In 1938, Mrs. E. B. Ntsonkota of East London, South Africa, appeared in a testimonial advertisement for Ambrosia Tea in the bilingual Xhosa-English newspaper Umlindi we Nyanga (The Monthly Watchman). The advertisement occupied half a page, and featured a full-length photograph of Mrs. Ntsonkota. ‘One cannot help being a loyal user of Ambrosia Tea’, she was quoted as saying; ‘As a Headman's wife I have introduced its use to a lot of friends’.Footnote 1 Mrs. Ntsonkota's testimonial was part of an advertising campaign that highlighted African women customers through write-in competitions and testimonials.Footnote 2 In all, Ambrosia published the names and addresses of 36 different women between 1938 and early 1941, when Umlindi closed because of wartime shortages. Six women's photographs appeared in eighteen of these advertisements, and a few of the testimonials included lengthy statements by the writers. These advertisements offer an opportunity to examine the making of a literate, aspiring middle-class feminine African consumer culture in early twentieth century South Africa.

The Ambrosia campaign shows how a white-owned business worked to build an African market in South Africa's rural eastern Cape region during the 1930s, a time when both consumer goods and consumer culture were changing. The owners of Ambrosia and the editor of Umlindi we Nyanga used the format of the testimonial to portray rural, literate, African women as ideal consumers. In doing this, the advertiser, newspaper editor, and testimonial writers all tapped into local meanings of tea consumption and ongoing debates about modernity, femininity, and respectability. Ambrosia tried to attract customers by cultivating a participatory, feminine reading public centered on the consumption of goods that were ‘wise’ and ‘intelligent’. At the same time, two Ambrosia spokeswomen used the format of the testimonial to promote their newly founded home improvement societies, and to offer their own analysis of rural women's duties as leaders of the home and of the nation.

Historians have effectively dismantled the image of African consumers as naïve buyers of ‘trinkets’ or ‘truck’, either during the era of the slave trade or in the era of mass-produced consumer goods.Footnote 3 Scholars have been particularly interested in consumers’ creativity in the realm of clothing and fashion. By ‘dressing up’, people changed the meanings of garments and challenged social hierarchies.Footnote 4 Even products less pliable than fabric, and with an apparently fixed branded meaning, have been used by buyers for various purposes.Footnote 5 New histories of consumer culture in Africa are thus attentive to the social context of consumption; that is, the relationships within which consumer desires and choices are embedded.Footnote 6

Therefore, histories of consumption in Africa must attend not only to what people bought in stores and how they used those items, but also to the media in which those goods were marketed, because local tastes also influenced advertising.Footnote 7 Histories of marketing in Africa have examined corporations’ attempts to get ‘inside the skin’ of the Black consumer in the 1950s and later.Footnote 8 Ambrosia's advertising campaign in Umlindi we Nyanga shows how, as early as the 1930s, a white-owned company crafted a successful marketing campaign based on their perception of the existence of a rural, educated, literate, feminine African customer market.

In South Africa, the extensive archive of the Black press has sustained a long scholarly discussion of power, representation, and race. In the nineteenth century African intellectuals founded independent newspapers in indigenous languages, but by the 1930s most had been bought out by white business interests, which saw the newspapers as a way to grow the Black consumer market.Footnote 9 For a long time, scholarly discussion of this ‘captive black commercial press’ centered on its political content, and the extent to which white-owned newspapers could be vehicles of resistance.Footnote 10 More recent scholarship on newspapers in colonial and postcolonial Africa emphasizes the creative, participatory relationship between readers and writers.Footnote 11 The South African vein of this scholarship has demonstrated that newspapers hosted complex cultural and political debates among Black readers.Footnote 12 This understanding of newspaper culture depends, as Natasha Erlank has argued, on reading the ‘form’ of the newspaper, attending to the relationship between all parts of the newspaper and not only the political columns.Footnote 13 In the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Black press, advertisements were not completely distinct from editorial or news content.Footnote 14 One scholar argues that Bantu World's advertisements ‘activated the dual construction of readers and consumers’.Footnote 15 Lynn Thomas's work on Bantu World shows how men and women in the 1930s debated standards of beauty, the use of advertised cosmetics, and their relationship to racial respectability.Footnote 16 Readers of the Black commercial press were participants in complex discussions of the moral and financial values of the products advertised to them.

The growth of the Black commercial press in 1930s South Africa coincided with the emergence of home improvement societies in colonial states across Africa. These organizations, usually initiated by the wives of colonial administrators, were often inspired by African American programs of rural industrial education such as the Jeanes movement, which employed Black women educators to teach practical skills in rural Southern communities.Footnote 17 In colonial Africa, such home improvement and domestic education clubs offered an appealing but ultimately limited venue for African women to pursue modernity and economic competence within the racial and gender hierarchies of the colonial state.Footnote 18 Studies of these home improvement societies have noted the material objects that ‘civilized’ or évolué (the term in francophone colonies for those who adopted colonial culture, dress, and education) women were expected to own, but aside from Timothy Burke's pioneering research on marketing in colonial Zimbabwe, this literature has not examined how African women learned about and bought the products they were expected to own.Footnote 19 In South Africa, the intersection between the home improvement movement and the growth of newspaper advertising targeted at educated, aspiring middle-class Black women needs more exploration. This intersection is particularly intriguing in the case of the eastern Cape because home improvement societies here were founded independently by African women rather than by missionaries or officials. The Ambrosia Tea campaign in Umlindi we Nyanga presents an opportunity to see how the home improvement movement engaged with the consumer products being sold to them as leaders of the home.

Selling tea in 1930s South Africa: testimonial advertising and rural female consumers

The Ambrosia Tea campaign in Umlindi we Nyanga in the late 1930s must be seen in the context of the growth of the Black consumer market — or, rather, white businesses’ perception of such growth. Umlindi we Nyanga was a commercial newspaper. It was created by Baker, King Limited of East London as a way to market its products to a rural — mainly Xhosa-speaking — audience in the ‘native reserves’ of the Ciskei and Transkei (which constituted much of the present-day Eastern Cape province). Baker, King began as wholesale exporters of wool from the eastern Cape's white-owned sheep farms. In the early twentieth century the company acquired several East London factories in an attempt to become the domestic supplier of consumer items for the African market, which had previously been imported from Britain.Footnote 20 By 1936 the company owned Saftex Limited (blankets), Fomex Limited (various candle and soap brands), Howe Limited (a printing press), Packers Limited (tea and coffee sold under the Ambrosia brand), and Kowie Medicines (medicines and home remedies). All these goods underpinned Baker, King's ‘very large trade in the Native Territories, in which field it has maintained a leading position for many years’.Footnote 21 Umlindi we Nyanga was founded in 1934 to promote Kowie Medicines, but soon began to carry advertisements for other Baker, King products, and also ran advertisements from other local and national brands.

Like other commercial newspapers for Black readers, Umlindi was owned by ‘white liberal business interests’ who wanted to take advantage of Black purchasing power to sell their products.Footnote 22 Other newspapers with a similar mission were Bantu World and Inkokeli ya Bantu. The purpose of these papers was neatly summed up in Inkokeli's inaugural edition, which boasted its advertising potential:

Many articles produced and manufactured in South Africa have become, with the advance of civilisation, ‘Essentials and Necessities’ to the Bantu People. These Products go begging for lack of … correct methods how best to bring to the notice of the Bantu the value of these Products.Footnote 23

These sentiments were echoed by other white investors and newspaper owners. Their hopes for profit were so sanguine precisely because they did not have detailed evidence to support their ambitions. Across South Africa, increasing numbers of Africans were taking waged work in the migrant labor economy, and yet their cash incomes were inadequate for household subsistence. In the eastern Cape, for example, incomes of migrant workers stagnated or declined during the Depression.Footnote 24 Reports by the white liberal members of the South African Institute of Race Relations (SAIRR) reveal contradictory interpretations of this evidence. According to one 1938 report of the SAIRR, real wages for ‘non-Europeans’ declined between 1924 and 1934.Footnote 25 However, a report on cooperative business ventures from the same year claimed that the African population ‘undoubtedly represents an unsatisfied market capable of enormous expansion in every direction’.Footnote 26 Both business and government observers perceived African households to have new supplies of disposable cash, and were therefore concerned with the goods these consumers were buying.Footnote 27

Like Bantu World and other commercial newspapers of the era, Umlindi's news coverage reflected moderate African nationalist views, and its tone and content were often didactic. R. H. Godlo, an established East London politician, was hired as its editor when the paper began in 1934.Footnote 28 Godlo was a member of the All-African Convention (AAC), a moderate political organization in the Cape liberal tradition.Footnote 29 He was an officer of the Independent Order of True Templars, a temperance organization, and served on East London's Native Advisory Board.Footnote 30 Umlindi's news coverage closely matched Godlo's political commitments. Temperance, for example, was a frequent editorial topic. Godlo was an ideal editor for the paper from Baker, King's perspective. He was well connected to political and church leaders across the eastern Cape, and his moderate political views might be expected to resonate with African readers without alarming authorities.

The appeal of Godlo's editorship would provide a vehicle for advertising Baker, King's products. In the 60 issues between January 1936 and January 1941, Umlindi printed 956 advertisements.Footnote 31 On average, each issue of five to six pages contained sixteen advertisements. The advertisements were mainly for small consumer products like patent medicines, tea, cigarettes, blankets, and cookware. There were also advertisements for more expensive items like bicycles and clocks. Tea was the most frequently advertised product, with 135 advertisements appearing from specific brands and the Tea Market Expansion Bureau.

The fact that tea was the most frequently advertised product in Umlindi we Nyanga was not a coincidence. In the early twentieth century, the Tea Market Expansion Bureau— a British and Dutch consortium of tea growers and distributors — established branches in over a dozen cities around the world in order to promote tea drinking on a global scale. Tea's transformation from a local crop into a global commodity occurred within British imperial networks. Indeed, early twentieth century advocates of empire saw tea as the commodity that would bind the empire together. Women as consumers were central to this project; in the 1920s, for instance, newly-enfranchised women in Britain were encouraged to buy tea as a patriotic duty.Footnote 32 When the Depression caused a slump in the global tea market, tea growers and marketers turned to a new global constituency of colonial subjects to sustain demand for their product.Footnote 33 During the 1930s, the Tea Market Expansion Bureau opened an office in Durban, and launched a vigorous marketing campaign which included advertising in the Black press, sending lecturers to give presentations to schoolchildren, and using mobile cinema vans to show promotional films to rural audiences.Footnote 34

In Umlindi we Nyanga, the bureau's promotional work took the form of comic strips featuring ‘Mr. and Mrs. Mseliweti’ and their children, who proclaimed the benefits of drinking tea. The bureau placed 57 advertisements in Umlindi over four years, making it the fourth most frequent advertiser in the paper. The bureau's general promotion of tea drinking was likely an encouragement to Ambrosia Tea to expand its own branded advertising. If the bureau's propaganda convinced people that they should buy tea, all Ambrosia had to do was tell them which type to choose. In this way, changes in the global market affected which products were advertised and available in the eastern Cape region of South Africa.

In June 1936, Baker, King began to advertise some of its products in Umlindi using the newly popular style of testimonial advertisements. In the 1920s American advertising agencies had begun to use testimonials from both celebrity and ‘ordinary’ consumers more frequently. Other advertisers around the world made similar choices.Footnote 35 Possibly the earliest testimonial-style advertisement in a Black South African newspaper was in Bantu World in 1932, when the Township of Clermont in Durban advertised its plots for sale with a reproduction of the title deed of Mr. Solomon Sibisi, a satisfied new plot owner.Footnote 36 The first testimonial-style advertisement that Umlindi printed was in October 1936 for I-Femix, a women's health product made by Kowie Medicines. The text of the advertisement described the powers of the medicine below a picture of a woman captioned ‘U-Mrs. T.N. waku Cofimvaba’.Footnote 37 The implication of the photograph was that Mrs. T. N. from Cofimvaba was a satisfied user of I-Femix.Footnote 38

In 1938 Umlindi began to print testimonial advertisements much more frequently and intensively to advertise Ambrosia Tea. The first testimonial advertisement for Ambrosia featured Mrs. Ntsonkota, the ‘Headman's wife’ from near East London.Footnote 39 In all, Ambrosia featured the names and addresses of 36 different women in its advertisements between 1938 and 1940. Six women's photographs appeared in eighteen of these advertisements. The other thirty names and addresses were printed without photographs or testimonial statements, some of them as part of a list of prizewinners.

Ambrosia's advertisements framed ‘wisdom’, ‘education’, and ‘intelligence’, as the key characteristics of its consumers. While Wingate Tea advertisements expounded on taste and quality, and the Tea Market Expansion Bureau comics portrayed tea as conveying energy and family harmony, Ambrosia advertisements were most concerned to associate their product with ‘wise mothers’: respectable, educated, socially prominent married women whom other consumers should want to emulate.Footnote 40 One of the first Ambrosia advertisement stated that ‘All wise mothers know Ambrosia is famous for value and quality’.Footnote 41 In an advertisement featuring a photograph of a group of male and female teachers, the text read: ‘You may be quite sure when you study such a photograph that nearly all of them are users of Ambrosia Tea because intelligent and well educated people know that Ambrosia Tea is made from the very best leaves’.Footnote 42 Another advertisement told readers to ‘Ask for the favourite tea of all Wise Africans’, above a list of names and addresses of women who had won a competition.Footnote 43

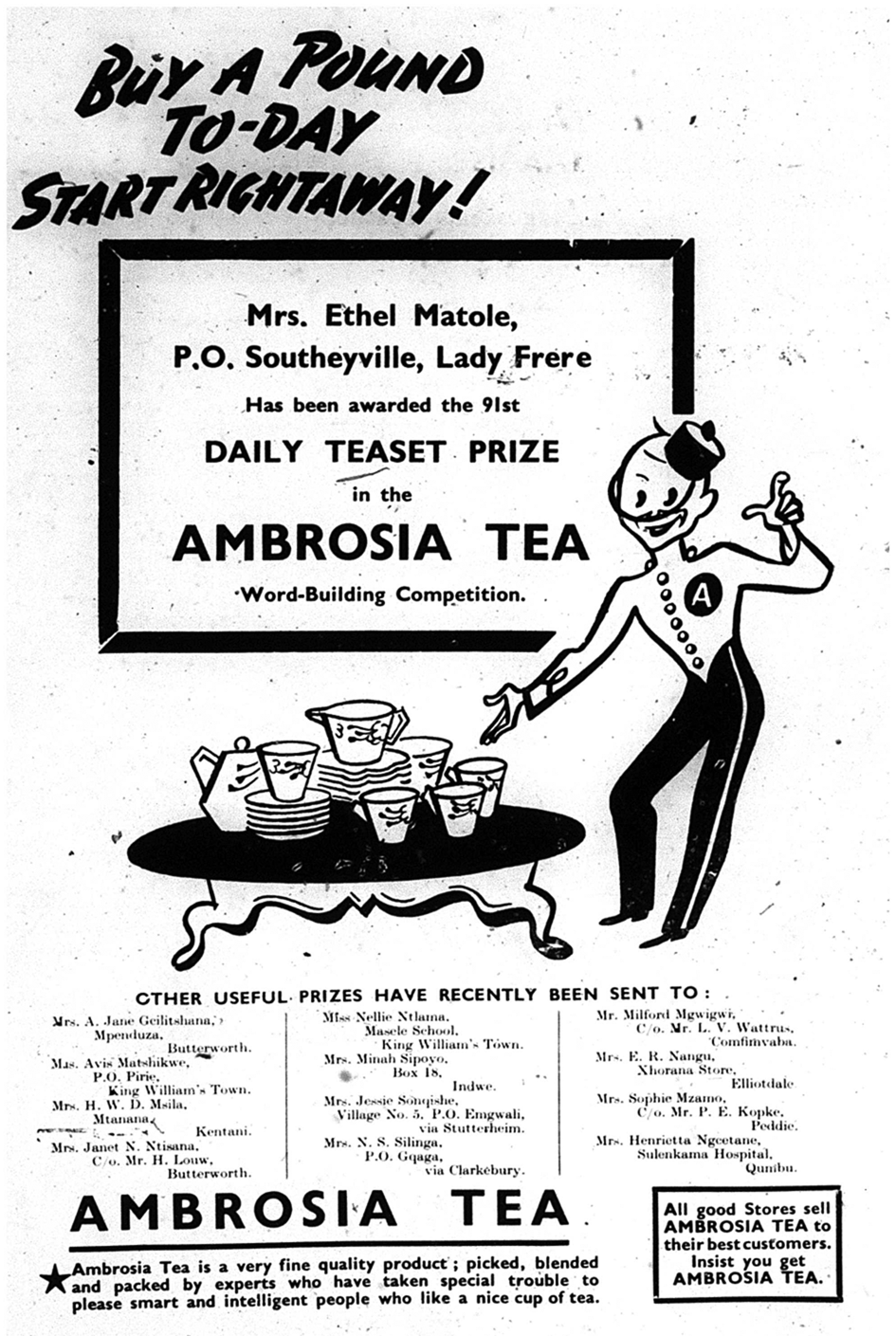

That this competition was a ‘word-building competition’ underscores the importance of intelligence and education in Ambrosia's marketing. The exact nature of the word-building competition is not clear from the advertisements themselves. An early Ambrosia advertisement instructed buyers to ‘keep the tickets’ enclosed in its packages, so possibly the puzzle and instructions were included inside boxes of tea.Footnote 44 This word-building competition was at its height in 1937 and 1938. When Mrs. Ntsonkota won her tea set in 1937, Umteteli wa Bantu, the national paper owned by the Chamber of Mines, announced her win in its East London local news section. According to Umteteli, Ambrosia awarded a 21-piece tea set worth £1.10 to a winner of the word-building competition each week.Footnote 45 By 1938, Ambrosia claimed that the word-building competition prizes were being awarded on a daily basis, and that it had already given out 91 tea sets (Fig. 1).Footnote 46 If Umteteli's figure for the value of each tea set is correct, then Ambrosia was investing considerable funds in this campaign to attract its intended audience of literate female buyers. The fact that 91 women had won prizes also suggests that this audience was paying attention and participating in the campaign.

Fig. 1. Ambrosia Tea advertisement listing Mrs. Ethel Matole of Lady Frere as the winner of the ninety-first tea set prize in the Ambrosia word-building competition. Source: Umlindi we Nyanga, 15 July 1938.

The word-building competition and its prize of a tea set were not explicitly reserved for women, but the participants were largely women. Of the 21 people named in lists of Ambrosia prize-winners, only one was a man.Footnote 47 The gendered nature of this prize competition was enabled not only by the association between women and the work of cooking and brewing tea, but also by African women's higher rate of literacy in early twentieth century South Africa. In her 1936 anthropological study of Pondoland, Monica Wilson observed that girls attended school more frequently and for more years than boys.Footnote 48 Similarly, when the SAIRR started a ‘Literacy for Africans’ course in Johannesburg's Orlando township in 1947 the initial group of students was entirely women.Footnote 49 The earliest census data on literacy indicate significantly higher literacy for women, a trend that seems to have begun in earlier decades. In urban East London in 1960, African women's literacy rate was 64 per cent compared to 57 per cent for men, and women were twice as likely as men to report fluency in English.Footnote 50

A gap in literacy might be one reason why advertisements targeted at women, in Umlindi and other Black South African newspapers, tended to have more text than those targeted at men. The advertisements for Ambrosia tea, Palmolive beauty soap, and Kowie's branded baby medicine usually had over 125 words in the text of their advertisement. Advertisements for cigarettes, bicycles, and flashlights, which featured images of men, had fewer words. Cigarettes, in particular, usually had fewer than ten words in the advertisement. The ‘word-building competition’ and the lengthy testimonial statements from female consumers therefore marked Ambrosia as a specifically feminine product, and one that by its text-heavy advertising encouraged educated women to be proud of their literacy in Xhosa and English.

Who were the women who appeared in Ambrosia advertisements as its model customers? They were mainly rural residents, whose participation in consumer culture occurred through print as well as in shops. Of the 36 people whose names and addresses appeared in Ambrosia advertisements, only 3 lived in East London. Four participants gave addresses in King Williams Town or Queenstown, both towns less than half the size of East London. All 29 others had addresses in smaller towns and villages across the eastern Cape. This rural distribution of customers reflects the fact that Umlindi's parent company focused its trade in the ‘Native Territories’. Umlindi’s owners recognized the fact that for rural African consumers, buying consumer goods was of necessity a text-based process, because of the difficulty of shopping in person.

The boosters of the African consumer market proclaimed that ‘the African is becoming a discriminating purchaser, and, seeing he pays cash and is civil and well-mannered in a shop, who can blame him?’Footnote 51 The trouble for many African consumers, however, was precisely in accessing a shop. In urban areas, most municipalities prohibited trade by Africans within the locations. Africans were permitted as customers in white-owned shops in urban areas, even in the opulent department stores (as long as they were ‘respectably’ dressed) that appeared in cities in the early twentieth century.Footnote 52 However, the distant location of these stores in white commercial areas created racial barriers to shopping. Wilson's 1936 research in East London showed that women in segregated urban locations often walked long distances to purchase even basic groceries.Footnote 53

For consumers in the rural eastern Cape, the problem of distance was even greater. The ‘trading stations’ scattered across the countryside were required — by a 1922 law that enshrined longstanding custom — to be at least five miles from the nearest competitor.Footnote 54 This protected the monopoly of white traders, who often acted as creditors to the local population and as recruiters of indebted men to work in the mining industry.Footnote 55 Trading stations were centers of social life but carried a very limited range of consumer goods. According to one 1930 report, the stock lists of Transkeian traders had remained virtually unchanged since the 1880s. Moreover, the foodstuffs and household items sold at these trading stations were not sold in branded packages; traders bought sugar, tea, soap, and patent medicines wholesale and repackaged them in small quantities (at considerable mark-up). ‘The tea’, according to this report, ‘consists of the siftings of well-known brands’.Footnote 56 For those with some disposable income and a desire to purchase modern consumer goods, the offerings at local trading stores would have been inadequate. Indeed, the representatives of the Transkeian Bunga, or council of government-appointed headmen, frequently criticized the monopolistic practices of rural traders.Footnote 57 Between 1937 and 1945 the topic of discrimination in trading license issue was among the most frequently discussed topics in the Natives’ Representative Council, and was the subject of more resolutions than the poll tax or beer halls.Footnote 58 The substance of these complaints was not only the economic discrimination against African entrepreneurs, but also the burden of inconvenience for African shoppers.Footnote 59

In this context, the Ambrosia advertising campaign in Umlindi we Nyanga was an attempt by Baker, King and its subsidiary companies to reach rural consumers who could not be satisfied by the goods on the trading store counter. For literate rural dwellers, newspapers and mail order catalogues were alternative sources of information about branded consumer products.Footnote 60 Advertisements in the early twentieth century Black South African press often advised readers to request a mail order catalogue.Footnote 61 Mail order catalogues allowed African consumers, as long as they were literate, to circumvent the inconveniences of shopping either in urban areas, where retail legislation kept shops out of African locations, or rural areas, where traders’ monopolies reduced consumer choice.

The importance of text-based consumer culture for Africans in early twentieth century South Africa can best be seen by contrasting Umlindi's prize competitions with those of East London's Daily Dispatch which catered to a white Anglophone audience in the eastern Cape region. During the 1930s the Daily Dispatch's advertisements included prizes and competitions, but these prizes had to be claimed by the reader in person. Garlicks department store, for example, offered a free pair of women's stockings to be collected at checkout if the customer spent over a certain amount.Footnote 62 By contrast, prize competitions by Ambrosia and Kowie Medicines in Umlindi always required the readers to write to the advertiser. Winners were often announced in the paper. Advertisements in Umlindi were therefore a more public, participatory forum than those in the Dispatch.

By emphasizing ‘intelligence’ and ‘wisdom’, running a prize competition that demanded written fluency, and printing lengthy testimonials by notable customers, the Ambrosia marketers recognized the centrality of literacy to aspirational African consumer culture in the eastern Cape. Hindered from easy access to shop counters by racial monopolies on trade, educated African women consumers, especially in rural areas, were well placed to appreciate the attractions of a text-based consumer culture. When Ambrosia printed the names, addresses, and statements of its consumers in advertisements, the company proclaimed to the ‘school’ community of the eastern Cape that rurality was no barrier to participation in modern culture.

Buying tea in the 1930s eastern Cape: female consumers and respectability

Women participated in Ambrosia Tea competitions and testimonials not simply because they wanted to win a tea set, but because tea consumption carried specific connotations in the early twentieth century eastern Cape. The publicity of participating in an Ambrosia Tea advertisement was a valuable opportunity for African women consumers, whose moral habits of consumption were under scrutiny. Tea was a safely respectable product because of its long association with temperance and Christianity. The valorization of ‘respectable’ behavior and lifestyle was not confined to the small contingent of African professionals. Rather, values such as orderliness, education, and temperance were widely accepted as desirable by urban poor and working-class Africans as well as the middle class.Footnote 63 In the rural eastern Cape in the early twentieth century there was a significant population of people who subscribed to the same ideals of education, temperance, and respectability, even if they did not personally attend church or school. These people sometimes described themselves as ‘school’ people in opposition to Xhosa cultural traditionalists who described themselves as ‘Red’.Footnote 64

Government officials and white entrepreneurs were not the only parties interested in Black consumer habits in the interwar period. Within the Black press, consumption and commercialism became entangled in debates about modernity and morality. For some, consumer goods were the currency of respectability and a sign that African people were ‘politically mature’.Footnote 65 On the other hand, the temptations of consumer goods caused some to worry. Thomas has shown how women's use of skin-lightening cosmetics ignited a debate in the pages of Bantu World about whether cosmetics were undermining Africans’ racial pride and thus their case for equality in South Africa.Footnote 66

Although from the owners’ perspective the purpose of Umlindi was to sell products, Godlo and the others who wrote for the paper had a mixed, sometimes ambiguous view of consumption. For the first few months of 1936, the paper ran a column called ‘The Wise Buyer’ in which Godlo gave advice about spending one's money wisely. According to Godlo, ‘there is not anyone in the world who does not imagine himself to be very clever at shopping… some women think they are even wiser buyers than men!’Footnote 67 In the Wise Buyer column of the next month, A. P. Mda clarified that the true secret to wise buying was buying well-known brands that others have recommended.Footnote 68 However, like Bantu World's readership, not all Umlindi correspondents agreed that branded products themselves were always good.Footnote 69 Although Umlindi advertised cigarettes and women's cosmetic products, one writer thought that these products made women look too much like ‘European girls of a lower station’.Footnote 70

Women also debated just what types of consumption were good. Educated Christian African women in the eastern Cape supported a Victorian ideal of marriage, with the husband as a breadwinner and wife as homemaker. At the same time, they also defended women's financial independence. Florence Jabavu, wife of prominent educator and politician D. D. T. Jabavu, wrote in 1929 to defend the historical claims of Xhosa wives to the use of their own income. She praised the days when ‘woman had to be the executive manager of her household… without having to appeal to her spouse for the provision of multifarious minor needs’.Footnote 71 In modern times, women ought to be encouraged again to be ‘manager of the home’.Footnote 72 Jabavu's defense of women's economic independence was part of a wider crusade by educated Black South African women to teach uneducated women housekeeping. In the 1920s, African women founded several home improvement societies in the eastern Cape, which will be discussed in detail below. Significantly, one point of contention between the two main rival societies was a matter of consumption and purchasing: whether women ought to wear traditional Xhosa dress or European clothing.Footnote 73

Similar contentions about consumption and virtue are evident in the few Umlindi articles by women. In 1939 the paper asked ‘six highly intelligent and educated ladies’ to write in with answers to the question of whether ‘young people of to-day are as good as or bad as the young people of, say, 25 years ago’. Mrs. Petse argued that ‘people of today are more clever’ than in the past, but feared that this was accompanied by overindulgent habits. ‘They like drinking for drinking's sake’, she worried, and ‘they seem interested in bad habits’. Mrs. J. Sonqishe pointed out that higher education and incomes could also be beneficial, because youth could now understand things they ‘read from books and see at the cinema. They are learning new ideas’.Footnote 74 All of the six respondents mentioned something about income and living standards in their evaluation of morals. This article provides a hint of the ambiguous place that money and spending habits had for ‘school’ African women in the eastern Cape.

If cosmetics, clothing, cigarettes, and cinema-going were contested markers of respectability, tea was a safe symbol of ‘the wise buyer’. Since the mid-nineteenth century, tea had been the antithesis of beer in South African temperance discourse. Nineteenth-century converts to Christianity in the eastern Cape had adopted temperance as a marker of their identity, and so drinking tea meant an association with ‘school’ culture. For example, Wilson found that in 1930s East London, ‘tea parties’ were the preferred social gathering of Christian-affiliated Xhosa people. In rural Pondoland itimiti (from ‘tea meeting’) was the term for a convivial gathering with refreshments, even when beer rather than tea was served.Footnote 75

In urban areas across South Africa in the early twentieth century, the morality of beer drinking was further politicized when municipal governments attempted to control the profits of the beer trade by making municipal beer halls the only legal source of alcohol for Africans.Footnote 76 The East London city council did this in 1937, prompting protest by women of the urban locations who earned a living brewing beer.Footnote 77 After the ban on home brewing, 200 women marched on East London's City Hall to protest the law.Footnote 78 Umlindi responded by critiquing the City Council's mercenary scheme and defending the rights of urban women to protest. However, in line with Godlo's commitment to temperance, the paper also promoted temperance and tea-drinking as the solution to the whole problem.Footnote 79 In this way, the significance of tea as the drink of respectable African people was elaborated across multiple sections of the newspaper through the combination Godlo's interests, the participation of female readers in advertisements, and the testimonial marketing strategy of Ambrosia Tea.

However, this image of respectability was just that: an image of how some women wanted to be perceived. In reality, the lines between respectable tea and immoral alcohol were more blurry. Mrs. Ntsonkota, whose photograph appeared in five Ambrosia advertisements, was arrested in 1938 for running a shebeen where she reportedly served liquor from the teapot she won in Ambrosia's word-building competition.Footnote 80 What is important about Mrs. Ntsonkota's story, however, is that she successfully represented herself as a tea consumer and gained the benefits of reputation and a prize despite the divergence of this image from her other occupations.

Buying consumer products was a morally and politically charged activity for African women in 1930s South Africa, between the dangers of overindulgence in superfluous products, and the necessity of consuming respectable goods like tea rather than immoral ones like beer. For some African women in the eastern Cape, participation in Ambrosia's advertisements could be an avenue for self-promotion as a modern, wise consumer.

Tea and home improvement

Ambrosia's association between tea and wise motherhood provided an opportunity for collaboration with the burgeoning home improvement movement, whose leaders used the space of the testimonial advertisement to promote their own specific vision of an African woman's proper duties of consumption. Janet A. B. Ntisana of Mnyameni and Rita Marambana of Peddie were featured in Ambrosia advertisements that were unusually large and detailed. Their testimonials were each reprinted four times between 1939 and 1940. Ntisana's advertisement contains two photographs and several paragraphs of text. Marambana's advertisement contains one large photograph of the writer and several paragraphs of text. Rather than explicitly promoting Ambrosia Tea, the primary purpose of these texts is to call African women to join home improvement societies.

Beginning in the 1920s, women from well-off, mission church-affiliated backgrounds founded home improvement societies in the rural eastern Cape.Footnote 81 They hoped to teach poor women practical skills for cooking, cleaning, gardening, and first aid. Rita Marambana founded the Peddie Home Improvement Society in Peddie, a small town seventy kilometers east of East London, in 1922.Footnote 82 She was a teacher and was married to Knight Marambana, the first African inspector of schools in the eastern Cape.Footnote 83 Within the next few years, other elite women in the eastern Cape had followed Marambana's lead. In 1927, Florence Jabavu founded the African Women's Self-Improvement Society; its motto ‘zenzele’ (‘do it yourself’ in Xhosa) later became the general term for all home improvement groups.Footnote 84

These home improvement society leaders used the language of Christian feminine domesticity that had been proclaimed by missionaries in southern Africa since the nineteenth century.Footnote 85 Eastern Cape home improvement leaders were also motivated by their awareness of African women's increasing responsibility for homestead economies, as more men were incorporated into the migrant labor system in the early twentieth century.Footnote 86 Given the interest of elite African Christians in news of African American racial ‘uplift’, Marambana and Jabavu may have been inspired by the Jeanes movement in the United States, or similar education projects at Tuskegee.Footnote 87

Indeed, African American women in South Africa did influence women's home improvement groups. Susie Yergan came to South Africa in 1916 to work with her husband for the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA). In 1935 she founded the Bantu Women's Home Improvement Association.Footnote 88 Yergan's group grew quickly, and by the early 1940s had absorbed Marambana's original Peddie-based group.Footnote 89 Early on there was a marked rivalry between Yergan's Bantu Women's Home Improvement Association and Jabavu's African Women's Self-Improvement Society. Yergan's group had a larger membership, but Jabavu criticized Yergan's American prejudices against the positive qualities of Xhosa culture.Footnote 90 By the early 1940s, however, the two rival groups had begun a rapprochement, which eventually led to a merger.Footnote 91 Therefore, despite the personal rivalries between Yergan and Jabavu, their organizations were widely recognized as belonging to the same movement.

The various home improvement societies were well established in the eastern Cape by the middle of the 1930s. Although their numbers were not large, branches were widely distributed across the Ciskei and Transkei, with a strong concentration in the Alice-Peddie region of the Ciskei. A home improvement society (perhaps affiliated with Jabavu's society) was formed in Qumbu, in the eastern Transkei, in 1930. By 1932 it was so well established that its annual meeting was a popular local event, featuring a public concert and a speech by the local chief.Footnote 92 In 1938, Jabavu's African Women's Self-Improvement Association had fifteen branches, while Yergan's association had sixty-three branches and almost two thousand members.Footnote 93 In addition to official members of each branch, the home improvement societies also tried to attract the attendance of ‘the backward masses’ (in the words of one leader in the 1940s).Footnote 94

This, then, was the movement which Marambana and Ntisana were given opportunity to support in their testimonial advertisements. It is possible that Umlindi's editor, R. H. Godlo, personally arranged the two endorsements. The newspaper was at its core an advertising venue, and, as such, Godlo sometimes wrote pieces promoting consumption.Footnote 95 Therefore Godlo may have recommended testimonial writers from among his acquaintances in the eastern Cape social elite. Janet Ntisana and her husband, for example, were well-known enough in the eastern Cape that their activities were reported in the social columns of Umteteli wa Bantu.Footnote 96 Both the Godlo and Marambana families were active in the Wesleyan Methodist church, and the Marambanas visited East London regularly.Footnote 97 Moreover, Godlo's wife Hilda, a social worker, also founded a home improvement society in East London, which would have brought her into contact with Ntisana and Marambana.Footnote 98 Whether through Godlo's direct influence or some other channel, the directors of the Ambrosia campaign evidently considered these two home improvement leaders to be fitting representatives of their product.

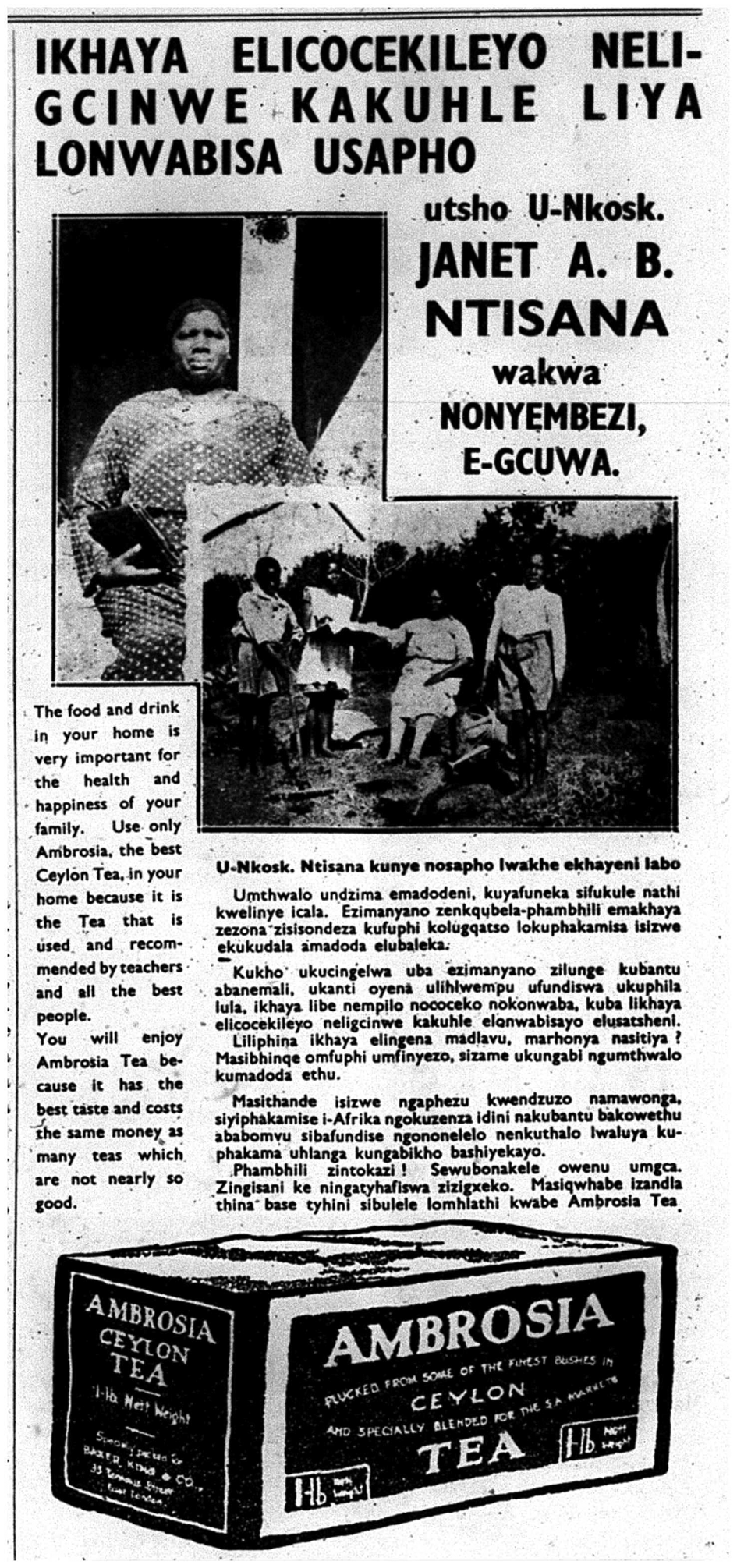

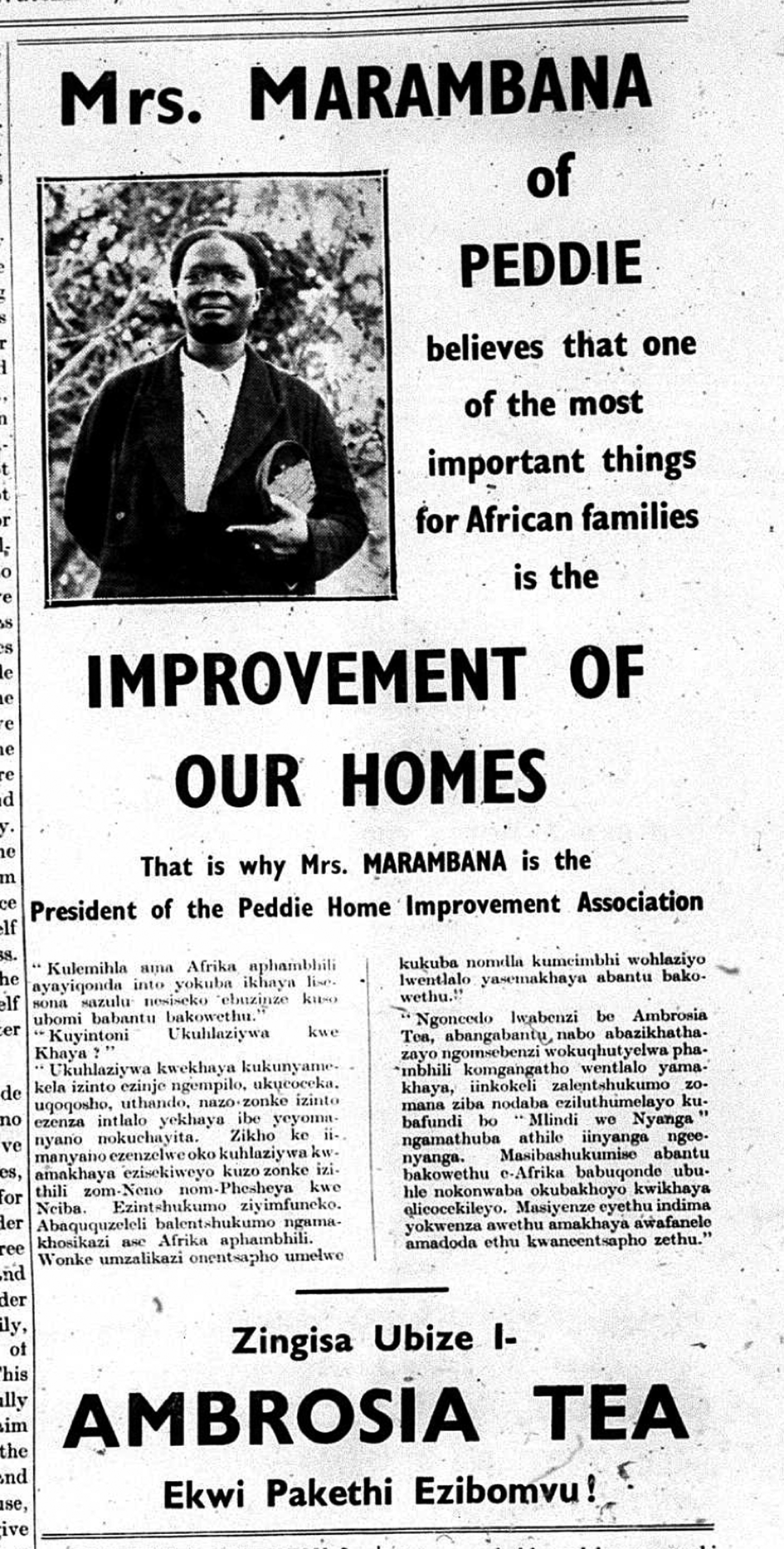

Marambana and Ntisana's testimonials do display some of the modern household products, including Ambrosia tea, that were promoted by Umlindi. Ntisana's testimonial does not contain any specific endorsement of Ambrosia Tea, or even mention tea-drinking in general, aside from a closing statement which asks women ‘to clap our hands and be thankful for this paragraph about Ambrosia Tea’. However, the photograph which accompanies her testimonial is full of the consumer goods that were advertised in Umlindi we Nyanga (Fig. 2). In the photograph, Ntisana is seated on a chair in a garden. Three children stand around her, one pointing a watering can toward the ground, one holding a rake, and the third presenting a tray with a teapot. This photograph may well have been staged specifically for the advertisement. The products displayed emphasize Ntisana's status as a mother who has effective control of the physical space of her home, as represented by the garden and gardening tools, and the members of her household, as represented by the neatly-dressed and industrious children. Marambana's advertisement (Fig. 3) contains a single smaller picture of the testimonial writer, showing her looking directly at the camera and smiling, wearing a collared blouse and jacket, and carrying a handbag. These images of respectable rural African motherhood suited the marketing strategy of Ambrosia as well as the goals of the home improvement movement.

Fig. 2. Ambrosia Tea advertisement featuring Mrs. Ntisana.

Source: Umlindi we Nyanga, 15 November 1939.

Fig. 3. Ambrosia Tea advertisement featuring Mrs. Marambana.

Source: Umlindi we Nyanga, 15 July 1939.

Indeed, Marambana's testimonial hints at a possible collaboration between the commercial newspaper and the home improvement associations. After describing the importance of home improvement, her testimonial concludes with the hope of cooperation between Ambrosia and Umlindi and the home improvement societies:

With the help of Ambrosia Tea, the people who are concerned with the work of upholding the quality of social life in the homes, and the leaders of movements, will find news which they will send to readers of Mlindi we Nyanga when they have some opportunities from month to month. We must move our African people to understand the beauty and joy that happen with a clean home.Footnote 99

In this statement, Marambana suggests an ongoing relationship between ‘the leaders of [home improvement] movements’, Umlindi we Nyanga, and Ambrosia Tea, in which the newspaper will print news about the women's organizations. Their interests would overlap in this area, since all parties were trying simultaneously to attract and create a respectable, domestic, female audience.

However, the home improvement leaders’ statements promote a different ethic of feminine consumption than that advanced by the Ambrosia campaign as a whole. In their testimonials, Ntisana and Marambana shift focus away from ‘intelligence’ as the primary characteristic of ‘wise mothers’. Instead, their testimonials emphasize the value of cleanliness, order, and devotion to children and husbands, with a particular emphasis on cleanliness. The word ‘cleanliness’ (ukucoceka) appears five times across the two testimonials. Like home improvement society leaders elsewhere in Africa, they drew a connection between cleanliness, virtue, and national or racial progress.Footnote 100

While they did not provide a specific definition of household cleanliness, both writers implied an opposition between cleanliness and ‘Red’, or traditionalist Xhosa, lifestyle. For example, Ntisana called on her readers to ‘raise up Africa by making sacrifices and teaching our people who are Red’.Footnote 101 This statement implied that members’ housekeeping would be modelled on Western definitions of cleanliness.Footnote 102 However, Ntisana and Marambana both emphasized that cleanliness was the result of determined physical effort rather than commodities like cleaning products or furnishings. Ntisana argued against ‘the idea that [home improvement] unions are only good for people who have money’. On the contrary, she said, ‘the union teaches a poor person to live simply’. Ntisana's text, especially, is studded with forceful imperatives to ‘act decisively’, to ‘move forward’, and to ‘hurry on’, which convey her message that effort rather than material possessions created a proper home.Footnote 103

The rewards of these rigorous efforts in home improvement were not intelligence and sophistication, as Ambrosia had stressed in some of its advertising. Rather, the two leaders drew the connection, familiar in contemporary doctrines of racial uplift, between improvement in family life and the success of the nation or race.Footnote 104 As Meghan Healy-Clancy and others have recently argued, African women's interest in welfare and housekeeping also drew on an indigenous concept of public motherhood, in which the feminine domestic was not the opposite of the masculine political sphere.Footnote 105 Marambana stated: ‘the home is the crucial factor that advances the life of our people’.Footnote 106 Ntisana similarly claimed that ‘the program of home improvement will unite us in the race of lifting our nation’. She went on to explicitly contrast this love of nation with motivations to individual gain. ‘Let us love the nation more than profit or privilege’, she wrote.Footnote 107

Ambrosia's two home improvement testimonial writers were in many ways perfect representatives of Ambrosia's ideal ‘wise mother’: they were married, mature mothers of families, and leaders of an energetic movement to improve African family life. However, in their testimonials for Ambrosia, Marambana and Ntisana remained sceptical that progress could be purchased.

Their testimonials were aimed at rural women who identified with ‘school’ culture but might or might not have been educated or well-off; such women were the home improvement movement's main constituents. These women might have been supposed by such companies as Baker, King to have the purchasing power for modern consumer goods. But Marambana's and Ntisana's admonitions to thriftiness suggest that they were aware of the sharp limitations to any vision of the modern African consumer-mother. Women in the Ciskei and the Transkei in the early twentieth century were not making leaps forward in their spending power, precisely because of the rise of proletarianized wage labor.

The newspaper boosters who boasted of the untapped spending potential of the African consumer were correct that rural Africans in the 1930s had more cash to use in trading stores. In the Ciskei and Transkei, the 1930s and 1940s saw a marked increase in the number of men who migrated to the mines and other industrial centers, in order to earn the necessary cash to pay taxes and support struggling rural homesteads. However, according to an analysis of Transkeian mineworkers’ earnings in the 1930s, real household incomes declined as the rural economy became cash-based. Most households did not produce enough food for subsistence, and entered cycles of debt to shopkeepers who also acted as mine recruiting agents.Footnote 108

South Africa's mineral revolution was accompanied by a ‘consumer revolution’ that brought new goods, tastes, and consumer desires into every part of South African society.Footnote 109 For many African consumers, however, many of these new desires remained out of reach. A small professional class of teachers, ministers, doctors, and clerks earned salaries to pay for modern consumer goods. But the limited evidence suggests that for many rural Africans in the eastern Cape, the 1930s were a time of increasing impoverishment and indebtedness, despite their increased access to cash from migrant labor remittances. As members of the eastern Cape elite, Marambana and Ntisana were natural ambassadors for a tea brand that associated education and respectability with the purchase of consumer goods. But these two women recognized that such purchases were not possible for many rural women who might aspire to them.Footnote 110 At the same time that they participated in the text-based, respectable, feminine consumer constituency that Ambrosia promoted, Ntisana and Marambana affirmed a different path towards the goal of becoming a ‘wise mother’.

Conclusion

The Ambrosia campaign is an early example of how a white South African company marketed its products to African consumers. This essay has argued that the marketing campaign, which invested considerable money and resources to its tea-set prize competition and its testimonials, was influenced by three significant factors. First, the Ambrosia campaign took place in the context of a global marketing campaign led by the Tea Market Expansion Bureau. Second, Ambrosia and its parent company which owned Umlindi we Nyanga were eager to take advantage of growing Black spending power, which observers heralded as labor migration and urbanization increased rapidly in the 1920 and 1930s. Third, Ambrosia and its owners (likely influenced by the paper's editor R. H. Godlo) recognized the importance of a rural audience of African women who embraced respectability as defined by literacy, education, temperance, and monogamous motherhood. These reading and writing women were a potential market for Baker, King's branded consumer goods, especially Ambrosia tea.

The specific connotations of tea-drinking in the eastern Cape made Ambrosia's advertisements an attractive venue for self-promotion by the women who participated in its word-building prize competition or wrote testimonials. Tea was associated in the Xhosa-speaking eastern Cape with ‘school’ or educated, Christian culture. As more African women migrated to cities in the 1920s and 1930s, African women's habits of consumption came under close scrutiny.Footnote 111 In a context where urban women were regularly arrested for brewing and serving liquor, drinking tea and participating in a promotional campaign for a tea brand were all ways that African women could identify their consumption as moral. This association between tea and upright, maternal responsibility could be valuable to many women, including those like Mrs. Ntsonkota who did sell alcohol in addition to more socially respectable activities.

Tea was therefore a significant commodity for elite — or aspiring elite — African women in the early twentieth century eastern Cape. The Ambrosia campaign in Umlindi we Nyanga suggests, however, that the medium of advertising mattered as much as the product itself. The Ambrosia campaign, through printing prize winners’ names and seeking out multiple testimonial writers, attempted to draw school-educated rural African women together through their participation in text-based consumption. Ambrosia offered its customers the opportunity to participate in a public network of wise buyers whose branded consumption would lift them out of the monotony, inconvenience, and logistical challenges of in-person shopping in segregated South Africa. In their testimonials for Ambrosia, Janet Ntisana and Rita Marambana recognized the value of the commercial newspaper as a way to attract interest in their home improvement societies. The newspaper also helped to promote the home improvement among potential members in the eastern Cape. Through their Ambrosia testimonials, Marambana and Ntisana expressed their own view of African women's potential for progress, one that depended on hard work and self-sacrifice rather than intelligence or purchasing power.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada [grant 752-2020-0068]. Thanks also to Laura Fair who encouraged this essay in its early stages, and to the editors and anonymous reviewers at The Journal of African History. The author's email is [email protected].

Competing interests

The author declares none.