Introduction

This article aims to reflect on the causes and consequences of the invisibility of Equatoguinean women in Spain based on their experiences in the socio-professional context. Female migration from Equatorial Guinea to Spain can be traced back to the colonial times, illustrating how the so-called metropolis and its territories have been historically connected from the mid-twentieth century—when Spain's “second conquest” of the territory took place—to the present.Footnote 1

To this day, Equatoguinean women in Spain have to overcome a series of difficulties inherent in their condition as females, while at the same time facing ignorance, precarity, social and cultural invisibility, and racism.Footnote 2 Their history is burdened by the traces of colonialism that have been left blurred in the twenty-first century by their country's marginal position in Spanish imperial memories That Equatorial Guinea's colonisation has lost centrality in Spanish history is a symptom of Spain's failure to come to terms with its colonial past in Africa. For Rizo, this is the product of “state-promoted amnesia.”Footnote 3 It is in line with the Euro-African marginalisation phenomenon that swept across Europe in the post-independence era. This erasing of the imprint of the western European colonial past must be reversed by adopting new historical methodologies, as Cooper stated.Footnote 4 African populations form part of Europe, as shown by the increasing number of migrants who have settled permanently on the continent: in 2017, of the 673,000 citizens of non-member countries residing in an EU member state who acquired EU citizenship, 27 percent were from Africa.Footnote 5

The theoretical approach of this essay is based on reflections by several different authors. Dirk Kohnert's work connects African migration to the former European metropolis. He explains current trends in African migration to Europe as well as major factors that triggered it. The case of Equatorial Guineans in Spain fits with his work, as they chose the metropolis as their preferred destination for settlement in Europe, and they were prompted to migrate by human rights violations and poverty.

Nicolas Bancel, Pascal Blanchard, and Sandrine Lemaine have studied the return to the memories of colonial France and the representations of migrants of former colonies in the post-independence era in Marseille. Their study confirmed that French memories of colonisation did not form a common history that included migrants from former colonies, who felt themselves to be “enfants d'indigènes” or “enfants de la colonisation.” Equatorial Guineans in Spain face similar obstacles and describe the difficulties of not being socio-culturally recognised as Spaniards. In this line, Elizabeth Buettner's proposition on the need for post-colonial Europe to be understood by observing the ways certain European nations experienced decolonisation themselves applies to the Spanish case. Her concept of “imperial memories” is particularly useful when describing the imaginary of Spain's colonial past. Eric Wolf's work on the central position of European history in the construction of the people of other continents, which led him to defend the history of other peoples, especially of those who are marginalised and excluded, is also of interest. Wolf's valuable reflections suggest how Equatorial Guinean women in Spain may be empowered to make their experiences of discrimination and socio-cultural exclusion visible. Finally, the research by Emma Martín Díaz et al. on migration flows from Latin America into Spain during the Spanish economic boom, and the historical connections between Spain and its ex-colonies, is very useful. The discrimination and exclusion Latin American women face by comparison with Spanish women workers, despite shared sociocultural factors such as language and religion, is very similar to that experienced by Equatorial Guinean women.Footnote 6

Migrating to the Former Metropolis: Challenges and Opportunities

Effective citizenship, i.e., political participation, legal guarantees, and social rights, has not been a part of contemporary history in Equatorial Guinea after their colonial independence in 1968. In less than six months (between October 1968 and March 1969) the country went from a hierarchical and unequal colonial regime established by the Treaties of San Ildefonso (1777) and El Pardo (1778), implemented from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, to independence under the rule of Francisco Macías Nguema. Originally the elected president of the country, Macías soon erected a dictatorship and was deposed in 1979 by Teodoro Obiang, who continues to be Africa's longest ruling dictator.Footnote 7 This political background explains why only transnational migrants who immigrated to democracies were able to break free from autocratic, colonial, and dictatorial regimes and settle down under the protection of states that guaranteed freedom of expression and welfare, regardless of gender and ethnicity. The lack of democratic experience meant that Equatoguinean men and women were unfamiliar with the social and political mechanisms in place to redress injustices and guarantee individual and group rights. For many, it was imperative to leave their small country to escape an oppressive dictatorship, where strict control was exerted on individuals, families, and the wider society, and become part of democratic societies with millions of other individuals, for anonymity and indifference considerably diminished their sense of permanent threat.

In this general context, Spain became the focal point of Equatoguinean migration and a launch pad for other destinations in Europe and America. As we shall see, Equatoguinean migrants to Spain before 1975 were settling in a markedly dictatorial country under the yoke of Francisco Franco. Colonial independence also marked a turning point for Equatoguinean migrations towards Spain as, from October 1968, their nationals lost the right to equality with the Spanish population granted in Law 191/1963 on the autonomous regime in Equatorial Guinea. This seems likely to have encouraged a drastic loss of Equatorial Guinea's visibility in Spain from that time onwards, an invisibility that was not reversed after the establishment of the democratic system that followed Franco's death in 1975. To compensate, the Spanish state allowed Equatorial Guineans to obtain nationality after two years of residence (Article 22 of the Spanish Civil Code), granting them equivalence with certain historical rights held by Latin Americans. However, although this measure led to many dual nationalities, it ended up losing effectiveness from the 2000s onwards, as a number of respondents explained in Barcelona, Móstoles, Alcorcón, Madrid, Aranjuez, Alicante, and Valencia between June 2005 and May 2019.Footnote 8

Similarly, the invisibility of the history of Equatoguinean men and women in Spain, identified in my fieldwork, shows that even during the Franco era the metropolis was the preferred destination for Equatoguinean immigrants coming to Europe. An exception was the group of Equatoguineans who fought for independence in the1960s, as they chose other African and European destinations. But in the post-independence era, Spain did not formulate cultural and educational policies aimed at recognising the shared Hispano-Guinean history. This differed somewhat from the Franco era when harnessing the continual referencing of Latin America's Spanish past, which was strongly linked in the Spanish imaginary to the “discovery of America,” Equatorial Guinea was incorporated into the “Hispanic race.”Footnote 9 The same Spanish narratives were also activated in order to subsume the African colonial past of the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco and the Spanish Sahara. Rhetoric disseminated about Hispano-Moroccan brotherhood based on Spain's Al-Andalus past remains present today, which is not the case for Sidi Ifni.Footnote 10

The absence of narratives about the shared history uniting Equatorial Guinea and Spain in the twenty-first century—among them histories of violence and of abuse—means that the country is left on the margins of today's imperial memories and, therefore, of its imagined cartography of its colonial past. And yet, a century ago, following the crisis unleashed in 1898 by the losses of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, Equatorial Guinea's colonial past had a central position that, with ups and downs, it retained throughout the Franco era. In 2019, the ultimate expression of Spanish–Guinean common history is the repeated mentions of Equatorial Guinea as the only Spanish-speaking African country.

However, this invisibility is at odds with Spain's central place in Equatoguinean transnational migrations and in Equatorial Guinea's contemporary memory—beyond the more or less failed Afrocentric rhetoric of Macías and Obiang. That indifference is harmful to many Equatoguineans in the diaspora. Lacking a narrative about their place in Spanish history means they disappear into the wider Spanish population and the group of Africans and Latin Americans settled in Spain.

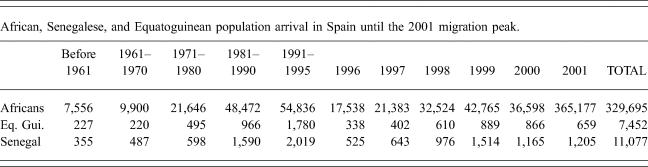

However, other aspects also have an impact on current Equatoguinean sociocultural invisibility. On the one hand, an important factor was the relatively reduced scale of the Spanish settlement of the ex-colony, meaning that the civilian population that settled in Spanish Guinea was small.Footnote 11 I will refer to this in a later section. On the other hand, with Equatorial Guinea being small in both size and population, the number of Equatoguineans who migrated to Spain was relatively low. Indeed, Equatorial Guinea's population was 1,267,289 inhabitants in 2017, and it is estimated that only 20 percent of the Equatorial Guinean population, then estimated at 225,000 inhabitants, settled in Spain between 1968 and 1970. This small group in a medium-sized European state such as Spain (46,733,038 inhabitants in 2017), helps us understand their invisibility in the country. Another factor that is likely to have contributed to Equatoguinean invisibility is their similarity to Latin American populations in terms of language and religion. Latin Americans have comprised a very large part of the total number of foreign residents of Spain since the year 2000: in 2010, 1,760,030 Latin Americans were recorded—30.6 percent of the 5,747,734 total foreign residents of Spain (the largest group was European foreigners). This number fell to 1,144,435 Latin Americans in 2018, somewhat higher than the number of Africans, which rose to 1,066,029, the majority of whom were Moroccan. Considering these data, the Equatoguinean population may have been absorbed twice over: by the Latin American due to their similarity in terms of language and religion, and by the African population in terms of their similar cultural traditions.

Thus, though migration is widely regarded to be a permanent phenomenon in today's world and the destinations chosen by African migrants can reflect Europe's colonial past—with some migrants opting to settle in their former metropolis—certain host states would have to officially recognise the history of migration from former colonies. Spain and its former colony of Equatorial Guinea is one such case. This leaves Equatoguineans with a sense of orphanhood with regard to their integration in Spain, with little empathy for the difficult circumstances in which their relatives are living in the Equatorial Guinean dictatorship, and disappointed by the indifference their efforts to send back the remittances that guarantee the survival of their most needy relatives provokes amongst Spaniards. All this took place just as the fiftieth anniversary of colonial independence was being celebrated, when the Spanish population returned to their country after decades of living as the favoured parties in an exploitative system. Undoubtedly, public bodies promoting Hispano-African memories in order to rebuild historical and cultural bridges with citizens of Equatoguinean origin residing in Spain could improve the generalised lack of knowledge on the subject.

Female Migration from Equatorial Guinea to Spain

The number of Equatoguinean citizens living in Spain in 2018 was 13,039, of whom 8,220 were women. They therefore comprise a tiny minority of the overall foreign population, which in 2018 was 4,663,726. What is more, the figure does not reflect the total number of Equatoguineans who have settled in Spain in the past eighty years, as after settling they have gradually regularised their status, obtained nationality, and disappeared from the non-EU resident statistics.Footnote 12

Women from Equatorial Guinea in Spain are a heterogeneous group with different ethnic backgrounds; these include the Fang, the dominant people of the mainland; the Bubi and the Fernandinos from the island of Bioko; the coastal group of the Ndowé; and the Annobón from the smaller islands. Their migration to Spain can be divided into three different periods.

The first period corresponds to the colonial era, from 1940 until 1968, when Equatorial Guinea achieved its independence. In these first few decades, immigration was a minority phenomenon. Most immigrants were students who came to Spain through missionary channels, and most intended to go back to Equatorial Guinea after completing their academic education. For obvious security reasons, activists from the independence movement who were forced to go into exile never chose to migrate to the “metropole.”

In this colonial period, more men than women left the country. However, things changed in the 1960s thanks to the women's migration channels opened by Franco's Sección Femenina (Women's Section).Footnote 13 Even if the women who travelled to Spain via these connections did not plan to stay in the country—and indeed most eventually went back to Equatorial Guinea—the testimonies from the Women's Section show how pressure was put on female Equatorial Guinean students to return to their country.Footnote 14

The second period comprises the years from 1968 until the end of Francisco Macías Nguema's dictatorship in 1979. One of the most remarkable events in this period was the abandonment of Equatorial Guinean students in Spain: they became stateless when Macías took over power in 1969 (a situation to which Spanish dictator Francisco Franco's response was rather lukewarm), and some women only survived by resorting to prostitution.Footnote 15 This situation did not, however, necessarily improve once their legal status was resolved. The pressure on the Equatoguinean female workforce at this time already paralleled the situation Brah found among Asian-origin women in Great Britain: namely, that they obtained worse jobs and remuneration than white people with lower educational levels.Footnote 16 For example, after Remei Sipi, a writer from Equatorial Guinea interviewed in November 2016 in Barcelona, was granted Spanish citizenship and found a job in a daycare facility in Barcelona, some parents started putting pressure on the school when they learned a young black woman was to take care of their children. Many threatened to withdraw their children and indeed did so. Sipi eventually lost her job, but in time found another better one after making efforts to improve her working situation. Her case illustrates how the rejection of Equatoguinean workers slowly improved along with their working conditions following Equatoguinean regularisation.

This was also the period of so-called Guinea, materia reservada (No talk on Guinea): from 30 January 1971 to 20 February 1976, the Spanish government censured reporting about what was going on in the country, precisely at a time when Equatoguinean immigration to Spain was peaking. In this decade, Equatorial Guinea was virtually non-existent in the Spanish public sphere; if it was mentioned at all, it was as the exotic site associated with former colonists and military personnel.Footnote 17

The third period of migration from Equatorial Guinea to Spain began with Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo's dictatorship in 1979. However, Equatoguineans have remained virtually invisible in Spain, even as democracy became fully established after Franco's death. The work done in those years to denounce the Equatoguinean dictatorship by certain newspapers such as El País was not enough to make the Equatoguinean residents of Spain visible.

Things changed to some extent in the mid-1990s, when oil reserves were discovered in Equatorial Guinea. Spain regained interest in its former colony and invested political capital in friendly relations between both countries. Nevertheless, this goodwill did not include supporting the aspirations of some Equatorial Guinean politicians (some exiled to Spain, some still in the country) to establish a democracy with the help of the “homeland.”Footnote 18 According to the anthropologist Gustau Nerín, Equatoguineans who were not able to go back in the second period went from being “the generation of hope” to becoming “the lost generation” in this third period.Footnote 19

A significant increase in migration of women from Equatorial Guinea commenced in the 1980s. These women had, in some cases, access to the same education as Spaniards, but they were offered fewer opportunities afterwards. As I will show below, only a small percentage of them found jobs that matched their education and qualifications; many became housewives, while others faced difficulties and slipped into the mostly informal domestic labour sector, services in the formal sector, and prostitution.

The period in which Equatorial Guinean women joined the labour market lasted from the 1990s until the 2007 economic crisis, although their educational levels were still no guarantee of better jobs and remuneration. Although this has since proved to be a fiction, Spanish society was considered to be rather homogeneousFootnote 20 in the late 1990s. In fact, significant numbers of migrants came to Spain from Western Europe, Morocco, and Latin America.Footnote 21 This myth of cultural homogeneity was demolished in the early 2000s, when migration from several Latin American, African, and Asian countries to Spain peaked. According to Javier de Lucas and Francisco Torres, in 2002 foreigners accounted for 3 percent of the population in Spain, 70 percent of whom came from outside the European Union. In 2011, the foreign population in Spain had risen to 11.21 percent and in 2018 it dropped just over one percentage point to 10 percent of the total population.Footnote 22

As Giovanna Campani accurately analysed in 2007, it was not until 2000 that the first comprehensive study on immigrant women in Spain was published, at a time when migration of Latin-American, Moroccan, and Filipino women was on the rise.Footnote 23 It was then, in the early 2000s, that immigrant communities grew the most, and the “African situation” (exploitation and precarious housing) gained visibility in booming agricultural farming areas such as El Maresme in Catalonia and El Ejido (Almería) in southern Spain.Footnote 24 As Martín Díaz et al. pointed out, it was from the year 2000 onwards that the rhetoric of the “mother country” was activated to justify the preference for labour coming from Latin America. It was argued that these migrants were “culturally compatible” because of their shared linguistic and religious affinity with Spaniards, although the ultimate goal of this narrative was none other than to diminish the arrival of an African workforce considered to be an unassimilable other. Of course, replacing African labour with Latin American did not mean Latin Americans’ cultural proximity was reflected in improved working conditions in Spain. As Martín Díaz et al. explain, these precarious conditions were deeply embedded in the globalised market rationale.Footnote 25

During the Macías and Obiang dictatorships, fear prevented many Equatoguinean citizens from visiting their families in Equatorial Guinea, a situation that did not change until the mid-1990s. Combined with the fact that those who were born in Spain had little interest in getting to know their parent's country of origin, this meant the number of Spanish nationals in Equatorial Guinea remained low until the financial crisis hit Europe in 2007, triggering the unforeseen return of some Equatorial Guinean emigrants.Footnote 26

On the whole, migration data help to explain two phenomena: first, women from Equatorial Guinea who emigrated on their own generally strove to complete their education (either by going back to school or by seeking further training within the job market); and second, most women who emigrated together with their families fled from Macías's violent dictatorship or Obiang's repressive and corrupt regime. Although the two groups emigrated to Spain for different reasons, their practice of citizenship was hampered for the same reasons.Footnote 27

Colonial Imprints Seen from Spanish Guinea and Spain

As indicated above, Equatorial Guinea remains on the margins of Spain's imperial memories and obscured from its colonial cartography. Equatorial Guinea is denied the recognition given to Latin American countries, whose colonial suffering and exploitation have been more explicitly acknowledged. This is despite the fact that the colonial impact on Equatorial Guinea is more recent and highly similar to the impact on the populations of Latin America in terms of Catholic missionary activity, linguistic and cultural assimilationism, and territorial exploitation.Footnote 28

One of the most visible impacts of the Spanish presence in Equatorial Guinea was the implementation of Spanish as the official language. Nonetheless, Spanish, unlike the country's indigenous languages, never became the primary language for a majority of Equatorial Guineans. It did, however, become a lingua franca, even if its hegemony as the most used language in some public contexts is now coming to an end, due to the rise of Pichi, the former Fernando Po Creole English, in places like Malabo.Footnote 29

Linguistic hispanicisation was promoted by the fact that schooling in Equatorial Guinea almost always lay in the hands of Spanish missionary orders, which meant that knowledge of the Spanish language, geography, and history spread widely among the population through school books.Footnote 30 What in many respects could be considered unnecessary knowledge has helped Equatoguineans to become integrated into Spanish society much faster than immigrants from other countries and to often be confused for migrants from Latin America due to their perfect language skills.

What is more, Equatorial Guinea was the only African colony under Spanish rule to inherit the right to the colonisers’ citizenship, a right which some populations in Latin America also had. This is yet another connection between the hispanicisation process in the Americas and the colonisation of Equatorial Guinea.

Women's access to education was severely limited from early colonial times. Racism deprived Equatoguinean women of all social value. A clear example of this is what former settlers called “consensual sex” between Spanish men and black women in the colony, at a time when Spaniards were strictly forbidden to enter into mixed marriages. This phenomenon is brilliantly described by Nerín in his Historia en blanco y negro. Despite the dictatorship's official anti-racist rhetoric (mestizaje), relationships between Equatorial Guinean women and Spanish men were not legal, and only a very small group of Spanish men took their Equatorial Guinean partners and children with them to Spain on the brink of independence in 1968, or when they fled to Spain after the rise of the dictator Macías in March 1969.Footnote 31 Mixed marriages were highly unusual at that time. Lucía Mbomio's novel Las que se atrevieron describes exceptional cases of white women going against the norms by returning to Spain and marrying Equatorial Guinean men. Along with Trifoinea Melibea Obomo and Desirée Bela-Lobedde, Mbomio is one of the most promising of a generation of Equatoguinean writers that emerged in 2016 who have been working ever since to counteract the invisibility of Equatoguinean women in Spain. The three writers are having a major impact, following the Equatoguinean precedent set by María Nsue, Raquel Ilombe, and Remei Sipi, the latter predominantly in essays rather than fiction.Footnote 32 Nevertheless, imperial memories and the Spanish government's sense of responsibility are fading away.

In Spain, little is known about Equatorial Guinea except amongst people whose relatives have worked there (as public or private employees) or those who owned land in the country during colonial times. The most influential Spanish–Equatorial Guinean imperial memories are Spanish, not Equatoguinean. Most of the historical and literary accounts were written by (mostly male) civil servants or colonists recounting their experiences in Equatorial Guinea. This is a very small group, as we have seen, although it is fairly united and has a degree of influence in some institutions such as, for example, the Institut Catalunya-Africa. Their accounts were never fact-checked, and their emic nature is evident at first glance.Footnote 33 Some of these texts have been supported by Spanish public institutions such as Casa de África. Amongst these memoirs and fictional accounts, Luz Gabas's successful novel Palmeras en la nieve stands out. Some Equatoguineans think this book recreated the Spanish–Equatorial Guinean coexistence quite accurately, but its film adaptation has been deemed a failure by most observers.Footnote 34

Despite the fact that their influence in Spain is nearly non-existent today, some Equatoguineans continue to attempt to counter the benevolent Spanish accounts of benevolent colonial times as Obiang Biko did in 2016 when thanking Casa de África for its support. Some, but unfortunately not many, do so by writing novels. Two good examples of this are Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel and his books La Carga (1999) and Derecho de Pernada (2000) studied by Rizo, and Donato Ndongo and his Las tinieblas de tu memoria negra (1987), which has been accurately analysed by Ugarte. Ávila, Laurel, and Ndongo, like most up-and-coming Equatorial Guinean writers since 2010, have received no support from major Spanish publishers. They have struggled to have their work published by small publishing houses or in foreign languages, some of which work under precarious circumstances, as Obomo and Mbomio also did. A further example is Recaredo Silebó Boturu, who wrote Luz en la noche (2010).Footnote 35 These Equatoguinean accounts and testimonies matter because they speak of Equatoguineans and the colonial past in a way that differs from the usual imperial memories; they convey a sense of the often violent traces that Spaniards left in their country and their society.

One consequence of the lack of visibility of the shared Hispano-African past is that men and women from Equatorial Guinea have become strangers to large sections of Spanish society. Their presence has been overshadowed by those of larger African groups with greater political influence in Spain, such as the Senegalese. Indeed, migration from Senegal to Spain became the focus of African migration studies because of its quantitative significance, while qualitative factors (such as the issue of which countries were former Spanish colonies) were left out of the picture.Footnote 36

Being an Equatoguinean Woman in Spain

As mentioned above, the number of Equatoguinean women in Spain began to grow in the 1980s, when many moved there to study after receiving aid from relatives who were already living in Spain, or a grant from the Spanish government, or help through the missionary channels that went back into operation after having almost disappeared during Macías's regime. With the exception of the pioneers, most young Equatorial Guinean females between the age of fifteen and seventeen could count on a family support network when migrating to Spain to continue their education, which made the whole process much easier, including obtaining the necessary visa.Footnote 37 The family support network was the extended way the women who migrated to Spain after the 1980s and completed their education there managed to find work as midwives, nurses, or civil servants. In fact, in terms of professional accomplishments, these women advanced further than those who migrated to Spain from the mid-2000s onwards, when the harsh financial crisis that hit Spain led to poorer working conditions and made it more difficult for these women to access skilled jobs, since they were competing directly with the Spanish.

Although double nationality was finally granted, which meant they acquired the same rights as any other Spanish woman, not all of them were able to obtain skilled jobs, even if they had good grades as students. In fact, the data which I gathered during the fieldwork and interview stage indicate that the level of academic education completed amongst the Equatoguinean population is probably higher than the Spanish average, for these men and women set a higher value on state-provided education than Spaniards of European origin. They therefore make the most of every educational opportunity, in hopes that this would eventually open the door to better professional opportunities both in Spain and in Equatorial Guinea, should they decide to return.Footnote 38 But the high educational level of most Equatoguinean women is not reflected in their working, social, and political success. Equatorial Guineans believe this is due to skin colour. As Begoña, an interviewee originally from Malabo who left Alcorcón to settle in London in 2000, pointed out in August 2016: “In Spain there is a lot of racism, you can't imagine! Even if we've been to a private school and are Spanish, they won't let us be anything but maids or prostitutes. That's it. They won't let us succeed!” Certainly, according to the interviews, one of the challenges Equatoguinean women face in Spain relates to their skin colour. For example, María, originally from Bata but settled in Móstoles since 2000, explained in May 2019 that “Of course being black creates barriers and difficulties for me, but I rise above it because I know that I am opening up a path for other Equatoguinean people. . . . They look at me with real respect when I say that I'm not cleaning in the school, that I'm a teacher.” This topic is further explored in Bela-Lobedde's book Ser mujer negra en España, an autobiographical essay from 2018 which was reprinted five times in one year, a clear sign of the interest in racism in Spain.Footnote 39

However, while it may be true that many Equatoguinean women have not had the same opportunities as other Spanish women, they are by no means the only group for whom this is the case. As Martín Díaz noted with regard to Latin American women, acknowledging their colonial past, with Spain casting itself as the “mother country” and placing them at the top of the list of preferred foreign migrants did not improve their social and work opportunities. In both cases, as in others, what took place was the racialisation of differences, with all its pernicious effects. As Stoler and Strassler stated: “Blacks are not oppressed because of race or racism. . . . They have not seized the opportunities available to them.”Footnote 40

For this reason, what seems to be failing in Spain is a social ladder that prizes merit and capability and rejects ethnic and gender considerations.Footnote 41 I was given a glimpse of this in my multisited fieldwork in Britain, where the Equatorial Guinean women interviewed described leaving Spain because of the discrimination they faced in terms of work and pay due to their status as “black women.” Carmela moved from Madrid to Paris and then on to London in 1999, where she told me in July 2010 that “the advantage is that I am not a foreigner here, even if I am black. That's not the case in Spain.”

Many Equatoguineans would have liked a positive narrative to exist that described the cultural connections between Spaniards and Equatoguineans and did justice to the events that took place. They believed this would empower them in Spanish people's eyes. Begoña (interviewed in London in January 2010) recalled an event from a few years earlier when she was an advertising student at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid: “It pisses many Spaniards off that I am black and Spanish, but what can I do? . . . A Spanish woman was very impertinent with me, thinking that I was teasing her and when I answered, in Spanish, that this kind of thing was really out of date and she should say something more original, she was stopped in her tracks. . . . Yes, I was a black Spaniard.”

Most women I talked to described their self-consciousness due to the colour of their skin and mentioned numerous obstacles that impeded their efforts to improve their status in society. The only exceptions were wealthy black women, who knew that rejection would be buffered by class, thanks to intersectionality. The accounts of these women's daily lives (the wealthy black women apart) clearly show how many difficulties they face when attempting to achieve equality: they fail job interviews once the interviewers realise that they are black; their average salaries are lower than those of white women; they are more vulnerable on the job market than other female workers; they have difficulties obtaining a raise and improving their job conditions; they are despised by other people for no apparent reason; and they are verbally and physically assaulted in public, to name only some of the experiences recounted by my interview partners.Footnote 42

Needless to say, Equatorial Guinean women are well aware of this situation, and so they show a will to work, study, and fight for a promotion that is stronger than that of many Spanish women. However, there is no guarantee that they will succeed in this effort. And despite all, many women from Equatorial Guinea would rather stay in Spain than return to their country; they have accepted that, in order to improve their social and financial status, they need to get an education and fight for their place in the job market.Footnote 43

Although a significant part of the Equatoguinean population in Spain has completed higher education and acquired skills, not all of them have been able to find employment that matches their qualifications. Only few have entered liberal professions and achieved stable financial positions. Another small section is connected to the delocalised elite enriched by Guinean oil. They spend part of their time in their country, and part of their time in Spain. In general, many Equatorial Guineans have had to settle for entry level jobs or very low salaries. Rita Bosaho, Remei Sipi, Vicenta Ndongo, and Lucía Mbomio are examples of the embodiment of success, even if they are still exceptions to the general rule. Rita Bosaho is a politician of Equatorial Guinean descent, a member of the Podemos party, and since December 2015 also the first black Spanish MP. Remei Sipi is writer, editor, and essayist. She combined her work as a civil servant with leading the fight to improve African visibility in Spain. Vicenta Ndongo is an actress who studied at Barcelona's Institut del Teatre. She has starred in many films and in over a dozen theatre plays, and she has also participated in TV programmes. Lucia Mbomio is a journalist and author of the abovementioned novel, Las que se atrevieron. She has worked as a reporter for various television programmes, directed documentaries, and collaborates with the online community Afroféminas.

Hence, the social advancement of the Equatoguinean population in Spain has faced obstacles that are visible in a variety of different settings: in the social and political sphere, Equatoguineans encounter difficulties when they wish to participate in political structures such as town councils, regional governments, and political parties; in the financial sphere, they have trouble obtaining bank loans for personal projects and business undertakings; in the cultural sphere, they have been left out and experienced discrimination in some artistic and cultural contexts; and in the social sphere, they have often been unable to achieve a “normal” level of integration into the community and become “normal” citizens.

For all these reasons, the job options for most Equatoguinean women are very limited and they frequently end up working as cleaners and, in smaller numbers, as prostitutes. This is true even for women who have completed higher education at Spanish universities and obtained post-graduate degrees, which demonstrates how restricted opportunities are for this group. In the case of prostitution the problem was accentuated by the Spanish economic crisis that began in 2007 and the Equatoguinean crisis of 2014. Some families who sent their daughters to Spain to study became unable to continue providing financial support, leaving their daughters to take underpaid jobs or even resort to prostitution if they did not want to return to Equatorial Guinea.

Conclusion

Greater inclusion of Equatoguinean experiences in Spanish imperial memories will not solve the social and labour precariousness faced by Equatorial Guinean women in Spain that figures such as Bosaho, Sipi, Mbomio, Bela-Lobedde, and Obomo are attempting to reverse. But shared Hispano-Guinean memories of the colonial past and a shared culture of remembrance could lead to their empowerment and reduce the sense of orphanhood many Equatoguineans feel. At the same time, empathy would promote the respect for diversity that all African groups settled in Europe require.

What is more, Equatoguinean women's struggles to obtain qualified jobs to match their academic education, the specific incidents of racism to which they are subjected, and their diagnosis that the colour of their skin and their Africanness are the causes of their rejection, give a face to the racialisation of migrants that has taken place in other contexts, and which requires the urgent implementation of policies that promote equality and address Spain's ethnic, race, and gender issues.

As long as the situation is not reversed by empowering Equatoguineans as a group through memories and equal opportunities, many women, subsumed into the wider African population, will give contrasting answers to questions about their identity dilemmas, with some affirming their Spanishness and others preferring to emphasise their Africanness. Without recognition and rights, their efforts to escape precarity and improve their position in Spanish society will continue to be an unfair fight.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the project Enriching European Cultural Heritage from Cultural Diversity and Collaborative Participation (2017–2019) (EUIN2017–85108) and by the research and development project African Memories: Reconstructing Spanish Colonial Practices and Their Imprint in Morocco and Equatorial Guinea. Towards a Spanish-African Cultural Heritage (2016–2018) (HAR2015–63626-P, MINECO/FEDER, UE). Both are Ministry of Economy Competitiveness of Spain projects directed by Yolanda Aixelà. The author would like to thank Andreas Stucki for his generous suggestions regarding the text, and to the three reviewers who worked hard to reinforce the theoretical basis and main arguments of this article. The text has been translated by Tom Hardy.