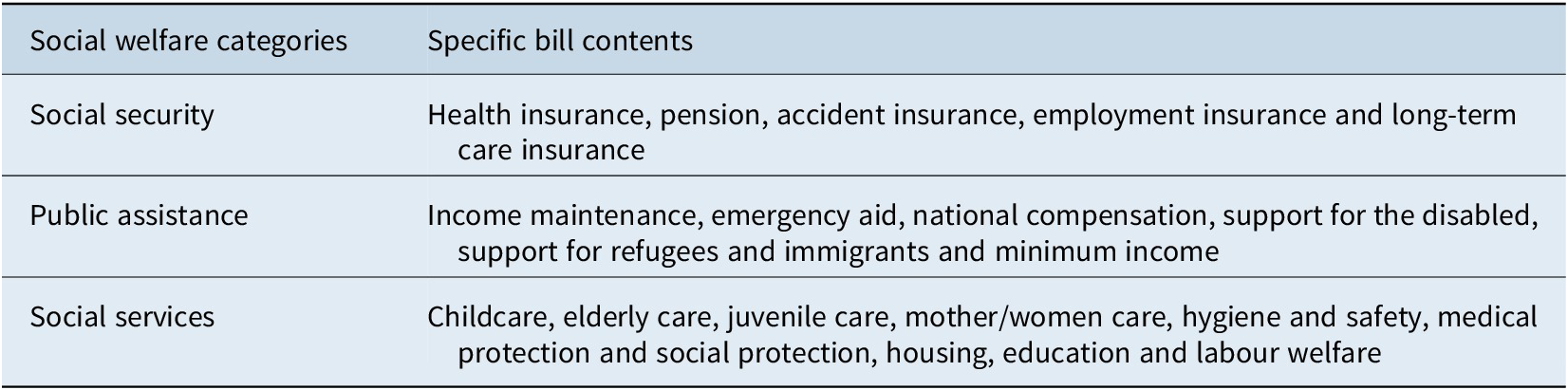

In the light of these sponsorship data, every submitted bill concerning the social policy issue areas listed in Table 1 is coded as “conventional social welfare” based on the bill’s title and key summaries in official government documents.Footnote 7 Of the total bills submitted (45,584) during the observed period, roughly 15–25 per cent fall into the “welfare” category in each country (6,608 in Korea, 1,247 in Japan and 1,771 in Taiwan).

Table 1. Categories of conventional social welfare.

In addition to the conventional boundary of social policies, the paper extends its scope to other means to protect people’s income and risks many of which had been frequently utilized during the developmental state period by right-leaning governments. Drawing from the previous empirical works based on the three countries, the other means tend to be discretionary benefits. Among others, sponsored bills concerning tax breaks/exemptions, subsidies, labour market protections, infrastructure projects and state-induced private welfare arrangements that are targeted towards particular organized groups or geographical constituents are selected and separately coded as “particularistic benefits” (4,651 in Korea, 812 in Japan and 1,391 in Taiwan).Footnote 8

All the submitted bills are coded as “conventional social welfare,” “particularistic benefits,” or “others.” In case a bill includes multiple changes beyond one category, it is coded as just one category based on the bill title and the primary emphasis in its introductory part – as well as the number of changes. This way of coding makes the three categories mutually exclusive, and totally exhaustive.

Regression analysis and interpretation

Regression analysis

The central point that this paper tests is whether significant partisan difference exists in promoting conventional social welfare or particularistic benefits. To this end, three models examine partisan influence based on the government’s ideological spectrum (left-leaning 0 and right-leaning 1) during a particular time period8 (defined by the president/prime minister’s known political orientation; Appendix 2 includes detailed coding). Model 1 examines the partisan effect during particular left-/right-wing government periods; the whole universe of bills sponsored by both the executive and legislative branches are included. In contrast, Models 2 and 3 are confined to bills sponsored by the executive branch (Model 2) or legislative branch (Model 3).

As specified earlier, a threefold distinction is made in submitted bills (social welfare 0, particularistic 1 and others 2) and multinomial regressions are applied to test the two hypotheses of this paper. Specifically, Model 1’s regression results are divided into three parts: Model 1a examines the potential partisan effect on conventional social welfare (others versus social welfare), while the partisan effect on particularistic benefits is tested with Model 1b (others versus particularistic benefits) and with Model 1c (social welfare versus particularistic). For each model, the left-side category is used as the base.

Control variables draw from welfare studies, legislative studies and political contexts of the three East Asian countries. For both Models 1 and 2, these include: (1) legislative result of a bill (failure 0 and success 1); (2) annual GDP per (continuous and logged) capita from the IMF database; (3) annual party cohesion level (continuous and logged) from the Varieties of Democracy database (Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt, Tzelgov, Wang, Krusell and Miri2017); (4) type of legislative initiative (enactment 0 and amendment 1); (5) country dummy (South Korea 0, Japan 1 and Taiwan 2); (6) electoral reform (whether a bill was submitted before the electoral reform 0 or after 1); and (7) individual bill sponsor dummy (distinguished by names of presidents/prime ministers for executive bills and by names of primary bill sponsors for legislative bills). Most of these control variables are self-explanatory, but the following three deserve specification.

The first is the economic growth rate. As noted by Haggard and Kaufmann’s (Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008), having fewer fiscal constraints can be a crucial condition for a more generous and universal welfare expansion. Despite similarities in developmental path and economic structure, Korea and Taiwan had had a more favourable economic environment than Japan for most of the period between 1987 and 2012. Therefore, this potential difference had to be controlled with the annual GDP growth rate. Second, “type of legislative initiative” is an important aspect to consider since amending a bill is, in general, substantially less time-consuming and politically tricky than enacting a bill, which is making a bill from scratch. Third, as for the electoral reform, three countries changed their electoral rule to a two-tiered system during our period of observation – general elections starting from 1996 (Japan), 2004 (Korea) and 2008 (Taiwan). Japan and Taiwan had a highly person-oriented electoral rule before the electoral reform and established works in electoral studies show the reform made the politics more median-voter friendly and programmatic (Rosenbluth & Thies, Reference Rosenbluth and Thies2010). Even in Korea, the electoral reform is expected to have a positive effect on welfare because seats in the party tier were filled in proportion to seat share in the district tier before the reform, while after the reform, key parties in both countries have nominated a wide array of nation-level experts or representatives, eg. child experts, nurses, doctors, the disabled or NGO representatives.

The regression results are based on robust standard errors clustered around individual bill sponsors; errors are reported in parentheses.

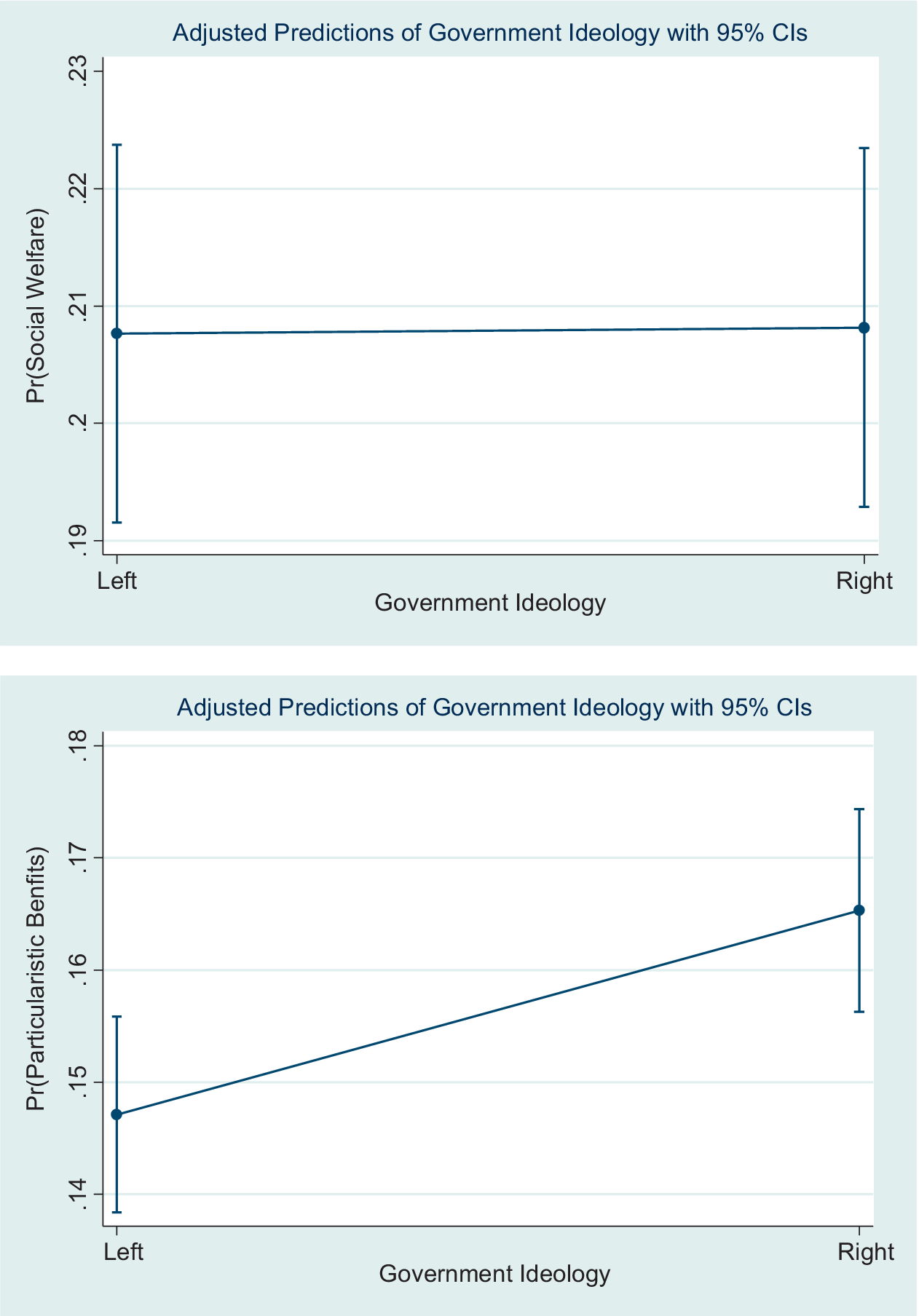

Based on Model 1a in Table 2, it can be said that government ideology does not affect prioritizing conventional social welfare bills over other bills. However, when we focus on particularistic benefits in Models 1b and 1c, government ideology becomes statistically significant at the five per cent level – during right-leaning government periods, more particularistic benefits are likely to be sponsored both compared to other bills (Model 1b) or conventional welfare (Model 1c). Figure 1 illustrates the marginal effect of known left–right ideology on conventional social welfare over others (Figure 1 top) and particularistic benefits over others (Figure 1 bottom). What is clear is that moving from left- to right-leaning government periods does not affect the likelihood of a submitted bill being conventional social welfare, while it increases a submitted bill being particularistic benefits. This contrasting pattern is clearly in line with the expectation derived from the path-dependency logic (Hypothesis 2) but not the power resources theory (Hypothesis 1).

Table 2. Logistic regression results testing the effect of government ideology (all bills).

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.5; *p < 0.1.

Figure 1. Marginal effect of left–right ideology on particularistic benefits.

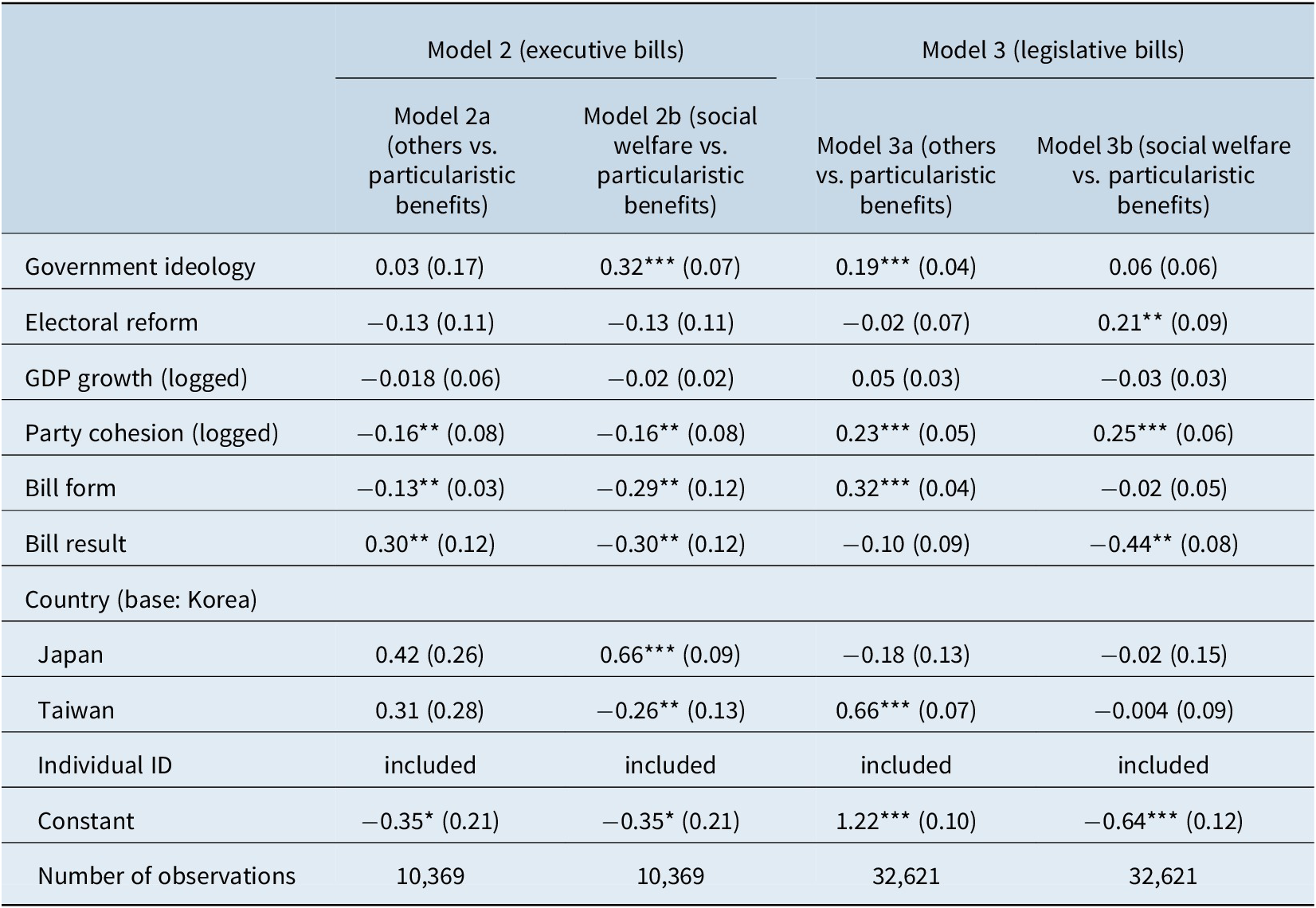

For a more nuanced understanding of positive relations between right-leaning government periods and particularistic benefits, Models 2 and 3 separate out submitted bills by government branches – executive and legislative – and repeat tests of Hypothesis 2 with the same variables that are utilized for Model 1. The key motivation behind dividing the two government branches stems from the expectation that the right-leaning government’s partisan bias on particularistic benefits will be observed to a greater extent in executive bills when compared to legislative ones. On the one hand, executive bills directly originate from the president/prime minister (who signs these bills, as the head of the executive branch) in the three countries. This is thus expected to be directly related to the key explanatory variable of this paper – government ideology – measured as the president/prime minister’s known ideological spectrum. On the other hand, legislative bills stem not only from right-leaning ruling party members but also from left-leaning opposition party members. Due to the immanent heterogeneity of legislative bills, prioritization of particularistic benefits is expected to be less pronounced during right-leaning government periods when compared to executive bills.

The results in Models 2 and 3 in Table 3 are mixed in relation to government branch-specific expectations. When it comes to prioritizing particularistic benefits over social welfare, the effect of right-leaning government periods was clear for executive branch bills (Model 2b), whereas the effect disappeared for legislative branch bills (Model 3b). That is, the odds of a submitted bill targeting particularistic benefits over social welfare increases more than 39 per cent moving from left- to right-leaning government periods for cabinet bills (statistically significant at the five per cent level). Considering the level of increase for equivalent change was roughly 12 per cent in Model 1c, it can be said that legislative bills were masking the partisan effect of right-leaning governments’ tendency to prioritize particularistic benefits over social welfare through cabinet bills. However, as for the legislative emphasis on particularistic benefits over others, the results show no effect of partisan bias for executive branch bills (Model 2a) in contrast to the clear bias existing for legislative branch bills (Model 3a). The contrasting legislative patterns between the two branches can be understood as different roles and incentives of each branch within the government. Cabinet members are in charge of keeping the government resources so are in the position to be highly selective in distributing them. At the same time, they should engage in a huge scope of activities going beyond distributive concerns. For these reasons, it can be said that partisan bias on particularistic benefits over social welfare bills, but not over other bills. In contrast, members of legislative branch can afford to be much less concerned about future fiscal implications of bills they introduce. That is, as long as they can further their electoral prospective, they utilize both particularistic and social welfare benefits. All in all, the results suggest that right-leaning government periods’ focus on particularistic benefits at the aggregate level is a combined result of both the executive (prioritizing particularistic benefits over social welfare) and legislative branch (prioritizing particularistic benefit over others).

Table 3. Logistic regression results testing the effect of government ideology (bills by executive and legislative branch).

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.5; *p < 0.1.

Although it is included as a control variable in this paper, the effect of electoral reform merits our attention. According to the logic derived from the existing literature, electoral reform is supposed to increase the priority given to conventional social welfare policies by making party competition more programmatic. The results in Models 1a and 1c confirm this (statistically significant at the five per cent level). However, when we compare particularistic benefits in relation to other bills (Model 1b), electoral reform did not make any systematic difference. As far as executive bills are concerned, as is clear from the lack of statistical significance in Models 2a and 2b, electoral reform did not bring about the intended changes. From this, it can be said that the effect of electoral reform on legislative behavior has been confined to legislative branch members. Finally, to corroborate the continuing partisan bias even after electoral reform, separate multinomial logistic regressions were run only with the bills submitted after each country’s electoral reform (not presented here due to limitations of space). The partisan bias observed in Models 1a and 1c did not disappear (statistically significant at the one per cent level), confirming the path dependency of positive relations between right-leaning parties/government periods and particularistic benefits.

Further evidence

For the sake of robustness check, each conventional social welfare category described in Table 1 was removed from the models in the regression analyses to test if the presented results are sensitive to the definition of social welfare. Similarly, given the potential for post-treatment bias, the bill success rate variable was removed from every model. In addition, considering the fact that Taiwan was still an authoritarian regime between 1987 and 1992 (unlike Korea and Japan), separate regressions were run removing bills submitted during this time period. All of the findings presented so far were not once altered.

However, there can still be left–right difference in all three countries if we examine the quality of social welfare bills closely. For instance, if we consider the direction and significance of each welfare bill, social policy bills sponsored during right-wing government periods can be rolling back social welfare benefits or expanding insignificant ones just for the signaling purposes. These are valid concerns, so I first checked whether social welfare bills introduced during the right-wing government periods are less significant and less likely to be expanded. I randomly sampled 300 from each country (150 from left-wing and 150 from right-wing government period) and coded the substantiality and direction of successful welfare bills according to the coding schemes employed in the previous works to distinguish social policy bills (significance: trivial or notFootnote 9; direction: expansion or notFootnote 10). And the result showed that, not in one country, social policy bills are less likely to be significant during right-wing government periods than the rest; and 85–95 per cent of submitted social welfare bills fall into the “expansion” category without differing substantially between left- and right-wing government periods. The same concern applies to particularistic benefits, so I randomly sampled 150 from each left- and right-wing government period and examined the direction and trivialness based on the same criteria. And, again, there was not left/right government difference.

Moreover, in addition to the presented quantitative evidence, qualitative evidence also resonates with the key patterns observed here – partisan indifference on conventional social welfare while clear gap on the extent to which left- and right-wing governments prioritize on particularistic benefits.

For instance, when it comes to conventional social welfare, so-called “left-wing” and “right-wing” parties seem to be frequently leapfrogging into each other’s domain. On the one hand, in Korea, the right-leaning Grand National Party came up with a “life-long customized welfare” package (which consists of nurturing, education, employment, housing and elderly care) in October 2011 and went further by changing its name to the Saenuri Party, which included “building happy welfare state” at the top of the party platform. In Taiwan, the right-leaning KMT hi-jacked the national health insurance issue from the opposition DPP and fast-tracked the legislative process in 1994. In Japan, emphasizing economic growth and fair distribution of its fruits to every sector of society, the ruling and right-leaning LDP promulgated 1972 as “the year one of welfare state” and institutionalized free medical service for the elderly.

On the other hand, in Korea, left-leaning President Roh Moo Hyun announced Free Trade Agreement negotiations between Korea and the United States in 2006, and was labelled as a “left-wing neoliberal.” In Japan, the left-leaning Democratic Party Japan showed pro-neoliberal orientation in the 1990s, advocating market reforms against the LDP’s construction state. Likewise, in Taiwan, the left-leaning DPP administration actively implemented neo-liberal policies, such as waiving trade tariffs, lifting commercial restrictions, privatizing state owned enterprises between 2000 and 2008.

If we shift our attention to particularistic benefits, there has been a clear tendency for right-leaning governments to utilize this form more. That is, even after entering the multi-party competition since the early 1990s, evidence clearly suggest the attachment of right-wing parties to particularistic benefits continues. For instance, in Korea, the right-leaning president Lee Myong Bak launched the Grand Canal project extending 540 km and 34 new town projects (in the Seoul metropolitan area alone) causing speculative real-estate investments are two major illustrations of this and closely linked to the increase of national debt by more than 180 billion Won. Likewise, in Taiwan, the ruling KMT focused on construction projects, such as the Taipei metro project or the Six Year Development Plan in the early 1990s. Similarly, after his 2008 election, President Ma launched i-Taiwan 12 Projects, which includes urban renewal projects, revitalization of export processing zones and development of high-speed rail stations with an expected price tag of NT$3.995 trillion. In Japan, upon returning to the power in December 2012, the right-leaning LDP promised to boost public works by spending 200 trillion yen on projects over the next decade – roughly 40 per cent of Japan’s economic output.

In the light of this, it is not surprising to observe high-level tension between the “machine-owing” right and “machine-breaking” left in the three countries. In Korea, upon his inauguration, left-leaning President Roh Moo-Hyun’s government passed new campaign funding laws – banning corporate contributions to election campaigns, setting campaign spending limits, and increasing the amount of public funding to political parties – to minimize the influence of money politics. In Japan, after dethroning the LDP in 1993, the top priority of Hosokawa’s coalition government was to change the money-politics prone electoral rules and outlaw political donations to individual politicians or their personal fundraising organization. Similarly, the left-leaning DPJ government slashed public works budgets by a third to damage the pipeline of LDP’s pork barrel politics between 2009 and 2012. In the case of Taiwan, the DPP’s constant attempts to cut down government structure and privatize state-owned enterprises stem from similar motivations.

Concluding remarks

As the bill sponsorship evidence clearly demonstrated, conventional social welfare issues have not polarized left- and right-leaning political actors in Japan, Korea and Taiwan. This echoes with a plethora of empirical evidence drawn from mass opinion surveys, public voting patterns, party manifestoes, legislative speeches and legislative voting also confirm that income, occupation status or views on social welfare issues have not been the key predictor in pubic voting or legislative behaviour in the three countries (eg. Hsieh & Niou Reference Hsieh and Niou1996; Jun & Hix, Reference Jun and Hix2010; Kim, Choi, & Cho, Reference Kim, Choi and Cho2008; Proksch et al., Reference Proksch, Slapin and Thies2011). Lack of clear differences on conventional social welfare issues notwithstanding, the paper goes beyond non-finding and shows how “left” and “right” in these countries have socioeconomic implications in light of the developmental state trajectories. This is evidenced by right-leaning parties’ attachment to particularistic benefits, such as agricultural subsidies and construction projects. This pattern clearly indicates that we should avoid uncritically equating welfare expansion or retrenchment with the governance of left- or right-leaning parties, as if their identities and intentions are similar to those of social democratic and liberal parties – big government versus small government – in established welfare states during the expansion stage. Instead, by taking an inductive approach to left–right difference, the paper shows that contextualizing key political actors’ preferences can lead to a more systematic understanding of political dynamics behind the socioeconomic dimension in non-Anglo-European countries. Moreover, it contributes to the growing body of “social policy by other means” literature by demonstrating the partisan effect.

To clarify the main argument once more, the fact that politics is not polarized on conventional social welfare issues does not necessarily mean left- or right-leaning parties do not take conventionally perceived “left” or “right” measures in the three countries. For instance, in Korea, the right-wing party rubber-stamped a labour flexibility law in 1996 and decided to close down Jinju Medical Centre in 2013 for profit reasons. Prime Minister Koizumi in Japan implemented several neo-liberal reforms postal privatization and a record level four per cent cut in medical treatment fees in November 2005. Similarly, Taiwanese President Ma was behind the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) between mainland China and Taiwan in 2010. However, the key point I want to convey through this paper is that these seemingly rightist or leftist measures have been easily reversed for the sake of electoral gain. For instance, in Japan, even if the LDP supported the idea of welfare state in the 1970s, it had changed its position in the 1980s and emphasized individual/family responsibilities in the 1980s with a new catch-phrase “Japanese style welfare society.” Similarly, the DPJ shifted in emphasis from a neoliberal party to a pro-welfare party to maximize their electoral prospect before the 2009 general election (Rosenbluth & Thies Reference Rosenbluth and Thies2010). In contrast to the frequent leap-frogging parties conduct on conventional social welfare issues, we see a relatively stable patternFootnote 11 of right-leaning parties prioritizing particularistic benefits (in the form of infrastructure projects or subsidies for particular groups and regions).

As for the policy implications of the paper’s findings, previous works from Eastern European and Latin American countries show that when voters struggle to identify parties with a particular stance, the necessary accountability mechanism – reward or punishment according to a party’s performance or prospects – of representative democracy becomes obscured (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1999; Luna & Zechmeister Reference Luna and Zechmeister2005). Going beyond producing an accountability deficit, the fact that conventional social welfare issues are associated more with politicians’ vote-seeking than policy-seeking incentives in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan means more chance of over-promising and under-delivering by politicians. Validating this concern, a lack of trained carers or facilities infrastructure, budget shortages of local governments implementing welfare services, illegal benefit recipients and ad hoc funding secured from luxury goods/gambling/alcohol/tobacco taxes have been frequently occurring problems in the three countries. Such implementation failures have been an underexplored area in welfare politics, and merit serious academic attention in future works from the integrated perspective this paper takes.

Acknowledgements.

I would like to thank Laura Seelkopf, Peter Starke, Shih-Jiunn Shi, Elena Korshenko, Tim Dorlach, and Gibran Cruz-Martinez for reading and commenting extensively on prior versions. I would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. All remaining errors and shortcomings are mine.

Jaemin Shim is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at the German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA). His primary research interests lie in democratic representation, comparative welfare states, gender and legislative politics. His works have appeared or are forthcoming in Democratization, Parliamentary Affairs, and Journal of Women, Politics and Policy.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Bill sponsorship requirements

Based on the details specified in the constitution of each country, all three countries allow bills to be submitted by both the legislative and executive branch. This makes the three nations more comparable, since the different origin of bill sponsorship can allow us to distinguish preferences between the executive and legislative branch. In the case of legislator-proposed bills, each legislator must have the support of 10 or more members of the upper house and 20 or more members of the lower house (in Japan), while 10/15 or more members of the parliament are required in Korea/Taiwan (the threshold used to be 20/33 until 2003/2008 in Korea/Taiwan). Although the number varies over time, there have been approximately 500 lower house members and 250 upper house members in Japan, while roughly 300 house members in Korea. In contrast, the number used to be 225 in Taiwan before 2008 but halved to 113 after that. For Korea and Japan, some bills can be submitted as “the standing committee head,” and for this, there is no co-sponsorship requirement and submitted bills are usually bi-partisan featuring more than 90 per cent success rate. In Taiwan, although there is not a separate distinction for this category, it has its own unique category as some bills can be submitted at “party caucuses.”

Appendix 2: Ideological spectrum of parties and period coding

Ideological Spectrum of Particular Government Periods (based on left–right distinctions in established empirical works conducted by party politics experts covering Korea, Japan, and Taiwan)

In Japan, the ideological spectrum of particular government period is coded as “left” when it was under the coalition party majority government by the DPJ (2009.9–2011.7) or coalition governments headed by the non-LDP prime ministers (1993.8–1995.12), and “right” under the LDP prime-minister periods (the rest). In Korea, specific period is coded as “right” when it was under Roh Tae Woo (1987.12–1992.12), Kim Young Sam (1993.1–1997.12) or Lee Myung Bak (2007.12–2012.12) government periods and “left” when it was under the President Roh Moo Hyun (2003.1–2007.12) or Kim Dae Joong (1998.1–2002.12). For Taiwan, the period is coded as “right” when it was governed by Lee Teng Hui (1988.1–2000.3) or Ma Ying-jeou (2008.3–2012.12), and “left” for Chen Shui-bian’s presidency (2000.3–2008.2).