In January 1776, David Hume prepared his will and instructed his executor, Adam Smith, to “destroy” his “papers” post mortem, with the exception of the Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion and any other paper that did not date from the past “five years.”Footnote 1 In a codicil to the will, dated eighteen days before his death on 25 August 1776, Hume deprived Smith of this instruction and transferred it to his other executors: his brother, John Home of Ninewells and his printer, William Strahan. In this instance, Hume asked Home of Ninewells to “suppress” his “manuscripts,” with the exception of the Dialogues and My Own Life, Hume's manuscript autobiography, which were to be “printed and published” by Strahan within two years of Hume's death. Hume's essays “Of Suicide” and “Of the Immortality of the Soul,” prudentially suppressed in 1755–56, could be preserved and published optionally.Footnote 2 No recension of Hume's will mentioned his “letters” or “correspondence”; it was not clear whether these were comprehended by Hume's references to “papers” and “manuscripts,” or exempted by Hume's stipulation to conserve whatever he had written within the past “five years.” The polysemy of the word “suppress”—not strictly synonymous with “destroy”—was additionally ambiguous. Were Hume's papers to be conserved by his executors but concealed from public view? Then there was the question of why Hume himself, knowing of his impending death, did not destroy the letters by his own hand.Footnote 3

Strahan interpreted these ambiguities as a form of assent to the posthumous publication of Hume's correspondence, and he asked Smith and Home of Ninewells whether he could combine an edition of Hume's My Own Life with selections from Hume's letters.Footnote 4 Smith was indignant. Hume's executors, he responded, were instructed to destroy his letters: “I know he always disliked the thought of his letters ever being published.”Footnote 5 Home of Ninewells, however, was more congenial. He retained his brother's manuscript correspondence and bequeathed it to his second son, David Hume the Younger (1757–1838), who would oversee the publication of his uncle's Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion in 1779.Footnote 6 Hume the Younger would later lead an illustrious career as a judge and legal educator. He was appointed baron of the Exchequer in 1822, and he enjoyed the acquaintance of numerous literati in Scotland and abroad.Footnote 7 He would also serve as a dutiful custodian and collector of his uncle's manuscripts, occasionally contacting Hume's correspondents and their legatees for any autograph relics by his kinsman that they happened to possess.Footnote 8 In later life, Hume the Younger gifted a small number of these manuscripts to friends as keepsakes,Footnote 9 and he sanctioned the publication of several others in literary periodicals.Footnote 10 Upon his death in 1838, he left the remainder of his collection to the Royal Society of Edinburgh. The collection remains the richest extant source of manuscript material about Hume's life, containing practically every surviving letter that Hume received and dozens that he sent, in the form of drafts, retained copies, or returned originals.Footnote 11

At the time of their donation, Hume's papers were regarded by the Society as a burden. Questions surrounded the Society's obligation to limit access to the correspondence, given the apparent implications of Hume's will and its codicil. When the literary journalist John Hill Burton (1809–1881) asked in 1843 to consult the papers for a biography of Hume, a committee was grudgingly convened to assess his intentions.Footnote 12 Against this backdrop, a market for Hume's manuscripts was emerging among the cultists of the autograph letter.Footnote 13 By 1900, 125 of Hume's autograph letters and manuscripts had been sold by Sotheby's alone.Footnote 14 The next century witnessed a remarkable dispersion of Hume's autograph letters into the hands of dozens of collectors throughout the world; the most recent census counts at least 560 letters in at least sixty repositories, outside of the collection preserved by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, which is now on deposit in the National Library of Scotland.Footnote 15

In lockstep, the publication of Hume's correspondence burgeoned. Between 1766 and 1932, 515 of Hume's letters had appeared in print, extracted from the possession of Hume's addressees or their families and edited for public consumption.Footnote 16 Burton's Life and Correspondence of David Hume (1846) and Letters of Eminent Persons to David Hume (1847) transcribed numerous letters from the Royal Society's holdings; George Birkbeck Norman Hill's Letters of David Hume to William Strahan (1888) produced a cache of unknown letters to William Strahan, Hume's friend and executor; J. Y. T. Greig's Letters of David Hume (1932) provided scholars with a critical edition of every known letter written by Hume; and Raymond Klibansky and Ernest Campbell Mossner's New Letters of David Hume (1954) offered a significant addendum to Greig's researches, partly in the service of Mossner's Life of David Hume (1954)—the definitive biography for much of the twentieth century.Footnote 17

The discovery, sale, and publication of Hume's letters has continued without pause in the past six decades. Since 1954, 143 additional letters by Hume have appeared in dozens of publications, often singly.Footnote 18 Numerous important literary manuscripts have also materialized. Between 2015 and 2018, four previously unknown manuscript letters by Hume were offered for sale in the United Kingdom and the United States.Footnote 19 The most important of these letters, in which Hume responds to Robert Traill (1720–1775), the Aberdeen clergyman and religious controversialist, was sold for the unusually high sum of £40,000.Footnote 20 The interest that this letter commands is understandable: Hume is responding to Traill's critique of his essay “Of Miracles” (1748). Yet this interest is amplified by the letter's distinction, among Hume's extant correspondence, as an item of intellectual substance. In prefacing his Letters of David Hume, J. Y. T. Greig anticipated the disappointment of his readers in noting that he had failed to discover any new letters of importance to the interpretation of Hume's philosophy, complementing the famous correspondence between Hume and Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746) on Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature or the remarkable exchange between Hume and Gilbert Elliot (1722–1777) on the Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion.Footnote 21 Hume, it seemed, was reluctant to discuss philosophical matters in letters and diffident about the use of letters to chronicle his reading or significant ruminations.

The publication of two previously unknown but substantive letters in 1972–73 was thus a moment of tremendous importance for the scholarship of Hume's life and thought. In the Philological Quarterly and English Studies, the academic Michael Morrisroe recounted his discovery of the letters among the papers of a deceased collector and transcribed each letter with a learned introduction and apparatus.Footnote 22 The letters have since entered the standard narrative of Hume's biography and writings, as monuments of Hume's correspondence at two crucial moments in his life: visiting Reims as a young man in 1734, and residing in Paris as a diplomat in 1765. Both letters offer a considerable addition to our knowledge of Hume's intellectual development. The letter of 1734 reveals Hume's interest in the work of George Berkeley (1685–1753) and his acquaintance with Noël-Antoine Pluche (1688–1761), the author of Le spectacle de la nature (1732–1750). The letter of 1765 shows Hume's persistent interest in writing an “ecclesiastical history” and his first steps in procuring the scholarly materials necessary for its composition. The first letter, excerpted at length in the second edition of Mossner's Life of David Hume (1980), is routinely cited by scholars as evidence of Hume's familiarity with Pluche and his early awareness of Berkeley's Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge (1710).Footnote 23 The second letter, although less frequently cited, features in scholarship on Hume's historical writing and authorial self-fashioning.Footnote 24 It is the contention of what follows that both of the letters are forgeries—and that their author was not Hume at all but the perpetrator of a twentieth-century hoax. This suggestion is not new. Published doubts have surrounded the two letters since 1984, as we will see. But the doubts have been expressed too quietly or qualifiedly. The hoax is now so thoroughly embedded in the historiography of Hume's life and writings that scholars no longer realize that they are trafficking in its fabrications.

The Transmission of Hume's Manuscripts

In order to substantiate the allegation at the heart of this article, it is important to gain a clearer sense of the range and character of Hume's surviving letters and the conventions that are typically applied to the assessment of their authenticity. There are approximately between 800 and 1,000 known manuscripts in Hume's handwriting, broadly divisible into three categories: letters, non-epistolary documents (checks, receipts), and literature.Footnote 25 Letters constitute the bulk of these manuscripts (ca. 650 items), although the total number of extant letters attributable to Hume (ca. 800 items) includes letters in the hands of amanuenses or later copyists, and at least seventy-three letters that have survived on the basis of transcriptions from lost or non-locatable autographs. A recent census of Hume's known letters runs to 796 items, with the following annual distribution:

Two aspects of these statistics deserve emphasis: the exiguity of material from Hume's early life (only eighteen letters survive from the years 1711–1740) and the practice of ascribing letters to Hume, notwithstanding the absence of an extant manuscript. These issues have created significant difficulties for the scholarship of Hume's early correspondence, sparking controversies over the dating of fragmentary letters and prising open a space for the intrusion of forgeries and spuria. There are comparable problems in the bibliography of Hume's works, involving the surmised attribution of anonymous publications. In those cases, the allegation of authorship has often turned on Hume's style,Footnote 26 suggestive passages in his correspondence,Footnote 27 or the controvertible recollection of a memoirist.Footnote 28 In the most difficult instance, the attribution to Hume of a pamphlet on the Scottish militia, Sister Peg (1761), scholars have had to contend against Hume's apparent confession that he authored the work himself, in spite of the mass of evidence that has pointed, insistently, to Adam Ferguson (1723–1816).Footnote 29 In principle, the attribution of letters and manuscripts should depend on the use of similar canons of evidence—the style and provenance of the item or any corroborative reference to the item in ancillary documentation—alongside the supposedly decisive congruence of the item's handwriting with “incontestable” specimens of Hume's autograph. Yet even handwriting can prove resistant to comparison. The problem is acute in the case of a Hume manuscript sold by Sotheby's in 1988 without a verifiable provenance in its advertisement: a manuscript copy of university lectures on “fluxions” (infinitesimal calculus) given by George Campbell (d. 1766) at the University of Edinburgh in 1726, supposedly transcribed in Hume's “early” handwriting.Footnote 30 The absence of a provenance for the manuscript and its post-sale exportation to Japan have compounded the more basic challenges facing a scholar wishing to compare the handwriting in the manuscript with specimens from a determinately proximate era—only four of which exist.Footnote 31

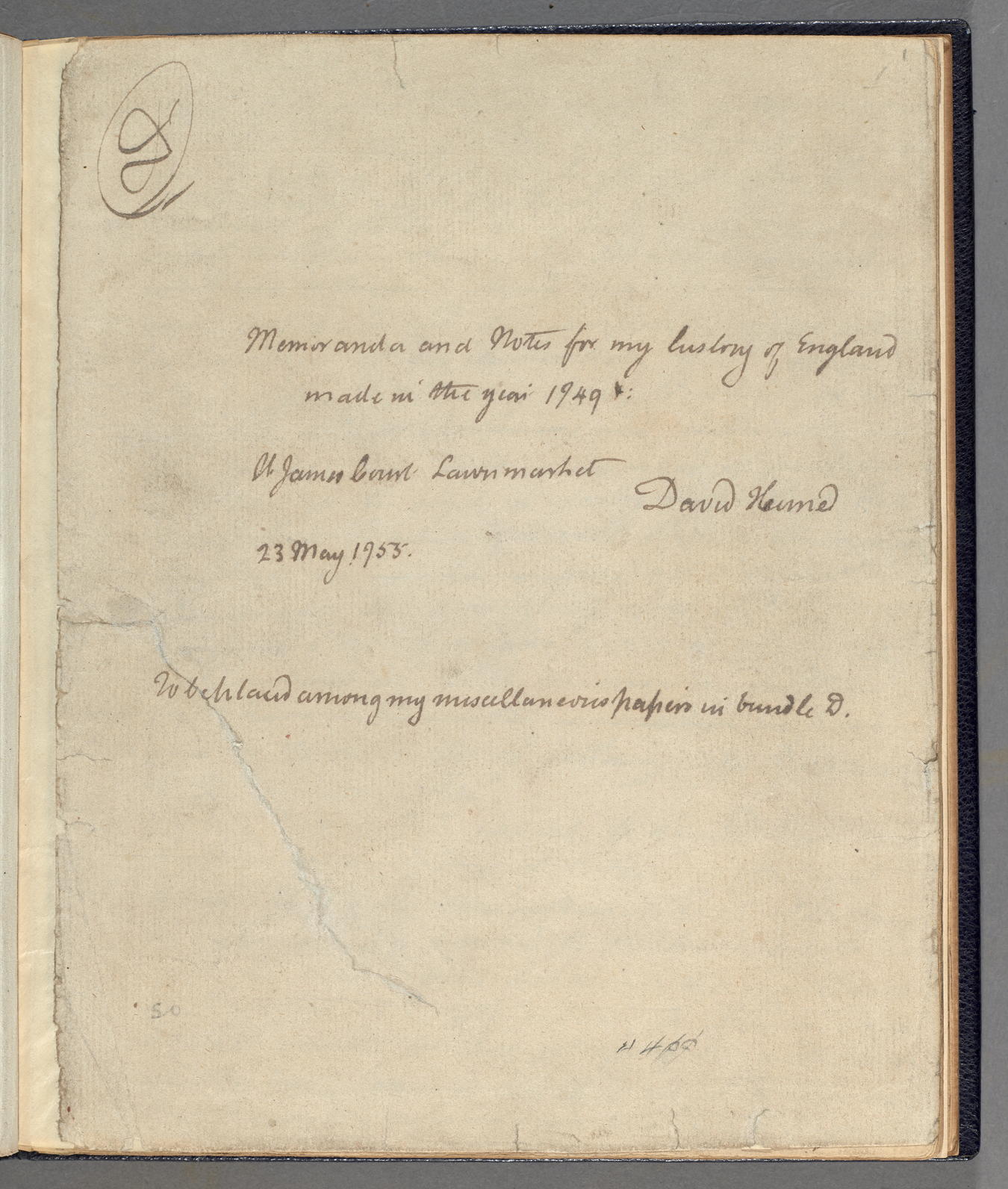

Other cases point to the difficulty in seeing past irregular forms of handwriting, where the provenance and content of a manuscript otherwise align with a scholar's expectations. In 1953, A. N. L. Munby, the librarian of King's College, Cambridge was shown an unpublished letter (figure 2), purportedly in Hume's handwriting, by Edith Margaret Chrystal, a Fellow of Newnham College. The letter, dated 16 January 1754, was addressed to “William Creech Esquire │ Publisher and Printer,” and signed “David Hume │ From my house, James Court.” Ernest Campbell Mossner included the letter in his and Klibansky's New Letters,Footnote 32 but only after he had privately contacted Munby to question its discordances: the handwriting in the letter did not resemble Hume's from 1754 or any other period; the addressee of the letter, supposedly the publisher William Creech (1745–1815), was implausibly young in 1754; and the valediction of the letter, “From my house, James Court,” defied the known date of Hume's move to James Court, Edinburgh, by eight years.Footnote 33 Notwithstanding these difficulties, Mossner concluded that the manuscript was authentic: the signature resembled Hume's; the direction to William Creech, supposedly in a different hand from the remainder of the letter, was merely the interpolated guesswork of a later collector; and the address, “James Court,” agreed with the dating and address in two sets of manuscript memoranda attributed to Hume, in the Huntington Library and the National Library of Scotland (figure 3).Footnote 34 Mossner was convinced that Hume's letter had actually been addressed to Andrew Millar (1705–68), Hume's publisher, and transcribed “in the hand of a clerk”—a practice that Hume had never otherwise adopted.Footnote 35

Figure 1 Census of Hume's Known Letters. Source: Hume, Further Letters of David Hume, 236–37. Note the use of [+ x] following a year indicates the number of undated letters that may conjecturally be assigned to the year.

Figure 2 A forged letter, dated 16 January 1754, attributed to Hume. JMK/PP/87/27/1, King's College Archive Centre, Cambridge.

In their correspondence, Munby and Mossner had contemplated the possibility that the “Creech letter” was a forgery. Munby confessed that it “would be difficult to see for what purpose such a document could be forged,” and Mossner agreed: “The theory of forgery I took, like yourself, little stock in from the beginning.”Footnote 36 This confidence in the purposelessness of a forgery was understandable. Unlike other forgeries, insinuated into the historical record as jeux d'esprit for the amusement of collectors, or as an arrogation of an author's intellectual authority, the “Creech letter” was neither amusing nor intellectually useful; it referred to matters that were impossible to explicate. In 1979, however, Alan Bell discovered that the historical memoranda used by Mossner as a form of substantiation for his surmise about the letter were the handiwork of Alexander “Antique” Smith (1859–1913), the prodigious Scottish forger, who had sold several faked manuscripts on the British autograph market in the 1880s and 1890s.Footnote 37 On closer inspection, the “Creech letter” was a collateral fake, produced by Smith with the same misdated place of origin (“From my house, James Court”) and the same characteristic flaws in handwriting and vocabulary.

Figure 3 A page of forged historical memoranda, dated 23 May 1755, attributed to Hume. MS 12263, fol.1r, Huntington Library.

Mossner's failure to recognize Smith's work was an explicable lapse when set against the transmission of an otherwise pristine corpus of manuscripts in Hume's handwriting. Unlike other Nachlässe, such as Tobias Smollett's, Hume's was free of demonstrated or alleged forgeries.Footnote 38 Instead, when manuscripts in Hume's autograph were discovered, they rarely exhibited the irregularities of a counterfeit or interpolation.Footnote 39 In 1958, a letter of 1735 from Hume to James Birch, written from La Flèche, was sold by Goodspeed's Book Shop, Boston, purchased by the University of Texas at Austin, and published by Mossner.Footnote 40 The letter provided an invaluable glimpse of Hume's life during the period in which he wrote A Treatise of Human Nature, and it had appeared with an unpublicized provenance in an unusual location. Any skepticism that might have arisen about this immensely important letter could be answered with reference to its unobjectionable content, handwriting, orthography, and paper. In 1963, Tadeusz Kozanecki announced his discovery of five letters in Hume's hand, dated between 1737 and 1776, in the Czartoryski Museum, Krakow, where they were preserved as a gift to Princess Izabela Czartoryska (1746–1835) from Hume the Younger, who had met Czartoryska during her tour of Scotland in 1790. The earliest letter, addressed to Hume's close friend Michael Ramsay (d. 1774), provided an extraordinary reference to Hume's philosophical reading during his stay in La Flèche, in a manner unparalleled by any other extant item of Hume's correspondence. In describing his philosophical writing, Hume encouraged Ramsay to “read once over le Recherche de la Verité of Pere Malebranche, the Principles of Human Knowledge by Dr Berkeley, some of the more metaphysical Articles of Bailes Dictionary … [and] Des-Cartes Meditations.” “These books,” Hume added remarkably, “will make you easily comprehend the metaphysical Parts of my Reasoning.”Footnote 41 This manuscript, recovered against scholarly expectations in another unusual location, was particularly susceptible of skepticism about its authenticity, since it provided a solution ex machina to a debate commenced by Richard Popkin in 1959 surrounding Hume's knowledge of Berkeley's “idealism.” Without the evidence provided by Kozanecki, Popkin had insisted that the evidence for Hume's familiarity with Berkeley's works was reducible to three nebulous references in Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature, Philosophical Essays Concerning Human Understanding (1748) and his essay “Of National Characters” (1748).Footnote 42 Yet the manuscript was verifiably Hume's, on the same basis as the Goodspeed's letter of 1735: its content, handwriting, orthography, and paper.

Within this narrative of discovery, the conceit of Michael Morrisroe's submissions to the Philological Quarterly and English Studies was unremarkable. Two letters by Hume had lain hidden in private collections since the eighteenth century and they were now brought to light by the activities of an inquisitive scholar. In his introductions to both articles, Morrisroe provided an overview of the significance of his discoveries for existing and prospective research on Hume's life and thought. The letter to Millar showed that Hume “actually did begin gathering works on the subject of ecclesiastical history” in 1765, when scholars had otherwise “dismisse[d] the thought entirely.”Footnote 43 The letter to Ramsay of 1734 reinforced the case against Popkin. Hume refers again to his familiarity with “the Principles of Human Knowledge by Dr Berkeley.”Footnote 44 Yet where Kozanecki's discovery had shown that Hume was merely familiar with Berkeley's Principles, the letter discovered by Morrisroe referred explicitly to Hume's repeated “reading” of the same work. Unlike Hume's letter of 1737, which had allowed others to quibble over his direct or mediated knowledge of Berkeley's philosophy,Footnote 45 this “conclusive proof” was not “rebuttable.”Footnote 46 In Morrisroe's judgment, his discovery revealed that there could be “no doubt” that Hume had read Berkeley.

Morrisroe's Discoveries

Morrisroe was born in 1939. He completed his doctorate in English at the University of Texas at Austin in 1966, after degrees from Manhattan College and the University of Alabama. His doctoral committee consisted of his supervisor, Ernest Campbell Mossner, and three other members of the departments of English and philosophy: Joseph E. Slate (1927–2014), David J. DeLaura (1931–2005), and Frederick H. Ginascol (d. 1999). The subject of Morrisroe's doctoral dissertation was Hume's use of rhetoric in the Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion and the other dialogic passages in Hume's works; the preface to the dissertation described its argument as an attempt “to show how the dialogues, especially the Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, evidence Hume's ability to present difficult and controversial concepts to a potentially hostile reader in such a way that the hostility of the reader is mitigated while his intellectual horizons are expanded.”Footnote 47 This argument was reiterated in articles that Morrisroe completed for two academic journals,Footnote 48 and in a contribution to Mossner's Festschrift, published conjointly by the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Edinburgh in 1974.Footnote 49 Soon after completing his doctorate, Morrisroe was appointed as an assistant professor of English at the University of Illinois, Chicago Circle.Footnote 50 He stayed in this post for at least five years (1967–1972) and offered such courses as “The Eighteenth-Century Novel” (fall 1967), “Introduction to Fiction” (spring 1970), and “English Prose of the Eighteenth Century” (spring 1971).Footnote 51 In the same period (1967–1970), Morrisroe completed a JD at John Marshall Law School. In 1969, he published an article in the school's Journal of Practice and Procedure,Footnote 52 and he was soon after admitted to practice as an attorney by the Illinois Supreme Court.Footnote 53 There is no record of Morrisroe's employment as an assistant professor of English at the University of Illinois after 1973, but he appears to have retained a significant interest in eighteenth-century literature for the remainder of the decade. In 1970, he founded Enlightenment Essays, a periodical that he edited until 1980, which would publish dozens of short articles by numerous contributors, including two articles and several book reviews by Morrisroe himself.Footnote 54 In the years since their first appearance, Morrisroe's contributions to eighteenth-century scholarship have attracted a measure of commentary and approbation from several Hume specialists and historians of philosophy.Footnote 55

In reporting his discovery of two Hume manuscripts, Morrisroe had every confidence that his claims would be received seriously, as one might expect for a faculty member at a prominent university who had studied under the world's foremost expert on Hume's life and circle and who now served as editor-in-chief of a respectable academic periodical.Footnote 56 Questions could be raised about Morrisroe's failure to publish a facsimile of the manuscripts, but this might also be said to have surpassed the reasonable expectations of contemporary peer reviewers or readers. Researchers, as much today as in 1972–73, are not always in a position to arrange for the photographic reproduction of manuscripts, particularly when the request might offend the preferences of a private owner. Other scholars had transcribed Hume's manuscripts in private collections without publishing facsimiles and their practice had not provoked suspicion. In 1962, Mossner himself had published seventeen letters from Hume to Patrick Murray (1703–1778), Lord Elibank, without identifying their owner or location and without photographic evidence in corroboration.Footnote 57 Any difficulty surrounding the absence of a facsimile or consultable originals could be obviated by a presumption of Mossner's good faith, particularly when this presumption was combined with a plausible account of the letters’ past and present ownership.

In both articles, Morrisroe reported the provenance of his discoveries as follows:

Letter 1 (Philological Quarterly)

I am grateful to the late Ronald H. Miller, administrator de bonis non, cum testamento annexo, of the estate of Patrick J. Kelly, City of Chicago, County of Cook, State of Illinois, for permission to make a typescript of this letter and to publish it for scholarly purposes. The letter is one of a collection of forty-seven letters by eighteenth-century personages. Sold by the estate through brokerage auction, the present location of the letters is unknown.Footnote 58

Letter 2 (English Studies)

I am grateful to the late R. H. Miller, esq., administrator de bonis non cum testamento annexo of the estate of P. J. Kelly for permission to make a typescript of the letter. It is my belief that the letter was subsequently purchased for the New York Morris Collection.Footnote 59

Where Hume's letters are accessible in public or private collections, their provenance is rarely of significance to the purposes of a researcher. Yet the location of the letters published by Morrisroe and the identity of their owners remain unknown—and the provenances above are the only clues we now possess to the mystery of the letters’ fate after 1972–73.

Both are credible provenances: Morrisroe was apprised by a man named Ronald H. Miller that the estate of Patrick J. Kelly of Chicago, Illinois, preserved two letters by Hume; Miller was Kelly's executor, appointed de bonis non cum testamento annexo (that is, on the death of the decedent's original executor); the letters were sold at “brokerage auction” as part of a larger collection of eighteenth-century manuscripts; and one of the letters may subsequently have entered the “Morris Collection” of New York. There are several inferences that can supplement these details. The first is that Kelly had died in Chicago within two or three years of the publication of Morrisroe's article in 1972, or Morrisroe's arrival in Chicago. In Morrisroe's curriculum vitae, dated August 1966 and appended to the typescript of his doctoral dissertation, he notes that he “plan[ned] to reside” in Chicago “upon his graduation from The University of Texas,” and he does not refer to a pre-existing connection to Chicago or Illinois. The second inference is that Miller had also died in Chicago, and that he had practiced as an attorney in the state of Illinois—a claim that must arise from Morrisroe's use of the post-nominal courtesy “esq.” in reference to Miller. The final inference is that the deaths of Kelly and Miller would have been recorded in probate records in Cook County. It would also be reasonable to assume that Miller's admission to the Bar of Illinois would be recoverable from court or bar records, and—if he were not admitted in Illinois—that his appointment as an executor would be documented in probate proceedings, in accordance with a provision in Illinois state law ca. 1972 requiring the appointment of non-resident executors de bonis non cum testamento annexo to be approved by a probate court.Footnote 60

A number of objections could be raised against these inferences. It is possible, for example, that Kelly's estate was subjected to protracted legal wrangling, and that Kelly himself had died decades before 1972. It is possible that Morrisroe's use of “esq.” to refer to Miller was an extraneous courtesy rather than a reference to Miller's profession. It is possible that Kelly and Miller had resided in Chicago and died elsewhere; the reportage of their deaths, and the administration of their estates, would be recorded outside Chicago or Illinois. These are all reasonable objections, which are unanswerable: the details of the provenances are not exact enough to scrutinize. Yet the following are worth stating: the Supreme Court of Illinois and the standard directories of legal practitioners in Illinois (Sullivan's Law Directory and Martindale–Hubbell) possess no record of an attorney named Ronald H. Miller at any time during the twentieth century; the probate archives of the Cook County Clerk of Court possess no record for the death of an individual named Ronald H. Miller between 1964 and 1974 or the appointment of such an individual as an administrator de bonis non cum testamento annexo; the same archives do not possess a record for the death of a Patrick J. Kelly between 1964 and 1974; and no reference can be found to a relevant “Morris Collection” of books, manuscripts, or literary material in New York.

These difficulties may be explicable. In addition to the explications mentioned above, it is possible that elements of the provenance were misreported by Morrisroe or intentionally distorted, at the request of Miller or an unnamed third party. Leaving aside either concession, however, the questionable contents of the letters raise significant objections of their own. Both letters are transcribed below, with the addition of superscript capital letters, which will be used for reference in the discussion that follows:

Letter 1—Hume to Michael Ramsay, 29 September 1734

ARheims. Sept. 29 1734. N.S.A

Dear Michael

It was with mild Surprize that I receiv'd your Letter Bdated atB London. I hope that the Business which you Cwrit ofC in the Postscript will be concluded with such Benefits to Both Partys as you expect. It is with an DAbundance of PleasureD that I contemplate the Success of your EUndertakingE. The Letter Frequested ofF me is enclos'd.

GI am resolvedG before the Hpost go awayH to tell you of the Library to which I am admitted here in Rheims. I was recommended to the Abbé Noel-Antoine Pluche, which most learned man has opened his fine Library to me. It has all IAdvantages for StudyI and particularly holds an Abundance of Writings of both the French and English along with as complete a JselectionJ of the Classics as I have seen in one place. It is my Pleasure to read over again today KLocke's Essays K and the LPrinciples of Human Knowledge by Dr. BerkeleyL which are printed in their Moriginal stateM and in French copy. I was told by a student from the University who attends to the order of the Library that his Master received new works of Learning & Philosophy from London and Paris each month, and so I shall feel no want of the latest books.

We shall expect Success from your Undertaking and await your Letter with Curiosity.

Your affectionate Friend,

D. H.Footnote 61

Letter 2—Hume to Andrew Millar, 26 August 1765

Dear Sir

I am much obligd to you for the Copy of Fitz-Osborne's Letters. It was received in good order at NLord Hallifax's Office.N You are again anxious after my ecclesiastical History. The Reports that you hear should be Oput asideO as you know the facts of the matter and my resolve never to undertake a History which wou'd expose me again to PImpertinence & Ill-manners.P The Prejudices of all factions have not so far subsided that a History wrote with a Spirit of Impartiality could withstand the QRage & Clamor.Q

I have, however, been gathering most of the Works of Authors in France and England of the History of the Church, and I should be glad if I have the Leizure to read over them. RAn Account of some Periods in ecclesiastical History might be put beyond Controversy, and if one Volume were successful then the others might be composed: But I do not think it so near a Prospect.R

I send you enclosd Sa Bill on Mr CouttsS for 3 pounds four Shillings, which after adding the Price of the Letters is the Ballance I owe you. My Compliments to Mrs Millar. I am Dear Sir

Your most obedient Servant

David HumeFootnote 62

In phrasing and vocabulary, the letters are prima facie indistinguishable from other products of Hume's pen. Indeed, the addressees, Michael Ramsay and Andrew Millar, Hume's publisher, were recipients of other letters in which Hume adopted similar or identical phrasing. The form of date used in Letter 1 (superscript A), and the phrase “dated at” (B), are identical to Hume's forms and wording in another letter to Ramsay of 12 September 1734.Footnote 63 The phrase “writ of” (C) is used only once again in Hume's extant letters, manuscripts, and publications, in a letter to Ramsay of 4 July 1727.Footnote 64 The phrase “post go away” (H) also appears only once again, in the aforementioned letter to Ramsay of 12 September 1734.Footnote 65 In Letter 2, the phrases “Impertinence & Ill-manners” (P) and “a Bill on Mr Coutts” (S) appear uniquely in a letter to Millar of 14 January 1765.Footnote 66 Similarly, the phrase “Lord Hallifax's Office” (N) appears uniquely in a letter to Millar of 4 May 1765.Footnote 67 Other phrases appear uniquely in letters to different correspondents: “Abundance of Pleasure” (D) and “Advantages for Study” (I) appear in a letter from Hume to his childhood friend James Birch of 12 September 1734.Footnote 68 Then there are the phrases used by Hume on several different occasions: “I am resolved” (G) appears five times in Hume's extant letters, including in a letter to Ramsay of 3 July 1751;Footnote 69 “near a Prospect” (R) appears twice in Hume's extant letters, including in a letter to Millar of 18 December 1759; “undertaking” (E) appears dozens of times, including in a letter to Ramsay of 22 February 1739.Footnote 70 Even phrases with no exact matches in Hume's letters, such as “Rage & Clamor” (Q), “put aside” (O), or “requested of” (F), approximate his wording in letters and writings on similar subjects.Footnote 71 The effect is of a compelling symmetry between Morrisroe's two letters and Hume's stylistic inclinations. Yet there are also phrases that entirely defy Hume's practices and eighteenth-century conventions in general. The phrase “original state” (M) does not appear in any of Hume's extant letters—and its apparent meaning, in reference to the original language or edition of a publication, is unattested in Hume's manuscripts and publications, and in optical-character-recognition searches of early-modern and eighteenth-century texts.Footnote 72 The word “selection” (J) does not appear in any of Hume's extant letters, manuscripts, or publications—and its apparent meaning, in reference to a number of items (“a selection of the Classics”), instead of the act of “selecting” (“my selection of a book”), is a solecism in English, ca. 1734. The first recorded use of “selection” in reference to a number of items in the Oxford English Dictionary (“selection,” 2a) is dated 1805.Footnote 73

Quite apart from stylistic considerations, the events described in both letters present several unaccountable divergences from the historical record. Letter 2, in this respect, is less objectionable. It refers directly to a letter to Millar of 4 May 1765, first printed by Burton in 1846,Footnote 74 in which Hume asks for a copy of William Melmouth the Younger's pseudonymous Letters on Several Subjects (1748–9) (“Fitz-Osborne's Letters”) to be sent to the British embassy in Paris—Hume's place of residence between August 1763 and January 1766—via the office of George Montagu Dunk (1716–71), Lord Halifax, secretary of state for the Southern Department. Yet a number of other statements in the letter are curious. Hume has sent a payment to Millar, drawn on his account with Coutts Bank, which is not registered by Hume's extant customer account ledger.Footnote 75 Hume has asked Millar to provide him with “most of the Works of Authors in France and England of the History of the Church,” during the period of his appointment as chargé d'affaires to the British embassy (July–November 1765), when he could not reasonably have expected to commence work on a new historical project. Overlaying these incongruities is Hume's reuse of a phrasal combination that occurs, uniquely, in a letter to Millar of 18 December 1759: “I fancy that I shall be able to put my Account of that Period of English History beyond Controversy. I am glad you have so near a Prospect of a new Edition.”Footnote 76 Six years later, Hume expresses these sentiments in unusually similar terms (R): “An Account of some Periods in ecclesiastical History might be put beyond Controversy, and if one Volume were successful then the others might be composed: But I do not think it so near a Prospect.” Although Hume was prone to the repetition of phrasing in letters sent on the same day and subject,Footnote 77 verbatim repetition of multiple phrases after a hiatus of six years is startling. Finally, the fate of Hume's letters to Millar deserves notice: excepting one letter, preserved in the collection of James David Forbes (1809–68) in the University of St. Andrews, every extant letter from Hume to Millar is held within the Royal Society of Edinburgh's Hume bequest, owing—presumably—to the retrieval of the letters from Millar's family by Hume himself or Hume the Younger.Footnote 78 It is certainly possible that a second letter escaped retrieval or was subsequently removed from the collection, but that such a letter would appear in Chicago in ca. 1972 is more vulnerable to disbelief, especially in the light of its several peculiarities in content and wording, its unverifiable provenance, and its absence from the standard indexes of manuscript sales in North America and the United Kingdom in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.Footnote 79

In comparison with the deficiencies in Letter 2, the knowledge of which require some familiarity with the arcana of Hume's finances and the posthumous custody of Andrew Millar's letters, those in Letter 1 reveal themselves under brief inspection. Hume refers implausibly to Locke's Essays (K), plural, when he must intend Essay, singular.Footnote 80 He reports that he has consulted a French translation of Berkeley's Principles of Human Knowledge, when a translation into French of Berkeley's Principles was not published until 1889.Footnote 81 It could be answered that Hume had blundered in writing “Essays,” or that he had erred in referring to a “French copy” of Berkeley's Principles. It could additionally, or alternatively, be answered that Morrisroe faltered in transcription: the unitalicized title of Berkeley's “Principles,” in comparison with Locke's “Essays,” suggests an absence of fidelity to the manuscript. These counterclaims are, once again, irrefragable. Yet one feature of the letter is impossible to attribute to Hume's misstatements or to Morrisroe's incompetence in transcription. Hume notes explicitly that Noël-Antoine Pluche is a resident of Reims and the owner of a “fine Library” in that city. Hume refers to a meeting with Pluche, in person, “which most learned man has opened his fine Library to me.” These statements are either an astounding form of intentional mendacity on Hume's part or they are misinformed fabrications, characteristic of an inept forgery.

Reims, Lévesque De Pouilly, and Noël-Antoine Pluche

The association of Hume with Reims arises from the survival of two letters, dated 12 September 1734, one addressed to James Birch and another to Michael Ramsay. The letters are the first surviving evidence of Hume's travels in France between 1734 and 1737, following his departure from Bristol, where he had worked—briefly and with apparent dissatisfaction—for a merchant. Hume's letter to Birch was first printed by Greig in 1932, after its sale by Sotheby's in March 1920.Footnote 82 Hume's letter to Ramsay was first printed by Burton in 1846.Footnote 83 In both letters, Hume refers to his arrival in Reims and the advice he had received in Paris from Andrew Michael Ramsay (1686–1743), the “Chevalier Ramsay,” including a letter of recommendation “to a man”—residing in Reims—“who, they say, is one of the most learned in France.” Hume does not identify this “man” and states in both letters that he had yet to meet the “man” in person: “He is just now in the Countrey, so that I have not yet seen him,”Footnote 84 “the Gentleman is not at present in Town, tho’ he will return in a few days.”Footnote 85 In the letter to Birch, he adds the following qualification: “I promise myself abundance of Pleasure from his Conversation. I must likewise add, that he has a fine Library, so that we shall have all Advantages for Study.” In annotating the letter to Ramsay, Burton conjecturally identified the man as Noël-Antoine Pluche, “a native of Reims, the greatest literary ornament of that city,” and offered a précis of Pluche's intellectual sympathies: “His promotion in the Church was checked by his partiality for Jansenism. He had the rare merit of uniting to a firm belief in the great truths of Christianity a wide and full toleration of the conscientious opinion of others.”Footnote 86 In annotating the same letter, Greig rejected Burton's identification of the “man” as Pluche: “the Abbé,” Greig noted curtly, “had left Reims before Hume went to France.”Footnote 87

In the light of Greig's note, identifying Hume's contact in Reims became a matter of significant speculation, as it pertained directly to Hume's intellectual connections and reading during the period in France when he drafted A Treatise of Human Nature—a period about which we know “next to nothing.”Footnote 88 In 1942, Fernand Baldensperger made a case for identifying the contact as Louis-Jean Lévesque de Pouilly (1691–1750),Footnote 89 a member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, whose Nouveaux essais de critique sur la fidélité de l'histoire, presented to the Académie in 1724, resembled passages in Hume's “Of Miracles.”Footnote 90 In 1726, Pouilly returned from Paris to Reims, his place of birth, and resided there in 1734, the year of his only son's birth (March) and Hume's visit (September). Pouilly possessed a home in Reims on the rue de Vesle and, through marriage, a chateau in Arcis-le Ponsart, thirty kilometers west of the city.Footnote 91 He corresponded with Ramsay's acquaintance Henry St. John (1678–1751), Viscount Bolingbroke on philosophical matters in 1720,Footnote 92 and his Théorie des sentiments agréables (first published in 1736)Footnote 93 was far closer in sympathy to Hume's Treatise than the natural theology of Pluche's Le spectacle de la nature, or the Christian apologetic of Pluche's Lettre sur la Sainte Ampoule et sur le sacre de nos rois à Reims (1719), which had sought to defend the miraculous story of the baptism of Clovis I (CE 508), according to which the Holy Ampulla of Reims was transported to the hands of Saint Remigius by a dove.Footnote 94 Like Bolingbroke, Pouilly's brother Gérard Lévesque de Champeaux (1694–1778) had frequented the Club de l'Entresol—the intellectual salon coordinated by Pierre-Joseph Alary (1689–1770) in Paris—between ca. 1724 and 1726, where it is conceivable that he formed an acquaintance with Ramsay, who was a fellow member.Footnote 95

In response to Baldensperger's claim, Mossner's Life of David Hume (1954) settled on Pouilly as the individual “who best fits Hume's rather thin description,” and neglected to mention Pluche or his candidacy in any form.Footnote 96 It was clear that Hume was interested in Pouilly's Théorie—a work that he would later own himself, and purchase for the Advocates Library in Edinburgh—in a way that he would never demonstrate for any work in Pluche's oeuvre.Footnote 97 Letter 1, however, exploded Mossner's surmise. In the second edition of his Life of David Hume (1980), Mossner quoted from Letter 1 at length and stated categorically that Hume's contact in Reims was “the Abbé Noel-Antoine Pluche.” Baldensperger's “conjecture,” he added, was “proved incorrect” by Morrisroe's discovery.Footnote 98 The resultant consensus has echoed Mossner's judgment. John Robertson's entry for Hume in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography notes that Hume received “several introductions” from Ramsay, “notably to the Abbé Pluche.”Footnote 99 In their work on Hume's intellectual development, Annemarie Butler, Roger L. Emerson, Ian Simpson Ross, Margaret Schabas, and several others have reiterated this particular claim:

• “While in Rheims, Hume enjoyed access to the library of Abbé Noel-Antoine Pluche. There he read and re-read various classics and contemporary works in French and English, including Locke's Essay and Berkeley's Principles” (Butler).Footnote 100

• “Indeed, while he was in France he had met a number of important intellectuals and had been given access to the library of the Abbé Pluche” (Emerson).Footnote 101

• “[T]he immediate attraction of Reims for Hume was that he had an introduction to its chief man of letters: the abbé Noël-Antoine Pluche” (Ross).Footnote 102

• “One leading savant at Reims, Noël-Antoine Pluche, provided Hume with access to his library” (Schabas).Footnote 103

The trouble is that Pluche did not reside in Reims in 1734.Footnote 104 Although he was born there in 1688 and had served a professor in its Collège des Bons Enfants from 1710,Footnote 105 Pluche had departed Reims for Laon in August 1717, where he acted as the principal of its Collège Municipal and found refuge from François de Mailly (1658–1721), the archbishop of Reims, who had attempted to purge Jansenists from the ranks of the city's clergy after the promulgation of the papal bull Unigenitus in September 1713. In Laon, Pluche received protection from Louis Annet de Clermont (1662–1721), the bishop of Laon, but Clermont's failing health, and the bull Pastoralis officii (August 1718), threatening excommunication for clerics who had refused to accept Unigenitus, forced Pluche's departure from the diocese in 1722.Footnote 106 According to the most significant authority on Pluche's life, the Éloge historique de Monsieur l'Abbé Pluche (1764) by Pluche's publisher Robert Estienne (1723–1794), Pluche left Laon for Rouen, fearful of a lettre de cachet for his intransigent Jansenism. In Rouen, Pluche served as a tutor to the children of Jean-Prosper Goujon de Gasville (1684–1755), the intendant of Rouen, and to the son of William Stafford-Howard (ca. 1690–1734), second Earl of Stafford.Footnote 107 His exact movements in the later 1720s are difficult to reconstruct, but he appears to have relocated to Paris before 1732, where he devoted himself to the composition of Le spectacle de la nature. From the evidence of Estienne, and a small number of surviving letters, sent from Paris,Footnote 108 Pluche resided in the city for the remainder of his life, writing the nine volumes of his chef d'oeuvre before retiring in 1749 to Ivry-sur-Seine and Varenne-Saint-Maur (Saint-Maur-des-Fossés), on the outskirts of the city.Footnote 109 Within two years of his death, an auction of Pluche's modest library was held in Paris. A published catalogue of the library listed the 1729 Amsterdam edition of Pierre Coste's French translation of Locke's Essay, but not a single work by Locke in English or by Berkeley, “in original state” or otherwise.Footnote 110 A probate inventory of Pluche's belongings recorded his profession as “Prêtre du diocèse de Reims,”Footnote 111 and a clause in his will stipulated that his belongings would escheat to the city of Reims in the event of the death of his principal beneficiaries,Footnote 112 but Pluche's connection to his place of birth was evidently limited after his exilic departure in 1717.

In 1992, Mouza Raskolnikoff noted in her remarkable Histoire romaine et critique historique dans l'Europe des Lumières that Pluche's recorded movements after 1717 presented a discrepancy for the apparent narrative in Morrisroe's letter. Raskolnikoff resolved the discrepancy by arguing that Hume, in Letter 1, had not claimed to have met Pluche in person, but—more precisely—to have had access to Pluche's library.Footnote 113 This theory is an ingenious response to the contrarieties presented by Letter 1, but it requires us to assume that Pluche resided in Reims in 1734, and temporarily maintained a library in the city, when no evidence can be found to support either assumption. Pluche's will does not refer to any properties in the city of Reims. Moreover, his library catalogue hardly reflects the “latest” of “Learning & Philosophy from London and Paris,” ca. 1734, unless one allows for significant deaccessions between the year of Hume's visit and the posthumous cataloguing of Pluche's library in 1763. Although Pluche owned several publications from 1732 to 1734, his holdings from this period were principally works on religious devotion or ecclesiology. Works of philosophy were limited to Edmond Pourchot's Institutiones philosophicae (Paris, 1733) and the third Earl of Shaftesbury's Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times (London, 1733), John Theophilus Desaguliers's A Course of Experimental Philosophy (London, 1734), Pierre Polinière's Expériences de physique (Paris, 1734), and unspecified numbers of Histoire et Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences (Paris, 1666–1750) and Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (London, 1716–1734).Footnote 114

A final—somewhat unusual—difficulty for the content of Letter 1 is presented by Hume's reference to “the Abbé Noel-Antoine Pluche.” Despite its prominence in studies of Pluche, “Noël” was not Pluche's forename at birth, either on its own or in combination with “Antoine.” According to Estienne, during Pluche's flight from a lettre de cachet in 1722, he adopted the pseudonym “l'abbé Noël” to evade persecution.Footnote 115 In the period of his residence in Rouen, Pluche reportedly used the pseudonym. Yet Pluche's will and the formal record of his burial continued to give his name as “Antoine Pluche,”Footnote 116 and the engraving of Pluche that Estienne prefixed to his Éloge historique de Monsieur l'Abbé Pluche of 1764 would use the same—merely binominal—form. Pluche's works and translations were either published anonymously in his lifetime or credited to “M. Pluche.”Footnote 117 His extant letters, when signed, uniformly adopt “Pluche” after the valediction.Footnote 118 Early biographical dictionaries referred to Pluche only as “Pluche, Abbé Antoine,”Footnote 119 with the significant exception of Joseph de La Porte's La France littéraire (1756), a biographical register of living gens de lettres, which used “Pluche, Noël-Antoine” in its entry for his writings.Footnote 120

De La Porte's choice has subsequently shaped the bio-bibliographical literature on Pluche,Footnote 121 but in the judgment of one of Pluche's early rémois biographers, its use is erroneous: Pluche's name was “Antoine,” tout court.Footnote 122 On the basis of this objection, Hume's reference to “Noel-Antoine Pluche” would reveal letter 1 to be the spurious product of a misunderstanding, inaugurated by de La Porte and perpetuated by scholars since 1756: Pluche could not possibly have introduced himself to Hume as “Noël-Antoine.” However, a significant piece of evidence definitively upsets this objection, in a way that incidentally establishes Pluche's place of residence in 1734. The only extant evidence of Pluche's use of “Noël-Antoine” as a forename is his attestation to the testament (14 December 1733 and 2 January 1734),Footnote 123 burial record (31 December 1733),Footnote 124 and inventaire après décès (11–13 March 1734) of the painter Robert de Séry (1686–1733) né Paul Ponce Antoine Robert of Sery-en-Porcien. The inventaire, signed “Noel Ant. Pluche,” refers to Pluche as “prestre du dioceze de Reims, demeurant à Paris, rue des Carmes, pa[roi]sse St Benoist,”Footnote 125 the same address Pluche would adopt in correspondence in 1743.Footnote 126 It is possible that Pluche maintained two addresses in 1734, one in Paris on the rue des Carmes, and another in Reims, but one would have to ask why he declined to acknowledge a residence in Reims in these attestations or any other extant document. The simple truth, as Greig noted in 1932, is that Pluche did not live in Reims during the period of Hume's visit, or after 1717.

Ad Fontes

In 1984, M. R. Ayers and Harry M. Bracken urged caution against the use of Letter 1. Ayers stated that “no weight” could be placed on the letter, “as long as it is unavailable to resolve any doubts about its authenticity.”Footnote 127 Bracken wondered whether Morrisroe “saw the original” of the letter and how he had established “Hume['s] authorship.”Footnote 128 In 2015, James Harris's Hume: An Intellectual Biography used an endnote to describe Letter 1 as a “hoax,” adding that “scope for scepticism” should exist about Letter 2. Harris maintained that his doubt about Letter 1 was the “consensus among Hume scholars.”Footnote 129 Yet this consensus, pace Harris, is nowhere to be found in print, aside from Ayers's and Bracken's tentative reservations. Indeed, the forgeries published by Morrisroe are so tightly interwoven with scholarship on Hume's life that Harris's biography commences its discussion of Reims with the claim that Hume's contact in the city was either Pouilly or “the Abbé Noel-Antoine Pluche.”Footnote 130 Where a consensus has emerged about Morrisroe's discoveries, it has been noted in private. In a draft introduction to their critical edition of Hume's Treatise, circulated among a small group of scholars in November 2000, David Fate Norton and Mary Norton expressed doubt about Mossner's reliance on Letter 1. “Regrettably,” they noted, “the location of the manuscript of this letter is not available for inspection, while the letter as published raises doubt about its authenticity.” One reviewer of the Nortons’ draft underlined this phrase and used a marginal annotation to refer to Morrisroe's later activities as an entrepreneur.Footnote 131 Between 1979 and 1983, Morrisroe was subpoenaed by Congress and investigated by a federal grand jury when he was accused of “complex” Medicare fraud.Footnote 132 The allegations against Morrisroe included the claim that he had “fabricated” patient records.Footnote 133

These doubts and allegations were never publicized by the Nortons; their discussion of Letter 1 was excised from the published text of their edition, and their subsequent publications do not discuss Morrisroe or Letter 1 in any form. Media coverage of the allegations against Morrisroe did not refer to his career as a scholar of Hume or to any of his academic activities. The separation of these two personae, the academic and the alleged perpetrator of a crime, may explain why Morrisroe's work has continued to enjoy the endorsement of scholars—including this author, whose Further Letters of David Hume (2014) recorded the presence of Letter 1 and Letter 2 in its census of Hume's “known” manuscripts. Yet whether Morrisroe's alleged activities later in life should have any bearing on the integrity of his scholarship is not in question. We must not rule out the deceptions of a third party: Ronald H. Miller, Patrick J. Kelly, or a latter-day Alexander “Antique” Smith. It is clear that Letter 1 contains a phrase—“the Principles of Human Knowledge by Dr Berkeley” (L)—that must have derived from the forger's acquaintance with recent scholarship on Hume, ca. 1964. The phrase is used by Hume uniquely in the letter to Ramsay of 1737 that Kozanecki published in 1963 and Popkin reprinted in 1964 for an anglophone readership.Footnote 134 It is quite possible that Morrisroe was the butt of a sophisticated ruse, conceived between 1963 and 1972 and facilitated by a man (Ronald H. Miller) who died during its execution. An alternative conclusion is that Morrisroe forged the letters himself, quilting together relevant phrases from authentic letters and passing off the confection as a “discovery.” But this is not a contention that the present article can endorse, given the limitations of the available evidence.

The implications of the story told so far may feel familiar. The misplaced good faith of a scholarly community, the authority conveyed by the appurtenances of “good” scholarship, the respectability afforded by the filtrations of peer review: all appear in other recent hoaxes, alongside routine enjoinders for safeguards against further abuse.Footnote 135 The exposure of the forgeries published by Morrisroe can only renew these calls for rigor in the assessment of sources, but it can also allow us to revise our suppositions about Hume's early life and later historical scholarship. We can now revisit the debate over whether Hume ever read the works of George Berkeley.Footnote 136 We can reopen the question of Hume's rémois acquaintance and give new credence to Baldensperger's conjecture.Footnote 137 We can reconsider why Hume might have abandoned his plans to write an ecclesiastical history.Footnote 138 And we can continue to rewrite Hume's biography, in the light of an ever-increasing body of new—authentic—sources.

The route to these implications may seem tortuous, the ardor applied in exposing the forgeries disproportionate to the questions at stake. It could be argued, for example, that Hume's supposed acquaintance with Pluche or his interest in writing an ecclesiastical history in 1765 have had a negligible effect on the interpretation of his thought. Correcting the historical record would warrant only an endnote or a parenthetical expression of doubt, alerting others to problems in “phraseology or other considerations,” as Ayers put it, in his brisk discussion of Letter 1 in 1984. In the case of the forgeries published by Morrisroe, this mode of correction has evidently failed; a conspicuous exposé is overdue. Yet the exposure of a forgery must always amount to more than the mere “righting” of an imposture. It is a reiteration of the importance of tools that are coeval with scholarship itself: text-critical analysis, historical bibliography, provenance research. The history of scholarship has long recognized the importance of these pursuits to the emergence of the humanities.Footnote 139 The ars critica or proto-philological forms of textual criticism were indispensable tools in the formation of modern scholarly research—and the recent neglect of its methods, in the waning vogue for critical editions, is the cause of warrantable anxiety among its surviving practitioners.Footnote 140 Inventories of “secondary sources” on Hume have long served students of his life and writings.Footnote 141 Yet considerable lacunae remain: we still lack a critical edition of Hume's correspondence, a comprehensive census of his manuscripts, and a systematic bibliography of his publications. Although forgers with sufficient expertise will find a means to exploit these absences, blithe confidence in a critical or “standard” text is no less hazardous. It is clear that the faith placed by scholars in the authority of Mossner's Life is a principal cause for the incessant citation of the forgeries’ extraordinary claims. If one possible justification of a forgery is that it may serve as a fillip for the revival of a discipline's best practices, an ironic justification—in this case, at least—is that it may remind us of Hume's banal maxim in “Of Miracles: “a wise man … proportions his belief to the evidence.”Footnote 142