My introduction to Latin came at the hands of my prep school headmaster, now a little over 20 years ago. An unyielding authoritarian of the old school, he had by then owned and run his institution for 49 years as the unquestioned ruler of an educational empire. In spite of the Spartan conditions – ‘We've never gone in very much for “facilities” here,’ he once observed – and wildly eccentric characters, the school turned out scholars (and future classicists) at an impressive rate.

Through traditional instruction, peppered with the distribution of lines to unruly pupils, he cut an imposing figure. Though occasionally prone to violence – I was once manhandled for muddling up ora and oro, a distinction thereafter firmly etched into memory – he was an inspiring and effective teacher. Aged eight we began our route march through L. A. Wilding's Latin Course for Schools, as assorted Romans dug ditches, assailed ramparts and cast Gauls from cliffsides with bosses of shields.

Thanks to his tutelage and that of his successor, we were afforded the privilege of a rock solid foundation in Latin grammar, a gift for which I shall always remain profoundly grateful. It was in part as a result of these formative experiences that I decided to join the teaching profession myself. After I graduated and took up my first position, I knew I wanted to approach the language in a similarly rigorous fashion. I had seen first-hand the efficacy of a logically ordered, gradated approach. I was mindful too of my parents’ verdict on their experiences of learning Latin. Working their way through a modern course in the late 1970s, they both initially felt very confident in their command of the subject. When however they came to attempting an O level unseen translation, they found themselves wholly at sea, bereft of the grammatical know-how necessary for the job. I still recall my father, after he and I had trekked to London to purchase my copy of Wilding, thumbing the pages and remarking on how he wished he had learned from such a primer in his schooldays.

By the time I began teaching, Wilding's antiquated English – ‘whither’, ‘whence’, ‘whelm ye the barque in the sea’ etc. – proved too confusing to the contemporary student. Casting around for a modern equivalent, I was struck by the absence of anything which insisted on prose composition from the outset and stretched the brightest in quite the same way. By necessity, I created over time an array of exercises and worksheets to suit my purposes. Eventually I began collating them into a two-part primer which I intended to set at 13+ scholarship level, while including all materials required for Common Entrance and GCSE examinations and most of those needed at the old AS level examination. Part I would cover active verbs, all noun declensions, adjectives, basic pronouns and other rudimentary topics such as direct questions and prepositions. Part II would begin with the passive voice and culminate in gerunds, gerundives and the supine of purpose. The name Variatio meanwhile arose from the breadth of formats I attempted to include in the exercises: sentences, Latin to English and vice versa; unseens and proses; comprehensions; derivations and grammatical questions, including individual word analysis and formation as well as the parsing of verbs.

My key philosophy was that the pupil should be able to explain not only the meaning of a Latin sentence but why it means what it means. Many more recent textbooks begin with various characters and their locations in the home – not unreasonably, as plenty of modern language courses do the same. Yet even the simplest Latin sentence yields too many questions. A phrase like Marcus est in cubiculo can be intuitively rendered, but consider the points of confusion likely to occur to a brighter student. Why does cubiculo end in ‘o’, when the dictionary gives cubiculum? Why is est located mid-sentence, when the majority of verbs met later on are to be found at the end? How could one say that Marcus was in the bedroom, or will be tomorrow? I was determined that it be possible both to translate and to understand fully every sentence in Variatio using only the topics previously covered.

It is something of an intellectual challenge to create hundreds of sentences as well as a number of continuous proses with very limited grammar and vocabulary. The first 11 chapters of Variatio I took as long to write as the entirety of Variatio II. ‘Die’ in particular caused no end of trouble, with pereo and morior out of commission, and in places I had to comb Lewis and Short for rare uses of words or employ slightly hokey turns of phrase. (Livia, having poisoned her husband à la I, Claudius, announces somewhat floridly ‘Augustus breathes no more’.) For the most part, however, I hope that I succeeded in producing fluid prose in the early unseens.

After I had first produced a working draft of Variatio, I was quoted in The Spectator saying – perhaps more acerbically than I would have wished – ‘I can't remember a textbook that was really made better by a picture of a pot.’ I do stand by the principle, however. Naturally I approve wholeheartedly of showing students ancient art and architecture, endless possibilities for which are now at our fingertips with computer projectors in every classroom. Within the context of a language course, however, I feel it necessary to focus on the key linguistic information. I remembered once again my father's regret over the lack of clarity in his Latin education (as well as some truly dire French textbooks we had endured at school, every page positively heaving with colours, images and text boxes strewn around at jaunty angles.) My decision to employ an 11 x 8 inch format also stemmed from this desire to set out all that the pupil needs as clearly and concisely as possible.

I sought to include some humorous passages as light relief amid the military conquests. Hercule Poirot makes an appearance early in volume I, while the Terminator features in a late prose composition exercise in volume II. (‘Come with me if you want to live’ struck me as a decent example of a conditional clause.) Similarly I attempted to continue the long-held tradition in Classics books of producing the odd preposterously contrived sentence. Still, in comparison with other courses on the market Variatio could be construed by some as a little dry; inevitably it will not be to everyone's taste. In my view, however, the seeking out of ever more colourful resources can betray a lack of faith in the genuine power of our subject. Too much teaching today constitutes a kind of arms race, with teachers vying over who can produce the most glittering PowerPoint or some other extraordinary audio-visual experience. My suspicion is that our idea of ‘fun’ always retains for children a hint of the embarrassing parent dancing at a wedding. I never cease to be amazed at my Year 5 pupils who each September, embarking on Latin for the first time, derive simple joy from mastering amo and translating elementary verbs – just as I did two decades ago. Any teacher worth their salt seeks to enliven the proceedings, but often the purest enjoyment of the language is to be found in its gradual mastery. I created Variatio in the hope that I might aid in that noble endeavour and continue the work of those without whom I would never have been inspired in the pursuit of my own classical career.

This two-volume course offers a fast track to GCSE. It takes grammar seriously, concentrates on the essentials, and in its reading passages and background material gives an overview of Roman myth and history. It is endorsed by OCR for J282 Latin (9-1), but should also be useful for the Eduqas and IGCSE specifications, as well as for older students.

The format is closely modelled on John Taylor's Greek to GCSE (Bloomsbury, two volumes, revised edition 2016). Latin to GCSE is jointly authored: Henry Cullen is responsible for Part 1 and John Taylor for Part 2. Like the Greek course, it is based on experience of what students find difficult, concentrating on the explanation of principles in both accidence and syntax, to reduce the need for rote learning. So for example it is shown that the first and second declension endings met for nouns in Chapter 2 recur down the line for adjectives, pronouns and participles.

Latin to GCSE sticks closely to GCSE requirements, in the belief that timetable allocation for the subject in most schools makes multi-volume courses unwieldy. For the same reason, the focus is firmly on language: some background is provided, but less paralinguistic material than in other courses. Everything is explained, in the belief that candid treatment and clear description of grammar make for greater student confidence and a better overall experience. Reading passages involve only grammar already met, and their vocabulary likewise is either already familiar or is glossed. Nothing is left to osmosis, inference or guesswork. For this reason the book is also suitable for those working independently without a teacher.

Each chapter begins with new grammar (with plentiful examples), followed by manipulation exercises and Latin-English sentences. Continuous passages are provided from the earliest opportunity, and are kept to manageable length throughout. Passages adapted from ancient authors or based on iconic myths and historical events (from the origins of Rome to the early Empire) are preferred to invented stories about daily life.

English-Latin exercises are also provided throughout. These soon move beyond what is required for the very simple sentences now an option at GCSE (separate provision for which is made in both volumes). They are labelled ‘S&C’ (stretch and challenge) and can be omitted, though it is hoped that students will attempt at least some of them, as a valuable way to consolidate understanding.

Each chapter ends with a summary of the grammar covered, and a list of vocabulary met (typically about 45 words). These lists cumulatively amount to the 450 words of the OCR Defined Vocabulary. Within a chapter, GCSE words are underlined and glossed in blue when they first occur. There is a steady gradient both in the experience of grammar and in the acquisition of vocabulary.

Part 1 begins with some general description of the Latin language, and the principle of inflection. Chapter 1 covers the present tenses of porto and sum, and the nominative and accusative of first and second declension nouns. Chapter 2 has passages and background about the Trojan War, and introduces the remaining conjugations and cases. In Chapter 3 the focus is on the journey of Aeneas from Troy. New grammar includes the imperfect tense, possum, 2-1-2 adjectives, and the imperative. Chapter 4 continues the story of Aeneas, in Sicily and in Carthage, and brings in the perfect tense, third declension nouns, and personal pronouns. Chapter 5 brings Aeneas to the site of future Rome, and moves on to the story of Romulus and Remus. The future tense is introduced, along with third declension adjectives and more pronouns. Chapter 6 covers the early kings of Rome, and the birth of the Republic. Grammar coverage includes the pluperfect tense, relative clauses and the use of quod, quamquam, ubi and postquam, eo, and compound verbs. Thus by the end of Part 1 (which is self-contained, with its own reference section) students have met the main declensions and conjugations, and all the active tenses needed for GCSE. The learning vocabularies amount to 275 of the GCSE words.

The longer Part 2 begins in Chapter 7 with demonstrative pronouns, comparison of adjectives and adverbs, the passive (present, imperfect and future), and participles (present active and perfect passive). Passages and background cover the early days of the Republic and the development of social conflict. Chapter 8 brings in the perfect and pluperfect passive, simple conditional clauses, ipse and idem, the ablative absolute, and some irregular verbs. Reading material covers the expansion of Roman power in Italy, and the Gallic invasion. Chapter 9 introduces deponent and semi-deponent verbs, indirect statement, and some less common pronouns. The narrative focus here is Hannibal and his journey over the Alps to invade Italy. Chapter 10 deals with the imperfect subjunctive, purpose clauses, fourth and fifth declension nouns, indirect commands, result clauses, verbs of fearing,the pluperfect subjunctive, cum clauses, indirect questions, the connecting relative, and the gerundive. Background and passages deal with the career, achievements and assassination of Julius Caesar. Coverage of GCSE grammar and vocabulary is by this point complete.

Chapter 11 provides GCSE-level reading practice, with 20 revision passages about the Julio-Claudian emperors. Chapter 12 has 400 revision sentences (in sets of ten, each on a particular construction or grammar point). These are followed by details of the restricted grammar and vocabulary for GCSE English-Latin sentences, and ten exercises for these, then five complete practice GCSE Language papers. There is a comprehensive reference grammar covering the whole course, its layout aiming at maximum clarity and concentration on essentials. Six appendices summarise (1) use of cases, (2) constructions, (3) negatives, (4) uses of the subjunctive, (5) words easily confused, and (6) words with more than one meaning. Finally there is a glossary of grammar terms, English-Latin vocabulary, Latin-English vocabulary with grammar details, and an index.

Answer keys for both parts of the course are available from the Bloomsbury website (www.bloomsbury.com/uk), and additional exercises are being added. In case of difficulty please contact John Taylor ([email protected]). For extra GCSE-level reading practice the course can be used in tandem with Cullen, Dormandy and Taylor's Latin Stories (second edition, Bloomsbury 2017), which also has an answer key available.

It occurred to me some time ago that all the beginners’ textbooks in Classical Greek were stuck in the 1950s. While all other school subjects (including Latin) were supplied with colourful illustrated books produced on fine-quality paper, Greek books remained monochrome, containing slightly fuzzy images of vase paintings and ruins and lots of grim grammar. Some, like Athenaze and Reading Greek, contained good reading material but were pitched at committed undergraduates or adult learners, and were unappealing to young beginners. Another stimulus for me was the Australian Curriculum. Released in 2016, the Classical Languages FrameworkFootnote 1 provided learning sequences in Latin and Classical Greek for Years 7 to 10, for which I was one of the writing team. As with all courses in the Australian Curriculum, there were requirements that students of Classical Languages would also gain cross-disciplinary awareness and engage with Australian indigenous culture.

I spoke about some of these issues at a Celebration of GreekFootnote 2 function held in May 2016 at the University of Sydney, and when, as a result, a prominent member of Sydney's Greek community suggested sponsorship of an up-to-date, Australian textbook, I was very pleased to accept. Convinced that no commercial publisher would be interested in a book with such a potentially limited market, I was delighted that the generosity of the Greek donors was supplemented by another benefactor, and that the cost of quality printing and binding was underwritten by the Classical Languages Teachers AssociationFootnote 3, which became the official ‘publisher’.

It seemed essential to give this book a strong appeal to young people. I was very pleased, therefore, to have as my collaborators Emily Kerrison, an undergraduate student of Classics at the University of Sydney, and Alexander Anstey, a young artist of great promise, whose illustrations of Greek myths evoked instant admiration from the schoolchildren who saw them in draft form.

The framework for the course is provided by four fictitious young Australians, of various ethnic backgrounds (Anglo, Greek, Chinese and indigenous), who are completing tasks required to win a trip to Greece. Their dialogues, written by Emily Kerrison, provide an enjoyable storyline and allow the introduction of different perspectives on culture and language learning. ‘Shona’, an Aboriginal girl, tells stories from her ancestral culture that in some way parallel the Greek creation myths that comprise the first five chapters. The next four chapters offer the stories of constellations visible in the southern hemisphere, again with indigenous parallels. The final chapter focuses on the word Eureka!, presenting in Greek the story of Archimedes (with an explanation of his Principle), and progressing to the Eureka Stockade, an event in Australian history which is often cited as the beginning of democracy in this country. It is natural, from this, to explore the development of democracy in classical Greece, its expression through theatre and the tradition of drama that flourishes in our society today.

After some activities designed to introduce and practise the alphabet, the Greek language is introduced through a cartoon strip presentation of the creation myths. Initially the story is told in English, with some Greek words and phrases inserted in the pictures, but by the third chapter the narrative is entirely in Greek. Vocabulary lists accompany each story, reinforced by exercises in English derivatives, called Wordworks. From the sixth chapter the stories are narrated in Greek without the support of the cartoon strips. The general approach is that of the reading method, encouraging the student to deduce and infer meaning from the context and the illustrations before the grammar is formally explained.

The Greek language content in Eureka! is kept at a basic level, but is nonetheless real and structured. It includes the definite article, all cases in three declensions of nouns, the present indicative active of verbs, and enough vocabulary to supply the stories. The quality of the Greek in the narratives is somewhat compromised by the grammatical limitations, but I have consciously avoided introducing forms, such as middle verbs, that would have to be glossed. There are a few puzzles designed to reinforce the learning of vocabulary.

The contributions of the ancient Greek world to modern life are illustrated throughout the book with images in full colour, inviting discussion about similarities and differences. Mythological scenes on Greek vases offer the chance to discuss archaeological findings and classical pottery. Famous Greek sites and literary figures are introduced as opportunities for student research. The lively dialogues among the teenage characters are designed to be read aloud in class to stimulate discussions and to alert students to connections with other disciplines.

The inclusion of Aboriginal stories and artworks demonstrates interesting parallels in human thinking and engenders respect for Australia's own ancient heritage. Students should be led to reflect on the different cultural streams that have nourished a flourishing society such as that of modern Australia (or Britain, or the USA, etc.) Episodes from more recent Australian history are included in the last two chapters to emphasise the continuing links between the ancient Greek world and Australian society today.

I am conscious that the structure of Eureka! may be confronting to some Classics teachers, who will want to gloss over the cultural content and push on with the language acquisition. This book does not move quickly through the structures of the Greek language. It is deliberately introductory only, designed to be used for about half a year in a timetabled class, and for a full year in an informal arrangement, such as a Greek Club.

It is my own belief that Classical Greek needs to be validated in the minds of young students as a body of knowledge that is relevant to many other facets of life and to many other subjects in the school curriculum. Convinced of this, they are more likely to pursue the study of the language as it becomes more complex, and to have a context in which the reading of authentic Greek literature is a richer and more meaningful experience.

It is very encouraging to see the enthusiasm with which Greek is embraced by students of diverse backgrounds once they see and understand the many connections with the English language and the traditions they are familiar with in their everyday lives. I hope that, for Australian students, geographically distant from Europe, Eureka! will help them to recognise their debt to antiquity, both the traditions common to Western cultures and those which are special to this most ancient of continents.

The accompanying Teacher's Manual contains translations of all the Greek texts, some pedagogical tips, suggestions for discussion and research topics, some resource material and three assessment tasks. A soft copy of the Teacher's Manual is available free with orders of five or more textbooks. It is my intention to update the Teacher's Manual as new ideas and resources occur, and the latest edition contains a list of corrections (mainly Greek accents) that I was not able to insert in the textbook before the final printing.

Eureka! can be ordered online from www.cltainc.org at the cost of A$35 for the textbook and A$15 for the Teacher's Manual, plus postage.

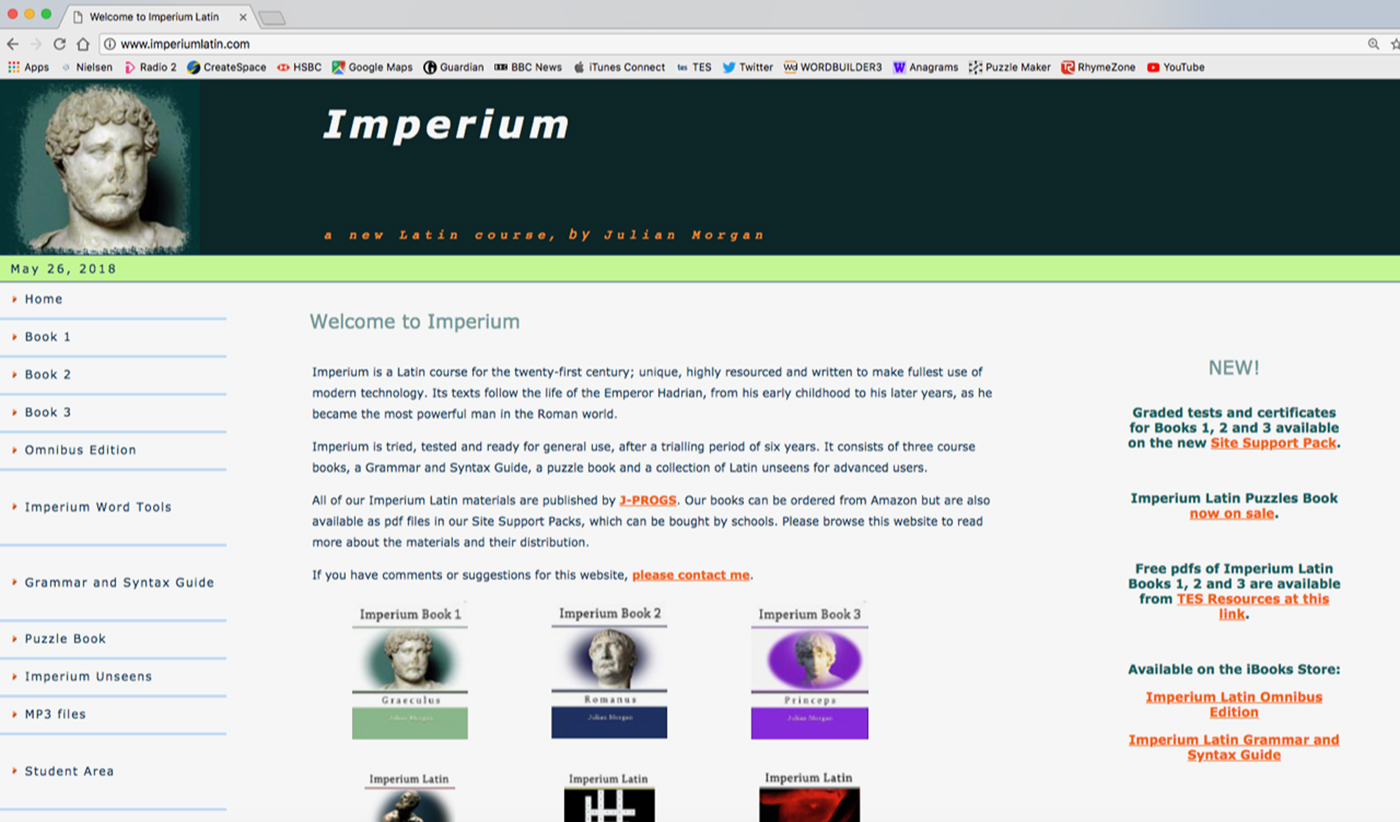

It was under a grey sky in Spring 2007 that I made my way to the drab Whitehall building. Feeling like an unnamed John le Carré walk-on, I entered the Department for Education's looming portals, faced the music and … got the job. Though I did not know it at the time, it was the beginning of a process which would lead to the realisation of the Imperium Latin Course.

My new employment was a seconded post to the European School in Karlsruhe, Germany. This was very exciting and a time of real opportunity: I had been a Classics teacher for more than 20 years and was confident in trying out new methods and ideas. I had also been a software developer and my habit of using screen-based technologies in the classroom was something I knew I would want to develop in my new job. As I considered my options for course books over the next few months, I experienced a growing feeling that perhaps now was my time to start with a blank sheet of paper and do the whole lot my own way for the first time. I had taught the Cambridge Latin Course and the Oxford Latin Course, for the second of which I had even been a senior adviser during the creation of the second edition in the late 1990s. I was familiar with a number of other published Latin courses at the time and although I thought some of them good, the feeling I might create something better was gnawing at me in the run up to leaving the UK. Only when I visited the school in Germany for the first time did I actually voice my thoughts about writing my own Latin course, to be met by enthusiastic responses from my new students and headteacher alike.

It was when the new school year of 2007 arrived that I began to translate concepts into reality. Each lesson with the beginners’ class had to have new materials written for it and I knew this would be a three-year commitment at least. Since there was no physical book and nothing ahead of me except my sketches and plans, I had to print out papers with new content for the students: it was a demanding time, to say the least. Pictures, texts in Latin and English, exercises, jokes, links to websites; all had to be identified and written down. I had been a strong advocate of respecting copyright and now, I had to follow procedures I knew to be correct, meaning that I could recycle very little and steal absolutely nothing in the course of assembling resources. I loved it - all of it - and each challenge to be met was one for me in my element.

Figure 1. | The fun begins.

It is a great joy to start from a blank sheet when you have been using other people's materials for as long as I had then. We all know that there are faults in the course materials we use: whether the books are too dull, too long, too complicated, too cheerless or sometimes just plain wrong. So when we write our own, we try to avoid the pitfalls which befell the others before us and maybe, just maybe, we get to create something better, even if that only means better for ourselves in our own classrooms. In my case I made some arbitrary decisions about my Latin course very early on, most of which I managed to keep to during the rest of the creative process. I decided I would have 30 chapters in three books, always include English into Latin in every chapter, and always have a background section, which would account for around 20% or so of the total course content. I would implement a system I came to call sine qua non, which meant that at every chapter end, the content which had to be learned would be clearly identified and tested. This process focused a lot on vocabulary but also included syntax and grammar where I felt it would be needed.

Figure 2. | SQN 1.

The first class of 16 students to use Imperium was in Year 3 (Year 9 in the UK system, aged 13) and it became clear early on that they were not just keen but also bright. Their quick learning and high standards undoubtedly brought their own effect to the development of Imperium as I found I had no need to make things especially simple. Sometimes the books are criticised for being a bit too rigorous but I do not think this is necessarily a bad thing in a world where everything has been simplified in comparison to what once went before. In fact, Imperium does aim to be traditional (even old-fashioned) in its approach, though that hardship should be softened by liberal amounts of modern technology thrown into the mix.

The thing about blank sheets is that you have to put something down on them and I soon found it best to have one piece of paper for each of the 30 chapters I was designing. Then came the toughest of all choices - the mons altissimus of creating a new Latin course, namely, what goes where? That is, what will the story content be (assuming it is going to be a reading course or a variant on that theme) and then, which linguistic elements are to go in where? As I did this, I remembered some standout moments from my teaching. There was the one when an incredibly gifted Year 11 student had told me he wanted to stop doing Latin because he could not understand Indirect Statement. That image demanded that this ghastly challenge should be kept back until somewhere near the end of Book 3 as I did not want to lose good students for whom Latin might seem too hard too soon. There were memories of students who had passed their GCSEs but then did not seem to know anything at all about grammar or syntax when they started their A level course. Oh yes, far too many of those! There were cruel memories of what Participles had done to whole classes of students and how the Ablative Absolute had all but killed the subject off for kids who had once been eager but now felt excluded from understanding what was going on in a given text. As I pondered my content sequencing, shades from more than 20 years of teaching passed in front of me and I vowed not to ignore these spectres. Instead I held things back in the process so that the trickiest steps would come later on, when options times for examination entries had all passed and the students would be far enough on to withstand a bit of a battering in the cause of becoming proper Latin students.

The story the course would tell was immediately obvious to me as I had written a book about Hadrian a few years before and I knew he was a fascinating figure. He had links to countries right across the Roman world - a very useful thing when you are teaching in a European School. Not only that, he had loads of different talents and abilities and lived in one of the most interesting of all times in the Roman Empire. He came from a slightly dysfunctional family which would make things interesting and his unusual sexual history was a story I thought could be told and one which might shed light on events today. There was never any doubt that Hadrian would become the central character and it seemed that if I had 30 chapters to go at, I could make a reasonable shot at going from birth to death. In this I was perhaps influenced by Horace's pivotal role in the Oxford Latin Course, which I always thought to have been one its most successful concepts.

Once my 30 pages lay in front of me on a table, I began to map out the points of the story and the grammatical framework of the course. Here came what may have been my most inspired but perhaps also most controversial decision. As someone who had once learned Dutch with no schooling, I had realised by my own analysis how little most tenses need to be used except for the present. I had also had experience from working with the CIRCE Project of preparing myself to go and give talks in Italy and France and other countries, where I saw the same thing happening. It seemed to me that if you can master the present tense in a foreign language early on, you can do without the future almost entirely and that perhaps even past tenses are not as important as I had always thought. It kept coming back that if I could stick to the present tense for as long as possible, I would avoid the crisis which inevitably hits students of the Cambridge Latin Course when they get to Stage 6 and meet the Imperfect and Perfect tenses at the same time. I also began to think that this crisis is in fact a crisis of its own making, not necessarily reflected in content which has to be learned so early on during the process. (That this was backed up by later research on Martial's poems is something I shall mention again shortly.) For the time being, I made the decision that I should use the present tense only (except in a few unavoidable, glossed examples) all the way from Chapters 1 to 23. Only then would I introduce the remaining tenses, leading to a full, extremely nasty but also complete test of all verb forms in Chapter 26, paving the way for the real syntactical nasties mentioned above to be shoehorned into the last few chapters. It is a framework which is now established and well-proven, though I am quite familiar with the cries of shock and horror made by those to whom the process is strange. The basic linguistic content is laid out below.

Figure 3. | Chapter 30 Extract.

Book 1

• All cases of nouns and adjectives in declensions 1 to 3 are used.

• Verbs are used in the present active indicative, from conjugations 1 to 4.

Book 2

• Nouns are used from declensions 1 to 5, with all major pronouns.

• Adjectives and adverbs are given in different stages of comparison.

• Verbs are used in the present tense, active and passive, indicative and subjunctive, from conjugations 1 to 4.

Book 3

• The full tense systems in Latin, presenting first the primary tenses and then the historic ones.

• Participles and complex structures such as conditional clauses and indirect statement feature towards the end of the book.

It was during those early design sessions that something else sprang out which is absent in most Latin courses, though I make an exception here for Nick Oulton's materials for his course So You Really Want To Learn Latin. This is humour, which I knew had to be an integral part of my process. When a subject is difficult you have to sweeten the pill and if laughter can help, let us chuckle a bit and titter together. I knew that I would want to use real Roman humour in Book 3 - and where better to start looking than in Martial's poems? - but this meant I might want to build a part into the course for jokes when the language was of necessity more simple. The answer I found was to include what became known as Moral Messages in books 1 and 2 of the course, which then became Martial's Messages in Book 3. The Moral Messages in particular elicit frequent groans but help keep some jollity in the room. The Martial epigrams were selected to match the syntactical and grammatical content of the course in and up to the chapter in question: this was a demanding chore as it involved reading every single poem written by Martial and determining whether it could or should be used at an appropriate point. Would it be funny enough? Did it use known language structures? Did it add something unique? Was it too rude? This is one aspect of Book 3 which sets it apart from other courses and one with which I am particularly happy. I should also add that most of Martial's poetry appeared to me to have been written in the present tense, giving an unexpected validation to my earlier decision on sequencing.

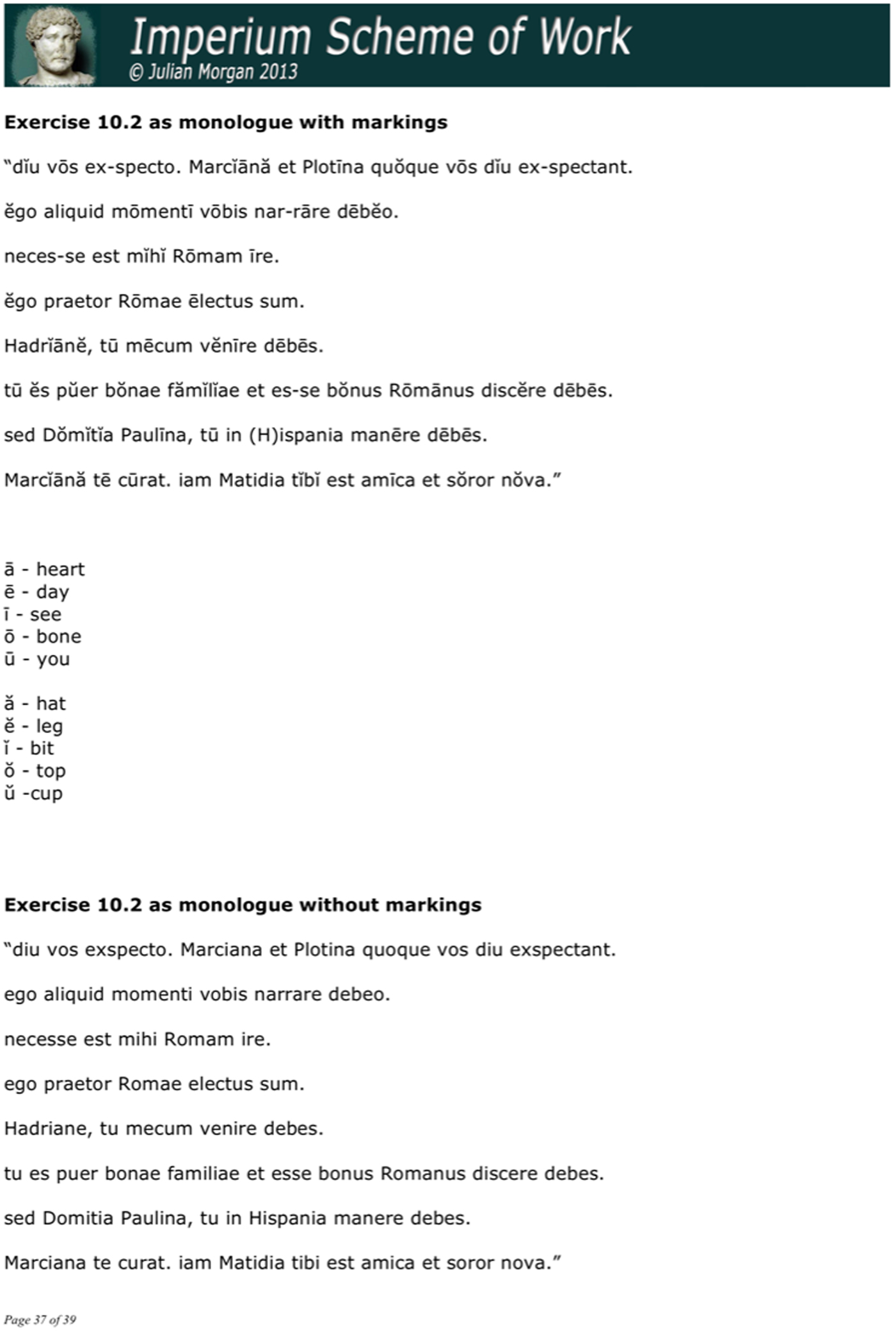

Good presentation is key these days and two factors played a role here. The first resulted in a system which pervades the course throughout, which is my one-page rule. That is to say, no exercise ever spills onto a second page, which ensures that long passages are completely avoided. Not only that: the exercises are put into a box-based system, so students write their translation onto boxes on the page of the book, or onto the freely downloadable rough worksheets if they wish. The second factor was whether I should use macrons or not. There are arguments on both sides and the issue can be divisive amongst classicists. I opted not to do so, as so many children ignore them anyway and even when they have had them explained multiple times, seem to have not the vaguest recollection what they signify when it is time to do something about them. Instead, I opted to talk about syllable length and use long syllable markings only at two points where there are dialogues which can be employed in different ways during the course. The dialogues are located at the ends of Book 1 and Book 2 and draw special attention to issues of pronunciation and sounding natural.

Figure 4. | Hadrian's legacy.

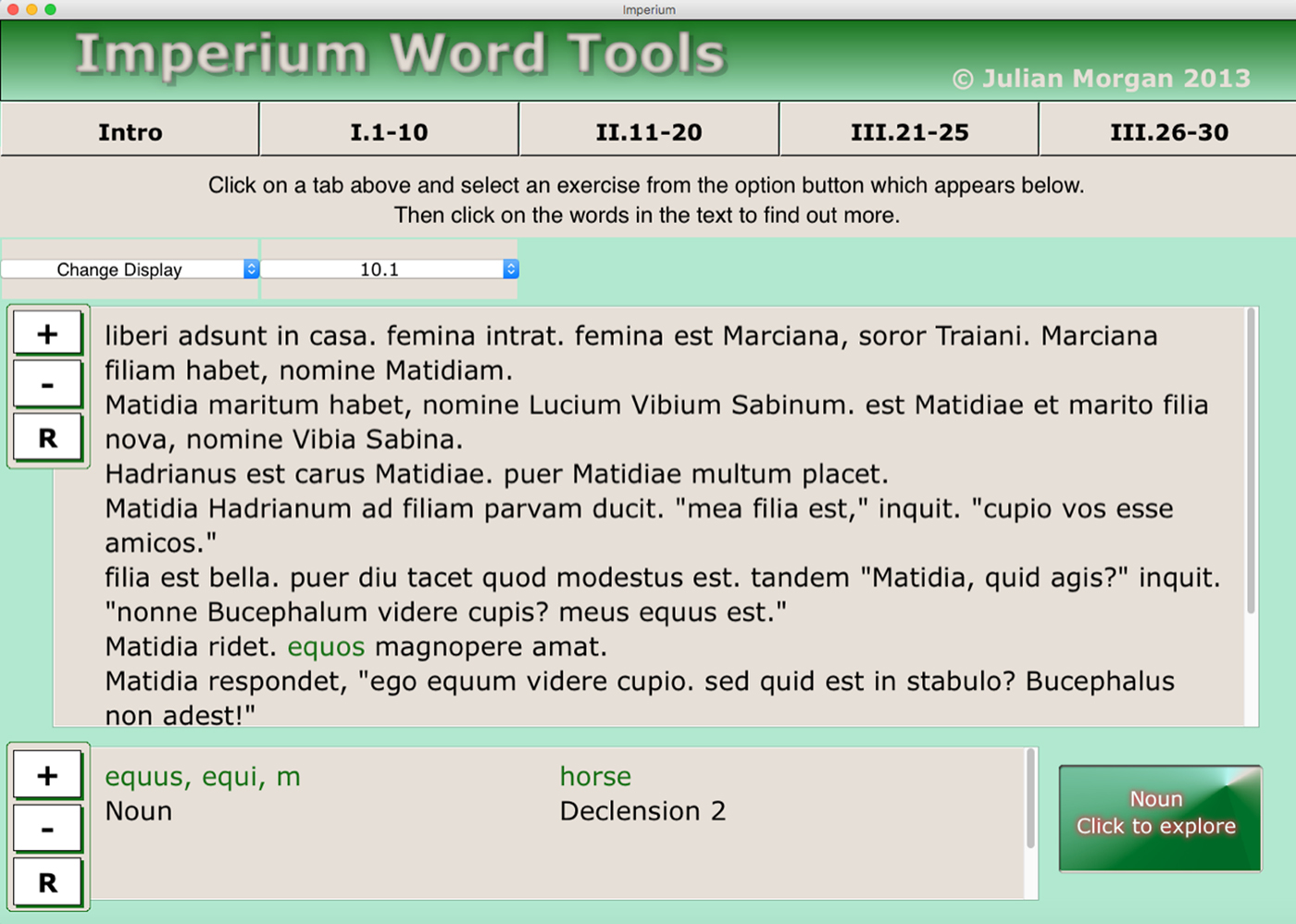

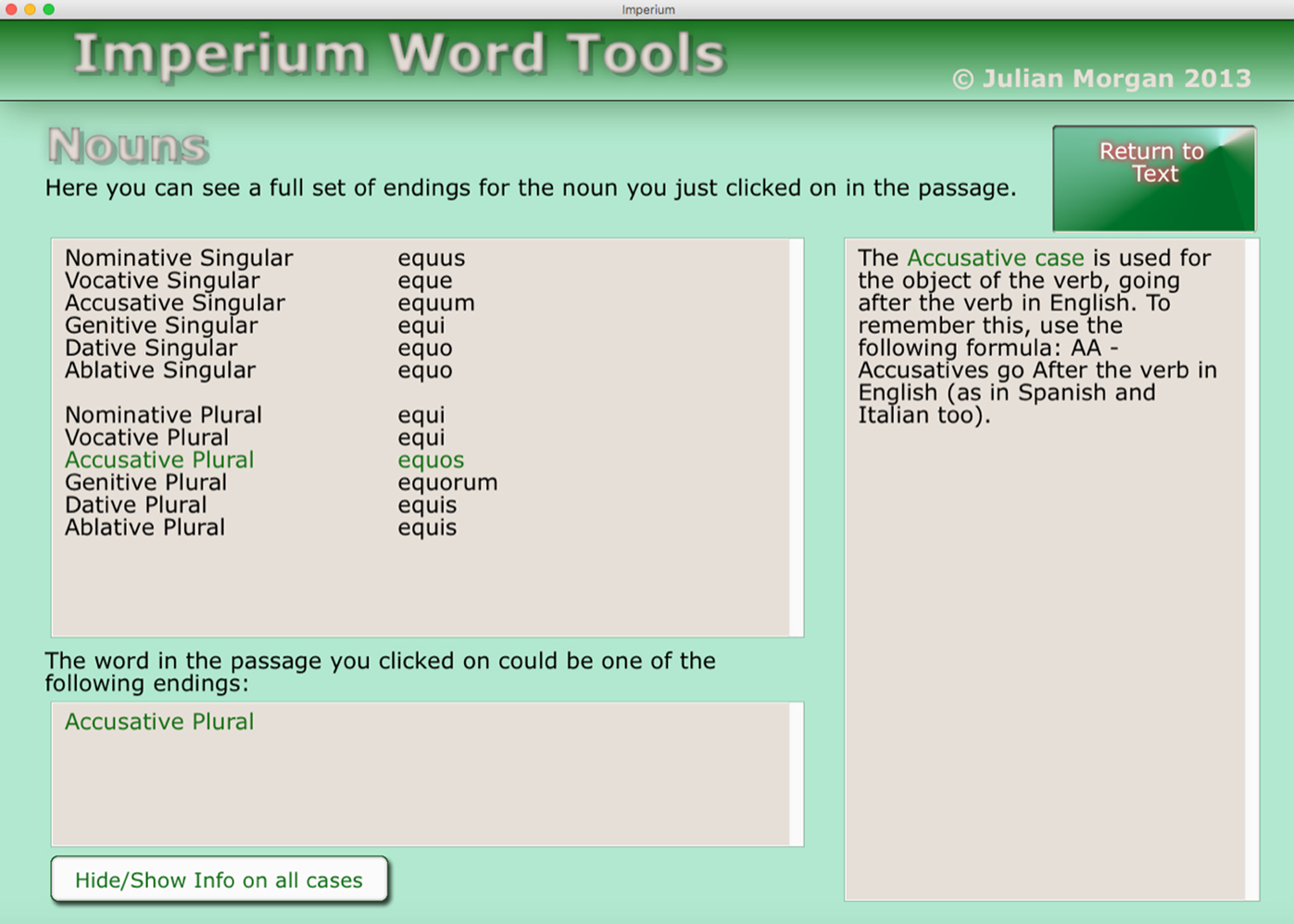

After three years of solid writing, the course existed as I thought I wanted it to be. That is, the books were written and I could publish them as print on demand titles through Amazon. It became clear immediately that my students preferred books to piles of scrappy paper in binders and the whole thing started to become more conventional in its transmission. I realised that it would be helpful to collate all the grammar and syntax into a fourth book, as students were struggling at the time to find bits of information spread across three text books, so the fourth book in the course came into being. Now was the time to write the Imperium Word Tools app, which took more than 12 months to complete, in what became perhaps the most ambitious project so far. Having used Perseus and websites such as nodictionaries.com for several years, I knew I wanted to have a hypertext system which would allow every exercise of the course to be viewed on screen with full information about every word. I did not want to provide a set of answers to the problems but rather a toolkit to enable students to reach out for right answers by a process of machine-encouraged analysis. In almost every case to date I had found other systems inadequate in some way or other and I wanted to avoid their failings, such as excessive use of abbreviations, density, too many unclear options, oversimplification or basic inaccuracy. Imperium Word Tools was a complex piece of software to write but it sought be the most advanced textual analysis software available at the time for the teaching of Latin and I hoped it would be used as an indispensable part of the teacher's presentation from about Chapter 8 right up to the end of the course.

Figure 5. | Martial's Messages 27.

After about five years’ of work, Imperium Latin had all of its major components intact. Now the job was to prepare it for others to use. This led to the development of the website, the creation of extra free-of-charge resources for students (practice tests for every chapter, rough work sheets) as well as what became known as the Site Support Pack for teachers. This includes the right to print any of the four books as well as a full set of answers for every exercise, a site licence to install the Imperium Word Tools app on a PC, Mac or Linux network, a full set of the images used in the course, and full teaching notes. The Site Support Pack was written in the knowledge that there are non-specialist teachers of Latin who can benefit from the help of someone who has been in the game for a longer time. The price of the Site Support Pack was fixed at £50, which was seen as enough to deter students from making a casual purchase and then suddenly having access to all the right answers, but not too much to put it beyond the reach of most departments or even individual tutors. In addition to these resources, an Imperium puzzle book was written as well as an unseens book and its accompanying Imperium Unseen Tools app for older students. To make the thing more complete for schools where iPads are used extensively, I created an electronic version of the whole course (Books 1, 2 and 3) to be available on the iBooks Store.

Motivation is a key factor for all Classics teachers these days as threats to our continued existence seem to fly at us from all corners. In this regard Imperium may have some special barbs to cast back at the foe. First of all, it is written with proper awareness of recent social and technological developments. In case this is unclear, let the question be posed, why might a diet of Latin not appeal to an audience of kids today? Perhaps it is the difficulty of the subject, where systems have to be learned which do not always seem clear to the end user? I believe quite firmly that we should never ask a student to learn one piece of information, eg sanguis means ‘blood’, and then change the rules later on by saying that actually, it is sanguis, sanguinem which means ‘blood’ and then later go on to say that it is sanguis, sanguinis, m which means ‘blood’. Is this helpful to anyone, let alone a bewildered 13 year old? Yet it is exactly what the market-leading course does. We could do the same with ducit, meaning ‘leads, takes’: duxit, later given as duco, ducere duxi meaning ‘lead, take’ and later still having duco, ducere duxi ductus meaning ‘lead, take’. The Imperium Latin Course never adopts this approach but from Chapter 1 onwards, only full systems appear in vocabulary listings and nothing is ever included in a list of things to be learned unless it is a full system. That means, for example, that no real testing of nouns or pronouns is carried out until all the cases have been introduced.

There are other factors affecting children today, among which surely the most prominent must be a lack of time. Time is crucial for study and if students struggle to find it, then they will find it hard to love a subject which demands it by the bucketful. They also want to watch normal TV, catch-up TV, go to the cinema, meet friends on social media and spend time in their hobbies and sporting pleasures: one thing they are not short of is distractions. It was always a consideration during the creation of Imperium that I wanted to write the shortest meaningful course on the market today, reducing word counts down as far as I dared. When I came to analyse the Cambridge Latin Course, I found that it consists of over 30,000 words of Latin, not including the linguistic practice exercises. Is it any wonder that every teacher of the course you meet complains about not having time to teach it? Yet there are other courses out there just as long or even longer, particularly if you look at some of the German language ones. Those folks really do know how to write long books! It struck me then, as it strikes me now, that this poses a real threat to the future of twenty-first century studies in Latin. In contrast, I managed to create the whole of the Imperium Latin using about 9,000 words of Latin, including every linguistic exercise in the course. When counting headwords in the vocabulary lists too, I noted around 3,000 in the Cambridge Latin Course, compared with just short of 1,400 in Imperium. Some may then raise the objection that Imperium might not expose its students to enough linguistic content but I counter this by pointing to success rates in examinations, where it was clear the Imperium students faced no disadvantage whatsoever and reached top grades as a matter of course. I cannot call on huge numbers of samples in the survey to back this up but I can and do claim that the evidence was conclusive, given that several Imperium students went on to get the highest grades at Baccalaureate level and were obviously in no way disadvantaged.

Figure 6. | Dialogue Ex 10.2.

Figure 7. | Imperium Word Tools Noun lookup.

Clear, funny and short? That gang of three may be enough but what of the fourth? Cheap. During my years working for the Department for Education in Karlsruhe, I was well paid and left alone to do my job in a way which would turn most teachers in British schools green with envy. Trusted to teach the kids, I was also trusted to create my own materials, without which confidence there would never have been an Imperium course. When this work was ready for the market, it did not seem necessary to charge a lot of money for it, so in the end I decided to release the entire texts of Books 1, 2 and 3 free of charge, as pdf downloads on the Times Educational Resources webpage. At the time of writing this article there have been over 1,100 downloads made of Book 1 and about 400 each of Books 2 and 3. This is in addition to the downloads (not numbered) made from the Classics Library, where the three books are also held. Thinking about it, I may be the only person around who has given away two thousand Latin books (and rising).

If your interest levels have been activated by reading this, please allow me to encourage you to join in, at least by making the free-of-charge downloads. (You can find the links from the main website address below.) Then, if you like Imperium, please leave a comment behind where you downloaded it, or send me an email to let me know what you think. There are some things you should consider alongside this, perhaps. First off, the Imperium course was designed to be taught using a computer screen in the classroom for pretty much every lesson taught. It was also designed to be taught in a lively way, allowing for movement in the classroom and lots of interaction. It was created for students starting out in about Year 9 (UK system) and it should be possible to teach it from start to finish in less than two years. It is fairly uncompromising in content and is aimed at bright students, which may make it difficult in a school where the tail end is longer. It is entirely suitable for catch-up students, self-learners, adults or for those working at their own pace, although for these the deployment of extra resources is to be recommended highly. That last point is worth labouring, I feel. Without the app, the mp3 files, the practice tests, the pictures and all the materials in the Site Support Pack, the end user would lose out badly and forego a significant amount of the potential advantage. The Imperium course should be seen as the sum of its parts: the free-of-charge downloads are just three parts of the complete set.

Figure 8. | Imperium Word Tools Analysis.

Figure 9. | Website Index.

Figure 10. | TES Resources.

Figure 11. | Site Support Pack.

If you are reading this article and would like to know more, I should be delighted to respond to any enquiries about Imperium. Please email me: [email protected]

There are lots more things you can find out about the course on the website: www.imperiumlatin.com

A number of new Latin and Greek course books have recently been published. The Editor invited the authors to write a little about the rationale for and design of their books and present them direct to their audiences.

The first Telling Tales in Latin book was written mostly during 2012, in the course of a year-long pilot with 10 and 11 year olds from Pegasus primary school on the Blackbird Leys estate in Oxford. This pilot was generously funded by the grant-giving charity Classics for All.

The second Telling Tales in Latin book, Distant Lands, was written during 2015, while teaching a group of effervescent 13 and 14 year old students at Cheney School in Oxford, a large state comprehensive school where my charity The Iris Project runs a Community Classics Centre. I was running a classics enrichment course for this group of students, and introducing them to the story of Ovid's exile inspired me to start to write a second book in the series, this time rooted in a journey and a historical framework. I knew that this would inevitably imbue the stories with a more melancholy edge, but I hoped that the readers would be carried along by Ovid's playful tone and magical stories, as well as feeling moved by the sadness of his own biographical tale.

It is of course for the readers to decide if this has worked! I hope very much that both books will be read and enjoyed by many readers of all ages.

Early seeds

The seeds of these two books were planted in my early childhood, as this is where, like many, I learned all about the thrill of telling tales! I grew up with an older brother and younger sister. Between the three of us, we soon learned to tell stories of surprise, wonder and terror which kept us entertained for those long school holidays and weekends. Wherever we went, we would always be making up stories to excite and frighten one another, and the worlds we conjured up have never left me.

Like many children, I learned about the myths of the Greeks and Romans long before I learned any Latin; in fact, when I did first learn Latin, it was alongside descriptions of ancient Rome, slaves and masters, with country villas. I remember as a teenager feeling a sense of disappointment that the dark and colourful stories I'd long known did not seem to connect at all to these remote characters who spoke Latin in the text book we used.

I toyed with the idea of creating a fiction-based Latin course for some years, and once, many, many years ago, started one which involved a girl waking up in a fantasy world where everyone spoke Latin, and she had to work out the language to find her way home! Nothing ever came of that half-completed course, but the desire to create a book which would introduce Latin using imagination, games and storytelling remained.

I became a doctoral student in 2001 and chose to study Ovid's Metamorphoses, exploring how his narrative style is similar to that of the magical realist movement. It therefore seemed entirely natural to me that when I started teaching Latin as part of a pilot in a school in Hackney in 2006, I would use these stories as the springboard. It took another six years for me to actually sit down and turn the ideas, notes and lesson plans into a book.

Why Metamorphoses?

For me, there is no piece of literature I have encountered which has been more imaginative, colourful, mysterious, winding, dark and thoroughly entertaining as Ovid's epic poem. As he declares in his prologue, this book is to tell the history of the world through a fabric of interconnected, magical stories. This in itself carries a suggestive and counter-cultural note; the flamboyant, irreverent, touching and tragic flurry of tales which follow confirms that Ovid's ‘grand’ poem intends in fact to tease and mock the grandeur of epic poems. It also, though, on a more serious note, tells the stories of the ‘smaller’ characters and seems to emphasise the everyday passions of people from all walks of life, and celebrate and commiserate with them. It was this spirit of empathy, and this focus on the unexpected, which inspired me to think it could create an appealing framework for a Latin course.

So I could think of no better place to choose my stories, no better poem to use to introduce Latin than Ovid's poem and no better narrator than Ovid himself, the eloquent, poetic, imaginative, comic tale-teller who in the end came to a miserable end through his own talent.

Intentions

Telling Tales in Latin and Distant Lands are both intended to be storybooks which happen to also include learning Latin, and the size, illustrations, and content have all been designed around that central idea. A consequence of this driving concept has been several decisions I took early on which have caused the books to diverge from courses which introduce Latin.

I minimised the more obviously text-book aspects such as practice sentences and exercises as much as possible, and focused instead on the flow of the stories. I chose to have Ovid as an exclusive narrator, as I hoped his chatty persona would act as a comforting and entertaining guide through the stories, and also through the grammar.

In his dialogue, I did not avoid using English words which might seem hard for younger children. I wanted the books to be a discovery of English and Latin words, so it was important to me to remain true to this by including the richness of English vocabulary. The storytelling seemed to me to require interesting vocabulary to give it colour and energy.

Finally, the activities section is written to look and feel like a book rather than a textbook, so it isn't necessarily a list of activities to follow in rounded bullet point suggestions, but a more meandering set of ideas.

These features, I hope, help to create storybooks with all that I would like that to entail; but inevitably, they bring with them challenges. I have written a guide to the first Telling Tales in Latin book, which is available to be downloaded for free from the Iris Project website. The aim of this guide is to detail the challenges I found when delivering the book to my class and the things I did to work around these. I have gone through chapter by chapter, providing translations, and explaining in each one the thinking behind the story I chose, and the way it is told.

I hope this has provided some helpful insight into the thoughts and intentions behind both Telling Tales in Latin books.

There is now also Telling Tales in Greek which introduces the ancient language through the stories of Homer, and with the wily Odysseus narrating some favourite scenes, from the quarrel on the beach, to the mysterious Circe in her woods!