When the British took over Asante in 1896, there was, surprisingly, no fighting: Asantehene Prempe I surrendered and was subsequently exiled by the British. The asantehene's decision to submit is puzzling, given that Asante had engaged in at least five major confrontations with the British before 1896. Asante was also a deeply militaristic state which fiercely guarded its independence. Why did Prempe yield? Why did it take until 1900 for Asante to offer military resistance to British rule?Footnote 1 Joseph Adjaye argues persuasively that Prempe tried, albeit unsuccessfully, to use diplomacy to avert war and still maintain Asante's independence.Footnote 2 Emmanuel Akyeampong, Ivor Wilks, and Tom McCaskie, in complementary works which examine Asante's transition from the precolonial era to the colonial, have supported Adjaye's assertion.Footnote 3

This paper offers another perspective on our understanding of how colonial rule was imposed on Asante. Its central argument is that Asante's independence was contingent on having a strong army. The state formed armies to meet threats to its power largely by coercing its subjects into military service. It did this by activating Asante society's ‘social contract’, which stipulated as law that Asantes owed an obligation of military service to their state. In return, the state was required to protect Asantes, offer astute leadership, and engage in tactful diplomacy with other states. Through a series of state-induced catastrophic events between 1874 and 1888 — such as defeat in the 1874 Sagrenti War and the subsequent civil wars — the state undermined the social contract which, in turn, weakened its own ability to demand military service from Asantes.Footnote 4

In order to establish this position, the first section of the paper discusses what the literature on nineteenth-century Asante identifies as the ‘Asante state’. It also systematically defines what, in Asante's worldview, was considered to be a ‘social contract’. The second section points out that, during the Sagrenti War, Asante fighting men resisted the state's power due to aberrations in this social contract. As stated above, Asante formed its army by coercing its subjects into military service. However, it veiled this coercion as consent using specific norms and traditions inherent in the Asante social order that legitimized its use of coercive power. During the Sagrenti War, the state subverted these same traditions and thereby opened the way for the fighting men to act contrary to its directives. The third section argues that, although the actions of the state and its agents during the Sagrenti War created dysfunction in the army and should have led to a collapse of the Asante war effort, they still managed to keep the fighting men in action — especially for two decisive battles at Amoafo and Odaso — by exploiting Asante society's ‘mechanisms of coercion’. These were norms and beliefs collectively held by Asantes through which the state maintained its power over the army. The paper concludes that between 1874 and 1896 the state's misrule incapacitated the mechanisms of coercion. Meanwhile, without the collective agency of Asantes the state could not form and maintain large armies for defense. This situation therefore left it militarily weak and incapable of challenging the British invasion with a military force to preserve its independence.

State, subjects, and a social contract

During times of war, nineteenth-century Asante pressed its subjects into ad hoc armies to counter internal and external threats. But it cannot be taken for granted that all Asantes willingly joined state-sanctioned war efforts just because they were Asantes. This raises important questions. For instance, how was the state constituted, and what sort of relationship, concerning resistance to its control, existed between it and the fighting men? Asante historiography offers two perspectives. The first, what could be called the state-centric perspective, sheds light on the constitution of the state. The second, the social order perspective, allows one to comprehend why some fighting men fought for the state whereas others resisted its power. It also enables one to appreciate the different measures the state employed to curb resistance.

The state-centric perspective originates from Kwame Arhin's pioneering 1967 article ‘The structure of greater Ashanti’, where he conceptualizes the state as the combination of polities within the geographical confines of ‘Asante-proper’ — that is, Kumase, Mampon, Dwaben, etc.Footnote 5 This state body, the union of these polities, was a council known as the Asantemanhyiamu or, in his words, ‘the Kotoko Council, the ruling or executive body of the nation’, which decided issues of national significance such as diplomacy and war.Footnote 6 Based on this view, Arhin advances three distinctions in Asante: territories which formed Asante-proper with Kumase as their head (the state), Akan polities defeated or coerced into subjugation and which shared close cultural and linguistic ties with Asante-proper (the provinces), and states outside these two regions which, in most cases, shared neither cultural nor linguistic ties with Asante-proper and were geographically too distant to be fully integrated into Asante's political mechanism, but were dependent on Asante trade or liable to an invasion if they rebelled (protectorates and tributaries). Essentially, Arhin's conception of Asante considers only the macro relationships which existed between Asante-proper and the outside polities. As a result, he only examines resistance to state power from outside Asante. Though he mentions that ‘internal strife’ existed inside the Asantemanhyiamu, it is where he ends his discussion of internal Asante resistance to the state.Footnote 7

The state-centric perspective was cemented into the historiography by Ivor Wilks's seminal 1975 work Asante in the Nineteenth Century. Wilks offers a conception of the state that is similar to — but not the same as — Arhin's. He acknowledges Asante's three geographical distinctions, although he classifies them as metropolitan, inner, and outer territories. In his work, however, even though the states in the metropolitan area rank higher than those in the inner and outer regions, the state is not their union (the Asantemanhyiamu) as Arhin suggests. Rather, the asantehene and his officeholders in Kumase who imposed their power on the other Asante polities are what he considers as the state.Footnote 8 Based on this, he suggests that the Asantemanhyiamu was more judicial than legislative, certainly not as executive as Arhin describes, and therefore a tool the asantehene used to entrench his powers.Footnote 9

Besides its clarification of the component parts of the Asante state structure, there are other notable points about the state-centric perspective. First, it presents the state's power as coercion applied through institutionalized social norms and traditions; the state only used direct force when subtle coercion failed.Footnote 10 Second, it focuses on the state's macropolitical structures and their interrelations, allowing very little, if any, room for studying individuals’ reactions to state power. Thus, although the perspective clearly indicates who constituted the state, it is unable to determine fully what sort of relationship the state had with individuals. As a result, it is incapable of answering the question of why and how the fighting men accepted or resisted the state's power.

Whereas the state-centric perspective presents a top-down approach that suggests power resided in and flowed from only the upper levels of Asante society, the social order perspective completely rejects this premise. The idea that power was the sole prerogative of the state has been severally critiqued under this perspective, especially by McCaskie in State and Society in Pre-colonial Asante, as well as by Emmanuel Akyeampong and Pashington Obeng in their article ‘Spirituality, gender, and power in Asante history’.Footnote 11 Although McCaskie, like Arhin and Wilks, is mainly concerned with the Asante state, he extends the discussion beyond a singular focus on the state. He advances the argument that it is simply inadequate to probe the political structures which controlled power in Asante without examining the kingdom's social order — the origin of both the state and its power and that upon which the state came to reside at its height.Footnote 12 This is a more plausible approach for exploring why the fighting men fought for the state, why others resisted, and what measures the state employed to prevent resistance from destabilizing its military structures.

Coercion, McCaskie argues, was not the definitive tool of state power preservation because ‘the state simply lacked the infrastructure and technology to command society solely by coercive force.’Footnote 13 He also suggests that, commonsensically, the ruled always outnumbered the rulers and could have overthrown the state through their sheer numbers if they wanted to.Footnote 14 In effect,

coercive capacity . . . was subject to very clear and obvious limitations. It was in and of itself a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the maintenance of the state's authority. The state's ability to coerce society ultimately depended upon society being structurally complicit in, or consenting to, its subjection to the state's interventions. But the bases of consent were not an agenda of neutral agreements. They had to be identified by the state, and then ideologically structured and articulated to serve the discrete objects of power.Footnote 15

The key point McCaskie makes, based on his careful adoption of Gramsci's concept of hegemony grounded in consent, is that the state obtained the consent of the ruled through the ‘institutionalized practices’ of Asante society.Footnote 16 These included factors like belief and religion, knowledge, custom, habit, and patterns of thought.

I extend McCaskie's argument by contending that it was through these same ‘institutionalized practices of society’ that the ruled identified and reacted to the state's abuse of their consent. Asante did not have a written — or perhaps ‘formalized’ — constitution and was rather governed through the same institutionalized practices of society he alludes to. Law existed largely in the form of a social contract between the state and its subjects. As stipulated in this contract, the state had certain obligations, such as protecting Asantes and conducting skillful diplomacy with external entities. In exchange, Asantes offered it their consent to be ruled. When the state failed to meet its responsibilities, its subjects could legitimately dispute its authority. Meanwhile, when subjects, too, failed to meet their part of the contract, such as paying taxes and making themselves available for military service, the state could exact due punishment. The principles underlying this social-contractual relationship are aptly captured by Akyeampong and Obeng in their study of power in Asante society. ‘Power’, they explain, ‘does not exist in a vacuum; it is interactive. Its nature and exercise are best understood by taking cognizance of the rights, obligations, and expectations of the rulers and the ruled.’Footnote 17 The rights and obligations of Asantes were well known through memory, belief, custom, and other forms of institutionalized practice. Therefore, the boundaries of state power could be identified. Furthermore, under certain circumstances, when the state breached the social contract its authority could be rejected.Footnote 18

The terms of Asante's social contract were defined under two broad legal categories which McCaskie explores in State and Society: amanbrɛ and amanmmu.Footnote 19 Amanbrɛ were laws the state created to police the conduct of Asantes and which it constantly checked and reformed to regulate the fluid and dynamic everyday Asante social and political terrain. They were, thus, ‘jural custom that might be changed or adjusted by legislation’.Footnote 20 Amanmmu, on the other hand, were immovable and inviolable natural laws. They were ‘immemorial custom that ordered’ Asante society, held the social fabric together, and prevented anarchy or collapse.Footnote 21

Amanbrɛ were created, enforced, and punished by the state. But amanmmu were infused into society at the beginning of creation by Onyame, God himself. Admittedly, the state was largely free from the restrictions of amanbrɛ since it created and reengineered them to suit its needs. But the state was not immune to amanmmu. However, the state, as the supreme earthly agent of Onyame, punished infringements of both. Naturally, the akomfo (priests), as mouthpieces of Onyame, should have had more power. But, as McCaskie rightly points out, the state controlled them through constant surveillance, various stratagems designed to trick them into error, ridicule, and disgrace, and even purges.Footnote 22 Thus, if even the akomfo were subservient, who else was powerful enough to hold the state accountable when it flouted its own or Onyame's laws? What ensured that it did not turn predatory, and what repercussions followed whenever it did?

There were checks and balances to ensure that the state did not neglect its duties or abuse its power, such as the asantehemaa (queen mother), nsafohene (political officeholders in the Asante capital Kumase), and amanhene (rulers of the other Asante states). These were the state's primary advisers who not only selected the asantehene but could also remove him from power. They often acted simultaneously as state agents and only resisted when their own power was threatened.Footnote 23 At other times, the state deliberately weakened them.Footnote 24 Thus, they were joined to it based on converging interests. These interests were sometimes at the expense of Asantes and therefore led to conflicts between the state and its subjects. Such conflicts usually hinged on divergent state-subject interpretations of infractions of amanbrɛ and amanmmu. The ‘lawful’ was, nevertheless, determined in the state's courts based on its interpretations of the law.

However, the condition of being right before the law was subject to the functioning of power in state-subject relations. Power here was simply the ability to impose one's will on others.Footnote 25 The state inevitably had the power to punish Asantes for breaking the law. It also determined the range and depth of punishment. Conversely, individuals invariably had no power with which to hold the state accountable or impose on it their legal rights. The Asante state was judge and jury: persons found guilty by the state submitted or fled. Asante subjects’ limited options in cases of conflict with the state did not universally validate the state's interpretations of the law. Rather, they point largely to individuals’ lack of power with which to enforce their own ‘legal truths’.

Such unequal levels of power in state-subject relations can be seen in Kwasi Gyani's well-documented conflict with the state. In 1862, he and about eighty supporters fled southwards from Asante into the protection of the British. He was accused of withholding gold nuggets that according to law belonged to the asantehene. In his defense, Gyani stated that ‘he [was] a man of property [sikani], and declare[d] that the King [Kwaku Dua Panin] desire[d] only to entrap him, take his head, and afterwards possession of his property.’Footnote 26 Gyani's keeping of the nuggets, if true, was certainly illegal within the ambit of amanbrɛ (because the state's laws deemed keeping gold nuggets unlawful). But a possibility remains that his flight from Asante was justifiable according to amanmmu. If his accusation by the state was truly a ploy to entrap him, find him guilty, kill him, and appropriate his wealth, then it constituted a violation of the naturally defined boundaries between the state and the lives — and wealth — of Asantes.Footnote 27 It follows that Gyani's reaction could possibly have been elicited from the state's own breach of Asante law and that his escape from Asante was an act of self-preservation borne out of an implicit awareness of his powerlessness.Footnote 28 To successfully challenge the Asante state, one had to wield not only a legally-justifiable position but also greater power.Footnote 29 Indeed the state's power was successfully challenged from outside the state structure only when the challengers had greater power (in their numbers) and were right before the law (due to the moral strength of their cause) — that is, when commoners overthrew Asantehene Mensa Bonsu in 1883 for his tyranny and oppressive regime of taxation.Footnote 30

Akyeampong and Obeng confirm these observations about the social contract, albeit from a different angle. They argue that the state's power was under constant challenge from a web of actors within and outside of Asante. Upholding Asante's wellbeing was what safeguarded the state's power. But whenever the state placed Asante in danger by its actions or inactions, its power was liable to justifiable internal assault. They provide two case studies. In 1818–19, Asantehene Osei Bonsu went to war with Gyaman, a vassal of Asante. Traditions of the war indicate that Asante barely secured victory, but at a great cost in lives. A palace coup occurred, led by the asantehene's sister, Asantehemaa Adoma Akosua. It is difficult to gauge her exact motivations, but one strong suspicion is that she believed the asantehene had endangered Asante by embarking on that difficult war. The second case study is from the late 1870s, when Asante was in a period of state-induced turmoil caused by events such as the 1874 defeat by the British, Asantehene Kofi Kakari's destoolment, the Kumase-Dwaben civil war, and Asantehene Mensa Bonsu's despotic rule. An antiwitchcraft movement, Domankama, emerged that believed witchcraft was ubiquitous, malevolent, and the cause of Asante's problems. The movement promised order and stability and initially received the state's endorsement. Domankama was destroyed by the state when it attempted to assassinate the asantehene. While it cannot be ascertained whether it had political ambitions from the outset, the movement undeniably set itself up as a more stable political alternative to the state. Both rebellions failed and were vengefully purged. Yet their emergence was due to the state's own weak and unsatisfactory rule, which had placed Asante in danger — from the state itself and from other internal and external powers.Footnote 31 Regardless, while the challengers may have been legally justified to oppose the state's authority, they nonetheless had no power with which to prevail.

Although collective action to successfully hold the state accountable was improbable — but not impossible — possibilities remained for individuals to hold the state accountable through means such as refusal to join the army. It was rebellion, but subtle and nuanced. Asante's social contract covered not just social and political decisions, but military actions as well. According to the contract, the state had certain obligations such as offering astute leadership, providing resources for prosecuting wars, and conducting skillful diplomacy with external entities. The state's failure to fulfil these obligations owed to its fighting men during the Sagrenti War meant they could resist its power through dissent, desertion, and even outright rebellion — opportunities some took and which therefore commenced the gradual undermining of Asante's military structures.Footnote 32

Asante's social contract, the army, and resistance to state power

In 1872, the Dutch decided to sell their Gold Coast possessions to the British. The most prominent of these was the Elmina castle, which stood on ground claimed by the asantehenes. Elmina was also Asante's principal coastal ally. Owing to Elmina's importance and Asante's unresolved conflicts with the British from the 1860s, Asante resisted the proposed sale. Failing to prevent this, Asante mobilized and invaded the coast in December 1872 to seize control of the castle.Footnote 33 A series of victories between February and July 1873 allowed the Asante army to entrench itself in the British protectorate. In October, Sir Garnet Wolseley and fresh troops arrived from Britain to decisively turn the war against Asante, and the Asante army was compelled to withdraw from the coast. Further reinforcements came from Britain, and in January 1874 a British counterinvasion of Asante followed. On 31 January, the Battle of Amoafo ended with a British victory. Another battle took place at Odaso two days later but could not block the British advance to Kumase. After the British captured and burned Kumase on 5 February 1874, Asante was forced to enter into the Treaty of Fomena which, among other things, imposed a war indemnity of 50,000 ounces of gold and confirmed Asante's loss of control over all provinces south of the Pra River.

In Asante militarism, the army's success or failure depended largely on the quality of its leaders. Judging by the disastrous outcome of the Sagrenti War, clearly the 1874 Asante army had leadership shortcomings. Asante traditions present then-asantehene Kofi Kakari as one who squandered state wealth on women and his personal favorites — funds that his predecessor Asantehene Kwaku Dua assiduously accumulated.Footnote 34 Due to Kofi Kakari's profligacy, he was unable to adequately stock up the vital resources needed to prosecute the war. He did not personally oversee the campaign, but rather gave command to the chief of Bantama, Amankwatia III. However, Amankwatia was an inebriate.Footnote 35 Alcoholism was loathed in Asante, even among commoners.Footnote 36 An alcoholic chief was detested. Thus, perhaps the prudent military decision would have been for Kofi Kakari to have appointed Gyaasewahene Adu Bofour, a distinguished general who doubled as his treasurer, as leader of the army. In actual fact, Adu Bofour was the commander of the army which had just returned from the relatively successful Krepe campaign. In another scenario, Kwabena Dwomo, who as chief of Mampon was second in rank only to the asantehene, could have been made leader of the army.Footnote 37

Amankwatia's leadership lowered the army's morale, as illustrated by several observations of dysfunction in its operations. First, his officers, the general body of fighting men, and the administration in Kumase constantly questioned his decisions.Footnote 38 Second, when he intercepted and responded to British correspondence meant for the asantehene and initiated attacks on their positions, Kofi Kakari accused him of insubordination.Footnote 39 Furthermore, the British nearly captured him when they launched a surprise attack on the Asante camp. Amankwatia sent the main army ahead on their retreat while he stayed behind to indulge in drinking. Because of this incident he lost his stools and regalia, a serious taboo in Asante.Footnote 40 These occurrences made the fighting men resent his leadership.Footnote 41 Some of his captains even disobeyed his direct commands.Footnote 42

Asante's collective military psychology was central to how fighting men formed favorable or adverse perceptions of military campaigns. Asante's military psychology is embodied by the national emblem, the porcupine — Asante Kotoko. The army, itself a symbol of the state in action, is represented by the porcupine while the fighting man is, metaphorically, its quill.Footnote 43 Attached to the porcupine, the quill lives, but once fired, it dies. Simply put, every man was expendable. Notwithstanding, porcupines often tend to avoid attackers and do not shoot their quills unless provoked. The same relates to the Asante state in the sense that, more often than not, it preferred diplomacy to war.Footnote 44 Furthermore, like the quills of the porcupine, fighting men expected military leaders to exercise prudence before expending their lives. Therefore, it is possible the fighting men judged the war to be a reckless waste of their lives, as evidenced by Kofi Kakari's absence on the battlefield, his improvident use of state resources, and Amakwatia's alcoholism.

Basel missionaries Friedrich Ramseyer and Johannes Kuhne were Asante hostages during the war. Their account of the army's retreat from the coast reveals that some of the fighting men pointedly said: ‘Even if the king [sends] us forward again, we will not go unless he [accompanies us]; we are sick of it.’Footnote 45 These words were considered treasonous during the war and had serious implications for those who uttered them. For the men to express such sentiments not only boldly, but publicly, is telling of the impression the general body of fighting men had of the campaign. This was also an indictment of Asantehene Kofi Kakari's leadership. It is also noteworthy that the army retreated despite his orders to stay camped in the British protectorate.Footnote 46 It will be seen in the next section that the army's retreat constituted a breach of Asante's rules concerning warfare, not just because it acted against the asantehene's commands, but because it fled from the enemy.Footnote 47

Another factor to consider is the provisions made available for the fighting men. As already noted, the asantehene did not procure adequate stocks for the campaign because he could not afford them. Thus, a British medical officer, Deputy Surgeon-General Anthony Home, noted that the Asante army possibly received food provisions from Kumase.Footnote 48 Despite these supplies, he added that ‘the Ashantis foraged for plantains, yams, Indian corn, and [cassava], and gathered the gigantic snails found in the forest.’Footnote 49 He also mentioned, concerning the deserted Asante camps, that ‘the kind of food used in the camp showed that the followers at least were pressed by famine.’Footnote 50 A correspondent for The British Medical Journal confirmed Home's observations:

It is an undoubted fact that small pox, dysentery, bronchitis, and starvation have here been making sad ravages [among the Asante]. . . . The dearth of proper food, and [the] consequent necessity of falling back upon unripe plantains, bananas, pineapples, pawpaws, and the wild or bitter yam are, no doubt, the principal causes of the dysenteric attacks from which they suffer. . . . The odour and nature of the faecal accumulations which cover their camps sufficiently indicate the prevalence of this affliction amongst them.Footnote 51

The unconventional sources of food supply the men relied on meant they were prone to disease, which resulted in the deaths of many.

It has been argued so far that Asante society was governed by a social contract which conferred rights on, and at the same time demanded responsibilities from, both state and subjects. The state's responsibilities included protecting Asantes, accumulating resources for future wars, and providing astute leadership. The ruled had reciprocal responsibilities such as presenting themselves for military duties and paying taxes. However, the state failed to honor the social contract during the Sagrenti War. Kofi Kakari and Amankwatia both offered uninspiring leadership, and the army lacked adequate resources for prosecuting the war. Nonetheless, the fighting men to a large extent held up their end of the contract. Various sources indicate that the Asante army which initially invaded the British protectorate in December 1872 was a large one, implying that Asantes joined the campaign as required.Footnote 52 It was also seen that some of the fighting men expressed their contempt for the war through dissent and refusal to follow commands. Surprisingly, British accounts of the two decisive battles which all but concluded the Sagrenti War, Amoafo and Odaso, suggest that they faced fiercer opposition from Asante than previously.Footnote 53 What caused this sudden change in Asante attitudes towards the war? How was the state able to get the men to take to the field again when, from all indications, they were weary of fighting?

The ‘institutionalized practices’ of Asante society and warfare

Asante fighting men obtained almost no material benefits from military campaigns. The asantehene, Arhin contends, ‘had a third share in loot and a greater share when he fought in person; and the remainder was divided between the leaders of the army and the men’.Footnote 54 Mineral rights, tribute, and slaves — the main proceeds from war on the Gold Coast — were the preserve of the chiefs. The common soldier could only profit from wars by ‘hiding movable loot’ or ‘surreptitiously selling slaves on the long coastal stretch of the Gold Coast’.Footnote 55 Why did the fighting men continue to fight Asante's wars even though they gained very little? During the Sagrenti War specifically, why did Asante fighting men regroup to fight the British — and to the death as many did — although they were disillusioned?

The Asante state, as noted above, extracted compliance to its directives using both coercion and consent. This section examines this process within a specific context: warfare. It is argued that the state used certain Asante traditions — generally referring to the previously noted ‘institutionalized practices of society’ — as ‘mechanisms of coercion’ to control its fighting men and prevent their mutiny and desertion during war. Fundamentally, the factors discussed here are the instruments with which the state raised armies to counter military threats to its power. Each instrument is treated separately, after which the discussion is tied together with certain conclusions.

The first instrument is the oaths (ntam) that bound Asante chiefs and fighting men to the state. Chiefs swore several times that they would never flee from war. During their enstoolment, they swore to their subjects that they would protect them. They then swore to the asantehene that, barring sickness, they would never fail to respond to his call to arms. They reaffirmed fealty at festivals such as the Odwira and Adae. In addition, before any war, they swore to the asantehene to follow his command and never retreat until they had achieved the war's objectives.Footnote 56

Asante fighting men, through their chiefs, were bound to these ‘war oaths’. Asantes held oaths sacred and believed that breaching them displeased the gods and ancestors, who sanctioned oath breaking with misfortune, disease, and death. In addition, there were other penalties the state itself had installed to augment the oaths.Footnote 57 These mainly took the form of social sanctions against men who avoided war. Fleeing from battle — or generally evading military service — was the most disgraceful act a man could commit. R. S. Rattray, head of the British colonial government's Anthropological Department of Asante, captured the following in his 1929 social-anthropological study of Asante:

The punishment for cowardice in the presence of the enemy was generally death, but if commuted for a money payment, the man was dressed in woman's waist-beads (tɔma), his hair dressed in the manner called atiremmusɛm, his eyebrows were shaved off (kwasea-nkɔme), and any man was at liberty to seduce the coward's wife without the husband being able to claim adultery damages.Footnote 58

Asante traditions generally suggest that one who dodged conscription lost his status as a man along with any accompanying social benefits.

Arhin presents a more comprehensive view. He argues that the state's valorization of certain qualities is shown in the rewards and punishments it ascribed to their expression or non-expression. For instance, the state honored bravery in defense of Asante by ‘elevating certain Asante as folk heroes and according their descendants with unique privileges’, such as exemptions from capital punishment.Footnote 59 The state's rewards could also be material, such as land and plunder. Conversely, to punish and deter, it licensed women to ridicule cowards with songs. In certain cases, cowards were executed. He further notes that all men above the age of eighteen had to own a gun. One without a gun was not permitted to marry.Footnote 60 The operation of the ‘war oaths’ pointed to the depth of Asante's militaristic statehood: through institutions and ceremonies largely unrelated to the business of war, like marriage and festivals, the state reminded its subjects that their ultimate purpose in life was its expansion, largely through warfare.

The state likewise used Asante beliefs about suicide to compel military service. Asante cosmology comprised three planes that existed concurrently: the worlds of the unborn, the living, and the ancestors and gods.Footnote 61 Therefore, certain rites and rituals were performed before a person could move successfully from one plane to another. The transition from the living to the dead involved death rites and rituals that conferred ancestorhood on the deceased, who then assumed a position slightly lower than a god.Footnote 62 Thus, death on the battlefield represented a journey from this world to a better one, and ancestorhood — the most desirable of Asante aspirations — was the reward for bravery. However, not all dead became ancestors. Among such were those who fled from battle. Arhin notes that men who avoided military service were given the ignominious title kosa-ankomi (battle-dodger) and driven to suicide through ridicule.Footnote 63 It is likely this title was popular usage that the state appropriated for its own ends.

The third instrument the state used to obtain the consent of Asante fighting men was Asante's religious beliefs and practices. Before sending the army out to war, the asantehene consulted the gods and ancestors. Victory or defeat was confirmed.Footnote 64 Since these rituals were public, they served as assurances for the men that Asante's cause was just. Obtaining the consent of the gods and ancestors in this manner was important for reasons that will be stated later. At the height of the Sagrenti War, Asantehene Kofi Kakari consulted Muslim clerics from Asante's northern provinces to augment these rituals as protection for the men.Footnote 65 However, these clerics, perhaps rightly anticipating Asante's impossible situation, did not help.

Asante fighting men were further protected by mmomomme. Mmomomme was, according to Akyeampong and Obeng, a

distinctly female form of spiritual warfare. When Asante troops were at war, Asante women in the villages would perform daily ritual chants until the troops returned, processing in partial nudity from one end of the village to the other. This ritual protected the soldiers at war, and sometimes involved women pounding empty mortars with pestles as a form of spiritual torture of Asante's enemies.Footnote 66

Ramseyer and Kuhne recorded several times that women in Kumase performed mmomomme, especially when bad news filtered in from the warfront.Footnote 67 Women in other Asante states undoubtedly performed similar rituals. Despite all these, Asante's dire situation was apparent when a rain storm, rare in the dry season, knocked down six houses in the royal compound, and the kum tree planted in Kumase by Komfo Anokye fell.Footnote 68

Feminine rituals like mmomomme indicate that Asante's social contract had diverse gendered implications for Asantes, especially during warfare. Male contributions to Asante's military campaigns centered mainly on fighting. Women, in comparison, prevented and opposed unjustifiable wars, maintained the homes and farms while the men were away, mourned and actively participated in the rites of passage for the fallen, and, importantly, procreated Asante's armies. As Akyeampong and Obeng succinctly state, Asante women were ‘counsellors, social critics, givers and defenders of life, and guardians of the body politic’.Footnote 69 The context of the highly nuanced relationship between Asante women and the social contract certainly warrants further commentary but is beyond the scope of the current paper.Footnote 70

Besides rituals for soliciting protection from the gods and ancestors, Asantes also designated physical objects like the bones of certain animals and fragments of Koranic verses as spiritual fortifications for personal protection (nsuman).Footnote 71 They were usually encased in leather pouches and metal boxes. The nsuman were a powerful boost to the morale of Asante fighting men. They repelled the bullets of Asante's enemies.Footnote 72 They also had the capacity to instill fear and confusion into the minds of opponents. Concerning these attributes of the nsuman, Thomas Bowdich, a British visitor to Asante in 1817, made an interesting observation. He remarked that

the most surprising superstition of the Ashantee, is their confidence in the fetishes and saphies [a type of talisman indigenous to West Africa] they purchase so extravagantly from the Moors, believing firmly that they make them invulnerable and invincible in war, paralyse the hand of the enemy, shiver their weapons, [and] divert the course of balls . . . . Several of the Ashantee captains offered seriously to let us fire at them; in short, their confidence in these fetishes is almost as incredible, as the despondency and panic imposed on their southern and western enemies by the recollection of them: they impel the Ashantees, fearless and headlong, to the most daring enterprises, they dispirit their adversaries, almost to the neglect of an interposition of fortune in their favour. The Ashantees believe that the constant prayers of the Moors, who have persuaded them that they converse with the Deity, invigorate themselves, and gradually waste the spirit and strength of their enemies.Footnote 73

From this, it is apparent that Asante fighting men greatly believed in the nsuman. However, it seems the nsuman were effective only when pre-knowledge of their efficacy existed in the psyche of the enemy. Take, for example, the description of George Henty, correspondent for the London newspaper The Standard, who found Asante nsuman on the march to Kumase:

At one place a fetish was placed in the middle of the road, with a wooden gun and several wooden daggers all pointing towards us. . . . [E]vidently a hint of what we were to expect if we went on. . . . Other fetishes of a more common kind were to be met at every step — lines of worsted and cotton stretched across the road, rags hung upon bushes.Footnote 74

He concluded that rather than scare them, the nsuman ‘fully authorized us in expecting at least one day's hard fighting before we entered Coomassie’.Footnote 75 But were the nsuman as useless as Henty and the rest of the British army thought them to be? Perhaps not.

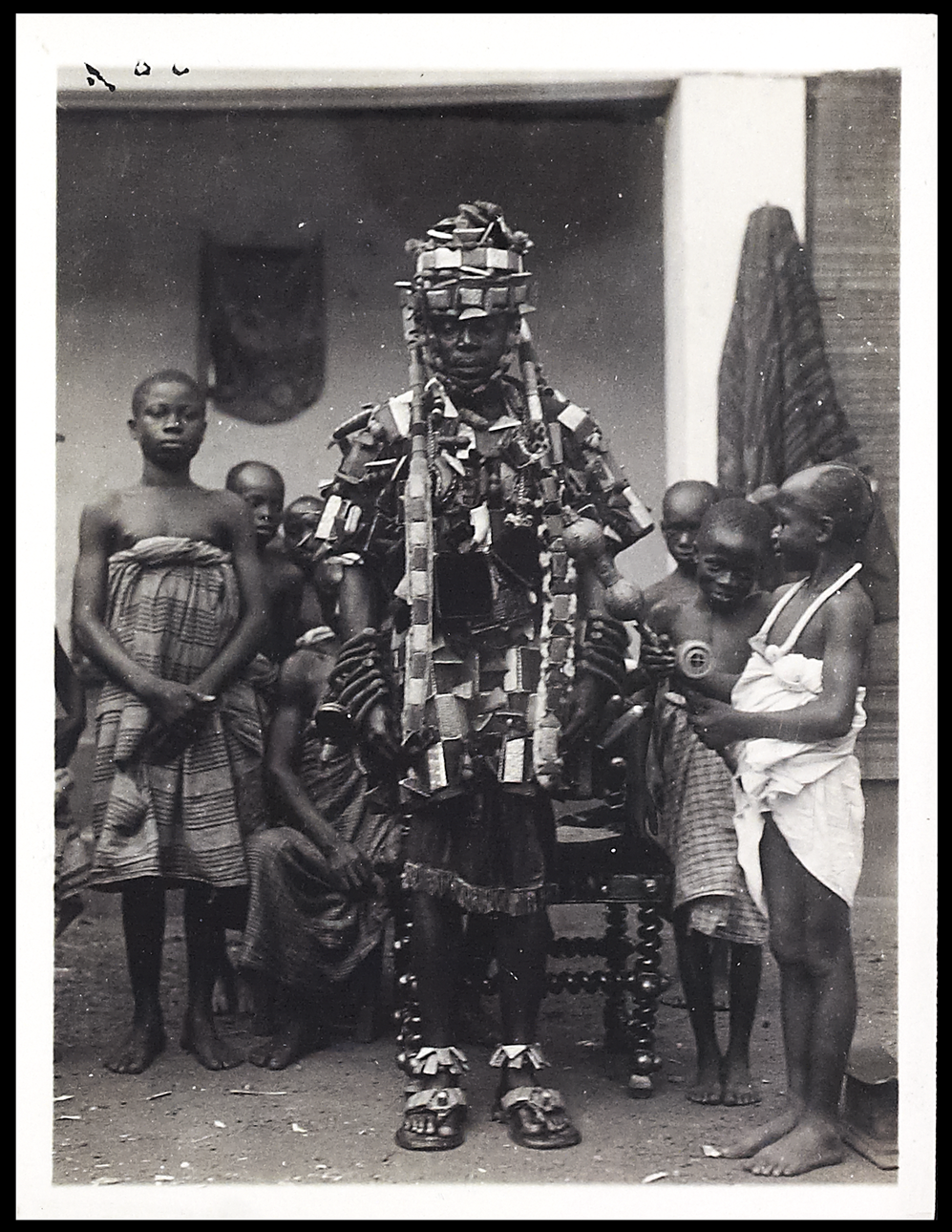

Consider the batakari, a war dress woven out of cotton, studded with nsuman of different shapes and sizes, and valued for its defensive properties. Its ability to repel bullets was probably not because of spiritual powers as the Asante and their opponents thought, but rather the material it was made from. As Bantamahene Osei Bonsu's picture below shows, batakari were covered in leather pouches and metal cases containing nsuman. This presented a dense, heavy, and seemingly impenetrable garment.Footnote 76 However, what truly made the batakari — and, generally, the nsuman — appear potent was how Gold Coast armies used guns. First, muskets were fired from the hip, not the shoulder, which therefore minimized accuracy. Second, the guns were overloaded with slugs and gunpowder, which sometimes caused their barrels to explode. Finally, they were shot from long distances.Footnote 77 The guns were simply ineffective: slugs bounced off or missed altogether. Burst barrels and impenetrable bodies led all sides to one conclusion — the potency of Asante gun-repelling nsuman — hence the captains’ ‘serious invitation’ to Bowdich in 1817.Footnote 78

Figure 1. Bantamahene Osei Bonsu in his batakari.

Source: Royal Anthropological Institute Photo Collection, 300.445-04-017. ‘The Chief of Bantama with a war-dress and head-dress covered with charms’. Photographed by Robert Sutherland Rattray, c. 1927. © RAI. Reproduced by permission from the Royal Anthropological Institute.

It is easy to assume, then, that the British won the Sagrenti War mainly through possession of superior weapons, and that, in contrast, the Asante lost the war due to their inferior guns. Although such a perspective may be true, it provides only a partial explanation. A fuller account must also address the psychology of the fighting men. Asante men had witnessed over a century's worth of slugs bouncing off them. They had little reason to believe the British army of 1874 would present a different challenge. What, in fact, changed during the Sagrenti War was that, unlike previous armies, the 1874 British army possessed Snider rifles. These could be loaded faster, were more accurate, and offered more penetrating power than earlier guns. The Asante themselves testified to this: ‘The white men have guns which hit five Ashantees at once.’Footnote 79 Both armies also fought within relatively close ranges of each other. These two factors, coupled with the fact that the nsuman did not have the desired effects on the British soldiers, therefore reduced any advantages the Asante army had.Footnote 80

But how exactly did Asante's religious beliefs help the state regulate its fighting men? The fighting men believed they were embarking on a just campaign because of the prewar sacrifices noted above. They were, therefore, confident that the gods and ancestors would protect them. The effect was that they rarely questioned orders or doubted the efficacy of the nsuman unless they suspected that someone, usually someone from the leadership, or something, either a malevolent spirit or an act of nature, had disturbed the social and spiritual conditions that guaranteed protection.Footnote 81

Besides these subtle measures to control the fighting men, there were also undisguised instruments — what could be referred to as the ‘institutions of force’ — with which the state compelled Asantes to fight. Rattray mentions that whenever Asante faced defeat on the battlefield, the leaders were bound by oath to rally around the Golden Stool, the symbol of Asante's nationhood: ‘All members of the aristocracy were expected to lay down their lives rather than that this should fall into the hands of the enemy.’Footnote 82 The afonasoafour (sword bearers) and dompemfour (crowd pushers), small detachments composed of Asante royals, enforced this rallying call. They flogged, pushed forward, and shot those fleeing from the front. Whoever they killed was barred from the afterlife. Thus, the fighting men could only go forward since there was at least the prospect of attaining ancestorhood if they died.Footnote 83

There was also another group the state used to enforce conscription. Wilks asserts that Asante's boundaries were policed by state officials known as the nkwansrafour (customs officers and border guards).Footnote 84 In his assessment, they served as ‘agents of general political control’. Their duty, first and foremost, was checking travelers moving in and out of Asante. They could even detain strangers until the asantehene had given permission for their release. In addition, they collected tolls for the asantehene and could arrest suspected smugglers. Beyond these roles, they also enforced total conscription during crises. This was demonstrated during the Sagrenti War when news reached Asantehene Kofi Kakari that the British were heading for Kumase. Ramseyer and Kuhne recorded that

[the king] had heard from Akwamu that many European soldiers had landed at the Coast, and the governor wishing to finish the war during the dry season, had joined with the Coast tribes, and was hastening on to Coomassie. The Fantees and the white men in the centre, on one side an army from Kwau-Kodiabe, and on the other a mixed host from Akra, Akwapem, and Akem. Amankwa had thrown coals on an ant hill, and now the insects were spreading themselves in all directions. It was truly no joke this time. From Ada to Cape Coast the land swarmed with troops, especially Hausas from Lagos, and numbers of white men. As usual great weakness was manifested. Guards were dispatched in every direction to prevent the possibility of flight, and to press in all capable of bearing arms, while the king grumbled and accused Amankwa Tia.Footnote 85

From the quotation it can be seen that the developments on the coast prompted a conscription of all able-bodied men. To accomplish this, opportunities of escape from Asante territories were blocked. But by whom? Ramseyer and Kuhne said ‘guards’, but the question remains ‘Which guards?’, since there were different groups operating within Asante's state system who could be labeled as such. From Wilks's description of the state's borders, the ‘guards’ Ramseyer and Kuhne mentioned were most likely the nkwansrafour.

To come back to the central question of this section — why the fighting men continued to fight despite their opposition to the Sagrenti War — one answer is that many consented to fight at Amoafo and Odaso, but under the veiled agency of the mechanisms of coercion. From Ramseyer and Kuhne, it can also be seen that the state used the ‘institutions of force’ to compel the rest. Despite all these efforts, the British crushed Asante. Defeat sent what McCaskie describes as ‘seismic shocks’ throughout Asante which weakened the state's military confidence.Footnote 86 It also resulted in major structural transformations in state-subject relations which will be discussed next.

The dissolution of Asante's state-subject social contract

The state breached Asante's social contract through well-documented events between 1874 and 1900.Footnote 87 Not only did the state fail to fulfill its mandate of leadership and protection, it also turned predatory. In 1874 the powerful Kumase nsafohene deposed Asantehene Kofi Kakari for not just his inept leadership during the Sagrenti War, but his sacrilegious raiding of the royal mausoleum for gold. This deposition was deemed unconstitutional by the amanhene since it was done without their approval. His brother Mensa Bonsu, enstooled as asantehene in 1874, reigned tyrannically, for which he was also deposed by a commoner revolt in 1883. After Mensa Bonsu's overthrow, the nsafohene sought to enstool a new asantehene. The amanhene resisted this since it constituted a usurpation of their traditional role to oversee the selection of asantehenes. While some insisted that Kofi Kakari be reenstooled because he was deposed unconstitutionally, others resolved not to accept him since he presided over Asante's calamitous defeat by the British. There were even calls for Mensa Bonsu to be reinstalled. Kwaku Dua Kumaa, grandson and heir-apparent of Asantehene Kwaku Dua Panin, was also a contender. Armed conflict broke out between the competing sides in 1883, of which Kwaku Dua emerged victorious in 1884. He, however, succumbed to smallpox after only six weeks as asantehene. Asante degenerated into sustained violence over Prempe and Yaw Twereboanna's claims to the Golden Stool.

The civil war was murderous, internecine, and unforgiving from 1885 onwards. It was also a confrontation between the nsafohene and amanhene for control of the state. Ordinary Asantes were enveloped and conscripted by both sides to serve as foot soldiers and servants. They were mostly pawns in this bitter struggle. Asante society descended into chaos, which was only resolved when Prempe finally secured victory in 1888.Footnote 88 By then, the state's control over Asante's mechanisms of coercion had been irreversibly diluted.

Thus, when the British confronted it again in 1896, the once-powerful Asante state had little confidence in its military capabilities. It had corrupted the legal means by which it summoned fighting men from the confederate states and provinces. The institutions with which Asante enforced legal obligations were either weak or extinct. Moreover, even if Asantes had assembled, the state, having wasted its material resources during the civil war, would have found it difficult to provide the supplies required for a sustained campaign against the British.

The events of the 1900 Yaa Asantewaa War are well-known and will not be recounted here.Footnote 89 Of interest, however, is an Asante's testimony of the war, which provides ample evidence of how Asantes reacted to the state's violation of the social contract. Kwabena Osei was a resident of Adiebeba, a village near Kumase. When the chiefs called for Asantes to take up arms against the British, the following was his reaction:

I wanted nothing at all to do with the fighting. My opinion was that Chiefs had had their day and would retard Ashanti if they again got back their old position. Many people here [Adiebeba] thought as I thought. In the former days of Ashanti's power and glory Chiefs were the Final Resort, the Power Supreme and the Sacred Leader. They had the Divine Right. . . . But many Chiefs in fact were worthless. They led Ashanti into useless wars as in the Atwiriboana time [the civil wars of the 1880s] and they murdered and oppressed for no other cause but a high opinion of themselves. When the British came we rejoiced to see them laid low. They asked us to fight for them during Ya Asantiwa time [the war of 1900–1]. . . . No one listened except a few who went to Kumasi to fight the Chiefs’ war. I refused it. The Chiefs could do nothing. The days of their heedless power were over and done.Footnote 90

One might argue that the Yaa Asantewaa War was distinct from the initial British takeover and that this quotation therefore does not apply. However, the breakdown of the Asante social order after the Sagrenti War had negative effects which continued to haunt Asante lives in the twentieth century. The end of the civil war of 1883–8 and the installation of Prempe as asantehene arrested Asante's retrogression but could not undo the damage. Despite the state's best efforts, its power was not at pre-1874 levels by 1896.Footnote 91 Thus, it is possible Asantes would have reacted to any state-sanctioned military campaign against the British in the same way they did in 1900. As the quotation shows, some heeded calls to join the war effort. But unlike previous wars, many abstained.Footnote 92 Even more glaring was the chiefs’ powerlessness to compel them — equally because whatever remained of the institutions of force after the tumult of the 1880s withered away after Prempe's exile.

The changes which occurred in Asante's state-subject power dynamics after 1874 seemed innocuous, as clearly demonstrated by the literature's focus on actors, with little attention paid to the sociopolitical structures of power within which they operated.Footnote 93 Yet these changes contributed to Asantehene Prempe I and other high-ranking Kumase officeholders’ surrender and exile without recourse to military resistance of any form whatsoever. The state they embodied could not challenge the British with 80,000 men as it had done during the Sagrenti War. This was because the traditions — Asante's ‘institutionalized practices’ — that supported coerced military service were weakened, corrupted, and destroyed through the state's vacation of its social-contractual obligations to Asantes.Footnote 94 Asante's military power, which had guaranteed its independence for almost two centuries, had been broken — by the state itself.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my master's thesis supervisor at the University of Oxford, Sloan Mahone, for her encouragement. I would also like to express my sincere appreciation to Gareth Austin for sharing his insights on nineteenth-century Asante with me. My gratitude goes to Kofi Agyekum for his valuable comments on Asante Twi words and their etymology. I appreciate Kofi Takyi Asante, George Bob-Milliar, Derrick Osei-Poku, and Samuel Gyabaah for not just their extensive comments on various drafts of this paper, but also their unconditional support as well. I thank seminar participants at KNUST's Department of History and Political Studies and at the University of Ghana's Department of Sociology, ISSER, and IAS for their questions and comments which helped me to refine the thesis of this paper. I also thank Gregory Mann and the two anonymous reviewers of The Journal of African History for their very helpful comments and suggestions.