Introduction

Since 2006, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has supported the Clinical and Translational Sciences Awards (CTSA) program, now housed within the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). These centers are designed to improve the health of individuals and the public by developing innovative approaches to translating basic science findings in the laboratory to clinical and community settings [1, 2]. Since inception, the CTSA programs have placed a priority on community engagement throughout the translational science continuum [3]. The focus on community engagement was in response to several factors including increasing health disparities [Reference Krieger4, Reference Singh and Siahpush5], the length of time required to translate research into practice [Reference Morris, Wooding and Grant6], failures in recruiting for clinical trials [Reference Krall7], and the difficulties in moving from efficacy to effectiveness research [Reference Krall7].

Community engagement can be understood as a strategic process aimed at establishing “collaboration between institutions of higher education and their larger communities (local, regional/state, national, global) for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity” [8]. At its core, community engagement seeks to achieve equitable, meaningful, active community participation in all phases of the research process [9] and highlights community strengths to accelerate improvements in health. Benefits of a community-engaged approach to research include greater participation rates, increased external validity, decreased loss to follow-up and the development of individual and community capacity [Reference Leung, Yen and Minkler10, Reference Bodison11]. Community engagement can also foster trust between high-risk communities and academic partners, particularly when there is a history of distrust [Reference Minkler12, Reference Wallerstein and Duran13]. Further, a recent systematic review found that community engagement can lead to improved health and health behaviors among disadvantaged populations if designed properly and implemented through effective community consultation and participation [Reference O’Mara-Eves14].

The establishment of Community Advisory Boards (CABS) is a proven strategy for increasing community engagement in research [Reference Newman15, Reference Gonzalez-Guarda16]. A CAB is usually a specialized entity assembled in a particular community for a particular research project; CABs tend to have homogeneous membership deriving from the topic of the search study [Reference Gonzalez-Guarda16–Reference Frye18]. Community Engagement Advisory Boards (CEAB) differ from a CAB in that they advise on more substantive aspects of research including research questions, methodology, interpretation of results, and dissemination [Reference Cramer19]. CEABs may also differ in the diversity of types of expertise on the board (lay community members, leaders of community organizations, research staff, and researchers) and in the expressed purpose of capacity building for academic and community partners who engage in community-based research and translational science [Reference Pinto, Da Silva, Penido and Spector20].

The goal of this paper is to describe the formation, operation, and evaluation of a CEAB that serves as a component of the recruitment and retention program of the NIH funded Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences (CCTS) at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). In 2009, the CCTS established a CEAB as a working group within the Recruitment, Retention and Community Engagement Program (RRCEP). The specific aims of the RRCEP are to build the capacity of academic and community partners to engage in community-based research and translational science, to increase engagement and overcome barriers in recruiting special populations, and to increase investigators’ skills in effective and culturally sensitive communication about research opportunities, study objectives, and informed consent. As a core component of the RRCEP, the CEAB was developed to support and advise researchers at UIC who engage in community-based research and translational science. Based on formal evaluation data and informal feedback from all stakeholders—community partners, academic researchers, and CCTS leadership, this program has been a success. Our approaches can guide the development of similar community engagement activities at other CTSA programs.

Overview of the CEAB and Its Relationship to CCTS Activities

The CEAB is a free consultative service provided to university faculty, postdoctoral fellows, and doctoral students from UIC, university faculty from other area academic institutions, and researchers from community agencies. As part of the RRCEP, the CEAB board is overseen by 2 faculty co-directors and a staff member. The CEAB board members are invited community and patient advocates, members of key community-based organizations, and research faculty and staff members from UIC and other academic institutions. In order to maximize efficiency, reduce burden on members, and ensure good attendance at meetings, there are 2 boards. These meet on alternating months on different days of the week. Each board has ~15 members who serve 3-year terms (currently there are a total of 31 members). A CEAB meeting is held each month (with the exception of summer and December) to ensure that the community remains engaged in the development and direction of community-engaged research at UIC. Board members attend an average of 3–4 meetings per year. The role of the CEAB is to provide useful and constructive suggestions to consultation recipients on any number of research issues and/or questions in which the consultation recipient seeks input. CEAB consultations focus on research methods, recruitment and retention plans, recommending culturally appropriate engagement strategies and identifying and overcoming barriers to participant engagement.

Board Formation and Composition

The CEAB consists of executive directors and direct service providers of respected community-based organizations, patient advocates, community advocates, faculty, and experienced research staff. The initial core group of CEAB members was selected based on connections to specific community organizations, a desire for representational diversity in terms of race/ethnicity and gender, and familiarity with key priority populations. A deliberately chosen mix of academic and community representation ensures that each consultation can be evaluated in terms of scientific merit, community relevance, and importance to patients. The current composition of the CEAB membership is 64% community based and 36% academic researchers (n=31). Based on self-reported data, the expertise of the membership is vast with a range from chronic illness (31%), health (27%), community engagement (16%), healthcare access (16%), and community development (10%). In total, 45% of participating community-based organizations serve the entire city of Chicago and another 55% reported serving a specific Chicago neighborhood (i.e., Pilsen, Englewood, Woodlawn). The populations served by members and their organizations include African American (25%), Latino (19%), low income (19%), or diverse communities (37%). Each member serves a 3-year term. Members with consistent participation are invited to continue for another term. Annually, an assessment is made as to whether new members are needed due to attrition or members completing their terms. New members are identified based on the recommendations of existing members, sought out to address specific gaps in representation or expertise on the board, or based on new community linkages with any of the existing CTSA team members. Letters of invitation are sent to prospective members outlining the objective of the CEAB, roles and responsibilities of members, and time commitments.

Board Rapport Building and Development

Ongoing communication and rapport building with the CEAB members is essential to the success of the consultation program. Communication via email and phone occurs on a regular basis, including save-the-dates, meeting reminders, meeting preparation materials, and thankyou cards. To ensure meaningful involvement and collaboration, we provide systematic training of all members. Training emphasizes CEAB member responsibilities, which include coming prepared to the meetings and arriving on time, actively participating in the consultation discussion, asking questions, and maintaining confidentiality regarding the research study and design. The training also includes a lay orientation to the research process, research terminology, types of research approaches, and the principles of community-engaged research. Although CEAB members are not required to complete human subjects’ protection, it is recommended that they do CITI (https://about.citiprogram.org/en/series/human-subjects-research-hsr/) or another similar training program to increase understanding of the ethical considerations associated with research. In addition, we orient members to the format and expectations of the consultation. In addition to the initial on-boarding training, we also provide ongoing continuing education through “learning sessions” that address member’s educational needs and requests. For example, learning sessions have been offered on ethical issues in the conduct of community-engaged research and emerging issues in the conduct of genetic research. Plans for future educational programming include increased exposure to issues associated with special populations including LGBT populations, urban youth, and persons with disabilities.

Board Development

CEAB members’ expertise on health and social issues facing ethnic minority, low-income, and LGBT populations is nurtured through the professional board development activities provided to the membership by CCTS leadership and staff. In focus groups conducted in 2014, CEAB members provided feedback regarding the needs of new members; efforts have been made since to address these concerns. Based on input from CEAB members, new practices have been developed over time to assist members in performing their roles and responsibilities. First, to ensure meaningful involvement and collaboration between partner members, members are now provided with introductory training sessions. The training includes a lay orientation to the research process, research terminology, types of research approaches, and the principles of community-engaged research. To increase understanding of the ethical considerations associated with research, all members are recommended to complete CITI or other ethical research training programs such as UIC’s CIRTification Program [Reference Anderson21]. In addition, we orient members to the format and expectations of the actual consultation meeting and provide new organizational items such as consultation binders, action pages, and consultation abstracts.

The Operation of the CEAB Consultation Service

Outreach to Campus Researchers

A range of activities are used to advertise the CEAB consultation service. First, the CTSA has a dedicated webpage that describes all of the available resources for campus researchers. Interested researchers are able to directly request a consultation via an interactive webpage. Staff for RRCEP program receive the consultation request and directly contact the researcher and set up the consultation. Staff also send out direct advertisements for the service using college and faculty listservs. Promotional materials are also included at all relevant CTSA activities. Finally, referrals are made from other researchers who have previously used the service or from directors of other CTSA staff who are working with a researcher on another topic and the need for recruitment or community engagement is identified.

Preparation of Investigators for CEAB Meetings

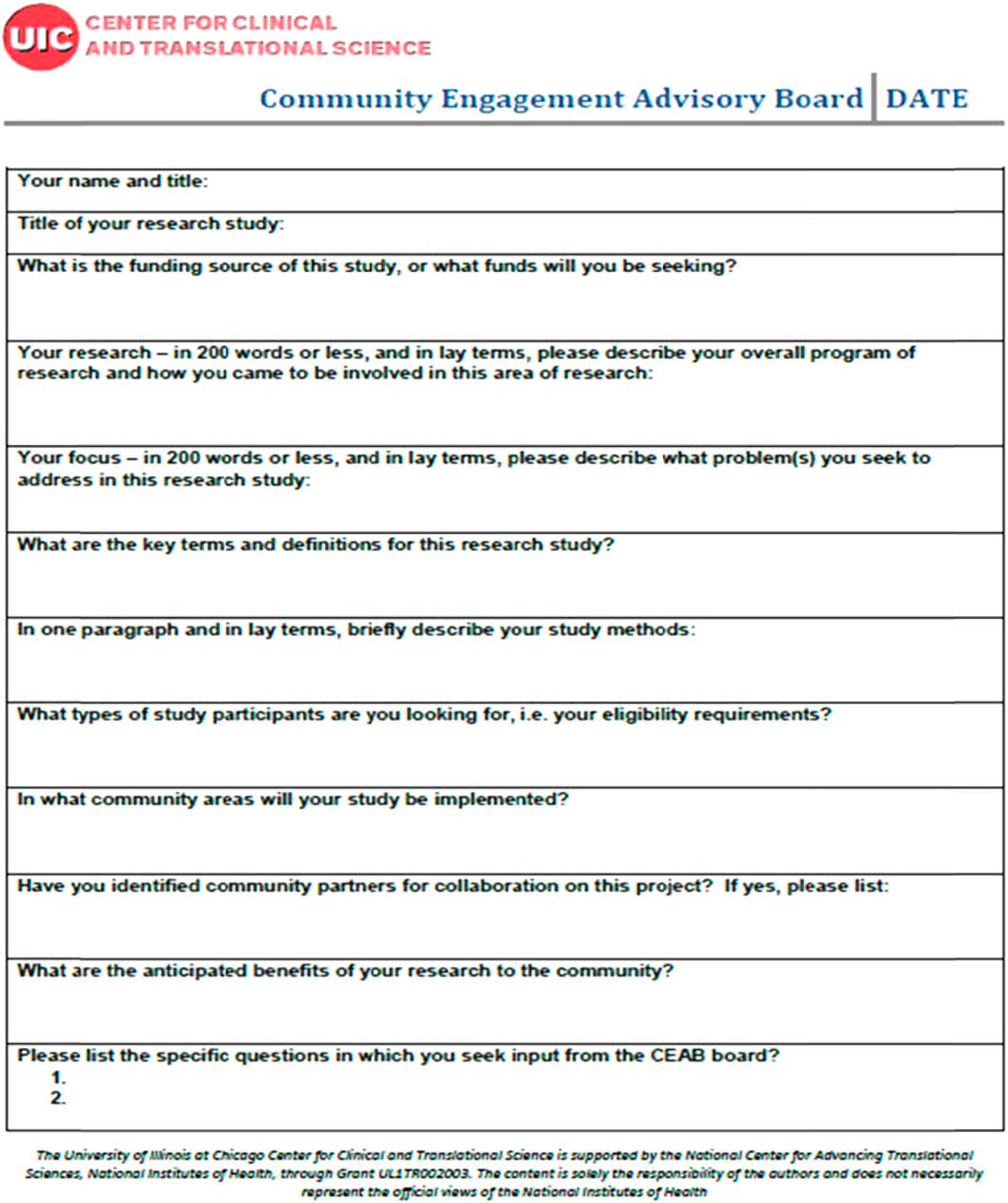

In order for a researcher to benefit from a consultation with the CEAB, they must adequately prepare meaningful interaction. CEAB staff work very hard with investigators to increase consultation readiness. Following a request for a CEAB consultation, the investigator first completes a template for an abstract that concisely and in lay terms describes their study goals and the specific focus of the CEAB consultation (see Fig. 1). This abstract serves as a valuable tool for the CEAB members to learn about the research and to prepare for the meeting. Consultation recipients are also required to complete and submit a standardized PowerPoint presentation at least 1 week before their consultation. Consultation recipients are advised to keep their presentation brief and concise to maximize time for questions and discussion. The template for the presentation includes the title, research focus, specific aims of the study, methods used, potential benefits to the community and specific consultations questions. The researcher is advised to show less than 10 slides, and to only focus on what is pertinent for the CEAB members to know so that the CEAB members can give input on what is specifically asked of them. Investigators are coached if their abstract and/or PowerPoint are not sufficiently concise, clear, and targeted to a lay audience.

Fig. 1 Community Engagement Advisory Board (CEAB) consultation abstract.

Pre-Consultation Preparation for CEAB members

Email or phone communication 1–2 weeks before each CEAB meeting, as well as immediately after the CEAB meeting, helps to build rapport and maintain active engagement. Before each regularly scheduled consultation meeting, the CEAB members are emailed the meeting agenda, an abstract summarizing the research problem and reason for the consultation, and any additional supporting materials provided by the investigators. While the hope is that sending materials in advance will facilitate pre-meeting preparation, printed copies of all materials are also made available for members at each CEAB meeting.

Format and Management of Consultation Meetings

CEAB consultation meetings last about 2 hours and typically include 2–3 consultations of 30–45 minutes each. At each meeting, breakfast is provided, parking is complimentary, and $50 gift cards are provided for services rendered. Before the first consultation, CEAB members have refreshments, check in with other CEAB members, and are oriented to the meeting agenda and upcoming consultation sessions. For each consultation, the researcher gives a brief presentation using slides to provide an overview of the study goals and objectives and to highlight the 2 or 3 key questions for the consultation. Members ask clarifying questions, engage in discussion regarding the consultation issues, and offer recommendations to the researcher.

Number and Types of CEAB Consultations Provided

Since the CEAB started in October 2009, 123 consultations have been provided through January 2017 to UIC investigators from 17 different departments, institutes or colleges as well as investigators from 2 other universities. Over the past 5 years, consultations provided for researchers have fallen into one of the following categories: (1) reviewing recruitment materials and providing advice on recruitment and retention of a wide variety of patient populations (14%); (2) recommending modifications to measurement tools to make them culturally appropriate for specific ethnic groups (13%); (3) reviewing research protocols to provide advice on components involving recruitment and community partnerships (55%); (4) recommending appropriate means of disseminating research results (13%); and (5) advising on the development of Community Advisory Boards (5%). Of these consultations, the vast majority supported an investigator who was either working on a current NIH-funded project or in the process of preparing for a future grant submission to NIH.

Post Consultation Procedures

CEAB staff members take detailed notes, including key recommendations and contact information (pertinent Web sites, email addresses, and phone numbers) from all consultations. Soon after the meeting, notes are sent to the consultation recipients and CEAB members, along with expressions of gratitude to both parties for their participation. At 2 weeks post consultation, staff members contact the researchers to ask if they need an individual follow-up consultation to further discuss their study or if they require additional assistance in reviewing the recommendations of the CEAB members and developing a specific plan of action. Investigators are also invited back to the CEAB for further consultation, to provide an update on their research (this is strongly encouraged) and/or to seek input from the board members on a new research project. CEAB consultees are also asked to complete a web-based satisfaction questionnaire immediately their consultation.

CEAB Evaluation Processes

Reporting of CEAB activities is needed so that the leadership of the Recruitment, Retention and Community Engagement Program (RRCEP) of UIC’s CTSA can evaluate the effectiveness of the CEABs in achieving program goals and objectives. A satisfaction questionnaire was developed in collaboration with the Evaluation and Tracking (E&T) team to survey investigators receiving a CEAB consultation. Online surveys are sent via email to investigators immediately after the CEAB meeting and at 1-year follow-up to obtain feedback regarding the satisfaction and effectiveness of the consultation services received. These de-identified data derived from online surveys were initially collected for quality assurance purposes and were determined to be exempted by the IRB of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The questionnaire has been sent to 117 consultees and return surveys were received from a total of n=91 investigators (response rate 78%). Table 1 shows survey results across the lifetime of the CEAB consultation service. Overall, CEAB members were viewed as having sufficient information (92%) and expertise (79%) to review and provide input on the investigator’s research project. The majority of respondents felt that the consultations were either very (38%) or extremely helpful (41%), that they would likely implement the recommendations received (88%), and that the consultation would likely improve their future research project (88%). Satisfaction levels with the specific consultation received and the overall consultation service were high. The majority of investigators indicated that they would come back to the CEAB for a future consultation, if needed, and would recommend a consultation to others (93% and 96%, respectively). One-year follow-up data are available for consultation recipients for years 2009–2015 (n=45). At the 12-month follow-up interview, 60% of consultees indicated that the suggestions of the CEAB members had been very (36%) or extremely helpful (24%). Another 29% indicated that the consultation was moderately helpful. At 12-months, 87% of the consultation recipients stated that they had implemented at least some of the recommendations received and 93% said that the consultation influenced their thinking as they planned for future research. The success of the program is also borne out by the fact that more than 15% of the researchers have presented more than once at a CEAB meeting.

Table 1 Community Engagement Advisory Board initial consultee evaluation (2009–2017, n=91)

CEAB, Community Engagement Advisory Board.

Numbers vary due to missing data.

Implications and Conclusions

Community engagement is essential to the successful translation of interventions and other healthcare advances implemented in community settings. Although beneficial, there is recognition that community engagement processes can be time consuming and challenging. It is also recognized that reaching out to and engaging communities may require skill sets for which investigators may have various levels of experience and expertise. Consequently, an important role of the CTSA programs is to establish resources and best practices for facilitating community engagement and increasing the success of research initiatives. The CEAB at UIC’s CCTS provides a model for providing community engagement and consultation to assist investigators with their translational science goals. Unlike a community engagement board, the CEAB is comprised of a mix of community advocates, members of key community-based organizations, and experienced clinical and behavioral researchers. This mix of academic and community expertise enables each consultation to be examined and explored by a diverse group of devoted lay people and professionals. Trained to give targeted, “economical” feedback to consultation recipients, CEAB members provide useful and constructive suggestions during consultations on any number of research issues and/or questions in which the consultation recipient seeks input from the board members. Another strength of this approach is that feedback is provided to recipients from the perspectives of community members and researchers with experience in community engagement.

Next Steps

An important component of maintaining a strong CEAB program is training and capacity building. The future goals of the CEAB program are to include additional organizations to address special populations and to build capacity via additional training. We will formally work with individual CEAB members to facilitate educational and recruitment activities in their home communities or organizations to better educate community members about available research projects initiated at UIC and for NIH multisite studies, thus using the current CEAB members for outreach activities. We also plan to systematically track the linkages that form between CEAB board members and UIC investigators following the consultations, that is, the ripple effect of the CEAB program in building capacity for both UIC investigator and CEAB board member.

Conclusions

Since inception, the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Award programs have placed a priority on community engagement. The establishment of innovative and effective approaches to support capacity building for academic and community partners is essential to the realization of the benefits of community involvement. The consultation service developed by the UIC CTSA has demonstrated the benefits of CEAB consultations for researchers. Our model can be used to inform the development of future CEAB boards at other CCTS locations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Drs Carol Ferrans, Karriem Watson, and JoEllen Wilbur in the initial creation of the CEAB working group.

Financial Support

The University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS) is supported by the NCATS, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR002003 (Tobacman & Mermelstein, 2016). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the office views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.