No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

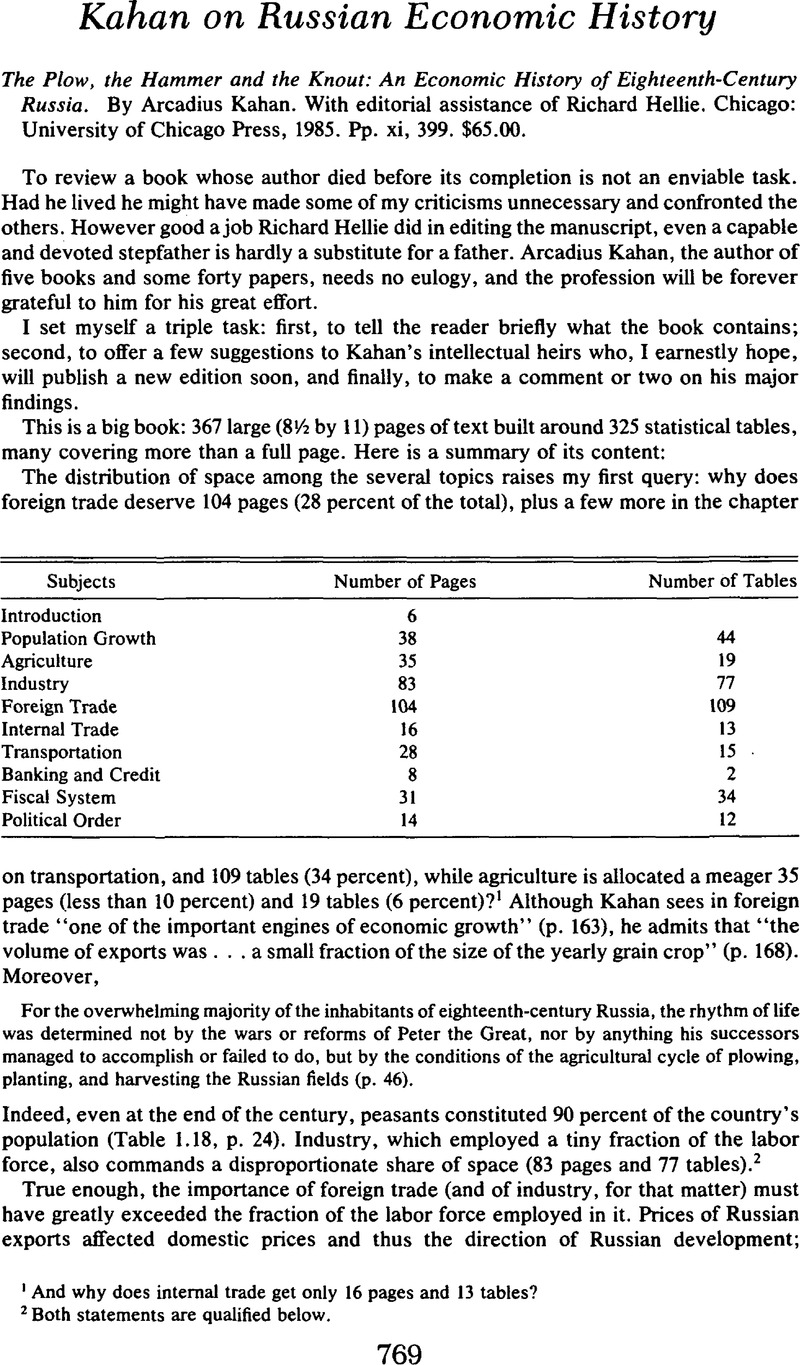

Kahan on Russian Economic History

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 March 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Economic History Association 1987

References

2 And why does internal trade get only 16 pages and 13 tables

2 Both statements are qualified below.Google Scholar

3 See, for instance, Indova, E. I., Krepostnoe khoziaistvo v nachale XIX veka po materialam votchinnogo arkhiva Vorontsovykh [The serf economy at the beginning of the nineteenth century according to the materials in the patrinonial archives of the Vorontsov family] (Moscow, 1955), and several other publications by the same author listed in Kahan's bibliography.Google Scholar

4 Serfs and serfdom are discussed in many parts of the book.Google Scholar

5 The book does contain a number of tables of marginal interest.Google Scholar

6 Blum, Jerome, Lord and Peasant in Russia from the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century (Princeton, 1961).Google Scholar

7 The foreign trade statistics could be checked against the corresponding records of Russia's trading partners, but it is not an easy task.Google Scholar

8 This statement is qualified below.Google Scholar

9 He must have meant of“Net Revenues.”As a fraction of expenditures, the military absorbed less than 50 percent in 17 years out of 34. See Table 8.16, p. 337.Google Scholar

10 A similar question should be asked about Sergei Witte's activity at the end of the nineteenth century.Google Scholar

11 Kliuchevskii, V., Kurs russkoi istorii [A course of Russian history] (Moscow, 1937), vol. 5, pp. 163–64.Google Scholar

12 To add a bit more confusion to this question, let me mention that Vernadsky claimed that in the Kievan days (around 1200) the urban population of the Russian state had comprised 13 percent of the total. It was not to reach this magnitude again until the end of the nineteenth century. See Vernadsky, George, Kievan Russia (New Haven, 1948), p. 105. Whom and what shall we believe?Google Scholar

13 Judging by the quality of Kahan's infrequent excursions into the analytical field, the first hypothesis is more likely than the second.Google Scholar