Illustrations of the ‘dying Socrates’

From the beginning of the 15th century onwards, as Renaissance and Enlightenment art developed, depictions of Socrates centred on the fact that he remained in prison and was poisoned by hemlock. Until then, the most often illustrated death scene was that of Christ. However, the spread of the works of ancient writers at that time led to a shift to ancient Greek literature and brought to the fore the life and death of important personalities of antiquity (Wilson, Reference Wilson2007; Perry, Jacob, Jacob, Chase & von Laue, Reference Perry, Jacob, Jacob, Chase and von Laue2008). The main sources of information about the last moments of Socrates were the Platonic dialogues Crito and Phaedo.

At the same time, the increase of the population in the western world along with the development of the cities contributed to a change of burial habits. Until then, burials took place in the temple precincts, in common daily view. The relocation of necropolises away from residential areas turned the fact of death into an infrequent and negatively charged emotional theme, capable of inspiring art (Dexeus, Reference Dexeus2016).

Especially for Socrates, the depiction of his death emerged as an extremely popular illustrating trend, as the philosopher's name remained in immortality through the way in which he dealt with the issue of his condemnation. Therefore, the death of Socrates was considered a socio-politically unconventional event (Wilson, Reference Wilson2007).

Artistic creations presenting the death of Socrates. Methodology of approaching the works

The artistic creations studied in the research of this article number 21, mainly belonging to the 17th and 18th centuries. We have chosen these artworks because of their common subject (the death of Socrates) which was extremely popular during the Enlightenment (Wilson, Reference Wilson2007). In addition, apart from an abstract work of art by the Dutch painter Jan Cox on the same subject, no other representations of the dying Socrates were found.

In our attempt to interpret the selected artworks, we initially consulted the existing bibliography, but the main interpretation was semiotic and made through the three metafunctions of nonverbal communication presented in Kress & van Leeuwen's Grammar of Visual Design. In particular, the representational metafunction distinguishes the images into narrative and conceptual. Narrative representations mainly include paintings and examine the relationships between participants through the mental vectors that connect them (Kress & van Leuwen, Reference Kress and van Leeuwen1996: 45–78). In the interpersonal metafunction, the way the structural elements of an image are positioned can determine the type of communication sought through contact, social distance and perspective. As for contact, the figures that avoid the observer's look are seen as an ‘offer’, while those trying to attract his/her look are depictions of ‘demand’. Social distance defines the scope of the observer: that is, the closer he is, the more desirable the requirement is. The social distance is direct (only the head is visible), close personal (head and shoulders), distant personal (upper torso), close social (whole body), distant social (body with surrounding space) and public (many people). The study of perspective examines the intention for the observer to be emotionally involved in what is depicted. The horizontal perspective implies a direct engagement when it is frontal and an indirect one when it is sideways. A vertical high perspective implies the observer's dominance over the represented figures, an equal engagement when it is equal, and the viewer's submission to what he sees when it is low (Halliday, Reference Halliday and Matthiessen2004: 106–108; Kress & van Leeuwen, Reference Kress and van Leeuwen1996: 55–59, 62–63, 67–78). In addition, the textual metafunction examines the emphasis given to certain elements of the image in its composition. The parameters that are examined are the informational value, the projection and the framing of the represented. As for the informational value of the displayed elements, the vertical separation of the image in two parts creates two spaces. The left part (Given) represents the start and the old, while the right part (New) equals to the ending. A horizontal separation, respectively, creates the spaces of the Ideal and Real. The most important element of the image is usually placed in the Centre, while the least important is in the Margin. Finally, Projection examines which of the above elements is projected the most, while Framing reveals how the elements of the representation are connected (Kress & van Leeuwen, Reference Kress and van Leeuwen1996: 114–142).

This article's novelty is (a) that it attempts to use the analysis of paintings which represent the death of Socrates (at first we use David's famous creation) to form a teaching proposal through the Artful Thinking Project of Harvard University; and (b) it attempts to classify the paintings on the subject of the death of Socrates in a proposed typology which is not found in the bibliography.

‘La mort de Socrate’, Jacques-Louis David

In David's painting (Figure 1), Socrates is robust and attractive. The movement of his hand seems to receive - rather than leave - the cup with the poison, connecting the figure of the philosopher with death. However, the upward movement with the other hand symbolises a transcendence, a victory after resistance (Henderson, Reference Henderson1996; Arnheim, Reference Arnheim2011): in this case it is Socrates's passage to the eternity.

Figure 1. ‘The Death of Socrates’ by Jacques-Louis David, 1787, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Available online: https://frear.gr/?p=20006 (accessed 1 May 2021).

The representation can be divided into two parts (Given - New) with a vertical imaginary line passing through its centre (Kress & van Leeuwen, Reference Kress and van Leeuwen1996). In the left part there is the young man giving the cup with the poison to Socrates. We can also see Plato and Apollodorus in deep sadness as well, with Socrates’ family leaving the prison. In the right section Socrates teaches, with Simmias and Kevis watching sorrowfully, while Crito seems impatient. The cup connects all figures, seeming to symbolise the transition from one world to another, from the Given to the New, as it is located exactly in the middle of the imaginary perpendicular, while the vectors from the hands of the employee and Socrates lead to it (Lapatin, Reference Lapatin, Abbel-Rappe and Kamtekar2006).

The narrative course of the painting from Given to New begins with the figure of Plato which appears detached from the event, turning his back to the facts. This fact may be a reminder of his absence from his teacher's last moments, but also of the use of his narratives as sources of the depiction (Lapatin, Reference Lapatin, Abbel-Rappe and Kamtekar2006)Footnote 1.

A second form attempting to attract the observer's eye is the figure of Crito. Crito puts his right hand on Socrates’ knee, trying to interrupt what he is saying, while his left hand is raised close to his face in a gesture of waiting for Socrates' answer to the escape proposal. Fatally, therefore, the viewer's gaze turns again to Socrates, who seems ready to state his refusal. Eventually, Socrates will choose the fate reserved for him by the Athenian state (its symbol is carved on the seat of Crito) and will ignore Crito's urgings to escape. The importance that the painter gives to Crito's proposal is possibly highlighted by the fact that he places his full signature on the base of his seat (Lajer-Burcharth, Reference Lajer-Burcharth1999).

The painter implies that Socrates was unjustly condemned, as the servant and the philosopher both look away from the cup, in which the lines of their hands converge (Lapatin, Reference Lapatin, Abbel-Rappe and Kamtekar2006). It is worth noting that the persons in the painting - except Socrates - are 12, a fact that relates to the12 Apostles of Christ and gives Socrates the aim of a divine transcendenceFootnote 2.

David was inspired by revolutionary ideas and his paintings contain political messages (Carrier, Reference Carrier2003). He was a friend of Robespierre and envisioned a new France shortly before the outbreak of the French Revolution. In this case, therefore, the example of Socrates is an inspiration for a call to revolution (Colaiaco, Reference Colaiaco2001; Wilson, Reference Wilson2007).

A proposal for using the above artwork in teaching

Subsequently, this article presents a teaching proposal based on Harvard University's Artful Thinking Project, a model of artworks approach, which includes a set of actions through which the students can explore art by discovering its details, practising their communication skills and cultivating their critical thinking.

The proposed teaching approach focuses on the following:

1. The students make a rough description of the artwork by identifying the elements that attract their attention, in order to clarify the main protagonists and to trigger further investigation.

2. The students examine the artwork in depth, in order to discover the relationships between its structural elements. Then they try to compose the narration.

3. The students represent the narration through role-play. They discuss their experience and create variations. Finally, they examine excerpts from the original texts (Crito, Phaedo) which were the source of inspiration of the artist and discuss them by comparing them with the artwork.

The stages of the proposed approach are as follows:

Stage A) ‘Observe and Describe’

Objective: To find the title of the artwork and to identify its main protagonists:

• On which element does our eye fall first?

• What makes us think when we see it?

• What else does one pay attention to at first glance?

• What could be the title of the painting?

• What else would we like to examine more?

Stage B) Examining the complexity of the forms:

Objective: To find relationships and connections between the structural elements of the artwork:

• What other objects or elements do we observe in the painting?

• Which colours impress us the most?

• What kind of shades are used?

• What's in the centre of the painting?

• What items are on the sidelines?

• How is the element in the centre related to the elements in the margin?

Stage C) ‘Expressing my opinion on the narrative’

Objective: To gradually compile the artwork's story

• From what point can the narration start? Why?

• Who is the protagonist of the story? Where is he/she located? How is he/she depicted?

• How does the story continue and end?

• Which piece of music would fit in this case?

Stage D) ‘Adopting the role of the characters represented’

Objective: Empathy through the role of each represented character.

We can use the technique of role-play and perhaps a vivid depiction of the painting through an imitation of posture:

• How did you feel when you imitated the attitude of this character?

• How do you think he/she felt? What, in your opinion, was he/she thinking?

• Why, in your opinion, do the characters behave like that?

• What is the message that the artist wants to convey to the observer through this artwork?

• What would you change in this painting?

• What would have happened if the [chosen] element had changed?

Stage E) ‘Connecting the artwork with its ancient textual source’

Objective: To compare textual sources with visual representations

Students read the text(s) and try to find elements of the table narrative in it/them.

• Where does the painting describe the events differently than the ancient sources?

• Why do you think this is happening?

• What does the creator want to emphasise more through this difference?

Stage F) ‘Putting the artwork in historical synchrony and diachrony’

Objective: To discuss the personality of Socrates, based on the critical investigation:

• What were the characteristics of the Enlightenment era?

• Why was Socrates a role model for the artists of that era?

The above teaching proposal can be applied in 90 teaching minutes. However, it can also be the subject of a broader project, which includes the study of more artworks. The teacher can use a proposed typology (see section 6) by selecting a painting from each category: Socrates teaches, takes the cup, drinks the poison and eventually dies, thus composing the last moments of the Athenian philosopher. The number of projects and textual sources that can be used depends on the additional objectives that the teacher can put forward.

As a brief synopsis, the reading of Socrates's artistic depictions is of particular importance and value, especially for students in formal education. For this purpose, we presented the above didactic proposal for the ‘dying Socrates’. The proposal is built on principles that focus mainly on understanding the visual content, as an exemplary way of thinking about actions of socio-political importance and self-improvement.

The above teaching proposal is based on two pillars. The first is the Grammar of Visual Design, which uses semiotic information to extract the importance of elements in a painting in its attempt to interpret the painter's communicative intentions. This practice helps the students to cultivate visual literacy by pushing them to discover and highlight elements of an artistic creation that are not visible at first glance.

In addition, the use of Artful Thinking helps the teacher to proceed with small, short steps in the interpretation of the artwork. Through this program, critical and creative thinking are cultivated, as students are asked not only to point out important aspects of the artwork, but to become themselves a part of the story.

The above teaching proposal can also be applied to other artworks. Especially for Socrates, we have collected the artworks of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment depicting his death. Additionally, we organised them into a new proposed typology. In this way, the teacher can use the material as they wish: either by proceeding with a single painting, or an entire typological category.

Presentation of the proposed typology of the artworks depicting the death of Socrates

The subject of Socrates' death covers a wide period which coincides with the Enlightenment during which the political, social, economic and cultural status quo was challenged. On this basis, Socrates was an example of a teacher who focused his philosophy on man and emphasised ethics as an absolute concept. Socrates' subversive teaching was supported in his trial while he rejected any proposal to escape from the prison cell, placing his principles above any utilitarianism. This attitude is reflected in the majority of the examined artworks; Socrates shows calmness and willingness to teach until his last moment.

Our proposed classification of artworks concerning the death of Socrates follows two criteria. The first criterion, the illustrative, classifies the artworks according to the way they present Socrates. The new typology includes four categories: (a) the ‘robust’ Socrates, (b) Socrates taking the cup of poison, (c) Socrates drinking the poison, and (d) the ‘dying’/ ‘dead’ Socrates. The paintings are sorted within each category through the second criterion, the chronological order.

1. The ‘robust’ Socrates

In this category Socrates is depicted sitting on his cell's bed talking to his companions. One of his hands is lowered and he holds or tends to take the cup with the poison. His other hand is raised to the sky.

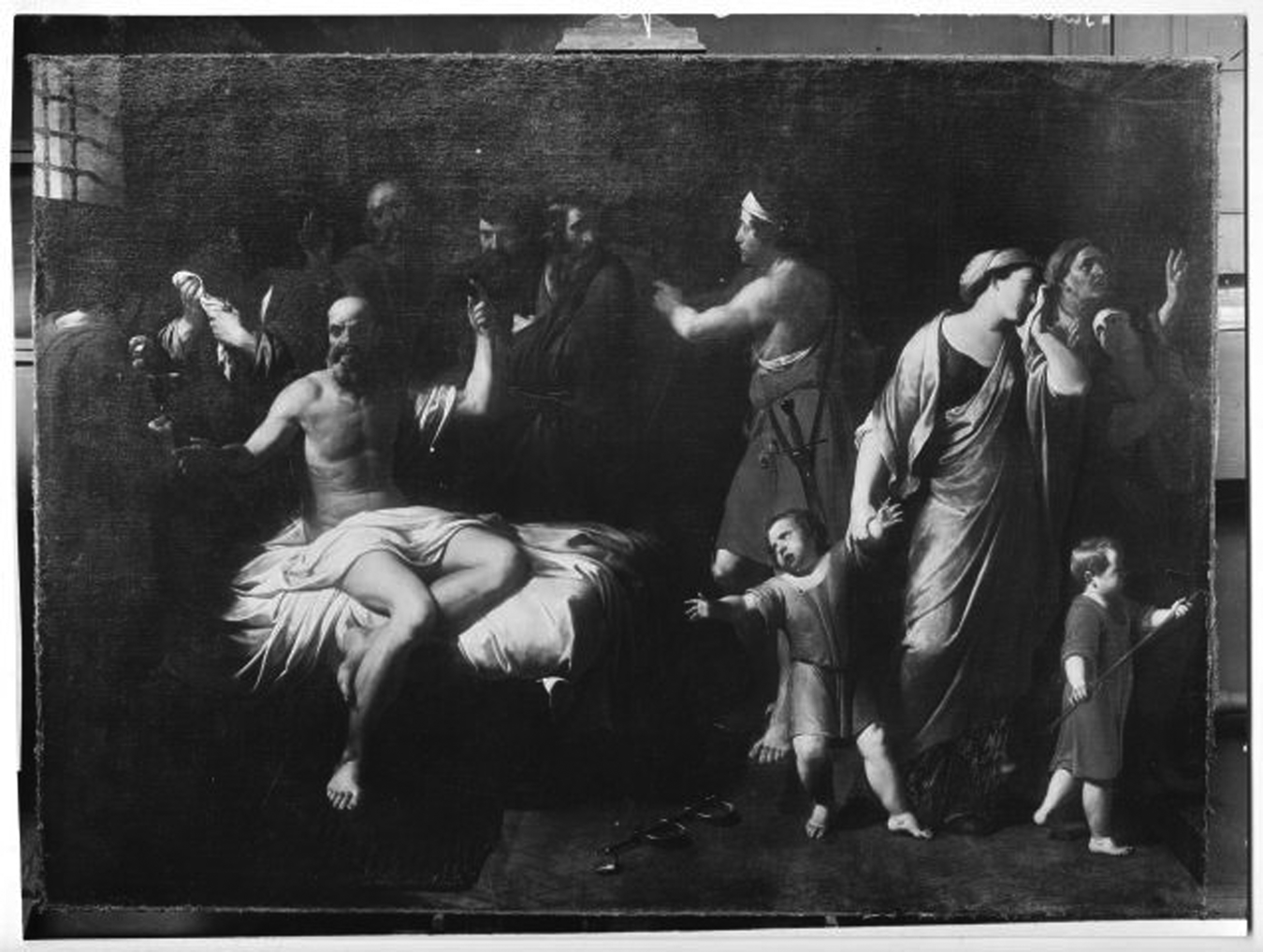

1.1 ‘La morte di Socrate’ by ‘Maestro degli Angeli Pallavicini’, imitator of Caravaggio

The painting (Figure 2) was probably made in the early 17th century by an imitator of Caravaggio under the pseudonym ‘Maestro degli Angeli Pallavicini’. It was destroyed at the end of World War II and therefore we do not know the colours used by its creator. However, for an imitator of Caravaggio, the main feature should be colour contrasts, shading, along with a baroque theatrical style that composes an effect which emotionally provokes the viewer.

Figure 2. ‘La morte di Socrate’ by ‘Maestro degli Angeli Pallavicini’, imitator of Caravaggio, early 17th century. Available online: http://catalogo.fondazionezeri.unibo.it/scheda/opera/49885/Maestro%20degli%20Angeli%20Pallavicini%2C%20Morte%20di%20Socrate (accessed 1 May 2021).

The representation can be divided in half with an imaginary line, so that the viewer watches two parallel stories, in each of which six people participate. On the right side, Socrates is in the Centre and points to the sky (the Ideal) symbolising his impending passage to eternity. His figure is bright, in contrast to the mourning companions around him. Socrates' attention is on ‘higher things’ (Wilson, Reference Wilson2007). On the left side of the table we can see Xanthippe (Centre) leaving. The eyes of both are in diametrically opposite directions, while the two episodes are connected by (a) a sword-carrying figure following Xanthippe, talking to a Socrates’ companion, (b) Socrates’ young son, trying to reach his father but being pulled away by Xanthippe, and (c) the broken shackles which may symbolise the breaking of Socrates' bonds with worldly life. The connection between the armed figure and Socrates’ companion could be a call for struggle or a reminder of a mission as the sword has been a symbol of strength, courage and war virtue (Dall ’Armellina, Reference Dall’ Armellina2017).

1.2 ‘La mort de Socrate’ by Jean-Francois-Pierre Peyron

In Peyron's painting (Figure 3), Socrates is placed in the Centre of the image, ready to receive the cup with the poison, surrounded by companions whose mourning is shown by expressions or gestures. In the Salience of the representation Socrates raises his hand to the sky implying the journey to eternity, while with his other hand he takes the cup from the disk without looking at it. There are large gaps of dark background between the figures, leading the observer's gaze to the projected figures of the foreground. The viewer is called to participate equally on the stage, through a horizontal frontal and vertical equal perspective.

Figure 3. ‘La mort de Socrate’ by Jean-Francois-Pierre Peyron, 1787, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen. Available online: http://users.sch.gr/ipap/Ellinikos%20Politismos/Yliko/Theoria%20arxaia/metafraseis%20c%20gym/c9xm.htm (accessed 1 May 2021).

The artist leaves in more careful observation some details, such as the broken chains (reference to Phaedo) and the fact that Socrates turns to the only source of light that exists. However, it makes clear that the restless Socrates represents the past (his teaching), the present (the fact of his death) and the future (his passage to immortality) (Einecke, Reference Einecke2001).

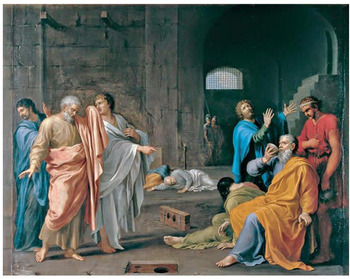

1.3: ‘La mort de Socrate’, Jean-Francois-Pierre Peyron

After exhibiting his painting with that of David at the Salon, Peyron returned with a new version, in which he seems to have been influenced by David (Einecke, Reference Einecke2001) as the lines are clearer and the space between them seem to have diminished (Figure 4).

Figure 4. ‘La mort de Socrate’ by Jean-Francois-Pierre Peyron, 1788, Josslyn Art Museum, Omaha. Available online: https://www.joslyn.org/collections-and-exhibitions/permanent-collections/european/jean-francois-pierre-peyron-the-death-of-socrates/ (accessed 1 May 2021).

Socrates is placed on the right. He is at the Salience of the painting, dressed in bright light colours, while the Framing is also done by dark-dressed figures and a dark background.

The reading of the painting follows three lines (Einecke, Reference Einecke2001): (a) the first starts from the two lying background figures on the left and ends with the servant with the cup, indirectly guiding the observer's gaze to the companions of Socrates in the background and then back to the face of the philosopher; (b) the second starts from the lying figure on the floor and ends up at the raised hand of Socrates; (c) the third starts from the figure in red on the right and ends up at the raised hand of Socrates. Almost all the figures belong to the Salience, while the bright colours and the lines attract the viewer's gaze to a Given to Real reading.

1.4 ‘La mort de Socrate’, Jean-Baptiste Joseph Wicar

Figure 5. ‘La mort de Socrate’ by Jean-Baptiste Joseph Wicar, 1782–1792, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Available online: https://www.alamy.com/stock-image-drawings-and-prints-drawing-death-of-socrates-artist-jean-baptiste-162527971.html (accessed 1 May 2021).

The sketch by David's friend Wicar is a study depicting a multitude of figures inside the philosopher's cell (Figure 5). Socrates appears robust and sits on a couch. He holds the cup of poison with one hand while the other points in the sky. The expressions of his companions seem neutral. A diagonal from top left to bottom right indicates the direction of the light. Wicar's work and his relationship with David, as well as that of Peyron, reveal that the depictions of the ‘robust’ Socrates belong to a certain period (1787–1792) and may be influenced by Caravaggio's imitator.

2. Socrates takes the cup with the poison

In this typology Socrates is depicted receiving the cup of poison. His companions express their sadness with gestures and facial expressions. In some creations soldiers are also present. Almost all the artworks found belong to the 18th century.

2.1 ‘La morte di Socrate’, Salvator Rosa

Figure 6. ‘The Death of Socrates’, Salvator Rosa, 17th century, private collection. Available online: https://www.meisterdrucke.it/stampe-d-arte/Salvator-Rosa/839436/La-morte-di-Socrate.html (accessed 1 May 2021).

The works of Salvator Rosa are dominated by dark colours (Figure 6). The figure of Socrates occupies almost the entire left half of the painting, dressed in white, a contrast that aims to attract the viewer's eye. The three figures of Socrates' companions express their despair with their posture, while Socrates is depicted with an intense look that testifies to perspicacity - calm, strict and ready to drink the poison he holds in the cup.

In this illustration the cup with the poison is in the Centre of the painting and it is the element on which the viewer focuses, observing the whole figure of Socrates. The philosopher's gaze turns to his companions and calls the viewer to do the same through a vertical low perspective that gives the impression that Socrates is in an elevated position. Although Socrates is the central figure, the viewer is urged to observe all of the grief and despair with a strong emphasis on gestures (Langdon, Reference Langdon2011).

2.2 ‘The death of Socrates’, Cornelis TroostFootnote 3

In the representation of Socrates by Troost (1736), the painter attempts to draw elements from the ancient sculptures of the philosopher in order to realistically draw his characteristics. This is the only depiction that was found and faithfully bears both the face and the body type of Socrates according to the ancient sources of Plato and Xenophon. The figure of Socrates is projected through the bright colours of his clothes. This comes in contrast with the dark clothes of his companions and the dark background. Monumental gestures and expressions of pain are recorded only to companions close to Socrates. We notice that in this painting the farther away a figure is, the calmer it is represented.

3. Socrates drinks the poison

In the representations of this typology, Socrates holds the cup with the poison on his lips. In the earliest representation of those found, that of Dufresnoy (1650), he looks sideways at the skyFootnote 4. This scene is extremely rare and was found in only two paintings.

3.1 ‘La mort de Socrate’, Charles Alphonse Dufresnoy

In Dusfresnoy's painting (Figure 7) the depicted figures are located in a dark interior, which seems to be illuminated by two sources: a window in the background and another (implied) opening on the left.

Figure 7. ‘The Death of Socrates’ by Charles Alphonse Dusfrenoy, circa 1650, oil on canvas, Uffizi Collection, Florence, Italy. Available online: https://www.wikigallery.org/wiki/painting_216821/Charles-Alphonse-Dufresnoy/The-Death-of-Socrates (accessed 1 May 2021).

One of the figures, younger than the others and dressed in white, points to Socrates. The executioner behind Socrates wears a bright red colour, which puts the viewer in emotional charge due to the imminent death of Socrates. The blue figure with open arms seems to make a gesture of despair but could also indicate that Socrates is conceivably crowned (reminder of his restoration by future generations). The soldiers are part of the prison staff and instruments of the system that condemned Socrates.

The window high in the background and the presence of stairs on the right give the impression that the prison is below ground level. On the floor of the prison are scattered wooden objects that are probably handcuffs, a reminder of the tortured stay of prisoners. The viewer is invited to watch a scene placed in public social distance. The horizontal perspective is frontal and indicates the creator's intention for emotional involvement in what is happening, while the vertical perspective is equal, which seems to motivate the viewer to observe the complexes of the painting and not to subject them to accept effortlessly what they see.

The New is represented in the figure of Socrates and his mourning friends. It is the event that is imminent and expected. At the same time, in the lower half of the image, in the field of the Real, the characters of the protagonists are called to face an impending event, which they cannot avoid. At the Centre of the representation the two dead prisoners are placed in public view, a fact that makes death in prison a central issue. Socrates, however, is a decent prisoner who drinks the poison as if nothing is happening. The young man's gesture in white clothes may imply just that: no one would be watching right now (Wilson, Reference Wilson2007).

The viewer's gaze follows a path from the foreground to the background. From the scene with Socrates and the hemlock, the gaze is directed to the dead in the Centre of the prison and, finally, to the guards - representatives of the regime, which condemned the philosopher. Socrates defies bodily death and heads for eternity, while the shackles of the prisoners lie empty on the floor.

3.2 ‘Socrates drinking the Hemlock’, Antonio Zucchi

Figure 8. ‘Socrates drinking the Hemlock’ by Antonio Zucchi, 1767, National Trust, England. Available online: http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/960060.1 (accessed 1 May 2021).

Zucchi's artwork shows Socrates in the Centre of the view drinking the poison (Figure 8). The reading from the Given to the New begins with the two soldiers watching the scene, continues in the figure of Socrates and three of his mourning companions, and ends with the sad Xanthippe, who leaves the cell. The painter's intention is to project the figure of Socrates as the vectors (a) of the soldier's hand on the left, (b) the companion on the right and (c) of Xanthippe, all point to him. The painter, however, also focuses on the figure of Xanthippe, depicted in bright yellow clothes. Xanthippe seems so intense; however, none of the depicted participants turn their eyes to her.

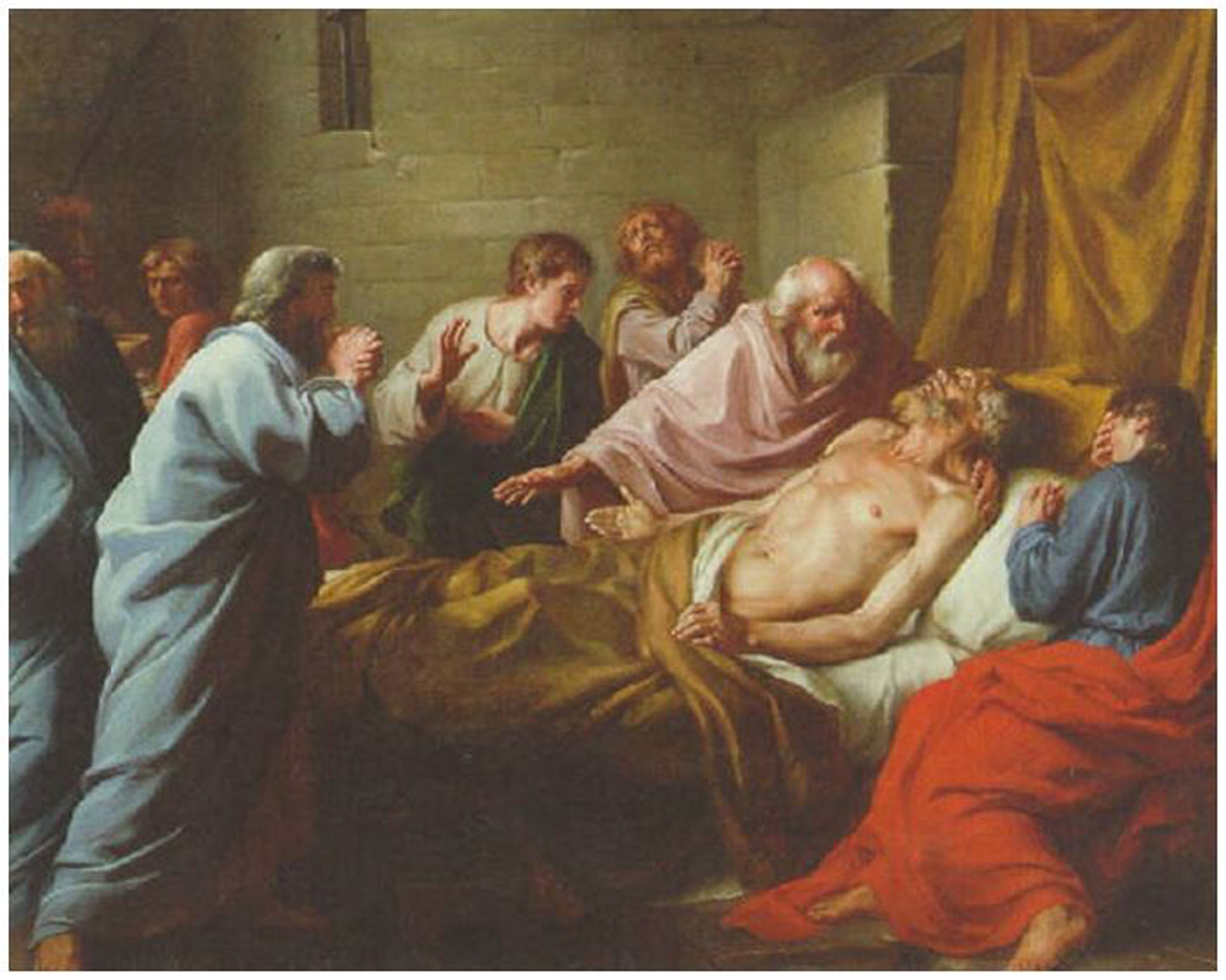

4. The ‘dying’ or ‘dead’ Socrates

The subject matter of this typology can be found in artworks from 1750 onwards. Socrates is usually depicted old, lying down and half-naked while almost always a figure is found on his headrest (probably Crito) holding his head among his companions.

4.1 ‘La mort de Socrate’, Michel François Dandré-Bardon

In Dandré-Bardon's drawing (Figure 9), Socrates is seated in the Centre of the image while those around him are in great distress. Many figures create different complexes with the unique theme of mourning. The figure of Socrates seems ascetic, quite weak and depressed. This is a more human depiction of the philosopher, who has chosen not to escape and it seems that this path is painful. Socrates' gaze avoids the observer, turning upwards (Ideal) and seems to ignore even the small children on his left.

Figure 9. ‘La mort de Socrate’ by Michel François Dandré-Bardon, 1749, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/343539 (accessed 1 May 2021).

The existence of numerous figures around Socrates and his eye contact with some of them creates an important connection of Salience and Framing, turning the observer's gaze to them. In this way, the impact of Socrates’ death on those around him is also brought to the fore.

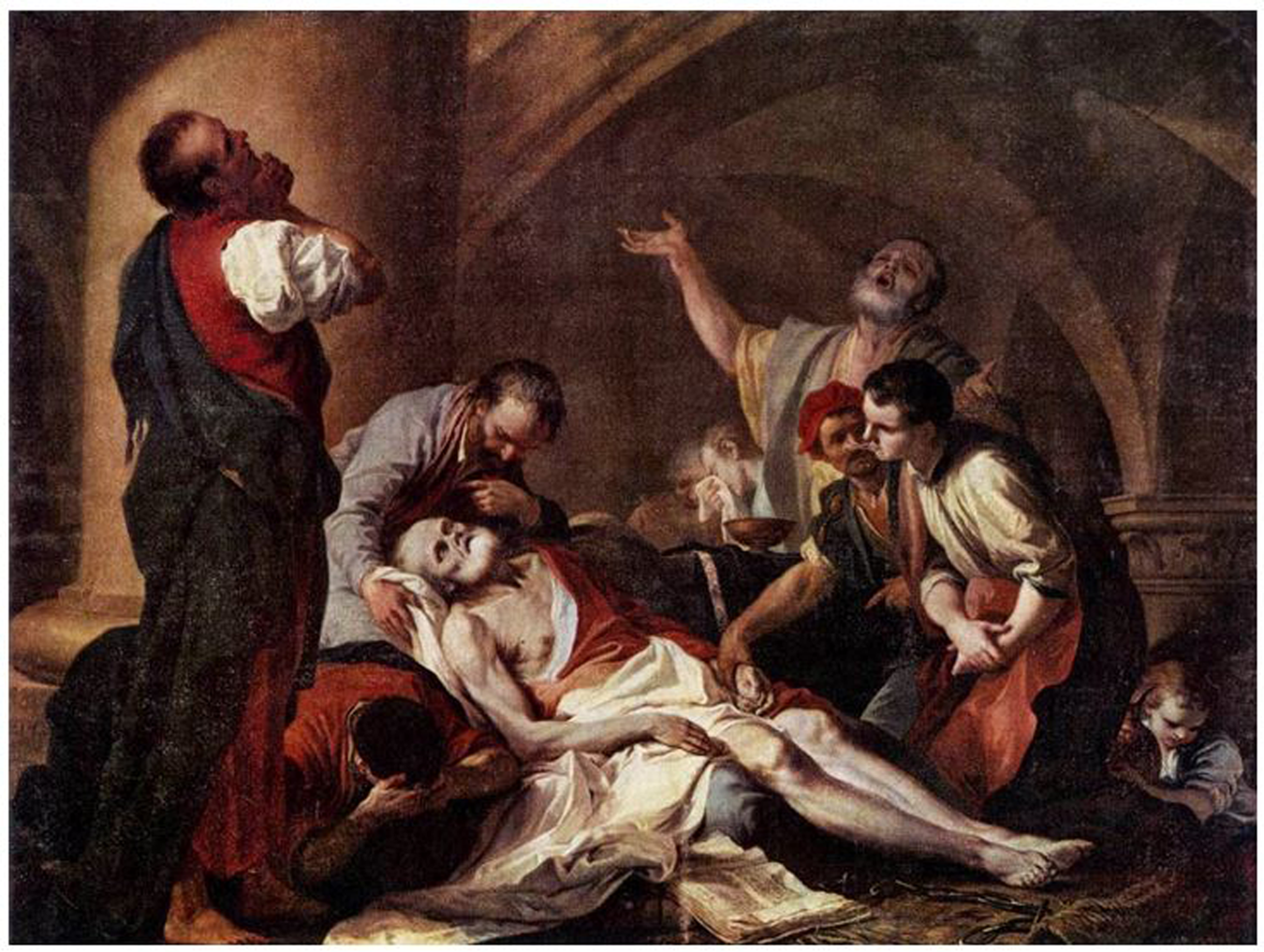

4.2 ‘Mort de Socrate’, Jean-Baptiste-Henri Deshays

Figure 10. ‘Mort de Socrate’ by Jean-Baptiste-Henri Deshays, 1760, Private collection. Available online: https://www.lot-art.com/auction-lots/Jean-Baptiste-Henri-Deshays-Colville-1729-1765-Paris-The-Death-of-Socrates/101propertyfroma-jean_baptiste-05.12.19-christie (accessed 1 May 2021).

In Deshays's drawing, Socrates is depicted in the Centre, with his head supported by Crito on the right (Figure 10). At the bottom of the image a figure holds tightly Socrates’ hanging hand, while at the Framing of this complex picture two figures on the far right and left are looking at Socrates, so that the lines of their gazes converge towards the philosopher. In the background there are two figures discussing in an intense style that is evidenced by their close personal distance and gestures. The death of Socrates (Salience) motivates the viewer to focus on the impact of this event on those around him (Framing).

4.3 ‘La mort de Socrate’, Francois Boucher

Francois Boucher's painting (Figure 11) depicts a complex of figures through which Socrates can hardly be distinguished. His companions are mourning around him inside the prison cell, while some military guards can be seen in the upper right. The dense framing of Socrates by his companions indicates how dear Socrates was and that the Athenians made an irreparable mistake in condemning him to death. Some figures closest to the viewer (bottom left) are depicted in dark colours to be considered as Framing, as the Salience of the painting is the dying Socrates. The representation of Socrates as a young man is not very common and perhaps the artist's intention is to intensify the mourning of the loss by depicting a dying young man.

Figure 11. ‘La Mort de Socrate’ by Francois Boucher, 1762, Louvre, Paris, France. Available online: https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010054818 (accessed 1 May 2021).

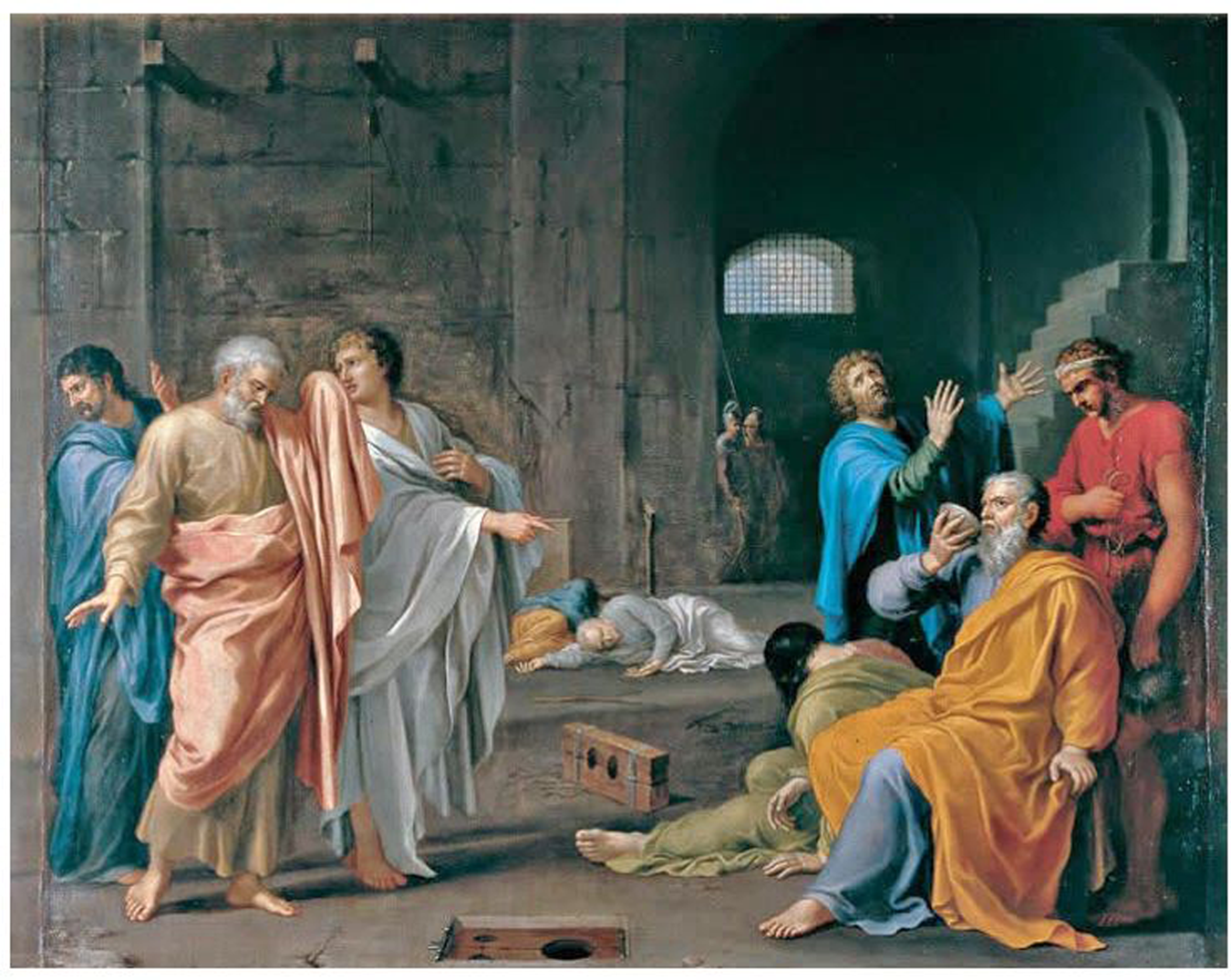

4.4 ‘La mort de Socrate’, Jacques-Philippe Joseph de Saint-Quentin,

In 1762, Saint-Quentin won the competition of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture of France with this painting (Figure 12). The painter captures the moment when Socrates begins to feel the effect of the poison.

Figure 12. ‘The Death of Socrates’ by Jacques-Philippe Joseph de Saint-Quentin, 1762, Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jacques-Philip-Joseph_de_Saint-Quentin_-_The_Death_of_Socrates_-_WGA20664.jpg (accessed 1 May 2021).

Socrates is depicted in the Centre, dressed in yellow and white, so as to attract the viewer's eye (Elliot & Maier, Reference Elliot and Maier2007; Elliot, Reference Elliot2015). The Salience is completed with two mourning companions but also with the cup lying on the floor. The representation is framed by two complexes in dark colours: (a) on the left, a group of companions holding writing materials, and (b) on the right, a group of kneeling soldiers.

In this representation the fact of the imminent death of Socrates has led to the suffering of those present. Both the companions and the soldiers bow their heads and look away. The event is irreversible and Socrates with a characteristic gesture urges his companions not to mourn. The artwork focuses on the effect of Socrates' death on those around him and it seems that a ‘dying’ Socrates emotionally excites the observer more than an already dead SocratesFootnote 5.

4.5 ‘La mort de Socrate’, Jean-Baptiste Alizard

With this painting (Figure 13) Alizard won the second prize in the competition of the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. The representation seems strongly influenced by the depictions of the Apostasy. Socrates is depicted with open arms. The cup with the poison is upside down and empty at the edge of the table and the observer does not to notice it immediately, just like the empty chains hanging next to the philosopher's bed.

Figure 13. ‘La Mort de Socrate’ by Jean-Baptiste Alizard, 1762, Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mort_de_Socrate-Alizard.jpg (accessed 1 May 2021).

Socrates is located in the Centre of the representation, the Salience of which is completed by five other figures: (a) a kneeling figure in red records the unfolding events, delivering them to eternity, (b) a young man embraces Socrates with intense emotion, (c) a companion supports him while looking at two other figures, one of which (d) seems hidden and crying and the other (e) hugs the previous one raising his hands in despair while, on the far left, some guards watch the scene. Once again, Socrates is presented as a person whose death has a significant impact on his environment. In this way the observer realises that this is not a conventional death, but a reminder of a transcendence.

4.6 ‘The Death of Socrates’, Giambettino Cignaroli, second half of the 18th century

Figure 14. ‘The Death of Socrates’ by Giambettino Cignaroli, second half of the 18th century, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giambettino_Cignaroli#/media/File:Giambettino_Cignaroli_-_The_Death_of_Socrates_-_WGA04876.jpg (accessed 1 May 2021).

Cignaroli's artwork is perhaps the most ‘dark’ depiction of the death of Socrates (Figure 14). The ‘robust’ Socrates of David and Peyron is now presented as a bony and tormented old man dressed in white. His chains are thrown on the floor, while around him the expressions and gestures of his mourning companions are extremely intense. The whole set of figures belongs in the Salience of the representation. A wide diagonal runs across the painting from bottom right to top left (from the Real-New to the Ideal-Given), which is delimited by the body of Socrates, Crito holding his head, and the movements of the two upright figures on each side. This section of the painting includes all the action. This is another depiction of Socrates' death which focuses on the reactions of his companions.

4.7 ‘La mort de Socrate’, Jean-François Sané

Figure 15. ‘La mort de Socrate’ by Jean-François Sané, 18th century. Available online: http://www.artnet.com/artists/jean-fran%C3%A7ois-san%C3%A9/the-death-of-socrates-cXwxzmSZ9bZTCC7BlWX6EA2 (accessed 1 May 2021).

Sané's oil painting (Figure 15) belongs to the second half of the 18th century and shows Socrates dying or dead and surrounded by his distressed companions. The vectors of crossed arms, heads facing the sky and lines of gaze gather in the figure of the philosopher and, along with a set of bright colours, attract the observer's gaze. The important detail in the background is the employee with the cup of poison leaving the cell. This is perhaps the figure from which the reading of the painting begins.

4.8 ‘La mort de Socrate’, Joseph Félix Henri Auvray

Figure 16. ‘La mort de Socrate’, Joseph Félix Henri Auvray, 1800, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Valenciennes, Paris. Available online: http://www.hellenicaworld.com/Art/Paintings/en/FelixAuvray.html (accessed 1 May 2021).

In the painting by Auvray (Figure 16), Socrates is a young man, strong and shaved, who dies in an attic (Wilson, Reference Wilson2007). Next to him there is no crowd of mourning companions but a few friends. The figure of Socrates dominates the Centre of representation, because of his large size and the light shades of his skin and clothes. The portrayal of Socrates as a young man alludes to the freshness and militancy of youth, which one must be willing to sacrifice for his/her ideas.

4.9 ‘La Mort de Socrate’, Jean-Jacques-Augustin-Raymond Aubert

Figure 17. ‘La Mort de Socrate’ by Jean-Jacques-Augustin-Raymond Aubert, private collection. Available online: http://www.hellenicaworld.com/Art/Paintings/JeanJacquesAugustinRaymondAubert/en/PartJJARAubert0001.html (accessed 1 May 2021).

A student of Peyron, Aubert created a quite different painting (Figure 17). Socrates is portrayed leaving his last breath in a room of a house and not in a cell, surrounded by only two figures. One of them could be Xanthippe, although it is not clear whether it is a male or a female. The second figure, in the foreground, may represent a son or a young companion. On the table next to the bed there is the cup of poison, an amphora and a lamp as the only source of light. The light does not fall on Socrates’ face, thereby keeping him in the shady part of the image, perhaps as a reminder of death. The hand of Socrates touches the head of the young figure, symbolising the heredity of the philosopher's teachings to the young.

Epilogue

By reviewing the works of art that refer to the death of Socrates, both in terms of structure and typology, the teacher can use them as a stimulus for reflection and knowledge. Additionally, he/she can use in teaching common elements emerging from the semiotic analysis. These elements can be summarised as follows:

Although Socrates is the main theme of the artwork, the observer's attention cannot escape from the Framing of the mourning companions. Socrates talks, teaches, holding or drinks the poison calmly without a trace of emotional charge. This turmoil of Socrates by itself cannot make the observer think about the importance of overcoming the death. This is achieved through the suffering of his companions, in which the observer is invited to participate, without being submitted to it. This fact highlights the intention of the artist to project the revolutionary nature of the depicted event.

The narration of the events from left to right, from the Given to the New begins with groups of companions (sometimes guards included) and ends with the figure of Socrates. This course signifies the change in the mind of the observer after the effect of the act of Socrates, because it is right and reasonable to mourn the loss, but the soul can win immortality.

As a final comment, we must point out that the representations of Socrates portray a hero who put the common interest above the individual, spoke of objective morality and defended his views with his life, remaining a free spirit in the face of a tyrannical power. Socrates, as a sage and a revolutionary -although if he lived he might have abhorred such descriptions- was an ideal role model for the era of Enlightenment. After all, the radicalism of the French Revolution will project, a few years later, the model of the struggling man. And in this case, the artworks will then present Socrates competing in court (Wilson, Reference Wilson2007).