1. INTRODUCTION

The position of wh-phrases in French wh-questions is the centre of much attention for at least two reasons. First, Colloquial French is usually described as a ‘mixed’ language, showing both in-situ and ex-situ wh-phrases in matrix information-seeking questions (e.g., Dryer, Reference Dryer, Dryer and Haspelmath2013) as compared to other languages that show either only wh-in-situ items (e.g., Chinese; Huang, Reference Huang1982) or only wh-ex-situ items (e.g., English; Nguyen and Legendre, Reference Nguyen and Legendre2022).Footnote 1 Second, French-speaking children and adults differ in their distribution of wh-positions. It is usually reported that children utter more wh-in-situ questions than adults (Zuckerman and Hulk, Reference Zuckerman and Hulk2001; Strik, Reference Strik2007; Strik and Pérez-Leroux, Reference Strik and Pérez-Leroux2011; Becker and Gotowski, Reference Becker and Gotowski2015; Thiberge, Reference Thiberge2020). This article aims to explain this early prevalence of the wh-in-situ position and the difference with adult productions. It will statistically investigate the production of matrix wh-questions in 16 typically developing French L1 children during their three kindergarten years. The investigation will pinpoint two factors at the syntax-semantics interface that account for the prevalence of the wh-in-situ position in child but not adult French, namely the Fixed be structure c’est ‘it is’ and the adverb là ‘there’. An attempt at the unification of these in-situ question triggers under an umbrella category (deixis) will be made as well as an examination of the counter-examples. The data will also draw our attention to a third factor: the morpho-syntactic difference between in-situ quoi ‘what’ and ex-situ qu’est-ce que ‘what is it that’, and the gradual emergence of the latter throughout the three-year kindergarten period.

1.1 The target language

In this contribution, we will leave Standard French aside, because we assume that preschool children are mainly exposed to and hence initially acquire Colloquial French (e.g., Hamlaoui, Reference Hamlaoui2011). Colloquial French is often but not always described as a mixed language. Baunaz (Reference Baunaz2011, Reference Baunaz2016) compared ‘Non-Standard Colloquial French’ (NSCF) with Chinese and described both as wh-in-situ languages with covert wh-movement. The author also proposed that NSCF displays three types of in-situ wh-phrases: one non-marked and two marked types (Types 1, 2 and 3, respectively). Type 1 in-situ wh-phrases are analysed as covert Split-DPs (i.e., variables with a phonologically null interrogative operator). They are non-presuppositional and have a rising intonation. Types 2 and 3 in-situ wh-phrases have specific and partitive interpretations, and fall-rise and falling intonations, respectively. Both entail covert movement of the entire wh-phrase. Furthermore, Baunaz (Reference Baunaz2011: 75) described in-situ and ex-situ structures in NSCF as syntactically ‘similar’, with identical processing loads (following Adli, Reference Adli2006), and she related the difference in overt versus covert movement to ‘interpretation, as witnessed by intonation’. We will elaborate on Baunaz’s (Reference Baunaz2011, Reference Baunaz2016) proposal in Section 4.

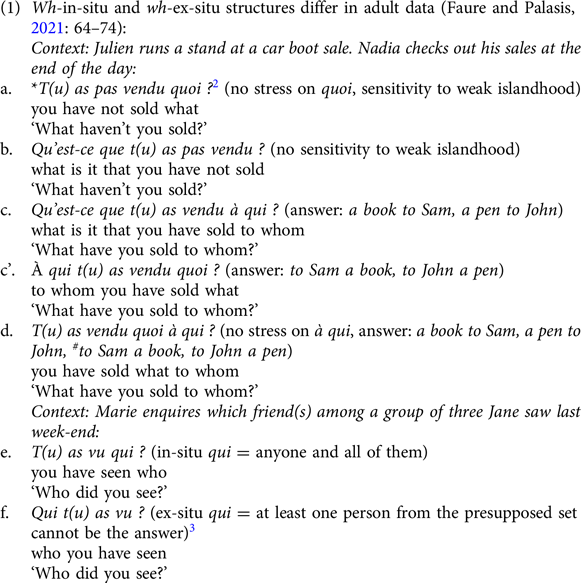

Faure and Palasis (Reference Faure and Palasis2021) also described ‘Colloquial French’ as a wh-in-situ language with covert wh-movement; however, contrary to Baunaz (Reference Baunaz2011), they suggested that covert and overt movement are different. They showed that movement is less restricted in wh-ex-situ questions, which is evidenced by lower sensitivity to weak islands (e.g., negation; see Examples 1a vs. 1b) and Superiority (i.e., order of arguments in multiple questions; see Example 1c, its alternate c’ vs. Example 1d and the answers they allow). The authors thus attributed overt movement of the wh-phrases to the presence of a different trigger, namely Exclusivity. A wh-question endowed with this feature presupposes that not all of the possible answers, say from a set of three, are correct but that two at most are (see Examples 1e vs. 1f).

Baunaz’s (Reference Baunaz2011, Reference Baunaz2016) and Faure and Palasis’ (Reference Faure and Palasis2021) proposals both hinge upon the syntax-semantics interface and account for adult Colloquial French.Footnote 4 This language will be considered here as the target language for children.

1.2 The child system

Research has shown that French preschoolers usually produce more in-situ wh-questions than adults (Zuckerman and Hulk, Reference Zuckerman and Hulk2001; Strik, Reference Strik2007; Strik and Pérez-Leroux, Reference Strik and Pérez-Leroux2011; Becker and Gotowski, Reference Becker and Gotowski2015; Thiberge, Reference Thiberge2020). Young children nevertheless also produce ex-situ wh-items from the onset around the age of 2;0 (Crisma, Reference Crisma1992; Déprez and Pierce, Reference Déprez and Pierce1993; Hamann, Reference Hamann2006; Strik, Reference Strik2007; Prévost, Reference Prévost2009), and the in-situ rates vary widely from one child to another. A small review of children between 1;8 and 2;9 (Palasis, Faure and Lavigne, Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019) reported in-situ rates ranging from 1.3% (Philippe at 2;3 in Crisma, Reference Crisma1992) to 94.4% (Augustin at 2;04 in Rasetti, Reference Rasetti2003) in naturalistic speech, which seems to display more in-situ wh-items than experimental contexts (Zuckerman and Hulk, Reference Zuckerman and Hulk2001). The in-situ ratio also seems to be different with pronouns (e.g., quoi ‘what’) compared to adverbs (e.g., où ‘where’), and there are more in-situ wh-phrases with the former than with the latter (Strik, Reference Strik2007; Jakubowicz, Reference Jakubowicz2011; Strik and Pérez-Leroux, Reference Strik and Pérez-Leroux2011).

The discrepancy between the ratios of in-situ and ex-situ wh-phrases in adult and child speech has often been ascribed to differential abilities between adults and children. Generativists posit that in-situ wh-questions converge by checking a wh-feature covertly in Logical Form, whereas ex-situ wh-questions converge by checking the wh-feature in LF and overt syntax (Bayer and Cheng, Reference Bayer, Cheng, Everaert and Van Riemsdijk2017 for a review). The latter is described as cognitively more costly, and derivational economy is assumed in children compared to adults (Hamann, Reference Hamann2006; Jakubowicz, Reference Jakubowicz2011; Strik, Reference Strik2012). Differing pragmatics have also been evoked in the literature, such as overuse of common ground in children entailing more wh-in-situ questions (Gotowski and Becker, Reference Gotowski and Becker2016). However, hypotheses based on differential abilities make the prediction that all children, whatever their language, should initially produce more in-situ wh-phrases, which is not the case in target wh-ex-situ languages (e.g., English, Dutch, Italian, German, Swedish; Stromswold, Reference Stromswold1995; Van Kampen, Reference Van Kampen1997; Guasti, Reference Guasti, Friedemann and Rizzi2000; Roeper and De Villiers, Reference Roeper, De Villiers, De Villiers and Roeper2011; Strik, Reference Strik2012).

Resorting to another type of difference between adults and children, Palasis et al. (Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019) showed that Verb form (i.e., Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’Footnote 5 vs. Free be forms and Lexical verbs) was a discriminating variable with regard to wh-position, and that there was a correlation between the wh-in-situ position and the Fixed be form in their child data (see Examples 2a vs. 2b and 2c). The difference between adults and children was then ascribed to different stages of the diversification of the verbal system with more c’est forms in children than in adults (following Guillaume, Reference Guillaume1927; Clark, Reference Clark1978; Bassano, Eme and Champaud, Reference Bassano, Eme and Champaud2005). The hypothesis also accounted for the well-documented asymmetry between adults and children with regard to wh-pronouns and wh-adverbs: Children utter more in-situ wh-pronouns than adults (e.g., quoi ‘what’, qui ‘who’), whereas both groups favour the ex-situ position for wh-adverbs (e.g., où ‘where, comment ‘how’; Zuckerman and Hulk, Reference Zuckerman and Hulk2001; Strik, Reference Strik2007; Strik and Pérez-Leroux, Reference Strik and Pérez-Leroux2011; Becker and Gotowski, Reference Becker and Gotowski2015). Palasis et al. (Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019) reported that most pronouns were uttered with the Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’ that favours in-situ (see 2a); whereas most adverbs were uttered with the Free verb forms that favour the ex-situ position (see 2b and 2c).

In this study, we will examine a new dataset for 16 children in their third kindergarten year and connect these new data with the previously examined data for the same children in their first two kindergarten years (Palasis et al., Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019), hence providing a new three-year longitudinal investigation into the wh-questions for 16 children. More specifically, we will examine the distribution of wh-in-situ questions in Year 3 and compare our results with Years 1 and 2 in order to shed light on new developmental aspects of the position of wh-words in preschoolers. Section 2 will describe the entire dataset and the predictions we make building on previous hypotheses. Section 3 will statistically examine the data as a function of the wh-position (in-situ vs. ex-situ), the verb form (fixed vs. free), and the grammatical category of the wh-phrase (pronoun vs. adverb). Section 4 will examine the counter-examples to the correlation between the Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’ and the wh-in-situ position, provide a comparison with the target language described in Section 1.1, and elaborate on deixis. We will end with concluding remarks and future research in Section 5.

2. METHOD

This research will statistically investigate the production of matrix wh-questions in typically developing preschool French L1 children. In Section 2, we will describe the initial kindergarten dataset (2.1), the participants (2.2), the data cleaning process leading to the final dataset (2.3), and the predictions we make building on previous hypotheses (2.4).

2.1 The initial kindergarten dataset

The data were collected with a class of preschoolers during their three kindergarten years in the South of France (total n = 41,845 utterances; see Table 1). Small groups of two to four children were gathered in a quiet room close to their usual classroom and were encouraged by the researcher to narrate their activities in and out of school, ‘read’ books and play games. There were child-child and child-researcher interactions, and the latter were kept as natural as possible. The children were video- and audio-recorded during 20 to 25-minute sessions, 13 times during their first year, and 10 times during their second and third kindergarten years (which amounted to an average interval between two sessions of three to four weeks, except for holidays). The first two years were examined with regard to wh-questions in Palasis et al. (Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019). This article will focus on the wh-in-situ questions in the newly processed data for the third year (5 sessions out of 10 are available for analysis, transcribed and coded with the CHILDES tools; MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2000) and on a new longitudinal analysis of the three years.

Table 1. The kindergarten corpus

2.2 Participants

The participants were the native speakers of Hexagonal French in the kindergarten class described in Section 2.1. All the children in the class were asked to participate (n = 20), but four children were excluded in the final dataset: two children did not have a native French background at home, and two children moved during the period. The set thus comprises the data for 16 children (9 female) during a three-year period (n = 36,063 utterances). Figure 1 shows the distribution of the data according to each child over the three years. The children were between 2;5 (MS: youngest child at the beginning of Year 1) and 5;11 (KE: oldest child by the end of Year 3).

Figure 1. Participation per year per child.

2.3 The final dataset

The children produced six types of questions that distributed in frequent and infrequent types (see Examples 3 and Figure 2). Finite matrix wh-questions (initial n = 1,084) represented one of the frequent types, with an average of 34.5% of the children’s questions during the three-year period.

Figure 2. Distribution of question types.

The longitudinal dataset in Figure 2 shows that the ratio of finite matrix wh-questions decreases during the period in favour of yes/no and non-verbal questions. To the contrary, the ratio of children’s utterances compared to adults’ utterances in the entire dataset increases during the period (Year 1: 50.8%, Year 2: 56.9%, Year 3: 68%). The progression shows that there are more child-child and fewer child-adult interactions in Year 3 than in Year 1. We hypothesize that the decrease in child wh-questions pertains to this change in addressee, children using more non-verbal and yes/no questions than matrix wh-questions when addressing another child than when addressing an adult.

Table 2 shows the initial dataset of 1,084 matrix wh-questions distributed according to wh-word (quoi/que ‘what’, où ‘where’, qui ‘who’, pourquoi ‘why’, comment ‘how’, à qui ‘to whom’, à quoi ‘to what’, quand ‘when’, quel ‘which’, lequel ‘which one’, combien ‘how many’) and according to syntactic structure. The syntactic structures stem from the Verb form hypothesis that suggested that verb form (i.e., Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’ vs. Free be and lexical forms) is a discriminating variable for wh-position in child data (Palasis et al., Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019). Examples (4) illustrate the 11 different structures as a function of the position of the wh-item and the verb form in the dataset. Structures 1a, 1b, 4 and 6 display in-situ wh-questions and Structures 2a, 2b, 3a, 3b, 5, 7 and 8 display ex-situ wh-questions.

Table 2. Distribution of wh-questions according to wh-item and syntactic structure (initial 3-year dataset)

* Structures: 1a: S Vlex wh-, 1b: S Vbe wh-, 2a: wh- S Vlex, 2b: wh- S Vbe, 3a: wh- Vlex S, 3b: wh- Vbe S, 4: c’est wh-, 5: wh- c’est, 6: c’est wh- que S V, 7: wh- c’est que S V, 8: wh-est-ce que S V.

Previous research has put forward that some wh-words, contexts and syntactic structures favour either ex-situ or in-situ wh-questions. In order to investigate the factors that possibly interact with the position of wh-items, we needed to examine only the wh-items, contexts and syntactic structures that allow the alternative in-situ/ex-situ wh-positions. The following items (n = 366; mainly in shaded cells in Table 3) were hence discarded from the initial 1,084 set:

-

The wh-item pourquoi ‘why’ (n = 111) appears only ex-situ. This wh-word is assumed to be generated in the left periphery, higher than the other wh-words (Rizzi, Reference Rizzi, Cinque and Salvi2001; Hamann, Reference Hamann2006; Myers and Pellet, Reference Myers, Pellet, Katz Bourns and Myers2014).

-

The wh-item qui ‘who’ always appears to the left of the finite verb when it is a subject (n = 58).

-

Cleft structures (Structures 6 and 7; n = 116), because we do not address the specific matter of wh-fronting in clefts in this article (but see Oiry, Reference Oiry2011).

-

The D-linked wh-items (mainly quel ‘which’, lequel ‘which one’, and variants thereof; n = 59, 23 quel/lequel + 36 with other wh-words), because of the possible interaction between D-linking and the in-situ position in French (Coveney, Reference Coveney1989; Obenauer, Reference Obenauer1994; Chang, Reference Chang1997; Boeckx, Reference Boeckx2000; Cheng and Rooryck, Reference Cheng and Rooryck2000).

-

Questions with subject-verb inversion (Structures 3a and 3b; n = 11), because they allow ex-situ wh-items only, and these questions belong to Standard French, which we do not examine in this article.

-

Questions with any other characteristic of Standard French as opposed to Colloquial French (i.e., non-elided nominative clitics before consonants and discontinuous negation; Palasis, Reference Palasis2013): only one wh-question was discarded due to full il in front of a consonant (i.e., et il [/] il voit quoi ? ‘and what does he see’).

-

Immediate (self-)repetitions (n = 10).

Table 3. Distribution of wh-questions according to wh-item and syntactic structure (final 3-year dataset)

* Structures: 1a: S Vlex wh-, 1b: S Vbe wh-, 2a: wh- S Vlex, 2b: wh- S Vbe, 3a: wh- Vlex S, 3b: wh- Vbe S, 4: c’est wh-, 5: wh- c’est, 6: c’est wh- que S V, 7: wh- c’est que S V, 8: wh-est-ce que S V.

Table 3 shows the final dataset with 718 wh-questions produced by 16 children during their three kindergarten years. Year 3 (n = 158) is examined for the first time and is added to Year 1 (n = 368) and Year 2 (n = 192) that have been investigated in previous work.

2.4 Predictions

Building on previous hypotheses detailed hereunder, we make the following predictions:

-

i. Because there are no major changes in the grammar of the children between Years 1, 2 and 3 (as established in Section 2.3 with the near absence of markers of Standard French in Year 3), we predict that there should be no significant difference in the distribution of the in-situ versus ex-situ rates between Year 3 and the previously studied Years 1 and 2. We will address this matter in Section 3.1.

-

ii. The Verb form hypothesis (Palasis et al., Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019) makes the prediction that the distribution of in-situ and ex-situ wh-questions in Year 3 of the dataset should be related to Verb form (Fixed vs. Free forms). We will test this prediction in Section 3.2.

-

iii. Child datasets usually report an asymmetry in the position of the wh-items according to age (children vs. adults) and to grammatical category of the wh-item (pronouns vs. adverbs; Zuckerman and Hulk, Reference Zuckerman and Hulk2001; Strik, Reference Strik2007; Jakubowicz, Reference Jakubowicz2011; Becker and Gotowski, Reference Becker and Gotowski2015). Two hypotheses exist on this asymmetry in child questions: a relationship between the position of objects in the verbal phrase and the in-situ position of the corresponding wh-pronouns, and a relationship between the verb form in the sentence and the position of the wh-word whatever its grammatical category (Strik, Reference Strik2007 and Palasis et al., Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019, respectively). The first hypothesis makes the prediction of a clear-cut asymmetry according to grammatical category (i.e., in-situ pronouns vs. ex-situ adverbs); the second hypothesis predicts that wh-pronouns and wh-adverbs can appear in-situ or ex-situ depending on the verb form. We will test both predictions in Section 3.3 and ponder their respective developmental scopes.

3. RESULTS AND PRELIMINARY DISCUSSION

The final dataset in Table 3 (n = 718 wh-questions) was submitted to the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel Test (henceforth CMH; Cochran, Reference Cochran1954; Mantel and Haenszel, Reference Mantel and Haenszel1959) for repeated 2x2 tests of independence. We investigated the relationship between the verb form (Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’ vs. Free be forms vs. Lexical forms) and the position of the wh-item (In-situ vs. Ex-situ) in each utterance. This was done by specifically programming an Excel spreadsheet. The data were submitted in as many 2x2 tables as there were participants with available data for each test in order to account for the quantitative and qualitative differences between participants (McDonald, Reference McDonald2011; see Figure 1 for the distribution per child). A significant result at the X2 CMH test means that the variables are dependent (one has an effect on the other). In the following subsections, we will test the predictions stated in Section 2.4 on the evolution of wh-in-situ compared to wh-ex-situ (3.1), on the impact of the different verb forms (3.2), and on the asymmetry between wh-pronouns and wh-adverbs (3.3).

3.1 Distribution of the wh-questions according to the position of the wh-item (in-situ vs. ex-situ)

We examined the distribution of the wh-questions in Year 3 and longitudinally from Year 1 to Year 3 in order to describe the overall progression of the in-situ position in the dataset. The filtering of the data (described in Section 2.3) pointed towards an absence of radical change between Years 1 and 2 taken together and Year 3 in terms of grammatical characteristics (i.e., nominative clitics and negation). We therefore predicted no significant difference of distribution between both wh-positions in Year 3 compared to the first two years.

Figure 3 shows that wh-in-situ questions remain prevalent in Year 3 (55.7%), as they were in Year 1 and Year 2 (67.4% and 59.4%). A repeated-measures ANOVA including Year (1, 2, 3) and Position (ex-situ, in-situ) as factors confirmed that there are overall significantly more in-situ questions than ex-situ ones (F(1,15) = 26.649; p < .001; eta squared = .640) and no significant differences in the distribution between the three years (F(2,30) = 1; n.s.). Prediction (i) is thus borne out. Nevertheless, Figure 3 also shows a steady progression in the wh-ex-situ position during the period. Specific post-hoc comparisons using Bonferroni corrections showed that there are more in-situ questions than ex-situ ones in Year 1 (t(15) = −4.418, p < .01), while their proportions become equivalent in Years 2 and 3 (respectively: t(15) = −1.575, n.s.; t(15) = −1.826, n.s.).

Figure 3. Longitudinal distribution of matrix wh-questions according to the position of the wh-item.

We also considered the wh-words individually in order to uncover possible specific developmental patterns.Footnote 6 There were no significant differences in the in-situ/ex-situ distributions between the three years, except for the wh-word quoi/que ‘what’ that showed a significant decrease in the in-situ position between Year 2 and Year 3 (73.5%–59.0%; Fisher’s Exact Test for Count Data: p < .05). In Section 3.2, we will investigate the detail of the in-situ/ex-situ distribution according to the verb form, and we will elaborate on the significant decrease in the in-situ quoi ‘what’ at the end of Section 3.3.

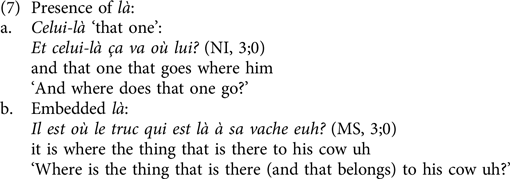

3.2 Distribution of the wh-questions according to the verb form (Fixed be form vs. Free be forms vs. Lexical verbs)

We examined the distribution of the wh-questions according to the verb form (Fixed be form vs. Free be forms vs. Lexical verbs) in Year 3 (Table 6) and longitudinally with Years 1 and 2 (Tables 4 and 5). We repeated the series of analyses carried out on the first two years on the third year: All be forms vs. Lexical verbs, Free be forms vs. Fixed be form, Free be forms vs. Lexical verbs, Fixed be form vs. Lexical verbs, and Fixed be form vs. All Free forms (Free be and Lexical).

Table 4. Distribution of wh-questions according to verb form and wh-position (Year 1)

Table 5. Distribution of wh-questions according to verb form and wh-position (Year 2)

Table 6. Distribution of wh-questions according to verb form and wh-position (Year 3)

The initial analyses of the first two years opposing All be forms to Lexical verbs (following the binary Lexical hypothesis on adult data; Coveney, Reference Coveney1995) had shown that the position of the wh-word in child data was also related to the type of verb, linking the in-situ position with be forms (without distinguishing Free be forms and Fixed be form) and the ex-situ position with Lexical verbs (Palasis et al., Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019: 225). In order to test if this is still the case in Year 3, we performed, as it had been done in Years 1 and 2, a CMH Test for repeated 2x2 tests of independence. The analysis of the independence between wh-position and verb type –that is Lexical Verbs vs. All be forms (free and fixed) – gave a X2 CMH = 31.28, 1 df, p < .0001. Again, in the third year, the in-situ wh-position is significantly more frequent with be forms and the ex-situ wh-position is significantly more frequent with Lexical Verbs. Cramér’s V, which determines the degree of association between variables, indicates a large effect size (V = 0.44; Cramér, Reference Cramér1946).

To refine this result in Year 3, we further tested the impact of each be form on the position of the wh-word separately. Since one child (NI) had no data for this test, data were submitted in only 15 2x2 tables. Analyzing the relationship between the wh-position and the Free be forms vs. the Fixed be form using CMH, the result was X2 CMH = 12.97, 1 df, p < .001. This showed that, as it was the case in the first two years, the wh-position is significantly more likely to occur in-situ with the Fixed be form and ex-situ with the Free be forms. Cramér’s V indicates a large effect size (V = 0.533). This result allows us to separate the be forms into two significantly different categories, hence distinguishing Free be forms and the Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’, as previously observed in Years 1 and 2.

Bearing in mind that Lexical verbs are also free verb forms, we then examined Lexical Verbs in relation to Free be forms. The result was not significant (X2 CMH = 0.135, 1 df, p = .7). This result shows that, as in the first two years, the wh-position is not significantly different when comparing Free be forms and Lexical Verbs, which are also free forms. Therefore, we confirm that the type of free verb (Lexical vs. be) is not a discriminating variable for the position of the wh-words in neither year of the dataset.

To test if the form of the verb correlates with the position of the wh-word, we looked at the impact of the Fixed be form on the position of the wh-word and compared the Fixed be form with Lexical Verbs. The result was significant (X2 CMH = 42.74, 1 df, p < .0001). As in the first two years, the wh-position is significantly more in-situ with the Fixed be form and more ex-situ with Lexical verbs. Cramér’s V indicates a large effect size (V = 0.649).

Finally, to confirm the importance of the Verb form (Fixed vs. Free) as a discriminating variable with respect to wh-position, we looked at the impact of the Fixed be form on the position of the wh-words by testing the Fixed be form against All Free forms, regardless of verb type. The result was significant (X2 CMH = 46.516, 1 df, p < .0001) as it was for the first two years. The wh-position is significantly more in-situ with the Fixed be form and more ex-situ with All Free forms (Free be forms and Lexical verbs). Cramér’s V indicates a large effect size (V= 0.598).

Altogether, this pattern of results is in line with what was observed for the first two years. In the third year too, the Verb form (Fixed vs. Free) is a discriminating variable for the wh-position, regardless of Verb type (All be vs. Lexical verbs), and the effect size is larger when investigating Verb form (Fixed vs. Free: V = 0.598) compared to Verb type (All be vs. Lexical verbs: V = 0.44). Finally, the different effect sizes between the three categories (Fixed be vs. Free be: V = 0.533 and Fixed be vs. Lexical: V = 0.649) illustrate the greater syntactic and semantic differences between Lexical verbs and the Fixed be form, which differ with regard to two features (i.e., lexicality and fixity), than between Fixed and Free be forms, which differ in one feature only (i.e., fixity).

The tests undertaken in Section 3.2 on Year 3 of the dataset allow us to confirm the Verb form hypothesis: the in-situ position of the wh-phrases is related to the Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’ against all Free forms. Prediction (ii) is thus borne out. Though significant, this link does not hold for the entire dataset. We will elaborate on the interface between syntax (the position of the wh-phrase) and semantics (the question type) in Section 4, when we discuss the outliers to the in-situ/Fixed be correlation (i.e., the wh-in-situ questions with Free verb forms).

3.3 Distribution of the wh-questions according to the grammatical category of the wh-word (pronouns vs. adverbs)

In Section 2.4 (Prediction iii), we reported that children usually utter more in-situ wh-pronouns than adults, whereas both groups favour the ex-situ position for wh-adverbs (Zuckerman and Hulk, Reference Zuckerman and Hulk2001; Strik, Reference Strik2007; Strik and Pérez-Leroux, Reference Strik and Pérez-Leroux2011; Becker and Gotowski, Reference Becker and Gotowski2015). We mentioned two hypotheses on the prevalence of in-situ wh-pronouns in children compared to adults. Strik (Reference Strik2007) suggested an effect of the embedded position of arguments in the verbal phrase compared to adjuncts that are merged higher in the structure. The VP internal position then renders pronouns more costly to move than adverbs. Palasis et al. (Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019) reported a possible effect of the verb form on the position of the wh-phrase whatever the grammatical category of the wh-word. The ratio of the wh-in-situ phrases (pronominal and adverbial) is then expected to follow the ratio of the Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’, because the latter favours wh-in-situ questions. The first hypothesis makes the prediction that the ratio of wh-in-situ pronouns should decrease in favour of more wh-ex-situ pronouns as a function of the children’s cognitive development. The hypothesis does not make any particular predictions on the evolution of the position of wh-adverbs. The second hypothesis makes the prediction that the ratio of wh-in-situ altogether (pronouns and adverbs) should decrease if the Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’ decreases, because verb form and wh-position are related. Conversely, wh-words co-occurring with Free verb forms are expected to be ex-situ. The developmental aspect of this hypothesis hinges upon the diversification of the verbal system with more c’est forms in children than in adults (Guillaume, Reference Guillaume1927; Clark, Reference Clark1978; Bassano et al., Reference Bassano, Eme and Champaud2005).

We examined the evolution of the in-situ/ex-situ ratios for wh-pronouns and wh-adverbs separately, and the evolution of the ratio of fixed and free verb forms during the three-year period. A repeated-measures ANOVA including Year (1, 2, 3) and Grammatical category (Pronouns, Adverbs) as factors indicates an effect of the grammatical category of the wh-item (F(1,15) = 50.143; p < .001; eta squared = .770), and that the distribution between the three years is not significantly different (F(2,30) = 1.513; n.s.).

Figure 4 shows the difference between wh-in-situ pronouns and adverbs. The ratio of wh-in-situ pronouns decreases constantly (82.9%–78.0%–61.9%) in favour of more ex-situ pronouns, as expected considering that adult Colloquial French is usually described as displaying more ex-situ wh-questions than child French. The decrease could then well stem from the cognitive development suggested in Strik (Reference Strik2007). An intriguing fact then is the evolution of the ratio of in-situ wh-adverbs. They first decrease and then increase during the period (36.1%–29.7%–40.0%). Since the last year is not significantly different from the first year, there does not seem to be a developmental/cognitive constraint underpinning the ratio of in-situ/ex-situ wh-adverbs. We also note that despite the decrease in wh-in-situ pronouns in Figure 4, the observed decline is not significant either.

Figure 4. Evolution of ratios for wh-in-situ pronouns/adverbs and Fixed be/free verb forms.

We then compared the evolution of the wh-positions – pronouns and adverbs – with the evolution of the verb forms – Fixed be and Free forms. It seems that the decrease in wh-in-situ pronouns parallels the decrease in Fixed be form, and that the decrease-increase in in-situ wh-adverbs mirrors the Free verb forms pattern, which means that the ex-situ wh-adverb pattern parallels it. The evolution of the in-situ/ex-situ ratios in pronoun and adverb wh-positions could then all be accounted for within the Verb form hypothesis that opposes the Fixed be form to All Free forms (Section 3.2).

In order to test the parallels observed in Figure 4, we examined the position of the adverb and pronoun wh-words as a function of the Verb form (Fixed be form vs. Free be forms vs. Lexical verbs). Table 7 shows that adverb wh-words (n = 45; où ‘where’, comment ‘how’, quand ‘when’, combien ‘how many’) massively co-occur with Free verb forms in the third year (95.6%; Structures 1a, 1b, 2a and 2b), similarly to the first two years (99.6%; same structures in Palasis et al., Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019). In the third year, two adverbs only appear with the Fixed be form (c’est comment ? ‘how is it’ VI, 5;2 and c’est quand ? ‘when is it’ CA, 5;3). The Verb form hypothesis predicts that we should not find a significant difference in the position of the wh-word when comparing Structures 1b and 2b (Free be forms) with Structures 1a and 2a (Lexical verbs), since the latter are also free verb forms.

Table 7. Distribution of wh-adverbs according to syntactic structure (Year 3)

We repeated the series of analyses carried out on the first two years on the third year. We examined the independence between the wh-position and the verb form with wh-adverbs. Only 11 children had sufficient data for this test (n = 41). The CMH test was carried on Lexical verbs vs. Free be forms, which represent 95.6% of the wh-adverb questions in Year 3. As expected, the result is not significant (X2 CMH = 0.52, 1 df, p = .471). This result confirms that, as in the first two years and as in Section 2.3 for the third year, the wh-position is not significantly different when comparing Free be forms and Lexical verbs (also free forms) in this subgroup of adverbial wh-words. We conclude that adverbs are mainly ex-situ throughout the period (Year 1: 63.9% and Year 2: 70.3% in Palasis et al. Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019; Year 3: 60.0% in Table 7), because they massively and steadily co-occur with Free verb forms (Free be forms and Lexical verbs) in all three years.

Table 8 shows that wh-pronouns co-occur with Free and Fixed verb forms (53.1% and 46.9%, respectively), but that nearly half the pronouns (45.1%) appear in one configuration: in-situ with the Fixed be form (Structure 4). The rest of the pronouns mainly co-occur with Lexical verbs, either ex-situ with the est-ce que interrogative marker (Structure 8: 36.3%) or in-situ (Structure 1a: 16.8%). The wh-pronoun quoi/que ‘what’ is overwhelming (n = 105), and there are a few qui ‘who’ (n = 5), à quoi ‘to what’ (n = 2), and à qui ‘to whom’ (n = 1). Since wh-pronouns never appear with Free be forms, we examined the relationship between the position of the wh-pronouns with the Fixed be form as opposed to Lexical verbs only. The CMH test was performed on the data in 15 children (n = 112) and showed a significant result (X2 CMH = 27.598, 1 df, p < .00001). This result confirms that the wh-items are more in-situ with the Fixed be form than with Lexical verbs in this subgroup of pronominal wh-words.

Table 8. Distribution of wh-pronouns according to syntactic structure (Year 3)

Taken together, these results seem to show that the grammatical category (adverb vs. pronoun) is not a discriminating variable for the position of the wh-phrase. We suggest that the in-situ/ex-situ ratios of wh-pronouns and wh-adverbs and the well-documented discrepancy with adult data pertain to the ongoing development of the verbal system of the children, who gradually flesh their system out by replacing c’est forms with lexical verbs.

In addition to this gradual verb diversification, the new data examined in this contribution draw our attention to a second developmental phenomenon. Indeed, we saw in Section 3.1 that there were no significant differences in the in-situ/ex-situ distributions between the three years, except for the wh-word quoi/que ‘what’ that showed a significant decrease in the in-situ position between Year 2 and Year 3 (from 73.5% to 59.0%; Fisher’s Exact Test for Count Data: p < .05). Interestingly, the ‘what’ pronoun in French is the only wh-word with different morphological forms according to the position (i.e., in-situ quoi vs. ex-situ que). Moreover, the form of the pronoun varies between Colloquial French, which displays qu’est-ce que ‘what is it that’ without subject inversion in the question (e.g., qu’est-ce qu’il a dit ? ‘what did he say’), and Standard French, which displays que ‘what’ with subject inversion (e.g., qu’a-t-il dit ?). The data thus illustrate that the children are fleshing out their wh-word inventory by gradually integrating the alternation between in-situ quoi and ex-situ qu’est-ce que ‘what is it that’, which results in the latter being more frequent over time. This development together with the verb diversification seem to account nicely for the decrease in the overall wh-in-situ ratio (Figure 3), the decrease in the pronoun wh-in-situ ratio (Figure 4), and the absence of decrease in the adverb wh-in-situ category (Figure 4).

4. OUTLIERS TO THE CORRELATION BETWEEN FIXED BE FORM AND WH-IN-SITU AND DEICTIC HYPOTHESIS

Finally, we listed the outliers to the correlation between the Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’ and the wh-in-situ position, that is the questions that display Free verb forms and wh-in-situ (Structures 1a and 1b) and the Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’ with the wh-ex-situ position (Structure 5). The total number of outliers amounted to 182 (25.3% of the total dataset, see Table 9).

Table 9. Outliers in the dataset according to wh-word and syntactic structure

In this section, we will examine the wh-in-situ questions only (Structures 1a and 1b, n = 164, 22.8% of the total dataset) in order to seek variables that could account for the unexpected wh-in-situ position in these structures. We explore two hypotheses:

-

a. Outliers share with the Fixed be structure (Structure 4) a feature that triggers the usage of a wh-in-situ instead of a wh-ex-situ.

-

b. Outliers exhibit types of wh-in-situ that are different from those found in the Fixed be questions.

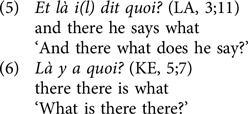

Taking a closer look at the corpus, we observed that it is replete with in-situ questions such as (5) and (6).

Note the presence of the adverb là ‘there’ in both cases. A survey of our corpus showed that là is surprisingly frequent among the outliers. We examined the presence of là in detail. Items like celui-là ‘that one’ or ce chat-là ‘that cat’ were excluded, since là is part of the discontinuous demonstrative morpheme ce…là and is hence not the adverb là (see 7a). Similarly, là-dedans ‘there inside’ and embedded versions like (7b) were not included.Footnote 7

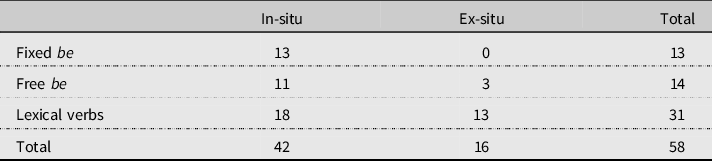

Based on the occurrences in Table 10, we ran a Fisher’s Exact Test of independence. The result is significant (p < .01), which shows that the distribution of wh-in-situ and wh-ex-situ with respect to the presence of là is above chance and that there is a correlation between the presence of là and the presence of wh-in-situ.

Table 10. Distribution of là in wh-questions

Là is a complex marker in French. Although it is originally a locative adverb meaning ‘here’ or ‘there’, it developed a range of other deictic uses, including temporal, narrative, discursive and interactional ones. In its temporal and narrative uses, it serves as a linker between two parts of a story. This use is not featured in our questions. As a discursive and interactional marker, là is used by the speaker to draw the addressee’s attention to her/his discourse and her/his utterance. According to Smith (Reference Smith1995), là is the least specified of the French locative adverbs (in contrast with ici ‘here’ and là-bas ‘over there’). It is characterized by the features [-far], [-speaker], which account for its local as well as its discourse usages (by default, it serves to involve the addressee). In contrast, Kleiber (Reference Kleiber1995: 23) suggests that là refers to something that is given, manifest or accessible. When it refers to a location, spatial referentiality is already active in the context. Note however that the two approaches are not incompatible. To draw the attention of the addressee to an object, this object must be salient or at least already accessible.

Be that as it may, the main questions are to discover what in là favours wh-in-situ, and if là and Fixed be structures have anything in common. To discuss the matter, it is useful to go back to what was introduced in Section 1. Recall that the target (adult) language is complex with respect to the wh-in-situ phenomenon, since it features three types of wh-questions (Baunaz, Reference Baunaz2011, Reference Baunaz2016). Type 1 is a neutral information-seeking question, without presupposition. Type 2 is presuppositional-partitive (with rise-fall intonation on the wh-phrase). Type 3 is presuppositional-specific (the wh-phrase forms its own prosodic phrase; Vergnaud and Zubizarreta, Reference Vergnaud, Zubizarreta, Koster, Van der Hulst and Van Riemsdijk2005).Footnote 8 In adult speech, Faure and Palasis (Reference Faure and Palasis2021) showed that wh-ex-situ is favoured by the presence of a contrastive feature whose specific semantics is exclusive, meaning that the question conveys the presupposition that at least one of the contextually available answers is a priori excluded.

Let us now compare our findings on child speech with this target situation. In Sections 1 and 3, we mentioned and confirmed one factor favouring wh-in-situ in child French: the presence of the Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’. Palasis et al. (Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019: 230) additionally suggested that the use of wh-ex-situ was favoured when the children’s questions displayed a verb form with more semantic content (i.e., Free be forms and Lexical verbs). In the target adult language, more semantic content creates more context, in which a presupposed set can be identified. Such a situation is unlikely in a sentence with c’est qui/quoi, because it asks for identification or definition, and most of the time any answer is possible. Once again comparing with adult speech, this category of wh-in-situ sentences corresponds to Type 1 in Baunaz’s (Reference Baunaz2011, Reference Baunaz2016) classification.

What c’est and là share is that they display a deictic element (c’ and là) linked to the hic et nunc. They pick out of the immediate context an element or a situation that was not yet in the scope of the attention of the addressee and thus initiate the identificational or definitional process that underpins the interrogative speech act. So, no relation is established with the previous context or a presupposed set, a necessary condition to have Types 2 or 3 wh-in-situ or est-ce que-less wh-ex-situ (at this stage, children do not produce wh-est-ce que, apart from qu’est-ce que ‘what is it that’, as mentioned in Section 3.3).

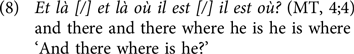

Other data go in the same direction. In (8), the child begins the utterance with là and goes on with a wh-ex-situ question, but hesitates, stops and corrects the sentence to finally produce a wh-in-situ question, as expected under our analysis.

Consequently, this new dataset prominently features Type 1 wh-in-situ. Semantically, it does not carry a presupposition; syntactically, it does not feature fronting/movement of the wh-phrase. Although it is mostly materialised with c’est and là questions, unmarked Type 1 questions also occur in other guises, such as (9).

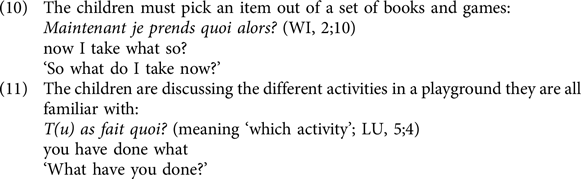

Type 1 is most likely to appear first in child speech, since it is the least marked question type in the target language. Nevertheless, the prevalence of Type 1 is not sufficient to explain all the data, and the examples in (10) and (11) do not abide by the description of Type 1 but belong to Type 2 (so far, we have found no examples of Type 3). In each case, a presupposed set is given from which the answer must be picked out.

Another interesting fact is that, while the proportion of wh-in-situ decreases from Year 1 to Year 3 (Figure 3), the proportion of outliers increases, particularly with lexical verbs (Table 11).

Table 11. Distribution of outliers among wh-in-situ (%)

Summarizing our findings in this section, we found that wh-in-situ structures come in two types in child speech, corresponding to Type 1 and Type 2 questions in Baunaz’s (Reference Baunaz2011, Reference Baunaz2016) description of French adult speech. Type 1 is prevalent. It is a type of mere information-seeking questions, which take the form of Fixed be and là structures in child speech. In fact, these deictic structures are the most suitable to encode the operation of identification that underlies the interrogative process. Nevertheless, Type 2 (partitive questions) is also present. It may be tied to the other observation that we made, namely that the number of outliers with lexical verbs increases through time. A possibility is that children gradually develop more complex types of wh-in-situ, such as Type 2, which leads to a growing usage of this type and to the increase of the number of alleged outliers. This hypothesis is consistent with the fact that children gradually use structures with more material, a factor favouring the linking to the context and the construction of presupposed sets. We leave the exploration of this hypothesis for future research.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This article examined the production of matrix information-seeking wh-questions in 16 typically developing French children during their three kindergarten years (n = 718, Table 3). We aimed to explain the prevalence of the in-situ wh-position in child data compared to adult data and to disentangle the various factors that could explain the in-situ/ex-situ ratio and its evolution during the three-year period.

In Section 3.1, we observed that wh-in-situ questions remain prevalent during the period despite a steady increase in wh-ex-situ (Figure 3). There are no significant differences in the in-situ/ex-situ distributions between the three years. We further noticed that there are no significant differences in the in-situ/ex-situ distributions of each wh-item considered separately between the three years, except for the wh-word quoi/que ‘what’ that shows a significant decrease in the in-situ position between Year 2 and Year 3.

In Section 3.2, we statistically examined the position of the wh-phrases as a function of the Verb form in Year 3 (Fixed be forms vs. Free be forms vs. Lexical verbs, which are also free forms, following Palasis et al., Reference Palasis, Faure and Lavigne2019 in Year 1 and 2). The Verb form (Fixed vs. Free) is also a discriminating variable for the wh-position in Year 3: The Fixed be form favours the in-situ position (e.g., c’est qui Taz ? ‘who is Taz’), whereas the Free forms favour the ex-situ position (e.g., combien ça coûte ? ‘how much does it cost’). Taken together, these results allow us to make the prediction that the ex-situ rate will steadily increase as a function of the diversification of the child verbal system. We leave this matter for future research.

In Section 3.3, we investigated the well-documented asymmetry between in-situ wh-pronouns and ex-situ wh-adverbs. We confirmed that the asymmetry also pertains to the Verb form. Wh-pronouns are more in-situ with the Fixed be form c’est ‘it is’ than with the Lexical verbs. Wh-adverbs are mainly ex-situ, because they massively co-occur with Free verb forms. In line with the prediction on the diversification of the child verbal system, we expect that wh-pronouns will be more ex-situ, when children produce fewer Fixed be forms and more Lexical verbs. Furthermore, the evolution of the data between Year 2 and Year 3 illustrates that the children are fleshing out their wh-word inventory by gradually integrating the alternation between in-situ quoi and ex-situ qu’est-ce que ‘what is it that’. This development together with the verb diversification seem to account for the decrease in the overall wh-in-situ ratio (Figure 3), the decrease in the pronoun wh-in-situ ratio and the absence of decrease in the adverb wh-in-situ category (Figure 4).

Finally, we investigated the outliers to the Verb form hypothesis (i.e., the wh-in-situ questions with Free verb forms; 22.8% of the dataset) in Section 4. We observed the presence of the adverb là ‘there’ in the outliers and elaborated on the fact that là and the Fixed form c’est share deictic properties. Generalising, Fixed be, là and other (unmarked) questions all belong to Baunaz’s (Reference Baunaz2011, Reference Baunaz2016) Type 1 questions in the target adult language (i.e., mere information-seeking questions). We also observed that, while wh-in-situ questions tend to decrease throughout the three years, wh-in-situ outliers increase, which we tentatively attributed to the emergence of Type 2 (and maybe Type 3) wh-questions, which rest on a set of presupposed possible answers. This hypothesis is left for future research.

Another important field that requires future attention is the behaviour of ex-situ wh-questions in child speech. The verb diversification and the increase in the wh-pronoun qu’est-ce que ‘what’ pertain to this domain of investigation. Some Fixed be and là structures that unexpectedly exhibited ex-situ wh-items, though rarely (n = 20, 2% of the corpus), also require attention. More generally, the behaviour of D-linking and wh-ex-situ in child speech largely remains to be explored in future research.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their very constructive comments on previous versions of this contribution. We also thank the audience at the Workshop ‘L’interrogative in situ : aspects formels, pragmatiques et variationnels’ organised by Caterina Bonan, Laurie Dekhissi and Alexander Guryev in June 2022.