INTRODUCTION

There is a large body of literature in economics and political science that has tried to establish the relationship between foreign direct investment (FDI) and a host country's governance. The bulk of the research has focused on identifying characteristics of the latter that are deemed conducive to attracting FDI. There is broad agreement that certain governance traits often associated with democratic institutions, such as transparency and effective rule of law, help lure foreign firms to invest by reducing uncertainty in policies and other political risks such as illegal expropriation (Li and Resnick Reference Li and Resnick2003; Jensen Reference Jensen2006; Staats and Biglaiser Reference Staats and Biglaiser2012). In this article, however, I reverse the question and ask what effects FDI has on the host country's governance, an aspect that has received relatively little attention thus far.

Of those studies that analyze the relationship from this perspective, the majority claim that FDI improves governance in a host state. One strand of arguments points to the positive force of change unleashed by enhanced competition associated with FDI inflows; the entry of foreign firms into previously restricted industries breaks up monopolies and brings more competition to the industries. As a result, rents dissipate and so do bribery opportunities—and, as corruption declines, governance improves (Treisman Reference Treisman2007). Moreover, as governments are in competition for attracting FDI, they strive to offer potential foreign investors the best deal they can afford, including not only various financial incentives (Li Reference Li2006), but also a set of horizontal policies aimed at improving governance practices such as enhancing transparency, strengthening rule of law, and improving the efficiency of public service delivery. This then leads to a dynamic that is known as a “race to the top” in standards (Sandholtz and Gray Reference Sandholtz and Gray2003). In a similar vein, another optimistic view suggests that there is a diffusion of good governance into developing areas, in which multinational corporations (MNCs) from developed countries, acting as agents of change, bring in higher standards in business norms and practices to the host country (Gerring and Thacker Reference Gerring and Thacker2005). In the context of transition economies that have pursued FDI-led, export-oriented economic development, such as China and Vietnam, many studies have empirically vindicated those positive views (e.g., for China, Naughton Reference Naughton2006; Lee and Lio Reference Lee and Lio2016; for Vietnam, Malesky Reference Malesky, Tria and Marr2004; Jandl Reference Jandl2013).

In this article, I offer a more nuanced view by analyzing the effects of FDI on governance—the level of corruption in Vietnam subnationally. While concurring that, at first, FDI engenders a positive feedback loop enhancing good governance and reducing corruption in FDI-recipient provinces, I argue that once FDI begins to flood in, different dynamics kick in, leading to a greater prevalence of corruption in provinces with high FDI inflows.

Initially, FDI generates incentives as well as resources for provincial leaders to improve governance and limit their own predatory instincts so that their provinces can continue to attract FDI. However, as more FDI flows in, significant circumstantial changes—such as a massive influx of migrants and the formation of industrial clusters—occur. While the former puts increasing strain on the local government's resources available for improving governance, the latter lessens the competitive pressure, thereby decreasing the incentives for local officials to provide a good governance environment. At the same time, with a continued flood of FDI, local officials find themselves with greater opportunities for seeking rents as well as with the enhanced ability to pursue them. As provincial authorities wield significant powers in economic management, such as registration of foreign investment projects and issuance of land-use rights certificates, FDI inflows and the associated economic growth facilitate the “commercialization of the state,” or the tendency to use public authority for personal gains in market transactions (Pincus Reference Pincus2015). In the meantime, the capacity of FDI-rich provinces to generate revenues grows immensely, which tilts their relative power vis-à-vis the center in their favor (Malesky Reference Malesky2008). Then the central government's drives to reform local governance and keep corruption in check fail to reach and constrain those powerful, FDI-rich provinces, opening the way for local elites to capture the government and engage in abuses of power. The eventual outcome is a general deterioration in corruption control in high-FDI provinces.

The sober look at the role FDI plays in host state governance presented in this article is in line with a growing number of pessimistic views of MNCs and foreign firms operating in developing countries, including China and Vietnam, suggesting that FDI leads to more, not less, corruption in the host state (Robertson and Watson Reference Robertson and Watson2004; Bellos and Subasat Reference Bellos and Subasat2012; Malesky, Gueorguiev, and Jensen Reference Malesky, Gueorguiev and Jensen2015; Pinto and Zhu Reference Pinto and Zhu2016; Zhu Reference Zhu2017). This critical take on the relationship between FDI and governance has a long intellectual history. Dependency theory in the 1960s and 1970s attributed the prevalence of authoritarianism in relatively industrialized developing economies to the presence of MNCs in those countries. In this account, MNCs, a part of the formidable “triple alliance” formed with the host state and local elites, were heavily implicated in rent-seeking activities at the expense of the host society at large (Evans Reference Evans1979). Dashed hopes for political development in those regions, this line of reasoning argued, was a casualty.

My argument that FDI empowers local elites in a way that allows them to use public authority to enrich themselves at the expense of local governance also relates to broader literatures on the relationship between globalization and decentralization and on the latter's impact on governance. Integration into the world economy through trade and FDI creates winners and losers across regions within national boundaries, which unleashes a centrifugal force that brings about de facto decentralization and possibly even attempts at secession (Alesina and Spolaore Reference Alesina and Spolaore1997; Echeverri-Gent Reference Echeverri-Gent1998; Hiscox Reference Hiscox, Kahler and Lake2003; Malesky 2008). A fragmented state system, then, could not only result in an erosion of the center's state capacity (Hao and Lin Reference Hao and Lin1994), but could also create perverse incentives for local leaders, leading either to excessive investments or to insufficient efforts for development (Echeverri-Gent Reference Echeverri-Gent2000). Decentralization may could also worsen local governance, as it accords local elites autonomy and, in some cases, a monopoly on power (Bardhan Reference Bardhan2002; Campos and Heilman Reference Campos and Heilman2005; Acemoglu, Reed, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Tristan and Robinson2014). Therefore, with decentralization, public service delivery deteriorates (Malesky, Nguyen, and Tran Reference Malesky, Nguyen and Tran2014) and properties become more susceptible to confiscation by local elites (Mattingly Reference Mattingly2016).

This article also contributes to the literature on partial reform syndrome in transition economies, a phenomenon in which economic reform is blocked by short-term winners from early reforms as more comprehensive reform measures would threaten their lucrative positions (Murphy, Shliefer, and Vishny Reference Murphy, Shliefer and Vishny1992; Hellman Reference Hellman1998). While the partial reform equilibrium is used to depict a stalemated state of reform at the national level, this article suggests that the syndrome may manifest itself at the subnational level, not just in the sense that provinces dominated by interests of early winners try to obstruct further reform at the national level (Malesky Reference Malesky2009), but also in the sense that those in power in early reform provinces, while securing gains from early market liberalization, obstinately refuse to allow deepened governance reform in their provinces to break up their monopolistic grip on the partially reformed, commercialized local state authority.

There are further reasons I analyze the effects of FDI on subnational-level corruption in Vietnam. First, the regional distribution of FDI within a country in most cases is uneven and highly concentrated, so that its effects on politics cannot be properly understood without a disaggregated analysis of subnational units. Second, the “large-n within a single country” research design has multiple merits in controlling for unobservable national characteristics such as culture and identity, in leveraging in-depth knowledge of the case at hand, and in combining a statistical analysis with the more qualitatively oriented case study.

Finally, since the late 1980s Vietnam has espoused market-oriented reforms centered on FDI-driven economic growth, which has been a province-led process to a significant degree. Some provinces, mostly in the South, have led the way by pushing market reform measures even beyond the legal limits, and those policies that proved successful were then adopted by the Communist Party at the center (Fforde and de Vylder Reference Fforde and de Vylder1996). Over time provinces have been granted an increasing amount of power in economic policymaking, including full authority to license foreign investment projects and to plan and implement industrial zones (Jandl Reference Jandl2013, 89). This, along with a formal government structure divided into as many as 63 provinces with significant variations across them in terms of both inflows of FDI and local governance, makes Vietnam an excellent case for examining the effects of FDI on corruption at the provincial level.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The next section presents a brief history of FDI in Vietnam and describes the regional pattern of FDI domestically to set the stage for an analysis of its effects on corruption at the provincial level. In the section that follows, I develop my main argument explaining that not only do the availability of resources and the incentives to improve governance and reduce corruption vary with differing levels of FDI across provinces, but so do the opportunities and ability to seek rents. Then, I present a series of regression analyses that quantitatively test the findings from my qualitative research suggesting that provincial FDI inflows have a non-linear impact on control of corruption. The last section concludes the article.

FDI IN VIETNAM

Vietnam's economic growth in the period of reforms since the death of Le Duan in 1986, after 26 years as General Secretary, has been mainly driven by FDI (Tran Reference Tran, Pham and Nguyen2007). During the half decade after these doi moi (renovation) policies were first announced at the 6th National Party Congress, FDI inflows remained modest, with a total of just US$168 million, and those investments mostly went into oil and gas projects. The 1990s, however, saw FDI inflows take off, bringing the total accumulated foreign capital to US$8.6 billion within a decade (Malesky Reference Malesky2008). In that period much of the investment was in export-oriented sectors such as textiles and clothes, food processing, and electronics (Mai Reference Mai1998). The significance of foreign firms in Vietnam's economy has since grown enormously, accounting for more than half the total exports and about 40 percent of industrial output by 2010 (GSO 2010). In 2015 alone, US$12 billion, or about 6 percent of annual GDP, flowed into Vietnam in the form of FDI. During the three decades since reforms began, the country's per capita GDP, measured by purchasing power, has grown six times in real terms (World Bank 2017).

The distribution of FDI inflows across provinces over the decades has been markedly skewed. As Table 1 indicates, the top five FDI-recipient provinces together account for a substantial share of total FDI in Vietnam as of 2016: 51.5 percent in terms of accumulated FDI stock and as high as 70.9 percent in terms of the number of FDI projects. The share of the top five provinces is somewhat lower when the amount of FDI stock is scaled by population, but it is still quite significant at 41.1 percent.Footnote 1 This is in stark contrast with the provinces at the bottom of the scale. The respective numbers for the bottom five range from 0.02 percent to 0.1 percent. The province of Dien Bien is an extreme case; located in the Northern Uplands and bordering Laos and China, the province has hosted thus far only one FDI project with registered capital of a meager US$100,000, which is only one fortieth the amount that the second lowest FDI-recipient province has received.

Table 1 Top and Bottom Five FDI-Recipient Provinces as of 2016

Note: Data from General Statistics Office (2016).

This heavily concentrated pattern of FDI inflows has much to do with the locational advantages that the two most important economic centers of Vietnam present. Ho Chi Minh City in the South and Hanoi in the North were, from the beginning, in a much better position to attract foreign investors, with higher concentrations of existing industries, better infrastructure networks, easier access to ports and airports, superior public administrative and financial services, and greater populations. Provinces adjacent to or near the two economic centers have also been able to leverage their locational advantages from being close to an industrial hub in competing for FDI. The map in Figure 1 shows this geographic clustering of high-FDI recipient provinces surrounding both Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi. In the South, it is into those provinces north and east of Ho Chi Minh City that the most FDI has flowed. In the North, there has emerged an industrial corridor connecting Hanoi and the port city of Hai Phong via Bac Ninh and Hai Duong.

Figure 1 The geographic distribution of FDI stocks in Vietnam (2016)

That said, geography alone cannot explain all of the variation in FDI stocks across provinces. For instance, of the provinces located in the immediate vicinity of Ho Chi Minh City, Tay Ninh and Long An have hosted a much smaller number of foreign firms than Binh Duong and Dong Nai, by about one tenth and one fourth, respectively. This difference in FDI performance can be accounted for at least in part by government policies at the provincial level. The sea change seen in Binh Duong during the past two decades, in which a predominantly rural area has been transformed into a dynamic industrial powerhouse with massive inflows of FDI, is worth noting in this regard. The provincial government of Binh Duong has been much praised for its proactive and strategic moves in attracting foreign investors. Highly committed to industrial development, its People's Committee and Department of Planning and Investment (DPI), in particular, spearheaded economic governance reforms to provide foreign investors with a business-friendly environment including the adoption of such innovations as the one-stop shop policy. The recent rise of Da Nang as a key investment center despite its distant location from both Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi offers another example of the important role a provincial government can play in attracting FDI. Having licensed more than 370 foreign projects, Da Nang has the ninth most foreign invested firms, in large part due to its superb performance in modernizing public administrative organization and procedures.

FDI AND PROVINCIAL GOVERNANCE IN VIETNAM

In this section I develop an argument, based on in-depth interviews conducted during field work in 2018Footnote 2 and official statistics, as well as a survey of the relevant secondary sources, that FDI is associated in a non-linear fashion with the provincial corruption level. FDI inflows increase a recipient province's resources and incentives to improve governance and reduce corruption; at the same time, they provide local leaders with increased opportunities and abilities for rent-seeking and corruption. However, the patterns of change in these benefits and drawbacks vary. The former two positive factors—resources and incentives for governance reform—at first increase quickly with FDI inflows, but their pace of increase slows as the amount of FDI inflows grows higher. On the other hand, the latter two—opportunities for local leaders to seek rents as well as their ability to pursue them—grow at an increasing rate with additional increases in FDI. As a result, the overall pattern that has emerged is that control of corruption has tended to improve with FDI inflows initially and then to deteriorate as more FDI has flowed in.

INITIAL FDI INFLOWS AND DECLINING CORRUPTION

Initially, inflows of FDI create a virtuous cycle with good provincial governance. As noted above, some provinces with locational advantages are better positioned to attract FDI. This then provides local leaders with both the resources and the incentives to further improve their investment environment, including improvements in local governance, in order to stay ahead of the competition for FDI.

First, FDI generates industrial activities in the recipient area, creating jobs and helping promote local private business. Increased fiscal decentralization has meant that those provinces with large inflows of FDI have been able to raise their own revenue from various taxes, fees, and user charges that arise from FDI-led economic activities (VCCI 2009, xv). Fiscal decentralization in Vietnam began with the approval of the 1996 State Budget Law, which defined the rights and responsibilities regarding revenues and expenditures of the central and local governments. The revised 2002 State Budget Law has furthered fiscal decentralization by strengthening the discretion of provincial governments (Uchimura and Kono Reference Uchimura, Kono and Uchimura2012, 101). In some cases, provinces, particularly those with the capacity to generate substantial revenue, have been able to exercise autonomy in expenditure decisions to a greater degree than the Law actually provides for (Nguyen-Hoang and Schroeder Reference Nguyen-Hoang and Schroeder2010, 698).

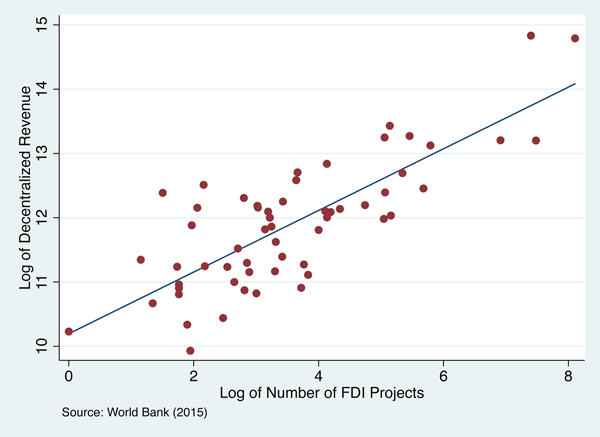

In Vietnam, FDI has contributed to provincial revenues in a number of ways. Article 32 (1) of the 2002 Law specifies the sources of revenue that are fully dedicated to provinces; they include, among other things, non-oil natural resources, land rents, taxes on land and housing, license taxes, taxes on the transfer of land use rights, registration fees, and other fees and charges, each of which tends to be positively impacted by FDI (Nguyen-Hoang and Schroeder Reference Nguyen-Hoang and Schroeder2010, 702). In addition, according to Article 30 (2), provinces are entitled to retain fully or partially revenues of certain types that are to be shared with the central government, including those from value added taxes, corporate income taxes (except for enterprises with uniform accounting), personal income taxes, and special consumption taxes.Footnote 3 Again, each of these tax bases expands, thanks to increased FDI, directly through the corporate income tax, but more importantly indirectly through job creation and the growth of income and consumption.Footnote 4 Indeed, as Figure 2 shows, there is a very strong correlation between FDI and provincial decentralized revenue, the latter being calculated as the sum of the above two revenue types—one that is fully dedicated to provinces and one that is retained fully or partially to provinces (World Bank 2015, 96). Both FDI and decentralized revenue are averaged between 2006 and 2011 and logged, and the correlation coefficient of the two is 0.79. If the raw, instead of logged, numbers are used, the correlation is even stronger with the coefficient being 0.86.

Figure 2 The correlation between FDI and decentralized revenue

The revenue thus generated can be used to boost a local government's fiscal capacity to raise public administrative quality—providing better access to information, modernizing bureaucratic procedures, improving bureaucrats’ capacity, providing higher-quality public services, etc. Provinces with stronger fiscal capacity are also in a better position to support citizen engagement in local politics. The local governments in those provinces can better inform their citizens of their rights accorded by laws and provide them with more administrative support that facilitates citizen participation in local elections and in meeting with local leaders. Both much improved public administration procedures and more active citizen participation in local politics have contributed greatly to reducing corruption at the provincial level (Kim Reference Kim2018, 133).

Second, just as available resources increase with FDI inflows, so do a provincial government's incentives to provide good governance. The revenue sources—and bribery opportunities—generated by FDI are what initially give a provincial government a strong incentive to improve governance. First, local leaders can gain power and prestige as well as accumulate personal wealth from the FDI-created revenue and rents; and, second, at least by the early 2000s, leaders of local governments seemed to well understand that to attract foreign investors to their province it was imperative to reform the province's governance. Throughout the 1990s they learned that potential foreign investors considered various aspects of the governance environment in deciding where to invest. One of the processes by which provincial officials learned about what foreign investors wanted in regards to governance issues was conferences with foreign investors. For example, at the “Vietnam Business Forum,” foreign investors presented a list of problems they had faced in dealing with government officials in the province where they had businesses and evaluated how well the government had responded to solve those problems. Publicly available, this information made local officials aware of what foreign investors looked for in local governance as well as of “their reputations among investor groups” (Malesky Reference Malesky, Tria and Marr2004, 289–290).

Thus a virtuous cycle set in early on. Gains accrued to local leaders whose provinces had made themselves early winners in hosting FDI. This provided strong incentives to spearhead various reform measures to cut entry and transaction costs significantly for foreigners to set up and run businesses, including measures that were aimed at providing tax benefits, cheaper land, better and easier access to information, and reliable dispute resolution procedures (Malesky Reference Malesky, Tria and Marr2004, 289–290). They then were able to host a growing number of FDI projects in their provinces thanks to the improved, business-friendly, governance environment. Those least-able, relatively remote provinces, however, have been left out of this process, receiving little foreign capital inflows, and they thus lack not only the resources to improve infrastructure but also the incentives to “stay fit” in terms of governance. As a result, more investment has come to those early reformers. In this way, investment has begotten more investment, and local governance in FDI-recipient provinces has improved in the process; so has control of corruption in those provinces.

CONTINUED INFLOWS OF FDI AND INCREASING CORRUPTION

Continued inflows of FDI, however, generate countervailing forces that limit the two beneficial effects—resources and incentives for better governance. At the same time, FDI inflows lead to a worsening of corruption by offering local leaders growing opportunities and abilities for rent-seeking.

Positive effects of FDI diminish as more FDI flows in

While revenues continue to rise—and rise faster—with more FDI inflows, the provincial government's fiscal capacity to improve governance cannot. A rapid and significant expansion of the local population in the industrial centers where FDI is highly concentrated presents the local government with a daunting challenge to meet demands for public services. In particular, a massive influx of migrants from other parts of the country impedes the local government's capacity to effectively deal with a number of governance issues such as citizen participation, vertical accountability, and transparency, not to mention public service delivery (Kim Reference Kim2018, 134–138).

Given regional patterns of employment opportunities, internal migration has been on the rise in Vietnam and the rates of migration have varied greatly across provinces. Economic centers with a large number of industrial zones such as Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi have had very high in-migration rates (Nguyen-Hoang and McPeak Reference Nguyen-Hoang and McPeak2010, 479; Anh et al. Reference Anh, Vu, Bassirou and Esther2012). The 2004 Vietnam Migration Survey revealed that more than 30 percent of Ho Chi Minh City's residents were migrants from other provinces (Huy and Khoi Reference Huy, Doan Khoi, Stewart and Coclanis2011, 126). Some provinces in the vicinity of the economic centers with rapid rates of industrial growth have also received a large number of migrants. A notable example in this regard is Binh Duong. Over roughly the past decade it has had the highest rates of in-migration (the number of in-migrants out of 1,000); the rates have been two to four times as high as those of the second highest provinces. Most of the migrants were from the Mekong Delta, a region that has seen a very large net population loss since the 1990s along with the Central Coast region (Nguyen-Hoang and McPeak Reference Nguyen-Hoang and McPeak2010, 479). More than one in seven out-migrants from the Mekong Delta called Binh Duong their new home (Huy and Khoi Reference Huy, Doan Khoi, Stewart and Coclanis2011, 126). Interviews with managers of foreign firms located in different provinces confirmed this. Asked about the ease with which the firm hires workers, while those in Binh Duong said that it was never an issue,Footnote 5 those in the Mekong Delta region, such as Tien Giang and Ben Tre, said that the availability of labor remained a major concern.Footnote 6 A manager of a bag manufacturing company, which had opened a new factory in Tien Giang four months prior, said that half of the production lines were yet to be filled with workers.Footnote 7

An implication of all of this for provincial governance performance is that FDI inflows and the resulting flows of in-migration have put a disproportionate strain on top FDI-recipient provinces. Studies show that migrants are more likely to be beset with health problems due to “poor general health status, low use of health care services, and lack of knowledge” about health issues, posing a huge challenge to public health authorities (Anh et al. Reference Anh, Vu, Bassirou and Esther2012, 9–10). The provision of adequate housing and public education as well as ensuring access for migrants to local community institutions are also areas of concern for local officials in those FDI-rich, high-migration provinces (Le, Tran, and Nguyen Reference Le, Tran and Thao Nguyen2011, 9–10).

Binh Duong, the province with the highest net migration rate as a result of some of the highest rates of FDI inflows, illustrates the point. Over the past few years, the province has experienced the sharpest decline in governance performance, and its underperformance has been across the board. Residents have expressed a lower level of satisfaction not only with public health services and public schools, but also with regard to other key governance indicators such as citizen participation in local meetings and elections, transparency of information on local budgets and land use plans, and citizens’ ability to hold local authorities accountable through monitoring and interactions. Worst of all is the control of corruption, for which the province had the lowest score of all provinces by 2016. This worsening of provincial governance in Binh Duong has been understood in part as a consequence of “a growing number of migrants … for employment opportunities in expanding industrial zones” (CECODES, VFF-CRT & UNDP 2017, 85). A government official in the province seemed to acknowledge the governance challenges they faced, saying that the province has been making major efforts to improve provincial governance in recent years including embarking on a Smart City initiative.Footnote 8

Similarly, a provincial government's incentives to provide good governance become increasingly weaker with further inflows of FDI. To put it another way, the marginal return to efforts to improve governance on the part of provincial governments diminishes as FDI continues to flow in. Economies of agglomeration mean that more and more firms seek to enter an already established industrial center where they can gain from being close to production networks in their own industries, with benefits arising from knowledge spillovers as well as easy access to factor markets and supply chains (Krugman and Venables Reference Krugman and Venables1995). Foreign firms, in particular, have a tendency to follow in their compatriots’ footsteps in location choices in order to save on the high search costs for starting a business in an unfamiliar and highly uncertain environment, a manifestation of the “liability of foreignness” (Zaheer Reference Zaheer1995; Caves Reference Caves2007). In Vietnam, indeed, it has been found that foreign firms were more likely to enter where there were already many foreign firms operating, especially in the same industry and of the same nationality as theirs (Binh Reference Binh2010; Esiyok and Ugur Reference Esiyok and Ugur2017).

Agglomeration economies therefore have made selective industrial centers “FDI- magnet” areas. This has entailed foreign investors’ discounting the relative importance of local governance in their location choice, which has lessened the incentives for local governments to put additional efforts into improving it. This was confirmed in my interviews with managers of foreign firms near Ho Chi Minh City. Of the factors that were most important in their location choice, easy access to ports and other infrastructure, availability of labor, presence of related industries, wage levels, and land prices were at the top of the list. Surprisingly few even mentioned the governance environment.Footnote 9 This implies that those provinces with the highest FDI concentration have found themselves with the resources that enable officials to engage in rent-seeking behavior but without the discipline that competition for FDI has continued to impose on those less advantaged provinces (Kim Reference Kim2018, 138).

Consistent with this argument, Jandl (Reference Jandl2013, 91) observed that it was “the provinces with middling numbers of investment projects,” rather than the provinces with the lowest or highest numbers, that kept “their entry costs low.” Likewise, with regard to how businesses perceive land security as well as the court system, it was those “mid-ranking provinces in terms of investment” that ranked at the top, outperforming top FDI-receiving provinces in those categories. Jandl (Reference Jandl2013, 93) explained the top group's underperformance relative to the middle group as reminiscent of the paradox of plenty—“the more desirable a province, the more rent can be skimmed off land issues without significantly slowing the flow of investment.”

The contrasting experiences of Ho Chi Minh City and Da Nang illustrate the point. Ho Chi Minh City, as a paramount FDI-magnet area with about 30 percent of all FDI projects, has been able to attract further FDI inflows despite city officials’ lack of efforts at keeping rent-seeking behaviors in check and combatting widespread corruption. In fact, the city has been in a position to be selective in licensing new FDI projects, admitting firms in high-tech sectors and screening out ones in pollution-prone industries, which has likely given local authorities further leeway in seeking rents. Likewise, Binh Duong government officials concurred that recently they have been increasingly selective in providing licenses to more desirable foreign firms as they receive numerous FDI applications each year.Footnote 10 In contrast, Da Nang, located at the center of the country far from both the economic poles, did not emerge as a key foreign investment center until much later. The city's leaders knew that they needed “to work extremely hard on their governance to overcome their geographical disadvantages” (Jandl Reference Jandl2013, 110).

Opportunities for rent-seeking grow as more FDI flows in

The practice of paying “informal charges” (i.e., bribes) is widespread in Vietnam. Both local and foreign firms make unofficial payments to a wide range of authorities involved in business registration, issuance of land-use permits, taxation, customs, and environmental regulation to expedite the process of their requests, to get things done, to avoid penalties, or simply to conform to the prevailing norm. According to a recent survey, when a firm receives a request, any request, from public officials, it is most likely (more than 15 percent of the time) that they ask the firm to pay money or give gifts to them by way of abusing the “power, names, or reputation of their agencies” (World Bank 2012, 40). In many cases, the situation in which a firm is asked to make informal payments is set up by public officials, creating difficulties for the firm; the most common include when the officials “intentionally prolong the time to solve firms’ requests,” do “not explain the requirements clearly but try to catch firms’ mistakes,” and “intentionally impose wrong regulations” (World Bank 2012, 40–41).

Provincial governments exercise a substantial degree of authority and discretion in economic management within their jurisdictions. Provincial People's Committees, in particular, have powers to “investigate, survey, classify and carry out zoning and land-use planning, enforce rules and regulations, carry out registration functions, inspect the land, and resolve land disputes” (Maitland Reference Maitland, Lindsey and Dick2002, 154). Thus an influx of FDI and the economic development that has followed it generate lucrative rents for those in power, and those windfall gains rise with FDI. Furthermore, as foreign-invested firms help generate further economic activities in their localities, opportunities for rents tend to rise still higher. According to a former DPI official in Ho Chi Minh City, rents for government officials are not only taken as bribes, but more importantly take the form of profits from side businesses their family—wife, children, and close relatives—own. Officials earn rents by leveraging their own public authority, such as the power to issue construction permits. Asked the question, “How common is it to run side businesses?” he replied “Almost everyone does that, big or small.”Footnote 11

Land development associated with FDI-induced regional transformation, in particular, has been a major source of rents for local authorities and those with political connections. By the early 2000s, to facilitate the conversion of agricultural land to industrial and residential uses, a system of one-stop shopping for land use rights began to be introduced by provincial governments, in which the local government—for large projects, the provincial, and for small projects, the district government—would “set aside land for conversion, then re-zone it and clear it” so that investors would not have to negotiate with the original owners of the land use rights (Jandl Reference Jandl2013, 91). This “system of government-managed land clearance,” however, generated so much in windfall gains to local elites from the proceeds of buying cheap agricultural land and selling it “at multiple times the purchasing price” that the central government had to prohibit it out of embarrassment of such visibly pervasive corruption (Jandl Reference Jandl2013, 91–92). Yet the problem did not abate, and land administration has remained one of the most corrupt sectors in the eyes of both firms and citizens (World Bank 2012, 38–39). The annual reports of PAPI (Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index), which evaluates aspects of provincial governance including corruption based on national surveys of citizens, have repeatedly pointed out that the payment of bribes for land use rights certificates remains widespread (CECODES, VFF-CRT & UNDP 2017).

The perverse incentives facing local leaders in FDI-rich provinces have been reinforced by foreign investors’ equally perverse behaviors, as evidenced by Malesky, Gueorguiev, and Jensen's (2015, 421) analysis of a survey experiment. It was estimated that foreign firms in Vietnam are nearly two times more likely than local firms to pay bribes in restricted sectors that yield higher rents. This is in line with what a growing number of studies have found beyond Vietnam. Using their superior positions in the market, arising from owning capital, technology, brand power, and marketing skills, foreign firms can further drive out weaker local firms (Blomstrom and Kokko Reference Blomstrom and Kokko1996), lobby the government for raising entry barriers still higher (Dunning Reference Dunning1992), and even create a “rent-sharing chain” with their local suppliers and customers along the vertical linkages (Zhu Reference Zhu2017, 86). That two of the top FDI-recipient provinces, Binh Duong and Hai Phong, are also the top two most corrupt is not a coincidence, as foreign investors themselves have pushed for “more opaque governance” (Malesky Reference Malesky, Tria and Marr2004, 290). “Latecomer investors” in Binh Duong, according to Malesky (Reference Malesky, Tria and Marr2004, 291), would complain that “earlier investors contaminated the investment environment with kickbacks.” In Hai Phong, likewise, paying bribes has become increasingly more prevalent “as the presence of investors has increased” (Malesky Reference Malesky, Tria and Marr2004, 291). When asked the question, “Has your firm paid unofficial money?” the foreign firm managers and bankers interviewed neither confirmed nor denied, but they said that they knew that most firms did.Footnote 12

Corruption is not confined to rent-sharing between public officials and firms; it tends to spill over into broader state-society relations. One key such channel is the appreciated value of holding public office at various levels in a rent-abundant environment. Local officials in FDI-rich provinces, especially those with higher positions and in charge of economic management, such as chairs and vice-chairs of Provincial People's Committees and directors of DPIs, have been in position to enrich themselves and their family members, making it worthwhile to make a lump sum payment for those positions. An anecdote told by a CEO of a consulting firm is illustrative: the position of head of a district police department in Ho Chi Minh City was sold at US$250,000 a few years ago.Footnote 13 Indeed, the selling of office has become one of the most serious forms of corruption during the reform era. It has been widely known that provincial party secretaries could make handsome profits or even fortunes by selling various positions (Vu Reference Vu and London2014, 31). Buying and selling a government job has become so prevalent that it was found in a recent survey to be the top reason citizens paid a large bribe to public officials (World Bank 2012, 52). This is evident from the PAPI surveys as well. Roughly half of respondents have agreed, survey after survey, that bribes were necessary to get a government job (CECODES, VFF-CRT & UNDP 2017).

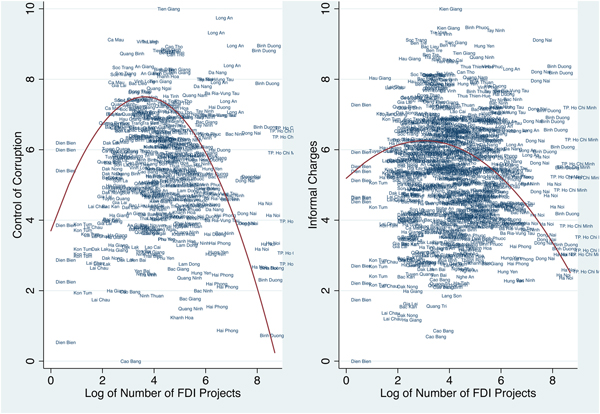

In support of this view, the prevalence of informal charges perceived by firms, as measured in the Provincial Competitiveness Index (PCI), which is based on a survey of a nationally representative sample of firms in all 63 provinces,Footnote 14 tends to go hand in hand with citizen perception of corruption across provinces from PAPI. As Figure 3 reveals, there is a strong correlation between the two, both of which are averaged over the 2011–2016 period.Footnote 15 Provinces where firms paid informal charges to a greater degree tend also to be those where citizens felt that their provincial governments were more corrupt. The correlation coefficient between the two is about 0.51.

Figure 3 The correlation between control of corruption and informal charges

Ability to pursue rents grows as more FDI flows in

Just as opportunities for local officials to gain rents have grown with FDI at an increasing rate, their ability to pursue rents has increased in a parallel manner. As noted above, as a few industrial centers have emerged and grown further with massive inflows of FDI over a couple of decades, the leaders of those powerhouse provinces have gained a substantial degree of autonomy from the central government (Abuza Reference Abuza2002, 131). In the context of deepened fiscal decentralization, as well as the highly uneven distribution of FDI inflows and industrial production across provinces, a small number of high-FDI provinces have been able to generate revenue large enough to gain relative power vis-à-vis the central government. Malesky (Reference Malesky2008, 101) estimated the FDI contribution to revenue for the national and provincial governments. By the early 2000s, for some high-FDI provinces such as Binh Duong and Vinh Phuc, FDI accounted for a quarter of the provincial revenue, while it contributed to about 14 percent of the total national revenue. The center has found itself increasingly more dependent on those surplus-generating provinces for the revenue it needs to transfer to less prosperous provinces.

Interprovincial revenue transfer occurs through two channels. First, there is a list of taxes that are to be shared between the central and local governments. The sharing rate, or the proportion of the shared tax that is to be allocated to local governments, varies from province to province depending on the province's revenue-generating capacity and its expenditure needs. In 2011, for nearly 80 percent of all provinces, the sharing rate was 100 percent, meaning that they retained all taxes that were to be shared with the central government. For the remaining 13 provinces, the sharing rate ranged from 23 percent to 93 percent. For instance, Ho Chi Minh City, whose sharing rate was 23 percent, transferred to the central government 77 percent of the shared tax it generated. This shared tax system was introduced as an explicit mechanism for interprovincial revenue-sharing to address fiscal disparities across provinces (Uchimura and Kono Reference Uchimura, Kono and Uchimura2012, 103).

Second, there are two types of fiscal transfers from the central to local governments, namely, conditional or targeted transfers and unconditional or balancing transfers (Nguyen-Hoang and Schroeder Reference Nguyen-Hoang and Schroeder2010, 703). While both types of transfer were meant to support provinces with insufficient revenue sources to meet their expenditure needs, it is the second type, balancing transfers, that were explicitly formulated to alleviate interprovincial disparities, by considering “remote areas, former revolution bases, minority groups, poor areas, the population size, availability of natural resources, and socioeconomic conditions” (Uchimura and Kono Reference Uchimura, Kono and Uchimura2012, 104). Thus the distribution of balancing transfers closely mirrored that of the sharing rate: in 2011, the 13 most well-to-do provinces received no balancing transfers at all while the rest received varying but significant amounts.

A fiscal transfer system that relies heavily on high-FDI, and hence, surplus-generating provinces, has accorded them great power vis-à-vis the center. At times, those successful provinces even resisted paying taxes to the center (Abuza Reference Abuza2002, 131), and the more successful they are economically, the more defiant the provinces tended to be. There is indeed evidence that the amount of FDI inflow is closely correlated with the number of provinces’ “fence-breaking” instances (Malesky Reference Malesky2008), acts by a provincial government to push for reforms beyond the legal boundaries set by the central government (Fforde and de Vylder Reference Fforde and de Vylder1996). And those fence breakers were not reined in by the center; on the contrary, they were rewarded with political promotions when they brought in economic successes—and revenues (Jandl Reference Jandl2013, 58). The center then used the money as transfer payments to disadvantaged provinces to maintain political stability. It can be said that the center and those FDI-rich provinces have engaged in what Jandl (Reference Jandl2013, 225) called “autonomy-for-transfers” trade.

In the meantime, the central government, despite its own corruption issues, began to realize as early as the mid-1990s that corruption was an increasingly serious problem. Given that the Party's ultimate purpose is to remain in power, the Party must maintain legitimacy in the eyes of the Vietnamese people in order to ensure its survival, but widespread corruption, if unchecked, could undermine the regime's legitimacy, and thus, threaten its stability (Luong Reference Luong2007, 173; Thayer Reference Thayer2009, 48). In 1994, at the Party's mid-term national conference, corruption was identified as one of the “four dangers” facing Vietnam (Thayer Reference Thayer2010, 433). At the Eighth Plenum of the Central Committee held in 1995, corruption again surfaced to the top of the agenda, as General Secretary Do Muoi lamented visibly growing corruption across levels of government (Maitland Reference Maitland, Lindsey and Dick2002, 155). A few months later, the Prime Minister bemoaned that “the state of corruption … jeopardized the renovation process and brought discredit to the Party's leadership and State management” (Goodman Reference Goodman1995, 95–6). Combating corruption has since remained a constant theme at Party Congresses and Plenums and in government decrees and ordinances. In 1998, the Prime Minister noted that “80 percent of [capital] investments were eaten up by excessive administration and corruption” (Sidel Reference Sidel1999, 91). With the problem unabated, the Prime Minister declared combating corruption a top priority in 1999, and in the following year, an anti-corruption campaign was launched (Maitland Reference Maitland, Lindsey and Dick2002, 155).

It was against this backdrop that the government and the Party implemented a series of measures to reform public administration and governance across levels of government with an aim toward combatting corruption. One such measure, a Public Administration Reform (PAR) program, promoted by the UNDP, was initially reluctantly launched by the government in 1994 (Gillespie Reference Gillespie, Lindsey and Dick2002, 168–169). However, by 2001, following a major review of the program, now recast as a Master Program on PAR, the government wholeheartedly embraced it. The key areas of the program were institutional reforms, streamlining organizational structures, and civil service reforms (Painter Reference Painter, Gillespie and Nicholson2005, 267; Thayer Reference Thayer2010, 440; Benedikter Reference Benedikter2016, 12).

The goal of the initiative was to build a bureaucracy that is “accountable, transparent, less prone to corruption, and committed to a clear separation between private and public life” (Benedikter Reference Benedikter2016, 13). Yet the results did not live up to expectations. Even a modest goal of streamlining organizational structures failed quite miserably; the following decade saw the numbers of government units and state officials at subnational levels actually grow. Three new provinces were created and the number of districts and communes increased by 16 percent and 7 percent, respectively, along with corresponding additions to state agencies, party organs, and mass organizations at all levels of government (Malesky Reference Malesky2009, 139; Benedikter Reference Benedikter2016, 22). Improving bureaucratic efficiency and reducing corruption have remained major areas of concern for the Party and the central government (Luong Reference Luong2007, 171). For instance, at the Tenth Party Congress, in 2006, widespread corruption was again singled out as a “major challenge to the legitimacy of the socialist state” (Thayer Reference Thayer2010, 441). An independent evaluation of the Master Program, commissioned by the Asian Development Bank in 2011, also concluded that the program was “less effective” in achieving outcomes (ADB 2011, 5).

The effectiveness of the central government's initiatives to improve governance and control corruption has varied across provinces. The PAPI project was devised to monitor progress on governance reforms at the provincial level. The annual survey results since 2011 have repeatedly revealed that there has been significant cross-province variation in all of the public administration and governance areas. In particular, the center's reform drive has turned out to be less effective for those provinces that are more autonomous and less constrained by the central government. In a sense, leaders of high-FDI provinces have given themselves the freedom to pursue rents when those opportunities have become increasingly more plentiful.

While national leaders at the center seek both economic growth and good governance to remain in power, local leaders’ priorities tend to be less public-minded and more self- serving. According to Malesky (Reference Malesky2008, 101), provincial officials in Vietnam are driven by three motivations: first are “prestige and power,” next, “pecuniary benefits for themselves and related family businesses,” and finally “community interests in providing employment and better living conditions for citizens in their provinces.” Local elites in FDI-rich, and thus, more autonomous provinces have not been effectively constrained by either the central government or local constituencies—their citizens and foreign investors. This lack of constraints on power has opened the way for local elites to capture local governments and engage in abuse of power. The outcome is a general deterioration in local governance in high-FDI provinces—lower citizen participation, weaker accountability, lower transparency, and most importantly, a greater prevalence of corruption.

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

In this section I present results of regression analyses to demonstrate that FDI is positively associated with better control of corruption when it is low, but negatively when it is high.

MAIN RESULTS

As measures of corruption, I use both Control of Corruption from the Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) and Informal Charges from the Provincial Competitiveness Index (PCI). The PAPI is composed of six dimensions, each of which is constructed by combining a number of survey questions. The survey has been administered annually on a national sample of about 1,000 citizens covering all 63 provinces. Control of Corruption measures citizens’ perceptions about how prevalent corruption is in their province based on their experiences. In addition, it comprises participation at local levels, transparency, vertical accountability, public administrative procedures, and public service delivery. The PCI is a measure of economic governance at the provincial level. It is based on a national survey of domestic firms and consists of ten sub-indices, including Informal Charges, which measures firms’ perceptions about and with the practice of paying bribes to government officials. Both corruption measures are constructed such that a higher score indicates a lower level of corruption. To facilitate a direct comparison between the two, I standardized them so that they both vary from zero to ten.

As a measure of FDI, I opt to use the logged number of FDI projects operating in a province in a given year. It is preferable to accumulated FDI stock as, if the latter is used, a certain province (Dien Bien) stands out as an outlier. It is also preferable to per capita FDI stock because conceptually it is the intensity (the amount of FDI or the number of FDI projects) in a locality that brings about its hypothesized effects on a local government's resources, incentives, opportunities, and ability, given the population and other provincial traits, not its amount or number per capita. Nonetheless, when logged accumulated FDI stock or per capita is used in place of the log of the number of FDI projects, the results remain largely unchanged. To capture the non-linear relationship, I include an FDI squared term in the regressions. The FDI measure and the squared term are lagged one year to mitigate the endogeneity problem.

To further address a concern about unobserved heterogeneity, I use, for all the models except for those in Table 5, fixed-effects estimation in which all time-invariant unobservables are controlled for. To account for clustering of observations in 63 provinces as well, I fit the models with robust standard errors adjusted for the clusters. For time-varying control variables, I include the poverty rate and urbanization rate. The former is used to take into account the differing levels of economic development across provinces, and the latter, the share of urban residents, albeit correlated with the former to some extent, is included to account for the mode of interactions based on a contractual relation between bureaucrats on the one hand and citizens and firms on the other. Such contract-based relations are expected to be more prevalent in an urban setting than in a rural one. Finally, as both FDI and corruption (especially measured by Informal Charges) have tended to increase over time, the year is included as a means to de-trend the dependent variable. The main analysis covers 2012 to 2017 for Control of Corruption and 2007 to 2017 for Informal Charges for all 63 provinces. Except for the dependent variables, all the data are taken from the General Statistics Office (GSO 2006–2016).

Table 2 reports the main results: fixed-effects regression results on Control of Corruption in Model (1) and on Informal Charges in Model (2). The first thing to note is that the two corruption measures, despite the differences in what each is meant to capture and to whom survey questions were administered, behave quite similarly across variables. The poverty rate is positively related with both measures of corruption control, although it is significant only in the Informal Charges model. Likewise, the urbanization rate is negatively associated with both corruption control measures. Most of all, the main variable of interest, FDI squared, turns out to be significantly negative in both models.Footnote 16 While it is weakly significant for Control of Corruption at the 0.1 level, it is strongly significant for Informal Charges at the 0.05 level. These results indicate that corruption control improves with low levels of FDI but worsens at higher levels.

Table 2 FDI and Corruption

Note: Fixed-effects cross-sectional time-series regressions with robust standard errors adjusted for 63 clusters in parenthesis. * p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

The estimated effects of the number of FDI projects on the two corruption measures are depicted in Figure 4. When the number of FDI projects is close to the minimum, the estimated score of Control of Corruption is 3.7, a value about one standard deviation (1.9) below the mean, which is 5.6. The corruption control score improves with a growing number of FDI projects reaching the apex near 7.5, which is about one standard deviation above the mean, when the number of FDI projects operating is about 38 (its logged value is about 3.64). It then declines with more FDI projects, and when the number of FDI projects reaches the maximum, it is projected to come down to 0.24, a dramatic decline of more than 7 points (on the zero to ten scale). Likewise, the estimated score for Informal Charges increases first and then declines with the number of FDI projects, albeit in a less dramatic way. The score begins at 5.2 with the smallest number of FDI projects and grows until it reaches 6.3 when the number of FDI projects is about 20 (its logged value is 3.02). Then it drops to about 2.5, a decline from the highest score of nearly 3.5 times the standard deviation.

Figure 4 Predicted values of control of corruption and informal charges

ROBUSTNESS TESTS

I now present the results of robustness tests to give the findings greater credibility. First, I employ two additional model specifications, one that uses a first-differenced dependent variable and another that uses a logged dependent variable. These model specifications are designed to test alternative accounts of the observed inverted-U pattern. For instance, such a pattern may result from the fact that some governance reform tasks, primarily those that involve state retrenchment, are easier to accomplish than those that require institution- and capacity-building. If that is the case, it may be that early reformers, those provinces that have achieved easy reform tasks earlier than others, once scored high in governance indices but then experienced a stagnation or even a decline in the scores as they moved on to more demanding tasks. In the meantime, late-comer provinces caught up to or even outperformed those early reformers by embarking on the easy phase of governance reform. Under this scenario, then, the inverted-U pattern in the level of corruption control may have less to do with an increase in FDI than with the presence of a virtual upper bound in the governance score. If the change in the score, not just its level, is also found to be systematically associated with FDI in the same, curvilinear manner as before, one can have more confidence in the earlier findings.

The first-differenced model, in which the year-to-year change in Control of Corruption or in Informal Charges is regressed on the FDI measure, estimates the latter's long-run effects on the change in the dependent variable. The second model, in which the logged dependent variable is used, yields the estimated percent change in the dependent variable with a percent increase in the number of FDI projects, given that the latter is also logged. Table 3 presents the results. In the first-differenced models, similar to the main models in Table 2, for both Control of Corruption and Informal Charges, FDI squared is signed negative and statistically significant at least at the 0.10 level. In the logged dependent variable models, the squared term continues to be highly significant for Informal Charges while it falls just short of significance for Control of Corruption with its p-value of 0.103. Taken together, the results show that the size of increase in corruption control grows with FDI first and then declines after FDI inflows become larger, confirming that the observed curvilinear pattern in the level of corruption is well accounted for by an increase in the number of FDI projects.

Table 3 FDI and Changes in Corruption

Note: Fixed-effects cross-sectional time-series regressions with robust standard errors adjusted for 63 clusters in parenthesis. * p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

Second, fixed effects estimation is a rigorous model choice for pooled time-series data. Yet it is far from perfect; one cannot rule out the endogeneity problem that results from unmeasured time-varying factors. Thus, following McCaig's (Reference McCaig2011) approach, in which he uses the 2001 US–Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement as an exogenous shock, I augment the rigor of the fixed effects models with an additional test incorporating an interrupted time series design by taking advantage of the surge in FDI inflows upon Vietnam's accession to the WTO in 2007, an exogenous shock in the amounts of FDI to Vietnamese provinces (Robinson, McNulty, and Krasno Reference Robinson, McNulty and Krasno2009, 347).Footnote 17 To get cross-province variation, I use the logged minimum distance from Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi, or Da Nang as an instrument for FDI inflows. The correlation coefficient of the two is about -0.76; the farther away a province is from any of the three cities, the less FDI has flowed into the province. Then I create interaction variables between the distance and a year dummy that indicates those periods after the FDI surge, which shows up in the data from 2008–2010. Since it is hard to pinpoint the timing when the effects of the surge on provincial governance began to materialize, I employ four year dummies, “Since 2009” through “Since 2012.” For instance, Since 2009 is an indicator that takes one if the year is 2009 or after, and zero otherwise.

The year dummy itself is expected to take a negative sign reflecting the negative impact of the surge in FDI on corruption control when the distance is zero. Yet the corruption-worsening effects of the FDI surge must be less pronounced in provinces that are located farther away from the three cities, which the interaction variable (Logged distance X Since 2009) is meant to capture, and its estimated coefficient must be greater than zero. Since Control of Corruption from PAPI is unavailable for those early years, I could use only Informal Charges for the test. Table 4 reports the results. All the year dummies are signed negative, and all but one (Since 2011) are significant at least at the 0.1 level. The results for the interaction terms, too, are as expected. For all the years, they are signed positive and, for Since 2010 and Since 2012, significant at the 0.1 level. The results for Since 2012 prove especially strong for both the year dummy and the interaction term, probably reflecting the time lag between the surge and its effects on corruption. The results thus give greater confidence to the argument that “too much” FDI causes the increase in the level of corruption.

Table 4 Surge of FDI Inflows and Informal Charges

Note: Fixed-effects cross-sectional time-series regressions with robust standard errors adjusted for 63 clusters in parenthesis. * p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

Finally, I test another empirical implication of the theory. An initial increase in FDI improves corruption control; yet continued FDI inflows beyond a certain level make corruption more severe and widespread. Note that it is the corruption level experienced and perceived by firms as well as citizens that is influenced by an increase in FDI. However, given that FDI has kept flowing into some of those high-FDI provinces despite the fact that it is precisely in those provinces that corruption has become so pervasively experienced, the corruption level experienced by foreign firms is likely to diverge from that experienced by domestic firms (and citizens). It can be argued that foreign firms’ perception of corruption in those high-FDI provinces should improve or at least stay intact. For, otherwise, FDI inflows would not have continued to be so strong in those corruption-prone provinces perceived by foreign firms as such. I exploit the 2010–2011 PCI datasets, which include surveys of not only domestic firms (regular PCI) but also foreign firms (PCI-FDI) sampled from all the provinces. In those two-year datasets, there are three questions related to the informal charges sub-dimension that are common in both surveys of domestic and foreign firms. Using the same set of questions makes it possible to directly compare corruption perceptions of the two types of firms. For the reason stated above, I expect the same inverted-U pattern to be found only in the regular PCI, but not in the PCI-FDI.Footnote 18

The results are reported in Table 5. Models (1) and (2) are for domestic firms, and Models (3) and (4) for foreign firms. For both types of firms, fixed-effects estimations do not yield significant results due in part to the short time series (only two years) of the data. Alternative, random-effects model specifications prove preferable as the Hausman test results for both firm types indicate. As Models (2) and (4) show, it is in the responses only from domestic firms that the curvilinear pattern is evident, which is consistent with the expectation. At the very least, this finding is reassuring in that the inverted-U pattern for the domestic firms is found even when this narrower measure of corruption (Adjusted Informal Charges) is used for a more restricted time period (2010–2011).

Table 5 Response from Domestic vs. Foreign Firms

Note: Models (1) and (3) are fixed-effects cross-sectional time-series regressions with standard errors in parenthesis, and models (2) and (4) random-effects cross-sectional time-series regressions with robust standard errors adjusted for clusters in parenthesis. * p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

CONCLUSION

There is a large literature in International Political Economy suggesting that certain governance traits such as transparency and rule of law help attract FDI. However, relatively little has been written and known about how FDI affects the host country's governance; scholars are still debating whether FDI promotes or hinders good governance. In Vietnam, both groups are right, but only partially. In this article, I have argued and demonstrated that FDI has both promoted and hindered control of corruption in Vietnam. Foreign firms tend to choose locations with good governance, which incentivizes potential host governments to make their governance better. Resources generated in FDI-led economic development also enable them to finance their efforts to improve governance. As a result, governance improves and corruption declines. With continued inflows of FDI, however, the governments in FDI-rich provinces see the resources available for improving governance increasingly strained and become less and less interested in governance reform. At the same time, a flood of FDI offers provincial leaders enormous opportunities to enrich themselves using their powers in economic management. Local leaders in FDI-rich provinces also get empowered vis-à-vis the center to such an extent that they become little constrained in pursuing narrow-minded self-interests at the expense of good governance. Widespread corruption results.

While the findings have their greatest bearing on transition economies with a single-party state such as China and other similar regimes, some generalizable lessons can be drawn. First, claims that FDI is either beneficial or harmful to host country governance as a whole are not as meaningful as they appear to be. The uneven distribution of FDI across regions within a country is, in all likelihood, inevitable; and so is the regional variation in just how FDI influences aspects of local governance. The way FDI interacts with local politics should vary from FDI-magnet provinces to catch-up provinces and to those provinces that are left out. If there is a “sweet spot,” it is most likely to be found in catch-up provinces where local leaders have tasted gains from FDI just enough to motivate them to pursue governance reform and combat corruption, but not so much as to spoil them with a continuing flood of FDI. After all, it is competition for attracting FDI that drives them to be good. The subnational politics of FDI are deserving of greater scholarly attention.

Second, FDI creates winners and losers across regions in a country and affords the winning regions a degree of autonomy from the central power (Malesky Reference Malesky2008). The change in intergovernmental relations then should have ramifications for the way the now-more autonomous regions are governed, and it should depend on the broader institutional contexts at both the national and subnational levels in which local politics is embedded. The regional autonomy afforded by FDI may create room to maneuver for local leaders, who govern in a region with a strong civic tradition, to push for better governance and greater prosperity in their own localities with disregard for or even to the detriment of the welfare of the rest of the country. Northern regions of Italy may be a case in point. Or it may reinforce the monopolistic position of local elites, who are constrained neither by local constituencies nor by the central authority, leading to a degradation of local governance and the prevalence of widespread corruption, as in the case of Vietnam's FDI-rich provinces. In the context of a transition economy, this then implies the presence of partial reform syndrome at the subnational level, in which the winners of early reform—top party leaders and government officials in those provinces that have achieved far-reaching market-oriented reforms—block further comprehensive reforms of a more political nature that would improve local-level governance but undermine their vested interests in the partially reformed, commercialized local state authority. The interesting interplay between the dynamics of state-local relations set in motion by FDI and the broader national and local institutional contexts is fertile ground for further research.