1. Introduction

Domestic revenue mobilization has received increased attention in the development policy debate over the last decade (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Prichard and Fjeldstad2018; Ricciuti et al., Reference Ricciuti, Savoia and Sen2019; World Bank, 2017). Recently, voluntary tax compliance is considered to be important for domestic revenue mobilization both by policymakers and researchers, as the traditional methods to improve tax compliance, such as increased audits, can be costly to implement. The literature has provided an array of theories and evidence attempting to explain variation in citizen's voluntary tax compliance. These studies, in general, focus on the quality of institutions and social norms as important determinants (see Luttmer and Singhal, Reference Luttmer and Singhal2014 for an overview). However, they do not provide adequate explanations on the root causes of variation in the quality of institutions and norms that lead to differences in tax compliance. Our paper contributes to the literature by examining the role of pre-colonial centralization in explaining the variation in citizens' tax compliance norms in contemporary Uganda.

We focus on Uganda for several reasons. First, Uganda has a long history of strong pre-colonial institutions that continue to play an important role in the lives of ordinary people (Englebert, Reference Englebert2000, Reference Englebert2002). Second, focusing on one country allows us to exploit the within-country variation in pre-colonial institutions that are not affected by national institutions or the identity of former colonial rule. Third, Uganda's tax-to-GDP ratio of 11.5% is lower than the Sub-Saharan average.Footnote 1 Although significant improvements have been made in tax administration, low compliance continues to undermine domestic revenue mobilization efforts in Uganda. The study provides policymakers with knowledge of the role of deeply rooted pre-colonial institutions in shaping citizen's willingness to pay taxes. Since Uganda is not the only African state whose territory was home to a heterogeneous political landscape in the pre-colonial era (Englebert, Reference Englebert2000; Michalopoulos and Papaioannou, Reference Michalopoulos and Papaioannou2013; Wilfahrt, Reference Wilfahrt2021), the findings of this study may also have broader empirical traction on the continent.

The pre-colonial political organization in Uganda can be classified as both centralized and stateless societies. In centralized polities, the states had a complex system of tax collection based on detailed information about the available taxable resources at the village level (Kjær, Reference Kjær2009; Ssekamwa, Reference Ssekamwa1970). European colonizers preserved the capacity of pre-colonial centralized states by consolidating the position of kings and chiefs (Mamdani, Reference Mamdani1996) and continued to rely on the pre-colonial hierarchical structure to administer the locals including collecting taxes (Tuck, Reference Tuck2006).

Our empirical strategy proceeds as follows. First, we combine geo-referenced anthropological data on pre-colonial ethnic homelands with micro survey data from several rounds of the Afrobarometer Survey (AB). Second, to account for possible biases that may arise from unobservable local geographic features, we follow the estimation strategies used in Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (Reference Michalopoulos and Papaioannou2013) and perform regression discontinuity analysis (RDA) on individuals that reside close to the borders of neighboring ethnic homelands with different levels of pre-colonial centralization. The huge variance in the levels of pre-colonial centralization across different areas of Uganda provides us with a unique opportunity to implement the RDA.

We find that pre-colonial centralization is correlated with a higher tax compliance norm. We further examine three underlying mechanisms by focusing on persistence in citizens' belief about the need to obey authority (Lowes et al., Reference Lowes, Nunn, Robinson and Weigel2017), the quality of institutions (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001), and social cohesion (Grosjean, Reference Grosjean2011). The results suggest that the higher tax compliance norm in the historically centralized parts of Uganda is explained by the legacy of state's capacity in upholding authority and a strong social cohesion through higher interpersonal trust, but not through better quality public institutions.

Our paper is related to empirical studies that examine the role of pre-colonial institutions on current development outcomes in Africa. Pre-colonial centralization is found to be strongly correlated with development both at the national level (Gennaioli and Rainer, Reference Gennaioli and Rainer2007) and locally (Michalopoulos and Papaioannou, Reference Michalopoulos and Papaioannou2013). However, the underlying mechanisms through which pre-colonial institutions affect long-run development remain weakly understood. Moreover, these studies use cross-sectional analysis that lacks the richness that historical studies can bring to explain the variation within countries (Heldring, Reference Heldring2021; Lowes et al., Reference Lowes, Nunn, Robinson and Weigel2017). An exception to these cross-sectional studies is a study on Uganda by Bandyopadhyay and Green (Reference Bandyopadhyay and Green2016) who find a positive correlation between pre-colonial centralization and well-being, but no correlation with public goods. Our paper complements their results by providing suggestive evidence that although the government might be able to raise more revenue in historically centralized areas, the revenue raised may not necessarily translate into provision of public goods. Instead, our finding that people in the historically centralized areas are willing to pay taxes despite having low-quality public institutions may imply that they lack the necessary fiscal contract that would allow them to demand the government for better public goods.

Our paper also relates to the growing empirical studies on Africa that examine how individual characteristics, attitudes, and beliefs correlate with tax compliance norms (see for instance Ali et al, Reference Ali, Fjeldstad and Sjursen2014; Besley, Reference Besley2020; Jahnke and Weisser, Reference Jahnke and Weisser2019; McCulloch et al., Reference McCulloch, Moerenhout and Yang2021). The present paper contributes to this literature by looking at the role of history in shaping individual's tax compliance norms.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows; Section 2 presents the historical background of taxation in Uganda. Section 3 introduces the data and presents the economic specifications. Section 4 reports the results and section 5 concludes.

2. Historical background

In pre-colonial times, Uganda was characterized by considerable variety of institutions within the current national borders. The South and the West of the country were the territories of the centralized kingdoms of Buganda, Bunyoro, Toro, and Ankole (Doornbos, Reference Doornbos1975; Karugire, Reference Karugire1996). In the eastern and northern parts of Uganda, people were organized in a multitude of small and fragmented political entities, often lacking any political centralized administrative unit above the local village (Gennaioli and Rainer, Reference Gennaioli and Rainer2007). These include Bugisu, Teso, and the Karamoja in the East, and Acholi and Lango in the North (Kjær, Reference Kjær2009; Muhangi, Reference Muhangi2015).

The centralized polities had a strong bureaucracy with a hierarchical governance structure starting from the king and going all the way down to the village chief. The main tasks of the village chiefs were to collect taxes and mobilize the king's subjects for community services (Ray, Reference Ray1991). Taxes were collected from the locals as well as tributes from the subjects of the tributary states. Generally, women and unmarried men were exempted from paying taxes. The most extensive documentation of taxation in pre-colonial Uganda refers to the Buganda Kingdom, which was one of the most powerful kingdoms in Central and East Africa by the second part of the 18th century (Kiwanuka, Reference Kiwanuka1971). Initially, there was not a fixed time for tax payment, and taxes were collected whenever the king deemed it necessary (Reid, Reference Reid2002). By the 19th century Buganda had developed a more systematic method of tax collection where taxes were levied twice a year. The tax collection was undertaken in a decentralized manner whereby the village chiefs implemented a census of almost every household to identify who owned what (ibid).

The kinds of taxes imposed on the people in Buganda can be divided into four (Reid, Reference Reid2002; Ssekamwa, Reference Ssekamwa1970). The first was a compulsory tax collected from each married man who owned a homestead in the form of bark-cloths and cowrie-shells. The second was a kind of excise duty extracted from men on food crops, cattle, goats, intoxicating drinks, and manufactures such as baskets and carpets. The third was a kind of customs duty levied on goods such as salt and iron tools bartered on the borders between Buganda and Bunyoro. The fourth was a levy paid as an exemption from participating in a war. The tax revenues were used for various purposes such as to sustain the armies, support the royal court, and cover the costs of frequent banquets and administration of newly conquered areas (Ssekamwa, Reference Ssekamwa1970). There was also an in-kind tax, where all able-bodied men were obliged to engage in public works such as making new roads and maintaining old ones without pay (Reid, Reference Reid2002). In other kingdoms, taxes were collected periodically by the village chiefs. For example, in Ankole taxes were collected on cattle (Roscoe, Reference Roscoe1923), and in Bunyoro, which was known for its salt production, an in-kind tax was collected on salt purchased (Good, Reference Good1972).

British rule in Uganda was characterized by a strong continuity of pre-colonial institutions of governance (Apter, Reference Apter1961; Pratt, Reference Pratt, Harlow and Chilver1965). The British colonizers maintained the pre-colonial hierarchical structure to administer the locals including collecting taxes (Pratt, Reference Pratt, Harlow and Chilver1965). Chiefs oversaw the collection of taxes and were able to retain a certain percentage of the tax revenue (Mamdani, Reference Mamdani1996). In exchange for their collaboration with the British colonial rule, chiefs gained more autonomy in terms of, for example, distributing rents and allocating land resources (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Fjeldstad and Shifa2020; Kjær, Reference Kjær2009).

Pre-colonial institutions remained relevant in Uganda long after independence (Englebert, Reference Englebert2002). Even if kingdoms were abolished in Uganda in 1966 and were split into smaller local government units following the 1986 civil war they continued being a fundamental building block of ethnic belonging and cohesion. Despite the government's continued effort after independence to separate politics from culture and ponder new laws to limit the activities of traditional leaders, ‘kings had proven durable and ‘history’ continued to hold out against ‘modernity’ – for many of the same reasons across the colonial and post-colonial periods, namely that they have flourished in the absence of an alternative political and cultural source of power’ (Reid, Reference Reid2017: 345). Furthermore, although chiefs no longer collect taxes, they continued to play an important role as gate keepers between the central government and the citizens by engaging in an array of apolitical activities such as environmental awareness, health and immunization, and education (Reid, Reference Reid2017).

3. Data and econometric specification

The primary dataset to measure pre-colonial centralization and a host of other ethnic-specific characteristics is obtained from Murdock's Ethnographic Atlas (Murdock, Reference Murdock1967). This dataset is combined with geo-referenced data on historical ethnic homelands from Murdock's (Reference Murdock1959) ethnolinguistic map. We merge the ethnic dataset with rounds 3–6 of the AB survey using village-level geographic data on the residence of respondents.

To measure pre-colonial centralization at the ethnic homeland level, we use Murdock's (Reference Murdock1967) ‘Jurisdictional Hierarchy Beyond the Local Community Level’ index that ranks the pre-colonial political complexity of ethnic homelands from 0 to 3. A rank of 0 indicates stateless societies, 1 captures politically less complex ethnic homeland such as those having petty chiefdoms, and 2 and 3 indicate ethnic homelands that are part of paramount chiefdoms and large states, respectively.

Following Gennaioli and Rainer (Reference Gennaioli and Rainer2007), we define pre-colonial centralization at the level of ethnic homelands as a binary indicator with a value of zero if it lacks any political organization beyond the local level or is organized as petty chiefdom and one if it is either a large chiefdom or was part of a large state (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ethnic homelands with pre-colonial centralized and non-centralized states.

Note: The gray ones are ethnic homelands that either had large chiefdoms or were part of a large state. The white ones are ethnic homelands that lacked any political organization beyond the local level.

Source: Authors' illustration based on Murdock's Ethnographic Atlas (Reference Murdock1967)

Our main dependent variable that measures tax compliance norm is obtained from the AB survey. We use an indirectly phrased question to capture tax compliance norm to avoid direct implication of ‘wrongdoing’ by the respondent. Respondents are asked to state whether they think it is (1) ‘not wrong at all’, (2) ‘wrong, but understandable’ or (3) ‘wrong and punishable’ for people not to pay taxes on their income. A binary indicator for tax compliance norm is constructed with a value of 1 if respondents choose statement (3) and 0 otherwise.

The correlation between pre-colonial centralization and individual's tax compliance norm is estimated using the following equation.

Y i,e is a dummy variable capturing tax compliance norm of individual i in the historic ethnic homeland … I e represents a binary index for pre-colonial centralization. Our coefficient of interest is β that indicates the relationship between pre-colonial centralization and contemporary tax compliance norm. The vector X denotes set of individual controls, geographic features of ethnic homelands, ethnic-level historical incidents, and village-level development indicators. Appendix A.1 provides the description of the variables and the sources.

The individual-level controls that are obtained from the AB survey include age and age squared, an indicator for gender, indicator for whether the respondent resides in an urban center, employment status (employed or unemployed), years of education, indicator for wealth, and respondent's religion fixed effects.

Geographic indicators at the level of ethnic homelands include distance of the centroid of each ethnic homeland from the nearest coast, the capital city, and the national border. We also include mean elevation, area under water, land area, and an index for soil suitability for agriculture of each ethnic homeland. Geographic features, in general, are shown to matter for local development and can affect the quality of local institutions (Nunn and Puga, Reference Nunn and Puga2012), which in turn can influence people's tax compliance norms. The distance from the nearest coast is intended to capture the effect of trade, including the slave trade, as well as the penetration of colonization. The distance to the national border captures the potentially lower level of development in border areas. The distance to the capital city accounts for within-country variation in state capacity. Most governments in Africa tend to favor areas close to capital cities in terms of fiscal transfers as well as service delivery (Brinkerhoff et al., Reference Brinkerhoff, Wetterberg and Wibbels2017).

We further control for various pre-colonial and colonial ethnicity-level variables. The first one is the intensity of exposure to the slave trade, which we calculate, following Nunn and Wantchekon (Reference Nunn and Wantchekon2011), as the total number of slaves exported from each ethnic homeland divided by the land size of the ethnic homeland. Exposure to the slave trade is likely to affect individual's perception about the quality of current institutions by eroding their trust toward leaders both at the national and local levels (ibid.). We also control for indicators of economic development and the level of complexity of social organization in pre-colonial societies. History suggests that agriculture, particularly banana cultivation, led to new settlement patterns and the emergence of strong states such as Buganda (Reid, Reference Reid2002). As an indicator of pre-colonial economic development, we use an index ranging from 0 to 4 that captures the extent of dependence of each ethnic homeland on agriculture. For pre-colonial social organization, we use an indicator variable for complex settlement with zero indicating nomadic and one indicating sedentary settlement. We further control for two indicator variables related to the period of colonization. The first variable is an indicator for whether a colonial railway station is available in the ethnic homeland to account for colonial investment in infrastructure (Dell and Olken, Reference Dell and Olken2020). The second is an indicator for whether a missionary station is available at the ethnic homeland. The availability of missionary stations may undermine the quality of local institutions by lowering trust (Okoye, Reference Okoye2021).

Variables that reflect respondent's ethnic composition and inter-ethnic relationships that are likely to affect tax compliance norms are also included in vector X. The first one is ethnic fractionalization, which is constructed at the district level using the sample of individuals in the AB survey (Nunn and Wantchekon, Reference Nunn and Wantchekon2011). Ethnic heterogeneity can lower tax compliance norms as citizens may be less willing to contribute to public goods if they think that the tax revenues are going to be shared with members of other ethnic groups (Li, Reference Li2010). We also control for the respondents' perception of how the state is treating their ethnic group relative to other ethnic groups. Individuals' perception that the state is treating certain groups preferentially over others may affect their level of trust toward their government and hence their tax compliance norms (McKerchar and Evans, Reference McKerchar and Evans2009). This variable is particularly important for Uganda, since the country has had heightened ethnic-centered tension in its post-independence history (Kasozi, Reference Kasozi1994). From the AB survey, we construct a binary indicator with a value of 1 if individuals perceive that the government treats their ethnic group unfairly often or all the time and zero if they responded never or sometimes.

We also include a local-level variable that captures the respondents' level of satisfaction with the central government's provision of local services. In the AB survey, individuals were asked to rank their level of satisfaction with basic services such as health, education, water, and road maintenance ranging from ‘very badly’ to ‘very well’. Based on these responses, we generate an index using factor analysis. The higher the value, the more satisfied an individual is with the government's provision of local services. We further control for light density at night to capture the effect of current development at the village level (Michalopoulos and Papaioannou, Reference Michalopoulos and Papaioannou2013).

Table 1 provides summary statistics of the dependent variable and the controls, with their mean comparison by level of centralization. The table shows that a slightly higher share of respondents in historically centralized homelands believe that not paying taxes is wrong and punishable (40%) than those in the non-centralized homelands (37%), the difference being significant at 10%.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Note: This table reports means and standard deviations of the variables by level of centralization. Standard deviations are in parentheses. The last column reports the p-value for the mean comparison test. Except for the variables Male, Age, and Elevation, the mean comparison of all the other variables is significantly different between the centralized and non-centralized areas.

4. Results

4.1 Benchmark results

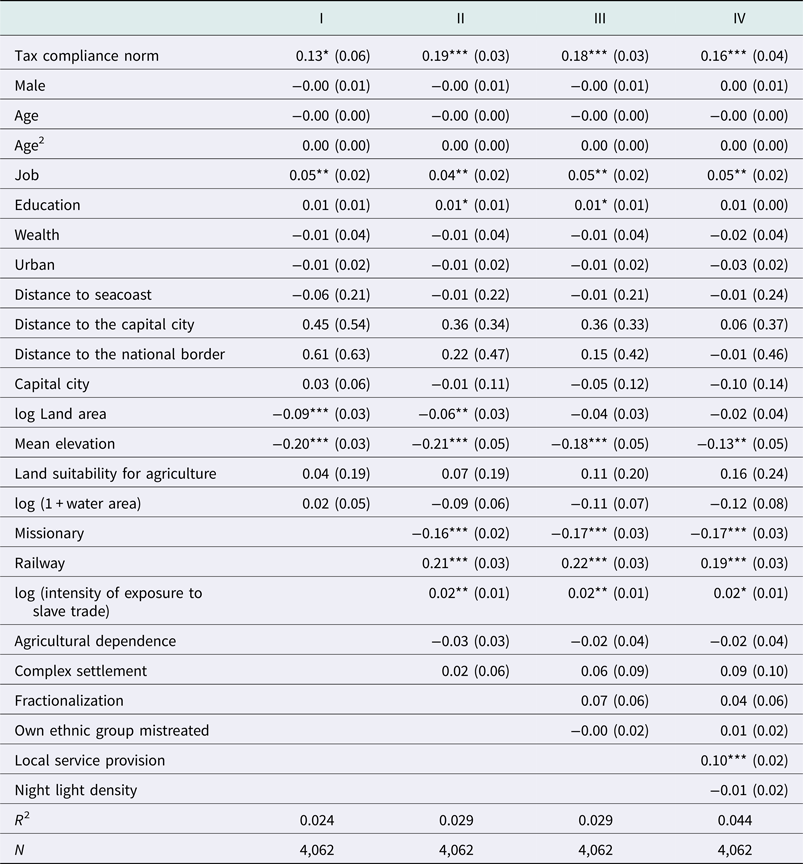

Table 2 reports the correlation between pre-colonial centralization and individual's tax compliance norm using a linear probability model. The standard errors are in parenthesis and clustered at the ethnicity level. All specifications include individual-level controls, geographic features of ethnic homelands, and a survey-round fixed effect. The results show that pre-colonial centralization is associated with a higher tax compliance norm and is significant at 1% level in all the specifications.Footnote 2

Table 2. Pre-colonial centralization and tax compliance norm: benchmark results

Note: The dependent variable is a binary indicator for tax compliance norms. All columns include individual-level controls, geographic indicators of ethnic homelands as well as a survey-round fixed effect. The individual-level controls include age and age squared, an indicator for gender, an indicator of whether the respondent resides in an urban center, employment status, years of education, an index for wealth, and fixed effects for the respondents' religion. Geographic indicators include mean elevation, area covered with water, land area, an index for land suitability for agriculture, the distance of the centroid of each ethnic homeland from the nearest seacoast, the capital city, and the national border. Column I controls for a set of historical ethnic homeland variables that include exposure to slave trade, indicator of pre-colonial economic development, pre-colonial social organization, colonial investment in infrastructure, and missionary activity. Column II controls for ethnic fractionalization and individual's perception about the treatment of their ethnic group by the state. Column III includes an index for an individual's perception of the quality of local service provision and night light density. The standard errors are in parenthesis, clustered at the ethnicity level. *** indicates statistical significance at 1% level.

Results on the other control variables reported in Appendix Table A1 indicate that individuals that have jobs and are more satisfied with the government's provision of basic services have higher tax compliance norms. Among the geographic features, only mean elevation of the ethnic homelands is significant and is correlated negatively with tax compliance norm. High elevation areas are characterized by harsh weather, rugged terrain, and steep slopes that can make them less accessible by the state (Jimenez-Ayora and Ulubaşoğlu, Reference Jimenez-Ayora and Ulubaşoğlu2015). Existence of missionary stations is correlated negatively with tax compliance norm, while availability of colonial railways is associated positively with tax compliance norm. Higher intensity of exposure to slave trade is associated positively with tax compliance norm. This may be because slave trade was prevalent in the centralized parts of Uganda during pre-colonial times (Medard and Doyle, Reference Medard and Doyle2007).

4.2 Regression discontinuity analysis on contiguous ethnic homelands

To address the bias in our regression result that may arise from unobservable local features, we use the geographic information system available in the data and use RDA to identify the average effects on individuals that live close to the border of contiguous ethnic homelands with different levels of pre-colonial centralization.

First, we identify adjacent ethnic homelands with varying degrees of pre-colonial centralization. Then, we estimate the difference in tax compliance norms between contiguous ethnic homelands using the following econometric specification:

Y i.e(j) is an indicator variable capturing the tax compliance norm of individual i, in the historic homeland e that is adjacent to the ethnic homeland j, where ethnic homelands j, and j differ in their degree of pre-colonial centralization. The coefficient β now represents differences in tax compliance norms between contiguous ethnic homelands with different levels of pre-colonial centralization (e.g. Buganda and Lango, as in Figure 1).

4.2.1 Validation

For our identification strategy of the RDA to be valid, we check that there are no systematic differences in local observable factors across the borders (Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2008). We do this by looking at the association between pre-colonial centralization and location specific factors (distances to the capital city, the coast, and the national border) and geography (land area, elevation, area covered by water, and soil quality for agriculture) among adjacent ethnicities. Since we only have few adjacent ethnic homelands, we do the analysis at a pixel level to get more observations. The unit of analysis is a pixel of 0.125 × 0.125 decimal degree, which is around 12 × 12 km. We find no statistically significant difference in location and geographic attributes, suggesting that by focusing on adjacent ethnic homelands we minimize biases that may arise from local observable factors.Footnote 3

4.2.2 Results

Table 3 presents the RDA results from individuals within 75 km of the borders of the contiguous ethnic homelands. We did the analysis on 50 and 100 km of the borders and obtained similar results. We include individual-level controls, geographic features of ethnic homelands, round fixed effects, border fixed effects of the contiguous ethnic homelands, and the linear distance from the borders in all the specifications. The standard errors are in parenthesis and clustered at the ethnicity level. The correlation between pre-colonial centralization and tax compliance norm remains positive and significant in all columns.

Table 3. RDA results on contiguous ethnic homelands

Note: The dependent variable is a binary indicator for tax compliance norm. All columns include individual-level controls, geographic features of ethnic homelands, round fixed effects, border fixed effects, and the linear distance from the borders. The standard errors are in parenthesis, clustered at the ethnicity level. *** indicates statistical significance at 1% level.

Figure 2 presents a visual display of tax compliance norm as one crosses the historically centralized and non-centralized borders in our sample. The dots mark local averages (in 5 km bins) of the outcome variable (tax compliance norm) for respondents within 75 km of the borders. The fitted line represents the correlation between distance to the borders of the contiguous ethnic homelands and tax compliance norm and is obtained from the regression of the dependent variable on a second-degree polynomial function of distance to the borders. The patterns in the figure mimic the findings reported in Table 3. The share of respondents with tax compliant norm increases on the historically centralized side of the border (to the right of the x-axis center point).

Figure 2. Tax compliance norm across the centralized-non centralized border.

Note: The figure shows the share of respondents with tax compliant norm by distance (in km) to the border. Negative (resp. positive) values represent distance from the border into non-centralized (resp. centralized) territories.

We cannot be certain if the correlation between pre-colonial centralization and tax compliance is due to cultural norms of individuals or location-specific factors where they live. To identify which of these could be driving our results, we use information from the AB survey and include individual ethnic identity fixed effects in our econometric specification. Including ethnic fixed effects helps capture ethnic-specific factors, such as cultural norms, that may affect individual's tax compliance. The coefficient of pre-colonial centralization after including ethnic fixed effects indicates the average effect coming from the location.

Table 4 reports the RDA result for individuals within 75 km of the borders. The coefficients on pre-colonial centralization in Table 4 increase substantially in all the specifications, compared to those reported in Table 3 where we did not control for ethnic fixed effects.Footnote 4 This suggests that individuals' tax compliance norm is largely driven by factors specific to the location that they live in rather than the cultural norm of their ancestors.

Table 4. RDA results using individual ethnicity fixed effects

Note: The dependent variable is a binary indicator for tax compliance norm. All columns include individual-level controls, geographic indicators of ethnic homelands, survey-round fixed effects, individual ethnicity fixed effects, border fixed effects, and the linear distance from the borders. The standard errors are in parenthesis, clustered at the ethnicity level. ** and *** indicate statistical significance at 5 and 1% level, respectively.

We are able to identify statistically significant results after including ethnicity fixed effects because a sufficient share of respondents reside outside their ancestral homelands. While in general 18% of Ugandans live outside of their ancestral homelands, the share increases to 30% for those within 50 km of contiguous ethnic homelands with different levels of centralization. Historical accounts also confirm this pattern. By 1948, as much as 34% of the population living within the borders of the Buganda Kingdom were immigrants (Peterson, Reference Peterson2012: 79).

4.3 Mechanisms

We examine the following mechanisms to explain the positive association between pre-colonial centralization and tax compliance norms; persistence in citizens' belief about the need to obey authority (Heldring, Reference Heldring2021; Lowes et al., Reference Lowes, Nunn, Robinson and Weigel2017), the quality of institutions (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001), and social cohesion (Grosjean, Reference Grosjean2011).

4.3.1 Obedience to authority

States in centralized polities in pre-colonial times had organized force to uphold authority and ‘can uniformly apply policies throughout a given territory’ such as extract labor, enforce the law, and demand taxes (Schraeder, Reference Schraeder2004: 29, 30). We hypothesize that the legacy of such a system of governance may lead people in historically centralized parts to become more obedient to authority, which in turn can shape their compliance norm to general rules, including paying taxes.

To test this mechanism, we use questions from the AB survey that capture the respondents' belief in the need to follow rules from various government bodies. Respondents were asked regarding their agreement with the following statement, ‘The tax authority always have the right to make people pay taxes’, ‘The courts have the right to make decisions that people always have to abide by’, and ‘The police always have the right to make people obey the law’. Individuals can respond to each of these statements by choosing strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, and strongly agree. We construct a binary indicator with a value of one if respondents either agree or strongly agree with the authority of at least two of the government bodies and zero otherwise. We then test its correlation with pre-colonial centralization.

We further check the correlation between pre-colonial centralization and individual's belief about the need to obey the government in power. The AB survey asks respondents about their agreement to either of the following statements: (1) It is important to obey the government in power, no matter who you voted for, and (2) It is not necessary to obey the laws of a government that you did not vote for. We construct a binary indicator with a value of one if respondents agree with statement (1), and zero if they agree with statement (2).

Table 5 reports the RDA results for individuals within 75 km of the borders. Panels (a) and (b) show results for belief in the need to obey authority and the government in power, respectively. The coefficients for pre-colonial centralization in Table 5 are significant in all the specifications of both panels. These results that are obtained after controlling for individual ethnicity fixed effects confirm the importance of location-specific factors in explaining compliance. Places with a long history of state may use their experience with large-scale administration to create a more effective government (Chanda and Putterman, Reference Chanda, Putterman, Lange and Rueschemeyer2005), which can ‘support the development of attitudes consistent with bureaucratic discipline and hierarchical control’ (Bockstette et al., Reference Bockstette, Chanda and Putterman2002: 348).

Table 5. Pre-colonial centralization and obedience to authority and the government in power

Note: The dependent variables in panels (a) and (b) are binary indicators for individual's belief in obedience to authority and the government in power, respectively. All columns include individual-level controls, geographic indicators of ethnic homelands, survey-round fixed effects, individual ethnicity fixed effects, border fixed effects, and the linear distance from the borders. The standard errors are in parenthesis, clustered at the ethnicity level. *** indicates statistical significance at 1% level.

Figure 3 shows an increase in the share of individuals who believe in the need to obey authority and the government in power, as one moves from the historically non-centralized to the centralized side of the border.

Figure 3. Obedience to authority and government in power across the centralized-non centralized border.

Note: The figures show the share of respondents who believe in the need to obey authority and government in power by distance (in km) to non-centralized and centralized borders. Negative (resp. positive) values represent distance from the border into non-centralized (resp. centralized) territories.

4.3.2 Trust in institutions

Although people in pre-colonial times could be paying taxes because of administrative imposition from the authority, compliance could not rely on coercion alone. Furthermore, pre-colonial states, unlike present-day states, could not provide as much public goods to their people (Chlouba et al., Reference Chlouba, Smith and Wagner2022), which has been argued to help increase compliance (Tilly, Reference Tilly1990). There could, therefore, be other ways that pre-colonial states were using to encourage ‘quasi-voluntary compliance’. One way was through the accountability of leaders. The political structure in pre-colonial centralized societies was shared among numerous hierarchies of institutions that enabled checks and balance of administrative power (Englebert, Reference Englebert2000; Lloyd, Reference Lloyd1960). Various socio-religious taboos were also used to minimize the rulers' tendency to use their power in excess (Ayandele, Reference Ayandele, Crowder and Ikime1970). The persistence of accountable leaders in historically centralized areas may, thus, affect the contemporary fiscal contract between citizens and the government by strengthening institutional trust (Levi, Reference Levi1988). We test for this mechanism by looking at the relationship between pre-colonial centralization and individual's trust toward the central government and various institutions.

In the AB survey, individuals were asked to indicate how much they trust the central government (the ruling party) as well as various public institutions namely the police, the court, and the tax authority by choosing one of the followings; Not at all, Just a little, Somewhat, or A lot. We construct a binary indicator for trust in the central government and each of the institutions by giving a value of 1 if respondents chose Somewhat or A lot, and a zero if they chose Not at all or Just a little.

Table 6 reports the RDA results for respondents within 75 km of the borders after accounting for ethnicity fixed effects. The results show that people in the centralized parts of the borders are less trusting of the state, the police, and the tax authority. We do not find significant results for trust in the court. Figure 4 further shows that the share of respondents who trust the central government, the police, and the tax authority decreases in the historically centralized part of the border.

Table 6. Pre-colonial centralization and trust in the central government and various institutions

Note: The dependent variables in panels (a)–(d) are binary indicators for trust in the central government, the police, the court, and the tax authority, respectively. All columns include individual-level controls, geographic indicators of ethnic homelands, survey-round fixed effects, individual ethnicity fixed effects, border fixed effects, and the linear distance from the borders. The standard errors are in parenthesis, clustered at the ethnicity level. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at 10, 5, and 1% level, respectively.

Figure 4. Trust in the central government and institutions across the centralized-non centralized border.

Note: The figures show the share of respondents who trust the central government and various institutions by distance (in km) to the border. Negative (resp. positive) values represent distance from the border into non-centralized (resp. centralized) territories.

The results suggest that although individuals in the historically centralized parts are more obedient to authority, it is not necessarily based on a trusting relationship. The British colonial administration that gave greater autonomy to leaders in governing the locals may have disrupted the pre-colonial mechanisms of accountability (Mamdani, Reference Mamdani1996). The aggressive stance of the post-independence regime against the centralized parts by abolishing kingdoms may have also contributed to mistrust in the state and state-related institutions (Reid, Reference Reid2017).

4.3.3 Social cohesion

Pre-colonial centralized states in Africa were expanding their territories by concurring new communities (clans). The expanding kingdoms were using different ways to bring together individuals with different backgrounds and make them acknowledge authority and comply with rules. For example, they strengthened proto-nationalistic beliefs and social cohesion among the different clans by means of religion and political rituals (Chlouba et al., Reference Chlouba, Smith and Wagner2022). This helped increase solidarity among the different clans and created a cohesive polity (Turchin, Reference Turchin2016). A strong social cohesion in pre-colonial centralized areas further contributed to a higher interpersonal trust (Kjær, Reference Kjær2009). Social cohesion in general is shown to affect individual's tax compliance norms (Torgler, Reference Torgler2002). Next, we test if social cohesion indicated by nationalistic beliefs and interpersonal trust has persisted in the historically centralized parts of Uganda.

Nationalistic belief could be Uganda-wide nationalism, or nationalism that serves the interest of a specific group, for example, the Kiganda nationalism in Buganda (Green, Reference Green2010). We hypothesize that the legacy of the second kind of nationalism, which we call ethnic-centered nationalism, could be higher in pre-colonial centralized Uganda than the country-wide nationalism. We use a question from the AB survey where respondents were asked to reflect their sense of ethnic-centered (relative to Uganda-wide) identity by choosing the following: (1) only ethnic; (2) more ethnic than Ugandan; (3) equally ethnic and Ugandan; (4) more Ugandan than ethnic; or (5) only Ugandan. We construct a binary indicator for ethnic-centered nationalism that equals 0 if the respondent chooses either options (4) or (5) and 1 otherwise.

To measure interpersonal trust, we use the following question from the AB survey. Generally speaking, would you say that (1) most people can be trusted or (0) you must be very careful in dealing with people? We construct a binary indicator with a value of 1 if respondents chose (1) and zero, otherwise.

Table 7 reports the RDA results for ethnic-centered nationalism in panel (a) and interpersonal trust in panel (b) for individuals within 75 km of the borders after accounting for ethnicity fixed effects. We do not find a significant result for ethnic-centered nationalism; however, pre-colonial centralization is significantly correlated with higher level of interpersonal trust. Figure 5 depicts that interpersonal trust is higher in the historically centralized parts of the border.

Table 7. Pre-colonial centralization and sense of nationhood and interpersonal trust

Note: The dependent variable in panel (a) is a binary indicator for individual's sense of ethnic-centered nationalism and in panel (b) is a binary indicator for trust in other people. All columns include individual-level controls, geographic indicators of ethnic homelands, survey-round fixed effects, individual ethnicity fixed effects, border fixed effects of the contiguous ethnic homelands, and the linear distance from the borders. The standard errors are in parenthesis, clustered at the ethnicity level. *** indicates statistical significance with standard errors at 1% level.

Figure 5. Ethnic-centered nationalism and interpersonal trust across the centralized-non centralized border.

Note: The figures show the share of respondents who have a strong sense of ethnic-centered nationhood and interpersonal trust by distance (in km) to non-centralized and centralized borders. Negative (resp. positive) values represent distance from the border into non-centralized (resp. centralized) territories.

4.4 Robustness checks by excluding Acholi and Lango

The post-independence history of Uganda was characterized by widespread ‘victimization’ based on ethnicity (Kasozi, Reference Kasozi1994). Particularly, the historically less centralized Acholi and Langi people were targeted in the ethnic politics of the post-independence Uganda (ibid). During his first presidency (1966–71), Milton Obote favored the Langi and Acholi in his administration of the army. Obote's reign ended in 1971 with a military coup led by Idi Amin. Amin committed ethnically targeted massacres on groups that supported Obote's regime, especially the Langi and Acholi (Reid, Reference Reid2017). Amin was overthrown in 1979 following an invasion by Tanzania, which marked the returning to power of Obote for the second time (1980–85). Obote followed the same trend as in his first presidency by recruiting people from the North in the army (Kasozi, Reference Kasozi1994). However, Obote's second period in power was met with factions between Acholi and Langi (Lucima, Reference Lucima2022). An increasing number of Acholi soldiers felt left out by Obote, who continued to fill his leadership by Langi (Schulz, Reference Schulz2021). The infighting between the Langi and Acholi led to the dismantling of the Obote's regime in 1985 and brought Tito Okello, from Acholi, as interim president. In 1986, Okello was overthrown by the National Resistance Army (NRA) under the leadership of Yoweri Museveni. The NRA, who justified human rights abuses in the name of crushing rebellion, committed many atrocities against the people of Acholi (Lucima, Reference Lucima2022). This led to an insurgency by the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) that initially had a popular support from the Acholi. However, this support began to dwindle, and in return the Acholi became the victims of mass killing and abductions by the LRA ‘in part as retaliation for not supporting the insurgency or for allegedly assisting the enemy – the Ugandan government’ (Schulz, Reference Schulz2021: 53). Overall, the civil war between the NRA and LRA that lasted for over two decades resulted in widespread atrocities against civilians in the Northern parts of Uganda.

The post-independence victimization of civilians from the North, particularly of the Acholi, may bias our results. For example, the lower tax compliance in the less centralized areas could be due to the post-independence ethnic-centered politics that has affected these groups. Although the individual ethnicity fixed effects that we controlled for in our econometric specification may help account for such bias, we further do a robustness check by excluding the Lango and Acholi homelands from our analysis. The RDA in the previous sections already excluded most of the less-centralized ethnic homelands in the North because they do not have neighboring centralized homelands to compare them with. By dropping Lango and Acholi in our current analysis, we also exclude neighboring centralized homelands of Buganda and parts of Bunyoro that is bordering Acholi.Footnote 5

Tables 8 and 9 report the RDA results on tax compliance norm and the mechanisms checks, respectively. The results in both tables account for ethnicity fixed effects and are estimated for individuals within 75 km of the borders. The results on tax compliance norm in Table 8 remain positive and significant in all the specifications. The mechanism checks in Table 9 show that trust in the court becomes negative but remains statistically insignificant. The result on ethnic-centered nationhood becomes positive and significant. All the other results remain the same.

Table 8. Pre-colonial centralization and tax compliance norms

Note: The dependent variable is a binary indicator for tax compliance norm. All columns include individual-level controls, geographic indicators of ethnic homelands, survey-round fixed effects, individual ethnicity fixed effects, border fixed effects of the contiguous ethnic homelands, and the linear distance from the borders. The standard errors are reported in parenthesis, clustered at the ethnicity level. *** indicates statistical significance with standard errors at 1% level.

Table 9. Mechanisms

Note: All columns include individual-level controls, geographic indicators of ethnic homelands, survey-round fixed effects, individual ethnicity fixed effects, border fixed effects of the contiguous ethnic homelands, and the linear distance from the borders. The standard errors are reported in parenthesis, clustered at the ethnicity level. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance with standard errors at 10, 5, and 1% level, respectively.

Although the above robustness checks may help address the bias that may arise from the targeted ethnic politics of the post-independence Uganda, the organization structure of the pre-colonial ethnic homelands was not kept intact following the 1986 civil war that led to the splitting of the kingdoms into smaller local government units. However, although the kingdoms were decentralized at the sub-national units, they continue being a fundamental building block of ethnic belonging and cohesion. Apuuli wrote in the preface to his Reference Apuuli1994 book on Bunyoro-Kitara that ‘The Kingdom which was declared dead in 1967 in actual fact never died. The enthusiasm with which the people greeted NRM government's decision to allow the people who once had kingdoms to revive them if they so wished is testimony enough’. For this reason, we believe that our findings hold and that the mechanisms work despite the post-independence decentralization reforms.

5. Conclusion

In this paper we have examined the legacy of pre-colonial centralization on tax compliance norms of citizens in contemporary Uganda. Using a RDA on neighboring ethnic homelands with different levels of pre-colonial centralization, we find that pre-colonial centralization is positively correlated with higher tax compliance norm. The result is explained by the legacy of the state's capacity in upholding authority and a strong social cohesion through higher interpersonal trust but not through trust in the central government and public institutions.

The results suggest that even though people in historically centralized parts of Uganda have mistrust toward the central government and public institutions, they may be willing to follow rules and pay taxes when they live in a setting with higher interpersonal trust. Our finding is similar to a study by Kjær (Reference Kjær2009), who exhibits in the case study of a historically centralized district in Uganda that ‘mistrust in taxation authorities can co-exist with a relatively high level of generalized trust’ (p. 237). Nonetheless, authoritarian leadership that is solely based on coercion without legitimate institutions would end up generating less tax revenue (Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Gangl, Kirchler and Stark2014). Social and economic policies to increase trust in public institutions can therefore help further increase tax compliance in Uganda. However, Reid (Reference Reid2017: 344) argues that the post-independent governments' continued effort to separate people's pre-colonial roots from politics in Uganda ‘was symptomatic of an age in which the modern state was not entirely to be trusted – if at all’. The success of policies to improve trust in public institutions will, therefore, depend on the leaders' effort to acknowledge the past (ibid.).

Our focus on pre-colonial legacies contributes to a growing understanding of why the pre-colonial past continues to shape the present. Though Uganda offers unique experiences, the empirical patterns we document may have broader empirical traction for other countries in Africa with centralized pre-colonial systems. More research is needed to examine the legacies of pre-colonial centralization in other African countries that had a history of strong early states.

Our study demonstrates that social norms affect tax compliance behavior and that social norms are affected by group heterogeneity shaped by history. Measures of tax morale or intrinsic motivations have been shown to have real effects on behavior, and attitudes toward tax evasion are found to be influenced by the social environment in which people live, reflected in their trust in government and institutions, and the attitudes of their neighbors (Alm, Reference Alm2019; Alm and Kasper, Reference Alm and Kasper2022). Yet, there has been little research on within-country differences in tax compliance behavior in general, and on the role of social norms and trust in shaping tax compliance behavior in developing countries in particular. More in-depth country-level analysis is required.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to J. Pirttilä, A. Savoia, K. Sen, I.H. Sjursen, and the editor and four anonymous referees of this journal for valuable comments on drafts. We thank participants at the CMI TaxCapDev-webinar (February 2021) and the UNU-WIDER workshop ‘Fiscal states – the origins and development implications’ (June 2021) for constructive comments on earlier versions of this paper. The paper was prepared with financial support from the Research Council of Norway (302685/H30 and 322461) and the UNU-WIDER program on ‘Domestic Revenue Mobilization’ funded by Norad. Points of view and possible errors are entirely our responsibility.

Appendixes

A.1. Variables and data sources

Variables from Afrobarometer data

All the Afrobarometer data are downloaded from the official Afrobarometer website: http://www.afrobarometer.org/data/merged-data. The survey rounds are reported below.

– Individual-level variables (male, employment, age, education, urban, religion, wealth): rounds 3, 4, 5, 6.

– Individual's satisfaction with local service provision by the state: rounds 3, 4, 5, 6.

– Own-ethnic group mistreated: rounds 3, 4, 5, 6.

– Tax compliance norm: rounds 5 and 6

– Obedience to authority: rounds 4, 5, 6

– Obedience to government in power: rounds 5 and 6

– Trust in the central government, the police, and the court: rounds 3, 4, 5, 6

– Trust in the tax authority: rounds 5 and 6

– Sense of ethnic-centered nationhood: rounds 3, 4, 5, 6

– Interpersonal trust: rounds 3 and 5

Pre-colonial and colonial ethnicity-level variables

– Historical homelands of ethnic groups. Obtained from the digital version of Murdock's (Reference Murdock1959) ethnolinguistic map from Nunn and Wantchekon (Reference Nunn and Wantchekon2011).

– Agriculture dependence: 0–4 scale reflecting the type of agriculture; 0 is for ‘no agriculture’; 1 is ‘causal agriculture’; 2 is ‘extensive or shifting agriculture’; 3 is ‘intensive agriculture’; and 4 is ‘intensive irrigated agriculture.’ Source: Murdock (Reference Murdock1967).

– Complex settlements: indicator that equals 1 for ethnicities living in compact, permanent, or complex settlements, and zero otherwise. Source: Murdock (Reference Murdock1967).

– Intensity of exposure to the slave trade: calculated as the total number of slaves exported from each ethnic homeland divided by the size of the land area of the ethnic homeland. Source: Nunn and Wantchekon (Reference Nunn and Wantchekon2011).

– Missionary activity indicator. A dummy variable for whether (or not) a missionary station is available at the ethnic homeland. Source: Nunn and Wantchekon (Reference Nunn and Wantchekon2011).

– Railway indicator. A dummy variable for whether (or not) there was a colonial railway station within the ethnic homeland. Source: Nunn and Wantchekon (Reference Nunn and Wantchekon2011).

Geographic indicators at the level of ethnic homelands

– Distance to coast. The distance between (the centroid of) each ethnic homeland and the nearest coast. Calculated using ArcGis.

– Distance to capital city. Distance between (the centroid of) each ethnic homeland and the capital city. Source: Calculated using ArcGis.

– Distance to the border: distance from (the centroid of) each ethnic group and the nearest border. Source: Calculated using ArcGis.

– Water area: total area covered by rivers or lakes in sq. km. Source: Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (Reference Michalopoulos and Papaioannou2013).

– Elevation: average elevation in km. Source: Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (Reference Michalopoulos and Papaioannou2013).

– Land area: source: computed for each ethnic homeland using the ‘shapefile’ from digital version of Murdock's (Reference Murdock1959) ethnolinguistic map.

– Soil suitability for agriculture: average land quality for cultivation. Source: Michalopoulos and Papaioannou (Reference Michalopoulos and Papaioannou2013).

– Light density. Average of night-time light density at the village level within the focal ethnic group's ethnic homeland. Source: https://ngdc.noaa.gov/eog/dmsp/download V4composites.html.

Table A1. Full results of the benchmark regression