INTRODUCTION

During the Cold War, the relatively stable relationship between South Korea and Japan, which was backed by active United States military and diplomatic engagement, was a linchpin of peace and stability in Northeast Asia. Tied to the United States through bilateral military alliance pacts, the two countries not only coordinated their policies toward the communist bloc, but also served as a bulwark against the expansion of the communist Soviets and China. Since the end of the Cold War, however, the relatively stable relationship between the two nations has turned sour, giving way to the periodic eruption of confrontational interactions and even of military crises of varying degrees.

Japan's policy toward South Korea has become gradually more contentious since the mid-1990s. The dissolution of the Soviet Union, the rise of China, wayward North Korea, and the rise of defense hawks in Japan have encouraged Japan's leaders to redefine the country's national security interest in expansive terms and to gradually turn hawkish toward neighboring rivals such as China and North Korea (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2005; Christensen Reference Christensen1999; Calder Reference Calder2006). Japanese leaders, who have experienced apology fatigue, have also become increasingly confrontational toward another rival—South Korea—as conflicts of interest over key issues, such as the historical past and the Dokto/Takeshima Islands, have erupted (Berger Reference Berger2012; Arase Reference Arase2007).

South Korea's posture has not been much different. Since the country's transition to a liberal democracy in 1987, South Korean leaders have become willing to take more risk-acceptant actions toward Japan, though the behavior has not been consistent, with a cycle of more and less intensity. Korea's confrontational attitude has become more noticeable since the 1990s and 2000s, with the revelation of new historical details concerning Japan's wartime wrongdoings during its colonial domination of the Korean peninsula, which had been kept secret under previous authoritarian rulers. The level of contentiousness has displayed some variation, from simple verbal threats filled with hawkish rhetoric to material acts, such as the decision to conduct military exercises and to threaten the use of military forces (Wiegand Reference Wiegand2015; Choi Reference Choi2005; Park Reference Park2008).

There remains a question of what specifically explains South Korean leaders’ increasingly confrontational actions toward Japan. Scholars and students of Asian politics and international relations have striven to explain the causes of South Korea's confrontational Japan policies based on various theories of international relations. Capitalizing on the mutual distrust associated with disagreements about the historical past, some scholars argue that historical contention is a major cause of South Korea's contentious Japan policy (Suzuki Reference Suzuki2015; Berger Reference Berger2012; Lee Reference Lee1990). Scholars working in the tradition of realism, in contrast, argue that Korean policy toward Japan is primarily driven by a set of realpolitik factors such as the US security commitment to the two countries and the countries’ threat perception of North Korea (Sohn Reference Sohn2008; Park Reference Park2008; Cha Reference Cha2000a). The combined effect of realpolitik and ideational factors like security dilemmas, contested identities, and emotion are also considered to affect South Korea's hawkish attitude toward Japan (You and Kim Reference You and Kim2016; Yoon Reference Yoon2011; Cha Reference Cha2000b). Some argue that the tension-laden relationship between the two countries is a result of interplay between historical contentions and domestic politics drawn on populism (Rozman and Lee Reference Rozman and Lee2006; Moon and Suh Reference Moon and Suh2005). Economic distress among the Korean public has also been argued as the driving force behind Korean leaders’ confrontational actions toward Japan (Kagotani, Kimura, and Weber Reference Kagotani, Kimura and Weber2013).

Despite a number of fruitful insights offered by these studies, however, none of them has paid full attention to the domestic political causes of Korean leaders’ hawkish Japan policy. It is true that Korean leaders’ populist tendencies and their concern for economic diversion receive a good deal of attention in some studies (Rozman and Lee Reference Rozman and Lee2006; Moon and Suh Reference Moon and Suh2005; Kagotani, Kimura, and Weber Reference Kagotani, Kimura and Weber2013), but the studies are silent about what domestic political factors—aside from populism and economic turmoil—could be driving the policy. In addition, most studies have focused their attention on a single Korean leader, heavily utilizing the case study method, thereby hindering the development of a generic theory about South Korea's Japan policy.Footnote 1

Noting these weaknesses, this article develops a comprehensive theoretical framework for the explanation of the domestic political foundation of South Korean leaders’ increasingly hawkish diplomacy toward Japan. By interweaving key insights from the diversionary theory of international conflict in international politics and prospect theory in economics, we propose the “theory of prospective diversion.” Central to this theory is the idea that South Korean leaders have a strong incentive to engage in contentious diversionary diplomacy toward Japan—their perceived adversary—when they face losses in their own domestic political standings, notably a rise in their disapproval ratings and, when they fear further losses.

The article is constructed as follows: the first section presents the theory of prospective diversion and draws a hypothesis from the theory. The second section offers comprehensive statistical analyses to test the hypothesis and presents the results of the analyses, which largely confirm the hypothesis. The third section presents brief but detailed cases studies, which are supportive of the empirical findings from the statistical analyses. In the final section, the article concludes by highlighting contributions, avenues for future research, and policy implications.

ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK: PROSPECTIVE DIVERSION

A primary goal of this study is to explain the domestic political factors behind South Korean leaders’ increasingly confrontational diplomatic attitude to Japan. As discussed in the previous section, the question of exactly what domestic political factors drive Korean leaders’ contentious Japan policy remains largely unanswered. To remedy this, we develop a theory of “prospective diversion” by incorporating key insights from the “diversionary theory of international conflict” and “prospect theory,” claiming that democratic political leaders’ concern for political losses at home tends to prompt their diversionary diplomacy against a foreign adversary.

Scholars of the diversionary theory of international conflict have long claimed that political leaders, mostly democratic ones, have a tendency to initiate international conflicts, either diplomatic or military, in order to shift the nation's attention away from domestic troubles, particularly sagging public approval rate and a weak domestic economy (Foster and Palmer Reference Foster and Palmer2006; Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2005; Wang Reference Wang1996; Lian and Oneal Reference Lian and Oneal1993; Morgan and Bickers Reference Morgan and Bickers1992; Ostrom and Job Reference Ostrom and Job1986). The conflict may be any of a wide range of foreign policy activities, from war to confrontational diplomacy. In this article we focus on confrontational diplomacy, which is largely driven by the leaders’ diversionary incentive, because an overwhelming majority of diversionary conflict takes this “short of war” form. As a rare event, war is a useful diversionary tool for great powers, particularly the US, which has the capability to find international situations in which the use of force is immediately feasible (King and Zeng Reference King and Zeng2001; Meernik Reference Meernik1994). But most states and their leaders are not capable of launching costly war and, instead, they engage in confrontational diplomacy against perceived adversaries for diversionary purposes.

Our theory of prospective diversion thus focuses on political leaders’ routine use of confrontational diplomatic activities. The activities can take the form of either verbal or material threat. A prime example of a verbal threat is a “war of words.” The leaders may divert the public's domestic discontent to a foreign enemy, partly by making a speech or announcement devoid of the normal diplomatic niceties and including aggressive phrases such as “threatening at every level,” “harboring an intention to change a status quo,” and “acting like a rogue in the international society” (Li, James, and Drury Reference Li, James and Cooper Drury2009). The material threat is also a useful diversionary diplomatic tactic. Cancelling scheduled diplomatic meetings with high-ranking officials from the adversary, summoning its ambassador, putting the military on display, and conducting military drills against it are all useful ways for the leaders to distract the public's attention (Kanat Reference Kanat2014; Davies Reference Davies2011; Kurizaki Reference Kurizaki2007; Schultz Reference Schultz2001).

The question is under what circumstances diversion becomes “prospective.” We argue that diversionary tactics by political leaders can be considered prospective when they are more concerned with domestic losses than with potential gains. The existing theory of diversionary conflict pays disproportionate attention to the gains the leaders are expected to obtain by getting tough against a foreign adversary. Expecting that the conflict will give them an opportunity to garner the largest amount of public support, the theory postulates, the leaders initiate the conflict and try to boost popular support through the creation of the “rally-’round-effect” (Foster and Palmer Reference Foster and Palmer2006, 272). That is, the leaders are assumed to be primarily concerned with increasing their gain—their chances of remaining in power—by relying on diversionary tactics. But this approach tends to dismiss the possibility that the leaders’ fear of losing may carry more weight than their hope of gain or benefit, and that fear of loss may thus be an actual driver of their diversionary diplomatic activities.Footnote 2

Since the early 1970s, scholars of prospect theory have made a compelling argument that actors treat gains and losses differently: they overvalue losses relative to comparable gains. In the formulation of the theory, scholars presented experimental evidence that actors are heavily inclined to have an “asset position,” which serves as reference point, and that they tend to make a risky choice when experiencing severe loss below that point because “losses always loom larger than gains” (Kahneman and Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979; Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler1991). The major reason losses loom larger is that people tend to attach greater psychological value to their prospective losses than gains. Placing a greater value on losses in turn affects people's risk orientation, which means that people tend to be much more risk-acceptant with respect to their prospective losses (Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1992).

Applied to political leaders’ foreign policy decision making, prospect theory allows us to propose an argument that the leaders may take diversionary diplomatic actions against a foreign adversary not because of their desire for gains—restoration of their slumped approvals—but because of their concern about “prospective losses.” Specifically, the leaders are likely to be pushed into hasty and risky diversionary actions in the hope of “simply avoiding further losses.” Like a gambler on a losing streak who ups the ante in a desperate attempt to wipe out her losses, the leaders become willing to take far more risk in their handling of adversaries as the losses are expected to increase (Levy Reference Levy2003, 219).Footnote 3 This is what we mean by “prospective diversion.”

We believe this theoretical framework is well suited to explain why Korean leaders have been hostile to Japan since Korea's democratization in 1987, and why the leaders have been caught in a cycle of rising and falling levels of hostility. Since Korea introduced the liberal democratic system in 1987, Korean leaders have periodically been prompted to take a confrontational attitude to Japan. To be sure, the two former colonial rivals have faced off over a number of issues, such as Japan's attitude to its colonial wrongdoings and the contested territorial ownership claim on the Dokto/Takeshima islands. This creates a broad context in which it is possible for Korea to perceive Japan as an adversary rather than a friend (You and Kim Reference You and Kim2016; Park Reference Park2008; Sohn Reference Sohn2008; Rozman and Lee Reference Rozman and Lee2006).

Given this context, Korean leaders have made constant attempts to avoid loss of public support, most of which are the result of legitimacy crises derived from scandal, corruption, and economic downturn, by taking a tough diplomatic stance on Japan. While most Korean presidents begin their tenure with hints of future cooperative relations with Japan, a majority have adroitly played the Japan card whenever they were faced with a domestic loss such as a spike in public disapproval rating, and they have created a diplomatic crisis with Japan as a means of warding off the prospective loss. President Young-Sam Kim, for instance, did not hesitate to launch a war of words against Japan when the Korean public's disapproval of his wayward reform plans was high, while his successors Muhyun Roh and Myungbak Lee readily issued material threats over the Dokto/Takeshima islands as the level of public discontent skyrocketed as a result of their key officials’ involvement in bribe scandals (Sohn Reference Sohn2008; Moon and Suh Reference Moon and Suh2005; Choi Reference Choi2005; Rozman and Lee Reference Rozman and Lee2006; Drifte Reference Drifte1996).

Grounded in the theory of prospective diversion, therefore, we postulate that Korean political leaders’ concern about losses in their domestic political standing is a major driver of their contentious diversionary diplomacy toward Japan. Two simple time-series plots, presented in Figure 1, roughly illustrate the relationship between the leaders’ losses, as measured by an increase in disapproval ratings, and their contentious diplomatic actions toward Japan.Footnote 4

Figure 1 Time-Series Plots of Korean Presidents’ Disapproval Ratings and Number of Contentious Actions Toward Japan

As shown in Figure 1, contentious diplomatic actions toward Japan by ROK leaders rise and fall significantly in cycles. Especially intriguing, however, is that these cycles appear to be positively associated with the changes in the Korean presidents’ approval ratings. During the period of 1988–91, for example, Korean leaders appear to have taken a greater number of contentious actions against Japan, and these coincided with an increase in public disapproval ratings. Such actions returned around 1993 and continued through the end of 1997. In this period, Korean leaders continued to turn hawkish toward Japan after experiencing an increase in their disapproval ratings.

While the relationship during the period of 1998–2002 is not well observed, to contentious actions appear to persist from 2003 onwards. From 2004 to 2012, in particular, the positive relationship between an increase in disapproval ratings and the number of contentious actions is both quite noticeable and frequent. Based on the prospect theory of contentious diplomacy and a review of the time-series plots between the variables the theory identifies, we generate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis: Korean leaders are likely to take a greater number of confrontational actions toward Japan if they experience an increase in their disapproval ratings (a decrease in their approval ratings).

RESEARCH DESIGN

POPULATION AND DEPENDENT VARIABLE

The study's dependent variable is the count of South Korean leaders’ confrontational actions (either verbal or material), toward Japan during the period of 1988–2012. The article gives its primary attention to South Korea's Japan policy since it transitioned to democracy in 1987. Only after transitioning to democracy did South Korea introduce a system of competitive and regularly held democratic elections, and, as a result, political leaders have begun to pay attention to presidential approval ratings on a regular basis (Im Reference Im2004).

The count is derived from the Global Database for Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT).Footnote 5 The GDELT collects approximately 250 million events from major media outlets in over 100 languages and provides the most comprehensive dyadic data for interstate conflict and cooperation during the period of 1979–2012 (Leetaru and Schrodt Reference Leetaru and Schrodt2013). Some scholars have already utilized the GDELT for their studies of foreign interactions between states. Using the GDELT-generated event data, for instance, Kagotani, Kimura, and Weber (Reference Kagotani, Kimura and Weber2013) demonstrated that South Korea's belligerent Japan policies have been affected by Korean leaders’ motivation of economic diversion. Morgan and Reiter's (Reference Morgan and Reiter2013) study of the effect of insurgency and external threat on India's state-making is another example in which the GDELT has been used. Grounded in the GDELT count of street protests, Acemoglu, Hassan, and Tahoun (Reference Acemoglu, Hassan and Tahoun2016) found that the stock market valuations of firms associated with major protest groups in Egypt during the Arab Spring were affected by the number of demonstrations that the groups organized.

Since the GDELT incorporates the weighted Goldstein's Conflict and Cooperation Scale using the TABARI software, the number of all foreign event counts it covers is organized into two categories—verbal and material conflict—according to two types of actors—the president and his or her elites. Both the verbally and materially confrontational actions taken by Korean presidents and elites toward Japan during the period of 1988–2012 are summed and averaged on a quarterly basis to generate a dependent variable denoted ROK–JAPAN CONFRONT.

INDEPENDENT VARIABLES

To measure the levels of Korean leaders’ loss in their domestic political standing, we create two variables called DISAPPROVALt-1 and APPROVALt-1. The variables are quarterly measures of the Korean public's disapproval (approval) of Korean presidents for the period of 1988–2012. Data on the public's disapproval (approval) ratings are derived from Gallup's quarterly measures of presidential disapproval or negative approval ratings.Footnote 6 All data are lagged one quarter to reflect the fact that there is a time interval between recent indication of the ratings and leaders’ response to the indication by adopting confrontational diplomatic actions (Foster and Palmer Reference Foster and Palmer2006, 278). We expect a positive (negative) effect on the DISAPPROVALt-1 (APPROVALt-1) variable.

CONTROL VARIABLES

The study includes a set of control variables that may affect political leaders’ proclivity to engage in confrontational foreign policy for domestic purposes. Scholars of diversionary international conflict contend that domestic political factors such as partisan difference, congressional support, and upcoming presidential elections tend to increase the probability of leaders engaging in the policy. The partisan difference matters because the hawks (or the right) are inclined to rely on military force, while the doves (the left) are likely to opt for diplomatic solutions (Foster and Palmer Reference Foster and Palmer2006). The levels of congressional support affect presidents’ diversionary use of force because presidents are more likely to conduct diversionary military campaigns as their party's share of the Congress increases (Howell and Pevehouse Reference Howell and Pevehouse2005). Presidents also are more likely to engage in the campaigns when presidential elections draw near because they want to be reelected (Gaubatz Reference Gaubatz1991; Wang Reference Wang1996; Ostrom and Job Reference Ostrom and Job1986).

Following this line of argument, the article creates the PARTISAN, SEATS, and ELECTION variables in the South Korean context. The PARTISAN variable identifies whether Korean presidents and their ruling parties are more hawkish or dovish in their foreign policy. So-called conservative leaders like Presidents Roh Tae-Woo, Kim Young-Sam, and Lee Myung-Bak, and their ruling parties, the Minjeong Party (Party of Democratic Justice), Minja Party (Party of Democratic Freedom), Sinhankook Party (Party of New Korea), and Hannarah Party (Party of One Nation), are considered hawks in Korean politics because of their proclivity to take confrontational stances toward foreign rivals. Progressive leaders like Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-Hyun and their ruling parties, the Saechunnyun Minju Party (New Millennium Democratic Party) and Yeolin Uri Party (Our Open Party), are identified as doves, preferring compromise to confrontation (Park Reference Park2008; Sohn Reference Sohn2008; Rozman and Lee Reference Rozman and Lee2006; Moon and Suh Reference Moon and Suh2005). Therefore, the PARTISAN variable is a binary one in which the era of conservative presidents and of their ruling parties is coded 1 and others are coded 0. The SEAT variable is measured by calculating the average percentage of seats held by the presidents’ parties in the National Assembly. Data on the seats are derived from the Proportional Democracy Forum.Footnote 7 The ELECTION variable is coded 1 during third quarters before a presidential election year and 0 otherwise. We expect positive effects on the variables.

Regarding external variables, we develop aggregate (models 1 and 2) and disaggregate models (models 3 and 4) for taking both regional and bilateral security situations seriously. We use the ALL CONFRONT variable, which is an aggregate measure of contentious actions toward South Korea by the US and North Korea, to control for the influence of the regional security environment on Korean leaders’ proclivity to engage in confrontational Japan policy. Since the higher level of external threats at the regional context do not allow South Korean leaders to exclusively focus on South Korea–Japan disputes, we expect a negative effect on the variable.Footnote 8

To capture the effect of the bilateral security environment on Korean leaders’ contentious actions toward Japan, we create a set of bilateral-hostility variables. First, we control for the effect of Japan's hawkish stance on South Korea by creating the JAPAN–ROK CONFRONT variable because Korea's hostile Japan policy is more likely if Japan engages in a greater number of hostile actions toward Korea (Yoon Reference Yoon2011; Park Reference Park2008; Sohn Reference Sohn2008; Rozman and Lee Reference Rozman and Lee2006). The variable is measured by the total count of contentious actions from Japan to the ROK, relying on the GDELT. We expect a positive effect on the variable.

The DPRK–ROK CONFRONT and DPRK–JAPAN CONFRONT variables control for the North Korean factor in Korea–Japan relations. Some point out that if the DPRK takes more hostile actions toward the ROK and Japan, the leaders of the two countries are likely to direct their attention to their immediate enemy—the DPRK—and to become less hostile toward each other (Park Reference Park2008; Sohn Reference Sohn2008). The variables are measured by the total count of hostile actions by North Korea toward both South Korea and Japan using the GDELT. We expect a negative effect on the variables. In a related vein, both the US–ROK CONFRONT and US–JAPAN CONFRONT variables take the US factor into consideration. It has been argued that facing hawkish response from the US, both Korea and Japan will suffer from a fear of being abandoned and, consequently, are likely to become less confrontational toward each other (Cha Reference Cha2000a, 17; Sohn Reference Sohn2008). The variables are measured by the total count of US contentious actions toward South Korea and Japan. All data are derived from the GDELT. We expect a negative effect on the variables.

Finally, we control for an economic variable—economic misery. The scholars of economic diversion claim that economic stresses such as rising inflation and high unemployment may prompt political leaders’ confrontational foreign policy in an attempt to divert the public's attention from their economic distress to foreign events (Kagotani, Kimura, and Weber Reference Kagotani, Kimura and Weber2013; Fordham Reference Fordham1998; Ostrom and Job Reference Ostrom and Job1986). To control for the effect of such poor economic conditions, we introduce the MISERYt-1 variable, which is a sum of inflation and unemployment rates. All data on the variable is derived from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) database on South Korea's economic performance.Footnote 9 The variable is lagged one quarter to reflect the fact that it will take some time for Korean leaders to engage in contentious diplomacy after experiencing an economic distress. We expect a positive effect on the MISERYt-1 variable. A summary of the statistics related to the dependent, independent, and control variables is presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics

Note: All data are created on a quarterly basis.

STATISTICAL MODEL

The most common statistical technique in testing a model in which a dependent variable is a positive count of events is the Poisson Regression Model. However, it is important to note that the model operates under the highly restrictive assumption that the variance of the dependent variable equals its mean. When the assumption is violated, there is an “over-dispersion” problem. The consequence of over-dispersion is potentially so severe that the model would generate highly inefficient estimates as well as standard errors biased downward, resulting in spuriously large z-values (Greene Reference Greene2003, 744). In our data, the over-dispersion problem is also present. The variance of the count of confrontational actions South Korean leaders take toward Japan is quite a bit larger than the mean of the count.

The most efficient way to handle the over-dispersion problem in count data is to use the Negative Binomial Regression Model (NBRM). The NBRM regression is specifically designed to handle the over-dispersion problem in count data by simply adding a parameter that allows the conditional variance of dependent variable or “y” to exceed the conditional mean (Lawless Reference Lawless1987). We use the NBRM model to test our hypotheses using the variables delineated above.

Before fitting our data to negative binomial distribution, however, it is necessary to check whether a dependent variable, that is, the count of Korea's contentious actions toward Japan, may display autocorrelation (Kagotani, Kimura, and Weber Reference Kagotani, Kimura and Weber2013). The presence of autocorrelation in the variable means that error terms from adjacent to current time periods could be correlated. In this circumstance, the efficiency of estimators tends to be decreasing, and the estimates of the standard errors are smaller than the true standard errors. So, we conduct a set of diagnostic tests—the Correlograms test and augmented Dickey-Fuller test—and find that there is autocorrelation in the variable. To handle this problem, we fit our data to Generalized Linear Models (GLM), in which a negative binomial distribution is embedded as a family function, which is denoted NB GLM, and the Newey–West standard errors are used.

The NB GLM is a flexible generalization of ordinary linear regression that allows for response variables that have error distribution models other than a normal distribution (Hardin and Hilbe Reference Hardin and Hilbe2012). It is usually made up of two functions, a link and a variance function. A link function—that is, the log—provides the relationship between the linear predictor and the mean of the distribution function in the NB GLM (Shedden Reference Shedden2010). For the variance function, we use the Newey–West standard error. The Newey–West standard errors developed by Whitney K. Newey and Kenneth D. West are often used to correct time series dependence in nearly any non-linear model (Newey and West Reference Newey and West1987, 703). We believe that the NB GLM with Newey–West standard errors is the most efficient model to fit the event count data, which suffer from both over-dispersion and autocorrelation.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

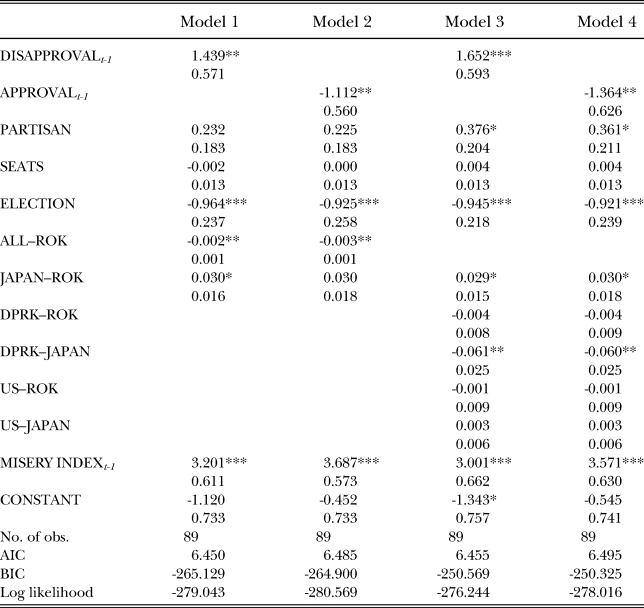

To test the hypothesis derived from our theory of prospective diversion, the article estimates the effect of the Korean public's disapproval of its leadership on the count of confrontational actions that Korean presidents and their governmental officials take toward Japan, relying on the NB GLM after controlling for a series of political and economic variables. All results are reported in Table 2, and model-related statistics are given at the bottom of the Table.

Table 2 NB GLM Analyses of the Determinants of Korea's Japan Hostility, 1988–2012

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Note: Cell entries are coefficient estimates, and Newey–West standard errors are in parentheses. Two-tailed significance levels of 0.10 or less are reported.

The first column of Table 2 (Model 1) provides the results from our baseline or aggregate model in which the Korean public's disapproval rating of its presidents and the count of confrontational actions between the ROK and all relevant states—in this case the US and North Korea—are considered together after controlling for other variables. Several points are immediately apparent. First, the DISAPPROVALt-1 variable has a statistically significant and positive impact on the count of South Korea's contentious actions toward Japan, indicating that Korean leaders’ political loss expressed in terms of an increase in the disapproval rating makes them more hawkish toward Japan.Footnote 10 The ELECTION variable also has a statistically significant and negative effect on the count of the actions. The result is somewhat different from what the scholars of diversionary international conflict predict but quite understandable if one pays a good deal of attention to Korean politics. Korean presidents have a five-year and one-term presidential tenure limit (Im Reference Im2004). Given this, they have little incentive to turn hawkish to Japan to win reelection. Moreover, an election may encourage the presidents to draw considerable attention to domestic affairs (Gaubatz Reference Gaubatz1991).

It is also important to note that the JAPAN–ROK variable has a statistically significant and positive effect, indicating that an increase in Japanese leaders’ contentious actions toward the ROK makes Korean leaders turn more hawkish toward Japan. Yet, the ALL–ROK variable, which is the sum of US and North Korea's confrontational actions toward Korea, has a statistically significant and negative effect on the count of ROK leaders’ antagonistic actions toward Japan, suggesting that an increase of contentious action from US and North Korea make the leaders less hawkish to Japan. The MISERYt-1 variable has a statistically significant and positive effect on the count of the actions, suggesting that the Korean public's worsened (improved) economic condition makes its leaders more (less) hawkish to Japan. The result confirms that there is a strong tendency of economic diversion among Korean political leaders regarding their Japan policy (Kagotani, Kimura, and Weber Reference Kagotani, Kimura and Weber2013).

The second column of Table 2 (Model 2) provides the results of a robustness check on the results of Model 1 by replacing the DISAPPROVALt-1 variable with the APPROVALt-1 variable after controlling for the same set of control variables. The APPROVALt-1 variable has a statistically significant and negative impact on the count of South Korea's contentious actions toward Japan, re-confirming that an increase in the Korean public's domestic loss makes Korean leaders more hawkish toward Japan. The effect of all other variables remains the same with that of model 1. Both the ELECTION and the ALL-ROK variables make Korean leaders less hawkish to Japan while the MISERYt-1 variable makes them more hawkish.

The third column of Table 2 (Model 3) presents a disaggregate model in which the count of contentious actions between the ROK and all relevant states, including Japan, are considered “separately.” First, the DISAPPROVALt-1 variable still has a statistically significant and positive impact on the count of Korean leaders’ hostile actions toward Japan, indicating that Korean leaders’ loss—that is, an increase in the public's disapproval rating—makes them take more contentious actions toward Japan. In addition, the PARTISAN variable has a statistically significant and positive effect on the count of Korean leaders’ hostile actions toward Japan, while the ELECTION variable has a statistically significant and negative effect on the count. The results indicate that hawkish leaders from hawkish ruling parties in Korea are likely to take more confrontational actions toward Japan, while upcoming presidential elections make Korean leaders take fewer contentious actions.

Concerning a set of bilateral hostility variables, both the JAPAN–ROK and DPRK–JAPAN variables have a statistically significant and positive effect, indicating that an increase in Japanese leaders’ contentious actions toward the ROK makes Korean leaders turn more hawkish toward Japan, while an increase in DPRK leaders’ confrontational actions makes Korean leaders less contentious toward Japan. The MISERYt-1 variable has a statistically significant and positive effect on the count of Korean leaders’ hostile actions, indicating that the leaders are likely to take more contentious actions toward Japan when the Korean public suffers from an economic distress.

The fourth column of Table 2 (Model 4) includes APPROVALt-1 with the same set of control variables used in Model 3. The result is interesting. First, the APPROVALt-1 has a statistically significant and negative impact on the count of South Korea's hostile actions toward Japan, indicating that a decrease in the Korean public's approval makes Korean leaders more hawkish to Japan. The result implies that the effect of the DISAPPROVALt-1 is robust to running it on the APPROVALt-1 variable.

The PARTISAN variable has a statistically significant and positive impact on the count of Korean leaders’ hostile actions toward Japan, while the ELECTION variable has a significant and negative effect on the count. The results imply that hawkish Korean leaders from hawkish ruling parties are likely to take more confrontational actions toward Japan, while Korean leaders are likely to take fewer contentious actions when a presidential election draws nearer. The MISERYt-1 variable has a statistically significant and positive effect on the count of the leaders’ contentious actions, indicating that the leaders are likely to take more hawkish actions toward Japan when the Korean public suffers from economic distress.

Taken together, our statistical analyses find Korean presidents’ concern for political loss in their domestic standings is behind their increasingly confrontational diplomacy toward Japan. The loss, as measured by an increase in the Korean public's disapproval, makes its presidents take a more aggressive posture. The analyses also re-confirm that there is a strong tendency for Korean leaders to engage in economic diversion toward Japan.

CASE EVIDENCE

To support the empirical results from the statistical analyses presented above, we conducted two case studies, examining Presidents Roh Moo-Hyun and Lee Myung-Bak's risk-seeking diplomacy toward Japan during the periods of 2003–07 and 2008–12, respectively. In these two examples, Roh and Lee started their terms with a quite dovish Japan policy, promising future-oriented relationships with it. After experiencing a series of legitimacy crises and a subsequent restoration of popular support during their tenures, however, the two Korean presidents began to view increases in popular discontent as serious political losses and were prompted to take increasingly contentious actions toward Japan to prevent further losses.

President Roh Moo-Hyun was a well-known dove in Korea's political spectrum and a staunch champion of compromise and cooperation in foreign policy. Immediately after coming to office, Roh held a summit with Japan's prime minister, Zunichiro Koizumi, in Jeju, Korea, in July 2004. In the press conference after the summit, Roh clearly said that “the relations between South Korea and Japan should be forward-looking and that his government would restrain from raising unnecessary historical and territorial provocations toward Japan” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2004).

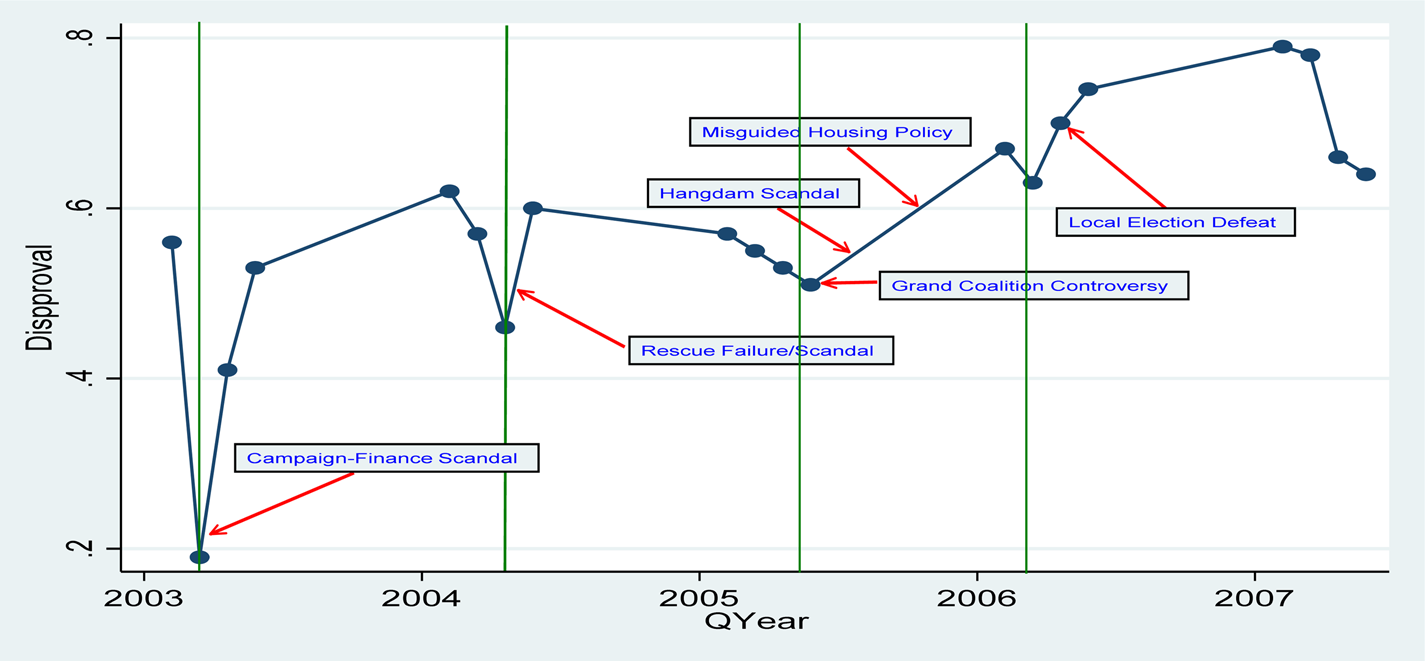

However, Roh's conciliatory attitude toward Japan gradually transitioned to a less friendly and even confrontational one beginning in late 2004. To be clear, Japan's periodic provocations concerning the historical tension between the two nations and over the ownership of the Dokto/Takeshima islands created an environment in which Roh's officials might have been expected to adopt an increasingly hawkish response to Japan. But it is also important to note that South Korea's domestic political dynamics, particularly the rise of presidential disapproval ratings that stemmed mainly from a corruption scandal and policy failures, prompted Roh and his officials into the adoption of confrontational policies toward Japan. Figure 2 lists some of the important events that were closely associated with the increase in Roh's disapproval ratings during his tenure.

Figure 2 Domestic Political Events and Changes in President Roh's Disapproval Ratings

One of the most serious political crises during Roh's tenure—an impeachment by the National Assembly—took place early in his tenure, indeed soon after his arrival at the Blue House. A minor election law violation on his part was heavily exploited by conservative opposition parties, with the result that Roh was impeached in a 193–2 vote by the Korea National Assembly, resulting in the suspension of his presidential power as head of state and chief executive. Two months later, the Constitutional Court overturned his impeachment, ending the crisis. In the April 2004 general election, Korean voters punished the parties and tripled the seats of the Uri Party, a new liberal coalition that backed President Roh (Brook Reference Brooke2004). Accordingly, Roh enjoyed a substantial decrease in the public's disapproval ratings from 60 percent to 51 percent. After making such a quick gain, Roh started to regard any subsequent increase in his disapproval ratings as a serious political loss.

Within six months of his survival of the impeachment allegation, however, Roh witnessed a systemic increase in the public's disapproval ratings. In mid-2004, a Korean missionary was kidnapped and executed by an extreme Islamist terrorist group. Despite his determined effort to save the missionary, Roh had to admit that his rescue plan failed completely (Hong and Demick Reference Hong and Demick2004). The failure led to the defection of President Roh's loyal supporters, who were adamantly against Korea's deployment of ROK troops into Iraq, which the US had invaded in 2003. Roh's fear of losing further support prompted his risk-acceptant Japan policy.

One of Roh's riskiest decisions was to make the secret documents related to the 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea available to the public, on January 17, 2005. While experiencing strong pushback from multiple sources in Japan, including Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Roh's officials moved the decision forward, believing that the revelation of the documents might help Roh stop a further increase in the public's dissatisfaction with him. In the 2005 annual remembrance of the March 1st movement against imperial Japan, Roh turned more hawkish by issuing a strong anti-Japanese statement. He not only lambasted Japan over a wide range of historical issues but also asked Japan to follow the path set by Germany at the end of World War II. Specifically, he strongly urged Japan to make a moral decision to admit its wartime wrongdoings and offer proper compensation (Blue House Reference House2005).

In March 2005, President Roh went a step further. Japan's provocation on the Dokto/Takeshima islands had already created the negative conditions under which Roh's government adopted a much more hawkish stance toward Japan. On March 16, 2005, the assembly of Japan's Shimane Prefecture voted to declare an annual “Takeshima day” (Onishi Reference Onishi2005). Japan continued to provoke Korea over the islands by asserting its ownership of the islands in a 2005 white paper. Against the backdrop of this bold provocation, Roh went to the extreme of declaring a “virtual diplomatic war,” stating, “Now, South Korean government has no choice but to sternly deal with Japan's attempt to justify its history of aggression and colonialism and revive regional hegemony” (Min Reference Min2005).

President Roh experienced another spike in his disapproval ratings, from 55 percent to 67 percent, at the end of 2005. Above all, his agenda of forming a “grand political coalition” with opposition parties, which was designed to avoid a further deterioration of his political standing, in fact accelerated the exodus of loyal supporters, which became a huge blow to Roh's legitimacy (Kim Reference Kim2016). A political event known as the “Hangdam Islands Scandal” also occurred in late 2005 and brought the Roh government to yet another legitimacy crisis (Kim Reference Kim2005). The local election defeat of June 2006 was a vivid example of how unpopular Roh was on the domestic front at the end of his tenure.

From late 2005 onwards, therefore, Roh was desperate to counter the losses by taking highly contentious actions toward Japan. In April 2006, the Roh government abruptly declared that the titles of geographical features under the East Sea (or Sea of Japan), which belongs to Korea's Exclusive Economic Zone, would be interpreted in Korean and sent to the International Hydrographic Organization (Koo Reference Koo2010). Provoked by the declaration, Japan decided to dispatch its survey ships into the sea around the Dokto/Takeshima islands. Responding to the decision, Roh took the most hardline approach to Japan by ordering the Korean coast guard to destroy Japanese ships if they entered the sea around the islands (Park Reference Park2010). A series of such events resulted in the most strained period of relations between Korea and Japan under Roh's presidency.

Another piece of evidence showing that Korean leaders’ concern for their domestic political loss might drive their confrontational diplomacy toward Japan is President Lee Myung-Bak's hawkish engagement of Japan during the period of 2010–12. Lee, widely known as a pro-Japanese leader in Korean politics, began his tenure by stressing that the relationships between Korea and Japan should be a future-oriented partnership and suggesting a restoration of bilateral shuttle diplomacy. At his summit with Japanese Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo, therefore, Lee's attention was fixed on ways to improve economic cooperation with Japan, and historical issues were intentionally put aside (Snyder Reference Snyder2008).

In mid-2008, however, Lee experienced an unexpected legitimacy crisis. His decision to open the Korean market to US-produced meat, which was believed to have been exposed to mad cow disease, resulted in nationwide protests that called for his immediate resignation from office (Choe Reference Choe2008). Alarmed by a spike in the Korean public's discontent, Lee not only cracked down on the protests, but also made systemic efforts to decrease his disapproval by reviving the economy through active cooperation with opposition parties. From mid-2009 on, Lee treated his disapproval rating as the new status quo, believing that any further increase in the disapproval would be a grave loss. The restored popularity laid a strong domestic political foundation in which Lee's government was able to pursue a series of policies such as green growth, developing a business-friendly economy, and G-20 diplomacy.

However, around mid-2010 Lee's posture on Japan drastically changed from continued bilateral cooperation to open confrontation. At the center of the change was his growing concern for political loss on the domestic front instigated by a series of political scandals and controversial policies. Figure 3 presents a summary of how President Lee's political loss—a gradual increase in disapproval ratings—was associated with the scandals and policies from the middle of 2010.

Figure 3 Domestic Political Events and Changes in President Lee's Disapproval Ratings

President Lee's legitimacy thus started to collapse in mid-2010; his domestic political foundation was most significantly eroded by a surveillance scandal. In July 2010 the Korean Broadcasting System, Korea's major news station, revealed that the Ethics Division of Korea's Prime Minister's Office, which was tightly controlled by President Lee, had secretly investigated a South Korean civilian named Kim Jong-ik, a bank employee who posted in his blog a video clip that severely ridiculed Lee (Glionna and Park Reference Glionna and Park2010). The scandal fueled opposition parties’ and liberal societal actors’ furor, leading to their intense resistance to the legitimacy of Lee's government and resulting in a stunning rise in his disapproval rating.

Encountering the rise in disapproval, Lee's officials adroitly played the anti-Japan card against the backdrop of two incendiary acts by Japan. In July 2011 the Japanese government made a decision to forbid its foreign ministry staff from using Korean Airlines for a month, when the airline conducted the inaugural flight of its A380 passenger jet above the Dokto/Takeshima islands. In addition, three Liberal Democratic Party Japanese Congressmen announced that they would make an attempt to land on Uleung Island, which is located at the gateway of the Dokto/Takeshima islands (Oliver and Nakamoto Reference Oliver and Nakamoto2011).

Tapping into mounting anti-Japanese sentiment on the domestic front, Lee made quick anti-Japanese moves to avert further losses associated with the surveillance scandal. In response to the Japanese ban on flying with Korean air, the Korean government asserted that it was taking the matter very seriously, as the ban had the effect of placing sanctions on a Korean private company (Lee Reference Lee2011a). Regarding the politicians’ attempt to visit the islands, Lee Jae Oh, president Lee's right-hand man, said “I will stay there until the Japanese lawmakers leave” and asserted: “the descendants of war criminals are daring to test the Republic of Korea. I will show them clearly that there is no land here for them to set foot.” (Lee Reference Lee2011b).

Lee's political loss continued to grow from mid-2011. A bank-loan scandal in which President Lee's key men and relatives were believed to have been involved in both a direct and indirect manner came before the public eye. Lee's effort to privatize Korean Train eXpress (KTX) by 2012 invited mounting criticism from left-wing opposition parties and societal groups, who believed KTX should be considered one of the major public goods (Kim Reference Kim2012). Another scandal, in which some of Lee's key officials were involved in a deal to buy a plot of land in Naegok-dong for a retirement home for President Lee, also loomed over him, prompting the major opposition Democratic Party, in June 2012, to accuse them of peddling their influence. Even worse, Lee had to deliver a strongly worded apology to the public after Lee Sang-deuk, his 76-year-old elder brother and close political ally, was arrested in connection with allegations that he had accepted $500,000 from two bank chairmen seeking political influence (Mundi Reference Mundi2012). Lee's disapproval rating hit an all-time high.

Thus, President Lee's unexpected visit to the Dokto/Takeshima islands on August 10, 2012 should be understood as his desperate attempt to avoid the blow of a rise in his disapproval rating as his tenure drew to a close. While visiting the islands and stepping up the security force in the region, he made it quite clear to the Korean media that he had become the first president to visit the islands in Korea's modern history. It is now well known that most interpreters of Korean politics during the visit maintained that the president's unexpected visit to the islands was one of his attempts to overcome the many corruption scandals he faced at home (Choe Reference Choe2012).

The confrontational posture of President Lee toward Japan reached a peak when he touched on Japan's most sensitive issue: its emperor. While discussing the emperor's visit to South Korea, he bluntly requested that the emperor make an apology about Japan's wartime wrongdoings, particularly the killing of Korea's independence fighters (Ahn Reference Ahn2012). Since Korea's transition to democracy in 1987, no single Korean president had made such a bold request of the emperor. The request led to sharp criticism both in Korea and Japan that he was playing the Japan card in the most hawkish manner simply to avoid his further loss in political standing (Park Reference Park2012; Yokota Reference Yokota2012). Relations between Korea and Japan hit rock bottom.

Taken together, our case studies of the contentious Japan policies of Korean Presidents Roh Moo-Hyun and Lee Myung-Bak lend strong support to the hypothesis that Korean presidents are more likely to take hawkish actions toward Japan when they suffer losses in domestic political standings. Both Roh and Lee began their tenure by promising a future-oriented relationship with Japan, free from chronic disputes over their negative historical relations and ownership of the Dokto/Takeshima islands. Yet faced with significant loss in their domestic political standings—a rise in the Korean public's disapproval, which was mostly associated with scandals and policy failures—the two presidents turned quite antagonistic toward Japan in a desperate attempt to eliminate the losses by shifting the public's attention away from themselves. The presidents not only responded to Japan's routinized provocations in a disproportionate way, they intentionally created unnecessary diplomatic crises against Japan.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The article began with the simple question of what domestic political factors drive South Korean leaders’ contentious diplomacy toward Japan. To answer the question, we developed a theoretical framework called the “prospective diversion” by interweaving the key insights from the diversionary theory of international conflict and prospect theory. Central to the theory is that political leaders in democratic polity are likely to engage in confrontational diplomacy toward their enemies when they experience a loss in domestic political standing, specifically an increase in the public's disapproval ratings. Both statistical analyses and case studies of South Korean leaders’ confrontational Japan policy provide strong empirical evidence that is largely commensurate with the theory.

This article's major contribution to scholarship on South Korea's policy toward Japan is twofold. First, we examine a domestic political foundation of South Korea's contentious diplomacy toward Japan through the creation of theory of “prospective diversion.” An overwhelming majority of studies on Korea's Japan policy still treat the two countries as unitary actors and investigate the effect of real-politik and ideational factors, which have been argued to drive Korean officials’ non-cooperative attitude to Japan. By developing domestic-centered theory and applying it to South Korean leadership, however, we present a novel argument that Korean leaders’ fear of a loss in their political standing can be a major driver of their confrontational Japan policy. Second, we test our argument in an innovative way. Our statistical model—a “Negative Binomial GLM”—is the most efficient statistical model to fit the event count data, which suffer from both over-dispersion and autocorrelation. Our case studies, which examine the process leading to Korean leaders’ contentious Japan policy, rely on vertical timelines and are corroborative as well as illustrative.

We believe, however, that our study is only an initial step toward a complete understanding of domestic political causes of Korea's contentious diplomacy toward Japan. Since our attention is focused on Korean leaders’ Japan policy since the 1987 democratization, future research must pay an equal amount of attention to the causes under military leaders during the period 1961–86. There is some evidence that even under military leaders, Korea's Japan policy was heavily swayed according to the change in the Korean public's threat perception of Japan (Cha Reference Cha2000a; Park Reference Park2008). Second, our research is based upon a relatively simple assumption about Japan—Japan is provocative. However, it is important to note that Japan's foreign policy toward Korea also may be affected by a wide range of domestic political factors, most notably the fortune of Japanese political leaders. Future research should examine how such factors might have driven Japan's confrontational diplomacy toward Korea.

The article does reveal an important policy implication for South Korean leaders. The empirical evidence presented above shows that South Korean leaders are quite risk-seeking toward Japan when they experience domestic political losses. Specifically, it demonstrates that a surge in their disapproval ratings tends to heighten the leaders’ perception of the loss and make them quite confrontational to Japan, which is considered a long-standing adversary of Korea. To construct a more predictable and stable relationship with Japan, therefore, Korean leaders need not only to restrain themselves from engaging in overly contentious policy, but also to develop a diplomatic manual in which a step-by-step guide commensurate with Japan's provocation of varying degrees is highlighted. International goals should not be sacrificed for immediate domestic needs.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Chaekwang You and Wonjae Kim declare none