No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 February 2011

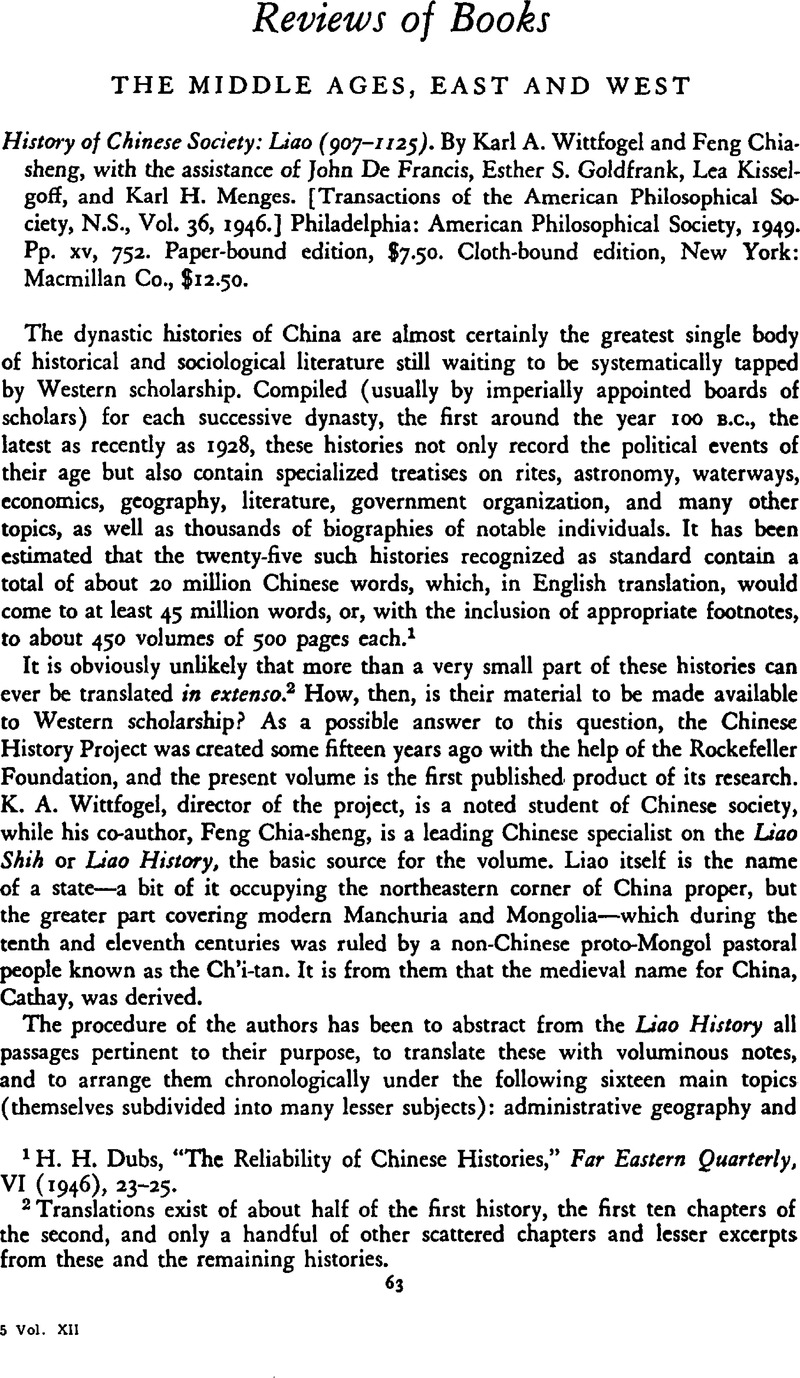

1 Dubs, H. H., “The Reliability of Chinese Histories,” Far Eastern Quarterly, VI (1946), 23–25.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

2 Translations exist of about half of the first history, the first ten chapters of the second, and only a handful of other scattered chapters and lesser excerpts from these and the remaining histories.

3 It occupies 117 of the total of 7,949 pages for all twenty-five histories in the continuously paginated Kʼai-ming edition.

4 One of the most important sections in the volume, for example, is that (pp. 456–63) in which the yin system is described, whereby persons could acquire public office without undergoing the civil-service examinations. Less than two of the seven pages of this discussion are devoted to the Liao period itself; the remainder deal with the system as it operated under other dynasties. In this connection it is peculiar that the authors make no reference to the important article by Kracke, E. A. Jr., “Family vs. Merit in Chinese Civil Service Examinations under the Empire,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, X (1947), 103–23CrossRefGoogle Scholar, which, though treating the same subject, arrives at somewhat different conclusions.