Introduction

Fluid resuscitation (FR) has been a mainstay in the management of sepsis and associated systemic inflammatory response syndrome for more than a decade [Reference Rivers1]. Several investigations have challenged this prevailing practice, stressing on a more conservative strategy [Reference Wiedemann2–Reference Marik4]. Further, in the Fluid Expansion as Supportive Therapy trial, FR was associated with increased mortality of African children with sepsis. The objective of our study was to observe the effect of fluid administration on survival, and to study the correlation of inflammatory cytokine levels with survival after sepsis induction in a murine model of polymicrobial sepsis.

Materials and Methods

Female C57BL/6 mice (aged 6–12 weeks, weight 20–25 g at the time of delivery, n=21) (Jackson Laboratories), were allowed to acclimatize for 1 week with free access to food and water and 12-hour light-dark cycles (NYU-IACUC no. 120705).

Baseline blood samples were drawn 2 weeks before induction of sepsis using cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) [Reference Nolan5]. Mice were then randomly assigned (n=7 in each) to the following groups: no resuscitation (NR), 30 cc/kg FR (FR30), and 100 cc/kg FR (FR100). At 1 hour after CLP, a second blood sample was drawn. Mice were resuscitated using a subcutaneous (abdomen) normal saline (0.9% NaCl) bolus based on weight. Mice were observed and blood samples were drawn using facial venous puncture hourly until death. Total blood volume (140–180 µL) sampled on the day of CLP did not exceed 10% of the calculated blood volume and samples were pooled into 3 groups.

Serum sample aliquots for each group at each time point were stored at −80°C (n=3) and analyzed for IL-6 (Luminex-200IS, Invitrogen). Data were analyzed using MasterPlexQT (Miraibio). Serum cytokine values were indexed to serum albumin concentrations (GenWay) to correct for the diluting effect of FR.

SPSS-23(IBM) and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad) were used for database management and analysis. Mortality was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival and log-rank testing for significance. IL-6 was analyzed using a 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) allowing for a repeated-measures analysis over time.

Results

Survival

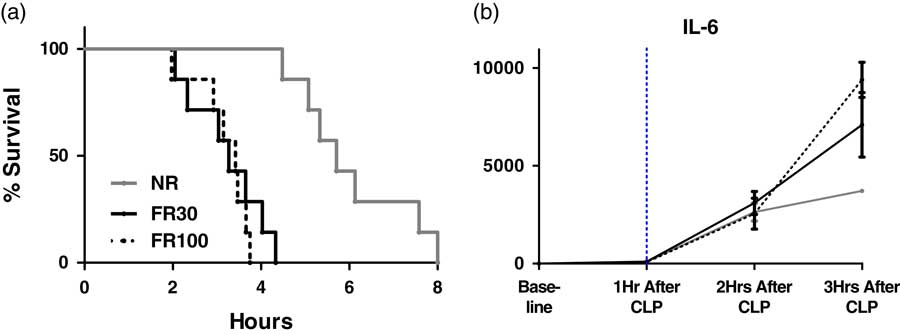

The NR group had a significantly longer mean survival time (6 h:51 min) than either the FR30 or the FR100 group (mean 3 h:31 min, and 3 h:2 min, respectively). The survival curve for the NR group was significantly different from the survival curves of the FR30 and FR100 groups, which were obtained using the log-rank Mantel-Cox test (p<0.001). All FR30 and FR100 mice had died before any of the NR mice died, because of induced sepsis. Further, there was no difference in the survival curves between the FR30 and FR100 groups. We were also able to determine min-max survival times, as shown in Fig. 1a .

Fig. 1 (a) Survival analysis of fluid resuscitation (FR) strategies (Kaplan-Meier analysis). (b) IL-6 levels in murine model of polymicrobial sepsis over time, n=21. Baseline levels of analyte are recorded at 0 hours before cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), and then hourly post-CLP. Time of fluid resuscitation is indicated by …... IL-6 levels were found to be significantly different between non-resuscitated mice and fluid-resuscitated mice (FR30, FR100) using 2-way ANOVA analysis. Analyte levels are expressed as means with error bars representing SEM. NR, no resuscitation; FR30, fluid resuscitation 30 cc/kg; FR100, fluid resuscitation 100 cc/kg.

IL-6 Elaboration After FR

Baseline and 1-hour post-CLP levels of IL-6 were quantifiable and not significantly different in any of the treatment arms, as shown in Fig. 1b . The level of IL-6 was significantly higher as time passed (p<0.001). The IL-6 level was significantly higher in the FR30 and FR100 groups compared with that in the NR group 3 hours after fluid resuscitation, as shown in Fig. 1b .

Discussion

We found that fluid resuscitation, compared with no resuscitation, resulted in increased mortality and significantly higher IL-6 levels in a murine model of sepsis. Our findings align with those from the Fluid Expansion as Supportive Therapy trial. The post hoc analysis of the latter showed that cardiovascular collapse was a cause of excess death with rapid FR rather than with fluid overload [Reference Maitland6, Reference Myburgh and Finfer7]. A possible explanation was that rapid restoration of circulatory volume via FR may have unintended consequences, including the interruption of the compensatory, sympathetic, and innate response to hypovolemia. In this scenario, fluid given early in sepsis results in the rapid conversion from vasoconstriction to vasodilation by disseminating a localized and contained focus of cytokines from infected tissue to the systemic circulation.

Our study shows rapid decompensation in septic FR mice compared with NR mice. We found no difference in mortality between low- and high-volume resuscitated groups. It appears that even small volumes of crystalloid boluses may be sufficient to trigger earlier mortality in this animal model. Further, although cytokine levels increased in all mice as time progressed, FR mice demonstrated significantly higher levels of IL-6.

Study limitations include our lack of actual measured blood pressure or heart rate data. Instead, we used mortality—a commonly used endpoint in human trials—as a surrogate for vascular compromise. Antibiotics were intentionally not used to avoid a possible Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction that may increase inflammatory cytokine expression. Vasopressors, ventilator support, and other adjunct support were not provided as treatments for sepsis in our model, allowing the study of FR in isolation.

In summary, we observed elevated inflammatory cytokine expression soon after fluid resuscitation in our murine sepsis model. Increased cytokine expression correlated with rapid decompensation and significantly increased mortality in fluid-resuscitated mice. This observation is not only clinically relevant but may also be the focus of future mechanistic studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their contributors and colleagues for their support.

Financial Support

R01HL119326; NHLBI K23HL084191/S1, Saperstein Scholar Award and a Clinical and Translational Science Institute Pilot Project supported in part by grant UL1TR000038 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The funding agencies did not participate in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author’s Contribution

Y.I.L., R.L.S., and A.N. participated in study conception and design; Y.I.L., R.L.S., and A.N. were the primary investigators; and responsible for data collection and data validation; Y.I.L., S.K., and A.N. participated in data analysis and undertook the statistical analysis. All authors participated in data interpretation, writing and revision of the report, and in approval of the final version. No individuals contributing to data collection, analysis, writing or editing assistance, and review of manuscript have been omitted. A.N. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, including and, especially, for any adverse effects.