The United States has been a study destination for Africans since the nineteenth century and, from African independence in the early 1960s, became their second most coveted country.Footnote 1 Among the tens of thousands African students who went to the United States, many influential personalities have made their mark on contemporary African history: Nnamdi Azikiwe (first president of Nigeria), Kwame Nkrumah (first president of Ghana), Eduardo Mondlane (founder of the Mozambique Liberation Front-FRELIMO), Wangari Maathai (first African woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize), Kofi Annan (Secretary General of the United Nations), and Allassane Ouatara (current President of Côte d'Ivoire).

The quantitative and qualitative significance of these African student mobilities in the United States does not, however, seem to have generated the same enthusiasm in historiography as the stays of students to the former colonial metropolises or the countries of the former communist bloc.Footnote 2 To my knowledge, research conducted so far on African students in the US has only given rise to one-off articles, has been addressed as part of a more general theme, or has focused on particular prominent individuals.Footnote 3 In many cases, these studies focus on a particular nationality of students.Footnote 4 This is notably the case in the work produced following the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency, which dealt with the ‘Kenyan student airlifts’, in which the president's father had taken part.Footnote 5 Finally, research on students who left for the United States since independence, by far the period with the most departures, is particularly scarce.Footnote 6

Moreover, the literature on African students trained in the United States since the 1960s is marked by a clear historiographical bias: it often views their experience only as a case study of the history of US diplomacy in the Cold War context. Their education is seen as a dimension of the American imperialist project in its race to win the ‘hearts and minds’ of the ‘Global South’.Footnote 7 This analysis is partly justified: the competition with the USSR was decisive in the establishment of US educational exchange programs in the second half of the twentieth century. But, as Ludovic Tournès and Gil Scott-Smith explain, ‘these perspectives tend to simplify or overlook the complex nature of scholarships, interpreting them in terms of simple success or failure’.Footnote 8 In addition, the role assigned to African actors is often limited to that of mere beneficiaries of assistance or agents of dissemination of American ideals. It thus overshadows the capacity for initiative and influence on the part of the political and educational actors in Africa.

Yet the imperatives, interests, concerns, and aspirations of these African actors have also shaped the process of US scholarship offers to Africans. At the time of decolonization, the dynamics that enabled many African students to travel across the Atlantic were based on the pan-African networks forged since the 1920s between African nationalist leaders and African American politicians and scholars. These networks proved indispensable to the creation of the US scholarship programs at the beginning of the 1960s. Then, it is the convergence of interests between governmental and academic actors on both sides of the Atlantic at the time of independence that has made possible the effective implementation of these programs in Africa. The participation of African leaders was indeed essential in the selection process of the candidates, as well as in the organization of the departures and the incentive to return.

While on the US side the training of African students was a Cold War strategic concern, African leaders sought to take advantage of foreign scholarship programs as postcolonial opportunities. On the one hand, they appropriated training projects in the United States to support their nation-building policies, and on the other, they used them to develop international cooperation and take advantage of the bipolar Cold War context. The training of Africans in the United States must therefore be considered less from the perspective of the American diffusionist project than as a process resulting from reciprocal dynamics. These dynamics were built on imbalances of power, but also, to use Frederick Cooper's words, on ‘the subtle and ongoing interplay of cooperation and critique, of appropriation and denial’.Footnote 9

The first objective of this article is to highlight the agency of African political and educational actors in the history of student mobility in the United States at the time of independence.Footnote 10 Through this case study, it also aims to shed light on the broader process of making postcolonial Africa, by highlighting the role played by transnational educational dynamics. From a more general perspective, this article will thus seek to put African issues and actors back into the history of student mobility in the United States and, in turn, assess the impact of US scholarship programs on the history of African nation-building. For this, I will focus on one of the pioneering US scholarship programs, the African Scholarship Program of American Universities (ASPAU). ASPAU offers an interesting case study in that it was the product of several actors — including governments, philanthropic organizations, and academic institutions — and, consequently, pursued a combination of political, developmental, and educational objectives. It was also the first major US scholarship program for almost all African countries, sponsoring nearly 1,600 students from 34 countries who graduated in the United States between 1961 and 1975.Footnote 11

I will specifically address the launching of ASPAU at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s, as it reveals the decisive role of pan-African connections and networks in the emergence of African student mobilities in the United States. It also highlights the role played by the African and American academic communities in shaping scholarship projects. Finally, the launching of ASPAU also sheds light on a number of challenges and dilemmas of postcolonial governance. The participation of African leaders in the program indeed reflects the issues they faced and the strategies they adopted as they came to power. While they sought on the one hand to implement their national political agendas and consolidate their authority locally, they were subject to exogenous factors and inevitably caught up in global power relations. This was particularly true regarding the development of higher education. It was indispensable for implementing nation-building and Africanization policies and for responding to the imperatives of the global developmentalist project and at the same time it was the object of a fierce competition between Cold War powers. ASPAU represented an opportunity for African leaders to play a role in these complex local and global Cold War interactions that strongly conditioned the establishment and viability of their new African states.

In the first part of the article, I will present the transatlantic network that was at the origin of ASPAU. The second part will be devoted to the launching and implementation of the program in Africa, made of pressure and interested cooperation. In the third part, I will show how and why ASPAU was perceived as an opportunity by governments, educational circles, and students in Africa. Finally, in the last part, I will look at the processes that eventually led to the termination of ASPAU, from the growing opposition of African academics to the questioning of ASPAU's effectiveness by the US government. The migration experience of African students per se will therefore not be the focus of this article, although the motivation of the scholars and their visions for the program will be presented.Footnote 12 Their testimonies reveal that, like the African political and educational leaders participating in the program, they sought to use ASPAU to advance their agendas in the uncertain but also hopeful context of a newly independent Africa.

A transatlantic network for Africans training in the US: the African American Institute

The first training trips of Africans to the United States date back to the mid-nineteenth century. At that time, American missionaries began sending young West Africans to American colleges for religious training. From the interwar period, pan-African connections established between intellectuals and militants on both sides of the Atlantic allowed African nationalist leaders to leave for their education. They often studied in the ‘Black Colleges’ where the meeting with African American teachers and students as well as the experience of segregation consolidated their anticolonialist convictions. Kwame Nkrumah, future first president of independent Ghana, notably enriched his pan-African consciousness on the campuses of Lincoln University and the University of Pennsylvania between 1935 and 1943.Footnote 13

During the Second World War, departures for the United States almost completely stopped. But by the end of the 1940s, three decisive and complementary factors made training abroad a real option for a growing number of young Africans: decolonization, development aid, and the Cold War. Indeed, higher education, as a part of the developmentalist project, became both a geostrategic concern for the US and Soviet powers and a central element of the political projects of African nationalist leaders.Footnote 14 On the one hand, the training of African elites was seen by the Soviet and American governments as a means of increasing their influence in a region that was gradually emancipating itself from colonial rule. Based on the idea that education was a decisive factor in the modernization of these developing countries, first the USSR and later the US began to invest in the education of Africans in the late 1950s.Footnote 15

On the other hand, African leaders’ demands for more higher education were increasing, with the target of training the leadership of the future independent states they were calling for.Footnote 16 After independence, this need for university training became a necessity in view of the lack of qualified personnel in their young countries. To fill the void left by the departure of former colonial officials or to replace the large number of expatriates who still held key government or university positions, new heads of states saw the rapid training of African modernizing elites as a priority.Footnote 17 Yet, in Africa in 1960, there were only 20 higher education centers (not counting South Africa, where most of the universities were for whites only). Most also offered only courses in two or three disciplines.Footnote 18

To meet this strong demand for higher education, some African politicians and educators chose to rely on training abroad. In 1959, Kenyan trade unionist Tom Mboya set up ‘airlifts’ that allowed 800 Kenyan students to study in the United States until 1962.Footnote 19 At the same time, Nigerian educator Stephen Awokoya was visiting Harvard University and meeting with David Henry, the university's admissions director. They talked about the imminent independence of Nigeria and Awokoya suggested that Harvard could celebrate the event by offering scholarships to Nigerian students. David Henry, aware of what was at stake with the upcoming independence of many African countries and concerned about Harvard's international stature, accepted the idea. He also managed to involve several other prestigious East Coast universities. For his part, Awokoya obtained assistance from the Nigerian government for travel expenses. This is how the Nigerian-American Scholarship Program (NASP) was born, which allowed 24 Nigerian students to begin their studies in the United States in the fall of 1960.Footnote 20

Building on the success of NASP, David Henry wanted to create an identical program for the entire African continent. But in order to achieve this ambitious project, he had to find: 1) a solid administrative structure; 2) a greater financial contribution; 3) political support, in Washington as well as in Africa.Footnote 21 He then turned to the African American Institute (AAI), a private American organization, which would satisfy all three of these needs at once. AAI was founded in 1953 in Washington, DC, for the purpose of ‘building friendly ties between the people of Africa and the Unites States . . . and assisting in the education and training related to the economic and social development of Africa’.Footnote 22 It was led by a range of personalities who advocated for greater US public and private investment in Africa. The membership of its Board of Trustees in 1960 sheds light on this network. It included several members of philanthropic foundations such as Dana S. Creel of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and Alan Pifer of the Carnegie Corporation of New York. There were also politicians, like Democratic congressman Chester Bowles, who were in charge of promoting African education at the highest political levels. Businessmen, such as Harold K. Hochschild of the American Metal Climax Inc., for their part, encouraged American companies to invest in Africa.Footnote 23

But it was above all its trustees with direct contacts in Africa that enabled AAI to become a key figure in the creation of US scholarship programs. The most influential of these was the African American academic Horace Mann Bond. Born in 1904, Bond had forged ties with several future African leaders on US campuses during the interwar period, such as Azikiwe.Footnote 24 This pan-African network was further consolidated after the Second World War during Bond's numerous trips to Africa, and by his activity as president of Lincoln University in hosting many African students and leaders –– as when he awarded an honorary doctorate to Nkrumah in 1951.Footnote 25 Bond also worked to create connections between his African contacts and American business, political, and philanthropic circles. Thus, in 1952, he acted as an intermediary between the government of the Gold Coast (later Ghana) and the American Anaconda Copper Company with a view to the latter's participation in the Volta River dam project.Footnote 26

Bond put his network at the service of AAI, allowing it to establish a foothold on the African continent. It was thanks to Bond that AAI established its International Advisory Council in 1955 in order to provide advice and policy guidance to its Board of Directors. Several future West African heads of state participated in this Council: William V. S. Tubman of Liberia, Obafemi Awolowo and Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria and, of course, Kwame Nkrumah of the Gold Coast.Footnote 27 AAI also established offices in Accra in 1958, followed by offices in Leopoldville, Lagos, and Dar es Salaam.Footnote 28 This implantation of AAI in Africa was backed by most African leaders, as evidenced by the letter of support that Nkrumah wrote to Emory Ross, AAI's president, after the opening of the Accra office: ‘I am most appreciative of the good work your Institute aims to do for our two continents, and . . . my government would give the Institute every possible assistance in its work in Africa’.Footnote 29

The fact that AAI was led in part by African Americans and presented itself as a nongovernmental and nonpolitical organization made it easier for it to establish itself in many African countries. However, AAI was actually working for US diplomatic and economic interests. In addition to their friendly ties with State Department officials, AAI leaders made no secret of their support to the national effort against Soviet expansion.Footnote 30 AAI was even financed in part by CIA funds between the mid-1950s and 1962.Footnote 31 In addition, the US government entrusted AAI with some aspects of its diplomatic activities –– including hosting African leaders on tour in the US –– which actually made it a parastatal agency.Footnote 32 Even Waldemar Nielsen, AAI's president, declared in 1962 that: ‘The view that AAI is essentially a private organization is thus unrealistic, for we have many public obligations. The US Government needs a well-qualified organization to carry out its affairs in Africa. AAI is and will remain primarily a government-contract organization’.Footnote 33

As a result of these entanglements, some African leaders were suspicious. For example, Sékou Touré, Guinea's first president, opposed the opening of an AAI office in Conakry in 1960.Footnote 34 But other African leaders chose to cooperate with AAI. They often did so in order to achieve their own political objectives. The Tanganyikan government used AAI's presence in Dar es Salaam to reach out to the US government, in order to invite it to participate in local education programs.Footnote 35 For his part, Azikiwe used his contacts within AAI to find financial and political support in the United States to carry out his project of founding the university in Nsukka.Footnote 36

Cooperation and influences: the creation of the African Scholarship Program of American Universities (ASPAU)

Since its founding, AAI had offered occasional scholarships to African students wishing to come to the United States.Footnote 37 In 1959, it sought to expand this activity by creating a large-scale program, but the especially high university fees in the United States deterred it from doing so. David Henry's program for African students had precisely the advantage of grassroots support from American universities, which committed to paying the full cost of tuition. AAI officials therefore decided to support the project when Henry presented it to them. They then used their network to help Henry secure the participation of both the US and African governmentsFootnote 38.

Henry first approached the Deputy Director for Program and Planning of the US International Cooperation Administration (ICA), James P. Grant, who happened to be a founding member of the AAI.Footnote 39 Accompanied by Loyd Steere, Executive Vice President of AAI, Henry met Grant in Washington, DC, in September 1960. Grant assured Henry and Steere of his interest in the program and proposed that ICA (which in 1961 became the United States Agency for International Development, USAID) should assume the students’ maintenance costs.Footnote 40 Until then, the US government had participated in educational programs for African students only occasionally, and had left philanthropic foundations to promote American interests through their education programs in Africa.Footnote 41 But when it realized that the Soviet Union had set up training programs for African students as early as 1958 and founded the Lumumba University for ‘Third World’ students in 1960, the US State Department decided to get more directly involved and sought to attract more African students to the United States by providing scholarship programs.Footnote 42 By bringing in these students and introducing them to the values of the ‘free world’, the US government sought to create a corps of elites who would later serve as a relay for its interests in Africa.Footnote 43

Henry and Steere also obtained the involvement of the Ford Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, which each pledged financial support to AAI for the administration of the program.Footnote 44 Participating African governments were also expected to contribute to the program, as they would pay for their students’ transportation. In April 1961, ICA and AAI signed a contract that formally established the program as the African Scholarship Program of American Universities (ASPAU). The contract also specified the overall objective of the program, which was to meet ‘the most urgent needs for manpower for the balanced and integrated economic and social development of the Cooperating Countries’.Footnote 45 In this sense, ASPAU was conceived and presented as a development assistance program for Africa.

Paradoxically, ASPAU was also a very elitist program. American universities did not commit to APSAU until they were assured that ‘in return of their financial commitment’, they would get ‘highly qualified students who had every chance to benefit from the experience and succeed up to expected performance levels’.Footnote 46 To this end, university officials would participate in all stages of the selection process, which included an academic record assessment, an aptitude test, and a personal interview.Footnote 47 The objective was clearly to select the African students who had achieved the best grades. The US government also endorsed this rigorous selection process that would help identify Africa's future leaders.Footnote 48 ASPAU was therefore based on a qualitative rather than quantitative approach to education. And the number of students selected in relation to the number of applicants clearly shows this: for the first year of the program — available in 18 countries — 8,000 applications were sent and only 239 students were selected.Footnote 49 A final total of 1,594 undergraduate students from 34 African countries came to study in 236 American universities between August 1961 and September 1975 (see Table 1).Footnote 50

Table 1. African students in ASPAU by country.

Source: AAI, Final Report ASPAU, Appendix IV.

The total cost of the program was $33.3 million. Major funders included USAID, which contributed $19.2 million, universities ($11.9 million), African governments ($1.3 million), and foundations ($325,000).Footnote 51 These figures reflect the predominant roles of the US government and universities in the program. In comparison, the contribution of African governments seems almost symbolic. Yet, African leaders were key for the creation of ASPAU. Indeed, they not only participated by paying travel expenses, but they were also indispensable to the AAI by performing the essential task of finding scholarship candidates. It was largely because it collaborated with its local contacts that AAI was able to establish ASPAU in many African countries and in many cases obtain the best candidates.

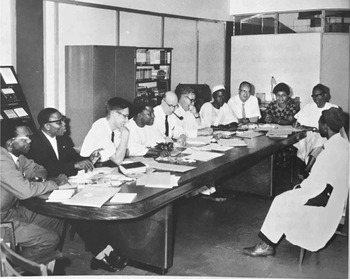

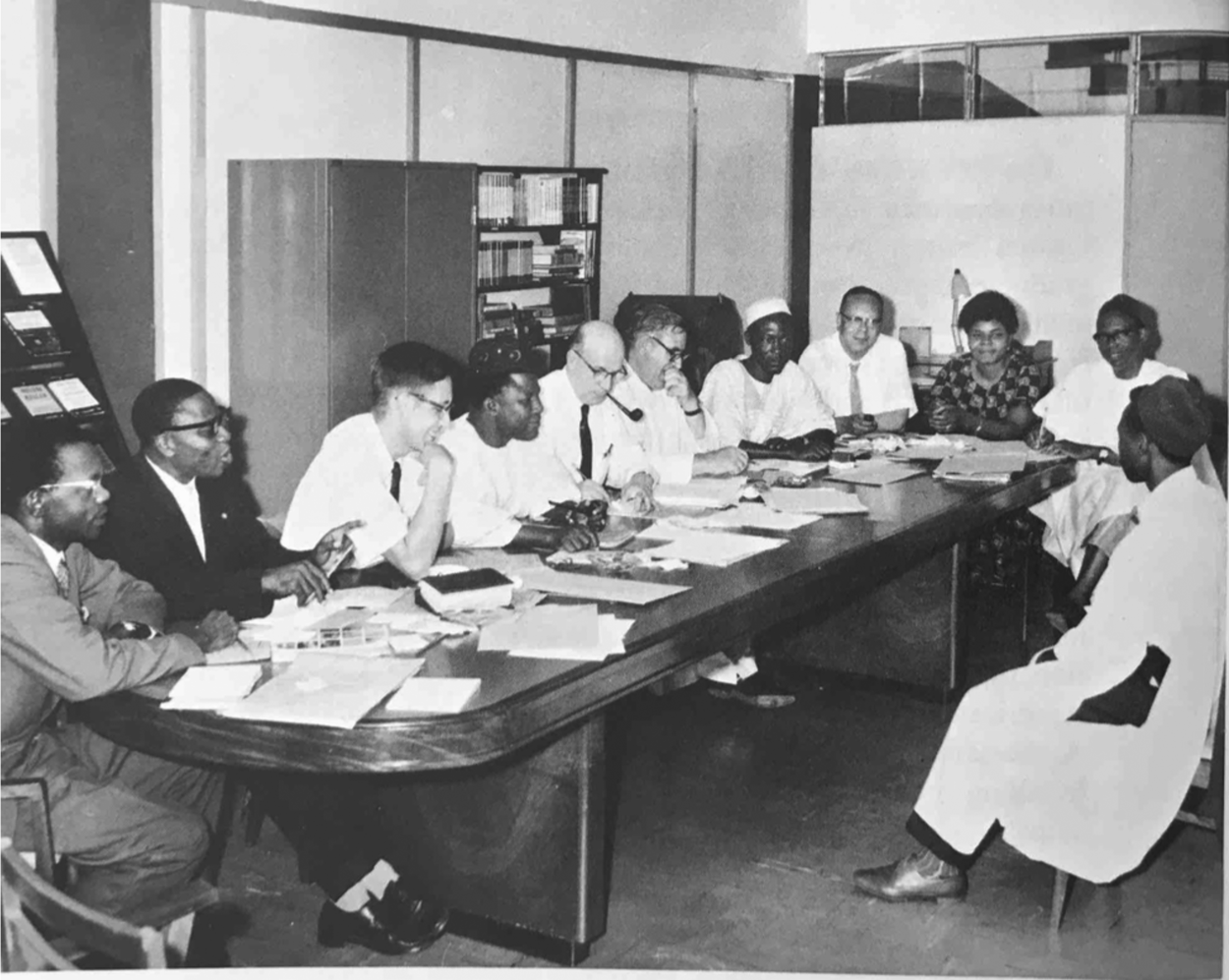

The AAI network in Africa was particularly useful for the creation of local selection committees that were indispensable for selecting ASPAU scholarship holders. These committees were established in almost every participating country and were composed of local and American political and educational officials (Fig. 1). They met every year and were responsible for the first screening of the records sent by candidates. They then interviewed the shortlisted candidates and proposed a list of potential fellows to the ASPAU executive committee. This committee, chaired by David Henry and composed of American universities’ representatives, finally decided on the definitive list of scholarship recipients who were distributed among the participating universities.Footnote 52

Figure 1. ASPAU Scholarship Board at work in Lagos, Nigeria (1964).

Source: RBFR, Folder 177, African-American Institute, African Scholarship Program of American Universities, Annual Report 1964–65, 10.

In many countries, ASPAU's launch also benefited from the political support of personalities close to AAI. This was the case in Nigeria, of course, where Azikiwe and Awokoya promoted the program to regional education authorities. Three hundred and seventy-eight Nigerian students were awarded ASPAU scholarships, a quarter of the total, making Nigeria the country that sent the most students to the United States.Footnote 53 In Cameroon, the Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Jean Betayene, was a key agent in the start-up of ASPAU. He had visited the United States in 1960 and was hosted and assisted by an AAI official, Jules Engel. Thus, when Engel arrived in Yaoundé in April 1961 to try to convince the Cameroonian government to participate in ASPAU, he went directly to Betayene. The latter promoted the program to his colleagues and introduced Engel to Prime Minister Charles Assale.Footnote 54 Following these meetings, the Cameroonian government decided to participate in ASPAU and, in the end, sent the third most students of any country, 121 in total.Footnote 55

These contacts, however, were not always sufficient. AAI's network in Africa was still brittle in 1960 and, above all, covered only part of the continent, with AAI being mainly located in English-speaking West Africa. In addition, ASPAU faced intense competition: in 1962, more than 130 donors, including 55 governments, were offering scholarships for African students to study abroad. The strongest competition came from France, the United Kingdom, Eastern European countries, and China.Footnote 56 In order to face this challenge and to involve ASPAU in as many countries as possible, AAI relied on its good relationship with the State Department. For example, the United States Information Service (USIS) participated in the distribution of ASPAU scholarship announcements in local newspapers.Footnote 57 Ada Otue Ezekoye, a Nigerian ASPAU fellow, remembered that it was the US Consulate in Enugu that directly contacted several high schools in eastern Nigeria to inform them about ASPAU. Consulate officials explained to the principals of these schools that the program was designed for ‘outstanding students’ and asked them to nominate their best candidates.Footnote 58

Using ASPAU: Africans’ training abroad as local opportunity

This collaboration between AAI and various bodies of the State Department was important for the effective establishment of ASPAU in Africa, especially in countries that were in good terms with the US government, such as Nigeria.Footnote 59 But ASPAU's success in gradually establishing itself in 34 African countries — some of which were clearly opposed to the United States — also relied on the leaders of these new states finding the partnership to be in their own interest. These leaders did not blindly commit to ASPAU. They assessed the potential benefits of the program for their government, country, and educational institutions. And sometimes they declined the offer or set conditions.

ASPAU could offer definite advantages to these African leaders. First, the fact that it was conceived and presented as a development assistance project could serve the modernization objectives that were at the heart of African governments’ economic programs.Footnote 60 Scholarships for study abroad also represented an economic advantage. A student trained with an ASPAU scholarship was much cheaper for his or her government than a student trained locally, especially considering that the vast majority of students in African universities received scholarships from their government.Footnote 61 ASPAU also represented an interest at the political level. For example, some African leaders tried to politically leverage US interest for their students. In Senegal, Dr. Franck, rector of the University of Dakar, agreed to discussions with representatives of AAI even though he felt that his university had enough capacity to accommodate all students wishing to pursue postsecondary studies. He therefore agreed in principle for six Senegalese students to go to the United States, but in exchange for as many American students. Through this maneuver, Franck was in fact seeking to counter the increasingly active presence of left-wing students on his campus. He hoped that the arrival at the university of ‘bright young Americans, good mixers and politically mature’ learners would make it possible to counterbalance the influence of the ‘leftist’ students. On the other hand, and according to the Inspecteur de l'Académie M. de Buissy, the participation of the University of Dakar in ASPAU was in agreement with ‘President Senghor's very strong wish to make of Dakar a truly international university’.Footnote 62

Senegal did not ultimately participate in ASPAU for its first year. Following the end of the Fédération du Mali and the departure of the Malian students from the University of Dakar, it found itself facing a shortage of students for the year 1961–2 and did not want to let any of them leave for the US.Footnote 63 But this setback for AAI in Senegal turned into an opportunity in Mali. Since Mali did not have a university, no longer wanted to send students to Dakar, and even wanted to reduce the number of those who went to France, there was a strong demand for scholarships elsewhere. Offers came quickly, and the Soviets and Israelis seemed to be a step ahead of the Americans. As ASPAU representative Robert L. Jackson wrote: ‘The Mali government find itself, therefore, with more scholarship offers than it can handle and our offer of five or six scholarships is simply another drop in the bucket’.Footnote 64 Taking advantage of this competitive climate, the Malian Minister of Education, Abdoulaye Singare, played on the competition. In an interview with Jackson, he expressed reservations about his government's ability to pay for ASPAU student transportation, noting that the Soviet and Israeli scholarships paid for everything. Faced with this strategy, AAI was forced to make compromises to make its offer more attractive.Footnote 65

The launch of ASPAU has also became a political issue in the context of growing protest against white rule in Central Africa. In Southern Rhodesia, white political and educational elites, who wished to maintain total control over educational matters and limit in particular the access of Africans to higher education, strongly opposed the establishment of ASPAU. As a reaction, African leaders, such as Ndabaningi Sithole or Nathan Shamuyarira, seized on the unique opportunity that ASPAU presented. They approached ASPAU officials and pledged to provide high quality African candidates for the program. The interest of these African leaders was also beneficial to ASPAU representatives, since Sithole and Shamuyarira quickly found qualified candidates and paid for their transportation, thus efficiently replacing the government of the white minority. Finally, AAI incorporated Sithole and Shamuyarira into its local selection committee, which helped to legitimize them as reliable interlocutors in the eyes of US officials.Footnote 66

Some governments initially refused to enter ASPAU, including not only Guinea and Senegal but also Ghana. Although he was part of the AAI network in Africa, Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah was skeptical of ASPAU from the outset. Since the Congo crisis in the summer of 1960 and the assassination of Patrice Lumumba in January 1961 — at the same time that ASPAU was set up — Nkrumah had become suspicious of the US administration.Footnote 67 But Nkrumah's initial refusal was also due to his willingness to promote the local option, which was more consistent with his project of Africanization of education. Thus, as AAI representatives met with Nkrumah to introduce ASPAU, his government was in the process of implementing a program to actively develop higher education in the country. As explained in the report of the Commission on University Education created for this purpose, the departure of students to study abroad needed to be better controlled and the government should insist ‘on the principle that scholars should not be sent overseas for training that is available in Ghana’.Footnote 68 The government followed these recommendations and commissioned the National Council for Higher Education to ensure that priority was given to Ghana's three universities, two of which had just been established.Footnote 69 ASPAU was in direct competition with the plans of the Ghanaian government, which therefore refused to enter the program.Footnote 70 Moreover, Nkrumah set Ghana on the road to socialism and wished that higher education could produce a ‘socialist-minded intelligentsia’.Footnote 71 For this reason, he created the Ideological Institute of Winneba in February 1961, and promoted studies in the East following the signing of cooperation agreements with the USSR in April 1961.Footnote 72

The Ghanaian government, however, did not cut ties with AAI. In January 1962, AAI President Waldemar Nielsen had a meeting with Deputy Minister for Education, J. B. Blay, about ASPAU. While Nielsen mentioned Soviet scholarships for Ghanaian students, Blay replied that American scholarships were nonetheless not banned and specified to Nielsen: ‘in line with our policy of non-alignment we wished to take advantage of all that could be offered from both East and West’.Footnote 73 Indeed, a year later, the government of Ghana announced that it agreed to allow Ghanaian students to participate in ASPAU.Footnote 74 But, as advocated by the National Council for Higher Education, it set conditions: students could only study in some scientific disciplines that were not taught enough in Ghana.Footnote 75 In fact, Ghanaian students in ASPAU were only allowed to apply for courses in chemistry, physics, agronomy, electrical engineering, etc.Footnote 76 Ghana was not the only country to take steps to maintain some control over ASPAU. In Tanganyika, the government of Julius Nyerere subjected ASPAU to governmental procedure: only students previously selected by a scholarship board composed of representatives of the government and the University of Dar es Salaam could apply for ASPAU scholarships.Footnote 77

Finally, ASPAU was an opportunity for the students themselves. The first motivation of most of those who applied was to get the best possible education. The ASPAU scholarship also represented a real opportunity for social advancement. Their application was therefore primarily based on personal motivations. As Almouzar Maïga, a Malian ASPAU scholarship holder, explained, the choice of a specific destination was often more the result of circumstances than of a desire to go to a particular country.Footnote 78 Therefore, even though some students were aware that the education of Africans was a Cold War issue, they did not see ASPAU as a way to embrace the US political project, let alone to fight against the spread of communism in Africa. The trajectories of the students during their stays and upon their return show that they were also far from being agents for the dissemination of American interests, as US diplomacy initially contemplated. Some did not hesitate to criticize publicly on campus the American intervention in Vietnam or to take up the cause of Cuba in its struggle against the United States.Footnote 79 Others, on their return, integrated into their countries’ governments and worked to implement socialist policies, nonaligned diplomacy, or even cooperation with Eastern European countries.Footnote 80

Resisting ASPAU: opposition and withdrawal

The main resistance to ASPAU in African nations came from educational circles. Their reactions to ASPAU reflect the tension between the two sometimes competing projects: training aboard versus training at home. As already seen, ASPAU was a highly selective and competitive program. The consequence was often that the best students were selected for ASPAU. AAI, the US universities, the State Department, and the philanthropic foundations participating in ASPAU wanted these best students. According to Robert S. Scrivner of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, ASPAU's approach was ‘to skim the cream of African students’.Footnote 81 The excellence of ASPAU fellows is confirmed by the results they obtained in the United States. Their success rate was 91 per cent, compared with only 50 per cent among American undergraduate students.Footnote 82 There was also an incentive for African students to stay in the United States after graduation. Sometimes their professors encouraged them to continue at the master's level, or even offered to provide funding for further studies.Footnote 83 Ultimately, only 64 per cent of ASPAU students returned home after graduation.Footnote 84

Prominent figures in African academia complained to ASPAU about this situation. They criticized the program for siphoning off Africa's best students, depriving their own universities of the leadership needed to strengthen their student body. Some also felt that ASPAU had created ‘local political pressures to accept the American idea of what constitutes “good university material”’.Footnote 85 As a result, academics took steps to try to stop this phenomenon. In Nigeria, Kenneth Onwuka Dike, the Vice Chancellor of the University of Ibadan, while involved in the implementation of ASPAU in the country, tried from 1964 to discourage the departure of students.Footnote 86 The Registrar of the University of Ife directly contacted AAI and urgently asked that no more scholarships for undergraduates be awarded to Nigerians.Footnote 87 But the Nigerian Federal Government saw things differently and did not really support the academics who opposed ASPAU. Like the Ethiopian government, it even financially supported students who wanted to stay in the US for further studies.Footnote 88

Other governments were more receptive to the arguments of academics and began to take steps to retain their students. In Zambia and Malawi, for example, as soon as national universities became operational, governments required that students be exclusively assigned to them.Footnote 89 Representatives from Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Uganda, Madagascar, and Congo (Leopoldville) urged their ASPAU students to return home after graduation. In a joint letter, they encouraged them to ‘seriously consider the importance of returning after the first degree to [their] respective nations, . . . to contribute to the progressive independence of [their] continent’.Footnote 90 For its part, the Ghanaian government created a special commission to collect information on all overseas students in order to ensure their return and help them find work.Footnote 91 These measures seem to have borne fruit, as there was a decline in demand for ASPAU scholarships and an increase in the number of returnees after 1966.Footnote 92

On the other side of the Atlantic, scholarship programs for Southern countries were also beginning to arouse mistrust. In 1965, a memorandum from the State Department explained that ‘US scholarship programs for undergraduate study in America create dissatisfied, misfit elites in many African countries’.Footnote 93 On its side, the Subcommittee on Africa of the US Congress created a commission on African Students and Study Programs in the US. After interviewing educational experts, the commission recommended to the US government that the priority for African education be placed not in study opportunities in the US like ASPAU but in African institutions.Footnote 94

From a more general point of view, Africa no longer held the interest in the US governing bodies that it had in 1960. As early as 1963, the administration of John F. Kennedy, followed by Lyndon B. Johnson's, chose to focus on other regions of the world, in particular Southeast Asia, where Vietnam was increasingly taking over US aid funding.Footnote 95 Finally, given the low return rate of ASPAU students, the developmentalist objective of the program and its ability to promote the dissemination of American interests were seriously questioned. USAID and the participating universities even found themselves in conflict on this point. Finding that the universities were reluctant to encourage students to return home, USAID decided to reduce its funding for ASPAU beginning in 1967.Footnote 96

Finally, AAI and the participating universities recognized that the increasing number of universities in Africa since ASPAU's inception had reduced the relevance of the program. In view of the continuing decline in applications, they took the decision, with USAID, to terminate the program in 1970. A final wave of only 29 fellows arrived in the fall of 1971, and the last students in the program graduated in 1975.Footnote 97

Conclusion

The history of ASPAU provides insight into the complex relationship between Africa and the United States in the Cold War context. I have highlighted this complexity by considering the training of Africans in the United States not only as an instrument of US educational diplomacy but also as a process resulting from reciprocal transatlantic dynamics. The objective was not to downplay the reality of North-South domination and the imbalance of power that manifested in Africans’ training in the US, for ASPAU was indeed constituted by asymmetrical power relations. Moreover, I showed that the American actors in the program were able to impose their views thanks to the support of their government, which was then seeking to enter Africa to counter Soviet initiatives.

On the other hand, I insisted on the capacity for action and reaction of African politicians and educators participating in the training of African elites in the United States. The history of ASPAU constitutes from this point of view a relevant case study to rethink the analytical frameworks of the Cold War from Africa. Indeed, the strategies of reappropriation and resistance that some African governments and academics adopted in reaction to the implementation of ASPAU demonstrate that the Cold War was not only a process of East-West confrontation imposed on Africa, but also a context of new opportunities for African countries. As David Engerman writes: ‘the geopolitical competition . . . provided an opportunity for Third World leaders to go aid-shopping, playing the superpowers (plus China) off against each other’.Footnote 98 As we have seen, the competition between the USSR and the United States for the training of African students was seen as beneficial by some African leaders. Their ability to obtain both ASPAU's and socialist countries’ scholarships offered African governments the opportunity to diversify their source of foreign aid, to move away from an exclusive relationship with the former colonizer, and to lend diplomatic legitimacy to their still-fragile power.Footnote 99 The participation of African leaders in ASPAU was in this respect an example of what Jocelyn Alexander, JoAnn McGregor, and Blessing-Miles Tendi call the ‘African uses of the Cold War’.Footnote 100 Although they were effectively and inevitably caught up in the power struggles of the Cold War competition, these leaders still had room to ‘use’ the competing involvement of the great powers for their own interests.

The ability of African actors to influence the implementation of ASPAU shows that the process of building independent African States, far from being subject only to the legacies of the colonial era and the injunctions of the new American and Soviet superpowers, was also the result of negotiations and oppositions. Some African governments negotiated their participation by seeking to impose their conditions, as in Senegal and Ghana. Others sought to put ASPAU at the benefit of their own vision of education, as in Tanzania. African academics, for their part, upon realizing that ASPAU could jeopardize the development of their universities, tried, and often succeeded, to keep their students at home. Ultimately, the attitude of African actors involved in ASPAU finally brought to light the original paradox of the program, and that eventually prompted its ending: by seeking to contribute to the educational development of Africa, ASPAU also participated in its impoverishment by depriving African nations of some their best young minds.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge Jeffrey Ahlman, Eric Burton, and Constantin Katsakioris for their valuable advice during my research and Ludovic Tournès, Thomas David and Yi-Tang Lin for their comments on an early draft of this article. Finally, I warmly thank the anonymous reviewers and editors of this journal for their pertinent remarks.