Introduction

There is widespread recognition of the persistent health disparities and inequities in our society, and it is well-documented that these disparities negatively impact racially and ethnically marginalized populations. The All of Us Research Program aims to help address this by enrolling 1 million or more participants from diverse backgrounds to gather data on genetic, environmental, social, and behavioral factors to better understand how these factors impact health outcomes [Reference Denny and Rutter1]. These data will be broadly shared with qualified researchers to accelerate medical breakthroughs. Without meaningful involvement from diverse communities of which All of Us is recruiting, the project would face significant challenges to sustain 80% representation of groups historically underrepresented in biomedical research (UBR).

Individuals from UBR groups have long experienced substandard health outcomes as a result of health care and research enterprises inadequately serving diverse patient populations [Reference Getz, Florez and Botto2,Reference AlShebli, Rahwan and Woon3]. One of the primary strategies of forging new relationships, establishing trust, bestowing respect, and increasing participation in biomedical research in diverse communities is through community-based participatory research (CBPR) [Reference Viswanathan, Ammerman and Eng4]. This framework places community at the center of the research planning and execution process and includes a formal mechanism to communicate with key community members to get their input, feedback, and opinions about how the research will be carried out [Reference Fisher and Ball5,6]. Benefits from the CBPR model include increased trust between communities and academic institutions, reduction of communication and collaboration barriers, incorporation of novel research methodologies, community empowerment, increased diversity, and greater likelihood of participant retention [Reference Eder, Carter-Edwards, Hurd, Rumala and Wallerstein7].

One of the motivations behind CBPR stems from overall low participation across all demographics in clinical research [Reference Davis, Clark, Butchart, Singer, Shanley and Gipson8]. For example, less than 10% of cancer patients participate in clinical trials [Reference Unger, Vaidya, Hershman, Minasian and Fleury9] and nearly 1 in 5 clinical trials fail to achieve accrual goals [Reference Carlisle, Kimmelman, Ramsay and MacKinnon10]. Additionally, there is a persistent lack of diversity in clinical research due to a variety of barriers that have been well-described in the literature [Reference Haley, Southwick, Parikh, Rivera, Farrar-Edwards and Boden-Albala11,Reference Clark, Watkins and Piña12]. There are valid reasons why people choose not to participate, including lack of awareness of study opportunities, burden of participation, financial barriers, and fear of study-related risks [Reference Mills, Seely and Rachlis13,Reference Nipp, Hong and Paskett14]. To overcome these challenges, CBPR connects community members with researchers to integrate community-identified needs and perspectives into a more inclusive, participant-centric study design. Since its introduction, CBPR has been adopted by the National Institutes of Health, professional medical societies, and academic medical centers to promote community involvement and population diversity in clinical research [Reference Harris, Pensa, Redlich, Pisani and Rosenthal15–Reference Julian McFarlane, Occa, Peng, Awonuga and Morgan17].

The formation of a community advisory board (CAB) is a proven CBPR-based approach investigators use to engage key members of the community to take part in the research design process [Reference Newman, Andrews, Magwood, Jenkins, Cox and Williamson18–Reference Anderson and Getz22]. CABs are not always designed to include individuals who come from different socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, educational, and cultural backgrounds which limits their utility to help investigators develop a more nuanced perspective of their target study population, including perceptions and barriers for participation in research. Since CABs often lack diversity [Reference Gilfoyle, Melro, Koskinas and Salsberg23–Reference Montalbano, Chadwick and Miller26], they can result in limited perspectives, bias in decision-making, perpetuation of health disparities, and reduced trust and engagement in medical institutions. Similar to the makeup of corporate boardrooms, increasing diversity on CABs can improve psychological safety and quality of feedback by reducing feelings of tokenism and increasing feelings of inclusion [Reference Lawal and Nuhu27,Reference Rixom, Jackson and Rixom28]. This can be measured by including multiple members of diverse communities and asking CAB members to complete a feedback form after each meeting to assess their satisfaction with meetings and their contributions.

A core tenet of All of Us is to treat participants as partners, therefore, each program awardee is required to establish a CAB with members representative of the diverse All of Us cohort[Reference Denny and Rutter1]. As an All of Us awardee, the Scripps Research Translational Institute (SRTI) formed a representative CAB that is formally called the Virtual Advisory Team (VAT). With the engagement and guidance of the VAT, the SRTI team has recruited 20% of the total All of Us cohort – roughly 175,000 participants to date, 78% of whom have been historically underrepresented in biomedical research.

In this paper, we describe our rationale and approach to forming the All of Us VAT, how we achieved diversity, and how we continue to engage underrepresented communities to join one of the largest, most diverse health research programs in the US.

Community engagement in health research

Recognizing and respecting the diverse cultural backgrounds of community members is vital for fostering effective collaboration [Reference Randal, Qi and Lozano29]. The process of involving diverse members of the community in identifying common problems, mobilizing resources, and developing and implementing strategies for reaching collective goals has been adapted by social change professionals for decades [Reference Minkler30].

Community engagement began to be emphasized in health research in the 1980s during the height of the AIDS epidemic [31] which aimed to broaden access to clinical trials for HIV-infected individuals in underrepresented communities based on being part of a minority group, those who lived far from an established clinical trial site, those who were sexual partners of HIV-infected individuals or IV drug users. Awardees were required to demonstrate community support for this effort. However, even with these requirements, many communities including women, transgender individuals, and those living in Sub-Saharan African nations have been excluded from a majority of HIV research [Reference Dubé, Kanazawa and Campbell32]. Without full representation of those from diverse backgrounds, research results will not be generalizable to all who are infected with HIV.

Overview of the VAT

The overarching purpose of the VAT was to bring diverse community voices into the research design and implementation processes for work being done at SRTI to promote the All of Us Research Program. Therefore, VAT members were selected to represent the diversity of the All of Us participant community of which 80% must include individuals underrepresented in biomedical research based on race and ethnicity, biological sex at birth, gender identity and sexual orientation, living with physical or mental disabilities, barriers to accessing care, and others from disadvantaged backgrounds including those of low economic status or educational attainment and those from geographically isolated environments. All of Us also has the goal for the dataset to include 50% of individuals who are UBR by race/ethnicity [Reference Denny and Rutter1]. 21 of 28 (75%) of the All of Us VAT includes members from underrepresented backgrounds based on race/ethnicity. VAT members were recruited from a network of All of Us partners, including patient advocacy groups and community organizations, to create long-term partnerships between researchers and participants.

Through a series of recurring meetings, VAT members are invited to provide structured and unstructured feedback on all aspects of the All of Us Research Program including messaging, user experience, self-guided biosample collection, electronic health record sharing, and privacy protection including data security practices.

Recruitment and membership

The public learned about VAT membership opportunities through partner outreach networks, including through a variety of non-profit organizations, PatientsLikeMe (an online health-focused social platform), and All of Us community partner groups [Reference Bradley, Braverman, Harrington and Wicks33,Reference Fair, Watson, Cohn, Carpenter, Richardson-Heron and Wilkins34]. Through these networks, the VAT recruitment announcement was shared via email and online forums and remained active for approximately two months. While we risked excluding some members of the community, because of national reach and limited opportunity for meeting in-person on a regular basis, we required VAT members to have internet access, which candidates indicated on the brief, online application form. Upon submission, applications were reviewed and scored by the SRTI team based on their participation in All of Us (preferred but not required), and their experience in community advocacy work, health equity, and related topics, and ability and desire to represent one or more UBR groups. Similar to the initial recruitment process, we accept new VAT member applications at the beginning of each calendar year and announce the opportunity through our partner and social networks. Current VAT members are welcome to invite individuals in their networks to apply. Candidates with the highest application scores were invited for a virtual interview with the SRTI team. Applicants were scored on a scale of 1-10 with consideration for previous experience on community advisory boards, identifying as a member of an underrepresented community, having a chronic condition, involvement with community-based organizations, and ability to commit to VAT member responsibilities such as meeting attendance. After virtual interviews, the SRTI team re-reviewed and updated their application score based on their interview performance. Candidates with the highest overall score were offered an opportunity to join the VAT. VAT members receive an annual honorarium and travel funds if they are invited to attend meetings.

Formation and meeting structure

In May 2018, the VAT was formed with eight members from the community and four staff members from SRTI. All new members receive a welcome packet that lays out the following ground rules for participation:

-

1. Respect: Treat each other and others’ opinions, ideas, and contributions with respect. Be mindful of language and try not to interrupt each other.

-

2. Confidentiality: We often share internal documents that can’t be shared or reposted anywhere. What we share outside of social media posts to our page is considered private unless otherwise noted.

-

3. Honesty: Please share your honest opinion – it will help make us better! With respect and privacy, it will help us to be more open and honest during our meetings.

All meetings are managed by the SRTI staff through internal weekly planning meetings. The VAT members are invited to attend a virtual meeting for one hour and member attendance and participation are voluntary. With the initial VAT membership, meetings were scheduled quarterly, but meeting frequency was changed to every six weeks as the VAT grew to ensure newer members had ample opportunities to pose questions, provide input, and connect socially with the team. We also frequently communicate with members and ask for feedback between meetings. VAT participation is expected for at least one year; however, there is no limit for the number of years an individual can remain on the VAT.

In an effort to feel connected as a community, meetings begin with a wellness check to provide the attendees the opportunity to share how they are feeling or something of interest in their personal lives, such as a holiday, trip, or activity. The wellness check is intended to promote group engagement, allow the members to get to know each other on an individual level, and provide the opportunity for the group to learn from each other. These types of interpersonal exercises helped our team develop a bond, which, as research suggests, positively impacts members’ perception of their participation as well as the longevity of their participation [Reference Pinto, Spector, Rahman and Gastolomendo35]. The wellness check is followed by the main topic of discussion. Meeting topics are generated by four SRTI staff based on the latest research activities being planned, and the broader SRTI team is welcome to generate pertinent discussion topics as well. Topics are generally geared towards seeking feedback from the VAT and can range from deciding on whether to add a new participant survey to how personalized genetic results are disseminated. VAT members can also propose topics which can be included as future agenda topics if deemed valuable for group discussion. For meetings with high attendance, virtual breakout rooms can be used to promote more active participation among attendees and help SRTI staff more effectively moderate the discussions.

All meeting minutes are shared with the VAT membership and subsequently shared with all SRTI All of Us staff. VAT members also receive a recap of key points after each meeting, which includes notes, a group photo, and a weblink to access the audio recording.

Community representation

The current VAT consists of 28 community members, ranging in ages from 18 to 76. Members reside across the US in locations ranging from suburban to rural in the states of Arkansas, California, New York, North Carolina, Louisiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, and Washington D.C. Several racial and ethnic groups are represented including Black/African American, Hispanic, White, American Indian, and Asian, and there is also representation for the sexual and gender minority (SGM) community (Fig. 1). VAT members represent groups with at least 9 chronic conditions and 23 affiliated advocacy organizations.

Figure 1. The demographic profile of the 28-member virtual advisory team (VAT) includes 75% UBR race/ethnicity members.

Impact on the program

Since its inception, the All of Us Research Program has been influenced by the VAT in both tangible and intangible ways. In one example, the importance of a new participant survey was highlighted by a founding VAT member who is a person of color. The survey is focused on social determinants of health (SDOH) as one way to better understand the health of marginalized and underrepresented communities. SDOH are social, economic, and environmental factors that impact an individual’s overall health and well-being [Reference Thornton, Glover, Cené, Glik, Henderson and Williams36]. The additional survey enables researchers to correlate a participant’s health status with social and environmental factors. The VAT member’s input was part of the information relayed to program leadership to guide their decision on whether to add the survey. Although the VAT member’s input was not the sole reason the survey was added to the program, their input signifies how an engaged community can play an active role in public health research initiatives.

In another example, a VAT member, who is part of the SGM community, identified a scenario where study results that were accessible to the public could include a combination of data points that could potentially be used to identify All of Us participants who are members of the trans community. He voiced this privacy issue to the All of Us Governing Committee, which is responsible for reviewing and vetting research projects, and the board took the issue seriously. After several conversations about the potential breach of privacy, the Governing Committee recommended involving two members of the SGM community in the project to strengthen their voices and raise issues that may be otherwise overlooked. This action could set a precedent for how researchers engage minorities in research, highlighting the importance of including diverse communities in decision-making processes.

VAT as an entry point

All All of Us participants are offered opportunities to volunteer for All of Us. However, VAT members are offered additional opportunities considering their unique role and experience within their community. For example, VAT members are invited to participate in the planning and development of program-wide messaging amplification initiatives for All of Us. VAT members who volunteer to be part of these activities are provided with the necessary training and resources to be successful within and beyond their local community (Table 1).

Table 1. List and descriptions of volunteer opportunities that are made available to virtual advisory team (VAT) members

Discussion

Community participation in health research, whether done in-person or virtually, is increasingly recognized as a process that can improve how all research studies are prioritized, designed, carried out, and applied to real-world scenarios [Reference Anderson and Getz22]. To enhance participation efforts, community engagement should be an ongoing and iterative process with clearly defined and communicated community partner roles and bidirectional trust and transparency [Reference Han, Xu and Mendez37]. Diversity across advisory board membership is critical to ensure broad perspectives are considered to meet the needs and experiences of all demographics.

CABs (VATs in our specific case) are a proven model to achieve meaningful community engagement for various types of health research. Due to the persistent underrepresentation of individuals of non-European descent in clinical trials, along with the negative impact of social determinants of health, health disparities, and variations in medication responsiveness affecting these communities, it is crucial to involve diverse groups in the research process from the outset as advisory board members and participants [Reference Williams, Smith and Boyd38].

Lessons Learned

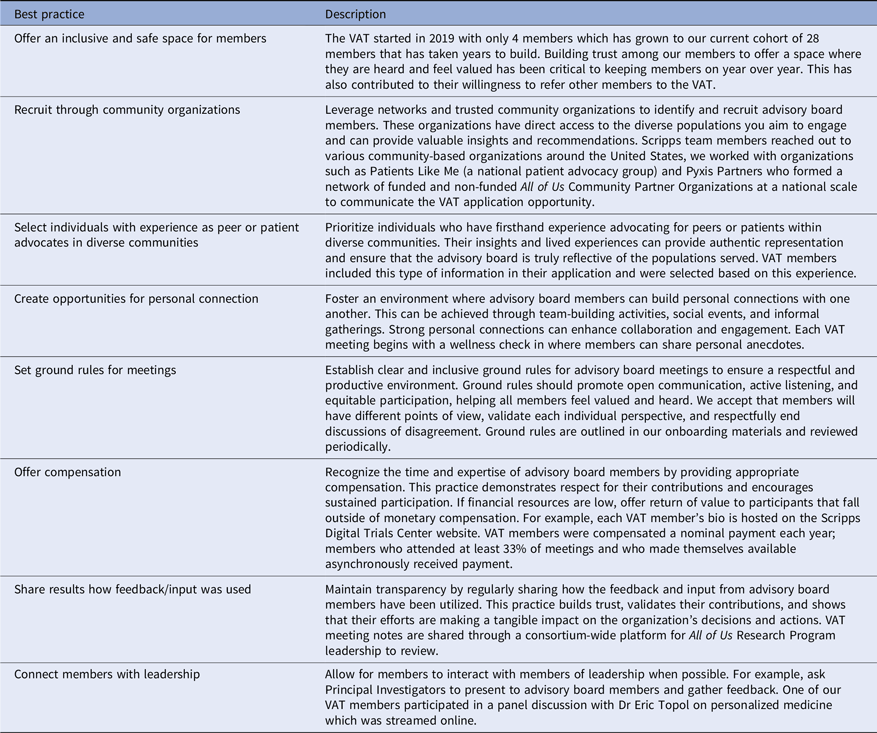

CPBR guidelines recommend early formation of a CAB, ideally while the research question and geographic focus are being developed [Reference Yuan, Mayer, Joshweseoma, Clichee and Teufel-Shone39]. Early integration of a CAB into the research design process can help create an equal power balance and develop trust between researchers and community members from the outset of the project. Also, offering hybrid (both in-person and virtual) meeting formats will help accommodate a broad spectrum of member preferences and their available resources. It is important for investigators to maintain flexibility to adapt to the board’s needs throughout the study. Creating a recruitment strategy that prioritizes diversity lends itself to establishing an advisory board in which multiple perspectives can be shared with the research team to address concerns and contribute to essential aspects of the program. Ensuring diversity across the research team is also an important factor so that perspectives from diverse individuals are included to study health disparities and inequities that persist in our society [Reference Kingsford, Mendoza, Dillon, Chun and Vu40]. Table 2 contains a summary of best practices from this work.

Table 2. List of best practices for recruiting and engaging diverse advisor board members

Future Steps and Considerations

While the overarching purpose of the VAT was to incorporate diverse community voices into research design and implementation, ensuring representation remains a significant challenge. The digital divide continues to limit individuals’ access to a variety of digital technologies, particularly those in rural, low-income, and otherwise marginalized communities. If someone doesn’t have access to broadband Internet to participate in a video conference, they can participate by phone and mechanisms to provide feedback asynchronously (e.g., via email, text, or other communication platform) should be considered. This approach could also help include individuals who want to participate in a CAB or VAT but don’t have time between work and family commitments to attend a scheduled meeting.

Additionally, investigators should be willing to share their experiences from their own outreach strategies to build a collective knowledge base, particularly for decentralized studies that rely heavily on digital technologies. Including VAT members to review the results of the research is another consideration, for that would further strengthen and amplify the investigator-participant partnership and ensure the information is presented in a clear manner for all represented communities.

Conclusion

Input from UBR individuals and communities is critical in healthcare and medical research. The formation of a CAB (in our specific case, a VAT) is an effective method to bring communities from urban and rural regions and from diverse backgrounds together to inform culturally appropriate engagement strategies to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in public health research. However, proper oversight and structure are key in keeping board members connected and engaged to effectively carry out their responsibilities. Furthermore, adapting to the needs of the CAB is an essential element for long-term success. The combination of CBPR and digital technologies has the potential to promote public health for all.

Acknowledgments

Our work would not be possible without the participation and valuable input of our VAT community members, many of who reviewed and contributed to this manuscript. We would like to thank and acknowledge each and every one of you for your contributions: Lottie K. Barnes, Phyllis Bass, Craig Braquet, Linda Carper, Sandra Cooper, Blanca Equihua-Kwon, Samantha Fields, Megan Gillespie, Shereese Hickson, John Hall, Hetlena Johnson, Christopher K. Lee, Bibiana Mancera, Estela Mata, Juana Mata, Crystal Martinez, Alyshia Merchant, Lee Merriweather, Bernadette Mroz, Joe O’Connor, Karla Rush, Angie Stark, Brandy Starks, Susan Tomasic, Kathryn Toussaint-Williams, Christine Von Raesfeld, and Daniel Uribe

-

This manuscript is dedicated to Gus Prieto. Gus was a founding member of our All of Us Virtual Advisory Team and was a passionate patient advocate for those with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. His positive spirit lit up a room (even virtually) and was a constant reminder of why we are so dedicated to the work that we do. Gus has said, “I am more than my disease, and I fight for my family and for those who live with this disease. Together with the support of our VAT, we will continue our work in supporting those who continue to fight.”

Author contributions

JP conceptualized the manuscript. GV, JP, LS, DR, MP, and JMV contributed to drafting the manuscript, and all authors (GV, JP, LS, DR, MP, YP, and JMV) contributed to editing the manuscript. GV, DR, MP, and YP conducted the work of recruiting VAT members, collecting and analyzing data, and conducting VAT meetings. JMV takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Funding statement

This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the Department of Health and Human Services; National Institute of Health; Office of The Director; All of Us Research Program (grant numbers U24OD023176 and 1OT2OD035580-01). This work was, in part, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) All of Us Research Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the NIH.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.