“We must learn to think in continents.”

-Cecil RhodesFootnote 1Writing for his own newspaper, The Nation and Athenaeum on 24 May 1930, John Maynard Keynes cut into the maelstrom that had erupted in British politics around the ‘Briand Plan’. The visionary French foreign minister, Aristide Briand, had proposed to the League of Nations Assembly earlier that month that all twenty-seven European member-states, including Great Britain, join in a ‘federal bond’.Footnote 2 He had in mind some kind of great political and economic union to secure the peace and prosperity of the war-wearied continent. The proposal provoked a flurry of excitement and controversy: nowhere more so than in Britain. Most national newspapers, industry, and pro-empire think-tanks were adamant that Britain could not join a ‘United States of Europe’ if she wanted to preserve her Empire.Footnote 3 The British government ended up diplomatically declining Briand’s invitation.Footnote 4 The former Colonial and Dominions Secretary and stalwart imperialist, Leopold Amery (1873-1955) was one of the loudest voices raised in protest against British membership in Briand’s scheme.Footnote 5 Yet Amery had otherwise welcomed the proposal. As one of the earliest British backers of the Pan-European Union—founded in 1923—he was a great supporter of European federation.Footnote 6 Keynes had no time for Amery’s apparently confused reasoning. It seemed nonsensical that Amery should support European unification, while also insisting that Britain stay out to unite instead with the Empire. ‘The ideal of the Amerys’, Keynes concluded, baffled, ‘seems to be to divide the world into three or four hostile and competing federations’.Footnote 7

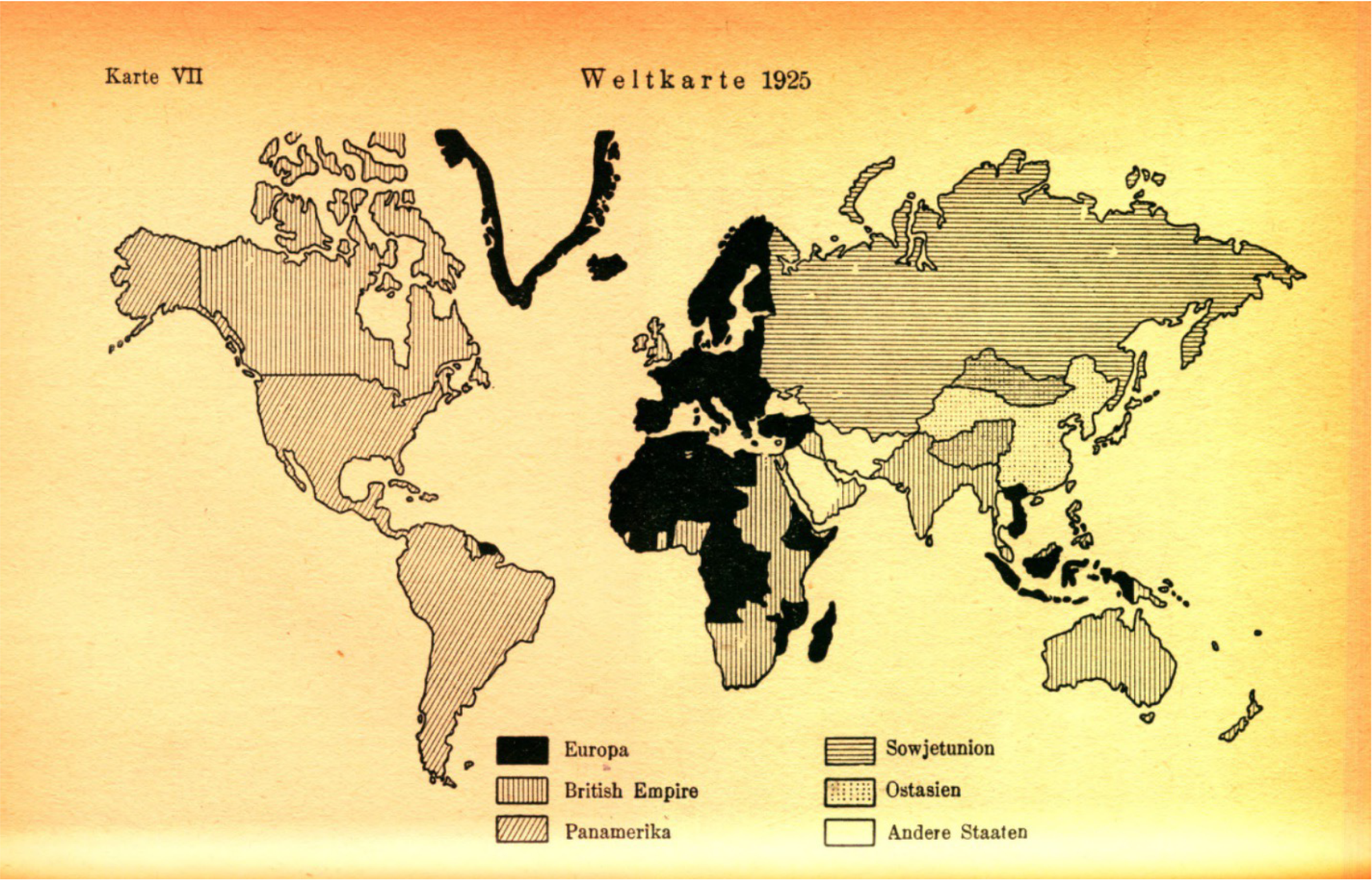

Keynes grasped Amery’s vision of international order: a world divided into massive federal blocks or super-states. But Amery was not alone in espousing such regionalist thinking, even as Keynes held it in contempt. Amery tracked with a strong current of British and European geopolitical thinking that originated in the rupture of the 1860s-70s when inter-state competition accelerated, intensified by the new technologies of the Second Industrial Revolution and rivalries over territorial expansion.Footnote 8 A new ideology of geopolitics equated the size of a state’s territory, population, home market, and store of natural resources with its power. Within this framework, the US and Russia—from the Tsarist Empire to the Soviet Union—were the new model states: the one a massive continental empire, the other a federal super-state. The British Empire would have to match this scale of organization and integration, if it had any hope of surviving and competing. The affinities between Amery’s thinking and that of Nazi theorists of Grossraumwirtschaft (‘greater-economic space’), are particularly striking—especially given the fact that they were never in conversation.Footnote 9 Amery was rather a disciple of the Habsburg Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi, founder of the Pan-Europa Union. They both envisioned a world map divided into five major regional blocks, as illustrated below (see Fig. 1): 1) Pan-Europe, to include European African colonies in a kind of ‘Monroe Doctrine for Europe’; 2) the Soviet Union; 3) the British Empire; 4) Pan-America (including the U.S. and Latin America); and 5) East Asia (dominated by Japan and China). Coudenhove-Kalergi and Amery argued that these blocks should be organized into ‘political-economic unions’: the fusion of a federal state with a common market unified by a customs union.Footnote 10

Figure 1: Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi’s World Bloc Map, ca. 1925.

Source: Richard N. Coudenhove-Kalergi, Europa Erwacht! (Paris; Vienna; Zürich: Paneuropa-Verlag, 1932), 68.

By the mid-1930s, most great powers seemed to be definitively following the regionalist trajectory. The cohort of revisionist states—the Soviet Union, Imperial Japan, Fascist Italy, and Nazi Germany—had all turned to projects of resource autonomy and bids for territorial expansion.Footnote 11 Ambitions for genuine world hegemony clearly lurked behind some of these apparently regionalist projects. But it was not just the illiberal states which abandoned internationalism and propelled the world into a second cataclysmic world war.Footnote 12 The historiography has focused on the revolt of the revisionist or ‘insurgent powers’ against the liberal international order established at Versailles in 1919. Undergirded by the League of Nations, this order was founded on the dual political commitment to national self-determination and state sovereignty, plus the reconstruction of free trade which states had abrogated in order to wage and resist blockade during the First World War.Footnote 13

This article argues that a revolt against liberal internationalism also rose up from within the traditional heartland of liberal internationalism itself: metropolitan Britain. Leo Amery was at the helm of this revolt, but he was not alone. His prolific writings demonstrate that he was one of the most stalwart and consistent British anti-internationalist imperialists: from the moment he joined Joseph Chamberlain’s campaign against free trade in 1903 all the way through the aftermath of the Second World War, when he continued to fight the rise of American internationalism. Historians have interpreted British imperialists’ embrace of internationalism after 1918 and ‘globalism’ in the 1940s as an important strategy for reinventing and maintaining the Empire in a new era of national-democratic politics. Liberal imperialists, such as Lord Robert Cecil who founded the British League of Nations Union, or Lionel Curtis’ Round Table movement—perhaps Britain’s leading imperial ‘think-tank’Footnote 14 —have taken centre stage in this story.Footnote 15 They believed that the Empire’s future—and world peace itself—lay with the League of Nations and the formation of some kind of Anglo-American alliance: a stepping-stone to world government. I show, however, that this was only one response to the interwar ‘crisis of empire’ provoked by bubbling anticolonialism nationalism, the rise of new geopolitical rivals, and longer-standing fears of imperial decline dating back to the 1870s.Footnote 16 Amery’s anti-free trade and anti-internationalist alternative was rooted in Conservative, rather than Liberal politics. It was also backed by important business and industries interests, particularly invested in protected imperial markets such as Alfred Mond (Lord Melchett) and Lord Harry McGowan of Imperial Chemical Industries, or the press baron Lord Beaverbrook.Footnote 17 Whereas Amery shared the liberal imperialists’ diagnosis, he could not have disagreed more with their solutions.

If British imperial regionalism, and Amery’s brand in particular, has gone largely unremarked by historians, this is not because it was an unsuccessful project. Imperial regionalism ultimately enjoyed much more practical policy success than imperial internationalism by the late 1930s, particularly when it came to the Empire’s economic development. At the Ottawa Conference in 1932, Britain fully abandoned its policy of unilateral free trade, founded on the Most-Favoured Nation clause. This came on the heels of the Bank of England’s decision to take the pound off the gold standard in September 1931, thereby creating the Sterling Area. Britain had, with both decisions, definitively turned inward from the international economy.Footnote 18 Suddenly left without an anchor-country, the world economy formally splintered into distinct monetary and trading blocks.Footnote 19 Ottawa was thus a major-turning point for interwar ‘deglobalization’. Nazi economists and theorists invoked it as a sign that Germany should turn to autarky.Footnote 20 By 1933, Britain’s foreign policy and diplomacy also increasingly turned towards the Empire—now partly rebranded as the Commonwealth—by retreating from its traditional leadership role within the League of Nations.Footnote 21 Even Keynes switched sides. He may have waxed grandiloquently in 1919 of the passing of pre-war economic internationalism, and critiqued Amery’s vision of a world in blocks in 1930.Footnote 22 But by 1933 he did a volte-face urging the adoption of ‘national [read imperial] self-sufficiency’.Footnote 23

British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin dismissed Amery in 1929, when he served as Colonial Secretary, for ‘not add[ing] a gram to the influence of government’.Footnote 24 Judging from the paucity of scholarship on Amery’s thought and work, historians seem to have unwittingly accepted Baldwin’s harsh assessment. Yet Amery was among the most creative and influential British politicians of the first half of the twentieth century. He was entangled in all the major imperial reform movements from the 1890s through the 1950s: from tariff reform to the creation of the Commonwealth, to colonial development all the way to Indian independence. He had been a founding member of Lord Milner’s Kindergarten while he reported on the South African War for The Times. During the First World War, he worked under Maurice Hankey, the powerful Cabinet Secretary, and compelled Lord Milner, then War Secretary, to propose the creation of an Imperial War Cabinet.Footnote 25 After the war, he became First Lord of the Admiralty, from 1922 to 1924, before reaching the height of his powers as Secretary for the Colonies and Dominions from 1924 until 1929. He returned to office to cap off his formal career as Secretary for India and Burma from 1940 to 1945.Footnote 26 If a cottage historiography on Amery has begun to grow, it has especially explored his complex reformist conservativism, staunch anti-appeasement, engagement in military imperial reform, and controversial support for Indian independence which earned him Churchill’s ire.Footnote 27 So far no one has examined his particular brand of anti-internationalist imperialism, nor grappled with its significance for the reorganization of the British Empire and world order in the first half of the twentieth century. This is the task of this article. By way of exploring Amery’s long-standing opposition to free trade, the League of Nations, and the US Open Door, the true extent of the interwar crisis of liberal internationalism and its fragile reconstruction after 1945 come fully into view. We uncover an alternative vision of federalist state-building and anti-regionalist internationalism that still continues to inspire alternatives to a liberal world order today.

Tariff reform and the neo-mercantilist revolt against free trade, 1870s-1930s

On the eve of the Ottawa Conference in July 1932, Amery recollected the jubilant elation he had felt when Sir Joseph Chamberlain launched the campaign for Tariff Reform three decades earlier, on 15 May, 1903.Footnote 28 Amery saw tariff reform and Imperial Preference as the ‘master-key’ to the problem of the Empire’s decline. He had become one of Chamberlain’s first followers: after the speech, Amery had set to work immediately, telephoning friends to assemble a core group of supporters who went on to form the Tariff Reform League a couple of weeks later.Footnote 29 He also spearheaded a pamphlet war in the columns of The Times against the most faithful defenders of free trade organized by the ‘Cobden Club’. Through to the end of his life, Amery’s opposition to free trade remained the most constant cause of his career.

Chamberlain’s Tariff Reform was a ‘neo-mercantilist’ programme.Footnote 30 Its followers thus believed that trade and all economic policy should service the increase of Britain’s geopolitical power. Amery and Chamberlain constantly repeated that ‘imperial strength’—nay even the very ‘survival’ of the Empire—required the rejection of free trade and the creation of an internal customs union.Footnote 31 One of Chamberlain’s first campaign speeches began with this existential angst: ‘Is Britain to be numbered among the decaying states?’Footnote 32 ‘I ask for preferential tariffs’, Chamberlain answered, ‘in order to keep the Empire together’.Footnote 33 Richard Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League, after all, had predicted that free trade would eventually dissolve the Empire.Footnote 34 Tariff Reformers operated with a Social-Darwinist and geopolitical mindset of state-power. The bigger the population, the larger and more self-sufficient the domestic market, then the ‘stronger’ the state would be in a geopolitical competition. Recent history, British imperial federalists believed, demonstrated that the small European Westphalian nation-state was quickly becoming obsolete: the future belonged to federal super-states. The emergence of the US as a newly unified and industrial powerhouse following the Civil War’s end in 1865, the confederation of Canada two years later, the federation of the German Reich in 1871, the federation of Australia in 1901, the Union of South Africa (which Amery had personally witnessed) in 1910, and the creation of the Soviet Union in 1917 provided the political background to this sweeping drama. British Tariff Reform consciously situated itself within this supposedly inexorable trajectory toward federalist state-building that was reconfiguring geopolitical competition.

Tariff Reform should be read, then, as part of a longer, trans-national, even trans-imperial neo-mercantilist revolt against the British-led liberal free trade order. The roots of this revolt were buried deep in the nineteenth century. Friedrich List’s German nationalist school of economics had formulated an especially explosive critique of British free trade and the laissez-faire dogmas of the Manchester School in the 1840s, when he published his National System of Political Economy (1841). In the 1820s, List had travelled to the US and met economists such as Henry Carey who promoted tariffs and trade protections—especially against British imports—to promote the development of the new republic. In his National System, List argued that Britain herself had first industrialized under protections then switched to impose free trade to keep her rivals from catching up: she ‘kicked away the ladder’. List’s theory had immense staying power, inspiring the protection of infant industries and economic nationalist development strategies in the US, Germany, and the Global South well into the late twentieth century.Footnote 35 Most immediately, List’s ideas inspired the gradual creation of a German imperial Zollverein—a customs union—which culminated in the Reich’s formal unification in 1871. Starting in the 1880s and 1890s, we can discern a general protectionist movement that rose up against the free trade order established by the 1860s Cobden Treaty System founded on the proliferation of the Most-Favoured Nation (MFN) clause.Footnote 36 Germany’s 1879 ‘iron and rye’ tariff on agricultural and industrial goods first set the ball rolling. The US, France, and Habsburg Austria enacted their own protectionist tariffs soon after, including the American McKinley Tariff of 1890 and the notorious French Méline Law which instituted a double agricultural tariff in 1892.Footnote 37 Even the British Empire—specifically only the White Dominions—took little steps towards protection before the First World War. Canada set things in motion by extending non-reciprocal preferential tariffs to the import of British goods in 1897. New Zealand and South Africa followed suit in 1903, then Australia in 1907: each granting between 5% to 15% for Empire products. Britain would not reciprocate any of these preferences, however, until after the First World War. Finally, the Finance Act of 1919 exempted the import of Empire goods into the mother country, which had become subject to the McKenna duties imposed during the war to raise vital revenue.Footnote 38 The rise of turn-of-the-century new-right, populist, and nationalist parties demanding protectionist policies across the European core from Paris to Vienna, in the US, China, and beyond, fed a more general malaise. Scholars have justly christened this moment the ‘fin-de-siècle crisis of liberalism’.Footnote 39 What this means should be clear: the liberal international economic order did not begin to collapse after 1918. Cracks in the free trade order had begun to appear decades before the Great War broke out—even within its anchor, the British Empire. This helps illuminate why efforts to revive free trade and the gold standard after 1918, under the aegis of the League’s numerous conferences, constantly ran into an impasse as tariffs and quotas continually rose.

Amery and Chamberlain consciously drew upon List’s critique of British classical economics to wage their battle against free trade between 1903-6. Many of List’s English disciples, including the national economists W. A. S. Hewins, W. J. Ashley and Halford Mackinder—the founder of British geopolitics—in fact joined Chamberlain’s campaign.Footnote 40 It is further telling that the Tariff Reform League framed its objective as the creation of a British ‘imperial Zollverein’.Footnote 41 This linguistic choice reflects how the German Empire’s federal state-building process served as their ideal model and guide. Amery and Chamberlain believed that German history illustrated how, ‘in all countries and at all times’, some modicum of commercial union always predated national political union.Footnote 42 Chamberlain roused one of his early audiences with this conviction:

I do not believe that the United States would have been the great empire it is but for commercial agreement between the several States which form it. I do not believe that Germany would have been a great and powerful empire but for the agreement between the several States that created it; and I do not believe that we shall be a powerful Empire, I do not believe that we shall be an Empire at all, unless we take similar steps.Footnote 43

That was the lesson. Economic union—via preferential tariffs and eventual customs union—had to precede closer political union if the British Empire was to become a truly unified regional block that could hold its own against all its other rival blocks.Footnote 44

There was one major roadblock: Britain’s adherence to the unilateral most-favoured nation trade rule. If Britain wanted to extend comprehensive preferential tariff rates to its Dominions and colonies, it had to extend these preferences to its other trade treaty partners. This has been the major innovation of the 1860 Cobden-Chevalier treaty signed between Britain and France, which became a template for a series of bilateral agreements signed between European states that decade. Britain had proceeded to extend to all countries the tariff reductions it had accorded to France under the 1860 agreement: here was the MFN rule put into practice. But it was unilateral. France, by contrast, was not required to do the same under the terms of the agreement. A flood of similar treaties followed, including a bilateral agreement between Prussia and France in 1862, embedding MFN rights, followed by a suite of others between Prussia and Austria, Italy, and Belgium.Footnote 45 Now we begin to grasp Amery’s rage at the free trade order. Amery believed that both the US and Germany—Britain’s chief geopolitical rivals in his eyes—had rapidly industrialized and challenged Britain’s manufacturing supremacy because they had embraced protectionism and rejected the MFN by the late nineteenth century. They had federated behind high external tariffs, thereby creating a massive ‘home market’ for their own industry. Amery and Chamberlain believed this had been the engine that had catapulted Germany and the US onto the world stage in the 1870s.Footnote 46 To remain competitive economically and geopolitically, the British Empire would have to follow a similar path. This had to start with full abandonment of unilateral free trade established in 1846. Only then could the whole empire become the wider integrated home market for metropolitan Britain, instead of the most developed consumer market for the whole world’s goods. Possible objections that neither the US nor Germany could be a model for the British Empire—it was dispersed across the seas, and not a contiguous continental land-mass—did not deter Amery in the least. He had faith in new transportation technologies. The Empire was built on its supremacy of the high seas. Maritime transport, he argued, could often be cheaper and more efficient than overland routes. Well-developed communications and transportation infrastructure could therefore forge a powerful unified block, even if in John Seeley’s words, the Empire, like Venice, had the sea for streets’.Footnote 47

The next step: imperial economic union in the 1920s-30s

Tariff Reform failed in the general election of 1906. Chamberlain’s Unionist Party, in coalition with the Conservatives had been decimated. The Liberal Party and free trade had won in a landslide, as the working-class masses rallied behind their clever campaign for the cheap ‘white loaf’.Footnote 48 But Amery did not give up the battle. After the war, he expanded the programme for tariff reform into a campaign for full-fledged imperial economic union—even imperial self-sufficiency—well into the 1920s and onwards. What is required for a full-fledged common market? Like the later architects of European unification after 1945, Amery foresaw that an imperial economic union required more than a simple customs union. During his tenure as head of the Dominion and Colonial Office, he invested in common infrastructure and development programmes to expand inter-imperial trade, migration, transportation, and communications. The 1923 Imperial Economic Conference, which Amery attended as First Lord of the Admiralty, had first set the ball going. Subsequently, the 1926 Imperial Conference, which Amery organized as the first Dominions and Colonial Secretary, recommended a long list of infrastructure projects: 1) the acceleration of ocean-going communications between Great Britain, India, Australia, and the rest of the Empire; 2) the opening of a new regular air-route between Cairo and Karachi and a second one connecting Sydney and Singapore, with the ultimate creation of a complete system of Empire Air routes in view; 3) more regular inter-imperial shipping lines; and 4) further development of the electric Pacific Cable, or ‘All-Red Line’, which connected Vancouver, to London to Cape Town, on to the coasts of Australia and New Zealand, passing through the British West Indies, Mauritius, and the southern-most tip of India.Footnote 49

During his tour of all the Dominions’ major cities in 1927-28, Amery continuously lamented the British Empire’s failure to mobilize its resources for its own inter-imperial development, especially compared to the United States. He lamented how:

We have been left behind to a large extent by our neighbours. The United States, in the last generation or two, have developed the resources of their great territory to a point which makes them to-day, as you here in Canada know so well, the greatest economic force in the world. They have more railways than all the world together; they consume in industry more horse-power, whether steam or electric or oil-driven, than the rest of the world. They have four times as many motor-cars as the rest of the world.Footnote 50

If the British Empire had four times the population of the U.S, and far more land, it was falling behind because its capacities remained ‘still largely undeveloped and unorganized’.Footnote 51 If the US had the largest domestic market in the world of 120 million consumers—envied by British and European federalists—the Empire together commanded a potential market over 400 million. Amery blamed this partly on the fact that, instead of trading internally as much as possible with its colonies and Dominions, Britain maintained a sizable trade with countries outside the Empire, whether in Europe or with the informal Empire (including the US and Argentina). In the 1920s, the Empire only accounted for an average of 27% Britain’s overseas trade. It had actually been slightly more during the war itself.Footnote 52 Amery thus raged on his tour to the Dominions about how the Empire ‘largely dissipates our energies, like the steam in a kettle, upon the world outside’, Amery raged.Footnote 53 The Social-Darwinist undertones to Amery’s angst are hard to miss. Amery, we must note, was not alone in this assessment. A host of imperialists agreed, including Winston Churchill, and the leading business magnate, Alfred Mond, founder and first CEO of the huge conglomerate Imperial Chemical Industries: Britain’s largest interwar company and its single biggest manufacturer.Footnote 54 Mond and his successor, Lord Harry McGowan—the next ICI Chairman starting in 1930—remained some of Amery’s most important backers for imperial economic union from the mid-1920s through the 1940s.

Amery first launched a coherent programme to promote inter-imperial migration. This disavowed one of Britain’s free trade traditions: the free circulation of people and emigrants. On the eve of becoming Colonial Secretary, he introduced the 1922 Empire Settlement Act to Parliament. Churchill seconded it.Footnote 55 The bill’s ultimate adoption meant that the government committed to paying the trans-oceanic passage for migrants leaving the British Isles to settle in the Dominions, in addition to financing their farm purchases.Footnote 56 Amery argued that promoting a more unified imperial labour market, and facilitating the movement of an unemployed ‘surplus’ to develop the ‘unpeopled lands’ of the overseas Dominions and Colonies would vitally strengthen the empire.Footnote 57 Here he betrays the classic terra nullius—virgin ‘empty land’—myth of British settler empire: indigenous inhabitants are entirely ignored. In the immediate term, Amery’s programme hoped to help alleviate the chronic mass-unemployment in Britain. In the longer-run, it might expand overseas consumer markets for British manufacturing thereby creating more jobs.Footnote 58 Most importantly, Amery believed that the Dominions’ population shortage and their underdeveloped economies constituted the most serious obstacle to a ‘materially and psychologically solid base’ for imperial union. Social-Darwinist, and almost racialized, language is implicit once more.Footnote 59 In front of almost every audience on his empire tour, Amery regretfully chronicled how the British Empire for decades had been indifferent to where its migrants relocated. This meant that ‘10,000,000 of our best blood left the shores of Britain to build up a great foreign nation, the United States’.Footnote 60 The 1922 Settlement Act and the Overseas Settlement Commission aimed to put an end to this free-trade in people. German imperialists had been airing very similar concerns since the 1880s-90s. The desire to put an end to the migration of millions of Germans to the United States, which strengthened a rival state, constituted one of the main arguments for German colonization. It would continue to drive imperial ambitions for Lebensraum and territorial expansion into the Nazi era.Footnote 61 The Colonial Development Act of 1929 was the capstone of Amery’s imperial infrastructure projects during his tenure as Colonial and Dominion Secretary. It was a historic piece of legislation: the world’s very first colonial development programme that financed the construction of public works, along with public health and education infrastructure throughout the empire. Amery later advocated for public investment in colonial development and scientific research once he became Secretary of India in 1940.Footnote 62

The Empire Marketing Board (EMB), established in 1926, remains the most memorable project Amery launched as head of the Dominions and Colonial Office. Yet it amounted to nothing more than a colourful advertising campaign. Its mission was to boost intra-imperial trade without the use of actual tariffs. Economic historians, hence, refer to it as ‘soft’ as opposed to ‘hard-trade policy’. Britain had still not reciprocated the preferences its exports enjoyed in Dominion markets. The EMB attempted to rectify this imbalance by encouraging some reciprocity, but only by nudging consumers through marketing campaigns and propaganda.Footnote 63 Flashy posters printed by the EMB thus encouraged Britons to ‘Buy Empire Goods’ at every opportunity (see Fig. 2). One famous campaign widely circulated a recipe instructing housewives how to make a fine ‘Empire Christmas Pudding’ with all ingredients purchased from the imperial realms. This was far from a project for total imperial economic union and a single imperial market. Unsurprisingly, the EMB ultimately failed to raise British imports significantly from the Empire.Footnote 64 It did, however, promote a more concrete common sense of imperial identity across Britain and the White Dominions, cemented in shared consumption habits.Footnote 65 The department was folded in 1933.

Figure 2: An Empire Marketing Board Advertising Poster, ca. 1927.

Source: McDonald Gill, ‘Highways of Empire Map’, Empire Marketing Board. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1927. UK National Archives (Kew), Colonial Office, CO 956/537.

Amery’s long battle for a comprehensive system of Imperial Preference culminated at Ottawa in Summer 1932. Tariff protections had been introduced in Britain since the war, eroding free trade. But it was done in a piecemeal fashion starting with the 1915 McKenna Duties, followed by the 1919 Finance Act and Safeguarding of Industries Acts of 1921 and 1925 which extended some tariffs to home manufacturing.Footnote 66 Finally, five months before the Imperial Economic Conference met in the Canadian capital, Britain introduced a general 10% tariff on all imports. A temporary exemption was granted to Empire products under the Import Duties Act. But the Dominions had long been clamoring for preferential reciprocity, particularly in agricultural but also manufacturing goods as they began to develop their own home industries. They had first extended preferences to British imports before the war, and in most cases, Britain had not returned the favour. Finally at Ottawa, Britain equalized the playing field. A whole web of bilateral reciprocal preference agreements—each lasting years—were signed between Britain and its seven Dominions: Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand, South Africa, India, and Southern Rhodesia. The Dominions further signed a series of reciprocal tariff agreements between themselves. The Ottawa agreements enshrined a very simple principle for the order of preference: local producers were entitled to first place in their home market, other Empire producers second, then foreign producers third.Footnote 67 Concretely, this meant Britain agreed to make permanent the initially temporary exemption to Empire goods from the Import Duties Act. The general tariff was then increased above 10% on foreign goodsFootnote 68 Further, Britain agreed to restrict its non-Empire imports of foodstuffs, particularly meat, and to impose new or higher duties on other non-Empire agricultural goods such as wheat, linseed, produce and butter. ‘At last the vision of Joseph Chamberlain has materialised. His dream is alive, and clothed in practical raiment’, Viscount Elibank proclaimed to the House of Lords two months after the conference had closed.Footnote 69

Amery had feverishly organized and lobbied behind the scenes for an imperial customs union in the three years leading up to Ottawa. He partnered with interest groups that opposed international free trade, notably Mond of ICI. Together, they established the Empire Economic Union (EEU) in 1930: a prominent industry lobby group agitating for ‘single imperial economic unit’. The EEU expanded upon the work of the British Empire Producers’ Organisation and the Empire Industries Association (EIA). The EIA had been launched in 1925 by Joseph Chamberlain himself—on the eve of his death continue the tariff reform programme. It threw its weight, including that of over forty backbencher Conservative MPs, behind Amery’s campaign for imperial economy union.Footnote 70 The EEU looked to anchor imperial economic union in more than a simple system of Imperial Preference, or even a single imperial market. They envisioned a comprehensively organized economic block that resembles the European Union today. The EEU called for a ‘common or complementary fiscal policy’, ‘an Empire-wide plan’ for agriculture and industry, an ‘Empire policy of communications’ and even ‘Empire monetary and investment policy’.Footnote 71 Mond argued that the British Empire should follow this trajectory to guarantee its geopolitical supremacy, not simply to reap economic gains. He pointed out that the Empire was probably the only unit in the world that could become self-sufficient. Its territories boasted the broadest diversity of products, foodstuffs, and raw materials: everything needed for war, industry, and consumer prosperity, from Malayan rubber, to Canadian nickel and wheat, to British chemicals and manufacturing.Footnote 72 Ultimately, the Ottawa Conference did not establish anywhere near the single market the EEU had hoped for. But it can be seen as a basic triumph for Amery’s three-decades-long campaign. Britain fully buried its commitment to unilateral free trade and the MFN rule. Meanwhile, economists have since determined that the new tariffs and quotas implemented at Ottawa accounted for three-fifths of the increase in the empire share of British imports, which soared from 27% in 1930 to 39% in 1935.Footnote 73 UK exports to Empire countries increased, in turn from 43.5% of total British exports in 1930 to 50% in 1938.Footnote 74 Despite these successes, Amery still never saw the full achievement of imperial economic union.

Amery’s prediction that the future would belong to the great powers that embraced protectionism and economic nationalism bore out in the short run—at least until the rise of US free trade hegemony after 1945. He had provided a few convincing reasons why economic nationalism—or really economic regionalism—was ‘inevitably destined to be the dominating conception of the coming generation’. He pointed first to the new imperatives of national security since the First World War. The Allied blockade of Germany had demonstrated that a modicum of self-sufficiency in raw materials was essential for military preparedness and national defence. He likewise pointed to the increasing industrial competition Britain faced from German and American goods. Third, and perhaps most perceptively, Amery predicted that economic nationalism had to accompany the rise of democratic mass-politics. Here we see Amery’s social conservatism shining through. He believed that free trade would be incompatible with twentieth-century advances in social reform. Demands for full and stable national employment and pressure for higher wages would impel Britain and her Dominions to erect protectionist barriers against lower-wage markets.Footnote 75

The neo-mercantilist revolt against free trade which had been brewing globally since the late 1870s ultimately reached its paroxysm in the 1930s.Footnote 76 Fascist Japan, Soviet Russia, and the Third Reich were industrializing and militarizing their economies at break-neck speeds and with unprecedented reliance on self-sufficiency.Footnote 77 These countries essentially took the Tariff Reform revolt, including its basic mercantilist, geopolitical and Social-Darwinist impulses, much farther than it could ever have gone in Britain. A Nazi economist explained the Third Reich’s turn to autarky in 1935 by arguing that trade had always been a ‘tool of great power politics’. If free trade, as List argued, had buttressed the British Empire’s global supremacy in the Victorian age, economic self-sufficiency served the Third Reich in the totalitarian age.Footnote 78 Britain did not turn autarky to the same extreme in the 1930s, probably because the culture of liberal free trade had far deeper historical and cultural roots. But even in Britain, the high Victorian free trade consensus had cracked. Amery and Chamberlain had been rather lonely voices in the wilderness before 1914. By the late 1920s and early 1930s, however, Amery had gained many allies for imperial economic union, especially from the dissident so-called ‘diehard’ ranks of the Conservative Party and business elite. Sir Henry Page Croft MP and Lord George Lloyd of Dologran—both leaders of the still-ongoing tariff reform movement and two important Conservative ‘Diehards’—rallied to Amery’s side.Footnote 79 His support ran deep into industry too. By 1929, the majority of the Associated Chambers of Commerce, Federation of British Industries, and even the Trades Union Congress all favoured more protection.Footnote 80 In 1929, Baldwin and the Tories won the election on a protectionist platform. But for Amery and many others, this did not go far enough. Lord Beaverbrook founded the Empire Free Trade Crusade in 1929 to push the Tories and Baldwin to embrace a programme for further Imperial Preference with sights ultimately set on an imperial free trade union.Footnote 81 After contesting the 1930 election and threatening to steal at least fifty seats form Conservatives, Beaverbrook quickly joined forces with his fellow press baron Harold Hamsworth, Viscount Rothermere. Rothermere went on to be an outspoken British sympathizer of Hitler and fascism.Footnote 82 Owner of the Daily Mail—the most-sold British newspaper in 1930—he established a second splinter Tory faction, the United Empire Party (UEP). Like Beaverbrook’s Crusade, the UEP advocated for an Empire free trade area protected by a common external high foreign tariff. Financed by other major business magnates, including Sir Hugo Hirst of British General Electric, as well as McGowan and Mond—they subscribed £2,500 apiece to the UEP—Beaverbrook and Rothermere shared much of Amery’s same vision.Footnote 83 They took it to an even more radical extreme. All this goes to show that, rather than being out of step with the times, Amery had anticipated them.

Anti-universalism: against the League of Nations

Amery’s anti-internationalism naturally made him one of the most outspoken British critics of the League of Nations. In his Forward View (1935)—the most thorough exposition of his worldview, which Mussolini himself read with great interestFootnote 84 —Amery lambasted the League.Footnote 85 He discerned more clearly than most of his contemporaries how the new international organization threatened the British Empire’s power: a fact historians have only recently begun to reckon with.Footnote 86 He frankly expressed his outrage at the League’s attempt to democratize international relations; he considered it a farce that both Britain and the US could be outvoted by Liberia, Montenegro, and Guatemala at the League General Assembly.Footnote 87 He also could not stand that the League’s Permanent Mandates Commission had won the right to interfere in the Empire’s internal colonial governance.Footnote 88

Amery’s evisceration of the League anticipated the familiar realist critique of liberal internationalism popularized by the historian E. H. Carr’s The Twenty-Year Crisis in 1941. Carr argued that the League failed because it had been utopian.Footnote 89 Amery outlined a similar logic in early 1935 just as Mussolini began to invade Ethiopia in violation of the League’s Covenant. Amery contended that the League had floundered because its ‘idealist’ liberal founders had put their trust in moral pressure—or public opinion—for enforcing the organization’s collective security pact. He did not ignore the significance of the economic weapon enshrined in Article 16 of the League Covenant. But with much of the British left, he considered the sanctions implemented against Italy far too weak to be effective.Footnote 90

More basically, however, Amery argued that the League’s maintenance of world peace was doomed because of its internationalist or ‘universalist’ organizational structure. The General Assembly had indeed been modelled on the aspirational vision of a world parliament of nations, with its Council playing the role of executive.Footnote 91 The League’s incapacity, Amery claimed, stemmed from its method of solving international problems. It usually proceeded by convening great international conferences, with the most universal membership possible. But most of the grand resolutions remained a dead letter.Footnote 92 Amery pointed to the League’s poor record enforcing its collective security pact and implementing its agenda for world economic reconstruction. These included the increasing failure of the League to preserve the Versailles territorial settlement as Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, Mussolini marched into Ethiopia in 1935, and Germany rearmed. But already in 1921-22, the Washington Disarmament Conference’s had not successfully slowed a naval arms build-up. The World Economic Conferences—first convened in Geneva in 1927, then in London in 1933—had recommended a universal customs truce to slow escalating trade wards in Europe: to no avail. Amery held, instead, that most problems submitted to the League’s attention all had regional rather than truly international solutions.Footnote 93 He placed his hope for collective security in regional pacts and alliances, such as the 1925 Locarno Treaties and the Little Entente between Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia, or the 1935 Anglo-American Naval Agreement and the Stresa Conference’s attempts to placate Mussolini and Hitler.Footnote 94 Amery thus held that world peace, stability, and international order would best be regulated not by the League of Nations or a single world organization, but by a balance of power between roughly equal, regional great-power blocks. In true realist fashion, he condemned liberal internationalism and drew on the playbook of classic British imperial diplomacy dating back to the Congress of Vienna.Footnote 95 He did give it a new gloss, however. The purpose of this regionalist balance of power was not, at least officially, to underwrite British hegemony, but rather to manage world peace. Amery prescribed that each block—the British Empire, a Pan-European federation, and others—should be comparable in size, territory, population, and resources in order to deter open military confrontation between them. Small nations without the means to defend themselves on their own would enjoy the protection of being included in a larger regional block. Finally, Amery insisted that regional blocks should be as ‘self-regulating’ as possible: in sum, local, or transnational problems within a federal block should be resolved internally.Footnote 96 Genuine remaining world problems could then be solved via diplomatic discussions between blocks. This helps explain Amery’s outrage cited above at the League’s Permanent Mandates Commission’s internationalization of British colonial governance. It also elucidates his commitment to resolving the Ethiopian crisis outside the mechanism of the League through the more traditional channels of European diplomacy.

Recent revisionist histories have challenged the traditional narrative that the League failed. Historians have demonstrated how League recorded remarkable successes in technical fields of global governance, from air traffic control to public health, to international police cooperation, and the combat of sex trafficking.Footnote 97 Irrespective of whether or not Amery’s critique was accurate, it remains historically significant because it reveals a thoughtful and thorough critique of liberal internationalism that developed in Britain during the 1930s. The disillusionment spread across political ranks: from Conservative die-hards to new radical left factions splintering off from the Labour, Party—notably the Socialist League and Independent Labour Party formed in 1932—to Oswald Mosley’s cohort of British fascists.Footnote 98

For Amery, world ordering should chiefly aim at reducing the number of states by consolidating them into larger federations. He saw the creation of the British Commonwealth as working towards this end. This also helps explain his eager support for the Briand Plan. Indeed, Coudenhove-Kalergi’s Pan-Europa project was grounded on the same vision of world ordering, hence the Count’s mutual support of Amery’s agenda to unify the Empire, and for other interwar Pan-American and Pan-Asian movements.Footnote 99 It is worth noting that neither Amery nor Coudenhove-Kalergi’s federalism opposed nationalism or nation-states per se. Instead, their projects encouraged nationalist identities to broaden out into ‘wider-nationalist’ blocks that built upon common cultural, ethnic, historic, and linguistic heritage.Footnote 100 The Empire Marketing Board can be seen as contributing to the construction of a wider nationalist imperial identity. However, Amery’s vision of the British block did include the whole Empire beyond the classic contours of ‘Greater Britain’: traditionally defined as a union of only white English-speaking peoples in self-governing Dominions, Britain, plus the US.Footnote 101 With the creation of the Commonwealth by the Imperial Conference’s Balfour Declaration of 1926—then formalized by the Statute of Westminster in 1931—Amery rejoiced that the Empire was on its way to becoming a constitutional association of ‘free and equal’ nations. He explicitly looked to the Commonwealth’s eventual embrace of all the Empire’s diverse races and peoples: to the eventual inclusion of India and all the non-white colonies.Footnote 102 This set him apart from Greater Britain advocates, such as John Seeley, Charles Dilke, H. G. Wells, Lionel Curtis, Philip Kerr, and Oswald Mosley. To be sure, Amery still retained a tacitly racialized vision of the Empire and Commonwealth: he envisioned two distinct tracks to full inclusion. Amery ensured, as Secretary of the 1926 Imperial Conference, that the White Dominions were automatically granted the constitutional status of free and equal partners to Britain within the new Commonwealth. Meanwhile, the non-white colonies had to prove worthy of self-government first.Footnote 103 Finally, Amery only ever wanted to reorganize the Empire, never to supersede or dissolve it. Between the wars and through the crucible of the 1940s, many liberal imperialists, from Curtis to Kerr, looked to the Empire’s reorganization into the Commonwealth as the path to world government.Footnote 104 If they wanted a unified Empire to provide the embryo for a world government, Amery instead believed the Empire provided a model for how to organize the world into regional blocks.

It might come as a surprise to discover, then, that Amery did not reject the ultimate creation of a world state. The League was simply a ‘counterfeit’ world super-state since it lacked the proper legal enforcements and sanctionist powers to back up its Covenant.Footnote 105 Amery argued that the League of Nations could never have become an effective world state because it bypassed an important stage in world political development. A world state could never be built upon the anarchy of small nation-states. It had to rest upon the solid foundation of wider-nationalist federations. And since the League’s universalist approach often obstructed regional unions—it had vetoed the Austro-German customs union in 1931Footnote 106 —Amery actually considered the League an impediment to achieving eventual world government.Footnote 107 This might explain Amery’s surprising expression of initial sympathy for Nazi ambitions of a German-dominated Central-European block—a Mitteleuropa—even after he had waded through the sordid pages of Mein Kampf. When Amery met Hitler personally in the Bavarian Alps, at Obersalzberg on 13 August 1935, he wrote in his diary that ‘on the European problem, he [Hitler] talked what seemed to me vigorous commonsense’.Footnote 108 Still, Amery acknowledged they their discussion had strategically stayed clear of ‘controversial subjects like Austria, constitutional liberty, Jews or Colonies’. It might be shocking to find Amery supportive of Hitler’s economic precepts. Amery is best-known, after all, as one of the first and harshest critics of appeasement in 1938, calling on his fellow Lords in Parliament to resist Hitler’s territorial expansion. By Munich, he was busy drumming up support for National Service (i.e., conscription) and for Winston Churchill’s campaign to create a Minister of Munitions to boost defense spending and organize rearmament.Footnote 109 Amery was no Nazi sympathizer. He even disowned his eldest son who had been tried and hanged for treason in 1945 as a Nazi sympathizer.Footnote 110 Yet like so many European statesmen—including Hitler—Amery lamented the Versailles territorial settlement’s fragmentation of Central Europe new into rump states, adding roughly 11,000 kilometres of borders to the map.Footnote 111 Amery believed the Old Continent would have been more stable if Germany and Austria had been allowed to, at least, commercially federate. Indeed, had had even initially looked favourably upon a ‘Central Economic union in which Germany could find an economic sphere, a Lebensraum’.Footnote 112 But he soon changed his mind by 1937 when he discerned that Hitler harboured far more ambitious and violent plans for territorial expansion in Europe and in the colonies. In 1929, Amery very significantly condemned Nazi Germany as an ‘anti-European power’.Footnote 113 He had finally determined that Hitler’s ambitions, like Kaiser Wilhelm’s before him, were not to create a wider-nationalist block on the continent, but rather to grasp at world hegemony through total war.Footnote 114 This would upset the balance of power between the regional blocks. Perhaps more crucially, it would threaten the British Empire’s naval supremacy. Amery’s core concern, after all, was always to devise a world order amenable to the British Empire’s continued geopolitical supremacy.

Anti-Americanism: the ‘open door’ and the Second World War

Amery always expressed profound distrust, even hostility towards the US. His anti-Americanism distinguished him from most British imperialists who tended to regard the US as Britain’s natural partner in the project for world power. Amery saw the US instead as the British Empire’s greatest rival—sometimes even an enemy—despite the two states’ undeniable cultural, ethnic, and linguistic commonalities. In 1910, he had genuinely feared that the US might form a coalition with Germany to wage war on Britain.Footnote 115 That seemed absurd only a few years later. We have also witnessed how Amery made constant fearful comparisons between the British Empire’s backward development and America’s massive internal market to strengthen his case for tariff reform.Footnote 116 Competing, rather than partnering, with the US guided Amery’s policy. Long before the US abandoned its own isolationism and protectionism to embrace free trade in the Second World War, Amery had begun to worry about the setting British imperial sun in the face of brilliant US ascendancy. In this sense, Amery shared greater affinities, once again, with European federalists, such as Coudenhove-Kalergi and Aristide Briand, but also the Nazis, including Hitler himself. The various projects for a ‘United States of Europe’, a ‘Pan-Europa’, or the Third Reich’s Grossraumwirtschaft that all proliferated after 1918, were fundamentally motivated by fear of the rising spectre of American global power, and a desire to match its unprecedented continental scale.Footnote 117 Amery’s fear of rising US power had driven him to campaign for tariff reform. His anti-Americanism reached fever-pitch by 1945-46 once the US seemed on the brink of world economic hegemony and it had turned to push free trade onto Britain. The conditions of Lend-Lease, the new Bretton Woods order, and the Anglo-American loan of 1946 posed an existential threat to the economic foundations of the Empire laid at Ottawa in 1932.

As President of both the Empire Industries Association (EIA) and the Empire Economic Union (EEU), Amery lobbied hard against the British government’s post-war commitment to liberalize the Empire. Giving up Imperial Preference to adopt free trade had been the price Britain had to pay for American assistance to fund both the war and the peace. Just as the Attlee government readied itself to sign the terms of the American loan granting Britain. $3,75 billion for reconstruction on 15 July 1946, Amery warned that the Empire’s survival was at stake. Echoes from Chamberlain’s Tariff Reform propaganda resounded: ‘The American demand for the elimination of Empire Preference’, Amery warned, ‘is a direct denial of the right of the British Empire to exist’.Footnote 118 By unravelling all the preferential trade agreements between Britain and her Dominions and colonies, Amery feared that the US would dissolve the whole imperial edifice. Amery was not being paranoid. Historians have established that the decolonization of the British Empire via the imposition of the ‘Open Door’ to free up closed imperial markets had precisely been one of President Franklin Roosevelt and Secretary Cordell Hull’s key war aims.Footnote 119 Amery and the EEU were convinced that the Americans had long been working to abolish Imperial Preference. This effort had arguably begun with the bilateral US-UK trade agreement signed in 1938, which had restored the MFN principle after its abrogation in 1932 by the Ottawa Agreements. Imperial Preference had thus been curtailed, but not eliminated, across a range of primary commodities. It was not until the war that the US launched its full-fledged offensive to impose free trade on the British Empire.

It all began with the infamous Article VII of the March 1942 Lend-Lease Agreement. The pact made US assistance to Britain’s fight against the Axis conditional on the ‘elimination of all forms of discriminatory treatment in international commerce, and to the reduction of tariffs and other trade barriers’. To be sure, Churchill had already committed Britain to a modicum of post-war free trade when he signed onto the Atlantic Charter with Roosevelt in August 1941. The lofty statement had included a clause promising that both powers’ commerce would return to the MFN rule once peace returned. Whether Churchill saw this simply as an aspirational declaration, rather than a binding declaration of post-war policy, he vociferously opposed the Lend-Lease Act’s universal trade liberalization agenda. Both he and John Maynard Keynes at the Treasury Department considered Article VII’s terms thorougly unacceptable: totally “lunatic” and “sordid”.Footnote 120 It spelt the end of Imperial Preference, and thereby dealt a fatal blow to the economic foundations of the British Emipre. Once the war was over, American manufacturers would undoubtely be better placed than exhausted Britain to supply British colonies. Without continued tariffs, Britain would therefore lose preferential access to its own imperial export markets. To harden the blow, Britain would likely on depend US loan financing to pay for its own imports. This was a double blow. But in 1942, Churchill’s government had no room for manoeuvre. During the war’s national emergency, Britain had to make definite concessions to the US over the rules that would govern post-war trade: including ceding the protectionist foundation of the Empire.

The British government had felt that it had no alternative but to cave to US demands. Amery disagreed. To be sure, he accepted that the Second World War had dealt a massive blow to Britain’s geopolitical position and made it economically dependent on the US. In his tirade against the 1946 Anglo-American loan, he recognized that Britain on its own patently lacked the ‘material basis’ for its global power. But this did not mean Amery accepted the inevitability of American economic hegemony or the decolonization of the British Empire. In fact, it made him—like many other imperialists, including Churchill who refused to give up India—fasten his grasp tighter onto the Empire.Footnote 121 He became more committed than ever to Imperial Preference. For starters, he understood that the continued generation of balance of payments surpluses through inter-imperial trade—generated through the interwar preferential system—was perhaps the only way Britain could pragmatically hope to pay off its wartime debts to the US, let alone finance basic post-war reconstruction. Between 1919 and 1933, Britain had consistently imported more from the Empire every year than it exported: both in manufactured goods and in foodstuffs, which likely had to do with some unreciprocated tariffs.Footnote 122 Imperial Preference would also be essential if Britain had any hope to remain a self-sufficient great power. Greater intra-imperial trade could reduce Britain’s foreign economic dependence on US exports and dollar loans. Amery even believed, along with the EIA and EEU, that if the Empire could remain economically united through preferential tariffs, it might still surpass the US because of its superior stock of resources and territory. Thus, the EEU and EIA not only lobbied the British government to reject the terms of the Anglo-American Loan in 1946 and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1947; they also called for the extension of the 1932 Ottawa Agreements. They wanted to expand, not roll back, Imperial Preference and self-sufficiency in the post-war world—mostly to no avail.Footnote 123

From Amery’s vantage point, American post-war economic internationalism and the Open Door policy amounted to economic imperialism. The loss of preferential trade would force Britain into the status of a ‘subordinate’ colony of the US. In a speech he gave to the EIA in March 1946, Amery reframed the government’s talk of Anglo-American cooperation as a stealthy project of American ‘domination’. He noted that American export interests were determined to break up various elements of the British Empire in order to then absorb them as new markets into the wider ‘American economic system’. The establishment of the US gold-backed dollar as the post-war world reserve currency—anchored by the new 1944 Bretton Woods institutions, the International Monetary Fund, and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (to become the World Bank)—also meant that Britain had effectively handed over ‘the control of its monetary policy, which lies at the root of social and economic policy…to an international committee sitting in America from whose decisions there is no appeal’.Footnote 124 He could not believe that the British Labour government had, in accepting the terms of the 1946 Anglo-American loan, effectively subjected the country to an ‘American dictatorship’Footnote 125 and ‘denationaliz[ed] the control of our economic life’.Footnote 126 In Amery’s eyes, the new project of American economic internationalism both jeopardized the Empire and eroded British national sovereignty.

The irony that Amery—a devout British imperialist—denounced free trade as a weapon of ‘American economic imperialism’ should not be lost to us.Footnote 127 Still, we must remember that Amery had never been a fan of British free trade imperialism—he had sought to dismantle it. And this was the brand of American Open-Door imperialism that emerged from the Second World War, as the US abandoned its longstanding isolationism, both economic and political.Footnote 128 In a sense, the US simply took over the mantle from the UK. As a result, Amery predicted that under the new Bretton Woods order, ‘all countries…will be permanently economically enslaved by the United States of America’. The US had, indeed, emerged prodigiously richer from both wars: it was now both the world’s leading creditor and manufacturer. Most European belligerents, including Britain in 1945, were massively indebted to the US. The US additionally owned between 85% and 90% of the world’s gold stocks. For countries to buy goods from the US, they would therefore first have to borrow from the US. If Britain lost Imperial Preference, then most countries in the Empire would choose to purchase US exports, since these would become suddenly cheaper than British goods. Amery predicted that countless Dominions and colonies ‘will fall under the domination of American capitalism. As to Great Britain, she is already enslaved due to her vast debt burden.’Footnote 129 An American free-trade empire would replace the British mercantilist Empire Amery had worked hard to build.

Finally, Amery argued in 1945 that the preservation of British Imperial Preference could serve as the most effective bulwark to American world domination. It would help preserve international peace by preserving a more equitable balance of power between regional economic blocks. ‘There are but two things which stand in the way of total world economic domination by the USA’, Amery argued: ‘Russia and Imperial Preference’. By 1946, Amery already foresaw the emerging Cold War’s bipolar division of the world. And as a virulent anti-Communist, Amery hardly placed any hope in the Soviet Union. He believed that the British Empire, bounded together by preferential trade ties, could act as a third force. Here he anticipates Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin’s, diplomatic positioning of Britain in the early Cold War two years later.Footnote 130 The imposition of free trade, however, would accelerate this dangerous bipolarization. If more economies, outside the Soviet sphere of influence, were forced to adopt the US dollar in international trade and transactions, plus sign onto the MFN principle, this would throw these economies into the orbit of the US capitalist block. Amery’s EEU noted that this could only ‘lead eventually to the inevitable clash’ between the US and the Soviet blocks. He did not specify what might happen, but the suggestion that a third world war could ensue is the obvious subtext of his warnings. What could stand in the way of such an outcome? The presence of a strong third block to counterbalance the US and the Soviet Union. Obviously, the British Empire was the best candidate in his eyes: it could provide ‘a third alternative, a middle way’.Footnote 131 For the sake of world peace, the Empire and its system of preferential trade had to survive.

The true crime of US free trade internationalism, in Amery’s eyes, probably lay in its repudiation of a world organized into roughly equal economic blocks. If many regionalists became internationalists after the Second World War, whether reluctantly or willingly, Amery remained more wed to regionalism than ever before. He condemned US economic internationalism as an imperializing project. The US was transcending its Pan-American boundaries to meddle in the sphere of the British Empire by dictating free-trade policy.Footnote 132 But Amery had never been clear on one thing all along in his theorization of world order. If the British Empire, unlike all the other blocks he discussed, was trans-oceanic and, thus in a way genuinely world-wide, did he really ever countenance it having an equal status and position to all the others? Indeed, not—and most certainly not, when it came to naval power. Amery always firmly maintained that Britain should retain its right to control the high seas. As ‘child of sea power’, Amery held that the British Empire had to maintain its supremacy over the high seas, or else he prophesied that it would ‘fall to pieces’.Footnote 133 If this was his conviction on the eve of the First World War, he still held fast to it in 1935 when he lamented the Washington Conference’s ‘one-power standard’ that had limited Britain’s fleet to the size of any other powers.Footnote 134 Amery’s theory of world blocks always sat uncomfortably with the desire to maintain the Edwardian summer of the British Empire’s global hegemony. Perhaps the real crime of US free trade internationalism was not so much that it was imperialistic or hegemonic, per se, but that it threatened to simply displace British imperialism.

Conclusion

For all Amery’s talk of equal regional blocks, it becomes clear that Amery’s ultimate concern was always to preserve the power of the British Empire. He believed protectionism, and a regionalist approach to Empire-building, would be the best way to preserve Britain’s global power in an increasingly competitive and unstable world. This explains his profound hostility to Britain’s long-term commitment to unliteral free trade, the League of Nations, and American power—particularly after the US’s embrace of economic internationalism in the crucible of the Second World War.

Beyond excavating Amery’s important contributions to debates on the British Empire and world order, this article has sought to resituate these debates within broader currents: notably the clash between regionalism and internationalism. This clash produced what we might call a European interwar ‘federalist moment’. Historians have recently recovered the foreclosed schemes for federal union in Africa and beyond spawned by decolonization in the 1950s and 1960s.Footnote 135 But federation equally captivated the imaginations of Britons and continental Europeans after the First World War. If interwar historians have focused on varieties of internationalism, countless schemes for regional federation simultaneously proliferated: from the Briand Plan for a United States of Europe and Count Coudenhove-Kalergi’s Pan-Europa Union, to movements for a Greater France,Footnote 136 Greater Britain, and Pan-Germany; to a plethora of proposals for Austro-German, Balkan, and Danubian customs unions which sought to recreate some of the erstwhile unity of the continental empires dissolved at Versailles in 1918-19.Footnote 137 Amery’s persistent campaign for British imperial commercial union—from the days of Chamberlain’s Tariff Reform League in 1903 to the Ottawa Conference in 1932—marched in lock-step with this broader movement. If Amery’s thought is certainly distinctive, the trajectory of his career is representative of the growing regionalist and neo-mercantilist revolt against liberal free trade and internationalism that swept Europe and the globe in the 1930s. Amery specifically illustrates how this revolt penetrated Britain—the supposed heartland of liberal internationalism—and found a particularly receptive ear among imperial business interests. This suggests that the liberal international order established in 1919 was built on far more precarious ideological foundations than may be often supposed.

If Amery’s vision of a regionalist world order won out by the rupture of 1932-33, historians have heralded the Allied victory in the Second World War as ushering in a new age of American-led liberal internationalism.Footnote 138 This may be an overly triumphalist narrative. Regionalist political and economic ordering of the world never fully died out after 1945. The Cold War soon split the world into two hostile ‘regional or ideological groupings’ ironically led by the US and Russia: the two continental powers long predicted to dominate the world. Meanwhile, European overseas empires were dismantled only slowly. Neo-colonial ties persisted, both within formal organizations like the British Commonwealth and the Sterling Area or the Francophonie, and within informal patterns of neocolonial trade dependencies. Finally, the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), and the eventual European common market, could be seen as the regionalist post-1945 project par excellence. Indeed, West Germany’s Economics Minister, Ludwig Erhard, opposed European integration precisely because he feared it augured a return to the interwar’s regionalist ‘ideology of big blocs’. He warned, on the eve of the 1957 Treaty of Rome which instituted the European Economic Community that if the ‘Common Market does not adopt a clearly liberal trade policy towards other economic areas’, then ‘we are threatened with a return to other ideological conceptions of a truly unhappy past, viz., the splitting of the world into so-called big blocs’. This would fuel a repeat of the interwar crisis and its trade wars.Footnote 139

We can only conclude that projects of regionalist and universalist world order constantly clashed and fed off each other throughout the twentieth-century—despite the caesuras of both world wars in the history of globalization. This dialectic between internationalism and regionalism is truly one of the defining features of twentieth-century global history, and it persists into our present. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the 1990s may have appeared to herald another temporary triumph of American (neo)-liberal internationalism and ‘one-worldism’. But the post-2008 era has witnessed another populist revolt against globalization, from both the left and right. The revival of trade wars, the increased tendency for bilateral trade negotiations to replace multilateralism, populist calls for stronger borders against the migration of people, and more restrictions on the mobility of capital and commodities, reminds us that internationalism never triumphs for long.

Competing Interests

The author declares none, besides being a citizen of an erstwhile Dominion and having ancestors who benefited from Amery’s migration scheme.