Introduction

Animal welfare is an essential component of dairy production. As a scientific field, animal welfare originated around 1990 after decades of ethical and scientific debate that really got started after the Brambell report of 1965 (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins1980) and subsequent work in animal-based sciences such as behavior, nutrition, anatomy, and veterinary medicine (Brown and Winnicker, Reference Brown, Winnicker, Fox, Anderson, Otto, Pritchett-Corning and Whary2015). Scientific interest was not the only reason this field developed. The public's concern about how animals were being treated and raised also influenced the formation of animal welfare sciences (Fraser, Reference Fraser1995).

Sectors of animal agriculture, including the dairy industry, have developed systems to evaluate animal welfare. However, global standardization is limited because dairy welfare evaluation programs have been independently created around the world. The programs evaluate dairy farms differently and place unique weights on different components of animal welfare. Despite these differences, evaluation programs have been created to establish a baseline for dairy cattle welfare and to help assure consumers that farmers are being held to a high standard.

To help identify the similarities and differences, we have provided a review of some of the commonly used dairy welfare programs around the world that operate at farm level. These three programs are summarized and compared and are also compared to a new welfare assessment tool. We also offer some commentary on the types of measures that should be included in a dairy farm animal welfare evaluation.

Major programs for welfare evaluation on dairy farms

Although hundreds of welfare evaluation programs exist around the world today, here we consider the European Welfare Quality® Assessment Protocol dairy cattle (WQ), the U.S. National Dairy Farmers Assuring Responsible Management Program (FARM), and the New Zealand Code of Welfare: Dairy Cattle (The Code). Each of these programs is currently being used in its country of origin to evaluate welfare on dairy farms. Along with these three programs, a fourth and upcoming program, the Integrated Diagnostic System Welfare (IDSW), is also considered.

Welfare quality® assessment protocol for cattle (European Union)

Before 2006, the various states of the EU had their own national standards under the supervision of national veterinary systems, with a focus of helping to improve health and hygienic conditions of animals and barns. In 2006, the EU adopted the Community Action Plan on the Protection and Welfare of Animals. The main objectives included defining the direction of animal welfare and promoting welfare principles and animal welfare research (European Commission, 2006). This action plan led the way for the WQ animal research project, which was completed in 2009 with the release of animal welfare assessment protocols. WQ was designed by a team of senior scientists in animal welfare, who were interested in bettering animal well-being on farms across the EU. Taking into account public concerns and market demands, the developers of WQ created on-farm monitoring programs (Blokhuis et al., Reference Blokhuis, Veissier, Miele and Jones2010).

Forty-four universities and institutions were involved in the WQ research project in 20 European countries. From 2004 to 2010, scientists traveled to different farms and tested out possible protocols. The standards of the program were based on the retail requirements of agricultural product sellers, consumer demands, and the rigorous scientific evaluation of the WQ program that occurred before the official release of all animal protocols in 2009 (Blokhuis et al., Reference Blokhuis, Veissier, Miele and Jones2010). The WQ was created with the intention of being used as an assessment tool for third-party verification.

The WQ program has four welfare principles: good feeding, good housing, good health, and appropriate behavior. Within these principles are 12 welfare criteria, and within the criteria are ~30 welfare measures. Each measure is scored on a 0–100 scale. Each criterion is then scored on a 0–100 scale based on the relevant measure scores. The criteria scores are combined to generate a score for each of the four principles, which are again combined to create the final overall assessment score. A farm is then given the classification of excellent, enhanced, acceptable, or not classified based on the final 0–100 score (Welfare Quality®, 2009).

Currently, the WQ is a volunteer program. Dairy processors can choose to use the program and require their producers to become WQ certified. Farms selling their milk to such dairy processors must comply with the WQ standards or sell their milk elsewhere. The WQ program is currently being used on over 270 farms in Spain and Finland. The frequency of audits is defined by the dairy processor that requires the WQ protocol. The dairy processor also makes the final decision on what to do with farms that do not pass, on a case-by-case basis (Blokhuis HJ, personal communication). All costs associated with evaluations are covered by the processor. Milk certified using the WQ protocol remains a niche market, although the potential growth for this program is enormous, with the EU being home to around 23 million dairy cows. WQ could end up being one of the world's largest animal welfare programs.

The WQ project was initially funded by the EU, but since its completion, the project has not received any additional support. The Welfare Quality Network (the group that oversees the WQ program) is working to further develop the parameters of evaluation within the current program, despite the challenge of the high costs of further research. The WQ Network hosts annual day-long seminars in connection to the General Assembly of the WQ Network that are open to anyone who would like to learn more about the WQ program (Blokhuis HJ, personal communication).

Farmers assuring responsible management (FARM) animal care program (U.S.A.)

The first version of the FARM Animal Care program was released in the United States in 2009. It was created as a joint effort between the National Milk Producers Federation (organizer) and Dairy Management Inc. (program initiator). A technical writing group was and is accountable for writing and revising the FARM manual. This group comprises animal scientists, veterinarians, dairy farmers, and industry representatives (FARM, 2019). The wide diversity of the group helps the program evolve alongside the latest research (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Cook, Darr, DeCoite, Doak, Endres, Humphrey, Keyserlingk, Maddox, Mahoney, Mickelson, Olson, Raasch, Retallick, Riddell, Treichler, Tucker and White2016). The goal of the FARM Animal Care program is to provide assurance to consumers and customers that dairy farms raise and care for animals in a humane and ethical way.

FARM Animal Care was initiated as a voluntary program to help farmers establish best management practices. Even though the FARM Animal Care program is not mandatory, most dairy processors now require their supplying farms to be certified (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Cook, Darr, DeCoite, Doak, Endres, Humphrey, Keyserlingk, Maddox, Mahoney, Mickelson, Olson, Raasch, Retallick, Riddell, Treichler, Tucker and White2016). Today, 98% of the U.S. domestic milk supply comes from FARM Animal Care program-participating farms (FARM, 2020). All costs associated with evaluations are paid by the coops/processors. Farmers may accumulate indirect costs if there are changes required following an evaluation (Phifer BH, personal communication).

One of the most important aspects of this program is that it is based on continuous improvement; farms do not pass or fail. Producers follow an Animal Care Manual that dictates the required minimum standards as well as the recommended best practices (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Cook, Darr, DeCoite, Doak, Endres, Humphrey, Keyserlingk, Maddox, Mahoney, Mickelson, Olson, Raasch, Retallick, Riddell, Treichler, Tucker and White2016). Every three years, dairy farms participate in an official second-party evaluation. The second-party evaluation assesses the farmers' execution of the guidelines provided in the manual (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Cook, Darr, DeCoite, Doak, Endres, Humphrey, Keyserlingk, Maddox, Mahoney, Mickelson, Olson, Raasch, Retallick, Riddell, Treichler, Tucker and White2016). Evaluations are conducted by personnel trained by certified FARM trainers; evaluators must have a dairy background and take an annual exam to remain certified (FARM, 2020). The FARM program also coordinates third-party verifications, which are conducted by the personnel of an International Organization for Standardization (ISO)-certified third-party verification company. The number of farms selected for third-party verification is determined through statistical sampling and exactly which farms are visited is randomly determined.

Every three years, the Animal Care Manual standards are reviewed and revised by the technical writing group; the most current FARM Manual (Version 4) is in effect for the years 2020–2022. The technical writing group reviews the scientific literature, data from past evaluations and input from a farmer advisory council, then it revises the manual and finally sends it to the National Health and Well-being Committee. From there, it goes to the National Milk Producers Federation Board for a final review before being released to the public.

In the FARM Program Animal Care Version 4.0, failure to meet standards results in particular disciplinary actions depending on the weight of the standard. For example, at the time of evaluation, if a farm does not have a written Veterinarian Client Patient Relationship form annually signed by the farm owner and the veterinarian, that prompts a ‘Mandatory Corrective Action Plan (MCAP)’, where the deficiency must be remedied within nine months. When other standards, such as a benchmark of 99% of all age classes of animals having a body condition score ≥2, go unmet, that precipitates a ‘Continuous Improvement Plan (CIP)’, where the farm has to rectify the issue(s) within three years. Failure to meet the requirements of an MCAP or CIP results in a farm being classified with ‘Conditional Certification’ for 60 d. Failure to comply within the 60 d results in a farm being classified with ‘Conditional Decertification’. Co-ops or processors that are FARM participants may not procure milk from farms that have been decertified. In FARM version 4.0, there is one standard for which a failure results in ‘Immediate Action’: complying with the ban on routine tail docking. Failure to meet this standard results in immediate classification with Conditional Certification. If tail docking continues for more than 48 h beyond the day of evaluation, the farm becomes Conditionally Decertified.

Code of welfare: dairy cattle (New Zealand)

Animal welfare legislation in New Zealand began in 1840 when the country started following the Protection of Animals Act that originated in the United Kingdom in 1835. In 1960, New Zealand passed the Animal Protection Act, which included provisions for the treatment of farm animals. The New Zealand Animal Welfare Act of 1999 (known as ‘The Act’) replaced the Animal Protection Act.

The National Animal Welfare Advisory Committee (NAWAC) created 18 different ‘Codes’ for different animal groups/types, in accordance with The Act (New Zealand, 2010). Under The Act, individuals and organizations could help draft any of the codes of welfare. A combination of public proposals and relevant scientific literature were used to draft the various codes. In New Zealand, owners and managers of animals must comply with both the Animal Welfare Act of 1999 and the current written codes of welfare, which detail the minimum standards of animal management and care that must be followed and provide recommended best practices (New Zealand, 2010).

The ‘Code of Welfare: Dairy Cattle’ (‘The Code’) was originally drafted by an industry group assembled by Dairy Insight (the forerunner of DairyNZ) and submitted to the NAWAC, who reviewed the Code, assured its compliance with the New Zealand Animal Welfare Act of 1999, and submitted it to the Minister of Agriculture for approval (Harding N, personal communication). The Code was ultimately created to help dairy cattle owners and managers understand the requirements they must follow under the New Zealand Animal Welfare Act of 1999 and to protect the reputation of the industry. The Code applies to all dairy cattle: dairy calves until weaning (if headed to beef production), ‘house cows’ (a cow kept to provide for the home kitchen), bulls used for breeding, dairy heifers, and dry and lactating cows (New Zealand, 2019).

All New Zealand dairy farmers are required by law to follow The Code (New Zealand, 2019). In New Zealand, there is no official government-managed auditing program. Instead, dairy processors require farmers to complete annual on-farm audits that focus somewhat heavily on food safety and market access requirements. These annual audits are completed by a third party, who reports the results to the dairy processors. If any animal welfare concerns arise during these audits, inspectors from the Animal Welfare Compliance Division of the Ministry for Primary Industries follow up. Depending on the seriousness of the offence, the response might range from farmer education to prosecution. Because The Code is legally binding, New Zealand primarily focuses on ensuring that their farmers are aware of and understand the requirements of the law. The goal is to encourage compliance with The Code rather than waiting until things have gone wrong and prosecuting farmers. The Code itself provides dairy cattle owners with the information needed to remain compliant under The Act (New Zealand, 2019).

Integrated diagnostic system welfare (IDSW; in development)

The computerized Integrated Diagnostic System Welfare (IDSW) was developed based on an original Integrated Diagnostic System created in 1990 and is described in detail by Calamari and Bertoni (Reference Calamari and Bertoni2009). The IDSW was developed with the aim of assisting farmers in evaluating animal welfare using direct and indirect measurements and in contextually obtaining useful information to improve farm productivity.

The overall IDSW score is a weighted mean of the score for each group of animals that contains the weighted average of three clusters: Environment cluster (information collected about where the animals live, namely housing, equipment and general organization within the housing); Feeding cluster (covering feeding safety, feed quality, feed delivery, daily intake, diet composition and the satisfaction of nutritional requirement for each group of animals) and Animal cluster (which encompasses the evaluation of the behavioral, physiological, performance level and health indices of the animals).

The various indicators were originally developed in the IDSW to successfully fulfill all the requirements for an integrated welfare assessment (Sorensen et al., Reference Sorensen, Sandoe and Halberg2001; Waiblinger et al., Reference Waiblinger, Knierim and Winckler2001) and to better assess the animals' current welfare state. The IDSW model evaluates both factors that affect an animal's welfare (such as management) and factors that provide a direct assessment of an animal's welfare (such as body condition score) (Calamari and Bertoni, Reference Calamari and Bertoni2009). The indirect indicators provide information on risk factors for welfare problems. The direct measures provide information on an animal's response to the environment.

In the IDSW all the indicators, including the qualitative ones, are transformed into a unified score that goes from 0 to 10 (worst to best). The scale is designed to quickly provide an intuitive interpretation of the welfare status of the animals. A specific feature of this program is the identification of welfare scores for each group of animals (such as dry cows, fresh pen, etc.) on the farm. The score for each indicator was developed using scientific literature, when available, and approximation using common sense and practicality when data were not available. At the end of assessment, an overall score is generated, as well as individual scores for each cluster and indicator.

A preliminary evaluation of the IDSW was performed on a commercial dairy farm where it was used to determine the primary causes of poor animal welfare and to direct corrective actions to improve the welfare of the animals (Trevisi et al., Reference Trevisi, Bionaz, Piccioli-Cappelli and Bertoni2006). However, the lack of a stand-alone, user-friendly software and a need for further validation have delayed its implementation by dairy farmers.

Comparisons across welfare evaluation systems for dairy cattle

The dairy welfare evaluation systems described here – WQ, FARM, and The Code – are used to evaluate dairy cattle welfare in different parts of the world. All programs, including the IDSW, were created with the goals of helping farmers keep up with current animal welfare standards and providing assurance to consumers that animals on dairy farms are treated humanely.

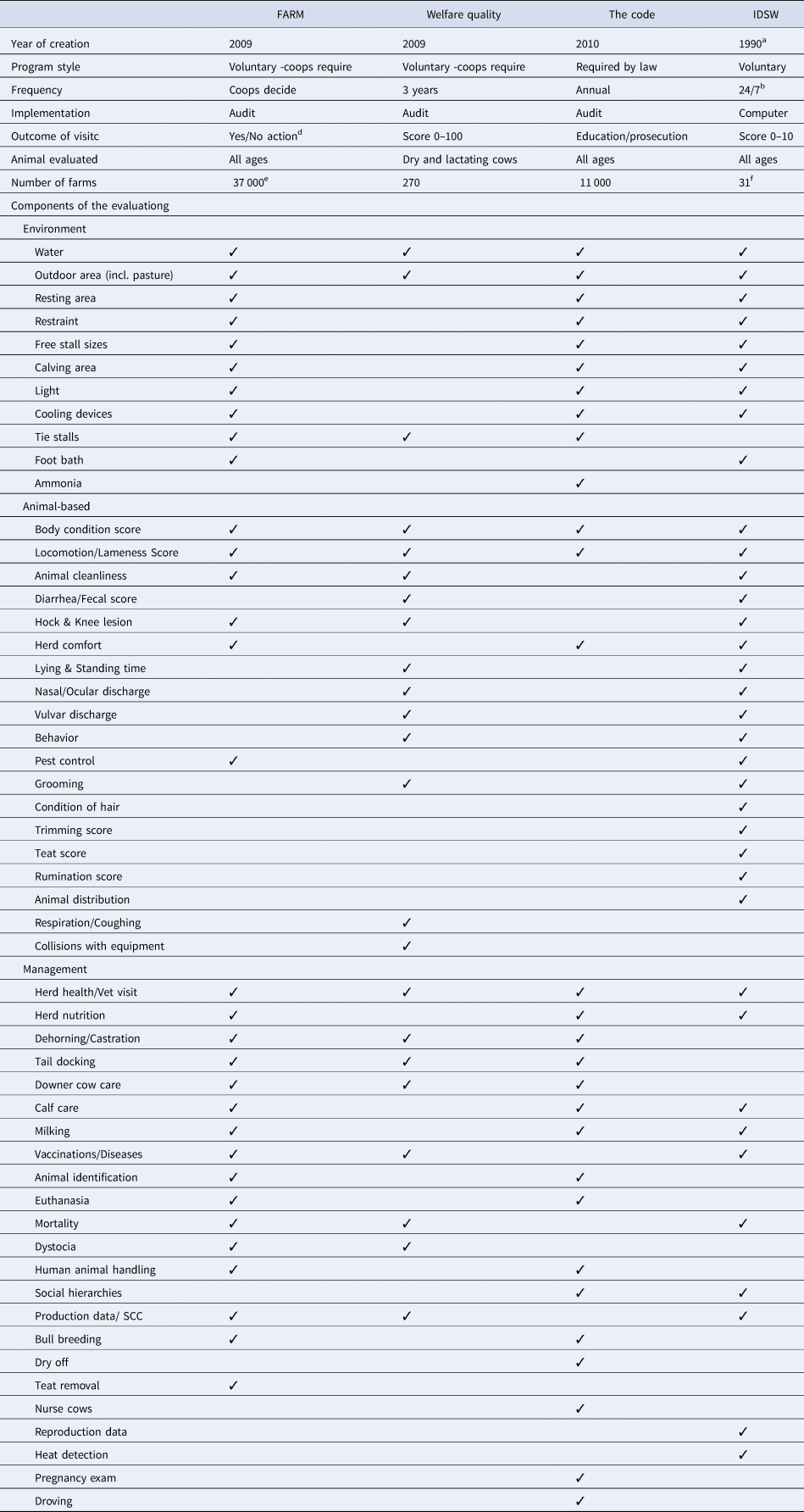

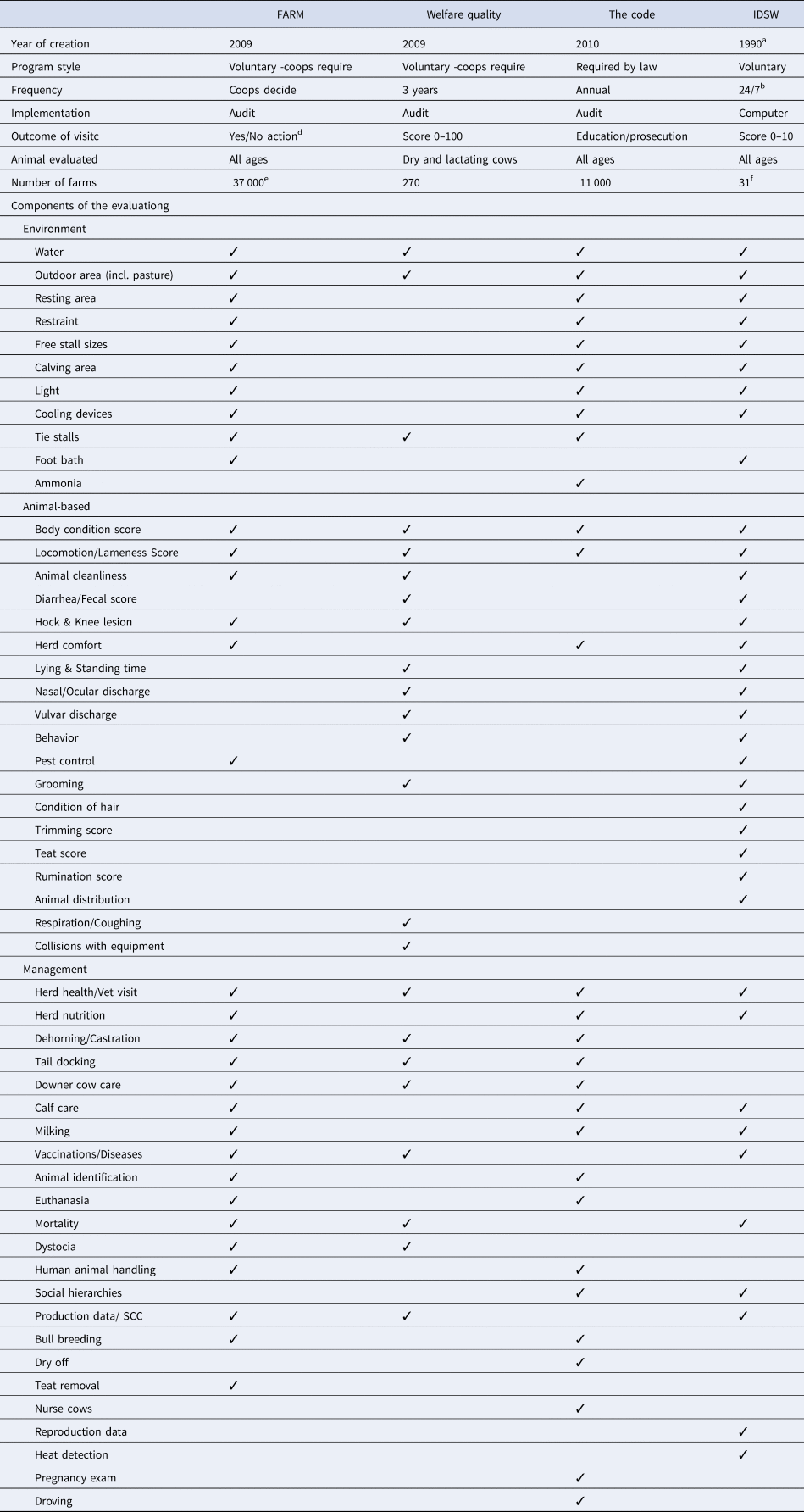

Similarities and differences of the four animal welfare programs examined above are presented in Table 1. Other than the IDSW, which is still under construction, all the programs have similar start dates, suggesting that demand for animal welfare programs increased in the early 2000s. The Code is unlike the other welfare evaluation programs because it is required by law, however, the audits are still managed by farmer co-ops just like in the FARM and WQ programs. In contrast, the IDSW was not designed for auditors, the computer program was created to be used by producers, as a tool to evaluate a farmer's own operation.

Table 1. Summary comparison of the four examined animal welfare evaluation programs

a The year construction started for the IDSW programme, programme is not yet available for public release.

b The goal of the IDSW is to have 24/7 monitoring of animal welfare, currently the program is structured like an audit.

c A visit is when an evaluation or an audit occurs.

d No action/continuous improvement plan/mandatory corrective action plan.

e Number as of May 2019.

f IDSW has been tested on 31 farms in Italy and Oregon (US) (Krueger, Reference Krueger2019; Premi, Reference Premi2019).

g The check symbol denotes the presence of the parameter in the dairy evaluation system.

The most distinct differences across the evaluation programs are among the specific evaluation components. The WQ assessment protocol is largely centered on the animal: of the indicators assessed, 60% are animal-based (de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Bokkers, van Schaik, Engel, Dijkstra and de Boer2016), reflecting the belief of the WQ creators that input-based measurements at the animal level are more reliable than environmental measurements. The assessment in the WQ also includes some resource- and management-based measures. The FARM evaluation differs from the WQ program in this sense. Rather than focusing primarily on the animals to determine welfare status, the FARM evaluation consists of a series of assessments that include evaluation of the physical environment and facilities, farm management, recordkeeping, nutrition, and animal health in addition to some direct animal measures (FARM, 2019). The structure of The Code is more similar to FARM, where most of the same components are evaluated. The Code only has three direct animal measurements and is, therefore, quite different to WQ and the IDSW.

The other major difference among the programs is the output of the audit or evaluation. The WQ program is scored on a 0–100 scale. The FARM program and The Code are geared more toward continuous improvement of animal welfare. Even though The Code is law, New Zealand focuses on helping the farmer before a major problem occurs by providing resources such as workshops and employee training. An evaluation under The Code does not provide a farmer with a score. Likewise, a FARM program evaluation does not generate a final score but rather a status report, and where there are deficiencies, an improvement plan is developed to address them. The IDSW program produces an overall farm score, on a 0–10 scale. Within that score, a farmer can look at group and individual indicator scores to determine specifically where in the operation there might be room for improvement.

Of the four programs, WQ is the only one that evaluates just adult dairy cattle; young heifers and calves are excluded (Larsson, Reference Larsson2014). This is one of the biggest flaws in this program as managing young livestock is at least as important as managing adult animals. In addition, the WQ program is largely structured on animal-based evaluations, while the other programs – The Code, FARM and IDSW – account for other factors, such as an animal's environment. An unfit environment might lead to animal welfare problems. For an animal welfare assessment to be truly comprehensive, the program should include evaluations for every stage of an animal's life and evaluate aspects including environment, management, and direct animal measurements. Aspects of an animal's environment are integral to its welfare. Areas where cattle live need to be clean, comfortable, safe, and allow cows to perform their daily routines with minimal stress. This means welfare programs also need to assess the farmer's ability to manage the animal's environment and provide an environment that fits the type of cow on the facility. To be truly comprehensive, welfare programs need to be able to evaluate the types of environments a cow might live in, from a tie stall to a pasture to a pack barn and be able to evaluate the different types of equipment that might be found in those environments.

Animal welfare is the combination of multiple characteristics (Fraser, Reference Fraser1995). It is sensible to consider animal measurements as a way to directly assess an animal's actual welfare state (Capdeville and Veissier, Reference Capdeville and Veissier2001; Whay et al., Reference Whay, Main, Green and Webster2003), which provides a snapshot of the cow's health at the time of appraisal. Body condition scoring (BCS) and locomotion/lameness scoring are the two animal measures that are similar in all four programs. FARM, WQ, and IDSW include evaluations for animal cleanliness, feces, hock and knee lesion scoring, and herd comfort. Herd comfort evaluates the standing and lying behavior of cows in stalls (assessed in IDSW) and requires that cows are provided with a suitable place to lie and rest that is not concrete (assessed in FARM and The Code). However, WQ and IDWS have the most complete animal evaluations. Six animal-based parameters are only found in WQ and IDSW: lying time/behavior and standing time, nasal/ocular discharge, vulvar discharge, animal behavior tests/stereotype behaviors, and grooming.

Among assessments related to animal management, the only evaluation that is included in all four programs is herd health/veterinary visit. Nutrition plays a vital role in determining the overall well-being of an animal; FARM, The Code, and IDSW all evaluate nutrition. WQ, the only program without a nutrition component, would benefit from adding this evaluation. Disbudding, dehorning, castration, and tail docking are all practices that threaten animal welfare if performed incorrectly. Evaluations of these practices are found in FARM, WQ, and The Code. On-farm milking practices are assessed in FARM, The Code, and IDSW. Eight evaluations, including animal identification, euthanasia, mortality, dystocia, animal handling/moving, social hierarchies, production data/SCC, and bull breeding are found in only two of the four welfare evaluation programs (Table 1).

Evaluating the aspects of animal management on a dairy can be a helpful way to assess the overall health of a herd. Improving the procedures of animal-related tasks on a farm (castration, human–animal interaction, etc.) will help to ensure that animal productivity is maintained and that animals do not experience unnecessary pain and distress. Like direct animal measures, it is important that the evaluation of animal management covers managerial decisions made for all ages and all sexes of animals on a farm.

Concluding remarks

The complexity of the welfare assessment in dairy animals has led to the development of several evaluation systems with their own strength and weaknesses. Our overview of three relevant animal welfare programs and IDSW has led us to the conclusion that it is important to consider certain aspects of the environment in which animals live, direct animal measurements and animal management decisions. Animal welfare programs should include evaluations for animals of all ages. All programs should help to identify ways to minimize pain and distress and to assess farmers' ability to provide a safe, clean environment. It seems that IDSW covers the majority of potential evaluations, giving it a possible advantage over the other programs. FARM and The Code include a complete assessment of the environment and animal management related measures. However, they are lacking many direct animal measurements, while most measurements within WQ are directly from the animal. WQ might benefit from increasing the range of environmental measurements to help determine what environmental aspects affect welfare outcomes seen in cows.

The availability of systems to evaluate welfare of dairy cows is important to ensure the general public of a high standard of well-being of the animals. It seems useful to set a minimal threshold of acceptable welfare condition under which the farm is required to intervene urgently to address the issues. Systems to evaluate welfare for dairy cows are also good for producers considering that the wellbeing of the animals directly affects performance. Thus, assessment of animal welfare is also a good tool for the producers, revealing critical points of their management that need improvement and can be used to prioritize future investments.

Several limitations of the various dairy welfare evaluation systems need to be improved. None of the available welfare programs have been fully validated with independent measurements (e.g. blood indexes) to ascertain if they accurately capture and measure animal well-being. For the sake of practicality, and because of the independent scientific validation, the number of indicators could be revised and reduced by focusing on the indicators that best represent the level of welfare. Except for the IDSW, the lack of a standalone software for most of the welfare evaluation systems is an important limitation. Lack of such a feature can limit future application, including the inability for dairy producers to self-evaluate. Furthermore, as of now, none of the welfare assessment systems integrate with automated data gathering systems that are in development and are already in use on many farms. This deficiency limits the potential ability of welfare evaluations to become more precise and more automated and to implement some degree of direct on-farm validation. As the trend moves increasingly toward ‘smart’ dairy farms, welfare assessment programs should do likewise.

Acknowledgments

This article is based upon work from COST Action FA1308 DairyCare, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology, http://www.cost.eu). COST is a funding agency for research and innovation networks. COST Actions help connect research initiatives across Europe and enable scientists to grow their ideas by sharing them with their peers. This boosts their research, career and innovation.