1. INTRODUCTION

One notable grammatical change in the history of French is the loss of bare nouns. While it was still possible to use bare nouns in Medieval French, this possibility seems to have been reduced over time, especially as compared with other Romance languages (Carlier and Lamiroy Reference Carlier and Lamiroy2018a, Reference Carlier and Lamiroy2018b; for Germanic, see Skrzypek, Piotrowska and Jaworski Reference Skrzypek, Piotrowska and Jaworski2021). Although quantitative information is provided in some studies (notably Simonenko and Carlier Reference Simonenko and Carlier2020b for the period before 1400, and Simonenko and Carlier Reference Simonenko and Carlier2020a before 1700), the general progression of the loss remains to be charted, in terms of e.g. syntactic and semantic correlative factors.

Demonstrating the impact of syntactic function on bare noun loss is what this article aims to do. It uses corpora of non-fictional prose calibrated for genres (three text types from the legal and historiographical domains) and region (Normandy) together extending over 8 centuries (from the 12th to the 19th century) to do so. Function is shown to correlate to the bare noun loss, from central to peripheral functions, alongside the Accessibility Hierarchy (Keenan and Comrie Reference Keenan and Comrie1977).

First, the article discusses studies of bare noun evolution. The method by which a systematic investigation of the evolution is conducted is then explained. The rates of use of bare nouns in the selected diachronic corpora are then presented; and the syntactic pattern of change is discussed and speculated upon. The proposals are summarized in the conclusion, which identifies issues for future research.

2. STATE OF THE ART

The NPFootnote 1 generally contains a determiner in contemporary French (Abeillé and Godard Reference Abeillé and Godard2021: chapter V). There are no argumentalFootnote 2 contexts of use (as is the case with English bare plurals, or Italian bare mass nouns) in which a French NP can commonly be found without a determiner (Lauwers Reference Lauwers2012). This contrasts with other Romance languages: Carlier and Lamiroy (Reference Carlier and Lamiroy2018a), who study the emergence of the determiner category (see also Combettes Reference Combettes2001), cite figures of 20 % of bare nouns in Spanish and 15% in Italian, as compared to 6% in contemporary French, where bare nouns are restricted to specific cases such as proper nouns (1) and nouns with metalinguistic reference (2).

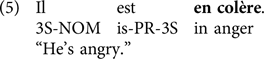

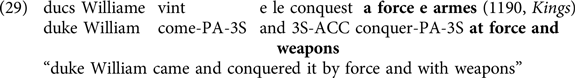

Specific constructions of higher registers, such as coordination illustrated by (3) (Roodenburg Reference Roodenburg2004, Märzhäuser Reference Märzhäuser, Kabatek and Wall2013, Riegel et al. Reference Riegel, Pellat and Rioul2014: 308–315), and idiomatic expressions in object (see (4), Chaurand Reference Chaurand1991, Gross et Valli Reference Gross and Valli1991) and oblique functions (see (5), Anscombre Reference Anscombre1991a and Reference Anscombre1991b, Vigier Reference Vigier2017) also allow nouns to be used without a determiner.

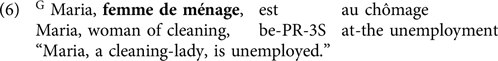

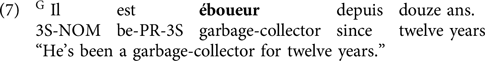

And so do bare nouns in appositive and predicative functions (Beyssade Reference Beyssade, Pogodalla, Quatrini and Retoré2011, Lauwers Reference Lauwers2014).

The suggestion is that across these constructions, bare noun relates to a property rather than a delimited entity (notably Anscombre Reference Anscombre1991a, Reference Anscombre1991b): it is not a particular foot that is evoked in (4), but the notion of one’s footing. Property denotation is a recurring factor of bare noun use. However, other factors must also be involved, since proper nouns, which are generally used without a determiner, definitely have a referential value.

How did bare nouns in contemporary French get restricted to a disparate set of environments? The rates, functions, and semantic values discussed by diachronic studies are evoked in the following paragraphs.

It is useful to remember that bare nouns are thought to be the default case in Latin (Pinkster Reference Pinkster2015: 48–50): Carlier and Lamiroy (Reference Carlier and Lamiroy2018a) cite a figure of 77%. Although the language has possessive, demonstrative and numeral items with the noun, they are considered akin to modifiers by Sornicola (Reference Sornicola2009: 33–34) and are thought to gradually evolve as members of the determiner class in Gallo-Romance.

Rates of bare nouns over the history of French are provided by various studies (see Sakari Reference Sakari1988, Haussalo Reference Haussalo2014). Carlier and Lamiroy (Reference Carlier and Lamiroy2018a) propose 32% in Old French and, as mentioned, 6% in Modern French. Reporting on two translations of Cicero’s De Inventione in 1282 by Jean d’Antioche and in 1932 by de Bornecque, and where the Latin original contains 86,66 % of bare nouns, Goyens (Reference Goyens1994) identifies figures of 40,76 % in Old French and 15,98 % in contemporary French. Similarly, Saikali-Sleiman (Reference Saikali-Sleiman2006)’s dissertation studies the distribution of bare nouns in three successive versions of the Conquête de Constantinople (by Villehardouin at the beginning of the 13th century, in the 1585 translation by Blaise de Vigenère and in the 1939 translation by Edmond Faral). The overall proportions are at 33%, 40% and 27%, with an unexpected rise in the 16th century,Footnote 3 and surprisingly little change between the initial and the final period. More extensive quantitative documentation is provided by Simonenko and Carlier (Reference Simonenko and Carlier2020b: 221). Banking on the MCVF, they show that bare nouns are receding from the 1100 to the 1600. However, the progression is irregular, with an unexpected higher rate of bare nouns in the 1500 than in the 1400 in subject position, as well as in the 1200 and the 1500 as compared to the 1100 and the 1400 in object position (see their Figure 11). This is likely due to the heterogeneous nature of the corpus (on regularity provided by homogeneous corpora, see the discussion and results in Vigier Reference Vigier2015, Reference Vigier2017).

Regarding function, in Old French, bare nouns are found in all of them (Marchello-Nizia Reference Marchello-Nizia1999: 76), although in no function are they the default option (Marchello-Nizia et al. Reference Marchello-Nizia, Combettes, Prévost and Scheer2020: 973). Saikali-Sleiman (Reference Saikali-Sleiman2006) notes that real declineFootnote 4 is manifested with subjects (53%, 29% and 18%) and direct objects (38%, 33%, 29%). No significant change is however noted after prepositions (mostly concerning à “to”, de “from”, en “in” and pour “for”) that go from 29% to 43% and 28%.Footnote 5 Some further quantitative data is provided by Marchello-Nizia et al. (Reference Marchello-Nizia, Combettes, Prévost and Scheer2020: 972–973), who cite 3% of bare nouns in subject position at the end of the 15th century (in a historical text by Commynes), and 0% by the middle of the 16th century (in Calvin’s sermons).Footnote 6 Simonenko and Carlier (Reference Simonenko and Carlier2020a) contrast bare nouns in subject position (going from about 25%, to 20%, to 18%, to 15%, to 18% and 15% for the 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th and 17th, judging from their Figure 11) and in object position (from 40% downward to about 35%). The progression seems however more conservative than has been observed in other studies, calling for complementary studies. A similar sensitivity to syntactic function has also been observed for partitive determiners by Carlier and Lamiroy (Reference Carlier and Lamiroy2018b). Non-quantitative approaches note that bare nouns in object position are increasingly found in set expressionsFootnote 7 through time (Gross and Valli Reference Gross and Valli1991).

The semantic contribution of bare nouns relates to lack of individuation of the NP’s referent according to Foulet:

si l’individualité ne ressort pas nettement, si nous avons affaire à un type plutôt qu’à un individu, ou si l’individu nous est présenté comme devant satisfaire à telles ou telles conditions qui pourront être ou ne pas être rempliesFootnote 8 (Foulet Reference Foulet1929: 56)

This seems convergent with the cases listed by Buridant (Reference Buridant2019: 147–153). However, disagreement as to the property-denoting reference of bare nouns is expressed by Marchello-Nizia et al. (Reference Marchello-Nizia, Combettes, Prévost and Scheer2020: 973) for whom there is no unique meaning to the absence of determiners, since such absence is compatible with proper nouns and nouns evoking a unique referent (8), as well as with generics (9), plural indefinites (10), mass (11) or abstract (12) nouns, following the examples they cite.

Carlier and Lamiroy (Reference Carlier and Lamiroy2018a) suggest that the bare nouns are used with singular and plural count nouns in the 14th century, with plural count and mass nouns in the 15th and 16th, before disappearing in the 17th. According to Foulet (Reference Foulet1929), the decline is related to bare nouns being challenged by the emergence of the indefinite article, that would have a similar meaning contribution, and would increasingly be found with nouns with an indefinite and abstract interpretation (see also Déchaine et al. Reference Déchaine, Dufresne and Tremblay2018, and Simonenko and Carlier Reference Simonenko and Carlier2020b).

The existing studies support the view that bare nouns are a declining grammatical option, whose productivity is gradually eroded by function, types of nouns, and collocations. Regarding function, it looks as though bare nouns in Medieval French disappear from subject function, decline as direct objects, and regress in obliques, although there are considerable disparities in numbers from homogeneous corpora (such as translations), and variability in heterogeneous databases. As for types of nouns, there is little agreement in the literature, probably due to the difficulty of diagnosing property denotation in actual usage through history. Subsisting uses of bare nouns seem to be increasingly engaging in collocations, although again the identification of collocative uses diachronically raises methodological issues. The first question is what this study of the evolution of bare nouns in Medieval French focuses on. How it intends to proceed is presented in the next section.

3. METHOD AND CORPUS

The purpose of this article is to conduct a systematic investigation of one potential syntactic correlate of the declining use of bare nouns in the history of the French language.

Development is ideally perceptible in data calibrated through the documented period. Such a calibrated corpus is difficult to assemble for several well-known reasons. As we go back in time, the set of available texts is narrower, they tend to be heterogenous in nature, size and geographical origins; texts of a literary genre can be archaic and their stylistic pursuit can make them unreliable witnesses of effective language evolution (Prévost, Reference Prévost2015; Goux and Larrivée, Reference Goux and Larrivée2020). Fortunately, these difficulties are gradually being resolved by new resources, with tools that support data identification and extraction.Footnote 9

Among these resources, the MICLE and Chroniques corpora provide calibrated data through time.Footnote 10 The objective of their creation was to reduce data heterogeneity. By proposing prose texts written only in Normandy, they contribute to eliminating undue diatopic influences; by each selecting non-fictional texts relating to the same domain of activity, they present data that are mostly exempt from the stylistic pursuit characteristic of literary texts. Such calibrated corpora of non-literary material have been shown to provide a more stable and regular picture of language change (Goux and Larrivée Reference Goux and Larrivée2020; Goux Reference Goux2022b).

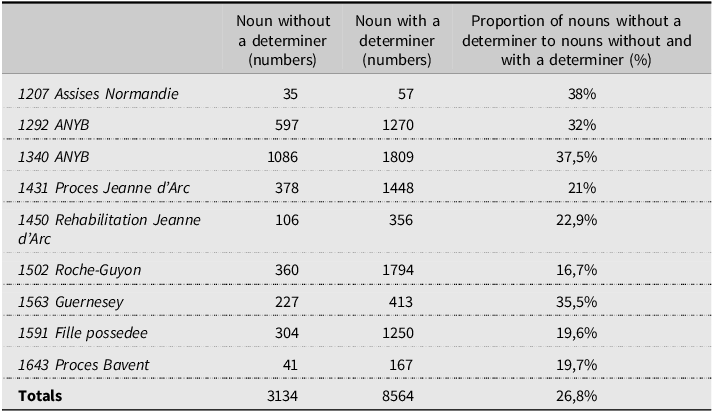

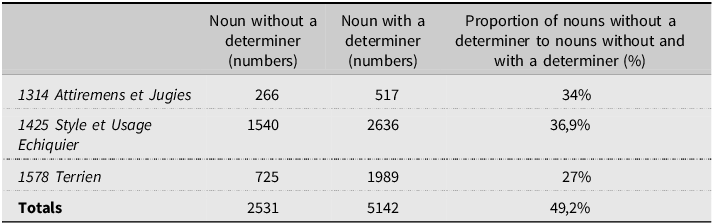

The texts from MICLE belong to two different genres: trial material is listed in Table 1 Footnote 11 and the procedure styles, that explain procedure to be followed in court, are in Table 2.

Table 1. Trial material from the MICLE corpus

Table 2. Procedure styles from the MICLE corpus

While the first set runs over five centuries, the second is limited to three, but is concentrated on the period where change is believed to be decisive.

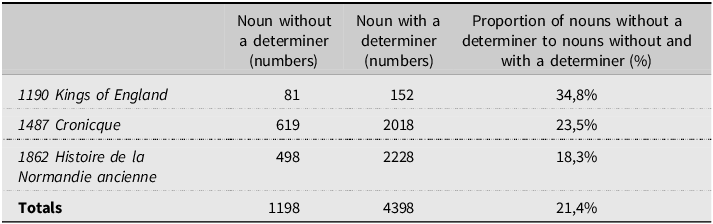

A third genre was added from the corpus Chroniques, and the text that were ready to exploit at the time of writing are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Material from the Chroniques corpus

These cover the very beginning, middle and end of the documented period. Although offering three different types of temporal distribution, using three text types has the added benefit of controlling for outlier results and distortions that may be due to a specific text, or text types.

Once the texts had been digitized and transcribed, tokens were lemmatized and tagged following the Universal Dependencies guidelinesFootnote 17 with the HOPS syntactic parser (Grobol and Crabbé Reference Grobol and Crabbé2021). The parser first identifies the POS (“part of speech”) of the token; then the dependency relations between tokens and the nature of that dependency relation, such as subject, direct object, oblique.Footnote 21 The files generated by the HOPS parser (known as a CONLL-U files) were then converted into XML-TEI files through a Python scripts specifically developed for the MICLE project, and uploaded unto the TXM software (Heiden et al. Reference Heiden, Magué and Pincemin2010), to allow CQL requests to be made.Footnote 22

We used the following query to spot the occurrences of bare nouns in the corpora:

a:[udpos!=”DET”][udpos!=”DET”]{0,2}[udpos=”NOUN” & function=”xxx” & n=a.head]

The attribute “udpos” allow us to search for a specific POS in the UD tagset;Footnote 23 and the “!=” to exclude the POS in question, and return all other POS. The accolades {0,2} define an interval between the head of the NP and the noun, and the function of the NP is captured by the tag “function”, whether it be nominal subject (nsubj), direct object (obj) and oblique (obl). The initial element of the request, “a:” captures all the information relating to the first member of the NP, and ensures that the search is done within the boundaries of the NP (as defined by the dependents of the head noun).

Once the occurrences have been automatically retrieved using TXM, we examined them manually to eliminate false positives (mainly due to residual tagging errors in the corpora). The general principle for bare noun identification was that a determiner such as the (in)definite article could have been used at that time but was not. That is why proper nouns were left out of the searches, as they are but rarely used with a determiner. For the same reason, quantified phrases such as beaucoup de “a lot of N” that came out in the searches were not counted as bare noun. However, since a determiner can precede the noun in those structures, a bare noun after a partitive in a negative context (pas de N, “no N”) was.

Having explained the methodological choices of corpus selection and data extraction, we now turn to the evolution in the rates of use of bare nouns with regards to the central factor of syntactic functions.

4. BARE NOUNS LOSS IS IMPACTED BY SYNTACTIC FUNCTION

4.1 Bare nouns in subject function

We start by presenting the results of the investigation of the evolution of Medieval French bare nouns through time in the subject function, where it is believed to be first lost.

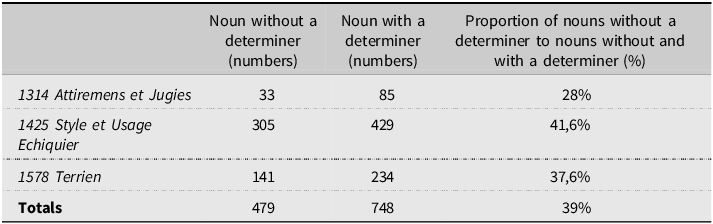

Rates of subject bare nouns in the trial material of the Micle corpus, as compared to the sum of nouns without and with determiners, are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Numbers and rates of subject bare nouns in MICLE trial material

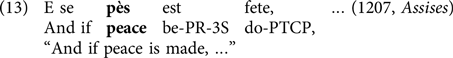

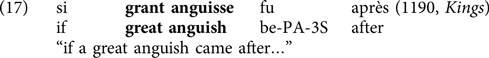

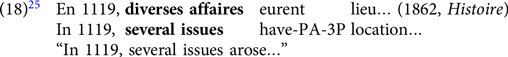

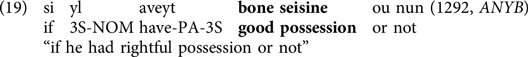

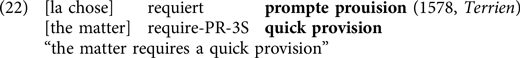

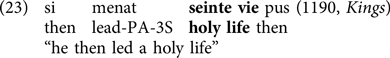

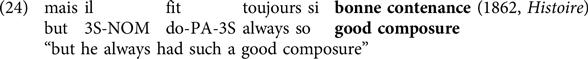

The identified proportions represent a decline. They go from over 4% at the beginning of the 13th century, to around 1% from the end of the 13th to the beginning of the 16th century, after which subject bare nouns go out of use. Example (13) provides one of the earliest instance of bare nouns in the corpus ; (14), one of the latest.

The intermediate period is further documented by the procedure style texts, see Table 5.

Table 5. Numbers and rates of subject bare nouns in MICLE procedure material

The proportions below 1% are in keeping with the trial figures, that are around 1%. Once again, we illustrate with one of the earliest (15) and latest (16) instances of bare nouns in the procedure material.

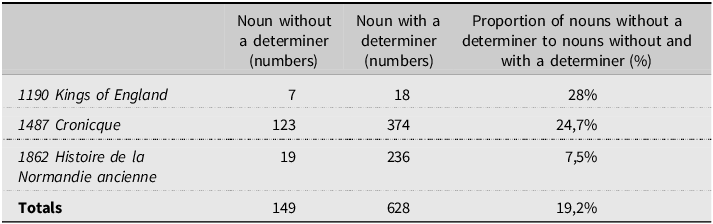

The overall evolution is confirmed by the figures of the Chroniques corpus (Table 6).

Table 6. Numbers and rates of subject bare nouns in Chronique material

The shape of the evolution of bare nouns in the three corpora is presented in the following graph (Fig. 1). The texts are tied to the nearest half-century (and to the 1400 point for 1425 procedure style; and averaging for the 1450 point the results of the 1431 and 1450 trials), the rates in percentages are rounded to the nearest point (except for the 1450 and the 1850 point, which would not have been represented had they not be rounded at 0.5 and 0.1% respectively).

It shows a use at around 5% in the earliest period, and a subsequent rate around 1% until the use disappears at the end of the 16th century.

Figure 1. Evolution of subject bare nouns in three sub-corpora.

4.2 Bare nouns in object function

The same quantitative analysis was performed for bare nouns in object position.

The numbers in the MICLE trial material corpus are presented below (Table 7).

Table 7. Numbers and rates of object bare nouns in MICLE trial material

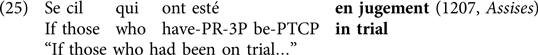

The trial material does not present the expected overall sharp decline, but rather a rise to around 11% in the 1430–1450 period, followed by a slow decrease. The impression of a rise is partly caused by the absence of bare noun objects in the first text, and a lower rate in the 1340 text than either the preceding or following text; as well as by the relatively high rates in the two 15th-century texts. Whether this latter observation is due to those particular texts, or to the period, can be established by looking at the same phenomenon in the procedure style corpus. The figures are as follows (Table 8):

Table 8. Numbers and rates of object bare nouns in the MICLE procedure material

They are more in keeping with the figures in the trial corpus, suggesting that the observed peak may be an effect of the 1431 and 1450 trials. Yet a more nuanced picture is provided by the Chroniques corpus, whose numbers are given in the next table (Table 9):

Table 9. Numbers and rates of object bare nouns in Chroniques material

The 15th century chronicle displays a higher rate than the earlier 1425 style, but lower than the two 15th century trials. This is shown by the following graph (Fig. 2), which provides a representation of object bare noun rates in the three corpora.

Figure 2. Evolution of object bare nouns in three sub-corpora.

Overall, the loss is one that goes from nearly 10% to 3%, with some variance in the period between 1430 and 1550. The development of bare nouns in the last investigated syntactic category is considered in the next section.

4.3 Bare nouns in oblique function

The annotation tool used separates objects from obliques. Obliques comprise a “nominal (noun, pronoun, noun phrase) functioning as a non-core (oblique) argument or adjunct. This means that it functionally corresponds to an adverbial attaching to a verb, adjective or other adverb”, according to the UD guidelines.Footnote 26 Note that except in the case of clitics, indirect objects are also annotated as obliques, an issue on which we come back later in this section.

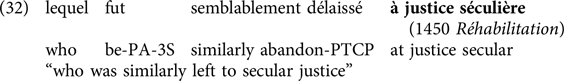

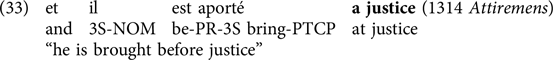

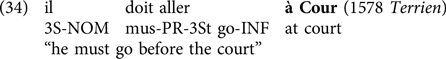

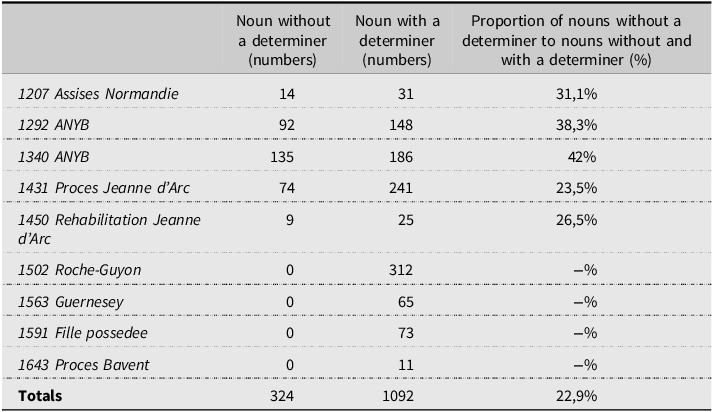

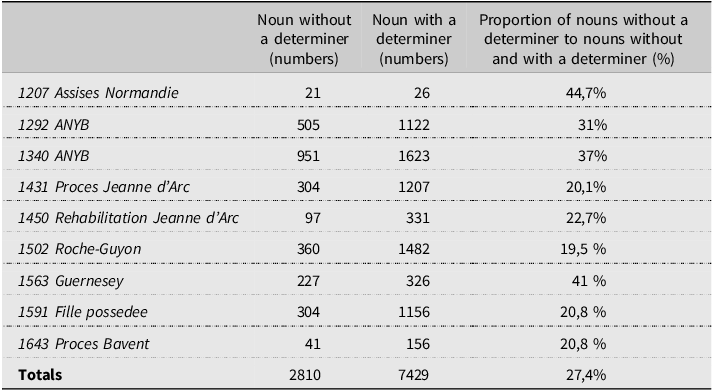

The nouns in oblique function without determiners and with determiners have been extracted and manually examined in each of the trial texts of the MICLE corpus for reliable figures to be established. The proportion of nouns without determiners to the sum of nouns with and without was then calculated. The results are presented in the table below (Table 10):

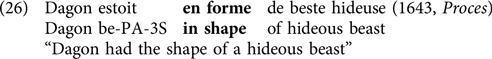

Table 10. Numbers and rates of oblique bare nouns in MICLE trial material

The change goes from 40% in the period to 1340, to 20% in the texts from 1430 (despite the unexpectedly high proportion in the Guernsey witch trials).

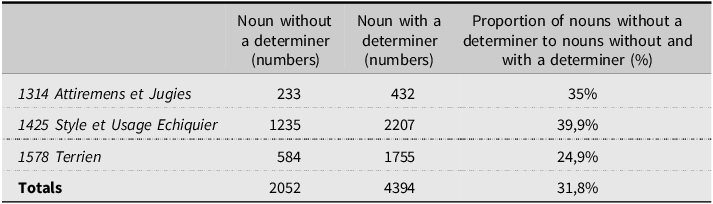

The pattern is more conservative in the procedure texts (Table 11):

Table 11. Numbers and rates of oblique bare nouns in MICLE procedure material

The situation in the chronicles is more in keeping with this trial corpora, although the initial period has slightly lower figures than expected and the later one slightly higher ones (Table 12):

Table 12. Numbers and rates of oblique bare nouns in Chroniques material

This is shown by the following graph (Fig. 3):

Figure 3. Evolution of oblique bare nouns in three sub-corpora.

The overall course of bare nouns in oblique function is one by which, despite the spike in the Guernsey text and the high proportions provided by procedure texts, the rates go from high-to-mid 30% until 1430, and fall to about 20%, a rate still found in the 19th century according to the last Chroniques text.

Despite the shortcoming of the annotations tools, we felt it would be good to be able to distinguish between indirect objects and adjuncts. A strategy was devised to achieve this. We first identified verbs used in conjunction with a clitic pronoun like lui, y, or en, which are correctly recognized as indirect objects (“iobj” in the UD tagset) by the HOPS parser. An oblique NP with these specific verbs can thus be safely assumed to be an indirect object, and especially when introduced with prepositions like à, de or en. We then proceeded to count the indirect objects with and without a determiner for each function, with results reported below (Tables 13–15, Fig. 4) :

Table 13. Numbers and rates of indirect objects bare nouns in MICLE trial material

Table 14. Numbers and rates of indirect objects bare nouns in MICLE procedure material

Table 15. Numbers and rates of indirect objects bare nouns in Chroniques material

Despite the possible shortcomings of our strategy to circumvent the lack of distinction between indirect object and adjuncts NP by the parsing tools, the numbers we assemble seem to confirm that bare nouns are more frequent in that function than direct objects, but less, overall, than obliques. Once again, some disparities can be noted in respect of text genre, with Chroniques exhibiting far fewer occurrences than the trial or procedure materials. The 15th century seems to be a crucial period, where occurrences become scarce. The residual examples come, for the most part, from set phrases (as in 36, “remettre à flot”, lit. “put back on stream”), the likes of which we still find in contemporary French.

Figure 4. Evolution of indirect object bare nouns in three sub-corpora.

Finally, with those numbers, we can better estimate the rate of adjuncts in the corpus, by subtracting the indirect objects from the sum of obliques (Tables 16–18, Fig. 5):

Table 16. Numbers and rates of adjunct bare nouns in MICLE trial material

Table 17. Numbers and rates of adjunct bare nouns in MICLE procedure material

Table 18. Numbers and rates of adjunct bare nouns in Chroniques material

Figure 5. Evolution of adjuncts bare nouns in three sub-corpora.

From the figure, we can see that oblique bare nouns are a grammatical option all through the history of French. The 15th century, however and once again, seems to be a turning point: rates stabilize around the 20% mark, and never go lower.

5. THE COURSE OF BARE NOUNS IN MEDIEVAL FRENCH

This research confirms that bare nouns loss is impacted by syntactic function. First, in subject position, bare nouns are used at around 5% in the earliest period, to be subsequently found at around 1%, and disappear at the beginning of the 16th century. Object bare nouns go from 10% to 3%, with variation between 12% and 5% in the period between 1430 and 1550. Finally, obliques decline from a rate of nearly 40% until 1430 to around the 20% that subsist in the final period. A closer inspection of obliques shows that adjuncts go from 45% to 20% of bare nouns, and indirect objects from 40% to nil, the latter presenting a more pronounced decline: variations between texts is expected to reflect the involvement of formulaic sequences.Footnote 27

There are some unexpectedly high rates for some texts, but little variance between text types, an indication that comparison of results from different sub-corpora can be useful in tracking change (Amatuzzi et al. Reference Amatuzzi, Wendy Ayres-Bennett, Schøsler and Skupien-Dekens2020). Again, the numbers provided by non-literary texts are lower than what is reported for literary material, because the former are presumably closer to the ongoing change, as they are not concerned with the stylistic and high register considerations found in the latter.

Syntactic function thus defines the order in which bare noun decline is occurring in the history of French as documented by these corpora. The order from subject to object to oblique (and to direct object to indirect object to adjuncts) is reminiscent of the generalization proposed by Keenan and Comrie (Reference Keenan and Comrie1977). In their work on the crosslinguistic organization of relative clause markers, they put forward an Accessibility Hierarchy.

This implicational map supposes that the functions to the left are more accessible than the function to the right of the scale. The more accessible functions are more likely to be represented by a specific relative marker in any language. There are more languages with a subject marker (such as French qui) than with a genitive one (such as one use of French dont), and more with genitive than with comparative (which is ungrammatical in French). A language with relative markers in a less accessible function will comprise markers with the more accessible functions. Accessibility has also been shown to predict frequency of markers in individual languages by acquisitional studies (see the overview by Lau and Tanaka Reference Lau and Tanaka2021). Larrivée (Reference Larrivée2020) documents that the frequency of French clitics is correlated to their position on the Hierarchy, and that subject clitics are more frequent than objects in spoken and written contemporary French, and objects more frequent than obliques. Regarding determiners, the Accessibility Hierarchy also helps make sense of their historical progression, and the correlative loss of bare nouns, since determiners are the most frequent in the most accessible positions at any one time, and the more accessible position see the earlier decline of bare nouns as compared to the less accessible ones.

As it set out to do, this article has provided extensive documentation on one factor correlative to the emergence of determiners. We now speculate on the question that arises that is why that should be. Why should the rate of nouns with a determiner be greater with more accessible functions? We could speculate that this relates to referentiality, that is the property of an expression of denoting an entity that exists in the common ground. Let us assume that in a language where both options are available, a noun with a determiner is more likely to be referential than the same noun without one, and that more referential nouns are found in more accessible positions, then we expect the more accessible positions to host more (common) nouns with determiners and fewer bare nouns.

The supposition that subjects host more referential nouns is supported by an early piece of work on English by Bock and Warren (Reference Bock and Warren1985). They showed that more referential nouns (which they call “imageable”) tend to be realized in higher functions on the Accessibility Hierarchy, and that the “more imageable” nouns occur most in subject position. Recent confirmation has been provided for one component of “imagibility” that is animacy by Thuilier et al. (Reference Thuilier, Grant, Crabbé and Abeillé2021) and Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Hartsuiker, Muylle, Slim and Zhang2022). This connection between referentiality of a noun and syntactic accessibility is of course exactly why more (definite) determiners would be found in more accessible function.Footnote 28

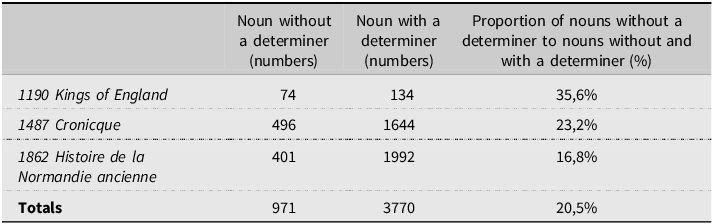

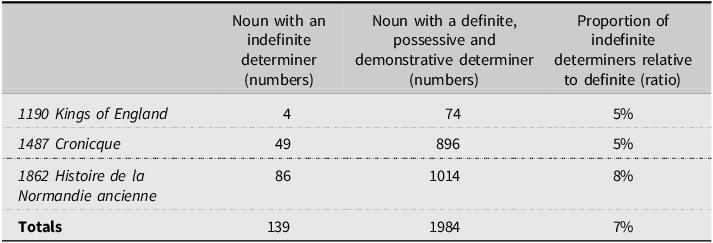

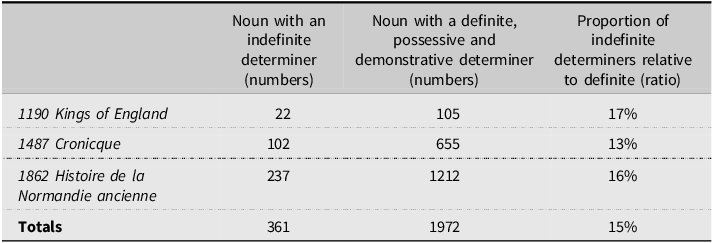

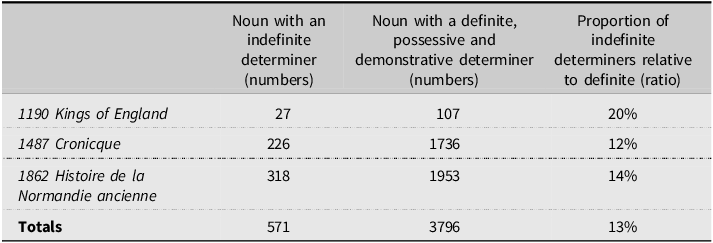

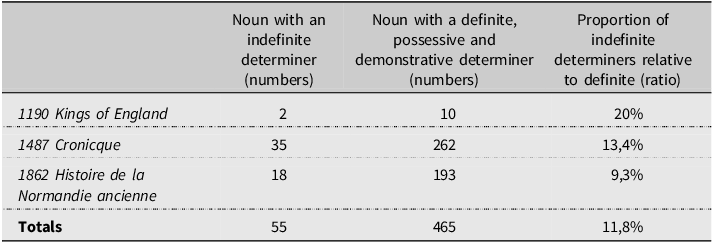

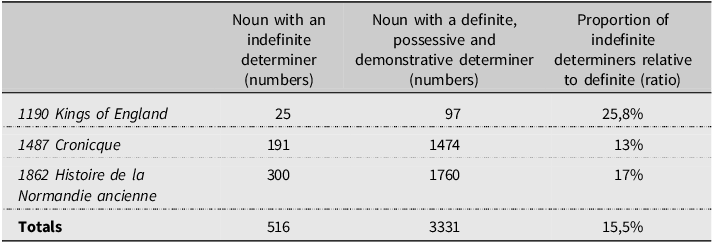

How could the supposed connection between referentiality and functions be supported from a diachronic point of view? A clue is provided by Simonenko and Carlier (Reference Simonenko and Carlier2020a); they note that subjects are “at least 2–3 times more likely than objects to occur with a definite, possessive or demonstrative determiner” (Reference Simonenko and Carlier2020a: 222). Assuming that definite, possessive and demonstrative determiners mark referentiality, and that NPs are more referential in more accessible function, we should then find a progression of these determiners in the more accessible functions through time. In other words, there should be more definite determiners in subject position than in object, and more in object than in oblique, at any period, and at all periods. This is what we sought to explore, using the Chroniques corpus. Extraction of indefinite determiners on the one hand and of definites, demonstratives and possessives on the other allowed the ratio of the latter to be calculated. We would expect the ratio of indefinites to definites to be lower with subjects than with objects, and with object than with obliques. The numbers for each function are provided below (Tables 19–21):

Table 19. Ratio of indefinite to definite determiners in subject position

Table 20. Ratio of indefinite to definite determiners in object position

Table 21. Ratio of indefinite to definite determiners in oblique position

Using the same strategy as before, rates were produced for indirect objects and adjuncts (Tables 22 and 23):

Table 22. Ratio of indefinite to definite determiners in indirect object position

Table 23. Ratio of indefinite to definite determiners in adjunct position

The data, which is in keeping with those of the other two corpora, confirms that subjects host fewer nouns with an indefinite determiner than objects; but it does not indicate that objects have fewer indefinites than obliques. Distinction between indirect objects and adjuncts is on par with the hypothesis, as the rates for adjuncts are higher than those for indirect objects, but indirect objects do not clearly evidence higher rates than objects. Note also that there is little progression for subject and object through time, and an actual decrease through time in the ratio of indefinite determiners with obliques. Clearly, more work is required around referentiality, syntactic function and determiner expression (or lack thereof). Where there is progression is in the proportion of definites, possessives and demonstratives as compared to all noun phrases, with and without determiner. For subjects, the proportions go from 78% (74/95) to 93% (896/1058) to 98% (1014/1040); and for obliques, from 46% (107/233) to 66% (1736/2637) and 72% (1953/2726). For indirect objects, proportions go from 29% (10/35) to 46% (262/569) to 45% (193/426); and for adjuncts, proportions go from 49% (97/198) to 71% (1474/2068) to 77% (1760/2300). For objects however, the proportion is stable, at around 80%. So, there is through time a growth in definite determiner use, by function, mirroring that of bare noun loss. The progress of definite determiners in more accessible functions would thus account for the loss of bare nouns along the Accessibility Hierarchy, under the assumptions presented and partially supported here by a preliminary investigation that more accessible functions host more referential NPs that have more definite determiners.Footnote 29

6. CONCLUSIONS

This article seeks to make sense of the evolution of bare nouns in the history of French. On the basis of extensive documentation, we show that the curve of decline of bare nouns is determined by function, confirming suggestions by Simonenko and Carlier (Reference Simonenko and Carlier2020a) and Carlier and Lamiroy (Reference Carlier and Lamiroy2018a; Reference Carlier and Lamiroy2018b). The loss of subject bare nouns around 1500, the decrease of object bare nouns to 3%, and the reduction of obliques to 20% follow the path drawn by the Accessibility Hierarchy. Established for the investigation of relative markers by Keenan and Comrie (Reference Keenan and Comrie1977), the Hierarchy proposes that subjects are more accessible than objects, and object more than obliques.Footnote 30

The question that arises is why accessible functions should encourage greater rates of use of determiners. The speculation that we have proposed is that more accessible functions are characterized by greater referentiality, and that referentiality is more likely to be marked by a definite determiner. The data examined evidence that definite determiners (inclusive of possessivesFootnote 31 and demonstratives) actually see their proportion of use increase through time, being greatest with subjects, then objects, and then obliques. Thus, independent evidence shows that subjects are more referential than objects than obliques, and thus lose more quickly bare nouns, which tend to be less referential. Correlation between definiteness and syntactic position was already explored in other languages, in Malagasy (Paul Reference Paul, Ghomeshi, Paul and Wiltschok2009) or in Dutch (Rullmann Reference Rullmann1989) for instance, and French seems to follow the same trend throughout its history.

Our study has shown that it pays to use calibrated corpora of non-fictional prose, and to compare data emerging from them. A baseline can thus be established to get closer to the effective change in the immediate competence of speakers. Outliers can be compared to results from other texts (or text types), to assess whether the figures they provide are representative of a trend in the language community, or whether they are down to individual texts or text types: the latter case seems to apply to the high levels of object bare nouns in the 1431 and 1450 trials, and to the high level of oblique bare nouns in procedure texts.

Suggestions for future research relate to method and replication. It would be nice to be able to separate indirect objects and adjuncts, which with the used parser are bunched together as obliques, although this article has proposed a strategy to do this that may possibly be generalized. Equally desirable would be to have access to more reliably annotated, non-fictional prose through time. Also, whether the pattern identified here applies to other languages, as we would expect, is certainly worthy of examination. It is to be hoped that the patterns documented here can be tested by future studies. Finally, the great question that needs to be probed is why determiners emerge at all, and under what conditions they become compulsory in some languages, but not in others.