1. Introduction

Namibia—previously German South-West Africa/Deutsch-Südwestafrika —is one of four former German colonies on the African continent. Unlike the other three—German East Africa, Togoland, and German Cameroon—it is the only former German colony in Africa in which relatively large numbers of Germans settled and in which the German language continues till today to hold a special status within the country.

From a linguistic standpoint, the German spoken in Namibia (Namibian German, henceforth NG) presents an interesting case. It has been successfully maintained and used across generations for over a century in both formal and informal settings, and today it continues to be linguistically vital and strongly supported by the local German-speaking community.Footnote 1 This makes it different from many of the extraterritorial German varieties spoken by the descendants of immigrants from Central Europe, which are moribund today (such as Texas German), including other colonial varieties (such as Unserdeutsch). Instead, NG is more similar to extraterritorial varieties that are still acquired natively by children, including those of sectarian communities, such as Mennonite Low German in multiple Latin American countries, especially Paraguay, Bolivia, and Mexico, as well as in Russia (Siemens Reference Siemens2018), and Pennsylvania German, Hutterite German, Amish Alsatian German, and Amish Swiss German in the US and Canada (Louden Reference Louden, Michael and Richard Page2020). However, what sets NG apart from most varieties of German is that its use is actively supported in various public domains due its status as one of 13 national languages of Namibia (Shah & Zappen-Thomson Reference Shah, Zappen-Thomson, Corinne and Shah2017). Speakers are typically trilingual and habitually speak at least Afrikaans and English, besides German (Wiese et al. Reference Wiese, Simon, Zimmer and Schumann2017).

(Standard) NG, especially when compared to extraterritorial varieties in other parts of the world, can be described as being relatively close to Standard German (henceforth SG). In general, during their initial interaction with local German-speaking Namibians, German visitors to Namibia do not notice anything too unusual in their speech, except for lexical peculiarities. For a long time, linguists, too, focused on its lexical peculiarities and described the ways in which NG lexicon differed from SG lexicon (see, among others, Nöckler Reference Nöckler1963 and Böhm Reference Böhm2003).Footnote 2 In contrast, its pronunciation and grammar were (erroneously) considered to approximate that of SG (see, among others, Böhm Reference Böhm2003:565), which led to the perception that it was less interesting from a variationist perspective than many other German varieties. However, in more recent years, more attention has been paid to other—mainly morphological and syntactic—standard-divergent features.Footnote 3 Much of the recent work is based on a systematically compiled corpus, Deutsch in Namibia (DNam, German in Namibia; Zimmer et al. Reference Zimmer, Heike Wiese, Simon, Bracke, Stuhl and Schmidt2020a,b), which constitutes a valuable resource for the research community and provides a means to better understand many of the intricacies of German within the multilingual context of Namibia.

Our aim in this paper is to provide a deeper insight into the dynamics of German in multilingual Namibia. To that end, we focus on two features, namely, the expanded use of linking elements and of gehen as a future auxiliary, and explore in depth various factors that potentially could have contributed to their emergence. The structure of the paper is as follows: First, we present an overview of the history of German and Germans in Namibia (section 2), followed by a discussion of the current sociolinguistic setting in which both the language and its speakers find themselves (section 3). Second, we focus on two grammatical innovations in NG: the expanded use of linking elements (section 4) and of gehen as a future auxiliary (section 5), and investigate their use in present-day NG via a questionnaire study. Section 6 is a conclusion.

2. Historical Background

The first Germans to arrive to the territory of today’s Namibia were missionaries.Footnote 4 In 1806, Christian and Abraham Albrecht, two German brothers working for the London Missionary Society (LMS), established the first Christian mission in southern Namibia. They were followed by LMS missionary Johann Heinrich Schmelen, who founded a mission station in Bethanien (Kube & Kotze Reference Kube and Kotze2002:258–259). In 1842, the Rhenish Missionary Society (RMS), one of the largest German missionary societies and the main missionary society in Namibia until the early 1900s (Ryland Reference Ryland2013), established its first mission in the country. Over the years, more missions were established by the RMS, totaling 18 by 1900 (Weigend Reference Weigend1985:160). Although missionaries did not permanently settle in Namibia, they played an important role in attracting other, more permanent German settlers (Weigend Reference Weigend1985:160) and in spreading the German language among the local black population. The latter was mainly achieved through the instruction of German as a foreign language in the Rhenish missionary schools and through the introduction of German as the medium of instruction at the Catholic mission stations (Zappen-Thomson Reference Zappen-Thomson2000:68–69).

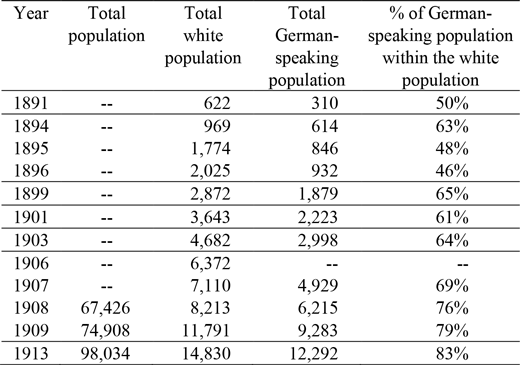

A significant growth in the German-speaking population in Namibia took place during the colonial period of the German Empire (Deutsches Kaiserreich). Between 1884 and 1915, Namibia—or German South-West Africa, as the territory was then officially known—was under German colonial rule. Unlike most other former German colonies, which were viewed simply as exploitation colonies, Namibia was perceived as a preferred settler colony due to, among other factors, its climate, size of the country, low population density, and its relative proximity to Central Europe (as opposed to, for example, former German colonies in Melanesia; Ammon Reference Ammon2015:359). Between 1891 and 1913, both the German-speaking population and the proportion of Germans within the white population steadily increased (see table 1). This was a result of a “deliberate settlement policy” (Deumert Reference Deumert2009:356) of the German Empire to reinforce German colonial interests (Walther Reference Walther2002:10).Footnote 5

Table 1. Number of German speakers within the white population in Namibia, 1891–1913.

The composition of the Namibian population changed significantly during the colonial period, and specifically during the tragic Herero and Nama War (1904–1908), today recognized as a genocide (Zimmerer Reference Zimmerer and Stone2008:323):Footnote 6

[T]he German colonial army deliberately killed thousands of Herero and Nama men, women and children; let even more die of thirst in the Omaheke desert; and murdered thousands more by deliberate neglect in concentration camps.

This colonial genocide led to the deaths of an estimated 80% of the Herero population and a third of the Nama population.

Unlike some of the other groups of early German settlers outside Namibia whose origins for the most part can generally be pinpointed to specific dialect areas (for example, southwestern regions of the German-speaking area for Pennsylvania Dutch speakers, see Louden Reference Louden2016; and northern Germany for Springbok German speakers, see Franke Reference Franke2008), the original colonists who migrated to Namibia came from all over German-speaking Europe and therefore did not bring along a common dialect into the new settlement area (Shah Reference Shah2007:23, Zimmer Reference Zimmer2021c).Footnote 7 The mixture of different dialects triggered several developments that have been extensively described in the literature on dialect contact and new-dialect formation (see, among others, Trudgill Reference Trudgill1986, Reference Trudgill2004; Kerswill & Trudgill Reference Kerswill, Trudgill, Auer, Hinskens and Kerswill2005), such as leveling, interdialect formation, reallocation, and focusing (Zimmer Reference Zimmer2021c). In these processes, variants from the most northern parts of the German-speaking area in Europe played an important role as large numbers of colonists came from these (Low German dialect) areas (Nöckler Reference Nöckler1963:18, Böhm Reference Böhm2003:564, Zimmer Reference Zimmer2021b,c).

The colonists settled mainly in the southern and central regions of Namibia; in the northern region, the German colonial administration exerted indirect control (Deumert Reference Deumert2009:356). From the onset, the German colonists established various German-speaking institutions, among them German print media, schools, churches, and various cultural, social, and sports clubs; some of these early institutions are still operating today (Shah & Zappen-Thomson Reference Shah, Zappen-Thomson, Corinne and Shah2017). These institutions served not only to promote the German language, but also to create a sense of belonging by fostering Deutschtum ‘Germanness’ (Walther Reference Walther2002).

During the colonial period, German was the sole official language of the territory. Despite this special status, it was not spoken by the majority of the population; instead, Cape-Hollandic/Cape Dutch (later, Afrikaans) was the lingua franca (Gretschel Reference Gretschel1995:300).

In 1915, with the occupation of Namibia by the South African Union troops, the German colonial rule ended. From 1919 onward, following the signing of the Peace Treaty of Versailles (Article 119), Namibia was administered by South Africa under a C-class mandate granted by the League of Nations. Large numbers of Germans were forced to leave Namibia during this period. In the year 1919 alone, 6,374 Germans were deported to Central Europe, leaving only about 6,700 Germans in the country (Kube & Kotze Reference Kube and Kotze2002:283). In 1920, German ceased to be the official language of the territory and was replaced by Dutch (later Afrikaans) and English. Nonetheless, through successful lobbying by the German-speaking community, German remained in a privileged position and continued to be used as the language of instruction in German medium schools in Namibia and as a working language of the government.Footnote 8

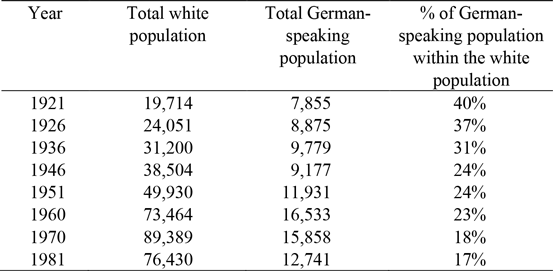

The deportation of almost half of the German population in 1919 and a drastic decline in the number of Germans migrating to Namibia during this period resulted in a decrease in the percentage of Germans within the increasing white, mainly Afrikaner, population from 83% of the total white population in 1913 to 40% in 1921 and 31% in 1936 (see table 2).Footnote 9

Table 2. German population statistics in Namibia, 1921–1981 (Bähr Reference Bähr1989:100).

With the outbreak of World War 2 and following South Africa’s decision to enter the war and support Britain’s war efforts, many German males were arrested and initially detained in the Klein Danzig internment camp in Windhoek, but later transferred to internment camps in South Africa. Further detainments took place in 1940. Andalusia near Kimberly had the largest number of internees (1,220 Germans by the end of 1940; Lunderstedt Reference Lunderstedt2016); other internment camps included Baviaanspoort (near Pretoria) and Koffiefontein (near Kimberly). The interned Germans were only released in 1946 and were allowed to return home the following year. In the late 1940s, the German community in Namibia began to grow again, although their proportion among the white population continued to steadily decline during this period (see table 2).

From 1948, following the election victory of the National Party in South Africa, South African apartheid laws were extended to the territory of Namibia. This system of institutionalized racial segregation implemented by a white minority apartheid regime existed until the early 1990s. During this time, Afrikaans continued to be systematically promoted by the administration and was not only the dominant language used in various domains (such as government, education, etc.), but also served as a lingua franca for interethnic communication (Harlech-Jones Reference Harlech-Jones1995). For many decades, the German-speaking community unsuccess-fully sought to improve the status of German in Namibia. Only in 1984 was German elevated to an official language, serving as the third official language within the Administration for Whites (Gretschel Reference Gretschel1995:303), the other two being English and Afrikaans, which were official languages on the national level. In 1990, when Namibia gained independence, English became the sole official language of the country and German was recognized as one of 13 national languages.

Since Namibia gained independence in 1990, the German-speaking population in Namibia has been hovering around 1% of the total Namibian population (see table 3).Footnote 10 Today, about 15,000–20,000 Namibians have German as their L1.

Table 3. German population statistics in Namibia, 1991–2016.

3. Sociolinguistic Context

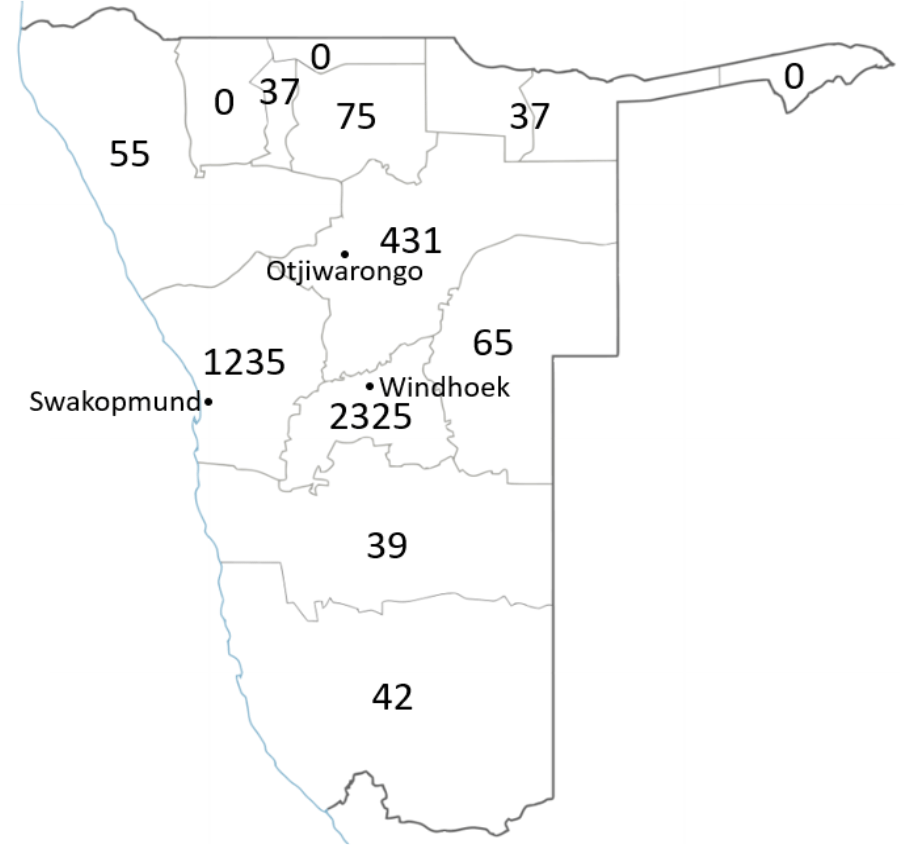

German is linguistically vital in Namibia. It is spoken by diverse groups of people, the largest among them being descendants of Germans who settled in Namibia during and after the colonial times. They are an economically strong group, who are mostly concentrated in urban areas of central Namibia (figure 1), such as Windhoek (Khomas region), Swakopmund (Erongo region), and Otjiwarongo (Otjozondjupa region). A significantly smaller number of the German speakers are spread across the country in rural areas, predominately on farms (slightly more than 700 German-speaking households live in rural areas of Namibia, according to the 2011 Census; Namibia Statistics Agency 2011:171).

Figure 1. Regional distribution of German-speaking households.

Source: Namibia Statistics Agency (2011:171).Footnote 12

Other groups of German speakers in Namibia include German citizens (referred to as Deutschländer or more mockingly as Jerries by German-speaking Namibians) who migrated more recently to Namibia and a much smaller group of approximately 430 so-called DDR-Kinder ‘German Democratic Republic children’ (see, for example, Kenna 2004 & Witte et al. Reference Witte, Schmitt, Polat and Niekrenz2014).Footnote 11 In addition, there are numerous individuals who acquire German as an additional language. These include the ever-increasing number of students of German as a foreign language (Deutsch als Fremdsprache, DaF), who are taught German at various educational institutions in the country (Shah & Zappen-Thomson Reference Shah, Zappen-Thomson, Corinne and Shah2017:139), as well as individuals who acquire German in more informal contexts (for example, children of farm workers who may pick up German through play and interaction with the children of German farmers). Finally, a “dying contact variety” (Deumert Reference Deumert2009:349) known as Namibian Kiche Duits lit. ‘kitchen German’ is a German-based variety that developed during German colonialism. Crucially, Kiche Duits never became an in-group language but was mainly employed for interethnic communication between the German colonists and their workers (Deumert Reference Deumert2009, Reference Deumert2017, Reference Deumert2018).

In this paper, we focus on the German spoken by the descendants of German colonists who settled in Namibia during and after the colonial times. Schlettwein (Reference Schlettwein, Krishnamurthy and Vale2018:329) describes the linguistic situation as follows:

[T]he ‘indigenous’ native German speakers in Namibia have created their own brand of German, which manifests itself at structural, pronunciation and metaphorical levels, as well as the borrowing of vocabulary, from Afrikaans, English, Oshiwambo, Khoekhoegowab and Otjiherero.

A number of terms are used to refer to this “own brand of German” (for a detailed discussion on terminology, see Zimmer Reference Zimmer and Herrgen2019:1185–1186). The term Südwesterdeutsch ‘South-Westerners’ German’, which relates to the former colonial name of Namibia, that is, Südwestafrika ‘South-West Africa’, was in wide circulation prior to and immediately after Namibia gained independence in 1990 (see, among others, Gretschel Reference Gretschel1984, Reference Gretschel1995; Pütz Reference Pütz1991; Böhm Reference Böhm2003:563). Although nowadays the term is considered politically incorrect, it continues to be used in Namibia, albeit less frequently. The term Nam-Släng, promoted by the Namibian German Kwaito artist and rapper EES through his YouTube channel (see also Sell Reference Sell2011, Reference Sell2014), refers to a youth variety (Zappen-Thomson Reference Zappen-Thomson2013, Kellermeier-Rehbein Reference Kellermeier-Rehbein2015) primarily realized in speech.Footnote 13 It is seldom exemplified in writing, and when it is, it is usually used in an informal manner for the purposes of demonstrating authenticity and local flavor, for example, in the squibs (Glossen) of the Allgemeine Zeitung (AZ; see Radke Reference Radke2017).Footnote 14 A more neutral all-encompassing term used by speakers is Namdeutsch ‘Nam-German’. Other terms found in the literature include Namibisches Deutsch, Namibia-Deutsch (Kellermeier-Rehbein Reference Kellermeier-Rehbein and Thomas Stolz2016:223), and Namlish.Footnote 15

NG is not a homogenous variety and is best described using a continuum, one end of which represents a standard-based variety of NG (that is, a variety close to SG, as spoken in Germany) and the other end approximates a nonstandard variety of NG (that is, Südwesterdeutsch/ Nam-Släng/Namdeutsch/Namlish). NG features are used cross-generationally (Wiese et al. Reference Wiese, Simon, Zimmer and Schumann2017:234, Reference Zimmer and HansZimmer forthcoming), and the frequency in the use of typical NG features depends on a number of variables; these may relate to the speaker (such as age, gender, L1 of parents, school attended) and/or to the situation at hand (such as topic of conversation, degree of formality, presence of in-group versus out-group speakers; Zimmer Reference Zimmer2020, Wiese & Bracke Reference Wiese and Bracke2021, Wiese et al. Reference Wiese, Sauermann, Bracke, Karen and Gregory2022). The use—conscious or unconscious—of highly marked NG features, and in particular the extensive borrowing of lexical items from Afrikaans and English, is more typical of informal spoken speech (Bracke Reference Bracke and Zimmer2021, Wiese & Bracke Reference Wiese and Bracke2021) and is particularly frequent in discussion of topics for which German-speaking Namibians do not have the necessary German vocabulary at their disposal (for instance, when talking about their profession, for which they were educated/trained in either English or Afrikaans).

NG is used in both oral and written communication, that is, NG is not restricted to the spoken domain; rather, lexical items specific to NG sometimes appear in the written domain (for example, in the AZ; see Kellermeier-Rehbein Reference Kellermeier-Rehbein, Engelberg, Kämper and Storjohann2018 and Kroll-Tjingaete Reference Kroll-Tjingaete2018, among others), NG morphosyntactic patterns less so (Shah Reference Shah2007). Various NG dictionaries have been published over the years (Nöckler Reference Nöckler1963, Pütz Reference Pütz2001, Sell Reference Sell2011).Footnote 16 A number of common NG lexical items are considered core vocabulary items by the community and their use is not stigmatized. Some of the most common NG lexical items have also found their way into the second edition of the Variantenwörterbuch des Deutschen (Ammon et al. 2016) and are considered to be standard.Footnote 17 These include Braai ‘barbecue’, Panga ‘bush knife’, and Rivier ‘dry river’ (Ammon et al. 2016:128, 521, 600). SG nevertheless functions as the prestige variety (as far as overt prestige is concerned), promoted by educational institutions.

The community is generally proud of their ability to speak German and of the variety of German they speak (see Wiese et al. Reference Wiese, Sauermann, Bracke, Karen and Gregory2022 on the tension between standard language ideology and pride in local NG characteristics). For this close-knit speech community, language is considered an in-group marker and seems to constitute a significant component of their unique Namibian-German identity, allowing them to demarcate themselves from the “other Germans”, that is, Germans from Germany, as well as from other Namibian ethnic groups (see also Schmidt-Lauber Reference Schmidt-Lauber1998:308–309, Wecker Reference Wecker2017, Wiese et al. Reference Wiese, Simon, Zimmer and Schumann2017:7, Bracke Reference Bracke and Zimmer2021, Wiese & Bracke Reference Wiese and Bracke2021, Wiese et al. Reference Wiese, Sauermann, Bracke, Karen and Gregory2022).

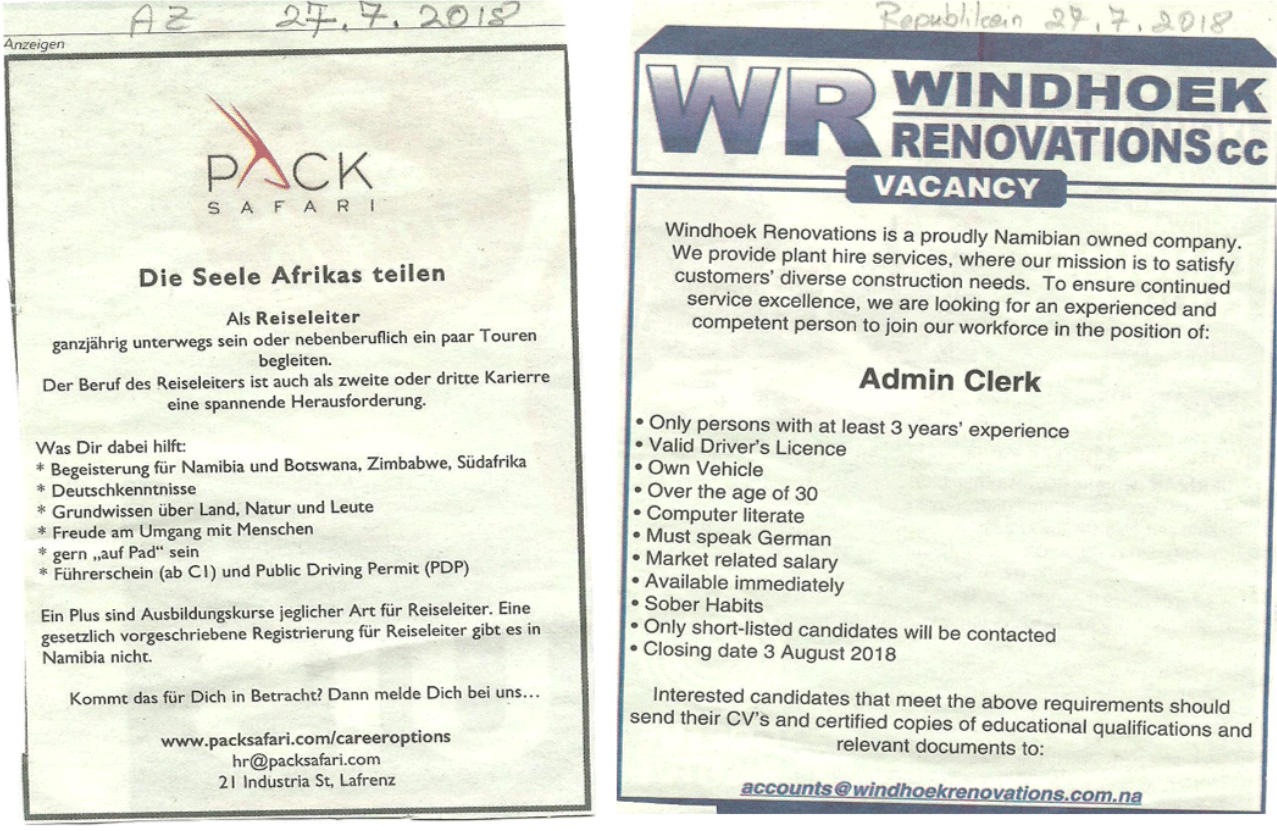

German is acquired as a first language by the younger generations through intergenerational language transmission. It is used in private domains, such as the home environment, as well as in numerous public domains, including cultural, religious, educational, medical, and professional settings (see Shah & Zappen-Thomson Reference Shah, Zappen-Thomson, Corinne and Shah2017:135–141). These include kindergartens, primary and secondary schools, boarding schools, churches, media, some areas of business (especially tourism), etc. (Ammon Reference Ammon2015, Wiese et al. Reference Wiese, Simon, Zimmer and Schumann2017, Zimmer Reference Zimmer and Herrgen2019). It is visible in the public realm through signs, street names, and place names. With numerous business enterprises being run by German-speaking Namibians, it is widely considered to be a business language of Namibia. This makes it an attractive language for Namibians to learn due to the professional opportunities it offers, and job advertisements in the local newspapers often demand or strongly desire competency in German. This is illustrated in figure 2, which shows an advertisement from AZ (left) and from the Afrikaans-language newspaper Republikein (right).Footnote 18

Figure 2. Job advertisements in German-language newspapers, July 2018.

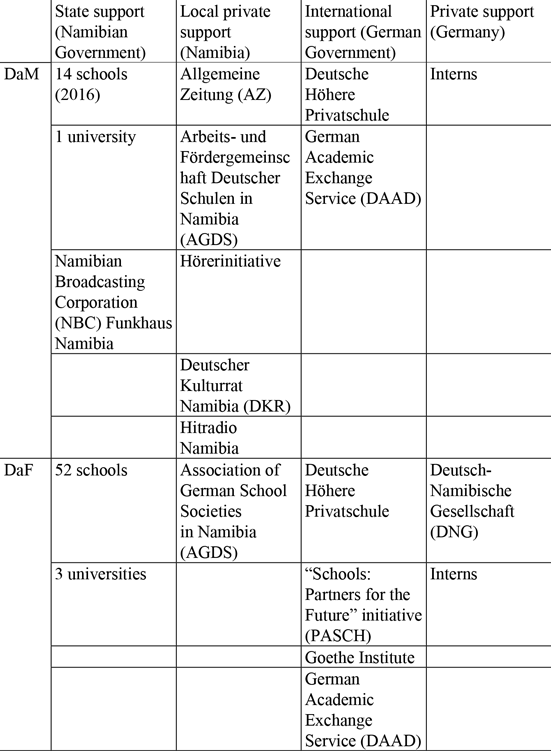

The status of a national language confers certain privileges, allowing German, for example, to be used in education, legislation, administration, and the judicial system. The state support that German receives is complemented by the support it receives through local private means as well as from sources in Germany (either from the German Government or from private donors). For example, in the realm of education, the subjects Deutsch als Muttersprache (German as a mother language, DaM) and Deutsch als Fremdsprache (German as a foreign language, DaF) receive state and private support, both from Namibia and Germany (see table 4; data from Shah & Zappen-Thomson Reference Shah, Zappen-Thomson, Corinne and Shah2017). These various levels of support—together with the strong language loyalty among German-speaking Namibians and the many efforts that the community makes to preserve their language—have contributed to its continued use and its success in resisting the otherwise prevalent English hegemony in Namibia (Shah & Zappen-Thomson Reference Shah, Zappen-Thomson, Corinne and Shah2017).

Table 4. Support for the German language in Namibia (DaF: Deutsch als Fremdsprache, DaM: Deutsch als Muttersprache).

Namibians—like most Africans—are multilingual, and the German-speaking community in Namibia is no exception. Code-switching is done frequently and with ease. In addition to the registers of German between which they can effortlessly switch (NG, SG, etc.), NG speakers routinely use other languages, typically Afrikaans and English, which they generally master or even speak fluently. The older generation is more familiar with Afrikaans. The younger generation, by contrast, uses English more often; for them, English symbolizes “a marker of a new and more inter-ethnically/-racially open generation of German Namibians” (Wiese et al. Reference Wiese, Simon, Zimmer and Schumann2017:234). German-speaking Namibians may also have competence—to varying degrees—in one or more of the 10 other national languages of Namibia. This is especially the case for German children who grow up on farms; through, for example, play and interaction with the children of farm workers (who may speak languages such as Oshiwambo, Otjiherero, and Khoekhoegowab) they may acquire one or more of these languages (Wiese et al. Reference Wiese, Simon, Zimmer and Schumann2017:8).Footnote 19

All aspects mentioned so far have shaped (in one way or another) the structural characteristics of NG. They are therefore crucial for a holistic understanding of those characteristics. This holds for historical aspects, the vitality of NG, language attitudes within the community, schooling, media, multilingualism, etc. In the following, we zoom in on two morphosyntactic features of NG in order to illustrate some of its grammatical characteristics. The examination of these two features complements our historical and sociolinguistic descriptions and shows how the different aspects that shape NG interact with one another.

The two morphosyntactic features that we investigate are the linking element +s+ (section 4) and the gehen + infinitive construction (section 5). These case studies were specifically chosen because different explanations could, at first glance, be proposed for their development in NG. While the gehen + infinitive construction in NG bears striking resemblance to a parallel structure in Afrikaans and English, this does not seem to be the case with the linking elements in NG.Footnote 20 Accordingly, language contact seems to have different degrees of impact on the development of the two phenomena, which opens up an interesting comparative perspective on grammatical innovations in NG. A deeper exploration of these features can provide insights into different kinds of dynamics of German in the multilingual context of Namibia.

Both phenomena are analyzed via a questionnaire study. This method was particularly suitable for our purposes, as it allowed for a systematic elicitation of target language forms. Through its quick administration, a larger sample size was also possible. Where possible, the DNam corpus is also used for our analysis.Footnote 21

4. Linking Elements

In German, compounds occur in two variants: Either the compound consists only of the stems, as in Hand+tasche ‘handbag’, or a linking element is inserted between the stems, as in Heizung+s+keller ‘boiler room’.Footnote 22 This holds true for both GG and NG. However, in Namibia, linking elements are more frequently used and can be found in compounds in which GG would usually not use this element.Footnote 23 Examples include Lehn+s+wort ‘loan word’, Kreuzwort+s+rätsel ‘crossword puzzle’, and Miet+s+wagen ‘rental car’. The latter appears, for example, in the AZ, as in 1.

(1)

This particular variant is very unusual in GG. In the German Reference Corpus (Deutsches Referenzkorpus, DeReKo), there are only four instances of Miet+s+wagen. The competing variant, Mietwagen, appears 60,191 times, that is, in more than 99.99% of cases.

This standard-divergent feature of NG seems to be particularly interesting as the main contact languages do not seem to play a major role here. For example, the linking element in Miet+s+wagen can be explained neither by direct transfer from Afrikaans (the equivalent would be huur+motor) nor by transfer from English (rental car; details to be discussed below). Hence, different approaches have to be considered in order to understand the phenomenon. Convergence, which has been the standard explanation provided for most standard-divergent features of NG, does not seem to apply here. Instead, we argue that the history of German provides important insights. In the following, we discuss the results of a questionnaire study. Subsequently, we provide a brief overview of the emergence and spread of the linking element +s+ in German in general and examine how this might be used to explain our observations made in Namibia.Footnote 24

4.1. Questionnaire Data

Starting from the observation that linking elements that are unusual in GG can be observed in NG, we conducted a questionnaire study to learn more about this phenomenon.Footnote 25 We asked German-speaking Namibians to translate a list of selected words and phrases from English into German (see table 5, leftmost column).Footnote 26 An advantage of this method is that linking elements are extremely rare in English, so there should be no bias toward them.Footnote 27 The translation task also contained 12 fillers. The English words were selected to elicit one of the 26 German compounds listed in table 5 (third column). As was to be expected, not all participants used one of these German translations. For example, suit trousers was repeatedly translated as Hose ‘trousers’, which by definition cannot contain a linking element because it is a simplex. Such answers were excluded from the analyses.

Table 5. Critical items in the translation task.

The list of words was compiled in such a way as to prompt the participants to choose German translations that would differ from one another with respect to linking elements in SG. Since the distribution of +s+ in SG to a large extent does not follow simple rules, we relied on corpus data for the selection of items: There are only some morpho-logical/phonological properties of the first constituent that (almost) obligatorily entail the use of the linking element (such as the suffixes -heit/keit, -ion, -(i)tät, -ling, -sal, -schaft, -tum, and -ung) or prevent it (such as masculine gender + weak inflection class membership; constituent-final sibilant; constituent-final vowels).Footnote 28 Other cases are subject to lexeme-specific preferences (see Kopf Reference Kopf2018a:28–32, 43 for an overview).Footnote 29

Table 5 lists the selected items and contains information on the frequency of the linking element in DeReKo (rightmost column).Footnote 30 The range extends from mandatory linking elements, as in Arbeit+s+platz ‘working place’, to cases where a linking element would be considered ungrammatical in SG, as in *Taxi+s+fahrer ‘taxi driver’. For some words, both variants occur frequently, as in Schaden+s+ersatz versus Schaden+ersatz ‘compensation for damages’. Furthermore, the final sound of the first constituent of the compound was varied, as it has been shown that this aspect has a crucial impact on the distribution of +s+ in GG (see, for example, Kopf Reference Kopf2018a:30–32): First constituents ending in a plosive or a vowel were integrated (in addition to Schaden(s)ersatz, where the first constituent ends in a nasal sound).

116 speakers of NG took part in our study (100 secondary school students and 16 adults, age range: 14 to 66 years). The data were collected in 2018 in three Namibian cities: Windhoek, Swakopmund, and Otjiwarongo. 54 females and 58 males participated in the study (no other categories were suggested by the participants), and four participants did not report their gender. The participants produced 1,251 compounds that could be used for our analyses. Since Geburt+s+tag+s+party and Geburt+s+tag+s+feier contain two slots that could be filled with a linking element, these words were counted twice, resulting in a total number of 1,358 tokens to be analyzed.

In 524 cases (or in 39%), an +s+ was used. Among the variables that (potentially) influence the distribution of this linking element, the final sound of the first constituent stands out. A final vowel of the first constituent never co-occurs with +s+ in our data set—Bürostuhl, Klimawandel, Klimaveränderung, Risikofaktor, and Taxifahrer are never used with a linking element. Accordingly, this seems to be an inviolable constraint. Given the large number of standard-divergent variants in NG (both in general, when compared to GG, and with regard to linking elements; see below), this is a remarkable observation. Of the other potential factors, none categorically co-occurs with either +s+ or with +Ø+. This, however, does not mean that none of them have an impact on the variation. Rather, there is no categorical difference here, but (at best) a tendency.

In order to test the impact of the other variables, a binomial generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) was applied (see, for example, Baayen Reference Baayen2008:278–284).Footnote 31 Because of the high number of potentially influential factors, such a multifactorial analysis seems appropriate. A particular advantage of mixed models (such as GLMM) is that random effects can be integrated (see below). All tokens with the first constituent ending in a vowel were excluded from this analysis. Furthermore, the final sound of the first constituent was not integrated as a predictor because one level of this variable could perfectly predict the outcome, that is, one would be dealing with complete separation (see Levshina Reference Levshina2015:273, among others).

Instead, six other variables were included that fell into two categories. One category was sociolinguistic in nature and included the variables age, gender, and residence of the participant. The other category was linguistic and reflected features of the compounds:Footnote 32 The variable le_germany captured information on how often a linking element occurred in the word in question in GG. This variable had three levels: “yes”, if +s+ was used in ≥ 99% of all cases in DeReKo, “no”, if it was used in ≤ 1%, and “facultative” for all cases in between (see table 5). Next, the variable le_afrikaans had two levels: “yes”, if there was an equivalent in Afrikaans that contained a linking element (as in huwelik+s+voorstel ‘marriage proposal’) and “no”, if that was not the case (as in geskenk+Ø+papier ‘gift wrapping paper’; see table 5, second column).Footnote 33 The possible impact of the absence/presence of a linking element in SG and Afrikaans was considered because of the normative orientation toward SG and the intense contact with Afrikaans. Finally, the variable cognates_1constituent captured information on whether the first constituent of the English word and the first constituent of the German translation were cognates (for example, birthday party and Geburt+s+tag+s+feier) or not (for example, suit trousers and Anzug+s+hose). This variable allowed us to assess whether close resemblance between the English items and the German target words had an influence on how participants responded (see below for more details).Footnote 34

In addition to these (potentially) explanatory variables, two random effects were integrated, namely, participant and type. This was to ensure that neither idiosyncratic behaviors of individual speakers nor outliers due to one specific compound type would skew the results. The presence or absence of +s+ is the binary dependent variable (le) that is to be predicted by the explanatory variables.Footnote 35

To test which variable had a significant impact on the dependent variable, a maximum model was fitted as a first step. The model specification is given in 2.

(2)

Subsequently, all variables that did not significantly improve the quality of the model were identified. Only le_germany and cognates_ 1constituent significantly contributed to the correct prediction of the outcome. This indicates that the presence or absence of a linking element in Afrikaans equivalent terms did not influence the likelihood of +s+ in our data. The same holds for the sociolinguistic variables. All these variables were removed from the model in a second step. Hence, the final model contains two explanatory variables and the random effects (table 6).

Table 6. Results of a GLMM (absence or presence of linking element).

This model explains a substantial proportion of the variance (marginal r 2 =0.595; conditional r 2 =0.753) and discriminates very well (C=0.959). 88.9% of all observations are correctly predicted by the model (this rate is significantly higher than the No Information Rate; p>0.001***). Multicollinearity is no problem as all Variation Inflation Factors (VIFs) are below 3.

The variable le_germany indicates that more participants used a linking element, if +s+ was obligatory in the compound in SG. Thus, there are parallels between SG and the participants’ response behavior. This is not very surprising given the general orientation toward SG in German classes in schools, in Namibia’s German-language media, etc. Interestingly, however, the level “no” does not reach the significance level. The absence of linking elements in the corresponding compounds in SG did not decrease the probability of +s+ (compared to the reference level “facultative”): +s+ is distributed far more broadly in our data set than in SG texts. In contrast to the final sound of the first constituent (see above), the influence of le_germany is far from categorical: While most tokens in the analyzed data set are in line with SG, a nonmarginal number of tokens is not: 109 tokens can be classified as standard-divergent (that is, 11.7% of all tokens where the use +s+ is not facultative in SG; for more details, see below). Furthermore, a closer look at the compounds with an optional linking element in SG reveals another difference: The proportion of tokens with +s+ per type is consistently higher in our data than in DeReKo. This difference is significant in three cases (see table 7).Footnote 36

Table 7. Proportion of tokens with +s+ per type.

One should keep in mind that different types of data were compared, and that the sample size for Namibia is small.Footnote 37 However, the results could be read as an indication of a tendency toward i) the use of +s+ in cases where the linking element is optional in SG and ii) standard-divergent compounds.Footnote 38 The latter includes both standard-divergent presence and absence of a linking element. However, omitted linking elements should not be overrated. As stated above, the translation task was chosen because no bias toward +s+ was to be expected due to the absence of linking elements in (most of) the English words. However, there might naturally be a bias toward +Ø+. In fact, the results of the GLMM support this idea. The estimate of the second significant variable, cognates_1constituent, indicates that +Ø+ is more likely to occur if the first constituents of the source word and the translation are cognates. This means that standard-divergent omission of the linking element is more likely in words such as Advent+s+kalender ‘advent calendar’ than in Arbeit+s+platz ‘place of work’. Presumably, close resemblance between the English and the German words fosters a 1:1 transfer from one language into the other during the translation task. Note that there might be an effect that goes beyond this potential artefact of the method, that is, close resemblance might also be relevant in natural language use. It is conceivable that similarity promotes convergence. However, this cannot be determined using our methodology. It is well known that translations that resemble their source have to be taken with caution. Therefore, many scholars focus on deviations from the translated source (see, for example, Fleischer et al. Reference Fleischer, Hinterhölzl and Solf2008 for methodological considerations on this issue). This is also how we proceed in the following. The standard-divergent occurrences of +s+ are more interesting in any case, as they can be explained neither as an artefact of the method, nor as transfer from English. In addition, as indicated by the variable le_afrikaans, which had no significant impact, there is no evidence for an influence of the Afrikaans equivalents.

Another possible explanation for the repeated occurrences of standard-divergent +s+ in NG (and the possible increase in frequency in contexts where +s+ is also possible in SG) would be the influence of Afrikaans on a more abstract level. If Afrikaans made much more use of +s+ than German, an expansion of +s+ could be explained as a contact-induced change from a minor to a major use pattern (Heine & Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2005:40–62). However, this does not seem to be the case. Combrink (Reference Combrink1990:272), for example, states: “In Sweeds en Duits is -s- bv. uiters volop, in Nederlands en Afrikaans minder, in Fries nog minder en in Engels die minste” [In Swedish and German, -s- is e.g. extremely abundant, in Dutch and Afrikaans less, in Frisian even less and in English the least.]Footnote 39 It should be noted that when the +s+ linking element is used in Afrikaans, it is often used in similar contexts to SG. For example, first constituents ending in -heid/-heit, -ing/-ung or -skap/ -schaft almost categorically co-occur with +s+ in both languages (see, among others, Kempen Reference Kempen1969:99–102 on Afrikaans and Ortner et al. Reference Ortner, Elgin Müller-Bollhagen, Pümpel-Mader and Gärtner1991:73–75 on German).Footnote 40 However, apart from such specific contexts, there are many cases where the use of +s+ cannot be described by simple rules. This holds both for German and for Afrikaans (see, for example, Donaldson Reference Donaldson1993:438–439 and Krott et al. 2007). In fact, the distribution of +s+ has been referred to as “arbitrary” (Fuhrhop & Kürschner Reference Fuhrhop, Kürschner, Peter, Ohnheiser, Olsen and Rainer2015:576) or “idiosyncratic” (Krott et al. 2007:45). Crucially, Afrikaans has no rule along the lines of “first constituent ending in a plosive entails +s+”, which would have made an explanation of standard-divergent +s+ in NG in terms of contact-induced change very plausible. As in SG, there is variation in this phonological context: Some compounds are used with +s+ (gebruik+s+reëls ‘instructions’), some without (werk+Ø+gewer ‘employer’), and some allow both options (week+s+dag versus week+Ø+dag ‘weekday’).Footnote 41

Against this backdrop, it seems unlikely that standard-divergent +s+ in NG can be categorized as a contact-induced change from a minor to a major use pattern. So, transfer from one of the main contact languages, Afrikaans or English, does not seem to be a decisive factor here. Instead, we argue that it is worth considering the recent history of German, which is the focus of the next section.

4.2 A Brief History of the Linking Element +s+ in German

The linking element +s+ emerged from an inflectional suffix, namely, the genitive -s. This was the result of a reanalysis that took place in Early New High German (1350−1650): Prenominal genitive attributes (which were then far more common than today) were reanalyzed as the first constituent of a compound. The example in 3a illustrates an unambiguous genitive construction because the determiner agrees with the genitive attribute König-s. Example 3b contains a bridging construction, that is, a construction that allows for both interpretations, which makes reanalysis possible. Finally, 3c shows the new construction, that is, a compound. All examples are taken from Kopf Reference Kopf and Tanja Ackermann2018b:94.Footnote 42

(3)

The example in 3c still contains an -s. This -s cannot, however, be classified as an inflectional suffix anymore, as Königs Schloss is to be analyzed as a compound. This is indicated by the determiner das, which is neuter and therefore agrees with Schloss (or rather, with the compound Königs Schloss, whose gender is determined by its head Schloss).Footnote 43 If this construction were not a compound, the determiner would have to agree with König, which is masculine (Kopf Reference Kopf and Tanja Ackermann2018b:94).

In cases such as 3c, one is clearly dealing with a linking element. These elements were primarily limited to compounds with a masculine or neuter first constituent (such as König ‘king’). They are usually referred to as paradigmatic, as the first constituent, which includes the linking element, formally matches the genitive (Fuhrhop Reference Fuhrhop, Lang and Zifonun1996). Subsequently, however, more and more compounds with feminine first constituents were used with the linking element +s+, as in 4. In such cases, the first constituent + the linking element could never be interpreted as a genitive construction, as feminine nouns do not have a genitive -s (and so the first constituent + linking element of such compounds would differ from all other cells in the paradigms of feminine nouns). This unparadigmatic type of linking element gains ground in the 17th century (Kopf Reference Kopf2018a:217, 273).

(4)

Thus, the restrictions for the use of +s+ loosen. This development is accompanied by further changes that support the spread of +s+. For example, a new word formation pattern with -ung derivatives as the first component of a compound emerges, as in Nahrung+s+mittel ‘foodstuff’. In this new pattern, +s+ is almost always used (Kopf Reference Kopf2018a:259–263). In contemporary German, +s+ is close to obligatory in such constructions. Similar observations can be made regarding another new pattern, that is, compounds with nominalized verbs as their first constituent (Kopf Reference Kopf2018a:263–266).

All in all, +s+ clearly gains importance in (Early) New High German. This holds true for paradigmatic and for unparadigmatic cases and is reflected in an increase of productivity (Kopf Reference Kopf2018a:250–252). This can be summarized as a clear tendency toward a spread of +s+ beginning in the Early New High German period. However, this development seems to have slowed down (see, among others, Kopf Reference Kopf2018a:286), which goes along with a reduction of variation. This was already noted by Pavlov (Reference Pavlov1983), who analyzed the proportion of types that exhibit variation (presence versus absence of a linking element) in texts from Early New High German and the 1st century of the New High German period. Kopf (Reference Kopf2018a:254) observes that in general, there is less variation in the use of linking elements in New High German than in Early New High German. This can be explained by the growing importance of linguistic norms (Pavlov Reference Pavlov1983:10–11).

Against this backdrop, the standard-divergent use of certain linking elements in NG seems to be explicable as follows:

(i) There is/was a tendency toward a spread of +s+ in German.

(ii) This development slowed down, presumably due to the increased importance of linguistic norms, resulting in less variation (in GG).

(iii) Speech communities in multilingual contexts are generally more receptive to variation; compared to mainly monolingual groups, norms typically play a minor role here. Therefore, the spread of +s+ might be more advanced in NG than in intraterritorial varieties. The standard-divergent forms in NG seem to continue a development that in other varieties has been partly constrained by language-external influence.

In light of the explanation in i–iii, two scenarios are possible: The first is that immigrants from Europe imported the variants with the linking element to Namibia in the 19th century. This is conceivable as, for example, Mietswagen can be found in texts from this period, as shown in 5.Footnote 44

(5)

This variant competed with Mietwagen, which prevailed in the following years. The last occurrence of Mietswagen in DeReKo dates from the 1950s, and already in that decade, the variant without the linking element predominated by far (92%). Apparently, Mietswagen fell victim to the increasing norm awareness, which typically goes hand in hand with the ideal of a homogeneous language use within a speech community. The latter is particularly influential in Germany (see, for example, Maitz & Elspaß Reference Maitz and Elspaß2013). At the same time, both variants are presently used in Namibia. It is possible that they have been coexisting since the 19th century.

The other possibility is that Mietswagen and the like are grammatical innovations in NG drawing on a language-internal tendency that has been constrained in other contexts. Given that the occasions to talk about rental carriages in the past were presumably few in Namibia, this might be the more plausible scenario. Such a development would be consistent with what Trudgill (Reference Trudgill2004:129–147) has labeled “theory of drift”: Innovations in an extraterritorial variety are often not (only) due to dialect or language contact but can either be explained as “continuations of a long ongoing process” (Trudgill Reference Trudgill2004:136) or as the result of “propensities to linguistic changes resulting from structural properties which varieties inherit” (Trudgill Reference Trudgill2004:163).

In any case, transfer from the contact languages does not seem to play a central role in the emergence of standard-divergent linking elements. The tendency in multilingual settings to attach less importance to linguistic norms and the corresponding propensity for variation provide a more plausible explanation (see, for example, Wiese et al. Reference Wiese, Simon, Zappen-Thomson and Schumann2014, Reference Wiese, Simon, Zimmer and Schumann2017).

The idea that the standard-divergent linking elements in NG could follow a tendency that was (or still is) characteristic of other varieties is supported by the distribution of linking elements in our questionnaire data. Linking elements are not distributed randomly in our data set but in accordance with constraints relevant in SG: A final vowel excludes +s+ in both varieties (see, among others, Wegener Reference Wegener2003, Reference Wegener2005; Fehringer Reference Fehringer2009; Kopf Reference Kopf2018a:28–32 on German varieties, including SG). Thus, these linking elements occur in our data set only in contexts where +s+ would theoretically also be possible in SG. This can be illustrated nicely with the first constituent Miet+. In SG, there is a strong tendency toward Miet+s+haus (versus Miet+Ø+haus ‘tenement’; 96% of cases in DeReKo contain the linking element +s+) and Miet+s+kaserne (versus Miet+Ø+kaserne ‘block of flats’; 98%). In contrast, Miet(s)wohnung is typically used without the linking element, and in Mietwagen and Mietauto +s+ is almost categorically absent in SG (see table 5).

At the same time, it has repeatedly been shown that the first constituent is decisive as regards the use of a linking element in German (see, among others, Krott et al. 2007). Against this backdrop, the outlined differences are curious. There are no obvious intralinguistic reasons why Mietwagen and Mietauto should not also be used with +s+, and it seems to be the case that there is a tendency to abandon such idiosyncrasies in NG.Footnote 45

5. Go-Future Construction

5.1 Expression of Future in German, Afrikaans, and English

SG has two constructions for expressing the future: the auxiliary verb werden + infinitive, as in 6a, and the futurate present tense, as in 6b.

(6)

The second construction, the futurate present tense in 6b, is used more frequently than werden + infinitive in 6a (Brons-Albert Reference Brons-Albert1982, Di Meola Reference Meola2013) and is quite common in contexts where English would resort to other constructions to express futurity, for example, by using the future auxiliary will, as in 7a, or going to, as in 7b.

(7)

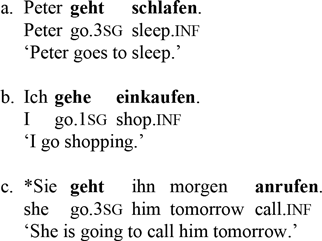

The two constructions in 6 are also used in NG to express future meaning. In addition, a third construction can be observed: gehen + infinitive, as in 8a.Footnote 46 Afrikaans and English can also express futurity with constructions involving the verb go: Example 8b contains gaan + infinitive and 8c contains going + infinitive (see also the English translation in 7b above). This type of construction is henceforth referred to as the go-future construction.

(8)

Forming the equivalent sentence in SG with gehen is not possible and would be considered ungrammatical.Footnote 47

Since gehen + infinitive in NG mirrors similar constructions in Afrikaans and English, this may suggest that the use of go-future in NG is a contact effect.Footnote 48 Previous research on German in southern Africa has reached a similar conclusion in this regard (see, among others, Shah Reference Shah2007 for NG and Franke Reference Franke2008 for South African German). While there is no denying that language contact clearly plays a significant role, we argue, based on a closer examination of the grammaticalization of go-future constructions in general, that there is more to be said about this innovation.

In the following sections, we take a closer look at the use of the go-future construction in present-day NG and discuss the results of our questionnaire study. We also provide a brief comparative overview of the grammaticalization of go-future constructions in other Germanic languages and draw some conclusions for its emergence in NG.

5.2. Corpus and Questionnaire Data

By examining the corpus data, we found that the go-future construction is frequent in spoken NG, especially in informal free speech (see table 8).Footnote 49

Table 8. Frequency of future constructions with gehen versus werden in the corpus.

German-speaking Namibians, therefore, have more options at their disposal to mark the future than the speakers of SG, and, crucially, they have two auxiliaries to choose from, werden and gehen. If one compares the frequency of these auxiliaries in future constructions, werden is the more frequent of the two; gehen as a future auxiliary, however, is used in over one fifth of cases in the corpus, making it one of the more frequently used standard-divergent features in NG (Zimmer Reference Zimmer2021b). Moreover, the 55 instances of gehen in the go-future construction occur with a wide range of main verbs (see below for more details).

In order to examine the choice of auxiliaries for the expression of the future, a questionnaire study in the form of a cloze test was conducted. Participants were presented auditorily with the first part of a sentence and instructed to use predefined lexemes in order to complete it. These preselected lexemes could be modified (for example, inflected) by participants and/or complemented with words of their own choice.

For each group, the data collection started with a test phase to allow participants to familiarize themselves with the design of the study and to ensure that the instructions provided were clear. The stimuli, that is, the first part of each sentence, had been prerecorded by a member of the German-speaking community in Namibia. The participants were presented with a questionnaire and asked to record their responses by hand. This questionnaire contained only the lexeme(s) to be used, in addition to the sentence number, as shown in 9.

(9)

The task of filling in the gaps had to be carried out within a period of 10 seconds (a signal was played after 8 seconds); the response time was deliberately kept short to ensure spontaneous answers and not to provide too much time for reflection on the metalinguistics of the sentences. A total of 34 sentences had to be completed by each participant.

Of the 34 items, 16 had been designed to elicit one of the three constructions to express futurity (see table 9). The other 18 items were fillers (or items that were used for the investigation of other linguistic phenomena not discussed in this article). The stimuli were inspired by corpus data and were created to specifically determine the influence of several factors on the expression of the future (see table 10 below). The items were presented to the different groups in two different and randomized sequences.

Table 9. Stimuli used to elicit constructions expressing futurity.

Table 10. Coding used for the questionnaire study.

184 participants took part in the questionnaire study, that is, almost 1% of the German-speaking community in the country (72 female and 108 male participants as well as four persons who did not provide any information on their gender; no further categories were suggested by these participants). The age of the participants ranged from 14 to 67 years. Data were collected in Windhoek, Swakopmund, and Otjiwarongo. The majority of the questionnaires were completed by secondary school students (149 participants). However, a significant number of adults from each location participated in the study as well (35 participants). Some participants took part in both this study and the study on linking elements.

In their responses, participants used the present tense, the werden + infinitive construction or the gehen + infinitive construction. As mentioned above, the use of the present tense for a future event, as in 10a, is common in Germany and is not specific to NG. For our study, we decided to focus on the auxiliary choice between gehen ‘to go’, the standard-divergent option in NG, as in 10b, and werden lit. ‘to become’, as in 10c.

(10)

The data clearly show that gehen is used as a proper auxiliary in the same sense as werden. This is, for example, evidenced by the combination of gehen with itself in 11.Footnote 50

(11)

The results of the questionnaire study show that the participants used werden in most cases; gehen occurred only in 7% out of 1,378 sentences with an auxiliary. It cannot be ruled out that this proportion does not reflect the true importance of gehen as a future auxiliary in NG, especially when considering its frequency in the corpus (see above). Furthermore, the questionnaire somewhat resembles typical tasks used in the contexts of language teaching, which might have led to a bias toward the variant that conforms to SG. This idea is supported by the fact that some participants revised their responses: They initially used gehen but then “corrected” it to werden. In any case, it is remarkable that there is a nonmarginal number of standard-divergent instances in the data set. This substantiates that gehen is a significant option in NG.Footnote 51

We were particularly interested to see if any specific patterns concerning the use of gehen versus werden could be detected in the responses. So, the test items in table 9 were designed to investigate the influence of four factors: the time of the event, the animacy of the participants, the presence of intention and predictable/likely outcome, and whether the main verb is a borrowing from either English or Afrikaans. Historically, the first three factors played a major role in future auxiliary selection in English and Dutch, and they remain important in present-day English and Afrikaans. Therefore, we wanted to see if they were relevant in NG as well.Footnote 52 The fourth factor is inspired by our analysis of the corpus data. Table 10 presents the four variables along with the relevant hypotheses, which are based on preferences in English and Afrikaans and on our analysis of the corpus data.Footnote 53

In the corpus, no level of any one of these variables co-occurs categorically with gehen or werden, as briefly illustrated below. As far as our hypotheses in table 10 are concerned, this means that one may be dealing with preferences rather than inviolable constraints.

With respect to the variable time_of_event we observed that in NG, the go-future construction signals events that are about to happen, as in 12a, as well as events taking place in the distant future, as in 12b.

(12)

Historically, in English and in Dutch, be going to and gaan, respectively, were first associated with imminent future events (Hilpert Reference Hilpert2008:106–123). In present-day English, imminent future events favor be going to, while events taking place in the far future favor will (Palmer Reference Palmer1974:147; Nicolle Reference Nicolle1997). In present-day Afrikaans, gaan signals both immediate and remote future (Kirsten Reference Kirsten2018:278).

With respect to the variable animacy, the corpus has revealed that the NG go-future construction co-occurs with both animate and inanimate subjects, as shown in 13a and 13b, respectively.

(13)

As the go-future construction in English and Dutch was becoming grammaticalized, be going to and gaan first occurred with agents, that is, animate actors capable of intentional movement, before extending to inanimate subjects (Hilpert Reference Hilpert2008:106–123). A similar pattern has been observed in Afrikaans for gaan as a future auxiliary (Kirsten Reference Kirsten2018:291).

With respect to the variable intention_probability_prediction we observed in the corpus that the go-future construction expressed events that involved intentions of human agents as well as predictions of the likelihood of the event or action taking place, as in 14.

(14)

Historically, in English and Dutch be going to and gaan were first used to denote events associated with an intention (Hilpert Reference Hilpert2008:106–123). In present-day English, be going to expresses an absolute prediction (rather than pure prediction), which is based on present intentions or causes (König & Gast Reference König and Gast2018:85–87; see also Nübling & Kempf Reference Nübling, Kempf, Bisang and Malchukov2020:131 and Bybee & Pagliuca Reference Bybee and Pagliuca1987:117). Similarly, in present-day Afrikaans, gaan is used to make objective, epistemic predictions about the future (Kirsten Reference Kirsten2019:99). Because intention, absolute prediction, and pure prediction are interconnected as they succeed each other along a continuum representing the likelihood of the future event taking place, we decided to subsume these aspects under one variable.

Finally, the variable borrowed_verb was motivated by the assumption that lexical material from Afrikaans or English could trigger the choice of gehen, given that this construction may have emerged as a result of contact between NG and these languages. With respect to this variable, we observed that the go-future construction co-occurs with native German verbs, as in 15a, and (repeatedly) also with borrowed verbs, as in 15b, cf. South African colloquial English chow ‘to eat’.

(15)

In order to examine the distribution of gehen versus werden in our questionnaire data, a GLMM was fitted.Footnote 54 Given the relatively high number of intralinguistic factors we were interested in, we decided to leave out the sociolinguistic factors age, gender, and residence. This was done so as not to overload the model with explanatory variables, in view of the not overly large sample size. Instead, we included the four variables described above and two random effects (speaker and item). The dependent variable aux has two levels, namely, gehen and werden. The model specification is given in 16.

(16)

Subsequently, all variables that did not significantly improve the quality of the model were identified. This concerns all explanatory variables with the exception of one: only time_of_event significantly improves the model quality. Hence, all other fixed effects were removed. The outcome of the final model version is given in table 11.

Table 11. Results of a GLMM (auxiliary choice).

The model discriminates very well (C=0.990). 97.4% of all observations are correctly predicted by the model (this rate is significantly higher than the No Information Rate; p>0.001***). The good model quality is largely due to the random effects, which explains the big difference between marginal and conditional r 2: 0.054 versus 0.943. Particularly, the random effect speaker is of high relevance, which means that there is a lot of interindividual variation in our data. However, as mentioned above, the fixed effect time_of_event also significantly improves the model quality. The estimate of this fixed effect indicates that the probability of werden increases significantly the more distant the event is in the future. In other words, proximity to the time of speaking triggers gehen.

Aside from time_of_event, there is no evidence for the relevance of any of the other variables discussed in this section. Accordingly, our data suggest that the use of gehen in NG is not fully congruent with the use of gaan in Afrikaans, where there is no dispreference for gaan when speaking about the remote future (Kirsten Reference Kirsten2018); nor is it the same as the use of go in English, where one might expect an influence of the variable intention_probability_prediction (see, for example, König & Gast Reference König and Gast2018:84–87). Yet in some cases, the use of gehen in NG is parallel to the use of its counterparts in both contact languages, for instance, when the speaker refers to an intended action in the immediate future (see, among others, Palmer Reference Palmer1974:147, Nicolle Reference Nicolle1997, König & Gast Reference König and Gast2018:85–87 for English and Kirsten Reference Kirsten2018 for Afrikaans).

The difference between NG and SG is larger. In particular, the absence of a significant effect of animacy in our data points to a categorical difference: Go-future constructions with an inanimate subject are not possible in SG, whereas in NG it seems to be irrelevant whether the subject is inanimate or not, as shown in 10b and the corresponding examples from the corpus in 13b and 15a.

5.3 Gehen/Go/Gaan as a Future Auxiliary: A Comparative Approach

Outside of Namibia, the go-future construction has also been described for South African German varieties (see Franke Reference Franke2008:331–333 for Springbok German and Shah et al. Reference Shah, Biberauer and Herrmann2023 for Kroondal German). Its use in Springbok German is reported to be somewhat limited (for example, to constructions involving animate subjects only). However, Franke (Reference Franke2008:331) notes that this may be due to the nature of the data collected and postulates that “it may nonetheless develop into a more common future marker.” In Kroondal German, by contrast, its use is far more widespread than in Springbok German. For example, go-future constructions with inanimate subjects are possible in Kroondal German.

Given that both NG and South African German have the go-future construction and find themselves in similar contact settings, the question whether the emergence of go-future in NG is due to contact with Afrikaans and/or English is a natural one.Footnote 55 Gaan + infinitive and going + infinitive are fully grammaticalized future constructions in present-day Dutch/Afrikaans and English, respectively (Hopper & Traugott 2003, Hilpert Reference Hilpert2008, Kirsten Reference Kirsten2019). Given the parallel development of gehen into a future auxiliary in NG and South African German, it is indeed very likely that the emergence of this new feature has been reinforced by the influence of fully grammaticalized gaan in Afrikaans and going to in English. However, there seem to be additional factors that contributed to this development; language contact, in our opinion, is only part of the explanation.

In general, lexical items that enter a grammaticalization process are few, and they typically denote basic human experiences that for the most part are culturally independent. In the words of Heine et al. (Reference Heine, Claudi and Hünnemeyer1991:33), such experiences “tend to be conceived of in a similar way across linguistic and ethnic boundaries.” In light of this observation, it is not surprising that the development of future markers from verbs or phrases that denote movement toward a goal is quite common crosslinguistically. In fact, Bybee et al. (Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:253) found that “the most frequent [lexical] sources [of future grams] are movement verb constructions.” For example, in a number of Germanic languages, future auxiliaries have developed from verbs of motion (see König & Van der Auwera 2002, Harbert Reference Harbert2007).Footnote 56 In many cases, a form of go + infinitive or come + infinitive is used to express events taking place in the near future. SG is somewhat unusual when compared to its close family members within the Germanic family in its lack of use of motion verbs, such as gehen and kommen, as future auxiliaries (Nübling & Kempf Reference Nübling, Kempf, Bisang and Malchukov2020:130).

Moreover, the development of future markers from directed motion verbs or phrases follows a well-attested grammaticalization path shown in 17. This path is replicated in many of the world’s languages, including those that are genetically and areally unrelated (Bybee & Pagliuca Reference Bybee and Pagliuca1987, Bybee et al. Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994, Heine & Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2004:161–163). This means that future constructions can emerge independently of language contact (see, among others, Matras Reference Matras2020:259 for examples).

(17)

It is true, of course, that contact with Afrikaans and English may have triggered the grammaticalization process in NG; after all, “semantically similar verbs are likely to follow similar grammaticalization paths in languages in contact” (Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald, Alexandra and Robert2006:28). However, there would be nothing unusual about gehen developing into a future auxiliary in NG regardless of its contact with the other languages. In fact, it is an ideal candidate for grammaticalization: It is a movement verb that captures a fundamental culturally independent experience, that is, directed motion.

Furthermore, a gehen + infinitive construction already exists in German. This construction is typically employed to describe events that involve movement by humans and has an aspectual reading (Demske Reference Demske2020). Based on their analysis of questionnaire data, Elspaß & Möller (2003ff., map gehen + Verb) found that in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland 18a is widespread, while 18b is atypical.Footnote 57 In 18a, movement to a supermarket is implied, whereas in 18b there is normally no movement involved; heiraten ‘to marry’ implies a change of state and not a movement to another location (the examples in 18 are from Elspaß & Möller Reference Elspaß and Möller2003).

(18)

Demske (Reference Demske2020) states that gehen retains most semantic components of the full (motion) verb in cases such as 18a, and that is why 18b is rare. However, Paul et al. (Reference Paul, Thalmann, Steinbach, Coniglio, Catasso, Coniglio and De Bastiani2022) show that some speakers of SG accept gehen in combination with a verb in the infinitive, even when no movement is involved. This is the case, for example, in 19a, for which the context provided by Paul et al. (Reference Paul, Thalmann, Steinbach, Coniglio, Catasso, Coniglio and De Bastiani2022) specifies that Peter is already lying in bed. Similarly, in 19b, the specified way of movement is not gehen as in ‘to move along on foot’, if the speaker is uttering the sentence while driving to the supermarket (the examples are from Paul et al. Reference Paul, Thalmann, Steinbach, Coniglio, Catasso, Coniglio and De Bastiani2022:166; see also Nübling & Kempf Reference Nübling, Kempf, Bisang and Malchukov2020:133 on the latter use of gehen). Thus, gehen seems to be losing some of its original semantics with regard to movement (Paul et al. Reference Paul, Thalmann, Steinbach, Coniglio, Catasso, Coniglio and De Bastiani2022). Crucially, however, unlike many of the other Germanic languages, such as English and Afrikaans, SG does not allow the use of gehen as a future auxiliary, as in 19c (examples 19a,b are from Paul et al. Reference Paul, Thalmann, Steinbach, Coniglio, Catasso, Coniglio and De Bastiani2022:166).

(19)

Since a construction comprising gehen + infinitive already exists in German, NG is well positioned to develop a go-future construction. As Heine & Kuteva (Reference Heine and Kuteva2005:40–62) point out, contact-induced grammatical innovations typically do not start from scratch but build on existing material. The combination gehen + infinitive has already undergone a significant context extension in NG. Following Heine & Kuteva (Reference Heine and Kuteva2005:40–41), this can be interpreted as a change from a minor use pattern to a major use pattern.

Against this backdrop, it does not seem very surprising that NG has developed a go-future construction: A minor use pattern in German has been expanded under the influence of both major contact languages, leading to a change along a crosslinguistically very common grammaticalization path. The major obstacle to this development and the reason why the go-future is not used even more frequently in NG might be standard language ideologies and enforcement of SG norms in schools (as indicated by the “corrections” made by some participants in our questionnaire study).

Interestingly, this grammatical innovation in NG does not perfectly mirror the go-construction in either of the two major contact languages. On the one hand, just like its counterpart in English but not in Afrikaans, the go-construction in NG is mainly used for the immediate future. On the other hand, NG seems to resemble Afrikaans as regards the apparent irrelevance of the distinction between intention, absolute prediction, and pure prediction (see section 5.2). These observations concern preferences, not categorical differences. Nonetheless, this might indicate that NG has developed a specific variant of the go-construction.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we described the historical and sociolinguistic background of German in Namibia and then focused on two grammatical innovations in NG. Our analyses show that no single factor alone can adequately explain their emergence in NG, rather various factors need to be taken into account to reach a holistic understanding of these properties and to better understand the dynamics of German in multilingual Namibia.

Given the frequent and intense contact with Afrikaans and English and the structural similarity of these two contact languages with German, direct transfer of structures from Afrikaans and English may seem to be an obvious explanation for some of the standard-divergent features in NG. However, while language contact undoubtedly plays a significant role (see section 5), it cannot explain all grammatical innovations in NG (see section 4). Even in cases where language contact is an explanatory factor for the emergence of a grammatical innovation in NG, it is not the sole factor.

In both our case studies, what is crucial is that the constructions in question are not novel. Both +s+ and gehen + infinitive exist in GG, although in restricted contexts. The grammatical innovations in NG therefore did not start from scratch but picked up and built on material that already existed in the language. Speech communities in multilingual settings are generally more open to variation and may attribute reduced importance to linguistic norms, and the German-speaking community in Namibia is no exception here. Existing trends therefore gain ground in the multilingual context of Namibia, and their development may be accelerated by the availability of a parallel structure in the contact languages (as in the case of the go-future). These extensions of use are not arbitrarily applied but rather follow constraints also found in GG or patterns that exist crosslinguistically: As demonstrated above, linking elements in NG occur in contexts that would theoretically be possible in GG as well, and the go-future construction developed along a grammaticalization path attested in many different languages, irrespective of their genetic affiliation and geographic distribution. Standard language ideologies are nonetheless prevalent in Namibia to some extent and are reinforced through schooling, media, etc. This might explain why the standard-divergent constructions are not used even more frequently in NG.