Introduction

The chain of delegation linking public priorities to government's policies is affected by several divergent factors, which intervene at different moments and levels. In this chain, somehow in-between citizens and governments, there are parliaments, constituting both a filter and a control mechanism. Several factors intervene in shaping the parliamentary agenda of parties and members of parliament (MPs), such as new public concerns, the mediatic agenda, and external events (Froio et al., Reference Froio, Bevan and Jennings2017). This article aims to assess the impact of various crises on two distinct types of parliamentary questions. These question types are characterized by varying levels of institutional friction. The primary objective is to determine whether and to what extent the dynamics within two parliamentary venues are governed by similar underlying logics.

The agenda-setting literature has dedicated much attention to the degree of responsiveness expressed by political institutions in different activities – or policy venues – such as parliamentary questions, legislative proposals (bills) or budgets. The general finding is that the degree of issue responsiveness depends on the level of friction to which each venue is subject (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2004; Bevan and Jennings, Reference Bevan and Jennings2014). Frictions can be seen as the institutional barriers preventing political actors from reacting quickly to changing inputs. For instance, asking a parliamentary question is indubitably easier than changing the budget, and this explains why the policy agenda of parliamentary questions is much more responsive to external inputs than that of public expenditures. At the same time, we know that although institutional frictions are powerful at hindering policy change, their effect can be substantially placated in periods of crisis. Those moments possess the ability to make the agenda concentrating on the crisis issue, creating more favorable conditions for attention shifting (and policy change) even in the presence of high institutional frictions (Borghetto and Russo, Reference Borghetto and Russo2018; Cavalieri and Karremans, Reference Cavalieri and Karremans2024).

One limitation of the agenda-setting literature is that different forms of parliamentary questions are often treated as having a single logic and dynamic (among others, Vliegenthart and Damstra Reference Vliegenthart and Damstra2019). In fact, legislative studies show that all parliaments have different procedures at their disposal to ask questions to the government, and each activity has its own (formal and informal) rules: for instance, there are procedures which are particularly useful to seek information and others which are better suit to publicly criticize the government (Russo and Wiberg, Reference Russo and Wiberg2010). We suspect that dissimilarities among parliamentary questions considerably affect the extent to which – and how – parties and single MPs exploit them to show responsiveness to the public. As frictions are extremely variable among different forms of parliamentary questioning (Sorace, Reference Sorace2018), we argue that this institutional richness is instrumental in creating multiple channels of issue responsiveness.

Studying the dynamic of the policy agenda during crises represents the least likely case to find a difference between different forms of questions, because crises are by definition moments in which the pressure for political actors to show responsiveness is at its maximum and able to overcome the resistance of frictions. Showing that different kinds of parliamentary questions obey different logics we can confidently conclude that agenda-setting scholars need to carefully discuss their institutional features before analyzing them. Likewise, legislative scholars should recognize that each of them offers a peculiar channel to issue representation.

To investigate these matters, this study compares the determinants of issue attention for crisis-related issues in the Italian case, comparing their impact on written questions and oral questions with immediate response, two forms of questioning regulated by extremely different rules which make them adapt to different purposes. Specifically, we study how different signals (real-world indicators, public opinion, and the news) were reflected in the issue attention attributed to the economic, pandemic, and migration crises, which in Italy manifested with particular severity. By looking at how different crises received attention in two parliamentary venues, the article is not only theory-testing but also has an important exploratory and theory-generating component.

The paper proceeds as follows: the second section reviews the main threads of research about crises, parliamentary venues, and responsiveness. The third section explains the case selection and the fourth section develops the hypotheses. We describe and compare the dependent variables in the fifth section, which allows us to test our first hypothesis and in the sixth section, after describing the independent variables and the method used, we test four additional hypotheses and present the results. We conclude by discussing the implications of our study.

Crisis, venues, responsiveness

Issue responsiveness in normal times and during crises

Understanding which issues gain or lose traction in the political agenda is a crucial task for scholars of public policy and political science. As the first step of the decision-making, the process of agenda-setting has a relevant role and powerful effect on the production of public policy.

When looking at issue-responsiveness – the degree to which the issues debated by political actors mirror those citizens care about – the most general finding of agenda-setting studies is that over time, there is a surprising level of congruence between the public priorities of the citizens and the issues dominating the political agenda. This fact has been shown both in the US political system (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005) and in the European context (Jennings and John, Reference Jennings and John2009; Bonafont and Palau, Reference Bonafont and Palau2011; Lindeboom, Reference Lindeboom and Jones2012; Visconti, Reference Visconti2018) with regard to different stages of the policy process. A second general finding is that issue-responsiveness is higher in agendas characterized by fewer frictions. The punctuated equilibrium theory (henceforth, PET) maintains that cognitive and institutional frictions prevent political actors and institutions from reacting proportionally to incoming information. However, agendas that are subject to less friction (i.e. parliamentary questions asked by any MP) are more responsive to public priorities than agendas characterized by a higher level of friction (i.e. laws or budgets, which can only be passed with the agreement of many actors) (Bevan and Jennings, Reference Bevan and Jennings2014).

Institutions have notable inertia and tend to underreact to new information until, after a period of accumulation, the mounting pressure eventually causes a major attention shifting – when it has already become unavoidable (Baumgartner and Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones2002). This happens especially during crises, which impose the necessity of an immediate reaction. At that very moment, pressure for change becomes so powerful to be able to subdue the barriers erected by frictions, causing a severe attention-shifting and the compression of the agenda mostly around the crisis-related topic. In times of crises, we might expect the difference between high- and low-friction agendas to be reduced.

It has already been shown that when a crisis hits hardly, policy-makers abandon their agenda-setters' capacity to become agenda-takers compelled to focus on the topic that dominates the agenda. During the Great Recession, for instance, the increasing concern of public opinion toward the economy incentivized southern European parties, regardless of their role in government or in opposition, to shift attention toward the same topic (Borghetto and Russo, Reference Borghetto and Russo2018). A similar outcome has been found in Denmark during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, which altered the usual issue competition dynamics encouraging parties to focus on issues that were most important for the public opinion (Tornafoch-Chirveches, Reference Tornafoch-Chirveches2023).

Parliamentary questions and issue responsiveness

Many studies have focused on the responsiveness of parliamentary agendas to external sources of information, in ordinary times or during crises. We have already cited studies linking public priorities to issue-attention within political institutions. There are also studies showing that parliamentary questions reflect public priorities (Penner et al., Reference Penner, Blidook and Soroka2006). However, issue responsiveness can be produced also when political actors take cues from the media or from real-world problem indicators, and these effects have also been explored by the literature.

For instance, Vliegenthart et al. (Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave, Baumgartner, Bevan, Breunig, Brouard, Bonafont, Grossman, Jennings, Mortensen, Palau, Sciarini and Tresch2016) studied seven European countries, confirming the general finding that media are a strong determinant of issue attention in parliamentary questioning. Vliegenthart and Damstra (Reference Vliegenthart and Damstra2019) analyzed four countries pooling together oral and written questions, seeing that the agenda-setting effect of the media decreases when the economic situation (measured with consumer confidence) worsens. Beyond media, political actors can also be responsive by reacting to the evolution of objective social phenomena: a recent study on 10 European countries found that real-world problem indicators concerning the economy, migration, and terrorism generally influence the content of parliamentary questions, although the intensity of the relationship depends on political parties' strategic choices and other political factors (Bevan et al., Reference Bevan, Borghetto and Seeberg2024).

Despite the merits of these studies, which aim to uncover countries' differences and similarities and to generalize results about agenda-setting dynamics, we should bear in mind that, exactly as not all crisis-events are equal (Boin et al., Reference Boin, Ekengren and Rhinard2020), institutional venues as well diverge considerably among each other. Different types of parliamentary questions are subject to different rules, determining who can ask them (individual MPs vs. the parliamentary group) and with which frequency (unlimited or once per week). This is precisely what scholars of the PET refer to as institutional frictions (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005). In the Italian case, parliamentary rules give the opportunity to each parliamentary party group to ask only one question for immediate reply per session/week, regardless of the party's role in parliament (e.g. if the party belongs to the governing coalition or seats at the opposition benches) and of its size. This forces each party to choose weekly which issue to prioritize, making the question time an optimal venue for parties to show their priorities (Cavalieri and Froio, Reference Cavalieri and Froio2022). By contrast, each MP is entitled to ask unlimited questions for written answers, an activity which is not subject to much party control: written questions are the domain of individual representatives more than collective actors (Russo, Reference Russo2021).

Crises break routing decision-making, but do different crises have the same effect on attention–concentration dynamics or are there any differences based on the type of crisis-events? How should we expect responsiveness in these two venues to differ when a crisis hits? Before formulating some hypotheses in the fourth section, the next section elucidates our definition of crisis, the operative criteria adopted to identify politically relevant crises and the crises we identify in the period 2005–2022 in Italy.

What is a crisis?

Crisis is still an underdeveloped concept. Despite the increasing attention to the topic, there is not yet a shared definition of crisis. As Hewitt (Reference Hewitt1983) stated, the term “crisis” is typically used as a catchall concept encompassing a variety of “un-ness” events, for example, situations which are unwanted, unexpected, unprecedented, and almost unmanageable and that cause widespread belief and uncertainty (Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Boin and Comfort2001; Stern and Sundelius, Reference Stern and Sundelius2002; Lipscy, Reference Lipscy2020). To date, scholars tend to identify crises as moments characterized by threat, uncertainty, and urgency (Hermann, Reference Hermann1963; Boin et al., Reference Boin, Hart and McConnell2009; Lipscy, Reference Lipscy2020), with a strong intersubjective component, irrespective of whether these elements are measurable against some external standard or are mere constructions of the mind (Kreuder-Sonnen, Reference Kreuder-Sonnen2018). For this reason and considering the number of issues usually associated with the term “crisis”, we opted for an operative criterion to select which events to analyze.

We combine two intersubjective criteria to avoid arbitrary choices in selecting crisis events. On the one hand, we rely on the scientific community to identify events affecting Italy in the last two decades which can be called crises. Second, we consider them true political crises only when Italian citizens perceive the related issues as important problems. By doing so, we recognize that not all important problems are political crises (they might lack the unexpectedness or the uncertainty associated with the concept) and not all crises are political (they might lack relevance for the general public). In addition, our dual criterion considers both the objective aspect and the subjective perception of crisis-events (Spector, Reference Spector2020), which are socially constructed political phenomena (Hart, Reference Hart1993). For the first aspect, we employed Scopus, which is regarded as a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, and reliable abstract and citation database. We downloaded the titles of 249 articles containing the terms “crisis” and “Italy” in the title and analyzed them to determine which event they referred to as a crisis. The results are presented in Table 1 and discussed more in-depth in the Appendix: in summary, experts mostly used the term to refer to the economic, health (Covid), and migration crises.

Table 1. Events associated with the term crisis by scholars (2005–2022)

Source: Authors' elaboration on Scopus data.

The relevance of the crisis-events in the eyes of citizens has been assessed using the Eurobarometer (Figure 1), and especially the question on the most important issues (MIIs) that their country is facing at the moment according to their perception.Footnote 1 Among the 15 available options (e.g. crime, energy, taxation, terrorism, housing, etc.), we considered those matching the crises already objectively identified through Scopus: the economic situation (in its various manifestations such as unemployment or inflation), the environment, health, housing, and immigration. We noted a striking correlation between the frequency of scientific articles on different crises and the importance attributed by citizens to the respective issues. In the period considered, the environment and housing are considered one of the two MIIs by far less than 20% of the respondents. On the contrary, the economic situation, migration, and health all reached peaks exceeding 40%.

Figure 1. Events considered one of the MIIs by citizens (2005–2022).

Source: Own processing on Eurobarometer data.

Note: Quarters in the x-axis correspond to the survey waves.

The economy is always a very salient problem for Italian citizens: though most of the issues related to the economy reached their peaks during the Great Recession, they are always on top of people's concerns.

Health grew dramatically during the pandemic crisis, and immigration shows an increasing trend from 2014, when millions of refugees from the African continent and the Middle East tried to reach Europe. This issue remained one of the MIIs in the respondents' perception until 2017, although the cruelest moments of the emergency were already over. Based on our double requirements of being defined as crises by experts and attracting considerable attention from the public, we decided to focus on the economic, immigration, and health crises.

Hypotheses

This work assesses the effect of the three identified crises on the attention–concentration in the Italian parliament between 2005 and 2022. As reviewed in the second section, crises are able to interrupt routine decision-making, changing the usual attention–concentration pattern. At the same time, the level of frictions of different institutional venues varies, affecting the ability of policy-makers to process and update information, thus shaping agenda-setting dynamics. Parliamentary activities more constrained by institutional frictions should be influenced more severely by crisis-events. The reason is that, in such venues, information is not uniformly reviewed and the accumulation of pressure will eventually cause a more dramatic attention shifting, so-called punctuation, when a crisis happens.

Our primary goal is to investigate whether different venues are equally responsive to (different) crises. In our case, the (oral) question time, where there is a maximum number of questions per week that can be asked by parliamentary party groups – thus making the question time a zero-sum game – is characterized by more frictions compared to written questions, which have not the same limitation (see the next section for details). The difference between the two venues should be present both in ordinary and crisis-moments and should be visible through the whole distribution of attention accorded to each topic. In this regard, previous studies inform that the distribution of attention resembles a Gaussian in those venues with lower frictions (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Sulkin and Larsen2003). Therefore, our first hypothesis, which focuses on institutional frictions, is:

H1: The variation of attention to crisis-related topics is more similar to a normal distribution for written questions and is more leptokurtic for oral questions.

One of the main findings of the literature on issue representation (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2004) is that there is a good correspondence between the priorities of the public and the agenda of legislative bodies. This is especially true in case of crisis, when incoming signals point all to the same issue so policy-makers can't avoid engaging with them. These indications may come from different sources, such as public opinion, media, or real-world indicators. There is abundant literature on how public priorities, the media and parliamentary debates influence each other (Soroka, Reference Soroka2002b; Vliegenthart et al., Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave and Zicha2013; Van Der Pas et al., Reference Van Der Pas, Van Der Brug and Vliegenthart2017). The usual finding is that the level of press coverage and public attention to issues mirror each other (McCombs and Shaw, Reference McCombs and Shaw1972; McCombs, Reference McCombs2004) and that there is a tight interdependence between them. Vliegenthart and Damstra (Reference Vliegenthart and Damstra2019) examined the interactions among public concerns with the economic situation, media coverage of the economic crisis, and parliamentary questions in four countries finding that the relations among them are multidirectional, and the main direction depends on the context. Building on these consolidated findings, we formulate the following general hypothesis.

H2: In all crisis-related issues we expect to observe issue-responsiveness to one or more indicators (real-problem indicators, public opinion, media attention).

Moving to more specific hypotheses, there are reasons to hypothesize that public opinion is especially relevant in the most visible venues, where majority and opposition parties publicly outline their positions. The classic literature about dynamic representation (Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, MacKuen and Erikson1995) advises that responsiveness to public opinion is also about prioritizing citizens' concerns, which is usually investigated by studying the parliamentary arena.Footnote 2 As a matter of fact, some studies of oral parliamentary questions found that during periods of crisis, political parties' responsiveness to people's concerns increases (among others, Tornafoch-Chirveches, Reference Tornafoch-Chirveches2023). This is explained by arguing that political parties cannot ignore issues which are extremely relevant to public opinion: in that sense, they become agenda-takers rather than agenda-setters (Borghetto and Russo, Reference Borghetto and Russo2018). However, considering that oral and written questions are used as different channels for representation – written questions respond mostly to local constituencies' problems and are less constrained by party's and leadership's steering (Sorace, Reference Sorace2018; Russo, Reference Russo2021) – we also imagine a different effect of public priorities in the two venues. More precisely, we think that public priorities detected at the national level are closely related to question time but do not have clear expectations on written questions.

H3: The increased concern of the public with a crisis-related issue increases parliamentary attention to the same topics in question time.

The role of the media in influencing the parliamentary agenda has been the object of several studies. The degree to which media attention sets the agenda of political institutions depends on a few factors, such as the context and attributes of the issues. At a general level, previous works found no significant impact of parliamentary attention on media attention, but the opposite relationship holds (Vliegenthart et al., Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave, Baumgartner, Bevan, Breunig, Brouard, Bonafont, Grossman, Jennings, Mortensen, Palau, Sciarini and Tresch2016; Vliegenthart and Damstra, Reference Vliegenthart and Damstra2019). In this regard, for instance, countries more severely affected by the economic crisis show a lower role of media attention on politics (Vliegenthart and Damstra, Reference Vliegenthart and Damstra2019). In addition, the type of crisis affects the degree of media effect. Soroka (2002a, Reference Soroka2002b) found that the decisive factor is issue obtrusiveness, that is the degree to which the public has a direct (rather than mediated) experience of the problem in question. The media's role is decisive for unobtrusive issues but is only marginal for obtrusive ones. Concerning the crises that are the object of our study, we can safely assume that the economic and health (Covid-19) crises have been obtrusive, while the migration crisis has mainly been unobtrusive. In general, inflation and unemployment are directly felt by citizens. The Covid-19 crisis, with the restrictions imposed to contain the pandemic and a significant number of hospitalized patients, has profoundly touched ordinary citizens. On the contrary, the significant number of migrants reaching the Italian shores during the refugee crisis has been perceived only indirectly in most Italian regions. Because previous research does not help us theorizing about a divergent impact of media attention on question time and written questions, will explore the difference between the two venues in the analysis.

H4: Media can set the parliamentary agenda (written questions and question time) for non-obtrusive issues.

At last, recent research informs us that policy-makers are attentive to the developments of problems and that a relationship exists between indicators and agenda-setting (DeLeo and Duarte, Reference DeLeo and Duarte2022). Scholars found that “the positive effect of the current severity in the indicators applies regardless of how many people a problem affects, how intense those effects are, and several other problem characteristics” (Kristensen et al., Reference Kristensen, Mortensen, Green-Pedersen and Seeberg2023: 256). Not all studies point in the same direction, though. Bevan et al. (Reference Bevan, Borghetto and Seeberg2024), analyzing the relevance of indicators on the agenda-setting process, found that not all problem indicators affect the agenda equally and that some can be perceived as “valence” issues in which the majority of parties have an interest in showing some concern when indicators worsen (e.g. unemployment).

On this regard, we know that crises have a shattering effect on the agenda-setting process, but their strength may vary based on the crisis-related issue. As a consequence, even the impact of real-world indicators would change according to the topic. Following the results of Bevan et al. (Reference Bevan, Borghetto and Seeberg2024), we suppose that those issues where parties or MPs are expected to hold very similar policy positions – that is, “valence” issues (Stokes, Reference Stokes1963) – would be more affected by modification of real-world indicators. Instead, issues where parties or MPs show divergent ideological stances – that is, positional issues – continue to be more subject to partisan logic than to the worsening of indicators, even in times of crisis. Among the crisis-related issues analyzed here, we consider the economy and health as valence issues (all parties mainly wanted to revive the economy and reduce the spreading of the Covid-19 virus) that no party could allow to ignore, while migration is traditionally considered a positional issue. As the question time is the venue in which issue-competition among parties take place, we expect that:

H5: The worsening of real-world indicators about valence crisis-related topics only increases parliamentary attention to the same (valence) topics in oral questions.

In order to test our hypotheses, we used different methods. In the next section, we run some univariate analyses of the dependent variables to test H1. Then, we described the independent variables and the statistical models used to test the remaining hypotheses.

Agenda-setting dynamics in written and oral questions

To begin with, we scrutinize how attention to the three crisis-related topics varies in the Italian parliament. We use the datasets about oral parliamentary questions for immediate reply (question time, henceforth QT) and written questions. Our unit of analysis is the question (written and oral) per date, classified according to the Comparative Agendas Project codebook, which assigns a code to each observation based on the topic discussed.Footnote 3 The question time has been manually labeled by scholars of the Italian team of the CAP (Russo and Cavalieri, Reference Russo and Cavalieri2016) while written questions have been coded using conventional supervised machine learning techniques.Footnote 4 Considering the crises we identified, we analyzed the macro categories Health (CAP code 3), Immigration (CAP code 9), and a unique category for Economy which puts together Macroeconomics (CAP code 1) and Labor (CAP code 5).Footnote 5 There are different ways to assess the variation of attention in the parliamentary agenda, each of which has theoretical advantages and disadvantages. In line with the CAP literature, to test the kurtosis of the distributions we use the percentage-percentage method (Jones and Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005: 202). The semester-to-semesterFootnote 6 percentage-change score is computed using the following formula:

Scholars adopting this method visually represent the variation of attention pooling together percentage changes to study how the frequency distribution appears. A non-normal distribution which characterizes inefficient policy-making processes where cognitive and institutional frictions hinder the ability of moderate adjustments while favoring instead tiny or extreme changes, is the most frequent one. It has been found to represent the decision-making process of diverse agendas, institutional settings, and countries. This is clearly what emerges also from the frequency distribution of attention shifting in the Italian question time and in written questions about the three crisis-related topics we are studying, that is, economy, health, and immigration.

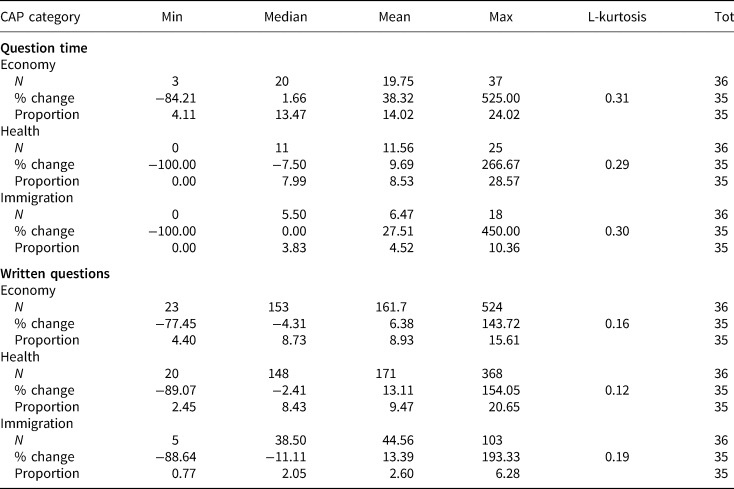

Figure 2 shows the magnitude and frequency of changes per category in both parliamentary activities, pointing out that both of them show signals of a punctuated allocation of attention, evident from the leptokurtic shape of the frequency distribution. A great number of changes is located around 0, meaning no change at all, which increases the height of the central peak. The shoulders of the distribution are rather bare compared to those of a Gaussian, while there is a relevant number of major changes, falling in the tails which reach −100 percentage change and even more than +600 percentage change. The leptokurtic distribution is confirmed by the value of L-kurtosis of each category in both parliamentary activities, described in Table 2.

Figure 2. Frequency distribution of changes of attention toward Economy, Health, and Immigration (2005–2022).

Note: The percentage change is calculated on the number of observations of the previous semester. The left side of the distribution is naturally bounded at −100%.

Table 2. Summary statistics of the dependent variables between semesters (2005–2022)

The L-kurtosis is a measure of kurtosis – the fourth moment of a distribution which assesses how peak or flat the distribution is – based on L-moments, which calculates the fourth L-moment by normalizing kurtosis by the variance (the second moment). This measure is not that sensitive to extreme values and is reliable even with a scarce number of observations (Hosking, Reference Hosking1990). It takes on values from 0 to 1, with a normal distribution having an L-score of 0.12 (Breunig and Jones, Reference Breunig and Jones2011). Both Figure 2 and Table 2 show that the two agendas diverge in terms of the degree of leptokurtosis, thus of frictions. As evident from the value of the L-kurtosis, the distribution of attention in written questions for each of the three categories analyzed approaches that of a Gaussian, while the attention in the question time is much more fluctuating and unstable.

This preliminary investigation of the level of attention shifting, thus of frictions, in the two parliamentary activities, is already insightful of the divergent behavior of the two parliamentary activities. As we discussed in the literature review, a relevant reason might be that written and oral questions have different rules of procedures, thus institutional frictions which constrain the attention-allocation. As a matter of fact, the size of the agenda of written questions is not fixed – differently from the question time where each parliamentary party group can ask only one question per session –, which considerably affects the rationale behind the choice of which issues to prioritize.

For this reason, we prefer to use as dependent variable the proportions of attention toward each topic instead of the percentage change. In this way, we have also information about the trade-off between different categories into the two parliamentary agendas. We summarize the number of questions per semester from the beginning of 2005 to the end of 2022, to have the same time span of our independent variables. More precisely, we first calculated the total number of questions (written or oral) per semester, and we sum the questions per category on the same semester. Then we computed the proportion of each category during the semester on the total number of questions in the same semester. Figure 3 shows the proportion of the three categories we are investigating during the semesters considered.

Figure 3. Proportion of attention toward Economy, Health, and Immigration in oral and written questions (2005–2022).

The allocation of attention in oral and written questions is clearly subject to different dynamics. Trends in question time are considerably more unstable than those in the written questions, probably as a consequence of the limited space of the agendas that compels parties to choose only one issue per week to propose to the parliament.

Considering the topic-related crises here analyzed, Economy stands out to be the one that gains the highest proportion of attention in the question time, while in written questions health reaches a comparable level of interest. Without surprise, the emphasis toward economy increases during the Eurozone crisis (2010–2014) and, only in oral questions, also during the pandemic crisis, probably as a consequence of the lockdown and of its repercussions on economic activities. The same, however, doesn't happen in written questions, suggesting different attention-allocation dynamics. The Covid-19 crisis boosted interest in the category Health especially in written questions, when the proportion of attention to the topic doubled compared to the second semester of 2019. It increases only slightly in oral questions, although especially in 2021, after almost 1 year since the outbreak of the pandemic.Footnote 7 Immigration is the least discussed topic among the three almost for the entire period, although the proportion of questions related to the issue grew in some periods, especially between 2015 and 2018. Actually, the most severe phases of the migration crisis in southern Europe occurred already in 2014, but apparently the reflection on the parliamentary agenda happened a bit later. Summary statistics in Table 2 confirm the differences in the agendas visually detected in Figure 3 (see the Appendix for further evidence). Health and Economy are the MIIs in written questions, with a similar median value of the total proportion, four times higher than the median value of Immigration. Instead, Economy leaves Health behind in oral questions, as seen in Figure 3.

Models and results

In the fifth section, we confirm H1 from which we expected that attention to the three crisis-related topics was more leptokurtic in question time than in written questions. To test the remaining hypotheses, our dependent variable is the percentage of parliamentary questions devoted to a given issue (Economy, Immigration, Health) during a semester (Figure 3). The variable is bound between 0 and 100 and could be modeled with specific techniques such as fractional logit or beta regression. However, the estimation is subject to another challenge: according to visual inspection and specific tests,Footnote 8 the series on question time are stationary, but most of those on written questions are not. This might lead to spurious regressions in case we neglect the non-stationarity of the latter. Considering the relatively small sample size (n = 36) and the necessity to model written questions in the first-difference form, we decided to rely on simple ordinary least-squares (OLS) regressions,Footnote 9 keeping in mind that our estimates are likely to be precise at the median of the distribution but may be imprecise at the extremes (Villadsen and Wulff, Reference Villadsen and Wulff2021).

In the fourth section, we hypothesized multiple and varying effects of public opinion, media attention, and real-world indicators on the variation of attention to crisis-related issues in QT and written questions. For the first one, we used the MII from the Eurobarometer survey (see the Appendix for details), considering questions that indicated Health, Immigration, and the Economic situation as one of the two MIIs facing Italy at the moment when the survey was administered. To measure media attention, we used the Lexis Nexis database, a rich source of journalistic material, from which we selected ANSA, the preeminent Italian news agency and among the principal sources of news for newspapers. The choice is driven by the fact that ANSA is a comprehensive, rich and non-partisan news agency, and the only one that is fully covered by Lexis Nexis in the time-period considered in this study (2005–2022). Data were retrieved through a dictionary approach, by searching articles' titles for keywords related to the issues (see the Appendix). The real problem indicators about the three crises we used are the economic discomfort index utilized by Borghetto and Russo (Reference Borghetto and Russo2018), the mortality rate computed on ISTAT data, and the number of irregular sea border crossings as registered by Frontex (details on these indicators are given in the Appendix).

Tables 3 and 4 present the result of the regression analyses predicting the number of written questions and questions for immediate reply (question time) on the three crisis-related issues based on media attention, public opinion data, and real-world problem indicators. All relations are modeled through bivariate regressions (models 1–3) and finally with multiple regressions (model 4). Diagnostic analysis does not reveal autocorrelation, but some multiple regression models exhibit multicollinearity because the regressors are highly correlated (see the Appendix).

Table 3. Question time (OLS on variables in level)

Note: *P < 0.1; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01 (robust standard errors).

Table 4. Written questions (OLS on variables in first difference form)

Note: *P < 0.1; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01 (robust standard errors).

A first look at the goodness of fit of the models reveals that in general, they have at best moderate explanatory power (Economy and Migration for QT, Migration and Health for Written Questions). This is not surprising for time series analyses which do not include a lagged dependent variable. It is worth noting that the results of the models on oral and written questions are not directly comparable, because the latter are run in first-difference form.

H2 maintains that all crisis-related issues should be responsive to the different signals sent from society, without specifying the relative importance of the indicators and the different characteristics of the venues. This expectation is strongly supported by our data. Taking the six issue-venue combinations, in five of them we find that parliamentary attention is related to at least one of the indicators considered. QT is not responsive to Health,Footnote 10 and written questions are only weakly linked to the Economy. The remaining hypotheses are more specific.

H3 holds that public opinion should predict the parliamentary agenda when it comes to question time. Our models give a more nuanced picture. In the bivariate specification, public opinion influences question time for the economy and for migration. However, when considering all the regressors at the same time, the role of public opinion is dwarfed by real-world problems. The likelihood ratio test, commonly used to compare the goodness of fit of nested and complex models, supports the conclusion that the full model for the Economy is not significantly more accurate than the one including only the real-world indicatorFootnote 11 (the economic discomfort index). The situation is however different for parliamentary attention to migration, where the model with only public opinion has the highest explanatory power. In the full model, although the F statistic suggests that the overall model is significant, individual coefficients are no longer statistically significant, a common problem when the predictors show a high degree of multicollinearity. However, the likelihood ratio test fails to reject the null hypothesis that the simple model (only public opinion) is inferior to the complete model. Although we did not have specific expectations on written questions, it is worth noting that Table 4 shows that, in the bivariate specification, public opinion is positively related to migration and health (and not to the economy), but its role in health disappears when controlling for the role of media attention.

H4 holds that media attention is likely to have a greater impact on non-obtrusive issues such as Immigration than on issues perceived directly by citizens such as the economic or the Covid-19 crises. This expectation is supported by the models on question time (media attention is a significant predictor of QT on Immigration), but written questions obey the opposite logic. The number of articles published by the news agency ANSA is the most important predictor of written questions on Economy and Health (the predictor is the only one having a statistically significant effect in the full models). It is puzzling to find that media have such a relevant role for written questions concerning obtrusive issues, which are likely to have a direct effect on citizens. This suggests that individual MPs, the actors mainly responsible for formulating such questions, take more cues from the media than from direct interactions with citizens.

Finally, according to hypothesis five, we should expect that real-world indicators should be more relevant for valence issues (Economy and Health) than for positional issues (Immigration), at least when looking at question time. The hypothesis is supported concerning economic matters. Contrary to our expectations, the real-world indicator of the migration crisis – the number of sea border crossings – plays a role in shaping attention during question time and, even more clearly, in questions for written reply. This might be a sign that the convergence of mainstream parties on the migration issue has transformed it into a valence issue, as argued by Fumarola (Reference Fumarola2021). Finally, the mortality rate has no effect on parliamentary attention to health issues, but this might depend on the specificity of the CAP coding system, as we have already discussed.

Conclusion

In this article, we explore the degree of responsiveness in periods of crisis across parliamentary venues to uncover variation between parliamentary venues and across crises.

On the first side, considering questions for written replies and oral questions with immediate response as two separate venues, we advanced previous studies by showing that the two obey different logics in periods of crisis. The agenda-setting literature explains that institutional frictions determine the degree of attention concentration and that, when an external shock occurs, the power of these barriers subsides and the focus shifts toward the crisis-related issue, regardless of the venue. Instead, we show that in Italy the distinction between question time and written questions remains also in crisis-moments, signaling that frictions are extremely variable among different forms of parliamentary questioning and thus, that written and QT questions constitute dissimilar channels for issue responsiveness.

On the side of crises, we suspected that not all shocks have the same power to set the parliamentary agenda, thus we compared the economic, migration, and pandemic crises that severely hit Italy, and many other European countries, in the past 20 years. In turbulent times, policy-makers receive abundant signals from different sources pointing toward the crisis-related issue and try to be responsive toward those signals. Our analyses of the effect of increasing public concerns and media attention, and worsening real-world indicators indicate that issue responsiveness in moments of crisis operates for both written and QT questions, but the precise dynamics are highly conditional on both the type of issue under examination and the characteristics of the venue.

Question time is generally responsive to public opinion and real-world problems, with the news exerting a notable impact only on the least obtrusive issue, migration. We also found that – at least when aggregating observations on a bi-annual period – it becomes impossible to discriminate the individual effect of our three independent variables on migration, because they move together. However as public opinion and news cannot cause real-world phenomena, it is reasonable to assume that the number of sea border crossings is the ultimate cause of the spikes in attention to Immigration in QT. Despite the differences based on the crisis-related issue, our findings on the QT are in line with the agenda-setting literature.

We improved our knowledge by generating new hypotheses on a rather understudied venue as questions for written replies. Our analysis indicates that written questions respond mostly to the mediatic agenda, especially for obtrusive issues, which might be related to the cognitive frictions of individual MPs – written questions in Italy are typically an initiative of single parliamentarians while oral questions are a party-group activity – whose behavior is influenced by the most easily available information, media attention. In contrast, the higher number of actors within a party may increase the cognitive capacity and sources of information of the overall group. The impact of cognitive frictions in determining the sources of information to which MPs and parties relay is an under-researched topic that should be explored more in depth by future studies.

Overall, our study urges agenda-setting scholars to carefully consider dissimilarities even between somehow similar parliamentary venues, as written and oral questions and also to take into account the characteristics of crisis-events and of the issue at stake during turbulent times. As a matter of fact, despite a similar ability to interrupt the routine decision-making process, crises do not have the same effect on agenda-setting dynamics.

Funding

This work has been conducted within the framework of the PRIN 2020 Project DEMOPE DEMOcracy under PressurE (Prot. 2020NK2YHL), funded by the Italian Ministry of Universities and Research.

Data

The replication dataset is available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/HAM7MJ.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2025.5

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the guest editors of the special issue “The politics of polycrisis: institutions and political actors in turbulent times”, which this work is part of, and the anonymous reviewers for the precious comments.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.