Introduction

The lessons planned in this essay were designed for a group of Year 7 students in an independent girls’ school in London. Their course of study for Classics in Year 7 was a general introduction, involving beginners’ Greek and the rudiments of Latin, but largely focused on learning about Greek mythology, Homeric epic and Roman culture. Wright's Greeks & Romans textbook was often used in class, but the content was chosen and materials designed by the class teacher. I began teaching this class just as they were finishing Greek mythology and beginning to study the Iliad and Odyssey. The sequence of four lessons, based around the Underworld was intended to provide a re-cap of the Homeric material after they had studied the two epics, as well as exploring in further detail episodes which I had skipped over for the sake of brevity in the previous sequence, such as the Odyssey's katabasis. It also looked forward to studying Roman material in the next module by introducing the Aeneid in translation.

This research question stems from looking at a group of Year 7s’ work during the course of their introductory module to Classical Civilisation, in particular their creative responses to certain myths. While many students were capable of producing nuanced responses when asked to re-tell, for example, the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur in a contemporary setting, others struggled to walk the line between regurgitating a shortened version of the myth and veering entirely from the original. For this age group, creative writing tasks seem a valuable way of checking understanding of narratives, but simply asking them to re-tell a myth, and giving students no notion of how others have approached re-telling myths, seems to neglect a potentially valuable dimension of these kinds of task. Aside from simply checking understanding, creative writing tasks can be used to encourage numerous other skills (Tompkins, Reference Tompkins1982), some of which will be more relevant to certain age groups and within certain subjects than others. Given that creative writing tasks were ubiquitous in the schemes of work followed, it seemed worthwhile to equip students with the skills to engage with these at a higher level.

To this end, I decided to exploit the potential of classical reception studies in allowing students to take their role as receivers of a classical tradition seriously. By shifting the focus away from creative writing as simply checking understanding, the aim was to encourage the development of skills associated with creativity in this subject, including developing students’ meta-cognitive understanding of creative processes. This aim seemed expedient given a current interest in and increased awareness of the value of creative writing in a number of subjects, for both students and teachers: others have noted gaps in research (Anae, Reference Anae2014, p.127), and reported on the successes and limitation of schemes encouraging creative writing in education (Millard et al., Reference Millard, Menzies, Baars and Bernardes2019).

Literature review

Firstly, this section reviews existing approaches towards the teaching of classical reception, including its use as a pedagogical tool for teaching classical literature. Unlike previous research into the potential of classical reception studies in the senior school curriculum, it considers the ways in which reception studies per se can act as a component in Classics curricula which involves both intellectual and creative mastery of the subject. This combination, of academic and creative achievement, is inherent not only in examples of high-quality classical reception, but also in the theory and scholarship surrounding the discipline. Secondly, it considers the potential of classical reception studies to cultivate high-level creative skills among students, including intellectual self-awareness and the ability to reconcile ambiguities, within the context of current research on the definition and assessment of creativity among school students.

What are the potentialities of classical reception studies in a secondary school classroom?

Recognition of the potential of reception studies to enhance school-age students’ engagement with the ancient world is nascent, and case-studies are limited at present. However, a turn towards reception as a potential pedagogical tool has occurred alongside reception studies’ rise to an important place within the nexus of subjects termed ‘Classics’. Forde (Reference Forde2019) has identified the potential role of classical reception in sharpening (both in the sense of clarifying and heightening) students’ responses to the Odyssey in translation in order to improve performance in the OCR A level in Classical Civilisation. Reception studies is used in this instance to provoke students’ interest in the texts before confronting them with scholarship (Forde, Reference Forde2019, p. 19) and to achieve assessment objectives demanded by exam boards. However, in this essay I examine how pupils might engage with classical reception minus the strictures of an exam syllabus, and whether reception studies can be meaningfully taught at a Key Stage 3 level with its own specific set of learning objectives, rather than subordinated to objectives conditioned by preparation for mainstream examinations.

At any level of education, reception studies have occupied a shifting, negotiable place in relation to more ‘traditional’ Classics curricula. Debates are rife over what content and approaches are suitable within the discipline. Some have reacted against the ancillary role which the subject has played in university education thus far by pointing out its centrality and inseparability from the study of Classics as a whole (Martindale, Reference Martindale2013, pp.175–77). However, attempts to locate the unique features of classical reception (see, for example, Billings, Reference Billings2010), as opposed to other kinds of reception studies, have not passed without criticism (Martindale, Reference Martindale2013, pp.174–5). While there is reason to be sceptical about any intrinsic uniqueness of classical reception studies as a discipline, its development by interested academics has lent it a number of features which distinguish it from traditional Classics. Of course, there is still abundant scope for the discipline to develop in many different directions in the future, and a good curriculum would not operate to the exclusion of these potential routes. This is something which I kept in sight when planning this sequence of lessons. However, certain developments have so far given the discipline pedagogical potential for use in a curriculum which values creative thinking as much as analytical skills.

Take, for example, the idea of ‘the transhistorical’ in reception studies, which encompasses ideas related to engaging in dialogue with the past, and awareness of how a text's ‘future’ conditions our readings of it. In an article by one of its key proponents, there is clearly discernible ambiguity about whose role it is to engage in transhistorical work, and whether this is the role of the reader or of the creator of works of reception. Initially, it seems that the reader of works of classical reception is implicated as another receiver, and must partake in a dialogic process of understanding, ‘backwards and forwards’ (Martindale, Reference Martindale2013, p.171). Further into the idea's exposition, we find the transhistorical advocated as the seeking out of communalities across history, that is, something which could be the role of either the creator of works of classical reception or their reader (Martindale, Reference Martindale2013, p.173). Ultimately, however, the transhistorical emerges as a dialogue instigated by the creator of works of reception: in this case, Martindale notes Walter Pater's ‘version of reception, a layered transhistoricism’, which is present in order to be discerned by the reader. It is the role of practitioners such as Pater to read, here, ‘back from the present… through Winckelmann, through the Renaissance, to the antique’ (Martindale,Reference Martindale2013, p.179). The ambiguity of who is responsible for this dialogue, reader or practitioner, is not always noted in other discussions of the topic. For example, in her account of implementing aspects of reception studies in classical pedagogy at a university level, Friedman seems to see ‘the transhistorical’ as something done by the reader: students are encouraged to ‘read backward and forward’ (Hardwick, Reference Hardwick2003) for themselves, rather than to look for instances of this in others’ work which engage them in a significant dialogue with antiquity (Friedman, Reference Friedman2013, p.236).

This is arguably not an example of inconsistency in the scholarship, but an ambiguity which reveals something about the nature of the discipline. The discipline, even in its theory, struggles to confine itself to disinterested, academic appreciation of material which comes within its ambit. There is even acknowledgement that more creative, participatory approaches to its study, such as recreating ancient performance, might advance the discipline (Martindale, Reference Martindale, Harrop and Hall2010, p. 77). Much as there have been clear-sighted recent attempts to note the debt which scholars and practitioners of classical reception owe to one another (Hardwick, Reference Hardwick, de Haan and de Pourcq2020, p.16), the artistic and scholarly results of this cross-fertilisation reinforce the ambiguity between these two classes of receivers. Creation and re-creation have a role within the discipline, perhaps more so than in traditional Classics curricula.

Additionally, this ambiguity can be put to pedagogical advantage, if we accept a sufficiently broad idea of what skills a school education should encourage: ambiguity as to whether concepts such as transhistoricism apply to the works themselves, or to our intellectual responses to them, highlights the fluidity between practitioner and reader, and how creation can be informed by research. This method models for students of whatever age that they themselves are in a continuity of receivers of a classical tradition, and so can hold themselves to high creative standards. Within the entire discipline, regardless of the theoretical slant with which it is approached, works of reception have aspects of original creation while also being responses to pre-existing original works: both reflective and creative strands are present within them.

So far, the potential of classical reception studies has been exploited at a Key Stage 5 level as a means to achieve other pedagogical aims outside of those associated specifically with reception studies, and, at a university level, to help students appreciate how subsequent readings affect the reception of a classical text. Still remaining to be considered is, firstly, how reception studies can be made accessible to younger students, and how the ambiguities emerging in a discipline with many theoretical divergences can be utilised to create a natural pairing of academic and creative work, rather than being a source of confusion. I hope to explore how feasible it might be to exploit this latent potential in the series of lessons which I teach as part of this research, along with developing a definition of ‘creativity’ suitable for application in assessments of work in this subject specifically.

Differing concepts of ‘creativity’; measuring and assessing creativity

A benefit of teaching an almost entirely freely chosen curriculum is that I also had freedom in what type of student progress I could assess, particularly in a school where end-of-year assessments had been abolished for Year 7. This meant that, while still adhering closely to the school's marking and tracking policies, I was able to approach the skills which I wish a reception studies module to cultivate in students more experimentally, and was able to attempt to measure more supposedly abstract skills such as creativity. Teachers are also able to nominate Year 7 students as Gifted and Talented, a label which will remain with them throughout their Key Stage 3 studies, and so I was hoping to assess students’ creative potential partly out of a hope that a fully rounded perspective, taking into consideration things other than academic, sporting, musical, etc. achievement can inform whether a student is considered to be Gifted and Talented.

Problems in creating school-appropriate assessments of creativity

A huge number of contributions towards defining creativity exist. Even excluding those formed in the historical development of the subject (Runco & Albert, Reference Runco, Albert, Kaufman and Sternberg2010), an idea of the scale can be gained from Treffinger's (Reference Treffinger1996) summary of the findings of over 100 studies. Because of this proliferation of posited definitions and perceived components, the assessment of creativity is a similarly complex subject with a long history (Plucker & Makel, Reference Plucker, Makel, Kaufman and Sternberg2010). A particular problem when attempting to assess school-age students’ creativity is that existing assessments which might be of use within a school context look, albeit sometimes distantly, to creativity measurement in adults: past studies have simply involved adults more often than children (Treffinger et al., Reference Treffinger, Young, Selby and Shepardson2002, viii). They have their origin in the context of psychology rather than education: many past instruments for measuring creativity aim to find traits of the ‘creative person’, and aim to assess personality, attitude and activities (Plucker & Makel, Reference Plucker, Makel, Kaufman and Sternberg2010, pp.56–58). These kinds of psychometric tests seem, generally speaking, designed to measure fairly static characteristics, while educational exams are designed to measure the application of skills. However, given that it is ultimately not possible to wholly separate the intrinsic from the learnt, these two broad categories of assessment, the psychometric and the educational, are not completely incompatible, and can inform one another.

Psychometric tests, for example, run the risk of treating creativity as something static or intrinsic. More desirable in a school context is to treat it as a mind-set which can be grown, an approach which can be complemented by the principles of Assessment for Learning (Black & Wiliam, Reference Black and Wiliam2009). Others have advocated the ‘grow-ability’ of creative mindedness (Lucas & Claxton, Reference Lucas and Claxton2010). This outlook seems compatible with the idea that student achievement is not fixed and that feedback is central to improvement (Black & Wiliam, Reference Black and Wiliam2009). This approach is again complemented by the fundamental differences between undertaking research as an involved practitioner rather than an impartial observer: the research inevitably counts as ‘action research’, which seeks to improve learning outcomes (Verma & Mallick, Reference Verma and Mallick1999, p.93), not simply to measure them. However, as creativity assessments have often been developed with a psychometric end in mind, or to measure the ‘innate’ capabilities of children already deemed Gifted and Talented (Shively et al., 2018), there is something of a conflict between existing creativity assessments, which have their roots in measuring something perceived to be ‘innate’, and the principles of Assessment for Learning, in which it is stressed that work rather than ability is commented on in feedback (Black & Wiliam, Reference Black and Wiliam1998, p.145). I hope to try to compensate for the bias towards regarding creativity as ‘innate’ by developing ways in which it can be encouraged to develop through assessment.

Additionally, this enquiry operates against a background of limited existing research into how creativity might be differently defined with regard to children and adults. Recent research into children's creativity does not necessarily acknowledge the problems which this poses (Kupers, Reference Kupers2018). The difference between past measurements of creativity, which have largely been designed with adults in mind, and the aim of assessing creative potential in school-age students, is a problem which should be borne in mind, but which cannot be actioned within the scope of this research. It is hoped that an assessment process tailored to the needs and abilities of the students in this particular context will mitigate this issue.

Towards a reception studies-specific definition of creativity

Given that there are so many ways of assessing creativity, it is also desirable to adopt a definition and an approach to assessment which are suitable to the subject specifically, or even to a specific task: this point has been made with reference to adult training programs (Barbot, Reference Barbot2011, p. 130), and the same is arguably true of school education. Rather than asking how a subject is suitable for assessing qualities or skills which have been arbitrarily decided on as components of ‘creativity’, it seems more productive to ask what creativity means, and how it can be encouraged, within that specific subject and against a particular cultural background. This is especially true if a potential definition of creativity as reliant upon interactions between a person and their environment is incorporated (Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Csikszentmihalyi and Sternberg1988). An approach of largely formative assessment therefore seems desirable once again, combined with a notion of creativity which is specific to the subject, to the age-group under consideration, and to a school context.

There are several factors which make reception studies a discipline suitable for encouraging the development of skills associated with creativity. While far from unique in the combination of academic and creative skills required in the subject, the discipline is developing in such a way that there is much emphasis placed on the importance of readers as participants in, not merely observers or critics of, the classical tradition. There is therefore an argument for assessing skills other than those assessed in other classical subjects, such as the explanation and analysis of factual knowledge. For example, an integral part of the discipline is the resolution of ambiguity, the fitting of old stories to new contexts. The resolution of ambiguity is also a recurring idea in the definitions of creativity: Treffinger's meta-analysis records the desire to resolve and the tolerance for ambiguity as mentioned in eight separate studies on defining creativity (Treffinger et al., Reference Treffinger, Young, Selby and Shepardson2002), although this is the result of reviewing literature which itself is not necessarily the result of systematic research. It would be possible to test for students’ sensitivity to how well ambiguity has been resolved by asking students to analyse how successfully others have done this, but there are benefits to assessing how well students are able to do this themselves. Knowledge of narratives and contexts is a necessary underpinning for success in resolving these kinds of ambiguity and so creating meaningful works of reception. Incidentally, this fulfils a key idea behind Bloom's taxonomy as guidance for assessment (Case, Reference Case2013): assessing a higher-order skill necessarily means assessing for at least one lower-order one. Consequently, my working definition of creativity within this discipline involves the originality which comes from awareness of self (and others) as receivers of a tradition, the ability to resolve the ambiguity of old stories and new contexts, and sufficient knowledge of narratives and contexts to produce and select ideas.

Educational researchers and practitioners have made a number of rubrics and criteria for assessing creativity publicly available. However, many of these will be more suitable for assessment in some subjects than others. For example, although Shively's rubric for anchoring assessment criteria on the definition of creativity (Shively et al., 2018, p.150) is a useful template in some ways, especially as an exemplar rather than a functional rubric, its capacity to be used in other contexts is limited. It adopts Guildford's definition of creativity, which includes fluency, flexibility, elaboration and originality (Guildford, Reference Guilford1950), with only minor selectivity and adaptation of the definition: it adds the criterion of taking the user's needs into consideration. The final criterion, that of ‘usefulness’, has meaning within a science project, but it is less clear what an equivalent would be in the humanities. In order to avoid the pitfall of being overly-general, I designed my own criteria for assessing creativity which was specific to the subject which I was trying to teach, but which was made with reference to pre-existing models of creativity assessment, in this case Treffinger's ‘creativity characteristics’.

The rubric used (Figure 1) is based on three of Treffinger's four categories of ‘creativity characteristics’, excluding the category Openness and Courage to Explore Ideas (characteristics from this category seemed heavily based on more personal characteristics rather than what was observable through a student's work). The generation and selection of ideas (1) equates to Treffinger's Generating Ideas, which can be measured through tests of a student's level of divergent productivity; its other aspect, that of selecting promising ideas to develop, would be more subjectively assessed by a teacher. Synthesis or reconciling ambiguity (2) overlaps with Treffinger's Digging Deeper Into Ideas, and originality and quality (3) partly with his Listening to One's ‘Inner Voice’, which is advisedly best assessed through self-report inventories (Treffinger et al., Reference Treffinger, Young, Selby and Shepardson2002, p.48). The ‘originality’ aspect of (3) is certainly based on this, but the additional criterion of ‘quality’ was introduced to distinguish this rubric from more psychometric assessments of creativity referred to in section 2a. The series of lessons was designed to improve students’ use of perspective and style when writing creatively, and not simply to measure their ‘innate’ capacities to this end. However, the rubric does not entirely eradicate the measurement of skills which have not been explicitly taught within the lesson sequence: for example, students will be reliant on their own capacity to generate ideas during their final project. This mixing of approaches is perhaps one of the rubric's key limitations. I created the rubric used in line with the marking system which the school uses at Key Stage 3, where 3 is given to lower-quality pieces of work, 2 for acceptable, 1 for good, and a merit for outstanding.

Figure 1.

Ethics

All names and other identifying features have been anonymised: the class ‘7A’ referred to in the lesson plans is a pseudonym. The scope for collecting data during this project was unfortunately non-existent owing to school closures, and so gaining consent and other ethical questions were not relevant.

Lesson Plans and Evaluations

I was working with an unusually committed class, who contributed often and well, so the amount of work which I expected them to complete might seem challenging for a Year 7 level. The school environment was also extremely well-funded, hence the use of school-provided iPads by students. This may affect the transferability of this specific sequence of lessons to other contexts, although not necessarily the ideas and objectives underpinning the sequence.

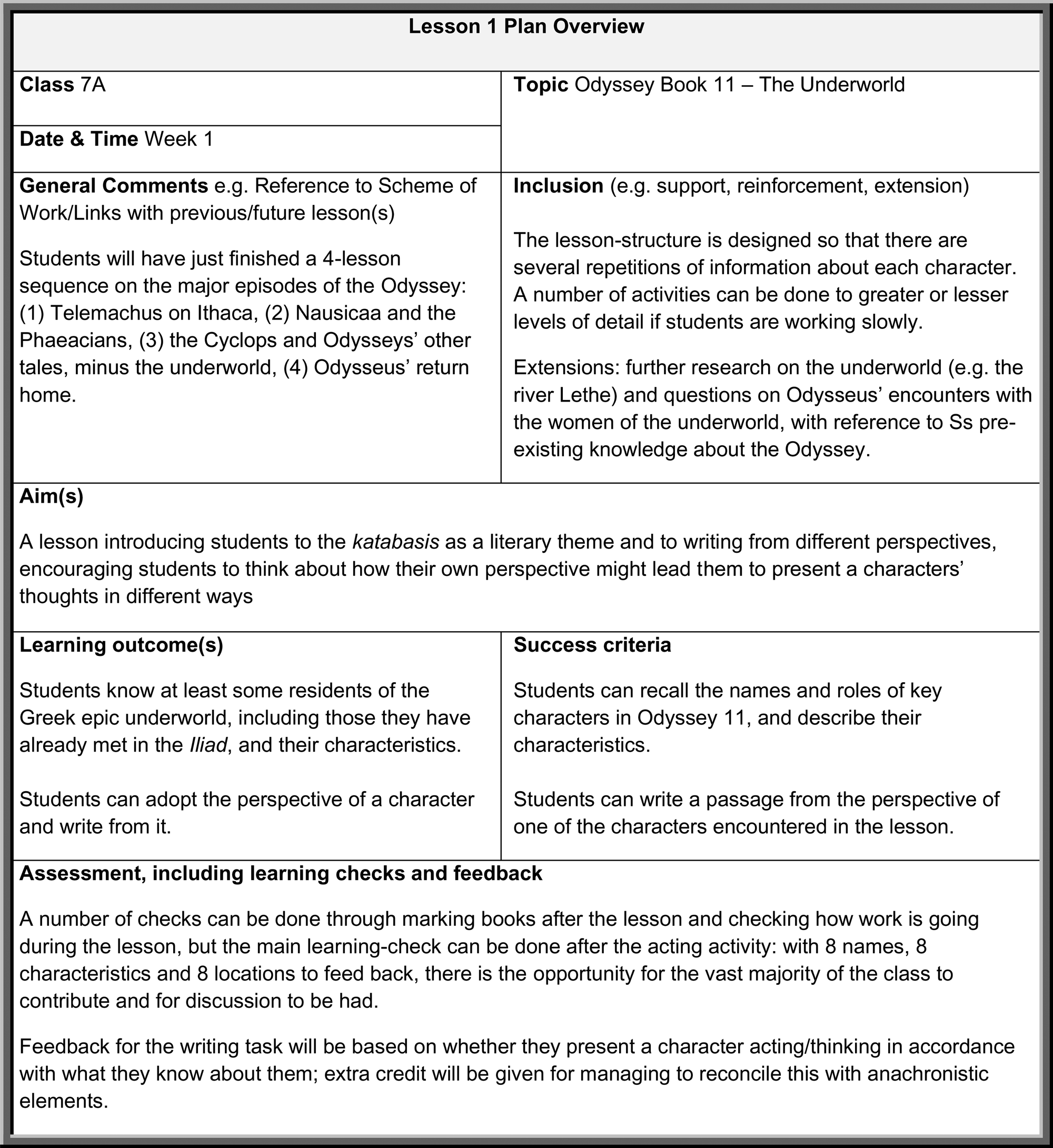

The learning objectives of each lesson are meant to increase students’ knowledge as well as their skills. The acquisition of knowledge is an important component of high-quality reception studies: presenting ancient material in new ways requires considerable knowledge of different historical contexts and of classical literature. This means that large parts of each lesson will aim at students absorbing and putting information to use, both about the classical texts studied and, in the case of Lesson 3, about other historical periods. Aside from knowledge-based Learning Objectives, each lesson aims to reinforce an objective based around the creative writing skills which reception studies can encourage and develop. For example, Lesson 1 considers writing from different perspectives, encouraging students to think about how their own perspective might lead them to present a characters’ thoughts in different ways (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2.

An important overarching focus of the creative aspects of the lesson sequence was the encouragement of creativity as a growable mind-set: feedback from teachers and peers, questioning, discussion and learning-checks were used to support pupil progress in this area. These come into play to an increasing extent as the lesson sequence progresses: the first lesson is designed to bridge previous lesson sequences with this new, reception-studies approach, as well as ensuring that students have secured the basic information about the Underworld in Greek and Roman thought.

The final slide on each PowerPoint (see Appendix 3, slide 15) is intended to point towards resources, without drawing attention to them obtrusively or unnecessarily, for students who might find considering death more distressing than others.

Lesson Sequence

Lesson 1

In this lesson, students are introduced to the ancient Greek idea of the afterlife and compare it with their own beliefs (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Figures 4a and 4b are examples of the activities which students undertake to compile information about the myth of the Underworld.

Figure 4a.

Figure 4b.

Drawing (implicitly) on their own beliefs and ideas, they share at the start of the lesson whether they think the notion of the Underworld is fair, once they have been introduced to its ideas via a PowerPoint presentation in class. Various activities (see figures 3 and 4) then reinforce information about the underworld in the Odyssey which they compile on a chart (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

An extension (see Figure 6) gives students the opportunity to engage with classical texts in a more critical way.

Figure 6.

Students in this school are introduced to the rudiments of feminist theory in Year 7 English lessons, and so may be able to consider the ‘Catalogue of Women’ passages from the Odyssey, which I included as a point of connection with previous learning (the mothers of various heroes whom the students had already encountered are present in it), and note, in simplified form, how the passage gives ‘the impression that female identity is derived from connections to males’ (Doherty, Reference Doherty1991, p.167). Realising how women, even in the Underworld, are circumscribed owing to how they are remembered and presented by Odysseus, could inform their homework task in engaging ways.

Lesson 2

This lesson (see Figure 7) begins with students peer-assessing one another's work, so that each writer gets a sense of whether their ‘aim’ for their piece was achieved in the subjective view of another student.

Figure 7.

This is in order to enhance their sense of audience: the requirement for creativity to serve a purpose within a social context is one often adopted by those seeking to define and assess it (Shively et al. Reference Shively, Stith and Rubenstein2018; Runco & Jaeger, Reference Runco and Jaeger2012). An adequate equivalent for this criterion within this particular learning context is for the students’ creativity to have a desired effect on an audience. Peer assessment will be later moderated by teacher feedback when books are handed in at the end of the lesson, meaning that the feedback process will be fresh in students’ minds before their final project is introduced at the end of the next lesson.

Students are then introduced to key scenes in Virgil's Aeneid 6. Using a whiteboard-like function on their iPads, students are shown a series of pictures which represent one of the five characters they have met so far, and are asked to write down which character they think is being shown. Students use visual clues to corroborate their image of the character gained from the mini-lecture: even if all students provide the correct answer, there is an opportunity for discussion when asking students how they came to the right answer.

Students are then given a choice of which passage from Aeneid 6 they would like to look at in detail. Using worksheets, students then compare in detail the two versions of the passage, one from Seamus Heaney's translation of the Aeneid, and one from a prose version of the Aeneid (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Finally, they swap passages, and attempt to create their own version of that passage with a particular stylistic aim in mind. The activity should not take too long and not be set for homework, as some students may still struggle to understand why you might want to write something very similar to a pre-existing text, even when having been exposed to the idea of translation.

Lesson 3

For details of the lesson, see Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Students are introduced to a new underworld myth, that of Orpheus and Eurydice. While the story is told to them through the IWB, they are asked to make and fill in a graph on Eurydice's emotional state at each point in the story (see Figure 10). This will both keep students’ attention focused and hopefully will elicit differing views about Eurydice: what if Eurydice wasn't having such a bad time in the Underworld, etc.? At this point in the lesson, effective questioning will be utilised to contribute to students’ creative thinking: the discussion of different ideas will open up the creative possibilities of looking at a myth from different perspectives, reinforced with relevant follow-up activities (Black & Wiliam Reference Black and Wiliam2004, pp.12–13).

Figure 10.

We then look at a 3-minute extract from Offenbach's Orphée aux Infers, a parodic opera of the myth which presents Eurydice, unhappily married to violin-teacher Orpheus, as having an affair with Hades, and questioning students about whether Orpheus and Eurydice seem very happy together (they do not). This introduces the idea of altering a myth by putting it in a new context, here for comic purposes. Following on from this, another musical form of the myth is then introduced, this time the popular folk-opera album and Broadway musical Hadestown, which reimagines the Orpheus myth with a 1930s American aesthetic, a context which is common to other typical set texts in English such as Lee's To Kill A Mockingbird and Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men. An introductory video is played to engage pupils’ interest, followed by a slightly ‘drier’ section on how the musical utilises a particular period of history: this should be done as quickly, clearly and dynamically as possible, in order to avoid losing class interest. The next activity should hopefully regain any lost interest: the class then watches 3 further short extracts from the musical, and, using the mini-whiteboard function on their iPads, suggests which historical events might have informed each song (see slides in Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Students then render in the form of a table how the myth is viewed through a particular time-period: being provided with some aspects of the raw material of the original Orpheus and Eurydice myth, they then fill in the table with suggestions of both what changes the resulting artwork (Hadestown) makes to the original, and how the lens through which the myth is viewed and re-shaped (1930s America) might have informed this (see slides in Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Finally, their end-of-module project is introduced. Students are given a sheet to produce ideas on and a ‘draft’ sheet, so that they can justify and develop their ideas fully. This is especially relevant for those who might not take to the lengthy nature of the project, with its mix of class time and homework time. In keeping with the rest of the sequence, students are encouraged to produce a draft version and comment in the margins on what the effect of certain words or phrases will be on the reader, using techniques which they practised on poetry in Lesson 2. This will help to draw their learning together and ensure that skills learnt in previous lessons are put to use.

In terms of assessing students’ work through this project, the aim was to give students a number of possible routes to success: while they might choose to utilise other historical contexts when re-telling their myth, there is no obligation to do this, as long as their choice of characters gives them the opportunity to demonstrate their ability to reconcile ambiguity. This is especially important in a subject such as reception studies, when a number of different approaches are viable. For example, a performance as a work of classical reception can indeed be seen as ‘an embedded event in culture and in history’ (Goldhill, Reference Goldhill, Harrop and Hall2010, p.69), and the work of reception studies is to recover the context of this as accurately as possible. This scheme of work and its assessment methods inevitably underplay the side of historical inquiry, in favour of emphasising creative processes and drawing attention to how the use of historical contexts can lead to new creations, but ideally it should avoid promoting one aspect at the total exclusion of others.

Lesson 4

For details of the lesson, see Figure 13

Figure 13.

This lesson does not aim to introduce much new material, as students will have already begun their final project. Through the myth of Demeter and Persephone, and a game (see slides in Figure 14) it aims to give students the opportunity to practise a key skill for creating works of classical reception, that of reconciling a classical myth or text with a different context. This is intended as a rapid game, as it could quickly become less interesting for more focused pupils: it is meant partly as a counterpoint to the long, involved work required for their projects. To bring the game to a close, students will then be asked to pick their favourite two cards and write up, in the form of a short story, a new version of the myth.

Figure 14.

Finally, in preparation for sustained work on their projects, a plenary for the whole topic takes place in the form of a structured discussion. Students are asked what kinds of classical reception they have enjoyed or not enjoyed looking at, and why, in order to develop criteria for what they consider to be valuable works of reception. This is intended to give students a sense of agency in their creative processes: much as there are subjective aspects to assessing quality, particularly in creative fields, there are processes which can be undertaken to determine whether an instance of creativity is a valuable contribution or not (Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Csikszentmihalyi and Sternberg1988). The remainder of the lesson will be devoted to silently working on their projects, with Hadestown as background music to encourage a state of creative ‘flow’ (Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Csikszentmihalyi1996).

Conclusion

Although I can only speculate on the outcome of these lessons, it has nonetheless been productive to consider the pedagogical potential of classical reception studies in its own right. Much as providing the subject with its own discrete learning objectives was not a simple undertaking, when so many other skills and areas of knowledge from different disciplines inform the subject (such as writing skills from English, and factual knowledge from History and from Classics), I believe that the subject does have a capacity to encourage discursive and creative thinking, owing to how essential the reconciliation of ambiguity is to it. Planning this scheme of work has allowed me to think in detail about how creativity can be developed among all students, and how progress in this area can be encouraged through assessment. In particular, the idea of peer assessment comes into its own when creative assignments are being assessed: owing to the subjective nature of determining quality in creative writing, awareness of the effect which a piece of writing has on a reader creates useful guidelines for further development.

However, having planned this scheme of work, there are a number of underlying areas of research which I would have ideally considered before planning the sequence. Uppermost of these is the possibility of creating a reception studies curriculum that is genuinely suitable for school-age students. As development of the pedagogy of classical reception studies has thus far been almost exclusively confined to universities, inspiration regarding materials, aims and methods often came from that quarter. Much as I naturally compensated for this in the kinds of material and activities used, there are numerous differences, such as the likely motivation and interest of students, the format of teaching and the assessment methods, between schools and universities. Without considering the ways in which educational setting has affected the development of the subject, it is difficult to advance its pedagogy, especially when the school environment has made such a strong and long-lasting impact on how classical language and literature are typically taught.

Classical reception studies have not yet achieved stable form: a healthy level of revision and questioning of tenets exists within the discipline, and earlier mantras are frequently scrutinised. For example, the broad applicability of Martindale's dialogic approach has been recently challenged by Hardwick (Reference Hardwick, de Haan and de Pourcq2020, p.17). She notes that the high status of the approach, in particular its use as a rationale for the study of classical reception as a whole, has left it treated as unchallenged fact rather than hypothesis: a range of other approaches may be more suitable depending on the characteristics of the unique work of reception under consideration. The discipline remains in a state of high theoretical complexity owing to this kind of instability. Its current state is excellent for inspiring further scholarly debate and research, but what elements of this should filter down into school-level pedagogy, where a greater level of clarity and simplicity may be required to effect good teaching, remain uncertain. It is certainly worth questioning how we ought to frame the relationship between school-level and university-level classical reception studies: it may not prove ideal for school-level pedagogy to precisely mirror the theoretical development of the subject within universities. Instead, there is scope for the development of a pedagogy of classical reception studies suitable for use in schools specifically.