Introduction

The monumental series Dutch Sources on South Asia, which gives a comprehensive inventory of early modern Dutch documents (most of them from VOC records) pertaining to the history of South Asia, represents numerous archives across the globe. The first volume deals solely with the Nationaal Archief at The Hague, while the second deals with other archives in the Netherlands. The third volume deals with archives outside of the Netherlands. Among the archives outside of the Netherlands, the National Archives of the Republic of Indonesia (Arsip Nasional) are especially important, as they contain the records of the High Government of Batavia, which was the headquarters of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in Asia. They have a section named “Buitenland,” which contains correspondence of the Dutch with rulers outside the Dutch East Indies. The name “Buitenland” itself reflects the Batavian government's nineteenth-century view that everything outside the then Dutch East Indies was foreign, literally “outside-land.” The two Marathi letters are preserved in this section.Footnote 2

The Political Context of the Letters

One letter was sent by the Peshwa Madhavrao Narayan to the “Dutch Governor” at Nagapattinam and Pulicat, while the other was sent to the same by Narsingrao and Lingoji Bhosle, both ministers of the Thanjavur Maratha King Amarsingh. The letters reveal the extremely fluid political atmosphere of the late-eighteenth-century Coromandel Coast. Indigenous powers like the Thanjavur Maratha Kingdom, the Nawab of Arcot, the Mysorean rulers, and the Marathas from the Deccan vied with each other and with European powers such as the British and the French for the control of the rich and fertile lands near the Coromandel Coast. At the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, the French power in India was decisively defeated by the British, never again posing a serious threat to the latter. As a result, the British remained the sole European power capable of effectively exerting military power in the region. As the letters were exchanged between the Marathas and the Dutch, it would be instructive to examine the build-up of the events from 1763 until 1788 from the points of view of both the Marathas and the Dutch. Underlying broader processes include the continuous decline of the VOC and the steady ascendance of the British in late-eighteenth-century South India, the attempts of the British to gain a foothold in South India and thus their entanglement in the local politics, and the Maratha-Mysore and Anglo-Maratha conflicts.

The Marathas in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Coromandel

The Marathas had emerged as a powerful, multilayered polity in India by the eighteenth century, nominally headed by the Chhatrapati (aka the “Lord of Kshatriyas”) of Satara, while in reality comprising several independent rulers like the Peshwas, the Shinde or Scindia, the Holkars, the Gaikwads, among others. The prime minister, i.e., the Peshwa of the Satara Chhatrapati, led the confederacy from Pune, while the junior branch of the Chhatrapatis continued to rule from Kolhapur and the nearby territories. The Chhatrapatis of Satara and Kolhapur were both the descendants of Shivaji, while the Thanjavur Maratha Kingdom had been founded by Ekoji, the half-brother of Shivaji.

The Maratha Kingdom of Thanjavur was caught between the tussles of its more powerful neighbours multiple times in the eighteenth century. As early as 1728–29, Tulja Raja I, then king of Thanjavur, had requested Chhatrapati Shahu of Satara for help against the forces of Sadatullah Khan, the Nawab of Carnatic.Footnote 3 This trend continued many years thereafter and Marathas from Deccan usually sent reinforcements to help the Thanjavur Kingdom.

During the Seven Years’ War between the French and the English, both tried to establish their control over the Thanjavur Maratha Kingdom. When Muhammad Ali, the Nawab of Arcot, threatened to invade Thanjavur, George Pigot, the British governor at Madras, intervened and made the two parties sign a treaty on 12 October 1762.Footnote 4 This made the British more influential than before in the affairs of Thanjavur. The Nawab was not happy at the terms in the treaty, and was thus looking for an excuse to invade Thanjavur and exact heavy tribute from there.Footnote 5 He destroyed the dam on the Kaveri river, forbade its rebuilding, and threatened to cut off the very lifeline of the Thanjavur Kingdom in 1764, which the British again managed to prevent.

Meanwhile, Hyder Ali had risen rapidly in the Kingdom of Mysore. He invaded Thanjavur in 1769, when Tulja Raja II concluded a treaty with Hyder Ali, giving him 4,00,000 rupees and five elephants, while also receiving an assurance from the Marathas in Deccan that a Maratha army would soon come to the Carnatic.Footnote 6

As Hyder Ali was a staunch enemy of the British, the latter supported Muhammad Ali in his invasion of Thanjavur in 1771, on the pretext that Thanjavur concluded a treaty with their enemy. Thanjavur appealed to the Marathas in Deccan for help, which is reflected in a letter from Narayanrao Peshwa, addressed to his mother in 1771.Footnote 7 Before the campaign was over, the son of Muhammad Ali concluded a treaty with Thanjavur, which heavily burdened the kingdom. Tulja Raja leased off the port of Nagor and some other regions to the Dutch in lieu of cash.Footnote 8

Weary of the possible influence of other European powers and anxious to regain a stake within Thanjavur territories, the British invaded Thanjavur in 1773. They gave the Thanjavur fort to Muhammad Ali, and imprisoned King Tulja Raja II. But this meddling by the British in the Indian affairs was viewed unfavourably by the Court of Directors of the British East India Company, as a result of which Tulja Raja was released from prison and reinstated as a king in 1776.Footnote 9

During the First Anglo-Maratha War, Nana Phadnavis, the famous statesman in the Pune Court, had created a combined front of Hyder Ali, the Nizam of Hyderabad, his own masters the Peshwas of Pune, and the Nagpur Bhonsle against the British. The latter managed to break off Nagpur Bhonsle from the alliance, but were unable to win against the alliance of the remaining three. On 9 August 1780, the Barbhai Council, (made up of the twelve diplomats and generals representing the Maratha confederacy) signed a treaty with Hyder Ali, which contained a stipulation that Hyder Ali should liberate Thanjavur from the British. As a result, Hyder Ali invaded Thanjavur in 1781 but was defeated.

In 1782, the First Anglo-Maratha War ended with the Treaty of Salbai, which contained an article stipulating that Marathas should help the British in recovering their possessions lost due to Hyder Ali. This effectively annulled the 1780 treaty between the Barbhai Council and Hyder Ali, further increasing the animosity between Mysore and Marathas.

In 1787, Tulja Raja II died without a natural heir. He had meanwhile adopted a boy named Serfoji, whose claim to the throne was contested by Amarsingh, the half-brother of the late Tulja Raja II. Amarsingh corresponded with Archibald Campbell, the British governor at Madras, about this, and secured his claim over Thanjavur in 1787. The British eyed this opportunity to dominate the Thanjavur Kingdom, forced Amarsingh to accept some rather severe terms, under which he was to pay 14,00,000 rupees to the British per year, among various other similarly defined yearly payments, some of which could increase as the British saw fit.Footnote 10

Amarsingh rightly felt that the conditions were excessively severe, and as a result requested the Peshwa at Pune as well as the British at Calcutta to alter the terms so as to lessen the financial burden on Thanjavur.Footnote 11 In the process, he and his ministers also requested that the Dutch be treated with appropriate courtesy and their affairs be settled on favourable terms.

The Dutch in Late-Eighteenth-Century Coromandel

The VOC in Coromandel and Malabar, especially after 1760, acted generally defensively, concentrating on preserving their existing possessions rather than expanding, and favouring trade rather than politics. But the quick rise of the Mysorean general Hyder Ali and his wars with powers such as the British and the Marathas forced the VOC to rethink its policies for southern India. In particular, Hyder Ali seemed a suitable ally, given his sufficient military and financial means.Footnote 12 Despite the exchange of promises and some ammunition, a formal treaty was not concluded due to Batavia's stress on maintaining strict neutrality with the Indian powers.Footnote 13 The VOC lacked any state support from the Dutch Republic, precisely when it was much needed in order to thrive.Footnote 14

In 1768, Hyder Ali was rumoured to be preparing for an attack on Thanjavur because the Maratha king had conducted a treaty with Muhammad Ali. Thanjavur managed to avert the attack by sending cash and presents to Hyder.Footnote 15 Even so, as Thanjavur relied on the Dutch for protection according to a defensive treaty signed earlier, the Dutch were wary of retribution from Hyder, also because they hadn't complimented him like the French.Footnote 16 Even though Hyder actually didn't harm the Dutch factories on the Coromandel Coast at this time, the Dutch trade practically stopped, as the movement of Mysorean troops in the vicinity of factories caused a great deal of alarm in the populace.Footnote 17

The precarious balance of the shifting alliances in southern India continued till 1778, when war broke out between England and France and the threat of Hyder Ali invading the Carnatic became much more potent. As a result, the VOC mulled the possibility of treaties with the British and Muhammad Ali, with Batavia urging strict neutrality between the British and the French,Footnote 18 although a Marathi dispatch from Chennai, written in 1787, mentions that the Dutch allied with the French and caused great damage to the English.Footnote 19

During the Second Anglo-Mysore War, the Mysorean troops reached the Coromandel Coast, plundered the Dutch factory at Porto Novo on 22 July 1780, and left with the Dutch resident Topander and a considerable volume of loot. The Dutch wrote letters to Hyder Ali, requesting the release of the resident and restitution of the goods, but to no avail. In October 1780, Mysorean troops were also active near Pulicat and Sadraspatnam but didn't trouble the VOC factories there.Footnote 20

After this, Hyder Ali told the Dutch to send some “servants of distinction” to discuss important matters with him. The Dutch took time to reply to his proposals, and despite initial willingness to send a person, later on stalled the negotiations completely, because Falck, the VOC governor of Ceylon, thought Hyder to be an enemy of the VOC because he had forcefully taken some of the VOC's possessions in the Malabar.Footnote 21 Almost simultaneously came an offer from Warren Hastings of an alliance against Hyder Ali, but, despite some initial progress, an Anglo-Dutch alliance didn't materialize, as, according to several sources, the EIC administration at Madras was never sincere in pursuing such an alliance.Footnote 22

In February 1781, Mysorean troops under Lala Chubeela Ram ransacked the villages nearby Nagapatinam. All requests for restitution of damages fell on deaf ears. Hyder kept demanding huge amounts of cash, and in May 1781, was still demanding 1,00,000 rupees. The situation again abruptly changed when the news of the (fourth) Anglo-Dutch war in Europe was received by the VOC in southern India in June 1781. Hyder Ali also seemed inclined to conduct a treaty with the Dutch, which contained promises of mutual military help.Footnote 23 Despite the Dutch sending troops to help Mysoreans at Thanjavur and the latter sending troops to Nagapatinam, the British easily stormed Nagapatinam in November 1781, owing to lacklustre planning of the defence of the town. Interestingly, a Marathi dispatch dated 18 July 1781 mentions that “the Dutch of Nagor and Nagapatinam have allied with the British with their army.”Footnote 24

In view of the Anglo-Dutch war during 1780 to 1784, such an occurrence does indeed seem unlikely; however, it may also be the case that the offer of alliance with the Dutch from Warren Hastings may have had some temporary effect on a limited scale. In any case, the Marathi evidence remains tantalizing, as it goes counter to the Dutch sources, thus revealing another side of the events: the Dutch probably didn't choose to report the temporary alliance to their superiors. Another Marathi dispatch from 1787 clearly mentions that “the Dutch allied with Hyder, so the British captured Nagapatinam, Nagore, Trikanamal (Trincomalee).”Footnote 25 After this, the fortunes of the VOC in Coromandel continued to decline steadily, with rapidly deteriorating trade and a considerably smaller number of ports under them. Conditions in Europe as well as Asia contributed to this decline.

The Dutch in Coromandel addressed their concern to the Peshwa at Pune, thereby requesting to ameliorate their situation through the Thanjavur kings. The Peshwa responded in a letter addressed to the Dutch, and assured the latter that their affairs would be dealt with more favourably than before.

The Transliteration and Translation of the Letters

Both letters are addressed to the “Dutch Governor of Pralaya Kaveri (Pulicat), Nagapattan, etc.” One of the letters is from the Peshwa Madhvrao Narayan, while the other is from the ministers of the Thanjavur Maratha King Amarsingh. In what follows, the transliterations (according to the International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration, aka the IAST system) and translations of the letters will be given. Both letters are preserved with their own envelopes with seals and some text, a rather rare occurrence because once the letters were received, the envelopes were typically discarded.

Text on the envelope of letter 1:

(Seal of the Peshwa Madhavrao Narayan in red Lac)

“rājā śāhū narapati harṣanidhāna mādhavarāva nārāyaṇa mukhya pradhāna”

(Salutations to the Dutch)

sujāta asāra ajaṃ akaraṃ goraṃdora valaṃdeja baṃdara nāgapaṭaṇa pralaye kāverī vagaire yāṃsi dāmamohabbata jyādā hu

Translation:

[Seal of the Peshwa Madhavrao Narayan in red Lac]

“The prime minister Madhavrao Narayan is the receptacle of joy for Raja Shahu, ruler of men.”

[Salutations to the Dutch]

To the great and brave Dutch governor, port Nagapattan, Pralaya Kaveri (i.e., Pulicat) etc., whose love with us may endure forever.

Letter 1. (Peshwa Madhavrao Narayan to the Dutch Governor at Pulicat, Nagapattinam, etc.)

sujāta asāra ajaṃ akaraṃ valaṃdeja goraṃdora baṃdara nāgapaṭaṇa pralaye kāverī vagaire dāmamohabbata

jyādā hu da aja dila yekhalāsa mādhavarāva nārāyeṇa pradhāna suhūra sana samāna samānena mayā va alaphu tumhākaḍīla vartamāna savistare śrīmanmāhārāja rājaśrī amarasiṃga [Originally empty space, the word must be in the top portion of the letter which is not visible in the scanned images. It must be Amarsingh because he is the one who wrote to the PeshwaFootnote 26.] mahārāja yāṃnī lihile tyāvarūna avagata jāhāleta tumhī hara koṇate goṣṭīsahī aṃdeśā na karāvā āmhīṃtumhāviśaī va caṃdāvarace ṭhāṇa kāhaḍāve yāviṣaī iṃgarejāce vilāyetīsa patre lihilī yāce dākhale parabhāre tumhāṃsa yetīla va sāṃpratī phatealī yāṃnī takhta kele karitāṃ sarakāracī svārī dasarā jāliyāvarī māranilece pārapatyākaritā yeṇāra te samaī caṃdāvaracā va tumacā baṃdobasta yethāsthita pūrvīpekṣā ādhika hoīla bahuta śatrūcī pārapatye sarakārace jarabe hotīla kalāve āṇi tumacā āmacā śneha yekhalāsa asāvā yaise tumace

“rājā śāhū narapati harṣanidhāna mādhavarāva nārāyaṇa mukhya pradhāna”

(Circular Seal of the Peshwa in black ink)

bādaśāhasa lihūna pāṭaūna gharobā cāla yaise karaṇe samatāṃ samaī tumhīṃ āmace lihile mānāve āmhī tumace mānāve āṇi caṃdāvaravāle yāṃsī ākṛtrima cālāve yākaritāṃ rāmarāva yāsī pāṭavile ase sarvahī tumace manogatānurūpa hoīla kiṃvā koṃkaṇa prāṃtī muṃbaījavala revadaṃḍā yethe tumhāṃsa jāgā śnehakaḍūna koṭīsa dyāvayācī ājñā hoī viśeṣa lihiṇa kāye ase śnehācī vṛdhī asāvī jāṇi ravānā cha 27 śābāne lekhana sīmā

Translation:

To the valorous and noble Dutch governor [of] ports Nagapattan, Pralaya Kaveri [Pulicat] etc., from prime minister Madhavrao Narayan; may our love and trust for each other endure forever. The Suhur year is 1188 [i.e., 1788 CE]. The noble Sire Amarsingh Maharaja wrote in detail about the tidings from your side, from which we understood about the same. You should harbour no doubts about anything. We have sent letters to the country of the English about you and about calling off their army from Thanjavur, the confirmation of which you will receive from others. Also, currently Fateh Ali [Another name of Tipu Sultan] has ascended the throne. We will make an expedition into the South after the Festival of Dasara to contain him, and at that time, the affairs of Thanjavur and yourself would be settled even better than before. The enemies will be contained by the fear of our army; you should understand this.

“The prime minister Madhavrao Narayan is the receptacle of joy for Raja Shahu, ruler of men.”

(Circular Seal of the Peshwa in black ink)

And you should write to your Badshah [Emperor] that the friendship between ourselves and you be marked by trust and thus ensure the amity between us. Presently, we are sending Ramarao so that we both agree with each other [about the issues] and the Thanjavur King is also assured of our genuine interest. Everything will happen according to your wishes. Or, if you so wish, we will order that you get a piece of land at Revdanda in the province of Konkan, near Bombay, for a factory. What more should be written? May the friendship [between us] increase. Let it be known. Sent on 27th of the Month of Shaban. Here ends the writing [the last line is from the stamped seal next to the line before].

Text on the envelope of letter 2:

akhaṃḍita lakṣmīalaṃkṛta rājamānya rājaśrī valaṃdeja goraṃdora baṃdara pralaye kāverī yāsī praviṣṭa kīje

Translation:

Let this letter be presented to the noble lord and Dutch governor at the port Pralaya Kaveri [Pulicat], may he be forever be blessed by Lakshmi [the Hindu Goddess of wealth].

Letter 2. (Thanjavur Ministers Narsingrao and Lingoji Bhonsle to the Dutch Governor at Pulicat, Nagapattinam, etc.)

rājaśrī valaṃdeja goraṃdora baṃdara pralayekāverī

yāsī pratī

da akhaṃḍitalakṣmīalaṃkṛta rājamānya amarasiṃvha śne narasiṃgarāva bhosale va liṃgojī bhosale rāmarāma upari yethīla kuśala tā| āṣāḍha vadya 6 sā pāveto caṃbarī yethāsthita jāṇona svakīye lekhana karīta gele pāhije viśeṣa śrī tuḷajā māharājasāheba yāṃcā kāḷa jāhaliyāṃvarī śrī amarasiṃvha mahārāja yāsī paṭa āliyāvarī puṇiyāṃsa śrīmaṃta peśave yāsa vartamāna lihile hoteṃ kīṃ igarejāce baṃdivāna jāhālo ve āmace saṃsthānāmue valaṃdejācāhī phāra kharābā hoūna nāgapaṭaṇa ityādika jāūna vilāītīsa gele phirūna pralayekāverī mātra tyāṃkaḍe baṃdara soḍile āhe valaṃdeja yācā va āmacā phāra bhāūpaṇā cālata hotā yekamekāsa āsarā paraspare sakhyatva hoteṃ tyāṃta virudhta paḍūna tyācī ṭhāṇī dekhīla ghetalī tumhī abhimānī va sāṃprata baḷavaṃta pṛthvīceṃ rājya karitāṃ yaise āsūna āmhī baṃdivāna jāhalo āmhāṃbarobara kiteka sāvakārahī jāhale ātāṃhī abhimāna dharūna iṃgarajāce hatūna soḍavāve pūrvī thorale māharāja yāsa saṃvasthāna jaise cālata hote tyāpro| cālā yaisī patre śrīmaṃtāsa śrīmāhārāja yāṃnī lihilī tyāveḷesa tumacyāhī kitaka gharobyācā śnehācī vartamāna lihilī va tumace nāvī patrehī āṇavileṃ taiseca māharājasāhebāṃsa takhtācī vaśreṃ pāṭavilī puḍhe dasarā jāhaliyāvarī ṭipūvarī svārī yeṇāra tyāsamahī saṃvasthānacā baṃdobasta karūna deto mhaṇūna va valaṃdejācāhī baṃdobasta pūrvīpekṣāhī ādhika hoye yaise vilāyetīsa patra baṃgālavāle yāce vidyamāna lihilī āhe sarvahī tumace manogatānurūpa hoīla mhaṇuna patreṃ ālī tyābarobara tumacahī nāvī patre ālī te tyāceca vakīla rāmarāva yā barobara deūna pāṭavilī āheta śrīmaṃtāṃcī patre ādare kaḍūna gheūna āle vakilāsa ādara ināmī kharcaveca vaśreṃ deū punhā patrāce jāba deūna pāṭavāve anakūla paḍalyāsa tumace nāvī kṛpā karūna patra pāṭavile yākaritā tumhī vaśrepatreṃ deūna pāṭavaṇa bare vihita āhe he ityādika vartamāna tumhāṃsa lyāhāve mhaṇūna śrī amarasiṃvha mahārājācī ājñā jāhalī sarakārace nāvī patra pāṭavilī pāna yāja sivarāva sarakhelī karitā āhe iṃgarejācī nisabata karitā āmhāsa āpale nāvī patra lyāhāvayācī ājñā jāhalī sarakārace ājñepro| lihile āsa śrīmahārājāce cittī tumacī āmacī citaśudhī phāra asāṃvī īśvara thoḍe divasī kṛpā karī

Translation:

To the noble lord and Dutch governor at the port Pralaya Kaveri [Pulicat].

Salutations from Narsingrao Bhosle and Lingoji Bhosle, who are blessed by the friendship of the Sire Amarsingh, and endowed forever by Lakshmi [the Hindu Goddess of wealth]. Knowing the state of affairs here till Ashadha vadya 6, you should write the same at your place. In particular: after the demise of the Maharaja Tulaja Maharaja Saheb, Maharaja Amarsingh Saheb assumed the throne. At that time, we conveyed the tiding to the noble Peshwa at Pune, that we have become prisoners of the English, and that, due to us, the Dutch also suffered, as their ports Nagapattan etc. were seized by the English and only the port of Pralaya Kaveri [Pulicat] was left to them, and that there prevailed great feeling of brotherhood between ourselves and the Dutch, with each provided friendship and shelter to the other. The English disturbed this and captured various places. You [Peshwa—since Amarsingh had written to the Peshwa] are proud and powerful, and rule the whole earth. Despite this, we became prisoners, along with several merchants. We wrote to the lord Peshwa, requesting him to free us and manage the affairs as was done during the times of the late King. We wrote about many such things, including reports of our friendship and trust about you: we also brought a letter for you from the noble Peshwa himself. The latter also sent the attires for the newly coronated King, and wrote to the English in Bengal that he will attack Tipu after the Festival of Dasara and manage the affairs of the state of Tanjore and also ensure even better conditions for you [i.e., Dutch] than before, and that everything will happen according to the wishes of the Dutch. We received these letters and also a letter addressed to you. We are sending the latter with Ramrao, the Vakil [i.e., envoy] of the Peshwa. You should respectfully receive the same, give the Vakil some presents, some clothes and money, and send him away with a reply to the Peshwa's letter. Maharaja Amarsingh ordered that you should thus honour the Vakil of the Peshwa on account of the consideration he has shown for you. He also ordered that we convey these happenings to you. One Sivarao will be the chief of the army [the sentence is not clearly legible, it is assumed to be “yāja sivarāva sarakhelī karitā āhe” and then translated]. Thus we sent letters to the lordship [Peshwa] and were ordered to write a letter to you while we were serving the English. We wrote accordingly and the noble Sire [Amarsingh] gives great importance to the amity between ourselves and you. May God bless us shortly.

Lines in the margin:

hīṇa śrīmaṃtāṃkaḍuna phāra kāme hoṇa aheta tumhīṃ sudne ahāṃ je

tā.ka. taraṃkaṃbāḍīhī patre hotī tyāce taraphecī vastrepatrehī tyānī dilī jāṇije

Translation:

His Lordship [i.e., Peshwa] will accomplish many things; you are wise.

P.S.: There were also letters addressed to Tarangambadi [Tranquebar], who duly gave the letters and presents etc. from their side.

Issue Dates for Both Letters

The first letter was from the Peshwa Madhavrao Narayan, addressed to the Dutch, dated 27 Sha'ban, Suhur era 1188, which translates to 2 June 1788 CE, while the second letter simply states the date as “āṣāḍha vadya 6” and also cites the first letter, therefore it is evident that it post-dates the first letter. The date for the second letter thus comes out to be 13 July 1788 CE,Footnote 27 assuming the nearest date to the year 1788 CE. We can thus see that the distance from Pune to Thanjavur (approximately 1,240 kilometres) could be travelled within a month and a half, or, in this case, about forty days, thus averaging about thirty-one kilometres per day, a realistic speed, especially for a solo messenger.

Contents of the Letters

The first letter mentions that the Thanjavur King Amarsingh had written to the Peshwa about the Dutch affairs. Amarsingh had similarly written to the Peshwa about making less severe the terms of the treaty of Thanjavur with the British). The Peshwa further assures the Dutch that he had communicated with the British at Bengal (Calcutta) regarding both Thanjavur and the Dutch and that not only the condition of the Dutch would be improved, but enemies like Tipu would be routed.

The Peshwa's request that the VOC write back to their Badshah about the trustworthy friendship of the Dutch and Marathas shows a desire for more permanent relations between the two, sanctioned by the Dutch sovereign. This desire of Marathas for state involvement on the European side might have stemmed from their firsthand experience of how the British operated, aided in part by the pioneering voyage to England of a Maratha envoy to England.Footnote 28 Especially interesting is the Peshwa's offer that the Dutch would be given some land near Revdanda (about one hundred kilometres south of Mumbai). If successful, this would have been one of the few Dutch factories on the Konkan coast and possibly altered some of the geopolitical equations in the vicinity, given the time frame (1780s) and statesmen like Nana Phadnavis.

The second letter is a tad longer than the first. Written by the Narsingrao and Lingoji Bhosle, both ministers of the Thanjavur Maratha King Amarsingh, it cites the request made by Amarsingh to the Peshwa about making less severe the terms of the treaty with the British,Footnote 29 explicitly mentioning the “brotherhood” between the Dutch and Thanjavur, apart from the assurance of Peshwa to the Dutch. This treaty is matter-of-factly described as “the Maharaja has become the prisoner of the British,” and the letter also notes how the Maharaja had implored the Peshwa that “it is not right that you rule the whole world but still we became the prisoner of the British.” After describing in some detail the affairs of Thanjavur, the letter mentions that Mr. Ramarao, the Peshwa's envoy, will go to the Dutch with both these letters and that Mr. Ramarao be honoured appropriately with presents such as clothes and so on, given that Peshwa has written favourably to the Dutch. The P.S. of the letter repeats the assurance that “Peshwa will accomplish many things, you are wise.”

The P.S. of the second letter mentions briefly that similar letters were written to the ones at Tarankambadi, the original Tamil name of Tranquebar. This is interesting as it reveals the similar treatment given by the Thanjavur Marathas to the Danes along with the Dutch.

All in all, the tone and the details in the letter reveal an unusually warm relationship between the Dutch and the Marathas, especially those from the Thanjavur Kingdom. The letters are also important from an archival point of view, being the first known Marathi specimens of Dutch-Maratha correspondence. Of the five European nations to have colonies in the Indian subcontinent, this type of correspondence was so far missing only from the Dutch side, as there exists ample evidence of Marathi specimens of correspondence with English, French, and Portuguese powers. Even the correspondence with the otherwise neglected Danish company has been published,Footnote 30 leaving only the Dutch archives without any published Marathi letters. The voluminous VOC archives contain numerous diplomatic letters exchanged with Indian rulers, but practically all of them are translated into Dutch from the original. With these two letters, this gap is bridged, and if more such original letters (as opposed to only their translations) are discovered, it would be a welcome addition to historiography.

Maratha Perception of the Europeans in General and the Dutch in Particular

The Marathas variously perceived the Europeans in India as dangerous enemies as well as trusted allies. The Europeans’ military might was recognized early by the MarathasFootnote 31, as a result of which they frequently took European help for their own political as well as fiscal benefit. Except where the European operations threatened to undermine those of Marathas, the latter maintained an amicable relationship with them. This is especially reflected in the various incidents where the Marathas consistently favoured and/or used the Dutch in their designs, for example the rumoured Dutch takeover of Bombay in 1673Footnote 32 with Maratha help, or the Maratha offer of help to the Dutch in taking Goa in 1664.Footnote 33 Sometimes when it came to choosing between two European powers that were neutral to Marathas (e.g., the Dutch and the French), the Marathas chose the most beneficial one to them, as with the Dutch capture of Pondicherry in 1693.Footnote 34 Similarly, as late as 1780, during which year the idea of a grand anti-British coalition was gaining ground, the VOC director of Surat, Willem Jacob van de Graff, planned the capture of Surat with Maratha help.Footnote 35

The incidents cited above show that the Marathas consistently preferred the Dutch over other Europeans in India and frequently allied with them. The VOC's lack of territorial ambitions in India, as demonstrated time and again through their almost exclusive commitment to trade, especially in the late eighteenth century,Footnote 36 when contrasted with the politically ambitious English and Portuguese and even the otherwise amicable but ambitious French, must have been attractive to the Marathas. As a result, the Marathas had consistently amicable relations with the Dutch, much more than the others. Especially the Thanjavur Maratha Kingdom valued the Dutch a lot, which is revealed in the phrase “bhāūpaṇā” (feeling of brotherhood), which was used to describe the relationship between the two. That the phrase was not a mere diplomatic convention is evident from how the Peshwa also replied favourably to the Dutch. Considering the broader histories of the VOC and the Thanjavur Maratha Kingdom, one may perhaps argue that the relationship might have been cemented especially in the wake of the decline of fortunes of both the VOC and Thanjavur Maratha Kingdom in the late eighteenth century.

The two letters thus throw light on the Maratha perception of the Dutch in 1788, which was decidedly positive, shaped as it was by more than a century of largely amicable interactions. The Dutch were sans territorial ambition despite possessing the same military advantages as other Europeans, and as such were natural allies for an ambitious power like the Marathas.

Maratha Documentary Practices as Gleaned from the Letters

A great variety of documents were produced within the Maratha territories during the seventeenth- and eighteenth centuries, and there exist numerous published examples for every major type of Maratha document. A curious dichotomy existed in Maharashtra for a very long time, where the Devanagari script was used for religious purposes, as revealed from the large number of manuscripts from Maharashtra, while the cursive Modi script was used for government correspondence. Some of the oldest specimens of Modi script date to the sixteenth century. A good representative collection of many Maratha-era Modi documents is given in at least one book devoted to the same topic.Footnote 37 This book describes a total of twenty-nine types of document, while citing an older article,Footnote 38 that briefly described seventy-eight types. Many of the conventions followed while producing these varied documents were either copied from the much older Hindu kingdoms like the Yadavas as well as contemporary or older Muslim kingdoms, especially Deccan sultanates, or started anew by Shivaji.Footnote 39 The conventions followed contain a lot of nuances, reflected in the type of salutations used, the type of shiro-rekha (the single horizontal line above the Modi characters in a line), the presence or absence of the royal seal, the position thereof, and so on. The most radical reform in the documentary practices was proposed and carried out by Shivaji, shortly after his coronation as the Maratha Chhatrapati (Lord of Kshatriyas) in 1674 CE. He commissioned one Dhundiraj Vyas, a court Pandit, to compile a Persian-Sanskrit lexicon, titled Rajya Vyavahara Kosha (Lexicon for state usage). The Sanskrit preface of the text clearly mentions that the lexicon was commissioned “by the King Shivaji in order to again introduce the language of the wise, as there were many Mleccha (Muslim, i.e., Perso-Arabic) words current in the court language by then.”Footnote 40 Either as a direct result of the prescriptions in the Raja Vyavahara Kosha or simply due to the usage of a Sanskritized register of Marathi in official correspondence, the percentage of Perso-Arabic loanwords in Marathi in the Maratha court correspondence rapidly decreased from about 38 percent in the 1670s to a mere 7 percent after 1720 CE.Footnote 41 In the light of this, it would be instructive to check the percentage of the Perso-Arabic words in both letters here to see if the general preference for Sanskrit words over Perso-Arabic ones continued in the late eighteenth century.

The first letter (without the envelope) contains 159 words, out of which 38 words are Perso-Arabic, i.e., slightly less than 24 percent of the total. The second letter (without the envelope) contains 283 words in total, out of which 24 words are Perso-Arabic, i.e., about 8.5 percent of the total. It is interesting to note that the second letter, written in Thanjavur, has a markedly lower percentage of Perso-Arabic words than the one written in Pune. While the Pune figure of about 24 percent is not particularly high, it is about thrice that of the Thanjavur figure of 8.5 percent. One explanation for the marked difference between the two may be the prolonged exposure of the Peshwas to northern India, which may have resulted in a reintroduction of more Perso-Arabic vocabulary as compared to the Thanjavur court, which lacked such an intimate exposure to the Persianate sphere of influence. Even when Thanjavur had as neighbours Mysore and Arcot, two Muslim-ruled kingdoms, the Indian peninsula south of the river Tungabhadra had never been under the sustained suzerainty of any Islamic power. As a result, much less Perso-Arabic vocabulary permeated the Marathi language at Thanjavur as compared to Pune. Considering the percentages in both cases, one can safely say that the policy of Shivaji to prefer Sanskrit or Indic words in place of Perso-Arabic words was reflected in letters written even more than a century after his death in 1680.

In short, the Maratha documentary practices popularized by Shivaji and continued by his political successors contained innovations as well as continuation of traditions. Consider, for example, the beginning lines of both the letters:

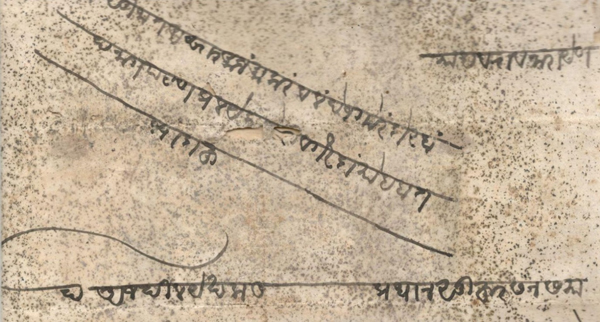

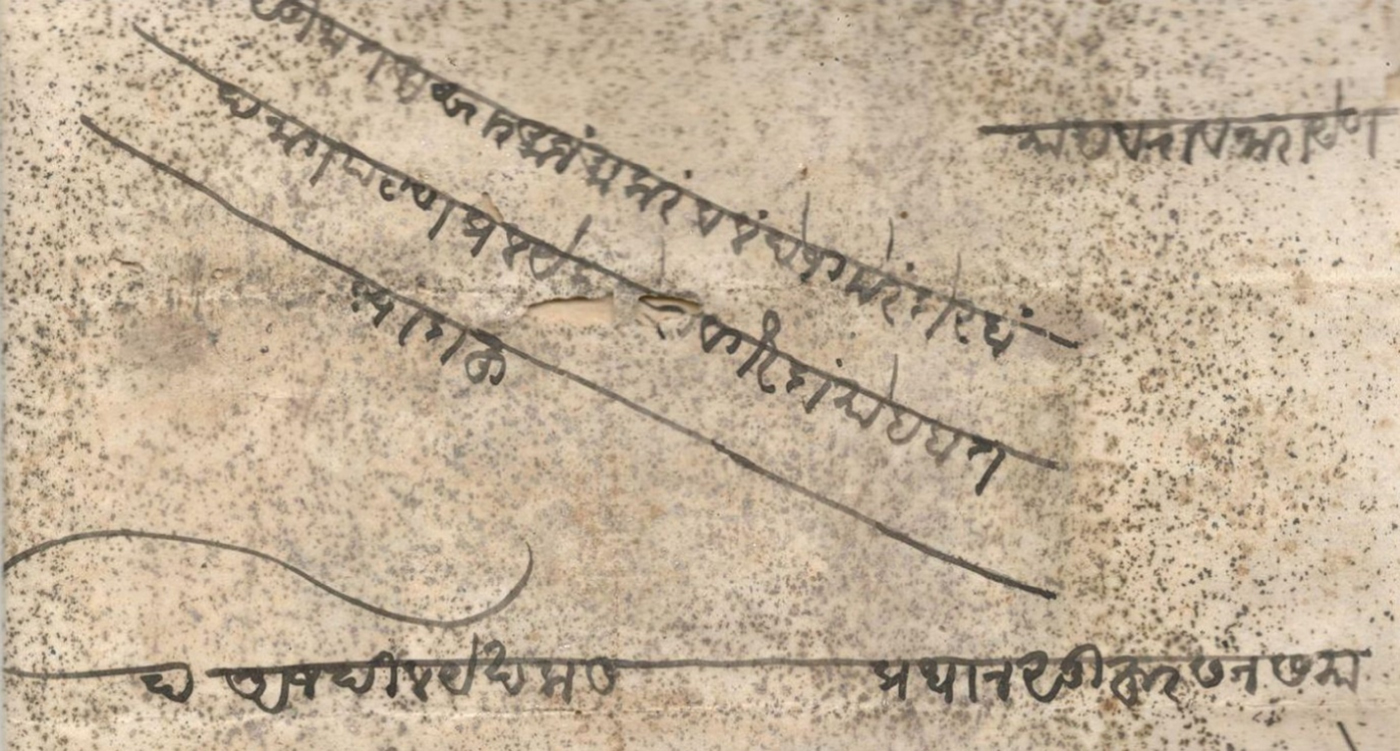

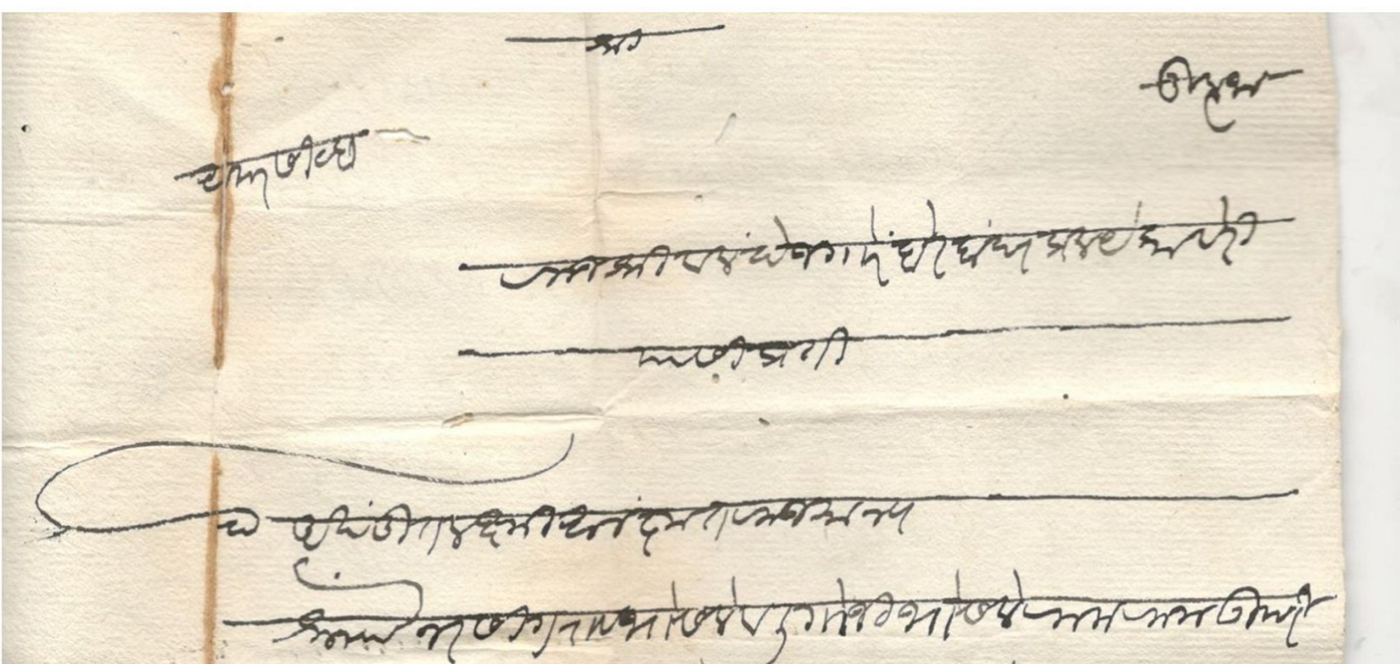

Both Figures 1 and 2 reveal a curious curvy character in the bottom-left corner. It is called a da-kāra, i.e., the Devanagari letter da (denoting the unaspirated voiced dental stop). According to a shloka (denoting a pre-Islamic convention) commonly attributed to Hemadri Pandit, the famous Yadava-era revenue minister, who is also traditionally credited with the creation of the Modi script,Footnote 42 such a usage denotes friendship of the sender with the recipient.Footnote 43 As a result, such a beginning line was used to write to one's allies and also generals.

Figure 1. The beginning of letter 1.

Figure 2. The beginning of letter 2.

The subordinates of a ruler typically introduced themselves in a letter as follows: After beginning the letter with salutations addressed to the recipient, the letter added the phrase akhaṃḍita lakṣmī alaṃkṛta rājaśrīyāvirājita rājamānya rājaśrī, i.e., “the noble, forever blessed by Lakshmi,” followed by the name of the ruler, and then by the word snehāṃkita, i.e., “blessed by the friendship of” and the name of the subordinates. This usage is seen in Figure 2 above.

When the name of the ruler was mentioned anywhere in the letter, some space was left blank and it was always written at the top, in order to signify the superior status of the ruler. Figure 1 has the words “Madhavrao Narayan” in the top right corner, and one can also see the empty space in the middle of the bottom line. Similarly, Figure 2 has the word “Amarsingh” in the top left corner and the word “Tulaja” in the right corner. The empty space in the second line from bottom denotes the word “Amarsingh,” while there is empty space elsewhere in the same letter for the word “Tulaja.”

Also noteworthy is the choice of salutations used when writing to the Dutch. In letter 1, the salutation used is sujāta asāra ajaṃ akaraṃ valaṃdeja goraṃdora, i.e., “the brave/valorous and great Dutch Governor.” Despite Shivaji's linguistic reforms, it seems that such Perso-Arabic salutations continued to be used to address Muslims and/or Christians.Footnote 44 Interestingly, the Thanjavur Ministers have eschewed such usage, even when the Thanjavur King Amarsingh himself followed the same in a letter addressed to the British East India Company.Footnote 45

Lastly, the letter from the Peshwa is written in a very clear and legible handwriting, which has often been the hallmark of eighteenth-century official correspondence of the Peshwas. The Thanjavur Ministers’ letter is less legible, more hurried, and thus contains more scribal mistakes.

Aftermath

It will be instructive to examine briefly the aftermath of these letters from both the Maratha as well as the Dutch points of view. The Thanjavur Maratha King Amarsingh, through negotiations with the British and the Peshwa, was successful in lessening the financial burden on Thanjavur. According to the treaty of 1787, the stipulated yearly payment to the British from the Thanjavur king was about 2.45 million rupees. Amarsingh protested to the British in Bengal, and wrote a detailed letter to them, explaining how their demands were unjust and how he was unable to pay the stipulated amount.Footnote 46 As a result of his extensive lobbying, the tribute was reduced from 2.45 million rupees to 1.6 million rupees per annum in 1792.Footnote 47 A few years after this treaty, Amarsingh died in 1798 and Serfoji II came to power. The British signed a new treaty with him, which reduced the king to a mere figurehead. As a result, despite his multifaceted personality, Serfoji couldn't exercise any control over his kingdom. The Thanjavur Kingdom was finally annexed under the doctrine of lapse in 1855, when Shivaji II, the last king of the Thanjavur Maratha dynasty, died without a natural heir.

The Dutch aftermath is a similar albeit a little shorter tale of the continuous decline and fall of the VOC. The VOC's inability to gather state support and rethink its policies contributed the most to its rapid decline during this period. One of the dominating precepts for the VOC was that military expenditure ought never to exceed its commercial performance. This worked well in general for quite some time, until the intra-Asian trade waned, and with it the military might of the VOC.Footnote 48 The decline in trade and the competition from other Europeans, coupled with the lack of state support from the Dutch Republic, forced the VOC to economize in its operations in order to survive. Large military establishments were thus not an option for the VOC, and the shortcomings of this policy became evident during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780–1784).Footnote 49 While this forced the VOC to rethink its policies, there was little the company could do in the absence of state support from the Dutch Republic. As a result, the company became extremely vulnerable to the local politics.

On 3 August 1790, the Mysorean army suddenly attacked Porto Novo, plundering the VOC factory there. The Dutch resident Topander escaped on a boat and went to Cuddalore. It was soon decided to break up the VOC factories at Sadraspatnam and Porto Novo, and recall the servants there to Pulicat.Footnote 50 A group of Dutchmen, intending to defect to the French, was beaten. A contemporary Marathi letter also mentions that many Dutchmen deserted.Footnote 51 Trade came to a standstill. Many factories on the Coromandel Coast suffered similarly, and finally in 1824–1825, the last of the VOC possessions in India were handed over to the EIC in return for western Sumatra.

The two Marathi letters from the Indonesian National Archive, written in the Modi script and exchanged between the Dutch and the Marathas, reveal the extraordinarily fluid and complex political context of late-eighteenth-century South India, illustrating the Maratha perceptions about the Dutch, while at the same time also being good representative specimens of the documentary practices generally followed by the Marathas. Their study is vital to understand the wider aspects of Dutch-Maratha relations as well as the history of late-eighteenth-century India.