Introduction

The Council of University Classics Departments surveys of 1995 (CUCD, 1995) and 2012 (CUCD, 2012) demonstrated a restricted set of approaches to Latin teaching in UK universities with little evidence of activity outside grammar-translation and graded reading. Despite this, in the 2012 survey, some United Kingdom university tutors made claims for the benefits of experiencing more varied pedagogy, including communicative Latin, in their own previous study and in Summer School Immersion events (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2016a). In schools, a number of challenges continue to provide motivation to move away from current norms of provision (Forrest, 1996; Lister, 2007; Hunt, 2016). Meanwhile, in America, changes in curriculum and methods are being proposed and implemented to meet the challenges of falling enrolment on Latin and other Classics courses.

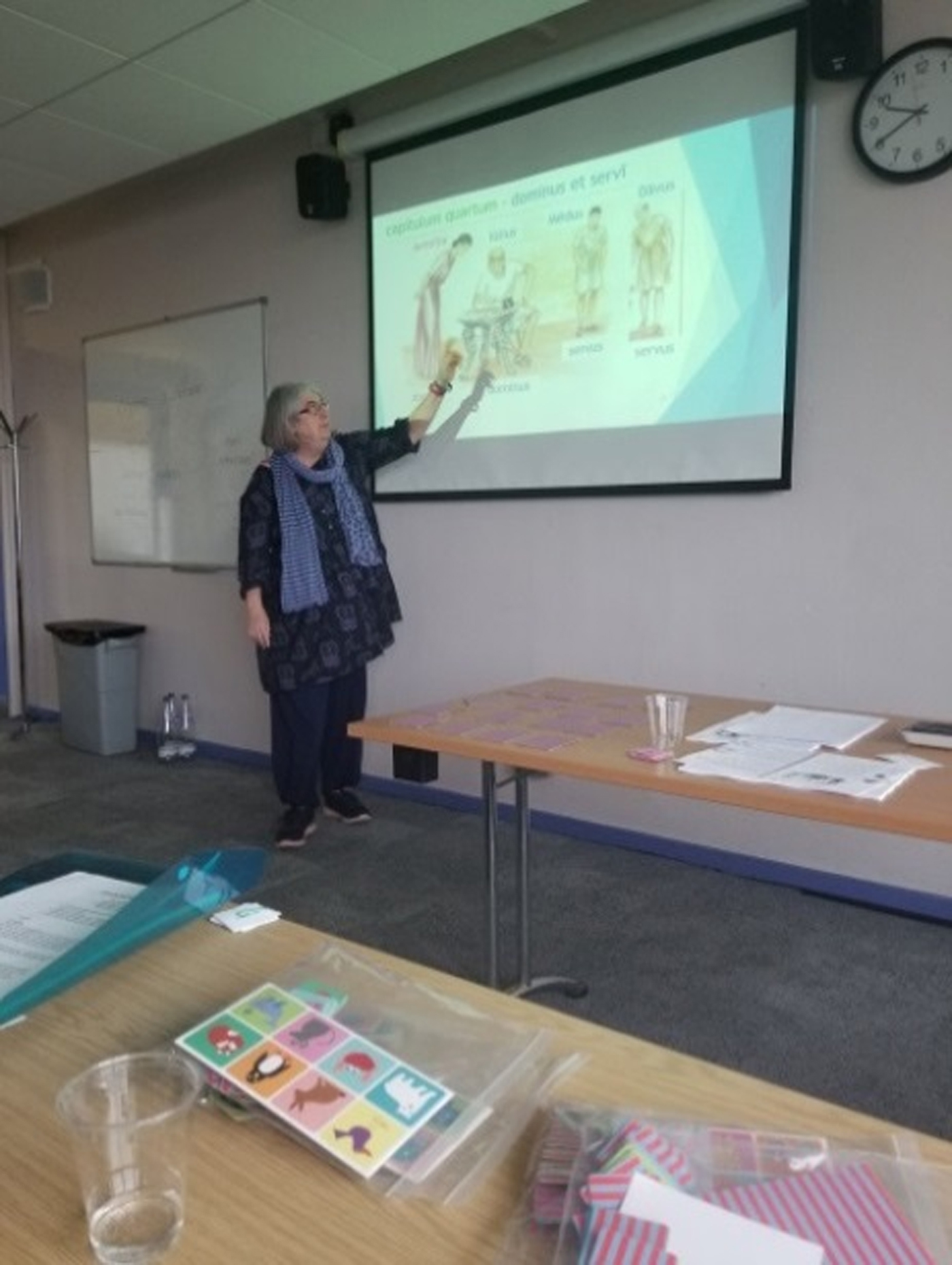

In a panel presented at the Classical Association Annual Conference at Leicester in April 2018 a number of papers were presented which affirmed the need for change and proposed and demonstrated some steps that could be taken towards implementing broader pedagogical approaches to Latin teaching in schools and universities. These approaches have the potential to provide benefits for our students and to strengthen the sustainability of Latin teaching in our organisations. The panel was supplemented by the workshop ‘Enlivening Latin Pedagogy in Practice’ where participants could experience demonstrations of a number of different teaching techniques and took part in a variety of learning activities. These were led by panel presenters and teachers with varying degrees of experience in communicative teaching.

Latin is alive!

Steven Hunt (University of Cambridge)

Over the years, there have been a number of spurs to change the way in which Latin has been taught in UK schools. Among these are the removal of the Oxbridge matriculation requirement in 1962, the increase in the number of comprehensive schools, and the imposition of the National Curriculum (Forrest, 1996; Lister, 2007; Hunt, 2016). Several factors beyond the control of teachers are now combining to make the provision of classical subjects even more challenging in schools. These include the loss of short-course GCSEs, the near abandonment of AS levels, the trend for schools to offer no more than three A levels, the removal of the Classics Suite A level qualification and the crisis in funding across schools and particularly in the sixth form, most of which can be attributed to the policies of the Conservative –Liberal Democrat Coalition Government (Hunt, Reference Hunt, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musie2018) and after. The author of this paper posited that in this educational environment, the teaching and assessment of Latin at GCSE and A level needed to undergo radical change if it was to be sufficiently attractive to students for them to undertake the courses and so that schools would remain willing to finance their teaching. The paper advocated the investigation of a number of possible solutions: the return to provision of different pathways to achieve the current qualifications, the development of more explicitly outward-looking qualifications which provide stronger arguments for their inclusion in the general curriculum and which make them a better fit with the university experience of Classics more generally, and the adoption of different forms of assessment designed to suit the needs of learners rather than those of government. More specifically, the paper briefly explored some of the rationale behind communicative approaches to the teaching of Latin, as drawn from examples in current US practice, and considered whether such approaches might help achieve some of the solutions.

Teaching Latin using the target language

Clive Letchford (University of Warwick)

The teaching of Latin in United Kingdom schools and universities in recent years has tended to be polarised between users of a graded reading approach exemplified by the Cambridge Latin Course and others who use the more traditional ‘grammar-translation’ method. Drawing on extensive experience at both school and university level, and sensing that a more varied pedagogy inspired by modern languages would have benefits, the author of this paper decided to explore ways of incorporating more active use of Latin in a university context. In the summer of 2017, the author therefore attended a four-week summer school at the Accademia Vivarium Novum in Rome, held entirely in Latin, and based on the text book Familia Romana by H. Ørberg. This course is 54 §3 Papers inspired by the work of W. H. D. Rouse and the Direct Method developed for modern languages. It uses a carefully designed text book to ensure a thorough, consistent approach to vocabulary and grammar acquisition and provides a framework around which Latin can be taught communicatively through the medium of Latin. Some of the approaches of the summer school together with the text book have been incorporated into the first-year beginners’ course at the University of Warwick in the 2017/18 academic year. This paper set out some of the key features to consider when incorporating a communicative approach based on this text as part of a time-pressured university course, and described the successes and challenges of this initial period of implementation.

The spice of life: on the pleasures and pitfalls of expanding pedagogy

Mair Lloyd (The Open University)

This paper followed on from doctoral research into the status quo in UK university Latin teaching and the benefits and challenges of using Latin as means of communication within and outside the classroom (Lloyd, 2016). It reported on the lived experience of attempting to put the implications of that work into practice in both a UK GCSE Latin teaching environment, and as part of a UK university ab initio Latin course. It highlighted the contrasting constraints of each context and the implications for the successful introduction of a wider variety of teaching approaches, including those that incorporate communicative activities, into classroom settings. These experiences were illuminated through the consideration of theoretical perspectives on language learning. The paper demonstrated the desirability of a more eclectic approach to Latin teaching, while acknowledging the sometimes painful process of introducing change.

varium et mutabile: rethinking the Latin curriculum

Laura Manning (University of Kentucky)

Due to a number of factors, enrolments in Latin programs are dwindling. Responding to this problem, a small and committed group of teachers has started a grassroots movement in some American schools, with the stated goal of teaching Latin and vernacular languages via more active teaching methods. The implementation of these methods has seen varying degrees of success. This paper described the state of the current movement in America, some of the methods that are being tried, and how these methods are received and perceived overall in American schools. In this paper, the author posited that change in teaching methods alone will not be sufficient to promote the sort of lasting transformation that will be necessary to sustain our discipline through the current crisis, let alone into the coming millennium and beyond. Education theorists from Dewey (1916) to Eisner (2005) have addressed the questions of what curriculum means—and whom it serves. Theoretical changes, however, are slow to make their way to the classroom. Meanwhile, some educators have begun to equate curriculum with textbook series, while others conflate curriculum with second language acquisition terminology. As a result, teachers are hard pressed to explain just what curriculum means, and are often unprepared to design curriculum for their schools. In the current climate, our profession has both opportunity and obligation to redesign the Latin curriculum, both to appeal to students, and to promote the value of Classics for an educated citizenry.

Storify of Panel Tweets: https://storify.com/CressidaRyan/cucd-catb-virtue-of-variety-panel

CUCD and CATB Workshop: Enlivening Latin Pedagogy in Practice

The workshop provided participants with the opportunity to experience a number of teaching techniques, games and activities inspired by communicative approaches to Latin pedagogy. The session was led by teachers and students with varying degrees of experience in introducing these approaches into their schools and universities. These included presenters from the ‘Virtues of Variety’ panel. The workshop concluded with an open discussion on the benefits and challenges of enlivening Latin pedagogy.

Figure 1. | Workshop presenters (L-R): Clive Letchford, Mair Lloyd, Rachel Plummer, Fergus Walsh, Laura Manning, Steven Hunt.

Session One: Beginners’ Latin Games & Activities

Rachel Plummer

Teaching Experience: I began teaching Latin in 2014 with The Iris Project, taught History with The Brilliant Club from 2015–18, and took part in a training scheme with The Latin Programme in 2015. My aim when teaching Latin and Classical Civilisation is to teach as creatively as possible by including games and activities not normally used in the traditional method of teaching Latin. I am currently teaching Latin and Classical Civilisation at GCSE and A level.

Spoken Latin experience: beginner! I have attended a one-day spoken Latin workshop at UCL, and a two-week spoken Latin summer school in Poznan, Poland. I have tried to incorporate spoken Latin into my own classroom using techniques observed at these events, and have had very positive reactions from my students.

Activity 1. Numbers – Snap!

Aim: To familiarise pupils with Latin numerals and their names, up to 10 or 20.

To facilitate communication in Latin at a basic level.

Materials: One numerals handout per person

One set of numerals cards up to 10 or 20

Method: Begin by giving each student a numerals handout and a set of cards. Students can play in pairs or small groups and should shuffle their cards together before dividing them into equally sized piles. Each player takes a pile. Students take it in turns to turn over one of their cards and place it with the numeral face up, saying the number out loud in Latin. When one student turns over a card which is the same as the previous player's card, they should place their hand over the pile of cards and shout ‘SNAP!’ The first to shout and place their hand on the pile of cards gets to add the cards to their own pile. The next player should then begin the game again. The winner is the person who has all the cards in their hand at the end of the game.

Extensions: Once the players seem to have learned the numerals 1–10 and no longer need to check their list before saying them, you can make this game harder by adding in the next set of 11–20, or by getting them to add the number on their card to the previous card, e.g. septem plus quattuor est undecim.

Activity 2: Noun vocabulary – Snap!

Aim: To familiarise pupils with vocabulary by using picture cards rather than number cards.

To facilitate communication in Latin at a basic level.

Materials: Sets of cards with pictures which correspond to the vocabulary to be learned.

Method: As above, but students have to say the noun out loud. Matching the picture to the word helps students associate the word with an image, rather than having to translate back into English, and begins the process of using Latin as a means of communication.

Activity 3: Noun vocabulary – Pairs

Aim: To familiarise pupils with vocabulary.

To facilitate communication in Latin at a basic level.

To encourage team-working.

Materials: Set of cards with pictures which correspond to the vocabulary to be learned. Each picture/vocabulary item must be included twice.

Method: Shuffle the cards and place them face down in a square. Each player or team takes it in turns to turn over 2 cards to try to find a matching pair. Players must say the name of the item pictured out loud in Latin. This can be facilitated by the teacher asking quid est? Players finding a matching pair can remove those 2 cards from the board and add them to their pile. Whoever has the most cards at the end of the game wins. Players who do not find a matching pair must turn the cards back over and then the next player takes his/her turn.

Activity 4: Verb vocabulary – magister dicit…

Thanks to The Latin Programme Footnote 1 for teaching me this game.

Aim: To familiarise pupils with verb vocabulary.

To get pupils to associate verbs with actions, rather than translating into English.

Materials: None required. You may want a list of verbs to hand which you want the students to learn.

Method: This is the Latin equivalent of ‘Simon says…’ Students stand and each time the teacher says magister dicit… (+ verb) they must act out the verb, e.g. magister dicit… dormire, pugnare, latrare. Verbs can be given in the infinitive, imperative, however you prefer – don't worry too much about grammatical correctness; the aim is to strengthen the pupils’ association of an action with the corresponding Latin verb. Once students have begun to learn the verbs/actions, you can occasionally miss out magister dicit… to catch people out. Students who still perform the action lose a life; after they have lost three lives, they are out of the game and must sit down and watch.

Activity 5: Vocabulary and simple sentences – quis es?

Aim: To build up vocabulary around appearance and colours.

To begin communicating with other pupils in basic sentences.

Materials: A set of Guess Who? game boards (can be purchased from most £1 shops).

A list of relevant vocabulary of colours, body parts and items of clothing which might be visible.

Method: The game boards allow pupils to select one person to be, while guessing from the selection who the other pupil (or team of pupils) might be. Students must ask ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions of the other team to narrow down who they are.

e.g. habesne oculos caeruleos? – ita

habesne petasum purpureum? – minime

The first to identify which person the other player or team is pretending to be is the winner.

Extension: For pupils with a higher level of confidence/fluency, you can discard the game boards and get pupils to assign a celebrity persona to their opponent. The name of the person should be written on a post-it note and stuck to the opponent's head, and each person must ask questions to guess who they are. Students take it in turns to ask questions, and the first person to guess their celebrity persona wins.

e.g. femina sum? – ita

cantatrix sum? – ita

Taylor Swift sum? – ita!

Rachel Plummer

Session Two: Principles of communicative approach for learning vocabulary

Steven Hunt

Teaching Experience: I began teaching Latin, Classical Greek, Ancient History and Classical Civilisation in 1987 in a school in suburban London. I now run the Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) Initial Teacher Training course at the University of Cambridge.

Spoken Latin experience: beginner! I attended a two-day spoken Latin workshop at the Paideia Institute, Fordham University, New York in 2016 and have tried some of the methods described below with year 7 and 8 Latin students and with my PGCE teacher trainees. Reactions have so far been positive.

The idea is to provide students with multiple opportunities to hear and use new vocabulary in an engaging and purposeful context.

Activity 1: quis est’

The key idea is to reinforce a limited range of new vocabulary through frequent repetitions and choral responses. The importance of students hearing the sounds of a new language as well as associating them with images has been shown to be significant in helping them to retain vocabulary (Pachler, Evans, Redondo, & Fisher, Reference Pachler, Evans, Redondo and Fisher2004). As students become more proficient in associating simple images with words, the teacher reduces the image scaffolding or increases the vocabulary range or increases the grammatical load. Assessment is possible for the teacher to judge when the students have understood by listening carefully to student responses and to make judgements about when to move on to the next level. Personalised questioning is possible by the teacher asking differentiated questions in the target language.

The teacher shows a ‘Caecilius’ character puppet and asks: quis est? If no response is forthcoming, the teacher provides the target vocabulary: est Caecilius. Then the teacher repeats the question: quis est? and expects the response est Caecilius repeated back. The teacher repeats this sufficiently until the student response is near total. This is repeated with the other puppets – Metella, Clemens and so on. At the second or third puppet, the teacher models a new form: either reversing the word order answer from est Metella or est Clemens to Metella est or Clemens est, with the expectation that students will follow the new word order. The teacher may also introduce new vocabulary such as pater est or servus est. In this way the teacher increases the number of vocabulary items by offering students alternatives: est Caecilius an Metella? or est pater an coquus?Footnote 2 These alternatives can be common nouns/proper nouns, synonyms, opposites, and so on.

Activity 2: quid facit?

The next step beyond is to introduce verbs.

Teacher: Metella sedet an scribit?

Students: Metella sedet.

Teacher: Grumio sedet an laborat?

Students: Grumio laborat.

Teacher: coquus laborat an scribit

Students: coquus laborat.

And so on. It is better for the teacher and students to use complete phrases Caecilius laborat rather than single words Caecilius or laborat. Further repetitions can be gained with different verb tenses, phrases or syntactical constructions:

Teacher: coquus laborabat an scribebat?

Students: laborat or coquus laborat.

Teacher: coquus in culina laborat an in tablino?

Students: ’in culina or in culina laborat or coquus in culina laborat.

Teacher: coquus cenam coquit an scribit?

Students: coquit or cenam coquit or coquus cenam coquit.

None of these choral response activities need last more than ten minutes, in the author's view, and can be used as adjuncts to other lesson activities.

Of the three possible responses, the teacher should aim that students answer using the third, completed sentence rather than the first single word. The key is in using them regularly with students to activate more of the senses and to help the student access and consolidate meaning without having to think to translate. In every case vocabulary is not being introduced in isolation: it is being introduced with visual and aural/oral support and in meaningful phrases and sentences. Research suggests this is the best way to develop a student's knowledge and understanding of new vocabulary – ‘You shall know a word by the company it keeps’ (Firth, Reference Firth1957, quoted in Quigley, Reference Quigley2018).

I am aware that this activity is not strictly communicative in the sense that the students are expected to repeat back a correct response to the presentations made; there should be more flexibility in their responses as images/situations become more complex and their own skill at forming Latin becomes more developed and more sophisticated the more times it happens.

Could one foresee a time when the students themselves start to take over the pictures themselves and start asking each other what is going on? In my mind, yes: the teacher needs in the initial stages to model how to do the activity and then the students – given sufficient vocabulary – can move on to creating their own question and answer sessions based around an image or set of images. I touched on this in my chapter about communicative approaches in the book Forward with Classics! (2018) where the discussion focused on an extract from the Bayeaux Tapestry; but I could equally see such micro-conversations taking place around, for example, the model sentence pictures from the Cambridge Latin Course, a drawing from ecce Romani or any other text book, or even from an image from the contemporary world.

Session Three – Activities centred round reading a text

Mair Lloyd

Aimed At: Beginners in the first few weeks of Latin. Also useful for new Latin speakers.

Session Aims: To introduce numbers 1 to 10 and some new vocabulary including sacculus, nummus, pecunia, mensa. To practise hearing and understanding words in different forms (here mostly nouns in different cases).

Materials: slides for introducing some vocabulary before meeting it in a reading, coins and a purse or small bag for introducing numbers and reinforcing vocabulary, Lingua Latina per se Illustrata: Familia Romana text book, for reinforcing vocabulary already introduced orally in the context of a story. Some new vocabulary will also be encountered in the context in the story itself.

Activity 1

Show pictures introducing new vocabulary and talk about the pictures, repeatedly using the new vocabulary in a number of forms (using the forms they have learned or are learning).

Point to things and say, for example:

ecce xxx / hīc est xxx. (nominative)

in pictūrā, videmus xxx (accusative)

Ask simple questions, for example:

estne xxx in pictūrā? quis est in pictūrā? quis est servus Iuliī?

Activity 2

Introducing counting and practising numbers. With a slide of the numbers visible, at least initially, count out a number of coins (say 10).

ūnus nummus, duo nummī, trēs nummī …. decem nummī.

Now put the coins in a little bag (decem nummī in sacculo sunt). xxx nummōs in mensā pono. quot nummī in sacculō sunt?

Move on to xxx nummōs in manū habeō, xxx nummōs in mensā sunt. quot nummī in sacculō sunt?

Activity 3

Choice of:

• Read through Capitulum IV Scaena Prima from Lingua Latina per se Illustrata: Familia Romana with expression, holding up props as appropriate.

• Read through Capitulum IV Scaena Prima as a play with students reading parts – encourage vigorous participation.

• Dictate part of Scaena Prima and ask questions about the part dictated.

• Read out part of Scaena Prima and ask students to draw a picture of the scene and label it in Latin.

• Ask questions in Latin and/or English about the action of Scaena Prima or part of it.

• More number practice through asking how many nummī/servī there are in pictures.

Session Four: Enlivening Latin Pedagogy in Practice

Clive Letchford

Clive Letchford completed his degree at St John's College Cambridge in 1983 and went on to pursue a career in the City. He took a year out to complete a PGCE in 1997 and then taught Latin and Greek in schools before joining the University of Warwick In September 2009 as a Teaching Fellow. Clive also has experience of intensive language teaching on the Joint Association of Classics Teachers’ Greek Summer School and as a Principal Examiner on Greek for OCR at A level, and has published jointly an anthology of Greek texts for OCR GCSE. [email protected], @letchford_clive

• ten years’ teaching experience in secondary schools, nine years at university.

• Experience of speaking Latin - nine months.

• Experience of teaching in Latin - six months

• Level of pupils: beginners up to A level standard

Activity 1: dic aliter

This is aimed at undergraduates in their second term of Latin. The first shows how vocabulary is related to previous vocabulary with a similar or opposite meaning. The second shows how this exercise can be extended to grammatical ideas and deals with deponent verbs, each related to ordinary verbs with a similar meaning.

Several words have been taken from a story you have just read Identify a synonym for each of the words below which could be used in the same context:

Q: revertitur ad villam

A: revenit ad villam

Q: quia

A: quod

Q: cruor

A: sanguis

Q: vestimentum induit

A: togam induit

Q: Titus vero

A: Titus re vera

Q: via angusta

A: via non lata

Text

nāvēs multae simul ē portū Ōstiēnsī ēgrediuntur. inter eōs hominēs quī nāvēs cōnscendunt est Mēdus, quī ex Ītaliā proficīscitur cum amīca suā, Ly-diā. Mēdus, quī Graecus est, in patriam suam regredī vult.

Ly-dia eum sequitur, omnēs rēs suās sēcum ferens. sōle oriente, nāvis eōrum ē portū ēgreditur, multīs hominibus spectantibus.

Mēdus faciem Ly −diae intuētur et ‘nōnne gaudes’ inquit, ‘mea Ly-dia, quod nōs simul in patriam nostram regredīmur?’ Ly −dia ‘gaudeō quod licet tēcum venīre, at nōn possum laetarī quod omnēs amīcās meās Rōmae relinquō.’ dē oculīs Ly-diae lacrimae lābuntur.

Change the underlined deponent verbs into active verbs with the same meaning.

A useful resource for synonyms in Latin can be found in Wagner's Lexicon Latinum (1878) available online at http://www.lexica.linguax.com

The activity could be repeated with antonyms.

Activity 2: carmen

This activity can be adapted for any level. I taught the song, rustica puella, to my students nine weeks after they had started to learn Latin. The song can be sung or chanted, with rhythmical accompaniment.

Activity 3: Erasmus: A dishonest Londoner

The Latin is taken from the selections at TheLatinLibrary.comFootnote 3 and is a version from the 1515 edition of his Adagia. The basic story is that a friend of Erasmus, a doctor, has cured a Londoner who then refuses to pay him what he has promised, using a poor excuse to avoid paying his debt.

I have undertaken this type of activity with a few post-A level students (although it would work equally well with Year 13 students), and with some Italian exchange students. The aim is to stay in the language as much as possible with students paraphrasing in simpler Latin to show they understand, or with me defining vocabulary in a similar manner. I have found that this encourages them to guess the meaning of unfamiliar vocabulary and widens their vocabulary generally. They also enjoy Erasmus’ content - it is much more down to earth than the literature or history of the classical period. The next stage would be to discuss in Latin the themes which Erasmus is writing about.

Instructor says: Please feel free to paraphrase in simpler Latin to show you have understood (and perhaps help others to understand). If you want to say you understand ita (yes); if you want clarification about a word quid significat X? (what does X mean?).

Session 5: Three games

Laura Manning – University of Kentucky

We demonstrated three games requiring different types of active student engagement in Latin. These tasks are well-suited for increasing students’ vocabulary, and are easily adapted to support texts of varying complexity. The low-stakes nature of the tasks allows students to participate without undue concern.

Activity 1: Argus

Argus provides a simple, active twist on a traditional Bingo game allowing students to process vocabulary input in the target language. The caller defines the game words in Latin. The players make a guess as to connections between the words described by the caller and the words on the individual's Bingo card. Finally, the players explain their winning answers. The rationale is simple. To capitalise on the benefits of student choice in learning, students choose from a list to complete their game cards. The list keeps the task manageable for students of less experience. Defining the words in Latin allows the teacher to provide additional input for students, using varied grammatical structures and vocabulary during the course of the game, which is reinforced by hearing the thinking of successful game players.

Sample list of words:

annus, arma, āthlēta, caelum, canis, currus, deus, equus, īra, lītus, nox, poēta, puer, rēgīna, silva, urbs

Argus grid (‘Bingo’ card) with words inserted by student, ready for game to start.

Activity 2: aliis verbis

For the aliis verbis task, the students describe words, phrases, and ideas from a selected text, paraphrasing in their own Latin. For the purposes of this demonstration, we used sentence-level texts of varying complexity. Students share their own connections with others in small, cooperative groups to minimise worry about speaking in a large group setting. All students are using the language actively to negotiate meaning with each other for an extended period of time; all groups are working simultaneously.

Possible texts from which to choose (first sentences only!):

1. arma virumque canō.

2. in pictūrā est puella, nōmine Cornēlia.

3. Caecilius in viā dormit.

4. Gallia est omnis dīvīsa in partēs trēs.

5. tantaene animīs caelestibus īrae?

Activity 3: quis sum?

For the quis sum? game, the students are doing most of the talking in the larger group setting, and therefore providing and interpreting genuine input from each other. Students are motivated to ask questions for a real communicative purpose, in order to find out the identity of the main player. The main player asks the question, quis sum? and the students from the rest of the group ask questions to identify the main player. Such questions might take the form as follows:

esne homo?

minime!

tu es animal?

ita vero. sum animal!

tu es animal in aqua? etc

The authors consider that communicative approaches such as those mentioned above have more potential for greater student engagement and sense of achievement than some of the traditional grammar-translation approaches used in schools and universities. The next issue of the Journal of Classics Teaching (39) will have a set of articles from the US perspective on a similar theme, edited by Keith Rogers.