1. Introduction

In the development of hypersonic vehicles, to calculate accurately the drag and heat flux is a task of the first priority, which requires an accurate prediction of the laminar–turbulent transition. For high-altitude flight conditions, transition is often triggered by a natural route, for which four phases, including the receptivity, linear instability, nonlinear resonance and turbulence, appear in sequence. For supersonic or hypersonic boundary layers, there may exist more than one discrete instability mode, which are referred to as the Mack first, second, ![]() $\ldots$ modes, according to the ascending order of their frequencies (Mack Reference Mack1987). It was revealed by the asymptotic analysis that only the Mack first mode with

$\ldots$ modes, according to the ascending order of their frequencies (Mack Reference Mack1987). It was revealed by the asymptotic analysis that only the Mack first mode with ![]() $\varTheta > \tan ^{-1} \sqrt {M^2-1}$ (where

$\varTheta > \tan ^{-1} \sqrt {M^2-1}$ (where ![]() $\varTheta$ and

$\varTheta$ and ![]() $M$ denote the wave angle and Mach number, respectively) has the viscous nature (Smith Reference Smith1989; Liu, Dong & Wu Reference Liu, Dong and Wu2020), while the quasi-two-dimensional Mack first and all the higher-order modes are inviscid (Cowley & Hall Reference Cowley and Hall1990; Smith & Brown Reference Smith and Brown1990; Dong, Liu & Wu Reference Dong, Liu and Wu2020; Zhao, He & Dong Reference Zhao, He and Dong2023). Usually, the Mack second mode appears when the Mach number is approximately over 4, and its growth rate peaks when it is planar (two-dimensional). In contrast, the Mack first mode appears in all supersonic boundary layers, which is more unstable when it is oblique (three-dimensional). The linear evolution of these modes was confirmed by quite a few numerical works, such as Fedorov (Reference Fedorov2011) and Zhong & Wang (Reference Zhong and Wang2012). When the unstable modes are accumulated to finite amplitudes, the nonlinear interaction among different Fourier components becomes the leading-order impact, showing three major nonlinear regimes, including the oblique-mode breakdown (Thumm Reference Thumm1991; Fasel, Thumm & Bestek Reference Fasel, Thumm and Bestek1993; Chang & Malik Reference Chang and Malik1994; Leib & Lee Reference Leib and Lee1995; Mayer, Von Terzi & Fasel Reference Mayer, Von Terzi and Fasel2011a; Mayer, Wernz & Fasel Reference Mayer, Wernz and Fasel2011b), the subharmonic resonance (Saric Reference Saric1984; Herbert Reference Herbert1988) and the fundamental resonance (Sivasubramanian & Fasel Reference Sivasubramanian and Fasel2015; Hader & FaselReference Hader and Fasel2019).

$M$ denote the wave angle and Mach number, respectively) has the viscous nature (Smith Reference Smith1989; Liu, Dong & Wu Reference Liu, Dong and Wu2020), while the quasi-two-dimensional Mack first and all the higher-order modes are inviscid (Cowley & Hall Reference Cowley and Hall1990; Smith & Brown Reference Smith and Brown1990; Dong, Liu & Wu Reference Dong, Liu and Wu2020; Zhao, He & Dong Reference Zhao, He and Dong2023). Usually, the Mack second mode appears when the Mach number is approximately over 4, and its growth rate peaks when it is planar (two-dimensional). In contrast, the Mack first mode appears in all supersonic boundary layers, which is more unstable when it is oblique (three-dimensional). The linear evolution of these modes was confirmed by quite a few numerical works, such as Fedorov (Reference Fedorov2011) and Zhong & Wang (Reference Zhong and Wang2012). When the unstable modes are accumulated to finite amplitudes, the nonlinear interaction among different Fourier components becomes the leading-order impact, showing three major nonlinear regimes, including the oblique-mode breakdown (Thumm Reference Thumm1991; Fasel, Thumm & Bestek Reference Fasel, Thumm and Bestek1993; Chang & Malik Reference Chang and Malik1994; Leib & Lee Reference Leib and Lee1995; Mayer, Von Terzi & Fasel Reference Mayer, Von Terzi and Fasel2011a; Mayer, Wernz & Fasel Reference Mayer, Wernz and Fasel2011b), the subharmonic resonance (Saric Reference Saric1984; Herbert Reference Herbert1988) and the fundamental resonance (Sivasubramanian & Fasel Reference Sivasubramanian and Fasel2015; Hader & FaselReference Hader and Fasel2019).

The oblique-mode breakdown appears when the dominant perturbations in the early nonlinear phase are a pair of three-dimensional (3-D) travelling waves with the same frequency but opposite spanwsie wavenumbers, as sketched in figure 1(a). Such a regime was pioneered by Thumm (Reference Thumm1991) and Fasel et al. (Reference Fasel, Thumm and Bestek1993) using the direct numerical simulation (DNS) approach and subsequently studied by Chang & Malik (Reference Chang and Malik1994) using the nonlinear parabolised stability equations (NPSEs) approach. They all found that the growth rates of the second-order harmonics and the stationary streak mode are equal to twice those of the oblique modes, because they are driven by the self or mutual interaction of the oblique modes. Particularly, the streak mode shows a much greater amplitude than the second-order harmonics. Such a phenomenon was recently explained by Song, Dong & Zhao (Reference Song, Dong and Zhao2022) using the weakly nonlinear analysis based on the large-Reynolds-number asymptotic technique. Considering the growth rate of the travelling Mack mode to be much smaller than its wavenumber, the transverse and lateral perturbation velocities of the streak mode, showing a roll structure, are primarily amplified due to the mutual interaction of the oblique modes, but its streamwise velocity perturbation undergoes a further amplification due to the lift-up mechanism induced by the roll structure. For a low-Mach-number supersonic boundary layer, the most unstable linear perturbation is usually the oblique first mode, which ensures the dominant perturbation in the early nonlinear phase to be three-dimensional, indicating that the oblique-mode breakdown regime is likely to be triggered in this configuration.

Figure 1. Characteristic parameters in the frequency-spanwise-wavenumber space: (a) oblique-mode breakdown regime; (b) subharmonic resonance regime; (c) fundamental resonance regime. Here, ![]() $\omega _0$ and

$\omega _0$ and ![]() $\beta _0$ denote the fundamental frequency and spanwise wavenumber, respectively. This sketch is a modified version of figure 10 of Hader & Fasel (Reference Hader and Fasel2019).

$\beta _0$ denote the fundamental frequency and spanwise wavenumber, respectively. This sketch is a modified version of figure 10 of Hader & Fasel (Reference Hader and Fasel2019).

The subharmonic resonance (SR) appears when the dominant perturbation in the early nonlinear phase is planar, or two-dimensional (2-D), and the frequency of the most amplified 3-D perturbations is half of that of the 2-D mode; see the schematic in figure 1(b). Such a regime usually appears in a subsonic or an incompressible boundary layer, as observed numerically (Herbert Reference Herbert1988) and experimentally (Saric Reference Saric1984), and the rapid amplification of the 3-D modes is attributed to the secondary instability (SI) based on the Floquet theory (Herbert Reference Herbert1988). For supersonic boundary layers, Kosinov, Maslov & Shevelkov (Reference Kosinov, Maslov and Shevelkov1990), Kosinov et al. (Reference Kosinov, Semionov, Shevel'kov and Zinin1994) and Kosinov & Tumin (Reference Kosinov and Tumin1996) reported a generalised subharmonic regime, for which the dominant perturbation is a 3-D Mack first mode, and the two most promoted SI modes are subharmonic in frequency. This scenario was later confirmed by the numerical simulations of Mayer et al.(Reference Mayer, Wernz and Fasel2011b).

For a hypersonic boundary layer, the 2-D Mack second mode is the most linearly amplified perturbation, which could be the dominant perturbation in the early nonlinear phase. Using the DNS approach, the most amplified 3-D modes are found to be those with the same frequency as the 2-D second mode (Sivasubramanian & Fasel Reference Sivasubramanian and Fasel2015; Hader & Fasel Reference Hader and Fasel2019), which was also confirmed by the secondary instability analysis (SIA) of Chen, Zhu & Lee (Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017). This scenario is referred to as the fundamental resonance (FR) and a schematic for the FR in the spectrum space is shown in figure 1(c). Based on the critical-layer theory (Wu Reference Wu2004; Zhang & Wu Reference Zhang and Wu2022), Wu, Luo & Yu (Reference Wu, Luo and Yu2016) deduced the evolution equations for the oblique modes and claimed that the 2-D mode acts as a catalyst to promote the growth of the oblique modes. The 2-D dominant mode and the small-amplitude oblique modes are found to be phase-locked. Actually, the SI modes include both the 3-D travelling waves and the stationary streak mode, and the amplitude of the latter was found to be much greater than those of the former (Brad et al. Reference Brad, Thomas, Dennis, Chou, Peter, Casper, Laura, Schneider and Johnson2009; Chou et al. Reference Chou, Ward, Letterman, Schneider, Luersen and Borg2011; Sivasubramanian & Fasel Reference Sivasubramanian and Fasel2015; Chynoweth et al. Reference Chynoweth, Schneider, Hader, Fasel, Batista, Kuehl, Juliano and Wheaton2019; Hader & Fasel Reference Hader and Fasel2019). However, the latter phenomenon so far is not well explained from the dynamicviewpoint.

For convenience of illustration, each Fourier component with a frequency ![]() $m\omega _0$ and a spanwise wavenumber

$m\omega _0$ and a spanwise wavenumber ![]() $n\beta _0$ is denoted by

$n\beta _0$ is denoted by ![]() $(m,n)$, where

$(m,n)$, where ![]() $\omega _0$ and

$\omega _0$ and ![]() $\beta _0$ are the fundamental frequency and spanwise wavenumber, respectively. It is seen that in both the SR and FR regimes, the dominant perturbation in the early nonlinear phase is 2-D. If we choose the frequency of the 2-D mode to be the fundamental frequency

$\beta _0$ are the fundamental frequency and spanwise wavenumber, respectively. It is seen that in both the SR and FR regimes, the dominant perturbation in the early nonlinear phase is 2-D. If we choose the frequency of the 2-D mode to be the fundamental frequency ![]() $\omega _0$, then the 2-D fundamental mode is denoted by

$\omega _0$, then the 2-D fundamental mode is denoted by ![]() $(1,0)$. For the SR, the most unstable 3-D travelling waves are components

$(1,0)$. For the SR, the most unstable 3-D travelling waves are components ![]() $(1/2,n)$, where

$(1/2,n)$, where ![]() $n$ is an integer to represent the spanwise wavenumber. The components

$n$ is an integer to represent the spanwise wavenumber. The components ![]() $(1,0)$,

$(1,0)$, ![]() $(1/2,n)$ and

$(1/2,n)$ and ![]() $(1/2,-n)$ with a non-zero

$(1/2,-n)$ with a non-zero ![]() $n$ form a triad resonance system, for which the mutual interaction of any two components seeds for the growth of the third one. When the dominant 2-D mode

$n$ form a triad resonance system, for which the mutual interaction of any two components seeds for the growth of the third one. When the dominant 2-D mode ![]() $(1,0)$ reaches a nonlinear saturation phase, the oblique modes

$(1,0)$ reaches a nonlinear saturation phase, the oblique modes ![]() $(1/2,n)$ and

$(1/2,n)$ and ![]() $(1/2,-n)$ could amplify with a greater rate, interpreted as an SI regime. As the oblique pair

$(1/2,-n)$ could amplify with a greater rate, interpreted as an SI regime. As the oblique pair ![]() $(1/2,\pm n)$ reach finite amplitudes, their interaction could also drive a streak mode

$(1/2,\pm n)$ reach finite amplitudes, their interaction could also drive a streak mode ![]() $(0,2n)$, similar to the oblique-mode breakdown regime. However, for the FR, the most unstable 3-D travelling waves are

$(0,2n)$, similar to the oblique-mode breakdown regime. However, for the FR, the most unstable 3-D travelling waves are ![]() $(1,n)$ with

$(1,n)$ with ![]() $n$ being an integer, and the Fourier components

$n$ being an integer, and the Fourier components ![]() $(1,0)$,

$(1,0)$, ![]() $(1, n)$ and

$(1, n)$ and ![]() $(1,-n)$ with a non-zero

$(1,-n)$ with a non-zero ![]() $n$ do not form a triad resonance system. Although SI analyses have confirmed the rapid amplification of

$n$ do not form a triad resonance system. Although SI analyses have confirmed the rapid amplification of ![]() $(1,\pm n)$ in the nonlinear phase (Sivasubramanian & Fasel Reference Sivasubramanian and Fasel2015; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017; Hader & Fasel Reference Hader and Fasel2019), the energy transfer among different Fourier components due to their nonlinear interaction is far beyond obvious. Actually, the SI modes include a set of oblique modes with the same frequency

$(1,\pm n)$ in the nonlinear phase (Sivasubramanian & Fasel Reference Sivasubramanian and Fasel2015; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017; Hader & Fasel Reference Hader and Fasel2019), the energy transfer among different Fourier components due to their nonlinear interaction is far beyond obvious. Actually, the SI modes include a set of oblique modes with the same frequency ![]() $(1,n)$ and stationary streak modes

$(1,n)$ and stationary streak modes ![]() $(0,n)$, and the Fourier components

$(0,n)$, and the Fourier components ![]() $(1,0)$,

$(1,0)$, ![]() $(1,n)$ and

$(1,n)$ and ![]() $(0,n)$ could form a triad resonance system. Inclusion of the streak mode in the triad resonance determines the key role of the streak mode in the SI process of the FR, which is in contrast to the SR. Unfortunately, such a dynamic mechanism has not been formulated theoretically, especially in the hypersonic boundary layers, which is the main task of the present work.

$(0,n)$ could form a triad resonance system. Inclusion of the streak mode in the triad resonance determines the key role of the streak mode in the SI process of the FR, which is in contrast to the SR. Unfortunately, such a dynamic mechanism has not been formulated theoretically, especially in the hypersonic boundary layers, which is the main task of the present work.

The rest part of this paper is structured as follows. In § 2, we introduce the physical model and the numerical treatment (NPSE approach) for the FR, and the NPSE calculations showing the crucial role of the streak mode are demonstrated in § 3. In § 4, we develop an asymptotic theory to describe the dynamic mechanism of the FR, whose accuracy is confirmed by the NPSE calculations for moderate Reynolds numbers in § 5 and by SI analysis for sufficiently high Reynolds numbers in § 6. The concluding remarks are present in § 7.

2. Physical model and governing equations

2.1. Physical model

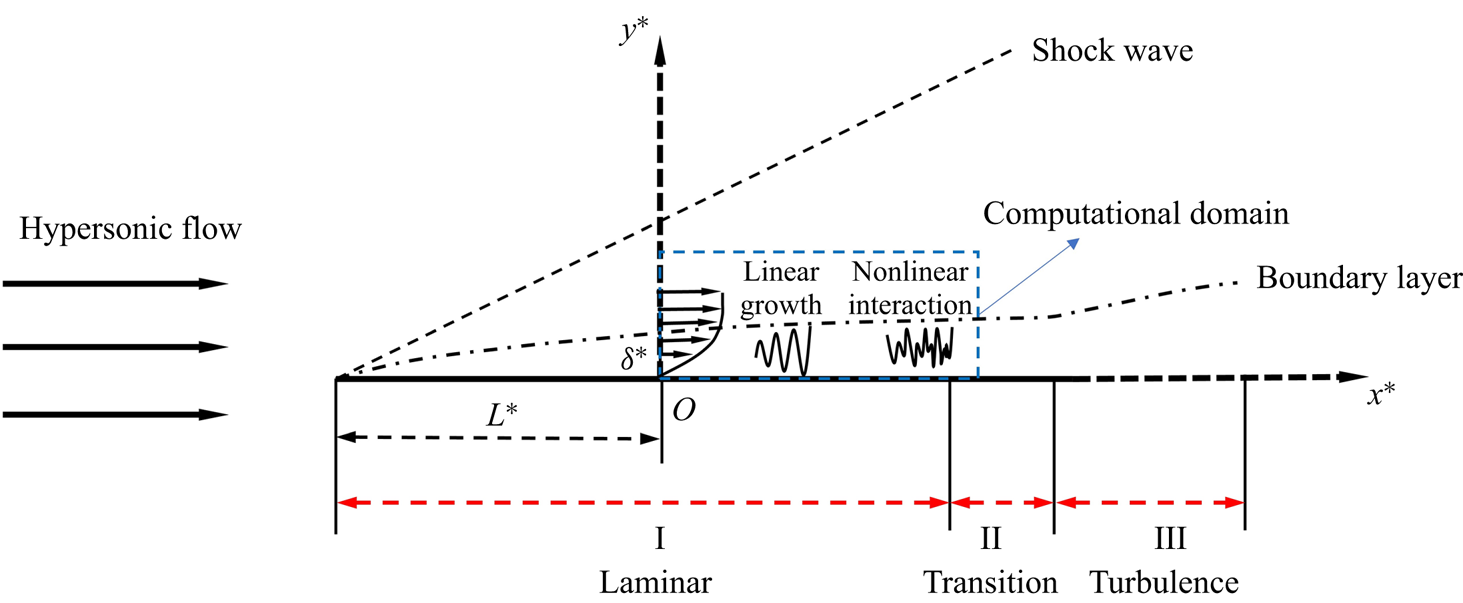

The physical model to be studied is a flat plate inserted into a perfect-gas hypersonic stream with zero angle of attack, as sketched in figure 2. The plate is assumed to be infinitely thin such that a rather weak oblique shock forms from its leading edge, and the flow quantities behind the shock are rather close to those of the oncoming stream. A viscous boundary layer forms in the close neighbourhood of the wall.

Figure 2. Sketch of the physical model.

We study the evolution of a set of Mack instability modes in a selected computational domain, whose inlet boundary is located at a distance ![]() $L^*$ downstream of the leading edge, where the Mack modes are already unstable. The inflow perturbations consist of a dominant 2-D Mack mode and a pair of small 3-D Mack modes with the same frequency. The problem is described by the Cartesian coordinate

$L^*$ downstream of the leading edge, where the Mack modes are already unstable. The inflow perturbations consist of a dominant 2-D Mack mode and a pair of small 3-D Mack modes with the same frequency. The problem is described by the Cartesian coordinate ![]() $\boldsymbol {x}^*=(x^*,y^*,z^*)$ with its origin

$\boldsymbol {x}^*=(x^*,y^*,z^*)$ with its origin ![]() $O$ at the inlet of the computational domain. The reference length is selected to be the boundary-layer characteristic thickness at the origin

$O$ at the inlet of the computational domain. The reference length is selected to be the boundary-layer characteristic thickness at the origin ![]() $\delta ^*=\sqrt {\nu ^{*}_\infty L^{*}/U^{*}_\infty }$, where

$\delta ^*=\sqrt {\nu ^{*}_\infty L^{*}/U^{*}_\infty }$, where ![]() $U_\infty ^*$ and

$U_\infty ^*$ and ![]() $\nu ^{*}_\infty$ denote the velocity and the kinematic viscosity of the oncoming flow. The dimensionless coordinate and time are expressed as

$\nu ^{*}_\infty$ denote the velocity and the kinematic viscosity of the oncoming flow. The dimensionless coordinate and time are expressed as

In what follows, the superscript ![]() $*$ denotes the dimensional quantities. The velocity field

$*$ denotes the dimensional quantities. The velocity field ![]() $\boldsymbol {u}=(u,v,w)$, density

$\boldsymbol {u}=(u,v,w)$, density ![]() $\rho$, temperature

$\rho$, temperature ![]() $T$, pressure

$T$, pressure ![]() $p$ are normalised by

$p$ are normalised by ![]() $U^{*}_\infty$,

$U^{*}_\infty$, ![]() $\rho ^{*}_\infty$,

$\rho ^{*}_\infty$, ![]() $T^{*}_\infty$,

$T^{*}_\infty$, ![]() $\rho ^{*}_\infty U^{{*}2}_\infty$, respectively, where the subscript

$\rho ^{*}_\infty U^{{*}2}_\infty$, respectively, where the subscript ![]() $\infty$ denotes the quantities at the oncoming stream. For unsteady perturbations, the frequency

$\infty$ denotes the quantities at the oncoming stream. For unsteady perturbations, the frequency ![]() $\omega$, streamwise wavenumber

$\omega$, streamwise wavenumber ![]() $\alpha$ and spanwise wavenumber

$\alpha$ and spanwise wavenumber ![]() $\beta$ are normalised as

$\beta$ are normalised as

The flow field is governed by two dimensionless parameters, the Reynolds number ![]() $R=U^{*}_\infty \delta ^*/\nu ^{*}_\infty$ and the Mach number

$R=U^{*}_\infty \delta ^*/\nu ^{*}_\infty$ and the Mach number ![]() $M=U_\infty ^*/a_\infty ^*$, with

$M=U_\infty ^*/a_\infty ^*$, with ![]() $a_\infty ^*$ denoting the sound speed of the oncoming stream.

$a_\infty ^*$ denoting the sound speed of the oncoming stream.

2.2. Governing equations

The dimensionless governing equations are

where ![]() ${\boldsymbol {S}} = {{[ {\boldsymbol {\nabla } {\boldsymbol {u}} + {{( {\boldsymbol {\nabla } {\boldsymbol {u}}} )}^{\rm T}}} ]}/ 2}$ is the strain-rate tensor,

${\boldsymbol {S}} = {{[ {\boldsymbol {\nabla } {\boldsymbol {u}} + {{( {\boldsymbol {\nabla } {\boldsymbol {u}}} )}^{\rm T}}} ]}/ 2}$ is the strain-rate tensor, ![]() $\mu$ is the dynamic viscosity satisfying the Sutherland law (

$\mu$ is the dynamic viscosity satisfying the Sutherland law (![]() $\mu =(1+ { C})T^{{3}/{2}}/(T+ { C})$ with

$\mu =(1+ { C})T^{{3}/{2}}/(T+ { C})$ with ![]() ${C}=110.4K/{T_\infty ^{*}}$),

${C}=110.4K/{T_\infty ^{*}}$), ![]() $Pr$ is the Prandtl number,

$Pr$ is the Prandtl number, ![]() $\gamma$ is the ratio of the specific heats and

$\gamma$ is the ratio of the specific heats and ![]() ${{\rm D}}/{{\rm D}t} = {\partial }/{\partial t} + \boldsymbol {u} \boldsymbol {\cdot } \boldsymbol {\nabla }$ denotes the material derivative. In this paper, we take

${{\rm D}}/{{\rm D}t} = {\partial }/{\partial t} + \boldsymbol {u} \boldsymbol {\cdot } \boldsymbol {\nabla }$ denotes the material derivative. In this paper, we take ![]() $Pr=0.72$ and

$Pr=0.72$ and ![]() $\gamma =1.4$.

$\gamma =1.4$.

The no-slip, non-penetration and isothermal boundary conditions are applied at the wall,

where ![]() $T_w$ is the dimensionless wall temperature. In the far field, all the perturbations damp exponentially (the radiating mode as that of Chuvakhov & Fedorov (Reference Chuvakhov and Fedorov2016) is not considered here) and the upper boundary conditions read

$T_w$ is the dimensionless wall temperature. In the far field, all the perturbations damp exponentially (the radiating mode as that of Chuvakhov & Fedorov (Reference Chuvakhov and Fedorov2016) is not considered here) and the upper boundary conditions read

2.3. Perturbation field

The instantaneous flow field ![]() $\phi \equiv (\rho,u,v,w, T)$ can be decomposed into a steady base flow

$\phi \equiv (\rho,u,v,w, T)$ can be decomposed into a steady base flow ![]() $\varPhi _B$ and an unsteady perturbation

$\varPhi _B$ and an unsteady perturbation ![]() $\tilde {\phi }$,

$\tilde {\phi }$,

where ![]() $\varPhi _B=(1/T_B,U_B,V_B,0,T_B)$ is the compressible Blasius solution. Substituting (2.6) into (2.3), and subtracting the base flow out, we obtain the nonlinear equations governing the perturbations,

$\varPhi _B=(1/T_B,U_B,V_B,0,T_B)$ is the compressible Blasius solution. Substituting (2.6) into (2.3), and subtracting the base flow out, we obtain the nonlinear equations governing the perturbations,

$$\begin{gather} {\boldsymbol { G }}\frac{{\partial \tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial t}} + {\boldsymbol{A}}\frac{{\partial \tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial x}} + {\boldsymbol{B}}\frac{{\partial \tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial y}} + {\boldsymbol{C}}\frac{{\partial \tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial z }} + {\boldsymbol{D}}\tilde{\phi} + {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xx}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial {x^2}}} + {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{yy}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial {y^2}}} \nonumber\\ +\, {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{z z }}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial {z ^2}}} + {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xy}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial x\partial y}} + {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xz }}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial x\partial z }} + {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{yz }}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial y\partial z }} = \boldsymbol{F}, \end{gather}$$

$$\begin{gather} {\boldsymbol { G }}\frac{{\partial \tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial t}} + {\boldsymbol{A}}\frac{{\partial \tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial x}} + {\boldsymbol{B}}\frac{{\partial \tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial y}} + {\boldsymbol{C}}\frac{{\partial \tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial z }} + {\boldsymbol{D}}\tilde{\phi} + {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xx}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial {x^2}}} + {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{yy}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial {y^2}}} \nonumber\\ +\, {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{z z }}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial {z ^2}}} + {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xy}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial x\partial y}} + {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xz }}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial x\partial z }} + {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{yz }}\frac{{{\partial ^2}\tilde{\phi} }}{{\partial y\partial z }} = \boldsymbol{F}, \end{gather}$$

where the coefficient matrices ![]() $\boldsymbol {G}$,

$\boldsymbol {G}$, ![]() $\boldsymbol {A}$,

$\boldsymbol {A}$, ![]() $\boldsymbol {B}$,

$\boldsymbol {B}$, ![]() $\boldsymbol {C}$,

$\boldsymbol {C}$, ![]() $\boldsymbol {D}$,

$\boldsymbol {D}$, ![]() ${\boldsymbol {V}}_{xx}$,

${\boldsymbol {V}}_{xx}$, ![]() ${\boldsymbol {V}}_{yy}$,

${\boldsymbol {V}}_{yy}$, ![]() ${\boldsymbol {V}}_{z z}$,

${\boldsymbol {V}}_{z z}$, ![]() ${\boldsymbol {V}}_{xy}$,

${\boldsymbol {V}}_{xy}$, ![]() ${\boldsymbol {V}}_{yz}$ and

${\boldsymbol {V}}_{yz}$ and ![]() ${\boldsymbol {V}}_{x z}$ and the nonlinear forcing

${\boldsymbol {V}}_{x z}$ and the nonlinear forcing ![]() $\boldsymbol {F}$ can be found in Appendix A. The pressure perturbation

$\boldsymbol {F}$ can be found in Appendix A. The pressure perturbation ![]() $\tilde {p}$ has been eliminated by the equation of the state (2.3d).

$\tilde {p}$ has been eliminated by the equation of the state (2.3d).

In this paper, we particularly focus on the FR regime, therefore, the introduced perturbations ![]() $\tilde {\phi }$ at the inlet of the computational domain should include a 2-D Mack second mode with a frequency

$\tilde {\phi }$ at the inlet of the computational domain should include a 2-D Mack second mode with a frequency ![]() $\omega _0$ and a pair of 3-D Mack second modes with the same frequency

$\omega _0$ and a pair of 3-D Mack second modes with the same frequency ![]() $\omega _0$ but opposite spanwise wavenumbers

$\omega _0$ but opposite spanwise wavenumbers ![]() $\pm \beta _0$, where

$\pm \beta _0$, where ![]() $\omega _0$ and

$\omega _0$ and ![]() $\beta _0$ are referred to as the fundamental frequency and fundamental spanwise wavenumber, respectively. For convenience, we use

$\beta _0$ are referred to as the fundamental frequency and fundamental spanwise wavenumber, respectively. For convenience, we use ![]() $(m,n)$ to denote a perturbation with a frequency

$(m,n)$ to denote a perturbation with a frequency ![]() $m\omega _0$ and a spanwise wavenumber

$m\omega _0$ and a spanwise wavenumber ![]() $n\beta _0$. Thus, the three introduced perturbations are denoted by

$n\beta _0$. Thus, the three introduced perturbations are denoted by ![]() $(1,0)$,

$(1,0)$, ![]() $(1,1)$ and

$(1,1)$ and ![]() $(1,-1)$, respectively. The inflow perturbation can be expressed as

$(1,-1)$, respectively. The inflow perturbation can be expressed as

$$\begin{align} \tilde{\phi}(0,y,z,t) &=\epsilon_{10}\hat \phi_{10}(\kern0.7pt y)\exp(-{\rm i}\omega_0 t)+\epsilon_{11}\hat \phi_{11}(\kern0.7pt y)\exp[{\rm i}(\beta_0z-\omega_0 t)] \nonumber\\ &\quad +\epsilon_{1-1}\hat \phi_{1-1}(\kern0.7pt y)\exp[{\rm i}(-\beta_0z-\omega_0t)]+ \text{c.c.}, \end{align}$$

$$\begin{align} \tilde{\phi}(0,y,z,t) &=\epsilon_{10}\hat \phi_{10}(\kern0.7pt y)\exp(-{\rm i}\omega_0 t)+\epsilon_{11}\hat \phi_{11}(\kern0.7pt y)\exp[{\rm i}(\beta_0z-\omega_0 t)] \nonumber\\ &\quad +\epsilon_{1-1}\hat \phi_{1-1}(\kern0.7pt y)\exp[{\rm i}(-\beta_0z-\omega_0t)]+ \text{c.c.}, \end{align}$$

where ![]() $\epsilon _{mn}$ measures the initial amplitude of the introduced perturbation

$\epsilon _{mn}$ measures the initial amplitude of the introduced perturbation ![]() $(m,n)$,

$(m,n)$, ![]() $\hat {\phi }_{mn}$ denotes the perturbation profile for the

$\hat {\phi }_{mn}$ denotes the perturbation profile for the ![]() $(m,n)$ component,

$(m,n)$ component, ![]() $\text {c.c.}$ denotes the complex conjugation and

$\text {c.c.}$ denotes the complex conjugation and ![]() $\text {i} \equiv \sqrt {-1}$. For a hypersonic boundary layer, the 2-D second mode is usually more unstable, and the amplitude of mode

$\text {i} \equiv \sqrt {-1}$. For a hypersonic boundary layer, the 2-D second mode is usually more unstable, and the amplitude of mode ![]() $(1,0)$ should be much greater than modes

$(1,0)$ should be much greater than modes ![]() $(1,\pm 1)$ due to the historical accumulative effect. Thus, the amplitude of the introduced 2-D mode

$(1,\pm 1)$ due to the historical accumulative effect. Thus, the amplitude of the introduced 2-D mode ![]() $\epsilon _{10}$ is taken to be much greater than those of the 3-D modes

$\epsilon _{10}$ is taken to be much greater than those of the 3-D modes ![]() $\epsilon _{11}$ and

$\epsilon _{11}$ and ![]() $\epsilon _{1-1}$. Also, the linear growth rates of the two oblique modes are the same, and so we let

$\epsilon _{1-1}$. Also, the linear growth rates of the two oblique modes are the same, and so we let ![]() $\epsilon _{11}=\epsilon _{1-1}$. Note that in reality, the spanwise wavenumbers of the oblique modes may be not exactly opposite and their amplitudes may be different, but our selection is still a good demonstration to reveal their resonance mechanism.

$\epsilon _{11}=\epsilon _{1-1}$. Note that in reality, the spanwise wavenumbers of the oblique modes may be not exactly opposite and their amplitudes may be different, but our selection is still a good demonstration to reveal their resonance mechanism.

2.3.1. Linear stability theory (LST)

The perturbation profile ![]() $\hat \phi$ for each Fourier mode of the inflow perturbation is obtained by the linear stability theory (LST). Introducing the parallel-flow assumption, the perturbation with a frequency

$\hat \phi$ for each Fourier mode of the inflow perturbation is obtained by the linear stability theory (LST). Introducing the parallel-flow assumption, the perturbation with a frequency ![]() $\omega$, a streamwise wavenumber

$\omega$, a streamwise wavenumber ![]() $\alpha$ and a spanwise wavenumber

$\alpha$ and a spanwise wavenumber ![]() $\beta$ is expressed in terms of a travelling-wave form,

$\beta$ is expressed in terms of a travelling-wave form,

where ![]() $\epsilon _L \ll 1$ measures its amplitude. Substituting (2.9) into the system (2.7) with

$\epsilon _L \ll 1$ measures its amplitude. Substituting (2.9) into the system (2.7) with ![]() $O(\epsilon _L^{2})$ terms neglected, we obtain the compressible Orr–Sommerfeld (O-S) equations,

$O(\epsilon _L^{2})$ terms neglected, we obtain the compressible Orr–Sommerfeld (O-S) equations,

where

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{gathered} {\boldsymbol{\tilde{B}}} = {\boldsymbol{B}} + {\rm{i}}\alpha {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xy}} + {\rm{i}}\beta{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{yz }},\\ {\boldsymbol{\tilde{D}}} ={-} {\rm{i}}\omega {\boldsymbol{G}} + {\rm{i}}\alpha {\boldsymbol{A}} + {\rm{i}}\beta{\boldsymbol{C}} + {\boldsymbol{D}} - {\alpha ^2}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xx}} - {\beta^2}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{zz }} - \alpha \beta{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xz }}. \end{gathered} \right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{gathered} {\boldsymbol{\tilde{B}}} = {\boldsymbol{B}} + {\rm{i}}\alpha {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xy}} + {\rm{i}}\beta{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{yz }},\\ {\boldsymbol{\tilde{D}}} ={-} {\rm{i}}\omega {\boldsymbol{G}} + {\rm{i}}\alpha {\boldsymbol{A}} + {\rm{i}}\beta{\boldsymbol{C}} + {\boldsymbol{D}} - {\alpha ^2}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xx}} - {\beta^2}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{zz }} - \alpha \beta{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xz }}. \end{gathered} \right\} \end{equation}Introducing the homogeneous boundary conditions,

we arrive at an eigenvalue problem. For the spatial mode, ![]() $\omega$ and

$\omega$ and ![]() $\beta$ are given to be real, and the eigenvalue

$\beta$ are given to be real, and the eigenvalue ![]() $\alpha = \alpha _r + \textrm {i} \alpha _i$ is complex with the opposite of its imaginary part representing the growth rate. Usually, the imaginary part is much smaller than the real part in the boundary-layer flow, i.e.

$\alpha = \alpha _r + \textrm {i} \alpha _i$ is complex with the opposite of its imaginary part representing the growth rate. Usually, the imaginary part is much smaller than the real part in the boundary-layer flow, i.e. ![]() $|\alpha _i| \ll |\alpha _r|$. The numerical details to solve the eigenvalue system (2.10) with (2.12a,b) can be found in our previous papers (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Liu and Wu2020; Song, Zhao & Huang Reference Song, Zhao and Huang2020; Dong & Zhao Reference Dong and Zhao2021; Li & Dong Reference Li and Dong2021).

$|\alpha _i| \ll |\alpha _r|$. The numerical details to solve the eigenvalue system (2.10) with (2.12a,b) can be found in our previous papers (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Liu and Wu2020; Song, Zhao & Huang Reference Song, Zhao and Huang2020; Dong & Zhao Reference Dong and Zhao2021; Li & Dong Reference Li and Dong2021).

2.3.2. Nonlinear parabolised stability equations (NPSEs)

The NPSE approach (Bertolotti, Herbert & Spalart Reference Bertolotti, Herbert and Spalart1992; Chang & Malik Reference Chang and Malik1994) is considered as a more accurate means because it allows the slow streamwise variation of the perturbation profiles and takes into account the non-parallelism of the base flow. The only approximation is that the ![]() $\partial _{xx}$ terms are neglected to reduce the elliptic system to a parabolised system, which is quite reasonable for a boundary layer with a smooth wall. Expressing

$\partial _{xx}$ terms are neglected to reduce the elliptic system to a parabolised system, which is quite reasonable for a boundary layer with a smooth wall. Expressing ![]() $\tilde {\phi }$ and

$\tilde {\phi }$ and ![]() $\boldsymbol {F}$ in terms of the Fourier series with respect to

$\boldsymbol {F}$ in terms of the Fourier series with respect to ![]() $z$ and

$z$ and ![]() $t$, we obtain

$t$, we obtain

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{gathered} \tilde{\phi}(x,y,z,t) = \sum_{m ={-}M_e}^{{M_e}} {\sum_{n ={-} {N_e}}^{{N_e}} {\mathop{\phi}\limits^{{\smile}}}_{mn}(x,y)\exp [\text{i} \left(n {\beta_0} z - m {\omega_0} t\right) ] } ,\\ {\boldsymbol{F}} (x,y,z,t) = \sum_{m ={-}M_e}^{{M_e}} {\sum_{n ={-} {N_e}}^{{N_e}} {{{{\boldsymbol{\tilde{F}}}}_{mn} (x,y) }{ \exp [ {\text{i}\left( {n{\beta_0}z - m{\omega _0}t} \right)} ] }} } , \end{gathered} \right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{gathered} \tilde{\phi}(x,y,z,t) = \sum_{m ={-}M_e}^{{M_e}} {\sum_{n ={-} {N_e}}^{{N_e}} {\mathop{\phi}\limits^{{\smile}}}_{mn}(x,y)\exp [\text{i} \left(n {\beta_0} z - m {\omega_0} t\right) ] } ,\\ {\boldsymbol{F}} (x,y,z,t) = \sum_{m ={-}M_e}^{{M_e}} {\sum_{n ={-} {N_e}}^{{N_e}} {{{{\boldsymbol{\tilde{F}}}}_{mn} (x,y) }{ \exp [ {\text{i}\left( {n{\beta_0}z - m{\omega _0}t} \right)} ] }} } , \end{gathered} \right\} \end{equation}

where ![]() $M_e$ and

$M_e$ and ![]() $N_e$ denote the orders of the Fourier-series truncation. In this paper, we choose

$N_e$ denote the orders of the Fourier-series truncation. In this paper, we choose ![]() $M_e =5$ and

$M_e =5$ and ![]() $N_e =5$, which has been confirmed to be sufficient via resolution tests. Considering that the perturbations are propagating with two length scales, a fast one with an oscillatory manner and a slow one related to the non-parallelism, we express the perturbation profile

$N_e =5$, which has been confirmed to be sufficient via resolution tests. Considering that the perturbations are propagating with two length scales, a fast one with an oscillatory manner and a slow one related to the non-parallelism, we express the perturbation profile ![]() $\mathop {\phi }\limits ^{\smile }$ in terms of a Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin (WKB) form,

$\mathop {\phi }\limits ^{\smile }$ in terms of a Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin (WKB) form,

where each Fourier component is denoted by ![]() $(m,n)$,

$(m,n)$, ![]() $\omega _{0}$ and

$\omega _{0}$ and ![]() $n_{0}$ are the fundamental frequency and spanwise wavenumber, respectively, and

$n_{0}$ are the fundamental frequency and spanwise wavenumber, respectively, and ![]() $\alpha _{mn}$ represents the complex streamwise wavenumber of

$\alpha _{mn}$ represents the complex streamwise wavenumber of ![]() $(m,n)$. The shape function

$(m,n)$. The shape function ![]() $\check {\phi }_{mn}$ varies slowly with

$\check {\phi }_{mn}$ varies slowly with ![]() $x$. The integral in (2.14) starts from a reference streamwise position

$x$. The integral in (2.14) starts from a reference streamwise position ![]() $x_0$, which is selected as the inlet of the computational domain for the numerical calculations in this paper, namely,

$x_0$, which is selected as the inlet of the computational domain for the numerical calculations in this paper, namely, ![]() $x_0 \equiv 0$.

$x_0 \equiv 0$.

Neglecting the ![]() $\partial _{xx} \check {\phi }_{mn}$ terms, (2.7) is reduced to

$\partial _{xx} \check {\phi }_{mn}$ terms, (2.7) is reduced to

where the matrices ![]() ${{{\boldsymbol {\tilde {A}}}}_{mn}}$,

${{{\boldsymbol {\tilde {A}}}}_{mn}}$, ![]() ${{{\boldsymbol {\tilde {B}}}}_{mn}}$ and

${{{\boldsymbol {\tilde {B}}}}_{mn}}$ and ![]() ${{{\boldsymbol {\tilde {D}}}}_{mn}}$ are given by

${{{\boldsymbol {\tilde {D}}}}_{mn}}$ are given by

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{aligned} {{{\boldsymbol{\tilde{A}}}}_{mn}} & = {\boldsymbol{A}} + 2{\rm{i}}{\alpha _{mn}}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xx}} + {\rm{i}}n{\beta_0}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xz }},\\ {{{\boldsymbol{\tilde{B}}}}_{mn}} & = {\boldsymbol{B}} + {\rm{i}}{\alpha _{mn}}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xy}} + {\rm{i}}n{\beta_0}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{yz }},\\ {{{\boldsymbol{\tilde{D}}}}_{mn}} & ={-} {\rm{i}}m{\omega _0} {\boldsymbol {G}} + {\rm{i}}{\alpha _{mn}}{\boldsymbol{A}} + {\rm{i}}n{\beta_0}{\boldsymbol{C}} + {\boldsymbol{D}}- {n^2}\beta_0^2{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{z z }}\\ & \quad - \left( {\alpha _{mn}^2 - {\rm{i}}\frac{{{\rm d}{\alpha _{mn}}}}{{{\rm d}\kern0.06em x}}} \right){{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xx}} - n{\alpha _{mn}}{\beta_0}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xz }},\\ {{{{{\boldsymbol{\check F}}}_{mn}}}} & = {{{{{\boldsymbol{\tilde{F}}}}_{mn}}}}{{{\exp({-\text{i}\int_{{x_0}}^x {{\alpha _{mn}} (\bar x)\,{\rm d}\kern0.06em \bar x} })}}}. \end{aligned} \right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{aligned} {{{\boldsymbol{\tilde{A}}}}_{mn}} & = {\boldsymbol{A}} + 2{\rm{i}}{\alpha _{mn}}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xx}} + {\rm{i}}n{\beta_0}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xz }},\\ {{{\boldsymbol{\tilde{B}}}}_{mn}} & = {\boldsymbol{B}} + {\rm{i}}{\alpha _{mn}}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xy}} + {\rm{i}}n{\beta_0}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{yz }},\\ {{{\boldsymbol{\tilde{D}}}}_{mn}} & ={-} {\rm{i}}m{\omega _0} {\boldsymbol {G}} + {\rm{i}}{\alpha _{mn}}{\boldsymbol{A}} + {\rm{i}}n{\beta_0}{\boldsymbol{C}} + {\boldsymbol{D}}- {n^2}\beta_0^2{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{z z }}\\ & \quad - \left( {\alpha _{mn}^2 - {\rm{i}}\frac{{{\rm d}{\alpha _{mn}}}}{{{\rm d}\kern0.06em x}}} \right){{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xx}} - n{\alpha _{mn}}{\beta_0}{{\boldsymbol{V}}_{xz }},\\ {{{{{\boldsymbol{\check F}}}_{mn}}}} & = {{{{{\boldsymbol{\tilde{F}}}}_{mn}}}}{{{\exp({-\text{i}\int_{{x_0}}^x {{\alpha _{mn}} (\bar x)\,{\rm d}\kern0.06em \bar x} })}}}. \end{aligned} \right\} \end{equation}The inflow perturbations are given by (2.8), and the lower and upper boundary conditions are

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{gathered} ({{\check u}_{mn}},{{\check v}_{mn}},{{\check w}_{mn}},{{\check T}_{mn}}) = (0,0,0,0), \quad \text{at} \ y = 0 ,\\ ({{\check \rho}_{mn}},{{\check u}_{mn}},{{\check v}_{mn}},{{\check w}_{mn}},{{\check T}_{mn}}) \to (0,0,0,0,0), \quad \text{as} \ y \to \infty. \end{gathered} \right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{gathered} ({{\check u}_{mn}},{{\check v}_{mn}},{{\check w}_{mn}},{{\check T}_{mn}}) = (0,0,0,0), \quad \text{at} \ y = 0 ,\\ ({{\check \rho}_{mn}},{{\check u}_{mn}},{{\check v}_{mn}},{{\check w}_{mn}},{{\check T}_{mn}}) \to (0,0,0,0,0), \quad \text{as} \ y \to \infty. \end{gathered} \right\} \end{equation}

To solve for the complex streamwise wavenumber ![]() $\alpha _{mn}$ and the profiles

$\alpha _{mn}$ and the profiles ![]() $\check {\phi }$, an iterative procedure is employed, which can be found from Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Zhang, Liu and Luo2016), and our code validation is provided in the appendix of Song et al. (Reference Song, Dong and Zhao2022).

$\check {\phi }$, an iterative procedure is employed, which can be found from Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Zhang, Liu and Luo2016), and our code validation is provided in the appendix of Song et al. (Reference Song, Dong and Zhao2022).

Additionally, if ![]() $\check {\boldsymbol {F}}_{mn}$ is set to be zero, then (2.15) is recast to the linear PSE (LPSE), which can be used to track the evolution of each linear mode individually. To be distinguished, the PSE approach with

$\check {\boldsymbol {F}}_{mn}$ is set to be zero, then (2.15) is recast to the linear PSE (LPSE), which can be used to track the evolution of each linear mode individually. To be distinguished, the PSE approach with ![]() $\check {\boldsymbol {F}}_{mn}$ being retained is referred to as the nonlinear PSE (NPSE) in this paper.

$\check {\boldsymbol {F}}_{mn}$ being retained is referred to as the nonlinear PSE (NPSE) in this paper.

2.3.3. Secondary instability analysis (SIA) for a wavy base flow

When the amplitude of the fundamental perturbation ![]() $(1,0)$ has reached a finite level, the rapid growth of the infinitesimal perturbations can be explained by the SI based on a wavy profile driven by a 2-D quasi-saturated travelling mode.

$(1,0)$ has reached a finite level, the rapid growth of the infinitesimal perturbations can be explained by the SI based on a wavy profile driven by a 2-D quasi-saturated travelling mode.

Since the growth rate of the fundamental mode is usually much smaller than that of the SI mode, as confirmed by many numerical studies such as those of Sivasubramanian & Fasel (Reference Sivasubramanian and Fasel2015), Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017) and Hader & Fasel (Reference Hader and Fasel2019), we take ![]() $\alpha _{10}$ to leading order to be real and introduce

$\alpha _{10}$ to leading order to be real and introduce ![]() $\breve \alpha \equiv \mathrm {Re} (\alpha _{10})$. Thus, the base flow for the SIA is a superposition of the steady base flow and a series of quasi-saturated travelling waves. In a moving frame, the base flow

$\breve \alpha \equiv \mathrm {Re} (\alpha _{10})$. Thus, the base flow for the SIA is a superposition of the steady base flow and a series of quasi-saturated travelling waves. In a moving frame, the base flow ![]() $\breve {\varPhi }_{B} \equiv [\breve \rho _B,\breve U_B,0,0,\breve T_B]$ is expressed as

$\breve {\varPhi }_{B} \equiv [\breve \rho _B,\breve U_B,0,0,\breve T_B]$ is expressed as

\begin{equation} {\breve {\varPhi}} _{B} (\tilde{x}, y) = (1/T_{B}, {U_B}-c_r, 0, 0, T_{B})(\kern0.7pt y) + \sum_{m ={-} M_{W}}^{M_{W}} {{{\mathop{\phi}\limits^{{\smile}}}_{m0}}\left(\kern0.7pt y \right){\exp({\text{i} m \breve \alpha \tilde{x}}}}) +\cdots , \end{equation}

\begin{equation} {\breve {\varPhi}} _{B} (\tilde{x}, y) = (1/T_{B}, {U_B}-c_r, 0, 0, T_{B})(\kern0.7pt y) + \sum_{m ={-} M_{W}}^{M_{W}} {{{\mathop{\phi}\limits^{{\smile}}}_{m0}}\left(\kern0.7pt y \right){\exp({\text{i} m \breve \alpha \tilde{x}}}}) +\cdots , \end{equation}

where ![]() $c_r= \omega _{0}/{\breve \alpha }$,

$c_r= \omega _{0}/{\breve \alpha }$, ![]() $\tilde {x} = x - c_rt$ is the Galilean transformed coordinate and

$\tilde {x} = x - c_rt$ is the Galilean transformed coordinate and ![]() $M_W$ denotes the order of the Fourier-series truncation. The laminar base flow

$M_W$ denotes the order of the Fourier-series truncation. The laminar base flow ![]() $\varPhi _{B}$ develops with a length scale much greater than the wavelength of the fundamental mode

$\varPhi _{B}$ develops with a length scale much greater than the wavelength of the fundamental mode ![]() $2 {\rm \pi}/ {\breve \alpha }$, and so the non-parallelism of

$2 {\rm \pi}/ {\breve \alpha }$, and so the non-parallelism of ![]() $\varPhi _B$ in the local region is neglected in the present analysis, rendering a periodic feature of

$\varPhi _B$ in the local region is neglected in the present analysis, rendering a periodic feature of ![]() $\breve \varPhi _B$ in the streamwise direction.

$\breve \varPhi _B$ in the streamwise direction.

According to the Floquet theory, the periodic base flow supports the instability modes ![]() $\tilde {\phi }_W$ which can be expressed as

$\tilde {\phi }_W$ which can be expressed as

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{gathered} {{\tilde{\phi}_W }(\tilde{x},y,z,t)} = \epsilon_W {\breve \phi _W}\left( {\tilde{x},y} \right){\exp{[\tilde{\sigma}( \tilde{x}+c_rt)+\text{i} \beta z+{\text{i}{\tilde{\sigma} _d} \breve \alpha \tilde{x}}]}} + \text{c.c.},\\ {\breve \phi _W}\left( {\tilde{x},y} \right) = \sum_{n ={-} {N_W}}^{{N_W}} {{{\hat \phi }_{W,n}}\left(\kern0.7pt y \right)\exp \left( { \text{i} n \breve \alpha \tilde{x}} \right)}, \end{gathered} \right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{gathered} {{\tilde{\phi}_W }(\tilde{x},y,z,t)} = \epsilon_W {\breve \phi _W}\left( {\tilde{x},y} \right){\exp{[\tilde{\sigma}( \tilde{x}+c_rt)+\text{i} \beta z+{\text{i}{\tilde{\sigma} _d} \breve \alpha \tilde{x}}]}} + \text{c.c.},\\ {\breve \phi _W}\left( {\tilde{x},y} \right) = \sum_{n ={-} {N_W}}^{{N_W}} {{{\hat \phi }_{W,n}}\left(\kern0.7pt y \right)\exp \left( { \text{i} n \breve \alpha \tilde{x}} \right)}, \end{gathered} \right\} \end{equation}

where ![]() $\tilde {\sigma }$ represents the growth rate,

$\tilde {\sigma }$ represents the growth rate, ![]() $\beta$ is the spanwise wavenumber,

$\beta$ is the spanwise wavenumber, ![]() $\tilde {\sigma }_{d}$ is the detuning parameter, and

$\tilde {\sigma }_{d}$ is the detuning parameter, and ![]() $N_W$ is the order of the Fourier-series truncation and

$N_W$ is the order of the Fourier-series truncation and ![]() $\epsilon _W \ll 1$ measures the amplitude. For the fundamental resonance, we take

$\epsilon _W \ll 1$ measures the amplitude. For the fundamental resonance, we take ![]() $\tilde {\sigma } _d=0$. The component

$\tilde {\sigma } _d=0$. The component ![]() $\hat {\phi }_{W,0}$ denotes the streak component, and

$\hat {\phi }_{W,0}$ denotes the streak component, and ![]() $\hat {\phi }_{W,n}$ with

$\hat {\phi }_{W,n}$ with ![]() $n \ne 0$ represents the travelling mode. Substituting (2.18) and (2.19) into (2.7) with

$n \ne 0$ represents the travelling mode. Substituting (2.18) and (2.19) into (2.7) with ![]() $O(\epsilon _W^{2})$ terms neglected, we arrive at a linear system,

$O(\epsilon _W^{2})$ terms neglected, we arrive at a linear system,

where

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{aligned} { {{\boldsymbol M}_0}} & = \left( { {\boldsymbol{A}} + {\rm{i}} \beta { {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{ x z}}}} \right)\frac{\partial }{{\partial \tilde{x}}} + \left( {{\boldsymbol {B}} + {\rm{i}} \beta { {{\boldsymbol V}_{y z}}}} \right)\frac{\partial }{{\partial y}} + [ { {\boldsymbol {D}} + {\rm{i}} \beta {\boldsymbol { C}} + {{( {{\rm{i}} \beta } )}^2}{ { {{\boldsymbol V}_{ z z}}}}} ]\\ & \quad +{{{\boldsymbol V}_{xx}}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}}}{{\partial {{\tilde{x}}^2}}} + { {{\boldsymbol V}_{yy}}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}}}{{\partial {y^2}}} + { {{\boldsymbol V}_{xy}}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}}}{{\partial \tilde{x} \partial y}},\\ { {{\boldsymbol M}_1}} & = \left( { {\boldsymbol {A}} + \text{i} \beta { {{\boldsymbol V}_{ x z}}}} \right) + 2 { {{\boldsymbol V}_{xx}}}\frac{\partial }{{\partial \tilde{x}}} + {{{\boldsymbol V}_{xy}}}\frac{\partial }{{\partial y}} + c {\boldsymbol {G}} ,\\ { {{\boldsymbol M}_2}} & = { {{\boldsymbol V}_{xx}}}. \end{aligned} \right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{aligned} { {{\boldsymbol M}_0}} & = \left( { {\boldsymbol{A}} + {\rm{i}} \beta { {{\boldsymbol{V}}_{ x z}}}} \right)\frac{\partial }{{\partial \tilde{x}}} + \left( {{\boldsymbol {B}} + {\rm{i}} \beta { {{\boldsymbol V}_{y z}}}} \right)\frac{\partial }{{\partial y}} + [ { {\boldsymbol {D}} + {\rm{i}} \beta {\boldsymbol { C}} + {{( {{\rm{i}} \beta } )}^2}{ { {{\boldsymbol V}_{ z z}}}}} ]\\ & \quad +{{{\boldsymbol V}_{xx}}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}}}{{\partial {{\tilde{x}}^2}}} + { {{\boldsymbol V}_{yy}}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}}}{{\partial {y^2}}} + { {{\boldsymbol V}_{xy}}}\frac{{{\partial ^2}}}{{\partial \tilde{x} \partial y}},\\ { {{\boldsymbol M}_1}} & = \left( { {\boldsymbol {A}} + \text{i} \beta { {{\boldsymbol V}_{ x z}}}} \right) + 2 { {{\boldsymbol V}_{xx}}}\frac{\partial }{{\partial \tilde{x}}} + {{{\boldsymbol V}_{xy}}}\frac{\partial }{{\partial y}} + c {\boldsymbol {G}} ,\\ { {{\boldsymbol M}_2}} & = { {{\boldsymbol V}_{xx}}}. \end{aligned} \right\} \end{equation}The wall-normal boundary conditions read

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{gathered} {\breve u}_{W}= {\breve v}_{W}={\breve w}_{W}={\breve T}_{W}=0, \quad \text{at} \ y=0, \\ ({\breve \rho}_{W},{\breve u}_{W}, {\breve v}_{W},{\breve w}_{W},{\breve T}_{W}) \to 0, \quad \text{as} \ y \to \infty. \end{gathered} \right\} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left. \begin{gathered} {\breve u}_{W}= {\breve v}_{W}={\breve w}_{W}={\breve T}_{W}=0, \quad \text{at} \ y=0, \\ ({\breve \rho}_{W},{\breve u}_{W}, {\breve v}_{W},{\breve w}_{W},{\breve T}_{W}) \to 0, \quad \text{as} \ y \to \infty. \end{gathered} \right\} \end{equation}

The linear system (2.20) with the homogeneous boundary conditions forms an eigenvalue problem with the growth rate ![]() $\tilde {\sigma }$ being the eigenvalue. In our paper, we choose

$\tilde {\sigma }$ being the eigenvalue. In our paper, we choose ![]() $(M_W,N_W)=(3,6)$, which has been confirmed to be of sufficient accuracy. Such an analysis has also been used in the study of the SI of 2-D Mack second modes in hypersonic boundary layers (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Liu, Mughal, Yu and Bai2020), and our code validation and discretisation method are provided by Song, Zhao & Dong (Reference Song, Zhao and Dong2023).

$(M_W,N_W)=(3,6)$, which has been confirmed to be of sufficient accuracy. Such an analysis has also been used in the study of the SI of 2-D Mack second modes in hypersonic boundary layers (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Liu, Mughal, Yu and Bai2020), and our code validation and discretisation method are provided by Song, Zhao & Dong (Reference Song, Zhao and Dong2023).

3. Demonstration of the fundamental resonance regime by NPSE calculations

3.1. Case studies

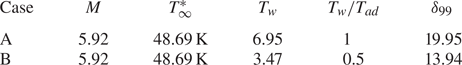

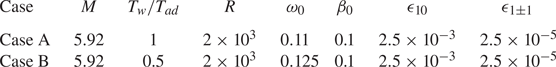

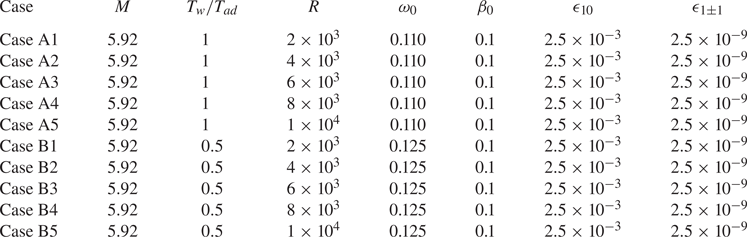

For demonstration of the FR, we select a wind-tunnel condition of Maslov et al. (Reference Maslov, Shiplyuk, Sidorenko and Arnal2001), for which the Mach number and temperature of the oncoming stream are 5.92 and 48.69 K, respectively. Such an oncoming condition was also used by Dong et al. (Reference Dong, Liu and Wu2020) and Dong & Zhao (Reference Dong and Zhao2021). Two wall temperatures as listed in table 1 are selected, which are equal to and a half of the adiabatic wall temperature ![]() $T_{ad}$, where

$T_{ad}$, where ![]() $T_{ad}$ is estimated by an empirical formula in White (Reference White2006, p. 512),

$T_{ad}$ is estimated by an empirical formula in White (Reference White2006, p. 512),

The nominal boundary-layer thickness for each case is also listed in the table.

Table 1. Parameters characterising the flow condition.

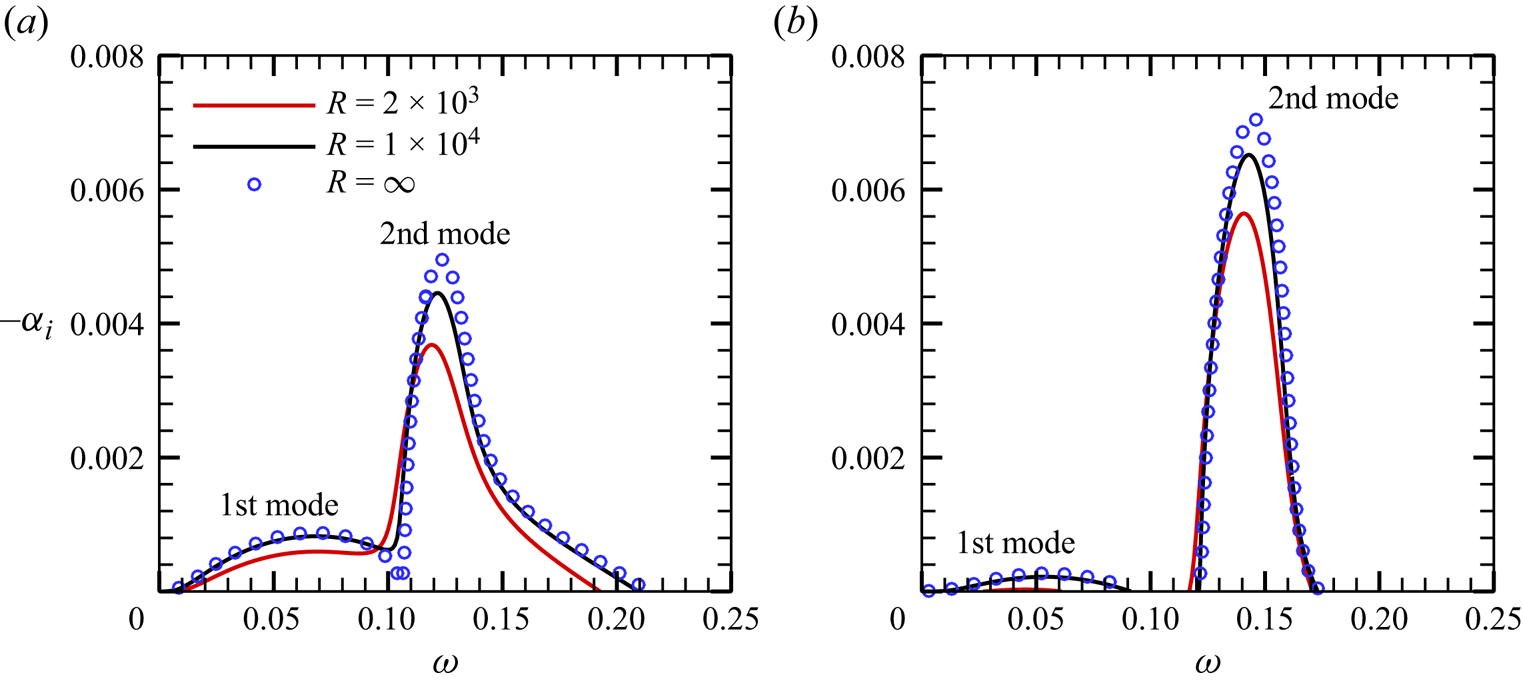

3.2. Base flow and its linear instability

The base-flow profiles of ![]() $U_B$ and

$U_B$ and ![]() $T_B$ at

$T_B$ at ![]() $x=0$ for the two cases are shown in figure 3. As the wall temperature decreases, the boundary-layer thickness is reduced and the shear rates of

$x=0$ for the two cases are shown in figure 3. As the wall temperature decreases, the boundary-layer thickness is reduced and the shear rates of ![]() $U_B$ and

$U_B$ and ![]() $T_B$ at the wall increase. Solving the O-S equations numerically based on these base-flow profiles, we obtain the dependence of the growth rates

$T_B$ at the wall increase. Solving the O-S equations numerically based on these base-flow profiles, we obtain the dependence of the growth rates ![]() $-\alpha _i$ of 2-D Mack modes on the frequency

$-\alpha _i$ of 2-D Mack modes on the frequency ![]() $\omega$ for the two cases, as shown in figures 4(a) and 4(b). Two distinguished unstable zones appear for each case, which are marked by the Mack first and second modes (Mack Reference Mack1987). The second mode is more unstable than the first mode, and decrease of the wall temperature leads to an enhancement of the second mode and suppression of the first mode overall. In each panel, we show the results for three Reynolds numbers, namely,

$\omega$ for the two cases, as shown in figures 4(a) and 4(b). Two distinguished unstable zones appear for each case, which are marked by the Mack first and second modes (Mack Reference Mack1987). The second mode is more unstable than the first mode, and decrease of the wall temperature leads to an enhancement of the second mode and suppression of the first mode overall. In each panel, we show the results for three Reynolds numbers, namely, ![]() $R=2 \times 10^{3}$,

$R=2 \times 10^{3}$, ![]() $1\times 10^{4}$ and

$1\times 10^{4}$ and ![]() $\infty$ (for this case, the O-S equations reduce to the Rayleigh equations, which will be shown in § 4.1). Overall, increase of the Reynolds number leads to a greater growth rate, indicating the inviscid nature of the 2-D Mack modes.

$\infty$ (for this case, the O-S equations reduce to the Rayleigh equations, which will be shown in § 4.1). Overall, increase of the Reynolds number leads to a greater growth rate, indicating the inviscid nature of the 2-D Mack modes.

Figure 3. (a) Streamwise velocity and (b) temperature of the compressible Blasius solution at ![]() $x=0$ forCases A and B. The red and black horizontal lines denote the nominal boundary-layer thicknesses for the two cases, respectively.

$x=0$ forCases A and B. The red and black horizontal lines denote the nominal boundary-layer thicknesses for the two cases, respectively.

Figure 4. Dependence on the frequency ![]() $\omega$ of the growth rate

$\omega$ of the growth rate ![]() $-\alpha _i$ of 2-D modes for (a) Case A and(b) Case B.

$-\alpha _i$ of 2-D modes for (a) Case A and(b) Case B.

The accumulated amplitude of each Fourier mode can be quantified by an ![]() $N$ factor according to the LST, defined by

$N$ factor according to the LST, defined by

In figure 5, we plot the streamwise evolution of the ![]() $N$ factors of 2-D second modes with representative frequencies in the second-mode frequency band for

$N$ factors of 2-D second modes with representative frequencies in the second-mode frequency band for ![]() $R=2 \times 10^{3}$. It is observed that for Cases A and B, the frequencies of the most amplified second modes from

$R=2 \times 10^{3}$. It is observed that for Cases A and B, the frequencies of the most amplified second modes from ![]() $x=0$ to

$x=0$ to ![]() $1200$ are

$1200$ are ![]() $\omega =0.11$ and

$\omega =0.11$ and ![]() $\omega =0.125$, respectively, and they are selected as the fundamental frequencies

$\omega =0.125$, respectively, and they are selected as the fundamental frequencies ![]() $\omega _0$ in the following NPSE calculations.

$\omega _0$ in the following NPSE calculations.

Figure 5. Streamwise evolution of the ![]() $N$ factors of 2-D second modes for (a) Case A and (b) Case B at

$N$ factors of 2-D second modes for (a) Case A and (b) Case B at ![]() $R=2 \times 10^{3}$.

$R=2 \times 10^{3}$.

3.3. Calculations of the fundamental resonance

For each case, we calculate the nonlinear evolution of the initial perturbations (2.8) using the NPSE approach, until the calculation blows up, indicating the emergence of the transition onset in a short distance downstream (Dong, Zhang & Zhou Reference Dong, Zhang and Zhou2008). The parameters for Cases A and B are summarised in table 2. For Case A, the contours of the instantaneous velocity ![]() $u$ in the

$u$ in the ![]() $x\unicode{x2013} z$ plane at two wall-normal positions are shown in figures 6(a) and 6(b). For

$x\unicode{x2013} z$ plane at two wall-normal positions are shown in figures 6(a) and 6(b). For ![]() $x<930$, the perturbation field is dominated by planar waves; however, 3-D structures appear at further downstream locations

$x<930$, the perturbation field is dominated by planar waves; however, 3-D structures appear at further downstream locations ![]() $(x>930)$ and grow with a high rate. Panels (c,d) show the time-averaged streamwise velocity at the same wall-normal positions for comparison, and the low- and high-speed streaks are observed evidently in the late nonlinear phase. In panel (e), we plot the contours of the time-averaged streamwise velocity in the

$(x>930)$ and grow with a high rate. Panels (c,d) show the time-averaged streamwise velocity at the same wall-normal positions for comparison, and the low- and high-speed streaks are observed evidently in the late nonlinear phase. In panel (e), we plot the contours of the time-averaged streamwise velocity in the ![]() $y$–

$y$–![]() $z$ plane at

$z$ plane at ![]() $x=1360$, where the spanwise localised blue structure indicates the low-speed streaks. The streamlines show the counter-rotating roll structures of the streamwise vorticities, which push the near-wall fluids upward, showing a lift-up mechanism for the formation of the low-speed streaks.

$x=1360$, where the spanwise localised blue structure indicates the low-speed streaks. The streamlines show the counter-rotating roll structures of the streamwise vorticities, which push the near-wall fluids upward, showing a lift-up mechanism for the formation of the low-speed streaks.

Table 2. Parameters for case studies in § 3.3.

Figure 6. Contours of the velocity field obtained by the NPSE for Case A: (a,b) instantaneous velocity ![]() $u$ in the

$u$ in the ![]() $x$–

$x$–![]() $z$ planes at

$z$ planes at ![]() $y=5\,\% \delta _{99}$ and

$y=5\,\% \delta _{99}$ and ![]() $y=40\,\% \delta _{99}$, respectively; (c,d) time-averaged velocity in the

$y=40\,\% \delta _{99}$, respectively; (c,d) time-averaged velocity in the ![]() $x$–

$x$–![]() $z$ planes at

$z$ planes at ![]() $y=5\,\% \delta _{99}$ and

$y=5\,\% \delta _{99}$ and ![]() $y=40\,\% \delta _{99}$, respectively; (e) time-averaged velocity in the

$y=40\,\% \delta _{99}$, respectively; (e) time-averaged velocity in the ![]() $y$–

$y$–![]() $z$ plane at

$z$ plane at ![]() $x=1360$, where the arrayed curves show the streamlines.

$x=1360$, where the arrayed curves show the streamlines.

The amplitude of each Fourier component in the physical space can be expressed as

\begin{equation} {\tilde{u}_{\max }^{(m,n)}(x)} = \left\{ \begin{array}{@{}ll} {\max _y}\left| {{{\mathop{u}\limits^{{\smile}}}_{mn}}\left( {x,y} \right) + {\rm c.c.}} \right|, & {{ m \ne 0 \lor n \ne 0}},\\ {\max _y}\left| {{{\mathop{u}\limits^{{\smile}}}_{mn}}\left( {x,y} \right) } \right|, & {{ m=0 \land n=0}}. \end{array} \right. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} {\tilde{u}_{\max }^{(m,n)}(x)} = \left\{ \begin{array}{@{}ll} {\max _y}\left| {{{\mathop{u}\limits^{{\smile}}}_{mn}}\left( {x,y} \right) + {\rm c.c.}} \right|, & {{ m \ne 0 \lor n \ne 0}},\\ {\max _y}\left| {{{\mathop{u}\limits^{{\smile}}}_{mn}}\left( {x,y} \right) } \right|, & {{ m=0 \land n=0}}. \end{array} \right. \end{equation}

In figure 7(a), we plot the streamwise evolution of ![]() ${\tilde {u}}_{max}^{(m,n)}$, shown by the solid lines. The amplitude of the fundamental mode

${\tilde {u}}_{max}^{(m,n)}$, shown by the solid lines. The amplitude of the fundamental mode ![]() $(1,0)$ agrees well with the linear result predicted by LPSE (shown by the red circles) until

$(1,0)$ agrees well with the linear result predicted by LPSE (shown by the red circles) until ![]() $x \approx 1100$, after which it saturates due to the nonlinearity. The oblique waves

$x \approx 1100$, after which it saturates due to the nonlinearity. The oblique waves ![]() $(1,\pm 1)$ grow with exactly the same rate, and so only the curve for

$(1,\pm 1)$ grow with exactly the same rate, and so only the curve for ![]() ${\tilde {u}}_{max}^{(1,1)}$ is plotted. It agrees with the linear prediction shown by the black circles until

${\tilde {u}}_{max}^{(1,1)}$ is plotted. It agrees with the linear prediction shown by the black circles until ![]() $x \approx 700$, after which a drastic amplification is observed. Although the other Fourier components are not introduced as initial perturbations, they are excited due to the mutual interaction of the introduced modes. The mean-flow distortion (MFD)

$x \approx 700$, after which a drastic amplification is observed. Although the other Fourier components are not introduced as initial perturbations, they are excited due to the mutual interaction of the introduced modes. The mean-flow distortion (MFD) ![]() $(0,0)$ and the harmonic mode

$(0,0)$ and the harmonic mode ![]() $(2,0)$ are driven by the self-interaction of mode

$(2,0)$ are driven by the self-interaction of mode ![]() $(1,0)$, and therefore, their growth rates are almost twice that of

$(1,0)$, and therefore, their growth rates are almost twice that of ![]() $(1,0)$ in most of the computational domain, as confirmed by comparison with the blue crosses. For

$(1,0)$ in most of the computational domain, as confirmed by comparison with the blue crosses. For ![]() $x > 700$, the streak component

$x > 700$, the streak component ![]() $(0,1)$ and the high-order harmonics

$(0,1)$ and the high-order harmonics ![]() $(2,1)$ grow at almost the same rate as

$(2,1)$ grow at almost the same rate as ![]() $(1,1)$, but their amplitudes differ by a remarkable amount; the amplitude of the streak mode

$(1,1)$, but their amplitudes differ by a remarkable amount; the amplitude of the streak mode ![]() $(0,1)$ is the greatest among the three. When the streak mode

$(0,1)$ is the greatest among the three. When the streak mode ![]() $(0,1)$ overwhelms the fundamental mode

$(0,1)$ overwhelms the fundamental mode ![]() $(1,0)$ and becomes the dominant perturbation, the calculation blows up, indicating that the transition to turbulence is not far.

$(1,0)$ and becomes the dominant perturbation, the calculation blows up, indicating that the transition to turbulence is not far.

Figure 7. Streamwise evolution of the NPSE results for Case A: (a) amplitude of each Fourier component ![]() $\hat u_{max}^{(m,n)}$; (b) perturbation energy of each Fourier component

$\hat u_{max}^{(m,n)}$; (b) perturbation energy of each Fourier component ![]() $E_{mn}$; (c) energy growth rate of each Fourier component

$E_{mn}$; (c) energy growth rate of each Fourier component ![]() $\sigma _E$; (d) coefficient of surface friction, where the

$\sigma _E$; (d) coefficient of surface friction, where the ![]() $C_f$ curve for turbulence is given by the empirical formula of White (Reference White2006, p. 553).

$C_f$ curve for turbulence is given by the empirical formula of White (Reference White2006, p. 553).

Alternatively, one can trace the evolution of the perturbation energy of each Fourier component, which is defined as (Chu Reference Chu1965)

where the superscript ![]() ${\dagger}$ denotes the complex conjugate with respect to its argument. The streamwise evolution of

${\dagger}$ denotes the complex conjugate with respect to its argument. The streamwise evolution of ![]() $E_{mn}$ for each Fourier component is shown in figure 7(b), and overall the same feature as in panel (a) is observed. This is quite predictable, because

$E_{mn}$ for each Fourier component is shown in figure 7(b), and overall the same feature as in panel (a) is observed. This is quite predictable, because ![]() $\tilde {u}$ and

$\tilde {u}$ and ![]() $\tilde {T}$ are the dominant components in

$\tilde {T}$ are the dominant components in ![]() $\tilde {\phi }$ with similar evolution trend, and the evolution of the perturbation energy should agree overall with that of each dominant component. Figure 7(c) further plots the evolution of the growth rate of the perturbation energy, defined as

$\tilde {\phi }$ with similar evolution trend, and the evolution of the perturbation energy should agree overall with that of each dominant component. Figure 7(c) further plots the evolution of the growth rate of the perturbation energy, defined as

Remarkably, in the interval of ![]() $x \in [900,1200]$, as highlighted by the dashed box, the growth rates of

$x \in [900,1200]$, as highlighted by the dashed box, the growth rates of ![]() $(0,1)$,

$(0,1)$, ![]() $(1,1)$ and

$(1,1)$ and ![]() $(2,1)$ are almost identical, and much greater than that of the fundamental mode in the linear phase. This is a representative feature of the FR, as also observed by Sivasubramanian & Fasel (Reference Sivasubramanian and Fasel2015), Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017) and Hader & Fasel (Reference Hader and Fasel2019). Such a high growth rate was explained by the SIA as introduced in § 2.3.3. In the SIA, the base flow is regarded as a superposition of the time- and spanwise-averaged mean flow and the quasi-saturated 2-D fundamental mode, together with its high-order harmonics, and the perturbation fields, including the streak mode, the 3-D travelling mode and higher-order harmonics with the same spanwise wavenumber, are governed by a linear eigenvalue system (2.20), with the growth rate

$(2,1)$ are almost identical, and much greater than that of the fundamental mode in the linear phase. This is a representative feature of the FR, as also observed by Sivasubramanian & Fasel (Reference Sivasubramanian and Fasel2015), Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017) and Hader & Fasel (Reference Hader and Fasel2019). Such a high growth rate was explained by the SIA as introduced in § 2.3.3. In the SIA, the base flow is regarded as a superposition of the time- and spanwise-averaged mean flow and the quasi-saturated 2-D fundamental mode, together with its high-order harmonics, and the perturbation fields, including the streak mode, the 3-D travelling mode and higher-order harmonics with the same spanwise wavenumber, are governed by a linear eigenvalue system (2.20), with the growth rate ![]() $\tilde {\sigma }$ appearing as the eigenvalue.

$\tilde {\sigma }$ appearing as the eigenvalue.

In figure 7(d), the streamwise evolution of the coefficients of the skin friction,

are plotted, where ![]() $\underline {u}$ and

$\underline {u}$ and ![]() $\underline {\mu }$ represent the temporal and spanwise average of the streamwise velocity and the dynamic viscosity. The

$\underline {\mu }$ represent the temporal and spanwise average of the streamwise velocity and the dynamic viscosity. The ![]() $C_f$ curve obtained by the NPSE calculation decreases with

$C_f$ curve obtained by the NPSE calculation decreases with ![]() $x$ gradually at the beginning, agreeing with the unperturbed laminar-flow state, but it starts to deviate from the laminar state at

$x$ gradually at the beginning, agreeing with the unperturbed laminar-flow state, but it starts to deviate from the laminar state at ![]() $x \approx 500$, indicating a moderate MFD appearing there. The

$x \approx 500$, indicating a moderate MFD appearing there. The ![]() $C_f$ curve reaches its first peak at

$C_f$ curve reaches its first peak at ![]() $x \approx 1000$, followed by a plateau until

$x \approx 1000$, followed by a plateau until ![]() $x \approx 1300$, after which it shows another increase until the blowup position. The double-increase phenomenon is typical for the fundamental resonance regime, as also reported by previous works (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017; Hader & Fasel Reference Hader and Fasel2019). The first increase is associated with the strong MFD induced by the finite-amplitude fundamental mode, and the following plateau agrees with the region of FR. Due to the FR, the streak mode becomes the dominant perturbation in the late phase, which, together with the travelling modes, may drive another type of secondary instability to support the growth of the high-frequency perturbations. Since these secondary instability modes amplify with high growth rates, which produce sufficient Reynolds stress to cause the rapid distortion of the mean flow, the parabolised assumption in the NPSE approach ceases to be valid, leading to the blowup of the NPSE calculation eventually.

$x \approx 1300$, after which it shows another increase until the blowup position. The double-increase phenomenon is typical for the fundamental resonance regime, as also reported by previous works (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Zhu and Lee2017; Hader & Fasel Reference Hader and Fasel2019). The first increase is associated with the strong MFD induced by the finite-amplitude fundamental mode, and the following plateau agrees with the region of FR. Due to the FR, the streak mode becomes the dominant perturbation in the late phase, which, together with the travelling modes, may drive another type of secondary instability to support the growth of the high-frequency perturbations. Since these secondary instability modes amplify with high growth rates, which produce sufficient Reynolds stress to cause the rapid distortion of the mean flow, the parabolised assumption in the NPSE approach ceases to be valid, leading to the blowup of the NPSE calculation eventually.

In figure 8, we compare the growth rates of modes ![]() $(1,1)$ and

$(1,1)$ and ![]() $(0,1)$,

$(0,1)$, ![]() $\sigma _E^{(1,1)}$ and

$\sigma _E^{(1,1)}$ and ![]() $\sigma _E^{(0,1)}$, with that predicted by SIA,

$\sigma _E^{(0,1)}$, with that predicted by SIA, ![]() $\tilde {\sigma }$. In the interval

$\tilde {\sigma }$. In the interval ![]() $x \in [900,1200]$, the three curves agree with each other. The perturbation profiles of

$x \in [900,1200]$, the three curves agree with each other. The perturbation profiles of ![]() $(0,1)$ and

$(0,1)$ and ![]() $(1,1)$ obtained by the two approaches also agree well, as shown in figure 9. In fact,

$(1,1)$ obtained by the two approaches also agree well, as shown in figure 9. In fact, ![]() $\hat {u}_{01}$,

$\hat {u}_{01}$, ![]() $\hat {v}_{01}$ and

$\hat {v}_{01}$ and ![]() $\hat {T}_{01}$ are real and

$\hat {T}_{01}$ are real and ![]() $\hat {w}_{01}$ is pure imaginary, which will be discussed in § 4.2.1. Observations in figure 9 also indicate that the amplitude of the streamwise velocity of the streak mode

$\hat {w}_{01}$ is pure imaginary, which will be discussed in § 4.2.1. Observations in figure 9 also indicate that the amplitude of the streamwise velocity of the streak mode ![]() $\hat {u}_{01}$ is much greater than that of the 3-D travelling mode

$\hat {u}_{01}$ is much greater than that of the 3-D travelling mode ![]() $\hat {u}_{11}$, agreeing with the amplitude evolution in figure 7(a). For the profiles of the temperature perturbation, the streak mode in the bulk of the boundary layer

$\hat {u}_{11}$, agreeing with the amplitude evolution in figure 7(a). For the profiles of the temperature perturbation, the streak mode in the bulk of the boundary layer ![]() $\hat {T}_{01}$ is also much greater than the 3-D travelling mode

$\hat {T}_{01}$ is also much greater than the 3-D travelling mode ![]() $\hat {T}_{11}$, but it is much weaker in the near-wall region. Although the SIA can predict quantitatively the growth rates and profiles of both the streak mode and 3-D travelling modes in the interval

$\hat {T}_{11}$, but it is much weaker in the near-wall region. Although the SIA can predict quantitatively the growth rates and profiles of both the streak mode and 3-D travelling modes in the interval ![]() $[900,1200]$, the underlining mechanism determining the dominant role of the streak mode in the bulk region is not obvious. To answer these questions, a more in-depth analysis is required as will be introduced in the following section. Numerical results for Case B show the same feature, which will be illustrated in detail in § 5.

$[900,1200]$, the underlining mechanism determining the dominant role of the streak mode in the bulk region is not obvious. To answer these questions, a more in-depth analysis is required as will be introduced in the following section. Numerical results for Case B show the same feature, which will be illustrated in detail in § 5.

Figure 8. Comparison of the growth rate ![]() $\sigma _E$ obtained by the NPSE calculation with the SIA prediction

$\sigma _E$ obtained by the NPSE calculation with the SIA prediction ![]() $\tilde {\sigma }$.

$\tilde {\sigma }$.

Figure 9. Comparison of the perturbation profiles for ![]() $(0,1)$ and

$(0,1)$ and ![]() $(1,1)$ obtained by the SIA and NPSE approaches for Case A at

$(1,1)$ obtained by the SIA and NPSE approaches for Case A at ![]() $x=1000$. The profiles are normalised by the maximum of

$x=1000$. The profiles are normalised by the maximum of ![]() ${\hat v}_{01}$.

${\hat v}_{01}$.

4. Asymptotic analysis for the principle of the fundamental resonance

4.1. Flow decomposition and the 2-D fundamental mode

To reveal the principle mechanism of the FR, we perform a weakly nonlinear analysis based on the high-Reynolds-number asymptotic technique. In the weakly nonlinear phase, the perturbation field ![]() $\tilde {\phi }=(\tilde {\rho },\tilde {u}, \tilde {v}, \tilde {w},\tilde {T})$ defined in (2.6) includes a set of harmonic perturbations,

$\tilde {\phi }=(\tilde {\rho },\tilde {u}, \tilde {v}, \tilde {w},\tilde {T})$ defined in (2.6) includes a set of harmonic perturbations,

where ![]() $\bar \epsilon _{mn} \ll 1$ denotes the amplitude of each component in the nonlinear phase,

$\bar \epsilon _{mn} \ll 1$ denotes the amplitude of each component in the nonlinear phase, ![]() $\textrm {h.o.t.}$ denotes the high-order terms, and the subscripts

$\textrm {h.o.t.}$ denotes the high-order terms, and the subscripts ![]() $00$, 10, 11 ( and 1–1) and 01 denote the MFD, the fundamental mode, the 3-D travelling modes and the streak mode, respectively. According to the numerical results in § 3.3, we know that the amplitude of the fundamental mode

$00$, 10, 11 ( and 1–1) and 01 denote the MFD, the fundamental mode, the 3-D travelling modes and the streak mode, respectively. According to the numerical results in § 3.3, we know that the amplitude of the fundamental mode ![]() $\bar {\epsilon }_{10}$ is much greater than those of the 3-D travelling modes and the streak mode, namely,

$\bar {\epsilon }_{10}$ is much greater than those of the 3-D travelling modes and the streak mode, namely,

In the following analysis, we will focus on the region ![]() $x>900$, for which the fundamental mode

$x>900$, for which the fundamental mode ![]() $\tilde {\phi }_{10}$ evolves either in the linear phase or in the nonlinear phase, but the streak mode and the 3-D travelling modes undergo drastic amplification, as shown in figure 7(a). The base flow for the nonlinear analysis is chosen as the time- and spanwise-averaged mean flow, which includes the Blasius solution and the MFD,

$\tilde {\phi }_{10}$ evolves either in the linear phase or in the nonlinear phase, but the streak mode and the 3-D travelling modes undergo drastic amplification, as shown in figure 7(a). The base flow for the nonlinear analysis is chosen as the time- and spanwise-averaged mean flow, which includes the Blasius solution and the MFD,

In the early nonlinear phase, the MFD is mainly driven by the fundamental mode, which also acts back on the fundamental mode to lead to its saturation eventually. Since the streamwise length scale of the mean flow is much greater than the Mack-mode wavelength, the non-parallelism of the base flow is negligible in the following analysis.

From the linear stability analysis based on the parallel mean flow (4.3) at a chosen streamwise location ![]() $x$, we find that the growth rate of the fundamental Mack mode is much smaller than its wavenumber. We can express the perturbation profiles

$x$, we find that the growth rate of the fundamental Mack mode is much smaller than its wavenumber. We can express the perturbation profiles ![]() $\tilde {\phi }_{10}$ in terms of

$\tilde {\phi }_{10}$ in terms of

where the streamwise wavenumber ![]() $\alpha$ is almost real and

$\alpha$ is almost real and ![]() $O(1)$, the frequency

$O(1)$, the frequency ![]() $\omega _0$ is also taken to be

$\omega _0$ is also taken to be ![]() $O(1)$ and

$O(1)$ and ![]() $\hat \phi _{10}$ is the eigenfunction of the fundamental mode. Asymptotic analyses, as done by Dong et al. (Reference Dong, Liu and Wu2020) and Dong & Zhao (Reference Dong and Zhao2021), showed that the Mack mode shows a double-deck structure in the high-

$\hat \phi _{10}$ is the eigenfunction of the fundamental mode. Asymptotic analyses, as done by Dong et al. (Reference Dong, Liu and Wu2020) and Dong & Zhao (Reference Dong and Zhao2021), showed that the Mack mode shows a double-deck structure in the high-![]() $R$ approximation, namely, a main layer where

$R$ approximation, namely, a main layer where ![]() $y=O(1)$ and a viscous Stokes layer where

$y=O(1)$ and a viscous Stokes layer where ![]() $y=O(R^{-1/2})$.

$y=O(R^{-1/2})$.

The eigenfunction of the fundamental mode ![]() $\hat {\varphi }_{10} = (\hat {v}_{10},\hat {p}_{10})$ satisfies the Rayleigh equation in the main layer based on the mean flow

$\hat {\varphi }_{10} = (\hat {v}_{10},\hat {p}_{10})$ satisfies the Rayleigh equation in the main layer based on the mean flow ![]() $(\bar U, \bar T)$,

$(\bar U, \bar T)$,

where

with ![]() $S_0 = \textrm {i} \alpha (\bar U -c)$ and

$S_0 = \textrm {i} \alpha (\bar U -c)$ and ![]() $c \equiv \omega /\alpha$. The boundary conditions read

$c \equiv \omega /\alpha$. The boundary conditions read

Such a linear, homogeneous system leads to an eigenvalue problem. For a spatial mode, the frequency ![]() $\omega$ is given to be real, and following the numerical method as used by Dong et al. (Reference Dong, Liu and Wu2020), Dong & Zhao (Reference Dong and Zhao2021) and Zhao & Dong (Reference Zhao and Dong2022), we can calculate the eigenvalue

$\omega$ is given to be real, and following the numerical method as used by Dong et al. (Reference Dong, Liu and Wu2020), Dong & Zhao (Reference Dong and Zhao2021) and Zhao & Dong (Reference Zhao and Dong2022), we can calculate the eigenvalue ![]() $\alpha =\alpha _r+\textrm {i} \alpha _i$

$\alpha =\alpha _r+\textrm {i} \alpha _i$ ![]() $(|\alpha _i| \ll |\alpha _r|)$ and the eigenfunctions. If, for a particular

$(|\alpha _i| \ll |\alpha _r|)$ and the eigenfunctions. If, for a particular ![]() $\omega$, the Mack mode is neutral, i.e.

$\omega$, the Mack mode is neutral, i.e. ![]() $\alpha _i=0$, then the system (4.5) becomes singular, and a critical layer around the location where

$\alpha _i=0$, then the system (4.5) becomes singular, and a critical layer around the location where ![]() $\bar {U}=\omega /\alpha$ appears. For a linear critical layer, the leading-order balance in this layer is between the inertial and viscous terms, and in the numerical process, the solution can be obtained by detouring the integrating path around the critical point, as illustrated by Schmid & Henningson (Reference Schmid and Henningson2001, pp. 44–45); an example can be found from Dong et al. (Reference Dong, Liu and Wu2020). Other perturbation quantities such as