Introduction

The purpose of this article is to encourage classical colleagues to develop their own illustrated talks to deliver to school assemblies (both senior and junior). In my experience, an illustrated talk goes down well with any audience (whatever its age) and can have an immediate impact on their view of the classical world (especially its ‘relevance’). Assemblies can be delivered in many ways: a talk; interactive; class presentation etc. This article concentrates only on the preparation and delivery of an illustrated talk. I have divided the article into four sections: the value of classical assemblies; tips on preparing and delivering assemblies; resources and copyright; and an example of a classical assembly (The Adventures of Theseus).

A. Value of Classical Assemblies

(i) You have the chance to interest a large audience in your subject. You may be talking to groups of 100 pupils or more without the constraints of syllabus/exam pressures.

(ii) You can explore different themes and ideas with complete freedom in the manner you choose (set talk or interactive). Images of vase-paintings, sculpture, mosaics, paintings and other objects demonstrate the lasting influence of the classics on later generations in a powerful visual way.

(iii) You get an instant reaction from pupils after each assembly whereas day-to-day teaching is usually a long-term process without the same kind of immediate feedback. This instant feedback keeps you on your toes and provides great encouragement!

(iv) You are talking to potential recruits for your subjects at GCSE and A level in senior schools and can develop assemblies for different Year Groups or several Year Groups together. For those who have never sampled the classics or those who have relinquished the subjects, an inspiring talk can remind them of the value of the classical world in ways they might not have supposed.

(v) You have the chance to inspire youngsters in junior schools and promote their enthusiasm for the subjects beyond their time at junior school. With Years 3–6, an illustrated talk can excite them at an early age and may encourage them to choose a classical subject later at senior school.

(vi) In schools where classical subjects are unavailable, an illustrated talk might create an interest in introducing the subjects (especially Classical Civilisation).

(vii) The school assembly is often an under-utilised resource for subject teachers. The chance of talking to a large audience is an opportunity worth seizing. It provides a great chance to encourage children to take an imaginative interest in the classical world. Longer talks (e.g. the Aeneid) can often be delivered over a series of assemblies to the same audience.

(viii) Headteachers or staff in charge of organising assemblies are usually very grateful for volunteers and are often happy to allocate several assemblies over a week in order to pursue a theme (e.g. Herakles’ Labours).

B. Tips on preparing and delivering an assembly

(i) Equipment needed: Laptop; USB (back-up); Laser-pointer; CD (music) for entry/exit; CD player; index-cards (talk).

(ii) Play some appropriate music while the audience is assembling (start) and leaving (end). It helps to set the atmosphere and settle them down.

(iii) Use index-cards/plain postcards to plan your points in note form for each picture. This will help you memorise your talk as you compose it.

(iv) Think pictorially and illustrate your theme with appropriate pictures and maps.

(v) Number your pictures and write a caption for each one to remind yourself of key points.

(vi) Make each picture come alive so your audience knows why you've chosen that particular picture.

(vii) Look at your audience and maintain eye contact. Try to deliver your talk without the index-cards as your talk will be much more effective. (Use the index-cards only as a prompt).

(viii) Be enthusiastic and try to keep your talk moving fluently at pace. Try to tell a story.

(ix) Have a dramatic opening and ending to create an impact at the start and at the finish.

C. Resources and Copyright

(i) Your own resources (digital photos) and departmental resources (digital photos, books etc)

(ii) Google Images*

(iii) e.g. Greek Myths handbooks (e.g. Tales of The Greek Heroes by Roger Lancelyn-Green)

*Copyright issues: www.copyrightuser.org is a very useful website to consult. It states that the use of copyright material is permitted for educational purposes as long as:

(a) The purpose of the use is non-commercial (i.e. you are not charging a fee for your talk).

(b) Sufficient credit is given to the author of the image.

(c) The use of the material is fair.

D. Example Assembly: The Adventures of Theseus (39 slides) based on R. Lancelyn-Green's version

This talk could be split into Theseus’ adventures on the way to Athens and Theseus and the Minotaur. Each slide has a caption or title to remind me of key points or for the audience to read. For the purposes of this article, we have not included every slide. The details give a flavour of the images and the sort of commentary. For full details, contact the author.

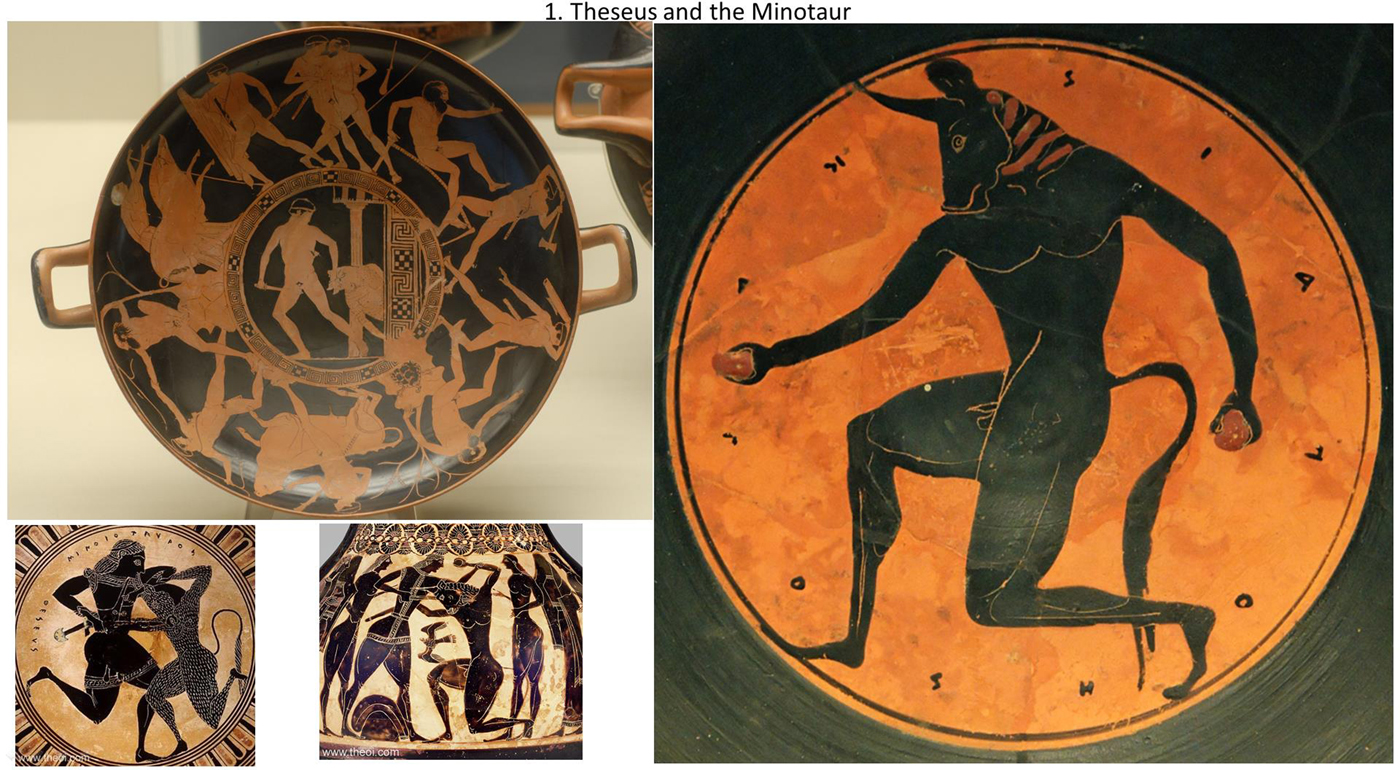

1. Theseus’ adventures (vase-painting with Minotaur at the centre of the vase-painting). Theseus the hero who killed the Minotaur; Theseus legendary king of Athens; Theseus great friend of the hero Herakles. (Point out Theseus taking the bull by the horns and killing the Minotaur; half-human, half-beast nature of the Minotaur).

2. Theseus lifts the stone to find the sword and sandals left by Aegeus (sculpture). Theseus was born in Troezen (map); the son of Aegeus, king of Athens, and Aethra, daughter of Pittheus, king of Troezen. (Point out Troezen and Athens on map)

3. Map showing location of Troezen and Athens (map). Aegeus had left Theseus to be brought up in Troezen; had a good start as a young lad (aged seven) meeting the great hero Herakles; demonstrated his courage on seeing Herakles’ lion-skin helmet which was so lifelike the other boys ran away in terror. Theseus attacked it with an axe! Theseus was inspired to follow Herakles’ example in ridding the world of monsters. (Point out Herakles’ distinctive dress: lion-skin helmet; great knotted club; bow and arrows; Herakless 4 th Labour – the Erymanthian Boar).

4. Herakles (vase-painting) inspires young Theseus; Herakles's 4th Labour (vase-painting). Aegeus had left a sword and sandals beneath a great rock to test his son Theseus when he came of age. If he lifted the rock and found them, he was to travel straight to Athens to help his father Aegeus against his enemies. (Point out Theseus, now a young man, straining to lift the rock to find the sword and sandals accompanied by his mother Aethra who points towards the startling objects underneath).

5. Theseus lifts the stone to find the sword and sandals left by Aegeus (Laurent La Hire – painting). Same as 4. (Point out Theseus’ immense struggle to lift the rock; Aethra pointing to the objects beneath; remind audience of Troezen and Athens on the map).

6. Theseus lifts the stone to find the sword and sandals left by Aegeus (Nicolas Poussin – painting).

7. Map showing Theseus’ journey overland from Troezen to Athens (map). Aethra begged Theseus to take the shorter, safer sea route to Athens to avoid the villains plaguing the land route but Theseus was determined to help his fellow men (like Herakles) and rid the world of villains and monsters. (Point out Theseus’ route and very briefly the monsters Theseus defeats on his way (as this talk concentrates on the Minotaur); point out shorter, safer route by sea).

8. Theseus defeats Periphetes the Clubman at Epidauros (vase-painting and map).

9. Theseus defeats Sinis the Pinebender at Corinth (vase-painting and map).

10. Theseus defeats Sinis the Pinebender at Corinth (illustration).

11. Theseus defeats Sciron beyond the Isthmus of Corinth (vase-painting).

12. Theseus defeats Sciron beyond the Isthmus of Corinth (2nd vase-painting and map).

13. Theseus defeats Cercyon at Eleusis (vase-painting and map).

14. Reminder of Theseus’ adventures so far (two maps – one illustrating villains’ abodes).

15. Theseus defeats Procrustes and fits him to his notorious bed (vase-painting).

16. Theseus defeats Procrustes and fits him to his notorious bed (2nd vase-painting).

17. Theseus meets his father and stepmother in Athens but does not reveal himself (illustration and map).

18. Theseus deals with the Cretan Bull at Marathon (vase-painting and map)

Theseus arrives in Athens and meets king Aegeus but his father does not recognise him. However, his wife (Medea the sorceress) recognises Theseus and warns king Aegeus against him. Medea persuaded Aegeus to send Theseus away to capture the Bull of Marathon which had been devastating the land and killing the local inhabitants in the hope he would be killed as many before him. (Point out Theseus’ arrival and reception in Athens; Aegeus unaware that this is his son Theseus; Medea glancing at Theseus suspiciously; Marathon (map); Theseus ‘taking the bull by the horns’ and leading it in triumph to Athens).

19. Theseus sacrifices the Cretan bull on the Acropolis (photo of the Acropolis). (Point out Theseus, with his club, ‘taking the bull by the horns’ and leading it in triumph to Athens; explain English expression ‘to take the bull by the horns’.) Theseus sacrifices the Bull on the Acropolis and prepares for a great feast with king Aegeus. Medea, alarmed at his success, persuades Aegeus that Theseus is a deadly threat to him and prepares a cup of poisoned wine for the feast. (Point out the Acropolis=High City; point out that Acropolis is just a high rock in Theseus’ time).

20. Theseus's stepmother tries to poison him but Aegeus recognises his son (W Russell Flint – painting). At the feast Theseus draws his sword ready to carve the best meat from the bull just as Medea offers him the poisoned chalice (picture). Aegeus recognises the sword and dashes the poisoned cup from Theseus’ hand. Father and son are reunited as Medea flees. (Point out Medea offering Theseus the poisoned chalice (left); Aegeus recognising the sword (top-right) and knocking over the poisoned wine on the table (top-right); Medea preparing to flee (top-right) as everyone looks at her; Acropolis visible in background (top-right); Aegeus recognising his son (bottom-right) and Medea preparing to flee).

21. Theseus learns about the Minotaur and King Minos’ tribute demands (vase-painting and map of Crete)

22. King Minos’ magnificent palace of Knossos (illustration and map of Crete showing location of Knossos)

23. King Minos’ magnificent palace of Knossos (2nd illustration of Knossos). Aegeus sends Theseus off with an army to defeat his enemies (his brother Pallas and his fifty sons). Theseus returns to Athens to find the whole city in mourning and discovers that King Minos of Crete has sent his ambassadors to demand the annual tribute of seven young men and seven young girls to be fed to the Minotaur (= the bull of Minos) in the Labyrinth on Crete. Minos, owner of the greatest navy in the Greek world, had imposed this punishment on Athens because his son had been killed while visiting Athens and trying to capture the Bull of Marathon. Minos, however, believed that the Athenians had murdered his son because of their jealousy of his great athletic skills and their jealousy of Minos’ great power. (Point out Crete (map) and location of Knossos (the great palace of Minos); the half-human, half-bull Minotaur; different interpretations of son's death; conspiracy-theories?)

24. Theseus leaves for Crete in a ship with black sails. Aegeus watches him leave (two illustrations). Theseus volunteers to go to Crete immediately to his father's great dismay and sets sail for Crete with the other ‘prisoners’. Aegeus makes him promise to change the ship's dark funeral sails to white ones on his return to show that he has been successful. (Point out Aegeus in great distress watching Theseus sail away; Theseus’ ship with the dark funeral sails and Theseus on deck; ship's eye to see where the ship is going and avert bad luck).

25. Theseus arrives, excels in athletic competitions and wins Ariadne's heart (two vase-paintings). Theseus and the young Athenians arrive at Knossos – Minos’ splendid palace with its many rooms, central courtyard and magnificent frescoes. (Point out location of Knossos (map); splendid palace; central courtyard; bull-leaping and dolphin frescoes). The young Athenians take part in racing and boxing contests before Minos and his court. Theseus excels in all the competitions and wins the heart of Ariadne, Minos’ daughter who determines to help him. (Point out typical foot-race (sprint) and boxing contest with one boxer submitting by raising his hand).

26. Ariadne helps Theseus enter the Labyrinth (Jean-Baptiste Regnault painting). Ariadne visits Theseus at night and gives him a ball of thread. She tells him to unwind it behind him as he makes his way to the centre of the Labyrinth and to follow it back to the entrance, if he is successful. Ariadne will wait for him at the door but Theseus must take her to Athens because she will not be safe after helping him to escape the labyrinth. Theseus promises to do so. (Point out Ariadne giving Theseus the ball of thread at night and the instructions for escaping the Labyrinth; Theseus entering the Labyrinth with the ball of thread and a sword while Ariadne clings to his arm; the entrance of the Labyrinth).

27. The Labyrinth of Knossos (mosaic; plan of the palace showing its complicated nature). Ariadne helps Theseus to enter the Labyrinth. (Point out Theseus ready to enter the Labyrinth with his sword drawn and clutching the ball of thread in Ariadne's hand; Ariadne's devoted glance towards Theseus; the entrance to the Labyrinth with the statue of the Minotaur at the entrance; the House of Theseus mosaic from Paphos (Cyprus) with its maze-like concentric circles representing the twisting Labyrinth with Ariadne, Theseus, the Labyrinth and the Minotaur all labelled in the central panel).

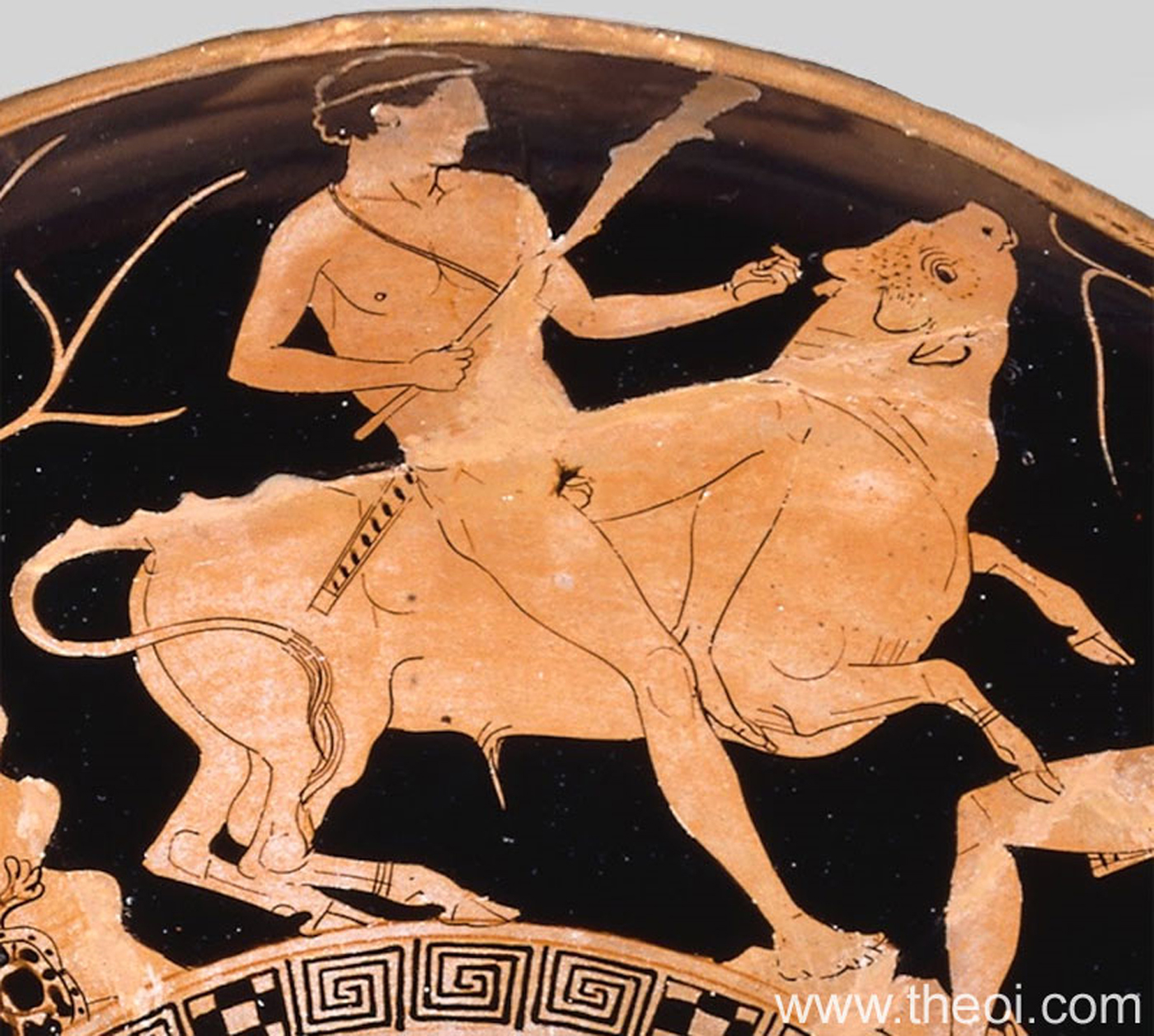

28. Theseus defeats the Minotaur (vase-painting). Theseus makes his way to the very heart of the Labyrinth to meet the Minotaur in the dim, gloomy light. He has already heard the Minotaur's bellowing from far away. Theseus meets the Minotaur at the very centre of the maze. Some versions say Theseus was armed (sword, club or axe); others that he defeated the Minotaur with his bare hands by continually striking it over the heart until it weakened, then ‘taking the bull by the horns’ and forcing its neck backwards until it cracked and the Minotaur lay dead. (Point out Theseus and the Minotaur doing battle at the centre of the Labyrinth; the Minotaur on his knees about to be defeated (mosaic); the complicated plan of Minos's palace – a confusing maze to a stranger and perhaps the origin of the Labyrinth?).

Same as 25. Theseus defeating the Minotaur. (Point out Theseus and the Minotaur's names in Greek (left); Theseus killing the Minotaur (left) with a sword; the Minotaur weak at the knees, kneeling and spilling blood (left); Theseus defeating the Minotaur (right) with the Minotaur kneeling and clearly shedding blood).

29. Theseus defeats the Minotaur (2nd vase-painting). Theseus kills the Minotaur. (Point out Theseus killing the Minotaur with his sword; the Minotaur down on his knees in a position of submission; blood pouring from his wounds; Theseus dragging the dead Minotaur towards the entrance of the Labyrinth (?) watched by Athene, patron goddess of Athens; point out Athene's spear, helmet and aegis (as goddess of war); explain the aegis and point out Medusa the Gorgon's face on the aegis).

30. Theseus and Ariadne set sail to Naxos (vase-painting of ship; map showing Naxos). Theseus and Ariadne set sail for Athens stopping at Naxos on the way. (Point out ship; the location of Crete, Naxos and Athens).

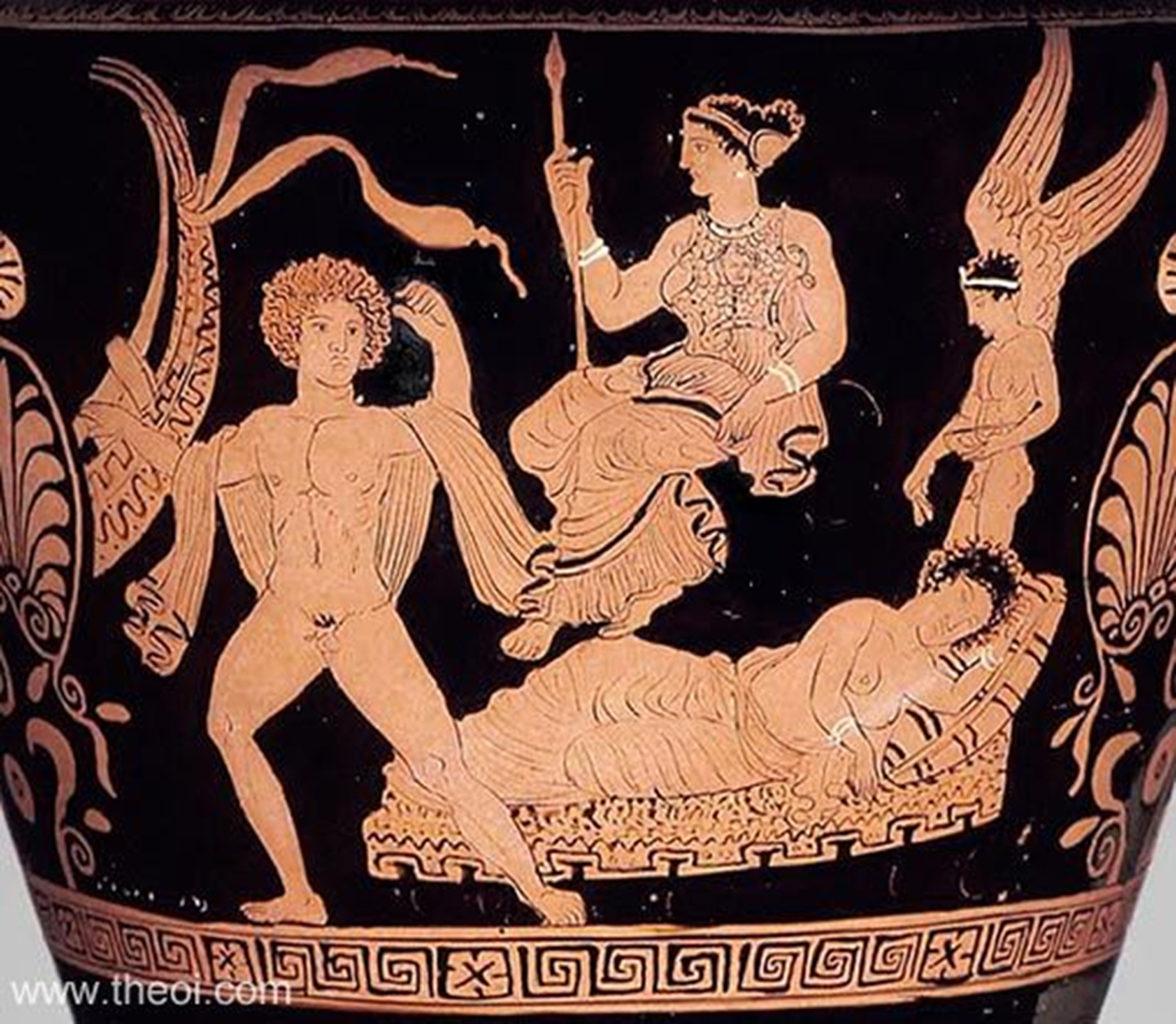

31. Theseus abandons Ariadne on Naxos (vase-painting). Theseus abandons the sleeping Ariadne on Naxos and steals away at night. (Point out the sleeping Ariadne in both vase-paintings; Theseus preparing to steal away and board his ship (left); the gods overseeing the action Athena (left) and Hermes (right); the god of sleep Hypnos (or Eros?) hovering over the sleeping Ariadne; point out the location of Crete, Naxos and Athens).

32. Theseus abandons Ariadne on Naxos (Angelica Kauffmann – painting). Ariadne awakes in the morning to find herself abandoned by Theseus. In her despair and bewilderment, she perhaps cursed Theseus as she saw his ship sailing away without her. (Point out Ariadne's despair as Theseus’ ship sails away in the distance (left); Ariadne turns away and cannot bear to look (left); Ariadne in shock and dismay (right) raises her arms in distress while a weeping Eros attends her.)

The sleeping Ariadne abandoned by Theseus on Naxos. (Point out Ariadne asleep; blissfully unaware that Theseus is abandoning her; Theseus’ ship leaving the harbour in the early dawn; the leopards - one prowling; one asleep under Ariadne's couch perhaps pointing to her future rescue by Dionysus the god)

33. Dionysus rescues Ariadne (Titian – painting). Dionysus, god of wine, drama and mystery-rites, comes to the rescue accompanied by his band of satyrs (half-human, woodland creatures), maenads (female followers) and other creatures. He rescues Ariadne and marries her. (Point out the youthful Dionysus (left) wreathed with vine-leaves; the satyrs – one wreathed with snakes (left); the maenads dancing with cymbals and tambourines (left); Ariadne on the shore perhaps pointing to the crown of stars which later ensured her immortality – the Corona Borealis (Northern Crown) based on the crown which Dionysus gave her; point out Dionysus finding the sleeping Ariadne (right) accompanied by Eros (god of love) with his bow and arrows; Dionysus (right) wreathed in vine leaves carries a thyrsus – his special wand with magical powers). Dionysus rescues Ariadne on Naxos. (Point out (left) Dionysus and a Cupid with Dionysus’ special wand – the thyrsus; Dionysus’ companions revelling in the background with musical instruments (tambourines); Dionysus’ left hand flinging a crown towards the heavens – a reference perhaps to the crown of stars which later ensured her immortality – the Corona Borealis (Northern Crown) based on the crown which Dionysus gave her; point out (right) Dionysus offers his hand to a weeping Ariadne; Cupid stands nearby with his bow and arrows; meanwhile Aphrodite (?) holds a crown above Ariadne's head – perhaps another allusion to the crown of stars which later ensured her immortality – the Corona Borealis (Northern Crown)).

34. Aegeus watches the ship return with black sails and throws himself into the sea in despair (illustration). Theseus forgets to change the dark funeral sails; so his father Aegeus, watching for his return, believes him dead and hurls himself into the sea from the Rock of the Acropolis or more probably from the rocky vantage point of Cape Sounion at the southernmost tip of Attica. (Point out dark funeral sails; the ship's eye – see slide 24; Aegeus watching for Theseus’ return from his vantage point (either the Acropolis or Cape Sounion; Acropolis (map); Cape Sounion).

35. Aegeus throws himself from the Acropolis according to the story (photo of the Acropolis). Aegeus, apparently, threw himself off the Acropolis to his death. (Point out that Aegeus threw himself into the sea which later became known as the Aegean Sea; impossible from the landlocked Acropolis!)

36. Aegeus may have thrown himself off the promontory at Sounion (photo and map). (Point out Cape Sounion at the southernmost tip of Attica with its temple to Poseidon (god of the sea) – an obvious vantage point for Aegeus to await Theseus’ return.)

37. Aegeus may have thrown himself off the promontory at Sounion (photo of Cape Sounion at sunset). Cape Sounion at sunset with its Temple of Poseidon (god of the sea) – a much more likely place for King Aegeus to keep a look out and hurl himself into the sea after seeing his son's ship return with the dark funeral sails. (Point out Cape Sounion and the Temple of Poseidon; Cape Sounion's position on the map; vase-paintings of Poseidon (god of the sea) with Poseidon and his trident astride a sea-horse (horse's head; sea-horse tail; squid decorations to represent the sea; Poseidon as a warrior-god with his trident).

38. Aegeus threw himself into the Aegean Sea named after him (illustration+map showing the Aegean Sea). Aegeus hurls himself into the sea which ever after was known as the Aegean Sea. (Point out Aegeus preparing to hurl himself into the sea on believing Theseus dead; the Aegean Sea (map) and islands).

39. Theseus became the great king of Athens revered in Greek Tragedy (photo of statue of Theseus). Theseus became the great king of Athens and was heralded as the king who unified the territory of Attica as one state with Athens as its capital. He also had other adventures: he was an Argonaut on Jason's expedition to win the Golden Fleece and was a generous friend to heroes such as Oedipus and Herakles. (Point out statue of Theseus in Athens with its inscription; Attica (map) with Athens as the capital). Theseus, however, will always be remembered for his most famous exploit: the daring journey into the heart of the Labyrinth and the killing of the Minotaur which gives us the expression to take the bull by the horns! (Point out central scene – the Minotaur; point out his other deeds on the periphery: the defeat of the villains Periphetes, Sinis, Sciron, Cercyon and Procrustes)

Postscript

If you have a go at putting together an assembly and delivering it, I am sure that you will enjoy it; more to the point, your pupils certainly will and will tell you so!