Introduction

While there is much critical work on various aspects of the political history of Himalayan polities—Tibet, Afghanistan, Kashmir, erstwhile NEFA (North-East Frontier Agency, now the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh), erstwhile princely kingdom of Sikkim (now the Indian state of Sikkim), Indian North-Eastern states, and NepalFootnote 1—Bhutan's political history has often received only cursory attention or obligatory mentions from scholars of the region.Footnote 2 This present article is part of a wider ongoing endeavour that revisits the history and politics of this understudied country from, what are by now familiar to historians of other areas, as subaltern, postcolonial, and decolonial perspectives, in order to interrogate the ways in which historical work on Bhutan has been wanting, and how that impacts our contemporary understanding of its geopolitics, history, or foreign policy. Prominent in terms of influence, much British and Indian historiography on Bhutan has traditionally consisted of British and Indian scholars selectively choosing a narrative through-line of time periods and in spotlighting events that assist in arguing for their own respective country's paternalism and benevolence.Footnote 3 The historiographical politics of knowledge production about Bhutan over time also reveals a systematicity with which conventional accounts were produced, a selectivity with which texts travelled forward in time, and the salience of a positionality in how lesser privileged creators of knowledge were omitted from memory, recognition, and reward.Footnote 4 The standard narratives about the history of Bhutan have often been problematic for factual inaccuracies and for how they suppress the role of British commercial and territorial interests in imperial interactions with Bhutan in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and Indian security interests playing a similar role in the twentieth century.Footnote 5 By contrast, recent critical work on Bhutan can offer new insights, for instance on how Bhutan's geopolitical location has been exhaustively constructed as “asymmetrically inbetween” India and China, in a way that naturalised its southward orientation as inevitable, whereas this was the product of strategies (including territorial appropriation, treaty making, paternalism, assistance, and fostering economic dependence).Footnote 6 Likewise, the continued representations that focus on India as the only friend of Bhutan and China as the only threat for Bhutan have similarly been detrimental for understanding modern Bhutan's foreign policies or for explaining its internationalisation over time.Footnote 7

In order to advance further ameliorative scholarship on Bhutan, it is necessary to re-read the colonial sources, especially the archival records of British officialdom, and to subject them to critical scrutiny in order to draw attention to their dissensions and selective amnesias,Footnote 8 and to highlight the dissonance between public pronouncements and archival records.Footnote 9 I do exactly this here in the present article. Significant unpublished archival documents that I bring to light in this original work include a comprehensive report written by Charles Bell (the political officer and chief British architect of the 1910 Treaty of Punakha) that detailed the history of negotiations that culminated in the revision of the 1865 treaty of Sinchula into the 1910 treaty of Punakha between Britain and Bhutan.Footnote 10 In this report (hereinafter referred to as Bell's treaty report), Bell presented a narrative of the conduct and conclusion of the treaty negotiations. I also refer to Bell's other correspondence in 1909 where he gives an account of the initiation and progress of his proposals for treaty revision before they are accepted as recommendations.Footnote 11

The following examples illustrate the value and rationale of critical work that re-examines the colonial sources. In his 1910 treaty report in the archives, Charles Bell listed several benefits the British gained from the new treaty. An important fact that has never been commented upon by scholars so far is that these benefits are not identical in the 1910 treaty report by Bell and the public version in his 1924 book, Tibet: Past and Present,Footnote 12 the former being more detailed and candid. In his treaty report, Bell listed several advantages that he omitted from his public expressions later.Footnote 13 In his book, he was careful not to talk of the profits of “British capitalists” but rather of the “British and Indian tea gardens.” He also mentions in his book that the treaty was gained without military action but omits the references he made in the 1910 treaty report in the archives to the costs to pride or to religion. In another example, in his book, Bell remarks that the Maharaja was an able ruler, with perfect courtesy and a quiet sense of humour, and Bell was honoured to be among his friends. In the 1909 treaty correspondence in the archives, he states that “the Bhutanese from Maharaja to raiyat [population, peasants] are a people particularly greedy of money. The promise of a quick payment of the extra money will, I think, have a strong effect with them. . . The Bhutanese do not understand our ideas of account.”Footnote 14 I can imagine that from Bell's point of view, respecting sensitivities in the interests of diplomacy or fear of censorship might have been the reason for this divergence,Footnote 15 however, a critical reading of how imperial accounts are carried forward in time requires scholarship to remark upon and attend to such dissonance.Footnote 16 Political Officer Bell of the 1909 correspondence and the 1910 treaty report is a far cry from the “Tibetanised” and sympathetic Bell often found in Himalayan studies. The original archival sources are what I draw upon here in my article; this is in contrast to the sanitised version of the treaty advantages in Bell's book, which are generally reproduced as given in historical work, and make the treaty out to be something that was “good for us and good for Bhutan.”Footnote 17

As a small sovereign country in the eastern Himalayas, Bhutan's historical relationship first with British India and then with the successor state of post-colonial India explicitly, extensively, and repeatedly references “friendship” as the main basis of the relationship between the states. An important component of this key trope has been the “friendship treaty” in its various iterations (1774, 1865, 1910, 1949, 2007).Footnote 18 This article empirically enriches the field of scholarship on history of this friendship in the context of Bhutan, and also contributes to an original political historical understanding of the setting of an important treaty at a turning point in 1910 through arguments made on the basis of archival work. I provide a longer history of how and why this friendship, between two countries that were asymmetrical in size and power, came into being. As I explain later, ambiguity remained at the heart of these relations between friendly polities. The analysis here focuses on how at the start of the twentieth century, British India and Bhutan were joined in a consenting relationship of treaty friendship with a clause that specifically set the boundaries of what each side hoped the other would do, and refrain from doing.

The context for considering friendship in relation to politics broadly is the intuitive understanding that affect plays a role in all relations, be they between individuals or states.Footnote 19 The vocabulary of friendship captures the role of affect in politics;Footnote 20 it allows for conceptualising new directions of enquiry by illuminating the study of relations between nations horizontally and reciprocally, rather than only with the vertical imaginary.Footnote 21 Through a greater focus on relationality, it can enable a recognition of complexity and create a move away from an ontological situation of continued anxiety and self/other dynamic.Footnote 22 This transformative potential arguably inherent in the notion of friendship when applied to statesFootnote 23 is empirically variable and certainly worth analysing in the context of friendship treaties.Footnote 24 The existing overviews of friendship treaties,Footnote 25 with a focus on the language of friendship used therein, differentiate between a Nehruvian model of friendship as diplomatic method of goodwill and peace-building and a manipulative, utilitarian, and superficial use of the signifier “friendship” as a tool for the economic and commercial interests of larger powers. The complexity of the narrative that I provide here indicates that such relationships are not exclusively either strategic or normative, and the 1910 treaty that played a most important role in shaping the relationship of Bhutan with Britain (and later through treaty inheritance, with India) was a mix of creating friendly goodwill as well as an instrumentalisation of friendship. In this way, this account further affords a historical insight into the ways and means, as well as the constraints, through which state-making proceeds.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows. I begin by tracing the longer backstory of friendship vocabulary in the context of Bhutan's treaty relationships over time as a prelude to focus on the 1910 Treaty between Britain and Bhutan, highlighting why such a focus is important. Then, I concentrate on explicating how a relation of friendship came into being between Bhutan and British India at the start of the twentieth century through the 1910 treaty of friendship; I offer a critical analysis that highlights the role of interpersonal friendships, the threat of an Other, and the representation of ideational or material advantages in how and why the 1910 friendship treaty was realised. I conclude by reflecting on the significance of imperial friendship treaties such as the one I analyse here in terms of what they achieve, the conditions under which they do so, and their legacies in the political history of the Himalayas.

Bhutan and Friendship

The year 2018 saw year-long series of events marking the “golden jubilee celebrations” of the establishment of formal diplomatic relations between Bhutan and India.Footnote 26 An official publication marking this occasion and celebrating the friendship had as its cover the number fifty written in the colours and symbols of the two national flags, and underneath it the lettering in bold caps: “Bhutan-India: An Enduring Friendship.”Footnote 27 It listed three broad categories of the friendship celebration: commemoration; events; and milestones. The very first line of this text begins thus: “Bhutan and India share strong bonds of friendship and mutually beneficial relations.” There is mention of the “unique” bilateral relations that are “special” and “characterised by complete trust and understanding which have matured over the years.” I offer this as an example of how the rather remarkable and emphatic friendship discourse between Bhutan and India is connoted. The reference to “friendship” has been such a powerful frame shaping the international relations between the two countries, both at the level of official and popular discourse, that today it has submerged Bhutan's historical relationalities with other polities such as British India, China, or even Tibet.Footnote 28 The historical memories of Bhutanese-Indian friendship are repeatedly reinforced by placing an extraordinary emphasis on the Nehru-Wangchuck meeting in 1958—when Indian Prime Minister Nehru went to Bhutan, travelling part of the journey on the back of a yak, to meet the third king, Jigme Wangchuck—which is projected as the genesis of Bhutan's friendship relations with its neighbouring country, or indeed with any entity at all. With a well-thought-out diplomatic choreography engineered by the Indian political officer,Footnote 29 this encounter is fashioned as the defining moment of Bhutan's international relations that are traced back to the friendship relations in the 1949 treaty between India and Bhutan. This Indo-Bhutan friendship story references stability, soft power, development aid, hydropower collaboration, tourism, and, increasingly, Buddhism as the basis of the links.Footnote 30 In contradistinction to this conventional and rather myopic narrative of Bhutan's friendship and treaty relations that focuses only on the mid-twentieth century, I argue that there is a much longer historical account of friendship between Bhutan and British India.

It was in the mid 1770s that George Bogle, a young official of Scottish origin, undertook a journey up to Tibet at the behest of Governor-General Warren Hastings. Bogle's mission was concerned with commercial reconnaissance for trade rather than diplomacy,Footnote 31 and the treaty signed in its aftermath, which was largely about commercial arrangements, was the first to reference friendship as an argument for extracting concessions. An Anglo-Bhutanese treaty had been signed in 1774 (to conclude the hostilities of the first Bhutan war) and another one was signed in May 1775, on Bogle's return visit, between the Deb Raja (Druk Desi) of Bhutan and the Governor-General, which stated that “the Governor as well as the Deb Raja united in friendship, being desirous of removing . . . obstacles, so that merchants may carry on their trade free and secure as formerly.”Footnote 32 Bogle himself has been remembered for his genial getting-along with the Tibetan Panchen Lama and the Bhutanese Deb Raja; however, by the first part of the nineteenth century, the status of the 1774 treaty was unclear. The reference to friendship in the treaty was the result of a personal connexion forged by Bogle and carried no meaning, beyond the strategic commercial ends of both parties, when confronted with intervening outside powers.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, further British missions and envoys went to Bhutan (especially Bose and Ray in 1815, Pemberton in 1837–38, Eden in 1863–64) and a complex process of frictions and negotiations over the fertile borderland areas of the south culminated in the loss to Bhutan of first the Assam Duars, and then the Bengal Duars. The climax of this was the second Anglo-Bhutanese War in 1864–65, following the failed Eden mission. At the conclusion of this war, following the Duar annexation and the Eden mission, a treaty was signed (the 1865 Treaty of Sinchula, also known as the Ten Article Treaty of Rawa Pani). Friendship, in the contemporary political sense, is at first a product of this encounter. While the May 1774 treaty was conducted to conclude the hostilities between the “Honourable East India Company and the Deb Raja of Bhutan,” and though it mentioned peace in passing, it mainly concerned itself with trade and other commercial issues. By contrast, the 1865 treaty designation recognised a “Government of Bhootan” that could deal with the “British Government.” Signed on 11 November 1865, this treaty had as its first article the words, “There shall henceforth be perpetual peace and friendship between the British Government and the Government of Bhootan.”Footnote 33

The usage of the word friendship in this treaty notwithstanding, in its aftermath Bhutan saw the loss of its most fertile land and the creation of a subsidy relationship with Britain. The British paid an annual subsidy, which was fixed at a sum, and did not rise proportionally to the increasing value of the land. This last aspect is crucial, and recent critical scholarship based on archival work links this directly to the careful deliberations on the part of administrators such as Cecil Beadon, amongst others.Footnote 34 The annual subsidy was fixed whereas the cultivable land, which was to be used for tea plantations, increased greatly in value each year. The 1865 treaty was followed by severe hardship for the Bhutanese in the intervening years up until the first part of the twentieth century. It further paved the way for intervention through the use of subsidy as an instrument to exercise control. For instance, Article 5 of the 1865 treaty stated, “The British Government will hold itself at liberty at any time to suspend the payment of this compensation money either in whole or in part in the event of misconduct on the part of the Bhootan Government for its failure to check the aggression of its subjects or to comply with the provisions of this Treaty.”Footnote 35

Until the start of the twentieth century, friendship vocabulary was used in treaty-making but with no normative content; it was only later that a more effective use was made of friendship as part of the political arsenal of diplomacy. Following the Younghusband expedition of 1903–4 to Tibet, and the Bhutanese assistance afforded to it, especially by Raja Ugyen Kazi (Dorji) and Ugyen Wangchuck (later made Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire and installed with British approval and local support as the first hereditary monarch in 1907), the 1865 treaty was updated, with additional and amended articles, as the 1910 Treaty of Punakha. While there had been commercial reasons to make a reference to friendship between the British governor-general and the civilian ruler of Bhutan (Deb Raja) in 1774, and the reference to friendship was used to settle political disputes using financial means in 1865, as I explain here, it is really in the 1910 treaty that we see a mix of strategic and normative friendship as a method of achieving political control.

Scholars of the Himalayan region mention the 1910 treaty as a fact in a narrative sequence of historical developments;Footnote 36 work so far has assumed the imperial imperative of such a treaty to be obvious, and neither analysed the ways in which this treaty came about nor subjected the treaty to any critical examination beyond stating its execution and clauses, or repeating the public rationale provided by its chief architect, Political Officer Bell, in his 1924 book.

I argue that a focus on this treaty is important for the following reasons. First, the execution of the treaty in 1910 comes at a watershed moment. Historiography on Bhutan is often divided into the periods 1772 to 1910, and then 1947 onwards; 1910 and this particular treaty marks a turning point, at a time when British Indian, Qing Chinese, and Tibetan contestations and wider changes in the Himalayas are especially predominant.Footnote 37 Armed Chinese troops marched into Lhasa on 12 February 1910,Footnote 38 just a month after the Treaty of Punakha was signed in Bhutan on 8 January 1910. Second, the 1910 treaty is the first significant international document signed in Bhutan after 1907, the year when an elected hereditary monarchy was installed in Bhutan through the means of a historic Gyenja (agreement), a document containing the seals of its provincial chiefs.Footnote 39 In the efforts to secure the treaty, the British had further set in motion modern state-making processes in Bhutan. For instance, in order to get valid and informed consent of the Bhutanese representatives, the treaty signing had included a seal of approval from chiefs throughout the country. Thus, unlike the eighteenth-century trade and commerce treaty or the nineteenth-century cessation of hostilities treaty, the 1910 treaty was signed in the name of a government and contained assent from the monarch, the regional governors, and also representatives of the religious monk body, which has an important role in the country.Footnote 40 Third, the 1910 Treaty of Punakha is significant to analyse in terms of the events and the calculations that led up to it, because this treaty inserted a particular clause in Bhutan's international relations for the first time in 1910. According to this clause, Bhutan agreed to be “guided by” Britain in the conduct of its external relations. This set the tone for the understanding of friendship in the bilateral relationship throughout most of the twentieth century, and paved the way for an enduring discourse of friendship under asymmetrical conditions of power. This clause was retained in the 1949 treaty between Bhutan and India and was not finally repealed until 2007. Fourth, while the existing references to friendship in the Bhutanese context almost exclusively concern themselves with Indo-Bhutan friendship, and specifically the treaty of 1949, this treaty of 1949 was an updating of the 1910 treaty between Bhutan and Britain with its substance intact,Footnote 41 and the 2007 updating of the 1949 treaty also carried it forward except cancelling the key clause that actually originated from the 1910 treaty—a clause that required Bhutan's external relations to be “under the guidance” of the British, and promised non-intervention in internal affairs in return. Therefore, the 1910 treaty is an important milestone that deserves greater understanding and analysis than is afforded in existing scholarship. Fifth, ambiguous interpretations were rife when it came to understanding the implications of the 1910 treaty. As I explain later, its key architect on the British side—Political Officer Charles Bell—saw it as having incorporated Bhutan into the British Empire; the other British administrators of the Empire were far from convinced that this was the case; the Bhutanese regarded it as a mutually beneficial arrangement with a Great Power that did not impinge on their sovereignty, since in their view Bhutan was bound to seek, but not necessarily to agree with, the “guidance” provided. This article draws upon original archival research in order to make these arguments in greater detail.Footnote 42 Finally, as previously mentioned, focusing on the treaty also allows highlighting the complexity and context of the discourses of friendship as they play out in the divergence revealed here between the treaty motives and advantages that Political Officer Bell lists in his 1924 book as opposed to in his 1910 report in the archives.

In order to fine-grain our understanding of friendship as a device of diplomacy in the Himalayas in the context of Bhutan's 1910 treaty, there are three broad and key themes to identify as they arise at the start of the 20th century—the role of individual friendships in creating the discourse of friendship between larger collective entities under unequal conditions of power; the construction of anxieties about a potentially or actually hostile Other that can be managed through the friendship; and the representation of material and ideational advantages to be gained from the relationship of friendship. The second and third aspects here are interrelated in terms of reinforcing the mutual coincidence of needs and interests that can be served by the friendship. All these three factors were in play at the start of the twentieth century in relations between British India and Bhutan. I refer to them in turn.

1910 Treaty Factors: Personal friendships, hostile Other, representation of advantages

The 1910 treaty signing on 8th January of that year, was preceded by the personal cultivation of a friendship between Political Officer Claude White (whom Bell succeeded)Footnote 43 and Ugyen Wangchuck, the first king of Bhutan. The beginnings of a productive usage of a vocabulary of “friendship” can be traced to the imperial diplomacy of White who referred often to his “friend” Ugyen Wangchuck. His desire was to use friendship as a means of securing Britain's influence in Bhutan; as he explained, this would serve several purposes:

For the last hundred years till quite lately the governing body in India has endeavoured to keep strictly, and even contemptuously, aloof from these mountain people, and that their policy of refusing to sympathise or hold friendly intercourse with them has invariably resulted in trouble and annoyance to themselves, in return for which they have enforced full payment by depriving the weaker State of valuable territory. It is obvious that in the case of Bhutan, Government should utilise this unique opportunity of a new regime in that country to enter into a new Treaty and to increase the inadequate subsidy that we now dole out as compensation for the annexation of the Duars, the most valuable tea district in India. If this is not done soon China will acquire complete control in Bhutan, and demand from us . . . the retrocession of the Bhutanese plains. Further, any political disturbance on the frontier would seriously affect the supply of labour on the tea gardens . . . and so cause great loss to the tea industry . . . [it] is to be hoped that we may not drift into a similar situation [as of Nepal] with Bhutan . . . constant and continued intercourse with our frontier officers should be encouraged, and a policy closely followed by which no efforts to further and advance friendly and intimate relations are spared.Footnote 44

For White, and for British imperial policy in general, friendship meant an effort to engage with the other party to preserve and promote self-interest and keep out undesirable influences; nonetheless there was also a personal element in the serious cultivation of trust through normative friendship between individuals. Not only had White conducted friendly intercourse with Ugyen Wangchuck through repeated visits before 1910, including prior to 1907 (the year when an elected hereditary monarchy—the Wangchuck dynasty—was established in Bhutan on 17th December), the Political Officer Charles Bell (who conducted the treaty negotiations in the run up to 1910 on behalf of the British) had also taken care to cultivate a personal relationship with Ugyen Dorji (Rai Ugyen Kazi Bahadur), who was a key intermediary and a friend of Ugyen Wangchuck.Footnote 45

Once Bell received the go-ahead for the treaty alteration,Footnote 46 he sent for Rai Ugyen Kazi Bahadur “because his present influence in Bhutan is great and because his interests are for various reasons bound up in our own.”Footnote 47 The coincidence of interests between Kazi Ugyen and the British was not accidental or spontaneous. This had been gradually but systematically brought about over the period since 1880s. Kazi Ugyen had a long association with the British, especially since the first political officer was appointed after the Anglo-Sikkim war in late 1880s. Bell had been paying particular attention to Kazi Ugyen for some time before 1910. He wrote, “I have been especially careful during the last two years to humour his somewhat uncertain temperament so as to have him in good train for this work.”Footnote 48 Bell also made sure to create goodwill through medical aid and other such means.Footnote 49 He requested that Captain Kennedy of the Indian Medical Service (IMS), who was the medical officer at Gyantse, should accompany him on the treaty revision mission and “distribute medical aid as we passed through the country.” This was an enhanced use of medical aid—White in 1905 had not gone with an IMS officer.Footnote 50 This initial deepening of relations at the start of the twentieth century was to remain an important trope that continued to be rehearsed by later British authors who stressed upon the natural affinities between the British and Bhutanese.Footnote 51

Gift-giving too was central to the creation of goodwill and the public performance of friendships. The political officers' reports over the years would typically provide the expenditures on transports, presents, entertainment, medicines, liveries, mess, camp furniture, tents, miscellaneous. In 1912, Bell proposed a tour to Bhutan (where he had not been since 1910), and in order to persuade his seniors, he gave details of outlay on his proposed tour as compared to the previous tours by White in 1905 and 1907 (the 1906 visit being ‘unofficial’) and his own tour in 1910.Footnote 52 From this source, I have extracted and collated the data below to demonstrate how the expenditure on gifts as a proportion of the total spent changed in the various years. A glance at these figures shows how large the outlay towards gifts is, especially at key moments such as installation of the monarchy in 1907 or treaty signing in 1910. For instance, in terms of the cost of presents alone: White in 1905 spent 8,570 rupees, Annas 9, Paisas 8 on gifts (out of a total cost of 11,365 Annas 13, Paisas 11); White in 1907 spent 14,111, Annas 12, Paisas 5 rupees on gifts (out of a total cost of 18,932, Annas 2, Paisas 10); Bell in 1910 spent 8,903 rupees, Annas 10—not including arms and ammunition— on gifts (out of a total cost of 9,580). Thus, in the treaty year of 1910, Bell's spending on the visit is almost exclusively on gifts; as proportion of total spending, it is higher than what White spent in 1907 at the time of the installation of the monarchy. However, this trend did not continue after the treaty signing; for instance, in 1912, Bell proposed a greatly reduced estimated spending of 4,000 rupees (out of a total cost of 6,000 Rs).Footnote 53

Around this time, it was also important to confer distinctions and rewards upon the Bhutanese elite who had assisted with the 1910 treaty negotiations and to impress upon the Bhutanese leadership that they had made the correct choice by agreeing to the treaty. An expenditure of 10,000 rupees was sanctioned in 1911 to enable the Maharaja of Bhutan to attend the Delhi Durbar.Footnote 54 Ugyen Kazi received an increase in pay for his help with having “rendered exceptionally valuable assistance towards its [treaty] conclusion.”Footnote 55 Ugyen Wangchuck himself requested the British government in a letter to Bell to grant Rai Bahadur Kazi Ugyen a title, saying:

He has arranged friendly relations between the British and Bhutanese Governments from the beginning up till now. He has very industrially and faithfully served the British Government and therefore he was given a Jongpenship here. Now as I have become Maharaja I am appointing him as Deb Zim-pon, the most important post under a Maharaja. This is partly because he has to go to places where many people assemble. In future also he will be a man partly under the British Government and partly under the Bhutanese Government. He will serve the British Government faithfully as before. Therefore I would request you, my friend, to help him as much as possible, that he may be given a title under the British Government.Footnote 56

A second factor used by the British to bolster treaty negotiations was the cultivation of anxieties about a potentially hostile Other, one who could be managed through friendship between Bhutan and Britain. This was, and still continues to be (for the successor state of post-colonial India), the “fear of China” factor. On the very first page of Bell's 1910 treaty report listing treaty advantages, he states, “By obtaining this control over the external relations of Bhutan we have removed the Chinese menace from some 220 miles of a very vulnerable frontier.”Footnote 57 The British saw Tibet as a big buffer and Bhutan as a small stronghold against the gathering forces in Russia and China. The so-called Great Games in the early decades of the twentieth century were essentially a proto–Cold War, when the imperial powers first recognised the Russian and Chinese threat to bourgeois capitalism. The Punakha Treaty gave the British the right to settle any disputes in the fertile areas of the lower boundary region of Bhutan where British commercial interests (tea, trade revenue, or other cultivation) were involved. It gave them access to any facilities or land in case of need. It meant that the contacts between Bhutan and Tibet could be lessened with British guidance. It meant China could be shown that Britain was almost suzerain over Bhutan and the British had their commercial interests—trade routes and fertile areas—secured. The vocabulary of friendship was an excellent diplomatic tool that achieved a lot for Britain at little cost.Footnote 58

The altered treaty gave the British significant influence in and over Bhutan vis-à-vis China; an influence they moulded to their advantage. The fact of “tea politics”Footnote 59 was a big advantage to British—and later, Indian—capitalists who were heavily invested in the region. The economic carte-blanche Bell gained with the treaty, including the promise of any land anywhere in Bhutan (this must have been very useful for subsequent work of boundary demarcation and realignments), any help of any kind affordable by Bhutan, the possibility of a road to Tibet if required, the possibility of stationing an Agent if required, the possibility of mining and forestry exploitation (presumably as development assistance)—was immensely advantageous and it worked in the joint interests of British and Indian trade.Footnote 60 It is not entirely surprising then that the subsequent economic dependence has transformed Bhutan—which Bell celebrated as “a fertile country” that he feared “when developed [is] capable of supporting about one-and-a-half million persons by agriculture . . . could then feed a large army of Chinese troops without difficulty . . . Chinese soldiers are rice eaters”Footnote 61—today into a country that imports rice from India.

On the basis of Bell's treaty report, we can categorise his original list of advantages to the British following from the Treaty under four main types that relate to: dealing with China; economic and commercial matters; low cost of treaty transaction; and increased pride. The role of China as Other plays an especially important part. For instance, Bell writes that owing to the British policy of withdrawal from Tibet, Britain's prestige had been lowered in Bhutan and China's had risen greatly. Because of this, “there was a danger that Bhutan might have rejected Britain's wish to control her external relations from fear of China.”Footnote 62 The new treaty removed that danger. He also draws attention to the fertility of land for agricultural cultivation in Bhutan (as opposed to an infertile Tibet), and as mentioned above, the worry that Chinese soldiers (being rice eaters) might select Bhutan for Chinese colonisation. Moreover, he was of the view that the Nepalese population in Sikkim and Bhutan was rapidly increasing, and it was important to keep the entire Nepalese population of these parts under British control. Command over the external relations of Bhutan would keep the natural affinities of co-religionists in Tibet and Bhutan under check. Not only would the treaty guard against “Chinese designs on Bhutan,”Footnote 63 British influence in Bhutan would also prove useful in the event of a campaign in Tibet. The British fear of China at this time coincided with an assertion of Chinese nationalism due to the nearly collapsed Manchu imperial regime and a resurgent anti-colonial nationalism in China. After the treaty was concluded (it was ratified on 24 March and published on 26 March 1910), British and Chinese correspondence about Bhutan continued, with China objecting to the treaty, until 1912.

The creation of concrete ties of a friendship treaty between Bhutan and Britain resulted from the cultivation of personal friendships and the calculations of strategic advantage, in order to ward off the threat from an Other. A third factor vital in the treaty realisation was the creation of a discourse of a mutual coincidence of interests between Britain and Bhutan; this involved the representation of various material and ideational advantages to Bhutan from associating with the British. The proposals that Bell had made about revising the 1865 Treaty of Sinchula with Bhutan formed the recommendations of the Government of India, which the secretary of state accepted. Bell's proposals to revise the 1865 treaty into the 1910 treaty had comprised two specific things, and in the official correspondence he was clear that one of these two stated objectives was much more important than the other. He wrote:

(a) The Treaty should be revised so as to place the external relations of Bhutan in the hands of the British Government. For this the Bhutan Government was to receive a guarantee of non-interference with their internal affairs an and increase in the annual subsidy by half a lakh or by any sum up to one and-a-half lakhs, if necessary.

(b) We should assist in her industrial development.

Of these two objects (a) is by far the most important.Footnote 64

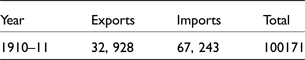

The advantages projected to Bhutan by the potential treaty came at a significant time for the Bhutanese. 1909–1910 was a relatively bad year financially for trade between Bhutan and British. I present the comparative figures below. This is the data for the trade between Bhutan and British India, during the nine months ending in December for each of the years. Since the foundation of the hereditary rule in December 1907, this was the worst trade statistic for Bhutan-British India trade; both exports and imports had gone down significantly so that the total figure was only about 2/3rds of what it was in 1907–08 (the harvest in 1909–1910 was a normal crop).

Yet, in the annual report (1910–1911) of the year following the 1910 treaty, trade declines still further,Footnote 65 and it is simply noted that the “trade of this interesting country is capable of very great development,” which it is hoped “will be steady, but not rapid.”Footnote 66

The objective of Britain assisting Bhutan's industrial development (second objective in Bell's proposals) was not important to the British; nonetheless, it played a role in persuading the Bhutanese. In addition, the Bhutanese were given an impression of some sort of protection, which was not however put into writing.

Prior to the treaty signing, Bell informed Kazi Ugyen (Ugyen Dorji) that if at any time Bhutan needed assistance against external enemies, “the British Government would give it such assistance as the British Government might deem necessary.”Footnote 67 Ugyen Kazi wished this to be entered in the treaty, but Bell “persuaded him that it was undesirable.”Footnote 68 The promise of industrial development assistance and assistance against external enemies, even though they were not put into writing, gave the Bhutanese a sense of common cause and support. As per Bell's report, his assurances were conveyed on to the king by Ugyen Kazi who explained to the Maharaja (Ugyen Wangchuck) the advisability of accepting the British terms; Ugyen Kazi also collected the councillors at Punakha to persuade them about the alteration. When Bell arrived in Punakha on 7 January 1910, the council members were all there with the necessary seals, but some (such as the Paro PenlopFootnote 69) “were very doubtful.” Upon receiving Bell's copy of the new treaty “in English and Bhutanese,” they were initially unsure: “The Council members were adverse to the clause placing the external relations of Bhutan under the British Government fearing that loss of independence would result, but their scruples were overcome.”Footnote 70 The appeal to friendship had allowed several successful instances of “persuasion” to achieve the desired British aims.

Bell, in his own words, had energetically managed to “incorporate Bhutan into the British empire”—he specifically states in the report: “By one O'clock the signing and sealing were finished, and Bhutan was incorporated into the British Empire.”Footnote 71—but the Bhutanese saw themselves as independent. While other officials might disagree about what the exact status of Bhutan was within the British empire—whether it was a native state, an independent state, or a vassal state (in most cases the ultimate consensus was: let us simply not bring up this question in the open)—this did not hamper the British from inviting the Bhutanese to pay their respects alongside native chiefs at Durbars. We can perceive this strategic use of ambiguity along the lines of what Dibyesh Anand terms “strategic hypocrisy” in how the British scripted the geopolitical identity of Tibet (British suzerainty/Tibetan autonomy).Footnote 72 British officialdom wanted to keep Bhutan nominally sovereign but actually functioning as a vassal state. It was not to be strictly a neutral buffer because the treaty would align it to the British empire in India.

The treaty of 1910 was unfair to Bhutan in many ways and this became most apparent in the later twentieth century as Bhutanese state-making progressed. Over the decades, the government's responsibilities towards its citizens and the people's expectations of their country expanded, thus creating a continuing difficulty navigating internal political, economic, and social issues within the country, without being able to shake off the stifling encumbrance of a friendship that denied the exercise of an entirely free foreign policy. The guidance clause was retained in the 1949 friendship treaty with India, exacerbating these problems in the later twentieth and early twenty-first century. Even when the clause was finally removed in the treaty updating of 2007, the friendship treaty is still brought up at any hint of Bhutan's engagements with China to resolve boundary disputes.Footnote 73

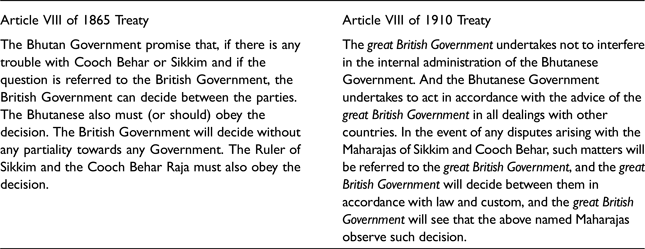

The representation of ideational advantages to the type of friendship enabled by the treaty continued to be salient. In the exercise of securing power, prestige was an important motive. The British paid attention to maintaining stable and continual relations with important subsets of the Bhutanese elite, including mentoring patterns of education and marriage. Bell saw the Bhutanese as proud British subjects, and other officials saw the Bhutanese as subjects who “might” be proudly British subjects whether they were officially so or not. The British stress on identifying themselves with the Bhutanese elite was, however, superseded by their own pride in their status as a superior power, as confirmed by the treaty alteration. In his treaty report, Bell gives as Appendix I the comparative literal translation of the Bhutanese version of the amended Article VIII of the 1865 Sinchula treaty and 1910 Punakha treaty.Footnote 74 I place the two versions of the same article side by side to call attention to a striking semantic fact. The insistent repetition of the “greatness” of the British government in every line of the paragraph indicates a clear desire to impress upon the negotiating partners that the British government is a great government whose judgement is unquestionably final and who will enforce its decisions.

Giving favourable impressions of the British to the Bhutanese was vital to enact prestige even after the treaty was signed. In the discussions on file in 1911 on whether the Maharaja of Bhutan should be invited to Delhi as suggested by Bell, the official A. H. McMahon weighs the pros and cons of this proposal.Footnote 75 McMahon refers to Bell's request about this invite from the previous year (1910) and notes that Bell was very keen to have the Maharaja invited to Delhi to “see some concentration of troops, in order to impress him.”Footnote 76 Bell was told such a visit was unnecessary as the Maharaja “would no doubt be invited to the Delhi Coronation Durbar.”Footnote 77 Subsequently, it was decided that “only Indian States, &c.” will be invited and by the “strict letter of this decision Bhutan would be excluded.”Footnote 78 However, McMahon goes on to note that:

The position of Bhutan, however, is somewhat ambiguous, and it would be easy to treat it, if we wish to, in this connection as one of the Indian States like we do its neighbour Sikkim.Footnote 79

The practicalities were feasible and he would “be treated as a 15-gun Chief at Delhi.”Footnote 80

It is merely a question whether for purposes of impressing the Maharaja and of manifesting the fact that we regard Bhutan to all intents and purposes, as an Indian State, we depart from the strict letter of the recent decision or not. Mr. Bell, his Political Officer, is evidently anxious that we should.Footnote 81

The other alternative was to invite him to Calcutta to meet the king there. But this was rejected as it “may prove inconvenient and might give him and others a mistaken idea of his status.”Footnote 82 McMahon ultimately decided that of the two proposals, “the former attains more political results with the less trouble.” Another official Harding on 11 March 1911 was more forthright: “As we claim to be the Suzerain Power and as we direct the foreign relations of Bhutan, I think it would be a good thing from a political point of view to invite the Maharaja to Delhi and to provide him with the necessary means for so doing. It will be an object lesson to the Chinese who have shown themselves aggressive regarding Bhutan.”Footnote 83

We might ask why Bell was so keen that the Maharaja attend the Coronation Durbar in Delhi. This can best be assessed from his 18 February 1911 letter to the Secretary to the Government of India in the Foreign Department. Bell wrote:

In ordinary circumstances one would, of course, leave the Maharaja to attend the Durbar or not, as he liked, and to find his own way there as best he might. But we want his presence at Delhi for two main reasons:

(a) Because it will be a token of his subordination to His Majesty the King-Emperor and another argument against the Chinese claim to suzerainty over Bhutan. The importance of this need not, I think, be urged on the Government of India.

(b) Because it will show him a large number of British and Indian troops and impress him still further with a sense of our power. Stories of so many lakhs of soldiers effect nothing, but seeing the men on the ground carries belief and the Maharaja of Bhutan is quick to learn lessons of this kind.Footnote 84

Bell's friendship, like that of White and many others, had been an instrument for securing political control over Bhutan, but it also presented intentions that tied in well with traditional virtues and values of societies who understood friendship in a different way and with a greater moral imperative. This friendship embodied a performative naming into the future; a hope for and against certain kinds of behaviour on both sides. Bell noted in his next annual report: “His Highness paid his homage to the King-Emperor with the other Ruling Chiefs on the 12th December 1911. . . . He informed me most of all he enjoyed the military review. All matters connected with the soldiery attracted his close attention.”Footnote 85

Through the friendship treaty, a fundamental status anxiety had been introduced into the bureaucratic and official circles about the position of Bhutan. In 1911, the Maharaja of Bhutan (Ugyen Wangchuck) wrote to the Chinese Amban in Tibet for the restoration of certain lands belonging to the To-lung Tsur-po Monastery, one days’ journey from Lhasa, whose lands had been taken by the fifth Dalai Lama some two hundred years ago. The Maharaja was worried that in case the thirteenth Dalai Lama returned to Tibet from self-imposed exile, he might punish the monastery still further as the Amban had been asked by him for a return of the lands. Would the British be prepared to support him? Bell forwarded the query on to the Government asking how they felt about the “protection of Bhutanese interests in Tibet.” The Maharaja, who in 1909 had been prevented from going to Lhasa by ill-health, had journeyed nineteen days to the Durbar in Delhi, spent 20,000 rupees of his own money, and “tendered his homage” to the King-Emperor—should he be supported in this matter if the need arose? Bell understood this and thought, at least in theory, that the answer ought to be a yes, even if “we need not consider the nature of this support, unless and until the contingency, which is feared, has arisen.”Footnote 86

In the discussions on file in response to Bell's query, officials consider whether Britain “could, or should, protect Bhutan in Tibet” and relate this to whether “the Maharaja ought to have addressed the Chinese Amban direct in the matter.”Footnote 87 It is pointed out that the friendship treaty did not mark a departure from the settled policy of His Majesty's Government upon the Indian frontiers, which had been stated previously as being “to undertake no extension, direct or indirect, of the administrative responsibilities of the Government of India.”Footnote 88 An official signed as T. W. (dated 17 January 1912) wanted to wait and watch, being of the opinion that Bhutan and Tibet have close religious and other links, so this policy ought not to be strictly interpreted, and in any case, “no action ought to be taken at the present on Mr. Bell's letter” except copy it to Army Department and India Office for information.Footnote 89 Another official, E. H. S. Clarke (dated 17 January 1912), made the cynicism clearer:

I think it will be well not to attempt to settle the question as to how far we should support Bhutan in a matter like this, until we are compelled to do so. A good deal would depend on the general political situation in Tibet at the time. But I do not think the Maharaja of Bhutan should have gone behind our backs, begging the Chinese Amban to restore lands which were taken from the Bhutanese Monastery near Lhasa by a Dalai Lama two centuries ago. If he does this sort of thing, we cannot be surprised that the Chinese insist on corresponding direct with him, and treating him as a subject of China.Footnote 90

The Additional Secretary to the Government of India in the Foreign Department, J.B. Wood (dated 18 January 1912) concurs, remarking: “It is strange that Mr. Bell did not notice the point.”Footnote 91 The ambiguities about the extent of responsibilities and the boundary lines in friendship as a concept in action are mirrored in the exact legal status of Bhutan in relation to the British Empire; officials were divided about what weight to place on Bell's language in the treaty report. Opinions varied as to whether the language was “metaphorical” or whether it was “strict” but “meant in the ‘forward’ sense.”Footnote 92 One notation expresses a puzzling question: “The Bhutanese are ‘incorporated in India,’ ‘subjects of British Empire’—yet we [are] not to meddle in their internal affairs?”Footnote 93

The British never did have to be explicit about how far they would support Bhutan in any final sense. As the above suggests, they saw themselves as the de facto suzerain power over Bhutan but were aware that this was not legally or materially demonstrable, so they did not make it an overt assertion in spite of operating on this understanding amongst themselves. Later, Indian officials often operated with a similar understanding of Bhutan's status. The treaty of 1949 replicated the terms of the 1910 treaty with increased subsidy and some land restoration. This status anxiety continued to manifest itself in the 1949 treaty conditions and in the way initial maps were drawn in independent India; it found an expression in the way many in the immediate neighbourhood and beyond saw Bhutan. Once the treaty of 1910 was achieved, the British interest in Bhutan was keeping and nurturing useful relationships and making sure that Bhutan remained isolated from contact with anyone else. Ironically, however, this policy of Bhutanese isolationism coupled with the institution of an elected and stable hereditary monarchy was eventually to prove helpful in the consolidation of Bhutanese identity, and important for preserving the sovereignty of the country in the postcolonial era.

Conclusion

As a key instrument for realising friendships between states, treaties are, and have been, important, and it is vital to illuminate the provenance of contemporary treaties by placing them in their historical context.Footnote 94 Most work on the politics of friendship treaties focuses on the global West; outside of Europe and the Americas and their treaties with domestic indigenous populations, the focus is often on Soviet alliances in the Cold War, or on Chinese treaties. Not only do the friendship relations pertaining to non-Western countries have occasional walk-on parts in these discussions, there is hardly any work that brings together archival history and international relations to analyse friendship treaties in the context of the Himalayan region, and any reference to a country like Bhutan is completely absent. Even specific overviews of global treaties neither mention nor consider Bhutan's treaty relationships.Footnote 95 Within the political history of the Himalayan region, the reference to friendship does not connect with the literature on the politics of friendship, and explicit mention of friendship only finds a place in work on the post-colonial era in the second half of the twentieth century with Nehru and India's foreign policy in the region and beyond,Footnote 96 or in relation to the Sino-Indian rivalry.Footnote 97 However, the complex friendship relations, both between larger and smaller, current and erstwhile, Himalayan states, have a much longer provenance. I propose that more historical work on friendship (and what it made possible and how) is necessary to detail a richer empirical recognition of current complexities in the Himalayan region. This includes attending to the longer archival records of imperial strategies and alternate and varied perceptions of friendship, such as was the focus in this article, as well as building upon existing work on the customs of gifts, diplomatic mediations, aristocratic and hereditary positional salience in indigenous diplomatic networks, the impact of the individual personalities of officers, and the personal friendships between prominent indigenous leaders and frontier officials.Footnote 98 Conceptualising friendship in the politics of the Himalayan region is potentially a polyvocal practice; it can range from attending to the superficial uses of the rhetoric of friendship in political contexts to concentrating on the deeper ways in which individual friendly relationships are constituted and practised and how they shaped the wider politics.

The British friendship treaties with smaller non-Western polities in the imperial era were evidently a modality of indirect governance and an instrument of control, but they were also relationalities that reflected how the larger imperial structures at the frontier were negotiated by these individuals in ways so that no particular political outcome was ever really inevitable, but contingent upon the specific constellations of factors. In other words, personalities mattered as much as policy.Footnote 99 Individual officers as the face of empire and officialdom in the Himalayas mediated imperial power at the frontiers, and there were pragmatisms, exigencies, and perceptions at play in these tensions.Footnote 100 But equally, the frontier officials also made new relations of power come into being through the economic, cultivation, or taxation changes they facilitated; for example, Political Officers White and Bell introduced many economic changes in the eastern Himalayan region,Footnote 101 in addition to the friendship treaty relationships that they accomplished. These changes effected transitions of political orders in the region through creating new domains of legal and other authorities, and in all this, the personalities and personal friendships played a key role in establishing the shifting lines between strategy and sympathy.

Moreover, the unintended consequences of such treaties were hard to predict. In the 1910 treaty analysis I have presented here, we find the coming into being of a pact of ambiguity about political status that is sealed by the vocabulary of friendship in terms of advantages and threats both. The British had ensured that the monarchy had been installed in Bhutan in 1907 and prior to 1910 and Political Officer Bell had made every effort to achieve a treaty with the signed and sealed consent of the “government” of the country. His view was that this treaty incorporated Bhutan into the British empire, but the treaty also gave on the part of the British an undertaking not to interfere in the internal affairs of Bhutan. As I have shown, Bell's logic was not shared by other officials and while this strategic ambiguity was useful for the imperial British, after a few decades, it was this treaty-induced ambiguity that was one of the factors that may have contributed to the preservation of Bhutan's sovereignty in the post-colonial era when Sikkim and Tibet became absorbed into India and China respectively. The 1949 treaty of Bhutan with India carried forward not just the substance of the 1910 treaty, but also the dynamics under which the treaty was signed, that is, the role of the Political Officers with their interpersonal friendships and the constant rehearsal of friendship vocabulary at the level of the countries alongside a variable reality of what that friendship entailed on both sides.

As the foregoing demonstrates, the study of friendship in its various dimensions for the political history of the Himalayan region more broadly, and Bhutan specifically, is part of a wider research programme that imbues the geopolitical abstractions of state alliances and foreign policies with the enfleshed, encultured, experienced, and situated rationales of affect in the efforts undertaken by individuals who are freighted with desire, fear, threat, expectation, and reciprocity in how they perceive and negotiate the structures of political power. The empirical work adduced here on the motivations, precursors, and conditions under which international friendship is actuated in practice also serves to complicate any neat analytical distinction between strategic and normative international friendships. Friendship between people, when understood in its classical sense, indicates an accountlessness and a mutual consideration. Between nations, it serves the additional valuable purpose of reconciling frictions within an overarching ethical framework. Many things can be forgotten between friends that neighbours might otherwise remember. The discourse of friendship serves a purpose in spite of size and power differences; it can be a performative naming into the future that realises an aspiration or tides over conflict. More work in the context of friendship in the Himalayas between imperial, postcolonial, and non-western countries of asymmetrical size and power will help us in further illuminating the diversity of rational and relational means through which state-making, sovereignty-preservation, and foreign policy proceeds. In doing so, we can also better understand the role of affect in geopolitics, perhaps even ask: What can friendship come to mean in the relations between nations? Do different understandings of friendship lead to differing expectations? Can enduringly maintained friendships permit learning and do they teach states to do better?

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors and reviewers of the journal, and especially thank Charles V. Reed for helpful advice and suggestions. I would also like to acknowledge the research support at different times for my Bhutan-related work (2006–continuing) from the University of Westminster, the British Association for South Asian Studies, the British Academy, and the Arts and Humanities Research Council.