Recounting his brief sojourn in Aden during the 1920s, the Syrian American writer Ameen Rihani soliloquized on the sights he witnessed at its harbour. Despite the grimness of the port’s spectral and desolate backdrop, Rihani marvelled at the thousands of tons of coal stacked by the foreshore (‘black piles rising in squares and pyramids near the water and adding a touch of realism to the inferno of Steamer Point’), forming, together with the imposing lighthouse and evocative telegraph station, Aden’s ‘trinity of materialism’.Footnote 1 As astute an observer as he was eloquent a writer, Rihani was keenly aware that the scale and scope of global capital and information flows was predicated on a chain of offshore stations like Aden, where steamships could replenish their coal supplies while shorefront godowns and telegraph stations gathered commodities and information to be received, processed, and relayed.Footnote 2 Having been seized by the Indian Navy in 1839 as the first territorial acquisition of the Red Sea steam navigation route, Aden formed the crux of a modular and rapidly expanding British transoceanic transportation and communication network.Footnote 3 The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had elevated the import of the station from an imperial to a truly global scale,Footnote 4 as by the mid-twentieth century over 5,000 vessels called on the harbour annually, making Aden the second busiest port in the world after New York.Footnote 5 ‘The whole world is interested’, reflected Rihani, ‘where, in one form or another, the whole world passes’.Footnote 6

Yet, none of this was inevitable. Throughout the first decades of its colonial existence, there was very little to suggest of Aden’s future prominence. The severe challenges posed by the abrasive heat and resource scarcity of the desert outpost were compounded by transformations unfolding beyond its shores: the ideological salience of laissez faire undergirded a commitment on Bombay’s part to cutting all public expenditure, and within eighteen months of the port’s seizure, both Governor James Rivett-Carnac in Bombay and Governor-General Lord Ellenborough in Calcutta questioned the expediency of keeping Aden, the former writing tersely: ‘[the seizure of Aden] was a bad move, and will be a constant source of expense and trouble to us’.Footnote 7 With the fledgling outpost increasingly looking like a liability rather than an asset, Bombay made it clear that funds for Aden will be kept to a bare minimum until ‘something like a return is obtained from that place’.Footnote 8 Across the empire, the exigencies of laissez faire capitalism dictated that the infrastructural overhaul of the age of steam was largely outsourced to private enterprise, but the absence of agricultural or industrial potential in a desolate, unproductive outpost like Aden rendered it unappealing to metropolitan capital, ironically precluding investment in the very site which facilitated and made possible imperial connectivity and circulation.Footnote 9

How then do we account for the making of an infrastructural space like Aden outside the remit of metropolitan capital?Footnote 10 Historians have long established that the form and extent of imperialism was determined as much by non-European collaboration and resistance as it was by European activity and Europe’s political economy.Footnote 11 British entrenchment in India was contingent upon access to indigenous credit and remittance networks,Footnote 12 while beyond the subcontinent, in the concrete geographies of empire as well as the abstract world of the Indian Ocean bazaar, European expansion likewise depended on local actors, institutions, and processes.Footnote 13 Imperial dependence was not limited to realms of finance and administration, however: across the reaches of the Indian Ocean, the investment, speculation, and attendant risks borne by non-Western capitalists were fundamental building blocks of imperial statecraft, from harbour construction schemes and steam navigation ventures to the establishment of transoceanic shipping, remittance, labour brokerage, and other maritime related services.Footnote 14 Indeed, where Western capital failed or refused to assume the mantle, non-Western capital stepped in in its stead. Of these transregional merchant communities, none were more consequential for the consolidation of European capital in Asia than Parsis, who bankrolled and supplied the Canton opium trade that ‘laid the economic foundations of the imperial economy’.Footnote 15

Perennial strangers-in-a-foreign-land, the capacity to accommodate and modify itself is inscribed in the very genesis of the Parsi community.Footnote 16 Parsi fluidity and adaptability, as well as an intimate familiarity with Islam, aided their rapid integration into the Portuguese and then British imperial fold.Footnote 17 As On Barak has argued, overseas Parsis served as a colonial vanguard whose technological innovativeness and legalistic propensities provided a foil to hostile climates and to the sanitation and security concerns of the age of steam, namely the ‘twin infections’ of cholera and Islamic radicalism.Footnote 18 Indeed, Parsi capitalists have been described as ‘partners in empire’;Footnote 19 but while Parsi ledgers and British gunboats jointly reshaped the political economy of the Indian Ocean, it was also the latter’s singular ability to effect coercive measures which capped the scope of Parsi success and ultimately led to its decline, as Company monopolies and racially-inflected glass ceilings in India and China forced Parsi merchants to subordinate their capital in its service.Footnote 20 In the 1840s, Parsis gradually withdrew from the opium trade.Footnote 21 The decline of their fortunes in China marks a pivot in Parsi historiography, with historians focusing on a transition from merchant capitalism to swadeshi industrialisation, yet the endeavours of Parsi capitalists west of Bombay, all but absent from the literature, represent continuation rather than rupture.Footnote 22

Like their fellow Zoroastrian merchants in other reaches of the Indian Ocean, the Parsis of Aden forged a distinctive identity of conscientious industriousness.Footnote 23 Parsi firms supplied both shore and shipping requirements for ships calling on Aden, providing brokerage and agency, or dubash services, literally meaning ‘two languages’, or ‘translator’ in the vernacular. Indeed, much in the way that contemporary logistical rationalities are premised on a drive to render space equivalent, exchangeable, and interchangeable, so were Parsis integral in rendering foreign spaces commensurable and thus legible to Western modalities. More than a particularly successful comprador community, however, Aden Parsis developed an elaborate transoceanic trade predicated on self-financed, capital-intensive infrastructure projects. Imperial political economy may have dictated that even the most successful Parsi merchants had to attach themselves to British trading houses in India and China, but British firms were not attracted to invest in a far-flung enclave with scant potential for profits such as Aden, leaving Parsi capital free to assume its own position of power and influence. As will presently be shown, Parsis had the run of the market in Aden, driving and ultimately coming to dominate the commanding heights of the port’s economy.

What follows then is an exploration of how Parsi capital shaped the development of Aden as a site of imperial infrastructure. I start by following the agents and brokers who served as key mediators of international shipping’s interface with Aden, provisioning ships, brokering sales and purchases, and providing facilities through the finance and execution of for-profit logistics infrastructure projects. The second section traces how Parsi entrepreneurs exploited Aden’s free port status by repurposing and repackaging wasted sea frontage as valuable real-estate where globally assembled, discounted consumer goods were vended, establishing in the process one of the world’s first dedicated duty-free retail hubs. The third and final section examines the consolidation of their position in Aden by recounting the lobbying efforts of Parsi shipping interests urging for the harbour to be dredged, a seemingly straightforward venture which nevertheless led to an impasse that would take over a quarter of a century to resolve, culminating in the formation of an institutional body affording Aden’s private firms, with Parsis at the helm, the statutory power to streamline the exigencies of their interests.

Agents of empire: recasting the colonial dubash

On the afternoon of 19 January 1839, in the immediate wake of the East India Company’s seizure of Aden, as the 700 sepoys and European soldiers of the Indian Navy who had successfully stormed the beach in Front Bay were setting up temporary camps, a dilapidated storehouse opposite a ruined jetty projecting into the sea was being repurposed as a commissariat.Footnote 24 Looking out at the precipitous volcanic amphitheatre surrounding them, the officers and clerks tasked with provisioning the fledging outpost were faced with a grim vision, vividly described by a sojourner in 1843:

Never did I behold so frightful a region. The whole country seemed one mass of cinders and lava. Not a blade of grass was to be seen anywhere […] Frowning mountains, jagged rocks with bare grim sides, looked down with a terrible magnificence upon us […] Aden must, I should think, come about as near to Tartarus as any place that can be conceived of on earth.Footnote 25

The settlement quickly became heavily dependent on camel caravans from the interior bringing sacks of fresh water to supplement its limited supply, as well as firewood, grass, and vegetables—a life-line easily, and frequently, choked off by the intractable ‘Abdali tribes of neighbouring Lahej.Footnote 26 The Commissariat Department sourced provisions by steamships from Bombay, but the infrequency of the steamers and the perishability of easily decaying vegetables led to frequent shortages of an already-impoverished variety of foodstuffs and to chronic malnourishment of the troops.Footnote 27

The political agent, Stafford Bettesworth Haines, used every executive power in his means to shore up the settlement, but in material terms, as metropolitan investment hardly extended beyond the cantonment and no powerful local vested interests existed to prop up or co-opt, the political agent had to seek alternative avenues of capital investment. Indeed, the upshot of Bombay’s austerity was that while the Government of Aden retained and exercized responsibility over essential statutory functions, the facilitation and development of the civic and commercial infrastructure of the port was largely outsourced to native private capital. Despite the historical preponderance of Bania merchant communities in the western Indian Ocean, as it happened, it was not the traditional seats of capital and commerce in southern Arabia whose private investments and speculation offset Bombay’s frugality, but rather the recently arrived, small-knit group of resourceful Parsi entrepreneurs, conversant in the language and idioms of the new British sovereign in Aden.

In lieu of the volatile inland traffic, Parsi victuallers and dubashes fell back on coastal trade, tapping into and elaborating on an emergent oceanic food network predicated on European, Arab, and Turkish imperial expansion in the region, namely the rise of an island plantation system dedicated to non-subsistence monocultural production and the growth of non-productive commercial entrepôts. The extensive population movement and cosmopolitan urbanization that attended these processes created a regional dispersal of people with cultural and religious culinary requirements that could not be supplied locally, spurring an effervescent regional food market.Footnote 28 Grain and pulses were sourced from India and Persia; fruit from Mauritius, Singapore, and Egypt; fowl, including ducks, geese, and turkeys from Suez; and livestock for dairy and meat consumption from the Somali coast.Footnote 29 Apart from the garrison’s own hefty meat consumption,Footnote 30 the latter provisions were particularly desired by vessels and steamships calling on the port and provided almost exclusively by Parsi dubashes.Footnote 31 The intricate food import networks elaborated by Parsi dubashes turned the traditional idea of a hinterland supplying its port cities on its head, as Aden, the port city, increasingly played the role of supplier to its Arabian and African hinterlands.Footnote 32

Beyond metabolic imperatives, sweltering climates made hydration and any means of alleviating the heat the Archimedean point of ship-provisioning in Aden, as scorching temperatures reaching well over 100 degrees Fahrenheit made the Red Sea passage the most dreaded part of the transoceanic voyage.Footnote 33 In an arid terrain enjoying little to no annual rainfall like Aden, water supplies were a constant cause of anxiety to military, civil, and commercial interests. ‘The value of fresh water is strikingly brought home to you’, commented journalist Henry Cornish, ‘when you find that all your domestic servants, even to the coolies who pull your punkahs, insist on a portion of their monthly wages being paid in that indispensable commodity’.Footnote 34 To provide an affordable and readily-available alternative to the precious commodity, Parsi dubashes were early to import water-desalination technology in the 1850s.Footnote 35 A decade later, water-condensers on the grounds of the Parsi firms Eduljee Maneckjee & Sons and Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros., and the British Luke Thomas & Co. produced a combined 25,000 gallons per day.Footnote 36 Eduljee Maneckjee & Sons and Luke Thomas & Co. also operated small ice manufactory plants capable of producing one ton per day of ice, an indispensable commodity on board iron ships where artificial ice was used not only to keep perishable produce from spoiling too quickly, or to cool down sweltering European passengers and crewmen, but also ‘to resuscitate Somali and Arab engine-room stokers who often succumbed to heatstroke in the boiler room and were revived in baths of ice loaded at Aden’.Footnote 37 Parsi capitalist exertions in Aden did not however culminate in quenching thirsts and sating hunger, but rather were crucial in developing the logistical infrastructure of the port. Briefly homing in on the career of one such Parsi dubash, the aforementioned Edalji Maneckji Colabawalla, is instructive in this regard.

Born in turn-of-the-century Bombay, Colabawalla was a man of his time. As his sobriquet suggests, Edalji’s family owned a large estate in Bombay’s southern Colaba region, an estate that was later purchased by the district magistrate of Bombay and converted into regimental barracks. City-born, middle-class, and educated, Colabawalla spent his thirties employed as head-clerk of Bombay’s Town Hall under one Colonel Barr, passing most of his time in the company of British officers and bureaucrats.Footnote 38 By then, the sight of Parsis occupying the halls and offices of governmental institutions was not uncommon: the various departments comprising the administration of the Bombay Presidency were studded with mid-level Parsi clerks, cashiers, and accountants, part of a wider trend in which a ‘creeping European modernity’ incentivized Indian elites to take up new positions in the expanded educational and political establishments of the presidency towns.Footnote 39

In 1840, Colonel Barr transferred from Bombay to Aden to serve as advisor on municipal affairs, taking with him trusted members of his staff, including Colabawalla. The Parsi clerk was soon followed to Aden and into government service by other members of his family.Footnote 40 In its early days, the administration of Aden was a loose, if not dishevelled operation where personal rapport often prevailed over rank and procedure. Colabawalla quickly came into Haines’s orbit: through preferential treatment and patronage, Haines helped streamline the operations of a network of Arab, Persian, and Indian protégés and their families who not only occupied Aden’s administrative edifice but, more importantly, exploited their close proximity to the political agent and the competitive advantage of having one’s kin manning the corridors of power to establish successful private ventures.Footnote 41

Upon his arrival at Aden, Colabawalla opened a small grocery store under the encouragement and assistance of Colonel Barr. With Haines’s support, the Parsi won and for many years retained government contracts as food supplier to various local institutions, including Aden’s civil hospital and jail, as well as the monopoly contract to vend liquor to the settlement, a privilege forcefully defended by the political agent.Footnote 42 In 1840, Colabawalla’s newly established firm, Eduljee Maneckjee & Sons, became the first to provide dubash services in the port, going on to supply both shore and shipping requirements to major clients such as the British, French, and Dutch navies, the Messageries Maritimes, Anchor Line, Aden Coal Company, and numerous other British and foreign shipping companies.Footnote 43

As the scope of his firm’s operation was capped by bottlenecks resulting from inadequate facilities, it is not surprising that, in a commercial port chronically under-financed by the authorities in Bombay, moneyed Parsis like Colabawalla emerged as the primary entrepreneurial force behind the finance and execution of supply-side infrastructure projects. By the late 1840s, Front Bay, which for centuries had served as Aden’s main harbour, was beginning to silt up, with the facilities of the small port anyway becoming out of step with the requirements of large merchant vessels. As large, square-rigged merchantmen increasingly tended to call on the broader and better sheltered Back Bay, with local dhows following suit, an outport grew up on Ma‘ala beach opposite the Main Pass into the town, connecting the commercial centre of the settlement in Crater to the vessels docked in Back Bay.Footnote 44 In 1853, together with fellow Parsi Cowasji Dinshaw and a Persian merchant, Colabawalla sought to formalize the makeshift arrangement in Ma‘ala and increase the rate of turnaround by building a wharf with modern facilities. Colabawalla’s concern was awarded a 25-year contract, granting landing rights on the adjacent beaches and a licence to build and operate a pier.Footnote 45 After some preliminary difficulties, the project prospered and Ma‘ala Wharf emerged as the main cargo-handling sector of Aden’s port.

Edalji Maneckji Colabawalla. Source: Framroze Ardershir Dadrawala, Dhī Kāwasjī Dīnshāh Senṭīnir Memorial Volyūm (Aden: Messrs. Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. Printing Press, 1927), 173

The Parsi’s activities were not limited to Aden, as the expansive spatial and social networks Colabawalla traversed presented opportunities beyond the shores of Arabia. According to one community history, during a trip to Mauritius (Eduljee Maneckjee & Sons imported rum from Mauritius to Aden), Colabawalla learned that sugarcane plantations on the island were never manured, resulting in poor crop yields. Through his dealings with the Somali coast, he had been aware of a mound which housed a large bird habitat with concentrations of highly rich droppings; Colabawalla purchased land rights for the mound from the local Somali chief and harvested the guano which he then proceeded to export to Mauritius, with time emerging as the main regional supplier of the valuable fertilizer, of which he sent four barrelfuls to the British governor as a gift.Footnote 46 Unbound as they were by geographic, lingual, and cultural constraints, Parsi dubashes like Colabawalla were heavily relied upon by the British authorities to undertake logistics operations on the frontier, for example during the Abyssinia expedition in 1868: the scale of operations—13,000 soldiers were landed on the Abyssinian coast along with over 40,000 animals—necessitated extensive outsourcing of wartime logistics,Footnote 47 with Colabawalla personally accompanying the army in Abyssinia, providing logistical solutions at the vanguard of the expedition.Footnote 48

Aden’s first and most successful dubash, a prominent broker, a financier to both native and Western merchants, the first of Aden’s merchants to operate a private coal yard, and the most important private investor in harbour and municipal infrastructure,Footnote 49 throughout the first decades of the settlement, Edalji Maneckji Colabawalla was the most illustrious businessman in Aden.Footnote 50

Yet, provisions and logistics were not the only typologies of infrastructure to have been driven by Parsi capital in Aden. In 1850, the Government of Bombay declared Aden a free port, making it the latest instalment in a budding Indian Ocean imperial free port network including Singapore (1819) and Hong Kong (1841). Fitting these ports with a commodious economic regime including zero customs duties on all imports and exports, the East India Company employed territorial exceptionalism as a competitive advantage to undermine imperial rivals and quash entrenched neighbouring ports.Footnote 51 But as the following section will show, geostrategy notwithstanding, with goods as well as people now circulating freely, Parsi entrepreneurs were quick to capitalise on the opportunity, repurposing wasted sea frontage as valuable real-estate where globally assembled, discounted consumer goods were vended, establishing in the process one of the world’s first dedicated duty-free retail hubs.Footnote 52

‘Fattened mosquitoes and enriched Parsis’: leisure and commerce in the Prince of Wales’s Crescent

For passengers approaching Aden’s harbour during the early days of the settlement, the grim image of cindery, desolate peaks hardly inspired enthusiasm. Even so, most visitors calling at Aden in steamships were anxious to get ashore as fast as they could and for as long as possible. Early steamships were dirty, and a layer of coal dust lay everywhere and permeated into every cabin; during the coaling operation, conditions on board were significantly worse:

So very unpleasant is the necessary operation of coaling on board a steamer, with the thermometer at 104, that no one who could possibly avoid it would remain a moment on deck after the ceremony had commenced […] they were condemned, for four-and-twenty hours, to eat, drink, breathe, and be attired in, coal-dust; for decks, faces, garments, and edibles, all take the universal hue.Footnote 53

Alighting passengers were brought ashore in lighters or rowing boats; men were carried ashore through the sea on the backs of local Arabs or Somalis, while women walked along planks from the lighters to dry land, ‘resplendent with hats, veils, crinolines, and parasols’.Footnote 54 The shingle beach where they landed lay near to the P&O coal grounds at the western end of a crescent-shaped bight. The only refuge for sojourners resisting the prospect of sight-seeing in Crater whilst seeking to escape the coal dust was a lone hotel on the open beach, founded in 1840 by a Parsi merchant named Sorabji Cowasji Kharas.

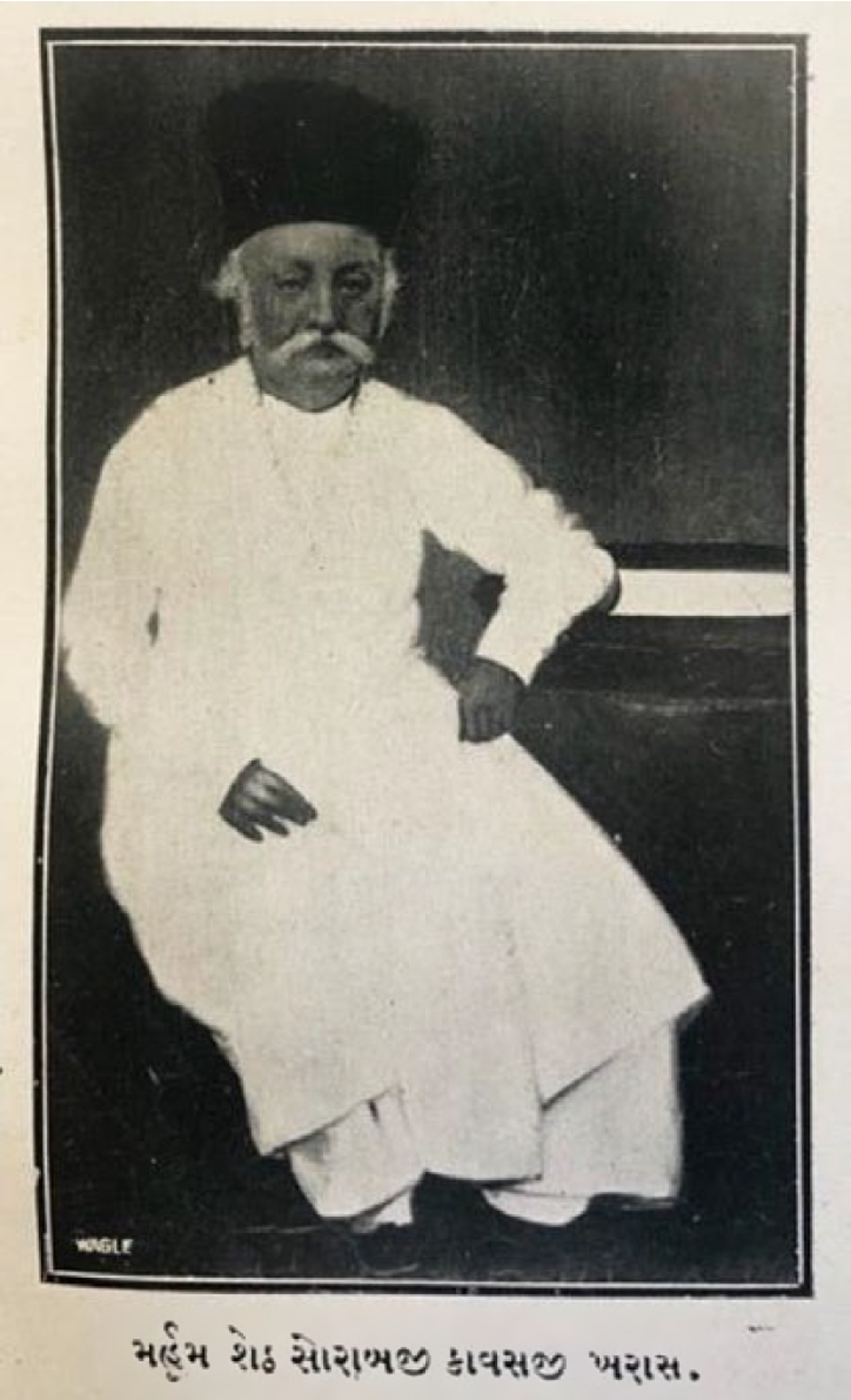

Sorabji Cowasji Kharas’s forebearers were pearl merchants that had come to settle in Bombay from Navsari. Sorabji’s father, Cowasji Behramji Kharas, resided in Bombay’s Bora Bazar, where Sorabji was born in 1801.Footnote 55 In 1828, Cowasji Behramji Kharas sailed to Canton to trade in pearls, accompanied by his brother-in-law, Nusserwanji Framji Baria, and Sorabji, who was brought along to assist in running the business and to learn the ropes of the trade. Within a short period of time, Sorabji ran his own pearl business in Canton which he operated for several years, before eventually shutting down and returning to Bombay.Footnote 56

The Kharas family had become acquainted in Canton with the Camas, a well-established, wealthy Parsi family who had been carrying trade between Bombay and Canton since the late eighteenth century.Footnote 57 It was on the advice of one of the Cama brothers, Pestanji Hormusji, that in 1840, Kharas decided to relocate to Aden. Kharas proceeded to load a baghlah with merchandise and sailed westward from Bombay, arriving at the port after a month of arduous travel, making him the first Parsi businessman to establish himself in Aden solely for the prospect of trade.Footnote 58 Sorabji’s first venture was a joint enterprise with the aforementioned Pestanji and his brother, Edalji Hormusji Cama, establishing a general goods shop and a small hotel named ‘Aden House’. The tremendous profits accrued in Canton, recycled as investment capital deployed by the Cama brothers in Aden via the medium of Sorabji Cowasji Kharas, is illustrative of the breadth and scope to which the opium trade opened and sustained imperial trade routes across the Indian Ocean, not just between China and Bombay. The partnership between Kharas and the Cama brothers was soon dissolved, however; the shop was closed, and Kharas retained possession of the hotel.Footnote 59

In a place possessing only the most rudimentary of political and administrative institutions and well-established but sporadic trade and communication channels, information and resources were both hard to come by and highly coveted. Soon after the liquidation of his partnership with the Cama brothers, the middle-aged Kharas went into partnership with his young co-religionist, Merwanji Sorabji Khareghat, a government employee sent from Bombay to Aden to serve as head-clerk of the settlement’s Commissariat Department. The two Parsis opened and operated a general goods store named ‘Merwanji Sorabji’. Beyond shared language and bonds of spirituality, Kharas was certainly cognizant of the advantages of sticking close to Khareghat, who in his capacity as head-clerk of the Commissariat Department was a central figure in the settlement’s main contracting body and was in close association with Haines. Kharas thus quickly entered the inner circle of men that Haines trusted personally and believed had the capacity, with the help of his patronage, to propel Aden to become the thriving entrepôt he had envisioned. The political agent lent Kharas money from the Aden treasury to refurbish the Aden House hotel, rechristened ‘The Prince of Wales Hotel’ in 1841 to mark the birth of Queen Victoria’s firstborn son, the then-Prince of Wales and future King Edward VII.Footnote 60

Situated at the mouth of Steamer Point, the hotel gave its name to the landing spot, often referred to as ‘Hotel Bay’ or the ‘Prince of Wales’s Crescent’.Footnote 61 As late as 1854, the hotel was still the only traveller accommodation in Aden, yet capacity regularly exceeded demand and many rooms were left vacant, as is evident by the notes of travel compiled by American merchant Joseph Barlow Osgood: ‘Never did ant make its abode in one of the many chambers of a human skull more alone that was I, the only boarder in this hotel’. The rooms of the hotel were furnished with a table and ‘a rickety catandah to sleep upon’, as well as ‘a line [extending] across the room […] to keep my clothes from the encroachments of numerous companies of rats that had provided themselves with gratuitous lodgings in the mat ceilings’.Footnote 62

Sorabji Cowasji Kharas. Source: Framroze Ardershir Dadrawala, Dhī Kāwasjī Dīnshāh Senṭīnir Memorial Volyūm (Aden: Messrs. Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. Printing Press, 1927), 165

The hotel housed a small shop operated by the young Parsi merchant Cowasji Dinshaw, servicing local denizens, the European and native troops of the garrison, and transient visitors calling briefly on the port. Dinshaw’s shop was ‘an emporium for every conceivable article’, including ‘carved sandal-wood, and embroidered shawls from China, Surat and Gujerat, work from India, English medicines, French lamps, Swiss clocks, German toys, Russian caviar, Greek lace, Havannah cigars, American hides, and canned fruits, besides many other things’.Footnote 63 Not all relished the variety, however, as the following description demonstrates:

Cowasjee’s shop consists of the whole house minus the roof, and it contains everything that a man does not want. I suppose that passengers going out to India anticipate here their Indian purchases, as passengers bound for Europe here invest their money in Paris gloves made at Malta, or in Windsor soap. There are some people to whom a shop is an abstract necessity for disbursement. Here, then, in Cowasjee’s you see men and boys buying Chinese slippers they will never wear, and all sorts of garments and articles they don’t want, and Cowasjee, a Parsee, with large olive coloured, oval, smooth face, quickeyed, and intelligent, place his hands on his portly person, and smiles placidly whilst his Parsee assistants glide round the curious shelves, and recommend things they never tried - Yarmouth bloaters, pate de diable, pith hats, pocket handkerchiefs, eau de cologne, Whitechapel cigars, Piver’s perfumery [etc.] At three o’clock we are steaming out of the harbour of Aden, leaving behind us fattened mosquitoes and enriched Parsees.Footnote 64

Whether one marvelled at its variety or scoffed at its excesses, Cowasji Dinshaw’s shop stood apart not only for its selection but also for its isolation. There were several other shops located in the nearby Tawahi township, frequented by the European population of the quarter but hardly ever by visitors who felt ‘but little inclination to dive into the back streets [of Tawahi] where most of the shops are now established’.Footnote 65 Catering to a captive audience, it was presumable that other merchants could replicate Dinshaw’s success on the Prince of Wales’s Crescent, but a severe shortage of real-estate on the foreshore prevented the development of anything resembling a commercial area. Things changed, however, when the P&O was instructed to vacate the government coal grounds in Steamer Point which had been lying fallow for years, freeing up in the process massive tracts of the foreshore. While negotiations were being held with the company about the possibility of a renewed lease, and as other coaling firms were vying to get their hands on the coveted seafront real estate, a different kind of application was submitted to government by a Parsi merchant named Pallonji Dhanjibhai Patell.

‘Being a permanent resident in this settlement’, the letter read, ‘[I am] desirous of erecting a handsome building on the premises now vacant and lying between custom house and the P&O coal conductors’ quarter at Steamer Point’. Pallonji Dhanjibhai Patell had arrived in Aden in 1864 at the age of eighteen from the village of Siganpore near Surat at the behest of his brother-in-law, Maneckji Ratanji Patell, who himself had been summoned in 1854 to serve as manager to his uncle’s firm. Maneckji afforded Pallonji an education in English and experience running a business in Aden. In 1870, the young Parsi superseded his senior brother-in-law as manager of the firm.Footnote 66 The petition continued:

The ground applied for being vacant for a long time and as your petitioner is given to understand that as not required for any purposes by the government, I will deem it a great boon if sanctioned a small piece. The building of course will be used as a shop and will be such an edifice as will tend to the appearance of the station and also add to the comfort of the officers and gentry.Footnote 67

Pallonji’s request was rejected out of hand, but the ideas enfolded in his application, namely that of increasing fiscal revenue by charging rent on real-estate, began to gain traction in internal correspondence.Footnote 68 ‘It may not be out of place to mention that no ground in an eligible situation is available in the Tawaie [sic, Tawahi] for building purposes’, quoted one such memorandum nearly verbatim, ‘and it will be a great boon to merchants to obtain a piece of land in so favourably situated a locality’.Footnote 69 The incumbent political resident, Francis Loch, believed it was in the public interest to prevent the further stacking of coal on the shore, and inquired whether Bombay held any objection to the ground being let out for building purposes. Not only would the erection of ‘neat shops and dwelling houses’ add greatly to the appearance of the place, Loch reasoned, but there were also attractive fiscal benefits to be obtained by the municipality from renting out such lucrative real estate. The resident concluded by recommending that the land ‘should be no longer allowed to be idle’.Footnote 70 Bombay concurred, and the first building permits were soon issued. In 1879, Pallonji Dhanjibhai Patell opened a shop in partnership with Maneckji Ratanji Patell and Maneckji’s cousin, Dinshaw Muncherji Sopariwalla.Footnote 71

By the early 1880s, the Prince of Wales’s Crescent consisted of ‘some fair-sized stone houses, nearly all double and some treble storied’. A second hotel operated by a Frenchman opened, soon to be followed by several others.Footnote 72 While local and regional commerce took place mainly in the suqs of Crater, the Prince of Wales’s Crescent—or simply ‘The Crescent’, as it came to be known—became the shorefront commercial cynosure of a port now catering to increasing numbers of visitors. The eye-catching, three-storied Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. building emerged as the centrepiece of a handsome block of colonial-style buildings with an adjoining terrace running unbroken throughout its length, in which Parsi merchants were the overwhelmingly dominant element:

We stroll down Aden’s only road to Steamer Point […] and on to the Prince of Wales’ Crescent, a semi-circle of Parsee shops, where so-called curios and European goods are sold at a hundred or so per cent profit […] Of these shops, Cowasfee’s [sic] is perhaps the best, and certainly the most widely known; others are only remarkable for their sameness–Sarabjee, Mucherjee, Pallonjee, Eduljee, and all other ‘jees’ are identical, in their persons, their goods, and their chicanery.Footnote 73

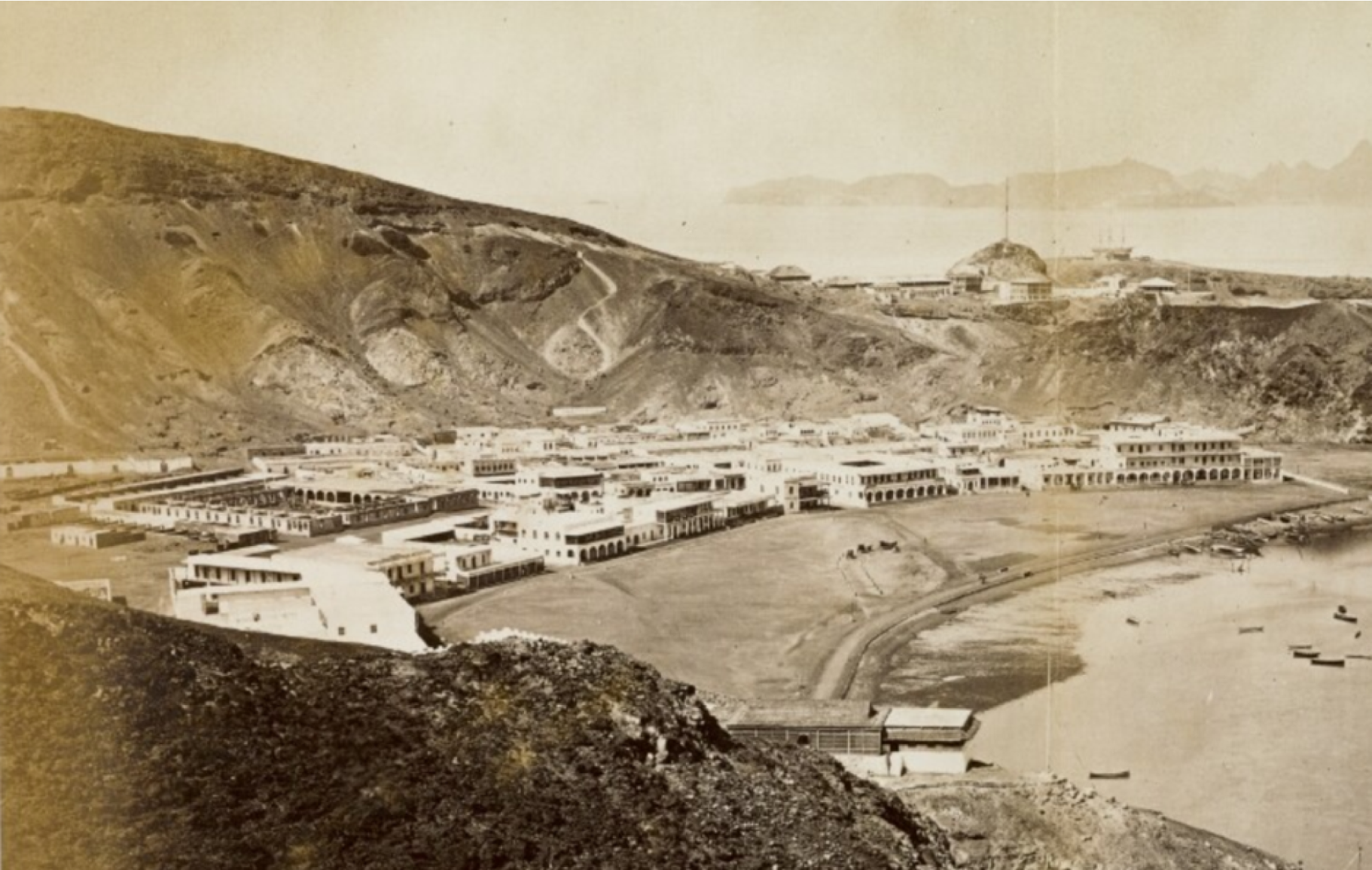

The Crescent. Source: ‘Steamer Point, with Little Aden in the distance’. British Library, India Office Records and Private Papers, Photo 496/10/16

By the turn of the century, luxury cruise ships embarking on round-trip voyages to various exotic ports-of-call became the bon ton for well-to-do people looking to mingle, drink, and eat gourmet meals while traveling to exciting destinations. Now hundreds of tourists at a time, excited by the promise of exotic sights and the prospect of duty-free shopping, found themselves dockside and ready to indulge in anything from discounted liquor to Western consumer goods. With tourism booming, the Crescent was promoted to visitors along a novel line of ‘consumerist orientalism,’ touting Western luxury and consumer goods alongside vignettes of a mysterious, ancient orient. In one tourist brochure, state-of-the-art transistor radios were juxtaposed with the ancient minaret in Crater; gramophones were placed side by side a camel racing scene; and compact, cordless electric shavers embraced a handsome moustachioed, turbaned soldier of the Aden Federal Guard.Footnote 74

‘Map of Aden’. Source: P&O Archive, P&O/89/1. Courtesy of Caird Library, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

More than just a tourist attraction for indulgent Europeans, the Crescent emerged as an important offshore outlet of the western Indian Ocean economy, making industrial consumer goods accessible to Indians travelling westward following partition and the advent of an austere ‘Licence Raj’.Footnote 75 More nefariously, perhaps, Aden served as a key node in a regional trafficking network wherein runners bought beer, whiskey, and other alcoholic beverages in bulk from Parsi retailers to smuggle across the border to Yemen and Saudi Arabia, or to shuttle on dhows across to the Horn of Africa.Footnote 76

But there was nothing self-evident about these later developments. In fact, during the mid-1880s, it was far from clear what role Aden was to play in the future of empire. Technological advancements in shipbuilding coupled with environmental degradation threatened to render its harbour obsolete, throwing into sharp relief the jurisdictional and financial ambiguities of imperial maritime infrastructure. Alongside the risk of ruin, however, the events outlined below presented Aden’s shipping ‘monopolists,’ with Parsis firmly at the helm, a unique opportunity to reshape the port’s institutional landscape to streamline the exigencies of their interests.

‘Shoring up:’ the hydropolitics of the harbour and the formation of the Aden Port Trust

‘There are certainly bigger telegraph offices in the world than this of Aden’, Rihani mused as he stood on the beach at Steamer Point, ‘but they are not more important’. By the 1870s, the empire’s coaling stations had been connected by submarine telegraph cables running the gamut from London to Gibraltar, Malta, Alexandria, and Suez, and from there to Aden and across to Bombay. Soon, a network of such lines connecting Asia and the antipodes with Europe and America converged in Aden, making the station a bastion of global communications without which, as Rihani evocatively put it, ‘the oceans will be plunged again in gloom, distance will revert to its ancient tyranny’.Footnote 77 Aden merchants were now in constant touch with world prices while competitors in other Red Sea ports were deprived of this facility, allowing Aden to reduce neighbouring ports to the position of commercial satellites.

Rapid communication meant Aden’s merchants were infinitely nearer to consumers in Europe and America, a dramatic development owing much of its gravitas to the recent inauguration of the Suez Canal. If ‘no event of the nineteenth century was awaited with such fervent expectation, or celebrated with such drama and enthusiasm’ as the opening of the Suez Canal, in no place around the empire was its inauguration awaited with greater anticipation than in Aden.Footnote 78 The opening of the Canal propelled Aden from a middling imperial outpost to an international transportation hub as the Red Sea, with Aden at its mouth, was transformed from a provincial backwater to a global highway. Throughout the proceeding decades, maritime traffic and trade throughput in Aden increased exponentially,Footnote 79 prompting for the first time the arrival in earnest of European companies to the port, such as the newly formed British India Steam Navigation Company (BI) and bunkering firm Aden Coal Company (ACC).Footnote 80 The good times were shared by all of Aden’s shipping and mercantile community, but no firm or individual could claim to have rivalled the soaring commercial heights attained by the settlement’s most successful businessman, Cowasji Dinshaw.

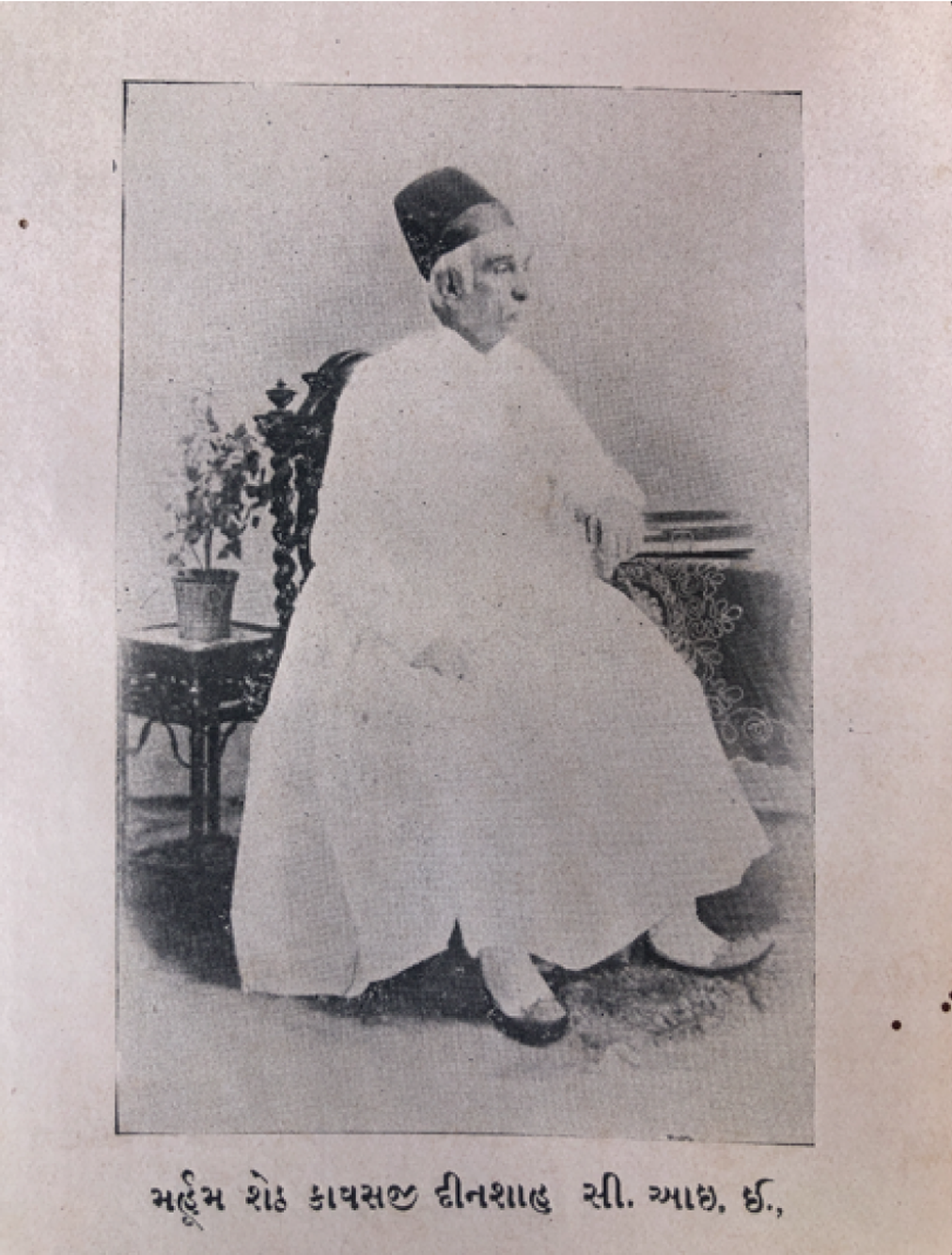

Cowasji Dinshaw Darjina was born to an impecunious family on 14 September 1827. Unlike the urbane Colabawalla or worldly Kharas, Dinshaw was raised in the provincial village of Mandvi near Surat and afforded a rudimentary education in a Gujarati school. Cowasji’s grandfather, Hormusji Rustamji Darjina, left Navsari for Bombay where he presumably worked as a tailor (Gujarati: darjī) for the East India Company; Cowasji’s father, Dinshawji Hormusji Darjina, had come to Aden from Deesa in Gujarat to work as manager of a Parsi provisions shop. After having dropped out of school at sixteen and briefly worked in a Bombay printing press for the unremunerative rate of three rupees per month, Cowasji sailed to Aden at the age of eighteen to join his father as his assistant. His practical education, then, came by dint of closely observing the working of shrewd and often-unscrupulous Parsi merchants and dubashes, before venturing solo in 1850. That year, Dinshaw was appointed dubash for the P&O, the ‘flagship of empire’ whose transoceanic monopoly over mail routes, stretching from Gibraltar to Shanghai, converged in Aden, placing the young Parsi dubash at the heart of an emergent global shipping network.Footnote 81 In 1854, Cowasji summoned his brother, Dorabji, to serve as head-clerk of the P&O offices in Aden and to partner him in an eponymous family firm, Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros.Footnote 82

The young Parsi might have come through the ranks under the wings of his senior co-religionists, but it was his long-lasting, symbiotic relationship with the P&O’s European agent, Captain Luke Thomas, which set his career on course. Over a period of two decades, the enterprising Thomas distinguished himself as the most prominent European entrepreneur in Aden, making several important contributions to the port, such as standardising labour procurement arrangements and erecting the first operative telegraph line, running from Crater to Steamer Point.Footnote 83 Building on the bonds forged on the P&O coal yards, Luke Thomas and Cowasji Dinshaw commenced upon a series of highly successful interlinked enterprises,Footnote 84 venturing aggressively into the private bunkering sector by the end of the 1860s.Footnote 85 When Luke Thomas & Co. was incorporated in London in 1871, the elderly Thomas entrusted the firm’s operations in the hands of its associate firm, Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros.Footnote 86 Dinshaw and Thomas’s fruitful collaboration echoed that of another Anglo-Parsi duo, merchant magnates Jamsetji Jejeebhoy and William Jardine, who for over a decade reigned supreme in the China opium trade.Footnote 87 Like Jejeebhoy and Jardine, Dinshaw and Thomas’s collaboration exemplified imperial trans-communal symbiosis, the Parsi providing access to a range of non-European capital and credit networks while the Englishman brought clout and access to metropolitan circles. Unimpeded by racially inflected glass ceilings, however, Dinshaw was never subordinated to Thomas as might have been the case in other reaches of empire. Having emerged from a crucible of Indian Ocean vernacular capitalism and European business networks, by the last quarter of the century, Cowasji Dinshaw was able to overtake and outstrip all competitors.

Cowasji Dinshaw ‘Adenwalla’, C.I.E. Source: Framroze Ardershir Dadrawala, Dhī Kāwasjī Dīnshāh Senṭīnir Memorial Volyūm (Aden: Messrs. Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. Printing Press, 1927), v

Possessing a keen understanding of the correlation between scale and infrastructure, Dinshaw was quick to exploit opportunities presented by technological changes beyond Aden: the discharge of dated steamships from both private and naval fleets meant that older models could now be obtained by less moneyed firms, enabling Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. to purchase passenger liners and convert them to cargo use.Footnote 88 The firm pioneered subsidiary lines carrying passengers, cargo, and mails to the Hijaz, Hadhramaut, Somaliland, and Zanzibar where regional goods were assembled to be shipped back Aden and transhipped to markets around the world.Footnote 89 Dinshaw erected a private wharf near the company coal yard in Ras Hedjuf equipped with lighters and a large iron warehouse, providing for-profit dockage, lightering, portage, and storage services to local and international shippers and merchants.Footnote 90 By the 1880s, Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. emerged as the leading coal bunkering firm in Aden, selling 60,000 tons of coal per annum, amounting to between fifty and sixty percent of total sales in Aden at the time.Footnote 91 Lauded by supporters as ‘visionary’ and lambasted by detractors as ‘monopolist’, the diversification, feverish expansion, and drive for vertical integration set Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. apart as the largest and most successful firm in the region, standing unrivalled at the commanding heights of Aden’s economy.Footnote 92 However, just when it seemed that the telegraph and the Canal had set Dinshaw and Aden on course to a period of unprecedented boom, the port was rocked by the sudden entrance of a fierce new competitor.

In 1881, a concession was granted to a Liverpool shipping firm to establish a coaling station on the neighbouring island of Perim to rival Aden’s monopoly,Footnote 93 prompting the outbreak of a no-holds-barred commercial war fought with every weapon at the rival ports’ disposal: ship captains were bribed; Aden suspected Perim of falsely notifying a cholera outbreak at Aden, while Perim suspected Aden of bribing its coolies to desert.Footnote 94 A race to the bottom of coal prices proved nearly ruinous for many of Aden’s bunkering firms: in 1884, a year after Perim’s inauguration, ACC’s sales dropped by 30%, while profits plummeted by 59%; a decade later, competition meant sales had halved, but profits bottomed out at remarkable 95% below the 1883 marker.Footnote 95 ACC was sufficiently capitalized to ride out the storm, but other, smaller bunkering firms, such as the Khoja firm of Hajeebhoy Laljee & Co., were not so lucky, forced to fire-sell their assets to remain solvent.Footnote 96 Even Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros. went through a difficult phase, obliged to seek aid from its coaling broker.Footnote 97 The crux of Aden’s malaise, however, lay not simply in direct competition from Perim, but rather in the state of the harbour itself which, like Front Bay forty years prior, was becoming increasingly out of step with international shipping.

From the very inception of steam navigation, the dynamic interaction of ports and ocean-going ships spawned an evolutionary contest leading to increasingly larger steamers, which in turn put more and more strain on port facilities. As the economics of capital-intensive liner shipping required a fast turnaround in port, coaling facilities had to be accommodated in deep and wide basins of quiet water. With advances in iron shipbuilding technologies allowing for greater hulls and deeper draughts, it did not take long until even the best natural harbours of the sailing-ship era were totally inadequate.Footnote 98 Numbers of cases of vessels grounding in Aden had been increasing since the 1850s, and already a decade later, many of the large steamships did not enter the bay at all but instead stood off in the port’s outer harbour, which amounted to little more than an open roadstead separated from the coal yards by two miles of choppy water.Footnote 99 Troublingly for a naval outpost, not only commercial ships but also modern men-of-war could no longer enter the harbour.Footnote 100 To complicate matters further, some concerned officials warned against a dredging scheme, as deepening the harbour would ‘entail the complete nullification’ of Aden’s seaward defences.Footnote 101 With coaling cheaper and more accessible in neighbouring Perim and a degraded harbour undermining its viability as a naval base, Aden’s future seemed shrouded in uncertainty.

Aden’s merchants had petitioned authorities to dredge the harbour already in 1859 but investment was curtailed as the jurisdictional ambiguity of imperial infrastructure engendered a fiery dispute between Bombay, Calcutta, and London over who should foot the bill.Footnote 102 Although formally administered from Bombay, as Aden served the purposes of British rather than Indian foreign policy, and attended to mail steamers plying the vast expanse of the empire, Bombay deemed it unjust ‘to curtail the scanty means’ at its disposal for imperial-scale concerns.Footnote 103 Subsequently, the Government of Bombay suggested to Calcutta that the exchequer might fairly be asked to cover three quarters of the cost, that Bombay should pay one-third of the remaining quarter, and that the Government of India should arrange to defray the balance by assessing the other presidencies, all of whom were directly interested with the efficiency of the harbour, a proposal rejected out of hand by both London and Calcutta.Footnote 104 The fiscal conundrum became entwined in a broader, longstanding debate whether infrastructural sites like Aden should be a British or Indian commitment, but with neither London nor Calcutta inclined to assume financial responsibility, the matter dragged on undecided for decades.Footnote 105 With authorities at an impasse, it was left to the shipping interests in Aden to find a way to break the deadlock, led by the port’s leading merchant-cum-shipping magnate, Cowasji Dinshaw.

A visit in 1884 by the Governor of Bombay provided an occasion for Dinshaw to make a direct plea for the port to be dredged.Footnote 106 When it became clear that action was not forthcoming, Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros., together with the London-headquartered Luke Thomas & Co., organized widespread agitation in Aden, Bombay, Calcutta, and London to force the issue.Footnote 107 Major shipping interests with stakes in Aden were mobilized: the P&O, BI, Lloyds, and over a hundred ship owners representing a million-and-a-half tons of British shipping appealed to the Governor of Bombay and the Secretary of State for India.Footnote 108 Parliamentary questions were tabled, and the Under Secretary of State for India’s unsatisfactory responses were dissected in the Bombay press.Footnote 109

Taking matters into their own hands, Dinshaw’s motley consortium of shipping interests devised a means to break the financial deadlock. They had become privy to the fact that the Aden Port Fund, accumulating the dues collected from shipping, had amassed a substantial surplus which could be directed towards dredging the harbour. A thorough dredging scheme was considered practicable for about £100,000, making the port fund annual surplus, estimated at around £15,000 annually, sufficient to pay interest and sinking fund on a government loan of £100,000, so as to wipe out the principal sum in approximately fifteen years.Footnote 110 The only catch was that, despite its intended function, the Aden Port Fund was regularly subsumed into Bombay’s general budget. The Aden firms thus concentrated on wresting control of these funds from the Bombay government, making their objective the establishment of an independent port trust with business representation on its board to manage the port’s revenues.Footnote 111 In contrast to Bombay’s Parsi and British merchants who in the 1870s vehemently opposed the formation of a port trust that would allow government increased oversight over the port’s trade and revenues, the merchant community of Aden saw in the formation of a trust a means to weaken the government’s hold on its revenues.Footnote 112

Despite initial reluctance by the Government of India, a bill was drafted in Bombay in 1886 to establish a port trust in Aden along the lines of the Karachi Port Trust Bill of the same year.Footnote 113 The bill proved unsatisfactory, however, offering plenty of answers though almost none to the questions posed most urgently by Aden’s shippers and merchants; namely, the bill made no explicit provision that the bar and inner harbour be dredged to such a depth that large vessels could enter and leave at all states of the tide. Bombay was soon flooded with appeals from aggrieved companies and institutions decrying the bill, including petitions from international shipowners frequenting the port, a petition from the merchants of Aden, and a letter from the secretary of the recently formed Aden Chamber of Commerce—the institutional organ of the port’s shipping interests comprised of the so-called shipping ‘monopolists’, marshalled by Cowasji’s eldest son, Hormusji Cowasji Dinshaw.Footnote 114

To make matters worse for Aden’s shipping and coaling agents and private wharf owners, the bill empowered the prospective trust to shut down all private landing places upon completion of the central dredging scheme. The bill further empowered the trust to assume all lightering duties, contract labour, and supply water to shipping, lucrative services which had hitherto been the exclusive remit of the port’s shipping agents and dubash firms. ‘In fact,’ one exasperated opinion-editorial in the Times of India wrote, ‘the object of the bill seems to be to stifle all public enterprise and place the whole trade of the port completely at the mercy of Government by creating a monopoly over which the public will have no control.’Footnote 115 What began as a plea to bring the harbour up to modern standards was quickly turning into a referendum on the future management of the port, pitting public ownership and government oversight against a laissez-faire approach driven by private capital.

The bill was referred to a select committee, where several crucial corrections were proposed in light of structural differences between both the administrative and commercial frameworks of Karachi and Aden. The constitution of an elected board of trustees as in Karachi was deemed inexpedient due to there being no ‘sufficient or appropriate’ body of electors ‘such as a municipality’, and all the more so since the multitude of potentially-electable foreign merchants at the port could undermine the military operations of Aden in times of conflict.Footnote 116 Questionable as these arguments were,Footnote 117 their consequences—that the board would thus be comprised of ex-officio trustees and nominated trustees representing the private sector—held profound consequences for Aden’s future.Footnote 118 By disposing of the notion of franchise, it laid the groundwork for a colonial administrative architecture designed in a way that allowed commercial interests the greatest possible control of its institutions, underpinning a lack of political culture that would come to define the settlement until the 1950s.Footnote 119 In more immediate concerns, the select committee yielded to Aden’s shipping interests, scrapping the idea of public lightering and provisioning, postponing any decision about the closing of private wharves, and foregrounding the dredging of the harbour in the section outlining works to be undertaken upon the trust’s formation.

On 20 December 1888, the Government of Bombay passed the Aden Port Trust Act.Footnote 120 With the establishment of an institution dedicated solely to the harbour’s interests, the impasse was broken; four months later, the Aden Port Trust received charge of all the bunders, wharves, and other property previously under the control of the political resident.Footnote 121 The first dredger purchased by the Aden Port Trust broke ground in 1891, digging out a long, narrow mooring basin the depth of 26 feet at low water, equalling the depth of the Suez Canal. After decades of heated debates and thousands of pages of correspondence exchanged, with the threat of decline looming large, the mobilization of shipping and mercantile interests resulted in the thorough dredging of the harbour which spared Aden from the fate of other ports that had failed to keep up with technological evolution.Footnote 122

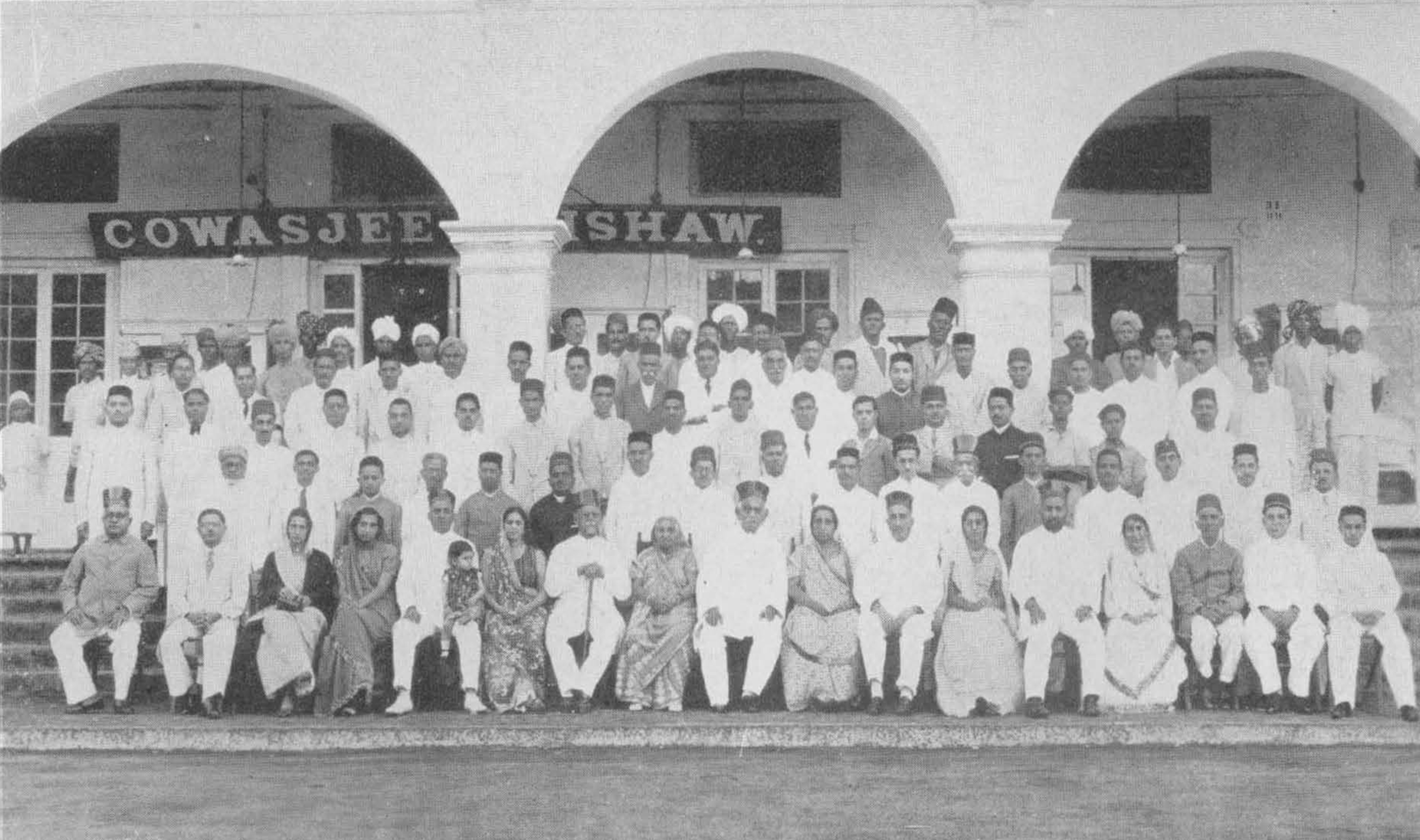

Members and staff of Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros., 1939; Sir Hormusji Cowasji Dinshaw sitting front row center. Source: A.N. Joshi, Life and Times of Sir Hormusjee C. Dinshaw, Kt., O.B.E., K.V.O (Bombay: D.B. Taraporevala Sons & Co.,1939), 75

Crucially, the passing of the act signalled a victory for Aden’s private interests, with Parsis at the helm: a revolving door of ex-officio members (the chairman was changed no less than twenty-five times during the first fifteen years of the trust’s operation) could do little but rubber-stamp the dictates of the shipping magnates, whose paramountcy was buttressed by their longevity. Sir Hormusji Cowasji Dinshaw, Cowasji Dinshaw’s eldest son and the most influential member of the Aden Port Trust, would go on to serve as a trustee for over forty years.Footnote 123 As one worried observer lamented in the Bombay press: ‘What can we expect when the Aden Port Trust really exists to do the bidding of the monopolists, who have so large a share in its control?’Footnote 124 With the formation of the Port Trust, Aden’s shipping interests, spearheaded and directed by Cowasji Dinshaw and his children, were now at the helm of a statutory vehicle allowing them to streamline the exigencies of their interests, formalising together with the Aden Chamber of Commerce (also presided over by Hormusji Cowasji Dinshaw) a nexus which would dominate Aden harbour’s commercial and administrative landscape for over half a century to come.Footnote 125

Conclusions

Political minders lacked the foresight in 1840s to anticipate the import of Aden and its harbour to the empire, but by the time of Ameen Rihani’s visit in 1920, it had become clear that the global circulation of capital and information flows was made possible only through the thrusts of transportation facilitated by the empire’s interconnected maritime footholds, making the political geography of Aden’s harbour synecdochal of the future prospects of empire and of global capitalism itself. As metropolitan investment in Aden was not forthcoming in the period under review, the article has stressed the vitality of Parsi enterprise to the empire during a period when it has often been assumed that native capital was dramatically undermined by the incursion of Europeans into the Indian Ocean arena. Tracing the outsourcing of imperial statecraft to dubashes in Aden thus allows us to provincialize the making of first-wave globalization, as it was predominantly Parsi capitalists rather than European businessmen who were the driving forces of Aden’s development.

Astute dubashes like Edalji Maneckji Colabawalla and Cowasji Dinshaw were quick to identify market needs and bet early on supply-side infrastructure. More than just a local success story, however, the career of a dubash like Colabawalla throws into relief the agency and importance of non-Westerners in shaping global connectivity. Histories of steam-powered globalization have focused on the triumphs of Western industriousness and ingenuity,Footnote 126 yet the dominance of European shipping in the Indian Ocean was largely built upon the groundwork laid by non-Western entrepreneurs like Colabawalla who navigated and adapted challenging environments like Aden, filling supply chain gaps, ensuring the provisioning of essential resources, and speculating on logistics infrastructure.

Building on profits made in the provisions trade, Aden’s most successful firm, Cowasjee Dinshaw & Bros., was crucial in facilitating the circulation of capital across the western Indian Ocean: the firm’s steamers plying the southern Arabian and East African littoral provided ancillary lines linking up with the trunk routes operated by better known European powerhouses like the P&O and BI, while bunkering, provisions, and storage services in Aden kept global capital flows ticking. Operating in a colonial setting subordinated to naval and military needs, however, Cowasji Dinshaw & Bros. did not have the corporate power to traverse ‘the simple logic of the firm’ to assume something akin to economic planning in Aden.Footnote 127 As this article has shown, the prospect of a Port Trust in Aden thus provided a statutory vehicle through which to direct the material development of the harbour and the regulatory landscape of the port, enabling the firm, as the flagbearer of local shipping and mercantile interests, to ensure private capital’s primacy by aligning Aden’s future with its own vision of progress.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the editors at JGH and the journal’s anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Special thanks, too, to Faisal Devji, Gervase Rosser, Fahad Bishara, and Michael O’Sullivan for their academic generosity and insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Itamar Toussia Cohen is a doctoral candidate at the University of Oxford. His dissertation, provisionally titled “Imperial Offshore: Aden and the Infrastructure of Empire, 1817-1971”, focuses on the British colonial port of Aden, which he theorizes as an imperial precursor to infrastructural sites of the modern offshore economy, such as Dubai. More broadly, he is interested in the intersection between Gujarati and other non-Western capital networks, European imperialism, and the history of capitalism in the Indian Ocean world.