Reading is an essential part of learning a language. MFL teaching divides language learning into four separate skills: reading, writing, speaking and listening. As teachers of Latin, we focus on only two skills: reading and translating. These two skills are hard to distinguish in the Latin classroom, with many Latin teachers equating translation into written or spoken Latin with reading (Hunt, Reference Hunt2022). I think it is safe to say that Latin teachers have translating down to an art. True reading, however, is something more elusive in the classroom, and many other reading activities are anything but (Hunt, Reference Hunt2022), and attempts at reading often fall back into translating (Olimpi, Reference Olimpi2019). Reading should come before translating – the establishment of meaning should come before and be quicker than the process of translation (Hunt, Reference Hunt2022). In my view, the ancient world should not be at the other end of an hours-long slog through dictionaries and grammars. That isn't reading. If we want to get better at reading and if we want our students to read better, we could look at MFL teaching and the use of extensive reading there (Carter, Reference Carter2019).

What follows is an account of my PGCE research project, in which I introduced a class of 14 Year 10 boys to the concept of extensive reading in Latin. For seven lessons, spread over four weeks, the whole class, teachers included, would read a Latin novella silently for the first ten minutes of the lesson. It was a largely positive experience for those involved.

Background

I will briefly explain the principles of extensive reading, its benefits and negatives for language learning, and give some examples of other successful Latin reading programs, before moving on to my research.

Extensive reading is a pedagogical approach to teaching languages based on reading widely, often and for pleasure (Eunseok, Reference Eunseok2019) and with a focus on comprehension and meaning (Day and Bamford, Reference Day and Bamford2002). It can also be called free voluntary reading, sustained silent reading and self-selected reading, depending on its implementation (Krashen, Reference Krashen2004). Extensive reading is used to teach proficiency and literacy in both first and second languages and is a staple in English and MFL classrooms. During my PGCE, I observed silent reading being used in both of my placement schools, with silent reading and library lessons in the Key Stage 3 English curriculum, Key Stage 3 form times involving periods of silent reading, and swathes of reading material in MFL classrooms read purely for their content and not their grammar.

Extensive reading is a popular choice in these classrooms because it brings many benefits for both teachers and students. These benefits range from the acquisition of grammar and vocabulary to reduced anxiety. These benefits and others will be discussed below.

Firstly, extensive reading can promote the incidental acquisition of vocabulary (Aka, Reference Aka2020; Duong et al., Reference Duong, Montero Perez, Nguyen, Desmet and Peters2021). Extensive readers read large amounts of text and meet partially known or unknown words multiple times (Suk, Reference Suk2021). This has been proven in a study, called the Clockwork Orange study, which used Anthony Burgess' dystopian novel A Clockwork Orange to test participants' acquisition of the book's slang vocabulary (Nadsat) while reading. Results showed that between 50 and 96% of the new Nadsat vocabulary was acquired, with an average of 76%. Participants picked up an average of 45 Nadsat words just by reading a novel (Krashen, Reference Krashen2004). Extensive reading promotes vocabulary learning, and it might be more enjoyable than memorising vocabulary items by heart.

Additionally, other incidental acquisitions can be made through extensive reading. Gains in grammar, spelling and comprehension and reading rate can also be made (Aka, Reference Aka2020; Krashen, Reference Krashen2004; Nakanishi, Reference Nakanishi2015; Yamashita, Reference Yamashita2013). For example, in a blind test of the ability to use the Spanish subjunctive, the best indicator for the ability to use this piece of grammar was the amount of free voluntary reading done in Spanish (Krashen, Reference Krashen2004). There is also an indication that reading improves writing (Krashen, Reference Krashen2004), and it has also been noted that 94% of the time students in free reading programs do as well as or better than students in traditional programs in reading comprehension tests (Krashen, Reference Krashen2004).

One benefit of extensive reading for students is that it is less anxiety-inducing and more engaging than regular teaching. The free voluntary and self-selected versions of extensive reading, in which the learners choose what book to read from an appropriate selection, satisfy the learner's reading needs and interests, increasing their engagement in the reading and therefore in the learning opportunities (Suk, Reference Suk2021). Anxiety is reduced because reading has no right or wrong answers, there are no questions to answer publicly, and achievements are not declared to the rest of the class, which means that judgement from peers is minimal (Yamashita, Reference Yamashita2013) and anxiety about getting things right or wrong is also minimised. This lack of anxiety leads to a lowered affective filter, one of Krashen's principles, which allows for greater language acquisition (Krashen, Reference Krashen1982). Extensive reading fosters greater engagement and lower anxiety in students, which in turn leads to greater learning opportunities. Increased engagement means less disruption for teachers to handle.

However, there are some negatives to extensive reading that must be mentioned, although many of these come not from the concept itself but from poor implementation and planning.

First, extensive reading is not a quick fix. For all the gains students can make in vocabulary, grammar and spelling, they can be slow to appear (Aka, Reference Aka2020). Gains in general reading ability appear first, with linguistic improvements, such as in vocabulary and grammar, coming later (Yamashita, Reference Yamashita2008). The longer the program the greater the improvement of student ability (Nakanishi, Reference Nakanishi2015). Unfortunately, these slow gains can mean that extensive reading programs are scrapped before the benefits can be seen (Aka, Reference Aka2020). For teachers and students to reap the rewards of an extensive reading program, they must stick to the program for at least six to twelve months, based on studies available (Nakanishi, Reference Nakanishi2015).

Additionally, extensive reading will not by itself produce high levels of competence (Krashen, Reference Krashen2004). There are numerous benefits to extensive reading, as shown above, but these extensive reading programs have all been accompanied by other forms of teaching, be that a form of grammar teaching or comprehensible input. This is especially important as extremely competent readers may comprehend what they are reading without paying attention to word endings, agreements, punctuation or grammar constructions (Krashen, Reference Krashen2004; Yamashita, Reference Yamashita2008). Researchers have found a better language learning effect from reading supplemented by activities than from reading alone (Eunseok, Reference Eunseok2019). An element of direct teaching is therefore required alongside extensive reading.

Finally, there are some accounts of extensive reading programs that have been negatively received by students. Two studies into school-wide extensive reading programs found that student motivation decreased and that students on average disliked the experience, with only 19% of students in one study thinking that it was a good idea (Krashen, Reference Krashen2004) and half of the students in the other saying that they did not participate (Herbert, Reference Herbert1987). A possible reason for these negative reactions could be that the extensive reading time was done at the same time every day for every student regardless of whether they were in English, History, Physical Education or Design and Technology lessons (Krashen, Reference Krashen2004). However, we cannot know if the students' perspectives would have been different if the extensive reading program had been implemented in a better way. This is an example of possibly poor implementation affecting the results and efficacy of an extensive reading program.

There are significant benefits to extensive reading programs, though there are negatives to consider when implementing them. I will now turn to the specifics of extensive reading in Latin classrooms, which helped to inspire my extensive reading program. I will discuss how it can be established along with several examples of successful programs.

I have never observed extensive reading in a Latin classroom. Instead, what is often utilised in Latin classrooms is intensive reading, the dissection of text using dictionaries and grammars to create literal translations that require shaping into something understandable. Even in reading courses like the Cambridge Latin Course and Suburani, intensive reading is often the modus operandi (Olimpi, Reference Olimpi2019). The key distinction between extensive and intensive reading is that the former maximises language input so that students can comprehend and acquire language, while the latter teaches students the ability to parse (Ramonda, Reference Ramonda2020; Yamashita, Reference Yamashita2013).

However, extensive reading is gaining popularity as part of Comprehensible Input-based (CI) teaching (also called Active, Spoken or Communicative Latin) and this is increasingly popular in the United States, although its audience in the UK is slowly growing (Hunt, Reference Hunt, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018; Lloyd and Hunt, Reference Lloyd and Hunt2021). Spoken Latin forms a large part of CI-based pedagogy, but other input-rich activities, such as extensive reading, are also utilised. Teachers often have an FVR (Free Voluntary Reading) library, filled with Latin novellas. Latin novellas are short stories or books written in comprehensible Latin, usually by Latin teachers, specifically for learners of the language. They are significantly more accessible than authentic, or even adapted Latin literature, because they have a highly repetitive vocabulary list and are written primarily for meaning and not style or grammar. There are currently more than 115 Latin novellas available, of varying difficulties and genres, including non-fiction (Piantaggini, Reference Piantaggini2022b).

The following examples of extensive reading programs come from practitioners of CI-based teaching in the United States, each one showing a different way of implementing extensive reading in the Latin classroom.

One of the most well-known users of extensive reading is US Latin teacher Lance Piantaggini. He writes a blog about teaching Latin using CI and suggests many ways to use novellas and extensive reading in the classroom. One of the ways that he uses novellas in his classroom is by having 15 to 20 minutes of free choice reading once a week (Piantaggini, Reference Piantaggini2021), but he also mentions independent reading, whole class reading, book clubs, and creating debates about novellas to encourage rereading and deeper reading (Piantaggini, Reference Piantaggini2022a). His particular style of teaching, both with spoken Latin and extensive reading, has led to a 100% student retention rate going from his Latin I to Latin II classes, with 98% of his students, across four year-groups, opting to continue Latin for another year in 2016 (Piantaggini, Reference Piantaggini2022a). Piantaggini himself is also the author of over 25 Latin novellas.

Another US Latin teacher who uses novellas, and also writes them, is Andrew Olimpi. He began using novellas with his third-year class, but as more accessible novellas were made available, he started to use them with his first- and second-year students, with five to ten minutes of reading at the beginning of each lesson three times a week (Olimpi, Reference Olimpi2019). Olimpi had previously seen many students drop out between his Latin I and Latin II classes, but after his program, he has seen significant numbers going into Latin IV (Olimpi, Reference Olimpi2019).

Colin Shelton is a US university lecturer who has structured his Latin for Post-Beginners course, for students with some but not much experience of Latin, around novellas. His students read the same novella as each other for at least 20 minutes per day, alongside grammar review activities. Lessons used spoken Latin and CI-based activities, discussing themes and parallels to the novella content, and pop-up grammar instruction when needed. Students were polled anonymously about their progress in the reading (Shelton, Reference Shelton2021). Shelton found that the students who read novellas reached the expected proficiency target for first-year courses, and those continuing into their second year held their own or outperformed the students from the regular course (Shelton, Reference Shelton2021).

Lectio otiosa is what John Piazza calls his free voluntary reading program, which he does with his students twice a week. Students choose their book from a table in the classroom and everyone reads for between eight to fifteen minutes. After reading, students have a further four minutes to complete their reading logs, in which they write down the title of the novella, how much of it they read, write or draw something that describes what they read, and finally write down at least one memorable Latin word. Students are never told what novella to read, nor what level, but the difficulty of each book is made clear to students. Piazza also encourages his students to contribute to the Latin library by writing their own comprehensible Latin stories (Piazza, Reference Piazza2022).

Finally, Miriam Patrick trialled several variations of an extensive reading program in her classroom, including group projects, independent reading logs and twice-monthly book clubs to discuss the novellas. The various trials showed Patrick that accountability measures often hindered the program's success (Patrick, Reference Patrick2019). Nevertheless, Patrick has continued to use extensive reading in their classroom.

The research

Now that I have mentioned the many benefits and examples of extensive reading, I will now move on to my research. I will begin with my research questions before explaining how I conducted my research, and then I will discuss my findings and observations.

The absence of extensive reading in the Latin classrooms that I observed during my PGCE despite its benefits, and the lack of research into extensive reading in Latin classrooms in general, prompted me to choose this topic for my research project. Due to it being a small-scale research project, I decided to look at student perspectives of extensive reading, as this is not typically the focus of extensive reading research (Abrar et al., Reference Abrar, Herawati and Priyantin2021) and it was more attainable for the time I had allowed.

My research questions were as follows:

1. What are students' attitudes towards reading Latin and reading in the classroom?

2. What are students' attitudes towards a short-term extensive reading program?

3. What are students' opinions of the available Latin reading material (adapted authentic texts, classical-themed manufactured text, non-classical-themed/non-fiction manufactured text)?

I conducted my research while on placement at an all-boys feepaying school. The group that I chose to work with for my project was the Year 10 Latin class (students aged 15). Due to the way that the school set Latin lower down in the school, this class was high-achieving in terms of grade, but within the class, there were some differences, particularly in their speed of understanding new content. There were 14 boys in the class, two of whom had been picked out by the school as ‘scholars’, the school's Gifted and Talented program with each boy having a teacher-mentor in the school. One boy is on the autistic spectrum, but upon discussion with the class teacher, it was decided that no changes were required for this research. Before starting their GCSE examinations content, these students were taught using the Cambridge Latin Course, Books 1 to 4. Students had five lessons, each of 50 minutes, per fortnight.

For this research, I chose four Latin novellas to offer to the class. Each of these was available online for free and was printed into booklets so that each student could, theoretically, have one of each to keep. These novellas were Cloelia Puella Romana by Ellie Arnold; Hercules Maximus by Laura E.G. Berg; Sisyphus Rex by Peter Sipes; and Astronomia: Fabula Planetarum by Rachel Beth Cunning. This selection was based on the novella's linguistic level, its genre and level of interest, and its accessible formatting. This selection also has a mixture of mythology, history and non-fiction. I also compiled several of John Taylor's Latin Stories, because, despite it not being a novella and not intended for extensive reading, I believed that this would be a familiar format for the students to fall back on if needed.

My research itself was conducted as follows (Figure 1):

Figure 1. Research program.

My data comes from the student questionnaires and my informal observations of the class behaviour and student conversations. Students were also given the FLRAS again at the end of the program to compare pre- and post-reading responses, but this gave too much data to be adequately discussed in my research project and so was omitted.

Data and findings

The discussion of my findings will be in response to each of my research questions in turn. Each discussion will use information gathered from both the post-reading session questionnaires, the final questionnaire, and my classroom observations. The names of students have been anonymised, and I have chosen to replace them with those of the early Roman emperors, including Caesar.

RQ1 – What are the students' attitudes towards reading Latin and reading in the classroom?

I observed the class for several weeks with their regular teacher before I began teaching them and leading them in the extensive reading program. Their lessons were typically divided between translating the set texts for the GCSE and practising unseen comprehension and translation exercises with pop-up grammar lessons as and when features come up. The class had covered all of the GCSE grammar before I arrived at the school in January. The majority of class time was spent crafting translations in which every word was accounted for and the closest thing to extensive reading was the unseen comprehensions, but as the story and vocabulary changed every week it would have none of the benefits of extensive reading. The students' main skills are translation and intensive reading but there is little evidence for extensive reading.

My observations were reflected in the Foreign Language Reading Anxiety Scale (FLRAS). In response to certain statements, 86% of the class said that they often end up translating word by word. 43% said that they enjoyed reading Latin and 36% neither enjoy nor do not enjoy reading, but only 14% felt confident when reading Latin. The spread of responses can be seen in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Number of students responses to the FLRAS statements with SA = strongly agree, A = agree, N = neutral, D = disagree, SD = strongly disagree.

Throughout the program, the post-reading questionnaires have asked students if they are enjoying reading in class. These responses can reveal whether it is actually the reading that students do not like, or if it is simply the method of reading that they use. Only three students said that they were not enjoying reading in class at any time, which means that 79% of the class did enjoy reading. This might suggest that those students who remained neutral in the FLRAS changed their opinion.

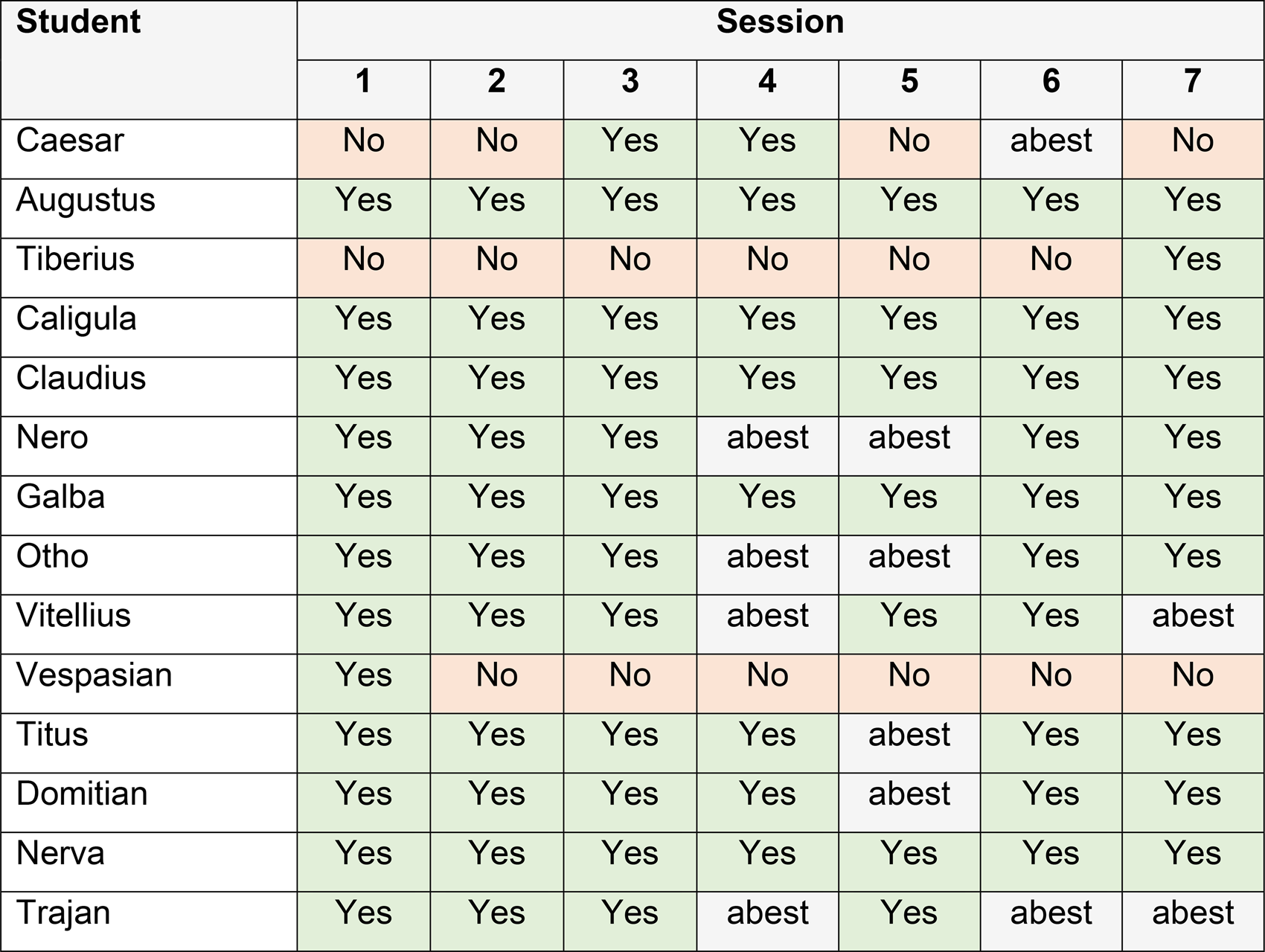

One of the students, Caesar, who said they were not enjoying reading throughout the program started not enjoying reading but changed their mind after a few sessions. From a conversation between Caesar and another student before the third lesson in which they were comparing how much they had read; it seems that Caesar had not realised that there was a glossary at the back of the book. They later wrote in the post-reading questionnaire that they enjoyed reading more this time because they changed books and realised that there were glossaries. However, they later stopped enjoying it (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Responses to ‘Overall, are you enjoying reading in class?’ across the seven sessions.

Two boys were also consistent in not enjoying reading in class. One, Vespasian, enjoyed the first session, but did not enjoy the rest, perhaps due to the novelty of doing something different. The other, Tiberius, only enjoyed the last session, perhaps because he knew that it was the last session.

My observations of the class and the results from the reading anxiety scale show that intensive reading and translation are more familiar to students, and extensive reading is rarely done. The reading anxiety scale suggests that the class's attitudes towards reading Latin are generally mixed. While most students enjoy or don't not enjoy reading Latin, fewer students feel confident when reading Latin. During the program, 11 out of 14 students consistently enjoyed reading Latin.

RQ2 – What are students' attitudes towards a short-term extensive reading program?

While the previous research question established students' attitudes towards reading in general, this question will focus on their attitudes towards the specific way that I implemented an extensive reading program in their classroom. To answer this research question, I will look more specifically at the students' comments about the program, its benefits, and ways in which it could be improved, taken from the post-reading questions and the final questionnaire. It should be noted here that this class has no culture of extensive reading in the Latin classroom and this experience was entirely new and novel to them.

As a result of the compromise between myself and the head of the department and the class teacher, the 12 students who were present in lesson six were asked if they would like to continue for another week. 75% said they wanted to continue. Two students said no and one said maybe. Those that said no explained that ‘I don't really see the point of it. I'd benefit more from doing actual work’ and ‘I feel like I'm not learning anything new’. It should be noted that extensive reading is not explicit teaching, as they are used to, but a gentle acquisition of language, so it may not feel like students are learning something concrete every lesson.

The students were asked if they found the activity valuable in the final questionnaire after the program. 86% of students found the activity valuable, including Tiberius who has consistently expressed their dislike of the experience. They commented that it ‘improved Latin sight reading and summarising’. 76% of students said that they would do this again, and 29% said that they would do this outside of school. Although, when asked previously, no students had done any reading outside of school during the project, despite having access to the books.

In each post-reading questionnaire, students had the opportunity to write a comment about the program or that lesson. Not all students made use of this, but the comments that were made will be discussed now. The comments have been categorised into vocabulary; reading speed and comprehension; and confidence and mindset.

Despite noticeable improvements in vocabulary being known to be slow to appear and not being monitored during this study, the students taking part in extensive reading themselves felt that their vocabulary skills had improved. Extensive reading benefits vocabulary learning because the number of unique vocabulary items is limited and repeated across the text. Some of the students seem to have recognised this as they commented that ‘words that were repeated in the story I easily remembered if we translated a story later in class’ and that reading ‘helped me learn words in a more productive way’. Even Caesar, who said that they did not learn anything during the project, said they were ‘sort of learning new vocab’. Previously this class would be learning vocabulary from the Eduqas examination vocabulary list for weekly tests; however, two students commented that seeing words in context made learning the words easier.

Another improvement that they noticed was in their reading speed and comprehension ability. Although this is another aspect in which extensive reading is slow to make noticeable differences, many students made comments about the reading becoming easier, both within the silent reading period and later in the lesson when reading other texts.

I think it has improved my reading speed slightly. (Otho)

It makes reading Latin easier and strengthens the understanding. (Domitian)

It helped me later in the lesson to read Latin quicker. (Vitellius)

A final benefit noticed by the students was their confidence and mindset. One student wrote ‘I feel I can approach a piece of Latin text more confidently’ and ‘I feel a bit more confident when translating Latin and that my Latin knowledge has extended’. I did not observe a noticeable difference in the students' confidence levels in lessons, but that does not invalidate their comments.

More students, however, mentioned that starting the lesson with 10 minutes of silent reading was relaxing and helped them focus on Latin, warming up their ‘Latin brain’. This warm-up time is a familiar comment to me, as the English department at my first placement school started every Key Stage 3 lesson with ten minutes of silent reading, even extending the time if the students seemed like they need it, and the reasoning behind it was, not only to get students to read but also to get them focused. This was especially important if the lesson was after a break or Physical Education.

Some of the students commented on the following:

It was a relaxing experience. (Domitian)

It was relaxing and was a good warm-up to each lesson if you know what I mean. (Augustus)

It meant that I was able to get into the swing of it before the lesson began. (Nero)

These ten minutes turned my Latin brain on and prepared me for translating further in the lesson. (Caligula)

It made me feel in a good headspace for tasks later on in the lessons and I found the stories a good way of relaxing before working. (Claudius)

It was a nice, calm way to start the lesson and it was less stressful than translating something as a class. (Otho)

However, from my observations of the class during the project, I noticed that as we progressed, the class grew less focused on the reading. Settling down into reading took longer and they were more liable to chat amongst themselves despite it being a silent reading period. It has occurred to me that the students may be enjoying not doing anything at the beginning of the lessons, that it may devolve into an extension of break or lunchtime if the rules are not enforced. It is also worth noting here that, while I did not notice this in my observations, Vespasian did not read during one of the sessions. I was made aware of this in the post-reading questionnaire in which they put that they read ‘none’ and ‘DK’ (don't know) what happened in the story. Vespasian has a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder and was one of two students who were consistent in their dislike of the program. An interview with them may have been helpful to find out why they disliked the program and why Vespasian was not reading, but this does show the usefulness of the accountability measure in the study. The unrest may have settled back down if the program had continued and become a regular part of lessons, but I cannot know for certain.

Additionally, when I started the program with the students, I explained why they were doing it, that it was research for my teacher training and that it would benefit them in certain ways. One student left a comment after the first session asking how this would help their GCSEs. In the next lesson, I explained how this would help them to improve their Latin. There is a slight possibility that, like a placebo or Hawthorne effect (Wikipedia, 2022), the class was hyperaware of any possible improvements to vocabulary and reading speed because they have been told that there would be improvements. However, I did not mention improved confidence, relaxation, and mindset, so these benefits are entirely from the students' perceptions.

As well as general comments, the students were also asked if there was anything that they would change about the reading program. The main changes were about the length of time given over to reading in each lesson and about the material on offer. I will expand on the students' comments about time allocation below, but comments about reading material will be covered under RQ3.

When asked about what they would change about the in-class reading period, most students said that they would change nothing or that they couldn't think of anything to change. Three students suggested having more time because ‘they [can't] quite get into a story in the given time’. Two wanted less time or to not have it at all, that ‘ten minutes was too long’ and that it was a ‘waste of time’. Naturally, these were two of the students who disliked the program. The relationship between enjoyment of the program and the amount of time they wanted is clear; those who enjoy reading want more time, and those who don't want less. When asked about general improvements for the program as a whole, two students mentioned reading for longer again. Another two wanted to read for less time, though one wanted less time for more days ‘as it would give everyone a chance to read a few books’.

So, despite noticeable benefits as a result of extensive reading being slow to appear, the students involved seem to feel that they have made some improvements in their vocabulary, reading speed and comprehension. They also appreciated that the activity was relaxing and gave them time to engage their ‘Latin brains’ before doing harder GCSE work in the rest of the lesson. Even students who did not enjoy the experience have noticed some improvements. Most of the recommended changes were about the length of time, with most asking for more time, or less, but for more than seven lessons. However, when it comes to the students who disliked the project and the reading, their views are far from on the fence. Ultimately, most students found the activity valuable and said they would do this again, even outside of school.

RQ3 – What are the students' opinions of available Latin reading material?

‘I have realised that you can read Latin outside of the course and it can be fun.’ (Nerva)

Students had a choice of four novellas and one compilation. A summary and description of each choice were given to the class at the beginning of lesson two when they read for the first time. Students also had the option to change what they were reading whenever they wanted.

The most popular books were Astronomia, by Rachel Beth Cunning, and Hercules Maximus, by Laura E.G. Berg. Students enjoyed Astronomia because it was factual, had a good mix between myth and fact, had a more unique vocabulary, such as technical terms, and had straightforward grammar and vocabulary; however, not all students enjoyed the facts. Students enjoyed Hercules because they liked Disney's Hercules when they were younger, and the story was very simple and easy to understand; however, some found that this simplicity made it very boring. Three students read the same book in all seven sessions; one tried a different book, didn't like it and then went back to their original choice; a couple of students managed to finish reading a book entirely.

The least popular books were Latin Stories, the compilation from John Taylor, and Sisyphus Rex, by Peter Sipes. Part of this is because fewer boys read them but the comments that they received were more negative than the others. About Latin Stories, Domitian said that the stories were boring, and Vespasian said that they were more interesting. I believe that Latin Stories suited Vespasian more because they were a collection of GCSE-style passages and not meant for extensive reading, and they were particularly focused on preparing for their exams, whereas Domitian was enjoying the reading aspect. Sisyphus Rex was only read by one student, Tiberius, who said that it was ‘very, very confusing’.

It should be noted that the majority of students enjoyed reading all of the books they tried. There were only three occasions where students strongly disliked a book, which was Latin Stories, Sisyphus Rex and Astronomia. There were several common themes for why students liked or disliked the novellas.

Students disliked not having glossaries or vocabulary lists and having an overly repetitive story to read. This was a particular problem for those reading Hercules, which only provided definitions for the words deemed by the author to be too difficult or rare, but this was sparse and there was no collated vocabulary at the back as there is in others. Repetition of language, while useful for exposure to the language, proved irritating for students, as well as reading a story that they already knew.

Some of the vocab is not on the side of the paper so reading is harder – sentences take longer to work out. (Claudius)

I struggled with the vocabulary today and I couldn't find some in the dictionary. (Galba)

I still enjoyed reading [Hercules] but I thought it was worse than Astronomia because it was highly repetitive, sometimes stating obvious things that were described in previous lines. (Otho)

I only read Astronomia and Hercules. I liked Hercules least because I already knew the twelve labours, so it began to get quite boring. (Vitellius)

The main themes for what made a book appeal to the students were: having a dictionary or glossary at the back for reference; they contained an interest of the students, such as mythology or astronomy; easy and comprehensible, but not repetitive.

Cloelia was easy to read and had a good dictionary / The dictionaries are good. (Tiberius)

I have an interest in astronomy. (Domitian)

I liked Disney's Hercules when I was younger. (Titus)

Easy to read and therefore to understand. (Nero)

There was variety and they varied in difficulty. (Galba)

I liked Hercules least because I already knew the twelve labours. (Vitellius)

I still enjoyed reading [Hercules] but I thought it was worse than Astronomia because it was highly repetitive, sometimes stating obvious things that were described in previous lines. (Otho)

It was very repetitive with short sentences and kept saying the same thing. (Galba)

The students were also asked about what else they would like to read, and what other materials could be included in the program. Seven students had no recommendations, but others suggested:

Harry Potter/parallel texts like the MFL penguin stories. (Titus)

More science and interesting questions. (Domitian)

More normal like non-fiction but in Latin. (Augustus)

Poetry from the Latin era. (Nero)

Lesser-known myth because I would learn that myth and I wouldn't already know what happens and so it would be more of a challenge to translate. (Otho)

Something about the conquest of the Roman army because that is what I am most interested in the Roman period. (Vitellius)

Some of these are already available in Latin, although I don't think Harrius Potter is comprehensible as of yet, and it would be wonderful to be able to offer them to students as part of a bigger extensive reading program. I hope that those novellas which are not available now soon will be.

On the whole, the students enjoyed the books that were on offer. They enjoyed books that appealed to their wider interests, be they mythology or science. Books that have comprehensive glossaries or dictionaries at the back of the book were greatly appreciated, and students found it easier to read and enjoy books that had them. The students have also recommended other things they would like to read.

Conclusions

The main purpose of this research project was to investigate the opinions and attitudes of a Year 10 Latin class towards an extensive reading program. I incorporated ten minutes of sustained silent reading into normal lesson time, changing nothing else, and used questionnaires, a foreign language anxiety scale and my observations to answer the three research questions.

The students generally had a mixed attitude towards reading Latin and reading in the classroom. Most of the reading done in the classroom was intensive or geared towards translation, and extensive reading was rarely done. Most students enjoyed reading but fewer feel confident when they read.

Their attitudes towards the reading program were generally positive. Three students disliked the experience at any point, but they were clear outliers in my results, and even they acknowledged some of the benefits. Students noticed improvements in their vocabulary knowledge, their reading speed and their comprehension level, and many commented on the beneficial mindset that the reading period instilled. Having a dedicated ten minutes to warm up for the activities later in the class was seen as important.

Finally, their opinions of the reading material were generally positive. They enjoyed stories that related to their interests, such as mythology or science, but they definitely enjoyed stories more when there was a comprehensive list of vocabulary at the back, as this supported their reading immensely. The students also gave some recommendations for other reading materials that they would like, including a comprehensible Harry Potter, authentic Latin poetry, tales from the Roman army, and other non-fiction.

Overall, my students had a positive attitude towards extensive reading and reading in Latin. This attitude was not unanimous, and some students did not enjoy the experience, but even they acknowledged the benefits of it. My study could have been improved, particularly regarding my data collection, and I wish I had been able to extend the research period and offer more choices in reading material.

While the results of my study are not generalisable, I do hope that the positive attitude of my students will encourage further research into extensive reading in the Latin classroom. I will attempt to incorporate more extensive reading into my teaching going forward and will look more at the element of my research on reading anxiety that did not make it into this essay.