1. INTRODUCTION

The French language established itself during the sixteenth century with the help of writers (e.g. Joachim du Bellay, Deffense et Illustration de la langue francoyse, 1549) and royal edicts (e.g. Edit de Villers-Cotterêts, 1539). As it became a political instrument in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, French underwent a process of codification and standardization with prescriptive grammars and dictionaries as well as the creation of the Académie française in 1635. Standard French has maintained its prestige, and “proper usage” is highly valued by its speakers (Lodge, Reference Lodge1993; Battye, Hintze and Rowlett, Reference Battye, Hintze and Rowlett2000). However, even a strongly codified language such as French cannot escape some indeterminacy or idiosyncrasies as with agreement phenomena.

Agreement (or concord) in written French concerns the formal features of gender and number as lexical properties of nouns and determiners, respectively. Nouns are either masculine or feminine although grammatical homonyms such as livre ‘book-msc’/‘pound-fem’ are both (L’Huillier, Reference L’Huillier1999; Price, Reference Price2008). Most nouns have a singular form and mark the plural with -s or -x (Wagner and Pichon, Reference Wagner and Pichon1991),Footnote 1 while gender is morphologically expressed with various suffixes such as -e, -elle, aie, -aine for feminine or -eau, -on, -isme for masculine (Surridge, Reference Surridge1986). The gender and number features have morphosyntactic consequences for adjectives, past participles, determiners and pronouns due to syntactic rules governing structures such as a determiner phrase containing a noun, determiner and adjective (e.g. la-fem-sg belle-fem-sg pomme-fem-sg verte-fem-sg ‘the beautiful green apple’) as well as verbal phrases (e.g. voilà les-fem-pl fleurs-fem-pl que j’ai cueillies-fem-pl ‘here are the flowers I picked’).

French children are aware of inflectional morphology before they start receiving formal literacy instruction (e.g. Nagy, Carlisle and Goodwin, Reference Nagy, Carlisle and Goodwin2013). They seem to discover plural markers when they learn to read (Jaffré and Fayol, Reference Jaffré, Fayol, Joshi and Aaron2005) and are sensitive to verbal inflectional errors (Carrasco-Ortiz and Frenck-Mestre, Reference Carrasco-Ortiz and Frenck-Mestre2014). However, it is well documented that 11–12-year-old children still experience difficulties with encoding the appropriate morphosyntactic information in their written production such as number agreement, maybe because although it is semantically motivated, it is often neutralized in speech (e.g. Manesse and Cogis, Reference Manesse and Cogis2007; Totereau, Brissaud, Reilhac and Bosse, Reference Totereau, Brissaud, Reilhac and Bosse2013).

Empirical data show that grammatical gender knowledge emerges early on as well (Höhle, Weissenborn, Kiefer, Schulz and Schmitz, Reference Höhle, Weissenborn, Kiefer, Schulz and Schmitz2004; Shi and Melançon, Reference Shi and Melançon2010), while knowledge of gender categorization and agreement is robust in 30-month-old toddlers (Cyr and Shi, Reference Cyr and Shi2013), but French gender agreement is rarely investigated (Boloh and Ibernon, Reference Boloh and Ibernon2010). It appears that 18-month-old toddlers are sensitive to grammatical gender cues in nominal phrases with an incongruent gender article as in le-*mas poussette-fem ‘the stroller’ (van Heugten and Christophe, Reference van Heugten and Christophe2015) and master gender agreement on the determiner first, while agreement on the adjective can take longer with frequent errors as late as age 5 (Roulet-Amiot and Jakubowicz, Reference Roulet-Amiot and Jakubowicz2006; Royle and Valois, Reference Royle and Valois2010). The most common written gender marker of the feminine, -e, is not yet acquired by the end of primary school (Cogis and Brissaud, Reference Cogis and Brissaud2019) or middle school (Brissaud, Reference Brissaud2015), and 50% of sixth to ninth graders continue to omit it on adjectives in written production (Bosse, Brissaud and Le Levier, Reference Bosse, Brissaud and Le Levier2020).

Regarding number agreement, Nazzi, Barrière, Goyet, Kresh and Legendre (Reference Nazzi, Barrière, Goyet, Kresh and Legendre2011) have established that French babies as young as 18-months are sensitive to grammaticality contrasts for both singular and plural determiners and non-adjacent verbal forms. However, even highly educated adults may produce written subject-verb agreement errors as in le chien-sg des voisins- pl *arrivent- pl -arrive sg ‘the neighbors’ dog arrives’ (Fayol and Got, Reference Fayol and Got1991; Fayol, Largy and Lemaire, Reference Fayol, Largy and Lemaire1994). This is a well known attraction error whereby verb agreement is realized with the closest noun instead of the subject of the verb (e.g. Bock and Eberhard, Reference Bock and Eberhard1993; Bock and Miller, Reference Bock and Miller1991; Franck, Vigliocco and Nicol, Reference Franck, Vigliocco and Nicol2002; Vigliocco, Butterworth and Garrett, Reference Vigliocco, Butterworth and Garrett1996). In addition, children’s oral production include number inflection on nouns before they do so on verbs (e.g. Bassano, Reference Bassano, Kail and Fayol2000), while their written production show fewer gender and number markings on adjectives than on nouns (Fayol, Totereau and Barrouillet, Reference Fayol, Totereau and Barrouillet2006).Footnote 2

In summary, early sensitivity and acquisition of number and gender do not preclude persistent difficulties for cases of straightforward agreement within a nominal or verbal phrase. This begs the question of how adult FSs would react to cases of variable or incongruent agreement, referred to as idiosyncrasies for short. To the best of my knowledge, this has not yet been tested empirically, so we do not know whether idiosyncrasies in the standard, prescriptive grammar of French would translate into indeterminacy in the mental grammar of FSs, that is their competence in a generative sense, as measured by their performance in two written tasks, a grammaticality judgment task (GJT) and a preference grammaticality judgment task (PGJT).

However, given that a growing number of experimental studies are showing that “native-speaker convergence is a myth: there are, in fact, considerable individual differences in adult L1 speakers (for recent reviews, see Dąbrowska, Reference Dąbrowska2012, Reference Dąbrowska, Dąbrowska and Divjak2015; Farmer, Misyak and Christiansen, Reference Farmer, Misyak, Christiansen, Spivey, McRae and Joannisse2012; Hulstijn, Reference Hulstijn2015)” (Dąbrowska, Reference Dąbrowska2019: 73), we may find similar divergences among our participants as they perform two written elicitation tasks, a grammaticality judgment /correction task and a preference/grammaticality judgment task.

For instance, in Mulder and Hulstijn (Reference Mulder and Hulstijn2011), Dutch L1 speakers (n = 98) split by age groups (18–35, n = 42; 36–50, n = 20; 51–76, n = 36) were asked to perform seven lexical tasks and four speaking tasks in order to assess whether their fluency, knowledge and memory varied with their age and education level. Older participants were slower to respond in the lexical tasks, performed more poorly in the two word span tasks, but better in the vocabulary knowledge task. The speaking tasks did not reveal differences between age groups. The authors report the unexpected finding that most participants produced clear violations of nominal gender and subject-verb number agreement in the speaking tasks, regardless of their education level. Dąbrowska (Reference Dąbrowska2019) compared the performance of L1 and adult L2 learners on grammatical comprehension, vocabulary and collocations. Although L1 speakers outperformed L2 learners as expected, large individual differences and overlap were found between the two groups. Earlier studies had already shown that L1 speakers’ intuitions concerning the grammaticality of certain sentences (e.g. Chipere, Reference Chipere2001) and their comprehension of sentences (e.g. Dąbrowska, Reference Dąbrowska1997) vary depending on their education level.

The next section will provide a descriptive account of idiosyncrasies in agreement from a prescriptive, standard perspective (e.g. Battye et al., Reference Battye, Hintze and Rowlett2000), then the methods used to test how L1 French speakers may perform on elicitation tasks with written stimuli exemplifying these idiosyncrasies as well as reflexive and causative verbs. Will they perform as a homogenous group at the 90% accuracy expected of L1 speakers (e.g. Dronjic and Helms-Park, Reference Dronjic and Helms-Park2014) with their performance aligning with prescriptive grammar, or will they diverge from it and show individual differences?

2. IDIOSYNCRASIES IN GENDER AGREEMENT

2.1. Nominal affective constructions

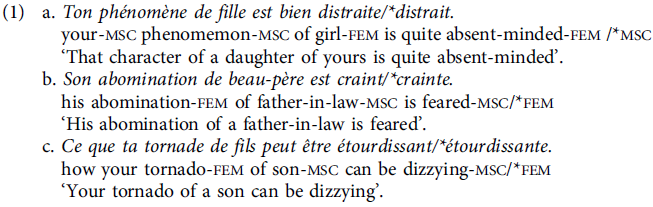

Romance languages such as French, Spanish and Italian exhibit qualitative nominals – also referred to as affective constructions – in a N1 de N2 structure with conflictual agreement (e.g. Casillas Martínez, Reference Casillas Martínez2003; Masini, Reference Masini2016) as exemplified in (1a) (Hulk and Tellier, Reference Hulk, Tellier, Authier, Bullock and Reed1998: 183) and (1b, c) (Hulk and Tellier, Reference Hulk and Tellier2000: 55) for French.

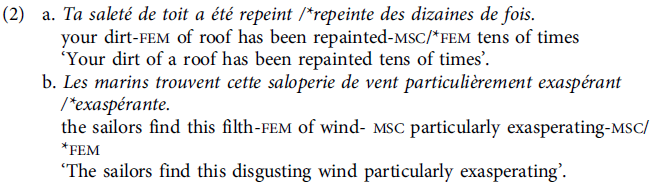

According to Hulk and Tellier (Reference Hulk, Tellier, Authier, Bullock and Reed1998, Reference Hulk and Tellier2000), when N1 and N2 differ in gender, the adjective agrees with the animate N2 assumed to be the nominal head of the construction as in (1a, b, c). However, when the N2 is an inanimate noun, the adjective may or may not agree. In (2a, b) the adjective agrees with the inanimate N2 (Hulk and Tellier, Reference Hulk, Tellier, Authier, Bullock and Reed1998: 185).

Examples of an adjective agreeing with the N1 instead of the N2 in cases of inanimate nouns appear in (3) (ibid):

The authors speculate that NS judgments would fluctuate between the two genders in (3c), so presumably, the adjective would agree with either the N1 or the N2. This “striking unease with the data suggests that the masculine form on the adjective/participle in [(3)] is not a reflex of agreement with N1, but rather the default gender choice” (ibid, 2000: 57). Unfortunately, the authors do not include any information about the FSs who provided these judgments or how they were elicited. Moreover, it is unclear what they mean by a default gender choice if agreement in either gender is acceptable. It may be more accurate to characterize (3c) as an example of indeterminacy or variability.

2.2. Past participles

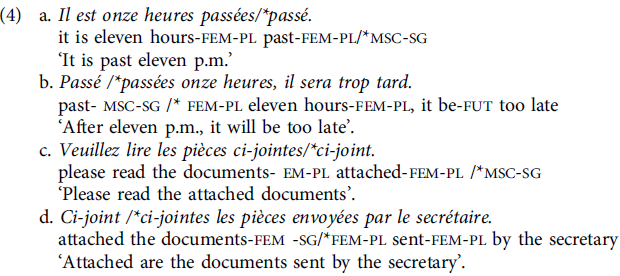

Some participles used as adjectives agree with the noun they modify only when they are postposed: ci-joint ‘attached’, approuvé ‘approved’, attendu ‘expected’, étant donné ‘given’, excepté ‘excepted’, (y-, non-)compris ‘included’, passé ‘passed’, supposé ‘supposed’, vu ‘seen/given’, as in (4)Footnote 3 :

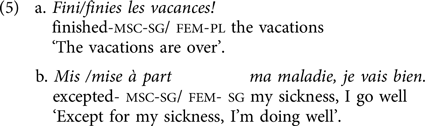

Agreement appears to be optional with fini ‘finished’ and mis à part ‘except for’Footnote 4 :

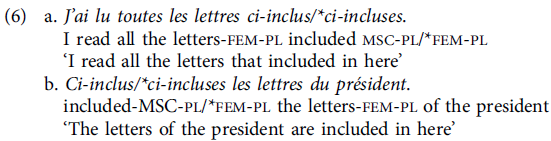

Finally, ci-inclus ‘included’ never agrees in gender or number with the noun it modifies, be it preposed or postposed as in (6).

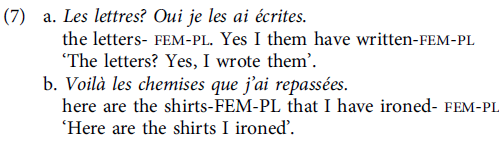

Past participles in compound tenses such as passé composé also agree in gender and number with direct object pronouns preceding them as in (7) (Bouchard, Reference Bouchard1997):

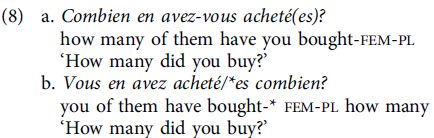

However, agreement is optional when there is overt wh-movement of the quantifier combien as in (8a), but not when combien remains in situ as in (8b):

Boivin (Reference Boivin1998) argues that the lack of agreement is an indication that there is no movement of the object through [Spec, AgrO]. Moreover, en does not agree with past participles, contrary to other direct object pronouns, as in (9):

Hence, the past participle agrees with the preposed (but not postposed) direct objects, but anecdotal evidence as well as oral data from a variationist perspective (e.g. Gaucher, Reference Gaucher2015) suggest that a few reflexive verbs tend to be difficult even for FSs such as se rendre compte de ‘to realize something’ (compte is the direct object) and causative faire as in elle les a fait couper ‘she had them cut’; whatever the object may be (e.g. flowers, hair), it is a complement of couper, not fait, so the past participle does not agree with the direct object.

2.3. Gender fluctuation with number

The gender of a few nouns fluctuates with number: orgue ‘organ’, délice ‘delight’ and amour ‘love’ are masculine in the singular, but feminine in the plural. Gens ‘people’ is an invariable plural noun with either male and/or female referents, but it agrees in the feminine with preposed adjectives and in the masculine with postposed adjectives as in les vieilles-fem /*vieux-masc gens sont heureux-masc /*heureuses-fem ‘old people are happy’. Moreover, les jeunes gens ‘young people’ is always masculine and the referents may be all masculine or both masculine and feminine, but not all feminine as in les jeunes gens intelligents-masc /*intelligentes-fem ‘the intelligent young people’.

2.4. Epicenes

There are several nouns with animate referents which are only masculine or feminine regardless of the gender of the referent. For instance, ange ‘angel’, bébé ‘baby’, témoin ‘witness’, génie ‘genius’ or ascendant ‘ancestor’ are masculine while victime ‘victim’, connaissance ‘acquaintance’, doublure ‘body double’ or personne ‘person’ are feminine. This is also the case for some titles such as Altesse ‘Royal Highness’, Eminence ‘Eminence’, Excellence ‘Excellency’ or Sainteté ‘holiness’ which are all feminine.Footnote 5

2.5. Invariable adjectives

Adjectives typically agree in number and gender with the noun they modify, but there are quite a few which are invariable in that they are not marked for gender or number such as color adjectives derived from nouns (e.g. argent ‘silver’, lavande ‘lavender’), with a few exceptions for both gender and number (e.g. violet(s)-msc-sg(pl) , violette(s)-fem-sg(pl) ‘purple’) or for gender, but not number (e.g. châtain/châtains ‘chestnut brown-sg-pl’). Adjectives of color modified by another adjective remain invariable as well (e.g. une jupe-fem gris-msc clair-msc ‘a light-gray skirt’) as do adjectives borrowed from other languages (e.g. clean, cool, halal, inuit, zen).

To summarize, French displays various idiosyncrasies in agreement alongside straightforward agreement within a noun phrase or a verbal phrase. The affective constructions appear to exhibit inherent variability depending on the animacy of N2, while the other cases (i.e. past participles, combien, gender fluctuation with number, epicenes and invariable adjectives) can be categorized as well established exceptions in standard, prescriptive grammars (e.g. Grevisse and Goosse, Reference Grevisse and Goosse2016; Riegel, Pellat and Rioul, Reference Riegel, Pellat and Rioul2018). The question is how do FSs react to these idiosyncrasies in an experimental setting? A study was designed to elicit their judgments with two different tasks. The stimuli included all the idiosyncrasies in agreement reviewed above. The causative and reflexive verbs are straightforward cases of agreement, but they were included because of anectodal evidence suggesting they may be difficult for FSs.

3. METHODS

3.1. Research questions

The main research question asks: will FSs’ performance align with prescriptive grammar with a minimun of 90% accuracy, or will it diverge from it and show individual differences? In other words, will FSs handle cases of idiosyncratic agreement as a homogeneous group because they share the same mental grammar, or will their performance be heterogeneous because their mental grammar allows for some indeterminacy and divergence from standard, prescriptive grammar?

If the FSs’ performance displays some indeterminacy, will it depend on: a) the elicitation task? b) the type of idiosyncrasies? c) their education level and/or age?

The N1 de N2 constructions will be examined separately because it is unclear whether adjectives agree with an animate N2, but not necessarily an inanimate N2. They are thus a case of indeterminacy in prescriptive grammar. Again, participants are expected to perform at least at 90% accuracy, the minimum criterion for L1 speakers (e.g. Dronjic and Helms-Park, Reference Dronjic and Helms-Park2014).

3.2. Participants and tasks

The participants are L1 French speakers (n = 168) who lived in various cities in France at the time of the data collection. Academic listservs were used to recruit professors and students who were then asked to enlist their friends and families in order to reach people of diverse socio-economic backgrounds. A background questionnaire revealed that the final composition of the participant pool included graduate students in M.A. or doctoral programs (n = 57), professors (n = 49), non-academic professionals with graduate degrees (n = 13), non professionals (high school graduates) (n = 35) and retired people (n = 14)Footnote 6 . 38 male and 130 female participants averaged 39.51 years in age (19–74 range) (Ayoun, Reference Ayoun2018).

The participants performed a grammaticality judgment task (GJT) and a preference/grammaticality judgment task (PGJT). Both tasks were written, computerized, and accessible from a website and without time limits. Upon completion, the participants clicked on a submit button and the raw data were saved to a folder so that they may be coded to run statistical analyses. The data collection was spread over three sessions: the participants completed the GJT during the first session, then the PGJT twice, once during session 2 and once during session 3.

The PGJT presented pairs of complete sentences that differed only by the presence or lack of agreement. Participants had to make two decisions with the help of pull-down menus: first choose the sentence they preferred, then indicate whether the other sentence, that is, the one they did not choose, was correct, incorrect or if they did not know. The stimuli included 24 pairs of sentences for each of the two sessions for a total of 48 sentences.

The GJT required the participants to indicate whether a complete sentence was correct, incorrect or if they did not know; they were asked to correct the sentences they rejected as incorrect. The stimuli included 64 complete sentences illustrating affective structures (n = 10), epicenes (n = 14), idiosyncrasies (as a general category including amours, orgues, Pâques, délices, n = 8), past participles (n = 5), causative (n = 6), reflexive verbs (n = 3), invariable adjectives (n = 3). The ‘don’t know’ option was included to reduce the possibility that participants would guess if they were unsure; having that information increases the reliability of their answers and provides an indication of their confidence levels. Participants were instructed to rely on their first intuition while performing both tasks.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Grammaticality judgment task

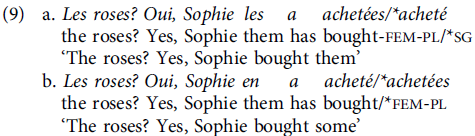

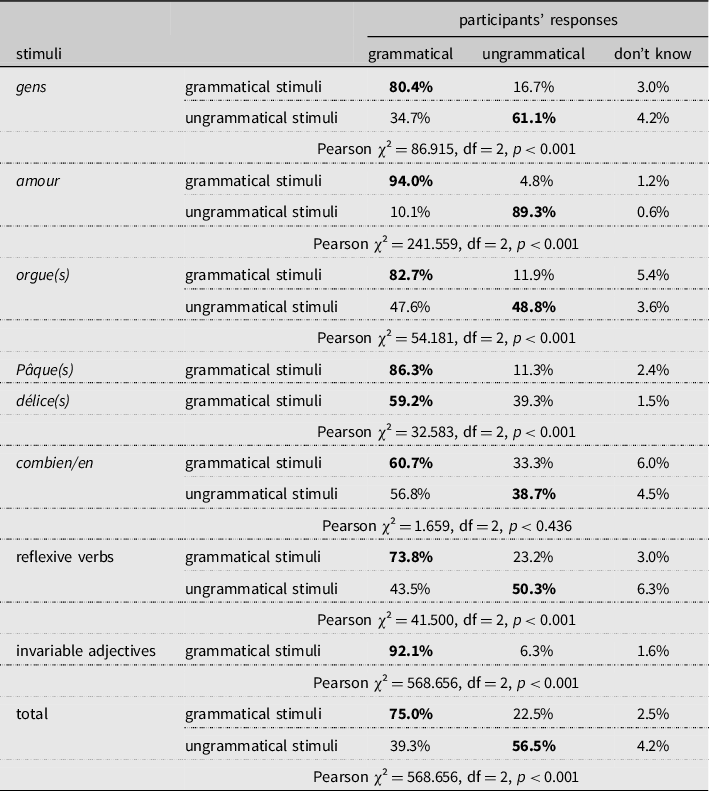

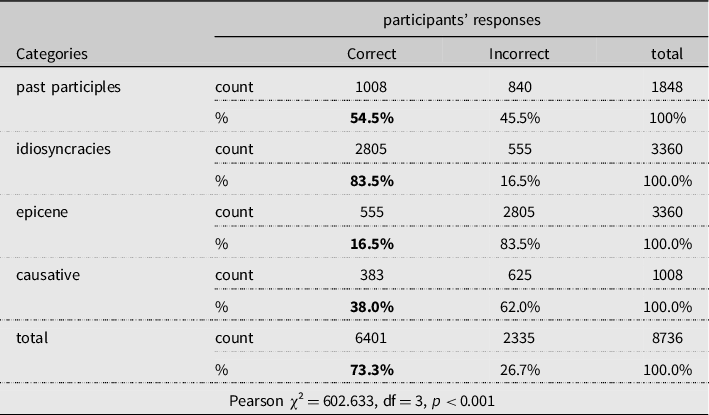

The accuracy means from a chi-square analysis are displayed in Table 1 and show that overall, participants performed relatively well in correctly accepting grammatical stimuli (84.1%), but poorly in rejecting ungrammatical stimuli (50.9%). The difference is statistically significant (p < .001). Their confidence levels measured by the ‘don’t know’ percentages are high since the percentages are low (2.7% overall).

Table 1. Overall accuracy means on the GJT

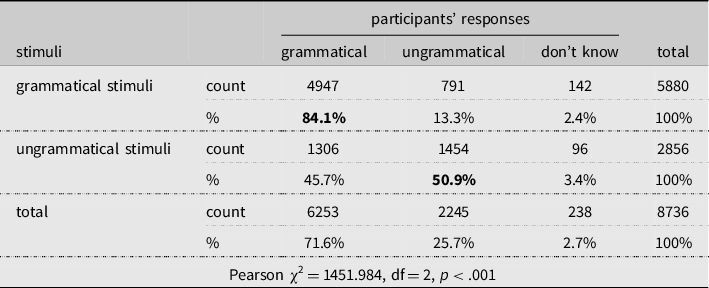

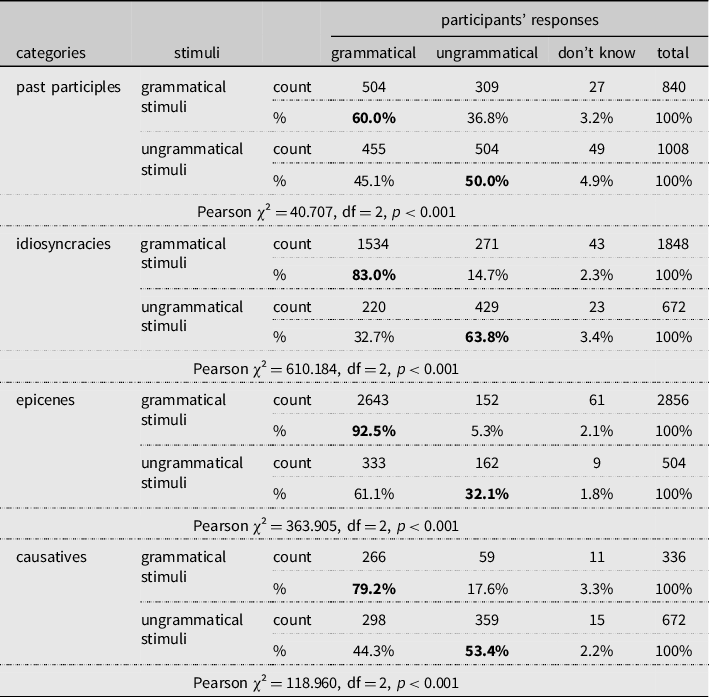

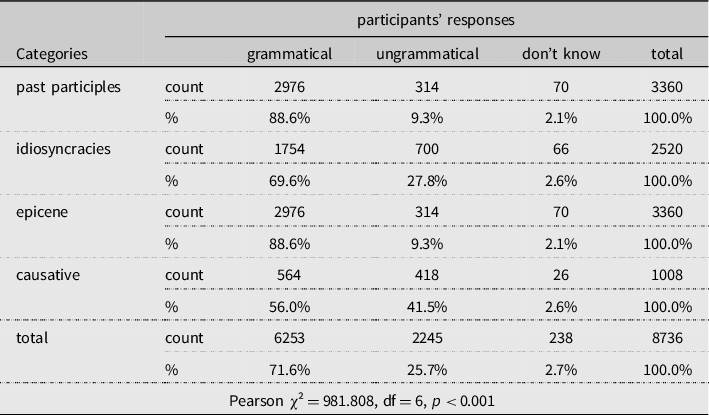

Table 2 displays accuracy means by categories which include everything but the N1 de N2 constructions which will be examined separately. The only accuracy mean above 90% is for the grammatical stimuli (92.5%) illustrating epicenes; the other means are much lower and always reflect a better performance on grammatical than ungrammatical stimuli. All the differences are significantly different. The ‘don’t know’ percentages vary a bit, but remain low 1.8%–4.9%).

Table 2. Accuracy means on the GJT by categories

Table 3 shows how the participants performed in each of the sub-categories of idiosyncrasies. With the exception of gens, amour, Pâque(s), the accuracy means for correctly accepting grammatical stimuli are much better than for correctly rejecting ungrammatical stimuli. The difference is statistically significant (Pearson χ² = 568.656, df = 2, p < 0.001). Pâque(s) and délice(s) had only grammatical stimuli. The 90% criterion is met only for amour and invariable adjectives. The ‘don’t know’ percentages vary from 0.6% for amour to 6.3% for reflexive verbs and concern ungrammatical stimuli in both cases.

Table 3. Accuracy means by categories of idiosyncrasies on the GJT

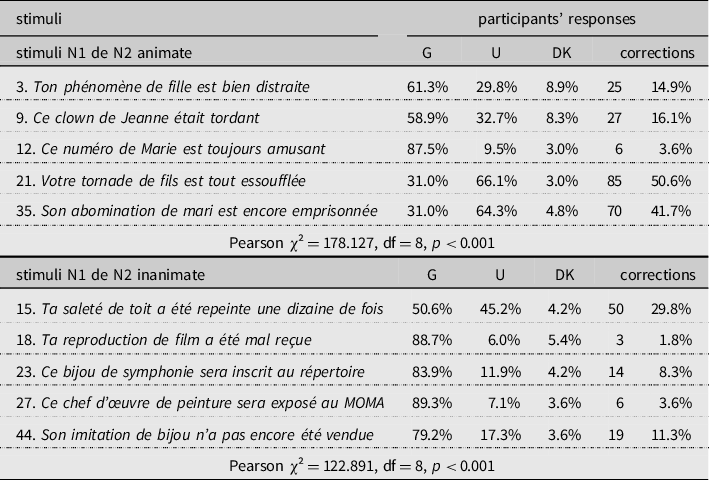

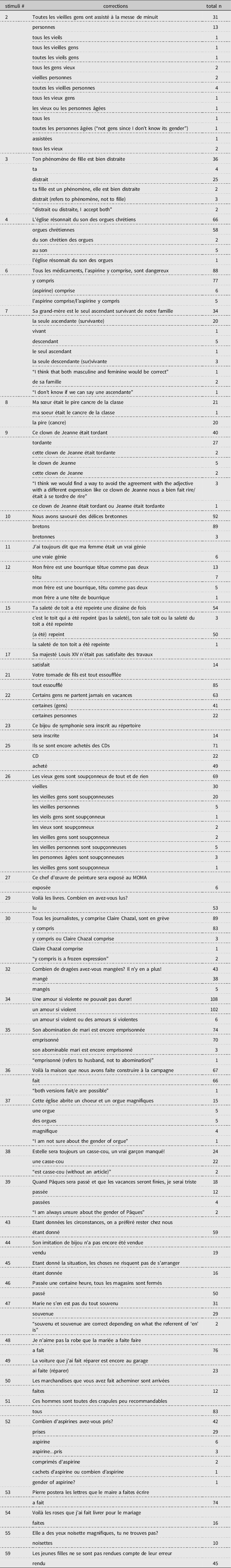

Table 4 shows the results for the N1 de N2 constructions. Participants indicated whether they thought the sentences were grammatical (G), ungrammatical (U) or if they did not know (DK). The ‘corrections’ column lists the number and percentage of participants (out of 168) who provided corrections to the sentences they rejected as ungrammatical (see Appendix A for the complete list).

Table 4. Findings by stimuli for N1 de N2 constructions

The results for animate nouns are mixed: with a feminine animate N2 (stimuli 3, 9, 12), participants tended to accept agreement with the masculine N1; however, with a masculine animate N2, they rejected agreement with a feminine N1. There is a stronger tendency to accept feminine agreement of an inanimate N2. The only stimulus (#15) with a feminine N1 and masculine N2 split the participants: 50.6% for accepting as grammatical and 45.2% for rejecting as ungrammatical.

The corrections indicate that participants generally preferred a masculine agreement for an animate N2 (41.7% and 50.6% of participants) as well as the inanimate N2 (29.8% of participants). Most of the causative corrections were appropriate (39.3% to 45.2% of participants), but erroneous corrections were provided for 4 grammatical stimuli by a small percentage of participants (7.1% – 13.6%). Gens generated numerous corrections in addition to the appropriate certaines gens (24.4% of participants), most replaced gens with certaines personnes or les vieilles personnes. The past participles of reflexive verbs were appropriately corrected, but to varying degrees (se sont acheté, 29.2%; s’est souvenue, 17.3%; se sont rendu compte, 26.8%). Participants’ corrections showed they preferred a lack of agreement for combien (livres, 31.5%; dragées, 22.6%), but not aspirines (17.3%; and seven other corrections). The past participles were generally appropriately corrected (y compris, 45.8% to 49.4%; étant donné, 35.1%; passé, 29.8%), with only a few erroneous corrections for étant donné (9.5%). The epicenes generated a few overcorrections (ascendant, 13.7%; cancre, 11.9%). The nouns with a fluctuating gender with number were appropriately corrected (e.g. orgues, 34.5%; amour, 60.7%); but 53.7% of the participants erroneously corrected délices.

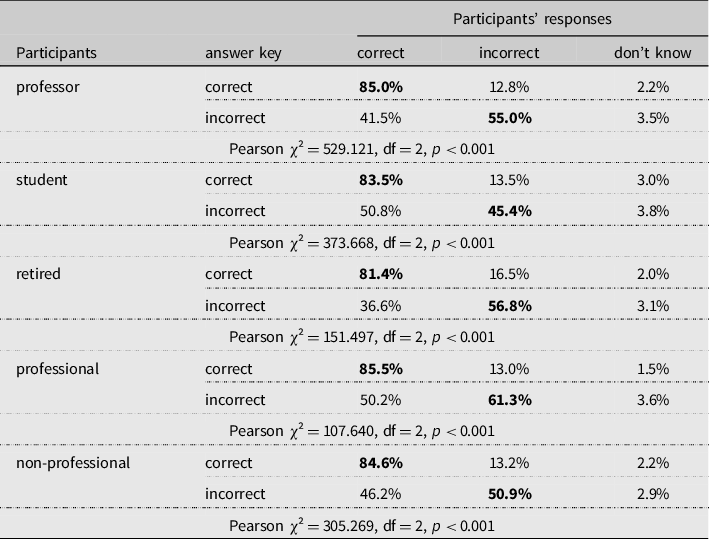

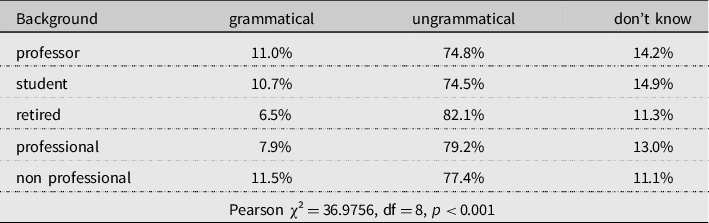

The results of the chi-square analysis in Table 5 reveal a significant difference between correctly accepting (81.4%–85.5%) and correctly rejecting (45.4%–61.3%) stimuli for each of the five groups of participants. The professional group performed best followed by the professor, retired, non-professional and student groups.

Table 5. Accuracy means by participant background

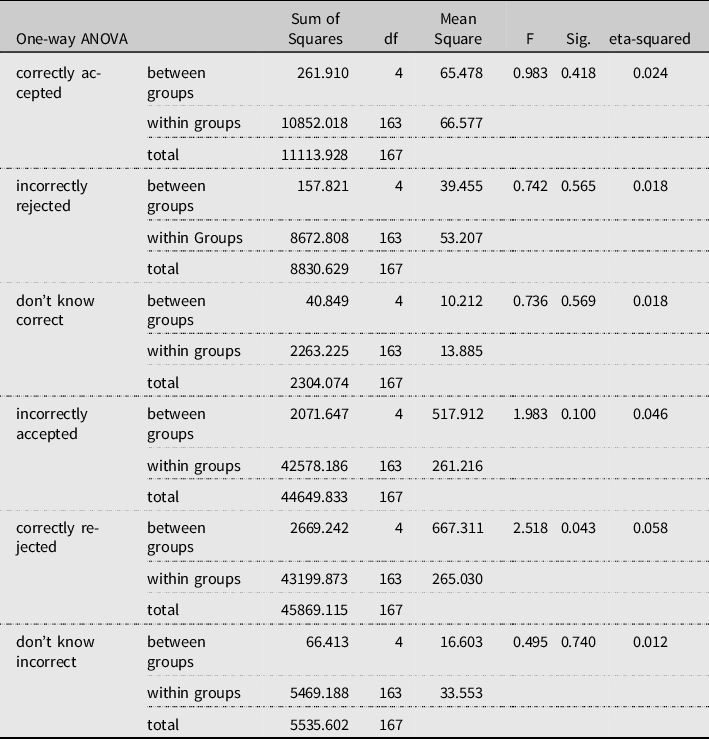

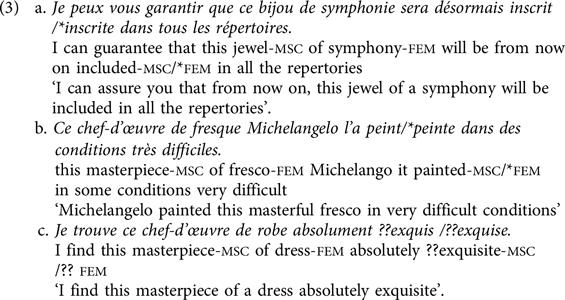

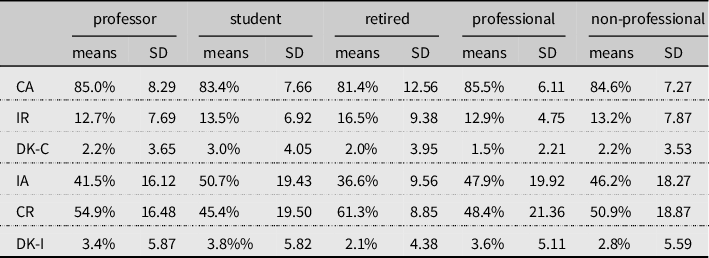

An ANOVA was performed to obtain finer-grained results. Accuracy means are displayed in Table 6 by correctly accepted (CA), incorrectly rejected (IR) and don’t know correct (DK-C) for grammatical stimuli; correctly rejected (CR), incorrectly accepted (IA) and don’t know incorrect (DK-I) for ungrammatical stimuli.

Table 6. ANOVA results by participant background

The average for IR is 13.7% with a 12.7%–16.5% range, while the means average for IA is 46.98% with a 40.1%–51.1% range, so participants clearly failed to reject quite a few ungrammatical stimuli. The participants’ performance decreases from retired (56.8%) to professor (51.6%), non-professional (47.7%), professional (45.8%) and student (44.1%) for CR. The SDs vary quite a bit as well suggesting individual differences between the participants. A statistically significant difference between groups was found for correctly rejected stimuli (sum of squares = 2669.242, df = 4, mean square = 667.311, F = 2.518, p = 0.043, Eta-squared = 0.024). A post hoc Tukey test revealed that the only difference approaching significance was between the student and the retired groups (mean difference = -12.74, standard error = 4.856, p = 0.071).

In order to see whether age was a factor in the participants’ performance in addition to their education level, we ran a Pearson correlation test. We found a positive correlation for correctly rejected stimuli (r = .260, p < 0.001), a negative correlation for incorrectly accepted stimuli (r = −.235, p = 0.002), and a small positive correlation between a correct percentage (combining correctly accepted and correctly rejected stimuli) (r = .159, p = 0.039). There was no correlation for correctly accepted stimuli alone or the ‘don’t know’ percentages.

Finally, we ran an ANOVA with a subset of the participants (n = 25), those who had obtained at least 90% on correctly accepted stimuli (see Appendix C for complete results). The means range from 92.1% to 97.4% for correctly accepted stimuli (CA), and they are close on incorrectly rejected stimuli (IR) (0.0%–7.9%). However, the most interesting finding is regarding ungrammatical stimuli: although they performed as expected on CA, there is a wide variation between participants for rejecting ungrammatical stimuli (CR) with accuracy means ranging from 17.4% to 73.9%. The post hoc Tukey test shows that the mean difference (−12.7438) between students and retired almost reaches statistical significance (p = 0.071). For instance, participant 4 obtained 94.7% (CA) and 5.3% (IR) on grammatical stimuli, but only 39.1% (CR) and 39.1% (IA) on ungrammatical stimuli; the ‘don’t know’ percentage also jumps from 0.0% for grammatical to 21.7% for ungrammatical stimuli.

4.2. Preference/grammaticality judgment task

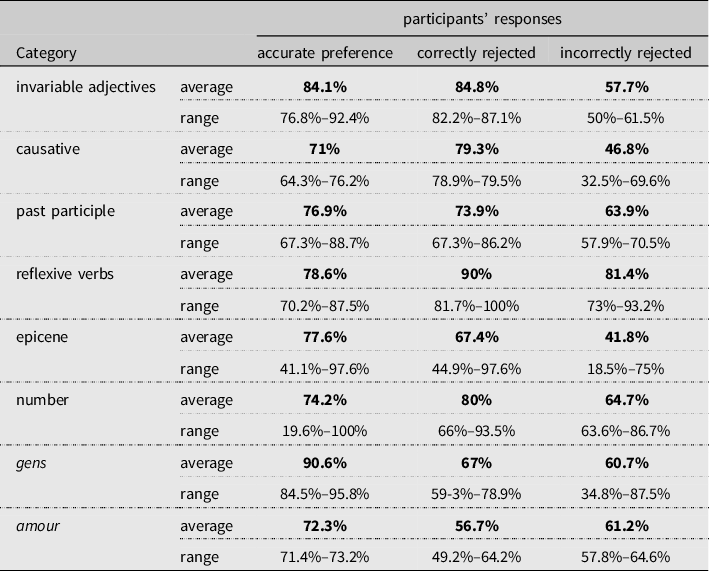

The statistical analyses combined the raw data from both sessions. The reader may recall that participants first indicated which of two sentences they preferred and then whether the other sentence was (un)grammatical or they did not know. Table 7 displays the accuracy means for the preferred sentences, while Table 8 shows how the participants rated the other sentence.

Table 7. Preferred sentence accuracy means

Table 8. Non-preferred sentence grammaticality

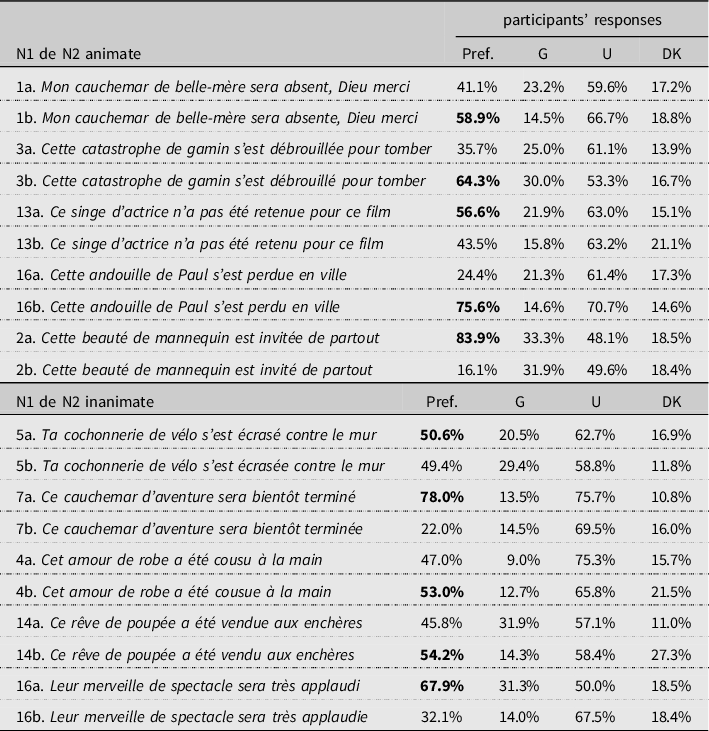

Hulk and Tellier’s predictions are supported for animate nouns since participants chose the sentence where the masculine or feminine N2 agrees with the adjective for four out of five stimuli. The predictions are also supported for inanimate nouns since Hulk and Tellier argue that the adjective may or not agree and participants are almost evenly split: the N2 agrees with the adjective for three out of five stimuli. However, they reject a slightly greater number of sentences as ungrammatical for inanimate versus animate nouns (64.4% vs 59.4%). The accuracy means for the other idiosyncrasies range from 71% to 75.2% and are even lower for rejecting ungrammatical sentences in the second part of the task (63.3% to 74.3%). The ‘don’t know’ percentages are much higher than for the GJT, indicating lower confidence levels.

Tables 9 and 10 show accuracy means by participant backgrounds for the preferred sentence and grammaticality of the rejected sentence. They are significantly different for the latter, but not the former, with the retired group obtaining the highest means (82.1%) followed by the professional group (79.2%), while the students and professors obtained the lowest means (74.5% and 74.8%, respectively).

Table 9. Preferred sentence accuracy by participant background

Table 10. Non-preferred sentence grammaticality by participant background

Table 11 displays the detailed findings for the N1 de N2 constructions.

Table 11. N1 de N2 constructions

The ‘pref(erence)’ column shows the percentage of participants who preferred sentence (a) or (b); the next three columns indicates how they rated the other sentence, that is, the sentence they did not select. For instance, 41.1% of the participants preferred sentence (1a) and the other sentence was rated as grammatical by 14.5%, ungrammatical by 66.7%, while 18.8% did not know.

Participants always prefer for the animate N2 to agree with the adjective whether it is masculine or feminine. With an inanimate N2, there is no clear preference: agreement can be with N1 (i.e. stimuli 7a, 14b) or N2 (i.e. stimuli 5a, 4b, 16a), regardless of gender.

The complete results for the other categories appear in Appendix B. They are summarized in Table 12.

Table 12. Accuracy preference/(un)grammaticality

The ‘accurate preference’ column shows the percentage of participants who selected the grammatical stimuli and the next two columns indicate the percentage who correctly rejected ungrammatical stimuli and incorrectly rejected grammatical stimuli. Only gens meets the 90% criterion with a 90.6% average, but participants rejected almost as many grammatical (60.7% average) as ungrammatical stimuli (67% average). The participants’ performance in the other categories is well below 90% with a wide range depending on the stimuli. They perform best at rejecting ungrammatical stimuli with reflexive verbs and worst with amour.

Table 12 does not include combien because agreement is optional when there is overt movement and that is reflected in the participants’ responses who are almost equally split between agreement (56.3%) and non agreement (54.9%), but a larger percentage of participants reject the former than the latter as ungrammatical (average of 80.1% and 61%, respectively). The ‘don’t know’ responses range from 2.5% to 26.5%.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

FSs performed two different elicitation tasks exemplifying various cases of idiosyncratic agreement to address the main research question of whether their performance would align with prescriptive grammar or would diverge from it and show individual differences. The results support the latter since the participants’ performance rarely reached the 90% criterion expected of L1 speakers.

On the GJT, the highest percentage of 92.5% is for epicenes on correctly accepted stimuli, but they rejected only 32.1% of ungrammatical stimuli; they performed equally poorly at rejecting ungrammatical stimuli for idiosyncrasies (63.8%) and causatives (53.4%) while correctly accepting 83.0% and 79.2% of the stimuli, respectively. The participants’ performance was equally poor on the PGJT. Aside from the particular case of affective constructions, participants preferred the correct sentence for 71%, 71.8% and 75.2% of the causatives, epicenes and idiosyncrasies, respectively. They tended to rate the non-preferred sentences as ungrammatical (69.8%, 63.3% and 74.3%, respectively).

Since the FSs’ performance displayed some indeterminacy, we can address the other research questions. First, their performance did depend on the elicitation task. Overall, they performed better at accepting grammatical stimuli than rejecting ungrammatical stimuli on the GJT. But, excluding affective constructions, their highest accuracy means when selecting the sentences they preferred on the PGJT is only 83.5%. Even when they selected the appropriate sentence, they sometimes failed to reject its ungrammatical counterpart. Participants also provided some ungrammatical corrections to sentences they had appropriately rejected on the GJT.

This uneven performance betrays an uncertainty on the part of these FSs in spite of their confidence levels which were generally high, but not always. They were more confident on the GJT (0.6%–6.3% of ‘don’t know’ responses) than on the PGJT (11.7%–17.3% for the non-preferred sentence grammaticality and up to 27.3% for affective constructions). L1 speakers’ confidence is generally high with ceiling performance on various tasks as with Italian L1 speakers whose accuracy on a written grammatical gender assignment task ranged from 90.0% to 99.7% along with negligible ‘don’t know’ percentages (0%–0.1%) (Ayoun and Maranzana, Reference Ayoun, Maranzana and Ayoun2022).

L1 speakers are also typically able to correctly accept grammatical stimuli while correctly rejecting ungrammatical stimuli. For instance, in Kail (Reference Kail2004), French adults were highly accurate in their performance of an on-line sentence processing task, failing to detect grammatical violations only 3.7% of the time. Our participants’ failure to reject an average of 45.7% of ungrammatical stimuli is thus surprising and difficult to explain if one assumes that L1 speakers’ mental grammars follow prescriptive rules.

Second, the FSs’ performance depended on the category of idiosyncrasies. They did well with amour, invariable adjectives and epicenes on the GJT, but only 60.0% of participants correctly accepted participles, for instance. The appropriateness of the corrections depended on the type of participles, exposing another indeterminacy. The PGJT reveals a variable performance as well: participants did well with invariable adjectives and gens, but had high means for incorrectly rejecting grammatical stimuli exemplifying participles and reflexive verbs.

Third, their personal background partially influenced the FSs’ performance. The education level impacted the accuracy means for correctly accepting sentences on the GJT (from 81.4% for retired to 85.0% for professor and 85.5% for professional); there is a bigger difference between groups on correctly rejecting sentences that is less dependent on the level of education (45.4% for student to 61.3% for professional). In addition, positive correlation was found between age and correctly rejected stimuli (r = .260, p < 0.001), a negative correlation for incorrectly accepted stimuli (r = −.235, p = 0.002), and a small positive correlation with the overall correct percentage (r = .159, p = 0.039). In other words, older participants performed better than younger participants.

Regarding affective constructions, Hulk and Tellier’s predictions were supported: the adjective agrees with an animate N2, but not necessarily with an inanimate N2. It appears that the participants’ performance reflects the indeterminacy present in the grammar itself. Indeed, indeterminacy is part of language which is naturally reflected in L1 grammarsFootnote 7 . We acknowledge the small number of stimuli for both animate and inanimate nouns. Future studies should include a larger number of both. Also, since Spanish exhibits similar affective constructions, it would be interesting to compare L1 French and L2 Spanish participants on at least two different elicitation tasks with similar stimuli.

These results are thus consistent with those obtained on a gender assignment task, the first task these participants completed: strong lexical and gender effects with an overall accuracy of 72.5% and a significantly better performance on masculine nouns (82.4%) than feminine nouns (73.8%) or nouns which are both masculine and feminine (61.5%) were found. The participants’ performance also depended on whether the stimuli were simple nouns or compounds, common or uncommon, or had a vocalic or consonantal initial. A strong lexical effect confirmed the hypothesis that gender must be acquired for each individual lexical item (Ayoun, Reference Ayoun2018).

The results are also consistent with previous studies showing individual differences in adult L1 speakers. How do we account for them and should we attempt to reconcile participants’ performance on structures illustrating prescriptive rules of standard grammars? From a generative perspective, it was assumed that a grammar is “descriptively adequate to the extent that it correctly describes the intrinsic competence of the idealized native speaker” (Chomsky, Reference Chomsky1965: 24). In that sense, current standard grammars do not describe our FSs’ competence, if their performance is an accurate reflection of their competence. Thus, grammars could adopt a more flexible approach and relax their prescriptive rules, or we could accept FS variability as proposed by Hulstijn (Reference Hulstijn2015) with the BLC-HLC (Basic Language Cognition-High Language Cognition) theory within a usage-based perspective. Basic language cognition is defined as the language cognition that all L1 speakers share, while differences are observed in higher, extended language cognition. BLC is limited to frequent grammatical structures and common lexical items in speech, while HLC applies to infrequent morphosyntactic structure and uncommon lexical items, both in written and spoken language. The BLC-HLC theory is supported by a growing number of studies investigating various morphosyntactic structures. They show that age and education level impact L1 speaker performance (see Hulstijn, Reference Hulstijn2015 for an extensive review; Hulstijn, Reference Hulstijn2011, Reference Hulstijn2017, Reference Hulstijn2019, Reference Hulstijn2020). The idiosyncrasies tested here would thus fall under HLC.

L2 acquisition studies should take L1 speaker variability into account (e.g. Mulder and Hulstijn, Reference Mulder and Hulstijn2011) and provide more background information about their L1 speaker controls who tend to be highly educated participants, thus accentuating differences between L1 speakers and L2 learners (e.g. Dąbrowska, Reference Dąbrowska2019). Future research focusing on language learners in general would benefit from it.

Finally, noticeable differences among L1 speakers across different elicitations tasks and morphosyntactic structures strongly suggest that we need to heed the increasingly loud call to revise our definition of the prototypical L1 speaker. Although few voices would still claim as structuralists Pike (Reference Pike1947) or Nida (Reference Nida1949) did that L1 speakers are infallible and always right, L1 speakers are still idealized and reaching a “native-like” competence is still seen as the goal of L2 learners, setting them up for failure (e.g. Birdsong and Gerken, Reference Birdsong and Gerken2013). The “native speaker’s myth” has been dispelled (e.g. Ayoun, Reference Ayoun2018) with clear consequences for L2 learners as well as for the debate between competence, performance and prescriptive norms. Future studies could collect information about their participants’ attitudes and beliefs regarding their L1 to inform that debate.

Although the difficulties of providing a better definition for an L1 speaker is no easy task and is beyond the scope of the current study, it is a necessary one, particularly from an L2 acquisition perspective (see e.g. Bonfiglio, Reference Bonfiglio2013; Dewaele, Bak and Ortega, Reference Dewaele, Bak and Ortega2021; Escudero and Sharwood Smith, Reference Escudero and Sharwood Smith2001; Joseph, Reference Joseph2017).

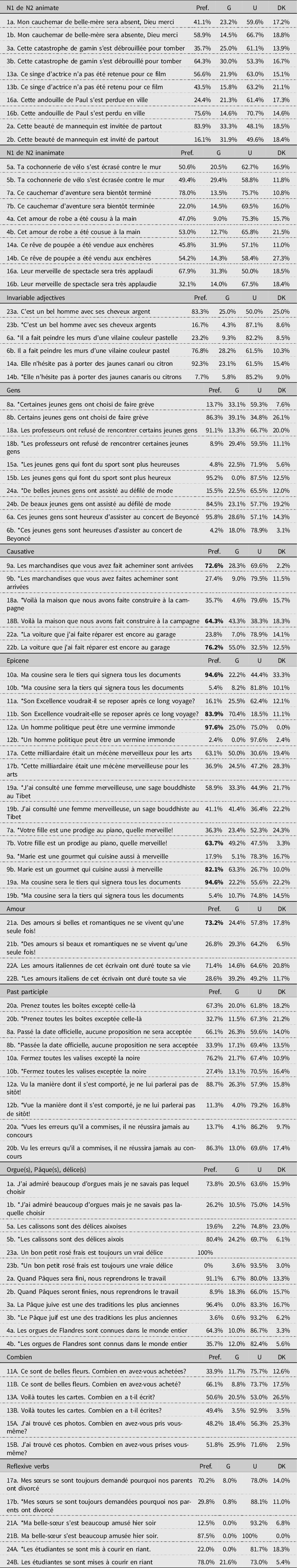

Appendix A Corrections to the grammaticality judgment task

Appendix B Preference task results by categories (sessions 2 and 3)

Appendix C Results from participants (n = 25) who obtained above 90% for CA on GJT