1 INTRODUCTION

Governments of every stripe take a public stand against political corruption. In addition to diverting scarce resources, impeding economic development, and crippling the provision of basic public goods, corruption also erodes the legitimacy of the political system (Seligson Reference Seligson2002). The sinister nature of corruption is amplified in non-democratic countries, where corruption can become a rallying point for the public to protest against the regime and demand political reform. It is therefore common for authoritarian rulers to portray themselves as enemies of corrupt officials. After taking power through military coups, for example, militaries frequently cite corruption as a justification and conduct “house cleaning” exercises. Even Suharto, whose 31-year reign in Indonesia was considered highly corrupt, enacted cosmetic reforms to tackle corruption and require civil servants to return personal assets annually (Quah Reference Quah1999, 486).

Corruption control is, at its core, a search for answers to collective action and principal–agent problems. Autocrats can tolerate a certain degree of corruption as a way to reward loyal agents, but they will be keen to prevent it from reaching a proportion that ignites social unrest. Punitive measures against graft and embezzlement play a role in keeping corruption within tolerable boundaries; importantly, they also provide a legitimate channel to remove agents who are building power bases to challenge the autocrats. The imperative to monitor and control state agents holds the key to understanding anticorruption efforts in authoritarian regimes.

In democratic societies, institutions that impose legal constraint on political power and promote government accountability are essential for monitoring state agents and building clean government (Rose-Ackerman Reference Rose-Ackerman1999; Yusuf Reference Yusuf2011; Ackerman Reference Ackerman2013). For authoritarian rulers bent on maintaining absolute power, however, establishing checks and balances will be a hard pill to swallow, as will be the attempt to foster a vibrant civil society. In contrast to external supervision, autocrats are more receptive to measures that enhance top-down oversight and control within the government apparatus.

Internal government control can take one of two forms. First, authoritarian rulers can design rational bureaucratic structure and binding rules to minimize corruption and clientelism. Contract design and selection mechanisms can shape the incentive structure of state agents (Kiewiet and McCubbins Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991), restraining them from engaging in rampant corruption that threatens the long-term survival of the regime. This mode of corruption control mainly relies on routine bureaucratic procedures and monitoring. By contrast, regimes can also employ ad hoc, campaign-style enforcement (Wedeman Reference Wedeman2005) that periodically mobilizes resources to detect and penalize corrupt officials. These mobilizations are initiated unpredictably, usher in a period of rapid action and harsh punishment, and gradually fizzle out.

Given that authoritarian regimes adopt both modes of top-down control to contain corruption, which approach will prove more effective in curbing rent-seeking behavior by state agents? Or do they work in tandem to reinforce the monitoring of lower-level officials? This article addresses these questions in the context of China's prolonged fight against corruption. Since China embarked on market reform in the late 1970s, the problem of corruption has escalated notably and become increasingly salient in the country's political discourse (Gong Reference Gong1997; He Reference He2000; Wedeman Reference Wedeman2004). The conceptual distinction between routine bureaucratic management and ad hoc mobilization is useful for understanding the various anticorruption strategies pursued by the ruling Communist Party in China (CCP). On the one hand, bureaucratic procedures in the form of appointment, reporting, and auditing are performed to overcome information asymmetry and monitor lower-level cadres (Huang Reference Huang1995, Reference Huang2002). On the other hand, the central Party leaders make speeches and issue directives to dictate the pace of national anticorruption activities, often oscillating between hyper enforcement and relative calm (Manion Reference Manion2004; Wedeman Reference Wedeman2005).

The CCP employs a wide range of bureaucratic procedures to manage its large cadre corps. Among them, the cadre rotation system stands out as a widely used approach to monitor and control bureaucrats. Under this system, provincial officials in China are frequently reshuffled to serve in new jurisdictions. One of the professed benefits of rotation is to separate the officials from established network of local elites, giving them fewer rent-seeking opportunities and a freer hand to combat corruption. However, using different measures of anticorruption enforcement, our empirical analysis reveals little evidence that cadre rotation plays any part in strengthening anticorruption efforts. Rather, we find that the intensity of enforcement at the provincial level respond strongly to varying central emphasis on anticorruption, suggesting a centralized disciplinary system. The empirical results imply that the periodic campaign approach plays a critical role in China's law enforcement patterns, while the regime's routine monitoring devices are largely ineffectual.

Evaluating the effectiveness of different approaches to solving the principal–agent problem in the authoritarian context sheds important light on these regimes’ logic of operation. Recent studies in comparative authoritarianism have emphasized how institutional designs can bolster regime resilience by aligning the interests of local agents with those of the central leaders. Thus, in one-party regimes, rulers use regular multiparty elections to minimize shirking on the part of local party cadres, who must campaign hard to turn out votes for the ruling party in exchange for greater upward mobility (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006; Gandhi and Lust-Okar Reference Gandhi and Lust-Okar2009). In communist countries devoid of electoral competition, monitoring of local officials is said to depend partly on a citizen complaint system that provides information about local-level corruption and allows central leaders to intervene on behalf of the petitioners (Dimitrov Reference Dimitrov and Dimitrov2013). In the case of China, many scholars argue that an appointment system that links promotion to economic growth has successfully motivated local officials to pursue rapid development.Footnote 1

This article's findings add a cautionary note to the often-made argument that stable institutions are effective in fostering top-down control in authoritarian regimes. An important component of the CCP's routine bureaucratic management—the cadre rotation system—appears to have much less effect on enforcement results than mobilization campaigns initiated by the center. Authoritarian rulers’ dependence on ad hoc mobilization stems from their deep suspicion of robust institutions which, by definition, generate binding constraints on political behavior. Even when institutions were designed primarily to tie the hands of local agents, their tendency to produce rule-based, predictable behavior is at odds with the dictator's demand for maximum responsiveness from lower-level officials. Therefore, although institution-building can be an option to control state agents in authoritarian regimes, the dictator's commitment to this approach will remain half-hearted, and campaign-style mobilization will continue to be an essential instrument at his disposal.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The next section explores the determinants of subnational anticorruption efforts from the perspective of both routine personnel management and periodic mobilization. This is followed by an introduction of China's main anticorruption agencies, the knowledge of which allows us to use different indicators to measure the strength of enforcement. The empirical section then draws upon an original dataset to explore the effects of cadre rotation and shifting central priorities on anticorruption enforcement. The final section discusses the findings and concludes the paper.

2 CADRE ROTATION, CENTRAL AGENDA-SETTING, AND BUREAUCRATIC CONTROL

The CCP's top leaders acknowledge that rampant corruption, with its negative effects on economic growth, upward social mobility, and the ruling Party's internal cohesion, poses an alarming threat to the regime's legitimacy. Therefore, simultaneous with the launching of market-oriented reform in the late 1970s, China has adopted a multi-pronged strategy to combat corruption. For example, extensive administrative reforms were implemented to reduce the government's regulatory authorities and limit the officials’ rent-seeking opportunities. Moral education that uses study sessions and meetings to indoctrinate Party officials with communist beliefs also constitutes a mainstay of the CCP's anticorruption efforts (He Reference He2000).

However, the Chinese leaders understand, quite correctly, that the root causes of corruption lie in the inability of the Party organization to effectively oversee its agents at various levels. For one thing, Maoist-era mass campaigns that mobilize ordinary citizens to denunciate and police Party officials were repudiated in the reform period for their disruptive effects on social stability (Manion Reference Manion2004, 160). In the meantime, the media and civic groups are still under tight government control and only play a timid role in holding the officials accountable (Gallagher Reference Gallagher and Muthiah2004). The problem of monitoring is also exacerbated by the multilayered structure of the Chinese state that governs a territory of vast size. Geographical distances and the need to communicate through a multileveled hierarchy magnify information asymmetry between central and local governments (Wedeman Reference Wedeman2001).

As noted earlier, the CCP's strategies to control its far-reaching bureaucracy can be classified into two broad categories: routine bureaucratic management and campaign mobilization. Among the CCP's various routine management techniques, we choose to examine the potential effects of the cadre rotation system for two reasons. First, the Party's official documents state explicitly that corruption control is one of the main goals the rotation system was intended to achieve.Footnote 2 Second, unlike some other forms of management, the rotation system lends itself to systematic analysis as the different intensity with which it is practiced across provinces can be easily quantified. The rest of this section discusses each mechanism of agency control in greater detail.

2.1 Cadre rotation

Post rotation as a method of bureaucratic control is a centuries-old practice developed by China's imperial dynasties to manage a sophisticated civil service. To prevent the development of undue attachment or associates, civil servants were prohibited from serving in their home province and were rotated frequently, with the usual term of office being three years (Sterba Reference Sterba1978, 72). Since the founding of the CCP regime, the Party has continued to use its monopoly of personnel assignment to rotate officials across localities as well as between the central and local governments. Detailed regulations have been promulgated to guide the transfer of Party officials. For example, Party leaders with substantial responsibilities cannot hold the same position for more than ten years, and rotation should focus on certain key functional areas such as personnel and law enforcement.Footnote 3 In theory, there are several reasons to expect cadre rotation to enhance top-down oversight and anticorruption enforcement.

First, compared to cadres whose careers have been confined to the same locality, rotated officials generally enjoy higher upward mobility. In recent years, the CCP has increasingly emphasized leadership experiences in multiple provinces as a prerequisite for assuming top national posts (Li Reference Li2008). Thus, the transfer to a different jurisdiction can be interpreted as a signal of forthcoming promotion, inducing the rotated officials to execute the superior's policies more zealously.

Second, rotation reduces officials’ attachment to existing local networks that are prone to organized, syndicated corruption. During the reform period, corruption in the Chinese bureaucracy has increasingly acquired a collective nature (Gong Reference Gong2002; Guo Reference Guo2008). Collaboration in massive corrupt activities generates more illicit gains and involves participants in different fields to smooth the way and cover up the operation. To the extent that officials are themselves immersed in corruption network, they are incapable of tackling corruption seriously. Because rotated officials are assigned to serve a short spell in an unfamiliar locality, they are more likely to be detached from existing networks and take harsh measures against organized corruption.

Lastly, a related benefit of rotation is to improve information flow to the center. Compared to those who have served long periods in a locality, rotated officials have less incentive to cover up ongoing corruption since they will not be held accountable for such corrupt activities. In a study of the management of the American forest service, Kaufman found that no matter how successfully a ranger can conceal his malpractices from his superiors, he cannot hide them from his successor. Indeed, to avoid becoming complicit in pre-existing deficiencies, the successors have strong incentives to bring the wrongdoings to the superiors’ attention (Kaufman Reference Kaufman1967, 155–156).

Before we proceed with the analysis, it is informative to get a sense of the scale of provincial official rotation. The discussion of this article focuses on the transfer of outsiders to serve in the provincial CCP standing committees (PSC)—the highest provincial decision-making body. This is because cross-provincial transfer is primarily applied to leaders at the PSC level, as cadres at lower levels are predominantly natives with no outside experience. Composed of 10–15 members, the PSC incorporates the incumbents of the most powerful provincial posts such as the Party secretary, the governor, and the heads of key functional departments. To illustrate the extent of cross-provincial rotation, I define “outside” as an official who, at the time of becoming a PSC member in a given province, has spent a longer period of his career outside the province than within it. Anyone who does not meet this criterion is coded as a localist. Data on the PSC members of China's 31 provincial-level units from 1992 to 2012 are collected and coded, with Figure 1 showing how the average proportion of outsiders in the PSCs have evolved during this period. Clearly, the proportion of outsiders started a secular trend of increase after 2000 until it reached a height of 50 percent in 2011. This upward trend presents strong evidence that the center has strengthened its control over the make-up of provincial leadership.

Figure 1 Average proportion of outsiders in the PSC: 1992–2012

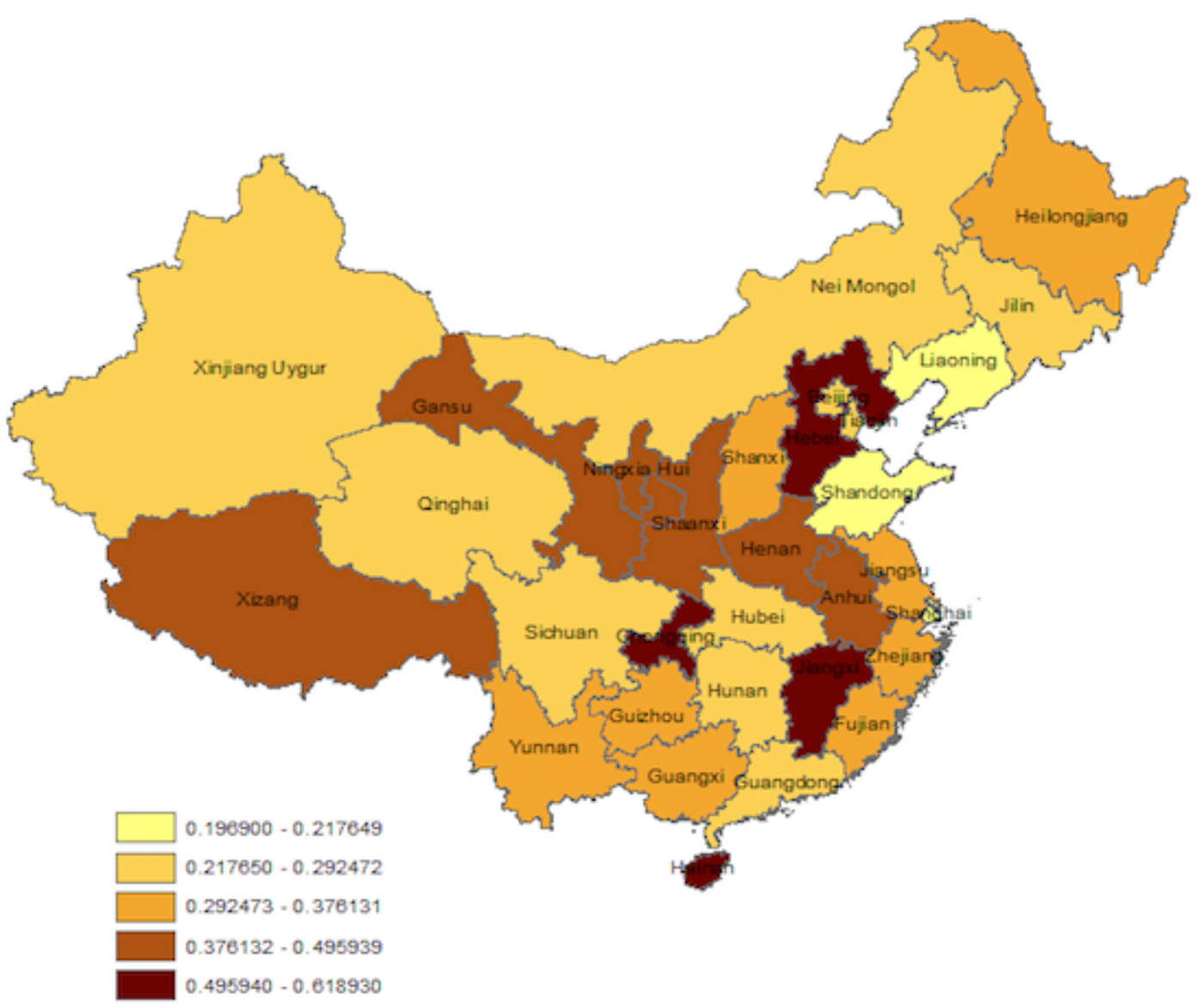

To see the cross-provincial variation in the proportion of outsiders over the studied period, we turn to Figure 2. In this map, shadings of different depth are assigned to the provinces based on the average proportion of outsiders in the PSCs between 1998 and 2012. As the map shows, the practice of rotation has been exercised quite unevenly across the provinces. At one end of the spectrum, provinces such as Hainan have been dominated by outsiders who claim an average of 62 percent of the PSC seats. At the other, Shanghai and Liaoning have seen the average proportion of outsiders stay at around 20 percent over this period. The temporal and cross-sectional variation in the intensity of rotation allows us to examine the effects of this policy on anticorruption. If rotation can indeed enhance the center's ability to supervise provincial officials, those provinces governed by a greater proportion of centrally assigned outsiders should exhibit stronger enforcement against corruption.

Figure 2 Regional variation in the proportion of outsiders in the PSC: 1998–2012

Hypothesis 1: Increase in the proportion of outsiders in the PSC will lead to more vigorous anticorruption efforts.

Whether this hypothesis is plausible depends on several factors. One possible complication is that the proceeds from corruption might outweigh the payoff of promotion. Also relevant is the amount of time it takes for an outsider to be absorbed into the local network and become indistinguishable from the native cadres. If the outsiders are rapidly “localized,” the center is simply unable to rotate them frequently enough to preserve their detachment. Most importantly, the hypothesis assumes that provincial leaders enjoy considerable autonomy in determining the intensity of anticorruption efforts. As we will see below, making this assumption may be problematic because the central government plays a key role in setting the pace of anticorruption activities.

2.2 Central agenda-setting and anticorruption campaigns

While institutional reforms such as cadre rotation are considered by some Party insiders as the appropriate means to tackle corruption (Harding Reference Harding1981, 9), throughout the Party's history there has been another intellectual current that rejects the bureaucratic mode of management and instead emphasizes leadership initiative, mobilization, and improvisation. Proponents of the mobilization ethos regard “policy-making as a process of ceaseless change, tension management, continual experimentation, and ad-hoc adjustment” (Heilmann and Perry Reference Heilmann, Perry, Heilmann and Perry2011, 4). This technique of governance calls for enormous leadership discretion to cope with changing environment and contrasts sharply with the bureaucratic and legalistic approach.

In the realm of anticorruption, the logic of mobilization is manifested in the periodic launching of campaigns to temporarily strengthen enforcement. Every so often, central Party leaders make speeches and circulate directives to underscore the severity of official corruption and demand increased anticorruption enforcement. The issue of corruption gains salience in state-controlled media, reporting centers and hotlines are set up to facilitate pubic denunciation, and local leaders are urged to investigate more cases of corruption. After a period of hyper enforcement, however, the central leaders would call an end to the campaign, adopting a more modest tone in their speeches to imply a shift in priority. At the end of the 1995 campaign, for example, the CCP general secretary Jiang Zemin announced that “we are gradually finding a way, centered on the task of economic construction, to integrate the anticorruption struggle with reform, development, and stability” (Manion Reference Manion2004, 162).

On a general level, periodic campaigns are aimed at deterring corruption by increasing the costs of official misbehavior. As cadres decide rationally whether to take bribes, they are forced to take into account the risks of hyper enforcement which may occur at an undetermined point of time (Wedeman Reference Wedeman2005, 96–97). More specifically, there are three proximate causes of focused, intense anticorruption campaigns. First, massive but isolated scandals that erupt in a particular locality may alert the central leaders of widespread corruption and prompt them to launch nationwide enforcement campaigns. The surge in enforcement figures between late 1998 and 2001, for instance, was apparently triggered by the exposure of shocking smuggling and corruption scandals in Fujian province (Li 2004). Surgical campaigns thus allow the central leaders to formulate rapid, nationwide responses to the “fire alarms” sounded in the localities. Second, anti-graft campaigns might be an instrument utilized by the center to achieve purposes related to macroeconomic control. During the post-Mao period, performances of provincial officials are primarily evaluated in terms of local economic growth. These officials therefore have strong incentives to pursue excessive investment that contributes to economic overheating and inflation. When inflationary pressure mounts, the center often accompanies its austerity measures with a new round of anticorruption campaign, effectively using disciplinary measures to force local compliance with central policies (Quade Reference Quade2007). Lastly, campaigns provide the CCP's paramount leader, the general secretary, with a legitimate channel to consolidate power status by removing political foes and creating vacancies for his loyal supporters (Fu Reference Fu2014). The large-scale personnel reshuffle entailed by rectification campaigns allows the paramount leader to expand the presence of his supporters with much greater efficiency than through routine appointment procedures.

Regardless of the immediate causes of anticorruption campaigns, once the center announces the initiative, local responses are often swift. For example, after Beijing launched a new campaign in August 1993, the anticorruption agency in Jiangsu province reported that “disciplinary and inspection organs at all levels further strengthened leadership over case investigation; allocation of personnel, responsibilities, and funding were all guaranteed.”Footnote 4 In Jilin province, enforcement gained momentum immediately after August: “(In 1993) disciplinary and inspection organs received 48,921 reports, and 26,264 reports (53.7%) were received between September and December. 5340 cases were filed, and 2035 (38.1%) were filed during the same period.”Footnote 5

If the CCP's anticorruption system is highly centralized and carefully coordinated, the observable implication is that enforcement level should ebb and flow in tandem across the provinces in response to shifting central signals. In other words, when the Party center conveys demands for heightened enforcement, anticorruption efforts will go up throughout the country. Conversely, when the center signals a shift of priority to other matters, anticorruption in all provinces will wane together. This leads to our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Levels of anticorruption enforcement in the provinces are positively correlated with the degree of central emphasis on anticorruption work.

It should be noted that the bureaucratic mode management and cyclic mobilization need not be mutually exclusive. It is possible that the two mechanisms of agency control can both be effective and supplement each other. The centralized nature of the anticorruption system, however, suggests that mobilization is likely to dominate the pattern of enforcement and deprive provincial agencies of operational autonomy, thereby undermining the effectiveness of cadre rotation. Moreover, as Jowitt (Reference Jowitt1992) incisively observed, Leninist regimes have an innate tendency to embrace the “mobilization ethos” that leads them to pursue rapid realization of ambitious targets under tight time constraints. This obsession with campaign mobilization makes it difficult for Leninist parties to develop Weberian bureaucratic norms and procedures. Before we can adjudicate these claims with data analysis, we need to discuss how to measure anticorruption enforcement. The next section outlines the main features of China's anticorruption agencies and explains how different indicators can be used to capture the degree of enforcement.

3 MEASURING ANTICORRUPTION

Hidden from public view and politically sensitive, corruption and its related social phenomena are notoriously difficult to measure. For a long time, “corruption was something to live with, something to gossip about, and something to complain with, but not something to reflect upon” (Krastev Reference Krastev2004, 23). Like corruption itself, anticorruption enforcement has multiple dimensions, each of which presents unique challenges for observation and measurement. In this study, we use two indicators to measure anticorruption at the provincial level:

-

• The number of senior officials disciplined by the Party (DIC cases).

-

• The number of senior officials investigated by the government procuratorate (procuratorate cases).

Below I provide a sketch of the two main anticorruption agencies operating within China's one-party system. Their different missions and area of focus enables researchers to capture important aspects of the regime's enforcement efforts.

3.1 China's dual-track anticorruption system

An important feature of China's anticorruption regime is the coexistence of a specialized agency in the Party apparatus and its counterpart in the state's judicial system. This organizational structure was created to ensure that the Party has the final say over important policies and can supervise their implementation by state apparatus. Thus, on the Party side, a Disciplinary Inspection Committee (DIC) is placed within every Party branch to enforce Party disciplines. On the government side, a procuratorate is located in every territorial unit at or above the county level. Both agencies were first established after the founding of the People's Republic in 1949, but their operations were disrupted during the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976. After a decade of political turmoil, the Party's DIC and government procuratorate were soon reinstated to enforce anticorruption rules as the regime embarked on market-oriented reforms (He Reference He2000, 266). In terms of organizational location, both agencies have a national office sitting at the top of a hierarchy that extends down to lower levels of government.Footnote 6

As a special-purpose agency within the Party apparatus, the DIC enforces the Party's regulations by accepting public accusations, conducting investigations, and imposing penalties on disciplinary violations. The CCP's disciplinary requirements cover a wide range of political and economic offenses, not all of which involve corruption as conventionally defined (Wedeman Reference Wedeman2012, 147). For example, CCP members are prohibited from forming factions within the Party, refusing to promote “reform and opening” policies, resisting personnel decisions on appointments or transfers, and so forth. These transgressions are apparently more related to organizational indiscipline than abuse of power for private gain. However, the reform period has seen the DIC adapting its mission to focus on rampant corruption among Party members. Internal Party rules regarding disciplinary inspection devote most attention to various forms of economic misconducts such as embezzlement of public assets and bribery, and the majority of cases investigated by the DIC now involve economic violations instead of ideological or moral lapses (Manion Reference Manion2004, 126–127). Since the early 2000s, the DIC has been firmly established as the chief coordinator of the Party's various anticorruption efforts (Gong Reference Gong2008, 147).

The procuratorate, on the other hand, is assigned the responsibility of fighting corruption according to China's Criminal Law. By the Constitution, the procuracy is an independent arm of government with equal authority to the executive branch. It supervises criminal investigation, approves arrests, and prosecutes criminal cases. Most importantly, it also has exclusive authority to investigate and prosecute “duty crime” (zhiwu fanzui), an umbrella term that covers a full array of specific crimes involving officials. According to the 1997 Criminal Law, duty crimes include three broad categories: embezzlement and bribery, malfeasance, and civil rights violations (Wedeman Reference Wedeman2004, 910–914). While the legal definition of duty crimes may not be totally coterminous with conventional conception of corruption, it is a reasonable approximation of the latter. With some possible exceptions, such as leaking state secrets and violating religious freedoms, the majority of duty crimes are consistent with common understanding of official corruption.

Differences in institutional and legal status determine that the DIC and the procuratorate apply different methods of punishment for corrupt activities. In general, in-house disciplinary actions meted out by the DIC are significantly milder than criminal punishments in the judicial system. Disciplinary actions, in order of increasing severity, consist of warning, serious warning, dismissal from party positions, probation within the party, and expulsion from the party.Footnote 7 By comparison, the criminal system imposes much harsher punishments such as fixed-term imprisonment, life imprisonment, death penalty with suspension of execution, and death penalty (Manion Reference Manion2004, 128). The two systems of punishment are linked in that the standards for expulsion from Party parallel the threshold for criminal punishment (Manion 2005, 130). In the case of bribery, for example, Party regulations require expulsion for offenses involving more than 5,000 yuan, which is the threshold for legal punishment. In fact, the DIC is required to forward the case files to the procuratorate in a timely manner if its investigations reveal evidence of criminal offenses.Footnote 8

If relevant laws and regulations are enforced independently and faithfully, the nature of punishment imposed should reflect the severity of misconduct: minor wrongdoings are only met with disciplinary measures whereas severe corrupt activities are subject to criminal punishment. However, due to the Party's routine intervention into the agencies’ operation, the method of punishment indicates not so much the objective degree of misconduct as the protection and favor available to the corrupt official from high-ranking Party leaders. At each level, the Party committee exercises leadership over anticorruption agencies in numerous ways, most importantly through the appointment of agency officials and the control over agency budgets (Manion Reference Manion2004, 124–6). Moreover, when it comes to the investigation of corruption cases, the Party's DIC routinely initiates the process and only transfers cases to the procuratorate at a time it considers “appropriate” (130). As such, the dual-track system allows the Party to retain maximum discretion over anticorruption enforcement: the Party can decide not only whether to initiate an investigation but, in the midst of a DIC investigation, whether to forward the case to the judicial system. Failure to transfer a case, which usually leads to the substitution of disciplinary measures for criminal punishment, can be used to protect Party members from the law. This institutional arrangement enables the Party leaders to fine-tune the degree of enforcement and, when necessary, shield their political clients from harsh punishment.

Although both agencies are under the firm control of the Party committee, relatively speaking the procuratorate tends to enjoy more independence from the Party's tight grip. As part of the judicial system, the procuratorate must to some extent adhere to due process of law when conducting investigation, evidence collection, and prosecution. The DIC, on the other hand, is more widely perceived as the CCP's political instrument and therefore under much less constraint to follow state or Party statutes. Moreover, while a trend of professionalization is present among members of the procuratorate, DIC officials are unabashed political appointees with low levels of legal training (Sapio Reference Sapio2008, 22–3). Given these factors, the DIC is expected to be more responsive to the Party's shifting emphasis on anticorruption enforcement than the procuratorate, a point to be tested in the empirical analysis.

3.2 Measuring anticorruption with two indicators

China's dual-track system of sanctioning corruption allows us to measure enforcement with the figures of both disciplinary and criminal punishment. Specifically, I use two publicly available figures: the number of senior officials disciplined by the DIC and the number investigated by the procuratorate. “Senior officials” in this study are defined as those whose bureaucratic ranks are at or above the county level. The analysis focuses on senior officials because cases involving them are more likely to warrant the attention of provincial leaders than ordinary cases. Sitting at the mezzo level of the bureaucracy, the county level officials serve in a variety of positions ranging from the top leaders of a county to division chiefs in a municipal government to bureau chiefs in a provincial government. Senior officials have acquired enough political importance to require additional caution when their cases are handled. In criminal investigations, for example, clues related to these cases must be filed to the provincial procuratorate for record.Footnote 9 Therefore, the number of corrupt county-level officials that are punished by disciplinary or criminal measures conveys rich information about the strength of enforcement.

It is intuitive to measure anticorruption using the number of punished officials, which demonstrates vividly a regime's resolution to keep its agents honest. For example, Indonesia's anticorruption agency KPK was considered to be much more effective than its Philippine counterpart due to the larger number of high-ranking officials prosecuted and convicted by the former (Bolongaita Reference Bolongaita2010). However, an obvious problem of this approach is the conflation of enforcement with the objective level of corruption. It is unclear whether high level of prosecutions should be interpreted as low tolerance for corruption or the existence of rampant corruption. In the Chinese context, though, we are confident that the enforcement figure is a poor indicator of the actual level of corruption because it is highly sensitive to the shifting emphasis that Party leaders place on anticorruption. To illustrate this point, I show in Figure 3 the annual number of disciplined senior officials in Anhui province from 1993 to 2012. Based on common sense, the zigzag shape of the line is much more likely to reflect the vicissitudes in policy priority than changes in objective corruption. For instance, it is simply implausible that the level of corruption had experienced a threefold increase between 1993 and 1997 or improved so dramatically after 2009. We are therefore sympathetic to the view that, in China, “a higher number of cases would actually indicate better governance and less corruption, as perpetrators are more likely to be brought to justice” (Malesky Reference Malesky2014, 9).

Figure 3 Number of senior officials disciplined by the DIC, Anhui Province

While the number of punished officials is by no means an accurate reflection of the objective corruption conditions, we cannot assume that these two factors are independent of each other, either. As the actual level of corruption rises, more officials are likely to be exposed by the watchdog agencies even if the policy emphasis on anticorruption remains constant. Therefore, an empirical analysis seeking to explain the dynamic of enforcement must find some way to control for underlying levels of corruption. Measuring objective corruption, however, is well known to be exceedingly challenging. Researchers have used survey methods to generate perception and experience-based measures, although neither approach is immune to significant biases (Sampford Reference Sampford2006). Moreover, longitudinal survey data on corruption broken down to the provincial level is not yet available for China.

Although objective corruption is not directly observable, we could draw upon existing knowledge about the nature of corrupt activities in China to generate proxy variables that capture different dimensions of official abuse of power. This paper uses three such proxies, each of which is intended to indicate the severity of corruption in a major area of government activities. First, the real estate (RE) industry has often been described as the most corrupt sector of the Chinese economy, as graft pervades the process of transferring land use rights to private developers. In China, the land is state-owned and local governments hold the de facto right of land disposal. The need of RE companies to acquire land for commercial use creates a hotbed for bribery (Zhu Reference Zhu2012). While official regulations require all companies to obtain land through open tender, auction, or listing of land (TAL), the process is often rigged to benefit well-connected, large-scale firms. It is therefore reasonable to assume that, where land transfer deals play a bigger role in the local economy (Hsing Reference Hsing2006), there will also be more opportunities for corruption. Accordingly, we use the amount of revenue accrued from land transfer as a percentage of GDP as the first proxy for actual levels of corruption.

Relatedly, for the developers to move ahead with their projects, they must acquire certificates and permits from various government agencies, and it is often at the discretion of individual officials to determine whether a project has met certain criteria to receive the permits. As a result, “many entrepreneurs send bribes just to ensure that the files will be processed on time or faster and that the construction scheme will not be questioned for ambiguous reasons” (Zhu Reference Zhu2012, 256). Developers also bribe urban planning officials to adjust construction standards so that more profits may be generated. Thus, a heated, fast-growing RE market generally provides more opportunities for money to change hands between developers and regulators. In line with this analysis, we use the growth rate of real estate investment as the second proxy for the actual scale of corruption.

Finally, previous research has shown that objective corruption can be partly inferred from the composition of government expenditure. For example, studies find that corruption reduces the proportion of government spending on education (Mauro Reference Mauro1998; Gupta, Davoodi, and Alonso-Terme Reference Gupta, Davoodi and Alonso-Terme2002). This is because corrupt officials prefer to spend more on items for which it is easier to levy substantial bribes and maintain secrecy such as large infrastructure projects and sophisticated defense equipment. The proportion of government expenditure devoted to education, therefore, is chosen as the third proxy.

To summarize, this study measures anticorruption with two indicators that capture different dimensions of enforcement. The number of DIC cases indicates the extent to which the Party uses relatively lenient measures to discipline its members; the number of procuratorate cases reflects the Party's tendency to impose criminal punishment on corrupt officials. The purpose of using different measures is to generate persuasive evidence through a triangulation of measurement processes. If the results of analysis survive multiple imperfect measures, more confidence can be placed in them (Webb et al. Reference Webb, Campbell, Schwartz and Lee1966, 3). For both indicators to be valid, the key assumption is that enforcement outcomes are mainly a function of the CCP's policy emphasis rather than actual level of corruption. To control for the impact of objective corruption on enforcement, we employ three proxy variables that indicate the amount of corruption in the land-transferring process, the real estate regulatory environment, and government expenditure, respectively.

4. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

4.1. Data and method

We assembled a panel dataset to examine the determinants of anticorruption vigor in China's provinces. As explained above, the dependent variables are the two indicators of enforcement: the number of senior officials punished by the DIC and investigated by the procuratorate per 10,000 public employees, respectively. Both numbers are normalized by the size of public employment so that they are comparable across provinces.Footnote 10

The main source of data is the provincial yearbooks that include work reports from both the provincial DIC and procuratorate. The DIC work reports detail the number of Party members disciplined in a given year and, among them, how many are at or above the county level. Similarly, the procuratorate regularly reports the number of officials, including the senior ones, for whom a case has been filed and investigated. Annual corruption data are collected for China's 31 provincial units from 1998 to 2013. The year 1998 is selected as the starting point because China promulgated a new Criminal Law in 1997 that redefined criminal corruption, making the figures after 1997 incomparable with previous years (Manion Reference Manion2004, 141–142). 2013 is the last year for which provincial yearbooks are consistently available at the time of writing.

Figure 4 depicts the temporal trend of the indicators of anticorruption on the national level. As can be seen, the enforcement activities by the DIC display substantial fluctuation during the studied period. The normalized number of senior officials disciplined by each province (solid line) increased steadily until 2001, dropped significantly from 2004 to 2006, stagnated between 2006 and 2012, and rose sharply in 2013. In comparison, the number of criminal investigations (dotted line) has remained relatively stable, although it also peaked around 2002. The greater temporal variation in the amount of DIC cases suggests that the Party agency is more susceptible to periodic campaigns than the procuracy, which enjoys more autonomy. Overall, the trends suggest three episodes of relatively strong enforcement: 1998–2001, 2007–2010, and 2013.

Figure 4 National trend in anticorruption indicators: 1998–2013

Using linear regression analysis, we estimate the following model:

In this equation, νi stands for the unit-specific effects, and εit is an idiosyncratic error term. Xit is a matrix of the main explanatory variables. The first variable is the proportion of outsiders in the PSC.Footnote 11 If more intense rotation contributes to vigorous anticorruption enforcement, the coefficient for this variable should be positive.

The second hypothesis states that enforcement outcome in one province is positively correlated with central emphasis on anticorruption efforts. As mentioned above, the center's policy agenda is conveyed through speeches by top Party leaders and documents issued by the central government. Based on information from major official statements, we come up with three separate measurements of central emphasis. First, the central organ of the DIC (the CDIC) holds a meeting at the beginning of every year to assign work tasks for the coming year. By convention, at the conclusion of that annual meeting, the CDIC would issue a communiqué that follows a rigid text structure. It first summarizes the speech delivered by the CCP General Secretary at the meeting, and then reviews the accomplishment of the past year before laying out the broad directions of next year's work. Once promulgated, the communiqué will be studied by Party leaders at all levels as a guideline for anticorruption efforts. We assume that when the central government intends to step up anticorruption enforcement, the Party leadership will direct the meeting's writing group to draft a more elaborate communiqué. Thus, the word count of the full document forms the first measure of central policy emphasis.

One may object to the first measure on the grounds that it only captures the length of the communiqué without showing the saliency attached to case investigation. Conceivably, a document could contain lengthy discussions of cosmetic reforms or precautionary measures instead of emphasizing the punishment of corrupt officials. To address this concern, the second measure consists of the word count of those sentences that explicitly relate to enforcement. These sentences include key words such as “investigate,” “punish,” “discipline,” and “penalize.”Footnote 12 It is possible that the appearance of these sensitive words will provide a clearer signal to lower-level anticorruption agencies regarding the center's intent.

The third measure draws on the government work report delivered by the Chinese Premier to the opening meeting of the annual National People's Congress, which is held in early March. In the Premier's comprehensive speech, the need to crack down on corruption is only one of many national issues addressed. The portion of the report that is devoted to anticorruption, however, varies from year to year. We analyze the content of the speeches and count the percentage of the texts that touches upon the topic of corruption.Footnote 13 It should be noted that, under the current division of labor within the Chinese political system, the State Council chaired by the Premier is mainly charged with managing the economy and implementing the decisions made by the ruling Party. When it comes to steering the nation's anticorruption efforts, the Party remains the dominant player. We therefore expect that the Premier's work report and the policy signal it contains will have less impact on enforcement patterns than the CDIC communiqué.

Note that we have deliberately chosen policy announcements made at the beginning of a year to ensure that they are exogenous to the actual enforcement outcome of that year. The values of the three variables over time and the Pearson correlation coefficient between them are shown in Table 1. Unsurprisingly, the communiqué length measure is highly correlated with the communiqué key word measure. The Premier's speech measure, however, is only weakly correlated with the other measures, suggesting that the Party and government do not always synchronize their signals regarding anticorruption.

Table 1 Measures of central policy emphasis on anticorruption: 1998–2013

The correlation coefficient is 0.567 between the first and second measure, 0.157 between the first and third measure, and 0.326 between the second and third measure.

Data from: The Premier's speech can be found at www.gov.cn/test/2006-02/16/content_200719.htm, accessed May 22, 2015. The DCIC Communique are printed in the periodical Supervision in China (Zhongguo Jiancha).

The matrix zit represents a wide range of confounding factors that are expected to affect both the outcome variable and explanatory variables.Footnote 14 First, as discussed above, the actual severity of corruption could have an impact on enforcement outcomes. Meanwhile, deterioration in actual corruption could also prompt the appointment of more outsiders to provincial posts and/or a nationwide campaign to crack down. The previous section has introduced three proxy variables for objective corruption: revenue collected from land transfer as a percentage of GDP (land revenue), the growth rate of real estate investment (RE investment), and the proportion of government spending on education (education spending).

Other control variables include the GDP per capita and degree of urbanization of each province, a dummy variable that indicates whether a provincial unit is a Centrally Administered Municipality (CAM), and another dummy that equals one if a provincial unit is a designated “autonomous regions” owing to the concentration of ethnic minorities. These covariates are relevant controls because, on the one hand, they can be reasonably expected to affect the level of enforcement. Economic development and urbanization tend to increase the spread of education and literacy, raising the likelihood that corrupt officials will be noticed and challenged (Treisman Reference Treisman2000; Sung Reference Sung2004; Del Monte and Papagni Reference Del Monte and Papagni2007). The four CAMs—Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing—have been placed under the center's direct control due to their exceptional importance in economic development and national security. It is plausible that the center's intent to closely monitor these megacities (Su and Yang Reference Su and Yang2000) will lead to more stringent anticorruption enforcement. In ethnic minority regions such as Xinjiang and Tibet, the pressing threat of ethnic tension and secession is likely to lead the authorities to treat anticorruption with special caution to avoid political instability.

On the other hand, the economic and political characteristics of the sub-national units could also determine how many centrally appointed outsiders they receive. Intuitively, provinces with more developed economies or elevated political statuses may serve as major destinations of outsiders as the center strives to tighten its control over these key localities. One notable exception might be the ethnic minority regions where a greater proportion of local minority cadres could serve in the PSCs, presumably to showcase Beijing's inclusive personnel policy. The descriptive statistics for the variables are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 Summary statistics

In addition to probing the impact of anticorruption campaigns on enforcement patterns in the provinces, it is also worth examining the possibility that local conformity to central priorities may not be the same across all provinces. The logic of central control would imply tighter scrutiny imposed on some provinces with greater political or economic importance. To inquire whether the pressure to conform is contingent on provincial characteristics, we use CAM status as a proxy for political importance and GDP per capita for economic importance. Under the heat of intense foreign media attention, the CAMs play a crucial role in showcasing China's reform and development to the outside world. The fact that the Party chiefs of these four megacities are guaranteed a seat in the Politburo, a privilege denied to most other provincial leaders, further underscores the political salience of the CAMs.

A common problem that arises when we estimate models with panel dataset is the existence of unmeasured factors associated with each cross-sectional unit. One solution to this problem is to use the random effects model that, instead of computing a fixed unit-specific intercept, assumes that the unit effect follows a specific probability distribution. This approach will allow us to include time-invariant variables of substantive interests.Footnote 15 Further, to address the presence of autocorrelation within time-series data, I estimate models with first-order autoregressive disturbance (Greene Reference Greene2012, 966–969). This method first uses an interactive procedure to estimate the correlation of the error terms, ρ. Using this estimate, the dependent and independent variables are transformed to remove the serial correlation.

4.2 Results of analysis

Results from the random effects models are presented in Table 3. Models 1 to 3 report the effects of independent variables on DIC cases, each with a different measure of central emphasis. Models 4 to 6 are identical to the first three models except that the dependent variables are changed to procuratorate cases. The first thing to note is that none of these models produce evidence supporting the first hypothesis: the proportion of outsiders has no statistically significant impact on anticorruption.

Table 3 Effects of cadre rotation and central emphasis on provincial enforcement

Ramdom-effects linear models with an AR(1) disturbance, t statistics in parentheses. * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

When it comes to the effects of central agenda-setting, models 1 and 4 show that the length of the CDIC communiqué has positive and statistically significant effects on both DIC and procuratorate enforcement. Increasing the communiqué length from its mean (3156 words) to maximum value (4468 words) is associated with 0.39 more senior officials disciplined per 10,000 public employees (p < 0.01), and the same change in the explanatory variable will lead to 0.13 more senior officials subject to criminal investigation per 10,000 public employees (p < 0.05). Measuring central signal with enforcement-related key words in the communiqué, the results show that such signals have a statistically significant impact on DIC cases (model 2), but not procuratorate cases (model 5). The fact that central initiatives tend to exert more influence on the behavior of DIC is consistent with the theoretical expectation that the DIC would be more responsive to directives from its Beijing headquarters than the procuracy, as explained in Section 3.1, above. Finally, the proportion of Premier's work report devoted to anticorruption does not seem to have any impact on enforcement. This again is in line with the observation that anticorruption is mostly under the purview of the Party, and therefore the content of the government work report has little bearing on how anticorruption agencies perform their duties.

Turning to the control variables, it is noticeable that indicators of objective corruption are generally uncorrelated with enforcement outcomes. One exception appears in model 3, wherein the scale of land transfer deals is found to have a positive impact on DIC cases (p < 0.05). Increasing spending on education, which implies less corruption in the area of government expenditure, seems to reduce procuratorate cases in models 5 and 6, but the relatively large p values (between 0.05 and 0.10) raises the likelihood of making type I error considerably. In all other cases, the three proxies of objective corruption do not appear to be relevant in explaining the outcome of interest.

The negative effects of GDP per capita on the number of DIC suggest that the Party must maintain a delicate balance between economic development and taking a tough stand on corruption. In more wealthy provinces, the anticorruption agencies might be instructed to tread more carefully, so that the momentum of economic growth will not be thwarted. There is also strong evidence that the Central Administrated Municipalities are subject to tighter corruption control. Holding other variables constant, being a CAM will increase the number of DIC cases per 10,000 public employees by about 2.80 (p < 0.05) and procuratorate cases by about 2.30 (p < 0.01). This finding is consistent with the received wisdom that densely populated cities pose serious threats to authoritarian survival by facilitating collective actions, and that autocrats take active measures to manage discontent in the cities (Wallace Reference Wallace2014). On the other hand, enforcement tends to be milder in ethnic minority regions, which will lower the normalized number of procuratorate cases by about 0.80. (p < 0.05). There are two possible explanations for this discrepancy. First, cadres who are transferred to work in poor, remote minority regions are compensated by lower risk of exposure. Second, enforcement against native minority cadres is moderated to avoid exacerbating ethnic tension.

The foregoing analysis has revealed that anticorruption vigor at the subnational level is driven by central policy signals communicated through the annual CDIC meeting communiqué, among other things. The investigation now moves on to probe whether the effects of central policy signals vary across provinces with differential political and economic importance, as we anticipated. To do this, the communiqué length variable is interacted with CAM status and with provincial GDP per capita. If provinces with heightened political or economic values face stronger pressure to comply with central agenda, the coefficients for the two interaction terms should be positive.

Table 4 reports the regression estimates with the interaction terms. In models 1 and 2, we find that the effects of central agenda-setting do not seem to depend on the level of economic development. By contrast, models 3 and 4 report that the interactive effects between communiqué length and CAM status are positive and statistically significant. For a non-CAM province, increasing the communiqué length from its mean to maximum will lead to 0.26 more officials disciplined per 10,000 public employees; for the CAMs, the figure is raised to 1.18. Thus, we find that the four CAMs not only display a higher level of enforcement than other provincial units, but these four cities are also more responsive to changes in central policy emphasis.

Table 4 Effects of central emphasis on provincial enforcement conditional on economic and political importance

Ramdom-effects linear models with an AR(1) disturbance, t statistics in parentheses. * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

5. CONCLUSION

Non-democratic regimes can strengthen agency control by building a rationalized bureaucracy or resorting to cyclic mobilization to curb corruption. These two modes of top-down control may supplement each other; alternatively, one mode of control mechanism may be more effective than the other. Using China as a case study, we find that the ebbs and flows of central priority communicated through official documents have major impacts on enforcement patterns at subnational level, and provincial units with elevated political statuses are under greater pressure to conform. By comparison, routinized rotation of cadres has little influence on the vigor of anticorruption enforcement. Available evidence suggests that the basic framework of corruption control in China follows the logic of cyclic, top-down mobilization instead of routine bureaucratic management. While the intense anticorruption campaigns inevitably contain elements of power struggles among top CCP elites, they can still contribute to the regime's overall interests by eliminating “bad apples” and instilling a renewed discipline in the ruling Party (Shih Reference Shih2016).

Admittedly, this study examined only one type of routine management. Future research may further inquire whether other bureaucratic methods—the design of compensation scheme, the recruitment mechanism, the checks and balances between institutions—can enhance top-down accountability and reduce agency loss. We have reasons to believe, though, that the prevalence of the mobilization ethos can undermine the effectiveness of all types of bureaucratic norms and procedures. The launching of periodic campaigns may appear highly successful in eliciting immediate responses, but it inevitably disrupts the operation of formal rules and institutions (Manion Reference Manion2004), and lower-level leaders must ignore other tasks to fulfill the enforcement quota. Moreover, the unpredictable, ruthless nature of anticorruption campaigns also induces officials to cultivate personal ties with influential leaders for self-preservation, increasing the pervasiveness of factions and informal rules (Pye Reference Pye1981).Footnote 16

Another implication of our study concerns the inefficiencies of a highly centralized disciplinary system. The unchallenged authority of the national government to direct the anticorruption orchestra fosters obedience, passivity, and cynicism among lower-level officials. As a result, the central government is hardly in a position to gather information necessary to adjust anticorruption policies to local circumstances. The ills of centralization are particularly worrisome in a large and diverse country like China, where the nature and severity of corruption may vary greatly across regions. In the final analysis, the lack of institutionalization and efficiency is probably the price a single-party regime has to pay for maintaining a hierarchical, monolithic system.