Designed for the “instruction and amusement of young persons,” the 1792 edition of the children's book Evenings at Home offered a collection of games, lessons, and role-plays for middling British families looking for educational entertainment. Aptly titled “The Colonists,” one chapter revolves around building a colony for the British Empire. It begins, “‘Come,’ said Mr. Barlow to his boys, ‘I have a new play for you. I will be the founder of a colony; and you shall be people of different trades and professions coming to offer yourselves to go with me.” The children proceed to make their selections, with their father offering praise and criticism. To the boy choosing the occupation of farmer, Barlow warns that he “must be a working-farmer, not a gentleman farmer.” Building a colony was not for the idle. He accepts the tailor on the grounds that “though it will be some time before we want holiday suits, yet we must not go naked,” but rejects the weaver, lawyer, and silversmith as skills the colony will not immediately need. The doctor interested in botany receives high praise, as does the schoolmaster. As the game proceeds, the children are encouraged to imagine life as colonists, facing the challenges of an unfamiliar environment and spreading the British Empire. Success is assumed, as is the colonists’ innate superiority.Footnote 1

Such exercises were much more than simple fantasies. By the mid-1760s, the majority of the people in the British Empire were not of European descent; by 1820, the empire claimed dominion over a quarter of all humans. Thus, the children born into the critical latter half of the long eighteenth century—between the Seven Years’ War and the accession of Queen Victoria—would inherit, build, shape, and bequeath the largest empire ever known. They would also transform the empire from a predominately mercantilist model driven by private interest into the more centralized, government-led political powerhouse of the Victorian and Edwardian ages.

Adult engagement with the empire has long been examined from a variety of angles, ranging from conquest to consumerism. In more recent decades, scholars have taken an increased interest in how the empire affected British society and culture. Often grouped as “new imperial” historians, these scholars have argued that imperial experiences profoundly altered British domestic culture, generating new ideas about gender, race, and nationality (to name just a few).Footnote 2 Criticism has not been in short supply, with most detractors insisting that imperial experiences did not deeply penetrate the thinking of ordinary Britons.Footnote 3 Almost all of the debate, however, has focused on the Victorian and Edwardian eras, periods in which the established empire could be taken for granted.Footnote 4 The underexplored long eighteenth century—roughly from the Glorious Revolution of 1688 to the accession of Queen Victorian in 1837—offers relatively fresh ground, because it was a period of rapid expansion in terms of both imperial growth and public participation in national affairs. This period witnessed Britain's emergence as a great imperial power, and the accompanying discussions and anxieties ran deep into British society.

I explore this subject through an examination of ways children in Britain engaged with the empire and the wider world in which it operated. In recent decades, studies of eighteenth-century childhoods have flourished, with John Locke's 1693 Thoughts Concerning Education, in which he asserted a tabula rasa approach to children, widely interpreted as launching a revolution in the history of children and childhood.Footnote 5 Yet the connections between empire and childhood in pre-Victorian Britain remain underexplored, particularly questions about how children engaged the world they would be expected to govern.

What this article offers is a better understanding of both imperialism and childhood in Britain. In the first half I focus on why and how children engaged with the empire and world outside of Europe. Learning about these subjects took place predominately outside of formal schooling; therefore, the objects and venues discussed here were designed to feed consumer demand—if not that of children, then certainly of their parents. Domestic learning was fundamentally different from formal schooling in that it was overwhelmingly led by women, highly interactive, and deeply personal. Content creators, often promoting their credentials as parents, understood this and catered to it. Certainly, the empire did not dominate the lives or education of children in Britain. Awareness of the empire was for those in Britain, as it is in almost any imperial center, mainly a privilege (unlike the African enslaved to work a Jamaican plantation or the Cherokee woman displaced from her homeland by colonial expansion). In consequence, the choice of the British middling and elite parents to educate their children about the empire and wider world it engaged suggests genuine belief in the subject's relevance. In short, children of the age became imperialists not by accident or designed statecraft but by common consent.

I then examine what children learned—or, more precisely, what adults wanted them to learn. The games, publications, and exhibitions that attracted children and their parents all served as mechanisms to reinforce messages about the importance of Britain's roles in the world and to train children to engage with it as observers and, ultimately, masters. Such experiences further demonstrate how ordinary people construct national and racial identities through everyday activities.Footnote 6 Crucially, however, discussions of the empire and imperialism were neither monolithic nor uncontested, as many of these experiences also sought to teach children to be critical of Britain's conduct in the world.

The Usefulness of Knowing the Empire

British children received unprecedented attention during the long eighteenth century. Despite residual medieval laws that allowed a girl to be married at seven and have that marriage consummated at twelve, eighteenth-century commentators depicted childhood as a lengthy period extending well into one's twenties—at least for the middling and elite ranks who had that luxury.Footnote 7 Critically, educational theorists and their practitioners almost universally accepted the notion that children were malleable, and so Britons set about organizing childhood, like other aspects of society, for the benefit of the individual child, the family, and society. In consequence, both parenting and childhood were highly prescriptive experiences.

At the heart of the new notions of childhood was the Enlightenment. The likes of John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau were emblematic and influential in their representation of children not as tainted vessels of Original Sin but as blank slates upon which parents and other adults could write their values and aspirations for the betterment, or detriment, of society. These perspectives permeated mainstream thinking about childhood.Footnote 8 As William Darton representatively remarked in the opening lines of his popular collection of moral tales, “Minds of children are as white paper, from which erroneous impressions are difficult to erase . . . in this view doth the compiler of the following pages behold the minds of infants.”Footnote 9

This conception of childhood was part of the embrace of “improvement” and its sibling, “progress,” that dominated eighteenth-century Britons’ outlooks. Evidence of the improving mindset abounds. In what Jan de Vries has dubbed the “industrious revolution,” Britons drove the rise of a consumer society by working longer and harder to afford more and higher-quality goods and experiences—often for their children.Footnote 10 Learning was a pillar of self-improvement and progress, and the consumer market obliged with an explosion of printed materials, exhibitions, and other educational opportunities for children and adults.Footnote 11

So-called useful knowledge received priority, and from the early eighteenth century, useful knowledge increasingly included awareness of state affairs and the political economy.Footnote 12 Newspapers flourished, as did an emphasis on the value of numeracy. During the Seven Years’ War, public interest in national affairs extended to include the empire—a shift accelerated by the American Revolution and subsequent wars with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France.Footnote 13 Thus, while a London gang in the 1720s confused East and West by assuming the name Mohacs but styling themselves as Asian Moguls, Britons a half-century later openly debated American Indian policies with the aid of a host of articles and maps found in newspapers throughout the country.Footnote 14

The shift toward empire increased claims of the utility of travel accounts, geography, and recent history. Although publications in these genres were available before the Seven Years’ War, they proliferated in the adult reading world afterward, featuring heavily in private collections and the book clubs and lending libraries mushrooming across the country.Footnote 15 Authors and publishers were quick to assert the benefits for children as well. As one author characteristically remarked, geography and history, like good household management, were “useful” to children—far better than “repeating the little tales that are frequently told them for their amusement.” Moreover, she continued, because “Geography and History enlarge the mind more than any other studies . . . they cannot be begun too early” and the subjects are “by no means dry and irksome talk to children; on the contrary, they have a pleasure in looking over a map, and are rejoiced if they happen to discover any place they have ever heard of.”Footnote 16

By the 1780s, Britain was awash with publications for children that engaged with the empire and the peoples and places connected to it. This development suggests that parents, forever seeking opportunities for their children's improvement, came to a consensus that an understanding of the empire and the world would be a future advantage for children. To be clear, this was not the explicit national imperialism that bordered on propaganda and prevailed at the height of the British Empire a century later. Rather, carefully selected information about the empire was the core of a broad desire to understand the world and its inhabitants generally—information widely marketed and accepted as useful to children. In fact, the term “useful” predominated in the titles, prefaces, and advertisements of these books. A typical title, The Young Gentleman's and Lady's Magazine; Or Universal Repository of Knowledge, Instruction, and Amusement, was a juvenile magazine launched in 1799 to serve “as an useful auxiliary to public and private tuition.” Like other geographies and encyclopedic collections of aimed at children, the magazine interspersed information about the empire among other topics. Alongside articles on botany, morals, and astronomy were such pieces as British tiger-hunting in India, “Descriptions of the celebrated Falls of Niagara,” accounts of the slave lands of West Africa, “Anecdotes of Mahometan Justice,” and the “Political Situation of Egypt.”

Critically, formal schooling framed little of the discourse on the British Empire. Although changing during the eighteenth century, formal schooling outside religious education primarily remained the preserve of middling and elite boys, and curricula continued to emphasize classics and mathematics over the imperial political economy (or anything contemporary, for that matter). Therefore, for children as for adults, information about the empire and wider world was overwhelmingly conveyed informally through reading, conversation, and visits to dedicated spaces of display.

The informality of education in the nontraditional subjects in which the empire appeared meant that the bulk of instruction took place in the home or as an extension of domestic life, thereby thrusting women into central roles. Some men participated, just as they joined in the household economy and domestic life in general, but women were prevalent as authors and educators.Footnote 17 The domestic context of education about the empire and its place in the world also meant that girls were expected to participate and benefit. In her popular 1793 Mental Improvement, Sarah Green advocated that adolescent girls devote at least “one morning in a week between the study of geography, and the reading of voyages and travels.”Footnote 18 Women and girls were regular visitors to the museums, performances, and exhibitions referred to here, and strict divisions by gender in children's literature would not emerge until the Victorian era.Footnote 19 For instance, the Young Gentleman's and Lady's Magazine, first published in February 1799 and, according to its prospectus, “expressly devoted to the young of BOTH SEXES,” regularly included pieces advocating for greater rigor in girls’ education and against gendering subjects. Its first issue included an article “On the Union of male and female Studies,” written in the guise of a father's grateful letter to the editors: “Whatever has been hitherto published as appropriate for ladies has been the grossest insult to the understanding of the sex. They [women] have to be amused with ridiculous stories, as if they were only children of a larger growth . . . without the least attempt to render them rational beings and intelligent companions.”Footnote 20 Such thinking aligned closely with leading contemporary commentators on female education, such as Mary Wollstonecraft and Hannah More, who vehemently argued in favor of providing more equal educations to liberate women from what Wollstonecraft described as an oppressive, perpetual “state of childhood.”Footnote 21

Ultimately parents, typically mothers, were expected to sift through the wide range of materials and experiences on offer for the benefit of their children. Under the heavy weight of responsibility for their children's development, parents and other adults raising children faced considerable pressures. After all, critics made clear, unruly children who later became immoral, lazy adults were products of poor parenting. The British solution throughout the long eighteenth century was overwhelmingly to follow Locke's advice in favor of regimentation, rather than Rousseau's calls in Emile for a less restrictive and self-directed childhood.Footnote 22 The popular educational writer Eleanour Fenn, who wrote under the pseudonyms of Mrs. Lovechild and Mrs. Teachwell from the 1780s to the 1810s, is just one example of how commentators relentlessly held parents accountable. In the dialogue “The Foolish Mother” between a “Mrs. Steady” and “Mrs. Giddy” in her publication The Juvenile Tatler, Fenn characteristically chastised indulgent mothers. Mrs. Giddy bemoans her badly behaved children and seeks advice of Mrs. Steady, complaining, “My boys are always crying; yet I give them every thing which they ask for—how do you manage.” Mrs. Steady, “smiling,” responds bluntly, “You must excuse me: it is your own fault that your children are so refractory.” She follows with a description of her own strict rules that make her children content and thriving.Footnote 23

Therefore, although children's literature blossomed during this period, children's reading was typically heavily regulated.Footnote 24 Book prefaces, advice columns, and advertisements for games and entertainments invariably addressed parents. This is not to suggest that children did not directly participate in consumer society. Anecdotal evidence suggests that children had some pocket money, and guidebooks sought to teach them to be responsible consumers.Footnote 25 However, the books and experiences considered in this study were considerably more expensive than paper dolls and candy, and the producers assumed their audience consisted primarily of parents or, to a lesser extent, other adults vested in a child's upbringing. That parents took their responsibilities seriously is evidenced by the market-driven growth in child-orientated objects and experiences. Books for children, print space dedicated to parenting advice in magazines, and public spaces that catered to children proliferated dramatically during this period.Footnote 26

Some parents handled the challenge themselves. Anna Larpent, the daughter of a diplomat and wife of the official inspector of plays, ably handled the task, taking great care in curating her children's educational experiences, whether in the form of visits to exhibitions or reading. For example, in a diary entry from May 1796, she described spending part of her day “writing extracts from Thumberg's travels which may amuse or instruct my children on the cultivation of tea—rice—soy—and natural history.”Footnote 27 Few parents were as well read as was Larpent, however, and, as the growth in choice accelerated, educational commentators and authors presented themselves as guides. Women especially flourished in this role. Their strategy closely followed that in the genre of domestic guides and cookery books largely written by and for women that established itself a few decades earlier.Footnote 28 British readers were inundated with innumerable choices—whether in the form of competing curry recipes or geographical accounts of Asia—and these female authors presented themselves as trustworthy interpreters, selecting only what they would use in their own homes. As Maria Rundell representatively remarked in what would become one of the most successful cookery books of her generation, her recipes and advice could be relied upon because they “were intended for the conduct of the families of the authoress's own daughters, and for the arrangement of their table.”Footnote 29 In an equally popular juvenile geography that enjoyed at least twenty-two editions from its first publication in 1790, the author used similar language, choosing the title Geography and History: Selected by a Lady, for the Use of Her Own Children. “The following pages were originally intended solely for the use of my own children,” she assured fellow parents in her preface, “and would never have been presented to the public eye” if she had not believed other children would benefit.Footnote 30

Few guides were more prominent and treasured than Sarah Trimmer. The Edinburgh Review declared that Trimmer had become “dearer to mothers and aunts than any other author who pours the milk of science into the mouths of babes and sucklings.”Footnote 31 Trimmer launched her Family Magazine in 1788 as an aid to parents “who may be at a loss to make a proper choice of books for themselves . . . It will be the business of the Editors of this work,” she informed them, “to make a selection for them from approved authors.” After all, “Every parent who has a proper regard for their offspring, is desirous of having them taught [to read]”; however, lack of supervision led to what she labelled “a loose kind of reading,” or the indulgence in immoral and frivolous works to the detriment of the child.Footnote 32 She was adored as a national treasure. Upon her death in 1810, readers wrote to the Gentlemen's Magazine calling for a lasting tribute for her memory, with one even proposing the erection of a monument in St. Paul's Cathedral, the hefty expense for which “would be raised almost as soon as the notice of subscription was made public.”Footnote 33

Parents’ never-ending quest to provide their children with advantages through learning created a marketplace of potential educational opportunities. As the resources of time and money were limited, commentators warned audiences of the wasteful expenditure of either. These restraints translated into selectivity. Therefore, what enterprising commercial producers provided and parents consumed for their children is extremely telling about what they believed mattered to successfully raising a child. The world and the British Empire's place in it were key elements of what increasingly made the cut.

Spaces for Engagement

The growing marketplace of improving experiences for middling and elite British children supplied a host of opportunities in the form of exhibitions, performances, games, and literature to learn about the world and the empire's roles in it. Reading was the most prevalent form. Middling and elite homes were awash with the latest news and commentary on imperial affairs via the nearly sixteen million copies of newspapers that were churned out annually by the 1780s.Footnote 34 While examples of children reading newspapers are scarce, visual representations of children being present in rooms with adults reading are not. Moreover, domestic reading practices—often aloud and discussed by adults at the breakfast and tea tables or by the fireside—offered second-hand exposure for children.Footnote 35 Abigail Frost, the daughter of a Nottingham grocer, read her father's newspapers, noting in her diaries news of the American Revolution.Footnote 36 Education commentators also recommended some adult books as suitable for children; Sarah Green in her 1793 Mental Improvement for A Young Lady called Oliver Goldsmith's History of England “certainly the best” and similarly endorsed William Guthrie's New Geographical, Historical and Commercial Grammar, which is packed with information about the empire and peoples connected to it.Footnote 37 Jane Austen read the former in her teens, commenting favorably upon it.Footnote 38

The engagement of children, however, was not an afterthought. Literary experiences were regularly tailored for them. Children's literature emerged in the mid-eighteenth century, just as popular interest in the empire began to develop. John Newbery, whose publishing house paved the way for children's literature as a sustainable genre, produced his first children's book in 1744. Other publishers followed suit, and within a few decades, the market was awash with juvenile literature. Booksellers throughout the country increasingly included these titles in their catalogs. Some, such as Samuel Gamidge in Worcester, sold a range of juvenile titles including his own, such as his Collection of the most approved Entertaining Stories. Calculated for the Instruction and Amusement of all the little Masters and Misses of the British Empire. Footnote 39 While moral tales, guides to manners, and religious instruction initially abounded, publishers soon broadened their attentions to include geography and history.Footnote 40 The shift was accretive over several decades. For example, the first children's magazine, Newbery's Lilliputian Magazine in 1751, reads as a collection of fictional tales and moral advice for children, but later children's magazines, such as the Juvenile Magazine in 1788, closely mimicked the format of popular adult magazines, with an emphasis on nonfiction in sections covering news, geography, history, and science.Footnote 41 These later magazines were packed with articles detailing economies, natural history, and cultural information about the peoples and places where Britain traded and ruled. The change is also evident within the same titles. Geography for Children, one of the earliest books aimed at children, evolved in its 22 editions between c. 1740 and 1800 to include maps of the territories connected to the empire as well as descriptions of the people who lived in them. “The Character” of the American Indians, for example, first appeared in the 1780 edition.Footnote 42

Relegating to the domestic sphere children's learning about the wider world and the empire's roles in it meant the information was conveyed in child-centered ways that were unconventional in formal education. Educational writers like Fenn and Trimmer recommended and assumed, for example, a setting of a parent (usually a mother) with one or a small group of her children and designed the content accordingly. The fictional mothers in these accounts, serving as role models for parents as much as for children, were forever looking for opportunities to convey or test their children's knowledge, often doing so in impromptu instances at breakfast or on rainy afternoons. In one account, the setting was the dining table, where children took turns reading and discussing letters from an older brother traveling across North America. Upon learning that he had been bitten and nearly killed by a rattlesnake, the unflappable mother used the occasion to describe and discuss with her children the various types of reptiles her son might encounter.Footnote 43

Contemporaries also claimed that the shift from rote learning in formal classrooms to interactive learning in intimate settings fostered what they called “understanding,” or what modern commentators might describe as “critical thinking.” The female author of Geography and History purposely styled her book as a series of questions and answers with accompanying problems, not unlike a modern textbook, which the author hoped would prevent children from learning the information “by wrote.” Games such as “The Colony” in the female co-authored Evenings at Home encouraged the creation of scenarios in which children would solve problems by applying their knowledge. Yet children remained guided throughout the experiences by a parent. Unlike the Boys’ Own adventures of the late Victorian and Edwardian ages, in which children often gallivanted across Britain and its empire experiencing adventures free of parents,Footnote 44 authors of this period decidedly placed children with guiding adults. In juvenile travel accounts that children might read independently, a fictitious adult was in the pages to direct the adventure—either in the form of a narrator speaking directly to the reader or in the character of a mother to the children in the story. Even fictional children were regulated to ensure their absorption of useful knowledge.

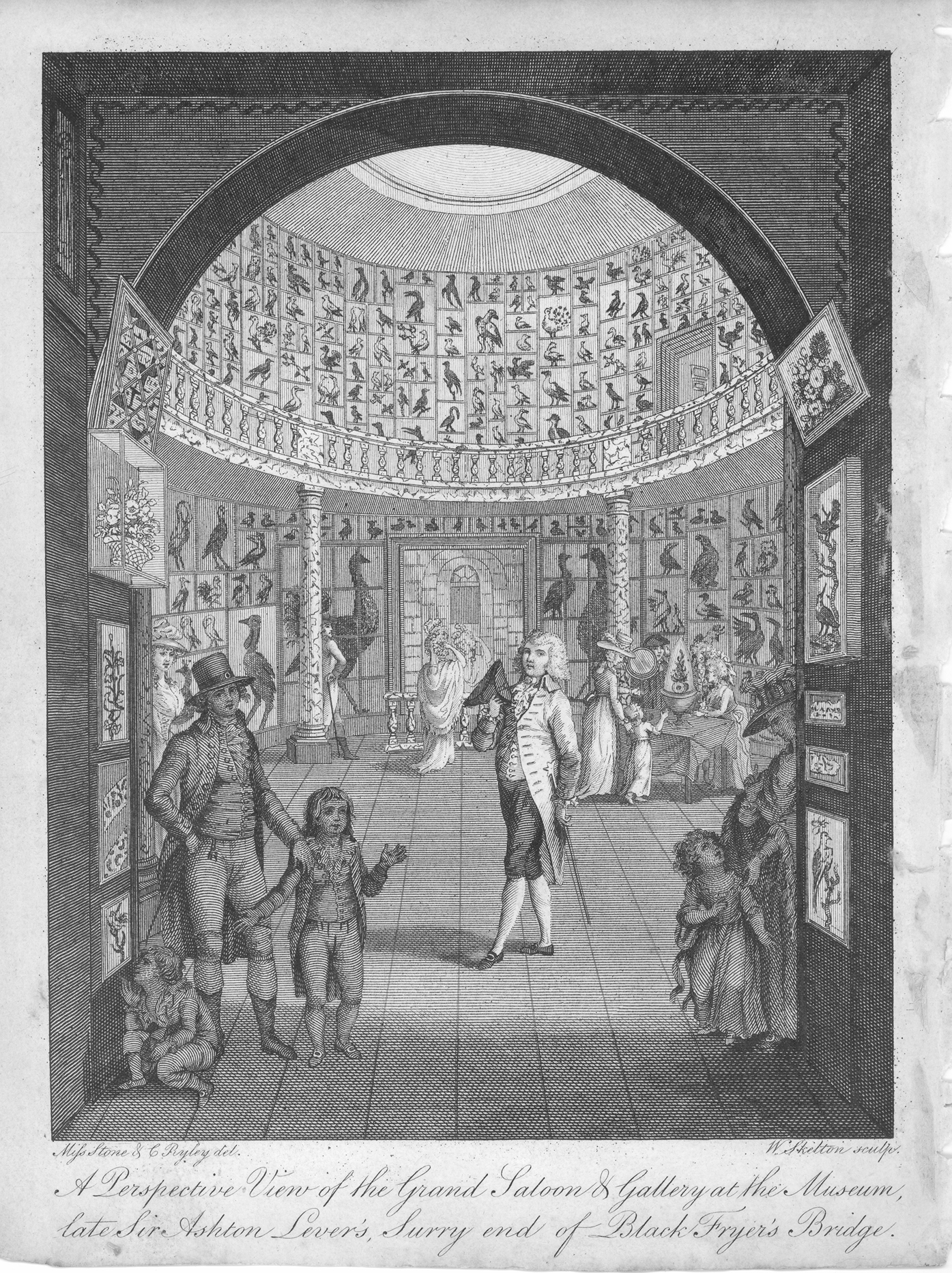

Like the printed material for children, public exhibitions also emphasized claims of usefulness to children. Children, particularly adolescents, could be found in a variety of both metropolitan and provincial assemblies, elite shopping venues, pleasure gardens, theaters, and concerts. Their inclusion in these spaces reflected the wider trend in middling and elite Britain to embrace children in polite society.Footnote 45 Museums especially expressed a keen sense of duty to education and children. When the trustees of the new British Museum, founded in 1753, considered closing its gardens to children, a debate ensued in which the institution's overall obligation to the next generation became clear. “The Consideration of the helpless state of Childhood hath ever induced the World to offer it its protection, that the Blossom might ripen into future Fruit,” the trustees concluded. The museum would continue to allow access to children, “it being of far more importance to give the means of Health and security to Children, than to grown Peoples, who can protect themselves.”Footnote 46 The British Museum was not unique in this regard. Sir Ashton Lever's Leverian, sometimes referred to as the Holophusicon (see figure 1), was the British Museum's main London competitor, and it was among the first British institutions to offer family rates and actively encourage children to visit.Footnote 47

Figure 1 Frontispiece of A companion to the museum, (late Sir Ashton Lever's): removed to Albion Street, the Surry end of Black Friars Bridge (London, 1790), illustrating the Grand Saloon and Gallery of the Leverian. Sir Ashton Lever welcomes a middling family to the museum. Author's image.

Open to the public and marketed as educational experiences, the leading museums became the archives of the nation, sources of national pride, and major tourist destinations. The popular guidebook The Ambulator declared that “of all the public structures that engage the attention of the curious, the British Museum is the greatest.”Footnote 48 Carl Moritz, a German visitor to England in 1782, was impressed as much by the diversity of people he saw in the museum as he was by its exhibits. “The visitors were of all classes and both sexes, including some of the lowest class,” he noted, “for since the Museum is the property of the nation, everyone must be allowed the right of entry.”Footnote 49 Caroline Lybbe Powys, the daughter of an Oxfordshire physician, was among the visitors, coming to the British Museum for the first time as a girl in 1760. Particularly fascinated by the ethnographic and natural history exhibits, twenty-six years she later toured the collections with her eleven-year-old daughter, an experience, along with their visit to the nearby Leverian, which “highly entertained her.”Footnote 50

Like printed materials for children, exhibitions heavily emphasized their instructional benefits over mere entertainment. These were opportunities for useful, personal improvement. In the British Museum, ethnographic artifacts received disproportionate exhibition space as well as attention in guidebooks and the surviving comments from visitors.Footnote 51 As the European Magazine explained in a 1782 review of the Leverian, these exhibits were not designed to entice fanciful notions; instead, “all conspire to impress the mind with a conviction of the reality of things.” While “descriptions of the enchanted palaces of the Genii, the Fairies, and the other fabulous beings of the eastern romance, though they amaze for a moment, have a sameness and an improbability that very soon disgust,” at the Leverian “all is magnificence and reality. The wandering eye looks round with astonishment, and, though almost willing to doubt, is obliged to believe.” Together, these objects conspired to virtually transport visitors across the globe: “As [the visitor] proceeds, the objects before him make his active fancy travel from pole to pole through the torrid and through the frigid Zones.”Footnote 52 The result, the Morning Post asserted, was “a most useful school of knowledge . . . where both our youth, and even old age, might receive instruction.” Thanking Lever for his service to “succeeding generations,” the writer continued, “What father would not wish his son to be contemplating the works of the Deity, in your museum, rather than spending his time in the debaucheries of the age?”Footnote 53

Learning about the empire and the world in which it operated was a collaborative process: parents were expected to be with their children at every turn. Formal exhibition spaces required it for entry; books and games assumed parents were on hand to encourage children to think critically and ensure they arrived at the desired conclusions. As with the history of children in general, comprehensive and detailed responses to the materials examined here are impossible to retrieve,Footnote 54 but anecdotal remarks suggest that children willingly engaged with the subjects and that their experiences were educational and meaningful. They were also memorable: a visitor to Mrs. Salmon's waxwork in 1793 remarked later in life that seeing the “Cherokee Chiefs . . . rivetted the scene so firmly on my memory, that I have it now fresh in my mind's eye as when I first beheld it, forty-four years since.”Footnote 55

While parents encouraged children to keep diaries as a means of self-improvement, surviving examples generally do not discuss their reading or museum visits beyond listing the activity.Footnote 56 From the rare exceptions, M. O. Grenby's study concludes that from the second half of the eighteenth century, children valued books, increasingly owning their own, received as prized gifts. Rare marginalia in children's books suggest they read carefully, repetitively, and thoughtfully.Footnote 57 However, Anna Larpent, whose later journals offer one of the best reader's records from the time, admitted that her early entries offered little reflection. Commenting upon her teen years in the 1770s, she wrote, “My methods from fifteen years of age was, to write down every Evening what persons I had seen, books read, sentiments heard and I observed much, talked little. At first these journalic notes were extremely concise—by degrees fuller, but always roughly taken . . . As I grew older I wrote better, judged better.” Indeed, what survives is a simple list of places she visited as a girl, which in 1776 included the Leverian, Royal Academy, Kew Gardens, and various waxworks, as well as the books she read, which included a host of travel accounts and histories, such as William Robertson's History of America. Unlike in later years when she exposed her own children to similar experiences, Larpent's youthful responses go unrecorded.Footnote 58 Yet evident everywhere throughout the material examined here is a concerted effort on the part of adults to engage children at their own level so as to make the important subjects of the empire and the world beyond Britain accessible and interesting as well as convey that the world beyond Britain's shores was relevant and transpiring in real time.

Creating Imagined Realities for Children

Authors and exhibition proprietors used interactive methods that sought to create immersive experiences that tapped into the imagination—a widely recognized, powerful force. Reflecting both the general medical and philosophical currents of the day, the Scottish Enlightenment figure James Beattie asserted in his essay “On Memory and Imagination” that the latter was as powerful and formative as the former: “The suggestions of Imagination are often so lively, in dreaming and in some intellectual disorders, as to be mistaken for real things; and therefore cannot be said to be essentially fainter than the informations of memory.”Footnote 59

In consequence, many histories, geographies, and travel accounts aimed at children read like virtual tours. Isaac Taylor's “little tarry-at-home travellers” series, for example, by using the first-person plural throughout the text, strives to send juvenile audiences on journeys across the globe. As Taylor reflected in a poem that concludes his volume on the Americas,

Illustrations in such volumes abound, featuring the landscapes, major products, and inhabitants of places readers visited. The Traveller: Or, an Entertaining Journey Round the Habitable Globe, pocket-sized and written as a virtual journey, boasted forty-two engravings. In it, the author sought to create “an Easy Methods of Studying Geography . . . by the combination of amusement with instruction; and to engage the attention of Youth, as well by the familiarity of the language employed, as by the fiction of a rapid Journey over the surface of the Earth.” The opening lines set the scene as an imagined parental reader gathers the children together: “Come, Felix, and you also, my dear Felicia, come and sit down by me. Now that you are growing so very tall, it is proper that you should know something about the world. I wish to take you on a journey with me, a very long journey: what think you of travelling round the World?” If the little armchair travelers were wary, the narrator reassured them “to not be frightened, I will not tire you; for we shall sit all the time as this table.”Footnote 61 This journey was travel without the expense or hassle but with all of the useful learning.

Authors and publishers represented the style as a selling point. Sarah Atkins Wilson explained in the preface to her African travel account, in which a fictitious mother and her children make a tour, that this fictional veneer would appeal to “young persons . . . [who] delight with every new accession of knowledge . . . As truth is no longer deemed incompatible with amusement, the most pleasing mode of conveying the former appears to be to blend it with the latter.”Footnote 62 While the precise impact on children is unrecorded, the reflections of adults such as William Carey, missionary to India and founding member of the Baptist Missionary Society, who claimed that “Reading Cook's voyages was the first thing that engaged my mind to think of missions” as a young man in the 1780s, highlight how profound the experiences could be.Footnote 63

Few authors matched Priscilla Wakefield's efforts to contrive fictional veneers to aid young audiences in the study of history and geography. Born into a middling Quaker family in Middlesex, Wakefield was a prolific writer on subjects ranging from botany to art. For her series of juvenile books on British and world history and geography, she invented Mrs. Middleton, a widow lady, who resided in the village of Richmond near London with her four children.Footnote 64 A Mr. Franklin, a gentleman who sometimes serves as a guide and tutor, added a male presence. Introducing the family in A Family Tour through the British Empire, Wakefield explained her goal was to “convey a general idea, to the minds of children, of the variety of surface, produce, manufacturers, and principal places of the British Empire.” To engage children, “a sketch, having the air of a real tour, and containing the prominent features of the subject, was thought likely to prove a valuable addition to the juvenile library.”Footnote 65 Sometimes the whole family traveled, sometimes one or two. In cases of the latter, Wakefield employed an epistolary style, framing the book as a collection of letters home and recipients’ responses. Often the readings took place over the intimacy of breakfast, the style positioning audiences as members of the Middleton family.

Museums that opened their doors to children operated with similar intentions. These were truly hands-on, interactive experiences—much more so than today, as many museums, including the British and Leverian museums, allowed visitors to handle objects. Such experiences left powerful impressions. As the young German visitor Sophie de la Roche reflected following her 1786 visit to the British Museum, “Nor could I restrain my desire to touch the ashes of an urn on which a female figure being mourned. I felt it gently, with great feeling . . . I pressed the grain of dust between my fingers tenderly, just as her best friend might once have grasped her hand.”Footnote 66 Wakefield, like many other writers and public commentators on education, endorsed visits to museums. In a tale titled “The Museum Ticket, or Good Action Never Loses Its Reward” in her Juvenile Anecdotes, three sisters compete for the prize of two museum tickets, given to their mother by a gentleman acquaintance.Footnote 67 In Perambulations in London, the fictitious Middleton family embrace visiting the museums as highlights of their trip, and the British Museum receives a lengthy description. In particular, Wakefield connects what the children could see and touch with what they had read. “Having often read Captain Cook's voyages with delight,” she informs readers taking a virtual tour with the Middletons, “the next apartment, being filled with specimens of the dresses, tools, musical and warlike instruments, with domestic utensils, brought from the islands of the South Pacific Ocean, afforded me peculiar pleasure.” With regard to the religious idols, which she described as hideous, she remarks, “Can rational beings reverence such objects? Nothing but fact could make it be believed.”Footnote 68 As for other visitors and commentators, for the Middletons, seeing the objects was an aid to believing.

The greatest creators of imagined realities were the painted panoramas that first appeared in London in the 1780s and immediately opened their doors to paying families. Employing perspective painting on a grand scale, the massive, encircling canvases provided an immersive experience. Although registered by Robert Barker as his invention in 1787, the panoramas at his dedicated building in Leicester Square drew imitators and calls for national tours.Footnote 69 Among the most popular attractions were imperial scenes ranging from Gibraltar to Jamaica. Robert Kerr Porter displayed his impressive works of up to three thousand square feet at London's Lyceum Theatre before sending them on national tours. His first, “The Grand Historical Picture of the Storming of Seringapatam by the British Troops and Their Allies,” painted in a mere eight weeks in the wake of intense coverage of India in the press, drew enormous crowds who paid one shilling each to witness the defeat of Tipu Sultan in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War. Such panoramas were often intended as visual recreations of timely events and opportunities for virtual travel to places in the news.Footnote 70 Proprietors of these installations routinely hired witnesses as consultants, secured endorsements from reputable participants, and emphasized their exhibitions’ authenticity at every opportunity. Costumed guides and printed guidebooks narrated events. Advertisements consistently underlined the exhibitions’ useful, educational quality, with one London newspaper recommending in 1789 that the royal family should attend to gain knowledge of the foreign lands they ruled.Footnote 71

As Wakefield remarked in her juvenile tour of London, the panorama's effect was “so astonishing as to carry the spectator to the spot. In this manner we have visited several celebrated cities.”Footnote 72 The Battle of the Nile, a night scene in which the viewing platform was reconceived as a ship's deck, was supposedly so realistic that when the royal family visited, Queen Charlotte became seasick—a story the exhibition's proprietors used to advantage in advertisements.Footnote 73 Young visitors embraced the virtual experience: memoirist Harriet Preble offers a rare record spanning several pages of her visit to the panorama of Jerusalem. She uses the first-person language of popular travel accounts, describing the exhibit as allowing the visitor “to travel, as it were, without moving!” She continued, “I should write forever if I attempted to tell you all I experienced during my imaginary pilgrimage. But surely never did two hours’ travel awaken so many new ideas and feelings. In spite of myself, my thoughts still hover around that extraordinary assemblage.” Such experiences, like the trips to museums and reading geographies and travel accounts, were intended to provoke responses beyond that of amazement at the technical spectacle. Because almost none of the hundreds of thousands of visitors’ responses have survived, Prebles's remarks offer a rare glimpse: “I looked on those minarets close to the tomb of Jesus Christ. I seemed to hear the voice of the Imaum calling ‘the faithful’ to evening prayer; and this combat between two powerful religions made me sigh over the weakness and intolerance of our enlightened age, and the uncertainty of our possessions.”Footnote 74 Her experience brought to the forefront her anxieties about the cultural tensions the expanding British Empire faced abroad.

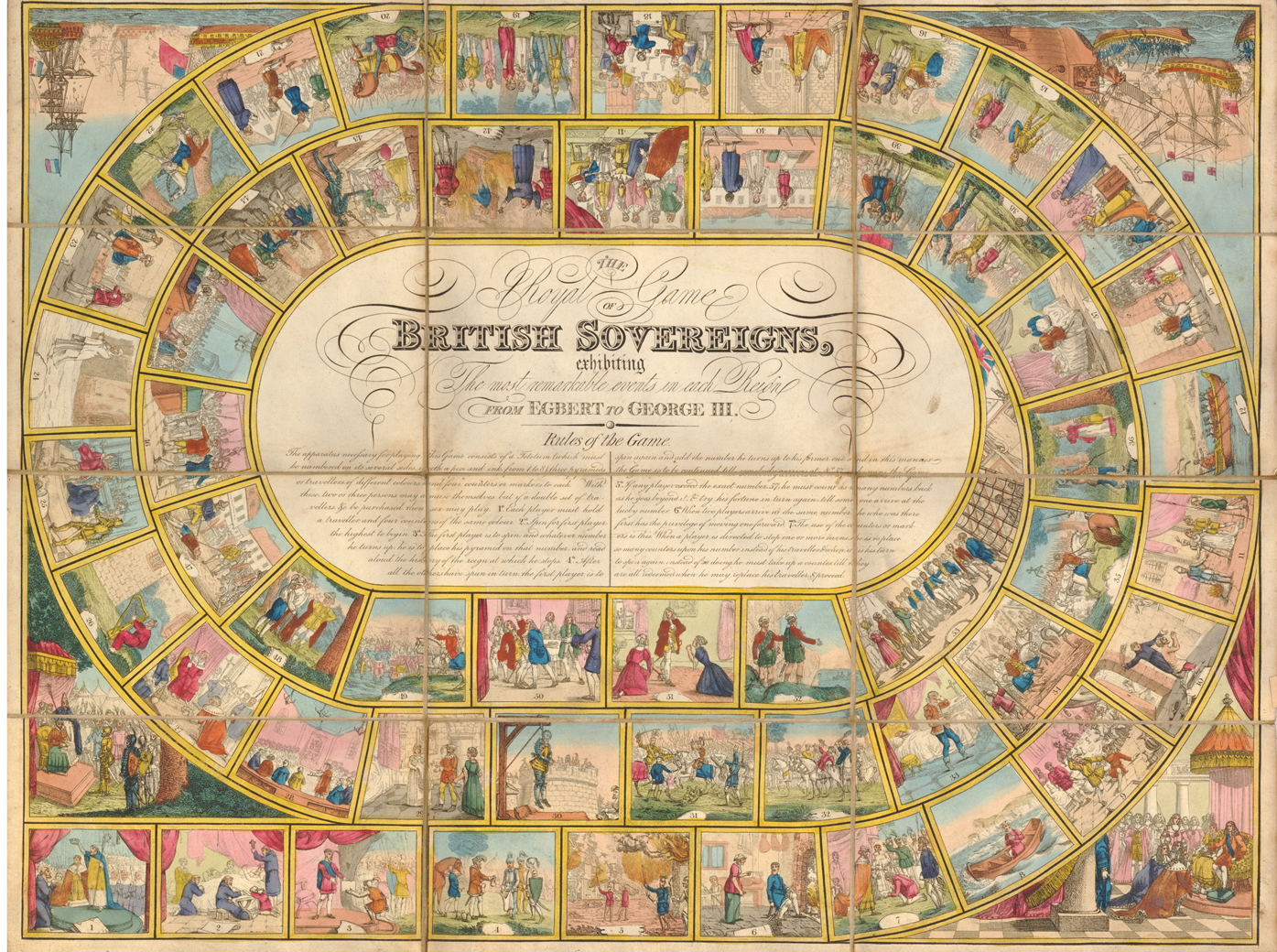

Although toys manufactured specifically for children did not become common until after the period considered here, board games emerged at the turn of the century as another popular method for exposing children to the geographies and histories of Britain, its empire, and the world.Footnote 75 Most of these games were variants of the classic race games in which each player moves a representative piece around a predetermined path of defined spaces (snakes and ladders and The Game of Life are modern examples). Spinners (“teetotums”) randomly determined how many spaces a player would move in each turn. Large, colorful boards took players on an imaginary journey through time or space, traversing roughly one hundred spaces from start to finish. Further instructions on a given place, such as “lose a turn” or “move an extra three spaces,” provided opportunities for additional excitement and a story narrative. Similar games had existed in England since the late sixteenth century; however, those games had targeted adults as much as children, and, if they had a theme, the premise was moral instruction.Footnote 76 This changed in the late eighteenth century, when cartographers and printers replaced the boards with maps, typically fifty by sixty centimeters in size, marketing them as opportunities for parents to instruct children in history and geography. The games’ producers include Elizabeth Newbery, member of the prominent publishing family. As with most printed ephemera of the period, very few of the games survive complete (see figure 2 for an example); however, based on the substantial number of advertisements throughout Britain, the survivors are a modest sample of what circulated.

Figure 2 An example of one of the few playing boards that survive. John Wallis, The Royal Game of British Sovereigns Exhibiting the Most Memorable Events in Each Reign from Egbert to George III (London, ca. 1811). ©Copyright the Trustees of the British Museum.

Like the juvenile geographies, advertisements and the prefacing instructions for the games addressed parents and promoted the education benefits. The instructions with the game Geographical Recreations or a Voyage around the Habitable Globe explained that it was intended “to familiarize youth with the names and relative situations of places, together with the manners, customs and dresses of the different nations of the habitable globe; and . . . will prove a continual source of amusement to young people of both sexes, and will furnish such a fund of geographical knowledge, as may prove equally beneficial in reading and conversation.”Footnote 77

The boards and accompanying booklets offered a wealth of information about the physical geography, economies, and peoples of various areas, with heavy emphasis on how they related to Britain and its empire. For instance, on space 25 of a Tour through Asia, players encounter “HUDRABAD [Hyderabad]. Near the Diamond Mines of GOLCONDA. Adventurers purchase here a portion of land and dig at hazard for Diamonds, by which they sometimes make immense gain.”Footnote 78 Another game, Geographical Recreations or a Voyage around the Habitable Globe, took players to “the wonders of the nature in each quarter of the world.” Using the map and accompanying booklet, which was packed with detailed information, players could “Cascade on the White River” in Jamaica and admire the “Natural Rock Bridge” in Virginia. Unlucky players, however, might find themselves landing on the “Pillars of Burning Sand, in the Deserts of Arabia” (essentially a sandstorm), resulting in removal from the game.Footnote 79

Landing on a space for “the Falls of Niagara” in a game did not, of course, alone constitute a meaningful engagement with empire. Adult involvement was expected to ensure the connection. Accompanying parents, too, toured the exhibitions and read out both the travel accounts and the educational passages for each space on which a child landed in the history and geography games. For instance, the 1795 A Complete Course of Geography had 389 spaces, each with a corresponding card carrying a geographic question about places or inhabitants. The spaces, in turn, were grouped into geographic regions with corresponding “lessons” to be given by the adult.Footnote 80 Thus, while the child led the discovery by moving about the boards, the games’ designers expected parents to offer continual contextual instruction. This was directed learning, and children were directed to consider the empire and world in which it operated in terms of evidence of British superiority, opportunity, and responsibility.

Projecting British Superiority in a World of Opportunities

The literature, exhibitions, and games that connected children in Britain to the world beyond its shores shared a remarkable consensus in the messages they conveyed. Chief among these was the presumption of British superiority, the opportunities that Britain's interaction with the world offered, and the importance of the empire to the national interest. Neither religious denomination nor gender created dividing lines, as content creators sought the broadest audiences possible. In short, children in Britain were taught to view the world with wonder but also with confidence that their nation, above all others, would direct the future.

A consistent theme was European and especially British superiority. Geography has long been a tool of imperialism and conquest. Britain during the long eighteenth century made unprecedented use of it by subjectively creating borders, constructing categories of difference, and then presenting them as objective facts. Experiences that targeted children were no exception.Footnote 81 Reflecting what Edmund Burke dubbed the Scottish Enlightenment's “great map of mankind,” in which civilizations were evaluated and categorized according to their supposed socioeconomic development, these mediums worked to make sense of the flood of information as well as to reaffirm Britain's place atop the hierarchy of civilizations.Footnote 82 Museums, for instance, often grouped contemporary weapons or clothes of so-called primitive societies, such as American Indigenous peoples, with ancient European weapons, highlighting the superior advancement of contemporary British society. Similarly, a display cabinet might show the evolution of weaponry by presenting a club from the South Pacific Islands as the basest example and a British rifle the most advanced.Footnote 83 Publications aimed at children employed similar methods to assert messages of superiority. In Geography and History, for example, the text is divided by regions, with a disproportionate amount of space devoted to the places and peoples that Britain engaged via imperial rule or trade. Within those overseas regions, the British presence is emphasized over Indigenous peoples, and considerable attention is devoted to describing the territorial claims of various European empires—such as a two-page table is supplied for the Caribbean.Footnote 84

Board games made similar assertions of Britain's preeminence in world affairs via their format and contents. The popular Complete Voyage Round the World, which first appeared in 1796, is a typical case. Using a hand-colored world map of roughly fifty by sixty-four centimeters marked with one hundred numbered spaces, up to six players embark on an imaginary global journey, setting off from Portsmouth and concluding in London. In India, players landing on “Calcutta” are informed of its importance to the East India Company. The space also serves as a memorial to the Britons who died in service of the empire, with players being instructed, “Stay here one turn to see the black hole, where 123 persons were suffocated in 1757.” Madras, Java, Botany Bay, and New Zealand all are given spaces, along with a host of places associated with James Cook's voyages, including Tahiti and Nootka Sound. At the space “Owhyee” [Hawaii], players are again reminded of sacrifice in imperial service by forfeiting a turn while they view the bay where the natives killed Cook and mourn his loss. Players landing in Jamaica receive a brief lesson on its capture from the Spanish in 1655. Space 67 is “Quebec—the capital of Canada, in North America, famous for the death of General Wolfe, in 1759.”Footnote 85 Some games were subtler. In the South American chase board game Wallis's New Game of Wanderers in the Wilderness, players start in Belize, its inhabitants depicted as white colonists and dressed like Europeans, and proceed to explore a visually more Indigenous and less cultivated South America.Footnote 86

History games, in which players move chronologically, heavily emphasized British imperial events. Historical Pastime, for example, covered the “the history of England from the conquest to the accession of George the Third.” Starting at the Battle of Hastings, players moved through 158 spaces on a heavily illustrated map featuring such events as “East-India Company Established,” “Tobacco Introduced,” and the final space, “War with America.” For each space, the accompanying booklet includes a synopsis of the event to be read aloud.Footnote 87 Wallis's New Game of University History and Chronology, although claiming to be a world history game starting with “The creation of the World,” followed shortly thereafter by “Abel slain by his brother Cain,” predominantly featured recent British events. The 1814 edition included spaces highlighting such events as the accession of George III (for which the lucky player earned an extra turn), the Cook voyages, “Botany Bay colonized,” and “Seringapatam taken.” Players unlucky enough to land on “War between Great Britain and America” suffered the hefty penalty of three points. At the end of the game, the prize for the winner of the global game was entirely British: being “appointed First Lord of the Treasury [prime minister]” of Britain.Footnote 88

Other contexts were even more overt. Performances attended by children tended to be especially nationalistic and celebratory of all things martial. For instance, the guidebook to Robert Kerr Porter's panorama of the 1799 Siege of Acre plainly explained that its object was “to collect a few of the most interesting Particulars relative to the SIEGE OF ACE, and to that FIELD OF ACTION where the gallantry of the BRITISH characters was so eminently displayed before and Army of Republican Frenchman led by the redoubtable Buonaparte [sic].”Footnote 89 An estimated 30 percent of all panoramas during this period were of battles.Footnote 90 And Britain won virtually all of them. As the printed guide to the panorama “An Historical Sketch of the Battle of Alexandria, And of the Campaign in Egypt” (which depicted the campaign as a defense of Britain's Asiatic empire) remarked in typical language celebrating Britons’ martial qualities: “This bravery, so inherent in the British, is not, however, surprising, when we recollect that our hardy forefathers repelled the well-disciplined and well-armed legions of Julius Caesar from their shores.”Footnote 91 Britons were heralded as natural warriors; the eighteenth-century empire that Britain sought to expand and rule was merely the current arena.

Few exhibitions outshone those of the celebrated Philip Astley, whose live reenactments became a mainstay of “respectable” family entertainment in London, and, when his troupe began touring in the early nineteenth century, beyond.Footnote 92 Although any credible estimate of the size of juvenile audiences is impossible, the widely printed advertisements and London guidebooks made it clear that families with children were welcome. Contemporary diaries also record visits to Astley's theaters and those of his imitating competitors. Elizabeth Harris, for example, went to Astley's in 1780 with her young daughter. Louis Simond, an American tourist, remarked in 1810 that, “Looking around the room . . . I saw the boxes filled with decent people—grave and demure citizens, with their wives and children, who seemed to take pleasure in all this.”Footnote 93

Astley and his son produced a wealth of imperial scenes that included fabulously costumed actors, elaborate sets, and live animals. Early titles included English Bravery; Or, British Sailors landing on a Savage Island (1787) and A New Comic Dance, called The Ethiopian Festival, Representing the whimsical Actions, and Attitudes, made use of by the Negroes (1788). Tippoo Saib's Two Sons (1791 feted “the late satisfactory and glorious Treaty of Peace, obtained by the brilliant and successful War Operations under the Command of Lord Cornwallis”; its third act, “An Oriental Military Festival,” included supposedly authentic Indian music. Designed primarily to engage audiences by reenacting the latest military events reported in the press, Astley's performances also turned to celebrated historical events. In November 1789, at his metropolitan theaters at Westminster Bridge and Bermondsey Spa Gardens, he launched “The Siege of Quebec,” reliving the 1759 British capture of the city and the death of General Wolfe, and the “Siege of Gibraltar—By Royal Authority,” lauding the British repulse of the Franco-Spanish assault in 1782. According to newspaper reports, the former drew nightly audiences of over four thousand.Footnote 94

As with museums and panoramas, purported accuracy was central to Astley's sales pitch. Advertisements, programs, and guides relentlessly hammered the message that the performances, while entertaining, were as real as any written account. A seven-scene reenactment of Britain's capture of Martinique in 1794, opening less than two months after the actual events, drew enormous praise for both its accuracy and timeliness. One advertisement representatively declared that Astley was “Displaying one of the grandest and most Extraordinary Entertainments that ever appeared, GROUNDED on AUTHENTIC FACTS.” Uniforms, music, dances, dialogue, and weaponry were highlighted as factual elements of the performances, along with public endorsements from participants. When explaining the continuation of his “Grand Historical Spectacles of Action, founded on the recent Occurrences in India, called THE STORMING OF SERINGAPATAM; or, THE DEATH OF TIPPOO SAIB,” which included “Elephants, Camels, &c. in motion,” Astley declared the added performances were “by the desire of several Officers of the Army.” He went to great pains to highlight his association with the military, emphasizing his own cavalry service by visiting his old regiment and even sending horses to British forces fighting in Europe.Footnote 95 Such seemingly objective accuracies lent critical credibility to his highly subjective interpretations: imperial conquest was violent, British participation was valorous service to the nation, and the British were superior to their opponents–whether European or Indigenous.

Although less dramatically nationalistic than Astley, plenty of children's writers were equally overt in their assumptions of British and broadly European superiority. As Sarah Trimmer's Family Magazine bluntly but representatively remarked in its inaugural issue when introducing its series on places around the world, “Make no doubt but that the comparison will convince Englishmen, even of the lowest ranks, that they have reason to value their native land, and to be thankful to Providence that they were born on BRITISH GROUND.”Footnote 96 The female author of Geography and History similarly states, “A well-educated Englishman, is the most accomplished gentleman in the world and understands arts and sciences best.” As for the British system of government, she boasts, “These three different powers, the King, Lords, and Commons, being a check upon each other, the government of Great Britain is reckoned the most perfect of any in the world.”Footnote 97

The world outside of Europe is largely treated as ripe for British imperialism, by colonization or trade. Geography Made Easy for Children is typical in its sweeping dismissal of sub-Saharan African civilizations with its claim that “Negroland, or the Country of the Blacks,” is “mostly uncivilized and ignorant people,” their governments either despotic or nonexistent.Footnote 98 Even peoples widely accepted as being civilized and technologically developed are described in terms of opportunities for European rule. Accounts almost universally agreed on India's wealth while dismissing the capabilities of its inhabitants. “This Country is so exceeding rich,” declared the anonymous author of A Museum for Young Gentleman and Ladies, “that it is thought by many to be the Land of Ophir, where Solomon sent for Gold.” Family Magazine noted the people's docility, describing them as a “feeble,” “indolent,” and generally lazy, their virility declining by the age of thirty. Meanwhile, the magazine described Indian society as in a state of collapse—“once a regulated government, but now a scene of frequent bloodshed and confusion.”Footnote 99 China avoided British colonization until the Victorian era, but its potential for “improvement” drew increasing attention by the turn of the century. While earlier geographies for children were often in awe of Chinese infrastructure and dutifully describe the cultivation of tea, later texts are more critical. The Family Magazine, for example, in 1788 describes China as a wealthy but technologically stagnant society whose people “are so wedded to their ancient customs” that their agricultural and manufacturing practices have fallen behind “those of Europe, or indeed America.” Thus, the magazine concludes after detailing a series of Chinese deficiencies, that although “the Chinese pretend to be a nation of such antiquity as exceeds belief . . . no Englishman would change for the better by becoming an inhabitant of China.”Footnote 100

The authors went to great lengths to describe the wealth, actual or potential, of such places, further highlighting empire as opportunity. Sub-Saharan Africa is universally depicted as a fertile land full of colonizing and trading opportunities. “There is scarcely a country in the world, that is better calculated for affording the necessaries of life to its inhabitants,” the Family Magazine proclaimed; Geography Made Easy for Children representatively described Africans as having “good stature and robust constitutions.”Footnote 101 Earlier Chinese infrastructural improvements, the Family Magazine explained, “render China very delightful to the eye, as well as fertile, in places that are not so by nature.” Although Chinese manufacturing lags behind Britain's, the magazine notes that while “it is an industry without taste or elegance, [it is] carried on with vast art and neatness.” The magazine made similar remarks about India, describing the soil of British-ruled Bengal as “uncommonly fruitful” and praising the inhabitants as a whole as being “more industrious than the Europeans in weaving, sewing, embroidering, and other manufactures” as well as other handicrafts.Footnote 102

The messages of Britain's national greatness and boundless opportunities were not without caveats. The most prominent by the 1780s was that of responsibility to overseas peoples with whom the British sought to trade and rule. In this context, imperialism was cast as a tool whose palatability, if not desirability, hinged on whether or not it was used as a force to benefit the ruled as well as the rulers. Such concerns are nowhere more evident than with the treatment of African slavery and the slave trade.

Projecting Responsibility: The Case of the African Slave Trade

The preponderance of material and experiences discussed here cast the British and their endeavors favorably; however, this prejudice had limits. As British society as a whole increasingly reflected on the more malignant aspects of imperialism during the later decades of the eighteenth century, children were not shielded. In fact, they were actively targeted. African slavery and the slave trade serve as the most poignant example of how British children were engaged and called upon to consider imperialism as having a moral component. Yet, far from fostering anti-imperialism, such an approach invigorated the case for empire.

Britain's trials and tribulations in the course of the American Revolution were a check to the national optimism toward the empire that followed the Seven Years’ War. Closely watched by the wider British public via the press, the protracted and deeply frustrating affair opened the empire to a torrent of criticism that had been held back by the now-broken dam of previous success.Footnote 103 Opponents of slavery and the slave trade were among the first to take advantage of the new scene. Preaching in Richmond in 1784 on the national day “appointed for a General Thanksgiving” to mark the end of the war, Gilbert Wakefield's widely reprinted sermon struck a chord with many Britons that would sound across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: “Our Proficiency in Arts and Sciences had been commensurate to our military Reputation. But have we been as renowned for our liberal Communication of our Religion and our Laws, as for the Possession of them?” The answer he offered was an unsettling challenge not only because of what he accused but also in that he faulted his countrymen as a whole, repeatedly employing the word “we”: “Let India and Africa give the Answer to these Questions. The one we have exhausted of her Wealth and her Inhabitants, by Violence, by Famine and every Species of Tyranny and Murder. The children of the other we daily carry off from the Land of their Nativity, like Sheep for the Slaughter, to return no more: we tear them from every Object of their Affection; or, sad Alternative! Drag them together to the Horrours of a mutual Servitude.”Footnote 104 National guilt required communal recompense.

The response was extraordinary popular action that took such forms as petitions, boycotts of slave-produced sugar, and public media campaigns. Notably, the rank and file of such crusades were women.Footnote 105 As discussed in detail above, women were primarily responsible for educating children about the empire and the wider world. Women, especially mothers, were expected to serve as the moral guardians of the home and, by extension, the nation. The education of children, particularly the informal sort provided in the context of a family, fell comfortably within the realm of acceptable female public participation, if not leadership.Footnote 106 The empowerment of women through collective public action set the important precedent that one did not need to be an enfranchised man to take responsibility for Britain's national behavior or to affect change.

Middling and elite British children were not entirely unfamiliar with discussions of slavery. John Newbery's 1761 Tom Telescope, which noted the hypocrisy of a man who was kind to his pet animals but cruel to his slaves, was among the handful of children's books that raised the issue of slavery before the 1780s. Many books on geography had tended to be less sympathetic to slavery's victims.Footnote 107 The 1760 edition of A Museum for Young Gentlemen and Ladies briefly describes the inhabitants of Africa's interior as devil-worshipping brutes “who will sell their Children and nearest Relations, if they have an Opportunity,” typically laying the responsibility for slavery squarely on Africans.Footnote 108 By the late 1780s, reflecting the national shift toward outspoken condemnation of the slave trade, printed materials for children that engaged with subjects related to the empire almost universally condemned the practice. Geography and History called the slave trade “a barbarous traffic between man and man!”Footnote 109 When a player landed on Senegal in Wallis's Complete Voyage Round the World, the following was to be read aloud: “Senegal—a river which runs through a kingdom of the same name in Africa. The traveller must stay one turn here, to lament the great traffic which is carried on by European vessels in the Negro trade.”Footnote 110 The African edition of Taylor's Little Tarry-at-Home Travellers made slavery a central issue, its cover featuring an African in chains.Footnote 111 Following a reprint of “A Negro Song” in a 1799 issue of the Young Gentleman's and Lady's Magazine, the editor Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, bluntly remarked to readers. “[The verses] are so pathetic, that they melted us to tears; and if our young readers feel no emotion of sympathy, we sincerely pity them.”Footnote 112 In the games and books aimed at children during this period, justifications of slavery are wholly absent.

Critically, the message was not simply one of exposure and condemnation. Abolitionist William Fox proclaimed in his seminal Address to the People of Great Britain, which went through at least twenty-six editions within a year of being published in 1791, “For let us not think, that the crime rests alone with those who conduct the traffic, or the legislature by which it is protected. If we purchase the commodity we participate in the crime.” After all, he stressed, “The slave-dealer, the slave-holder, and the slave-driver, are virtually the agents of the consumer, and may be considered as employed and hired by him to procure the commodity.” While the slave owner was guilty, “we, who have knowingly done any act which might occasion his being in that situation, are accessories after the fact.”Footnote 113 For children as well as adults, a direct consequence of such charges was the sugar boycotts in which hundreds of thousands of families distanced themselves from the crime of slavery by refusing to consume its primary product.Footnote 114 This was no small sacrifice. Sugar was the most accessible commodity of imperial trade, reaching even the poorest and most remote households in vast quantities. By 1800, per-capita consumption had reached twenty pounds weight—a 2,500 percent increase from a century earlier.Footnote 115

No doubt plenty of children grumbled at abstaining from sugar, as in the scene of Isaac Cruikshank's 1792 satirical print, “The Graduate Abolition off the Slave Trade, or leaving of Sugar by Degrees,” in which parents argue with their offspring over whether complete abstinence or reduction is best (see figure 3). Priscilla Wakefield, among others, offered instructions on how parents could tackle the subject of slavery and its connection to British children. In a chapter in her Mental Improvements, a family scene opens with Mr. Harcourt describing the botanical origins of sugar to his children and their friend. What starts as a lesson in horticulture quickly turns to a discussion of slavery. Mrs. Harcourt then details slavery's horrors, focusing first on “corrupt,” warlike, and “ignorant” African rulers who, “instead of being the defenders of their harmless people . . . have frequently betrayed them to their cruelest enemies.” She graphically details the miseries aboard a slave ship before explaining how life in the Caribbean depends on the master, noting that “among the overseers of sugar-plantations, there are some men of feeling and humanity; but too generally their treatment is very severe.” Slaves’ lives are hard, according to Mrs. Harcourt, because they are “accustomed to an inactive indolent life, in the luxurious and plentiful country of Africa.” Aghast at the dark origins of sugar and ashamed at Britain's participation, one child exclaims, “How much my heart feels for them!” Longing to take responsibility for their country's role and pursue action that will contribute to slavery's demise, the children quickly agree to give up sugar.Footnote 116

Figure 3 Isaac Cruikshank, “The Graduate Abolition off the Slave Trade, or leaving of Sugar by Degrees” (London, 1792). Library of Congress, PC1–8081. A family, possibly the royal family, have tea together and discuss abstaining from sugar in their tea. While the central male figure advocates total abstinence, the rest want a reduction only. The figure to the man's right, possibly Queen Charlotte, declares, “Now my Dear's only an ickle Bit, do but tink on de Negro girl dat Captain Kimber treated so cruelly.”

Wakefield encapsulates many of the arguments presented in this article. The Harcourts’ conversation is part of a book of collected essays whose topics range from salmon fisheries to making glass, further highlighting that lessons related to the empire were part of a larger curated corpus of useful knowledge. Moreover, the discussion between adults and children is depicted as taking place in an informal setting. Even the rise of the subject is impromptu, as it rose out of a lesson on the botanical origins of sugars. Although Mr. Harcourt participates in explaining the science of that subject, Mrs. Harcourt handles the moral concerns regarding slavery, thus reflecting the expectation that women play a central role in issues of moral instruction. Critically, the children are not passive. Through a Socratic-style method, they are encouraged to inquire, reflect, and consider courses of action—for the state and themselves.

Works aimed at children and their parents also carefully laid out how to handle dissenting views on slavery. Children's instruction as whole heavily emphasized politeness and the benefits of rational argument, and, as Barbara Hofland's The Barbadoes Girl: A Tale for Young People demonstrates, the topic of slavery was to be approached in the same way. Hofland, a prolific writer of more than a hundred books including fiction along with geography and history, recounted the story of Matilda Sophia Hanson, the only child of a West Indian planter.Footnote 117 Following the death of her father, Matilda goes to stay with longtime family friends, the Harewoods, in England, while her mother settles the family affairs in the West Indies. The tale is not only about Matilda's redemption but also about the Harewood children's engagement with difference, and their patient perseverance. Before Matilda's arrival, Mr. Harewood gathers the children to inform them of the impending guest, cautioning them that her perspectives will be different from theirs but that difference is a learning opportunity: “It must, however, strike you, that in coming from a distant country . . . she cannot fail to possess many ideas and much knowledge which are unknown to you.” Moreover, he warns, the children, being in a family of abolitionists, should not use the opportunity to demean their guest, because “such conduct would ensure most serious displeasure.” Mrs. Harewood underlines the sentiment, noting that laughing at difference is barbarous and would show the children to be “deficient in that education which even the savage tribes of America give their children.” Unsurprisingly, Matilda is an overindulged child, accustomed to “the numerous negro dependents that swarmed in her father's mansion, over whom she had exercised all the sovereignty of a queen.” The story is far less about the Harewoods gaining a new perspective as a result of an equal airing of the arguments in favor of slavery than it is about Matilda's recognition of its inhumanity. Hofland's tale, and others like it, were constructed in the familiar established style of the moral tale. Through persistence and modeling of good behavior, the Harewoods bring Matilda to their way of thinking—much like the hundreds of printed moral tales of well-behaved children earnestly redeeming their poorly behaved peers.Footnote 118

It would be a mistake to label such writers as opponents of imperialism. Rather, they were vociferous critics of some imperial practices, desiring an empire that bettered not just the colonizer but also the colonized. In short, they emphasized to children that imperial rule and trade were indifferent tools, made good or evil depending on who wielded them. Even Anna Barbauld and John Aikin, whose popular 1792 Evenings at Home featured pacifist warnings against impending war with France, included the pro-imperialism game “The Colony” described at the beginning of this essay. As to the future of Indigenous peoples, the game strikes an optimistic tone. Citing William Penn as a positive example, the father of the Barlow family explains, “We are a peaceable people, and I hope shall have no occasion to fight. We mean honestly to purchase our land from the natives, and to be just and fair in all our dealings with them.”Footnote 119 Nor was the central message simply one of Christian evangelism. While Protestantism received broad nondenominational support in all of these genres and venues, it was but one component to the overall civilizing benefits of British society. In fact, Wakefield's imperial hero was the British merchant: That “[commerce] has already tended to civilize the ferocious tribes, to enlighten the ignorant, and to improve the condition of all, by interchanging the industry and produce of distant climates,” she asserted, “is clearly shown in the pages of history.”Footnote 120

Accounts for children from the late 1780s onward consistently attempted to humanize Africans in the same manner as Josiah Wedgwood's famous slogan on his anti-slavery medallion in 1787, “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” African characters, usually current or former slaves, appear frequently in stories for children, and they invariably demonstrate their humanity and intelligence and, thereby, the inhumanity of slavery. In typical fashion, Babay, an African servant who works in a family fishing business in Darton's Little Truths, is praised for his business acumen, earning the “high opinion of his honesty and skill” from people in the local market. At one point, he rescues a white boy.Footnote 121 In her popular Sketches in Human Manners, Wakefield dedicates a chapter to the story of Abba, a West African villager. “Neither the sooty colour of his complexion, (for he was of a jet black) nor the short, curly wool of his hair, which surrounded his face,” she wrote, “could disguise a countenance expressive of generosity and courage.”Footnote 122

In this more empathetic outlook, responsibility for good relations shifted increasingly from the late 1780s to the colonizers. As the Family Magazine observed, “It has long been a prevailing opinion, that the inhabitants of Guinea, are a set of savages not worthy to be ranked among the human species, incapable of improvement, miserable, and insensible of the benefits of life.” Such perspectives, it continued, enabled proponents of slavery to assert wrongly that “letting them live . . . in a state of the most abject slavery, is doing them a favour.” Calling slavery “a disgrace to a Christian nation” and urging Britons “to restore to the poor Africans the common rights of humanity,” the magazine, like others at the time, portrayed Africa as a once-happy continent ruined by Europeans’ demand for slaves. “There is scarcely a country in the world, that is better calculated for affording the necessaries of life . . . and, when not provoked by the inhuman treatment of the Europeans, the natives still retain a great deal of innocent simplicity, and show themselves to be a human, sociable people.” Africans, the Family Magazine and others emphasized, were “as capable of improvement as other men.”Footnote 123

In this context, children's writers widely endorsed Sierra Leone. Founded in 1787 for the resettlement of the “Black Poor of London” and black refugees of the American Revolution, the colony received major backing from British abolitionists.Footnote 124 Despite early struggles, the company colony became a crown colony in 1808 and continued to accept refugees from the recently outlawed slave trade. Geographies and histories praised it, and board games highlighted it, awarding extra turns for landing on it and singing its praises in the passages to be read aloud. In her final account of Middleton family travels, Wakefield provides a typical resounding approval of the colony. Written as letters home, the account sees Arthur and his servant, Sancho (a slave Arthur freed on an earlier trip to North America), head to Africa. Ultimately, they reach Sancho's native village only to find that it had been raided by neighboring people six years earlier and its inhabitants killed or enslaved. The answer to the “malediction” of slavery, Arthur determines, is British intervention: “There were no means more probable of gradually undermining that infernal traffic, than the prosperity of colonies founded on these [British] principals.” In exchange for its goods, he declares, “Africa was likely to derive the still more important benefits of religion, morality, and civilization.”