Tattooing has taken place throughout human history. While it is impossible to trace a continuous history, there is evidence of tattooing as a voluntary practice in most cultures.Footnote 1 But like so much non-elite history, the practice was rarely documented. In this context, the remarkable evidence of convict tattooing in nineteenth-century Britain provides a valuable opportunity to explore the social and cultural significance of the practice. Despite some pioneering studies on the convicts transported to Australia, there is still much that we do not comprehend. It is unclear why convicts so frequently marked their bodies in ways that facilitated official surveillance, nor do we understand the complex mixture of sentiments expressed. Some contemporaries thought that tattooing was carried out by a criminal fraternity, with tattoos expressing their deviant identity. We suggest otherwise: convicts were by no means the only Victorians who acquired tattoos, and whereas nineteenth-century commentators tended to see the practice as indicative of savagery and criminality, the evidence suggests that tattoos expressed a surprisingly wide range of mainstream and indeed fashionable sentiments. The evidence we present further undermines the notion that convicts were members of a so-called criminal class, and instead supports our argument that tattooing was widely and increasingly practiced and indeed became generally acceptable in nineteenth-century society.

Historians have been aware of convict tattoos for decades. In the 1990s and early 2000s, prompted by the creation of the Australian Founders and Survivors project, which assembled a vast body of records pertaining to convicts transported to Tasmania between 1802 and 1853, Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, James Bradley, and others published a number of articles examining the phenomenon.Footnote 2 While recognizing the dangers of misinterpretation, of “the substitution of our voice for theirs,” these historians argued that the designs expressed a wide range of sentiments, giving us access to the “convict voice.”Footnote 3 Concurrently, reflecting wider interests in both history from below and the history of the body, studies examined the tattoos of American sailorsFootnote 4 and, remarkably, the craze for elaborate body markings among British elites from the late 1880s to the late 1890s.Footnote 5 On a broader canvas, Jane Caplan's influential edited collection, Written on the Body, expanded the focus both chronologically and geographically, establishing the fluctuating presence since antiquity of tattoos as emblems of identity and markers of difference in both Europe and North America, often drawing on influences from non-Western cultures. Contrary to the much-repeated claim that the revival of tattooing in the West in the late eighteenth century was the result of the Pacific encounters during the “voyages of discovery” (notably those of Captain Cook), tattooing had long been present in Europe as well as in other cultures.Footnote 6

The studies published at the turn of this century rescued tattooing from perceptions of it as a marginal and insignificant practice and established that convict tattoos were expressions of agency that embodied diverse culturally significant meanings. But they primarily concerned convicts transported to Australia, and the phenomenon needs to be placed within the wider context of the history of tattooing. Where did the British and Irish men and women who were transported to Australia acquire the idea that they could mark their bodies? The evidence suggests that a high proportion of the tattoos convicts possessed when they arrived in Australia had been acquired during the long voyages on the transportation shipsFootnote 7; they may have been inspired by the sailors on board ship (an occupation with a long history of the practice), but the extensive nature of the tattooing suggests that convicts were already familiar with the practice before leaving Britain and Ireland. Caplan argues that by the early nineteenth century, tattoos “were already a normalized cultural practice” in Europe,Footnote 8 and this position is supported by the evidence presented here; yet we still know very little about the practice in Britain before the late nineteenth-century emergence of professional tattooing. Recent research on how tattooing has been shaped by fashion in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries usefully documents how the practice has become normalized in the past fifty years and examines its historical antecedents.Footnote 9

Studies of tattooing before the advent of photography, however, have suffered from significant limitations of evidence and problems of interpretation. Often obscured by clothing and worn by non-elites, the vast majority of tattoos in history were not documented, nor is there much evidence of the intentions behind those tattoos that were recorded. Systematic evidence of tattooing is rare, which is why the efforts by British judicial authorities from the late eighteenth century to record physical descriptions of convict bodies are so important. Prompted both by a general desire to better understand the criminal and the need to keep track of those who escaped or reoffended, authorities began to record physical descriptions of those accused of crime, including their height, hair and eye color, complexion, and distinctive marks. Appropriately, the systematic collection of this evidence started with the convicts transported to Australia from 1788, since the colony was in effect an open prison.Footnote 10

These are the records so effectively studied by Maxwell-Stewart and others, but historians have for the most part failed to recognize the wealth of the additional records of tattoos on convicts who were punished by imprisonment in Britain,Footnote 11 where physical descriptions can be found in prison registers, presumably to assist prison officers in the event of escapes. From 1881, more detailed records were kept in Registers of Habitual Criminals, established by the Metropolitan Police to assist in the enforcement of the 1871 Prevention of Crimes Act. This act required the police to supervise repeat offenders (guilty of two or more offences), and to facilitate such surveillance, the police kept registers of the physical appearance of convicts when they were released from prisons across England and Wales.Footnote 12

These detailed descriptions of imprisoned convicts have recently been assembled, along with those who were transported to Australia, in the Digital Panopticon web resource, which has made a wealth of evidence on the personal appearance of hundreds of thousands of convicts (and their encounters with criminal justice) accessible in digital form. Created to link a wide range of databases containing evidence of criminal convictions and punishments in Britain between 1780 and 1925, this metadatabase contains physical descriptions of convicts, including their tattoos, throughout the nineteenth century, recorded in the Newgate Criminal Registers (1791–1802), the records assembled by the Founders and Survivors project (1802–1853), the Millbank Prison Register (1816–1826), Prison Licenses (an early form of parole, 1853–1925), convict indents for men transported to Western Australia (1850–1868), and the Metropolitan Police Register of Habitual Criminals (1881–1925).Footnote 13

These records, extracted for this research from the larger Digital Panopticon resource into a separate database, form the basis of this article and are now available as a downloadable database; the data can also be searched on the Digital Panopticion website.Footnote 14 This database includes 75,448 written descriptions (no photographs are available) of tattoos on convict bodies, pertaining to 58,002 convicts, covering the period from 1791 to 1925.Footnote 15 It facilitates the largest investigation of the historical practice of tattooing ever undertaken.Footnote 16 It allows us to detect patterns both in the designs of tattoos themselves (the specific objects, words, and letters depicted, their subject matter, and their placement on the body), and, owing to the record linkage carried out for the Digital Panopticon project, the identities of those who wore them (gender, occupation, religion, date and place of birth, and convictions). Owing to the sheer volume of this data and its multiple sources, the assembly and analysis of this large body of information required the Digital Humanities methodologies of data extraction, multivariate quantitative analysis, and visualization.

We used a five-step process to extract, tabulate, and analyze the tattoo descriptions. First, using approaches derived from machine learning, we extracted evidence of tattoos from the personal descriptions of convicts, which contained a wide range of other information including physical characteristics (such as eye color, shape of face), bodily infirmities (lame leg, broken nose), and personal details (occupation, religion), in a variety of formats. The second step was to segment the evidence on tattoos so that the designs were associated with their body locations. The next and most interpretive part of the process was to assign subjects to the words identified as describing tattoos. This step was done manually and iteratively, paying attention to the contexts, as we came to understand more about the meanings of specific terms. We then linked this information to the biographical information in the convict's Digital Panopticon “life archive” (age, gender, occupation, offence, and punishment). Finally, collocation, correlation, and regression analyses of the data were visualized using R's ggplot2 visualization library.Footnote 17

The size and multidimensional nature of the data allow us to overcome some of the limitations of previous studies, whose authors had access to neither the wealth of records currently assembled nor the digital methodologies now available for analyzing them. Evidence from records covering more than a century of British history, on convicts from a broad range of backgrounds and occupations, allows us to map changing practices, and we can find out more about the holders of these convicts through the “life archives” of records assembled in the Digital Panopticon. Moreover, by using a number of visualization techniques, we can draw inferences about the intended meanings of the various designs, despite the terse descriptions and the fact that convicts left no records explaining their intentions.

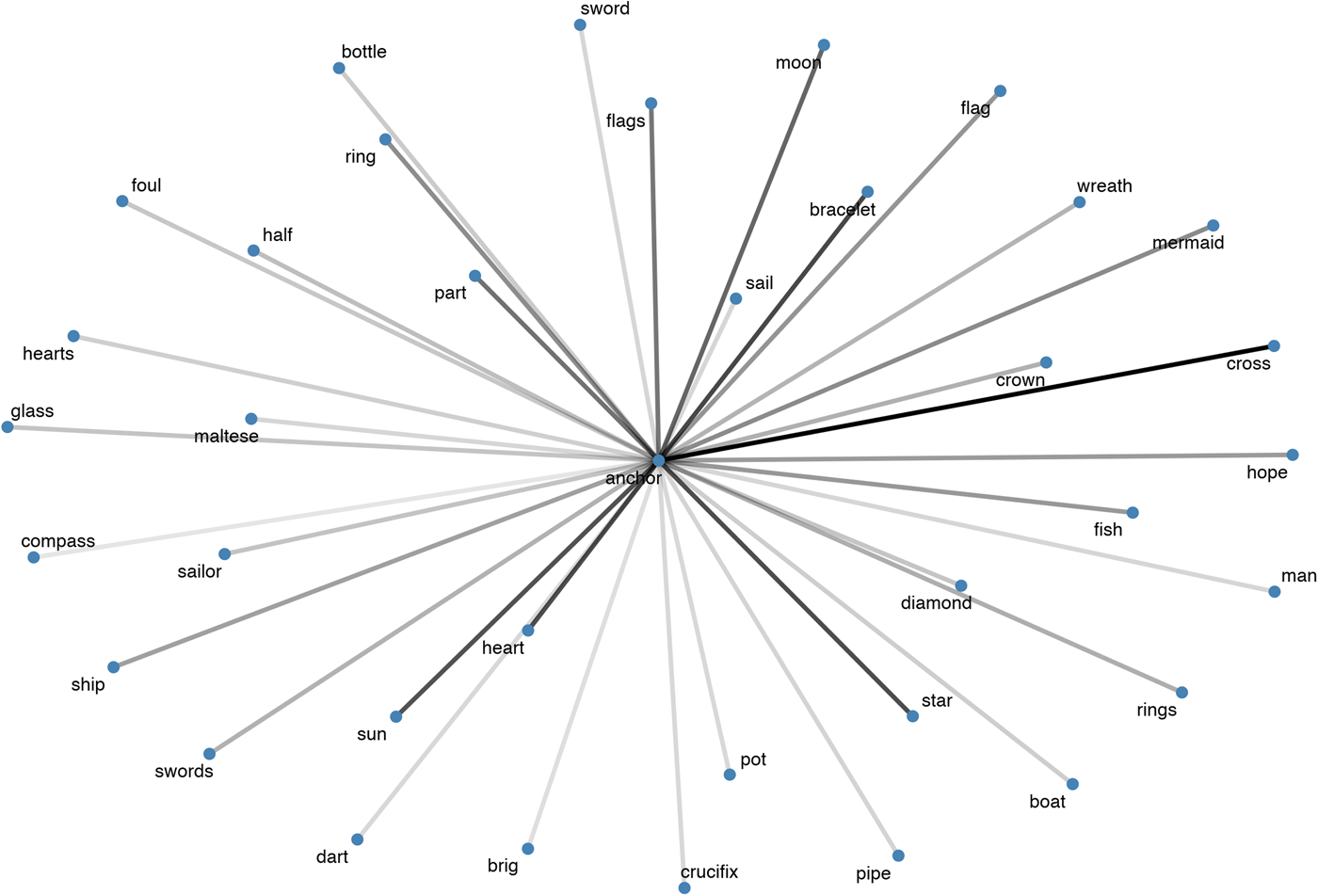

While we remain attentive to Maxwell-Stewart's warning not to impose our own interpretations, identifying designs collocated with each other, for example, is one way we can shed light on their meaning and significance.Footnote 18 Collocations for the popular image of an anchor (figure 1) indicate that it should not simply be interpreted as a reference to naval topics.Footnote 19 The strongest correlations (indicated by the darkest lines) indicate that anchors were frequently displayed along with hearts, bracelets, crosses, flags, and the sun, moon and stars, which suggests that anchors were used to express love and romance, religious devotion, national identity, and popular cosmological beliefs. Naval designs (such as ship, brig, boat, sailor), on the other hand, appear at about the same rate as their frequency in the corpus as a whole. This type of evidence allows us to better understand the wide range of sentiments expressed in convict tattoos. David Ingley, for example, who was imprisoned for the second time at the age of twenty-nine for theft in 1827, had anchors on both his arms, and rare sketches of his tattoos can be seen in the prison register (figure 2). On his right arm, two anchors were collocated with some initials (L.V.) and images of a face and a heart; on his left arm, the anchor was collocated with a heart, mermaid, and more initials (T.H.) We do not know the motivations behind Ingley's choice of tattoos, but it seems likely these were expressions both of love and of an affinity with things naval (given the mermaid).Footnote 20

Figure 1 Collocations for tattoo “anchor.”

Figure 2 Entry for David Ingley in the Millbank Prison Register, 1827, TNA, PCOM 2/60.

Trends, Designs, and Subjects, 1793–1925

Ingley is only one of the 58,002 convicts whose tattoos are recorded in the Digital Panopticon. A quantitative and qualitative examination of this vast database reveals that the widespread practice of tattooing included a diverse range of subjects and designs, worn by increasing numbers of convicts over the course of the nineteenth century. First, however, it is necessary to identify some basic characteristics of the data and to recognize their limitations. Recording practices varied between institutions and the records they kept and, no doubt, within them. Table 1 demonstrates that descriptions of convict tattoos in the earliest dataset, the criminal registers, were rare, reflecting the fact that keeping records of the personal characteristics of convicts was still at a very early stage.Footnote 21 But the far more detailed records of those transported to Tasmania in the first half of the nineteenth century demonstrate a high frequency of tattooing (approximately one-quarter of convicts had tattoos), while the highest rate of tattooing can be found in the Registers of Habitual Criminals from 1881 to 1925, where 42.6 percent of convicts were tattooed.

Table 1 Tattoos datasets extracted from the Digital Panopticon.Footnote 22

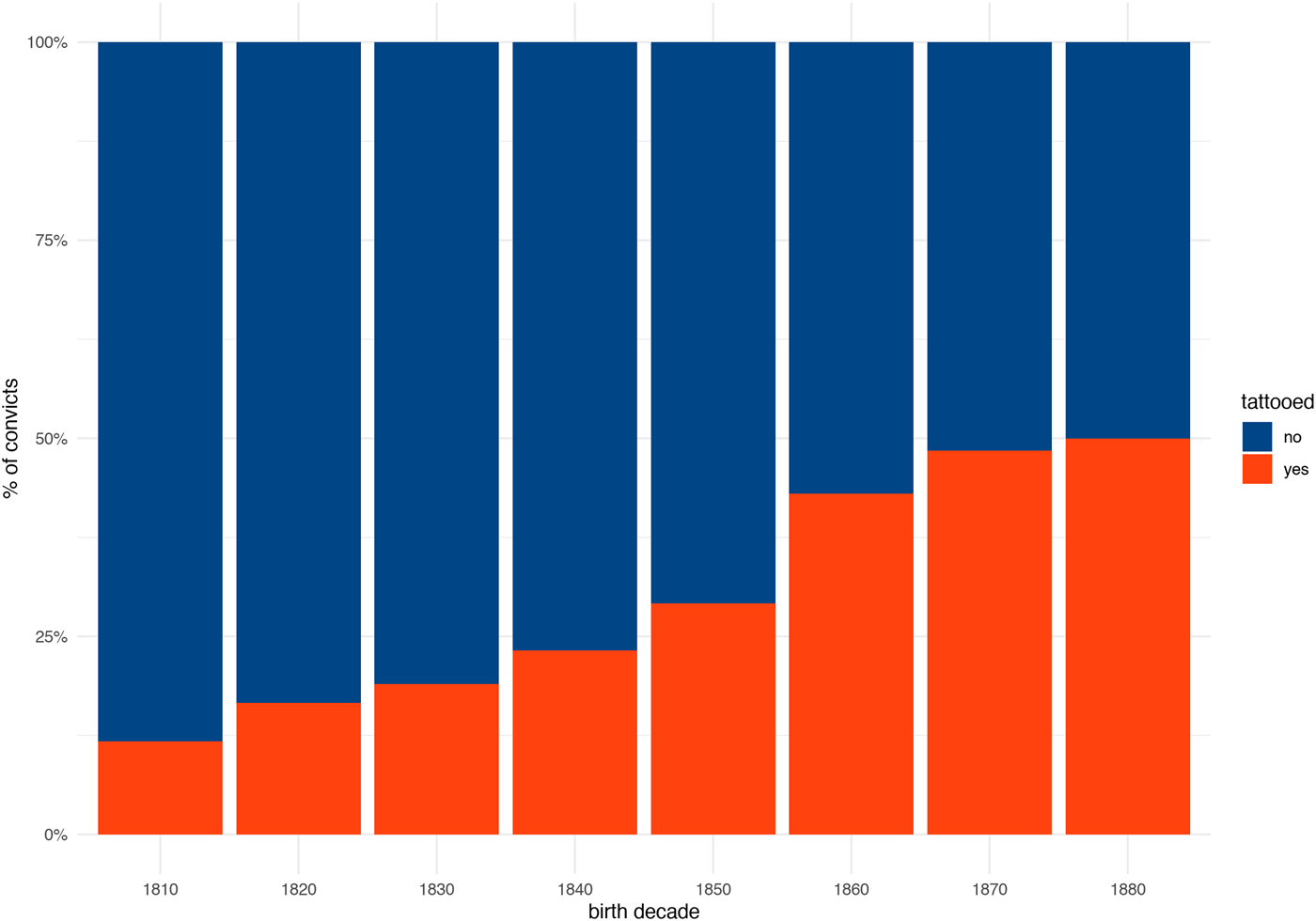

It is evident from table 1 that, with the exception of the convicts in the Registers of Habitual Criminals at the end of the century, those who were transported to Australia were more likely to be tattooed than those imprisoned in England, no doubt owing to the widespread practice of tattooing on the convict ships. The evidence further indicates that male convicts were more likely than female convicts to be tattooed (32.5 percent versus 12.5 percent), and that the proportion of imprisoned convicts who were tattooed increased over time, from 7.4 percent in Millbank Prison from 1816 to 1826 to 13.6 percent of those granted prison licenses (both male and female) from 1853 to 1887, to the 42.6 percent of convicts listed in the Register of Habitual Criminals, all of whom had been imprisoned. Given varied recording practices, it is useful to confine the evidence to a single dataset when examining change over time. Figure 3, based on the Register of Habitual Criminals, indicates that convict tattooing was a growing practice over the nineteenth century: the later that convicts were born, the more likely they were to sport a tattoo. Whereas only about one-tenth of those born in the 1810s had tattoos, this proportion increased to almost half of all convicts born in the 1880s.

Figure 3 Convicts with tattoos in the Metropolitan Police Register of Habitual Criminals, by decade of birth, 1810–1889.

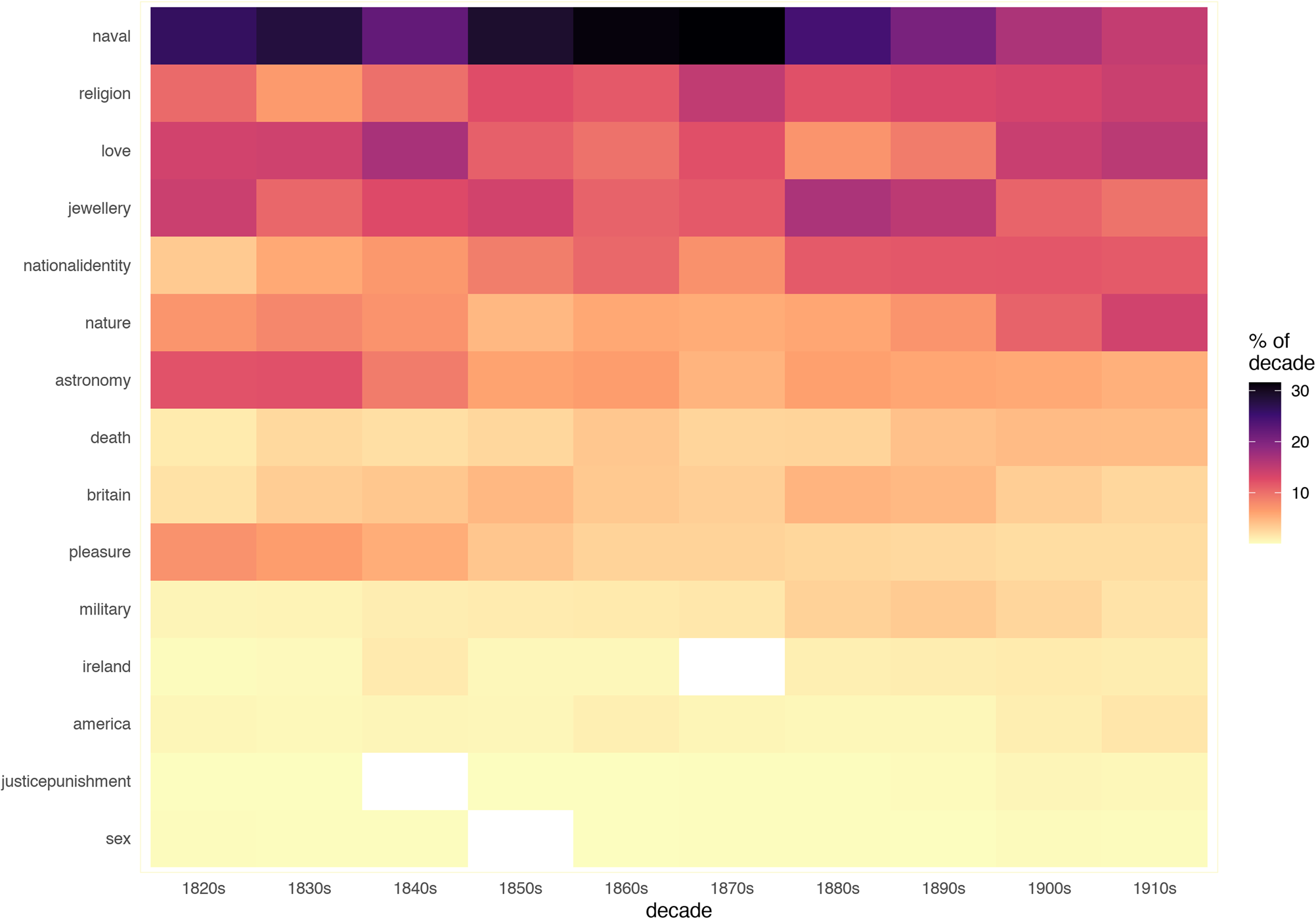

We have classified the tens of thousands of tattoos in the database into nineteen subject categories, reflecting the very wide range of designs recorded. Charting their incidence over time shows that over the course of the nineteenth century the range of subjects expanded. The most common type of tattoo is a name or set of initials; these are found in 41,832 tattoo descriptions (27.2 percent of all subjects). Figure 4 demonstrates, however, that names and initials accounted for a much lower proportion of tattoos from the 1880s onward than in the first half of the century.Footnote 23

Figure 4 Names and initials as a percentage of total tattoo subjects, 1821–1920.

The heatmap in figure 5 helps identify which additional subjects became popular. Lighter colors indicate lower proportions of tattoos in the relevant decade, so the declining color contrasts over time indicate a wider spread of subjects. From 1820 to 1850, when the vast majority of records are of transported convicts, designs predominantly concerned naval themes, love, jewelry, astronomy, and religion. In contrast, the later part of the period, which was dominated by imprisonment, saw an increase in tattoos relating to national identity, nature, and death. As discussed below, the increasingly broad mix of tattoos worn by men in a wide variety of occupations indicates that tattoos did not indicate a desire to stand apart from respectable society. Women's tattoos were on a narrower but still diverse range of subjects: more than three-quarters were of names and initials, and the most common others, in declining numerical order of importance, concerned love, jewelry, religion, and naval subjects.Footnote 25

Figure 5 Mixture of tattoo subjects by decade, 1821–1920.Footnote 24

For both sexes, the dominance in the first half of the nineteenth century of tattoos consisting of names and initials, maritime themes (including astronomy), jewelry, and expressions of love is indicative of a narrower focus on the experience of transportation. The fact that many convicts had their year of conviction or transportation tattooed on their skin reflects recognition of the fact that their forcible removal halfway around the world, probably never to return to Britain, would be a life-changing event.Footnote 26 Naval tattoos reflect the long voyage to Australia and perhaps the influence of the tattooed sailors who manned the ships. These tattoos include mermaids, ships, sailors, flags, and astronomical symbols like the sun, moon, and stars, but the most popular design is the anchor.

Convicts such as Thomas Prescott, transported to Australia in 1819 at the age of seventeen and a sailor, bore an “anchor mermaid heart and darts sun moon & stars” on his right arm, and “Man Woman Heart JP SJ laurel branch Star and other heart and dart” on his left arm.Footnote 27 Tattoos that expressed relationships with lovers, friends, and kin, worn in visible areas of the body such as Prescott's arms (many other convicts had them on their hands), were very popular, reflecting convicts’ forced separation from their loved ones. The names and initials that were so frequently tattooed on their bodies appear often to have been of family members (because they shared the same surname initial) or lovers: the “JP” on Prescott's left arm may have been a member of his family, while “SJ” may have been a lover. Where the tattoos were first names, they were much more likely to be the name of someone of the opposite sex than the same sex: female names account for 66 percent of the forenames in men's tattoos, and male names account for 72.9 percent of the forenames on women's tattoos. The initials “i.l.,” meaning “I love,” often preceded other pairs of initials or names of people of the opposite sex. Twenty-one year old William Graham, who was imprisoned in the new national penitentiary, Millbank, in 1826 and not transported, demonstrated his love for both his family and a sweetheart. He had what were likely the initials of family members and those of “E.C.” (probably his lover) and a heart and crossed arrows on his right arm, and his initials together with “E.C.” and “bird in a bush” on his left arm, as demonstrated in the sketch in figure 6, from the prison register.Footnote 28 We cannot know precisely what William intended to express with these tattoos, but undoubtedly love and affection were involved.

Figure 6 Entry for William Graham in the Millbank Prison Register, 1826, TNA, PCOM 2/60.

The other main traditional subject of tattoos was religion—unsurprisingly, given their historical use in pilgrimages and as emblems of commitment.Footnote 29 Almost one in five (19.8 percent) of tattooed convicts across the period wore tattoos with Christian meaning, primarily crosses and crucifixes. In addition, the most common tattoo design of all, the anchor, on 23.4 percent of tattooed convicts, appears to have frequently been used to express its Christian meaning as a mark of salvation.Footnote 30 As shown above (figure 1), anchors were frequently collocated with crosses. Figure 5 shows that religious tattoos were worn throughout the period; their prevalence and persistence reflects the continuing importance of religious sentiment in popular culture.Footnote 31 While specific religious symbols and expressions—such as Adam and Eve; the tree of life; the words faith, hope, and charity; and the initials i.n.r.i, i.r., and i.h.s. (references to Jesus)—were the subjects of hundreds of tattoos, far more common was a general and conventional expression of religious faith through the use of crucifixes, crosses, and anchors (the latter referencing the security provided by Christian belief). This lack of sectarian symbols is evident in the relatively minor differences between designs worn by convicts of different faiths. Other historians have suggested that Catholics were more likely than Protestants to have religious tattoos, particularly crucifixes.Footnote 32 But among the 1,304 tattooed convicts whose religion is known (8.2 percent), the cross and crucifix were only slightly more common among Catholics than among those affiliated to the Church of England and other Protestant denominations.Footnote 33

Like tattoos expressing love and familial attachments and maritime themes, religious tattoos were conventional markers of personal affinities that apparently had nothing to do with criminality. While these types of tattoos continued to be popular in the second half of the nineteenth century, figure 5 indicates that they were increasingly supplemented by designs on a much wider range of subjects as tattoos became more inventive and artistic and associated with contemporary social and cultural developments.

Tattoos featuring animals and flowers, for example, were present throughout the period but became more frequent from the 1880s. Birds, butterflies, horses, dogs, snakes, scorpions, and kangaroos all are featured. Frederick Ash, convicted in 1889 at the Old Bailey of the rape of a thirteen-year-old girl and sentenced to five years of penal servitude, was recorded in the Register of Habitual Criminals in 1893 (when he was discharged early) as having twenty-five designs on his body (depending on how the various objects are counted), including an elephant, mermaid, girl on a donkey, snake, lion, unicorn (apparently as part of a coat of arms), chameleon, scorpion, another lion, and a tree centipede.Footnote 34 Many animals and flowers, in addition to expressing an interest in nature, were used for decorative and symbolic purposes. Flowers were often collocated with animals, especially birds, or were tattooed around the wrist or neck to replicate jewelry.

Flowers were also used to express national identity—a subject of tattoos that, in parallel with wider political developments, increased in the second half of the century. British symbols such as the Union Jack (104), king (24), Queen Victoria (11), Britannia (101), Saint George (15), the Prince of Wales (76), and bulldogs (5) can be found, while identification with a greater British identity can be found in the frequent juxtaposition of a rose (England), thistle (Scotland), and shamrock (Ireland), which feature together on 410 convicts. A separate Irish identity can also be found with 266 convicts with harps, and 14 convicts with the words erin go bragh (Ireland forever). More surprisingly, a number of convict tattoos expressed an affinity for America, with thirty-four American eagles and forty-five stars-and-stripes designs. Only a few of these convicts were born in the United States, however, and it seems unlikely that a narrow nationalism was a major motivation for these tattoos. Instead, they were aligned with the working-class fascination with American culture in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain.Footnote 35 There were 1,393 convicts with crossed flags, and many wore symbols of more than one nation.Footnote 36 Stephen Smith, variously described as a clerk, miner, and laborer, had both a Union Jack and the stars and stripes on his left forearm.Footnote 37 In their use of multiple national symbols, convict tattoos represented a fairly broad patriotism in line with wider ambivalent attitudes toward popular imperialism and national identity in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain.Footnote 38

The objects recorded in late nineteenth-century tattoos also demonstrate awareness of fashions and recent inventions including steam engines, bicycles, parachutes, an airplane, and even a camera. Earlier, James Tamplin, a laborer convicted of housebreaking, celebrated the Victorian obsession with the railways: his prison license in 1856 documents that he bore a steam engine on his right arm.Footnote 39 Bicycles are typically depicted with a woman riding and seem to be associated with circus performers. In 1906, Joseph Sullivan, a laborer from Cork, had on his left forearm a “girl in tights throwing five bottles and [a] girl with cycle.”Footnote 40

Emblematic of the emerging association of tattooing with entertainment and performance are the 392 convicts in the database, all male, who wore a tattoo of the American showman Buffalo Bill. The first tour of Buffalo Bill's popular Wild West show toured Britain in 1887, when he gave a command performance for Queen Victoria; his London shows alone attracted 2.5 million customers. He returned for further tours over the next seventeen years, while his appeal was further enhanced through popular novels.Footnote 41 The emerging profession of tattooists appears to have taken advantage of his renown by developing templates of his image and offering the tattoo as part of the experience of going to the exhibition. The first convict with a Buffalo Bill tattoo was recorded in 1895,Footnote 42 with the remaining tattoos occurring from 1899 and throughout the early decades of the twentieth century. Given the dates of the British tours (1887–1904), it seems likely that many of these convicts acquired their tattoos long before their names appeared in the prison records.

If we look at the wide variety of other designs that convicts placed alongside Buffalo Bill, it appears that this tattoo was frequently associated with love. Tattoos of a bust of him were frequently collocated with women, a woman's head, and clasped hands, as with Charles Wilson, who had “two hearts (one pierced), clasped hands and an anchor” on his right forearm and a bust of Buffalo Bill and the name Maggie in capital letters in a scroll on his left forearm.Footnote 43 The frequent expressions of love collocated with Buffalo Bill tattoos suggest that men often went to the show with their lovers and obtained tattoos to commemorate both the visit and their love for each other (we do not know whether their partners were also tattooed). Keen on the latest fashions, some convicts drew upon contemporary art and aesthetic styles. For example, seven convicts combined a Buffalo Bill tattoo with the then fashionable exotic design of a Japanese woman.Footnote 44 Other cases demonstrate an interest in figures in the news: Buffalo Bill appears six times with General Baden-Powell, military hero and founder of the scout movement.

Defiance or Pleasure?

In contrast, many contemporaries thought tattooing was emblematic of far less respectable sentiments. In 1862, the social investigators Henry Mayhew and John Binny reported the testimony of the warder of Millbank Prison: “Most persons of bad repute . . . have private marks stamped on them—mermaids, naked men and women, and the most extraordinary things you ever saw; they are marked like savages, whilst many of the regular thieves have five dots between their thumb and forefinger, as a sign that they belong to ‘the forty thieves,’ as they call it.”Footnote 45

These remarks are an example of the penchant of some nineteenth-century observers to view tattooing as emblematic of savagery and criminality, fueled by their belief in the existence of a threatening criminal class.Footnote 46 While the association of tattooing with criminality reached a peak under the influence of Cesare Lombroso in the 1890s,Footnote 47 concerns about its use to express membership in criminal gangs date back to the late 1820s, when a series of juvenile thefts in London sparked anxieties about youth crime. The Morning Post complained about “a gang of no less than 40 juvenile delinquents . . . known as the ‘Forty Thieves,’ on all the metropolitan roads, where they subsist by their plunder on the coaches and passengers.”Footnote 48 The warder's comment that the “Forty Thieves” could be identified by their tattoos—“five dots between their thumb and forefinger”—was echoed by the London Standard, which claimed the gang was “distinguished by each of their fraternity . . . having a triangular kind of mark tattooed with gunpowder between the thumb and the first finger on the right hand.”Footnote 49

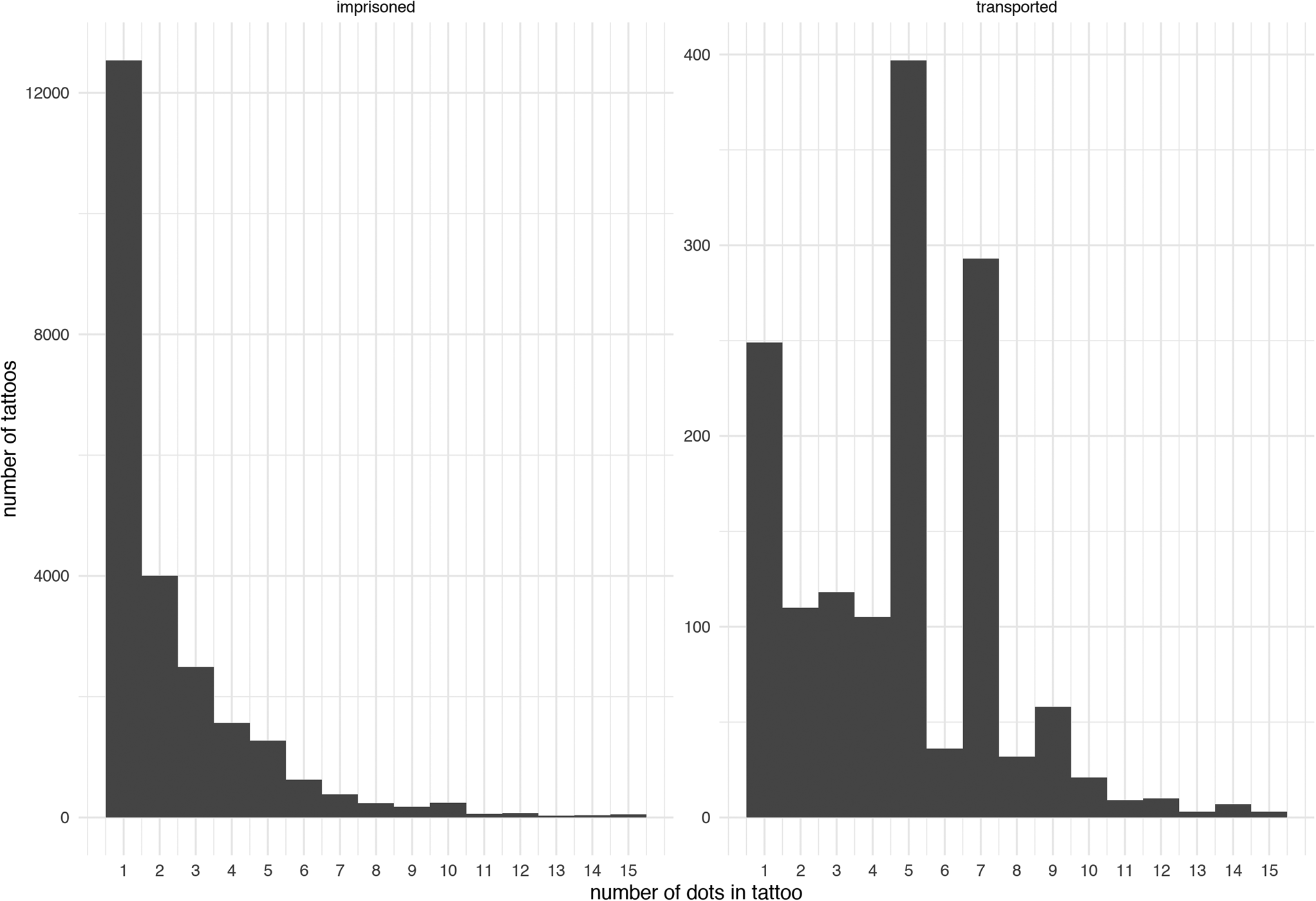

With the exception of names and initials, the dot was the most common form of tattoo, found in almost one-third of tattoo descriptions. More than twenty thousand convicts wore one or more dots on their arms, hands, and even faces. As the simplest tattoo to create, dots were hugely popular. The left side of the body was dominant, suggesting that they were often self-administered. A single dot, which in some cases might not even have been an intentional tattoo but instead a natural mark on the body or the result of an injury, was the most common. Of all the multiple-dot tattoos, five and seven dots predominated.

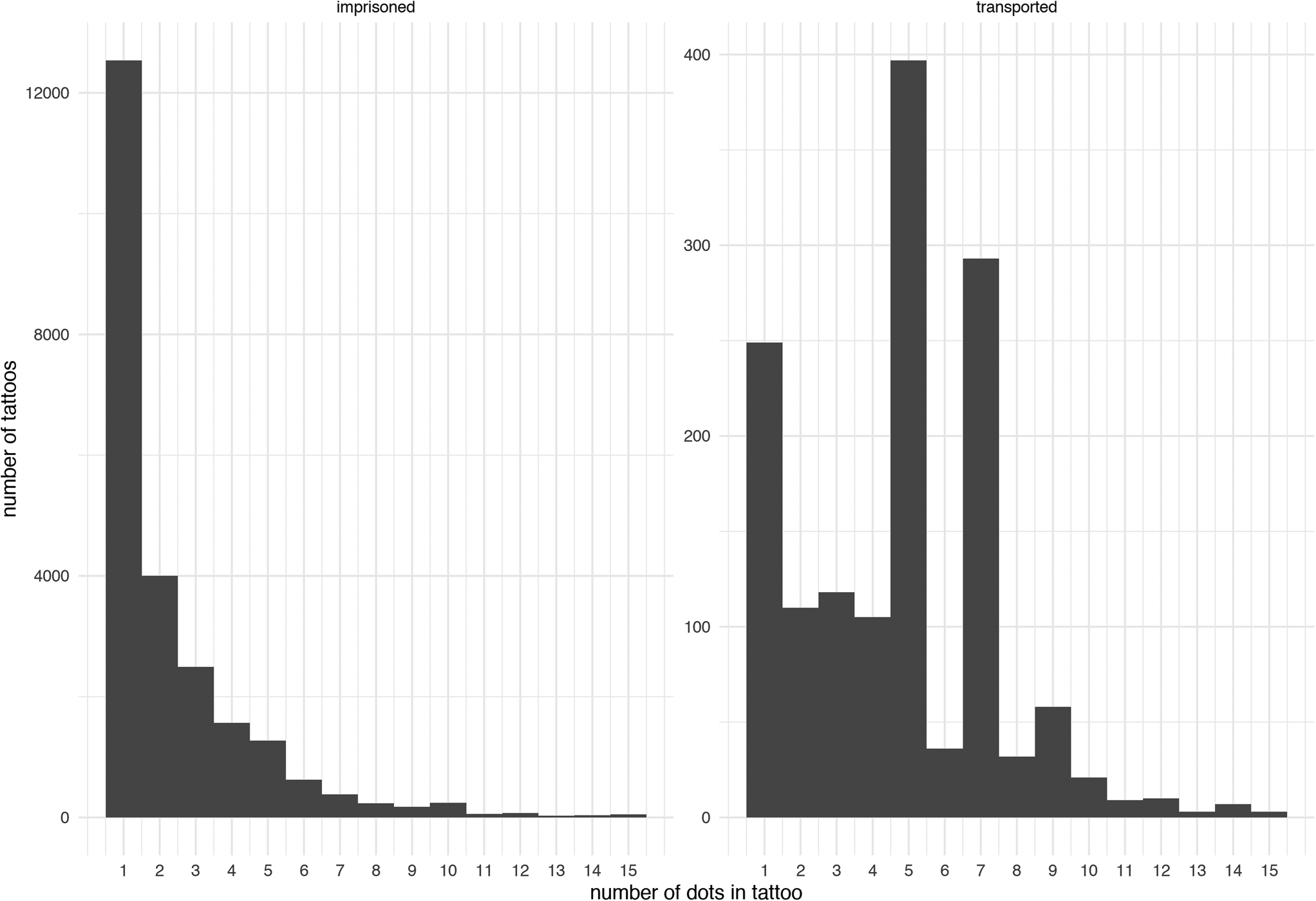

While, as contemporaries claimed, it is possible that tattoos such as the five dots could have been used by some convicts to attest to their criminal identity and gang allegiance, evidence of this practice is limited. In their study of habitual offenders, Godfrey, Cox, and Farrall found that “a single dot between thumb and finger seemed to indicate that the wearer had been imprisoned at some time, and two dots seemed to indicate that time had been served in a juvenile reformatory as well as prison.”Footnote 50 But the sheer volume of one- and two-dot tattoos (12,789 single dot, 4,110 two dots), and the fact that the most popular body location by far was the forearm, not the hand, suggests that there were many other possible meanings. Similarly, the widespread use of five dots suggests that any gang could not have been easily identified by this tattoo alone (and the term forty thieves does not appear in any tattoo). If we investigate the data in more detail, it appears that these tattoos were most often created in different contexts from those described by Mayhew and the newspapers. Most importantly, they were proportionally more likely to occur on those who were transported than those who were imprisoned, as demonstrated in figure 7.

Figure 7 Number of dots in tattoo descriptions for imprisonment versus those for transportation.

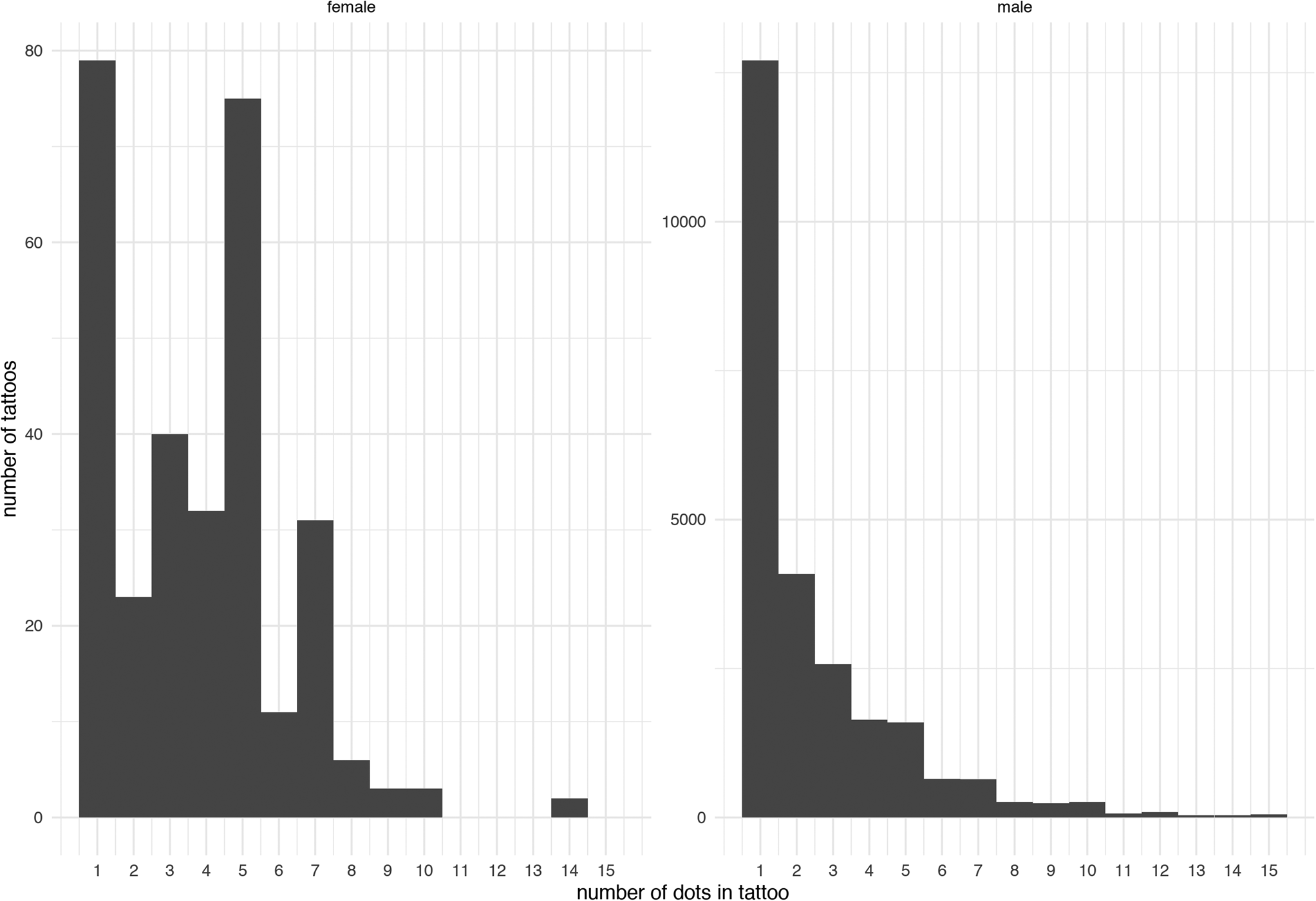

Because transported convicts often acquired their tattoos on the voyage to Australia, it seems unlikely that they represented the affiliation with the imprisoned thieves described by the Millbank prison warder. Moreover, while there were far more men than women with five or seven dots, women, who were not generally thought to be part of these gangs, were proportionally far more likely to choose these patterns. Indeed, a five-dot pattern or design does not stand out as a distinctive form of tattoo for men (figure 8).

Figure 8 Number of dots in tattoo descriptions, women versus men.

An examination of the wide range of other tattoos collocated with five-dot and seven-dot tattoos demonstrates that they were rarely aligned with expressions of criminality or defiance—as was a skull and crossbones—and instead were often used for decorative purposes or to express other meanings. While all the collocation correlations of dot tattoos with other designs are weak, indicating that no single specific tattoo design was frequently present on convicts with five- and seven-dot tattoos, the most commonly collocated design for five dots was a stroke, indicating a more complex design that we cannot identify, and rings. The latter, also collocated with seven dots, were found on both male and female convicts. Augustine O'Leary, convicted of simple larceny in 1902, had “numerous” dots on his left forearm and both hands, including five dots at the base of his left thumb and rings on his first and second left fingers and his first right finger.Footnote 51 For some, dot tattoos were a form of jewelry that was cheap and easy to administer. They could also represent love: Elizabeth Morgan's recorded marks in the transportation records, which include a simple sketch of her five-dot tattoo next to the initials of Joseph Bayless, suggest that she used it as part of an expression of love.Footnote 52 Other collocations for the seven-dot tattoo included the sun, moon, and stars, which likely means that dots were used to represent constellations such as the seven-star Pleiades cluster, a maritime reference similar to those found in the tattoos of transported convicts.

References to death can be found in 5.8 percent of all tattoo descriptions, and as figure 5 indicates, these increased somewhat as a proportion of all tattoos over time, reaching 6.7 percent of the tattoos recorded in the Register of Habitual Criminals between 1881 and 1925. These tattoos might also be considered evidence of the deviant dispositions of the tattooed, but the evidence suggests otherwise. The most common subject collocations with death, in decreasing frequency, were national identity, nature, love, and religion. A wreath, the most common design that may have referenced death, was most commonly collocated with designs such as crown, female, ship, and star, suggesting that wreaths rarely referenced death at all.Footnote 53 There were 1,778 convicts tattooed with tombstones (frequently collocated with mother and memory, as in “in memory of my dear mother”), and 132 with skulls, including 112 in various forms of skull and crossbones, which were sometimes collocated with a cross or crucifixion.Footnote 54 Potentially more darkly, sixty-six convicts had tattoos simply referencing “death” (it is not clear whether this was a written word or a symbol), including the written expressions “death and glory” (10), “death or glory” (7), and “death's head” (3). James Smith, convicted of robbery in York in 1828 and transported to Tasmania, had “Deaths head & bloody bones H.O.A.A. F.H.G.I.T” and “a hand with a Dagger in it,” both tattooed on his left arm.Footnote 55 Because we do not know what the initials stood for, it is impossible to fully make sense of these tattoos, but the menace expressed is palpable. As with the dot tattoos, however, the collocations for tattoos relating to death often subvert any sense of menace and suggest that the bearer wished to express a wide range of sentiments. Thomas Prescott's tattoo of a “Man with dagger and Pistol in [his] hands” on his breast, for example, was juxtaposed with tattoos expressing love and family allegiance.Footnote 56

Some tattoos may have expressed subversive sentiments concerning the judicial system. Arguing that the tattooed body was “a commentary on the world of convict experience,” Maxwell-Stewart and Bradley noted that the tattoos on some transported convicts “seem[ed] to poke fun at the coercive powers of the state,” with one convict having a tattoo of a broad arrow (typically used on prison uniforms), possibly commenting that he had become “government property.”Footnote 57 A small proportion of tattoo descriptions (0.3 percent) included references to justice and punishment, including men in fetters, figures hanging from the gallows, whips, and even policemen, but it is difficult to identify their intended significance (though the whips were often collocated with references to horses, indicating a very different meaning). Once again, the collocations indicate that such designs were often worn along with more positive sentiments. In addition to a tattoo of a “man hanging on a gallows,” placed, unusually, on his right foot, in 1890 William Smith had the more conventional tattoos of an anchor, twelve flags, three sails, two cannons, three rings, and the initials T. S. W. B. on his arms and hands.Footnote 58

Perhaps the most defiant tattoos involved the rejection of conventional sexual morality (evident in the prison warder's comments about “naked men and women”), but these were rare. The complicated collection of tattoos found on the body of Horace George Hougham, convicted of an unknown offence for the fourth time in 1889, included the words “CUNT” on his right leg and “FOCK ME QWICK YOU SODE PLLIK SA-EEY DEAR” on his left leg; perhaps significantly, these tattoos were on probably covered parts of his body.Footnote 59 More openly, Francis Holt, convicted in Hull of housebreaking in 1912, had a “woman lying on sofa” and “LET ’EM ALL COME” on his forearm.Footnote 60 In other cases, naked men and women, sometimes described as “indecent,” can be found, almost exclusively on male convicts, frequently located on visible parts of the body such as the forearm. Images of men and women together in an “indecent position,” however, were located on the thigh.Footnote 61 But these were rare. This evidence complements Vic Gammon's research on popular songs of the time, in which he found little celebration of sexual license.Footnote 62

There is only limited evidence, therefore, to support the claims of late nineteenth-century social observers and criminologists that tattoos were expressions of criminal allegiance or evidence of a criminal character. More commonly, as these last examples suggest, tattoos express an appreciation of pleasurable activities. In addition to sex, alcohol, smoking, dancing, cards, and pugilism were the subjects of a wide range of tattoos, found in 2 percent of descriptions. Smoking and drinking were most commonly celebrated, with designs of tobacco pipes and boxes, glasses, bottles, and barrels. There were also tattoos of fiddles and men and women dancing. An image of a sailor with a fiddle, sometimes standing on a barrel marked RUM, is recorded on six convicts between 1888 and 1897.Footnote 63

References to cards and gambling can also be found, with tattoos of dice, clubs, diamonds, hearts, and spades, and “three cards” (probably referring to brag, an antecedent of poker).Footnote 64 The popular nineteenth-century sport of pugilism was celebrated with depictions of men fighting. William Lindsay arrived in Australia in 1854 with a full boxing match decorating his chest.Footnote 65 Evincing the same interest in celebrity as found in the Buffalo Bill tattoos, the famous 106-round bare-knuckle boxing match between Jem Smith and Jake Kilrain in Paris in 1887 was commemorated in tattoos on eleven convicts, often placed next to wreaths, perhaps as an indication of the prizefighters’ fame.Footnote 66

While many of the most elaborate tattoos depicting pleasurable activities were documented on men and women at the end of the nineteenth century, the heatmap in figure 5 shows that the subject of pleasure was present throughout the century, and was actually proportionally more common in the early decades. The confident, celebratory qualities of these designs were integral to the practices of tattooing, as can also be seen when we examine the locations of tattoos on the convict body.

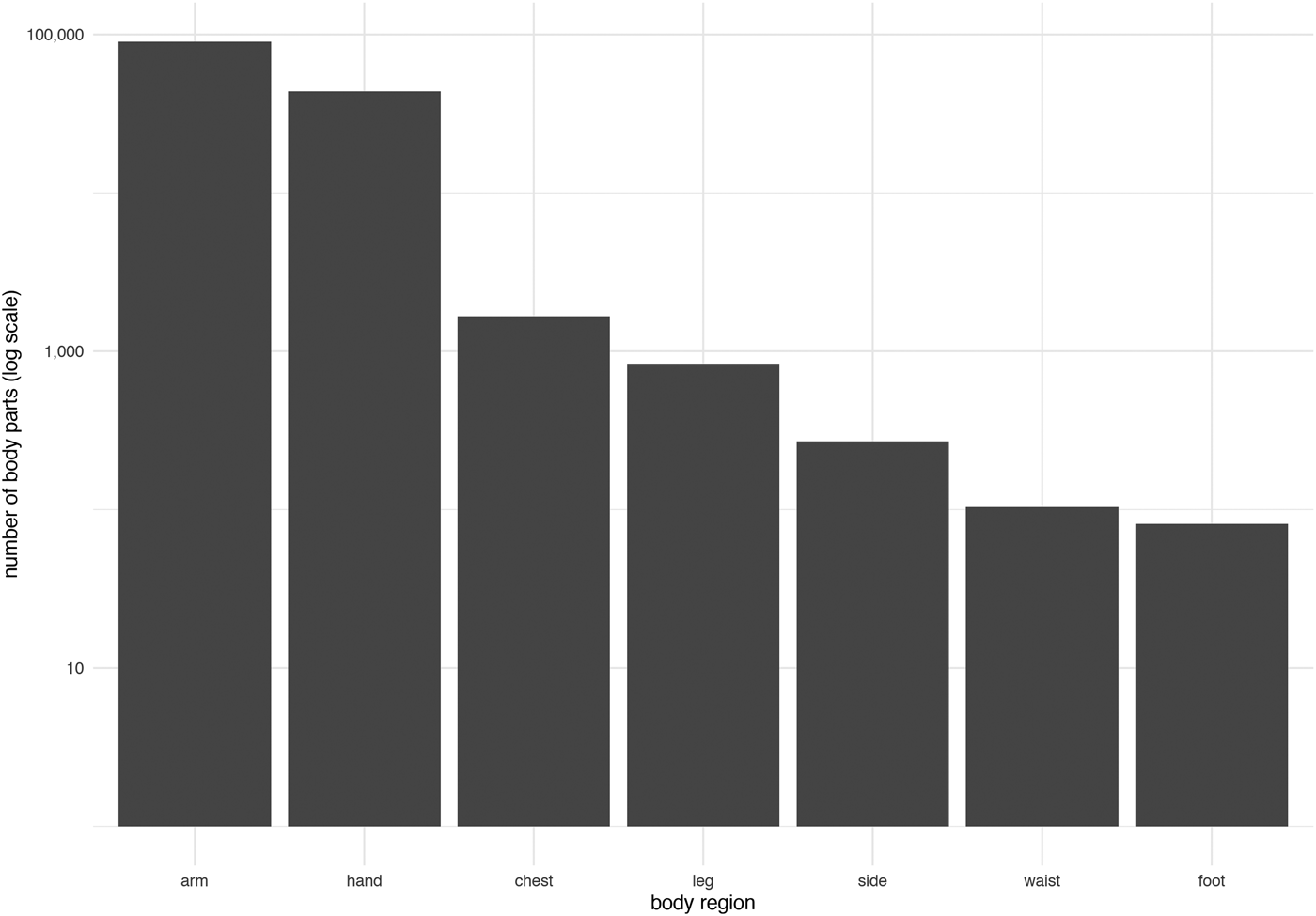

Most tattoos were worn on visible parts of the body (those not routinely concealed by clothing), suggesting that there was little stigma around wearing tattoos, in spite of the views of some social observers. Arms and hands were by far the most common locations, accounting for 96.45 percent of all identified body parts, so figure 9 presents the data on a logarithmic scale. This evidence indicates that these marks were confidently worn with the intention of being seen. Relatively few convicts wore tattoos on their legs, hips, thighs, or feet, as tattoos were normally displayed on more visible parts of the upper body. This may be to some extent an artifact of record-keeping practice—we do not know how often convicts, particularly women, were fully naked when they were examined, as opposed to being only stripped to the waist.Footnote 68 Yet isolated examples indicate that some convicts, including women, were fully examined.Footnote 69 These include Bridget Cassidy, who wore the mark of a tobacco leaf on her right thigh,Footnote 70 and James McDermott, who wore a number of tattoos on his legs and feet, including a “shield [on his] right instep, anchor on calf, garter right leg, snake left foot, star on his calf.”Footnote 71 William Cotterell wore a rose on each hip,Footnote 72 but very few convicts had tattoos on intimate parts of the body such as the groin. No convicts in the dataset were recorded as having tattoos on their buttocks, but William De Bank's large number of tattoos across his body included the initials P.R.M.C.A on his right groin and E.D. on his penis.Footnote 73

Figure 9 Numbers of tattoos on different parts of the body (logarithmic scale).Footnote 67

Despite the limitations of the evidence for surveying the use of the lower body, the frequent overt placement of tattoos on parts of the body that were highly visible and not (or not consistently) obscured by clothing demonstrates the broad acceptability of tattooing in the nineteenth century. It points to a shared fashion of wearing public-facing tattoos to express the bearers’ interests, emotions, and identities.

Tattooing in Victorian Society

The diverse range of designs and subjects found in convict tattoos suggests that they were very much embedded in the wider culture of nineteenth-century Britain, while the exposed location of most tattoos suggests that there was not much stigma associated with having them. But what evidence is there that tattooing was commonly practiced outside the confines of the transportation ship and the prison? Without the systematic evidence found in convict records, our arguments must depend on inference and anecdotal references, and so remain tentative pending further research. But such evidence, combined with the findings from the convict database, strongly suggests that the practice of body marking took place in many sections of English society in the nineteenth century and even earlier.Footnote 74

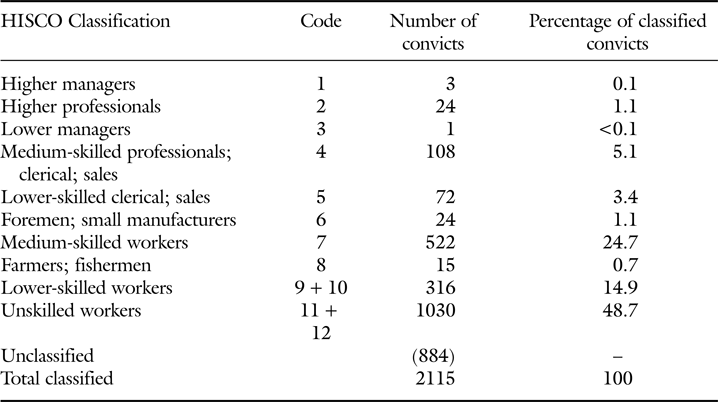

While transported convicts often acquired their tattoos on board ship, it is unlikely that much tattooing took place within British prisons. It was prohibited in the highly regimented reformed prisons of the nineteenth century (which frequently involved solitary confinement)—although of course some convicts were able to evade the rules.Footnote 75 In any case, the complexity and sophistication of many tattoos, such as those of Buffalo Bill or the Japanese woman, suggest that tattooing could not have been carried out while attempting to hide from prison officers. With the possible exception of the Registers of Habitual Criminals, convicts’ physical appearances were commonly documented on entry to prison and not upon release, so the tattooing had taken place before convicts were incarcerated, and in this context their wide range of occupations suggests that it took place in many parts of society. Occupations are recorded for only 4.8 percent of tattooed convicts from across the period, but the sheer breadth of economic activities of tattooed convicts is impressive, from higher skilled occupations such as engineers (20), to skilled non-manual occupations such as dealers (49) and clerks (60), skilled manual occupations such as tailors (128) and shoemakers (127), and lower-skilled occupations including carmen (43), postmen (47), and painters (80). The most common occupation, laborer (882), likely involved a wide range of activities.Footnote 76 In table 2, using the internationally agreed-upon system of historical occupational classifications (HISCO), we show that while just under half of the occupations were “unskilled,” another 40.3 percent were “lower” or “medium” skilled manual or nonmanual workers (codes 7–10), and 9.6 percent were categorized as “lower” managers: professionals, clerical and sales personnel, and foremen and small manufacturers (codes 3–6).Footnote 77 While only a minority of these occupations might be deemed middle class, the broad range of working-class occupations among tattooed convicts demonstrates that nineteenth-century tattooing was not a niche activity. It also supports the consensus of historians that the idea of the existence of a “criminal class” was “based on largely fallacious information” and that “no clear distinction can be made between a dishonest criminal class and a poor but honest working class.”Footnote 78

Table 2 Occupational classifications of tattooed convicts.

Public awareness of tattooing spread in several ways. Sailors returning from voyages to the Americas, Asia, and Europe brought knowledge of practices from other cultures, and in 1774 when Captain Cook “brought back a ‘guest’ named Omai (or Mai) from Tahiti, who displayed his tattoos at court (and was painted by Joshua Reynolds, among others),” tattooing came “to the forefront of the broader public's attention in Britain.”Footnote 79 By the mid-nineteenth century, the association between sailors and tattooing was pervasive in British society. In an Old Bailey case from 1863, a police inspector testified, “I have seen many sailors mark their arms, and some policemen.”Footnote 80 A witness in the trial of Charles Anderson for the murder of James Marchien in 1867 described sailors tattooing each other on the merchant ship Raby Castle.Footnote 81 In 1896, the London-based tattoo artist George Burchett described his clientele as “sailors, dockers, and other rough diamonds,” and fellow tattooist D. W. Purdy remarked that tattoos were “a common thing among soldiers and sailors.”Footnote 82 By 1890, professional tattooing had become a common feature in international seafaring ports.Footnote 83

Tattooing was also a recognized practice in working-class youth culture. Henry Mayhew observed tattooing among costermongers in mid-century London, noting their “delight in tattooing their chests and arms with anchors, and figures of different kinds. During the whole of this painful operation, the boy will not flinch, but laugh and joke with his admiring companions, as if perfectly at ease.”Footnote 84 While tattooing among boys of the working and artisan classes was well known, there is evidence that it also occurred, perhaps more surprisingly, among elite schoolboys.Footnote 85 Roger Tichborne, heir to the Tichborne baronetcy, wore a number of tattoos by the time he was sixteen years old, notably a cross, heart, and his initials, R.C.T., and he tattooed his schoolfellow Lord Bellew's arm in 1848.Footnote 86 Tattoo artist George Burchett recalled that he learned tattooing “at a young age” in the 1880s, “observing tattooed performers and working tattoo artists at the eclectic London Aquarium, and tattooing his schoolmates.”Footnote 87

Tattooed freaks (in the sense of persons transformed by an extraordinary medical condition or body modification) on display in circuses, fairs, and traveling shows became popular attractions in the nineteenth century and drew broad and diverse audiences on their national tours. Such shows, widely publicized through classified advertisements in the popular press, often included “at least one heavily tattooed person, often a woman,” and were commonly framed through imperial narratives of the exotic other.Footnote 88 Capitalizing on the popularity of “tattooed savages,” these forms of popular entertainment ensured the exposure of tattoos to large audiences and contributed to the development of tattooing as a mainstream practice. According to O'Neill, “many of these pleasure palaces blurred the distinction between spectators and spectacle by the participatory nature of their offerings.”Footnote 89 As souvenirs of their visit, visitors could get themselves tattooed. Alfred Smith, a professional tattoo artist at the Royal Aquarium, a pleasure palace in Westminster in the 1890s that included “tattooed savages,” claimed to have tattooed “five or six thousand people” over four years.Footnote 90

The media contributed to the growing awareness of tattoos as an acceptable practice, particularly with the highly publicized court case of the Tichborne Claimant, which preoccupied the national press in the early 1870s. An imposter variously referred to as Thomas Castro or Arthur Orton claimed to be Roger Tichborne, the missing heir to the Tichborne baronetcy, but his claim collapsed in 1872 when it was revealed that Castro/Orton (as our records confirm) did not possess the tattoos (discussed above) that Tichborne was known to have. The widespread publicity of this case ensured exposure of tattooing to a broad spectrum of British society, but it also revealed that tattooing was not confined to the margins of society. Notably, Tichborne's tattoos were viewed as unremarkable, except by one member of his own family, who professed shock that he wore tattoos that “reeked of low life,” “like a common soldier.” But such responses were unusual. When the defense lawyer Kenealy labeled Bellew and Tichborne as immoral, he did not refer to their tattoos as evidence but rather to their sexual impropriety.Footnote 91 Indeed, there was little commentary on Tichborne's tattoos except with respect to the validity of the claim that he had possessed them. In this case, the significance of tattoos lay not in their unacceptability but in their role in establishing identity, a departure from previous perceptions of tattoos as a peripheral part of British culture.Footnote 92

The tattoo also became a key theme in British literature, as it became a staple of the new crime fiction of the 1880s and 1890s. Tattoos featured in texts such as H. Rider Haggard's Mr Meeson's Will (1888) and Thomas Hardy's A Laodicean (1881), which explored what marks did and did not reveal about identity.Footnote 93 While tattoos continued to hold negative associations, their strongest significance, according to Gilbert, was in “establishing identity, whether the identity of a drowned sailor, a criminal, or an heir.”Footnote 94 The spreading cultural awareness of tattoos in mainstream society incorporated both positive and negative associations, but the depictions of tattoos in the press, literature, and popular culture indicate that they were firmly embedded in the public consciousness by the later decades of the nineteenth century and were widely understood as a means of expressing identity.

These developments culminated in the elite tattooing craze of the 1880s. Tattooing enjoyed a surge in popularity among the British upper classes after it became known that various members of the nobility and royalty, including Edward, Prince of Wales, and his sons Albert Victor and George, had acquired tattoos on journeys to Jerusalem and Japan.Footnote 95 Tattoo artists were lionized in society journals and catered to wealthy clientele in lavish Oriental-style studios, implying that this “anomalous metropolitan ‘craze’ [was] shaped by this specific set of colonial encounters.”Footnote 96 Unlike the men who dominated the working-class tattooed, it was women who were particularly attracted to the latest elite fashion for body art. Woman's Life magazine observed in 1898 that, “hundreds of British ladies were being tattooed everyday.”Footnote 97 The high-end journals Tatler and Vanity Fair advertised a range of new tattoo motifs to women, often relating to leisured pastimes, which indicated “the hyper-modernity of the female body.”Footnote 98 But elite tattooed women attracted diverse responses. Some observers viewed the practice as modern, but others viewed it as emblematic of British decline, especially aristocratic decline.Footnote 99 Negative associations around tattoos persisted, but wider evidence placed alongside the systematic study of convict records suggests that tattooing had become a popular practice shared by a broad spectrum of society in late Victorian Britain.

The growing popularity of tattoos was facilitated by the development of professional tattooists who set up shops in London, and by the invention of an electric tattooing machine in 1891, by an American, Samuel O'Reilly. The first confirmed tattooing parlor in England opened in the Hamman Turkish Baths, in Jermyn Street in London's fashionable West End district of Soho in 1889. When interviewed for a piece that year in the Pall Mall Gazette, the proprietor, Sutherland McDonald, described his customers as being “mostly officers in the army, but civilians too. I have tattooed many noblemen, and several ladies.”Footnote 100 Other tattoo artists identified an increasing spread of tattooing across the British social spectrum. Pat Brooklyn, a “society tattoo artist,” reflected in English Illustrated Magazine (1903) that “at the present day tattooing is steadily growing in favour with all classes of the community . . . many royalties and prominent members of Society of both sexes now carry on their bodies pictures and designs which are real works of art, and which have taken hours, and in some cases days, to ‘paint.’”Footnote 101 By the close of the nineteenth century, tattooing was so widely known that tattoo artist “Professor” D. W. Purdy, whose shop in Holloway was in a less prosperous part of London, published a cheap handbook in 1896, Tattooing: How to Tattoo, What to Use, & How to Use Them. Despite its title, the book strongly discouraged self-tattooing, but it confirmed that the widespread interest in tattooing had expanded beyond the usual clientele.Footnote 102 A letter to the Pall Mall Gazette in 1889 claimed that “in England . . . among the middle and upper classes, tattooing is practiced to an extent it was certainly not twenty years ago.”Footnote 103 While the evidence of middle-class tattooing, outside naval and military officers, is limited, tattooing had clearly permeated many parts of British society at the end of the century.

Conclusion

For those whose bodies were marked, tattooing had its disadvantages: as a sign of identity, it could be used to identify those accused of crime who had been previously convicted.Footnote 104 And yet a large number of convicts and others wore tattoos, most frequently on public parts of their bodies, to express their emotions, affinities, and interests. The association between tattoos and criminality emerged from European criminologists and social investigators who claimed that tattoos were part of a criminal argot, a discrete code shared among the notorious criminal classes.Footnote 105 But, as we have highlighted, despite that ongoing stigma, the emergence of a broader acceptability and wider cultural significance of tattooing extended across the social spectrum in Victorian Britain. Our evidence indicates both an increase in the percentage of convicts who were tattooed over the nineteenth century and the adoption of a broader range of subject designs and cultural themes, indicating that tattooing became an increasingly widespread practice.

Rejecting any attempt to characterize them by their criminality, convicts inscribed their bodies in much the same way as people do today—commemorating their lovers and family and the pleasures of everyday life, and exhibiting a wide range of positive emotions and sentiments, on parts of their bodies often publicly exposed. Convict tattooing was an expressive activity, rarely specifically linked to crimes and punishments. In their images of vice and pleasure, some convicts may have signaled an alternative morality, but for most, tattoos simply reflected their personal identities and affinities, their loves and interests. As tattooing became more popular and proficient, it became more inventive and creative, reflecting wider cultural trends and fashions. Tattooing was a multidimensional practice, expressive of many positive as well as some negative meanings.

The occupations of the convicts within our dataset demonstrate that tattooing was not confined to a distinct criminal class. Many tattooed convicts were highly skilled, nonmanual workers as well as low-skilled manual laborers. Tattooed convicts were ordinary working Londoners whose lives were punctured rather than defined by their interactions with the criminal justice system. Literary and other anecdotal evidence demonstrates that tattooing permeated many other parts of British society in the nineteenth century, as awareness of tattooing spread through popular entertainment and print culture. The late Victorian elite tattoo craze, no doubt unintentionally building on practices developed in popular culture and facilitated by the development of commercial tattooing, signaled that tattooing was no longer a marginal activity but a popular, even fashionable practice in many sections of British society.

Though further research is necessary, it is evident that tattooing lost some of its popularity in the early twentieth century. As a result of increasing concerns about hygiene, renewed associations with criminality, and an affiliation with soldiers and sailors during World War I, it became a marginal, though still significant, activity. Tattooing began to regain popularity from the 1950s, initially among subcultures that included gang members, bikers, and punks and rockers, as a symbol of both group allegiance and defiance of conventional society. But, as in the nineteenth century, in the late twentieth century the fashion then spread much more widely, taking on new meanings.Footnote 106 Ultimately tattooing is a fascinating but poorly recorded practice that, like other forms of bodily display, was and is subject to fashion and to multiple interpretations and meanings. Despite the attempts to stigmatize the tattoo, it has a tendency to incorporate mainstream culture and become part of it.