1. Introduction

Eastern Yiddish relative clauses have fascinated many a scholar. They have been discussed more or less extensively in most Yiddish grammars, and certain features have become the subject of detailed studies. The extent of syntactic variation they demonstrate is particularly interesting. However, there is still relatively little known about differences between Eastern Yiddish regional dialects regarding relative clause formation. This is the topic of the present paper. In closely-related German, relative clauses are known to exhibit substantial areal differences (see, among others, Fleischer Reference Fleischer and Kortmann2004). It is therefore particularly interesting to investigate whether or not Yiddish, too, displays areal variation when it comes to relative clauses.

The structure of this article is as follows: In section 2, Eastern Yiddish relative clauses are discussed based on the existing literature, which mainly focuses on Standard Yiddish. In section 3, the materials on which this analysis is based are introduced. In section 4, the results are presented. Section 5 discusses the findings and offers some conclusions, followed by a brief outlook on Eastern Yiddish dialect syntax studies.

2. (Standard) Eastern Yiddish Relative Clause Formation

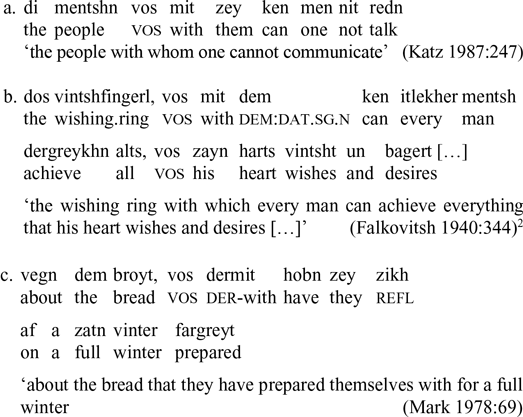

Eastern Yiddish has different strategies to form relative clauses. The choice of a particular strategy seems to be governed by both grammatical and stylistic factors. For example, in relative clauses with a relativized direct object three different relative clause markers are possible, as illustrated by the following example:

-

(1)

In example 1, the relativized noun phrase functions as the direct object of the relative clause. In this case, the relative clause can be introduced by vos, an uninflected element also used as an interrogative pronoun for inanimates (‘what’), by the inflected pronoun velkh- ‘which’, or by an inflected form vemen (nominative: ver)—the pronoun also used as an interrogative for humans (‘who’). Also, relative clauses introduced by vos can feature a resumptive pronoun that makes explicit the syntactic role of the relativized noun phrase. In subject relative clauses, this resumptive pronoun is optional according to most descriptions, and the same would hold for direct object relative clauses (not illustrated here):

-

(2)

Syntactic relations that are placed lower on the NP Accessibility Hierarchy (Keenan & Comrie Reference Keenan and Comrie1977:66) must be expressed overtly according to most grammatical descriptions. With the case-inflected pronouns velkh- and ver, this is guaranteed, as illustrated by 1 and by the following examples of relativized oblique relations (in Yiddish, whose case system is only moderately developed compared to other languages, oblique relations in the sense of Keenan & Comrie Reference Keenan and Comrie1977 are always prepositional; see example 11 for an oblique relative clause with a resumptive pronoun in the instrumental case in Polish):

-

(3)

The element vos can also appear in oblique relative clauses. As shown in example 4, a relative clause can be introduced by a pied-piped preposition that governs vos.

-

(4)

Relative clauses such as in 4 are only possible with inanimate relativized noun phrases, meaning that the same semantic restrictions as for the interrogative pronoun vos ‘what’ apply. Considering this and the fact that being preceded by a preposition is typical of (pro)nominals as opposed to complementizers (see Harbert Reference Harbert2007:429), vos in 4 is best analyzed as a pronoun. Note, however, that the analysis can be different for relative clause-introducing vos with no preceding preposition. As demonstrated by examples 1 and 2, for vos that introduces direct object and subject relative clauses, the animacy restriction does not hold.

The examples in 5 are structurally quite different from the one in 4. In 5a, vos (not preceded by a preposition) introduces the relative clause, which then features a resumptive personal pronoun governed by a preposition; this is similar to, for example, subject relative clauses, which can also contain a resumptive personal pronoun, as illustrated by 2. In 5b, vos is followed by a demonstrative pronoun, and in 5c it is followed by a “pronominal adverb”, that is, a combination of der- + preposition (compare English there-with, German da-mit, etc.).

-

(5)

This rich variety of Eastern Yiddish relative constructions leads to questions on the nature of the variation illustrated in 1–5. Grammatical restrictions apply to some of the constructions, as partially already illustrated. According to some descriptions, velkh- is used especially often with prepositions (Mark Reference Mark1942:140, Lockwood Reference Lockwood1995:126). The pronoun ver cannot be used for relativized subject noun phrases. Also, in line with semantic restrictions on the interrogative pronoun ver ‘who’, it cannot be used with inanimate relativized noun phrases (Jacobs Reference Jacobs2005:235). The question as to why a resumptive pronoun is optional in subject and direct object vos-relative clauses, as in 2, is equally intriguing: Are there linguistic factors that govern the appearance of a resumptive pronoun? Also, for oblique relative clauses, can linguistic factors be singled out that lead to the use of the pied-piped construction illustrated by 4, or the resumptive construction illustrated by 5a?

In addition to these grammatical questions, there are stylistic aspects. According to many descriptions, vos-relative clauses are most typical of spoken Eastern Yiddish and more frequent than other types (although it remains unclear whether or not this is true of all the variants). At the same time, normative grammarians of Yiddish have often expressed a certain reluctance toward velkh-relative clauses, which are quite frequent in certain types of written texts. They are seen as stylistically inferior and dubbed as a “daytshmerizm”, that is, a deliberate German borrowing, which many Yiddish stylists wish to avoid (see Wolf Reference Wolf1974:42; Birnbaum 1979:255, note 1; Lockwood Reference Lockwood1995:126).

Finally, it has been observed that vos can also introduce complement clauses (Jacobs Reference Jacobs2005:236–237; see also Lowenstamm Reference Lowenstamm1977:203; Fleischer Reference Fleischer and Kortmann2004:239, note 7; Harbert Reference Harbert2007:429–430). This is illustrated in the following example:

-

(6)

The existence of this nonrelative complementizing vos raises the question of whether or not relative vos is, essentially, the same element as the complementizer in this example (see section 5.1).

3. The LCAAJ Materials

The data collection of the Language and Culture Atlas of Ashkenazic Jewry (LCAAJ) contains copious materials on relative clause patterns in spoken Eastern Yiddish regional dialects. Only some rudimentary information on this single most important endeavor to document Yiddish linguistic and cultural geography can be provided here (see Kiefer et al. Reference Kiefer, Robert Neumann, Sunshine and Weinreich1992, hereafter LCAAJ 1, especially pp. VIII–X and 6–9 for more details on the history and methodology of this project). Between 1959 and 1972 informants were interviewed in person by trained fieldworkers, who asked questions specifically designed to elicit data on various aspects of Yiddish language and culture. These interviews represent 603 locations, some of which are represented by more than one informant (Schäfer Reference Schäfer2019:11, 15; Schäfer Reference Schäfer2020:271–272). The LCAAJ had to practice what Uriel Weinreich (1926–1967), its founder and, until his untimely death, director, called culture and dialect geography “at a distance” (LCAAJ 1:3). Most informants were interviewed far from the European locations in which they were born and had had their primary socialization, mostly in the greater New York City area.

The original data collected in the course of the LCAAJ field work have been processed and are now electronically accessible in two ways. First, there are handwritten field notes, produced by the fieldworkers in the course of the interviews (see, for example, the account by Schwartz 2008, especially pp. 283–284, on some of the difficulties of producing a transcription during the interview). The answers were noted in the form of a transcription that was designed to serve the needs of early computer-ization (see Sunshine et al. 1995, hereafter LCAAJ 2:3; the transcription and notation system is documented in LCAAJ 2:20–24). For instance, as the visually most salient feature, only capital letters were used, and certain vowels and articulatory modifications were rendered by numbers (for example, 3 corresponds to IPA [ə]; 8 indicates fronting when placed after a vowel symbol and palatalization when placed after a consonant symbol). Since 2018, these field notes (“answer sheets”) have been scanned and made electronically available by Columbia University Libraries, where the LCAAJ archives are kept. Second, the interview ses-sions were taped in their entirety. After the interviews, the tape recordings were used to edit the field notes to some extent (see Schwartz 2008:280). Many of the tape recordings are electronically available through Evidence of Yiddish Documented in European Societies (EYDES; see also Herzog et al. Reference Herzog, Ulrike Kiefer, Putschke and Sunshine2008).

The LCAAJ questionnaire tasks are identified by a six-digit code indicating the sheet number in the field notes (first three digits) and the question number on the sheets (second three digits; see LCAAJ 2:4). For instance, task number 146 050 identifies a relative clause with a subject as the relativized noun phrase: The snake is an animal that bites (see LCAAJ 2, p. *53). This referencing system is used in the remainder of the paper.

Given today’s electronic accessibility of the field notes and tape recordings, the modern researcher has to decide which of the two formats to use. From a practical point of view, the digitized field notes are much more easily accessible. The field notes and their digital presentation are searchable using the six-digit code system just described, which allows one to efficiently navigate the vast material. In contrast, many of the tape recordings are of poor sound quality (see below), and for the time being, only a small portion can be searched using the six-digit codes. Thus, navigation of the recordings is time-consuming since there is no easy path from a questionnaire task to its position in the sound files.

For the present analyses, I primarily rely on the digitized field notes. Thanks to Lea Schäfer and her Syntax of Eastern Yiddish Dialects (SEYD) project (see also Schäfer Reference Schäfer2019, Reference Schäfer2020), transliterations of the field notes’ versions of the translations of relevant tasks have been made available to me. The data presented below have been classified on the basis of these versions. In problematic instances I compared the trans-literations with the scans of the field notes and, in a limited number of cases, with the sound recordings. For convenience, when examples from the field notes are quoted, the original transcription is converted into a more readable version (see also Schäfer Reference Schäfer2020:275–276). For example, the field notes’ D1 S+LONG 1Z A XAJ1 VUS BAST (146 050, 48283 Pishchanka) is rendered as di šlong iz a xaji vus bast ‘The snake is an animal that bites’.Footnote 3 My conversion leaves out some phonetic detail, which is not necessary for a grammatical analysis. Also, to facilitate reading, I insert spaces if there are none in the field notes (unless cliticization and possibly assimilation takes place, in which case = is added in the glosses to separate host and clitic; see section 4.1).

Although my choice of the field notes is motivated by practical reasons, a brief reflection on the quality of both LCAAJ data formats is in order. As shown below, some of the field notes are incomplete. Needless to say, it would be desirable to complete them, which would usually be possible, even if time-consuming, using the tape recordings.Footnote 4 However, the sound quality is often weak by today’s standards. As discussed by Peltz (2008:256), high frequencies are often not preserved, making, for instance, the analysis of sibilants (Peltz’s topic) difficult. Given that the field-workers had access to much more information than is available through the tape recordings in their present-day state, Peltz (2008:266) feels that analyses “should depend on the fieldnotes, accompanied by in depth listening to recordings from a few selected locations and occasionally checking the recordings for seeming inconsistencies in the fieldnotes.” This is the approach taken in this paper.

4. Results

The LCAAJ (Eastern Yiddish) questionnaire contains two tasks on relative clauses, one displaying a relativized subject and one a relativized oblique noun phrase. The informants were given the relative clauses in English—or in another language (see section 5.2)—and asked to translate them into their Yiddish dialects. This paper discusses the Eastern Yiddish data for these two tasks for the first time, and the results are geographically visualized in the form of maps.Footnote 5

In the process of data classification, it became apparent that the field notes do not feature a relative clause in many instances, and some of the responses are fragmentary. For example, for task 146 050 location 53271 Lenina only notes a translation of ‘the snake’ (der šlajng). Responses not displaying a relative clause are not discussed in the remainder of this paper. All responses displaying a complete relative clause were analyzed, even if only part of a task had been translated and/or noted. For instance, the field notes for location 55257 Šimonys only provide the matrix noun and the relative clause of task 146 050, leaving out the matrix clause’s predication ‘is an animal’: The version der šlank vos bajst is equivalent to ‘the snake that bites’. Such translations were taken into account, as long as the structural properties of the relative clauses were unequivo-cally identifiable.

Usually the field notes only have one (relevant) answer, but for some locations variation is noted. For instance, the informant from location 48281 Soroca produced a šlong iz a xaji vuzi bast/vus bast, that is, vos both with and without a resumptive personal pronoun. For the statistics, such cases are counted separately for each relative clause type they contain. There are thus usually more attested constructions than sensible answers in the field notes. As to the maps, however, for technical reasons, I follow the practice of Lea Schäfer in only mapping the version first uttered by the informant.

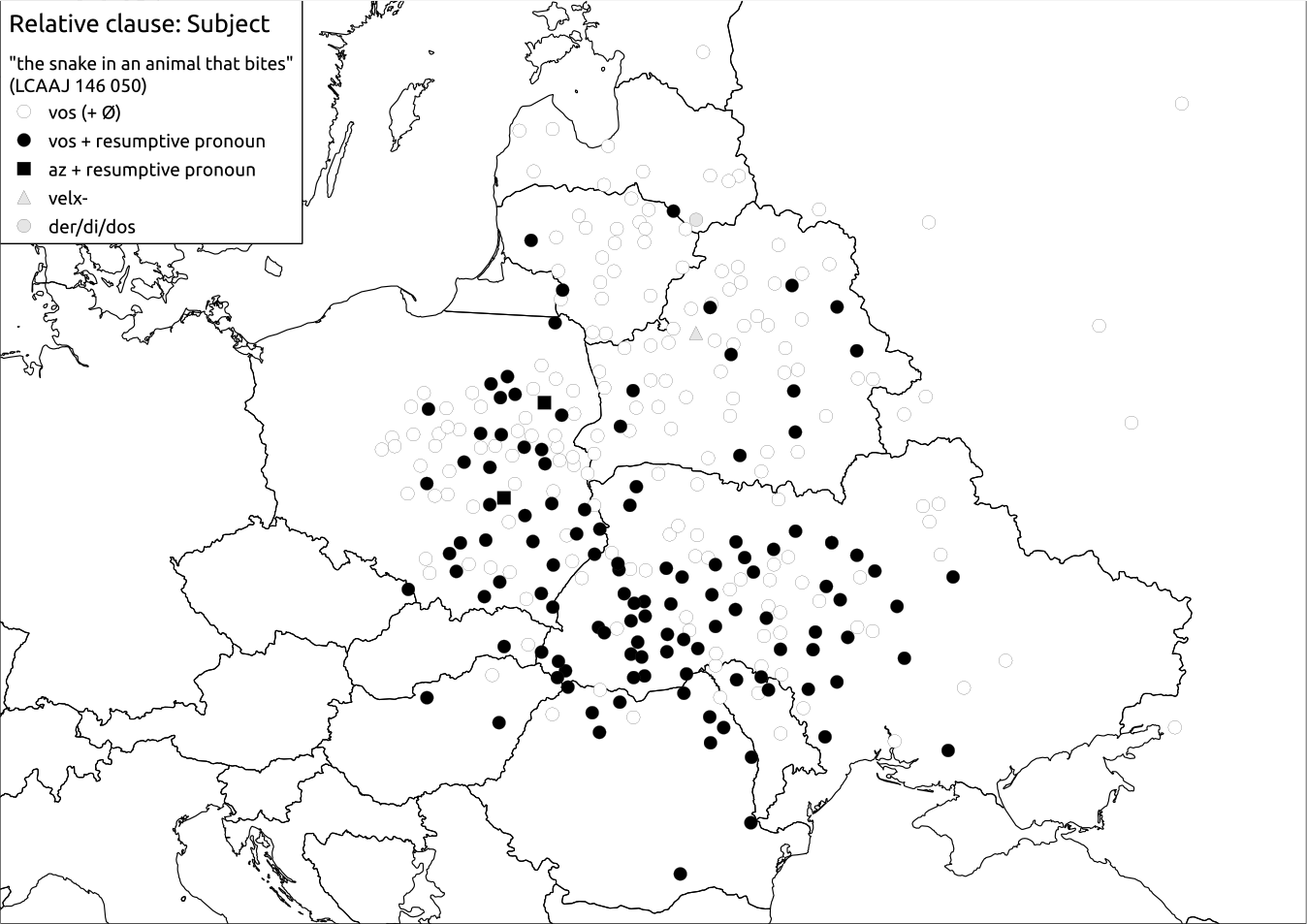

4.1. Subject Relative Clause

As a subject relative clause, the questionnaire has the snake is an animal that bites (146 050; LCAAJ 2:*53). The central aspect of my data classification is the element introducing the relative clause. In addition to vos, the complementizer az ‘that; as’ is attested. For vos and az, combi-nations with resumptive personal pronouns are encountered (as a matter of fact, az is always accompanied by a resumptive pronoun). Two pronouns also occur: velx- and der/di/dos, the latter also functioning as an article and weak demonstrative. The types are illustrated by one example each:

-

(7)

As the example in 7b from location 50281 Chudniv illustrates, the resumptive personal pronoun can be subject to cliticization, while the final -s of vos can undergo anticipatory voicing assimilation (see Jacobs Reference Jacobs2005:129–130). This relative clause corresponds to Standard Yiddish vos zi bayst. Note that the relativized noun can vary in gender—compare the feminine article di in 7a (48283 Pishchanka) and 7d (54262 Valozhyn) versus the masculine dər/der in 7b (50281 Chudniv), 7c (52228 Jabłonka Kościelna), and 7e (55268 Daugavpils). Furthermore, in some instances the resumptive pronoun seems to agree with the predicate noun in the matrix clause, which can also vary in gender—compare the feminine nouns xaji/xajə (Standard Yiddish khaye) in 7a,b,d versus the masculine noun sojni (Standard Yiddish soyne) in 7e versus the neuter noun bašefeniš (Standard Yiddish bashefenish) in 7c (but see note 6 on the problems with establishing the gender of these nouns). Given this gender variability, it is no surprise that resumptive pronouns of all three genders are encountered.Footnote 6 My data classification simply registers the presence or absence of a resumptive pronoun, irrespective of its gender.

While vos-relative clauses (with and without a resumptive pronoun) and velx-relative clauses are known to exist in Standard Yiddish (see section 2), to my knowledge, az-relative clauses have not previously been described for Yiddish. The same holds for a relative pronoun der/di/dos.

The field notes document 393 responses. Of these, 90 responses are fragmentary or unclear in that these versions do not provide (sufficient) information on the relative clause. The following table details how many of each of the five types are found in the data (as some locations display variation with more than one type, there are more than 303 answers in total).

Table 1. Types of subject relative clauses (LCAAJ task 146 050).

Figure 1. Areal distribution of subject relative clause types (LCAAJ task 146 050).

As table 1 makes clear, relative clauses introduced by vos constitute the vast majority of examples. Of the two vos types, vos on its own (with no resumptive pronoun) is most widespread (with almost 60%). The combi-nation with the resumptive personal pronoun occurs in almost 40% of the locations. The LCAAJ data thus confirm that the vos types, dubbed most widespread in the literature and characterized as “best” by many stylists, are indeed common. All other types are very rare. For those not discussed in the grammatical literature, it remains to be seen whether their existence can be corroborated by other data types. Note that the once-attested der/di/dos type structurally corresponds to the most usual Standard German relative clause pattern. (Baltic) German influence in the respective location 55268 Daugavpils, in present-day Latvia, seems possible.

The map in figure 1 illustrates the areal distribution. For the two main types, it turns out that vos (+ Ø) can be found in Central Eastern Yiddish, Southeastern Yiddish, and Northeastern Yiddish, i.e., in all three major dialect areas usually recognized for Eastern Yiddish: It predominates in the north, in present-day Latvia, Lithuania, and Belarus (and in the scattered locations in Russia, which are beyond the Pale of Settlement), while it is somewhat less widespread in the west and south. The vos + resumptive pronoun type is areally widespread too. However, it seems especially prominent in the west and south, in present-day (eastern) Poland and Ukraine, while it is rarer in the north and not attested in the easternmost Russian locations. As in Standard Yiddish, in which both types are accepted, the two types seem to co-occur in the dialects of Yiddish. However, vos without a resumptive pronoun predominates in the north, while vos + resumptive pronoun seems to be particularly prominent in the west and south. So, although both types do indeed co-occur, there are centers of gravity in their respective areal distributions.

4.2. Oblique Relative Clause

The LCAAJ questionnaire features the pen with which he writes (174 110; LCAAJ 2:*63) as an oblique relative clause. Here, in addition to versions with no or fragmentary relative clauses the informants produced translations that can be classified as relative clauses, but not as oblique relative clauses. Most interesting in this respect are responses in which the preposition that governs the relative pronoun in the English version is realized in the matrix clause, as in mi dər pen vos ər šrajpt lit. ‘with the pen that he writes’ (49237 Yavoriv).Footnote 7 At first glance, one might be tempted to see this as an instance of the so-called relative attraction, or attractio relativi known to exist in many old Indo-European languages, as the element encoding the syntactic role of the relativized noun phrase seems to be moved from the relative into the matrix clause. However, I consider such responses irrelevant for my purposes since the relative clause itself features a direct object rather than an oblique as the relativized noun phrase.

In many instances, the field notes also feature direct object relative clauses with no preposition in the matrix clause. Sometimes such responses are quite complete or even contain more information in comparison to the original version, as in di pen vus ər šrapt is cibroxn lit. ‘the pen that he writes is broken’ (48281 Soroca), which makes it unlikely that the preposition is only missing in the field notes. In other cases, parts of the original are missing. Thus, in di pen vos ər šrapt lit. ‘the pen that he writes’ (47272 Iaşi), the preposition might have gone unrealized by the informant, or it might not have found its way into the field notes. As the present analysis is specifically interested in oblique relative clause constructions, all examples of other types of relative clauses are disregarded. Methodologically, it seems most natural to interpret such versions as avoidance strategies. Many informants may have felt uncomfortable with the “complicated” oblique relative clauses, which is an interesting finding in itself.

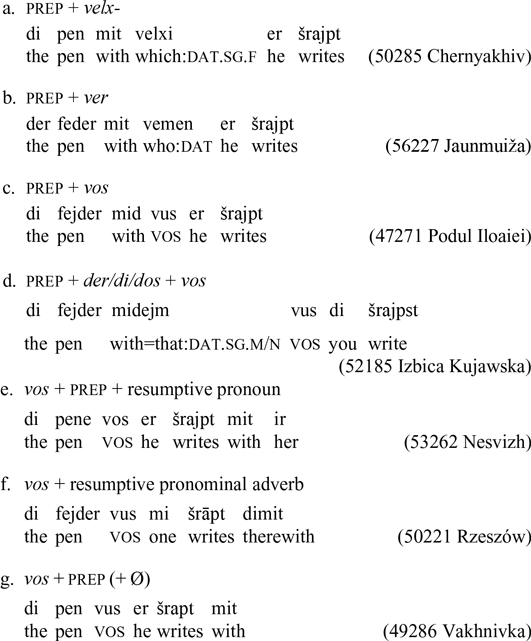

The responses included here are true oblique relative clauses in displaying the preposition mit ‘with’ within the relative clause. They come in seven different types, which are illustrated below:

-

(8)

Some of these seven types—the ones represented by 8b,d,g—are missing in the descriptions of (Standard) Yiddish and thus deserve a special comment. As discussed in section 2, prep + velx- in 8a is one of the types that are known to exist in Standard Yiddish. The type in 8b, prep + ver, is also known, in principle. However, it is usually described as being restricted to human relativized nouns (see, among others, Jacobs Reference Jacobs2005:235). The type in 8c, prep + vos, is described in some sources as one possibility to form oblique relative clauses, as illustrated by example 4. The type in 8d, prep + der/di/dos + vos, is somewhat unexpected for Eastern Yiddish. It corresponds structurally to relative clause types in certain German dialects, which also feature the combination prep + der/die/das + was (see Fleischer Reference Fleischer and Kortmann2004:219–220). Of the grammatical descriptions of Yiddish known to me, only Wiener (Reference Wiener1893:67) briefly mentions that vos “may be strengthened by the demonstrative der,” but note that his only example features a subject, not an oblique relative clause (der top der wos schtejt oufm tisch ‘the pot that stands on the table’). Of the three constructions introduced by vos (without a preceding preposition) in 8e–g, the first and second one, in which the relative clause features a preposition followed by a resumptive personal pronoun or a pronominal adverb, are well described (see section 2, examples 5a,c). However, the last construction, 8g, which features a seemingly stranded preposition within the relative clause, is unexpected, as Yiddish is not known to allow preposition stranding (see section 5.1).

There are 333 field notes with a response to this survey question. Upon elimination of the fragmentary data and the nonoblique relative clauses, 264 answers remain. Each of these features an oblique relative clause or provides two oblique relative clause construction variants: In 14 field notes, prep + velx- and prep + vos were produced together, as in di pen mit velxər/mid vus ər šrapt (49285 Kalynivka).

Table 2. Types of oblique relative clauses (LCAAJ task 174 110).

Figure 2. Areal distribution of oblique relative clause types (LCAAJ task 174 110).

As table 2 shows, the first type, prep + velx-, makes up the majority of all relative clauses used, with more than half of all answers, followed by prep + vos, with a little more than a third of all answers. The vos type with a resumptive pronoun (vos + prep + resumptive pronoun) is third in frequency (7.9%). All other types are quite rare, but nevertheless the combination prep + der/di/dos + vos (six attestations) and the “prepo-sition stranding” type (four attestations) have been produced more than once. It remains to be seen whether the rarely produced con-structions can be found in other data types.

The areal distribution of the seven types is illustrated in figure 2. The two most frequent types, prep + velx- and prep + vos, overlap areally to a considerable extent. The resumptive strategies, however, seem to be most typical for the southern half of the area of investigation, in Central Eastern Yiddish and Southeastern Yiddish. This also holds for the “preposition stranding” type, which, as argued in section 5.1, can also be analyzed as a resumptive strategy.

5. Discussion

5.1. Vos, Pronominal Resumption and “Preposition Stranding”

In the construction represented by example 4, which is the second most frequent in the LCAAJ oblique relative clause data, vos is pied-piped. In this case, vos is governed by a preposition and is subject to the same semantic restrictions as the interrogative pronoun vos, namely, it may not be used for noun phrases with animate referents. Therefore, it makes sense to analyze it as a pronoun. All other instances of vos, however, are better analyzed as a complementizer or, in traditional terminology, a subordinating conjunction (see, for example, Lowenstamm Reference Lowenstamm1977:200, Fleischer Reference Fleischer and Kortmann2004:223–224, Jacobs Reference Jacobs2005:235, Harbert Reference Harbert2007:429). It has no restrictions with respect to the animacy of the relativized noun, does not encode case, and can co-occur with resumptives making explicit the syntactic role of the relativized noun.

As discussed in section 2, in addition to relative clauses proper, nonrelative complementizing vos-clauses, as illustrated in example 6, can be found. This leads to the question of whether or not relative clause-introducing vos can be analyzed as a general complementizer, which introduces both complement and relative clauses.

From this perspective, it is interesting to investigate in which Yiddish regional dialects general complementizing vos can be found. LCAAJ questionnaire task 103 100 provides relevant data (see also Schäfer Reference Schäfer2020:278–279). Here the informants were asked to translate the English sentence I am glad that he is eating into their Yiddish dialect (see LCAAJ 2:*40). For this task, 397 field notes display some answer, with 375 of them having one or more than one complementizer. As the following synopsis illustrates, three complementizers were used (the total number of answers is higher than 375, since some locations provided more than one complementizer). Examples are given in 9 and the statistics in table 3.

-

(9)

Table 3. Different complementizers used in response to LCAAJ task 103 100.

As table 3 makes clear, dos is very rare (note that most locations, as 45284 Galați, display the form das, not dos, which hints at this comple-mentizer’s likely origin: German dass). The other two complementizers are almost equally frequent, however. The areal distribution of the three complementizers is illustrated in figure 3. Based on this map, the general complementizer vos occurs in all major Eastern Yiddish dialect areas, although it is especially typical of Southeastern and neighboring central Northeastern Yiddish.

In light of the finding that the general complementizer vos is attested in the entire Eastern Yiddish area, it seems plausible that relative clause-introducing vos and complementizing vos are basically the same element. The two clause types overlap areally and serve the same basic function, namely, introducing a subordinate clause, be it a relative clause or a complement clause.

Figure 3. Areal distribution of different complementizers (LCAAJ task 103 100).

It has been shown that ca. 40% of all subject relative clauses display promominal resumption. The proportion of oblique relative clauses with resumption is considerably lower: If one assumes that examples 8e–g all contain a resumptive element, then only about 10% of all oblique relative clauses display some kind of resumption, with the remaining 90% displaying pied-piping. This is a straightforward approach for 8e and 8f, which contain a resumptive pronoun and a resumptive pronominal adverb, respectively. Example 8g, which resembles a structure with preposition stranding, is discussed immediately below.

As discussed above, there are good reasons to analyze (relative) clause-introducing vos as a complementizer (the only instance of pro-nominal vos being the one used in the pied-piped construction). As to the potential cases of preposition stranding, such as in 8g, this analysis is also applicable. It is commonly assumed that Yiddish does not allow preposition stranding (Harbert Reference Harbert2007:455 specifically on relative clauses and Jacobs Reference Jacobs2005:232 on the impossibility of preposition stranding generally). I propose that in examples reminiscent of preposition stranding, such as 8g (di pen vus er šrapt mit lit. ‘the pen that he writes with’), the preposition has an empty argument: First, as discussed above, there are good reasons to analyze (relative) clause-introducing vos as a complementizer. There are no reasons to treat vos in cases such as 8g any differently; here, too, it should be analyzed as a complementizer, which, crucially, is not moved. Second, in examples such as 8e the preposition mit can be followed by a resumptive pronoun. For 8e and 8g I propose the analyses in 10a and 10b, respectively. The two constructions are entirely parallel, except for the fact that 8e/10a displays an overt argument in the form of the resumptive pronoun, while there is no overt argument in the respective position in 8g/10b.

-

(10)

With this analysis, the generalization that Yiddish does not feature preposition stranding is still valid. My analysis of 8g/10b is supported by the fact that with the exception of one instance in Hungary, three of the four examples of this construction occur in the area where the construction in 8e/10a is also used (with a higher frequency). It seems reasonable to conclude that constructions such as 8g/10b exhibit a nonovert prepositional argument, not preposition stranding. Interestingly, in certain Western Yiddish and German dialects, the cognate preposition mit ‘with’ is also known to occur with no overt complement, which is a unique behavior of prepositions in these dialects. However, note that in the relevant examples in Western Yiddish and German dialects, mit is combined with a cognate of German wo or Yiddish vu ‘where’, not ‘what’ (see Fleischer Reference Fleischer2014:152).

5.2. Methodology: Possible Priming Effects

The LCAAJ subject relative clause data confirm what is known from the literature on Eastern Yiddish relative clauses to a large extent, namely, that vos (with or without a resumptive pronoun) is the most common and widespread relativizing element. When it comes to the oblique relative clause, however, there is some discrepancy between the existing gram-matical descriptions and the LCAAJ data. Many Yiddish grammars, provided they explicitly discuss oblique relative clauses, mention the vos + prep + resumptive pronoun (or pronominal adverb) construction as the only type of relative clause that involves vos (Wiener Reference Wiener1893:67; Weinreich 1949:331; Mark Reference Mark1978:69, 245; Katz Reference Katz1987:247; Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Prince, van der Auwera, König and van der Auwera1994:416–417). It is therefore somewhat unexpected that this type is attested in less than 10% of the LCAAJ locations, with an areal preference for Central Eastern Yiddish and Southeastern Yiddish. However, the areal distribution of this type confirms to some extent what is known about the composition of Standard Yiddish. Standard Yiddish grammar is closer to that of Southeastern Yiddish and Central Eastern Yiddish, while the pronunciation is closer to Northeastern Yiddish (see Katz Reference Katz, Besch, Knoop and Putschke1983:1033–1034). A preference for resumptive pronoun construc-tions in Standard Yiddish fits this pattern.

As for velx-relative clauses, the LCAAJ data confirm, at least at first glance, that this type is primarily used for prepositional relations, as stated by Mark (Reference Mark1942:140) and Lockwood (Reference Lockwood1995:126). Velx- was used most frequently in oblique relative clauses, but it was only uttered twice in a subject relative clause. Thus, its status as a “daytshmerizm” notwith-standing, there might be a certain division of labor between vos and velx-.

However, relative velx- might, in reality, be less prominent, if possible effects of priming by the original versions are considered. It is a well-known fact that a survey’s method influences its results. To collect data on the two relative clauses discussed here, the fieldworker would utter each relative clause in English or another language, and then ask the informant to translate it into their Yiddish dialect.Footnote 8 The two tasks on relative clauses are thus translation tasks. Therefore, it makes sense to compare more thoroughly the structures of the original versions and the translations in this respect. As English was used in the majority of the interviews, I limit the discussion to comparisons with the English versions.Footnote 9

The English version of the LCAAJ subject relative clause, The snake is an animal that bites (146 050; LCAAJ 2:*53), shows a relative clause introduced by that. This relative that is not inflected for case, number, or gender, and there are good reasons to analyze it as a complementizer (see Harbert Reference Harbert2007:430). Of the five constructions offered by the informants as translations for LCAAJ task 146 050, the one with vos with no resumptive pronoun (see 7a above) is structurally closest to the English version. The informants uttering this type made the least effort in structural terms: As in the English version, they used a complementizer (that > vos) with no additional elements, thus employing a gapping strategy. Informants uttering vos + resumptive pronoun (see 7b), in contrast, deviated from the English version in inserting a resumptive pronoun. The other three (rare) patterns deviated from the original in using a different complementizer, arguably less close to English that, plus adding a resumptive pronoun (see 7c) or using a pronoun instead of the complementizer (see 7d,e).

Consider now the structure of the oblique relative clause. In the English version the pen with which he writes (174 110; LCAAJ 2: *63), the preposition is pied-piped and governs which. Although the English which displays no inflection, it can be analyzed as a pronoun, as it can be pied-piped and be the object of a preposition (these are common charac-teristics of (pro)nouns; see Harbert Reference Harbert2007:425). Of the various translations offered by the informants, the Yiddish construction prep + velx- in 8a is structurally closest to the English version, except for the fact that English which does not inflect for case, number, and gender, while Yiddish velx- does. This is also the most frequent construction in the LCAAJ data.

For both the subject and the oblique relative clause, the most frequent construction offered by the informants corresponds best to the English original. To produce these constructions, the informants arguably made the least effort in structural terms. While this finding need not mean that the translations with the same structures as the original are ungrammatical, it seems plausible that the deviating constructions are especially typical for the informants’ respective dialects. Such methodological assessment is not new in dialect syntax studies: “If another variant turns up than the variant in the example, one has a strong indication that not the variant in the example, but the variant of the translation occurs in the dialect under investigation” (Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen1993:348).

The constructions that deviate from the original versions are thus more telling than the constructions corresponding to the original versions. From this perspective, the fact that vos + resumptive pronoun is widely used in the subject relative clause by speakers in certain locations should be seen as evidence that this construction is indeed typical for those locations. Similarly, in case of the oblique relative clause, it can be seen as significant that prep + vos, the second most frequent construc-tion, is widely used. These constructions seem to be especially typical of spoken dialectal Yiddish, as they were produced “despite” the original. Also, the assessment of velx-relative clauses as not being particularly entrenched in Yiddish dialects may still be valid, despite that fact that this type predominates in the LCAAJ oblique relative clause data. Here, it corresponds to the original.

In addition to priming effects due to the original, given the sociolinguistic situation of most of the LCAAJ informants one might suspect English influence in some of the produced relative clause patterns. The four cases of “preposition stranding” seem particularly suspicious in this respect. To assess this question, it would be necessary to investigate whether the four informants uttering the examples were particularly prone to influences of English and what the exact elicitation situation was like. I compared the field notes with the sound file for 51196 Piotrków Trybunalski, and in this case the informant is definitely not just replicating in Yiddish the pattern of the English relative clause uttered by the fieldworker. The tape recording clearly confirms the field notes: The fieldworker says “the pen with which he writes”, not “the pen that he writes with” or “the pen he writes with”.

5.3. Convergence of Yiddish with Coterritorial Languages

The LCAAJ data discussed above show some areal distributions that are reminiscent of the areal distributions of corresponding constructions in the coterritorial Slavic languages. This holds for complementizing (nonrelative) vos, that is, vos introducing complement clauses, which is discussed first, and for the occurrence of resumptive personal pronouns.

As discussed briefly in section 2, vos is first and foremost an inter-rogative pronoun for inanimate entities (‘what’), which acquired two new functions: It can now introduce relative clauses in all Eastern Yiddish regions, and it can function as a general complementizer (‘that’) particu-larly in some Eastern Yiddish regions. Interestingly, the use of vos ‘what’ as a general complementizer (‘that’) is more widespread in South-eastern and central Northeastern Yiddish—that is, in the regions where roughly coterritorial Ukrainian and Belarusian also use interrogative pronouns ščo and što, respectively, as complementizers. By contrast, Central and western Northeastern Yiddish as well as coterritorial Polish do not use interrogative pronouns as general complementizers (vos and co, respectively) but instead use az and że, respectively, which are most naturally rendered as ‘that’. (Note, however, that in Yiddish this is a tendency rather than a strict grammatical rule—as figure 3 illustrates, there are instances of vos in the az area and vice versa, but different regions show preferences for vos or az).

The following table illustrates the use of these elements as inanimate interrogative pronouns (‘what’), relativizers, and general complemen-tizers (‘that’) in the Slavic languages coterritorial with Yiddish (see Minlos Reference Minlos2012:85).

Table 4. Inanimate interrogatives, relativizers, and general complementizers in Yiddish and Slavic coterritorial languages.

Table 4 shows that the functional distribution of vos and az in the Yiddish regional dialects mirrors the functional distribution of their counterparts in the Slavic coterritorial languages. In Southeastern Yiddish and central Northeastern Yiddish, vos serves all three functions, including that of a general complementizer, much in the same way as Ukrainian ščo and Belarusian što; in the remaining Yiddish dialects, vos, as Polish co, primarily serves as an inanimate interrogative and a relativizer, but less so as a general complementizer. For this function these Yiddish dialects prefer az; in other words, Yiddish seems to make the same distinction between vos ‘what’ and az ‘that’ as Polish does between co ‘what’ and że ‘that’ (note, however, again, as discussed above, that in the Yiddish dialects, these are preferences rather than strict rules).

Interestingly, certain Slavic regional dialects differ from the pattern shown in table 4. As a matter of fact, there are some marginal deviations as far as the general complementizer function is concerned. Thus, according to Bevzenko (Reference Bevzenko1980:172), że, instead of a dialectal cognate of ščo, is attested in Southwestern Ukrainian dialects. Bandriv’skyj et al. 1988 (map 256), which covers, roughly, the westernmost third of the Ukrainian-speaking territory, attests że in the areas around Užhorod, L’viv, and in a few further regions. Similarly, there are some Polish dialectal examples of co in the function of a general complementizer, as discussed by Kuraszkiewicz (Reference Kuraszkiewicz1971:166–168). However, many of those examples are attested in peripheral areas and are crucially absent in the central regions of Polish dialects (in accordance with this geographical distribution, Kuraszkiewicz Reference Kuraszkiewicz1971:170 thinks complementizing nonrelative co to be due to either Russian or German influence). Disregarding these exceptions in peripheral dialects, it generally holds that Ukrainian ščo and Belarusian što can be used in all three functions, while Polish co does not occur as a general complementizer ‘that’, for which function Polish has że.

A similar convergence is observed in the use of resumptive personal pronouns in some relative constructions.Footnote 10 This is especially true for relative clauses introduced by vos in combination with a resumptive pronoun. In the LCAAJ data, resumptive pronouns are especially promi-nent in Central Eastern Yiddish—roughly coterritorial with Polish, and Southeastern Yiddish—roughly coterritorial with Ukrainian, both in subject and oblique relative clauses. There are many arguments for seeing the Eastern Yiddish vos + resumptive pronoun construction as an example of a structural borrowing from Slavic: Polish and Ukrainian display exact structural parallels to this construction (see Fleischer Reference Fleischer2014:148–150 and Danylenko Reference Danylenko, Grković-Major, Hansen and Sonnenhauser2018:366–370, the latter providing a rich array of Ukrainian dialect examples). The following example featuring an oblique relative clause could be a Polish translation of LCAAJ task 174 110. As in the Yiddish equivalent di pene vos er šrajpt mit ir (53262 Nesvizh), it features co and a resumptive pronoun, the only difference being that Polish shows a bare instrumental pronominal form, while Yiddish would use a preposition governing the resumptive pronoun:

-

(11)

Interestingly, resumptive pronouns in relative clauses are more common in Polish and Ukrainian than they are in Belarusian. According to Minlos (Reference Minlos2012:75), although što-relative clauses are well attested in Belarusian, they do not feature resumptive pronouns, unlike their Polish and Ukrainian equivalents. Admitting that this generalization is not entirely accurate, as there are dialectal Belarusian examples of što-relative clauses with resumptive pronouns (see, among others, Fleischer Reference Fleischer2014:148, Danylenko Reference Danylenko, Grković-Major, Hansen and Sonnenhauser2018:373 and references cited therein, the general observation seems valid nevertheless, as resumptive pronouns are rarer in Belarusian than they are in Polish and Ukrainian. This difference in prominence is reminiscent of the areal distribution of resumptive pronouns in Yiddish, where Central Eastern Yiddish and Southeastern Yiddish display more resumptive pronouns than Northeastern Yiddish (roughly coterritorial with Belarusian and Lithuanian). If this is correct, the preference for resumptive pronouns in vos-relative clauses in Central Eastern Yiddish and Southeastern Yiddish mirrors the areal distribution of resumptive pronouns in ščo/co-relative clauses in the coterritorial Slavic languages.Footnote 11

Note, however, that despite the appearance of a certain convergence, the Yiddish patterns are not exactly identical to the Slavic ones. For instance, the Slavic languages only rarely use resumptive pronouns in subject relative clauses (see Minlos Reference Minlos2012:78), unlike Yiddish. Although some Slavic varieties do not allow resumptive pronouns in subject relative clauses (see Guz Reference Guz2017:97), some historic or dialectal examples can be found in others (see, for instance, Fleischer Reference Fleischer2014:148, examples 23–25, or Danylenko Reference Danylenko, Grković-Major, Hansen and Sonnenhauser2018:369, example 9). A wider use of subject resumptive pronouns in Yiddish would be consistent with the fact that Polish, Ukrainian, and Belarusian are null subject languages, while Yiddish is not (see Fleischer Reference Fleischer2014:150).

In summary, the findings based on the LCAAJ data show that the preference for complementizing (nonrelative) vos and for resumptive pronouns in vos-relative clauses in the Yiddish dialects mirrors, to some extent, the patterns in the coterritorial Slavic languages. Fleischer (Reference Fleischer2014:157) argues that Eastern Yiddish vos-relative clauses emerged due to contact with Medieval Polish and that this construction is not directly dependent on the contemporary coterritorial Slavic languages. However, the current study suggests that Yiddish is influenced by more recent language convergence on a local level when it comes to the finer distributional properties of Yiddish relative and complement clause constructions.

6. Outlook: Yiddish Dialect Syntax

The empirical findings on the areal distribution of the constructions discussed in this paper could only be obtained thanks to the rich, areally dense LCAAJ data set, which covers much of the historic Eastern European area where Yiddish was spoken. While the past decades have seen the establishment of dialect syntax studies for many West Germanic languages, Yiddish has largely been missing here. As I hope to have shown, an areal approach to Yiddish syntax promises interesting results, and it can be expected that the SEYD project will further contribute to this promising field of study.