INTRODUCTION

Glacier ice is a globally significant reservoir of microorganisms (9.6 × 1025 cells) that are chronologically deposited for hundreds or thousands of years (Priscu and others, Reference Priscu, Christner, Foreman and Royston-Bishop2007). Ice cores drilled from the accumulation zone of glaciers provide a bacterial record in an extreme environment subject to low temperature, low nutrient, high-UV radiation in the surface snow, and darkness below the surface (Christner and others, Reference Christner2000). Bacterial diversity in ice cores has been studied using culture-dependent (Miteva and others, Reference Miteva, Teacher, Sowers and Brenchley2009; An and others, Reference An, Chen, Xiang, Shang and Tian2010; Segawa and others, Reference Segawa, Ushida, Narita, Kanda and Kohshima2010) and culture-independent techniques (Christner and others, Reference Christner2000; Miteva and others, Reference Miteva, Sheridan and Brenchley2004; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Yao, Tian, Xu and An2008b). Descriptions of community compositions, based on bacterial 16S rRNA gene clone libraries, from different ice core locations and layers reflect the surrounding ecosystem, precipitation events, and atmospheric dust (Miteva and others, Reference Miteva, Teacher, Sowers and Brenchley2009; An and others, Reference An, Chen, Xiang, Shang and Tian2010). While culturable bacteria only represent 1% of the total bacterial community, viable bacteria recovered from ice cores also show geographic and seasonal distributions related to climate and the surrounding environment (Christner and others, Reference Christner2000; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Ma, Qin and Chen2007). Both culturable and unculturable bacterial abundance and diversity metrics have utility as possible climate proxies in ice cores (Yao and others, Reference Yao2008; Miteva and others, Reference Miteva, Teacher, Sowers and Brenchley2009; Santibanez and others, Reference Santibanez, McConell and Priscu2016).

Culture-dependent methods are useful techniques for exploring the relationship between bacteria deposited on ice and climatic and environmental change. Between-depth differences in culturable bacteria recovered from glacier ice in the Himalaya, Greenland, and the Muztag Ata Glacier in China were related to past local climate conditions and global atmospheric circulations (Xiang and others, Reference Xiang2005a; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Ma, Qin and Chen2007; Miteva and others, Reference Miteva, Teacher, Sowers and Brenchley2009), demonstrating the linkages between ice-encased bacteria and the environment at the time of deposition. In addition to the environmental importance, the recovery of viable bacteria from ice cores demonstrates that a subset of the total bacterial assemblage preserved in the ice remains viable, and has the potential to reveal previously unknown adaptations for survival in icy environments. However, culturable bacteria from glacial ice have been recovered from fewer than ten ice cores to date around world (Christner and others, Reference Christner2000; Christner and others, Reference Christner, Mosley-Thompson, Thompson and Reeve2003; Miteva and others, Reference Miteva, Sheridan and Brenchley2004; Xiang and others, Reference Xiang2005a; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Ma, Qin and Chen2007; Miteva and others, Reference Miteva, Teacher, Sowers and Brenchley2009; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Yang and Wang2010; Margesin and Miteva, Reference Margesin and Miteva2011; Shen and others, Reference Shen2018). Especially in the Tibetan Plateau (TP) which contains the largest low-latitude glacier-covered area in the world (Qiu, Reference Qiu2008), bacteria have only been isolated from five ice cores (Xiang and others, Reference Xiang2005a; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Ma, Qin and Chen2007; An and others, Reference An, Chen, Xiang, Shang and Tian2010; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Yang and Wang2010; Shen and others, Reference Shen2018). Detected ice core bacteria were dominated by Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes (Shen and others, Reference Shen2018), but the limited number of studies restrict our understanding of the taxonomic biodiversity in glacial ices on the TP. Moreover, the separate studies of culturable bacteria along depth in individual ice cores cannot be used to reveal patterns in bacterial biogeography across the plateau.

Different isolation methods also hinder understanding of the general features of bacteria in ice cores by impeding efforts to compare data across studies. In particular, incubation temperature is an important factor in determining the abundance and diversity of bacteria that can be cultivated. Christner and others (Reference Christner, Mosley-Thompson, Thompson and Reeve2003) incubated paired ice core samples at 4 and 22 °C, and found that incubation at the higher temperature led to the recovery of fewer distinct bacterial types (isolates) than incubation at low temperature, however, once recovered from low temperature incubations, isolates would grow at 22 °C (Christner and others, Reference Christner, Mosley-Thompson, Thompson and Reeve2003). Various incubation temperatures were used in different studies of ice cores in the TP (Xiang and others, Reference Xiang2005a; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Ma, Qin and Chen2007; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Yang and Wang2010), which could lead to differences in the recovered bacteria that were unrelated to the ice cores themselves.

To broadly explore the diversity and distribution patterns of viable bacteria in ice cores, we studied 887 bacterial isolates from seven ice cores and constructed three 16S rRNA clone libraries from three of these ice cores, representing the most intensive study of its kind in the western TP. The seven ice cores were drilled from different geographic and climatic areas of the TP (Fig. 1). Our isolate collection expands the known diversity of culturable bacteria in high-altitude ice cores, and documents their viability at different culturing temperatures. Additionally, by using the culture dependent and independent methods in conjunction, we compare the culturable bacterial diversity of whole ice cores with the community composition revealed by 16S rRNA gene clone libraries.

Fig. 1. Seven ice core sampling sites on the TP, Ulugh Muztagh (MZTG), Muji (MJ), Muztag Ata (MUA), Yuzhufeng (YZF), Geladandong (GLDD), Noijin Kangsang (NJKS), and Zuoqiupu (ZQP). Horizontal and vertical tick marks are latitude and longitude marks, respectively. The gray area in the small inset map shows the location of the TP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ice core sites

Ice cores were collected from seven different glaciers: Ulugh Muztagh (MZTG), Muji (MJ), Muztag Ata (MUA), Yuzhufeng (YZF), Geladandong (GLDD), Noijin Kangsang (NJKS), and Zuoqiupu (ZQP) (Fig. 1), all of which were higher than 5300 m above mean sea level (a.s.l.) (Table 1). MZTG, MJ, and MUA glaciers were located in the alpine desert zone of the western portion of the TP. YZF and GLDD glaciers are surrounded by alpine steppe and desert in the northern part of the TP. NJKS is surrounded by steppe in the southern portion of the plateau while ZQP is near forested area in the southeastern portion of the TP.

Table 1. Description of the ice cores collected and the total number of isolates recovered from each core. The number of samples for each ice core refers to the number of sections cut from each ice core at 5 cm intervals, thus the number of samples varies as a function of ice core length (core depth)

Sampling

Ice cores were drilled from the accumulation zones of the glaciers to depths of 28–164 m (Table 1), and transported frozen to the laboratory. The drill was designed and constructed by the Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Research Institute, CAS. Ice cores with diameters of 7 cm were split lengthwise into four portions for different analyses. One portion was utilized for microbial analysis and cut into 5 cm sections along depth using a bandsaw in a walk-in-freezer (−20 °C). All ice cores were sampled from the top to the bottom. Each sample was decontaminated by cutting away the 1 cm outer annulus with a sterilized sawtooth knife, before rinsing the remaining inner cores with cold ethanol (95%), and finally with cold, triple-autoclaved water (Christner and others, Reference Christner, Mikucki, Foreman, Denson and Priscu2005). The decontaminated ice samples were placed in autoclaved containers and melted at 4 °C.

Enrichment and isolation

In total 489 samples of meltwater from ice cores were used for enrichment and isolation (Table 1). Cultures were named using ice core abbreviation and incubation temperature, followed by an ice core section number, which corresponded with depth of sampling (Table 1). All sections of MZTG4, MJ4, MUA4, GLDD4, YZF4, NJKS4, and all sections of ZQP4 were incubated aerobically at 4 °C. YZF24, NJKS24, and ZQP24 were incubated aerobically at 24 °C. Each isolate and its respective depth of origin are listed in Supplemental Table S1. Cultures were obtained by spreading a 200 µL sample of meltwater directly onto the surface of agar-solidified R2A media (Reasoner and Geldreich, Reference Reasoner and Geldreich1985). The first colonies were visible after 7 d of incubation at 24 °C and 15 d at 4 °C. All samples were incubated for 2 months at 24 °C and 4 months at 4 °C, and checked every 2 weeks for growth. The maximum number of colonies of visibly different morphology (between one and six) were picked from each plate and purified by sub-culturing five to six times on new R2A agar media. The purified isolates were then stored at −80 °C in 30% glycerol solution. As a control, 200 µL deionized sterile water was spread on five R2A plates and incubated at each temperature. No colonies grew on the control plates.

DNA extraction, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, and sequencing of 16S rRNA gene of isolates

Genomic DNA of the 887 isolates obtained was extracted using the phenol/chloroform method (Shen and others, Reference Shen2012). DNA extracted from isolates was used as template to amplify the bacterial 16S rRNA genes. PCR was carried out in a final volume of 50 µL using 2 µL template DNA, 3 µL MgCl2, 4 µL each dNTP, 0.5 µL each primer, and 0.2 µL Taq DNA polymerase, and 35 µL ddH2O using the primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGTTA CCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) (Lane, Reference Lane, Stackebrandt and Goodfellow1991). The PCR cycle included an initial incubation at 94 °C for 5 min, 28 cycles of 94 °C for 0.5 min, 56 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min. The PCR products were purified using an agarose gel DNA purification kit (TaKaRa Co., Dalian, China), and then partially sequenced directly off of the primers (1492R, 43 isolates in YZF; 27F, 844 isolates) with BigDye terminator v3.1 chemistry on an ABI PRISM 377-96 sequencer.

DNA EXTRACTION, PCR AMPLIFICATION, AND 16S RRNA GENE CLONE LIBRARY CONSTRUCTION FROM BULK MELTWATER

Approximately 2 L of meltwater was collected from each of the entire length of the ice core YZF, NJKS, and ZQP ice cores, and filtered through a 0.22 µm filter (Millipore). DNA was extracted from the filters using phenol–chloroform method (Kan and others, Reference Kan, Crump, Wang and Chen2006). To assess if contamination was introduced during DNA extraction, a negative parallel control was established by filtering 2 L of autoclaved deionized water using the same method as described above. DNA preparations from both the sample and negative control were used as templates to amplify the bacterial 16S rRNA genes with the universal primer pair 27F and 1492R (Lane, Reference Lane, Stackebrandt and Goodfellow1991). The PCR program was as follows: after an initial incubation at 94 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles were run at 94 °C for 1 min, 56 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1.5 min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min.

The PCR products were purified using an agarose gel DNA purification kit (TaKaRa Co., Dalian, China), ligated into pGEM-T vector (TaKaRa Co., Dalian, China), and then transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α. The presence of inserts was checked by colony PCR. In total 150, 110, and 110 clones in YZF, NJKS, and ZQP were selected for sequencing, respectively.

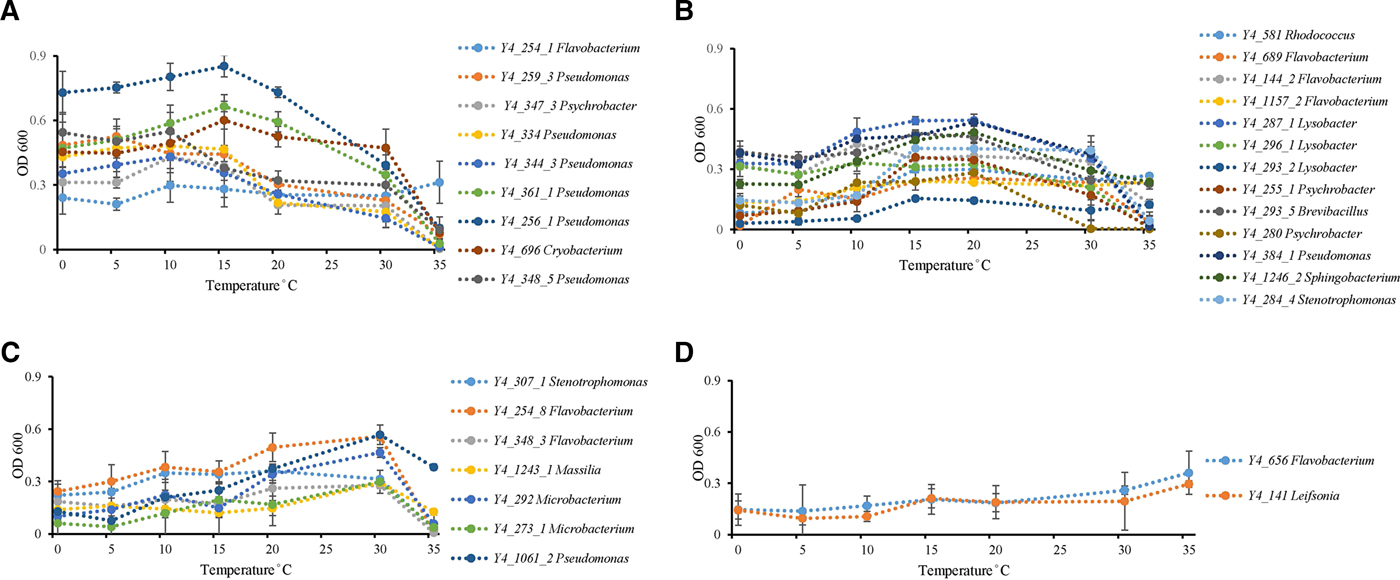

Growth at different temperatures

The growth of 32 isolates of different morphological groups from YZF4 was tested in R2A liquid media at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 35 °C. The 32 isolates consisted of: eight Pseudomonas; seven Flavobacterium; three Lysobacter and Psychrobacter, two Cryobacterium, Microbacterium, and Stenotrophomona; and one each from Dyadobacter, Leifsonia, Rhodococcus, Sphingobacterium, and Massilia. Cultures were measured using the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) after obvious growth was observed in most samples. All isolates were grown and measured in triplicate.

Phylogenetic analysis

16S rRNA gene sequences were aligned at the genus level against the SILVA reference database (Pruesse and others, Reference Pruesse2007). All sequences obtained from the clone library were examined for chimeric artifacts using the Pintail tool (http://www.bioinformatics-toolkit.org). Clones identified as potential chimeras were discarded. To determine the isolates’ closest officially named phylogenetic neighbors initial identification was carried out using BLASTn (Altschul and others, Reference Altschul1997) against the database containing type strains with validly published prokaryotic names (the EzTaxon-e server; http://eztaxon-e.ezbiocloud.net/) (Kim and others, Reference Kim2012). The closest sequences and the associated environment from which the sequence was recovered were retrieved from the NCBI (http://www.ncbi.cih.gov) using BLASTn.

Statistical analysis

Coverage of clone libraries was calculated using the equation: Coverage = [1 − (N/Individuals)] × 100%, where N is the number of clones that occurred only once (Kemp and Aller, Reference Kemp and Aller2004). Comparisons of isolate assemblages from 4 and 24 °C were conducted by pooling together the data from all depths of each ice core. Analyses of similarity (ANOSIM) were performed using PAST (Hammer and others, Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2001) to determine the differences among bacterial assemblages derived from 4 and 24 °C incubations and clone libraries. Distribution patterns of isolates and clone sequences were analyzed using non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity. Analyses were carried out with R v2.14 (Wood, Reference Wood2006) with the packages vegan (Oksanen and others, Reference Oksanen2009) and gplot (Warnes and others, Reference Warnes, Bolker and Lumley2009).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The nucleotide sequences of partial 16S rRNA genes have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers KF294941–KF295827 for isolates and KX119594–KX119940 for clones. All 887 isolates were stored at −80 °C in 30% glycerol solution at the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, CAS, and are available for any study on request.

RESULTS

We isolated 887 bacterial strains from different depths in seven ice cores from the TP (total sample n = 506; Supplemental Table S1). The isolates were affiliated with six groups. Actinobacteria and Firmicutes were the most abundant, accounting for 21% of total isolates, followed by Bacteroidetes (16%), γ-Proteobacteria (16%), β-Proteobacteria (14%), and α-Proteobacteria (13%).

All isolates were classified into 53 genera. Genera containing isolates that contributed ⩾10% of the total number of isolates were labeled as ‘abundant’, while those that were less abundant (<5%), but found in greater than or equal to four ice cores, were labeled as ‘common’. Isolates affiliated with the genera Bacillus (Firmicutes), Flavobacterium (Bacteroidetes), and Pseudomonas (γ-Proteobacteria) were the most abundant across all samples, accounting for 14, 12, and 10% of total isolates (the abundant group). Isolates in the genera Arthrobacter, Microbacterium, and Rhodococcus (Actinobacteria); Brevundimonas and Sphingomonas (α-Proteobacteria); and Polaromonas and Massilia (β-Proteobacteria) were less abundant, accounting for <5% of total isolates, but were commonly found across samples from four to seven ice cores (common group). Isolates in genera Cryobacterium, Paenisporosarcina, and Burkholderia accounted for 5–7% of total isolates, but dominated in only one or two ice cores (NJKS and YZF, GLDD and MZTG, or ZQP, respectively; Table 2), and were therefore neither common, nor abundant. In sum, these 13 genera contained 78% of all isolates. The other 40 genera existed in one or two ice cores, accounted for <5% of all isolates and were considered ‘rare’ (Supplemental Table S1).

Table 2. Isolates in 13 major genera which accounted for 78% of total strains. Percentages refer to the percentage of total isolates

There were no marked geographic differences in the taxon composition from the northern (MZTG, MJ, and MU) and southern (GLDD, YZF, NJKS, and ZQP) regions of the TP (t test, P > 0.01). Isolates from different depths, however, showed differences in diversity and represented genera. To avoid characterizing samples based on rare isolates, we focused on genera represented by more than five isolates. The shallower depths of the ice cores (0–40 m) yielded the greatest diversity of isolates, covering 18 different genera, while isolates from the mid-depths (40–80 m) represented five genera, with only a single genus (Sporosarcina) recovered below 80 m (Table 3). Isolates from the genus Bacillus were present at all depths <100 m, and were the sole genus represented from 80 to 100 m, while isolates of the genus Sporosarcina were the only genus recovered from depths >100 m (Table 3). Besides genus Bacillus, isolates in the genera Flavobacterium, Pseudomonas, and Brevundimonas were obtained from ice 40–80 m (Table 3).

Table 3. Distribution of isolated genera along depth. No. represents number of isolates in each genus. Only genera containing more than five isolates are shown

Isolates from our ice cores were identified based on 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity to published type strains in the EZTAXON database. Similarity ranged from 90 to 100%, with 12% of total isolates <97% similar to the published type strains. These <97% similar isolates are potential novel species (Stackebrandt and Goebel, Reference Stackebrandt and Goebel1994). When queried against the NCBI database, our isolates matched cultured or uncultured bacterial clones from a wide variety of environments with 95–100% similarity. Forty-two percent of these nearest relatives were recovered from the cryosphere, i.e. snow, glacier, permafrost, Arctic, and Antarctica, while 27, 14, and 7% were also found in soil, aquatic (marine, lake, river, and cold spring), and plant-associated environments, respectively. The other 10% were previously found in air, animal, and other environments (i.e. aviation kerosene, activated sludge, drinking water, and volcanic ash; Supplemental Table S1). The genera Cryobacterium, Polaromonas, Flavobacterium, and Paenisporosarcina were dominated (100, 93, 85, and 70% of all strains in each genus, respectively) by isolates related to organisms or clones from the cryosphere. Strains in the genera Arthrobacter, Microbacterium, Bacillus, Burkholderia, Brevundimonas, Sphingomonas, Massilia, and Pseudomonas were mostly (60–99%) related to soil, plant, aquatic, and other environments (Table 4, Supplemental Table S1).

Table 4. The source environments for the closest relatives of the 13 major genera recovered from ice cores sampled in this study. Closest relatives were determined as those with 99% similarity in the NCBI database using BLASTn

Temperature incubation experiments showed that ice core isolates possess the ability to grow at wide temperature ranges. Twenty-six strains grew from 0 to 35 °C, while the other six strains grew from 0 to 30 °C. Psychrophilic bacteria are defined as those with optimal growth temperature at or below 15 °C and no growth occurring at 20 °C, while psychrotolerant bacterial have an optimal growth temperature higher than 20 °C with growth occurring down to 4 °C (Bowman and others, Reference Bowman, McCammon, Brown, Nichols and McMeekin1997). All strains could be identified as possessing psychrotolerant growth characteristics, but none of the strains displayed psychrophilic growth (Bowman and others, Reference Bowman, McCammon, Brown, Nichols and McMeekin1997) characteristics (Fig. 2). Thirty-one percent of all isolates (ten strains) had optimum growth temperatures ⩽15 °C (Fig. 2a). Thirteen strains had an optimum growth temperature between 15 and 20 °C (Fig. 2b). The other nine isolates grew at low temperatures, so could not be classified as mesophiles, but had optimum growth temperatures of 30 (Fig. 2c) to 35 °C (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2. Temperature effect on growth of ice core isolates. (A) Optimum growth temperatures were 15 °C or under 15 °C (strain Y4_254_1 in genus Flavobacterium; strains Y4_259_3, Y4_259_3, Y4_334, Y4_344_3, Y4_361_1, Y4_256_1, and Y4_348_5 in genus Pseudomonas; strain Y4_347_3 in genus Psychrobacter; and strain Y4_696 in genus Cryobacterium). (B) Optimum growth temperatures were 15 and 20 °C (strain Y4_581 in genus Rhodococcus; strains Y4_689, Y4_144_2, and Y4_1157_2 in genus Flavobacterium; strains Y4_287_1, Y4_296_1, and Y4_293_2 in genus Lysobacter; strains Y4_255_1 and Y4_280 in genus Psychrobacter; strain Y4_293_5 in genus Brevibacillus; strain Y4_384_1 in genus Pseudomonas; strain Y4_1246_2 in genus Sphingobacterium; strain Y4_284_4 in genus Stenotrophomonas). (C) Optimum growth temperatures was 30 °C (strain Y4_307_1 in genus Stenotrophomonas; strains Y4_254_8 and Y4_348_3 in genus Flavobacterium; strain Y4_1243_1 in genus Massilia; strains Y4_292 and Y4_273_1 in genus Microbacterium; strain Y4_1061_2 in genus Pseudomonas). (D) Optimum growth temperatures were higher than 30 °C (strain Y4_656 in genus Flavobacterium; strain Y4_141 in genus Leifsonia). Different colors refer to different strains.

After quality checking and removal of chimeric sequences, a total of 347 16S rRNA sequences were obtained from the clone library, 98 in YZF, 142 in NJKS, and 107 in ZQP. Coverage of YZF, NJKS, and ZQP libraries were 82, 65, and 73%, respectively. The genera Cryobacterium (30%) and Flavobacterium (23%) were dominant in YZF, while Polaromonas, Cryobacterium, and Flavobacterium dominated in NJKS (40% of total sequences). Clones related to two unclassified genera in Microbacteriaceae represented 43% of all clones recovered from ZQP.

The collection of isolates recovered from 4 and 24 °C incubations of YZF, NJKS, and ZQP had differing composition (Fig. 3). At the genus level, isolate compositions from all seven ice cores were grouped based on different incubation temperatures (Fig. 4, Bray–Curtis similarity). Isolate compositions of YZF, NJKS, and ZQP from 24 °C incubation were separated from similar ice core samples incubated at 4 °C, isolates from six ice cores from the current study and incubated at 4 °C grouped with isolates recovered at 4 °C from Tibetan Puruogangri (Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Yao, Tian, Xu and An2008b) and Muzitage Ata (Xiang and others, Reference Xiang, Yao, An, Xu and Wang2005b) ice cores. Isolates recovered from 4 °C incubation also grouped together with bacterial composition from clone libraries of YZF and NJKS. Isolate compositions recovered from 4 °C incubation were similar to bacterial composition from clone libraries, but significantly different (ANOSIM, P < 0.001) from isolate compositions recovered 24 °C incubation (Table 5). The difference between isolate compositions recovered from 24 °C incubation and bacterial composition from clone libraries was significant (ANOSIM, P < 0.001; Table 4).

Fig. 3. Relative abundance of isolates recovered from culturing at 4 and 24 °C, and of sequences in 16S rRNA clone libraries. MZTG4, MJ4, MUA4, GLDD4, YZF4, NJKS4, and ZQP4 were incubated aerobically at 4 °C. YZF24, NJKS24, and ZQP24 were incubated aerobically at 24 °C. NJKSC, YZFC, and ZQPC were 16S rRNA clone libraries.

Fig. 4. nMDS analysis of the 887 isolates obtained in this study, 244 isolates from other TP ice cores (RBL, ERB1, ERB2, Puruogangri, Muzitage) (Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Ma, Qin and Chen2007, Reference Zhang, Hou, Wu and Qin2008a, Reference Zhang, Yao, Tian, Xu and Anb; An and others, Reference An, Chen, Xiang, Shang and Tian2010; Shen and others, Reference Shen2012), and YZF, NJKS, and ZQP clone libraries (YZFC, NJKSC, and ZQPC). The red circles indicate isolates incubated at 24 °C, and the black circles indicate isolates and clone libraries derived from 4 °C incubations, except for ZQP, which did not group with the other isolates and clone libraries.

Table 5. Assemblages dissimilarity test based on one-way ANOSIM using Bray–Curtis distance. Values in boldface indicate significant differences (P < 0.05, sequential Bonferroni-corrected) among isolate compositions recovered from 4 and 24 °C incubations and bacterial composition from clone libraries

DISCUSSION

More than 800 isolates belonging to 53 genera were cultured from seven different ice cores collected from the TP. The isolates typify diverse culturable bacteria from different sources in high-altitude glaciers. The 13 major genera, which accounted for 78% of strains, occurred in ice cores located across geographic zones, from dry alpine desert (MZTG) to forest (ZQP). All of these genera were previously found in glacier ice in the TP, the Arctic, and the Antarctic (Christner and others, Reference Christner2000; Miteva and others, Reference Miteva, Sheridan and Brenchley2004; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Wu and Qin2008a, Reference Zhang, Yao, Tian, Xu and Anb). Half of abundant and common genera included strains most closely related to those from cold environments (Table 4). The relationship between our isolates and those from other ice core studies (Christner and others, Reference Christner, Mosley-Thompson, Thompson and Reeve2003; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Yao, Tian, Xu and An2008b, Reference Zhang, Hou, Yang and Wang2010; Miteva and others, Reference Miteva, Teacher, Sowers and Brenchley2009) corroborates the findings of Christner and others (Reference Christner2000) that these cryosphere-related bacteria are widely distributed and may possess physiological mechanisms that confer resistance to atmospheric transport (i.e. high-UV irradiance) and freezing.

The abundant genera Bacillus, Flavobacterium, and Pseudomonas showed the widest distribution and highest abundance in Tibetan ice cores. These three genera are also the most commonly cultivated genera in cloud water which indicates that these genera remain viable during transport in the atmosphere, where they are subjected to strong selection pressures (Amato and others, Reference Amato2005; Amato and others, Reference Amato2007). The genus Bacillus widely exists in soil and water, and their endospore-forming ability has been reported as a strategy to endure freezing in glacial ice (Christner and others, Reference Christner2000). Most of the strains (62%) in the common genera (mainly those from the Actinobacteria and the Alphaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria), were related to soil, aquatic, plant, and other environments (Table 4) indicating widespread and heterogeneous sources that may encompass selection pressures that differ from the abundant group.

The genera Cryobacterium, Paenisporosarcina, and Burkholderia were present in certain Tibetan ice cores (NJKS and YZF, GLDD and MZTG, ZQP, respectively) but were not widespread, which suggests a signature from the local environment around each glacier. The mainly plant-associated genus Burkholderia (Estrada-De Los Santos and others, Reference Estrada-De Los Santos, Bustillos-Cristales and Caballero-Mellado2001), for example, was only present in the ZQP ice core, which is surrounded by alpine forest.

The number of genera represented by more than five isolates sharply decreased with depth (Table 3). Three abundant genera (Bacillus, Flavobacterium, and Pseudomonas) showed relatively deep distribution, to depths of 80 m. Sporosarcina, the dominant genus found in the deep ice samples (>100 m) has been reported in various icy environments (glacier, snow, and frozen soil from alpine, Arctic, and Antarctic) (Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Wu and Qin2008a, Reference Zhang, Yao, Tian, Xu and Anb; Shivaji and others, Reference Shivaji2013; Zdanowski and others, Reference Zdanowski2013; Yadav and others, Reference Yadav2015). Previous studies found that numbers of recoverable bacteria did not correlate directly with the age of the ice from 5 to 20 000 years old (Christner and others, Reference Christner, Mikucki, Foreman, Denson and Priscu2005). In 22 and 84 m long ice cores, bacterial isolates were layered, with different groups dominating along a depth gradient (Xiang and others, Reference Xiang, Yao, An, Xu and Wang2005b; Zhang and others, Reference Zhang, Hou, Wu and Qin2008a, Reference Zhang, Yao, Tian, Xu and Anb). Our study is the first to clearly show differences in dominant genera of culturable bacteria from the shallow and deep parts of ice cores. These differences should reflect either the influence of in situ processes on bacterial communities post-deposition, initial inputs of different bacterial communities at different times, or a combination of both. While bacteria may metabolize in situ in some ice environments, the rates of metabolism are extremely low (e.g. Tung and others, Reference Tung, Price, Bramall and Vrdoljak2006), making it unlikely that a clearly detectable turnover between phylotypes would occur during the period of encasement in our study. We cannot, however, rule out the loss of phylotypes less tolerant of encasement.

Growth in a wide temperature range is likely a general survival strategy for bacteria encased in glacier ice. Ice core bacteria are transported from local or distant sources, depending on prevailing atmospheric circulation patterns. During transport, bacteria must endure temperature changes between the source environment and the glacier, either through broad tolerances of vegetative cells, spore formation, or other physiological modifications. All isolates tested in this study grew in a wide range of temperatures from 0 to 35 °C, had optimal growth temperatures of 10, 15, and 20 °C, and each isolate grew both at low temperature (0 and 4 °C) and high temperature (30 and 35 °C). Snow bacteria isolated from the surface of glaciers have been found to have a wider growth temperature range, when compared with cultured representatives of the same species (Shen and others, Reference Shen2014). In addition to our isolates from YZF ice core, bacteria from Guliya, Muztag Ata, Greenland, and Antarctic ice cores also grew in a wide temperature range (Christner, Reference Christner2002; Miteva and others, Reference Miteva, Sheridan and Brenchley2004; Xiang and others, Reference Xiang, Yao, An, Xu and Wang2005b). These previous data, in combination with our data, show that wide growth temperature range is common among glacier-associated bacteria. While the previous studies focused on bacteria isolated from the surface of glaciers, our data show wide temperature adaptation in bacteria from all depths of the ice cores. Hence, we conclude that adaptation to broad temperature ranges is an important strategy for surviving the transition from source habitat to glacier ice.

Incubation temperature had an impact on the isolate assemblage recovered from a given ice core. Incubation temperature was a stronger driver of isolate assemblage than geographic location (Fig. 4), similar to results from glaciers in Western China (An and others, Reference An, Chen, Xiang, Shang and Tian2010). Incubation at 4 and 24 °C recovered different isolates from the same ice core (Fig. 3). The endospore-forming genus Bacillus dominated the 24 °C incubation while the psychrotolerant genus Cryobacterium dominated the 4 °C incubations from NJKS and YZF (Table 2). Previous studies suggested that incubation in low temperature obtain relatively more diverse bacteria in ice (Christner, Reference Christner2002), implying that bacteria in ice are better adapted to low temperature. Bacterial assemblage determined via culture-independent molecular methods were statistically more similar to the culturable bacteria from the 4 °C incubations than the culturable bacteria obtained from the 24 °C incubations (Table 5). Dominant genera found in clone libraries were also recovered in 4 °C incubations, such as Cryobacterium and Flavobacterium. However, the genus Burkholderia which was abundant in culturable organisms, but not detected in the clone library from ZQP, indicating the potential biases of culture-dependent methods and molecular methods. In particular, the relatively low coverage of three clone libraries (82, 65, and 73%) may have limited the recovery of some potentially important clones. In spite of this, our results show that glacial ice contains diverse bacteria that can be revived after decades or centuries immured in ice. Further, the ice-associated bacteria identified in this study are capable of surviving at a wide range of temperatures, which suggests that temperature tolerance provides an important adaptive advantage to bacteria during atmospheric transport and deposition on ice. These new insights into the survival of cryosphere-associated bacteria highlight the importance of icy environments as refugia for microorganisms during periods of glaciation.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2018.86

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was financially supported by the International Partnership Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 131C11KYSB20160061), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41425004 and 41701085), and the National Basic Research Program of China (Grant No. 2015FY110100). The authors thank two reviewers and the editor Dr Tranter for their constructive comments.